Abstract

The PA3004 gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 was originally annotated as a 5’-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP). However, the PA3004 encoded protein uses 5’-methylthioinosine (MTI) as a preferred substrate and represents the only known example of a specific MTI phosphorylase (MTIP). MTIP does not utilize 5’-methylthioadenosine (MTA). Inosine is a weak substrate with a kcat/Km value 290-fold less than MTI and is the second best substrate identified. The crystal structure of P. aeruginosa MTIP (PaMTIP) in complex with hypoxanthine was determined to 2.8 Å resolution and revealed a three-fold symmetric homotrimer. The methylthioribose and phosphate binding regions of PaMTIP are similar to MTAPs, and the purine binding region is similar to that of purine nucleoside phosphorylases (PNPs). The catabolism of MTA in P. aeruginosa involves deamination to MTI and phosphorolysis to hypoxanthine (MTA → MTI → hypoxanthine). This pathway also exists in Plasmodium falciparum, where the purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PfPNP) acts on both inosine and MTI. Three tight-binding transition state analogue inhibitors of PaMTIP are identified with dissociation constants in the picomolar range. Inhibitor specificity suggests an early dissociative transition state for PaMTIP. Quorum sensing molecules are associated with MTA metabolism in bacterial pathogens suggesting PaMTIP as a potential therapeutic target.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacterium found in a wide range of environments including water, soil, and mammals (1). It is a major opportunistic human pathogen, infecting burns, and lungs in cystic fibrosis (2). Compromised immune systems and extended hospitalization are correlated with infections, making P. aeruginosa the causative agent of approximately 15% of all hospital infections (2). P. aeruginosa infections are difficult to treat since the bacterium has multiple antimicrobial resistance mechanisms (3). Chronic infections can be severe in patients with cystic fibrosis, causing high rates of morbidity and mortality (4, 5). P. aeruginosa contain quorum sensing (QS) pathways involved in the regulation of virulence factors and biofilm formation (7).

Signal molecules of QS include N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs). The concentration of AHLs increases during bacterial growth to allow AHL binding to specific receptors with the regulation of target genes. In P. aeruginosa, the las and rhl QS systems use AHLs of 3-oxo-C12-homoserine lactone and C4-homoserine lactone as signal molecules, respectively. Microarray studies on P. aeruginosa indicated that QS regulated 3–7% of the total open reading frames (6–8). Deletion of single or multiple QS genes reduced the virulence of P. aeruginosa in mouse studies, indicating a strong correlation between the QS system and P. aeruginosa pathogenesis (9–14). Quorum sensing blockade does not affect bacterial growth and is therefore expected to attenuate the virulence of infection without causing drug resistance (15).

Potential therapeutic targets in the QS system include enzymes involved in the formation of AHLs that act as signaling molecules and as virulence factors in P. aeruginosa (15). AHLs are synthesized from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and acylated-acyl carrier protein by AHL synthase with 5'-methylthioadenosine (MTA) as a by-product. MTA is recycled to ATP and methionine for SAM recycling (16). In bacteria, 5'-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase (MTAN) is part of the normal pathway to produce adenine and 5-methylthioribose-α-D-1-phosphate (MTR-1-P) from MTA for SAM recycling. Transition state analogue inhibitors of E. coli and V. cholerae MTAN disrupt quorum sensing and reduce biofilm formation, supporting MTAN as a target for QS (16).

P. aeruginosa is an unusual bacterium as it possesses a putative 5'-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP: PA3004 gene) instead of MTAN. MTAP is rare in bacteria and common in mammals while MTAN is not found in mammals. The action of MTAP on MTA would be functionally similar to that of MTAN by relieving MTA product inhibition of AHL synthase and permitting SAM recycling in P. aeruginosa (17).

The PA3004 gene of P. aeruginosa PAO1 encodes a protein (NCBI ID of NP_251694.1) annotated as a "probable nucleoside phosphorylase" in PseudoCAP (18). It was later proposed to be an MTAP based on catabolism studies in mutant strains of P. aeruginosa (19). PAO503 is a P. aeruginosa methionine-auxotroph. A new strain (PAO6422) was created by inactivating the PA3004 gene of PAO503. PAO503 was complemented for growth on minimum medium with methionine, homocysteine or MTA. PAO6422 responded to methionine and homocysteine but was not complemented by MTA (19). These results supported an MTAP activity for the PA3004 encoded protein. However, the results also support a pathway of MTA → MTI → hypoxanthine + MTR-1-P → methionine, but this was not considered in the original annotation.

In this report we establish the PA3004 encoded protein to be 5'-methylthioinosine phosphorylase (MTIP). Examination of MTA metabolism in P. aeruginosa using [8-14C]MTA confirmed that the pathway involves MTIP. The crystal structure of PaMTIP and three transition state analogue inhibitors with picomolar Ki values for PaMTIP are described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

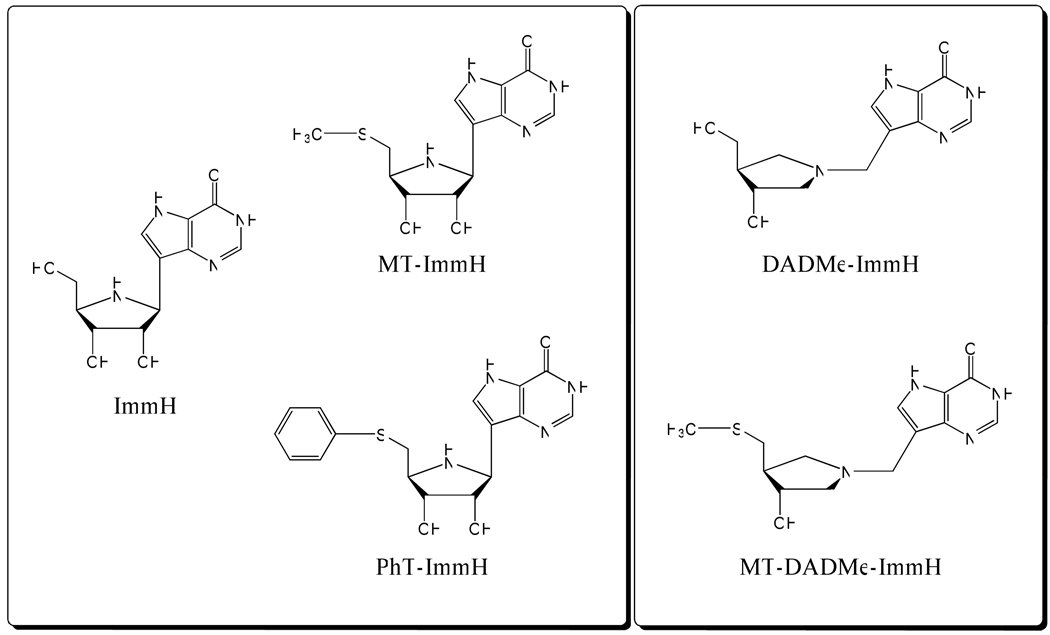

MT-ImmH, PhT-ImmH, and MT-DADMe-ImmH were synthesized by the Carbohydrate Chemistry Team of Industrial Research Ltd, Lower Hutt, New Zealand (Fig. 1). [8-14C]MTA was synthesized as described previously (20). All other chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma or Fisher Scientific, and were of reagent grade.

Figure 1.

Early and late transition-state mimics as inhibitors for PaMTIP and PfPNP.

Plasmid construction

A synthetic gene was designed based on the predicated protein sequence of NP_251694.1 in NCBI, annotated as MTAP of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. The synthetic gene was obtained in a pJexpress414 expression vector from DNA2.0 Inc. This construct encodes an additional 14 amino acids at the N-terminus which includes a His6 tag and a TEV cleavage site.

Enzyme purification and preparation

BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIPL E. coli were transformed with the above plasmid and grown overnight at 37 °C in 50 mL of LB medium with 100 µg/mL Ampicillin. The culture was transferred into 1 L of LB/Ampicillin medium and growth continued at 37 °C to an O.D.600 of 0.7. Expression was induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG. After 4 hours at 37 °C, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4500 g for 30 min. The cell pellet was suspended in 20 mL of 15 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, and 50 mM phosphate, pH 8.0 (lysis buffer), with 2 tablets of EDTA-free protease inhibitor (from Roche Diagnostics) and lysozyme (from chicken egg) added to the mixture. Cells were disrupted twice with a French Press and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a 4 mL column of Ni-NTA Superflow resin previously equilibrated with 5 columns of lysis buffer. The column was washed with 5 volumes of 80 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, and 50 mM phosphate, pH 8.0 (wash buffer), and enzyme was eluted with 3 volumes of 250 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl, and 50 mM phosphate, pH 8.0 (elution buffer). The purified enzyme (> 95% purity on the basis of SDS-PAGE) was dialyzed against 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 and concentrated to 8 mg/ml. Enzyme was stored at −80 °C. The extinction coefficient of PaMTIP is 20.4 mM−1cm−1 at 280 nm, determined by ProtParam program from ExPASy (http://ca.expasy.org/seqanalref/).

Enzymatic assays

Product formation was monitored by conversion of hypoxanthine to uric acid by xanthine oxidase (21). The extinction coefficient for conversion of MTI to uric acid was 12.9 mM−1cm−1 at 293 nm. Enzyme activity with adenosine or MTA as substrates was determined by conversion of adenine to 2,8-dihydroxyadenine using xanthine oxidase as the coupling enzyme (22). The extinction coefficient for conversion of adenosine or MTA to 2,8-dihydroxyadenine at 293 nm was 15.2 mM−1cm−1. Reactions were carried out at 25 °C in 1 cm cuvettes, 1 mL volumes of 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, variable concentrations of nucleoside substrate, 0.5 unit of xanthine oxidase, 5 mM DTT, and appropriate amounts of purified MTIP. Reactions were initiated by addition of enzyme and the initial rates were monitored with a CARY 300 UV-Visible spectrophotometer. Control rates (no PaMTIP) were subtracted from initial rates. Km and kcat values for PaMTIP were obtained by fitting initial rates to the Michaelis-Menten equation using GraFit 5 (Erithacus Software). Phosphate was found to be near saturation when present at 100 mM.

Inhibition assays

Assays for slow-onset inhibitors were carried out by adding 1 nM PaMTIP into reaction mixtures at 25 °C containing 100 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, 2 mM MTI, 5 mM DTT, 0.5 unit of xanthine oxidase and variable inhibitor concentration. Inhibitors were present at ≥ 10 times the enzyme concentration, required to simplify data analysis (23). Assays for MTA inhibition used 200 µM MTI. Controls having no enzyme and no inhibitor were included in all of the inhibition assays. Inhibition constants were obtained by fitting initial rates with variable inhibitor concentrations to equation (1) using GraFit 5 (Erithacus Software):

| (1) |

where vi is the initial rate in the presence of inhibitor, vo is the initial rate in the absence of inhibitor, Km is the Michaelis constant for MTI, [S] and [I] are MTI and inhibitor concentrations, respectively, and Ki is the inhibition constant. Tight-binding inhibitors often display two phases of binding. After the initial rate, a second phase of tighter binding is achieved and results in more potent inhibition. The dissociation constant for the second binding phase is indicated as Ki*. This constant was obtained by fitting reaction rates achieved following slow-onset inhibition and inhibitor concentrations to equation (1) using GraFit 5, but where Ki is replaced by Ki* (21).

Protein crystallization and data collection

Recombinant PaMTIP (9 mg/ml) in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 crystallized in 30% polyethylene glycol monomethyl ether 2000, and 0.1 M potassium thiocyanate in the presence of 5 mM MTI and 5 mM sulfate by sitting-drop vapor diffusion. Crystals were transferred to a fresh drop of crystallization solution supplemented with 20% glycerol and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at Beamline X29A, Brookhaven National Laboratory and processed with the HKL2000 program suite (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| PDB | 3OZB |

| Space group | P41212 |

| Cell dimension | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 99.5, 99.5, 334.9 |

| α, β, γ (o) | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| Resolutions (Å) | 20.0-2.8 (2.9-2.8) |

| Rsym (%) | 17.2 (95.5) |

| I / σI | 9.6 (1.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Redundancy | 7.0 (7.2) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 20.00-2.8 |

| No. reflections | 42041 |

| Rwork / Rfree (%) | 20.2 / 26.2 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | |

| (main chain) | 39.9 |

| (side chain) | 40.9 |

| Water | 25.1 |

| Ligand | 45.7 |

| No. of Atoms | |

| Protein | 10800 |

| Water | 63 |

| Ligand | 60 |

| R.m.s deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (o) | 1.47 |

| Ramanchran analysis | |

| allowed region | 99.3% |

| disallowed region | 0.7% |

Numbers in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell. One crystal was used for each data set.

Structure determination and refinement

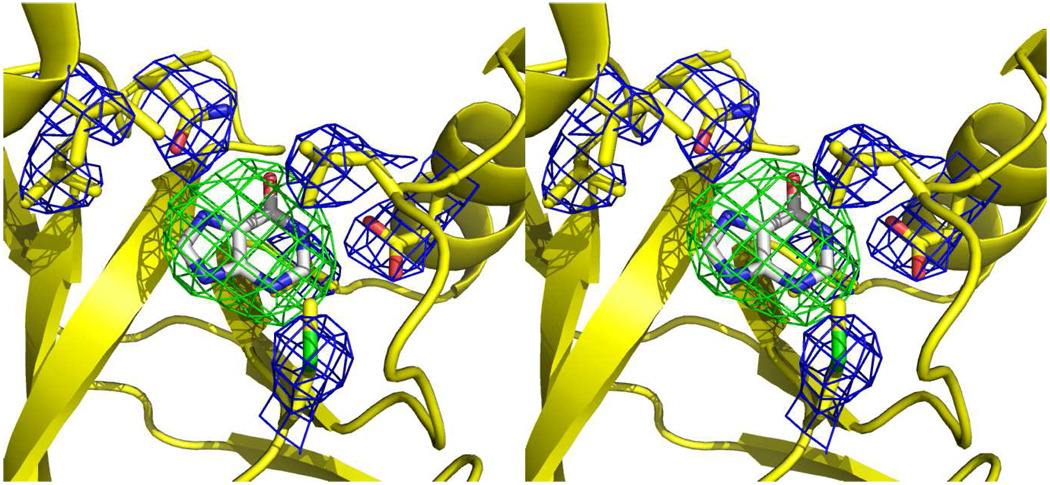

The crystal structure of PaMTIP was determined by molecular replacement with Molrep using the published structure of Sulfolobus tokodaii MTAP (PDB:1V4N, 33.7% sequence identity) as the search model (24). A model without catalytic site ligands was built by Phenix (25), followed by iterative rounds of manual model building and refinement in COOT and REFMAC5 (26, 27). Although PaMTIP was co-crystallized in the presence of sulfate and MTI to mimic the Michaelis complex of PaMTIP, based on ligand-omitted Fo-Fc maps (contoured at 3 σ) electron density was consistent with the presence of only a purine ring in the active site (Fig. 2). PaMTIP was later confirmed to hydrolyze MTI under these conditions. Thus, hypoxanthine was modeled in the active site of PaMTIP (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Stereoview of the hypoxanthine-omitted electron density map of PaMTIP in complex with hypoxanthine. The residues interacting with hypoxanthine are shown as yellow sticks and overlaid with a 2mFo-DFc electron density map (contour at 1 σ). Hypoxanthine carbons are shown as gray sticks and overlaid with mFo-DFc electron density map (contour at the 3 σ).

MTA catabolism using [8-14C]MTA

P. aeruginosa PAO1 (ATCC number: 15692) was grown at 37 °C in LB medium for 16 hours. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 16100 g and washed twice with 100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4. Washed cells were lysed using BugBuster (Novagen). Cleared lysate (53 µL) was incubated with [8-14C]MTA (10 µL containing approximately 0.1 µCi 14C) in 100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, for 10 and 25 min. Reaction mixtures were quenched with perchloric acid (1.8 M final concentration) and neutralized with potassium hydroxide. Precipitates were removed by centrifugation and carrier hypoxanthine, adenine, MTI, and MTA were added to the cleared supernatant. Metabolites were resolved on a C18 Luna HPLC column (Phenomenex) with a gradient of 5–52.8% acetonitrile in 20 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.2. UV absorbance was detected at 260 nm and the retention times were 5.1 min for hypoxanthine, 7.5 min for adenine, 20.4 min for MTI, and 21.9 min for MTA. Fractions were collected in scintillation vials, dried, reconstituted in 200 µL deionized water prior to addition of 10 mL ULTIMA GOLD LSC-Cocktail and 14C was counted for three cycles at 20 minutes per cycle using a Tri-Carb 2910TR liquid scintillation analyzer. Control experiments replaced cell lysate by lysis buffer in reaction mixtures.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

PA3004 encodes a MTI phosphorylase

The recombinant protein from PA3004 was purified and tested for substrate specificity (Table 2). The recombinant protein did not utilize MTA in the presence or absence of phosphate (< 10−4 s−1). The most favorable reaction was phosphorolysis of MTI with a kcat of 4.8 s−1, Km of 2.6 µM (kcat/Km of 1.8 × 106 M−1s−1). Enzyme was less active with inosine with a kcat of 0.57 s−1 and a Km of 90 µM (kcat/Km of 6 × 103 M−1s−1). The methylthio-group of MTI is important for both substrate binding and catalysis. Adenosine is a weak substrate with a kcat of 0.0549 s−1 and a Km of 23 µM (kcat/Km of 2.4 × 103 M−1s−1). Thus the protein encoded by PA3004 is a relatively specific MTI phosphorylase. The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) for MTI is 290 times larger than for inosine, the second best substrate. For comparison, the MTI phosphorylase activity of PfPNP (see below) has a kcat/Km of 9.4 × 104 M−1s−1 for MTI and a kcat/Km of 3.6 × 105 M−1s−1 for inosine.

Table 2.

Substrate specificity of PaMTIP.

| Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km or Ki (µM) | kcat/Km (M−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTI | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | (1.8 ± 0.3) × 106 |

| MTA a | N/A | 70 ± 20 | N/A |

| inosine | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 90 ± 20 | (6 ± 1) × 103[300] b |

| adenosine | 0.0549 ± 0.0005 | 23 ± 1 | (2.4 ± 0.1) × 103[750] b |

MTA is not a substrate of PaMTIP. Ki is used instead of Km for MTA.

Numbers in [] are fold decreases of kcat/Km in comparion with those of MTI.

Values are ± S.E.

MTIP of P. aeruginosa is the only known example of a specific MTI phosphorylase. MTA is not a substrate (< 10−4 s−1 kcat) but is a competitive inhibitor of MTI, with a Ki value of 70 µM, three times greater than the Km of adenosine. Thus, MTA binds to the active site of the enzyme but is not catalytically competent. MTIP activity has been reported in Caldariella acidophilan MTAP, human MTAP, human PNP, and P. falciparum PNP, but MTI is a relatively poor substrate for these enzymes (28–31).

Recombinant MTIP was expressed with a 14 amino acid extension at the N-terminus. Incubation with TEV protease removed 13 of these, leaving one additional glycine at the N-terminus. This construct exhibited the same kinetic properties as the original recombinant protein. The crystal structure (see below) shows the N-terminal extension to be remote from the active site.

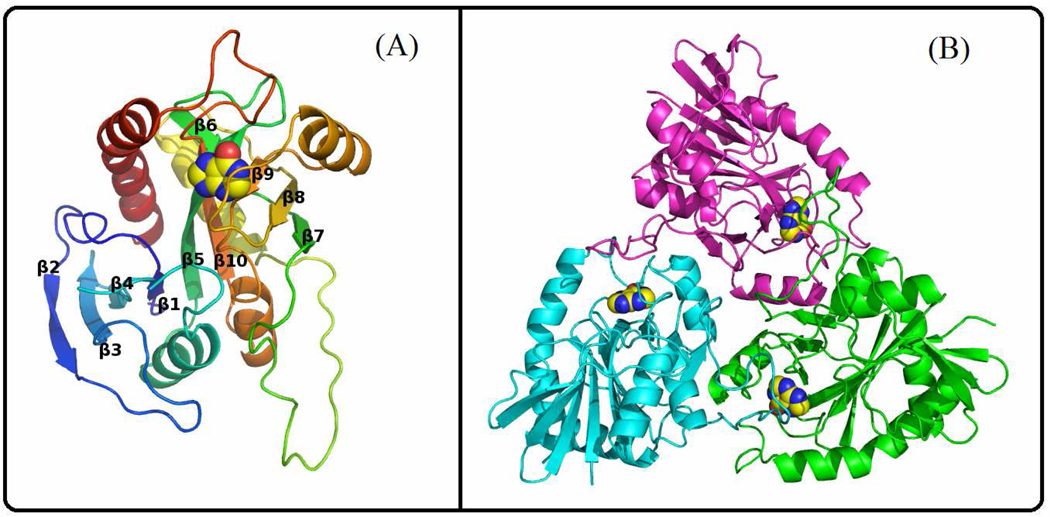

Crystal structure of PaMTIP:hypoxanthine

The crystal structure of PaMTIP in complex with hypoxanthine was determined to 2.8 Å resolution with two homotrimers in the asymmetric unit. Residues 2 to 54 and 60 to 243 of each PaMTIP monomer are ordered in the electron density map. The N terminal His6 tag and TEV protease site are disordered and distant from the active site. The PaMTIP monomer is folded into a single domain structure including ten β strands and five α helices (Fig. 3A). The core consists of a mixed seven-stranded β sheet (β2, β3, β4, β1, β5, β10, and β6) which is flanked by five α helices. β5 is extended and participates in an additional four-stranded β sheet (β5, β9, β8, and β7) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of PaMTIP. (A) A view of the PaMTIP monomer looking toward the catalytic site. The structure is colored from blue (N-terminus) to red (C-terminus). Hypoxanthine is included as a space-filling model to show the position of active site. (B) The monomers of trimeric PaMTIP are shown in blue, green and magenta. Hypoxanthine is included as space-filling models.

The active sites of PaMTIP are located near the interfaces formed between monomers in the trimer. Each trimeric PaMTIP forms three active sites (Fig. 3B). Although PaMTIP was co-crystallized with MTI and sulfate (5 mM) to mimic the Michaelis complex, the ligand-omitted difference Fourier map showed only the presence of hypoxanthine (Fig. 2). Kinetic experiments demonstrated slow hydrolysis of MTI (3.8 × 10−5 s−1) to generate hypoxanthine and 5-methylthioribose. Crystallization attempts with apo-PaMTIP or with PaMTIP in complex with hypoxanthine and phosphate failed to yield crystals. In the crystal structure, hypoxanthine is wedged between the backbone of a 4-stranded β-sheet and the side chains of Leu180 and Met190. Structure-based sequence alignment revealed that Met190 is conserved and Leu180 is replaced by Phe in human PNP and human MTAP (Fig. 4). Hypoxanthine N7 and O6 form hydrogen bond with the side chain of Asn223 in PaMTIP and N1 forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Asp 181 (Fig. 2).

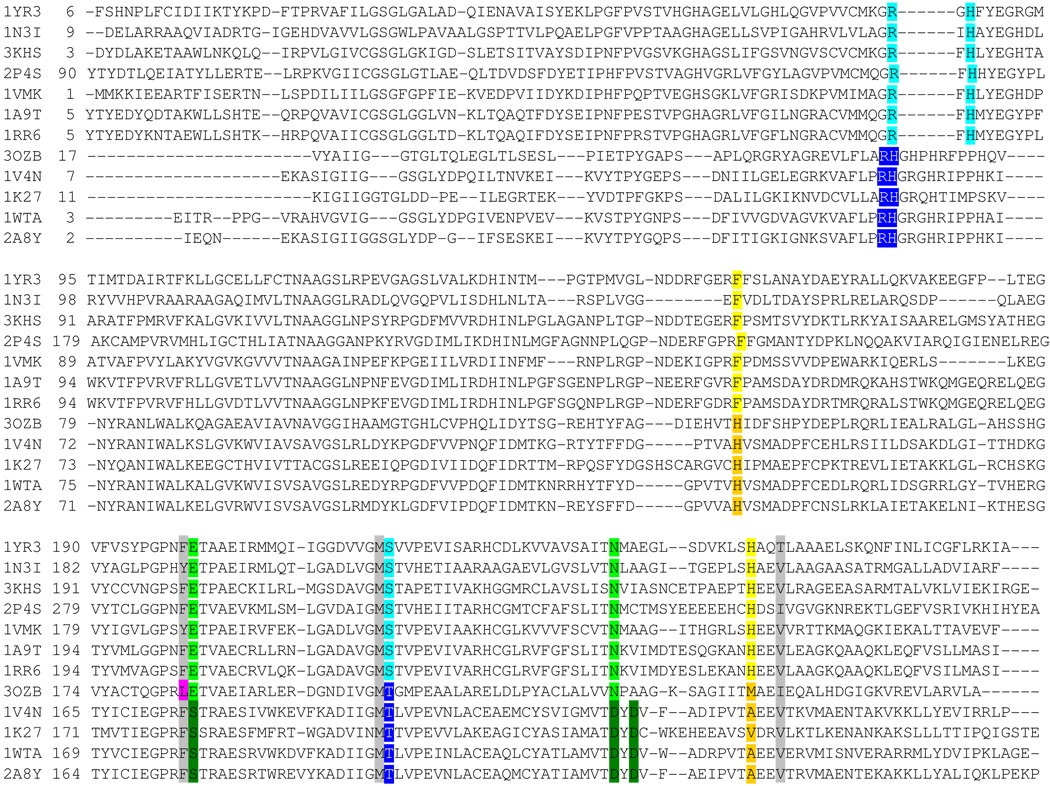

Figure 4.

Structure-based sequence alignment. Protein are listed by PDB ID. The top 7 sequences are PNPs, the bottom 4 sequences are MTAPs and PaMTIP is 3OZB. The conserved residues in phosphate binding region of PNPs and MTAPs are shaded in light blue and dark blue, respectively. The conserved residues in the purine binding region of PNPs and MTAPs are shaded in light green and dark green, respectively. The conserved Phe and His in ribose-binding region of PNPs are shaded in yellow. The conserved His and small hydrophobic amino acid in the (methylthio)ribose-binding region of MTAPs are shaded in orange. The active site residues conserved in all species are shaded in grey. The Leu of PaMTIP is not conserved to either MTAPs or PNPs and is shaded in pink. The PDB IDs are as follow: 1YR3, E. coli PNP II; 1N3I, Mycobacterium tuberculosis PNP; 3KHS, Grouper Iridoviurs PNP; 2P4S, Anopheles Gambia PNP; 1VMK, Thermotoga maritime PNP; 1A9T, bovine PNP; 1RR6, human PNP; 3OZB, PaMTIP; 1V4N, Sulfolobus tokodaii MTAP; 1K27, human MTAP; 1WTA, Aeropyrum pernix K1 MTAP; 2A8Y, Sulfolobus solfataricus MTAP.

Comparison with Other Purine N-Ribosylphosphorylases

Similar catalytic chemistries to PaMTIP are found in the PNPs and MTAPs. It is of interest to examine the amino acid sequences that distinguish PaMTIP and permit its unique substrate specificity. The sequence differences are also useful for identification of other MTIPs in sequence data bases.

The trimeric subunit structure of PaMTIP is similar to the four trimeric MTAPs and seven trimeric PNPs in the Protein Data Bank (r.m.s.d is in the range of 0.8 to 1.2 Å for the monomers). Structure-based sequence alignments with PaMTIP show a 28–40% identity with the four MTAPs and 20–32% with the seven trimeric PNPs (Fig. 4). Ironically, the enzyme most closely related to PaMTIP in catalytic activity is the hexameric P. falciparum PNP/MTIP but it shows no significant similarity in amino acid sequence or quaternary structures with the trimeric PNPs, MTAPs and PaMTIP. Because of these distinct features, Plasmodium PNPs are not included in the following structural analysis (32).

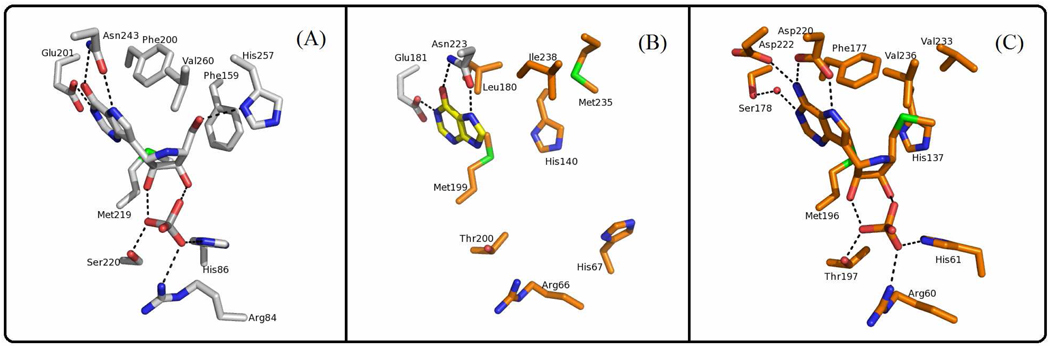

The active sites of PaMTIP, PNPs and MTAPs can be divided into three distinct regions corresponding to the purine-, (methylthio)ribose- and phosphate-binding regions. The Glu201 and Asn243 (human PNP numbering) are conserved in the purine binding region of PaMTIP and PNPs (Fig. 4), and have important roles in 6-oxopurine specificity by hydrogen bonding to N1, O6 and N7 of the 6-oxopurine (Fig. 5A) (33). The Asn243Asp mutant and Glu201Gln:Asn243Asp double mutant in human PNP are known to shift the substrate preference in favor of adenosine, a 6-aminopurine substrate and a preferred substrate for MTAP (34). MTAPs prefer 6-aminopurine because of interactions between N1, O6 and N7 of the 6-aminopurine with conserved amino acid residues Ser178 (via water), Asp220 and Asp222 (human MTAP numbering) (29). The ribose binding region of human PNP prefers nucleosides with a 5’-hydroxyl group but not a 5'-methylthio group. The conserved His257 and Phe159 (from the adjacent monomer) of human PNP are important in binding the 5'-hydroxyl group. His257 forms a H-bond to the 5’-hydroxyl group and catalytic efficiency drops by 660 in His257Gly (38). In MTAP and PaMTIP, a small hydrophobic amino acid corresponding to His 257 of human PNP and a histidine corresponding to Phe159 (human PNP numbering), provide space to accommodate the 5'-methylthio group (Fig. 5). Consistent with these observations, the His257Gly mutant of human PNP binds 5'-methylthio- inhibitors tighter than the corresponding 5'-hydroxyl- inhibitors (35).

Figure 5.

Active sites of human PNP (PDB ID: 1RR6), PaMTIP (PDB ID: 3OZB), and human MTAP (PDB ID: 1K27). (A) The conserved active site residues of human PNP in complex with ImmH are shown as sticks. The hydrogen bonds are indicated as dashed lines. ImmH is a transition state analogue inhibitor of human PNP and a mimic of inosine. (B) The active-site residues of PaMTIP and hypoxanthine (in yellow) are shown as sticks. The residues conserved in PNPs are colored in gray and the residues conserved in MTAPs are colored in orange. The hydrogen bonds are indicated as dashed lines. (C) The conserved active-site residues of human MTAP in complex with MT-ImmA are shown as sticks. The hydrogen bonds are indicated as dashed lines. The water molecule is drawn as a red dot. MT-ImmA is a transition state analogue inhibitor of human MTAP, and a mimic of MTA.

Structural comparison between human MTAP and PNP reveals two distinct motifs in the phosphate-binding region. Favorable hydrogen bonds form between phosphate and the 2'- and 3'- hydroxyl groups of (5’-methylthio)ribose, and thereby anchor (5'-methylthio)ribose in the active site. The position of phosphate in human MTAP provides more room to accommodate the 5’-methylthio group than the position of phosphate in human PNP, explaining the preference for the 5’-substituents.

Structure-based sequence alignment shows that 1) PaMTIP and MTAP share key residues in the phosphate and (methylthio)ribose- binding regions; 2) PaMTIP and PNP share key residues in the purine-binding regions (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5); and 3) these residues provide an approach to identify MTIP in other species.

[8-14C]MTA Catabolism in P. aeruginosa

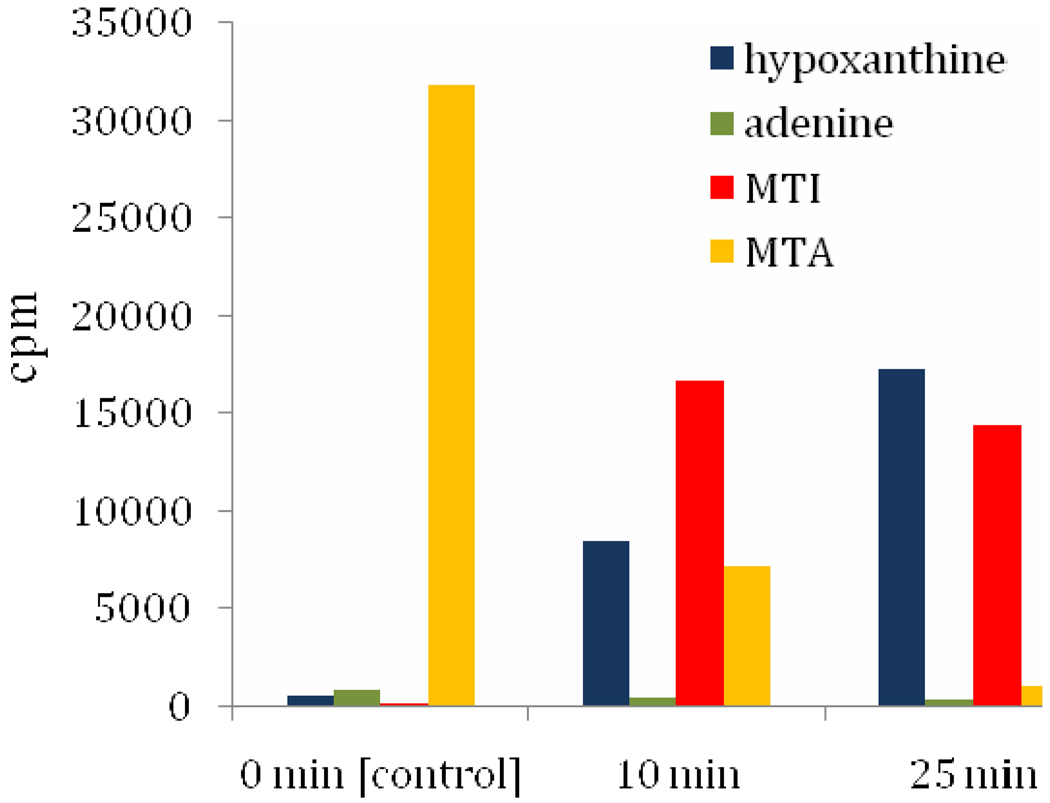

Substrate specificity and structural data of PA3004-encoded protein support a physiological function as MTIP. Thus, MTI must be a metabolite in P. aeruginosa, but there is no previous report of MTI as a metabolite in this organism. Catabolism of [8-14C]MTA in lysates of P. aeruginosa was investigated by tracking the 14C-label into hypoxanthine, adenine, MTI, and MTA. If MTA is first deaminated to MTI followed by PaMTIP action, the sequential conversion to [8-14C]MTI and hypoxanthine would occur without adenine formation. After 10 min incubation with lysate, 77% of the MTA was converted to MTI (52%) and hypoxanthine (25%) without significant formation of adenine (Fig. 6). As 98% of the total 14C-label was recovered, the results establish MTA conversion to MTI and hypoxanthine but not to adenine. At 25 min incubation, over 97% of the [8-14C] MTA was recovered as MTI (45%) and hypoxanthine (53%). Continuous conversion of MTA → MTI → hypoxanthine without significant MTAP or MTAN activity is supported by these results, highlighting the requirement for an MTA deaminase to catalyze the conversion of MTA to MTI. A similar pathway of MTA catabolism is found in Plasmodium species (34). The adenosine deaminase of P. falciparum (PfADA) deaminates adenosine and MTA as substrates with similar kcat/Km values (32). Its purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PfPNP) also degrades inosine and MTI to hypoxanthine with similar catalytic efficiency (31). The substrate specificities of the P. falciparum enzymes permit conversion of MTA to hypoxanthine via MTI. Although MTI has been used as an MTA analogue, its function as a metabolite has been documented only in Plasmodium (28, 29, 36–39). The identification of a specific MTIP activity suggests this metabolite is more widely distributed. Homology searches using the amino acid sequence of PaMTIP readily locates a large number putative of bacterial MTIPs.

Figure 6.

Metabolism of [8-14C]MTA in P. aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa lysate was incubated with [8-14C]MTA for 0, 10, and 25 min, respectively. The 14C-metabolites MTA, MTI, adenine and hypoxanthine were purified using RP-HPLC and quantitated by scintillation counting.

Picomolar Inhibitors of PaMTIP

Immucillins are transition-state analogues developed for N-ribosyl transferases that have ribocation character at their transition states (40). We tested two generations of Immucillins to determine which would be the most powerful inhibitor. ImmH is a first generation Immucillin, resembling early transition states as exemplified by bovine PNP (23) (Fig. 1). DADMe-ImmH is a second generation Immucillin and mimics the fully dissociated transition states of human and P. falciparum PNPs (41). 5'-Alkylthio- and arylthio- derivatives of two generations of Immucillins (MT-ImmH, PhT-ImmH, and MT-DADMe-ImmH) have been synthesized to target the transition-state features of PfPNP with MTI as the substrate (32). Since PaMTIP catalyzes the same reaction, it would be expected that these analogues should act as transition state analogues. The inhibitors exhibited slow-onset inhibition of PaMTIP, suggesting a slow conversion of initial enzyme-inhibitor complex to a more stable conformation.

MT-ImmH inhibited PaMTIP with a Ki* value of 76 pM, binding 4-fold more tightly than MT-DADMe-ImmH, suggesting that the first generation Immucillins more closely resemble the transition state (Table 3). PhT-ImmH was the most tightly bound inhibitor with a Ki* value of 35 pM and demonstrating the importance of hydrophobic substituent at the 5'-position. The KMTI/Ki* values were 34,000 for MT-ImmH, 7,600 for MT-DADMe-ImmH, and 74,000 for PhT-ImmH, emphasizing the potency of these transition state analogue inhibitors. Inhibitor specificity can be compared to that for PfPNP, which catalyzes the same reaction. Thus, MT-ImmH, PhT-ImmH, and MT-DADMe-ImmH bind more weakly to PfPNP with dissociation constants of 2.7 nM, 150 nM, and 0.9 nM, respectively (Table 3) (31, 42). Binding of the bulky, hydrophobic 5'-PhT-group is preferred by PaMTIP where Ki* = 35 pM. This inhibitor induces slow-onset inhibition. In contrast, the same inhibitor has Ki = 150 nM with PfPNP, where it binds 4,300-fold more weakly and does not induce slow-onset inhibition.

Table 3.

Summary of Ki values for PaMTIP and PfPNP.

| Inhibitors | PaMTIP | PfPNPa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (pM) | Ki* (pM) | Ki (nM) | Ki* (nM) | |

| MT-ImmH | 840 ± 50 | 76 ± 5 | 22 ± 3 | 2.7 ± 0.4 |

| PhT-ImmH | 660 ± 90 | 35 ± 3 | 150 ± 8 | ND |

| MT-DADMe-ImmH | 800 ± 100 | 340 ± 20 | 11 ± 4 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

Inhibition constants of PfPNP are from Lewandowicz et al. (42).

Values are ± S.E.

The specificity of these inhibitors is indicated by the observation that none of these gave significant inhibition with human MTAP or Vibrio cholerae MTAN. The Ki values are in excess of 10 µM for these enzymes (data not shown).

The Nature of the PaMTIP Transition State

PfPNP has a fully-dissociated ribocation transition state with approximately 3 Å between the C1' ribocation and N9 and a similar separation between C1’ and the attacking phosphate oxygen. Thus, it prefers to bind MT-DADMe-ImmH rather than MT-ImmH (43). PaMTIP shows the opposite pattern, consistent with an early, dissociative transition state.

Implications for Quorum Sensing

Inhibition studies of PaMTIP have identified three inhibitors with Ki* values in the picomolar range. These are candidates for blocking PaMTIP activities. In most bacteria, MTAN inhibition blocks quorum sensing, but the lack of MTAN in P. aeruginosa indicates that PaMTIP becomes an equivalent target. This study has revealed the pathway of MTA metabolism in P. aeruginosa and has provided new tools to explore this unusual bacterial pathway.

ACKNOWLEGEMENT

Structural data for this study were measured at beamline X29A of the National Synchrotron Light Source. Financial support comes principally from the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy, and from the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge the Carbohydrate Chemistry Team of Industrial Research Ltd (Lower Hutt, New Zealand) for supplying transition state analogue inhibitors.

Abbreviations

- MTA

5'-methylthioadenosine

- MTI

5'-methylthioinosine

- QS

quorum sensing

- AHLs

N-acyl-homoserine lactones

- MTAP

MTA phosphorylase

- MTIP

MTI phosphorylase

- PNP

purine nucleoside phosphorylase

- MTAN

MTA nucleosidase

- MTR-1-P

5-methylthioribose-α-D-1-phosphate

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- ImmH

Immucillin-H

- MT-ImmH

5'-methylthio-ImmH

- PhT-ImmH

5'-phenylthio-ImmH

- ImmA

Immucillin-A

- DADMe

4'-deaza-1'-aza-2'-deoxy-1'-(9-methylene)

- MT-DADMe-ImmH

5'-methylthio-DADMe-ImmH

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH research grant GM41916.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hardalo C, Edberg SC. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: assessment of risk from drinking water. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1997;23:47–75. doi: 10.3109/10408419709115130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodey GP, Bolivar R, Fainstein V, Jadeja L. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:279–313. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strateva T, Yordanov D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa - a phenomenon of bacterial resistance. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:1133–1148. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.009142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:194–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.194-222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Govan JR, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:539–574. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.539-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner VE, Bushnell D, Passador L, Brooks AI, Iglewski BH. Microarray analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing regulons: effects of growth phase and environment. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2080–2095. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2080-2095.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuster M, Lostroh CP, Ogi T, Greenberg EP. Identification, timing, and signal specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-controlled genes: a transcriptome analysis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2066–2079. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2066-2079.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hentzer M, Wu H, Andersen JB, Riedel K, Rasmussen TB, Bagge N, Kumar N, Schembri MA, Song Z, Kristoffersen P, Manefield M, Costerton JW, Molin S, Eberl L, Steinberg P, Kjelleberg S, Hoiby N, Givskov M. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 2003;22:3803–3815. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rumbaugh KP, Griswold JA, Iglewski BH, Hamood AN. Contribution of quorum sensing to the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in burn wound infections. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5854–5862. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5854-5862.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith RS, Harris SG, Phipps R, Iglewski B. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule N-(3-oxododecanoyl)homoserine lactone contributes to virulence and induces inflammation in vivo. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1132–1139. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.1132-1139.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson JP, Feldman M, Iglewski BH, Prince A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cell-to-cell signaling is required for virulence in a model of acute pulmonary infection. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68:4331–4334. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4331-4334.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu H, Song Z, Givskov M, Doring G, Worlitzsch D, Mathee K, Rygaard J, Hoiby N. Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutations in lasI and rhlI quorum sensing systems result in milder chronic lung infection. Microbiology. 2001;147:1105–1113. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-5-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storey DG, Ujack EE, Rabin HR, Mitchell I. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR transcription correlates with the transcription of lasA, lasB, and toxA in chronic lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2521–2528. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2521-2528.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erickson DL, Endersby R, Kirkham A, Stuber K, Vollman DD, Rabin HR, Mitchell I, Storey DG. Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing systems may control virulence factor expression in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis. Infection and Immunity. 2002;70:1783–1790. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.1783-1790.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith RS, Iglewski BH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing as a potential antimicrobial target. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;112:1460–1465. doi: 10.1172/JCI20364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez JA, Crowder T, Rinaldo-Matthis A, Ho M-C, Almo SC, Schramm VL. Transition state analogs of 5'-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase disrupt quorum sensing. Nature Chemical Biology. 2009;5:251–257. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parsek MR, Val DL, Hanzelka BL, Cronan JE, Jr, Greenberg EP. Acyl homoserine-lactone quorum-sensing signal generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4360–4365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winsor GL, Lo R, Sui SJ, Ung KS, Huang S, Cheng D, Ching WK, Hancock RE, Brinkman FS. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Genome Database and PseudoCAP: facilitating community-based, continually updated, genome annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D338–D343. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sekowska A, Denervaud V, Ashida H, Michoud K, Haas D, Yokota A, Danchin A. Bacterial variations on the methionine salvage pathway. BMC microbiology. 2004;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh V, Lee JE, Nunez S, Howell PL, Schramm VL. Transition state structure of 5'-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase from Escherichia coli and its similarity to transition state analogues. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11647–11659. doi: 10.1021/bi050863a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miles RW, Tyler PC, Furneaux RH, Bagdassarian CK, Schramm VL. One-Third-the-Sites Transition-State Inhibitors for Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8615–8621. doi: 10.1021/bi980658d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh V, Evans GB, Lenz DH, Mason JM, Clinch K, Mee S, Painter GF, Tyler PC, Furneaux RH, Lee JE, Howell PL, Schramm VL. Femtomolar Transition State Analogue Inhibitors of 5'-Methylthioadenosine/S-Adenosylhomocysteine Nucleosidase from Escherichia coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:18265–18273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison JF, Walsh CT. The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors. Advances in enzymology and related areas of molecular biology. 1988;61:201–301. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1131–1137. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carteni-Farina M, Oliva A, Romeo G, Napolitano G, De Rosa M, Gambacorta A, Zappia V. 5'-Methylthioadenosine phosphorylase from Caldariella acidophila. Purification and properties. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1979;101:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb19723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zappia V, Oliva A, Cacciapuoti G, Galletti P, Mignucci G, Carteni-Farina M. Substrate specificity of 5'-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase from human prostate. Biochemical Journal. 1978;175:1043–1050. doi: 10.1042/bj1751043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoeckler JD, Cambor C, Kuhns V, Chu SH, Parks RE., Jr Inhibitors of purine nucleoside phosphorylase, C(8) and C(5') substitutions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1982;31:163–171. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi W, Ting L-M, Kicska GA, Lewandowicz A, Tyler PC, Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Kim K, Almo SC, Schramm VL. Plasmodium falciparum purine nucleoside phosphorylase: crystal structures, immucillin inhibitors, and dual catalytic function. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:18103–18106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ting L-M, Shi W, Lewandowicz A, Singh V, Mwakingwe A, Birck MR, Ringia EAT, Bench G, Madrid DC, Tyler PC, Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Schramm VL, Kim K. Targeting a Novel Plasmodium falciparum Purine Recycling Pathway with Specific Immucillins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:9547–9554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412693200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho MC, Shi W, Rinaldo-Matthis A, Tyler PC, Evans GB, Clinch K, Almo SC, Schramm VL. Four generations of transition-state analogues for human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4805–4812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913439107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stoeckler JD, Poirot AF, Smith RM, Parks RE, Jr, Ealick SE, Takabayashi K, Erion MD. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase. 3. Reversal of purine base specificity by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11749–11756. doi: 10.1021/bi961971n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murkin AS, Clinch K, Mason JM, Tyler PC, Schramm VL. Immucillins in custom catalytic-site cavities. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2008;18:5900–5903. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferro AJ, Barrett A, Shapiro SK. Kinetic properties and the effect of substrate analogues on 5'-methylthioadenosine nucleosidase from Escherichia coli. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1976;438:487–494. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(76)90264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guranowski AB, Chiang PK, Cantoni GL. 5'-Methylthioadenosine nucleosidase. Purification and characterization of the enzyme from Lupinus luteus seeds. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 1981;114:293–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornell KA, Swarts WE, Barry RD, Riscoe MK. Characterization of recombinant Eschericha coli 5'-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase: analysis of enzymatic activity and substrate specificity. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1996;228:724–732. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White MW, Vandenbark AA, Barney CL, Ferro AJ. Structural analogs of 5'-methylthioadenosine as substrates and inhibitors of 5'-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase and as inhibitors of human lymphocyte transformation. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1982;31:503–507. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Gainsford GJ, Schramm VL, Tyler PC. Synthesis of transition state analogue inhibitors for purine nucleoside phosphorylase and N-riboside hydrolases. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:3053–3062. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Lewandowicz A, Schramm VL, Tyler PC. Synthesis of Second-Generation Transition State Analogues of Human Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylase. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2003;46:5271–5276. doi: 10.1021/jm030305z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewandowicz A, Ringia EAT, Ting L-M, Kim K, Tyler PC, Evans GB, Zubkova OV, Mee S, Painter GF, Lenz DH, Furneaux RH, Schramm VL. Energetic Mapping of Transition State Analogue Interactions with Human and Plasmodium falciparum Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:30320–30328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewandowicz A, Schramm VL. Transition State Analysis for Human and Plasmodium falciparum Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylases. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1458–1468. doi: 10.1021/bi0359123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]