Abstract

Bacterial DNA can be damaged by reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates (RNI and ROI) generated by host immunity, as well as by antibiotics that trigger bacterial production of ROI. Thus a pathogen’s ability to repair its DNA may be important for persistent infection. A prominent role for nucleotide excision repair (NER) in disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) was suggested by attenuation of uvrB-deficient Mtb in mice. However, it was unknown if Mtb’s Uvr proteins could execute NER. Here we report that recombinant UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC from Mtb collectively bound and cleaved plasmid DNA exposed to ultraviolet (UV) irradiation or peroxynitrite. We used the DNA incision assay to test the mechanism of action of compounds identified in a high-throughput screen for their ability to delay recovery of M. smegmatis from UV irradiation. 2-(5-Amino-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-ylbenzo[f]chromen-3-one) (ATBC) but not several closely related compounds inhibited cleavage of damaged DNA by UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC without intercalating in DNA and impaired recovery of M. smegmatis from UV irradiation. ATBC did not affect bacterial growth in the absence of UV exposure, nor did it exacerbate the growth defect of UV-irradiated mycobacteria that lacked uvrB. Thus, ATBC appears to be a cell-penetrant, selective inhibitor of mycobacterial NER. Chemical inhibitors of NER may facilitate studies of the role of NER in prokaryotic pathobiology.

DNA damage and repair are central to aging and oncogenesis in higher eukaryotes (1) and to host resistance and antibiotic action in prokaryotes (2). Mechanisms of DNA repair are multiple and complex, and it can be challenging to identify the contributions of individual pathways. Candidate gene disruption is a powerful tool in studying DNA repair in prokaryotes, but the gene-deficient strains may accumulate additional mutations as a result. Small, cell-penetrant chemical compounds that selectively and abruptly inhibit prokaryotic DNA repair pathways in an entire population without the need to select mutant clones could be useful additional tools. However, to our knowledge, no such inhibitors have been described.

Mtb1 is among the most successful bacterial pathogens. Host defense against Mtb includes production of RNI and ROI (3−6). Targets of RNI and ROI include proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids (7,8). DNA lesions caused by RNI and/or ROI include base modifications, abasic sites, single- and double-strand breaks, and intrastrand cross-linking (9−13). Genetic evidence suggested that to cause tuberculosis in mice Mtb must excise bases from its chromosome that have been damaged by RNI or ROI (14,15). Thus, Mtb disrupted in uvrB(14), a gene annotated as a member of the NER pathway (16), was highly sensitive in vitro to UV irradiation as well as to RNI. Both defects were corrected by complementation with the wild-type allele (15). Mice infected with uvrB-deficient Mtb lived to old age, while mice infected with wild-type or complemented strains died prematurely of tuberculosis (15). Virulence of the uvrB-deficient strain was partially restored in iNOS-deficient mice and almost fully restored in mice lacking both iNOS and phagocyte oxidase (phox; also called NADPH oxidase 2 or NOX2) (15). Phox generates superoxide anion, which can combine with NO to produce peroxynitrite. Peroxynitrite’s degradation and reaction products can damage DNA (11). Thus, uvrB plays a key role in Mtb’s resistance to UV irradiation in vitro and to RNI and ROI in vivo. However, the mechanism of protection by uvrB was not determined, its participation in an NER pathway was speculative, and NER has not been demonstrated to act on DNA that has been damaged by peroxynitrite.

UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC have been characterized in other prokaryotes as cooperating in the incision of DNA three or four bases 3′ to bulky, helix-distorting lesions and seven bases 5′ to the damage (17,18). A multistep mechanism is initiated by ATP-dependent dimerization of UvrA and association with UvrB. The complex scans DNA for bulky adducts, loads UvrB onto DNA at the site of the lesion, and dissociates. UvrB inserts a β-hairpin between the two strands and makes direct contact with the damaged strand. UvrC is recruited to the UvrB−DNA complex and makes dual incisions flanking the damaged site. The postincision complex is displaced by the dual action of UvrD (DNA helicase II) and DNA polymerase I, which remove the incised 12-mer. The polymerase fills the gap. DNA ligase LigA seals the nicks by joining the phosphodiester bonds (17,19).

To determine whether Mtb’s UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC have enzymatic properties consistent with participation in NER, we cloned, expressed, and purified them. Their cooperative ability to cleave a UV-damaged plasmid was robust. They also cleaved DNA damaged by peroxynitrite. We combined the DNA incision assay and a whole-cell, high-throughput screen for compounds that interfere with bacterial recovery from UV irradiation to identify what to our knowledge is the first selective chemical inhibitor of NER.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial Strains and Culture

Mycobacterium smegmatis was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) with 0.2% glycerol (Sigma) and 0.05% Tween-80 (Sigma) or on Middlebrook 7H10-agar (Difco) plates with 0.5% glycerol. Escherichia coli was grown in LB broth on or LB-agar (Difco) plates. Selections used 50 μg/mL hygromycin (Invitrogen) and/or 20 μg/mL kanamycin (Sigma) for M. smegmatis and 200 μg/mL hygromycin and/or 100 μg/mL kanamycin for E. coli. The strain Msm uvrB:puvrBMtb was generated by deleting M. smegmatis uvrB by homologous recombination with selection for hygromycin resistance, followed by complementation with uvrB from Mtb on the integrative plasmid pMV306 behind a constitutive hsp60 promoter.

Cloning of Mtb uvrA, uvrB, and uvrC

uvrB was cloned from genomic Mtb DNA with the following primers: forward, 5′-GAATTCGTGCGCGCCGGCGGTCACTT-3′; reverse, 5′-CCGCAGCTCCCGCTTGAGGCTTCGAG-3′. The blunt-ended PCR product was ligated into the pT7Blue vector. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the uvrB vector, altering nt a627g (underlined base) to remove a SapI restriction site using the following primers: forward, 5′-CCCCTCCTACGAGGAGCTGGCGGTTCGC-3′; reverse, 5′-GCGAACCGCCAGCTCCTCGTAGGAGGGG-3′. uvrB with no SapI site was amplified from the resulting vector with the following primers, designed for the IMPACT system from NEB: forward, 5′-GCTGCTGGTGGTGGTGGTCATATGCGCGCCGGCGGTCACTTCGAG-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTGGTCGTCGTTGCTCTTTCGCACTTCAGGCCGGCCGCGCTCATCC-3′. uvrA was cloned from genomic Mtb DNA with these primers: forward, 5′-GCTGCTGGTGGTGGTGGTCATATGGCTGACCGCCTGATCGTCAAG-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTGGTCGTCGTTGCTCTTCCGCAGGCGCTGACGTTGCGCCGTCTG-3′. uvrC was cloned from genomic Mtb DNA with these primers: forward, 5′-GCTGCTGGTGGTGGTGGTCATATGCCAGATCCCGCAACGTATCG-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTGGTCGTCGTTGCCTTCCGCATCGCGCGGCCCCCGATGAGTCAG-3′. The resulting PCR products were all ligated into the pTYB1 and expressed in BL21 codon plus E. coli according to the IMPACT system product manual (New England Biolabs). pTYB1 vectors (New England Biolabs) are fusion vectors in which the C-terminus of the target protein is fused to the intein tag. pTYB1 uses ATG of the NdeI site in the multiple cloning region for translation initiation and contains a SapI cloning site, which allows the target gene to be cloned adjacent to the cleavage site of the intein tag; this results in the purification of a target protein without any non-native residues.

Expression and Purification of Mtb UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC Proteins

Recombinant E. coli cultures (6 L) were grown at 37 °C to an A600 of 0.6, induced by addition of IPTG to 0.1 mM, and maintained at 18 °C for 16 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 mL of BA buffer [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% NP40], crushed by two passes through a French pressure cell at 20000 psi, and centrifuged at 16000 rpm in a Sorvall SS34 rotor for 30 min. Subsequent procedures were performed at 0−4 °C. The supernatant was passed onto a column (50 mL bed volume) of chitin beads (New England Biolabs) equilibrated in the same buffer. The column was washed with 1 L of BA buffer, followed by a second wash with 100 mL of buffer BA containing 50 mM DTT. The columns were left overnight at 4 °C, and the proteins were then eluted with 100 mL of BA buffer without DTT. Eluates were dialyzed against buffer BB [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM PMSF] and loaded on a 1 mL column of Q-Sepharose (equilibrated in the same buffer), which was washed with 10 mL of modified BB (KCl increased to 150 mM), followed by stepwise elution with 5 mL of buffer BB buffer (KCl increased to 300 mM) and 5 mL of BB buffer (KCl increased to 600 mM). Fractions were monitored by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions (SDS−PAGE). UvrA eluted mostly in the 300 mM KCl elution step; UvrB eluted both in the 300 mM KCl step and the 600 mM KCl step, and UvrC did not bind to Q-Sepharose. UvrC protein was further purified on SP-Sepharose (1 mL bed volume), washed with BB buffer containing 150 mM KCl, and eluted with buffer BB (300 mM KCl). Fractions containing Uvr proteins were distributed in small aliquots and stored at −80 °C.

DNA Incision Assay

Plasmid pBluescript II DNA SK+ (Stratagene) was purified by a modification of the procedure of Cunningham et al. (20). Lysozyme-treated cells were lysed with Sarkosyl and ultracentrifuged. Supernatant was extracted with phenol and treated with RNase. DNA was purified on an ion-exchange resin (Qiagen), eluted with 55% ethanol and 0.1 M NaCl, and further purified by velocity sedimentation in a neutral sucrose gradient (21,22). The negatively supercoiled plasmid contained 5−20% dimers and/or nicked forms. One microliter of plasmid DNA (500 nM) in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 1 mM EDTA (TE) was spotted on parafilm and irradiated at 400 J/m2 unless otherwise indicated using a cross-linker (Stratagene). Plasmid DNA was dialyzed in 150 mM sodium or potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 25 mM NaHCO3, and 1 mM EDTA. Dialyzed plasmid (250 nM) was incubated with various concentrations of peroxynitrite prepared as described (23) for 30 min at room temperature and stored at 4 °C. Unless otherwise indicated, DNA (25 nM in a final volume of 15 μL) was incubated with UvrA for 10 min at 37 °C in buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 100 μg/mL BSA, and 1 mM DTT, followed by addition of UvrB for 20 min at 37 °C and then UvrC for 30 min. Reactions were stopped with proteinase K (1.7 mg/mL) and SDS (1.2%). After 15 min at 37 °C, EDTA and loading dye were added and products resolved on 1% agarose gels. Where indicated, we monitored the ability of Bacillus caldotenax UvrA and UvrB and Thermatoga maritima UvrC to excise an oligonucleotide fragment containing a fluoresceinated base from the central position of a 50-bp oligonucleotide, as described (24).

Use of Formamidopyrimidine DNA Glycosylase (Fpg) To Probe for the Presence of Oxidized Bases

Peroxynitrite-treated plasmid (25 nM) was incubated with Fpg (New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 37 °C in a buffer containing 10 mM Bis-Tris propane-HCl (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT. Reactions were stopped with SDS/proteinase K and processed as above.

DNA Intercalation Assay

Topo I relaxed plasmid (25 nM) was incubated with increasing concentrations (1, 10, 100 μM) of compounds or with the same concentrations of ethidium bromide in the presence of Topo I buffer (Fermentas) for 10 min at 37 °C. Three units of wheat germ Topo I was added and incubated for additional 30 min. Samples were treated with SDS/proteinase K, loaded on 1% agarose, and imaged after ethidium bromide staining.

High-Throughput Screening

Thirty-eight thousand compounds with drug-like properties from ChemDiv and Chembridge were screened at the Rockefeller University-Weill Cornell Medical College High Throughput Screening Resource Center in 384-well plates as described in Supporting Information. The screening concentration (19 μM) was within a range often used for whole-cell screens against mycobacteria (e.g., ref (25)). Each compound was tested on Msm uvrB:puvrB(Mtb) that was or was not UV-irradiated. Candidate actives were those that selectively delayed recovery of the bacteria from UV irradiation.

Results

Deficiency of uvrA Phenocopies Deficiency of uvrB

The genetic screen that identified uvrB as required for Mtb to resist acidified nitrite did not also identify uvrA or uvrC(14). Negative results in genetic screens are difficult to interpret. Nonetheless, this gap in knowledge left it unclear if attenuation in mice of uvrB-deficient Mtb implied an important role for NER in pathogenesis (15). Here, using the same library of transposon mutants as earlier (14), we isolated uvrA-deficient Mtb on the basis of its resistance to acidified nitrite and found that it phenocopied the RNI sensitivity of uvrB-deficient Mtb (Supporting Information Figure S1). It is not clear why the uvrA-deficient mutant was not identified earlier. A uvrC-deficient mutant may not be present in the mutant library. Alternatively, besides UvrC, Mtb encodes Rv2191, a conserved hypothetical protein with 25.7% identity to E. coli UvrC PO7028 in a 230 amino acid overlap. This or another enzyme may provide a redundant function. The similar RNI sensitivity of uvrA-deficient and uvrB-deficient Mtb provided genetic evidence that their protein products are likely to function in the same pathway.

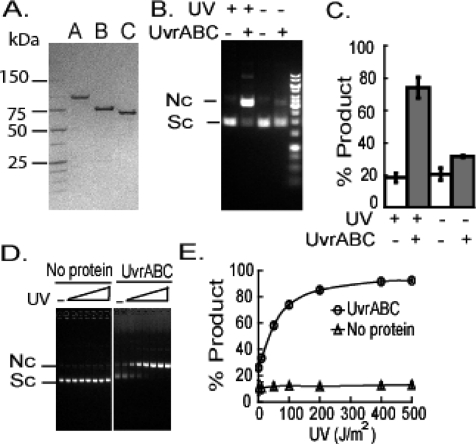

Mtb’s UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC Cooperatively Incise UV-Damaged DNA in Vitro

To test the biochemical functions of the Mtb proteins encoded by uvrB, uvrA, and uvrC, we cloned the genes and expressed and purified the proteins. The proteins migrated on 4−20% SDS−PAGE with the predicted molecular mass of 106 kDa (UvrA), 76 kDa (UvrB), and 68 kDa (UvrC) (Figure 1A). Classic substrates of NER include pyrimidine dimers and 6-4 photoproducts formed by UV irradiation of DNA (26−31). Mtb UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC displayed strong, UV damage-dependent incision activity against an irradiated plasmid, as monitored by the shift in mobility of the supercoiled DNA to that of the open, nicked form (27) (Figure 1B,C). The proportion of plasmids that were incised increased with the dose of UV to which the DNA had been exposed (Figure 1D,E). Incision activity was maximal at a ratio of UvrA:UvrB:UvrC = 1:2:3 (Supporting Information Figure S2), at a physiologic concentration of ATP (1−5 mM) (32) (Supporting Information Figure S3), and at the pH of the Mtb cytosol (33) (Supporting Information Figure S4). Loading of UvrB on the DNA depended on damage as well as on UvrA, and the binding of UrvA and UvrB was cooperative (Supporting Information Figure S5).

Figure 1.

Incision activity of Mtb UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC on UV-damaged plasmid substrate: dependence on UV irradiation and Uvr proteins. (A) UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC (∼30 pmol each) were resolved on 4−20% SDS−PAGE along with protein standards whose molecular masses are indicated in kDa. The Uvr proteins migrated as predicted for proteins of 106, 76, and 68 kDa, respectively. (B) UV-irradiated or unirradiated plasmid DNA (25 nM) was incubated with or without 100 nM UvrA, 300 nM UvrB, and 150 nM UvrC. UvrABC denotes the combination of UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC proteins. Sc denotes supercoiled plasmid, and Nc denotes nicked circular. (C) The graph shows the means ± SD from eight independent experiments for UV-irradiated plasmid and four independent experiments for the nonirradiated plasmid. Gray-colored bars indicate addition of UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC at the same concentrations as in (B). (D) Plasmid DNA (25 nM) was irradiated with increasing UV doses (0, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 500 J/m2) and then incubated with or without Uvr proteins (100 nM UvrA for 10 min, 300 nM UvrB for 20 min, and 150 nM UvrC for 30 min) at 37 °C. (E) Graph of means ± SD for percent incision of triplicates in one experiment.

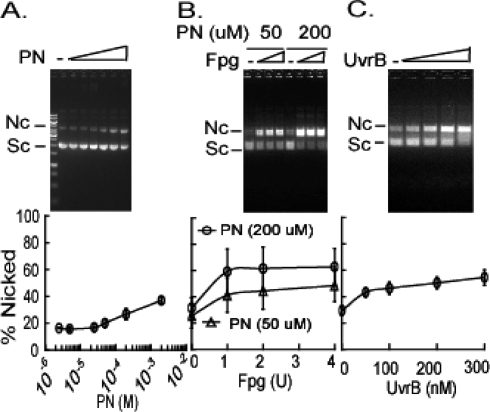

Mtb UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC Have NER Activity with Peroxynitrite-Treated DNA as a Substrate

Reversion of uvrB-deficient Mtb to full virulence in mice lacking both iNOS and phox implied that peroxynitrite, a product of the interaction of ·NO and O2·−, might damage DNA in a manner that requires NER for Mtb’s continued survival (15). To our knowledge, however, peroxynitrite-damaged DNA has not been shown to serve as a substrate for NER. We treated superhelical plasmid DNA with peroxynitrite in the presence of bicarbonate, because decomposition of peroxynitrite in a mammalian host is likely to generate not only OH· and NO2· but also nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONOOCO2) (11). When we added bicarbonate, there was likely to be a mixture of peroxynitrite and nitrosoperoxycarbonate. For simplicity, the notation “PN” in the figures is intended to refer to this mixture. We used cleavage by formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase (Fpg) to monitor the oxidation of DNA (11,34). Fpg acts as an N-glycosylase to remove damaged purines from double-stranded DNA and also as an apurinic lyase that cleaves 3′ and 5′ of the apurinic site (35−37). The peroxynitrite/nitrosoperoxycarbonate mixture (“PN”) nicked nearly as many DNA molecules as it oxidized (Figure 2A). Thus, most of the DNA that was oxidized enough to serve as a substrate for NER was already positive in the DNA incision assay before addition of the Uvr proteins, with the result that the incision assay with peroxynitrite-treated DNA had a high background and narrow dynamic range (Figure 2B). Nonetheless, it was clear that UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC collectively incised peroxynitrite-treated DNA in a UvrB concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Nucleotide incision of peroxynitrite-damaged plasmid DNA by Fpg and Mtb UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC proteins. (A) Plasmid DNA (0.5 mg/mL) was incubated with increasing concentrations of peroxynitrite (PN) in buffer containing 150 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and 25 mM sodium bicarbonate. The DNA (500 ng) was resolved on 1% agarose gels, and percent nicked products was plotted vs concentration of PN. The data show means ± SD from three independent experiments (lower panel). Error bars fall within the symbols. (B) Plasmid (25 nM) treated with PN (open triangles, 50 μM; open circles, 200 μM) and incubated with increasing amounts of Fpg. Means ± SD from three independent experiments (lower panel). (C) Plasmid (25 nM) treated with PN (5.0 × 10−5 M) was incubated with 100 nM UvrA, increasing concentrations of UvrB (0, 50, 100, 200, or 300 nM), and 150 nM UvrC. The data show means ± SD from three independent experiments (lower panel).

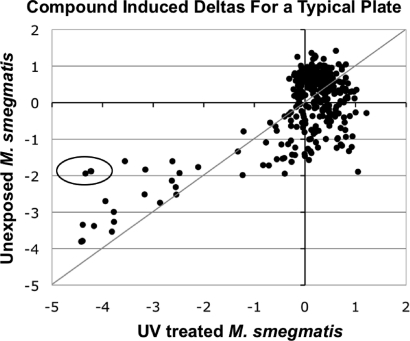

High-Throughput Whole-Cell Screen for Candidate Inhibitors of NER

To screen for inhibitors of NER that can enter and function in mycobacteria, we turned to the nonpathogenic M. smegmatis, because we lacked robotics in the biologic safety conditions required for Mtb. M. smegmatis deficient in UvrB is sensitive to UV and other DNA damaging agents (38,39). We knocked out uvrB in M. smegmatis and replaced the gene with its Mtb homologue. As expected, M. smegmatis lacking uvrB was hypersensitive to killing by UV irradiation (Supporting Information Figure S6). This defect was fully complemented by uvrB from Mtb in the strain termed Msm uvrB:puvrB(Mtb) (Supporting Information Figure S6), the strain used for the screen. We screened 38000 small chemical compounds from a commercial diversity collection for those which did not retard growth of Msm uvrB::puvrB(Mtb) in 384-well plates at 19 μM, but which markedly delayed recovery of the bacteria following exposure to 40 J/m2 of UV irradiation, as assessed by reduction of the resazurin in Alamar Blue to a fluorescent product. Supporting Information Figure S7 illustrates raw data from screening two 384-well plates containing the same set of compounds. In one plate the mycobacteria had been UV-irradiated and in the other, not. Figure 3 depicts the data analysis for this pair of plates. Two compounds from this set were considered candidate actives. Overall, 400 (1%) of the compounds impaired growth by >3 SD of the mean, while 57 would be expected by chance. Of the 400, 91 (0.2% of the compounds screened) were consistently active when rescreened. We obtained 75 of the 91 as fresh powders and used them in the DNA incision assay to assess if they might be inhibitors of the concerted action of UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC. Alternatively, the compounds might inhibit some other aspect of the process by which cells recover from UV irradiation, such as the SOS response by which UV irradiation upregulates the Uvr pathway.

Figure 3.

Example of identification of candidate actives in HTS. Plot of standardized fluorescence values from Alamar Blue reduction in each test well in one 384-well plate exposed to UV irradiation and an unexposed companion plate. The circled compounds were associated with a difference in standardized values with and without UV irradiation that was greater than 3 SD from the mean of such differences for the plate. The raw data are shown in Supporting Information Figure S7.

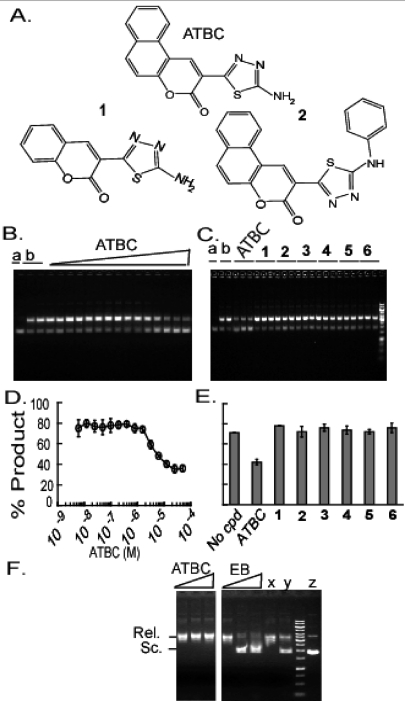

In fact, when tested at 50 μM, 10 of the 75 compounds identified in the whole cell screen interfered with NER activity as assayed by plasmid incision, with IC50’s ranging from 4 to 30 μM. The most potent of the 10 compounds was 2-(5-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl-benzo[f]chromen-3-one) (ATBC) (Figure 4). Saturation of the effect of ATBC around 50 μM may reflect, in part, its limited solubility (under 80 μM) under these assay conditions. The inactivity (Figure 4C) of six congeners of ATBC (compounds 1 and 2 in Figure 4A; compounds 3, 4, 5, and 6 in Supporting Information Figure S8) at 50 μM suggested the importance of both the primary amine on the thiadiazole of ATBC and the benzyl ring on the chromene. To test if ATBC inhibited incision by intercalating into the DNA substrate, we monitored DNA intercalation by an assay that measures alteration of the topology of relaxed, covalently closed circular plasmid. We incubated relaxed DNA plasmid with ATBC or ethidium bromide, a known intercalator. An intercalator would be expected to untwist the DNA double helix. In a covalently closed circular molecule, this would lead to compensatory induction of positive superhelical turns. Subsequent reapplication of topoisomerase I would relax the positive superhelical turns. Upon removal of test agent and topoisomerase during electrophoresis, the plasmid would undergo a corresponding number of negative superhelical turns, detectable by an increase in electrophoretic mobility. As expected, faster migrating topoisomers were observed when the DNA was treated with ethidium bromide, but no change in mobility was observed following exposure to ATBC (Figure 4F). Structures and activities of the other nine compounds are shown in Supporting Information Figure S8. Six of them were DNA intercalators (Supporting Information Figure S9) and were thus considered false positives.

Figure 4.

ATBC inhibits plasmid incision by Mtb UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC without intercalating in DNA. (A) Compound structures of ATBC and related compounds 1 and 2. (B) Inhibition of NER activity by ATBC in a concentration-dependent manner. Irradiated plasmid DNA (25 nM) incubated with Uvr proteins (100 nM UvrA for 10 min, 300 nM UvrB for 20 min, and 150 nM UvrC for 30 min at 37 °C) in the presence of increasing concentrations of compound ATBC (0−5 × 10−5 M); lanes a and b show DNA plasmid substrate without or with UvrABC, respectively. (C) ATBC but not closely related congeners inhibit NER activity. Irradiated plasmid DNA (25 nM) was incubated with Uvr proteins as in (B) in the presence of ATBC or analogues 1−6 at 50 μM. (D) and (E) are plots of data from (B) and (C), respectively; means ± SD from triplicates. (F) Lack of intercalation. ATBC (1, 10, or 100 μM) was incubated with relaxed circular plasmid (25 nM) in the presence of 3 units of topoisomerase I for 45 min at 37 °C. The same concentrations of ethidium bromide were tested as a positive control. Samples were processed as described in Experimental Procedures. Compounds were omitted in lanes x (relaxed plasmid) and y (supercoiled plasmid). Topoisomerase was omitted in lane z, which contained only supercoiled plasmid. Lanes are from a single gel in one experiment representative of three. Intervening lanes with unrelated compounds were removed from the image.

In addition, ATBC inhibited incision activity of the B. caldotenax UvrA and UvrB and T. maritima UvrC by 50% on a 50-bp fragment containing a fluorescein-modified thymine as a substrate (24). Thus, activity of the inhibitor is not unique to one set of Uvr proteins nor to one assay for their activity (Supporting Information Figure S10).

In order to better understand how the compound acts, we measured changes in intrinsic fluorescence of the Uvr proteins upon exposure to ATBC. Preliminary studies suggested that ATBC binds Mtb’s UvrA, but results with UvrB and UvrC were difficult to interpret (not shown).

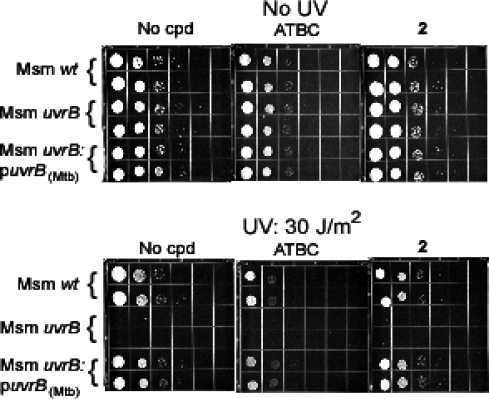

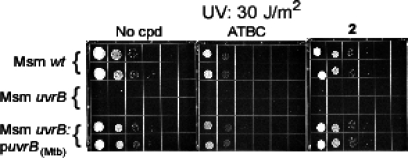

ATBC Selectively Impairs Recovery of M. smegmatis from UV Irradiation

ATBC and its inactive congener compound 2 were incorporated in agar at 25 μM. Wild-type, uvrB-deficient, and uvrBMtb-complemented strains of M. smegmatis were plated in 10-fold serial dilutions and exposed or not to UV irradiation. ATBC impaired the recovery of M. smegmatis, but only when the M. smegmatis or Mtb uvrB gene was intact (Figure 5). ATBC did not impair the growth of nonirradiated M. smegmatis (Figure 5) and did not add to the recovery defect of irradiated, uvrB-deficient M. smegmatis, as evident at lower UV doses (Supporting Information Figure S11). Compound 2 had no effect (Figure 5). Thus, ATBC acted on intact mycobacteria in a selective manner to impair uvrB-dependent recovery from UV irradiation, and its ability to do so correlated with its ability to inhibit DNA incision in vitro by mycobacterial UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC.

Figure 5.

ATBC retards growth of M. smegmatis after UV exposure. Serial dilutions of single cell suspensions of M. smegmatis strains from 2.5 × 104 to 2.5 cfu were spotted on 7H10 agar plates in the absence (“No cpd”) or presence of ATBC or its inactive congener compound 2 at 25 μM. Three plates were unirradiated (upper panel), and three were exposed to UV at 30 J/m2 (lower panel). Similar results were obtained in an independent experiment where doses of UV and ATBC concentrations were varied. The ATBC effect was maximal at 25 μM.

Discussion

The genetic and chemical−biologic evidence presented here supports three conclusions. First, Mtb’s uvrA, uvrB, and uvrC encode proteins that function collectively in vitro to cleave UV-damaged DNA. This provides biochemical evidence in support of the annotation of these genes as serving in a NER pathway (16). Biochemical studies of mycobacterial UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC have not previously been reported.

Second, Mtb’s UvrA, UvrB, and UvrC can cleave DNA damaged by peroxynitrite/nitrosoperoxycarbonate (here collectively called “PN”). From a biochemical perspective, this is the first evidence to our knowledge that PN-damaged DNA can serve as a substrate for NER. From a biological perspective, this helps to account for the observations that Mtb depends on UrvB to cause life-shortening tuberculosis in mice, provided the mice express both iNOS and phox (15). The ability of Mtb’s NER proteins to cleave PN-damaged DNA in vitro supports the inference that iNOS- and phox-dependent formation of peroxynitrite in vivo leads to critical damage to Mtb’s DNA in such a way that NER is required for its repair. This strengthens the evidence that generation of peroxynitrite can be a critical determinant of host antimicrobial defense, that DNA can be its critical target, and that NER, which is only one of several DNA repair pathways in Mtb, can be a key mechanism of bacterial resistance to host immunity.

Besides NER, Mtb encodes genes homologous to those in other organisms that participate in base excision repair, recombination, SOS repair, nonhomologous end-joining, alkylation damage repair, and damage-induced mutagenesis pathways (40−45). In Salmonella enterica var. Typhimurium, mutants in enzymes involved in base excision repair displayed increased sensitivity to iNOS-derived RNI in association with chromosomal fragmentation, were hypermutable and attenuated in mice, and were restored to virulence in mice treated with an iNOS inhibitor (46). It is not clear what determines the relative importance of NER, base excision repair, and other DNA repair pathways in different pathogens or circumstances.

Finally, ATBC is a relatively selective, cell-penetrant inhibitor of mycobacterial NER. It remains to be determined whether ATBC binds to UvrA, UvrB, or UvrC. Alternatively, ATBC may bind to surfaces between the proteins or between them and DNA, but it does not seem to intercalate in DNA. In addition, ATBC inhibited incision activity of the B. caldotenax UvrA and UvrB and T. maritima UvrC on a 50-bp fragment containing a fluorescein-modified thymine as a substrate (24). Thus, this class of inhibitors may be useful across several species of bacteria.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. K. Holloman (Weill Cornell Medical College) for advice; G. Lin, R. Bryk, and J. Roberts (Weill Cornell Medical College) for assistance; and the staff of the High Throughput Screening Resource Center (Rockefeller University). The Department of Microbiology and Immunology is supported by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation.

Supporting Information Available

Supplemental methods and the following figures: S1, sensitivity of transposon mutants in uvrA and uvrB genes to acidified nitrite; S2, incision activity of Mtb UvrABC on UV-damaged plasmid substrate; S3, dependence of UV-damaged plasmid incision by UvrABC on physiological ATP concentrations; S4, dependence of UV-damaged plasmid incision by UvrABC on physiological pH; S5, UvrA and DNA damage dependence of UvrB loading on UV-damaged DNA; S6, complementation of the uvrB deletion; S7, raw fluorescence data for the two 384-well plates illustrated in Figure 3; S8, structures of ATBC related compounds; S9, structures, IC50s, and DNA intercalation assay results for other compounds that exhibited inhibition of NER activity in vitro; S10, inhibition by ATBC of incision activity of B. caldotenax UvrA and UrvB and T. maritima UrvC on a fluoresceinated plasmid substrate; and S11, lack of effect of ATBC on UvrB-deficient M. smegmatis at a UV dose low enough to allow its recovery. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This work was supported by NIH Grant AI064768 (C.N.), the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH (B.V.H.), and NIH Grant ES 019566 (B.V.H.).

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ATBC, 2-(5-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-ylbenzo[f]chromen-3-one); Fpg, formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; NER, nucleotide excision repair; NOX2, phagocyte oxidase; ROI, reactive oxygen intermediates; RNI, reactive nitrogen intermediates; UV, ultraviolet.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hoeijmakers J. H. (2009) DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1475–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanski M. A.; Dwyer D. J.; Collins J. J. (2010) How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 423–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking J. D.; North R. J.; LaCourse R.; Mudgett J. S.; Shah S. K.; Nathan C. F. (1997) Identification of nitric oxide synthase as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 5243–5248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C.; Gold B.; Lin G.; Stegman M.; de Carvalho L. P.; Vandal O.; Venugopal A.; Bryk R. (2008) A philosophy of anti-infectives as a guide in the search for new drugs for tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 88, Suppl. 1S25–S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. (2006) Role of iNOS in human host defense. Science 312, 1874−1875 (author reply 1874−1875). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante J.; Zhang S. Y.; von Bernuth H.; Abel L.; Casanova J. L. (2008) From infectious diseases to primary immunodeficiencies. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 28, 235–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo C. (2003) Multiple pathways of peroxynitrite cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 140−141, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez B.; Radi R. (2003) Peroxynitrite reactivity with amino acids and proteins. Amino Acids 25, 295–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman P. E.; Ames B. N.; Roth J. R.; Barnes W. M.; Levin D. E. (1986) Target sequences for mutagenesis in Salmonella histidine-requiring mutants. Environ. Mutagen. 8, 631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro R.; Dubelman S.; Feinberg A. M.; Crain P. F.; McCloskey J. A. (1977) Isolation and identification of cross-linked nucleosides from nitrous acid treated deoxyribonucleic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 302–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M.; Vongchampa V.; Gingipalli L.; Cloutier J. F.; Kow Y. W.; O’Connor T.; Dedon P. C. (2006) Development of enzymatic probes of oxidative and nitrosative DNA damage caused by reactive nitrogen species. Mutat. Res. 594, 120–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedon P. C.; Tannenbaum S. R. (2004) Reactive nitrogen species in the chemical biology of inflammation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 423, 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M.; Wang C.; Deen W. M.; Dedon P. C. (2003) Absence of 2′-deoxyoxanosine and presence of abasic sites in DNA exposed to nitric oxide at controlled physiological concentrations. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 16, 1044–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin K. H.; Ehrt S.; Gutierrez-Ramos J. C.; Weich N.; Nathan C. F. (2003) The proteasome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for resistance to nitric oxide. Science 302, 1963–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin K. H.; Nathan C. F. (2005) Role for nucleotide excision repair in virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 73, 4581–4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. T.; Brosch R.; Parkhill J.; Garnier T.; Churcher C.; Harris D.; Gordon S. V.; Eiglmeier K.; Gas S.; Barry C. E. 3rd; Tekaia F.; Badcock K.; Basham D.; Brown D.; Chillingworth T.; Connor R.; Davies R.; Devlin K.; Feltwell T.; Gentles S.; Hamlin N.; Holroyd S.; Hornsby T.; Jagels K.; Krogh A.; McLean J.; Moule S.; Murphy L.; Oliver K.; Osborne J.; Quail M. A.; Rajandream M. A.; Rogers J.; Rutter S.; Seeger K.; Skelton J.; Squares R.; Squares S.; Sulston J. E.; Taylor K.; Whitehead S.; Barrell B. G. (1998) Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393, 537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houten B.; Croteau D. L.; DellaVecchia M. J.; Wang H.; Kisker C. (2005) “Close-fitting sleeves”: DNA damage recognition by the UvrABC nuclease system. Mutat. Res. 577, 92–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truglio J. J.; Croteau D. L.; Van Houten B.; Kisker C. (2006) Prokaryotic nucleotide excision repair: the UvrABC system. Chem. Rev. 106, 233–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truglio J. J.; Karakas E.; Rhau B.; Wang H.; DellaVecchia M. J.; Van Houten B.; Kisker C. (2006) Structural basis for DNA recognition and processing by UvrB. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham R. P.; DasGupta C.; Shibata T.; Radding C. M. (1980) Homologous pairing in genetic recombination: recA protein makes joint molecules of gapped circular DNA and closed circular DNA. Cell 20, 223–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazloum N.; Holloman W. K. (2009) Second-end capture in DNA double-strand break repair promoted by Brh2 protein of Ustilago maydis. Mol. Cell 33, 160–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazloum N.; Zhou Q.; Holloman W. K. (2008) D-loop formation by Brh2 protein of Ustilago maydis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 524–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk R.; Griffin P.; Nathan C. (2000) Peroxynitrite reductase activity of bacterial peroxiredoxins. Nature 407, 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau D. L.; DellaVecchia M. J.; Wang H.; Bienstock R. J.; Melton M. A.; Van Houten B. (2006) The C-terminal zinc finger of UvrA does not bind DNA directly but regulates damage-specific DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26370–26381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthan S.; Faaleolea E. R.; Goldman R. C.; Hobrath J. V.; Kwong C. D.; Laughon B. E.; Maddry J. A.; Mehta A.; Rasmussen L.; Reynolds R. C.; Secrist J. A. III; Shindo N.; Showe D. N.; Sosa M. I.; Suling W. J.; White E. L. (2009) High-throughput screening for inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 89, 334–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y.; Ma H.; Minko I. G.; Shell S. M.; Yang Z.; Qu Y.; Xu Y.; Geacintov N. E.; Lloyd R. S. (2004) DNA damage recognition of mutated forms of UvrB proteins in nucleotide excision repair. Biochemistry 43, 4196–4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancar A.; Rupp W. D. (1983) A novel repair enzyme: UVRABC excision nuclease of Escherichia coli cuts a DNA strand on both sides of the damaged region. Cell 33, 249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. C.; Morton A. G.; Bohr V. A.; Sancar A. (1988) General method for quantifying base adducts in specific mammalian genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 3723–3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung A. T.; Mattes W. B.; Oh E. Y.; Grossman L. (1983) Enzymatic properties of purified Escherichia coli uvrABC proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 6157–6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin W. A.; Haseltine W. A. (1984) Removal of UV light-induced pyrimidine-pyrimidone(6−4) products from Escherichia coli DNA requires the uvrA, uvrB, and urvC gene products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 3821–3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles G. M.; Van Houten B.; Sancar A. (1987) Utilization of DNA photolyase, pyrimidine dimer endonucleases, and alkali hydrolysis in the analysis of aberrant ABC excinuclease incisions adjacent to UV-induced DNA photoproducts. Nucleic Acids Res. 15, 1227–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koul A.; Vranckx L.; Dendouga N.; Balemans W.; Van den Wyngaert I.; Vergauwen K.; Gohlmann H. W.; Willebrords R.; Poncelet A.; Guillemont J.; Bald D.; Andries K. (2008) Diarylquinolines are bactericidal for dormant mycobacteria as a result of disturbed ATP homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25273–25280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandal O. H.; Pierini L. M.; Schnappinger D.; Nathan C. F.; Ehrt S. (2008) A membrane protein preserves intrabacterial pH in intraphagosomal Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 14, 849–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epe B.; Ballmaier D.; Roussyn I.; Briviba K.; Sies H. (1996) DNA damage by peroxynitrite characterized with DNA repair enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 4105–4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatahet Z.; Kow Y. W.; Purmal A. A.; Cunningham R. P.; Wallace S. S. (1994) New substrates for old enzymes. 5-Hydroxy-2′-deoxycytidine and 5-hydroxy-2′-deoxyuridine are substrates for Escherichia coli endonuclease III and formamidopyrimidine DNA N-glycosylase, while 5-hydroxy-2′-deoxyuridine is a substrate for uracil DNA N-glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18814–18820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchou J.; Bodepudi V.; Shibutani S.; Antoshechkin I.; Miller J.; Grollman A. P.; Johnson F. (1994) Substrate specificity of Fpg protein. Recognition and cleavage of oxidatively damaged DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 15318–15324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiteux S.; Gajewski E.; Laval J.; Dizdaroglu M. (1992) Substrate specificity of the Escherichia coli Fpg protein (formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase): excision of purine lesions in DNA produced by ionizing radiation or photosensitization. Biochemistry 31, 106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurthkoti K.; Kumar P.; Jain R.; Varshney U. (2008) Important role of the nucleotide excision repair pathway in Mycobacterium smegmatis in conferring protection against commonly encountered DNA-damaging agents. Microbiology 154, 2776–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthlein C.; Wanner R. M.; Sander P.; Davis E. O.; Bosshard M.; Jiricny J.; Bottger E. C.; Springer B. (2009) Characterization of the mycobacterial NER system reveals novel functions of the uvrD1 helicase. J. Bacteriol. 191, 555–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F.; Ndwandwe D. E.; Abrahams G. L.; Kana B. D.; Machowski E. E.; Venclovas C.; Mizrahi V. (2010) Essential roles for imuA′- and imuB-encoded accessory factors in DnaE2-dependent mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13093–13098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C.; Bongiorno P.; Martins A.; Stephanou N. C.; Zhu H.; Shuman S.; Glickman M. S. (2005) Mechanism of nonhomologous end-joining in mycobacteria: a low-fidelity repair system driven by Ku, ligase D and ligase C. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C.; Martins A.; Bongiorno P.; Glickman M.; Shuman S. (2004) Biochemical and genetic analysis of the four DNA ligases of mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20594–20606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della M.; Palmbos P. L.; Tseng H. M.; Tonkin L. M.; Daley J. M.; Topper L. M.; Pitcher R. S.; Tomkinson A. E.; Wilson T. E.; Doherty A. J. (2004) Mycobacterial Ku and ligase proteins constitute a two-component NHEJ repair machine. Science 306, 683–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Vultos T.; Mestre O.; Tonjum T.; Gicquel B. (2009) DNA repair in Mycobacterium tuberculosis revisited. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 471–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbach S. I.; Springer B.; Machowski E. E.; North R. J.; Papavinasasundaram K. G.; Colston M. J.; Bottger E. C.; Mizrahi V. (2003) DNA alkylation damage as a sensor of nitrosative stress in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 71, 997–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A. R.; Soliven K. C.; Castor M. E.; Barnes P. D.; Libby S. J.; Fang F. C. (2009) The base excision repair system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium counteracts DNA damage by host nitric oxide. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.