The pea flowering gene GIGAS regulates a mobile flowering signal and is essential for flowering under long days but not for the ability to respond to photoperiod. This study characterizes the FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) gene family in pea, identifies one gene (FTa1) as GIGAS, and associates another gene (FTb2) with a second mobile signal and a broader role in photoperiod responsiveness.

Abstract

Garden pea (Pisum sativum) was prominent in early studies investigating the genetic control of flowering and the role of mobile flowering signals. In view of recent evidence that genes in the FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) family play an important role in generating mobile flowering signals, we isolated the FT gene family in pea and examined the regulation and function of its members. Comparison with Medicago truncatula and soybean (Glycine max) provides evidence of three ancient subclades (FTa, FTb, and FTc) likely to be common to most crop and model legumes. Pea FT genes show distinctly different expression patterns with respect to developmental timing, tissue specificity, and response to photoperiod and differ in their activity in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana, suggesting they may have different functions. We show that the pea FTa1 gene corresponds to the GIGAS locus, which is essential for flowering under long-day conditions and promotes flowering under short-day conditions but is not required for photoperiod responsiveness. Grafting, expression, and double mutant analyses show that GIGAS/FTa1 regulates a mobile flowering stimulus but also provide clear evidence for a second mobile flowering stimulus that is correlated with expression of FTb2 in leaf tissue. These results suggest that induction of flowering by photoperiod in pea results from interactions among several members of a diversified FT family.

INTRODUCTION

In many species, the timing of flowering is regulated by a number of environmental factors, including daylength and temperature, and much recent effort has been directed toward understanding the molecular mechanisms that underlie this regulation. The Arabidopsis thaliana FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) gene has an important position within the genetic hierarchy that controls flowering and integrates photoperiod, temperature, vernalization, and light quality signaling. FT encodes a small protein with similarities to mammalian phosphatidylethanolamine binding domain protein (PEBP) (Kardailsky et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 1999). Arabidopsis FT is expressed in leaves under flowering-inductive conditions, and the FT protein moves through the phloem to the shoot apex where it binds to the bZIP transcription factor FD to activate transcription of the floral meristem identity gene APETALA1 (AP1) and possibly other related MADS domain genes (Abe et al., 2005; Wigge et al., 2005; Corbesier et al., 2007; Jaeger and Wigge, 2007; Mathieu et al., 2007). FT-like proteins from several different species have been shown to function in a manner similar to FT with respect to induction of flowering, transport in phloem, and interaction with FD-like proteins (Lifschitz et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2007; Tamaki et al., 2007; Li and Dubcovsky, 2008), suggesting that this general mechanism is likely to be widely conserved across flowering plants.

In Arabidopsis, FT is part of a small gene family (the so-called PEBP family) with five other members: TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF), TERMINAL FLOWER1 (TFL1), Arabidopsis thaliana CENTRORADIALIS homolog, MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (MFT), and BROTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (BFT) (Bradley et al., 1997; Mimida et al., 2001; Yoo et al., 2004, 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2005). PEBP gene families in other plant species vary in size, ranging from five genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) to around 20 in rice (Oryza sativa) and maize (Zea mays) (Carmel-Goren et al., 2003; Chardon and Damerval, 2005; Danilevskaya et al., 2008; Igasaki et al., 2008). Phylogenetic analysis resolves three major clades within this family, corresponding to FT-like, TFL1-like, and MFT-like genes. FT-like genes promote flowering, whereas TFL1-like genes delay flowering and prevent conversion of the shoot apical meristem into a floral meristem (Bradley et al., 1996; Bradley et al., 1997; Pnueli et al., 1998; Foucher et al., 2003). In Arabidopsis, the opposing functions of FT and TFL1 have been suggested to derive from a single amino acid difference within a divergent external loop in the fourth exon (Hanzawa et al., 2005; Ahn et al., 2006), and TFL1 has been suggested to act as a competitor of FT, potentially through competitive binding to FD (Ahn et al., 2006). The Arabidopsis FT-like clade has two members: FT itself and a close paralog, TSF. The FT and TSF genes encode very similar proteins and have a similar proximal promoter and similar patterns of regulation with respect to photoperiod and vernalization (Yamaguchi et al., 2005). TSF has a small effect on flowering additive with FT, and the TSF protein, like FT, can act as a mobile inducer of flowering when expressed in the phloem (Jang et al., 2009). In contrast with the similarity in regulation of FT and TSF, multiple FT-like genes in other species show marked differences in regulation (Faure et al., 2007; Kikuchi et al., 2009; Blackman et al., 2010).

The legumes are a large plant group that are present in most ecosystems and include many important crop species. Most crop and model legumes fall into two distinct clades: the so-called galegoid legumes (including pea [Pisum sativum], Medicago, Lotus, lentil [Lens culinaris], and chickpea [Cicer arietinum]), which are predominantly vernalization-responsive long-day plants from temperate regions, and the warm season millettioid legumes (including bean [Phaseolus vulgaris], soybean [Glycine max], and cowpea [Vigna unguiculata]) that originate from lower latitudes and are predominantly short-day plants (Cannon et al., 2009).We are investigating the genetic control of flowering in garden pea, a long-day, vernalization-responsive legume that was extensively used in early work on the genetic control of mobile flowering signals (Weller et al., 1997, 2009b). Recently, several pea loci controlling photoperiod responsiveness and mobile flowering signals have been shown to be orthologs of Arabidopsis genes involved in circadian clock function. These include LATE BLOOMER1 (LATE1) and DIE NEUTRALIS (DNE), which are orthologs of Arabidopsis GIGANTEA and EARLY FLOWERING4, respectively (Hecht et al., 2007; Liew et al., 2009). In view of the potential importance of FT genes in mobile floral signaling, we defined the FT gene family in pea, Medicago, and soybean and investigated the regulation of the pea FT family, documenting distinct expression patterns for different members. We also show that one of these genes corresponds to the previously described GIGAS locus and examine the role of this gene in photoperiod responsiveness and the induction of flowering. Our results suggest that the role of the FT family in induction of flowering is potentially more complex in pea than in Arabidopsis, involving transcriptional cross-regulation, multiple mobile signals, and possible functional differentiation of individual members.

RESULTS

The FT Gene Family in Legumes

In a previous survey of flowering-related genes in model legumes, we identified five FT-like genes in Medicago truncatula (FTLa-FTLe) and a single gene in pea most similar to Medicago FTLe (Hecht et al., 2005; Liew et al., 2009). Four additional pea FT genes were identified by library screening and PCR approaches, and isolation of the corresponding full-length cDNAs demonstrated that all five pea FT genes are expressed and have similar intron/exon structure to FT genes in other species (Figure 1A). For two of the genes, we were unable to easily isolate specific introns, presumably due to their large size. To obtain a broader perspective on FT family evolution within legumes, we performed BLAST searches of the soybean genome at Phytozome (www.phytozome.net). Although legume genomes share an ancient whole-genome duplication event, soybean has experienced an additional, more recent whole-genome duplication event and as a result contains larger gene families with readily identifiable pairs of homoeologs (Schmutz et al., 2010). Our searches identified 10 putative full-length FT genes in soybean (see Supplemental Table 1 online), eight other full-length PEPB genes more similar to Arabidopsis TFL1, BFT, or MFT (see Supplemental Table 1 online), and several other apparent pseudogenes.

Figure 1.

Legumes Have Three Distinct Groups of FT Genes.

(A) Genomic organization of pea FT genes. Exons are represented by shaded boxes. Bold dashed lines indicate introns of unknown size.

(B) Phylogram of legume PEBP protein sequences. Branches with bootstrap values <60% have been collapsed. The analysis is based on the sequence alignment shown in Supplemental Figure 2 online. Sequence details are available in Supplemental Table 1 online.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

Phylogenetic analysis (Figure 1B) shows that legume PEBP genes fall into previously described FT, TFL1, and MFT clades. Figure 1B also shows that the FT genes fall into three distinct subclades, and microsynteny around the soybean and Medicago genes further demonstrates the affinities of genes within each clade (see Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 2 online). These results indicate that expansion of the FT family occurred relatively early in legume evolution and suggest that the three clades are likely to be represented in other crop and model legumes. To provide consistency in nomenclature across the three species, and a framework for naming FT genes from other legumes, we designated these subclades as FTa, FTb, and FTc and propose to rename the Medicago and pea genes accordingly (see Supplemental Table 1 online).

The FTa subclade is represented in Medicago and pea by two genes, FTa1 (formerly FTLa) and FTa2 (formerly FTLb), and in soybean by four genes, a pair of homoeologs (FTa1 and FTa2) and two other linked genes (FTa3 and FTa4) without clear homoeologs. The FTb subclade is also represented by two genes in both pea and Medicago: FTb1 (formerly FTLd in Medicago) and FTb2 (formerly FTLe in Medicago and FTL in pea). In Medicago, this pair of genes is located in tandem at the top of chromosome 7, and we mapped the pea FTb1 gene to the corresponding region of linkage group V. Soybean also has four FTb genes in two homoeologous blocks on chromosomes 18 (FTb1 and FTb2) and 8 (FTb3 and FTb4) (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). The FTc subclade is the least complex, consisting of a single gene in pea and Medicago (formerly FTLc) and a single pair of homoeologs (FTc1 and FTc2) in soybean (Figure 1). In both Medicago and soybean, these genes are located immediately adjacent to FTa genes (see Supplemental Figure 1 online), supporting their orthologous nature and likely origin from the same duplication event.

Previous efforts to define structural features that distinguish flower-promoting FT-like function from flower-inhibiting TFL1-like function identified two critical pairs of residues:Tyr-85/Gln-140 in FT and His-88/Asn-144 in TFL1 (Hanzawa et al., 2005; Ahn et al., 2006). All legume FT proteins carry the conserved Tyr residue, and FTa and FTb proteins also contain the conserved Gln characteristic of other FT proteins (Ahn et al., 2006). However, FTc proteins share a His at this position and thus differ both from other FT sequences and from TFL1. FTc proteins also carry several other conserved substitutions in the adjacent region (segment B in Ahn et al., 2006) which may have the potential to alter protein function (see Supplemental Figure 2 online).

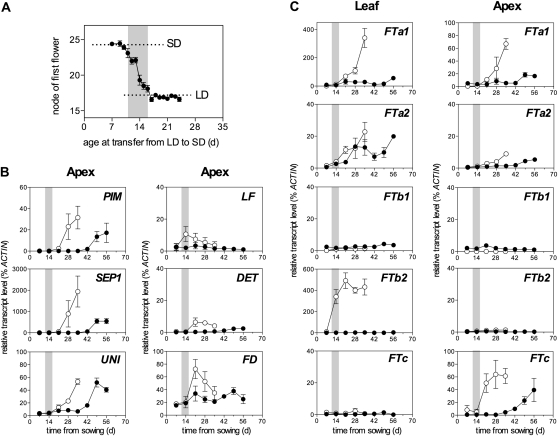

Pea FT Genes Show Distinct Patterns of Regulation

We used photoperiod transfer experiments to define a temporal window from 11 to 16 d after sowing during which pea plants of line NGB5839 become irreversibly committed to flower in long days (LD) conditions at 20°C (Figure 2A). Expression of the pea AP1 ortholog PROLIFERATING INFLORESCENCE MERISTEM (PIM) (Taylor et al., 2002) in apical buds (dissected to 2 to 3 mm in size) showed clear induction from day 21 in LD or day 42 in short days (SD), corresponding to the appearance of visible flower buds ~1 week later. Significant induction of the pea LFY ortholog UNIFOLIATA (UNI) (Hofer et al., 1997), SEPALLATA1 (SEP1) (Hecht et al., 2005), and the TFL1 paralog DETERMINATE (DET/TFL1a) (Foucher et al., 2003) also occurred from day 21 in LD or day 42 in SD (Figure 2B). Expression of the pea FD ortholog showed weak induction by day 21 in LD relative to the SD level (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Pea FT Genes Show Different Expression Patterns.

(A) Photoperiod transfer defines a window for commitment to flower in wild-type (NGB5839) plants grown in LD. Plants were grown from sowing under LD conditions and transferred to SD conditions at the times indicated. There was no significant effect of LD exposure up until day 12, and by day 17, there was no significant effect of the SD transfer. The window during which commitment to flower is established is indicated by gray shading. Values represent mean ± se for n = 6

(B) and (C) Expression of inflorescence identity genes (B) and FT genes (C) during development. Relative transcript levels were determined in dissected shoot apices or the uppermost fully expanded leaf during development in LD (16 light/8 dark; open circles) or SD (8 light/16 dark; closed circles). Gray shading represents the commitment window determined in (A). Values have been normalized to the transcript level of the ACTIN gene and represent mean ± se for n = 2 to 3 biological replicates, each consisting of pooled material from two plants.

Interestingly, FT genes showed distinct patterns of regulation with respect to photoperiod, timing, and tissue specificity. In the uppermost fully expanded leaf of LD-grown seedlings, expression of FTb2 was strongly induced by day 14, whereas induction of FTa1 and FTa2 expression occurred more gradually from days 14 to 35 (Figure 2C). In the corresponding tissue from SD-grown seedlings, FTb2 was not expressed, whereas FTa1 showed weak induction by day 21 similar to LD, and FTa2 was also induced to a similar extent as in LD but with a delay of ~1 week. FTc transcript was not detected above background in leaf tissue under LD or SD.

We also detected significant expression of FT genes in apical buds. In LD, FTa1 and FTc expression was both clearly induced and FTa2 weakly induced by day 21 in this tissue (Figure 2C). In SD, FTc showed the strongest induction, increasing gradually from day 35 to a level similar to the wild type in LD, whereas expression of FTa1 and FTa2 was more weakly induced from day 42, similar to that of PIM and other inflorescence identity genes (Figures 2B and 2C). Neither FTb1 nor FTb2 transcript was expressed above background in shoot apices under either photoperiod. The interpretation of expression in these apical bud samples must be qualified by the fact that they contained other tissues in addition to the shoot apical meristem itself, including leaf, petiole, and vascular primordia. It will be interesting in the future to examine in more detail the spatial expression patterns of FT genes at the shoot apex. Nevertheless, even with the most conservative interpretation, the specific expression of FTc in these samples and the absence of FTb2 expression does indicate a strong, contrasting tissue specificity for expression of these FT genes.

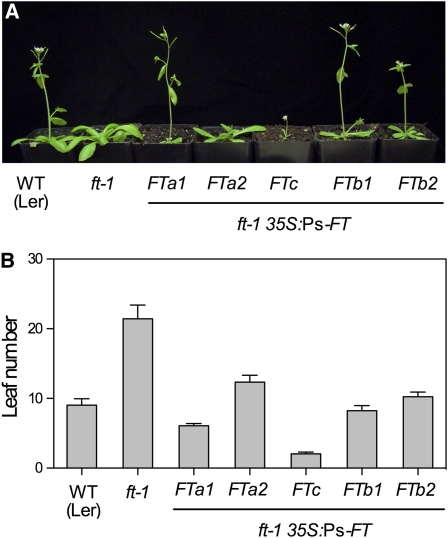

Pea FT Genes Promote Flowering in Transgenic Arabidopsis

We next tested the ability of the pea FT genes to complement the Arabidopsis ft-1 mutant. Figure 3 shows that a representative highly expressing 35S:Ps-FTa1 line grown in LD flowered significantly earlier than the untransformed ft-1 control. FTc overexpression resulted in a striking early-flowering phenotype in which the majority of transformants produced only two distorted cauline leaf–like structures before termination of the shoot apex in a single terminal flower (see Supplemental Figure 3 online). This phenotype is stronger than reported for 35S:FT expression in Arabidopsis and more similar to the combined effects of 35S:AP1 and 35S:FT (Kardailsky et al., 1999). The remaining pea genes (FTa2, FTb1, and FTb2) showed weaker activity, with transformants flowering earlier than the untransformed ft mutant but not as early as the wild type. This shows that all five pea FT-like genes possess FT function to some extent and suggests that different FT proteins may differ in their inherent activity.

Figure 3.

Pea FT Genes Show Differing Activities in Transgenic Arabidopsis.

Complementation of the Arabidopsis ft-1 mutant with pea FT genes

(A) Representative plants grown in LD. Flowering has occurred in all lines but not in the untransformed ft-1 control. WT, wild type.

(B) Total leaf number at flowering for representative Arabidopsis lines. Data are mean ± se for a minimum of 10 plants.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

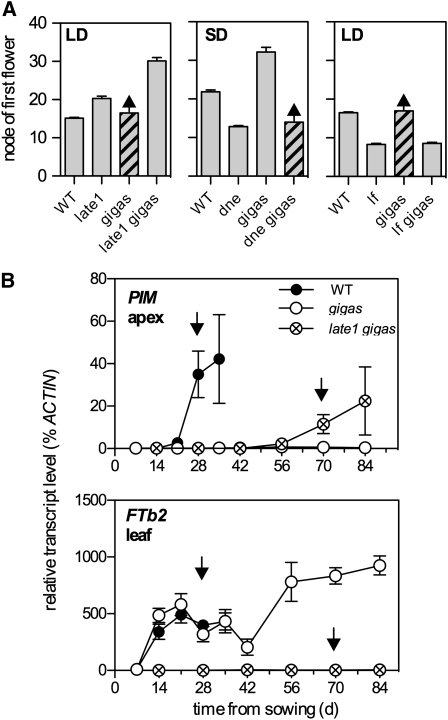

Aberrant Regulation of FT Genes in Photoperiod Pathway Mutants

We next examined whether FT genes might be misregulated in two mutants with impaired responses to photoperiod. The late1 mutant delays flowering and blocks the LD response, whereas the dne mutant promotes flowering and has a LD phenotype in SD (Hecht et al., 2007; Liew et al., 2009).

Under a 16-h LD in growth cabinets, the late1 mutation delayed flowering by approximately six nodes and the induction of PIM in dissected shoot apical buds by 2 weeks (Figure 4A). The expression patterns for the three leaf-expressed FT genes in the late1 mutant were similar to those seen in SD-grown wild-type plants (Figure 2C), consistent with the SD-like phenotype of LD-grown late1 plants (Hecht et al., 2007). Induction of FTb2 in the leaf was completely blocked by late1 (Figure 4A), consistent with a previous report showing lower expression of this gene in late1 (Hecht et al., 2007). In late1 shoot apices, the patterns of FTa1, FTa2, and FTc expression were also similar to that in SD-grown wild-type plants, with reduced FTa1 expression and delayed FTc induction relative to LD-grown wild type and no major difference in FTa2 expression (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Pea FT Genes Are Misregulated in Photoperiod Response Mutants.

(A) Gene expression in the wild type (closed circles) and the late1-2 mutant (open circles) during development under LD conditions (16 light/8 dark).

(B) Gene expression in the wild type (closed circles) and the dne-1 mutant (open circles) during development under SD conditions (8 light/16 dark).

Relative transcript levels were determined in dissected shoot apices or the uppermost fully expanded leaf. Values have been normalized to the transcript level of the ACTIN gene and represent mean ± se for n = 2 to 3 biological replicates, each consisting of pooled material from two plants.

Under an 8-h SD in growth cabinets, the dne mutation promoted flowering by approximately eight nodes and the induction of PIM by ~3 weeks (Figure 4B). The dne mutant also showed significantly higher expression of FTa1, FTa2, and FTb2 in leaves and of FTa1, FTa2, and FTc in shoot apices. The dne mutant flowers earlier in SD than the wild type in LD (Liew et al., 2009), and this was also reflected in certain FT expression patterns. Specifically, leaf expression of FTa1 and FTa2 was much stronger in SD-grown dne than in LD-grown wild type, as was expression of FTa2 in apical buds. However, FTb2 expression, although elevated in dne relative to the wild type in SD (Figure 4B), did not show the strong early induction (i.e., by day 14) that is typical of the wild type in LD (Figure 2C).

This misregulation of FT genes in leaves of late1 and dne mutants is consistent with previous findings that both mutants alter production of graft-transmissible flowering signal(s) (Hecht et al., 2007; Liew et al., 2009). However, it does not identify which among the FT genes may contribute to this signaling.

The GIGAS Locus Corresponds to FTa1

The previously described gigas mutant (gigas-1) is late flowering under SD and flowers late or not at all under LD, depending on the spectral quality of the photoperiod extension (Beveridge and Murfet, 1996). A second mutant allele (gigas-2) has a slightly more severe phenotype, failing to flower under any LD conditions (Reid et al., 1996). Whereas the SD phenotype of gigas mutants is essentially similar to the wild type, apart from a delay in flowering (Beveridge and Murfet, 1996), the LD phenotype is unusual. Despite their failure to flower, the mutants show a number of vegetative changes in response to LD, including reduced internode length, reduced leaf size, and axillary bud outgrowth (Beveridge and Murfet, 1996; Figure 5A). This phenotype is very different from that of photoperiod response mutants late1 and phyA, which essentially phenocopy SD-grown wild-type plants (Weller et al., 2004; Hecht et al., 2007), and is more similar to the phenotype of other pea mutants that impair flowering and/or inflorescence development, such as the nonflowering veg1 and veg2 mutants (Reid et al., 1996; Benlloch et al., 2007). Nevertheless, normal flowering can be restored in gigas by grafting to the wild type, implicating GIGAS in the production of a graft-transmissible flowering stimulus (Beveridge and Murfet, 1996) and suggesting FT-like genes as candidates.

Figure 5.

The GIGAS Locus Corresponds to FTa1.

(A) Representative plants of two independent gigas mutants and their original wild-type (WT) progenitor lines Virtus (VIR) and Porta (POR). Plants were grown for ~12 weeks under LD conditions (18 light/6 dark) in the glasshouse.

(B) Effect of the gigas-2 mutation on flowering node in the NGB5839 genetic background. Plants were grown under SD (8 light/16 dark) and LD (16 light/8 dark) conditions in the phytotron. Values represent mean ± se for n = 8 to 12. The nonflowering gigas LD phenotype shown in (A) is represented by diagonal hatching and an arrow. These plants are shown with a nominal value that corresponds approximately to the node at which the short-internode, highly branched phenotype commenced.

(C) Diagram of the FTa1 gene showing the nature and location of mutations in gigas mutants. Exons are shown as boxes, with coding sequence shaded in gray and untranslated regions in black. In the gigas-2 mutant, FTa1 is completely deleted.

(D) Gene expression in the wild type (closed circles) and the gigas-2 mutant (open circles) during development under LD conditions (16 light/8 dark). Relative transcript levels were determined in dissected shoot apices or the uppermost fully expanded leaf. Values have been normalized to the transcript level of the ACTIN gene and represent mean ± se for n = 2 to 3 biological replicates, each consisting of pooled material from two plants.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

The pea and Medicago genomes are closely syntenic (Aubert et al., 2006), and the location of GIGAS corresponds approximately to that of the FTa/FTc cluster in Medicago (Hecht et al., 2005). We confirmed a conserved location for these genes in pea and then examined whether any might be disrupted in gigas mutants. We found no differences within the coding regions of FTa2 and FTc in gigas-1 or gigas-2 but identified significant changes in the FTa1 gene in both mutants relative to their progenitor lines cv Virtus (gigas-1) and cv Porta (gigas-2). The gigas-1 mutant contained a single nucleotide substitution in the 3′ splice site of intron 2 (Figure 5C), predicted to result in skipping of exon 3 and an immediate termination of translation after Trp-88. PCR with FTa1 primers on gigas-1 cDNA resulted in amplification of only the expected mutant product, a cDNA molecule missing the 41 bp of exon 3, and the wild-type FTa1 cDNA could not be detected. In the case of the gigas-2 mutant, failure to amplify FTa1 from genomic DNA suggested the presence of a substantial deletion or rearrangement. A third gigas mutant (gigas-3) was identified among late-flowering mutants from an ethyl methanesulfonate–mutagenized population (Hecht et al., 2007) and found to carry a C-to-T substitution in exon 4 of FTa1 that converted Gln-127 to a stop codon (Figure 5C). FTa2 sequence was identical to the wild type in gigas-3, and as recombinants with FTc were identified during mapping, the FTc sequence was not examined in gigas-3. Transformation of the Arabidopsis ft-1 mutant with the FTa1 cDNA from gigas-1 failed to rescue the late-flowering phenotype (see Supplemental Figure 4 online), confirming that FTa1 function is significantly impaired by the gigas-1 mutation, as expected.

Molecular Consequences of gigas Mutants

We next examined how loss of FTa1 function affected the developmental regulation of genes related to inflorescence identity and the floral transition. Figure 5D shows that expression of PIM and SEP1 is completely absent in gigas, consistent with the general failure of gigas mutants to produce flowers under LD conditions. Expression of UNI was much lower than in the wild type, but a residual weak induction was still suggested. By contrast, induction of DET and FD, although relatively weak, was similar in the wild type and gigas (Figure 5D). The timing and apex-specific expression of FTc in wild-type plants under LD (Figure 2B) suggested that FTc might be a transcriptional target of other leaf-expressed FT genes, so we also examined how loss of FTa1 affected expression of FTc and other FT genes. Figure 5D shows that the weak induction of FTa2 expression in wild-type leaf tissue was completely absent in gigas, whereas the strong induction of FTb2 expression was unaffected. The gigas mutation also prevented expression of FTa2 in apical tissue, whereas FTc was induced with similar timing but to a lower level in gigas than in the wild type (Figure 5D). Thus, FTa1/GIGAS is essential for expression of inflorescence identity genes PIM and SEP1 in LD and also makes a major contribution to induction of UNI. In addition, FTa1/GIGAS is also required for the normal expression of FTa2 in the leaf and apex and FTc in the apex. This suggests that cross-regulation among FT genes may be an important feature during the induction of flowering in pea.

Genetic Interactions of gigas with Other Flowering Mutants

In view of the distinct flowering and molecular phenotypes shown by gigas and photoperiod response mutants, we next examined their genetic interactions. Surprisingly, the introduction of the late1 mutation to the gigas background restored flowering and reverted the overall phenotype to one more similar to that of late1 (see Supplemental Figure 5 online). However, the late1 gigas mutant flowered later than the late1 single mutant in LD (Figure 6A), and the difference between late1 and late1 gigas in LD was similar to the difference between the wild type and gigas in SD. This suggests that the effect of late1 is merely to confer a SD phenotype on the gigas mutant in LD. It also provides further illustration that the gigas mutant, despite not flowering in LD, retains a strong response to LD that can be blocked by the late1 mutation. Double mutants between gigas and the early-flowering photoperiod unresponsive mutant dne were readily distinguished in SD by a nonflowering phenotype very similar to the gigas single mutant grown under LD (Figure 6A). Thus, the effect of dne on gigas is the converse of late1, conferring a LD phenotype on the gigas mutant when grown in SD. Both of these interactions can be seen as being essentially additive in the sense that DNE and LATE1 exert their influence on photoperiod responsiveness independently of GIGAS. We also examined how the interaction of late1 and gigas mutations and the restoration of flowering in the gigas background by late1 might be reflected in gene expression. Figure 6B and Supplemental Figure 6 online show that the late flowering of the late1 gigas double mutant is associated with clear induction of PIM, SEP1, and UNI expression at the apex despite the lack of detectable expression of any FT gene in leaf tissue.

Figure 6.

Genetic Interactions of GIGAS.

(A) Comparison of flowering node in double mutants late1-2 gigas-2, dne-1 gigas-2, and lf-22 gigas-2 in wild-type (WT) NGB5839, and corresponding monogenic mutants. Plants were grown in the phytotron in either LD (16 light/8 dark) or SD (8 light/16 dark). As in Figure 5B, the nonflowering gigas LD phenotype is represented by diagonal hatching and an arrow. Plants displaying this phenotype are shown with a nominal value that corresponds approximately to the node at which the short-internode, highly branched phenotype commenced.

(B) Gene expression in NGB5839 (wild type), gigas-2, and the late1-2 gigas-2 double mutant during development under LD conditions (16 light/8 dark). Relative transcript levels were determined in dissected shoot apices or the uppermost fully expanded leaf. Values have been normalized to the transcript level of the ACTIN gene and represent mean ± se for n = 2 to 3 biological replicates, each consisting of pooled material from two plants. Arrows correspond to visible flower bud appearance in the dissected apices in the wild type and late1-2 gigas-2 double mutants.

Finally, we examined the genetic interaction between GIGAS/FTa1 and the LATE FLOWERING (LF) gene, a paralog of Arabidopsis TFL1 (Figure 1) that delays flowering in a photoperiod-independent manner (Murfet, 1975; Foucher et al., 2003). We found that the early-flowering phenotype of a putative null lf mutant (lf-22) was completely epistatic to the nonflowering gigas phenotype under LD, with the double lf gigas mutant indistinguishable from the single lf mutant (Figure 6A; see Supplemental Figure 5 online). This indicates that GIGAS promotes flowering through a negative influence on LF function.

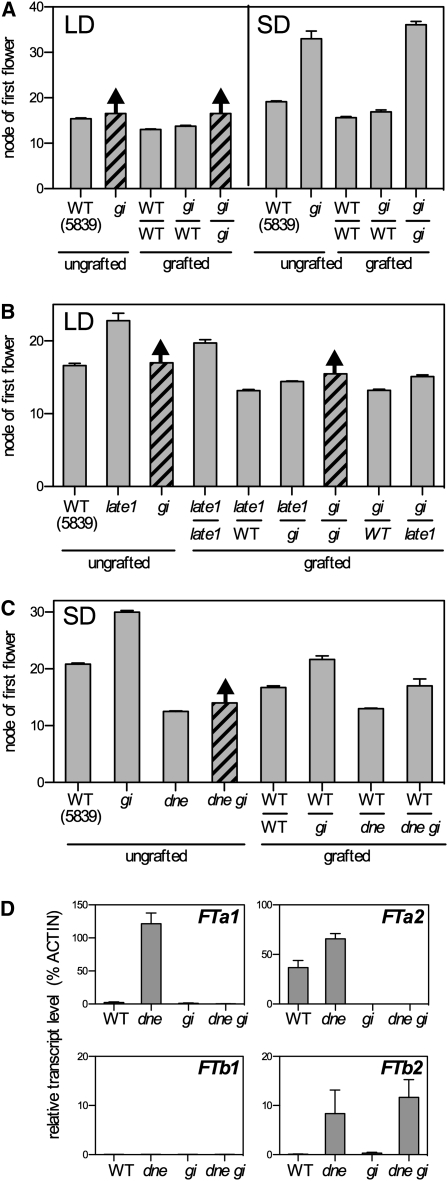

Effects of gigas on Graft-Transmissible Flowering Signals

Previous grafting experiments showed that both the late-flowering SD phenotype and the nonflowering LD phenotype of the gigas-1 mutant could be rescued by grafting to wild-type graft stocks bearing leaves (Beveridge and Murfet, 1996). Figure 7A shows that this is also true for the gigas-2 mutant and confirms that GIGAS/FTa1 is necessary for the production of a graft-transmissible stimulus of flowering. In previous experiments, the late-flowering phenotype of the late1 mutant could be similarly rescued by grafting to leafy wild-type graft stocks (Hecht et al., 2007). One possible interpretation of these results is that LATE1 acts through GIGAS/FTa1 to control the same mobile stimulus, which might either be GIGAS/FTa1 itself or some other signal downstream of FTa1. Such an interpretation would predict that gigas mutant graft stocks should be less effective than the wild type for rescue of the late1 mutant. Figure 7B shows that late1 scions grafted onto gigas stocks did flower significantly later (14.4 ± 0.1 nodes) than when grafted to wild-type stocks (13.2 ± 0.1 nodes, P < 0.01) but still flowered much earlier than late1 self-grafted plants (19.7 ± 0.5 nodes, P < 0.01). Also, late1 stocks were only slightly less effective than the wild type in promoting flowering in gigas scions (Figure 7B; 15.1 ± 0.2 versus 13.2 ± 0.1 nodes, P < 0.01), indicating that the small effect of late1 on GIGAS/FTa1 expression in leaves (Figure 4A) has only a minor effect on the mobile flowering signal. These complementary effects of late1 and gigas indicate that GIGAS/FTa1 does contribute to the flowering signal but also suggest a role for a component of the signal that is independent of GIGAS.

Figure 7.

Effects of GIGAS on Graft-Transmissible Floral Signaling.

The effects of gigas mutations on mobile floral signals were examined by grafting 6-d-old shoots excised at the epicotyl (graft scion) onto the main stem of 3-week-old plants above the uppermost fully expanded leaf (graft stock). For each graft combination, the genotypes of scion (top) and stock (bottom) are shown, separated by a horizontal line.

(A) Grafting to the wild type (WT) rescues the gigas-2 phenotype under LD and SD. Self-grafted gigas displayed a phenotype typical of ungrafted gigas control plants, whereas grafting of gigas onto the wild type restored a near- wild-type phenotype.

(B) Complementary graft-transmissible promotion of flowering by gigas-2 and late1-2 in LD. As both late1 and gigas mutants were previously observed to affect a graft transmissible stimulus, their ability to complement each other across a graft union was examined, in comparison with self-grafts and grafts of mutants onto the wild type.

(C) GIGAS-independent graft-transmissible promotion of flowering by the dne-1 mutant in SD. The importance of GIGAS/FTa1 for the graft-transmissible effect of dne was examined by comparing the ability of dne single mutant and dne gigas double mutant stocks to promote flowering of wild-type scions held in SD.

(D) Expression of FT genes in the uppermost expanded leaf of graft stocks used in (C). Values have been normalized to the transcript level of the ACTIN gene and represent mean ± se for n = 4 to 6 biological replicates.

All plants were grown in the phytotron in either LD (16 light/8 dark) or SD (8 light/16 dark). Data in (A) to (C) are mean ± se for n = 6 to 15. As in Figure 5B, the nonflowering gigas-2 LD phenotype is represented in (A) to (C) by diagonal hatching and an arrow. Plants displaying this phenotype are shown with a nominal value that corresponds approximately to the node at which the short-internode, highly branched phenotype commenced.

We tested this conclusion further by examining how gigas might affect the ability of dne mutant graft stocks to promote flowering across a graft junction under SD conditions. The dne mutant has elevated expression of FTa1, FTa2, and FTb2 in leaf tissue (Figure 4B), and we reasoned that the elimination of FTa1 activity from graft stocks by the gigas-2 mutation would show whether any of the remaining leaf-expressed FT genes could influence flowering in scions. Figure 7D confirms that 3-week-old SD-grown dne gigas seedlings lack FTa1 transcript as expected and also fail to express FTa2 or FTb1 but do express substantially higher levels of FTb2 than the wild type or the gigas single mutant. This is accompanied by an increased ability to promote flowering in wild-type scions under SD conditions (Figure 7C; 17.0 ± 1.2 versus 21.7 ± 0.6 nodes, P < 0.01), suggesting that FTb2 is associated with the production of a second mobile flowering signal that is independent of GIGAS/FTa1.

DISCUSSION

It is increasingly clear that members of the FT family play important roles in the floral transition. Compared with Arabidopsis, where the most detailed studies have been performed, FT families in many other species are considerably more complex and functional analyses are much less advanced. In this study, we characterized the FT family in three model legumes, soybean, Medicago, and pea, and identified three main branches that are likely common to all legumes. We then examined the contribution of the pea genes to control of flowering, photoperiod responsiveness, and mobile signaling.

Expression of Pea FT Genes

Compared with the simple Arabidopsis FT family, in which FT and TSF share similar expression patterns, we observed distinctly different patterns of expression for pea FT genes. In leaf tissue from plants in LD, only FTb2 was clearly induced during the period in which the plant becomes physiologically committed to flower (Figure 2). This induction is photoperiod specific and together with the apparent lack of expression in apical buds suggests that FTb2 might have a role as, or in the production of, a mobile signal for flower induction in LD. Like FTb2, FTa1 and FTa2 are also induced in leaves, but their expression is not differentially regulated by daylength over the period prior to floral commitment in LD, suggesting that they are less likely to participate in initial signaling for LD flower induction. However, in apical buds, FTa1 and FTc showed clear, LD-accelerated induction that occurred after floral commitment with similar timing to induction of inflorescence identity genes PIM, UNI, and SEP1. This raises the possibility that both of these FT genes might play a role in the apex that is intermediate between a mobile FT protein and genes specifying inflorescence identity or act in parallel with these genes as florigen targets. It is of particular interest that FTc expression is reduced in both gigas and late1 mutants (Figures 4 and 5), and the effect of late1 is at least partly independent of GIGAS (see Supplemental Figure 6 online). This provides a clear example of transcriptional cross-regulation among members of an FT gene family and further supports the possibility that FTc may integrate long-range signaling from other FT genes.

The existence of multiple, differently regulated FT family members that we observe here in pea has also been described for several other species. For example, in barley (Hordeum vulgare), two FT-like genes are preferentially expressed under LD but differ in developmental and diurnal timing, while a third gene is preferentially expressed under SD (Faure et al., 2007; Kikuchi et al., 2009). In sunflower (Helianthus annuus), one of three functional FT-like genes is specifically expressed in the shoot apex but not in leaves (Blackman et al., 2010), while in maize, multiple FT-like genes are expressed in a variety of tissues, including roots, leaves, developing inflorescences, and seeds (Danilevskaya et al., 2008). The next broad challenge will be to assess the functional relevance of these differences. Arabidopsis complementation experiments show that all five pea FT proteins have the capacity to function like Arabidopsis FT to some extent. They also suggested distinct differences in activity, but proof of this will clearly require functional analysis in the pea system.

GIGAS/FTa1 Function

Identification of both gigas-1 and gigas-2 mutants as RNA-null alleles of FTa1 enabled a first step in understanding the functions of pea FT genes. These mutants clearly show that FTa1 has an important role in control of flowering not only under LD but also under SD. Studies in rice and Arabidopsis also report minor effects of FT genes on flowering in noninductive conditions, so this is not unexpected (Yamaguchi et al., 2005; Komiya et al., 2008). However, the gigas LD phenotype, which combines a failure to flower with the retention of LD responses for other traits, differs from FT mutants in other species and shows that FTa1 does not mediate the general response to photoperiod. The greater similarity of gigas to pea inflorescence identity mutants, such as veg1 and veg2, instead indicates that the role of GIGAS/FTa1 is restricted to the induction of flowering (Reid and Murfet, 1984; Benlloch et al., 2007). It is also consistent with the observation that FTa1 expression in wild-type leaves is not induced by LD in the physiological commitment window but occurs slightly later, in parallel with induction of the inflorescence identity genes and its own induction in apical buds (Figure 2). Further support is provided by the late1 mutant, which despite a lack of photoperiod responsiveness shows only minor effects on FTa1 expression in leaves (Figure 4A; Hecht et al., 2007) during the physiological commitment window.

In addition to supporting a role for FTa1 in the acquisition of inflorescence identity and excluding a major role in photoperiod responsiveness, the comparison between late1 and gigas suggests an association between another leaf-expressed FT gene, FTb2, and the response to photoperiod. Similar to the wild-type in SD, late1 mutants in LD show delayed induction of FTa1 and FTc, and no clear effect on FTa2, but fail completely to induce FTb2 expression, while in gigas, FTb2 is induced normally (Figures 4A and 5D). Several lines of evidence thus identify FTb2 as a strong candidate for the primary FT gene controlling photoperiod response: it is not expressed in SD and is strongly upregulated during floral induction in LD, and this upregulation is blocked in a photoperiod response mutant and unaffected in gigas mutants.

In Arabidopsis and temperate cereals, FT genes also integrate signaling from vernalization pathways (Kim et al., 2009). We have not examined vernalization in this study, but a previous report showed that vernalization could induce flowering of gigas-1 in LD and was no less effective in gigas-1 than in the wild type for promotion of flowering in SD (Beveridge and Murfet, 1996). This suggests that FTa1 is not a major target for regulation by vernalization in pea and that vernalization may oppose whatever factor is responsible for the LD vegetative phenotype of gigas. However, vernalization in pea is reported to act through distinct mechanisms in leaves and at the apex (Reid and Murfet, 1975), and the leaf-based response in gigas is apparently missing (Beveridge and Murfet, 1996), suggesting that FTa1 may nevertheless mediate a component of the vernalization response. It will be interesting in the future to examine how vernalization may regulate pea FT genes and the broader molecular phenotypes of gigas and photoperiod response mutants.

Two Distinct Mobile Flowering Signals in Pea

Grafting experiments show that the lack of FTa1 in the shoot can clearly be compensated for by some factor moving from leaves or other stock tissues (Figure 7A). In view of the growing number of examples where FT-like proteins act as mobile signals (Turck et al., 2008), and the clear induction of FTa1 in leaves under LD, the most likely explanation for graft rescue of gigas mutants is the movement of the FTa1 protein itself. An alternative explanation is that the signal is some other molecule that is regulated by FTa1. For example, as expression of FTa2 in leaves is dependent on GIGAS/FTa1 (Figure 5D), it is possible that FTa2 could play this role.

As in the case of gigas, the late-flowering phenotype of the late1 mutant can also be rescued by grafting to the wild type (Hecht et al., 2007), even though gigas and late1 mutants have distinctly different phenotypes and FT expression profiles (Figures 4A and 5D). The simplest interpretation of this would be that the same FTa1-dependent signal is deficient in scions of both mutants and can be supplied by wild-type stocks, but several lines of evidence suggest that this is not the case. First, late1 mutants show only a small reduction in FTa1 expression and have similar FTa2 expression compared with the wild-type. Second, gigas scions grafted onto late1 stocks are induced to flower and flower much earlier than late1 self-grafts (Figure 7B; Hecht et al., 2007). This would not be the case if the sole reason for the late flowering of late1 and the nonflowering of gigas were a deficiency in the same mobile signal. Indeed, the fact that among the five FT genes only FTa1 and FTa2 are expressed in leaf tissue of the late1 mutant provides additional support for the idea that FTa1 is responsible for generation of a mobile signal in late1 stocks capable of rescuing the gigas mutant. Third, significant promotion of flowering occurs in late1 scions when grafted to gigas stocks under LD. The fact that gigas-2 stocks lack the FTa1 gene clearly excludes FTa1 protein as the active molecule in this case, and in view of the negligible FTa2 expression level, the participation of FTa2 protein is also unlikely. Furthermore, out of the three leaf-expressed FT genes, only FTb2 is significantly expressed in gigas, implying that if the graft rescue of late1 scions by gigas stocks reflects FT-dependent signal generation in stock leaves, then FTb2 is the only likely candidate. This conclusion is supported by results from grafts with the dne gigas double mutant under SD (Figure 7C). Like the gigas single mutant, dne gigas does not express FTa1 or FTa2 but is more effective than gigas at promoting flowering of wild-type scions and expresses much higher levels of FTb2 transcript in leaf tissue (Figure 7D). The common feature in both these two latter grafting experiments is thus an association between flower-promoting ability and the presence of significant FTb2 expression in leaves: in gigas stocks under LD and in dne gigas stocks under SD.

Overall, these results point to the coexistence of two distinct graft-transmissible flower-promoting signals in pea that are correlated with expression of FTa1 and FTb2 genes in leaf tissue. In addition, the different expression profiles of these genes during development of the wild type in LD and their association with different flowering phenotypes in the late1 and gigas mutants both suggest a hypothesis in which FTa1 and FTb2 influence the flowering process via mechanisms that are at least partially distinct. One plausible interpretation is that GIGAS/FTa1 may confer photoperiod-independent monitoring of plant size or other environmental variables and acts specifically on the induction of flowering, whereas FTb2 may act as the primary leaf-derived signal for acceleration of flowering by LD and is also responsible for other aspects of the LD response (Figure 8). Several recent studies indicate that FT genes may have roles beyond the simple initiation of flowering. For example, in tomato, where flowering is not responsive to photoperiod, FT and TFL1 homologs interact to regulate growth and determinacy across several developmental processes (Shalit et al., 2009), and in poplar (Populus spp), FT and TFL1 homologs also have a role in the induction of dormancy (Böhlenius et al., 2006; Ruonala et al., 2008; Mohamed et al., 2010). Future isolation of FTb2 mutants will clearly be an important test of this possibility in pea and will clarify other aspects of FTb2 function, including its regulatory relationship with FTa1 and FTc and its interaction with TFL1 homologs.

Figure 8.

A Model for the Role and Interactions of Pea FT Genes in Flowering and Photoperiod Responsiveness.

This model summarizes the major results from the study and the main hypotheses derived from them. Photoperiod response genes DNE and LATE1 regulate the expression of two key FT genes in leaves: FTa1 and FTb2. We propose that both genes generate distinct mobile signals that influence flowering at the apex. The mobile FTa1 signal acts specifically on flowering in both LD and SD, potentially through antagonizing the repression by LF of PIM and other inflorescence identity genes. The FTa1-dependent signal also contributes to induction of FTc and potentially to the expression of FTa1 itself at the apex. LD induce expression of FTb2 in leaves and the generation of a second, potentially FTb2-dependent, signal that influences flowering through induction of FTa1 in leaves and (directly or indirectly) at the apex. Independently of FTa1, this second signal also induces FTc at the apex, regulates a number of other photoperiod-responsive processes, and may inhibit flower induction.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

Control of Flowering without FTa1

Flowering of the gigas single mutant in SD or in the late1 gigas mutant in LD shows that in pea, the floral transition can still proceeds in the absence of significant expression of any FT gene in leaves. This implies the existence of an underlying default pathway ensuring that flowering will eventually occur regardless of daylength and suggests that the FT module may be superimposed on this to provide a means of accelerating flowering under favorable conditions. In Arabidopsis, plants lacking both FT and TSF still flower, and mechanisms are known that bypass FT to induce expression of floral meristem identity genes, including regulation of SOC1 by gibberellin (Moon et al., 2003; Jang et al., 2009). It will be interesting to examine whether a similar mechanism also operates in pea.

Grafting experiments indicate a positive role for FTa1 and FTb2 in the initiation of flowering. However, the nonflowering of the gigas mutant in LD and the fact that restoration of flowering by the late1 mutation is coupled with a loss of FTb2 expression clearly imply a more complex regulation. One possibility could be that LD conditions induce or activate some factor that inhibits flower formation in the absence of GIGAS/FTa1, and one potential candidate for this factor could be the TFL1 paralog LF (Foucher et al., 2003). In both Arabidopsis and tomato, FT and TFL1 proteins interact antagonistically to regulate floral induction, leading to the suggestion that activation of target genes depends on balance of these two gene activities (Kardailsky et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 1999; Shalit et al., 2009). In pea, loss of LF function confers extremely early flowering, and the complete epistasis of lf over gigas (Figure 6; see Supplemental Figure 5 online) is consistent with a mechanism in which GIGAS opposes LF-mediated inhibition of flowering. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that the vegetative phenotype of gigas in LD could result from a LD-specific increase in LF activity that would normally be opposed in the wild type by GIGAS/FTa1 activity. In Arabidopsis, TFL1 is transcriptionally upregulated by CO (Simon et al., 1996), and in pea, both LF and DET are expressed at a higher level in LD than in SD (Figure 2), and their expression is delayed (LF) or reduced (DET) in late1 relative to the wild type under LD (Figure 4A). However, the fact that expression of LF is lower in the nonflowering gigas mutant than in the late1 gigas double mutant (see Supplemental Figure 6 online) rules out transcriptional regulation of LF as a straightforward explanation for the LD-specific vegetative phenotype. Other explanations could include spatially localized, posttranscriptional regulation of LF activity or the action of some other factor. Detailed molecular comparisons of gigas with photoperiod response mutants may give more insight into this matter.

In conclusion, this study highlights the important role of pea FT-like genes in both regulating the timing of flowering and specifying floral identify. Our results suggest a more complex mechanism for induction of flowering in pea compared with Arabidopsis that involves cross-regulation among different FT genes with distinct patterns of expression and different inherent activities and the action of at least two mobile signals, of which one is GIGAS/FTa1. Given that expanded FT families with diverse patterns of regulation have now been reported in a range of species, it is likely that such complexity will prove to be relatively common in higher plants. Our results also pave the way for in-depth functional analyses of FT genes in other legumes and should accelerate molecular analysis of the genetic variation for flowering time and photoperiod responsiveness that exists in many crop legume species.

METHODS

Plant Material, Growth Conditions, and Grafting

The origins of the gigas-1, le-3, dne-1, and late1-2 mutants have been described previously (King and Murfet, 1985; Beveridge and Murfet, 1996; Lester et al., 1999; Hecht et al., 2007). The gigas-2 mutant was generated by W.K. Swiecicki following fast-neutron mutagenesis of cultivar Porta, and the gigas-3 mutant was generated from line NGB5839 by ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenesis (Hecht et al., 2007). Plants for all gene expression studies (Figures 2B, 2C, 4, 5D, and 6B), Arabidopsis thaliana flowering experiments (Figure 3) and photoperiod transfer experiments (Figure 2A) were conducted in growth cabinets at 20°C, whereas flowering time and grafting experiments (Figures 5A, 5B, 6A, and 7) were conducted in the Hobart phytotron using previously described growth media, light sources, phytotron conditions, and grafting protocols (Hecht et al., 2007). Standard phytotron SD conditions consisted of an 8-h photoperiod of natural light, which was extended for 8 h with white light from compact fluorescent tubes at an irradiance of 10 μmol m−2 s−1 to give a 16-h LD.

Gene Isolation and Phylogenetic Analysis

All pea (Pisum sativum) FT genes except FTc were isolated from leaf cDNA and genomic DNA of the wild type (NGB5839) using PCR techniques, rapid amplification of cDNA ends (SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit; Clontech), and genome walking (GenomeWalker Universal kit; Clontech), using specific primers designed on an initial DNA fragment obtained with degenerate primers (Hecht et al., 2005). FTc full genomic sequence was obtained by screening a commercially made pea genomic library (Clontech). All PCR fragments were cloned in pGEM-T easy (Promega) and sequenced at the Australian Genome Research Facility. Primer details are given in Supplemental Table 3 online. For the phylogenetic tree shown in Figure 1B, amino acid sequences of legume PEBP proteins were aligned using ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997). Distance and parsimony-based methods were used for phylogenetic analyses in PAUP*4.0b10 (http://paup.csit.fsu.edu/) using the alignment shown in Supplemental Figure 2 online.

Arabidopsis Complementation

The Arabidopsis ft-1 mutation in the Landsberg erecta background was previously described (Koornneef et al., 1991; Kardailsky et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 1999) Full-length cDNA fragments for pea FT genes were generated by PCR from pea wild-type line NGB5839 and additional full-length FTa1 cDNAs from the original gigas-1 mutant and its progenitor cultivar Virtus using primers listed in Supplemental Table 3 online. The cDNA fragments were were first cloned in pCR8⁄GW⁄TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and then recombined into the binary vector pB2GW7 using Gateway cloning (Karimi et al., 2002) and confirmed by sequencing. Arabidopsis transformation was conducted by floral dipping (Bechtold et al., 1993), and the flowering phenotypes of several independent transformants per construct were characterized through several generations.

Gene Expression Studies

Harvested tissue consisted of both leaflets from the uppermost fully expanded leaf or apical buds dissected to a size ~2-mm wide and 3-mm long. Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and total RNA extracted using the SV Total RNA isolation system (Promega). RNA concentrations were determined by spectrophotomoter analysis using a NanoDrop 8000 (Thermo Scientific). Reverse transcription was conducted in 20 μL with 1 μg of total RNA using MMLV high performance reverse transcriptase (Epicenter) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-negative (no enzyme) controls were performed to monitor for contamination with genomic DNA. First-strand cDNA was diluted five times, and 2 μL was used in each real-time PCR reaction. Real-time PCR reactions using SYBR green chemistry (Sensimix, Quantace, Bioline) were set up with a CAS-1200N robotic liquid handling system (Corbett Research) and run for 50 cycles in a Rotor-Gene RG3000 (Corbett Research). Two technical replicates and two to three biological replicates were performed for each sample. Transcript levels of several potential reference genes, including EF1a (Johnson et al., 2006), UBI (Platten et al., 2005), and ACTIN (Weller et al., 2009a), were examined in the different tissue series. Of these genes, ACTIN was found to be the most stably expressed, and this gene was therefore used to evaluate transcript levels of flowering genes, as previously described (Weller et al., 2009a). Primer sequences are given in Supplemental Table 3 online.

Accession Numbers

Please refer to Supplemental Table 1 online for accession numbers of pea, Medicago, and soybean FT genes. Accession numbers for other genes are as follows: DET (AY340579), LF (AY343326), PIM (AJ291298), SEP1 (AY884290), and UNI (AF010190).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Microsynteny around FT Genes in Medicago and Soybean.

Supplemental Figure 2. Alignment of Legume PEBP Amino Acid Sequences.

Supplemental Figure 3. Overexpression of PsFTc in Transgenic Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure 4. The gigas-1 Mutation Completely Impairs the Activity of Pea FTa1 in Transgenic Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure 5. Photographs of Representative Plants of late1 gigas and lf gigas Double Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 6. Gene Expression in NGB5839 (WT), gigas-2, and the late1-2 gigas-2 Double Mutant during Development under LD.

Supplemental Table 1. Details of FT-like sequences in pea, Medicago, and soybean.

Supplemental Table 2. Microsynteny in the FTa/FTc region in soybean and Medicago.

Supplemental Table 3. Primers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ian Cummings and Tracey Winterbottom for help with plant maintenance and Ian Cummings and Michael Oates for assistance with controlled environments. We also thank Daniel McCarthy for assistance with preparation of FTb1 and FTb2 constructs and with analysis of the gigas-3 mutant, Jane Campbell for technical assistance, and Jim Reid for helpful comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge the use of facilities administered by the University of Tasmania Central Science Laboratory. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (J.L.W.) and the New Zealand Foundation for Research Science and Technology (R.C.M.; Contract C10X0704).

References

- Abe M., Kobayashi Y., Yamamoto S., Daimon Y., Yamaguchi A., Ikeda Y., Ichinoki H., Notaguchi M., Goto K., Araki T. (2005). FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309: 1052–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J.H., Miller D., Winter V.J., Banfield M.J., Lee J.H., Yoo S.Y., Henz S.R., Brady R.L., Weigel D. (2006). A divergent external loop confers antagonistic activity on floral regulators FT and TFL1. EMBO J. 25: 605–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert G., Morin J., Jacquin F., Loridon K., Quillet M.C., Petit A., Rameau C., Lejeune-Hénaut I., Huguet T., Burstin J. (2006). Functional mapping in pea, as an aid to the candidate gene selection and for investigating synteny with the model legume Medicago truncatula. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 1024–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N., Ellis J., Pelletier G. (1993). In planta Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris Sci. Vie 316: 1194–1199 [Google Scholar]

- Benlloch R., Berbel A., Serrano-Mislata A., Madueño F. (2007). Floral initiation and inflorescence architecture: A comparative view. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 100: 659–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge C.A., Murfet I.C. (1996). The gigas mutant in pea is deficient in the floral stimulus. Physiol. Plant. 96: 637–645 [Google Scholar]

- Blackman B.K., Strasburg J.L., Raduski A.R., Michaels S.D., Rieseberg L.H. (2010). The role of recently derived FT paralogs in sunflower domestication. Curr. Biol. 20: 629–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhlenius H., Huang T., Charbonnel-Campaa L., Brunner A.M., Jansson S., Strauss S.H., Nilsson O. (2006). CO/FT regulatory module controls timing of flowering and seasonal growth cessation in trees. Science 312: 1040–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D., Ratcliffe O., Vincent C., Carpenter R., Coen E. (1997). Inflorescence commitment and architecture in Arabidopsis. Science 275: 80–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D., Vincent C., Carpenter R., Coen E. (1996). Pathways for inflorescence and floral induction in Antirrhinum. Development 122: 1535–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon S.B., May G.D., Jackson S.A. (2009). Three sequenced legume genomes and many crop species: Rich opportunities for translational genomics. Plant Physiol. 151: 970–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel-Goren L., Liu Y.S., Lifschitz E., Zamir D. (2003). The SELF-PRUNING gene family in tomato. Plant Mol. Biol. 52: 1215–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardon F., Damerval C. (2005). Phylogenomic analysis of the PEBP gene family in cereals. J. Mol. Evol. 61: 579–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L., Vincent C., Jang S., Fornara F., Fan Q., Searle I., Giakountis A., Farrona S., Gissot L., Turnbull C., Coupland G. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316: 1030–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilevskaya O.N., Meng X., Hou Z., Ananiev E.V., Simmons C.R. (2008). A genomic and expression compendium of the expanded PEBP gene family from maize. Plant Physiol. 146: 250–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure S., Higgins J., Turner A., Laurie D.A. (2007). The FLOWERING LOCUS T-like gene family in barley (Hordeum vulgare). Genetics 176: 599–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucher F., Morin J., Courtiade J., Cadioux S., Ellis N., Banfield M.J., Rameau C. (2003). DETERMINATE and LATE FLOWERING are two TERMINAL FLOWER1/CENTRORADIALIS homologs that control two distinct phases of flowering initiation and development in pea. Plant Cell 15: 2742–2754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y., Money T., Bradley D. (2005). A single amino acid converts a repressor to an activator of flowering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 7748–7753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht V., Foucher F., Ferrándiz C., Macknight R., Navarro C., Morin J., Vardy M.E., Ellis N., Beltrán J.P., Rameau C., Weller J.L. (2005). Conservation of Arabidopsis flowering genes in model legumes. Plant Physiol. 137: 1420–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht V., Knowles C.L., Vander Schoor J.K., Liew L.C., Jones S.E., Lambert M.J.M., Weller J.L. (2007). Pea LATE BLOOMER1 is a GIGANTEA ortholog with roles in photoperiodic flowering, deetiolation, and transcriptional regulation of circadian clock gene homologs. Plant Physiol. 144: 648–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer J., Turner L., Hellens R., Ambrose M., Matthews P., Michael A., Ellis N. (1997). UNIFOLIATA regulates leaf and flower morphogenesis in pea. Curr. Biol. 7: 581–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igasaki T., Watanabe Y., Nishiguchi M., Kotoda N. (2008). The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 family in Lombardy poplar. Plant Cell Physiol. 49: 291–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger K.E., Wigge P.A. (2007). FT protein acts as a long-range signal in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 17: 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S., Torti S., Coupland G. (2009). Genetic and spatial interactions between FT, TSF and SVP during the early stages of floral induction in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 60: 614–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson X., Brcich T., Dun E.A., Goussot M., Haurogné K., Beveridge C.A., Rameau C. (2006). Branching genes are conserved across species. Genes controlling a novel signal in pea are coregulated by other long-distance signals. Plant Physiol. 142: 1014–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardailsky I., Shukla V.K., Ahn J.H., Dagenais N., Christensen S.K., Nguyen J.T., Chory J., Harrison M.J., Weigel D. (1999). Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science 286: 1962–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Inzé D., Depicker A. (2002). GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7: 193–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi R., Kawahigashi H., Ando T., Tonooka T., Handa H. (2009). Molecular and functional characterization of PEBP genes in barley reveal the diversification of their roles in flowering. Plant Physiol. 149: 1341–1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.H., Doyle M.R., Sung S., Amasino R.M. (2009). Vernalization: Winter and the timing of flowering in plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 25: 277–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King W.M., Murfet I.C. (1985). Flowering in Pisum: A sixth locus, Dne. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 56: 835–846 [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Kaya H., Goto K., Iwabuchi M., Araki T. (1999). A pair of related genes with antagonistic roles in mediating flowering signals. Science 286: 1960–1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya R., Ikegami A., Tamaki S., Yokoi S., Shimamoto K. (2008). Hd3a and RFT1 are essential for flowering in rice. Development 135: 767–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M., Hanhart C.J., van der Veen J.H. (1991). A genetic and physiological analysis of late flowering mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Gen. Genet. 229: 57–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester D.R., Mackenzie-Hose A.K., Davies P.J., Ross J.J., Reid J.B. (1999). The influence of the null le-2 mutation on gibberellin levels in developing pea seeds. Plant Growth Regul. 27: 83–89 [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Dubcovsky J. (2008). Wheat FT protein regulates VRN1 transcription through interactions with FDL2. Plant J. 55: 543–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew L.C., Hecht V., Laurie R.E., Knowles C.L., Vander Schoor J.K., Macknight R.C., Weller J.L. (2009). DIE NEUTRALIS and LATE BLOOMER 1 contribute to regulation of the pea circadian clock. Plant Cell 21: 3198–3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifschitz E., Eviatar T., Rozman A., Shalit A., Goldshmidt A., Amsellem Z., Alvarez J.P., Eshed Y. (2006). The tomato FT ortholog triggers systemic signals that regulate growth and flowering and substitute for diverse environmental stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 6398–6403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M.K., Belanger H., Lee Y.J., Varkonyi-Gasic E., Taoka K., Miura E., Xoconostle-Cázares B., Gendler K., Jorgensen R.A., Phinney B., Lough T.J., Lucas W.J. (2007). FLOWERING LOCUS T protein may act as the long-distance florigenic signal in the cucurbits. Plant Cell 19: 1488–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu J., Warthmann N., Küttner F., Schmid M. (2007). Export of FT protein from phloem companion cells is sufficient for floral induction in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 17: 1055–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimida N., Goto K., Kobayashi Y., Araki T., Ahn J.H., Weigel D., Murata M., Motoyoshi F., Sakamoto W. (2001). Functional divergence of the TFL1-like gene family in Arabidopsis revealed by characterization of a novel homologue. Genes Cells 6: 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed R., Wang C.T., Ma C., Shevchenko O., Dye S.J., Puzey J.R., Etherington E., Sheng X., Meilan R., Strauss S.H., Brunner A.M. (2010). Populus CEN/TFL1 regulates first onset of flowering, axillary meristem identity and dormancy release in Populus. Plant J. 62: 674–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J., Suh S.S., Lee H., Choi K.R., Hong C.B., Paek N.C., Kim S.G., Lee I. (2003). The SOC1 MADS-box gene integrates vernalization and gibberellin signals for flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 35: 613–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murfet I.C. (1975). Flowering in Pisum: Multiple alleles at the lf locus. Heredity 35: 85–98 [Google Scholar]

- Platten J.D., Foo E., Foucher F., Hecht V., Reid J.B., Weller J.L. (2005). The cryptochrome gene family in pea includes two differentially expressed CRY2 genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 59: 683–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pnueli L., Carmel-Goren L., Hareven D., Gutfinger T., Alvarez J., Ganal M., Zamir D., Lifschitz E. (1998). The SELF-PRUNING gene of tomato regulates vegetative to reproductive switching of sympodial meristems and is the ortholog of CEN and TFL1. Development 125: 1979–1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid J.B., Murfet I.C. (1975). Flowering in Pisum: The sites and possible mechanisms of the vernalization response. J. Exp. Bot. 26: 860–867 [Google Scholar]

- Reid J.B., Murfet I.C. (1984). Flowering in Pisum: A fifth locus, veg. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 53: 369–382 [Google Scholar]

- Reid J.B., Murfet I.C., Singer S.R., Weller J.L., Taylor S.A. (1996). Physiological-genetics of flowering in Pisum. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 7: 455–463 [Google Scholar]

- Ruonala R., Rinne P.L., Kangasjärvi J., van der Schoot C. (2008). CENL1 expression in the rib meristem affects stem elongation and the transition to dormancy in Populus. Plant Cell 20: 59–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J., et al. (2010). Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463: 178–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalit A., Rozman A., Goldshmidt A., Alvarez J.P., Bowman J.L., Eshed Y., Lifschitz E. (2009). The flowering hormone florigen functions as a general systemic regulator of growth and termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 8392–8397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R., Igeño M.I., Coupland G. (1996). Activation of floral meristem identity genes in Arabidopsis. Nature 384: 59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki S., Matsuo S., Wong H.L., Yokoi S., Shimamoto K. (2007). Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316: 1033–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S.A., Hofer J.M., Murfet I.C., Sollinger J.D., Singer S.R., Knox M.R., Ellis T.H. (2002). PROLIFERATING INFLORESCENCE MERISTEM, a MADS-box gene that regulates floral meristem identity in pea. Plant Physiol. 129: 1150–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Gibson T.J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D.G. (1997). The ClustalX windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turck F., Fornara F., Coupland G. (2008). Regulation and identity of florigen: FLOWERING LOCUS T moves center stage. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59: 573–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller J.L., Batge S.L., Smith J.J., Kerckhoffs L.H.J., Sineshchekov V.A., Murfet I.C., Reid J.B. (2004). A dominant mutation in the pea PHYA gene confers enhanced responses to light and impairs the light-dependent degradation of phytochrome A. Plant Physiol. 135: 2186–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller J.L., Hecht V., Liew L.C., Sussmilch F.C., Wenden B., Knowles C.L., Vander Schoor J.K. (2009b). Update on the genetic control of flowering in garden pea. J. Exp. Bot. 60: 2493–2499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller J.L., Hecht V., Vander Schoor J.K., Davidson S.E., Ross J.J. (2009a). Light regulation of gibberellin biosynthesis in pea is mediated through the COP1/HY5 pathway. Plant Cell 21: 800–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller J.L., Reid J.B., Taylor S.A., Murfet I.C. (1997). The genetic control of flowering in pea. Trends Plant Sci. 2: 412–418 [Google Scholar]

- Wigge P.A., Kim M.C., Jaeger K.E., Busch W., Schmid M., Lohmann J.U., Weigel D. (2005). Integration of spatial and temporal information during floral induction in Arabidopsis. Science 309: 1056–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A., Kobayashi Y., Goto K., Abe M., Araki T. (2005). TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF) acts as a floral pathway integrator redundantly with FT. Plant Cell Physiol. 46: 1175–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S.J., Chung K.S., Jung S.H., Yoo S.Y., Lee J.S., Ahn J.H. (2010). BROTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (BFT) has TFL1-like activity and functions redundantly with TFL1 in inflorescence meristem development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 63: 241–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S.Y., Kardailsky I., Lee J.S., Weigel D., Ahn J.H. (2004). Acceleration of flowering by overexpression of MFT (MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1). Mol. Cells 17: 95–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.