Abstract

Motivation: Post-translational modifications to histones have several well known associations with regulation of gene expression. While some modifications appear concentrated narrowly, covering promoters or enhancers, others are dispersed as epigenomic domains. These domains mark contiguous regions sharing an epigenomic property, such as actively transcribed or poised genes, or heterochromatically silenced regions. While high-throughput methods like ChIP-Seq have led to a flood of high-quality data about these epigenomic domains, there remain important analysis problems that are not adequately solved by current analysis tools.

Results: We present the RSEG method for identifying epigenomic domains from ChIP-Seq data for histone modifications. In contrast with other methods emphasizing the locations of ‘peaks’ in read density profiles, our method identifies the boundaries of domains. RSEG is also able to incorporate a control sample and find genomic regions with differential histone modifications between two samples.

Availability: RSEG, including source code and documentation, is freely available at http://smithlab.cmb.usc.edu/histone/rseg/.

Contact: anrewds@usc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Post-translational modifications to histone tails, including methylation and acetylaytion, have been associated with important regulatory roles in cell differentiation and disease development (Kouzarides, 2007). The application of ChIP-Seq to histone modification study has proved very useful for understanding the genomic landscape of histone modifications (Barski et al., 2007; Mikkelsen et al., 2007). Certain histone modifications are tightly concentrated, covering a few hundred base pairs. For example, H3K4me3 is usually associated with active promoters, and occurs only at nucleosomes close to transcription start sites (TSSs). On the other hand, many histone modifications are diffuse and occupy large regions, ranging from thousands to several millions of base pairs. A well known example H3K36me3 is associated with active gene expression and often spans the whole gene body (Barski et al., 2007). Reflected in ChIP-Seq data, the signals of these histone modifications are enriched over large regions, but lack well-defined peaks. It is worth pointing out that the property of being ‘diffuse’ is matter of degrees. Besides the modification frequency, the modification profile over a region is also affected by nucleosome densities and the strength of nucleosome positioning. By visual inspection of read-density profiles, we found that H2BK5me1, H3K79me1, H3K79me2, H3K79me3, H3K9me1, H3K9me3 and H3R2me1 show similar diffuse profiles.

There are several general questions about dispersed epigenomic domains that remain unanswered. Many of these questions center around how these domains are established and maintained. One critical step in answering these questions is to accurately locate the boundaries of these domains. However, most of existing methods for ChIP-Seq data analysis were originally designed for identifying transcription factor binding sites. These focus on locating highly concentrated ‘peaks’, and are inappropriate for identifying domains of dispersed histone modification marks (Pepke et al., 2009). Moreover, the quality of ‘peak’ analysis is measured in terms of sensitivity and specificity of peak calling (accuracy), along with how narrow the peaks are (precision; often determined by the underlying platform). But for diffuse histone modifications, significant ‘peaks’ are usually lacking and often the utility of identifying domains depends on how clearly the boundaries are located.

2 METHODS

Our method for identifying epigenomic domains is based on hidden Markov model (HMM) framework including the Baum–Welch training and posterior decoding (see Rabiner, 1989 for a general description).

Single sample analysis: we first obtain the read density profile by dividing the genome into non-overlapping fixed length bins and counting the number of reads in each bin. The bin size can be determined automatically as a function of the total number of reads and the effective genome size (Supplementary Section S1.5). We model the read counts with the negative binomial distribution after correcting for the effect of genomic deadzones. We first exclude unassembled regions of a genome from our analysis. Second, when two locations in the genome have identical sequences of length greater than or equal to the read length, any read derived from one of those locations will necessarily be ambiguous and is discarded. We refer to contiguous sets of locations to which no read can map uniquely as ‘deadzones’. Those bins within large deadzones (referred to as ‘deserts’) are ignored. For those bins outside of deserts, we correct for the deadzone effect by scaling distribution parameters according to the proportion of the bin which is not within a deadzone (Supplementary Section S1.3).

We assume a bin may have one of the two states: foreground state with high histone modification frequency and background state with low histone modification frequency. We developed a two state HMM for segmentation the genome into foreground domains and background domains.

Identifying and evaluating domain boundaries: while predicted domains themselves give the locations of boundaries, we characterize the boundaries with the following metrics. We evaluate domain boundaries based on posterior probabilities of transitions between the foreground state and the background state as estimated by the HMM. For each pair of consecutive genomic bins, the posterior probability is calculated for all possible transitions between those bins. If a boundary corresponds to the beginning of a domain, the boundary score is the posterior probability of a background to foreground transition and vice versa.

Next an empirical distribution of posterior transition probabilities is constructed by computing posterior transition probabilities from a dataset of randomly permuted bins with the same HMM parameters. Those bins whose posterior transition probabilities have significant empirical P-values are kept and consecutive significant bins are joined as being one boundary. We score each boundary with the posterior probability that a single transition occurs in this boundary. The peak of a boundary is set to the start of the bin with the largest transition probability (see Supplementary Section S3 for details).

Incorporating a control sample: ChIP-Seq experiments are influenced by background noises, contamination and other possible sources of error, and researchers have begun to realize the necessity of generating experimental controls in ChIP-Seq experiments. Two common forms of control exist: a non-specific antibody such as IgG to control the immunoprecipitation, and sequencing of whole cell extract to control for contamination and other possible sources of error. With the availability of a control sample, we use a similar two-state HMM with the novel NBDiff distribution to describe the relationship between the read counts in the two samples. Analogous to the Skellam distribution (Skellam, 1946), the NBDiff distribution describes the difference of two independent negative binomial random variables (see Supplementary Section S1.2 for details).

Simultaneously segmenting two modifications: the simultaneous analysis of two histone modification marks may reveal more accurate information about the status of genomic regions. It helps to understand the functions of different histone modification marks. It is also of interest to compare samples from different cells types because histone modification patterns are dynamic and subject to change during cell differentiation. We use the NBDiff distribution to model the read count difference between the two samples, and employ three-state HMM: where the basal state means these two signals are similar, the second state represents the signal in test sample A is greater than that in the test sample B and the third state represents the opposite case (details given in Supplementary Section S2.1).

3 EVALUATION AND APPLICATIONS

We simulated H3K36me3 ChIP-Seq data and compared RSEG, SICER (Zang et al., 2009) and HPeak (Qin et al., 2010). In terms of domain identification, RSEG outperforms SICER and HPeak for single-sample analysis and yields comparable results to SICER for analysis with control samples (Supplementary Section S4.1 and 4.2). We applied RSEG to H3K36me3 ChIP-Seq dataset from (Barski et al., 2007) and found a strong association between H3K36me3 domain boundaries with TSS and transcription termination site (TTS), which supports that RSEG can find high-quality domain boundaries (Supplementary Section S4.3).

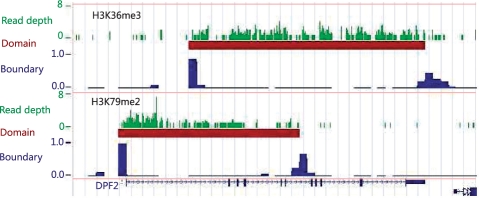

We applied RSEG to four histone modification marks (H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K36me3 and H3K79me2) from two separate studies (Barski et al., 2007; Mikkelsen et al., 2007) (Supplementary Section S5.1). In particular, we discovered an interesting relationship between the two gene-overlapping marks H3K36me3 and H3K79me2 through boundary analysis. H3K79me2 tends to associate with 5′-ends of genes, while H3K36me3 associates with 3′-ends. About 41% of gene-overlapping K79 domains cover TSS in contrast to 11% of K36 domains. On the other hand, 84% of K36 domains cover TTS in contrast to 23% of K79 domains (Table 1). In those genes with both H3K36me3 and H3K79me2 signals, H3K79me2 domains tend to precede H3K36me3 domains, for example the DPF2 gene (Fig. 1) (see Supplementary Section S5.2 for more information). This novel discovery demonstrates the usefulness of boundary analysis for dispersed histone modification marks.

Table 1.

Location of H3K36me3 and H3K79me2 domain boundaries relative to genes

| Boundaries (5′ → 3′) | K79 (%) | K36 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Upstream TSS → Inside Gene | 31 | 3 |

| Upstream TSS → Downstream TTS | 10 | 8 |

| Inside Gene → Inside Gene | 46 | 13 |

| Inside Gene → Downstream TTS | 13 | 76 |

Fig. 1.

The H3K36me3 and H3K79me2 domains and their boundaries at DPF2 (chr11:64,854,646–64,880,304).

Finally we applied our three-state HMM to simultaneously analyze H3K36me3 and H3K79me2 (Supplementary Section S5.4). The result agrees with the above observations. The application of our three-state HMM to find differentially histone modification regions is given in Supplementary Section S5.3.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Barski A, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen TS, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepke S, et al. Computation for ChIP-seq and RNA-seq studies. Nat. Meth. 2009;6:S22–S32. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z, et al. HPeak: an HMM-based algorithm for defining read-enriched regions in ChIP-Seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:369. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner L. A tutorial on hidden markov models and selected applications in speech recognition. Proc. IEEE. 1989;77:257–286. [Google Scholar]

- Skellam JG. The frequency distribution of the difference between two poisson variates belonging to different populations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A. 1946;109:296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang C, et al. A clustering approach for identification of enriched domains from histone modification Chip-Seq data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1952–1958. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.