Abstract

One of the greatest challenges in biomedicine is to define the critical targets and network interactions that are subverted to elicit growth deregulation in human cells. Understanding and developing rational treatments for cancer requires a definition of the key molecular targets and how they interact to elicit the complex growth deregulation phenotype. Viral proteins provide discerning and powerful probes to understand both how cells work and how they can be manipulated using a minimal number of components. The small DNA viruses have evolved to target inherent weaknesses in cellular protein interaction networks to hijack the cellular DNA and protein replication machinery. In the battle to escape the inevitability of senescence and programmed cell death, cancers have converged on similar mechanisms, through the acquisition and selection of somatic mutations that drive unchecked cellular replication in tumors. Understanding the dynamic mechanisms through which a minimal number of viral proteins promote host cells to undergo unscheduled and pathological replication is a powerful strategy to identify critical targets that are also disrupted in cancer. Viruses can therefore be used as tools to probe the system-wide protein-protein interactions and structures that drive growth deregulation in human cells. Ultimately this can provide a path for developing system context-dependent therapeutics. This review will describe ongoing experimental approaches using viruses to study pathways deregulated in cancer, with a particular focus on viral cellular protein-protein interactions and structures.

Keywords: Cancer, Protein interaction networks, Protein interaction domains and motifs, Therapy, Virus

A major goal of systems biology is to define the principles of operation of biological systems. An individual cell replicates or dies as a single functional unit. However, the pivotal cellular decision to undergo replication or programmed cell death is determined and coordinated by multiple signals and components that act together within integrated networks [1]. Each cell is composed of, on average, between 20,000–25,000 different genes [2], two copies of a 3.6×109 base pairs DNA genome, RNA, lipids, metabolites and chemical messengers. A daunting challenge is to define how these components are organized and subverted to elicit pathological replication. The latter is a phenotype that is at the heart of several human diseases, including cancer and viral replication.

Here we will discuss how exploiting the profound overlap that exists between the molecular targets and phenotypes elicited by DNA virus proteins and tumor mutations provides a unique opportunity to reduce the complexity of experimental systems needed to define human growth deregulation networks. We will discuss how viral protein interactions have revealed many of the key tumor targets and how this can be exploited to develop novel therapies. We will focus specifically on how systematic proteomic and structural studies with viral proteins could be used to define the critical protein interaction networks that deregulate growth and survival in human cells.

Cancer: A complex phenotype at the ‘top’ and a myriad of genetic lesions at the ‘bottom’

The growth deregulation engendered in cancer is a complex phenotype that arises when cells acquire genetic mutations that inhibit apoptosis and drive uncontrolled DNA replication [3]. The development of rational cancer treatments requires a delineation of the critical networks of interactions that are subverted to elicit growth deregulation in human cells. Towards this end, large-scale cancer genome sequencing projects are providing insights into the breadth of mutations, amplifications and deletions that accumulate within human tumors [4; 5]. A staggering 100,000 mutations have been identified in cancer genomes [6] since the first somatic cancer mutation, HRAS, was reported over a quarter of a century ago [7; 8]. Furthermore, genome sequencing efforts do not reveal epigenetic mechanisms that silence tumor suppressor gene loci [9] or the contribution of microRNAs that deregulate the expression of key genes post-transcriptionally [10]. On average, 3.93 mutations are found per Mb of DNA in human cancers, most of which are thought to be ‘passenger’ mutations that confer no growth advantage [4]. Although this might have been predicted for mutations in intergenic and intronic DNA, it applies even in protein-coding exons. The inherent genetic instability and relatively short evolutionary lifespan of tumor cells selects for mutations that drive aberrant replication, but not necessarily against those mutations that are neutral with respect to the neoplastic phenotype. There are at least 350 genes that exhibit recurrent mutations, suggesting that these are likely to be ‘driver’ mutations [6]. However, statistical evidence suggests there are likely to be many more ‘driver’ mutations that play a causal role in tumor development and maintenance, which continues to fuel genome-wide sequencing efforts [4].

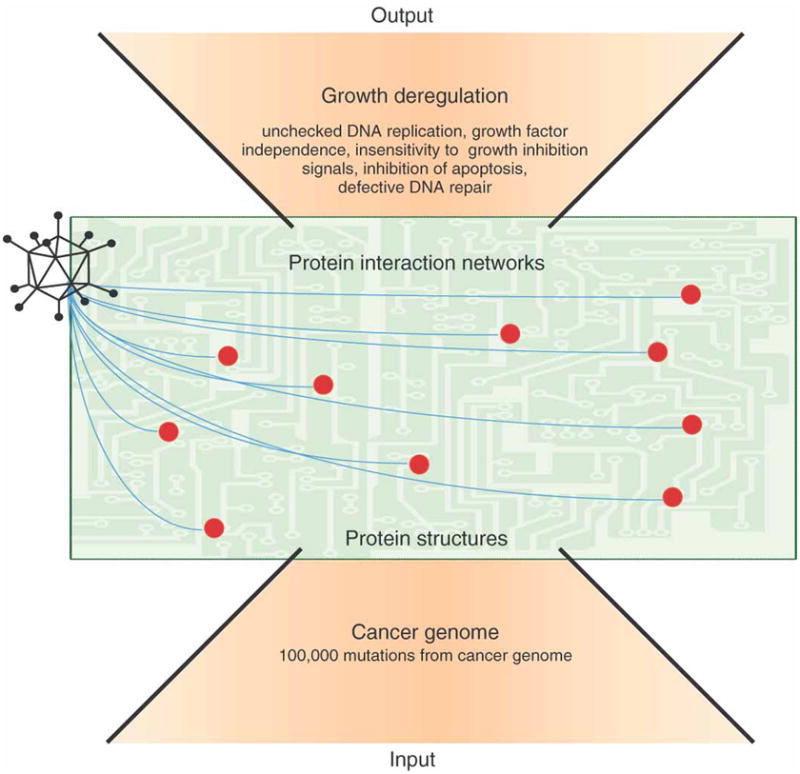

A major task ahead is to determine which of these myriad genetic aberrations play a causal role in driving tumorigenesis. However, even if a definitive catalog of mutations for individual cancers is possible, this will not contain any higher order information per se as to how these mutations perturb the cellular protein interaction networks that ultimately enact their pathological functions. In this respect, cancer genome sequencing efforts represent a ‘bottom-up’ approach for understanding the growth deregulation phenotype. On the other end of the spectrum is the ‘top-down’ approach, which tries to link a complex set of growth deregulation phenotypes back to mutations in single components (Figure 1). However, both approaches are confounded by our current lack of understanding of how cancer mutations disrupt the dynamics and functional protein interactions that regulate growth and survival. Here we will discuss how studies with DNA virus proteins can provide critical focus and novel insights in this regard.

Figure 1. Exploiting the convergence between DNA viruses and tumor mutations to define the critical protein structures and interactions that elicit the complex growth deregulation phenotype.

Cancer is a complex phenotype at the ‘top’ that is driven by the acquisition of a myriad of genome mutations at the ‘bottom’. Unfortunately, we have a poor understanding of the protein structures and interactions in higher order networks that are disrupted by gene mutations to elicit growth deregulation. There is a profound overlap between the cellular targets of small DNA virus proteins and tumor mutations. Evolution has selected for a minimal number of viral proteins that target the critical protein interaction hubs (red dots) that regulate cellular DNA replication and survival. Thus, viral proteins are powerful tools with which to define the organization and function of cellular protein networks that regulate replication and survival. It is this fertile ‘middle’ ground that provides novel and promising opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Tumor mutations and viral proteins converge in targeting critical networks of protein-protein interactions that regulate replication and survival

The fertile middle ground for both understanding and therapeutically targeting growth deregulation is linking viral and tumor genomes to the cellular protein structures and interactions that elicit their pathological functions and propagation (Figure 1). The aberrant structures, levels and activities of proteins are the functional conduits of tumor mutations’ effects and important targets for therapeutic intervention. Unfortunately, many proteins deregulated by tumor mutations are considered ‘un-druggable’, for example, transcription factors, and/or play a key role in normal cellular functions, for example, PI-3 Kinase. Therefore, identifying and targeting the specific interactions that elicit growth deregulation is an attractive alternative strategy for the development of novel cancer therapies. A ‘middle out’ approach would be to define the dynamics and nature of the protein interactions that elicit growth deregulation (Figure 1). However, this presents somewhat of ‘a chicken and the egg problem’. With 1000’s of mutations potentially affecting protein structures and interactions, where does one begin to define the key functional interactions that are disrupted and how to uncouple them selectively for cancer therapy?

An intrinsic property of viral proteins is that they select and attack critical cellular hubs and functions (Figure 2) [11]. Strikingly, when cancer molecular genetics was in its infancy, small DNA tumor virus proteins were used as simple tools to identify key cellular targets and mechanisms that were subsequently found to be deregulated by mutations in almost every form of human cancer. Studies with DNA viruses either identified or provided seminal insights into p53 [12; 13], tyrosine phosphorylation [14], Src family kinases [15], the Rb family of tumor suppressors [16], E2F [17], p300/CBP histone acetyltransferase [18; 19] and PI-3 Kinase [20]. DNA viral proteins also provided our first clues that the targets of tumor mutations must ‘cooperate’ to elicit cellular transformation [21].

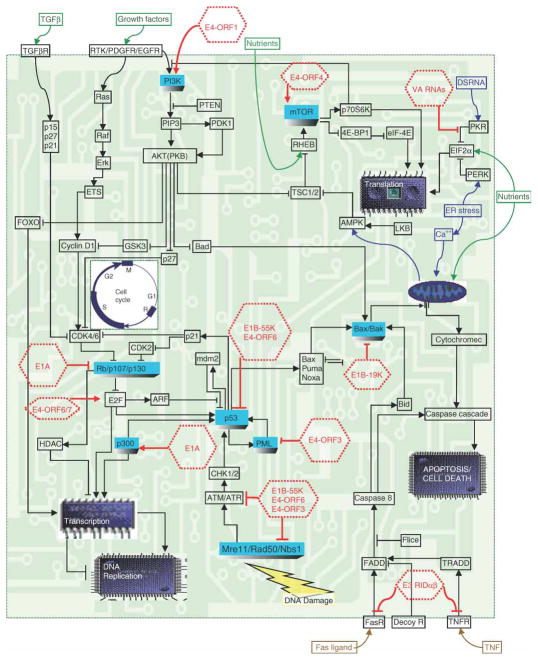

Figure 2. Adenovirus protein interactions target critical cellular hubs to elicit growth deregulation in quiescent human epithelial cells.

Adenovirus early proteins (only some of which are shown) act together as a program to target critical cellular hubs that regulate replication and survival in human cells. Many of the same cellular proteins and networks of interactions are also disrupted by tumor mutations.

The small double-stranded DNA viruses (less than 40kb) include adenoviruses, human papilloma viruses (HPV) and polyoma viruses (including SV40). Unlike the larger DNA viruses, they rely entirely on the cellular machinery for the replication of their genomes and proteins. Countless generations of propagation and selective pressure have driven the evolution of both minimal viral genomes and ‘early’ proteins (non-capsid) that drive unchecked cellular and viral DNA replication. Consequently, many of the hallmarks of growth deregulation in cancer are common to virus infected cells, including: self sufficiency in growth signals, insensitivity to growth inhibitory signals, evasion of apoptosis, unchecked DNA replication and defective DNA damage/repair pathways (Figure 1) [3; 22]. In achieving this end, viral proteins converge upon many of the same molecular targets and growth regulatory networks that are also perturbed by tumor mutations (Table 1) [23; 22].

Table 1. Cellular proteins that interact with small DNA tumor virus early proteins.

This table lists the cellular proteins that have been shown to interact with small DNA tumor virus early viral proteins (far left column) and whether they are mutated in cancer or human disease syndromes (central column). The far right columns indicate the method that was used to identify the interaction and references the study in which the interaction was first reported. GST pull-down indicates that either the cellular/viral protein was expressed as a recombinant GST fusion protein and used in pull-down studies with either mammalian cell extracts or in vitro translated proteins. Immunoprecipitation (IP) refers to a pull-down with an antibody either to viral/cellular protein antigens or against epitope tagged constructs (can indicate the use of either recombinant proteins, in vitro translated proteins or mammalian cell lysates).

| Early Viral Protein | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CellularInteracting Protein | Cancer/Syndrome | Methods | Ref |

| AdenovirusE4-ORF1 | |||

| MPDZ (MUPP1) | GST pulldown | [30] | |

| MAGI-1 | GST pulldown | [96] | |

| DLG1 (hDLG/SAP97) | IP, GST pulldown | [97] | |

| TJP2 (ZO-2) | Familial Hypercholanemia | IP, GST pulldown | [98] |

| INADL (PATJ) | IP, GST pulldown | [99] | |

| AdenovirusE4-ORF2 | |||

| None reported | |||

| AdenovirusE4-ORF3 | |||

| PML | APL, ALL | IP, GST pulldown | [100] |

| TRIM24 (Tif1α) | Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma, AML | IP, Chitin-tag pulldown | [101] |

| PRKDC (DNAPK) | IP | [102] | |

| AdenovirusE4-ORF4 | |||

| PPP2R2B (β subunit) | Spinocerebellar Ataxia 12 | IP, GST pulldown | [103] |

| SRC | Colon Cancer | IP, GST pulldown | [104] |

| CTTN (Cortactin) | IP | [105] | |

| DOK1 (p62dok) | IP | [105] | |

| ENTPD4 (Udpase) | IP | [106] | |

| SFRS1 (SF2/ASF) | Breast Cancer | GST pulldown | [107] |

| AdenovirusE4-ORF6 | |||

| TP53 (p53) | ADCC, HCC, NPC, OSRC, LFS1, Breast, Colorectal, Pancreatic Cancer, Histiocytoma, Choroid Plexus Papilloma, Thyroid Carcinoma | IP | [108] |

| PRKDC (DNAPK) | IP | [102] | |

| AdenovirusE4-ORF6/7 | |||

| E2F1 | IP, EMSA supershift | [109] | |

| TFDP1(DP-1) | EMSA supershift | [110; 111] | |

| AdenovirusE1A | |||

| RB1 (Rb/p105) | Retinoblastoma, Bladder, Breast, Small Cell Lung Cancer, OSRC | IP | [16] |

| RBL1 (p107) | IP | [112] | |

| RBL2 (p130) | IP | [113] | |

| EP300 (p300) | Colorectal, Breast, Pancreatic Cancer, ALL | IP | [19] |

| CREBBP (CBP) | Acute Leukemia, AML, Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome | IP | [19] |

| CCNA2 (p60/Cyclin A) | IP | [114] | |

| ATF1 | Malignant Melanoma of Soft Parts, Angiomatoid Fibrous Histiocytoma | IP, GST pulldown | [115] |

| ATF2 | Y2H | [116] | |

| POU5F1 (Oct-4) | EMSA supershift | [117] | |

| TBP | Huntington Disease Like 4, Parkinson Disease, SCA17 | IP, Sed-Vel | [118] |

| CDK2 (p33/CDK2) | IP | [119] | |

| CtBP1 | IP, GST pulldown | [120] | |

| MYOG (myogenin) | GST pulldown | [121] | |

| TCF3 (E12) | ALL | GST pulldown | [121] |

| YY1 | Y2H, GST pulldown | [122] | |

| RARβ | GST pulldown | [123] | |

| TFAP2A (AP2) | Branchiooculofacial Syndrome | GST pulldown | [124] |

| KAT2B (P/CAF) | GST pulldown | [125] | |

| GTF2F2 (Rap30, TFIIF) | GST pulldown | [126] | |

| TAF4 (TAFII 135) | GST pulldown | [127] | |

| MED23 (Sur2) | GST pulldown | [128] | |

| STAT1 | GST pulldown, Y2H | [129] | |

| SMAD1, 2, 3 | Colorectal, Lung Cancer | IP | [130] |

| ZMYND11 (BS69/BRAM1) | IP | [131] | |

| PSMC5 (Sug1) | IP, GST pulldown | [132] | |

| PSMC1 (S4) | IP, GST pulldown | [133] | |

| PSMC2 (S2) | IP, GST pulldown | [133] | |

| RBPJ (CBF1) | IP, GST pulldown | [134] | |

| PRKAR2A (PKARIIa) | IP, GST pulldown | [135] | |

| GNB2L1 (RACK1) | IP, GST pulldown | [136] | |

| EP400 (p400) | IP | [137] | |

| p202 (murine) | IP, GST pulldown | [138] | |

| TRRAP | IP | [139] | |

| RUNX3 | Gastric Cancer | IP, GST pulldown | [140] |

| CREB1 | Clear Cell Sarcoma, Angiomatoid Fibrous Histiocytoma | IP, GST pulldown | [115] |

| UBC9 (murine) | Y2H, IP, GST pulldown | [141] | |

| AdenovirusE1B-19K | |||

| BAX | Colorectal Cancer, T-ALL | IP, GST pulldown | [142] |

| BAK1 (BAK) | Y2H | [143] | |

| BNIP3 | Y2H | [144] | |

| BIK (Nbk) | Y2H | [145] | |

| BCLAF1 (Btf) | Y2H | [146] | |

| LMNA (Lamin A/C) | Arthropathy, CMD1A, CMT2B1, EDMD2, EDMD3, Heart-Hand Syndrome, HGPS, LDHCP, FPLD2, MADA, LGMD1B, Restrictive Dermopathy, WRN | Y2H, GST pulldown | [147] |

| AdenovirusE1B-55K | |||

| TP53 (p53) | ADCC, HCC, NPC, OSRC, LFS1, Breast, Colorectal, Pancreatic Cancer, Histiocytoma, Choroid Plexus Papilloma, Thyroid Carcinoma | IP | [148] |

| HDAC1 | IP, GST-pulldown | [149] | |

| MRE11A (Mre11) | Ataxia-Telangiectasia Like Disorder | IP | [150] |

| Rad50 | IP | [150] | |

| LIG4 (DNA Ligase IV) | LIG4 Syndrome, Multiple Myeloma, Conduct Disorder and ADHD | IP | [151] |

| HNRNPUL1 (E1B-Ap5) | IP | [152] | |

| AdenovirusE1B-55K + E4-ORF6 | |||

| CUL5 (Cullin-5) | IP | [153] | |

| TCEB2/1 (Elongin B/C) | IP | [153] | |

| Rbx1 | IP | [153] | |

| ANP32A (pp32) | IP | [153] | |

| TUBB4 (Tubulin-β4) | IP | [153] | |

| MAP7 (E-MAP-115) | IP | [153] | |

| NUMA1 | APL-NUMA/RARα type | IP | [153] |

| KPNA2 (Importin α) | IP | [153] | |

| Human Papilloma VirusE6(HPV E6) | |||

| MPDZ (MUPP1) | GST pulldown | [30] | |

| DLG1 (hDLG/SAP97) | GST pulldown, MBP | [154] | |

| pulldown, IP | |||

| MAGI-1, MAGI-2, MAGI-3 | GST pulldown | [96] | |

| UBE3A (E6-AP) | Angelman Syndrome | GST pulldown | [155] |

| TP53 (p53) | ADCC, HCC, NPC, OSRC, LFS1, Breast, Colorectal, Pancreatic Cancer, Histiocytoma, Choroid Plexus Papilloma, Thyroid Carcinoma | IP | [156] |

| RCN2 (E6BP) | GST pulldown | [157] | |

| IRF3 | Y2H, GST pulldown | [158] | |

| PXN (paxillin) | IP, GST pulldown | [159] | |

| PTPN3 | GST pulldown | [160] | |

| GPS2 | IP, GST pulldown | [161] | |

| Zyxin | Y2H, GST pulldown, IP | [162] | |

| CASP8 (Procaspase 8) | HCC, ALPS2B | IP, GST pulldown | [163] |

| CREBBP (CBP) | Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome | IP, GST pulldown | [164] |

| BAK1 (BAK) | GST pulldown | [165] | |

| FADD | M2H, GST pulldown | [166] | |

| TNFRSF1A (TNFR1) | Familial Periodic Fever | IP | [167] |

| TADA3L (ADA3) | GST pulldown | [168] | |

| TSC2 (Tuberin) | Somatic Lymphangioleio-myomatosis, Tuberous Sclerosis-2 | Y2H, GST pulldown | [169] |

| SIPA1L1 (E6TP1) | GST pulldown | [170] | |

| MCM7 | GST pulldown | [171] | |

| XRCC1 | Y2H, IP | [172] | |

| SCRIB | GST pulldown | [173] | |

| PKN1 (PKN) | IP, GST pulldown | [174] | |

| TYK2 | Protein Tyrosine Kinase 2 Deficiency | GST pulldown | [175] |

| BRCA1 | Breast, Ovarian Cancer, Papillary Serous Carcinoma of the Peritoneum | IP, GST pulldown | [176] |

| Human Papilloma Virus E7(HPV E7) | |||

| RB1 (Rb/p105) | Retinoblastoma, Bladder, Breast, Small Cell Lung Cancer, OSRC | IP | [177] |

| RBL1 (p107) | IP | [178] | |

| RBL2 (p130) | IP | [178] | |

| CDKN1A (p21) | IP, GST pulldown | [179] | |

| CDKN1B (p27) | Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia, Type IV | IP, GST pulldown | [180] |

| CCNA2 (p60/Cyclin A) | IP, GST pulldown | [181] | |

| CCNE1 (cyclin E) | Bladder Cancer | IP, GST pulldown | [182] |

| E2F6 | Tandem pulldown | [183] | |

| CHD4 (Mi2β) | Y2H, GST pulldown | [184] | |

| KAT2B (P/CAF) | Y2H, GST pulldown | [185] | |

| EP300 (p300) | Colorectal Cancer, Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome | IP, GST pulldown | [186] |

| UBR4 (p600) | IP | [187] | |

| GAA (acid α-glucosidase) | Glycogen Storage Disease II | Y2H, GST pulldown | [188] |

| PKM2 (M2 pyruvate kinase) | Y2H, GST pulldown | [189] | |

| IGFBP3 | Y2H, GST pulldown | [190] | |

| IRF9 (p48) | IP, GST pulldown | [191] | |

| SNW1 (Skip) | Y2H, GST pulldown | [192] | |

| IRF1 | Gastric, Non Small Cell Lung Cancer, Myelogenous Leukemia, Macrocytic Anemia, Myelodysplastic Syndrome | Y2H, GST pulldown | [193] |

| MYC | Burkitt Lymphoma, B-CLL | IP, GST pulldown | [194] |

| TBP | Huntington Disease Like 4, Parkinson Disease, SCA17 | IP, GST pulldown | [195] |

| PSMC1 (S4) | Y2H, GST pulldown | [196] | |

| DNAJA3 (hTID-1) | GST pulldown | [197] | |

| PPP2CA (PP2Ac) | GST pulldown | [198] | |

| PPP2R1A (PP2A/p65a) | GST pulldown | [198] | |

| BRCA1 | Breast, Ovarian Cancer, Papillary Serous Carcinoma of the Peritoneum | IP, GST pulldown | [176] |

| Simian Virus 40 Large T Antigen(SV40 LT) | |||

| RB1 (Rb/p105) | Retinoblastoma, Bladder, Breast, Small Cell Lung Cancer, OSRC | IP | [199] |

| RBL1 (p107) | IP | [200] | |

| RBL2 (p130) | IP | [201] | |

| TP53 (p53) | ADCC, HCC, NPC, OSRC, LFS1, Breast, Colorectal, Pancreatic Cancer, Histiocytoma, Choroid Plexus Papilloma, Thyroid Carcinoma | IP | [12; 13] |

| CCNA2 (p60/Cyclin A) | IP | [202] | |

| CREBBP (CBP) | IP | [19] | |

| HSPA8 (hsc70) | IP | [203] | |

| Cul7 | 3M Syndrome | IP | [204] |

| Bub1 | Colorectal Cancer | Y2H, IP | [205] |

| TEAD1 (TEF-1) | Sveinsson Choreoretinal Atrophy | GST pulldown | [206] |

| NBN (Nbs1) | Glioma, Medulloblastoma, Rhabdomyosarcoma, ALL, NBS | IP | [207] |

| FBXW7 (Fbw7) | Colorectal, Endometrial Cancer, T-ALL | IP | [208] |

| Simian Virus 40 Small T Antigen(SV40 ST) | |||

| PPP2CA (α subunit) | IP | [209] | |

| Polyomavirus Small T Antigen(PyST) | |||

| PPP2CA (PP2Ac) | IP | [209; 210] | |

| Polyomavirus Middle T Antigen(PyMT) | |||

| PPP2CA (PP2Ac) | IP | [209] | |

| SRC (pp60c-src) | IP | [211] | |

| PIK3R1 (p85) | Glioblastoma, Ovarian, ColorectalCancer | IP | [212] |

| WWTR1 (TAZ) | Y2H, IP, GST pulldown | [213] | |

| PLCG1 | IP | [214] | |

| 14-3-3 family | IP | [215] | |

| SHC1 | IP | [216] | |

| FYN | IP | [217] | |

| YES1 | IP | [218] | |

| Adenovirus E3-14.7K | |||

| RRAGA (FIP1) | Y2H, GST pulldown | [219] | |

| OPTN (FIP2) | Y2H, IP, GST pulldown | [220] | |

| IKBKG (FIP3) | Y2H, IP, GST pulldown | [42] | |

| CASP8 (FLICE) | ALPS2B, HCC | IP | [36] |

| Adenovirus E3-19K | |||

| HLA-A, HLA-B | IP | [33; 221] | |

| TAP1, TAP2 | BLS, Wegener-Like Granulomatosis | IP | [222] |

Abbreviations: ADCC: adrenocortical carcinoma. ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. ALL: acute lymphocytic leukemia. ALPS2B: autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, type IIB. AML: acute myelogenous leukemia. APL: acute promyelocytic leukemia. B-CLL: B-cell lymphocytic leukemia. BLS: Bare lymphocyte syndrome, typeI. CMD1A: cardiomyopathy, dilated 1A. CMT2B1: Charcot-Marie-Tooth-disease, axonal, type2B1. EMSA: electrophoretic mobility shift assay. EDMD2: Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy 2. EDMD3: Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy 3. FPLD2: familial partial lipodystrophy. GST: glutathione S-transferase. LFS1: Li-Fraumeni syndrome. HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma. HGPS: Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. IP: immunoprecipitation. LDHCP: lipoatrophy with diabetes, hepatic steatosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and leukomelanodermic papules. LGMD1B: limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, type1B. M2H: mammalian 2 hybrid. MADA: mandibuloacral dysplasia, type A. NBS: Nijmegen breakage syndrome. NPC: nasopharyngeal carcinoma. OSRC: osteogenic sarcoma. SCA17: spinocerebellar ataxia 17. Sed-Vel: sedimentation velocity. T-ALL: T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. WRN: Werner syndrome. Y2H: yeast 2 hybrid.

As illustrated in Table 1, there are several examples of cellular proteins that are targeted by both disparate viral proteins and tumor mutations (for review, see [22]). For example, targeting p53 and Rb appears to be a requisite event for both virus and tumor replication. Polyoma (Py) is unusual among the DNA viruses in that none of its three early region proteins (PyLT, PyMT, PyST) inactivate p53 via direct binding [24]. Instead, PyST hijacks the functions of the cellular protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) complex to prevent ARF (which is triggered by oncogenic stress) induced stabilization of p53 [25]. Strikingly, PP2A is also targeted by adenovirus E4-ORF4 and SV40 ST (small T antigen), but with very different biological consequences. SV40 ST displaces the B56γ subunit of PP2A to activate Akt [26], while E4-ORF4 binds (but does not displace) the PP2A B subunit to activate mTOR via a novel mechanism [27; 28] (Figure 2). This highlights not only the importance of PP2A but also how modulating PP2A protein interactions can elicit distinct functions in cellular replication and survival. Interestingly, mutations in PP2A subunits also occur in human tumors [29], suggesting that PP2A interactions also play a key role in cancer. Similarly, the convergence of both HPV E6 and adenovirus E4-ORF1 to target DLG1 and MAGUK family members is likely to be highly relevant [30].

The cellular targets of viral proteins are not always mutated directly in cancer (Table 1). Instead, their functions are often deregulated indirectly by tumor mutations that affect upstream or downstream interactions in which they act. For example, the pro-apoptotic genes, Bax and Bak (Figure 2), are generally not mutated directly in human cancer. However, their functions in protective cell suicide are inhibited by binding to the BCL2 oncogene that is constitutively expressed in follicular lymphoma (due to translocation of the BCL2 gene to the Ig heavy chain locus) and which is a functional cellular ortholog of adenovirus E1B-19K. Similarly, in tumor cells loss of function mutations in Rb/p16 or amplification of Cyclin D releases E2F from repressive Rb protein-protein interactions, analogous to the effects of adenovirus E1A, HPV E7 and SV40 LT (large T antigen).

Targeting critical cellular factors that drive cellular proliferation and prevent premature apoptosis is a primary mechanism utilized by small DNA tumor viruses to promote viral replication. However, the presentation of ‘foreign’ antigens derived from viral proteins or mutant tumor proteins can also trigger a protective host immune response that prevents the spread of viral replication and tumor cells. Therefore, the modulation of the host immune response is thought to play a key role in determining widespread viral [31] and tumor replication [32]. Once again, viral proteins and tumor mutations converge on many of the same key cellular targets to modulate the natural immune response. One of the best examples is adenovirus, which encodes a cohort of immune modulation proteins in the E3 region. For example, the E3-19K protein binds and retains the major histocompatibility complex class I complex in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), thereby preventing viral antigen presentation [33]. This is similar to loss of function mutations of β2-microgloulin in tumor cells [34], which allows tumor cells to escape host immune surveillance. In addition, the adenovirus E3-14.7K protein inhibits tumor necrosis factorα initiated apoptosis [35] and caspase 8 activation [36], while a complex between E3-10.4K (RIDα) and E3-14.5K (RIDβ) triggers the internalization and degradation of FAS [37] and TRAIL receptors [38], which inhibits the extrinsic cell death pathway. In cancer, somatic mutations of FAS [39] and the TRAIL receptor (DR5) [40] genes are found in squamous cell carcinoma and head/neck tumors, respectively. The NF-κB pathway also plays a key role in inflammation, and has both pro- and anti-tumorigenic effects, depending on the context [41]. Strikingly, one of the key players in the NF-κB pathway, IKKγ (Nemo), was first identified with the adenoviral E3-14.7K protein [42]. IKKγ is part of the heterotrimeric IKK complex [43] that phosphorylates and degrades IκBα, which releases NF-κB to activate the transcription of downstream effectors [44]. Also, the high affinity binding of E1A to CBP/p300 (discussed further below) inhibits the interferon response [45], as it competes with STAT-1 for binding to CBP/p300, which is necessary to activate the transcription of downstream effectors [46]. Tumor cells also acquire mutations that inactivate interferon signaling, which is the therapeutic rationale for several oncolytic viral therapies [47]. Furthermore, interferon itself is also used as a therapy for the treatment of many different cancers [48]. In summary, there is a remarkable overlap between the cellular targets of DNA virus proteins and tumor mutations and the analogous pathological phenotypes they ultimately enact.

Proteomic strategies to reveal critical interactions and novel growth regulatory targets

A systematic and contemporary survey of protein interactions targeted by viral proteins could provide a powerful filter to define key tumor mutations and the pivotal networks of interactions that elicit growth deregulation in human cells. For example, in addition to E1A and E1B-55K, adenovirus encodes additional early proteins that are critical for replication in quiescent cells [49] (Figure 2). Many of the cellular targets of these early viral proteins remain unknown, for example, E1B-21K, E4-ORF2 and E4-ORF-3/4. Furthermore, there are 52 different human adenoviruses that infect different human tissues and encode distinct early viral proteins (especially in the E3 region [50]). However, only the interactions of adenovirus subgroup C proteins (Adenovirus 5 and 2) have been studied in any detail. Here we will describe how advances in proteomics could extend earlier approaches with viral proteins to identify novel growth regulatory hubs and therapeutic targets.

Achieving high ‘signal’ to ‘noise’ ratios is essential for identifying specific versus non-specific protein-protein interactions. In this context Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) combined with Mass Spectrometry is a powerful approach to identify interacting cellular complexes. Under close-to-physiological conditions, the protein of interest is expressed in frame with dual protein-binding affinity tags (for example, protein A and calmodulin binding peptide). Sequential binding and affinity purification steps are used to isolate interacting protein complexes for subsequent identification by mass spectrometry [51; 52]. This technique was originally developed in yeast where system-wide studies have provided profound insights into the organization, topology and dynamics of protein interaction networks [53]. This technology has also been successfully applied in mammalian cells to identify cellular protein interactions [54]. However, a major limitation of this approach is the low overall yield and requirement for large quantities of cells (typically 5×108). Advances in mass spectrometry and fast flow inert resins have improved the success and systematic identification of interacting proteins. In addition, more efficient affinity tags, such as Strep-Tag II, have enabled the use of less starting material and single-step purifications [55]. The smaller size of the Strep-Tag II is also a major advantage, especially in the case of small (<20kD) viral proteins where larger tags are more likely to disrupt their functions and interactions.

The co-enrichment of non-specific interacting proteins is often a confounding problem. To distinguish between functional versus non-specific viral-cellular protein interactions, performing parallel pull-downs with TAP-tagged viral proteins that have discrete mutations which separate or ablate their effects in growth deregulation is of great utility. Cellular proteins that differentially interact with wild type versus mutant viral proteins are strong candidates for mediating their key biological effects in growth and a rational starting point for subsequent validation in mechanistic studies. In addition, where isotope labeling is possible, I-DIRT (Isotopic Differentiation of Interactions as Random or Targeted) is also a useful technique to distinguish contaminants from bona fide interactions [56].

An alternative and complementary strategy to identify both direct and potentially novel viral-cellular protein interactions is the use of proteome chips [57]. If used together with purified recombinant viral proteins (discussed below), they have the advantage in allowing the immediate identification of direct cellular interacting proteins. Disadvantages include the ability to express and purify soluble and functional viral proteins in recombinant systems. Current commercially available chips (e.g. ProtoArray from Invitrogen) comprise approximately 33–50% of the human proteome (up to 10,000 proteins), so inevitably some interactions are likely to be missed due to incomplete coverage. In addition, the human proteins are presented individually, rather than in the context of cognate cellular binding partners, limiting the identification of interactions that require multiple components. Nevertheless, proteome chips can identify direct novel cellular interacting proteins and could also be of great utility in identifying the cellular substrates of viral protein kinases and ubiquitin ligase complexes. For example, adenovirus E1B-55K and E4-ORF6 together recruit a cellular ubiquitin ligase complex to target p53 [58] and Mre11 [59] for ubiquitination. A major question is do they also ubiquitnate additional cellular proteins to elicit other pivotal functions in viral replication, such as RNA export, which is the critical therapeutic target of the E1B-55K deleted oncolytic virus, ONYX-015 (Oncorine) [60]. Examples of such applications, include the use of yeast proteome chips to identify novel substrates of 82 kinases [61] as well as ubiquitination substrates of the yeast E3 ligase, Rsp5 [62]. Similarly, a human proteome chip was used to identify cortactin as a novel substrate of Abl and Abl related kinases [63]. Viral proteins could also be arrayed on the same chip with human proteins, so viral-viral protein interactions could also be rapidly and systematically identified across different subtypes.

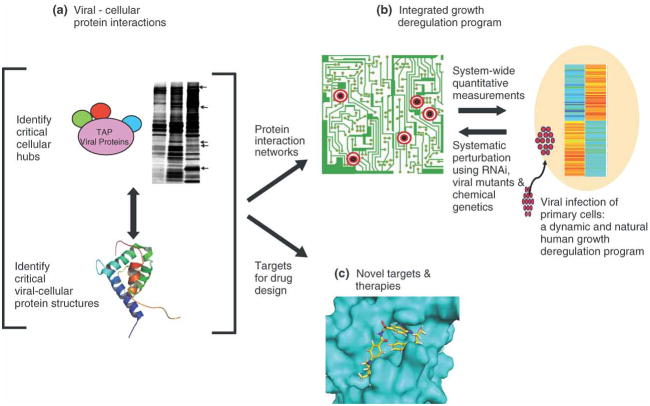

Identifying the dynamic protein interactions that elicit aberrant replication in quiescent non-transformed human epithelial cells

The majority of virus-host interactions studies have been carried out in tumor cell lines, which complement, and may thereby inadvertently mask, critical viral-cellular protein interactions and functions. Moreover, many of such studies have been in HeLa cells (cervical cells transformed by HPV) and 293 cells (human embryonic kidney cells immortalized by adenoviral E1 genes), which already express viral oncogenes that drive their deregulated growth. Although they are convenient and readily transfected cellular ‘test-tubes’, they do not reflect the natural tissue tropism and proliferative state of either the cells infected by viruses or transformed by tumor mutations. In the human body, physiological target cells of viral infection are likely to be quiescent. For example, adenovirus subgroup C viruses infect quiescent lung epithelia cells. As such, evolution has selected for viral protein interactions that function in this context. Defining the protein interaction networks disrupted by viral proteins over the time course of infection in quiescent primary cells is a natural and powerful biological system to map the network dynamics of aberrant replication (Figure 4). This also has important implications for understanding the dynamics and function of these same growth regulatory networks in cancer. For example, the adenovirus 100K protein shuts down host protein translation in the cytoplasm to facilitate capsid protein expression and hexon assembly in the nucleus at different points in the viral life cycle. This protein also plays a key role in determining the tumor selectivity of the oncolytic adenovirus, ONYX-015 [60]. A recent study that used TAP-tagged 100K constructs and mass spectrometry over the time course of viral infection demonstrated that after 24 hours, 100K binds to the arginine methyltransferase (PRMT1), which induces 100K methylation and translocation to the nucleus where it then switches to its late role in mediating viral capsid assembly [64].

Figure 4. Exploiting viruses as a powerful and simple experimental platform for an integrative systems understanding of human growth deregulation.

A) As discussed in the text, defining the interactions and structures of DNA virus proteins systematically can reveal the critical protein networks that regulate cellular growth and survival. B) This knowledge can be exploited to identify key interactions that are also targeted by tumor mutations and for the development of novel therapies. C) Furthermore, the cellular protein interaction networks disrupted by viral proteins can be integrated with quantitative measurements of the global transcriptional, translational and proteomic changes that elicit growth deregulation in the dynamics of infection in quiescent human primary cells. Using simple viral genetics, RNAi and chemical genetics, the critical proteins interactions that elicit growth deregulation can be systematically defined. Together, this provides a powerful platform to approach an integrative understanding of growth deregulation, and which could be used to predict and test rational combination therapies.

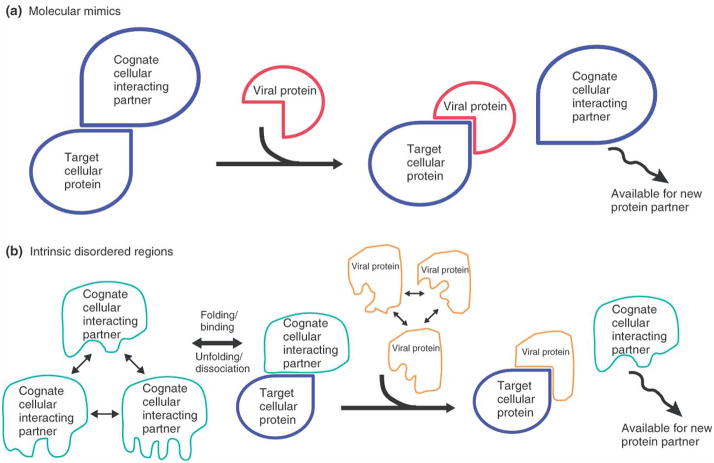

Furthermore, viral proteins have evolved to act together as a program within integrated cellular networks (Figure 2). As such, they may have emergent and context-dependent interactions in virus infection. Engineering viral genomes to express TAP-tagged proteins would be a far more ideal system than current approaches based on the ectopic overexpression of viral proteins to reveal cellular-viral protein interactions. Such a strategy would reflect the temporal timing and natural stoichiometry of viral–cellular protein interactions. In addition, the cellular networks of interactions perturbed by viral infection could be further elucidated by TAP pull-downs of key cellular growth regulatory hubs. For example, a viral protein may out-compete endogenous interactions to bind to its cellular protein target (Figure 3). As a consequence, the cognate cellular interaction partner is also released to participate in potentially alternative complexes and biological functions, which may also play a key role in driving growth deregulation (Figure 3). For example, E2F is released by the induction of Rb phosphorylation in the cell cycle, mutations of Rb/p16 in cancer, or binding to viral oncogenes (Table 1). In many cases, it is likely to be a consequence of both.

Figure 3. Viral proteins use molecular mimicry and intrinsic disordered regions to dominate and usurp cellular protein-protein interactions.

A) A smaller viral protein can dominate and out-compete endogenous cellular protein interactions by using a larger complementary interaction surface that has higher affinity. For example, SV40 LT uses a larger protein interface to out-compete DNA in binding to p53. B) Cellular proteins with intrinsic disordered regions exhibit a rapid equilibrium between different conformational states (through folding and unfolding), but adopt a single conformation upon binding to a cognate interaction partner. This allows cellular ‘hub’ proteins to use the same region to interact with multiple and often disparate partners. Such interactions are characterized as having high specificity but low affinity. Viral proteins also use intrinsic disordered regions to interact with different cellular proteins. However, by using a larger disordered region and complementary interaction surface they can bind to target proteins with a higher affinity than endogenous interactions. One example of this is adenovirus E1A, which outcompetes p53 and other cellular proteins to interact with CBP, as discussed in the main text. Both modes of binding can result in the displacement of cognate cellular interacting proteins, which are then available to participate in alternate protein complexes. This also has important consequences in considering how protein interaction complexes targeted by viral proteins and tumor mutations affect system-wide protein interaction networks to elicit growth deregulation.

Short sequence motifs only partly explain how viral proteins reprogram and usurp cellular protein interaction networks

A complete description of a biological system relies on more than just cataloging the contact points within networks. In addition to defining temporal and context-dependent interactions, 3D structural information is critical for understanding the details of binding between interacting components. Many of the small DNA tumor virus proteins are not homologous to cellular proteins at a primary sequence level, and as such, their functions would not be predicted to mimic cellular protein-protein interactions directly. Exceptions include short sequence motifs that have been identified in different viral proteins that bind the same cellular target. These motifs are presented in the context of unrelated protein scaffolds, and appear to be the result of evolutionary convergence. For example, adenovirus E1A, SV40 LT, and HPV E7 [65] all use an LXCXE (X is any amino acid) motif to interact with Rb, p107 and p130. Other viral protein sequence motifs have also been identified that target cellular factors such as the thyroid hormone receptor, p300, BS69 and CtBP [66].

However, the discovery of short sequence motifs only partly explains how viral proteins usurp endogenous protein interactions. Affinity measurements demonstrate that the LXCXE motif in HPV16 E7 binds to Rb with an affinity of 110 nM [67]. However, the full length E7 protein binds to Rb with a 20 fold higher affinity than the LXCXE motif alone [68], suggesting there is another region in E7 that contributes to enhanced affinity. The high risk strains of HPV (16 and 18) are the major etiological factor in the development of anogenital cancer [69] and express E7 proteins with a higher affinity for Rb [70]. As such, a structural understanding of E7 interactions could have enormous promise for the development of highly selective and potent small molecule therapies that inhibit E7-Rb binding for the treatment of HPV associated cervical cancer.

In this regard, the most evolutionary stable property of a protein is not its primary amino acid sequence but the collection of surface features that determine its function and interactions in cellular networks. Despite their relatively small size, viral proteins often interact with many disparate cellular proteins (Table 1) and disrupt large endogenous protein-protein interaction complexes. Thus, a key question is what are the structures and motifs used by small viral proteins to achieve this end? Could the structural basis for their interactions reveal a principle of design as to how cellular growth regulatory networks are organized and potentially manipulated for therapy? As we will discuss below, the structures of viral-cellular protein complexes can reveal novel interaction surfaces in cellular proteins as well as a rationale for how high affinity small molecule therapies could be developed based on such principles.

Structural approaches to define viral protein structures and interactions

Unfortunately, although many interactions between host proteins and early viral proteins have been identified (Table 1), the structural details of these interactions remain largely unknown. A survey of available protein structures for the small DNA tumor virus proteins in the Protein Data Bank yields few structures of early viral proteins, either alone, or in complexes with their known cellular interaction partners (Table 2). Given the central importance of DNA tumor viruses in identifying key growth regulatory targets, the lack of structural information is remarkable. Many of these viral proteins are small (<20kD) and in principle could be solved by NMR. Thus, a major question is why, despite concerted efforts, there is such a paucity of structural information?

Table 2. Structures of small DNA tumor virus proteins (non-capsid) in isolation or in complex with an interaction partner.

Available structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) of small DNA tumor virus proteins (non-capsid) either in isolation or in complex with an interaction partner (DNA or protein). The viral and cellular protein domains used for structural studies together with their corresponding amino acids are indicated.

| Virus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Viral Protein Domain | Amino Acids | Interaction Partner | Interaction Domain | Amino Acids | PDB ID |

| Adenovirus 5 | ||||||

| E2A | DNA-binding | 176–529 | 1ADT,1ADU, 1ADV, 1ANV | |||

| E1A | CR1 | 53–91 | EP300 (p300) | TAZ2 | 1763–1854 | 2KJE |

| E1A | CR1 | 40–49 | RB1 (Rb/p105) | 380–724 | 2R7G | |

| Simian Virus 40 | ||||||

| LT | Origin-binding | 131–260 | 1TBD,2TBD, 2FUF,2IPR, 2IF9, 2ITJ | |||

| LT | Origin-binding | 131–259 | RPA2 (RPA32) | 172–270 | 1Z1D | |

| LT | Origin-binding | 131–258 | SV40 DNA-21bp | 2NTC, 2ITL | ||

| LT | Origin-binding | 133–249 | SV40 DNA-18bp | 2NL8 | ||

| LT | NLS | 112–133 | Kpna2 (Importin-α) | ARM | 70–497 | 1Q1S,1Q1T |

| LT | NLS | 127–132 | SRP1 (Karyopherin-α) | ARM | 89–510 | 1BK6 |

| LT | DNAJ | 7–117 | RB1 (Rb/p105) | 379–772 | 1GH6 | |

| LT | Helicase | 266–627 | 1N25, 1SVO, 1SVL, 1SVM | |||

| LT | Helicase | 266–627 | TP53 (p53) | 92–289 | 2H1L | |

| ST | ST | 91–170 | PPP2R1A (PP2A) | 10–588 | 2PKG | |

| ST | ST | 1–174 | Ppp2r1a (PP2A) | 13–587 | 2PF4 | |

| Human Papillomavirus1 | ||||||

| E1 | DNA-binding | 159–303 | 1F08 | |||

| E7 | CR3 | 44–93 | 2B9D | |||

| Human Papillomavirus 11 | ||||||

| E2 | Transactivation | 3–195 | 1R6K, 1R6N | |||

| Human Papillomavirus 6a | ||||||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 282–368 | 1R8H, 2AYE | |||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 282–368 | DNA-16bp(viral) | 2AYB | ||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 282–368 | DNA-18bp(viral) | 2AYG | ||

| Human Papillomavirus 16 | ||||||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 286–365 | 1R8P | |||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 285–365 | 1BY9, 2Q79 | |||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 286–365 | 1ZZF | |||

| E2 | Transactivation | 1–201 | 1DTO | |||

| E2 | Transactivation | 1–200 | BRD4 | 1343–1362 | 2NNU | |

| E6 | Zn-binding | 88–151 | 2FK4 | |||

| E7 | CR1 | 21–29 | RB1 (Rb/p105) | 380–785 | 1GUX | |

| Human Papillomavirus 18 | ||||||

| E1 | Helicase | 428–629 | E2 | Transactivation | 1–193 | 1TUE |

| E2 | DNA-binding | 287–365 | 1F9F | |||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 287–365 | DNA-16bp(viral) | 1JJ4 | ||

| E2 | Transactivation | 70–213 | 1QQH | |||

| E6 | C-terminus | 152–158 | Magi-1 | PDZ-1 | 463–546 | 2I04 |

| E6 | C-terminus | 152–158 | Dlg1 (SAP97) | PDZ-3 | 459–543 | 2I0I |

| E6 | C-terminus | 152–158 | Dlg1 (SAP97) | PDZ-2 | 318–401 | 2I0L |

| E6 | C-terminus | 153–158 | DLG1 (hDlg/SAP97) | PDZ-2 | 318–405 | 2OQS |

| Human Papillomavirus 31 | ||||||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 291–372 | 1A7G, 1DHM | |||

| Human Papillomavirus 45 | ||||||

| E7 | CR3 | 55–107 | 2EWL, 2F8B | |||

| Bovine Papillomavirus 1 | ||||||

| E1 | Helicase | 308–577 | ssDNA-13bp | 2GXA | ||

| E1 | Helicase | 301–579 | 2V9P | |||

| E1 | DNA-binding | 210–354 | 1R9W | |||

| E1 | DNA-binding | 159–303 | DNA-21bp(viral) | 1KSY, 1KSX | ||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 311–410 | 1DBD | |||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 326–410 | 1JJH | |||

| E2 | DNA-binding | 326–410 | DNA-17bp(viral) | 2BOP | ||

| E2 | Transactivation | 3–199 | 2JEU, 2JEX | |||

Abbreviations: ARM: armadillo/beta-catenin-like repeats. CR: conserved region. LT: Large T antigen. NLS: nuclear localization signal. ORF: open reading frame. PDB: protein data bank, www.rcsb.org. ssDNA: single strand DNA. ST: Small T antigen.

In achieving such diverse functions and interactions, DNA virus proteins may fluctuate between multiple forms (Figure 3) making it particularly difficult to purify a homogenous protein population necessary for structural characterization. Furthermore, unfolded and disordered regions in viral proteins can also result in their poor expression as well as protein aggregation and instability [71]. However, recent technological advances in protein expression and instrumentation encourage renewed efforts to tackle these challenging structures. In cases where viral protein solubility or stability is limiting, producing 1 mg of purified protein for crystallization trials is prohibitive. However, advances in protein crystallization have dramatically reduced the amount of protein needed, such that less than 10 μL of concentrated proteins (~ 10 mg/mL) is sufficient to conduct a full crystallization screen using high throughput robots that dispense small volumes [72] and/or microfluidic chips [73]. The crystallization of proteins in μg scale also makes cell-free protein expression in wheat germ extracts a viable alternative to bacterial-based production [74].

In the cellular context, viral proteins are likely to be associated with at least one cellular binding partner and may undergo order-disorder transitions between bound and unbound states. Thus, an obvious strategy for structurally characterizing a viral protein is to co-express it with its cellular interacting partner. This can limit the exposure of hydrophobic interaction surfaces in viral proteins that may potentiate their non-specific association and aggregation when expressed alone [75]. Towards this end, recent advances have made possible the co-expression of multi-component protein complexes in several recombinant systems [76]. Once cellular binding partners have been identified for viral proteins, their respective minimal interacting regions can be identified and co-expressed for structural characterization. In this regard, protein complementation assays can make screening for the minimal protein interaction domains facile and amenable to high-throughput approaches [77].

Emerging ideas as to how small viral protein structures hijack cellular protein-protein interactions

Based on biophysical studies and a limited number of structures of viral-cellular protein complexes, two general ideas of how viral proteins usurp endogenous protein-protein interactions emerge: dominant molecular mimics and intrinsic disordered regions.

Molecular Mimics

The simplest strategy employed by viral proteins to target cellular proteins is to mimic their natural cognate interactions. Such a strategy demands that viral proteins out-compete endogenous cellular protein interactions through either higher affinity binding and/or expression levels. For example SV40 ST targets the heterotrimeric PP2A complex to activate Akt [26]. Structural studies reveal that ST binding to the A scaffolding subunit of PP2A directly overlaps and competes with endogenous B56γ regulatory subunit binding, potentially inhibiting and/or re-directing PP2A activity [78].

A particularly intriguing example of molecular mimicry is illustrated by the complex structure between the helicase domain of SV40 LT and the DNA binding domain (DBD) of p53 [79]. p53 is a critical tumor suppressor that was first discovered as a cellular interacting protein with LT [12; 13]. The tumor suppressor effects of p53 are exerted through binding to sequence specific target sites (p53 response element) in the promoters of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis genes, whereupon it recruits cofactors to activate gene transcription [80]. p53 tumor mutations are almost invariably in the DBD of p53, preventing DNA binding to target promoters. Remarkably, the LT helicase domain acts as a ‘DNA mimic’ that interacts with the DNA binding surface of p53, and more importantly, with a higher affinity than DNA. LT induces a conformational change in the L3 loop of the p53 DBD, thereby increasing the buried surface area to 1661 Å2, which is three times greater than the buried surface area between DNA (p53 response element) and the p53 DBD [79]. Unlike DNA, which has a limited contact area and a constrained geometry for protein interactions, LT utilizes a greater interaction surface (comprising 23 amino acids) that interacts intimately with 19 residues of p53 [79]. Interestingly, the cellular p53 interacting protein, 53BP1, also binds to the p53 DBD on the same interface but does not induce a rearrangement of the L3 loop [81]. It is intriguing to speculate that although 53BP1 does not induce a rearrangement of the L3 loop itself, such a conformation may be achieved in the context of additional cellular p53 protein-protein interactions or p53 post-translational modifications. If this is the case, the LT-p53 interaction may represent a natural high affinity p53-DNA binding interaction. The ability to induce such a conformation using small molecules is an attractive strategy for the development of novel therapies that ‘re-activate’ wild type p53 in tumor cells, as has been proposed for Prima-1 [82; 83].

The ability of a protein surface on LT to outcompete DNA for binding to a cellular transcription factor also provides a powerful precedent for the development of novel therapies that prevent sequence specific DNA binding of oncogenic transcription factors. For example, MYC is a pleiotropic basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor that is deregulated and overexpressed in most cancer cells. A recent study indicated the therapeutic potential for targeting MYC in cancer [84]. Although therapies that prevent protein-DNA binding interactions have long been elusive, LT provides some interesting clues as to how small molecules based on protein scaffolds could potentially mimic and disrupt sequence specific DNA binding. These principles and interactions could inform the design and tertiary structural screening of small molecule inhibitors that bind or antagonize cellular protein-protein interactions.

Intrinsic disordered regions

Bioinformatic analyses of cellular proteins that have multiple interactions (hubs) indicate the use of intrinsic disordered regions that facilitates protein binding to disparate partners [85]. An intrinsic disordered region exhibits a rapid equilibrium between different conformational states (through folding and unfolding), but adopts a single conformation upon binding to a cognate partner. One extreme example of this is the high mobility group protein A (HMGA) [86], a DNA binding protein that appears completely unstructured as measured by NMR and circular dichroism (CD), but binds to distinct DNA sequences and 18 different proteins. The use of a disordered region permits conformational samplings and the potential to use the same region to interact with multiple proteins (Figure 3). Inherent in this is a certain degree of promiscuity. However, upon binding to an interacting protein, such a region can achieve high specificity by folding into a structured element that complements the cognate partner’s binding interface, while still maintaining a low affinity interaction due to the entropic cost of folding [87].

Viral proteins can interact with many cellular proteins (Table 1) and in this sense are themselves novel hubs. Thus, it is possible that viral proteins use a similar but optimized binding strategy to replace or usurp existing cellular hub protein interactions [66] (Figure 3). One striking example of a viral protein that uses an intrinsic disordered region for binding is the conserved region 1 (CR1) domain of adenovirus E1A bound to the TAZ2 (transcriptional adaptor zinc finger-2) domain of CBP [88]. CBP is a multi-domain protein that has histone acetyltransferase activity and a co-activator for many cellular transcription factors, including p53 [89; 90]. The FX(E/D)XXXL [91] motif in the E1A CR1 region was thought to be the critical determinant for TAZ2-CBP interaction. NMR analysis demonstrates that the CR1 region of E1A (53–91) is disordered, but upon binding to TAZ2, forms two helices that fit into two binding grooves on TAZ2. Surprisingly, the FX(E/D)XXXL motif is in the loop that connects these two helices, and only the first and third amino acid residues interact with the surface of TAZ2. Indeed the NMR structure shows that it is the flanking residues of the FX(E/D)XXXL motif that contribute most of the interactions between E1A CR1 and TAZ2, which was overlooked in the initial studies that identified this motif using deletion and mutagenesis analyses [91]. Moreover, the NMR structure with E1A reveals a new surface on TAZ2 (the first binding groove) that mediates protein-protein interactions.

p53 also has a disordered region in its transactivation domain (residues 13–61) that interacts with CBP [88]. NMR studies reveal that p53 binds to the TAZ2 domain of CBP in an area that overlaps the loop and second helix of the E1A CR1 interaction. Relative to E1A CR1, the reduced interaction area between p53 and TAZ2 contributes to a lower binding affinity, such that E1A out-competes p53 binding to TAZ2 in a competitive titration assay. This shows that the CR1 of E1A can compensate for the entropic cost of folding by having a more complementary interface to interact with TAZ2 than p53, thereby resulting in higher affinity binding. In addition, another CR1 region (residues 1–25) in E1A has also been reported to interact with TAZ2 [92], which may cooperate with residues 53–91 to mediate high affinity binding to TAZ2. The use of two or more distinct regions for binding to cellular targets may further increase the affinity and specificity of viral-cellular protein interactions. The CR1 region of E1A and its interaction with CBP can drive cellular transformation by directing CBP and histone acetyltransferase activity to the promoters of genes that induce cell growth and division, resulting in their transcriptional activation. The high affinity binding and sequestration of CBP by E1A activates the promoters of genes that drive DNA replication but also results in the global hypoacetylation of Histone 3 at lysine 18, thereby preventing the transcriptional activation of genes that function in anti-viral responses and differentiation [93].

Protein interactions and structures that dictate the design and function of growth regulatory networks

A major goal of systems biology is to define the principles of operation of biological systems based on the interactions between components. Viral proteins provide discerning and powerful probes to understand not only how cells work but also how they can be manipulated using a minimal number of components. A key question then is how do viral proteins, that are relatively few in number and small in size, dominate and usurp the functional and coordinated interactions of 20,000–25,000 cellular proteins to drive aberrant replication? What is the weakness and underlying flaw in the design of cellular protein interactions networks that selects for both viral proteins and tumor mutations that elicit systems-wide growth deregulation?

It is intriguing to speculate that the very ‘weakness’ in cellular protein interactions targeted by viral proteins and tumor oncogenes is also their strength, and an absolute prerequisite for regulating their functions in cellular replication. Many cellular hub proteins do not have a higher density of residues associated with protein binding but have rapid turnover rates and often a large number of phosphorylation and lysine modification sites [94]. By linking key cellular protein-protein interactions to post-translational modifications and degradation, the cell ensures not only highly regulated binding but also high turnover dynamic interactions. In this regard, high affinity interactions, such as the viral-cellular protein interactions discussed above, would be selected against as more stable interactions would favor persistent signals that drive pathological replication. We suggest that one of the design consequences of selecting for potentially weaker and/or transient interactions at growth regulatory hubs also makes them ideal targets for viral proteins and oncogenic mutations that lock them into more stable complexes and a permanently ‘on’ state.

The use of intrinsically disordered regions by viral proteins can also provide the necessary conformational plasticity to bind to multiple partners and thus serve as hubs in protein–protein interaction networks. In general, there are more polar residues and fewer hydrophobic residues in intrinsically disordered region of cellular proteins than the folded region of globular proteins [95]. In cellular proteins if such charge is imparted by phosphorylation of serine or threonine residues, it provides a regulated and highly dynamic means of changing the equilibrium of protein folding and interactions. In contrast, viral protein sequences and structural interactions may have evolved to be independent of such regulation but still bind to the same cellular protein interaction surface.

Conclusion

Integrative systems approaches for understanding cancer are at the same impasse that molecular genetics faced over thirty years ago. We desperately need a simple but incisive model to help us identify the networks and higher order systems that drive the growth deregulation program in human cells. Just as viral protein interactions and structures can identify the key growth regulatory hubs and networks, viral infection of normal human cells can be used as a system to define the overall program (Figure 4), as well as novel therapeutic targets and drugs. The consequences of perturbing human protein interaction networks could be integrated with quantitative and system-wide measurements of the global transcriptional, translational and proteomic changes that drive growth deregulation in the dynamics of infection in quiescent primary human epithelial cells of diverse tissue origins. Furthermore, studies with viral mutants and RNAi/overexpression of cellular proteins could be used to understand the functional consequences of perturbing integrated protein interaction networks. A precise knowledge of the overlapping cellular networks targeted by viral proteins and tumor mutations could also allow the rational design of mutant viruses that undergo selective lytic replication in tumor cells.

As we have discussed here, elucidating the interactions of small DNA virus proteins can reveal the critical protein structures and networks of interactions that regulate cellular growth and survival (Figure 1 and 2). Evolution has selected for small viral proteins that have found optimized solutions for high affinity protein interactions. Revealing the structural details of their interactions can uncover molecular surfaces in cellular proteins that are also targeted by tumor mutations and could be attractive targets for the development of novel therapies. To these ends, the time is ripe for systematic structural and proteomics studies with DNA virus proteins to define the dynamic cellular networks that elicit pathological replication in human cells.

Contributor Information

Horng D. Ou, Email: hou@salk.edu, Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Studies 10010 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037

Andrew P. May, Email: Andy.may@fluidigm.com, Fluidigm Corporation 7000 Shoreline Court, Suite 100, South San Francisco, CA 94080

Clodagh C. O’Shea, Email: oshea@salk.edu, Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, 10010 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037

References

- 1.Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2004;431:931–945. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, Edkins S, O’Meara S, Vastrik I, Schmidt EE, Avis T, Barthorpe S, Bhamra G, Buck G, Choudhury B, Clements J, Cole J, Dicks E, Forbes S, Gray K, Halliday K, Harrison R, Hills K, Hinton J, Jenkinson A, Jones D, Menzies A, Mironenko T, Perry J, Raine K, Richardson D, Shepherd R, Small A, Tofts C, Varian J, Webb T, West S, Widaa S, Yates A, Cahill DP, Louis DN, Goldstraw P, Nicholson AG, Brasseur F, Looijenga L, Weber BL, Chiew YE, DeFazio A, Greaves MF, Green AR, Campbell P, Birney E, Easton DF, Chenevix-Trench G, Tan MH, Khoo SK, Teh BT, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Wooster R, Futreal PA, Stratton MR. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, Wooster R, Rahman N, Stratton MR. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stratton MR, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nature07943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos E, Tronick SR, Aaronson SA, Pulciani S, Barbacid M. T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene is an activated form of the normal human homologue of BALB- and Harvey-MSV transforming genes. Nature. 1982;298:343–347. doi: 10.1038/298343a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parada LF, Tabin CJ, Shih C, Weinberg RA. Human EJ bladder carcinoma oncogene is homologue of Harvey sarcoma virus ras gene. Nature. 1982;297:474–478. doi: 10.1038/297474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert R, Jeong H, Barabasi AL. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature. 2000;406:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane DP, Crawford LV. T antigen is bound to a host protein in SV40-transformed cells. Nature. 1979;278:261–263. doi: 10.1038/278261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linzer DI, Levine AJ. Characterization of a 54K dalton cellular SV40 tumor antigen present in SV40-transformed cells and uninfected embryonal carcinoma cells. Cell. 1979;17:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckhart W, Hutchinson MA, Hunter T. An activity phosphorylating tyrosine in polyoma T antigen immunoprecipitates. Cell. 1979;18:925–933. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courtneidge SA, Smith AE. Polyoma virus transforming protein associates with the product of the c-src cellular gene. Nature. 1983;303:435–439. doi: 10.1038/303435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whyte P, Buchkovich KJ, Horowitz JM, Friend SH, Raybuck M, Weinberg RA, Harlow E. Association between an oncogene and an anti-oncogene: the adenovirus E1A proteins bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature. 1988;334:124–129. doi: 10.1038/334124a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovesdi I, Reichel R, Nevins JR. Identification of a cellular transcription factor involved in E1A trans-activation. Cell. 1986;45:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whyte P, Williamson NM, Harlow E. Cellular targets for transformation by the adenovirus E1A proteins. Cell. 1989;56:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90984-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckner R, Ludlow JW, Lill NL, Oldread E, Arany Z, Modjtahedi N, DeCaprio JA, Livingston DM, Morgan JA. Association of p300 and CBP with simian virus 40 large T antigen. Molecular and cellular biology. 1996;16:3454–3464. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan DR, Whitman M, Schaffhausen B, Pallas DC, White M, Cantley L, Roberts TM. Common elements in growth factor stimulation and oncogenic transformation: 85 kd phosphoprotein and phosphatidylinositol kinase activity. Cell. 1987;50:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahn WC, Weinberg RA. Modelling the molecular circuitry of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:331–341. doi: 10.1038/nrc795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Shea CC. Viruses - seeking and destroying the tumor program. Oncogene. 2005;24:7640–7655. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Shea CC. DNA tumor viruses -- the spies who lyse us. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2005;15:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dilworth SM. Cell alterations induced by the large T-antigens of SV40 and polyoma virus. Semin Cancer Biol. 1990;1:407–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moule MG, Collins CH, McCormick F, Fried M. Role for PP2A in ARF signaling to p53. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:14063–14066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405533101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arroyo JD, Hahn WC. Involvement of PP2A in viral and cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2005;24:7746–7755. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Shea C, Klupsch K, Choi S, Bagus B, Soria C, Shen J, McCormick F, Stokoe D. Adenoviral proteins mimic nutrient/growth signals to activate the mTOR pathway for viral replication. The EMBO journal. 2005;24:1211–1221. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Shea CC, Choi S, McCormick F, Stokoe D. Adenovirus Overrides Cellular Checkpoints for Protein Translation. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 2005;7:883–888. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.7.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang SS, Esplin ED, Li JL, Huang L, Gazdar A, Minna J, Evans GA. Alterations of the PPP2R1B gene in human lung and colon cancer. Science (New York, NY. 1998;282:284–287. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SS, Glaunsinger B, Mantovani F, Banks L, Javier RT. Multi-PDZ domain protein MUPP1 is a cellular target for both adenovirus E4-ORF1 and high-risk papillomavirus type 18 E6 oncoproteins. Journal of virology. 2000;74:9680–9693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9680-9693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finlay BB, McFadden G. Anti-immunology: evasion of the host immune system by bacterial and viral pathogens. Cell. 2006;124:767–782. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:836–848. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgert HG, Kvist S. An adenovirus type 2 glycoprotein blocks cell surface expression of human histocompatibility class I antigens. Cell. 1985;41:987–997. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosa F, Berissi H, Weissenbach J, Maroteaux L, Fellous M, Revel M. The beta2-microglobulin mRNA in human Daudi cells has a mutated initiation codon but is still inducible by interferon. The EMBO journal. 1983;2:239–243. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horton TM, Ranheim TS, Aquino L, Kusher DI, Saha SK, Ware CF, Wold WS, Gooding LR. Adenovirus E3 14.7K protein functions in the absence of other adenovirus proteins to protect transfected cells from tumor necrosis factor cytolysis. Journal of virology. 1991;65:2629–2639. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2629-2639.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen P, Tian J, Kovesdi I, Bruder JT. Interaction of the adenovirus 14.7-kDa protein with FLICE inhibits Fas ligand-induced apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:5815–5820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tollefson AE, Hermiston TW, Lichtenstein DL, Colle CF, Tripp RA, Dimitrov T, Toth K, Wells CE, Doherty PC, Wold WS. Forced degradation of Fas inhibits apoptosis in adenovirus-infected cells. Nature. 1998;392:726–730. doi: 10.1038/33712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tollefson AE, Toth K, Doronin K, Kuppuswamy M, Doronina OA, Lichtenstein DL, Hermiston TW, Smith CA, Wold WS. Inhibition of TRAIL-induced apoptosis and forced internalization of TRAIL receptor 1 by adenovirus proteins. Journal of virology. 2001;75:8875–8887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.8875-8887.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SH, Shin MS, Kim HS, Park WS, Kim SY, Jang JJ, Rhim KJ, Jang J, Lee HK, Park JY, Oh RR, Han SY, Lee JH, Lee JY, Yoo NJ. Somatic mutations of Fas (Apo-1/CD95) gene in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma arising from a burn scar. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:122–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pai SI, Wu GS, Ozoren N, Wu L, Jen J, Sidransky D, El-Deiry WS. Rare loss-of-function mutation of a death receptor gene in head and neck cancer. Cancer research. 1998;58:3513–3518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pasparakis M. Regulation of tissue homeostasis by NF-kappaB signalling: implications for inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:778–788. doi: 10.1038/nri2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Kang J, Friedman J, Tarassishin L, Ye J, Kovalenko A, Wallach D, Horwitz MS. Identification of a cell protein (FIP-3) as a modulator of NF-kappaB activity and as a target of an adenovirus inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:1042–1047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Natoli G, Karin M. IKK-gamma is an essential regulatory subunit of the IkappaB kinase complex. Nature. 1998;395:297–300. doi: 10.1038/26261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalvakolanu DV, Bandyopadhyay SK, Harter ML, Sen GC. Inhibition of interferon-inducible gene expression by adenovirus E1A proteins: block in transcriptional complex formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:7459–7463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang JJ, Vinkemeier U, Gu W, Chakravarti D, Horvath CM, Darnell JE., Jr Two contact regions between Stat1 and CBP/p300 in interferon gamma signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:15092–15096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cattaneo R, Miest T, Shashkova EV, Barry MA. Reprogrammed viruses as cancer therapeutics: targeted, armed and shielded. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:529–540. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borden EC, Lindner D, Dreicer R, Hussein M, Peereboom D. Second-generation interferons for cancer: clinical targets. Semin Cancer Biol. 2000;10:125–144. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Halbert DN, Cutt JR, Shenk T. Adenovirus early region 4 encodes functions required for efficient DNA replication, late gene expression, and host cell shutoff. Journal of virology. 1985:250–257. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.1.250-257.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russell WC. Update on adenovirus and its vectors. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2573–2604. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-11-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Rutz B, Wilm M, Mann M, Seraphin B. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1030–1032. doi: 10.1038/13732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puig O, Caspary F, Rigaut G, Rutz B, Bouveret E, Bragado-Nilsson E, Wilm M, Seraphin B. The tandem affinity purification (TAP) method: a general procedure of protein complex purification. Methods. 2001;24:218–229. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gavin AC, Bosche M, Krause R, Grandi P, Marzioch M, Bauer A, Schultz J, Rick JM, Michon AM, Cruciat CM, Remor M, Hofert C, Schelder M, Brajenovic M, Ruffner H, Merino A, Klein K, Hudak M, Dickson D, Rudi T, Gnau V, Bauch A, Bastuck S, Huhse B, Leutwein C, Heurtier MA, Copley RR, Edelmann A, Querfurth E, Rybin V, Drewes G, Raida M, Bouwmeester T, Bork P, Seraphin B, Kuster B, Neubauer G, Superti-Furga G. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature. 2002;415:141–147. doi: 10.1038/415141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Major MB, Camp ND, Berndt JD, Yi X, Goldenberg SJ, Hubbert C, Biechele TL, Gingras AC, Zheng N, Maccoss MJ, Angers S, Moon RT. Wilms tumor suppressor WTX negatively regulates WNT/beta-catenin signaling. Science (New York, NY. 2007;316:1043–1046. doi: 10.1126/science/1141515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Junttila MR, Saarinen S, Schmidt T, Kast J, Westermarck J. Single-step Strep-tag purification for the isolation and identification of protein complexes from mammalian cells. Proteomics. 2005;5:1199–1203. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tackett AJ, DeGrasse JA, Sekedat MD, Oeffinger M, Rout MP, Chait BT. I-DIRT, a general method for distinguishing between specific and nonspecific protein interactions. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1752–1756. doi: 10.1021/pr050225e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu H, Bilgin M, Bangham R, Hall D, Casamayor A, Bertone P, Lan N, Jansen R, Bidlingmaier S, Houfek T, Mitchell T, Miller P, Dean RA, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Global analysis of protein activities using proteome chips. Science (New York, NY. 2001;293:2101–2105. doi: 10.1126/science.1062191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Querido E, Marcellus RC, Lai A, Charbonneau R, Teodoro JG, Ketner G, Branton PE. Regulation of p53 levels by the E1B 55-kilodalton protein and E4orf6 in adenovirus-infected cells. Journal of virology. 1997;71:3788–3798. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3788-3798.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stracker TH, Carson CT, Weitzman MD. Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature. 2002;418:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature00863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Shea CC, Soria C, Bagus B, McCormick F. Heat shock phenocopies E1B-55K late functions and selectively sensitizes refractory tumor cells to ONYX-015 oncolytic viral therapy. Cancer cell. 2005;8:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ptacek J, Devgan G, Michaud G, Zhu H, Zhu X, Fasolo J, Guo H, Jona G, Breitkreutz A, Sopko R, McCartney RR, Schmidt MC, Rachidi N, Lee SJ, Mah AS, Meng L, Stark MJ, Stern DF, De Virgilio C, Tyers M, Andrews B, Gerstein M, Schweitzer B, Predki PF, Snyder M. Global analysis of protein phosphorylation in yeast. Nature. 2005;438:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nature04187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gupta R, Kus B, Fladd C, Wasmuth J, Tonikian R, Sidhu S, Krogan NJ, Parkinson J, Rotin D. Ubiquitination screen using protein microarrays for comprehensive identification of Rsp5 substrates in yeast. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:116. doi: 10.1038/msb4100159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]