Abstract

A principle response of C3 plants to increasing concentrations of atmospheric CO2 (CO2) is to reduce transpirational water loss by decreasing stomatal conductance (gs) and simultaneously increase assimilation rates. Via this adaptation, vegetation has the ability to alter hydrology and climate. Therefore, it is important to determine the adaptation of vegetation to the expected anthropogenic rise in CO2. Short-term stomatal opening–closing responses of vegetation to increasing CO2 are described by free-air carbon enrichments growth experiments, and evolutionary adaptations are known from the geological record. However, to date the effects of decadal to centennial CO2 perturbations on stomatal conductance are still largely unknown. Here we reconstruct a 34% (±12%) reduction in maximum stomatal conductance (gsmax) per 100 ppm CO2 increase as a result of the adaptation in stomatal density (D) and pore size at maximal stomatal opening (amax) of nine common species from Florida over the past 150 y. The species-specific gsmax values are determined by different evolutionary development, whereby the angiosperms sampled generally have numerous small stomata and high gsmax, and the conifers and fern have few large stomata and lower gsmax. Although angiosperms and conifers use different D and amax adaptation strategies, our data show a coherent response in gsmax to CO2 rise of the past century. Understanding these adaptations of C3 plants to rising CO2 after decadal to centennial environmental changes is essential for quantification of plant physiological forcing at timescales relevant for global warming, and they are likely to continue until the limits of their phenotypic plasticity are reached.

Keywords: cuticular analysis, subtropical vegetation

Land plants play a crucial role in regulating our planet's hydrological and energy balance by transpiring water through the stomatal pores on their leaf surfaces. A fundamental response of C3 plants to increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration (CO2) is to minimize transpirational water loss by reducing diffusive stomatal conductance (gs) and simultaneously increasing assimilation rates (1). The resulting increased intrinsic water-use efficiency (iWUE: the ratio of assimilation to gs) improves the vegetation's drought resistance and reduces the cost associated with the leaf's water transport system like leaf venation (2, 3). On a regional to global scale, decreasing rates of transpiration concurrently affect climate through reduced cloud formation and precipitation (4) and with this exert a physiological feedback on climate and hydrology on top of the radiative forcing of increasing CO2 (5–7). In the light of continuing anthropogenic climate change, it is therefore imperative to determine how plants adapt to rising atmospheric CO2.

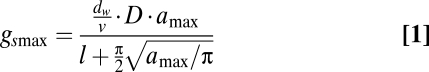

During their 400 million year history, land plants have been exposed to large variations in environmental conditions that prompted genetic adaptations toward mechanisms that optimize individual fitness. Over this period, plant adaptation to CO2 is apparent as periods with high CO2 favored species with few relatively large stomata and low gs, whereas periods with low CO2 (as at present) favored species with many relatively small stomata and higher gs (8). Moreover, decreasing CO2 after ≈100 million years likely triggered the evolutionary development of a more extensive leaf vein network in angiosperms, giving them the advantage of potentially higher gs than gymnosperms with low vein density (9). At shorter timescales, plants have the ability to adjust their phenotype to optimize gas exchange. In response to short (seconds to hours) perturbations in CO2, plants open and close their stomata (10, 11), whereas in response to CO2 changes at decadal to centennial timescales, plants adjust leaf stomatal density (D) and/or maximum stomatal dimensions (amax) (12–15). This process of epidermal structural adaptation is in part controlled by a signaling mechanism from mature to developing leaves, optimizing stomatal density and size to the changed environmental conditions (16). These epidermal characteristics determine the anatomical maximum stomatal conductance to water vapor (gsmax, mol·m−2·s−1) of fully opened stomata and can be calculated as (8, 17):

|

in which stomatal density [D (number of stomata·m−2)], the size of the fully opened stomata amax (m2), and depth of the stomatal tube l (m) are the determining variables. The diffusivity of water vapor dw (m2·s−1) and the molar volume of air v (m3·mol−1) are constants. Values of amax and l are derived from the stomatal pore length L (m). Maximum stomatal conductance to CO2 is gsmax/1.6 (18).

The most comprehensive analyses of plant adaptation to elevated CO2 in (semi)natural environments are available from free-air carbon enrichments (FACE) growth experiments (19). Although decreases in D of C3 plants did occur in some studies (20), the observed reduction in gs was found to be caused by instantaneous adaptation only (21). Apparently, the run-time of these growth experiments of <5 y might be too short to trigger statistically significant epidermal structural adaptation (22). Consequently, the subtle adaptation of vegetation to continuously increasing CO2 can only be elucidated from material covering periods long enough to deduce quantifiable structural adaptation. Because CO2 has already increased by ≈100 ppm over the past 150 y, historical leaves preserved in sediments and stored in herbarium collections offer an excellent opportunity to study the adaptation of gsmax to the gradual rise in CO2.

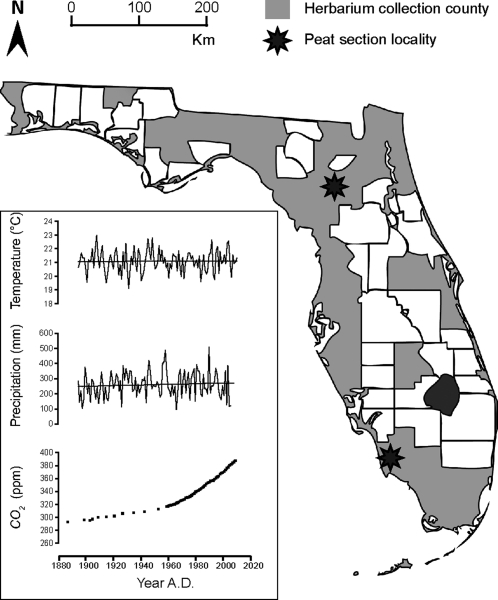

Because the leaf epidermal properties D and amax are also influenced by other environmental factors such as light, temperature, and water availability (23–25), it is necessary to use leaf material from plants that grew under conditions in which the global CO2 rise is the dominant variable factor. This prerequisite is met in Florida, where the vegetation has been exposed to the global ≈100 ppm CO2 increase under near constant average growth season temperatures and precipitation rates over the past 150 y (Fig. 1). Moreover, structural adaptation to increasing CO2 by decreasing D has already been demonstrated for a number of Florida forest taxa (28, 29).

Fig. 1.

Locations of leaf material collection sites in Florida: state counties covered by herbarium material (gray) and subfossil leaf fragment sites (black stars). Florida averaged spring (March, April, and May) temperature and cumulative precipitation (http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov) and global atmospheric CO2 concentration [Siple station (26); Mauna Loa (27)] from 1880 A.D. to present are given. The various sites are situated approximately at sea level. Black lines in the temperature and precipitation graphs are long-term means of ≈21 °C and ≈260 mm, respectively.

Here we present a high-resolution historical record of nine C3 species that adapted gsmax to the 100 ppm rise in CO2 since approximately 1880 A.D. Species studied are the woody angiosperms Acer rubrum (Aceraceae), Myrica cerifera (Myricaceae), Ilex cassine (Aquifoliaceae), Quercus laurifolia (Fagaceae), and Quercus nigra (Fagaceae), the conifers Pinus elliottii (Pinaceae), Pinus taeda (Pinaceae), and Taxodium distichum (Cupressaceae), and the fern Osmunda regalis (Osmundaceae). This selection embraces species with deciduous and evergreen leaf types, growing in wet to well-drained sites in upper to lower canopy layers (Table S1). The cuticle material analyzed originates from subfossil leaf fragments retrieved from well-dated young peat deposits (26, 30) as well as herbarium and modern material collected from various sites in Florida (Fig. 1).

In the present study we aim to quantify how these species have adapted gsmax in response to the industrial rise in CO2. Moreover, the present selection includes multiple angiosperm and coniferous species, of which the leaves are characterized by a high and low leaf vein density, respectively. Because angiosperms have invested more in an elaborate leaf hydraulic system (31), we raise the hypothesis that they will benefit more by reducing gsmax stronger to rising CO2. The data we present here allow for quantification of plant physiological adaptation at timescales relevant for anthropogenic climate change and provide much-needed data for parameterization and validation of climate models that include these physiological feedbacks.

Results

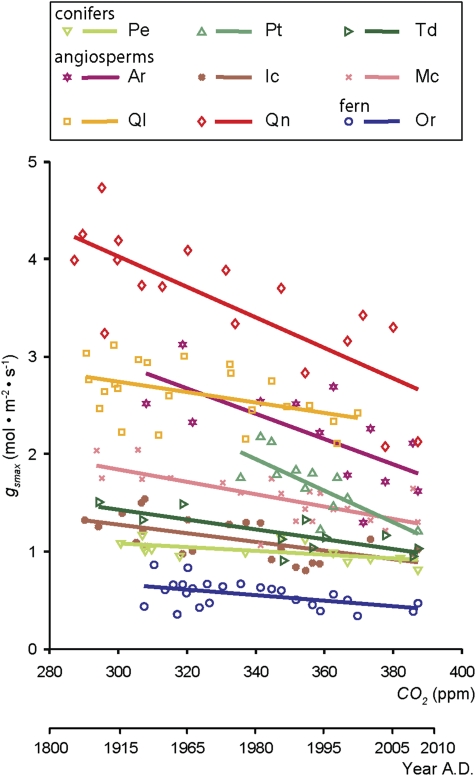

A consistent decrease in gsmax over the anthropogenic rise in CO2 is observed in all species studied (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). The inferred gsmax values of these nine species range between ≈0.4 (mol·m−2·s−1) to ≈4 (mol·m−2·s−1), with the highest values for the angiosperm canopy species Q. nigra, Q. laurifolia, and A. rubrum and the lowest values for the fern O. regalis. Despite the large differences in absolute values of gsmax between species, relative sensitivities in gsmax over ≈100 ppm CO2 rise are highly comparable, with a mean slope of −34% (±12%) per 100 ppm (Table 1). The weakest responses occur in P. elliottii and Q. laurifolia, with a relative sensitivity of only −17% and −18% per 100 ppm, whereas P. taeda shows the strongest sensitivity in gsmax, with −55% per 100 ppm. Despite these differences in response rate, the total change exceeds the maximum intrinsic variability quantified as the root mean square error (RMSE) in all species (Table S2). The CO2-induced phenotypic decrease in gsmax on decadal timescales resembles evolutionary gsmax adaptation over geological timescales (32), reflecting the permanent attempt of plants to optimize individual fitness.

Fig. 2.

Species-specific relation between gsmax and CO2 over the past 150 y. Symbols are average gsmax (mol·m−2·s−1) for each species per CO2 level (ppm) studied (n = 160), and accompanying year A.D. (species names and abbreviations are given in Table 1). Solid lines show linear regressions between CO2 and gsmax for each species, r2 and relative sensitivity are given in Table 1. The functions and RMSE for each species are provided in Table S2.

Table 1.

Relative sensitivity of gsmax, D, and amax to CO2 increase for the species sampled (intercept, 100% at 280 ppm CO2), with r2 of the linear regressions used

| Average gsmax | Average stomatal density D | Average pore size amax | |||||

| Species | Species code | Relative sensitivity (%·ppm−1) | r2 | Relative sensitivity (%·ppm−1) | r2 | Relative sensitivity (%·ppm−1) | r2 |

| Acer rubrum | Ar | −0.41* | 0.45 | −0.29* | 0.30 | −0.27* | 0.40 |

| Ilex cassine | Ic | −0.30* | 0.36 | −0.26* | 0.38 | −0.13 | 0.04 |

| Myrica cerifera | Mc | −0.36* | 0.49 | −0.31* | 0.40 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Osmunda regalis | Or | −0.42* | 0.24 | −0.27 | 0.09 | −0.31* | 0.31 |

| Pinus elliottii | Pe | −0.17* | 0.36 | −0.23* | 0.55 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| Pinus taeda | Pt | −0.55* | 0.54 | −0.42* | 0.56 | −0.25 | 0.25 |

| Quercus laurifolia | Ql | −0.18* | 0.21 | −0.09 | 0.13 | −0.14 | 0.07 |

| Quercus nigra | Qn | −0.37* | 0.61 | −0.28* | 0.44 | −0.21 | 0.18 |

| Taxodium distichum | Td | −0.33* | 0.58 | −0.35* | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

*Statistical significance for the regression as well as the change, with P < 0.05.

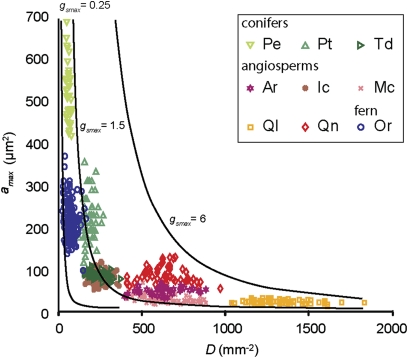

As on geological timescales (8), combined values of D and amax on which the calculation of gsmax is based here are negatively correlated and follow a power law relationship in which high values of D are accompanied by low amax values, and vice versa (Fig. 3). For individual species, however, D and amax are confined to specific ranges forming clusters distributed along this power law, where significant negative correlations are also apparent in five out of nine individual clusters (P. elliottii, T. distichum, Q. laurifolia, M. cerifera, and O. regalis; Table S3). This implies that the clusters represent the phenotypic plasticity of the various species, showing adjustments of both D and amax that occurred in response to the complex of environmental perturbations to which the sampled vegetation was exposed, including CO2.

Fig. 3.

The measured stomatal density [D (mm−2)] and pore size [amax (μm2)] of nine common species in Florida (n = 667) (species names and abbreviations as in Table 1). The clusters depict a phenotypical range of D and amax for each species under changing conditions of the past 150 y. Approximate lower limits are D = ≈20 mm−2 and amax = ≈15 μm2. Multiple combination of D and amax can lead to the same gsmax value (mol·m−2·s−1), indicated by the black curved lines.

Within the total dataset, the most prominent difference exists between the angiosperm clusters with many small stomata that display large diversity in D and the conifers and fern clusters with few large stomata that display large diversity in amax. The position of individual species on this power law curve likely represents their different evolutionary history (33, 34), with an earlier design for conifers and ferns and a more innovative design for angiosperms. Nevertheless, different combinations of D and amax can lead to the same gsmax (Fig. 3) and the same decrease in gsmax in response to rising CO2 (Table 1).

Testing the CO2 sensitivity of D and amax individually, we observe that the plastic response of D is always negative and more pronounced than in amax (Table 1). This consistent decrease of D under rising CO2 has already been reported for the angiosperm and fern species in our dataset (26, 27). We now complement the range of species known to reduce D in response to rising CO2 by including the conifers P. elliottii, P. taeda, and T. distichum. Over the sampled CO2 rise in CO2, the relative sensitivity in D varies from maximal −42% per 100 ppm in P. taeda to minimal −9% per 100 ppm in Q. laurifolia (Table 1) (P < 0.05 for all but O. regalis and Q. laurifolia, with P = 0.12 and P = 0.10, respectively). The total change in D exceeds the maximum intrinsic variability quantified as the RMSE in all species except O. regalis and Q. laurifolia (Table S4). These rates are broadly consistent with decreases in D reported for European tree species grown under anthropogenic CO2 increase (12, 13, 15, 35).

Focusing on the changes in amax over the sampled CO2 increase, weak and unidirectional relations are observed. Significant relations were only found for A. rubrum and O. regalis, which show reductions in amax of −27% and −31% per 100 ppm, respectively (Table 1). Moreover, the changes in our amax data series only exceed the RMSE for five of the species studied (Table S5). This variable response is different from changes in amax to anthropogenic CO2 rise reported earlier for two European tree species, for which a weak increase was observed (13, 36). From these observations it is apparent that D is highly sensitive to rising CO2, whereas changes in amax are variable between species and seem to be governed independently.

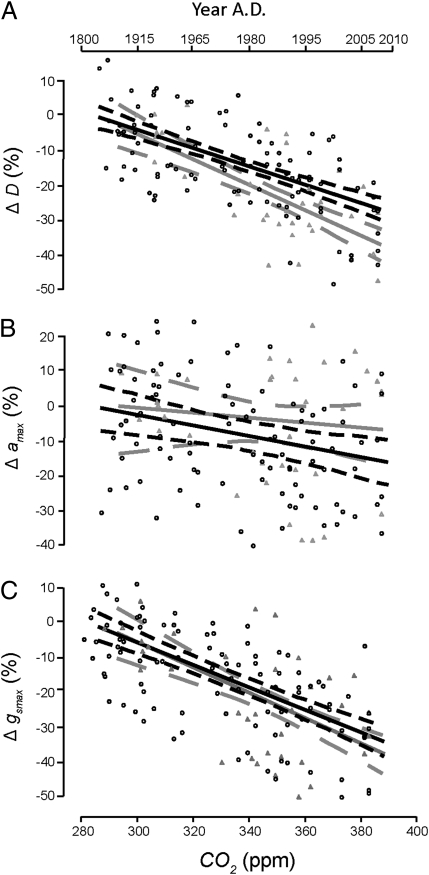

Because it is hypothesized that the different leaf structures, in particular leaf vein density, of angiosperms and conifers (31) result in different epidermal structural responses to rising CO2, we compared the general relative sensitivities of the two plant groups in our dataset. Results show that coniferous species seem to respond with a significantly stronger decrease in D (slope, −35% per 100 ppm) than angiosperms (slope, −27% per 100 ppm) (Fig. 4A and Table S6). Conversely, angiosperms respond with an apparent but not significantly stronger decrease in amax (slope, −15% per 100 ppm) compared with the conifers (slope, −7% per 100 ppm). Conifers also display a much larger range of variability, indicated by the broader confidence interval (Fig. 4B). Despite these differences, a highly comparable overall decrease in gsmax to a rise of CO2 from preindustrial to present in angiosperms (slope, −33% per 100 ppm) and conifers (slope, −37% per 100 ppm) emerges from this combination (Fig. 4C). Summarizing, our data show that both angiosperms and conifers exhibit a similar response in gsmax to the anthropogenic rise in CO2.

Fig. 4.

Relative sensitivity in D (A), amax (B), and gsmax (C) of the grouped angiosperm species (black line, black dots) and coniferous species (gray line, gray triangles) over the sampled CO2 increase since the industrial revolution. Dashed lines depict 95% confidence intervals for angiosperms (black short dashed lines) and conifers (gray long dashed lines). (SE, r2, and P values given in Table S6). Only D is significantly different between angiosperms and conifers (P < 0.001).

Discussion

The presented data reveal that the nine species from Florida reduce their gsmax in response to the industrial CO2 rise via D and amax adaptation within their phenotypic plasticity. This likely represents the plants’ adaptation to increase iWUE by optimizing carbon gain to water loss (11, 37). We demonstrate that adaptation of gsmax is achieved by species-specific strategies to alter D and/or amax. The overall decrease in gsmax is predominantly the result of a general and significant reduction of D in response to rising CO2 in all species, whereas amax seems to adapt to other environmental conditions as well, because no consistent relation with CO2 was observed. However, the importance of including D as well as amax in the reconstruction of gsmax is emphasized by the generally improved correlation of gsmax with CO2, compared with D and amax separately (Table 1). The observed change in amax opposes the positive relation between pore size and CO2 found over geological timescales (8). This discrepancy can be explained by considering that on the timescale studied here plants adapt within their phenotype and not genotype to reduce gsmax, which is most efficiently done by reducing rather than increasing pore size. This suggests that plants can and do adapt to changing conditions by fine-tuning D and amax plastically to optimize their individual fitness.

Despite the consistent trend observed in gsmax, considerable variability characterizes the individual D and amax data series, and consequently gsmax, because climatic and site-specific environmental factors such as light, temperature, and water availability affect D and amax as well (22, 24, 25). Even though the long-term mean temperature and precipitation in Florida have not changed over the past 150 y, strong interannual temperature and precipitation fluctuations (Fig. 1) caused by the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation teleconnections (38, 39) may in part have caused D and amax variability. Indeed, short-term changes in epidermis morphology in Q. laurifolia have been linked to ENSO-tied winter precipitation (25). Together with D and amax diversity throughout the canopy and even within the same leaf (40), these environmental factors produce substantial scatter in the data. Consequently, sampling on low temporal resolution might explain the lack of evidence for CO2-induced iWUE adaptation as in herbarium studies covering 2 to 5 selected years only (41). The present study therefore emphasizes the necessity of sufficiently high-resolution as well as multidecadal data series to elucidate the long-term subtle response of gsmax to changing CO2.

The large variation in reconstructed gsmax values reflect the difference in leaf vascular architecture, whereby the high vein density typical for angiosperms allows for high gsmax and the low vein density in ferns and conifers is reflected by low gsmax (31, 42). The differences in the leaf hydraulic systems between angiosperms and conifers are also expressed in their position on the power law relation between D and amax. Angiosperms reach high gsmax with numerous small stomata, and conifers reach lower gsmax with fewer large stomata (8). These findings can be placed against an evolutionary background, where ferns and conifers evolved in a higher-than-present CO2 world, in which lower gsmax would be perfectly sufficient to maintain high photosynthesis. The late Cretaceous drop in CO2 likely triggered the expansion of the leaf-vascular network in angiosperms (9), allowing them to attain higher photosynthesis rates than conifers and ferns but at the cost of high carbon and transpirational water loss (3). This water loss in angiosperms might be minimized as small stomata are faster to close than large stomata under desiccating conditions (43). Moreover, a consequence of the associated high water loss is the resulting evaporative cooling, which maintains an optimal leaf temperature (44). Our data thus show that species-specific gsmax is determined in part by evolutionary adaptation to conditions in which they evolved.

When exposed to decadal variability the species studied adapt within the limits of their phenotypic plasticity, by adjusting D and amax. Despite the large differences in D and amax between species, even within the same genus they all exhibit highly comparable adaptation of gsmax to increasing CO2. Comparing the general adaptation of the angiosperms and conifers as groups, however, a different strategy to reduce gsmax was observed, depending on their position on the power law curve. Although only the relative change in D between angiosperms and conifers is significantly different, the tendency towards an opposite response in D and amax does illustrate that variable adaptations lead to the same reduction in gsmax. These results can be explained by the different position on the power law curve, whereby species reduce gsmax most efficiently by changing either D or amax to get the steepest gradient in gsmax (Fig. 2). Because the construction of an extended vascular network is coupled to high carbon costs (3, 42), it was hypothesized before that angiosperms reduce gsmax more than conifers and ferns. However, our data show a highly comparable sensitivity to the industrial CO2 rise in all groups sampled and thereby demonstrate the underlying principle that plants generally optimize their leaf structure in response to rising CO2, apparently irrespective of their leaf architecture.

Having discussed the responses and possible underlying mechanisms, the potential further development of gsmax under future increasing CO2 can be evaluated. The iWUE responses measured in short-term growth experiments over below-present to present CO2 levels are also found to be comparable in angiosperms, conifers, and ferns, but the trends diverge from present to elevated CO2, where the response in conifers and ferns levels off (45). Our results of structural adaptation from ≈280 ppm to 387 ppm CO2 does not bear any evidence for a diverging response between plant lineages. Whether any gsmax off-leveling will occur under continuing CO2 enrichment, and at what CO2 concentration this will happen, should be estimated by modeling exercises incorporating adaptation within the species-specific phenotypic plasticity (37).

In conclusion, our results point to a common mechanism in C3 plants to reduce maximum stomatal conductance via adjustment of stomatal density and pore size within the limits of their phenotypic plasticity on a decadal timescale. As atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration is rising, plants can and do reduce water loss by reducing maximal stomatal conductance while maintaining carbon uptake (3, 31). Further decreases in stomatal conductance have been observed at CO2 rising above present levels in FACE short-term experiments (21) and in fossil leaves over geological timescales (8). Both lines of evidence, however, fall beyond or below the timescales of the projected rate of continuing CO2 increase, which is likely to surpass the time needed for adaptation via natural selection. Consequently, the adaptation within the phenotypic plasticity is likely to constrain epidermis structural adaptation in the near future when phenotypic response limits are reached (35, 37). Current increase in CO2 and the coinciding reduction in plant transpiration already results in increased continental run-off (46), and climate models predict surface temperature increases arising from reduced evaporative cooling (6, 7). The mechanisms of optimization of carbon gain to water loss described here could be used to better estimate this physiological forcing for the past and future CO2 but should be considered within the framework of species-specific phenotypic plasticity (37).

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation and Analysis.

The leaf fragments were treated in 4% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO2) at 40 °C for several minutes up to 24 h, after which the stomata-bearing abaxial cuticle could be peeled off from the mesophyll, dyed with saffranine, and mounted in glycerine jelly. Because Pinus has an approximately equal amount of stomata on the abaxial as well as the adaxial surface, the entire cuticle was processed. Standardized, computer-aided analysis of the epidermal properties was performed on Leica Quantimet 500C/500+ and AnalySIS image analysis systems. Stomatal density (D; number of stomata·m−2) was measured on 5–10 alveoles of each leaf sample and averaged. Because of different epidermis cell patterning, Pinus is measured with the stomatal rows running diagonally in the image. Pore length (L; μm) is determined by averaging measurements of ≈25 stomata for each sample. Data are available upon request.

Calculating gsmax to Water Vapor.

To determine the stomatal conductance to water vapor gsmax (mol·m−2·s−1), the equation provided by Franks and Farquhar (17) is applied, using a two-way end correction accounting for the diffusion shells (8) (Eq. 1). Maximum pore surface area amax (m2) is defined as an ellipse and quantified as π·L2/8, with L being stomatal pore length (m). Stomatal pore depth l (m) is assumed to be equal to the guard cell width of the stomata when the guard cell is fully inflated (8). Quantification of l follows from the significant positive linear relations between pore length and guard cell width for each species, with exception of P. taeda, for which a constant value is taken (Table S7). Values used for gas constants d and v are those for 25 °C. For the determination of the long-term relative sensitivities of the measured D and amax, and consequent gsmax, the regressions are performed on values averaged per sampled year.

Statistical Analyses.

The significance of the observed regressions presented here is tested in three steps, with P values of <0.05 considered statistically significant. First, the significance of each regression plotted through the data series was tested. Second, using a Student t test on the slopes of these regressions, it was determined whether the observed changes were significantly larger than 0. Finally, to test whether the average responses in D, amax, and gsmax were significantly different between angiosperms and conifers, a t test (two samples assuming unequal variances) was performed on the pooled data of each group within the CO2 interval of 360–387 ppm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank H. van Konijnenburg-van Cittert, J. van der Burgh, M. Rietkerk, H. Visscher, and two reviewers for useful comments and discussion on this work; L. Bik for graphical support; K. Perkins of the University of Florida Herbarium for assistance in selecting samples; and Florida Park Service–District 4 for its overall support. This research was funded by the High Potential program of Utrecht University. This report is Netherlands Research School of Sedimentary Geology publication no. 2011.01.01.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1100371108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cowan IR, Farquhar GD. Stomatal function in relation to leaf metabolism and environment. In: Jennings DH, editor. Integration of Activity in the Higher Plants. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1977. pp. 471–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raven JA. Selection pressures on stomatal evolution. New Phytol. 2002;153:371–386. doi: 10.1046/j.0028-646X.2001.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beerling DJ, Franks PJ. Plant science: The hidden cost of transpiration. Nature. 2010;464:495–496. doi: 10.1038/464495a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonan GB. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science. 2008;320:1444–1449. doi: 10.1126/science.1155121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betts RA, et al. Projected increase in continental runoff due to plant responses to increasing carbon dioxide. Nature. 2007;448:1037–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature06045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews T, Doutriaux-Boucher M, Boucher O, Forster PM. A regional and global analysis of carbon dioxide physiological forcing and its impact on climate. Clim Dyn. 2010 10.1007/s00382-010-0742-1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao L, Bala G, Caldeira K, Nemani R, Ban-Weiss G. Importance of carbon dioxide physiological forcing to future climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9513–9518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franks PJ, Beerling DJ. Maximum leaf conductance driven by CO2 effects on stomatal size and density over geologic time. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10343–10347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904209106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodribb TJ, Feild TS. Leaf hydraulic evolution led a surge in leaf photosynthetic capacity during early angiosperm diversification. Ecol Lett. 2010;13:175–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farquhar GD, Dubbe DR, Raschke K. Gain of the feedback loop involving carbon dioxide and stomata: Theory and measurement. Plant Physiol. 1978;62:406–412. doi: 10.1104/pp.62.3.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katul G, Manzoni S, Palmroth S, Oren R. A stomatal optimization theory to describe the effects of atmospheric CO2 on leaf photosynthesis and transpiration. Ann Bot (Lond) 2010;105:431–442. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodward FI. Stomatal numbers are sensitive to increases in CO2 from pre-industrial levels. Nature. 1987;327:617–618. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner F, et al. A natural experiment on plant acclimation: Lifetime stomatal frequency response of an individual tree to annual atmospheric CO2 increase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11705–11708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kürschner WM, van der Burgh J, Visscher H, Dilcher DL. Oak leaves as biosensors of late neogene and early pleistocenepaleoatmospheric CO2 concentrations. Mar Micropaleontol. 1996;27:299–312. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner F, Kouwenberg LLR, van Hoof TB, Visscher H. Reproducibility of Holocene atmospheric CO2 records based on stomatal frequency. Quat Sci Rev. 2004;23:1947–1954. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lake JA, Woodward FI, Quick WP. Long-distance CO(2) signalling in plants. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:183–193. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.367.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franks PJ, Farquhar GD. The effect of exogenous abscisic acid on stomatal development, stomatal mechanics, and leaf gas exchange in Tradescantia virginiana. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:935–942. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farquhar GD, Sharkey TD. Stomatal conductance and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1982;33:317–345. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long SP, Ainsworth EA, Rogers A, Ort DR. Rising atmospheric carbon dioxide: Plants FACE the future. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:591–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reid CD, et al. On the relationship between stomatal characters and atmospheric CO2. Geophys Res Lett. 2003;30:1983–1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ainsworth EA, Rogers A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: Mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:258–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royer DL. Stomatal density and stomatal index as indicators of paleoatmospheric CO(2) concentration. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 2001;114:1–28. doi: 10.1016/s0034-6667(00)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole I, Kürschner WM. Stomatal density and index: The practice. In: Jones TP, Rowe NP, editors. Fossil Plant and Spores: Modern Techniques. London: Geological Society; 1999. pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franks PJ, Drake PL, Beerling DJ. Plasticity in maximum stomatal conductance constrained by negative correlation between stomatal size and density: An analysis using Eucalyptus globulus. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:1737–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner-Cremer F, Donders TH, Visscher H. Drought stress signals in modern and subfossil Quercuslaurifolia (Fagaceae) leaves reflect winter precipitation in southern Florida tied to El Niño-Southern Oscillation activity. Am J Bot. 2010;97:753–759. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neftel A, et al. Trends: A compendium of data on global change. 1994. Available at: http://cdiac.ornl.gov/trends/co2/contents.htm. Accessed February, 2010.

- 27.Keeling CD, Whorf TP. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations—Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii, 1958–2003. 2003. Available at: http://cdiac.ornl.gov/pns/pns_main.html. Accessed February, 2010.

- 28.Wagner F, Dilcher DL, Visscher H. Stomatal frequency responses in hardwood-swamp vegetation from Florida during a 60-year continuous CO2 increase. Am J Bot. 2005;92:690–695. doi: 10.3732/ajb.92.4.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner F, Visscher H, Kürschner WM, Dilcher DL. Influence of ontogeny and atmospheric CO2 on stomata parameters of Osmundaregalis. Cour Forsch Inst Senckenberg. 2007;258:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donders TH, Wagner F, Van der Borg K, De Jong AFM, Visscher H. A novel approach for developing high-resolution sub-fossil peat chronologies with 14C dating. Radiocarbon. 2004;46:455–464. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodribb TJ, Holbrook NM, Zwieniecki MA, Palma B. Leaf hydraulic capacity in ferns, conifers and angiosperms: Impacts on photosynthetic maxima. New Phytol. 2005;165:839–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franks PJ, Beerling DJ. CO(2)-forced evolution of plant gas exchange capacity and water-use efficiency over the Phanerozoic. Geobiology. 2009;7:227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2009.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dilcher D. Toward a new synthesis: Major evolutionary trends in the angiosperm fossil record. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7030–7036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henry RJ. Plant Diversity and Evolution: Genotypic and Phenotypic Variation in Higher Plants. Wallingford, UK: Centre for Agricultural Bioscience International; 2005. p. 332. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kürschner WM. The anatomical diversity of recent and fossil leaves of the durmast oak (QuercuspetraeaLieblein/Q. pseudocastaneaGoeppert)—implications for their use as biosensors of palaeoatmospheric CO2 levels. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1997;96:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Amorena I, Wagner F, van Hoof TB, Gómez Manzaneque F. Stomatal responses in deciduous oaks from southern Europe to the anthropogenic atmospheric CO2 increase; refining the stomatal-based CO2 proxy. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 2006;141:303–312. [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Boer HJ, et al. Climate forcing due to optimization of maximal leaf conductance in subtropical vegetation under rising CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100555108. 10.1073/pnas.1100555108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donders TH, Wagner F, Dilcher DL, Visscher H. Mid- to late-Holocene El Nino-Southern Oscillation dynamics reflected in the subtropical terrestrial realm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10904–10908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505015102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curtis S. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and extreme daily precipitation over the US and Mexico during the hurricane season. Clim Dyn. 2008;30:343–351. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poole I, Weyers JDB, Lawson T, Raven JA. Variations in stomatal density and index: Implications for palaeoclimatic reconstructions. Plant Cell Environ. 1996;19:705–712. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller-Rushing AJ, Primack RB, Templer PH, Rathbone S, Mukunda S. Long-term relationships among atmospheric CO2, stomata, and intrinsic water use efficiency in individual trees. Am J Bot. 2009;96:1779–1786. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKown AD, Cochard H, Sack L. Decoding leaf hydraulics with a spatially explicit model: Principles of venation architecture and implications for its evolution. Am Nat. 2010;175:447–460. doi: 10.1086/650721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hetherington AM, Woodward FI. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature. 2003;424:901–908. doi: 10.1038/nature01843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Upchurch DR, Mahan JR. Maintenance of constant leaf temperature by plants—II. experimental observations in cotton. Environ Exp Bot. 1988;28:359–366. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brodribb TJ, McAdam SAM, Jordan GJ, Feild TS. Evolution of stomatal responsiveness to CO(2) and optimization of water-use efficiency among land plants. New Phytol. 2009;183:839–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gedney N, et al. Detection of a direct carbon dioxide effect in continental river runoff records. Nature. 2006;439:835–838. doi: 10.1038/nature04504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.