Abstract

Several lines of evidence from post-mortem, brain imaging, and genetic studies in schizophrenia patients suggest that Gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) deficits may contribute to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Pharmacological induction of a transient GABA-deficit state has been shown to enhance vulnerability of healthy subjects to the psychotomimetic effects of various drugs. Exacerbating or creating a GABA deficit was hypothesized to induce or unmask psychosis in schizophrenia patients, but not in healthy controls. To test this hypothesis, a transient GABA deficit was pharmacologically induced in schizophrenia patients and healthy controls using iomazenil, an antagonist and partial inverse agonist of the benzodiazepine receptor. In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study, clinically stable chronic schizophrenia patients (n=13) received iomazenil (3.7 μg administered intravenously over 10 min). Psychosis was measured using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and perceptual alterations were measured using the Clinician Administered Dissociative Symptoms Scale before and after iomazenil administration. These data were compared with the effects of iomazenil in healthy subjects (n=20). Iomazenil produced increases in psychotic symptoms and perceptual alterations in schizophrenia patients, but not in healthy controls. The greater vulnerability of schizophrenia patients to the effects of iomazenil relative to controls provides further support for the GABA-deficit hypothesis of schizophrenia.

Keywords: GABA, schizophrenia, psychosis, iomazenil

INTRODUCTION

Converging lines of evidence, including postmortem (Benes, 2000; Benes and Berretta, 2001; Benes et al, 1996; Hashimoto et al, 2003; Lewis et al, 2005; Ohnuma et al, 1999; Volk et al, 2000; Volk and Lewis, 2002; Volk et al, 2002; Woo et al, 1998), genetic (reviewed by Charych et al (2009), and brain imaging studies (Ball et al, 1998; Busatto et al, 1997; Schroder et al, 1997; Verhoeff et al, 1999; Yoon et al, 2010), suggest that dysfunction of the gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) system contributes to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. In postmortem studies of schizophrenic patients, alterations in GABAergic transmission have been shown in many ways, including (1) reduced mRNA levels for the GABA-synthesizing enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase-67 (Impagnatiello et al, 1998; Volk et al, 2000), (2) decreased density of axon cartridges of chandelier neurons (Woo et al, 1998), (3) decreased gene expression of the GABA membrane transporter-1 (Ohnuma et al, 1999; Volk and Lewis, 2002), (4) increased density of GABA-A receptors (Benes et al, 1996), (5) elevated density of α1- (Impagnatiello et al, 1998; Ohnuma et al, 1999) and α2-subunit-containing GABA-A receptors at pyramidal neuron axon segments (Volk et al, 2002), (6) decreased Reelin mRNA, which is preferentially expressed in GABAergic interneurons (Impagnatiello et al, 1998), and (7) decreased levels of ankyrin-G, a membrane protein that anchors the GABA receptor complex onto initial axonal segments of pyramidal cells in the area of chandelier cell synapses in superficial cortical area (Cruz et al, 2009). Many of these findings appear to be specific to schizophrenia (Volk and Lewis, 2002). Besides post-mortem data, some in vivo brain imaging (SPECT) studies suggest reduced benzodiazepine (BZ) receptor binding in schizophrenia (Ball et al, 1998; Busatto et al, 1997; Schroder et al, 1997).

GABAergic deficits described above may contribute to the pathophysiology of psychosis by several mechanisms. While it is out of the scope of this paper to discuss all the possible mechanism, a few putative mechanism are discussed below. One mechanism may involve the critical role that GABA interneurons have in synchronizing neural activity and, consequently, in information processing (reviewed in Uhlhaas and Singer, 2010). Sensory perception, emotion, attention, and memory, which are characteristically disturbed in schizophrenia, are based on distributed processes among multiple cortical and subcortical regions. It has been proposed that the neural assemblies representing these processes are functionally ‘bound' together by synchronous high-frequency oscillatory activity to create a coherent cortical representation (Engel and Singer, 2001; Singer, 1999; Singer and Gray, 1995; Tallon-Baudry, 2003; Varela, 2001; Varela, 1995). The spike timing of pyramidal cells and the tuning of neuronal rhythms are largely governed by GABAergic interneurons. Loss of the inhibitory influence of GABAergic interneurons from cell loss or reduced function could lead to a loss of synchronization of pyramidal cell activity, resulting in the loss of associative functions, disruption of normal gating mechanisms, and eventually psychotic symptoms. Consistent with this hypothesis, several lines of evidence suggest that dysfunctional synchronized oscillatory neuronal activity may contribute to the pathophysiology of the perceptual and cognitive abnormalities in schizophrenia (Lewis et al, 2005; Uhlhaas and Singer, 2010).

Another potential mechanism by which GABA contribute to the pathophysiology of psychosis may involve the interactions between the GABA and dopamine (DA) systems. Converging lines of evidence suggest that the activity of DA neurons in the VTA is under tonic inhibitory control by GABA-A receptors (Fritschy and Mohler, 1995; Pirker et al, 2000; Waldvogel et al, 2008). Specifically relevant to this study, systemic administration of GABA-A receptor inverse agonist, FG7142 has been shown to activate VTA neurons (Murphy et al, 1996). Interestingly, FG7142-induced VTA activation was reversed by DA receptor antagonists. It should be noted that FG7142 and iomazenil are both inverse agonists. Therefore, a reduction in GABAergic transmission by GABA-A receptors, as would be the case with iomazenil, in the presence of pre-existing dysregulation of DA function, as is the case in schizophrenia, would be expected to further disinhibit DA systems, leading to a worsening of the DA-related symptoms in schizophrenia (Abi-Dargham et al, 1998; Laruelle et al, 1996). We acknowledge that this study does not directly test whether iomazenil increases neural synchrony deficits or DA dysregulation. Rather, the study measures a very distal outcome—psychotic symptoms that could result from an exacerbation of DA dysregulation or altered neural synchrony. The current report describes how pharmacological induction of GABAergic deficits, with iomazenil, increases psychosis.

Pharmacological induction of GABAergic deficits increases vulnerability to psychosis. Iomazenil (Ro 16–0154) is an iodine analog of the BZ receptor competitive antagonist flumazenil. Iomazenil has high affinity and selectivity for BZ receptors (Kd=0.5 nM) (Johnson et al, 1990). Some of its pharmacological properties are comparable with those of flumazenil (Beer et al, 1990). However, unlike the competitive antagonist flumazenil, which blocks the effects of BZ agonists but lacks intrinsic pharmacological effects (Hunkeler et al, 1981), inverse agonists have intrinsic pharmacological effects opposite to those of BZs (Tallman and Gallager, 1985). In preclinical studies, iomazenil has been shown to behave as a BZ receptor competitive antagonist with inverse agonist effects (Beer et al, 1990; Roche; Schubiger and Hasler, 1989). Similarly, clinical studies demonstrate that iomazenil has anxiogenic effects and at higher doses has proconvulsant effects (Randall, personal communication) that are consistent with inverse agonist activity at BZ receptors. Iomazenil produces a net deficit in GABA function.

Iomazenil has been shown to increase the psychotomimetic effects of the 5-HT2 partial agonist 1-(m-chlorophenyl)piperazine (m-CPP) in healthy subjects (D'Souza et al, 2006). Thus, although neither iomazenil nor m-CPP alone induces psychosis, the combination of iomazenil followed by m-CPP causes measurable psychotic symptoms in healthy subjects. Similarly, unpublished preliminary data from our laboratory suggest that GABA deficits induced by iomazenil pretreatment may also increase the psychotomimetic effects of low-dose amphetamine (0.1 mg/kg, intravenous (IV) infusion over 1 min), which by itself does not induce psychotic symptoms, and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) in healthy subjects. Collectively, these studies suggest that the known vulnerability of schizophrenia patients to the psychotomimetic effects of amphetamine (Laruelle et al, 1999; Laruelle et al, 1996) and Δ9-THC (D'Souza et al, 2005) might result from pre-existing GABA deficits.

Although there is strong support for the existence of a GABA deficit in schizophrenia, the proportion of schizophrenia patients with this deficit is not known. The limited data available suggest that only 50% of schizophrenia patients have lower GABA levels than the lowest level found in healthy normal controls (Yoon et al, 2010). Furthermore, BZ augmentation reduces psychosis in only 30–50% of schizophrenia patients (Wolkowitz and Pickar, 1991).

We hypothesized that if GABA deficits contribute to an increased propensity toward psychosis in schizophrenia, then enhancement of these deficits should exacerbate psychotic symptoms in some schizophrenia patients, but not in healthy normal controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Thirteen chronic, stable schizophrenia patients were recruited and compared with data from 20 healthy normal controls from a previous study (D'Souza et al, 2006). Diagnosis was confirmed by SCID-III-R or SCID-IV. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for both studies were identical other than diagnosis. Included were men, 18–70 years old, who were able to provide informed consent; excluded were those with other Axis-I disorders; substance abuse (by history or urine toxicology); treatment with BZs in the previous week, clozapine, or low-potency antipsychotics (thorazine, thioridazine, mesoridazine); unstable medical conditions; active neurological illness requiring treatment; seizure history; abnormal baseline EKG; suboptimally controlled psychosis (defined as >16 on the four-key positive symptom subscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)); high risk for violence or suicide; and women, as the teratogenic potential of iomazenil is unknown. Potential subjects underwent a thorough medical and psychiatric history, complete physical examination, and a battery of laboratory tests including EEG, EKG, blood chemistry (CBC, BUN, creatinine, fasting blood glucose, electrolytes, liver and thyroid function tests), and urinalysis.

The study was conducted at the Neurobiological Studies Unit (VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT) with the approval of the Institutional Review Boards of VA Connecticut Healthcare System and Yale University School of Medicine. Subjects were recruited by word of mouth, clinician referral, and public advertisement. Subjects were compensated $100 per test day for participating. Confidentiality of study data was assured. Data on the effects of iomazenil in healthy subjects were taken from the iomazenil-only and placebo-only test days of a published study of the interactions of iomazenil and m-CPP (D'Souza et al, 2006). These studies were carried out in the same setting, by the same investigators and raters, during the same time period, using almost identical protocols.

Experimental Design

Subjects completed two test days, during which they received placebo or active (3.7 μg/kg) iomazenil over 10 min in random, counterbalanced order under double-blind conditions. Test days were separated by at least 72 h in order to minimize any carryover effects.

Schedule of testing

The detailed schedule of test procedures is described elsewhere (D'Souza et al, 2006). Subjects were required to refrain from using alcohol, street drugs, psychotropic medications, or caffeinated beverages for 2 weeks before testing and throughout the entire study. Urine toxicology was conducted on each test day to rule out recent drug use; a positive screen resulted in exclusion from the study.

After obtaining IV access and two sets of baseline assessments, subjects were administered active IV iomazenil or placebo (saline over a 10-min period). Behavioral ratings were conducted before (−55 to −30 min) and after (+10 to +30 min) the administration of iomazenil.

Measures

Psychotic symptoms were measured using the four-key positive symptom subscale of the BPRS, which has items for hallucinatory behavior, conceptual disorganization, unusual thought content, and suspiciousness (Overall and Gorham, 1962; Woerner et al, 1988). Perceptual alterations were measured using the Clinician Administered Dissociative Symptoms Scale (CADSS) (Bremner et al, 1998), a scale consisting of 19 self-report items and 8 clinician-rated items (0, not at all; 4, extremely), that evaluates aspects of altered environmental perception, time perception, body perception, feelings of unreality, and memory impairment. The scale has been shown to be sensitive to the effects of other psychoactive drugs, including ketamine and THC (D'Souza et al, 2004; Krystal et al, 1994). Anxiety was measured using the clinician-rated anxiety item of the BPRS, which is sensitive to iomazenil effects (D'Souza et al, 2006). The same research assistant rated both days of a subject and the same group of staff rated both schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Interrater reliability was assessed every 1–2 months, and intraclass coefficients for the BPRS and CADSS were consistently >0.85.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 17. Demographic data were compared using independent t-tests. As the BPRS and CADSS data were not normally distributed in controls, and as there were obvious baseline differences between the two groups, peak change from baseline was used in the analysis of these behavioral outcome variables. These variables were analyzed using repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA) with iomazenil (active vs placebo) as within-subject factor and group (schizophrenia vs control) as between-subject factors.

RESULTS

Schizophrenia patients were significantly older, less educated, and less employed than control subjects (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics.

| Schizophrenia (n=13) | Controls (n=20) | Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 45.7±10.6 | 37.9±9.9 | t=2.157, df=31, p=0.039 |

| M/F | 13/0 | 20/0 | NS |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian/African American/other) | 6 Caucasian, 6 African American, 1 Hispanic | 13 Caucasian, 5 African American, 2 Hispanic | Phi=0.219, p=0.452 |

| Employment status** | 2 of 13 employed | All employed | Phi=.877, p<0.001 |

| Education (years)** | 12.4±1.99 | 15.9±1.86 | t=−4.439, df=26, p<0.001 |

| BPRS baseline scores | |||

| Total** | 30.69±6.36 | 19.05±1.19 | t=8.043, df=31, p<0.001 |

| Positive symptoms** | 8.38±4.11 | 4.05±.22 | t=4.743, df=31, p<0.001 |

| Anxiety baseline* | 1.69±0.79 | 1.28±.60 | t=2.133, df=31, p=0.041 |

| CADSS baseline score* | 1.54±2.70 | 0.10±.31 | t=2.383, df=31, p=0.024 |

| Schizophrenia subtype (DSM-IIIR) | Chronic paranoid—11 | ||

| Chronic undifferentiated—1 | |||

| Chronic disorganized—1 | |||

| Age of onset (years) | 28.75±10.33 | ||

| Antipsychotic medication | Fluphenazine—2 | ||

| Fluphenazine decanoate—2 | |||

| Haloperidol—1 | |||

| Perphenazine—1 | |||

| Risperidone—1 | |||

| Olanzapine—1 | |||

| Unmedicated—3 | |||

| Antipsychotic dose (mg) in chlorpromazine equivalents | 668±686 mg |

*p<0.05, **p<0.001.

Data presented as means±SD.

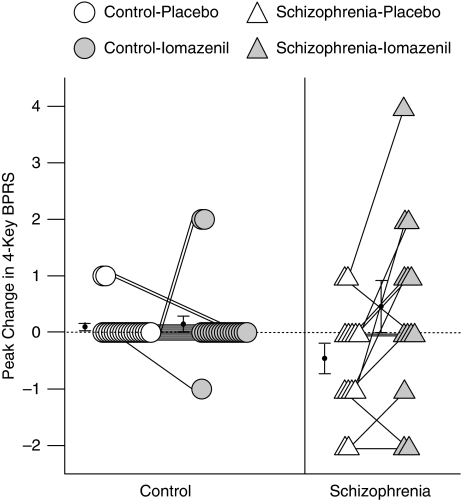

Positive Symptoms

There was a significant main effect of drug (iomazenil vs placebo, F(1,31)=7.26, p=0.011) and drug-by-group interaction (F(1,31)=5.84, p=0.022), but no main effect of group (schizophrenia vs control, F(1,31)=0.20, p=0.66) on peak change in four-key BPRS scores. Although iomazenil did not have any significant effect on four-key BPRS scores in controls (0.1±0.31 for placebo and 0.15±0.67 for iomazenil, F(1,12)=0.09, p=0.77), it produced significant increases in schizophrenia subjects (−0.46±0.97 for placebo and 0.46±1.66 for iomazenil, F(1,12)=6.35, p=0.027, P2=0.35; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Peak change in 4-key BPRS.

Overall Symptoms

There were no significant effects of group (F(1,31)=3.35, p=0.08), drug (F(1,31)=0.87, p=0.36), or drug × group interaction (F(1,31)=0.29, p=0.60) in total BPRS score peak change.

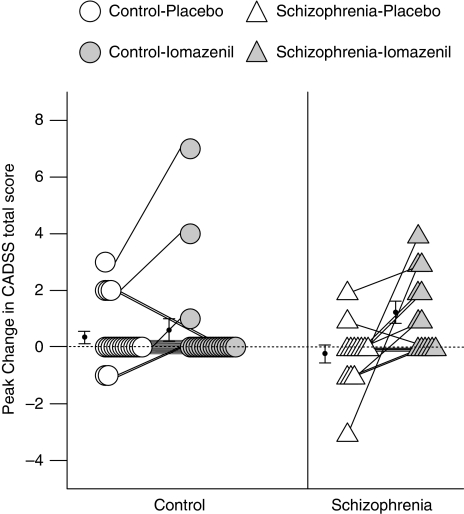

Perceptual Alterations

There was a significant main effect of drug (iomazenil vs placebo, F(1,31)=10.08, p=0.003) and a drug-by-group interaction (F(1,31)=5.05, p=0.032) but no main effect of group (schizophrenia vs control, F(1,31)=0.004, p=0.95) on peak change in CADSS total scores. Although iomazenil did not have any significant effect on peak change in CADSS total scores in controls (0.35±1.04 for placebo and 0.60±1.76 for iomazenil, F(1,12)=0.80, p=0.38), it produced significant increases in schizophrenia subjects (−0.23±1.17 for placebo and 1.23±1.42 for iomazenil, F(1,12)=8.08, p=0.015, ηP2=0.40; Figure 2). There were no significant correlations between the peak change in CADSS and BPRS four-key positive symptom scores for each drug condition.

Figure 2.

Peak change in CADSS total score.

Anxiety

Baseline BPRS anxiety scores were comparable between placebo day and iomazenil day in both schizophrenia (Table 1). There were no significant effects of group (F(1,31)=0.03, p=0.87), drug (F(1,31)=0.73, p=0.40), or drug × group interaction (F(1,31)=0.73, p=0.40) on the peak change of BPRS anxiety subscale.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with the GABA-deficit hypothesis of schizophrenia, iomazenil increased psychotic symptoms and perceptual alterations in schizophrenia patients, but not in controls. The effects of iomazenil were modest; effect size was small (ηP2=0.35). It should be noted that the schizophrenia patients were symptomatically stable and taking D2-receptor antagonists, which could have blunted their response to iomazenil. Furthermore, as GABA deficits likely contribute to a vulnerability to psychosis rather than being intrinsically pro-psychotic, the small effect of iomazenil was not unexpected, and is noteworthy especially as iomazenil did not have any effects in healthy normal subjects. The notion that GABA deficits increase the vulnerability to psychosis is illustrated by the observation that although m-CPP, a partial serotonin 2C, 1A, 1B, and 1D receptor agonist, did not produce psychosis in healthy subjects when administered alone, it did so when administered after iomazenil (D'Souza et al, 2006).

Iomazenil increased psychosis and perceptual alterations in about 50% of schizophrenia patients (Figures 1 and 2), supporting the hypothesis that GABA deficits may be present only in a subgroup. As discussed elsewhere, GABA deficits may increase vulnerability to pro-psychotic drugs. Thus, the hypothesis that only a subgroup of schizophrenia patients have GABA deficits might explain why only a subgroup of schizophrenia patients experience worsened psychosis in response to m-CPP (Iqbal et al, 1991; Krystal et al, 1993), amphetamine (Lieberman et al, 1987), ketamine (Lahti et al, 1995; Malhotra et al, 1997), or Δ9-THC (D'Souza et al, 2005).

The use of iomazenil to interrogate GABA function in schizophrenia is novel. This study has a number of strengths, including a double-blind, placebo-controlled design, and use of well-validated measures. It also has some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, thus confirmatory study with a larger sample size may be necessary. The groups were not matched for treatment with antipsychotic drugs. However, treatment with antipsychotic medications (DA D2 receptor antagonists) would be expected to blunt the response of schizophrenia patients to iomazenil, obscuring group differences rather than enhancing them. Further studies comparing schizophrenia patients on and off antipsychotic medications will need to be conducted. The groups were also not matched by age. However, there is no reason to presume that older subjects show increased response to iomazenil, and a significant response to iomazenil persisted within the schizophrenic group even when age was used as a covariate in the analysis. As only men were studied, because the teratogenic potential of iomazenil is unknown, the results may not generalize to women. Finally, on the basis of other evidence suggesting GABA deficits in schizophrenia (Lewis and Hashimoto, 2007), the study presumes that any differential responses to iomazenil reflect a trait rather than a state. However, this will need to be confirmed by studying the effects of iomazenil in different stages of schizophrenia.

In conclusion, iomazenil exacerbated psychosis in some schizophrenia patients. Identifying patients with GABA deficits is of therapeutic relevance, as a number of drugs can be used to enhance GABA function, such as MK-077, BZs, tiagabine, and vigabatrin. The findings of this small study justify future studies with iomazenil in a larger sample with more proximal measures of GABA function (such as electrophysiological indices of neural synchrony) that might be more sensitive in assessing GABA deficits in schizophrenia. Further studies should also compare schizophrenia patients on and off antipsychotic medications, and compare different stages of schizophrenia to verify that any observed GABA deficits are stable over time.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the critical contributions of the Neurobiological Studies Unit, VA Connecticut Healthcare System including Elizabeth O'Donnell, R.N; Angelina Genovese, R.N; and Robert Sturwold, RPh. We also acknowledge the contributions of John Krystal, MD, for his role in providing the impetus in conducting the study. This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Schizophrenia Biological Research Center.

Roberto Gil, Richard Andrew Sewell, and Kyuengheup Ahn declare that, except for income received from their primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the last 3 years for research or professional service, and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest. John Seibyl receives research support from Eli Lilly, Bristol-Meyer-Squibb, Genentech, Neurologica, Roche, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Seaside, Abbott and Sepracor. John Seibyl holds equity in Molecular Neuroimaging and he also serves as a consultant to GE Healthcare and Bayer Healthcare. Deepak Cyril D'Souza currently receives or has received research support in the last 3 years from Eli Lilly, Organon—Schering Plough, Abbott, Sanofi Aventis, Pfizer, Cephalon, and Astra Zeneca, administered through Yale University School of Medicine.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Gil R, Krystal J, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JP, Bowers M, et al. Increased striatal dopamine transmission in schizophrenia: confirmation in a second cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:761–767. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball S, Busatto GF, David AS, Jones SH, Hemsley DR, Pilowsky LS, et al. Cognitive functioning and GABAA/benzodiazepine receptor binding in schizophrenia: a 123I-iomazenil SPET study. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43:107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer HF, Blauenstein PA, Hasler PH, Delaloye B, Riccabona G, Bangerl I, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of iodine-123-Ro 16-0154: a new imaging agent for SPECT investigations of benzodiazepine receptors. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1007–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM. Emerging principles of altered neural circuitry in schizophrenia. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:251–269. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM, Berretta S. GABAergic interneurons: implications for understanding schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes FM, Vincent SL, Marie A, Khan Y. Up-regulation of GABAA receptor binding on neurons of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Neuroscience. 1996;75:1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Putnam FW, Southwick SM, Marmar C, Charney DS, et al. Measurement of dissociative states with the Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS) J Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:125–136. doi: 10.1023/A:1024465317902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busatto GF, Pilowsky LS, Costa DC, Ell PJ, David AS, Lucey JV, et al. Correlation between reduced in vivo benzodiazepine receptor binding and severity of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:56–63. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charych EI, Liu F, Moss SJ, Brandon NJ. GABA(A) receptors and their associated proteins: implications in the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:481–495. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz DA, Weaver CL, Lovallo EM, Melchitzky DS, Lewis DA. Selective alterations in postsynaptic markers of chandelier cell inputs to cortical pyramidal neurons in subjects with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2112–2124. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza DC, Abi-Saab WM, Madonick S, Forselius-Bielen K, Doersch A, Braley G, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:594–608. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza DC, Gil RB, Zuzarte E, MacDougall LM, Donahue L, Ebersole JS, et al. Gamma-aminobutyric acid-serotonin interactions in healthy men: implications for network models of psychosis and dissociation. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza DC, Perry E, MacDougall L, Ammerman Y, Cooper T, Wu YT, et al. The psychotomimetic effects of intravenous delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy individuals: implications for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1558–1572. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AK, Singer W. Temporal binding and the neural correlates of awareness. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:16–25. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Mohler H. GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol. 1995;359:154–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Volk DW, Eggan SM, Mirnics K, Pierri JN, Sun Z, et al. Gene expression deficits in a subclass of GABA neurons in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6315–6326. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunkeler W, Mohler H, Pieri L, Polc P, Bonetti EP, Cumin R, et al. Selective antagonists of benzodiazepines. Nature. 1981;290:514–516. doi: 10.1038/290514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impagnatiello F, Guidotti AR, Pesold C, Dwivedi Y, Caruncho H, Pisu MG, et al. A decrease of reelin expression as a putative vulnerability factor in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15718–15723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal N, Asnis GM, Wetzler S, Kahn RS, Kay SR, van Praag HM. The MCPP challenge test in schizophrenia: hormonal and behavioral responses. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;30:770–778. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90233-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EW, Woods SW, Zoghbi S, McBride BJ, Baldwin RM, Innis RB. Receptor binding characterization of the benzodiazepine radioligand 125I-Ro16-0154: potential probe for SPECT brain imaging. Life Sci. 1990;47:1535–1546. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90182-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humansPsychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Seibyl JP, Price LH, Woods SW, Heninger GR, Aghajanian GK, et al. m-Chlorophenylpiperazine effects in neuroleptic-free schizophrenic patients. Evidence implicating serotonergic systems in the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:624–635. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820200034004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti AC, Koffel B, LaPorte D, Tamminga CA. Subanesthetic doses of ketamine stimulate psychosis in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;13:9–19. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00131-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, Gil R, Kegeles L, Innis R. Increased dopamine transmission in schizophrenia: relationship to illness phases. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:56–72. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, Gil R, D'Souza CD, Erdos J, et al. Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9235–9240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T. Deciphering the disease process of schizophrenia: the contribution of cortical gaba neurons. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:109–131. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:312–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Kane JM, Sarantakos S, Gadaleta D, Woerner M, Alvir J, et al. Prediction of relapse in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK, Pinals DA, Adler CM, Elman I, Clifton A, Pickar D, et al. Ketamine-induced exacerbation of psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairment in neuroleptic-free schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:141–150. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BL, Arnsten AF, Goldman-Rakic PS, Roth RH. Increased dopamine turnover in the prefrontal cortex impairs spatial working memory performance in rats and monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1325–1329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma T, Augood SJ, Arai H, McKenna PJ, Emson PC. Measurement of GABAergic parameters in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: focus on GABA content, GABA(A) receptor alpha-1 subunit messenger RNA and human GABA transporter-1 (HGAT-1) messenger RNA expression. Neuroscience. 1999;93:441–448. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. Brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:815–850. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche Iomazenil data on file

- Schroder J, Bubeck B, Demisch S, Sauer H. Benzodiazepine receptor distribution and diazepam binding in schizophrenia: an exploratory study. Psychiatry Res. 1997;68:125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(96)02843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubiger P, Hasler P.1989Iomazenil and other brain receptor tracers for SPECTIn: SPaHP (ed).Proceedings of the sixth Bottstein Colloquium. Wurenlingen/Villigen: Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- Singer W. Neuronal synchrony: a versatile code for the definition of relations. Neuron. 1999;24:49–65. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80821-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer W, Gray CM. Visual feature integration and the temporal correlation hypothesis. Annu Rev of Neurosci. 1995;18:555–586. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallman JF, Gallager DW. The GABA-ergic system: a locus of benzodiazepine action. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1985;8:21–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.08.030185.000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallon-Baudry C. Oscillatory synchrony and human visual cognition. J Physiol Paris. 2003;97:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:100–113. doi: 10.1038/nrn2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela F, Lachaux JP, Rodriguez E, Martinerie J. The brainweb: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:229–239. doi: 10.1038/35067550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela FJ. Resonant cell assemblies: a new approach to cognitive functions and neuronal synchrony. Biol Res. 1995;28:81–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff NP, Soares JC, D'Souza CD, Gil R, Degen K, Abi-Dargham A, et al. [123I]Iomazenil SPECT benzodiazepine receptor imaging in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1999;91:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(99)00027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Austin MC, Pierri JN, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Decreased glutamic acid decarboxylase67 messenger RNA expression in a subset of prefrontal cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons in subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:237–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Lewis DA. Impaired prefrontal inhibition in schizophrenia: relevance for cognitive dysfunction. Physiol Behav. 2002;77:501–505. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00936-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Pierri JN, Fritschy JM, Auh S, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Reciprocal alterations in pre- and postsynaptic inhibitory markers at chandelier cell inputs to pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:1063–1070. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.10.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldvogel HJ, Baer K, Gai WP, Gilbert RT, Rees MI, Mohler H, et al. Differential localization of GABAA receptor subunits within the substantia nigra of the human brain: an immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:912–929. doi: 10.1002/cne.21573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerner MG, Mannuzza S, Kane JM. Anchoring the BPRS: an aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkowitz OM, Pickar D. Benzodiazepines in the treatment of schizophrenia: a review and reappraisal. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:714–726. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo TU, Whitehead RE, Melchitzky DS, Lewis DA. A subclass of prefrontal gamma-aminobutyric acid axon terminals are selectively altered in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5341–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Maddock RJ, Rokem A, Silver MA, Minzenberg MJ, Ragland JD, et al. GABA concentration is reduced in visual cortex in schizophrenia and correlates with orientation-specific surround suppression. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3777–3781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6158-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]