Abstract

Ribosomal protein L4 resides near the peptidyl transferase center of the bacterial ribosome and may, together with rRNA and proteins L2 and L3, actively participate in the catalysis of peptide bond formation. Escherichia coli L4 is also an autogenous feedback regulator of transcription and translation of the 11 gene S10 operon. The crystal structure of L4 from Thermotoga maritima at 1.7 Å resolution shows the protein with an alternating α/β fold and a large disordered loop region. Two separate binding sites for RNA are discernible. The N–terminal site, responsible for binding to rRNA, consists of the disordered loop with flanking α–helices. The C–terminal site, a prime candidate for the interaction with the leader sequence of the S10 mRNA, involves two non-consecutive α–helices. The structure also suggests a C–terminal protein-binding interface, through which L4 could be interacting with protein components of the transcriptional and/or translational machineries.

Keywords: feedback regulation of transcription and translation/ribosomal protein L4/rRNA- and mRNA-binding proteins/S10 operon/X-ray crystallography

Introduction

Ribosomes are large, abundant ribonucleoprotein complexes, functioning as the universal protein synthesis machineries in all three kingdoms of life. The best studied prokaryotic 70S ribosome from Escherichia coli is comprised of 54 proteins and three RNA molecules. It can be divided into two subunits, which are designated 50S [33 ribosomal (r-) proteins, 23S rRNA and 5S rRNA] and 30S (21 r–proteins and 16S rRNA). For a detailed understanding of the function of these large assemblies, structural information is clearly vital. In a divide and conquer approach, the high resolution structures of several fragments of rRNA and of 17 r–proteins have been determined by X-ray crystallography and NMR (for reviews, see Liljas and Garber, 1995; Liljas and Al–Karadaghi, 1997; Moore, 1998; Ramakrishnan and White, 1998; Draper and Reynaldo, 1999). Recently, the first structure of an rRNA–r–protein complex has been solved (Conn et al., 1999; Wimberly et al., 1999). X-ray crystallography is now reaching the point where all these components can be fitted into intermediate resolution electron density maps of entire 50S and 30S subunits (Ban et al., 1999; Clemons et al., 1999; Tocilj et al., 1999). In the foreseeable future, the crystal structure of a 70S ribosome may also approach atomic resolution (Cate et al., 1999).

The key ribosomal activity, the peptidyl transferase, is believed to reside largely in the rRNA, whose structure and active conformation are presumably stabilized by the r–proteins (Dahlberg, 1989). However, a small subset of r–proteins, i.e. L2, L3 and L4, is intimately involved with the peptidyl transferase RNA region and may participate actively in the catalysis of peptide bond formation (Hampl et al., 1981; Schulze and Nierhaus, 1982). L2, L3 and L4 are all primary binding r–proteins, which associate with defined sites on the 23S rRNA without the assistance of other proteins. L4 in particular is known to play a crucial role in the early assembly of the large subunit (Nierhaus, 1991). It presumably fixes the tertiary structure of a portion of 23S rRNA by cross-linking segments that are distant in primary sequence (Maly et al., 1980; Gulle et al., 1988).

In prokaryotes, r–proteins are grouped into conserved operons. For E.coli, it has been found that the r–protein expression levels are often regulated autogenously by one member of the translational units (Nomura et al., 1980; Draper, 1989; Zengel and Lindahl, 1994). The feedback controls usually occur at the level of translation, through the binding of the regulatory r–protein to a specific site on the operon mRNA. The mRNA-binding sites often show structural and sequence homologies to the attachment sites of the regulatory proteins on the rRNA (Nomura et al., 1980; Draper, 1989; Zengel and Lindahl, 1994), as demonstrated for L1 (Draper, 1989), the (L12)4–L10 complex (Johnsen et al., 1982) and S8 (Cerreti et al., 1988), which control the L11, L10 and spc operons, respectively. L4 was the first protein shown to inhibit not only the translation but also the transcription of its S10 operon (Yates and Nomura, 1980; Zengel et al., 1980). This regulatory unit contains 11 r–proteins, including all those implicated in the peptidyl transferase activity (Schulze and Nierhaus, 1982; Nierhaus, 1991). Transcriptional control is achieved via an intricate attenuation mechanism, in which L4 may interact with the mRNA, transcription factor NusA and/or RNA polymerase (Zengel and Lindahl, 1994). Escherichia coli L4 seems to exhibit separate rRNA- (N–terminal) and mRNA- (C–terminal) binding modules (Li et al., 1996), consistent with the differences in sequence and predicted structure of the mRNA and rRNA regions that interact with the protein (Maly et al., 1980; Gulle et al., 1988; Zengel and Lindahl, 1996).

The central architectural and functional roles of L4 in the ribosome and its unique extraribosomal functions primed our interest in a structural investigation. Here we present the 1.7 Å crystal structure of r–protein L4 from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima (TmaL4).

Results

Structure determination and quality of the model

For the structure solution of TmaL4, a conventional heavy atom search was performed, yielding three derivatives (Table I). A solvent-flattened map, using phases obtained from the isomorphous and anomalous heavy atom differences, showed well defined density for the majority of the polypeptide main chain and most side chains (Figure 2B; for phasing statistics, see Table II). No electron density was observed for the internal region between residues 43 and 96, which has been omitted from the final model. A flexible loop between amino acids 186 and 191 showed weaker main chain density than the remainder of the structure. Parts of this region have been held at zero occupancy during the refinement. The experimental map was used as the main guide in model building to avoid bias. The final model included 172 amino acids, representing 73% of the whole protein, 213 water oxygens and one citrate molecule. The final R- and Rfree-values were 20.8 and 23.7%, respectively (Table III), with a mean positional error of 0.23 Å (Luzzati, 1952). A total of 92.7% of the residues occupied the most favored φ/ψ regions; the rest of the molecule was in additionally allowed areas. All active protein and solvent atoms were enveloped by the final 2Fo–Fc map at the 1σ level (Figure 2B), while no residual features above 3σ were seen in the final Fo – Fc difference maps.

Table I. Data collection statistics.

| Dataset | Resolution (Å) | Completeness (%)a | Rmerge (%)b | I/σI | Concentration of metal (mM) | Time of soak | No. of sites | Stabilizing buffer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native (RT) | 2.50 | 92.8 (93.8) | 6.0 (21.7) | 15.5 (3.5) | – | – | – | – |

| Native (cryo) | 1.70 | 92.8 (88.0) | 5.4 (34.4) | 25.9 (3.9) | – | – | – | – |

| UO2OAc2 (RT) | 3.33 | 85.6 (88.8) | 9.8 (24.2) | 9.1 (3.8) | 14 | 33 h | 2 | citrate |

| UO2OAc2 (cryo) | 2.50 | 75.9 (75.0) | 6.5 (35.3) | 12.8 (3.1) | 14 | 13 days | 2 | citrate |

| K3UO2F5 (RT) | 3.90 | 76.0 (75.3) | 14.0 (39.8) | 6.8 (2.7) | 12 | 13 days | 1 | citrate |

| K3IrCl6 (RT) | 3.05 | 98.9 (92.2) | 15.0 (49.1) | 6.9 (2.9) | 8 | 36 h | 2 | HEPES |

| K3IrCl6 (cryo) | 1.70 | 97.8 (74.2) | 5.6 (32.6) | 23.8 (2.8) | 8 | 36 h | 1 | HEPES |

aValues in parentheses are statistics for the highest resolution shell (1.73–1.70 Å).

bRmerge = Σ∣Ii – <I>∣/ΣI, in which Ii is an individual intensity measurement and <I> is the averaged intensity for this reflection.

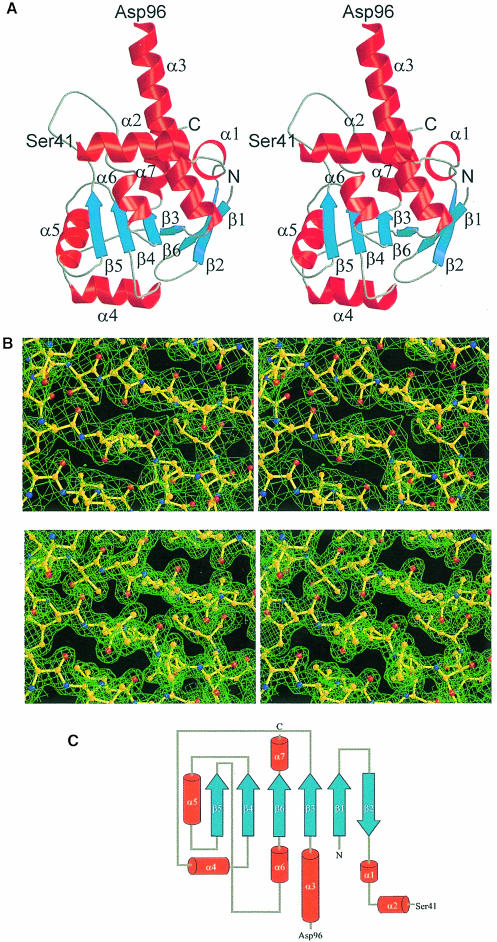

Fig. 2. (A) Stereo ribbon diagram of TmaL4 showing the overall fold. The secondary structural elements are labeled according to Figure 1A. Unless indicated otherwise, figures were produced with MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis, 1991) and rendered with Raster3D (Merritt and Bacon, 1997). (B) A stereo view of a portion of the electron density around the four-stranded central β-sheet in the C–terminus of the protein. The top part shows the solvent-flattened MIRAS map calculated at 2.5 Å contoured at 0.8σ. The bottom part displays the final 2Fo – Fc map at 1.7 Å contoured at 1.4σ. (C) Topology diagram of TmaL4. Color coding is the same as in (A).

Table II. Phasing statistics.

| Dataset | Phasing powera |

RCullisb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iso.c | Ano.c | Iso. | Ano. | |

| UO2OAc2 (RT)d | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.78 | 0.90 |

| UO2OAc2 (cryo) | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.82 | 0.86 |

| K3UO2F5 (RT) | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| K3IrCl6 (RT) | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.74 | 0.84 |

| K3IrCl6 (cryo) | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

aPhasing power = [Σ∣FH∣2/ΣE∣2]1/2 in which E is the lack of closure with Σ∣E∣2 = Σ{∣FPH∣(obs) – ∣FPH∣(calc)}2

bRCullis = Σ∥(FPH ± FP) – FH(calc)∣/Σ∣FPH ± FP∣FP, FPH and FH are the structure factors for the native protein, the derivative and the heavy atom, respectively.

cIso is isomorphous and ano is anomalous.

dRT = room temperature.

Table III. Statistics of the final model.

| Resolution range (Å) | 8.0–1.7 |

|---|---|

| Sigma cut-off | 2.0 |

| No. of reflections used in refinement | 22 806 |

| Percentage of reflections used to calculate Rfree | 5.0 |

| Completeness of data in resolution range | 92.9 |

| No. of protein atoms | 1398 |

| No. of water molecules | 213 |

| No. of citrate molecules | 1 |

| R-factor (%)a | 20.8 |

| Free R-factor (%)b | 23.7 |

| R.m.s. deviations from ideal stereochemistry | |

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 |

| bond angles (°) | 1.51 |

| dihedrals (°) | 22.7 |

| impropers (°) | 0.98 |

| Mean B-factor for main chain (Å3) | 23.6 |

| R.m.s. deviation in main chain B-factor (Å3) | 1.5 |

| Mean B-factor for side chains (Å3) | 28.6 |

| R.m.s. deviation in side chain B-factors (Å3) | 2.8 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| residues in most favored regions (%) | 92.7 |

| residues in additionally allowed regions (%) | 7.3 |

aR-factor = {Σ∥Fobs∣ – k∣Fcalc∥}/Σ∣Fobs∣

bFree R-factor = {ΣT∥Fobs∣ – k∣Fcalc∥}/ΣT∣Fobs∣, in which T is the test set.

Overall structure

With an Mr of 26630, TmaL4 belongs to the largest ribosomal proteins. The portion of TmaL4 defined by the electron density has dimensions of ∼50 × 33 × 30 Å and shows an α/β fold with an open β-sheet topology (Figure 2A). Despite its various functional roles, which can be mapped to different areas of the protein (Li et al., 1996), TmaL4 consists of just one domain. Such organization is in contrast to the general observation of multiple domains in other large r–proteins. The sequential order of secondary structural elements is given in Figure 2C. Seven α–helices are positioned around a mainly parallel, six-stranded β-sheet. All helices are partly solvent exposed and therefore bipathic, with their hydrophobic side chains all pointing to the protein interior. Thus, TmaL4 exhibits a well defined, conserved and extended hydrophobic core, which stabilizes the overall structure. The center of the core is built up by four parallel strands, β3–β6 (see below). The first two strands, β1 and β2, are at the periphery of the protein and create a β-hairpin, which is connected by only two hydrogen bonds to the core portion of the sheet. The bulk of the β-hairpin is oriented almost perpendicular to the plane of the remaining sheet.

A quite remarkable feature of the structure is a 55 residue stretch (Ser41–Asp96) between helix α2 and the long, bent helix α3, lacking electron density (Figure 2A). Interestingly, the program PHDsec (Rost and Sander, 1993) predicts mainly loop regions for this area of the protein. It is noteworthy that the remainder of the TmaL4 fold is predicted correctly (Figure 1A). Crystals of TmaL4 contain full-length protein, as seen from SDS–PAGE analysis of dissolved specimens (data not shown). Analysis of circular dichroism (CD) spectra of TmaL4 by the self-consistent method (Sreerama and Woody, 1993) suggests 36% α-helix, 13% β-sheet and 25% turns, in excellent agreement with the fractions of secondary structural elements derived from the crystal structure (34.5% α-helix, 12.8% β-sheet and 13.6% turns assuming that the 41–96 region is disordered). A void seen in the crystal packing could accommodate the unobserved part of the molecule in a folded conformation. All these observations suggest that a large portion of TmaL4 is internally disordered and not tethered in a folded conformation via flexible hinges to the remainder of the protein.

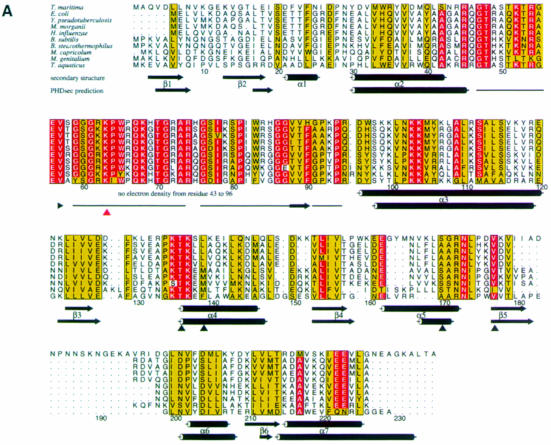

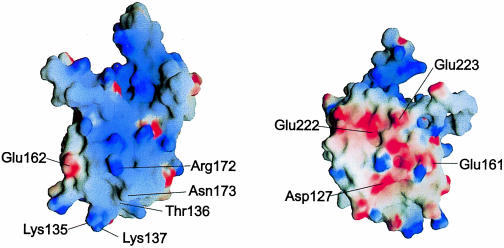

Fig. 1. (A) Alignment of representative L4 sequences from different bacteria. The species are as follows: Thermotoga maritima (Nelson et al., 1999); Escherichia coli (Zurawski and Zurawski, 1985); Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (Gross et al., 1989); Morganella morganii (Zengel et al., 1995); Haemophilus influenzae (Fleischmann et al., 1995); Bacillus subtilis (Yasumoto et al., 1996); Bacillus stearothermophilus (Herwig et al., 1992); Mycoplasma capricolum (Ohkubo et al., 1987); Mycoplasma genitalium (Fraser et al., 1995); and Thermus aquaticus (Pfeiffer et al., 1995). The alignment was performed using PILEUP [Wisconsin Package Version 9.0, Genetics Computer Group (GCG), Madison, WI] and drawn with the program ALSCRIPT (Barton, 1993). The numbering corresponds to TmaL4. The background of amino acids strictly conserved in at least nine out of 10 species is colored red. Residues with conservation values >5 in at least nine sequences are drawn with a yellow background (Livingstone and Barton, 1993). The secondary structures as determined by the program STRIDE (Frishman and Argos, 1995) and the corresponding PHDsec secondary structure predictions (Rost and Sander, 1993) are also given. Predicted coil regions (horizontal line) are shown just from amino acids 43–96. Residues evaluated as important for the regulatory functions of TmaL4 (Li et al., 1996) are indicated by black triangles, whereas the site conferring erythromycin resistance in the case of mutation (Chittum and Champney, 1994) is indicated with a red triangle. (B) Sequence alignment of L4 proteins from the three kingdoms of life. The following species were used: Thermotoga maritima (Nelson et al., 1999); Escherichia coli (Zurawski and Zurawski, 1985); Rattus norvegicus (Chan et al., 1995); Homo sapiens (Bagni et al., 1993); Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (Smith et al., 1997); Methanococcus jannaschii (Bult et al., 1996); and Haloarcula marismortui (Arndt et al., 1990). The area of the extra loop of TmaL4 and the corresponding sequences from the other proteins is boxed. The color coding is the same as in (A). The C–terminal extension of ∼180 amino acids, which is typical for eukaryotic L4 proteins, is omitted from the alignment.

The C–terminal two-thirds of the ordered L4 part, which directly follow the disordered region, form a four-stranded parallel β-sheet, surrounded by five α–helices (Figure 2A). Helices α6 and α7 run almost perpendicular to the plane of the sheet and to the axis of helix α5, with α7 packing partly against α3. Interspersed between strand β5 and helix α6, TmaL4 displays a flexible loop of 20 mainly basic amino acids. While this loop is unique to T.maritima L4 among the bacteria, there is an analogous structure in the archaea (Figure 1B).

Identification of functional sites

Structural data together with the wealth of known primary sequences of r–proteins allow the mapping of conserved patterns on the surfaces of the molecules and therefore the identification of functionally relevant sites, e.g. possible RNA-binding interfaces (Davies et al., 1998). Crystal structures of r–proteins and of RNA–protein complexes show that interaction with RNA is likely to occur through basic residues, contacting the sugar phosphate backbone, or through aromatic residues, participating in stacking interactions with the RNA bases (Oubridge et al., 1994; Liljas and Al-Karadaghi, 1997; Ramakrishnan and White, 1998; Draper and Reynaldo, 1999).

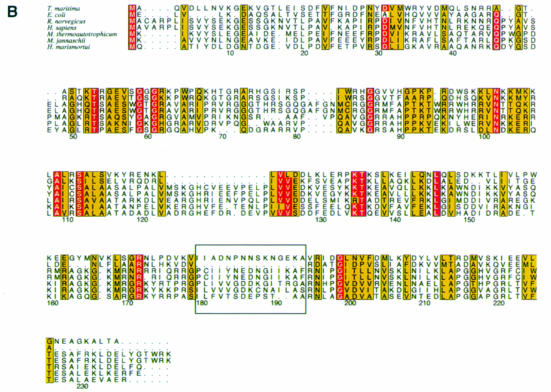

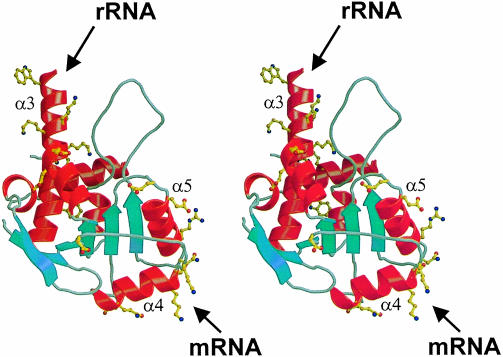

Investigating the surface of TmaL4, a prominent asymmetry in the electrostatic potential becomes apparent (Figure 3). One side of the molecule is highly positively charged and seems predestined to bind RNA. It is comprised of parts of helix α3 (Lys99, Lys103, Lys104, Lys106 and Lys107), the N–terminus of α4 (Lys135, Lys137 and Thr136), the solvent-exposed areas of α5 (Lys160, Lys168, Leu169, Arg172 and Asn173) and some residues of α6 (Lys207 and Phe203) and β5 (Lys178). Sequence alignments reveal (Figure 1A) that Lys178 and the residues contributed by helix α6 are highly variable, whereas most of the other amino acids are conserved. Guided by these conserved residues, the putative RNA interaction surface can be subdivided into two spatially separated regions (Figure 5). The first is made up mainly of the N–terminal part of helix α3. It is preceded by the 55 residue disordered loop, which is the most conserved portion in prokaryotic L4 proteins and displays many basic residues (Figure 1A). The loop may therefore be the central element of this RNA-binding patch. The second putative RNA interaction site consists of the area around the two helices, α4 and α5, arranged almost perpendicular to each other (Figure 5). Interestingly, the spatial separation of the two putative RNA-binding sites coincides with mutational analyses, which attribute different RNAbinding functions to the two L4 areas in the E.coli protein (Li et al., 1996): while the first region (helix α3 and the 43–96 loop) seems to mediate the binding to rRNA, the second portion of the molecule (helices α4 and α5) is implicated in the binding to mRNA.

Fig. 3. Surface electrostatic potential of TmaL4. The figure on the left shows the putative RNA-binding surface. The positions of important and conserved surface residues are indicated. The figure on the right corresponds to the probable protein-binding site on the opposite side of the molecule. The potentials were calculated with the program GRASP (Nicholls et al., 1991).

Fig. 5. Stereo view of TmaL4. Conserved residues are shown in ball-and-stick representation. The spatial separation of the different functional sites is clearly seen. The long helix α3 (top) and helix α2 (behind α3, in the background) harbor some of the amino acids implicated in interactions with rRNA. The probable mRNA-binding part of the molecule in the C–terminus is located in helices α4 and α5 (bottom, on the right side of the molecule). In the foreground, some conserved residues belonging to the putative protein-binding site are seen.

Opposite the putative RNA interaction face, TmaL4 exhibits a flank of predominantly electronegative surface potential (Figure 3). Here many conserved residues (Asp127, Glu161, Glu162, Glu222 and Glu223) are found interspersed among non-conserved acidic side chains (Asp128 and Asp216). The side chain of Glu222 interacts with the main chain amide of Ser20 (distance 2.74 Å), but Asp127, Glu161 and Glu223 are not involved in interactions with other residues. Because of its highly electronegative potential, this side of L4 is unlikely to associate with RNA. It is therefore a prime candidate for an interaction site with other proteins, e.g. of the ribosome or of the transcriptional attenuation complex.

Structural similarities to other proteins

Ribosomes are thought to be of ancient origin (Draper and Reynaldo, 1999) and r–proteins may therefore represent structural prototypes for the recognition of nucleic acids. Indeed, some r–proteins were found to be structurally homologous to known RNA- and DNA-binding motifs. For example, three conserved α–helices in L11 superimpose quite well on the corresponding parts of a helix–turn–helix motif in homeodomain DNA-binding proteins (Xing et al., 1997; Draper and Reynaldo, 1999), and the two domains of r–protein L2 were found to be similar to SH3-barrel and OB-fold proteins, respectively (Nakagawa et al., 1999).

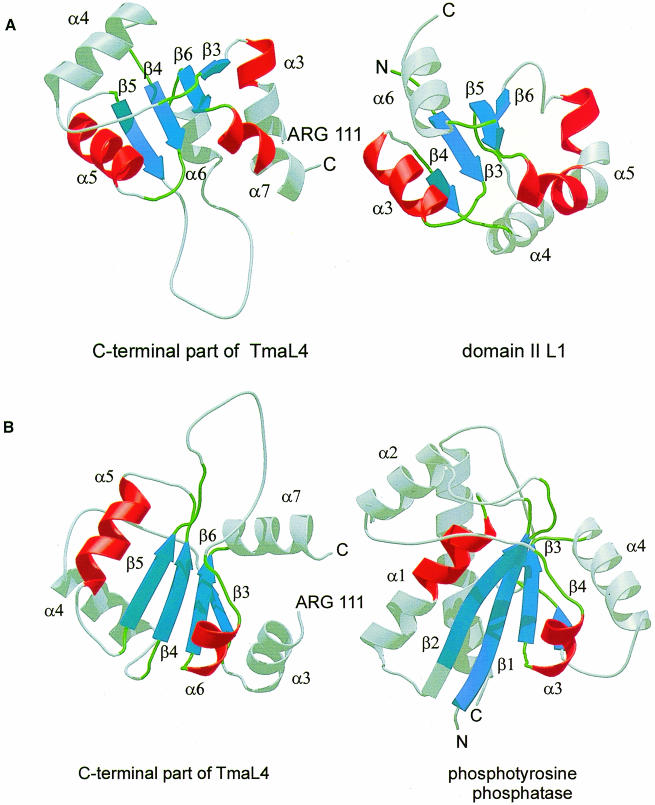

In the present case, searches for structurally homologous proteins with the DALI-server (Holm and Sander, 1993) and the database SCOP (Murzin et al., 1995) resulted in numerous hits, mainly including proteins with mononucleotide-binding motifs. However, all identified proteins were much larger than L4 and, therefore, it was quite difficult to assess the relevance of these comparisons. A subsequent manual search showed that domain II of r–protein L1 (Nikonov et al., 1996) and a low molecular weight phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase (PTPase) (Su et al., 1994) are homologous to the C–terminus of L4 (Figure 4). As in the case of the larger proteins, the best alignments were found for the four-stranded parallel β-sheet and for helices α5 and α6 of TmaL4. The root-mean-square (r.m.s.) distances for the Cα atoms of the superimposed secondary structural elements were 2.3 Å for domain II of L1 (47 matching residues) and 2.0 Å for PTPase (56 matching residues). The parts of the molecule that had a different orientation still showed topological conservation, e.g. TmaL4 helix α4 is comparable to helix α6 in L1 and to the longer helix α5 in PTPase (Figure 4A and B).

Fig. 4. (A) Comparison of the C–terminus of TmaL4 (left) with domain II of r–protein L1 (right; Nikonov et al., 1996). Corresponding parts are in the same color. (B) Ribbon diagrams showing the C–terminus of TmaL4 and phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase (Su et al., 1994). Secondary structural elements that could be aligned again are in the same color.

Discussion

TmaL4 as a structural prototype of L4 r–proteins

While a plethora of biochemical and molecular biological information is available for the E.coli ribosome and its components, the mesophilic r–proteins are difficult to crystallize. With structural work concentrating on less well characterized thermophilic organisms, it has to be ascertained that these molecules are not only structural but also functional homologues of their E.coli counterparts. Because of a high degree of sequence identity (42%) between T.maritima and E.coli L4, it is likely that these proteins fold into the same three-dimensional structure. Indeed, L4 proteins from different bacterial species were proven to be interchangeable during the assembly of the ribosome, e.g. Bacillus stearothermophilus L4 can be incorporated in vivo into E.coli ribosomes (L.Lindahl and J.M.Zengel, unpublished results) and E.coli L4 can assemble into Vibrio cholerae ribosomes (T.Allen, L.Lindahl and J.M.Zengel, unpublished results). However, recent data draw a complicated picture regarding the evolution of the extraribosomal regulatory functions of L4 (Allen et al., 1999).

In controlling both the transcription and translation of the 11 gene S10 operon in E.coli, the L4-mediated feedback control is fundamentally different from that of other autoregulatory r–proteins. It was shown that RNA polymerase can pause briefly at a terminator hairpin in the S10 mRNA leader sequence, supported by transcription factor NusA (Zengel and Lindahl, 1990). This ternary pre–termination complex can be stabilized further by L4, resulting in premature termination of transcription (attenuation; Zengel and Lindahl, 1994). The mechanism of translation regulation is not well studied, but seems to be mediated via a switching of the mRNA into an untranslatable conformation upon binding of L4 (Shen et al., 1988). It has been shown that specific secondary structure elements in the S10 leader sequence are necessary for the transcriptional control through L4 (Zengel and Lindahl, 1990). It is noteworthy that not all investigated bacterial species display these elements in their leader sequences, and indeed only some S10 leaders from the gamma subdivision of the enterobacteria mediate L4 feedback control in E.coli (Allen et al., 1999). The latter observation is in contrast to the finding that numerous foreign L4 proteins, also from more distantly related species such as B.stearothermophilus (42% sequence identity to E.coli), were shown to control both transcription and translation of the S10 operon in E.coli (Zengel et al., 1995). It seems that the protein component (L4) of the E.coli S10 autoregulatory mechanisms has evolved and been conserved through an unrelated evolutionary pressure (see below), while the mRNA component (S10 leader) has been constructed subsequently in a subset of species. For example Pseudomonas aeruginosa L4 can control the S10 operon in E.coli but displays no regulatory elements in its S10 leader sequence (Allen et al., 1999; T.Allen, L.Lindahl and J.M.Zengel, unpublished results). We therefore feel confident in discussing both the L4 ribosomal and regulatory functions as known from E.coli based on the present structure.

Both E.coli and T.maritima L4 exhibit weak primary sequence identities to the archaeal analogues (24 and 28%, respectively, to Haloarcula marismortui L4), with subtle similarities spread over the entire polypeptides (Figure 1B). Moreover, TmaL4 contains a flexible loop between residues 183 and 194, which is unique among known bacterial L4 proteins but aligns with the archaeal and eukaryotic variants (Figure 1B). In this context, it is noteworthy that the complete sequencing of the T.maritmia genome revealed an unusually high similarity to those of archaea (Nelson et al., 1999). The extra loop of TmaL4 is perhaps a faint indicator of this observation. Despite the rather weak sequence identities, structural homology is suggested by the equivalent positioning of the L4 genes within the corresponding operons in bacteria and archaea (Sanangelantoni et al., 1994). It is possible therefore that the structure of TmaL4 will prove relevant for the rapidly proceeding crystallographic analysis of the 50S subunit from the archaeon H.marismortui.

rRNA binding through a highly flexible extended loop region

RNA–protein cross-linking experiments in 50S subunits identified possible interaction sites of L4 with rRNA, which are located exclusively in helix α2 and the subsequent long disordered loop (Moller and Brimacombe, 1975; Maly et al., 1980; Thiede et al., 1998). A mutational analysis (Li et al., 1996) confirmed the interpretation of these cross-links and showed, in addition, that deletion of residues 89–106 in helix α3 inhibited incorporation of L4 into the ribosome. In contrast, the C–terminal 120 amino acids so far have not been implicated in rRNA binding. According to the present structure, the main rRNA-binding site of L4 therefore consists of a 55 residue loop flanked by helices α2 and α3, i.e. an area that exhibits the highest degree of phylogenetic conservation and seems to be largely disordered. The expected RNA recognition mode consequently differs from the often observed scaffolding of RNA- (and DNA-) binding regions into secondary structure patterns, as seen, for example, in the RNA recognition motif (Oubridge et al., 1994), helix–turn–helix modules (Brennan et al., 1990; Albright and Matthews, 1998) or zinc fingers (Pavletich and Pabo, 1991; Chan et al., 1993). Indeed, flexible loops that can be cross-linked to rRNA are found frequently in r–proteins (Urlaub et al., 1995) but they are normally smaller than observed here. It is likely that the disordered loop will become structured upon binding to rRNA, as observed in the C–terminal domain of r–protein L11 with a 15 residue unstructured loop, which is clearly seen in the complex with RNA (Markus et al., 1997). Frequently r–proteins have extended flexible C- or N–termini, which are thought to become stabilized by binding to RNA or other protein components in the ribosome (Liljas, 1991), such as the first 41 residues in S4 (Davies et al., 1998).

L4 interacts with 23S rRNA segments, which are very distant in primary sequence. They were mapped to a region of 110 nucleotides in domain I of 23S rRNA, presumably folded into a pseudoknot, and a small putative stem–loop in domain II (Maly et al., 1980; Gulle et al., 1988). A Lys63→Glu mutation (Lys58→Glu in E.coli, red arrow in Figure 1A) in the large disordered loop was shown to affect the overall folding of 23S rRNA in domains II and V (Gregory and Dahlberg, 1999). The mutation also results in erythromycin-resistant ribosomes (Chittum and Champney, 1994). This macrolide antibiotic is known to also interact with r–proteins L22, L15, L16 and L2, and with 23S rRNA. It can interfere with the elongation step of protein synthesis and inhibits the assembly of the large subunit (Chittum and Champney, 1994, 1995). The suggested interaction of erythromycin with L4 on the one hand, and its major effects on the subunit assembly on the other, also suggest L4 as an important player in the maintenance of ribosome structure.

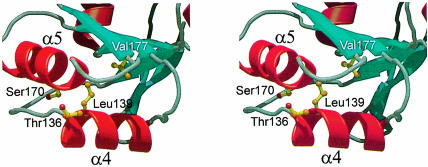

A separate putative mRNA-binding site

Mutation and deletion experiments have identified a number of L4 variants defective in transcriptional feedback regulation, but still able to assemble into the ribosome (Li et al., 1996). All the alterations are located exclusively in the C–terminal portion of the protein (see the black triangles in Figure 1A). Four individual point mutations effecting the above phenotype were found: Thr136→Ile, Leu139→Pro, Ser170→Val and Val177→Asp (numbering according to the TmaL4 sequence). All these mutations are in or near the two helices α4 and α5 (Figure 6). Leu139 and Val177 are pointing towards the protein interior, being part of the hydrophobic core. Because the Leu139→Pro and Val177→Asp alterations reduce the hydrophobicity of the core, it seems likely that they weaken the overall stability of this area of the protein and influence the spatial alignment of the two helices. Although in the present case the side chain of Ser170 forms a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl oxygen of Asn166, providing extra stability to helix α5, it is interchangeable with Ala in some bacterial L4 proteins (Figure 1A). Thr136 is the only strictly conserved amino acid among the four mutated. It protrudes from helix α4 and is a prime candidate for interaction with the mRNA. It is worthwhile mentioning that all mutations were isolated via random mutation procedures. The crystal structure gives new hints as to where specific point mutations could now be introduced in order to define further the mRNA-binding capabilities of L4. Major candidates would be conserved residues such as Lys135, Lys137 and Asn173.

Fig. 6. Stereo ribbon plot of the regulative part of the molecule encompassing helices α4 and α5. The four amino acids known to be essential for regulation (Li et al., 1996) are drawn in ball-and-stick representation. Leu139 and Val177 are pointing inwards to the hydrophobic core of TmaL4. The side chain of Ser170 stabilizes helix α5, and Thr136 (in the foreground) protrudes from the molecule.

Specific regions in the mRNA are necessary for L4 regulatory control (Zengel and Lindahl, 1990), implying a direct binding of L4 to the S10 mRNA. Such direct interaction would also limit the effects of L4 to its own operon. The question arises as to how L4 recognizes its specific mRNA sites. The recent 5 Å map of the 50S subunit of H.marismortui revealed that many α–helical segments of r–proteins are interacting with the major and minor grooves of duplex RNA (Ban et al., 1999). Similarly, the two L4 helices, α4 and α5, could bind to one or both of the stem–loop structures in the S10 leader sequence, which were identified as putative interaction partners (Zengel and Lindahl, 1996). Alternatively, bulges and hairpins, as present in the current mRNA structures, have been shown to modulate groove widths of double helices to allow readout by cognate proteins (Battiste et al., 1996; Legault et al., 1998; Conn et al., 1999).

Although no binding of the L4 C–terminus to rRNA was observed, it was shown that E.coli L4 bound to domain I of 23S rRNA is inactive in regulating the transcription of the S10 operon (Zengel and Lindahl, 1993). Therefore, the possibility exists that the two helices also represent a minor site for interaction with 23S rRNA and become masked upon incorporation of L4 into the ribosome. Indeed, two putative rRNA-binding sites have previously been found in L14 (Davies et al., 1996) and L9 (Hoffman et al., 1994). The rRNA interaction sites of L14 in particular show a hierarchical order with a more extensive primary RNA-binding site and a more compact secondary site (Davies et al., 1996). If, by analogy, helices α4 and α5 of L4 represented a minor rRNA interaction site, the C–terminus could presumably be removed without compromising the incorporation of the protein into the ribosome (Li et al., 1996). The possible role of the mRNA-binding site as a minor rRNA interaction surface could be the above-mentioned factor responsible for the conservation of the regulatory functions of L4 proteins without a concomitant conservation of S10 leader sequences.

A potential protein–protein interaction site

In order to perform its various functions, it is likely that L4 has to interact with other protein components of translation and transcription. Because one side of L4 seems to be occupied by RNA interactions, it is tempting to speculate that protein contacts will be mediated through the opposite, negatively charged flank. While the lack of obvious hydrophobic patches seems to argue for a surface exposure of this region of the protein, tritium bombardment suggests that L4 is well buried within the large subunit (Agafonov et al., 1997). Partial models of the bacterial 50S subunit show that L4 forms a distinct structural unit with the other r–proteins believed to be involved in the peptidyl transferase activity, i.e. L2, L3 and L16, and is also placed near L29 (Walleczek et al., 1988; Lotti et al., 1989). Point mutants lacking conserved residues, such as Glu161 or Asp127, may be valuable in deciding whether the negative L4 surface area is really mediating interactions with other proteins and to find out whether a dissection between interaction sites with the translational and the transcriptional assemblies can be discerned.

Comparisons with structurally homologous proteins

We may gain insight into the RNA-binding features of r–proteins by investigating how homologous proteins recognize nucleic acids. A homologous organization of L4 and domain II of r–protein L1 has been recognized. L1 is believed to bind its RNA target in the interface between its two domains (Nikonov et al., 1996). The C–terminal end of helix α5L1 harbors the conserved domain II residues important for RNA binding. These residues correspond to the C–terminus of helix α3 in TmaL4 (Figure 4A), which shows a large variability at the amino acid level among the different bacterial L4 proteins. The side chains of residues such as Lys117, Tyr118, Arg119 and Lys122 are involved in many electrostatic interactions mainly with the N–terminus of TmaL4. Therefore, it is not likely that these amino acids can participate in binding to RNA without a major structural rearrangement. The second identified homologous protein, PTPase, harbors a phosphate-binding loop motif between β1 and α1 (Figure 4B). This area is equivalent to the connecting loop between β4 and α5 in TmaL4 and exhibits no sequence conservation among bacteria. Moreover, the conserved residue Glu161 of this loop is part of the electronegative L4 surface, not implicated in RNA binding. Therefore, the β4–α5 loop of TmaL4 is probably not involved in RNA binding.

Materials and methods

Crystallization and data collection

Details of the cloning, overexpression and purification of L4 from T.maritima will be the subject of a separate communication (M.Worbs and M.C.Wahl, submitted). Briefly, crystals of the native protein were grown at 18°C by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method, with a reservoir containing 100 mM citrate pH 3.8–6.0, 35–38% PEG 400 and 200 mM ammonium acetate. Crystallization drops consisted of 3 μl of protein solution with a concentration of 9.4 mg/ml in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.0, and a 1.5 μl reservoir. Normally, crystals grew within 5 days to a maximal size of 0.2 × 0.15 × 0.1 mm3. The space group was orthorhombic P212121 with unit cell dimensions of a = 43.0 Å, b = 48.6 Å and c = 112.0 Å, suggesting one molecule per asymmetric unit. A 2.5 Å native data set was recorded at room temperature using a MarResearch 30 cm image plate detector mounted on a Rigaku RU200 rotating anode X-ray generator with λ = 1.542 Å. Heavy atom derivative crystals were produced by conventional soaking techniques. Derivative crystals were measured at room temperature as above. High resolution data sets to 1.7 Å resolution were subsequently taken from both native and heavy atom-derivatized crystals at beamline BW6 at the Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron (DESY), Hamburg, Germany, employing a MarResearch CCD detector. The crystals were frozen at 100 K, with the mother liquor serving as cryoprotectant. All data sets were processed with the HKL package (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997).

Structure determination and refinement

Scaling of the data as well as Patterson searches for heavy atom derivatives were carried out with the CCP4 program suite (Collaborative Computational Project, 1994). Friedel pairs of the identified heavy metal derivatives were not merged to make use of the anomalous signals. Heavy atom parameters of identified derivatives were all refined individually with the program MLPHARE (Otwinowski, 1991), including anomalous data. The positions of heavy metal atoms were then confirmed by cross-difference Fourier techniques. The corresponding multiple isomorphous replacement map including anomalous scattering (MIRAS) was calculated with the program SHARP (de la Fortelle and Bricogne, 1997) and had an overall figure of merit of 0.79 after solvent flattening (assumed solvent content of 43%). It allowed tracing of most of the polypeptide chain including side chains. Model building was carried out in MAIN (Turk, 1996). The initial model was subjected to rigid body and positional refinements, using CNS (Brünger et al., 1998). After several cycles of manual rebuilding and positional refinement, the model was transferred to the 1.7 Å resolution native data set and further refined by B-factor calculations, incorporation of waters by automated procedures (CNS) and finally by two rounds of simulated annealing. The progress of all refinement procedures was monitored by using 5% of the reflections to calculate a free R-factor (Rfree). In the last two rounds of refinement, annealed composite 2Fo – Fc ‘omit’ maps, leaving out 10% portions of the model, were calculated and inspected manually. The final model showed good stereochemistry as judged with the program PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993). Occupancies for residues 186–191 were set to zero, because the electron density was badly defined even after the final refinement. Some side chains of amino acids in outer regions of the protein showed weak electron density and were set to zero as well. The numbering of the model corresponds to the published T.maritima sequence (Sanangelantoni et al., 1994; Nelson et al., 1999). The structure coordinates have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb; accession No. 1DMG).

CD spectroscopy

CD spectral scans between 190 and 250 nm were recorded with a J-715 spectropolarimeter (JASCO Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with TmaL4 at a concentration of 0.1086 μg/ml in 10 mM HEPES buffer. The spectra were interpreted as a mixture of secondary structure elements by the self-consistent method (Sreerama and Woody, 1993). Exact protein concentrations were deduced from quantitative amino acid analyses.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Gleb P.Bourenkov and Hans D.Bartunik for their assistance during the collection of the high resolution data sets at DESY (Hamburg, Germany), and Elisabeth Weyher-Stingl, Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie (Martinsried, Germany), for recording of the CD spectra. Quantitative amino acid analyses were performed by Dr J.Kellermann, Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie. M.C.W. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Peter-and-Traudl-Engelhorn Stiftung and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

References

- Agafonov D.E., Kolb, V.A. and Spirin, A.S. (1997) Proteins on ribosome surface: measurements of protein exposure by hot tritium bombardment technique. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 12892–12897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albright R.A. and Matthews, B.W. (1998) Crystal structure of λ-Cro bound to a consensus operator at 3.0 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol., 280, 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen T., Shen, P., Samsel, L., Liu, R., Lindahl, L. and Zengel, J.M. (1999) Phylogenetic analysis of L4-mediated autogenous control of the S10 ribosomal protein operon. J. Bacteriol., 181, 6124–6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt E., Kromer, W. and Hatakeyama, T. (1990) Organization and nucleotide sequence of a gene cluster coding for eight ribosomal proteins in the archaebacterium Halobacterium marismortui. J. Biol. Chem., 265, 3034–3039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni C., Mariottini, P., Annesi, F. and Amaldi, F. (1993) Human ribosomal protein L4: cloning and sequencing of the cDNA and primary structure of the protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1216, 475–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban N., Nissen, P., Hansen, J., Capel, M., Moore, P.B. and Steitz, T.A. (1999) Placement of protein and RNA structures into a 5 Å-resolution map of the 50S ribosomal subunit. Nature, 400, 841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton G.J. (1993) ALSCRIPT: a tool to format multiple sequence alignments. Protein Eng., 6, 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battiste J.L., Mao, H., Rao, N.S., Tan, R., Muhandiram, D.R., Kay, L.E., Frankel, A.D. and Williamson, J.R. (1996) α helix–RNA major groove recognition in an HIV-1 rev peptide–RRE RNA complex. Science, 273, 1547–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan R.G., Roderick, S.L., Takeda, Y. and Matthews, B.W. (1990) Protein–DNA conformational changes in the crystal structure of a λ Cro–operator complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 8165–8169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T., et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult C.J., et al. (1996) Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science, 273, 1058–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate J., Yusupov, M., Yusupova, G., Earnest, T. and Noller, H. (1999) X–ray crystal structures of 70S ribosome functional complexes. Science, 285, 2095–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerreti D.P., Mattheakis, L.C., Kearny, K.R., Vu, K.R. and Nomura, M. (1988) Translational regulation of the spc operon in Escherichia coli. Identification and structural analysis of the target site for S8 repressor protein. J. Mol. Biol., 204, 309–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y.L., Suzuki, K., Olvera, J. and Wool, I.G. (1993) Zinc finger-like motifs in rat ribosomal proteins S27 and S29. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 649–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y.L., Olvera, J. and Wool, I.G. (1995) The primary structures of rat ribosomal proteins L4 and L41. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 214, 810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittum H.S. and Champney, W.S. (1994) Ribosomal protein gene sequence changes in erythromycin resistant mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 176, 6192–6198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittum H.S. and Champney, W.S. (1995) Erythromycin inhibits the assembly of the large ribosomal subunit in growing Escherichia coli cells. Curr. Microbiol., 30, 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons W.M. Jr, May, J.L.C., Wimberley, B.T., McCutcheon, J.P., Capel, M.S. and Ramakrishnan, V. (1999) Structure of a bacterial 30S ribosomal subunit at 5.5 Å resolution. Nature, 400, 833–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project No. 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D, 50, 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn G.L., Draper, D.E., Lattman, E.E. and Gittis, A.G. (1999) Crystal structure of a conserved ribosomal protein–RNA complex. Science, 284, 1171–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg A.E. (1989) The functional role of ribosomal RNA in protein synthesis. Cell, 57, 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C., White, S.W. and Ramakrishnan, V. (1996) The crystal structure of ribosomal protein L14 reveals an important organizational component of the translational apparatus. Structure, 4, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C., Gerstner, R.B., Draper, D.E., Ramakrishnan, V. and White, S.W. (1998) The crystal structure of ribosomal protein S4 reveals a two-domain molecule with an extensive RNA-binding surface: one domain shows structural homology to the ETS DNA-binding motif. EMBO J., 17, 4545–4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fortelle E. and Bricogne, G. (1997) Maximun-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement in the MIR and MAD methods. Methods Enzymol., 276, 472–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper D.E. (1989) How do proteins recognize specific RNA sites? New clues from autogenously regulated ribosomal proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci., 14, 335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper D.E. and Reynaldo, L.P. (1999) RNA binding strategies of ribosomal proteins. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann R.D., et al. (1995) Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science, 269, 496–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser C.M., et al. (1995) The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science, 270, 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman D. and Argos, P. (1995) Knowledge-based protein secondary structure assignment. Proteins, 23, 566–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory S. and Dahlberg, A. (1999) Erythromycin resistance mutations in ribosomal proteins L22 and L4 perturb the higher order structure of 23S ribosomal RNA. J. Mol. Biol., 289, 827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross U., Chen, J.H., Kono, D.H., Lobo, J.G. and Yu, D.T. (1989) High degree of conservation between ribosomal proteins of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res., 17, 3601–3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulle H., Hoppe, E., Osswald, M., Greuer, B., Brimacombe, R. and Stöffler, G. (1988) RNA–protein cross-linking in Escherichia coli 50S ribosomal subunits, determination of sites on 23S RNA that are cross-linked to proteins L2, L4, L24 and L27 by treatment with 2–iminothiolane. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 815–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampl H., Schulze, H. and Nierhaus, K.H. (1981) Ribosomal components from Escherichia coli 50S subunits involved in the reconstitution of peptidyltransferase activity. J. Biol. Chem., 256, 2284–2288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig S., Kruft, V. and Wittmann-Liebold, B. (1992) Primary structures of ribosomal proteins L3 and L4 from Bacillus stearothermophilus. Eur. J. Biochem., 207, 877–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman D.W., Davies, C., Gerchman, S.E., Kycia, J.H., Porter, S.J., White, S.W. and Ramakrishnan, V. (1994) Crystal structure of prokaryotic ribosomal protein L9: a bi-lobed RNA-binding protein. EMBO J., 13, 205–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L. and Sander, C. (1993) Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol., 233, 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen M., Christensen, T., Dennis, P.P. and Fiil, N.P. (1982) Autogenous control: ribosomal protein L10–L12 complex binds to the leader sequence of its mRNA. EMBO J., 1, 999–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P.J. (1991) MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 24, 946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Moss, D.S. and Thornton, J.M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Legault P., Li, J., Mogridge, J., Kay, L.E. and Greenblatt, J. (1998) NMR structure of the bacteriophage λ N peptide/boxB RNA complex: recognition of a GNRA fold by an arginine-rich motif. Cell, 93, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Lindahl, L. and Zengel, J.M. (1996) Ribosomal protein L4 from Escherichia coli utilizes nonidentical determinants for its structural and regulatory functions. RNA, 2, 24–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljas A. (1991) Comparative biochemistry and biophysics of ribosomal proteins. Int. Rev. Cytol., 124, 103–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljas A. and Al-Karadaghi, S. (1997) Structural aspects of protein synthesis. Nature Struct. Biol., 4, 767–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljas A. and Garber, M. (1995) Ribosomal proteins and elongation factors. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 5, 721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone C.D. and Barton, G.J. (1993) Protein sequence alignments: a strategy for the hierarchical analysis of residue conservation. Comput. Appl. Biosci., 9, 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotti M., Noah, M., Stoffler-Meilicke, M. and Stoffler, G. (1989) Localization of proteins L4, L5, L20 and L25 on the ribosomal surface by immuno-electron microscopy. Mol. Gen. Genet., 216, 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzati P. (1952) Traitement statistique des erreurs dans la détermination des structures cristallines. Acta Crystallogr., 5, 802–810. [Google Scholar]

- Maly P., Rinke, J., Ulmer, E., Zwieb, C. and Brimacombe, R. (1980) Precise localization of the site of cross-linking between protein L4 and 23S ribonucleic acid induced by mild ultraviolet irradiation of Escherichia coli 50S ribosomal subunits. Biochemistry, 19, 4179–4188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus M.A., Hinck, A.P., Huang, S., Draper, D.E. and Torchia, D.A. (1997) High resolution solution structure of ribosomal protein L11-C76, a helical protein with a flexible loop that becomes structured upon binding to RNA. Nature Struct. Biol., 4, 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt E.A. and Bacon, D.J. (1997) Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol., 277, 505–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller K. and Brimacombe, R. (1975) Specific cross-linking of proteins S7 and L4 to ribosomal RNA, by UV irradiation of Escherichia coli ribosomal subunits. Mol. Gen. Genet., 141, 343–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore P.B. (1998) The three-dimensional structure of the ribosome and its components. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 27, 35–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzin A.G., Brenner, S.F., Hubbard, T. and Chothia, C. (1995) Scop: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol., 247, 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa A., Nakashima, T., Taniguchi, M., Hosaka, H., Kimura, M. and Tanaka, I. (1999) The three-dimensional structure of the RNA-binding domain of ribosomal protein L2; a protein at the peptidyl transferase center of the ribosome. EMBO J., 18, 1459–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K.E., et al. (1999) Evidence for lateral gene transfer between Archaea and bacteria from genome sequence of Thermotoga maritima. Nature, 399, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls A., Sharp, K.A. and Honig, B. (1991) Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins, 11, 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierhaus K.H. (1991) The assembly of prokaryotic ribosomes. Biochimie, 73, 739–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikonov S., et al. (1996) Crystal structure of the RNA binding ribosomal protein L1 from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J., 15, 1350–1359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M., Yates, J.L., Dean, D. and Post, L.E. (1980) Feedback regulation of ribosomal protein gene expression in Escherichia coli: structural homology between ribosomal RNA and ribosomal protein mRNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 7084–7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo S., Muto, A., Kawauchi, Y., Yamao, F. and Osawa, S. (1987) The ribosomal protein gene cluster of Mycoplasma capricolum. Mol. Gen. Genet., 210, 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. (1991) Maximum likelihood refinement of heavy-atom parameters. In Wolf,W., Evans,P.R. and Leslie,A.G.W. (eds), Isomorphous Replacement and Anomalous Scattering. Proceedings of the CCP4 Study Weekend. SERC Daresbury Laboratory, Warrington, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. and Minor, W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol., 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oubridge C., Ito, N., Evans, P.R., Teo, C.H. and Nagai, K. (1994) Crystal structure at 1.92 Å resolution of the RNA-binding domain of the U1A spliceosomal protein complexed with an RNA hairpin. Nature, 372, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavletich N.P. and Pabo, C.O. (1991) Zinc finger–DNA recognition: crystal structure of a Zif268–DNA complex at 2.1 Å. Science, 252, 809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer T., Jorcke, D., Feltens, R. and Hartmann, R.K. (1995) Direct linkage of str-, S10- and spc-related gene clusters in Thermus thermophilus HB8 and sequences of ribosomal proteins L4 and S10. Gene, 167, 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan V. and White, S.W. (1998) Ribosomal protein structures: insights into the architecture, machinery and evolution of the ribosome. Trends Biochem. Sci., 23, 208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B. and Sander, C. (1993) Prediction of protein secondary structure at better than 70% accuracy. J. Mol. Biol., 232, 584–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanangelantoni A.M., Bocchetta, M., Cammarano, P. and Tiboni, O. (1994) Phylogenetic depth of S10 and spc operons: cloning and sequencing of a ribosomal protein gene cluster from the extremely thermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. J. Bacteriol., 176, 7703–7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze H. and Nierhaus, K.H. (1982) Minimal set of ribosomal components for reconstitution of the peptidyltransferase activity. EMBO J., 1, 609–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen P., Zengel, J.M. and Lindahl, L. (1988) Secondary structure of the leader transcript from the Escherichia coli S10 ribosomal protein operon. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 8905–8924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.R., et al. (1997) Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum deltaH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J. Bacteriol., 179, 7135–7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreerama N. and Woody, R.W. (1993) A self-consistent method for the analysis of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism. Anal. Biochem., 209, 32–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X.D., Taddei, N., Stefani, M., Ramponi, G. and Nordlund, P. (1994) The crystal structure of a low-molecular-weight phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase. Nature, 370, 575–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiede B., Urlaub, H., Neubauer, H., Grelle, G. and Wittmann-Liebold, B. (1998) Precise determination of RNA–protein contact sites in the 50S ribosomal subunit of Escherichia coli. Biochem. J., 334, 39–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocilj A., et al. (1999) The small ribosomal subunit from Thermus thermophilus at 4.5 Å resolution: Pattern fittings and the identification of a functional site. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14252–14257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk D. (1996) An interactive software for density modifications, model building, structure refinement and analysis. In Bourne,P.E. and Watenpaugh,K. (eds), Proceedings of the 1996 Meeting of the International Union of Crystallography Macromolecular Computing School. [Google Scholar]

- Urlaub H., Kruft, V., Bischof, O., Müller, E.-V. and Wittmann-Liebold, B. (1995) Protein–rRNA binding features and their structural and functional implications in ribosomes as determined by cross-linking studies. EMBO J., 14, 4578–4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walleczek J., Schuler, D., Stoffler-Meilicke, M., Brimacombe, R. and Stoffler, G. (1988) A model for the spatial arrangement of the proteins in the large subunit of the Escherichia coli ribosome. EMBO J., 7, 3571–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberly B.T., Guymon, R., McCutcheon, J.P., White, S.W. and Ramakrishnan, V. (1999) A detailed view of a ribosomal active site: the structure of the L11–RNA complex. Cell, 97, 491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Guha Thakurta, D. and Draper, D.E. (1997) The RNA binding domain of ribosomal protein L11 is structurally similar to homeodomains. Nature Struct. Biol., 4, 24–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasumoto K., Liu, H., Jeong, S.M., Ohashi, Y., Kakinuma, S., Tanaka, K., Kawamura, F., Yoshikawa, H. and Takahashi, H. (1996) Sequence analysis of a 50 kb region between spo0H and rrnH on the Bacillus subtilis chromosome. Microbiology, 142, 3039–3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates J.L. and Nomura, M. (1980) E.coli ribosomal protein L4 is a feedback regulatory protein. Cell, 21, 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengel J.M. and Lindahl, L. (1990) Escherichia coli ribosomal protein L4 stimulates transcription termination at a specific site in the leader of the S10 operon independent of L4-mediated inhibiton of translation. J. Mol. Biol., 213, 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengel J.M. and Lindahl, L. (1993) Domain I of 23S rRNA competes with a paused transcription complex for ribosomal protein L4 of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 2429–2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengel J.M. and Lindahl, L. (1994) Diverse mechanisms for regulating ribosomal protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol., 47, 331–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengel J.M. and Lindahl, L. (1996) A hairpin structure upstream of the terminator hairpin required for ribosomal protein L4-mediated attenuation control of the S10 operon of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 178, 2383–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengel J.M., Mueckl, D. and Lindahl, L. (1980) Protein L4 of the E.coli ribosome regulates an eleven gene r protein operon. Cell, 21, 523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengel J.M., Vorozheikina, D., Li, X. and Lindahl, L. (1995) Regulation of the Escherichia coli S10 ribosomal protein operon by heterologous L4 ribosomal proteins. Biochem. Cell Biol., 73, 1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurawski G. and Zurawski, S.M. (1985) Structure of the Escherichia coli S10 ribosomal protein operon. Nucleic Acids Res., 13, 4521–4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]