SUMMARY

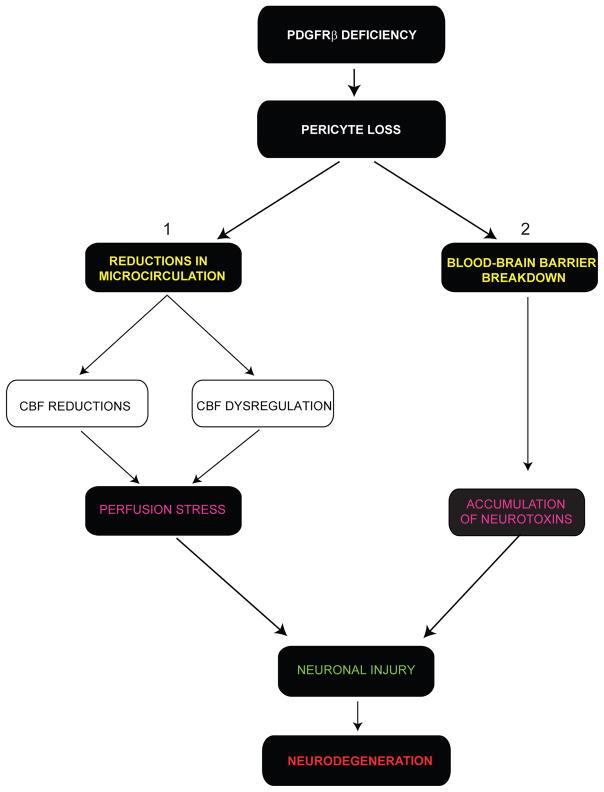

Pericytes play a key role in the development of cerebral microcirculation. The exact role of pericytes in the neurovascular unit in the adult brain and during brain aging remains, however, elusive. Using adult viable pericyte-deficient mice, we show that pericyte loss leads to brain vascular damage by two parallel pathways: (1) reduction in brain microcirculation causing diminished brain capillary perfusion, cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood flow responses to brain activation which ultimately mediates chronic perfusion stress and hypoxia, and (2) blood-brain barrier breakdown associated with brain accumulation of serum proteins and several vasculotoxic and/or neurotoxic macromolecules ultimately leading to secondary neuronal degenerative changes. We show that age-dependent vascular damage in pericyte-deficient mice precedes neuronal degenerative changes, learning and memory impairment and the neuroinflammatory response. Thus, pericytes control key neurovascular functions that are necessary for proper neuronal structure and function, and pericytes loss results in a progressive age-dependent vascular-mediated neurodegeneration.

INTRODUCTION

An intact functional neurovascular unit is comprised of endothelial cells, pericytes, glia and neurons (Zlokovic, 2008; Lo and Rosenberg, 2009; Segura et al., 2009; Iadecola, 2010). Pericytes ensheathe the capillary wall making direct contacts with endothelial cells (Armulik et al., 2005; Diaz-Florez et al., 2009). Endothelial-secreted platelet derived growth factor B (PDGF-B) binds to the platelet derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRβ) on pericytes initiating multiple signal transduction pathways regulating proliferation, migration, and recruitment of pericytes to the vascular wall (Armulik et al., 2005; Lebrin et al., 2010). Much of the insight into brain pericyte biology arose from developmental studies and the analysis of pericyte deficient transgenic mice with disrupted PDGF-B/PDGFRβ signaling (Lindahl et al., 1997; Lindblom et al., 2003; Tallquist et al., 2003; Gaengel et al., 2009).

In the developing central nervous system (CNS), pericyte loss in embryonic lethal PDGF-B null and PDGFRβ null mice leads to endothelial cell hyperplasia suggesting that pericytes control endothelial cell number and microvessel architecture, but do not determine microvessel density, length or branching (Lindahl P, et al. 1997; Hellstrom M, et al. 1999; Hellström et al., 2001). Earlier in vitro studies have also demonstrated that pericytes inhibit endothelial cell proliferation (Orlidge and D’Amore, 1987; Hirschi et al., 1999). Endothelial-specific PDGF-B deletion results in viable mice that develop diabetic-like proliferative retinopathy, characterized by an increased number of acellular regressing capillaries (Enge et al., 2002). In experimental models of diabetic retinopathy, hyperglycemia has been found to lead to diminished PDGFRβ signaling resulting in pericyte apoptosis (Geraldes et al., 2009), increased endothelial cell proliferation and increased numbers of acellular capillaries in pericyte-deficient PDGF-B+/− mice (Hammes et al., 2002). In contrast, studies focusing on tumor angiogenesis have suggested that pericyte loss may indeed lead to endothelial apoptosis (Song et al., 2005). Therefore, it is unclear as to what role pericytes may play in modulating the adult cerebrovascular microcirculatory structure and/or function.

In the adult brain, pericytes modulate capillary diameter by constricting the vascular wall (Peppiatt et al., 2006), a process which during ischemia may obstruct capillary blood flow (Yemisci et al., 2009; Vates et al., 2010). Still, relatively little is known about the role of pericytes in vascular maintenance in the adult and aging brain. It is also unknown whether pericyte degeneration can influence the neuronal phenotype. Using two different adult viable pericyte-deficient mouse strains with variable degrees of pericyte loss (Tallquist et al., 2003; Winkler et al., 2010), we have investigated whether pericyte loss in the adult brain and during aging can influence brain capillary density, resting cerebral blood flow (CBF), CBF response to brain activation and blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity to serum proteins and blood-derived potentially cytotoxic and/or neurotoxic molecules. We have also studied the effects of an age-dependent pericyte loss and resulting hemodynamic disturbances on neuronal structure and function and the onset of neuroinflammation.

RESULTS

Reductions in Cerebral Microcirculation and Blood Flow in Pericyte-Deficient Mice

We have recently reported that PDGFRβ is exclusively expressed in pericytes, and not in neurons, astrocytes or endothelial cells, in different brain regions of adult viable 129S1/SvlmJ mice with normal or deficient PDGFRβ signaling (Winkler et al., 2010). Therefore, a genetic disruption of PDGFRβ signaling in Pdgfrβ+/− mice and the F7 homozygous mutants with two hypomorphic alleles of Pdgfrβ exhibiting ~ 35% and 65% pericyte loss in the embryonic CNS, respectively (Tallquist et al., 2003), results in a primary pericyte-specific insult.

Using three-color confocal imaging analysis for PDGFRβ and the well established pericyte markers chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan NG2 (Armulik et al., 2005; Peppiatt et al., 2006; Pfister et al., 2008; Yemisci et al., 2009) and desmin (Hellstrom et al., 1999;Tallquist et al., 2003; Song et al., 2005, Kokovay et al., 2006) along with endothelial-specific Lycopersicon Esculentum lectin fluorescent staining to visualize brain capillary profiles, we show that PDGFRβ colocalizes with pericytes on brain capillaries, as illustrated in cortical layer II and hippocampal CA1 regions in 6 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ control mice (Fig. S1A–C), as reported (Winkler et al., 2010). There was no detectable colocalization of PDGFRβ with the neurofilament-H marker of neuronal cell processes (SMI-32) or the neuronal-specific nuclear antigen A60 (NeuN), as illustrated in cortical layers II and III in 2 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and Pdgfrβ+/− mice, respectively (Fig. 1A) which corroborates a previous report showing that PDGRFβ is not expressed in neurons in viable F7 mutants (Winkler et al., 2010). Hematoxylin and eosin staining provides a low magnification view of a control mouse cerebral hemisphere adjacent to sections subsequently utilized for all fluorescent imaging experiments (Fig. S1A).

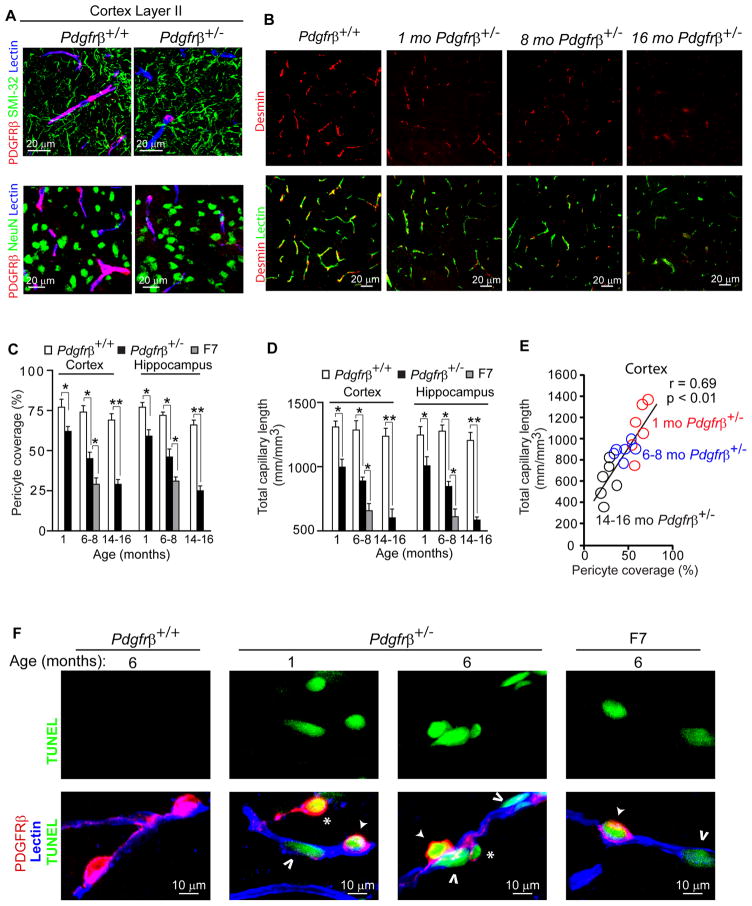

Figure 1. Age-Dependent Pericyte Loss and Brain Microvascular Regression in Mice with Pericyte-Specific PDGFRβ Deficient Signaling.

(A) Confocal microscopy analysis of PDGFRβ on perivascular pericytes (red), SMI-32 neurofilament marker (green, top panels), neuronal-specific marker NeuN (green, bottom panels) and lectin-positive brain capillaries (blue) in the layer II parietal cortex of a 2 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and Pdgfrβ+/− mice showing no colocalization of PDGFRβ with neurons.

(B) Representative confocal microscopy analysis of desmin immunodetection showing pericyte coverage (red) of lectin-positive brain capillaries (green) in the parietal cortex of an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse and 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice.

(C) Age-dependent loss of pericyte coverage in the cortex and hippocampus of 1, 6–8, and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars) and in 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bars) compared to age-matched Pdgfrβ+/+ controls (white bars). Pericyte coverage was determined as a percentage (%) of desmin-positive pericyte surface area covering lectin-positive capillary surface area that was arbitrarily taken as 100%. Total of 36 and 24 randomly chosen fields (420 × 420 μm) from 6 non-adjacent cortical and hippocampal sections, respectively, were analyzed per mouse. Mean ± s.e.m., n=6 mice per group; *p<0.05 or **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA.

(D) Length of lectin-positive capillary profiles in the cortex and hippocampus of 1, 6–8, and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mice (white bars) and Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars), and 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bars). Total of 36 and 24 observations in the cortex and hippocampus from the same fields as in C were analyzed per mouse, respectively. Mean ± s.e.m., n=6 mice per group; *p<0.05 or **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA.

(E) Positive correlation between age-dependent reduction in capillary length and loss of pericyte coverage in the cortex of Pdgfrβ+/− mice. Single data points were from 1(red), 6–8 (blue) and 14–16 (black) month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (n=18). r = Pearson’s coefficient.

(F) Confocal microscopy analysis of TUNEL (green, top panels), PDGFRβ immunodetection on pericytes (red) and lectin-positive capillaries (blue) in the cortex of 6 month old Pdgfrβ+/+, 1 and 6 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mouse and 6 month old F7 mouse. Closed arrow, TUNEL-positive attached pericyte; *, TUNEL-positive detaching pericyte; Open arrow, TUNEL-positive endothelial cell. (See Fig. S1)

Using dual immunostaining for desmin and lectin-positive brain capillary profiles we show an age-dependent progressive loss of pericyte coverage in the cortex (Fig. 1B–C) and hippocampus (Fig. 1C) and other brain regions (not shown) in adult viable Pdgfrβ+/− mice compared to Pdgfrβ+/+ age-matched littermate controls, i.e., approximately 20%, 40% and 60% loss at 1, 6–8, and 14–16 months of age (Fig 1C). An age-dependent pericyte loss in Pdgfrβ+/− mice has been confirmed by counting NG2-positive pericytes per mm2 of endothelial-specific CD31-positive capillary profiles (Fig. S1D–E). Pdgfrβ+/+ control mice did not show significant differences in pericyte coverage between 1, 6–8 and 14–16 months (Fig. 1C).

In contrast to endothelial hyperplasia in Pdgfrβ−/− embryonic CNS (Helstrom et al., 2001) and lack of vascular changes during CNS development in Pdgfb+/− and Pdgfrβ+/− embryos (Leveen et al., 1994; Soriano, 1994), we show that a modest pericyte deficiency in 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice results in a significant post-natal 20–25% reduction in the microvascular length in the cortex and hippocampus and other brain regions (not shown), as demonstrated by lectin-positive (Fig. 1B,D) and CD31-positive (Fig. S1D,F) capillary profiles. We also show an age-dependent progressive reduction in Pdgfrβ+/− mice of lectin-positive and/or CD31-positive microvascular profiles in the cortex and hippocampus by 30–34% and 50–52% at 6–8 and 14–16 months, respectively (Fig. 1B,D; Fig. S1D,F).

There was a strong positive correlation between an age-dependent loss in both pericyte coverage and pericyte number and microvascular reductions (Fig. 1E; Fig. S1G), indicating that pericyte degeneration is associated with progressive age-dependent microvascular degeneration. This was corroborated in 6–8 month old F7 mutant mice and Pdgfrβ+/− mice, by showing that F7 mutants which exhibit a significantly greater, i.e., ~ 60% pericyte loss in the cortex and hippocampus than Pdgfrβ+/− mice (Fig. 1C), had significantly greater 45–53% loss in the microvascular length in the cortex and hippocampus compared to 30–34% reduction in Pdgfrβ+/− mice (Fig. 1D). Using three-color immunostaining for pericytes and endothelial cells and TUNEL staining for DNA fragmentation suggestive of apoptotic and/or necrotic cell death, we show that Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice, but not the control Pdgfrβ+/+ mice, occasionally display degenerating pericytes associated with degenerating TUNEL-positive capillary endothelium, as illustrated in the cortex of 1 and 6 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and 6 month old F7 mice (Fig. 1F).

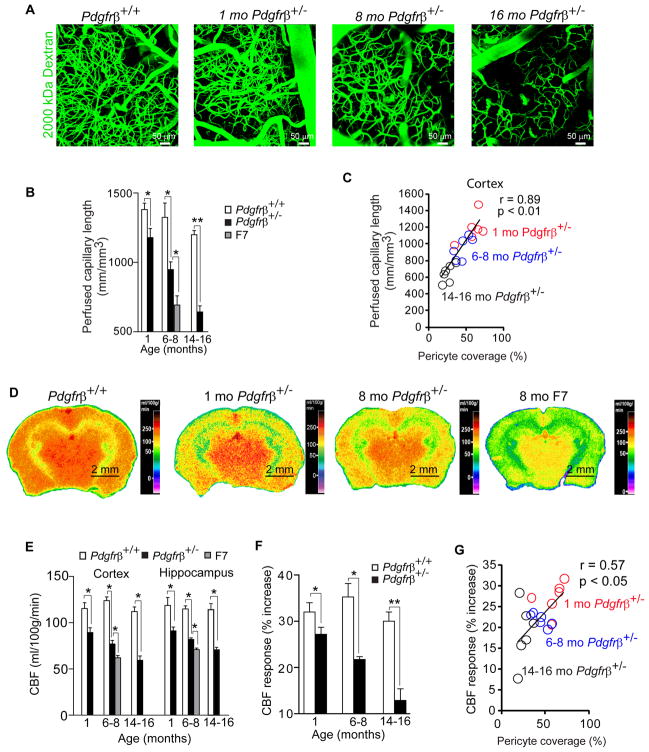

Using in vivo multiphoton microscopy imaging of fluorescein-conjugated mega-dextran (MW=2,000,000 Da), we generated 3-dimensional 0.5 mm z-stack cortical angiograms in Pdgfrβ+/− mice and age-matched controls to find out whether microvascular reductions determined by histological quantification (Fig. 1D; Fig. S1F) reflect a capillary perfusion deficit in vivo. The analysis of angiograms has indicated an age-dependent reduction in the length of perfused cortical microvessels, i.e., by 18%, 30% and 47% at 1, 6–8 and 14–16 months of age, respectively (Fig. 2A–B). These results were comparable to the reductions determined by histological analysis indicating no discrepancy between the two methods. There was a strong positive correlation between age-dependent reductions in pericyte loss and perfused capillary length (Fig. 2C). The F7 mutant mice at 6–8 months of age exhibited significantly greater reduction in the perfused cortical vascular length compared to 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice, i.e., 48% of controls compared to 30% of controls, respectively (Fig. 2B), consistent with significantly greater pericyte degeneration. In these studies imaging of perfused capillaries was accomplished within 40 minutes of the cranial window surgery before any significant inflammation or gliosis is present (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Figure 2. Diminished Brain Capillary Perfusion and Changes in Cerebral Blood Flow in Pericyte-Deficient Mice.

(A) Perfusion of cortical microvessels studied by in vivo multiphoton microscopy analysis of fluorescein-conjugated mega-dextran (MW=2,000,000; green) in 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse, and 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice.

(B) Quantification of perfused capillary length from angiograms obtained as in A. in 1, 6–8, and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mice (white bars) and Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars), and in 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bars). Two to three angiograms were analyzed per mouse.

(C) Positive correlation between age-dependent reductions of brain capillary perfusion and desmin-positive pericyte coverage of cortical capillaries in Pdgfrβ+/− mice. Single data points were from 1 (red), 6–8 (blue) and 14–16 (black) month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (n=18). r = Pearson’s coefficient.

(D) 14C-iodoantipyrine (IAP) autoradiography of the cerebral blood flow (CBF) in an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse, 1 and 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice and an 8 month old F7 mouse.

(E) Local CBF determined using 14C-IAP autoradiography as in D. in 1, 6–8, and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mice (white bars) and Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars), and in 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bars). (See Table S1).

(F) CBF responses to whisker-barrel cortex vibrissal stimulus (% increase from basal values) in 1, 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mice (white bars) and Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars).

(G) Positive correlation between diminished CBF responses to a stimulus and an age-dependent loss of pericyte coverage of cortical capillaries in Pdgfrβ+/− mice. Single data points were from 1 (red), 6–8 (blue) and 14–16 (black) month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (n=18). r =Pearson’s coefficient.

In B, C, E and F, mean ± s.e.m., n=6 mice per group; *p<0.05 or **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA.

Given that regional brain capillary density correlates with blood flow (Zlokovic, 2008), we hypothesized that pericyte-deficient mice will have diminished resting CBF. 14C-iodoantipyrine quantitive autoradiography revealed significant age-dependent 23–24%, 33–37% and 48–50% reductions in the local CBF in the cortex and hippocampus of 1, 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice compared to age-matched controls, respectively (Fig. 2D–E). The F7 mutants at 6–8 months of age had greater CBF reductions in the cortex and hippocamus than 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice, i.e., 49% and 41%, respectively (Fig. 2E). Significant CBF reductions were found in other studied brain regions of pericyte-deficient mice (Table S1).

Laser-doppler flowmetry showed diminished CBF responses to whisker-barrel cortex vibrissal stimulation in 1, 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice to 27%, 21% and 12% of basal values, respectively, compared to 32%, 34% and 31% in the corresponding age-matched controls, respectively (Fig. 2F). There was a significant positive correlation between the loss of pericyte coverage and diminished CBF responses during aging of Pdgfrβ+/− mice (Fig. 2G). The observed dysregulated CBF response in pericyte-deficient mice is consistent with previous findings suggesting that pericytes participate in the control of brain capillary diameter in response to a stimulus (Peppiatt et al., 2006).

Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Pericyte-Deficient Mice

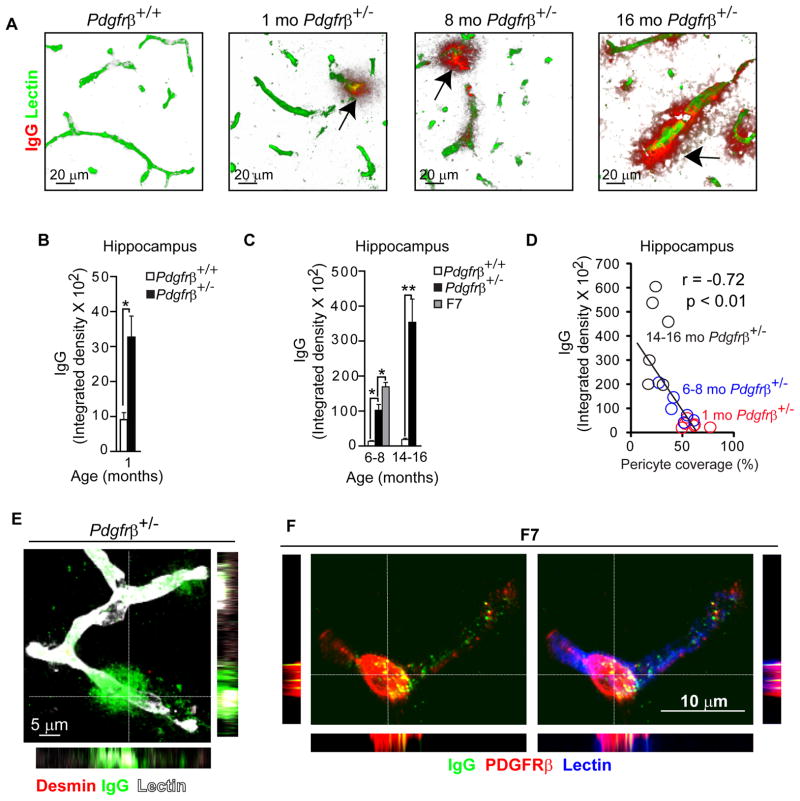

Early electron microscopy studies have shown that pericytes prevent entry of circulating exogenous horseradish peroxidase into the brain suggesting pericytes are part of the BBB for macromolecules (reviewed in Diaz et al., 2009). Whether degenerating pericytes in the aging brain can maintain the BBB in vivo to endogenous circulating macromolecules some of which are potentially cytotoxic and/or neurotoxic is, however, unknown. To test this hypothesis, we studied whether plasma-derived proteins accumulate in the brains of pericyte-deficient mice. Immunostaining for plasma-derived immunoglobulin G (IgG) and endothelial lectin, performed as we described (Zhong et al., 2008), revealed significant perivascular IgG deposits and > 3-fold increase in IgG accumulation in the hippocampus and cortex in 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice compared to controls (Fig. 3A–B; Fig. S2A). There was a progressive BBB breakdown to IgG resulting in approximately 8–10-fold, and 20–25-fold greater IgG perivascular accumulation in the hippocampus and cortex of 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice compared to age-matched controls, respectively, and a 16–18-fold increase in the hippocampus and cortex in 6–8 month old F7 mutants (Fig. 3C; Fig. S2B). We also show a significant negative correlation between the perivascular IgG brain accumulation and pericyte coverage in Pdgfrβ+/− mice (Fig. 3D; Fig. S2C). In contrast, there was no detectable IgG leakage in control mice. High resolution confocal microscopy confirmed the IgG perivascular accumulation around capillaries lacking pericyte coverage and in brain endothelium in pericyte-deficient mice (Fig. 3E). In mice exhibiting substantial loss of pericytes, the IgG accumulates were also found in some remaining pericytes, as illustrated in an 8 month old F7 mouse (Fig. 3F) in contrast to controls.

Figure 3. Age-Dependent Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption to Plasma Proteins in Pericyte-Deficient Mice.

(A) Confocal microscopy analysis of plasma-derived IgG (red) and fluorescein-conjugated lectin-positive microvessels (green) in the hippocampus of an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and in 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice. Arrows, extravascular IgG deposits.

(B–C) Quantification of extravascular IgG deposits in the hippocampus of 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bar) and Pdgfrβ+/+ controls (white bar) (B), and in 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars), and Pdgfrβ+/+ controls (white bars) and 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bar) (C).

In B and C, 24 randomly chosen fields (420 × 420 μm) within the hippocampus were analyzed from 6 non-adjacent sections per mouse. Values are mean ± s.e.m., n=6 mice per group; *p<0.05 or **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA. (See Fig. S2).

(D) Negative correlation between an age-dependent IgG brain accumulation and loss of pericyte capillary coverage in the hippocampus of Pdgfrβ+/− mice. Single data points were from 1 (red), 6–8 (blue) and 14–16 (black) month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (n=18). r = Pearson’s coefficient.

(E) Confocal microscopy imaging of IgG deposits (green) around lectin-positive capillaries (white) lacking pericyte coverage (red; negative desmin staining) in an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mouse. Orthogonal views suggest that microvessels lacking pericyte coverage have significant perivascular IgG accumulation.

(F) Confocal microscopy analysis of IgG (green) and a pericyte marker PDGFRβ (red) on lectin-positive (blue) pericyte-covered capillary in an 8 month old F7 mutant mouse. Orthogonal views show IgG accumulation in a PDGFRβ-positive pericyte in a F7 mouse.

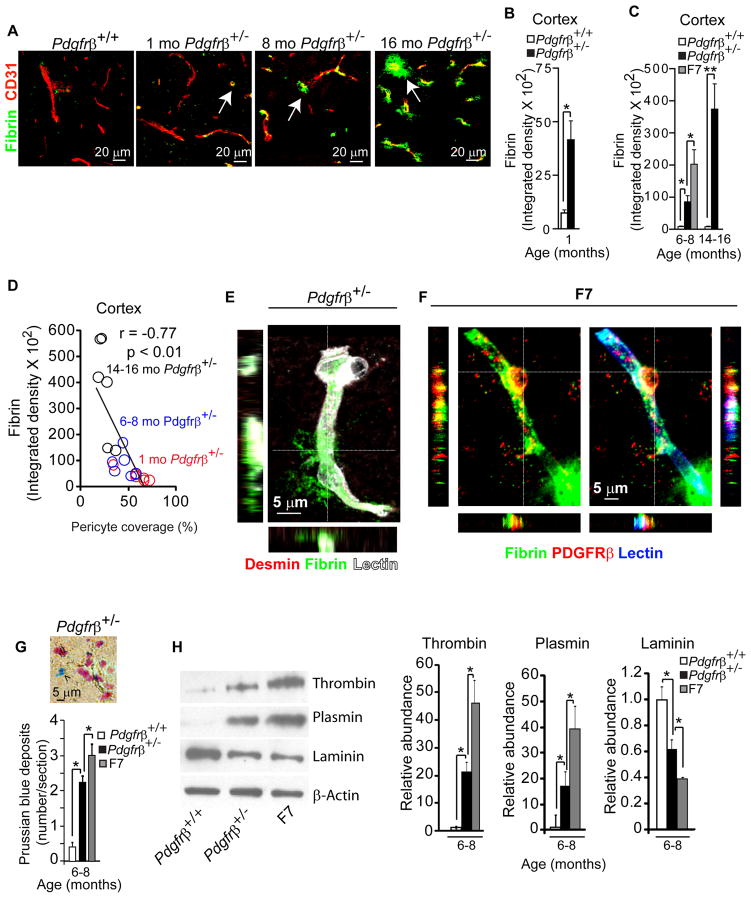

Pdgfrβ+/− mice exhibited an age-dependent increase in perivascular fibrin (Fig. 4A–C) which was shown to accelerate neurovascular damage (Paul et al., 2007). Quantification of perivascular fibrin deposits in Pdgfrβ+/− mice compared to controls indicated 6, 10 and 46-fold increase at 1, 6–8 and 14–16 months of age, respectively, as shown in the cortex (Fig. 4A–C), and similar age-dependent increases in the hippocampus (Fig. S2D–F). An increased fibrin leakage of approximately 25–30-fold was found in the cortex and hippocampus, in 6–8 month old F7 mutants (Fig. 4C). As for IgG, there was a significant negative correlation between fibrin perivascular accumulation in brain and pericyte coverage (Fig. 4D; Fig. S2F). Fibrin accumulation was particularly abundant around brain capillaries lacking pericyte coverage (Fig. 4E). Fibrin was also found in endothelial cells (Fig. 4E) and pericytes as shown in F7 mice (Fig. 4F), but was leaking from the adjacent capillaries without pericyte coverage, as illustrated in Fig. 4F (right bottom corner).

Figure 4. Pathologic Accumulations in Brains of Pericyte-Deficient Mice.

(A) Confocal microscopy analysis of fibrin (green) and CD31-positive microvessels (red) in the cortex of an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice. Arrows, extravascular fibrin deposits.

(B–C) Quantification of fibrin extravascular deposits in the cortex of 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ (white bar) and Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bar) (B), and 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ (white bars) and Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bar), and 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bar) (C). In B– C, 36 randomly chosen fields (420 × 420 μm) in the cortex were analyzed from 6 non-adjacent sections per mouse. Values are mean ± s.e.m., n=6 mice per group; *p<0.05 or **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA. (See Fig. S2).

(D) Negative correlation between an age-dependent fibrin extravascular accumulation and loss of pericyte coverage in the cortex of Pdgfrβ+/− mice. Single data points derived from 1 (red), 6–8 (blue) and 14–16 (black) month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (n=18). r = Pearson’s coefficient.

(E) Confocal microscopy imaging of fibrin deposits (green) around lectin-positive capillary (white) lacking desmin-positive (red) pericyte coverage in an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mouse. The orthogonal views show a significant perivascular fibrin accumulation.

(F) Confocal microscopy imaging of fibrin (green) and a pericyte marker PDGFRβ (red) covering a lectin-positive capillary (blue) in an 8 month old F7 mutant mouse. Orthogonal views show fibrin accumulation in a PDGFRβ-positive pericyte in a F7 mouse.

(G) Quantification of Prussian blue-positive hemosiderin deposits in sagittal brain sections of cortex plus hippocampus of 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice compared to age-matched Pdgfrβ+/+ controls. Inset, a hemosiderin deposit in the cortex of an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mouse. A total of 6 non-adjacent sections were analyzed per mouse.

(H) Immunoblotting of thrombin, plasmin and laminin in capillary-depleted brain tissue of 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+, Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice. β-actin was used as a loading control. Graphs show quantification of relative protein abundance using densitometry analysis. Mean ± s.e.m., n=6 animals per group; *p<0.05 or **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA.

To determine whether loss of pericytes can lead to pathological accumulations of neurotoxic macromolecules, we studied the brains of 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice for (i) hemosiderin deposits reflecting extravasation of the red blood cells with accumulation of hemoglobin-derived neurotoxic products such as iron that damages neurons by generating reactive oxygen species (Zhong et al., 2009); (ii) accumulation of thrombin, which at higher concentrations mediates neurotoxicity and memory impairment (Mhatre et al., 2004) and vascular damage and BBB disruption (Chen et al., 2010); and (iii) plasmin (derived from circulating plasminogen) which catalyzes the degradation of neuronal laminin promoting neuronal injury (Chen et al., 1997). As shown by Prussian blue staining, Pdgfrβ+/− mice and the F7 mutants exhibited 5 and 8-fold greater hemosiderin accumulation than controls, respectively (Fig. 4G). Immunoblot analysis of capillary-depleted brains revealed that Pdgfrβ+/− mice and the F7 mutants accumulate 21 and 46 times more thrombin than controls, respectively (Fig. 4H, upper lane, left graph). These mice also showed 17 and 39 times greater accumulation of plasmin compared to controls, respectively, accompanied with a proportional reduction in laminin content in capillary-depleted brain (Fig. 4H, middle and lower panels, and middle and right graphs). These findings show that pericyte loss leads to BBB breakdown and accumulation of vasculotoxic and neurotoxic macromolecules in brain that is proportional to the degree of pericyte loss.

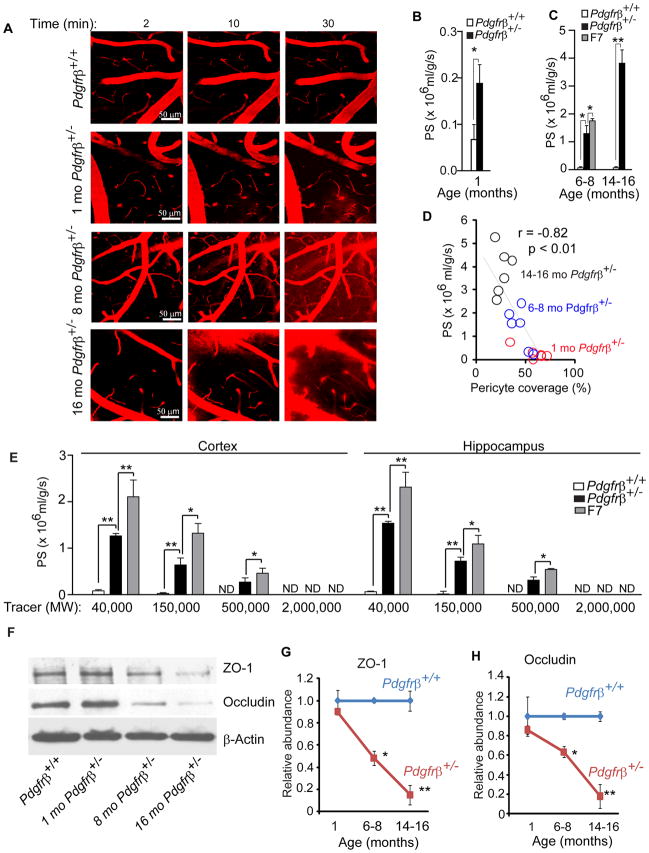

To test whether the BBB is open to acutely administered exogenous macromolecules, we performed in vivo time-lapse multiphoton imaging of the cortical vessels in layers II and III with intravenous medium size macromolecular dextran (MW = 40,000 Da, tetramethylrhodamine TMR-conjugated) in 1, 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice. In contrast to age-matched controls with an intact BBB to TMR-dextran over the 30 min period of imaging, there was a rapid age-dependent in vivo leakage of TMR-dextran in Pdgfrβ+/− mice in all age groups, beginning at 10 min and peaking at 30 min (Fig. 5A). The leakage was obvious in 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice indicating ~3-fold increase in the cerebrovascular permeability (i.e., the permeability surface area product, PS) compared to controls (Fig. 5B), and 19-fold and 54-fold greater PS value in 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice compared to their respective age-matched controls (Fig. 5C). There was a significant ~30-fold increase in the PS product to TMR-dextran in the F7 mutants (Fig. 5C). The degree of BBB leakage to dextran in Pdgfrβ+/− mice was proportional to the degree of pericyte loss (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown to Exogenous Dextran in Pericyte-Deficient Mice.

(A) In vivo time-lapse multiphoton imaging of tetramethylrhodamine (TMR) dextran (MW = 40,000; red) leakage from cortical vessels (layer II and III, approximately 100 μm from the cortical surface) in an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse, and 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice within 30 min of TMR-dextran intravenous administration.

(B–C) The cerebrovascular permeability surface area product (PS) for TMR- dextran (40,000 Da) determined by multiphoton imaging as in A. in 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bar) and control Pdgfrβ+/+ (white bar) mice (B), and 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− (black bar) and control Pdgfrβ+/+ (white bars) mice, and 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bar) (C).

(D) Negative correlation between the PS product for TMR-dextran and age-dependent loss of pericyte coverage of cortical capillaries in Pdgfrβ+/− mice. Single data points derived from 1 (red), 6–8 (blue) and 14–16 (black) month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (n=18). r = Pearson’s coefficient.

(E) The blood-brain barrier permeability PS product for TMR-dextran (40,000 Da), Cy-3-IgG (150,000 Da) FITC-Dextran (MW=500,000 Da) and fluorescein-conjugated mega-Dextran (MW=2,000,000 Da) in 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ (white bar), Pdgfrβ+/− (black bar) and F7 (gray bar) mice determined by a non-invasive fluorometric tissue analysis not requiring the cranial window surgical procedure. Mean ± s.e.m., n=4–6 animals per group. *p<0.05 or ** p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA. ND. Non-detectable.

(F) Immunoblotting of ZO-1 and occludin in isolated cortical and hippocampal capillaries from a 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ control mouse and 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice.

(G–H) Quantification of ZO-1 (G) and occludin (H) relative abundance by densitometry analysis of immunoblots in 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and Pdgfrβ+/− mice showing a progressive decrease in the tight junction proteins in the aging pericyte-deficient mice. β-actin was used as a loading control. In B, C, G and H, mean ± s.e.m., n=6 animals per group. *p<0.05 or ** p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA. (See Fig. S3–S5).

To increase confidence in our in vivo time-lapse multiphoton data and find out whether an acute 30 min cranial window procedure for the multiphoton imaging affects BBB permeability measurements, we next used a non-invasive fluorometric analysis which did not require the cranial window surgical manipulation to determine BBB permeability to TMR-dextran in 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice and F7 mutants. This non-invasive fluorescent technique confirmed an increased BBB permeability to TMR-dextran (MW=40,000 Da) in Pdgfrβ+/− mice and F7 mutants in the cortex by 18-fold and 30-fold, respectively (Fig. 5E). These results were comparable to the results obtained by in vivo multiphoton imaging indicating no discrepancy between the methods. The BBB breakdown was also seen in the hippocampus (Fig. 5E) and other brain regions (not shown).

To determine the molecular size limit of solutes that can penetrate through the abnormal BBB in the mutant mice, we studied the BBB permeability to Cy3-IgG (MW=150,000 Da), FITC-dextran (MW=500,000 Da) and Fluorescein-mega-dextran (MW=2,000,000 Da) in 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+, Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice by using a non-invasive fluorometric method. These measurements have indicated that the BBB is open to molecules ranging from 40,000 to 500,000 Da; the molecular size limit was found to be between 500,000 and 2,000,000 Da (Fig. 5E). This data suggests that molecules such as thrombin (MW=36,000 Da) and fibrinogen (MW=340,000 Da) can enter freely from the circulation into the brain across the damaged BBB and accumulate in brain.

BBB breakdown within a short period of time, as observed as in the present BBB permeability studies, typically indicates disruption of the BBB tight junctions (TJ) (Zlokovic, 2008). TJ proteins seal the endothelial barrier preventing uncontrolled entry of solutes from blood to brain. Their expression is reduced in stroke and several neurodegenerative disorders leading to the BBB breakdown (Zlokovic, 2008). TJ appearance in the embryonic CNS is associated with pericyte coverage of the endothelium (Bauer et al., 1993) and pericytes enhance the endothelial barrier integrity in vitro (Nakagwa et al., 2007; Kroll et al., 2009). Therefore, we tested whether TJ expression is altered in pericyte-deficient mice. Immunoblot analysis of TJ proteins in isolated brain capillaries revealed an age-dependent reduction in ZO-1 and occludin expression in Pdgfrβ+/− mice compared to controls by 40–50% and 80% in 6–8 and 14–16 month old mice, respectively (Fig. 5F–H). A comparison of ZO-1, occludin and claudin-5 expression in 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice and F7 mutants has revealed significant reductions by 48% and 37%, 42% and 80%, 69% and 70%, respectively, compared to controls (Fig. S3A–B). These findings were corroborated by immunostaining for the TJ protein ZO-1 (Fig. S3C–D) and the adherens junction protein VE-cadherin (Fig. S3E–F). Pericyte-deficient mice also exhibited reductions in the capillary basement membrane proteins collagen IV and vascular laminin, as shown by immunoblotting of the isolated brain microvessels (Fig. S3G–H), consistent with the role of pericytes in basement membrane formation (Diaz-Florez et al., 2009). In addition, accumulation of different endogenous macromolecules in brain endothelium of pericyte-deficient mice as shown for example for IgG (Fig. 3E–F) and fibrinogen/fibrin (Fig. 4E–F) might reflect enhanced bulk flow transcytosis which may also contribute to the observed BBB disruption.

To determine whether accumulation of blood-derived components in brain is primarily related to pericyte deficiency and not to perfusion stress, we studied mice with a single deletion of the mesenchyme homeobox gene-2 allele (Meox2+/−) exhibiting a significant perfusion deficit with 45–50% reductions in capillary density and resting CBF, respectively, as we reported (Wu et al., 2005), but with normal pericyte coverage of microvessels (Fig. S4A–B). In contrast to F7 or Pdgfrβ+/− mice, Meox2+/− mice at a comparable age did not show any extravascular IgG or fibrin deposits (Fig. S4C) and expressed normal levels of TJ proteins (Fig. S4D) in spite of significant (P < 0.05) 45% and 48% reductions in the microvascular length (Fig. S4E) and brain perfusion (not shown), as reported (Wu et al., 2005). Studies in Meox2+/− mice confirmed that the BBB breakdown in pericyte-deficient mice is not related to perfusion stress and is mediated by pericyte loss. Meox2+/− mice had normal arterial vascular reactivity and normal thickness of the vascular smooth muscle cells layer in the pial arteries (Wu et al., 2005) consistent with unaltered CBF responses to stimulation (Fig. S4F) further supporting that pericytes are required for hemodynamic responses to brain activation.

Dual fluorescent staining of lectin-positive endothelium and aquaporin 4 or α-syntrophin (SNTA1), markers of the astrocytic end-foot processes enwrapping brain microvessels, and glial fibrillary acidic protein (Zlokovic, 2008), failed to show changes in astrocyte coverage of microvessels and astrocyte number in pericyte-deficient mice, respectively (Fig. S5). These findings are consistent with earlier studies demonstrating that TJ formation at the BBB does not require contact with astrocyte foot processes on capillary surface and is not affected in areas lacking astrocytes (reviewed in Zlokovic, 2008).

Neurodegeneration and Impairments in Memory and Learning in Pericyte-Deficient Mice

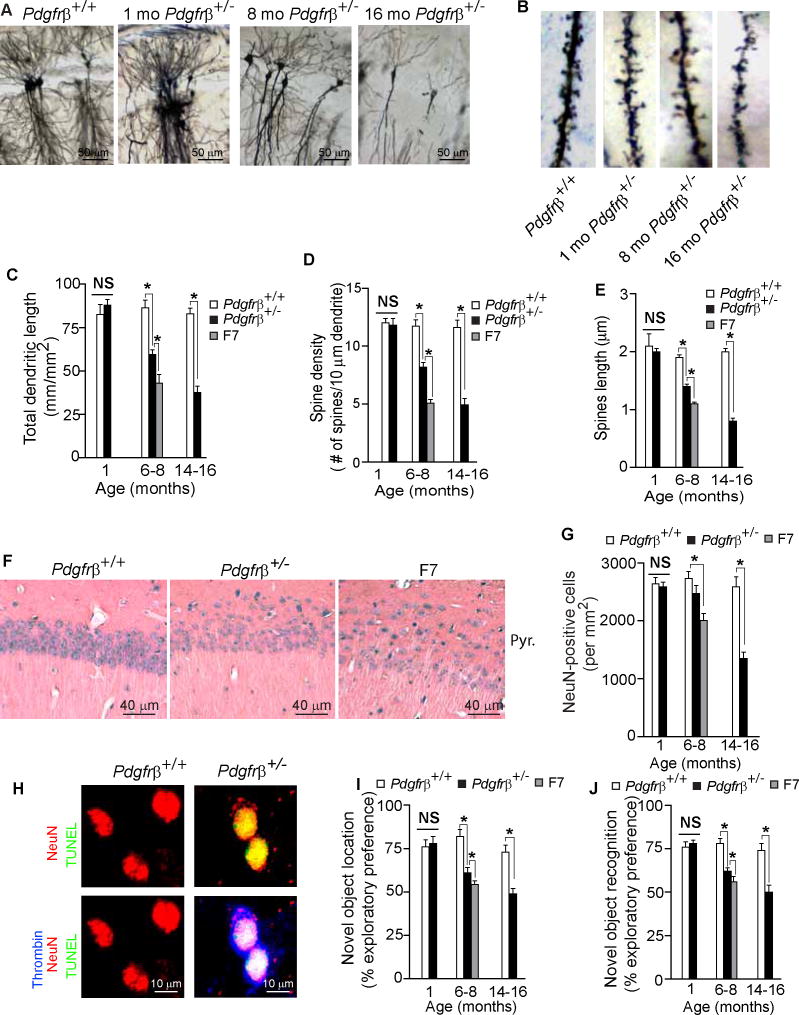

To determine whether loss of pericytes causing alterations in microvascular function and BBB integrity was sufficient to induce irreversible neuronal injury, we studied neuronal morphology and behavior.

Using Golgi-Cox staining we failed to detect any structural changes in neurons in the CA1 hippocampal region (or cortex, not shown) in 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (Fig. 6A–E). However, there was a significant age-dependent loss of dendritic length, spine density and spine length in the hippocampus of Pdgfrβ+/− mice at 6–8 and 14–16 months of age by 32, 30 and 18%, and 55, 58 and 56%, respectively (Fig. 6A–E). A comparison of 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice indicated significantly greater changes in neuronal morphology in the CA1 hippocampus region (Fig. 6C–E) and cortex (data not shown) in F7 mice.

Figure 6. Age-Dependent Neurodegeneration and Impairments in Memory and Learning in Pericyte-Deficient Mice.

(A–B) Low magnification bright-field microscopy analysis of Golgi-Cox staining of neurons (A) and high magnification bright-field microscopy images of dendritic spine density (B) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus of an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ control and 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice.

(C–E) Dendritic length (C), dendritic spine density (D) and spine length (E) of Golgi-Cox stained neurons in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in 1, 6–8, and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars) and control Pdgfrβ+/+ (white bars) mice, and 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bars). Total of 30 fields (500 × 375 μm) from 3 adjacent 100 μm thick sections were analyzed per mouse for dendritic length measurements. Total of 100 randomly selected dendrites from 3 adjacent 100 μm thick sections were analyzed per mouse for dendritic spine density measurements and for spine length quantification.

(F) Bright-field microscopy analysis of hemotoxylin and eosin staining of stratum pyramidale in the CA1 hippocampal region of 6 month old Pdgfrβ+/+, Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice.

(G) Quantification of NeuN-positive neurons in the stratum pyramidale of the CA1 hippocampal subfield in 1, 6–8, and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− (black bars) and control Pdgfrβ+/+ (white bars) mice, and 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bar). Total of 24 randomly chosen CA1 fields (420 × 420 μm) in the hippocampus were analyzed from 6 non-adjacent sections per mouse.

(H) Confocal microscopy analysis of TUNEL (green), NeuN-positive neuronal nuclei (red) and thrombin (blue) in the cortex of an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and control Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse.

(I–J) Novel object location (I) and novel object recognition (J) exploratory preference in 1, 6–8, and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars) and age-matched Pdgfrβ+/+ control mice (white bars) and in 6–8 month old F7 mice (gray bars). (See Fig. S6).

In C–E, G and I–J, mean ± s.e.m., n = 6–10 mice per group; *p<0.05 by one-way ANOVA. NS, non-significant.

Histological staining of the hippocampus CA1 stratum pyramidale indicated a moderate and substantial loss of neurons in 6 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice, respectively, compared to a control Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse (Fig. 6F). Counting of NeuN-positive neurons in the CA1 stratum pyramidale corroborated no loss in 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice, and 10% and 27% loss in 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice, respectively (Fig. 6G). Pdgfrβ+/− 14–16 month old mice had a significantly greater 48% loss of neurons in the CA1 region compared to controls (Fig. 6G). Confocal microscopy analysis for TUNEL, neuronal marker NeuN and thrombin in 6 month old and older Pdgfrβ+/− mice indicated sporadically a colocalization of the cytoplasmic thrombin accumulations and TUNEL-positive dying neurons, as illustrated in 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mouse compared to negative staining for TUNEL and thrombin in a control Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse (Fig. 6H).

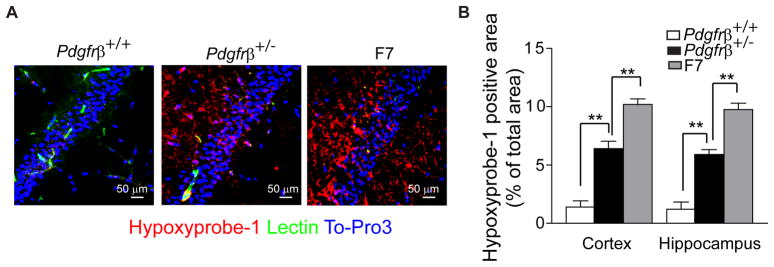

Using the Hypoxyprobe-1 (pimonidazole) we found that brains of 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice are hypoxic compared to control Pdgfrβ+/+ mice (Fig. 7A). The hypoxic area expressed as a percentage of total tissue area in the hippocampus and cortex was ~ 1.5% in control Pdgfrβ+/+ mice compared to 6–7% in Pdgfrβ+/− mice and 9–11% in F7 mutants (Fig. 7B). Chronic hypoxic changes in brain tissue likely aggravate neuronal injury, as shown in models of combined ischemic/hypoxic brain injury (Ten et al., 2004). No significant hypoxic changes were found in young pericyte-deficient mice (not shown). It is of note that the brains of pericyte-deficient mice were perfused with fully oxygenated arterial blood under normal arterial systolic/diastolic perfusion pressure (see below - Analysis of Systemic Parameters), suggesting brain hypoxic changes are related to reductions in brain microcirculation and CBF, rather than to systemic hemodynamic insufficiency.

Figure 7. Hypoxic Brain Tissue Changes in Pericyte-Deficient Mice.

(A) Confocal analysis of hypoxyprobe-1 (pimonidazole)-positive hypoxic (O2 <10 mm Hg) tissue in the hippocampus of 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+, Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice.

(B) Quantification of hypoxyprobe-1-positive area expressed as a percentage of total tissue area in the cortex and hippocampus of 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+, Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice. A total of 36 and 24 randomly chosen fields (420 × 420 μm) from 6 non-adjacent cortical and hippocampal sections, respectively, were analyzed per mouse. Mean ± s.e.m., n=6 mice per group; *p<0.05 or **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA. (See Fig. S7).

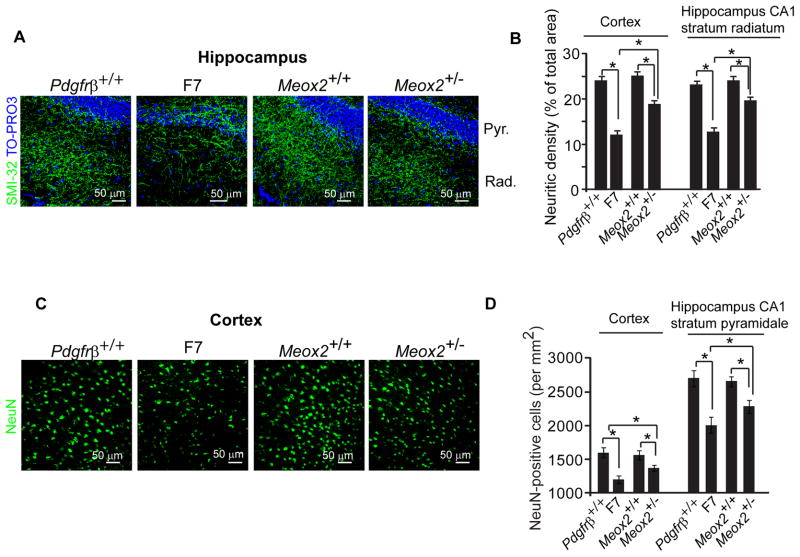

Notably, vascular injury is well established at the 1 month time point in the absence of neuronal changes, thereby suggesting that a primary vascular injury precedes neuronal injury at later time points in pericyte-deficient mice. Significantly, 6 month old Meox2+/− mice with an intact BBB (Fig. S4) but comparable microvascular reductions and perfusion stress (Wu et al.,2005) as pericyte-deficient F7 mice at the same age, showed a significant reduction in SMI-32-positive neuritic density in the hippocampus CA1 stratum radiatum and cortex and a significant loss of neurons from the hippocampus CA1 stratum pyramidale and cortex by 25% and 19%, and 13–14%, respectively, compared to the corresponding values in Meox2+/+ controls (Fig. 8A–D). However, neuronal changes in Meox2+/− mice were much less pronounced than the reduction in the neuritic length and neuronal loss seen in the same regions of F7 mice that were 50% and 46%, and 25–26%, respectively, of their corresponding controls (Fig. 8A–D). This data suggests that perfusion stress alone is sufficient to induce neuronal injury but may act in synergy with accumulated neurotoxins secondary to BBB breakdown to induce even greater injury, as evidenced by more severe neuronal changes in pericyte-deficient mouse models.

Figure 8. Neurodegenerative Changes in Meox2+/− and F7 Mice.

(A) Confocal microscopy analysis of SMI-32 immunodetection of neurites (green) and Topro3 nuclear staining (blue) in the hippocampus of 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and F7, and Meox2+/+ and Meox2+/− mice. Pyr., Stratum Pyramidale and Rad., Stratum Radiatum.

(B) Quantification of SMI-32 positive neurite density in the cortex and hippocampus of 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and F7, and Meox2+/+ and Meox2+/− mice.

(C) Confocal microscopy analysis of NeuN-positive neurons (green) in the cortex in 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and F7, and Meox2+/+ and Meox2+/− mice.

(D) Quantification of NeuN-positive neurons in the cortex and hippocampus CA1 stratum pyramidale of 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ and F7 mice, and Meox2+/+ and Meox2+/− mice.

In B and D, a total of 36 and 24 randomly chosen fields (420 × 420 μm) from 6 non-adjacent cortical and hippocampal sections, respectively, were analyzed per mouse. Mean ± s.e.m., n=6 mice per group; *p<0.05 or **p<0.01 by one-way ANOVA

Significantly, 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice did not show changes in hippocampal learning and spatial memory determined by novel object location (Mumby et al., 2002) (Fig. 6I) and the perirhinal cortex-mediated consolidation of novel object recognition memory (Winters and Bussy, 2005) (Fig. 6J), consistent with intact neuronal circuitries mediating these behavioral responses at the time point when these mice have accumulated significant vascular damage including BBB breakdown and perfusion deficit. In contrast, 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice had significant impairments on both tests (Fig. 6I–J). F7 mutants had worse performance on both tests compared to Pdgfrβ+/− mice (Fig. 6I–J).

To verify functional neuronal integrity in young Pdgfrβ+/− mice, we measured local field potentials (LFP) in layer II of the hind limb somatosensory cortex and blood flow responses following electrical stimulation of the hind limb. We did not find significant differences in the LFP amplitude curves in response to an increasing electrical stimulus, LFP peak amplitudes, time-to-peak values, and/or LFP signals integrated over the time period of activation (ΣLFP) between 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− and Pdgfrβ+/+ mice (Fig. S6A–F). On the other hand, there was a significant 23% diminished CBF response in the hind limb somatosensory cortex in 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice compared to controls (Fig. S6G), corroborating our finding showing reduced CBF response in young Pdgfrβ+/− mice after vibrissal stimulation (Fig. 2F).

Late Neuroinflammatory Response in Pericyte-Deficient Mice

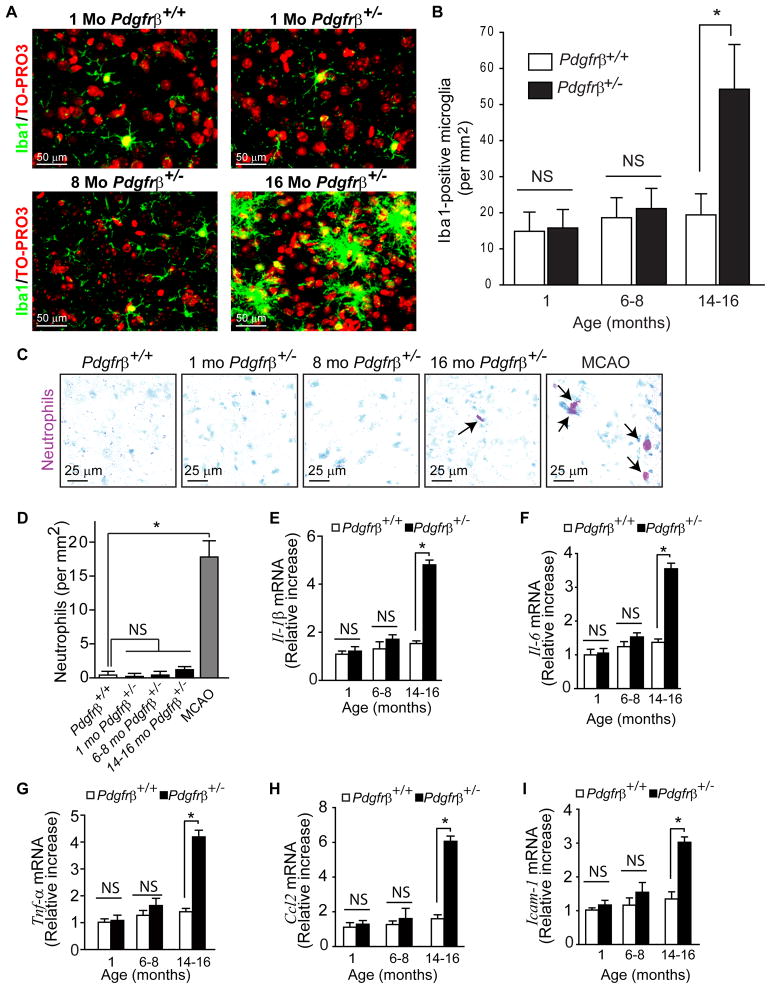

Finally, we studied the role of neuroinflammation. To determine whether the number of microglia is increased we have performed immunostaining for Iba1 (ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1) which has been used to study microglial cells in models of neurodegenerative diseases including superoxide-dismutase-1 mutant mice (Boillée et al., 2006) or microglial neurotoxicity (Cardona et al., 2006). Pdgfrβ+/− mice at 1 and 6–8 months did not show a significant neuroinflammatory response (Fig. 9). At 16 months of age, however, Pdgfrβ+/− mice had a significant 2.5-fold increase in the number of microglia displaying a larger ‘ameboid’ form with stubby processes suggestive of activated microglia compared to the ‘resting’ microglia with smaller bodies and thinner processes that were found in controls and 1 and 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (Fig. 9A–B). Specific staining for neutrophils (granulocytes) was negative in brains of 1 and 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice, and showed a non-significant increase to 1.2 neutrophils per mm2 in 16 month old mice (Fig. 9C–D). Consistent with microglia activation, 16 month old, but not 1 and 6–8 month old, Pdgfrβ+/− mice exhibited a significant (P < 0.05) increase in the expression of several inflammatory cytokines including interleukin 1β and 6, tumor necrosis factor-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Fig. 9E–I).

Figure 9. Late Neuroinflammatory Response in Pericyte-Deficient Mice.

(A) Confocal microscopy analysis of Iba1-positive microglia in the cerebral cortex of an 8 month old control Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse and 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice.

(B) The number of Iba1-positive microglia in the cortex of 1, 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice (black bars) and age-matched Pdgfrβ+/+ controls (white bars). Total of 36 randomly chosen fields (420 × 420 μm) from 6 non-adjacent cortical sections were analyzed per mouse.

(C) Bright-field microscopy analysis for neutrophils (red) using dichloracetate esterase staining in the cerebral cortex of an 8 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mouse and 1, 8 and 16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice. MCAO, a positive control showing neutrophils infiltration (arrows) of ischemic brain tissue of a Pdgfrβ+/+mouse 24 h after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO).

(D) The number of neutrophils in the cortex of 1, 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice and mice receiving the MCAO compared to control 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/+ mice.

(E–I) Real-time quantitative PCR for mouse interlukein-1 beta (Il-1β) (E) interlukein 6 (Il-6) (F) tumor necrosis factor alpha (Tnf-α) (G), chemokine C-C motif ligand 2 (Ccl2)(H) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (Icam-1) (I) mRNA in the cerebral cortex of 1, 6–8 and 14–16 month old Pdgfrβ+/− (black bars) and age-matched control Pdgfrβ+/+ (white bars) mice.

In B, D and E–I, mean ± s.e.m, n=4–6 mice per group; *p<0.05 by one-way ANOVA. NS, non-significant.

Analysis of Systemic Parameters

In all studied genotypes and ages we have measured hemodynamic and other physiologic parameters including: 1) mean arterial blood pressure from the femoral artery; 2) systolic and diastolic blood pressure; 3) pulse arterial pressure (difference between systolic and diastolic pressure); 4) heart rate; 5) arterial blood gases; 6) arterial pH; 7) serum and CSF glucose levels, and 8) respiration rate. In addition, we have determined in 6–8 month old mice in all genotypes (i.e., Pdgfrβ+/+, Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice): 9) liver analyses and 10) kidney analyses (see Fig. S7).

This data shows no statistical difference in any of the measured hemodynamic, physiological and/or biochemical parameters including tests for the liver and kidney functions between Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice compared to age-matched control Pdgfrβ+/+mice suggesting that pericyte-deficient mice do not have a general perfusion deficit and/or an apparent cardiovascular insufficiency. This indicates that brain perfusion deficits in these mice are mainly of local character.

DISCUSSION

We show that deficient PDGFRβ signaling results in pericyte degeneration in the adult and aging brain leading to reductions in brain microcirculation and BBB breakdown prior to neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation (Fig. 10). Although the mouse lines used in the present study were not pericyte-specific, changes in neuronal structure and function in the present pericyte-deficient models on a 129S1/Sv1mJ background cannot be explained by primary neuronal injury because PDGFRβ is not expressed in neurons in these mice (Winkler et al., 2010). Our findings are consistent with previous reports showing that 129SV/C57BL6 mice do not express PDGFRβ in neurons or other cell types within the neurovascular capillary unit, and that loss of PDGF-B/PDGFRβ signaling due to global PDGF-B and/or PDGFRβ knockouts results in vascular damage in the developing CNS mediated by pericyte loss, not neuronal loss (Lindahl et al., 1997; Hellstrom et al., 1999). Moreover, gene expression profiling on acutely isolated neurons from C57BL6 and C57BL6/DBA mice failed to detect Pdgfrβ expression (Cahoy et al., 2008; http://innateimmunity.mit.edu/cgi-bin/exonarraywebsite/plot_selector_cahoy.pl?exact=1&gene=Pdgfrb).

Figure 10. Vascular-Mediated Neurodegeneration Following Pericyte Loss.

PDGFRβ deficient signaling in brain pericytes leads to a progressive age-dependent pericyte loss resulting in (1) reductions in brain microcirculation with diminished cerebral blood flow (CBF) and CBF responses to a stimulus (CBF dysregulation) leading to a chronic perfusion stress and hypoxia, and (2) blood-brain barrier breakdown with accumulation of serum proteins and several cytotoxic and neurotoxic pathologic deposits in brain. Both, arms 1 and 2 may contribute to secondary neuronal injury and neurodegeneration mediated by a neurovascular insult.

Other studies have suggested that PDGFRβ is expressed in cultured neurons (Zheng et al., 2010) and in the brains of C57BL6 mice proposing that higher susceptibility of nestin-Cre+PDGFRβflox/flox mice to cryogenic injury is due to a selective neuronal vulnerability caused by Pdgfrβ deletion (Ishii et al., 2006). The source of the contradictions between these reports remains unclear. It is possible, however, these conflicting results may reflect genetic differences between mouse strains, consistent with strain-specific gene expression in the adult mouse CNS (Neuron, 1997; Sandberg et al., 2000). In addition, cultured neurons do not accurately represent the transcriptional profile of neurons in vivo (Tosh and Slack, 2002; Liu et al., 2007) or of acutely isolated non-cultured neurons (Cahoy et al., 2008). A recent finding that brain pericytes express nestin (Dore-Duffy et al., 2006) suggests nestin-Cre genetic manipulation likely deletes PDGFRβ from pericytes which complicates data interpretation in nestin-Cre+PDGFRβflox/flox mice (Ishii et al., 2006). The generation of pericyte-specific Pdgfrβ knockout mouse lines will be helpful to confirm that the neuronal phenotype caused by deficient PDGFRβ signaling depends on pericyte loss causing secondary vascular-mediated neurodegeneration, as suggested by the present models.

The threshold for pericyte loss required to trigger neurovascular dysfunction and/or neurodegeneration during brain aging could not be easily predicted based on earlier work. We show that a modest 20% loss in pericytes coverage can initiate vascular damage in 1 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice, as indicated by significant microvascular reductions and disruption of the BBB. This moderate reduction in pericyte coverage, however, did not produce neuronal damage. Somewhat greater, 40% loss in pericyte coverage in 6–8 month old Pdgfrβ+/− mice resulted in a profound neurovascular insufficiency, changes in neuronal structure and impairments in behavior. Moreover, Pdgfrβ+/− mice show a quantitative relationship between an age-dependent progressive pericyte loss and the reductions in brain capillary density, resting CBF and CBF responses to brain activation, and the BBB breakdown associated with brain accumulation of serum proteins and several potentially cytotoxic and/or neurotoxic macromolecules (e.g., fibrin, hemosiderin, thrombin, plasmin). Vascular, neuronal and behavioral changes were more pronounced in F7 mice expressing greater pericyte loss than Pdgfrβ+/− mice confirming a key role of pericytes in maintaining integrity of the neurovascular unit.

Our findings were quite unexpected given that loss of a single Pdgfrβ allele does not result in an apparent vascular phenotype or CNS defects in the developing CNS (Leveen et 1994; Soriano 1994; Lindahl et al., 1997; Tallquist et al., 2003), and that pericytes in the embryonic CNS do not regulate microvessel density and length, but are involved in the regulation of endothelial cell number and microvessel architecture (Lindahl et al., 1997; Hellstrom et al., 1999; Hellström et al., 2001). Although, our data suggests that pericytes may fulfill a different regulatory role with respect to the brain microcirculation during postnatal development, adulthood, and during the aging process than previously observed during prenatal embryonic development, the exact contribution of embryonic pericyte loss to the observed phenotype is presently unknown. An inducible Cre-loxP-Pdgrfβ, or Pdgfrβ promoter-dipthera toxin construct, and/or a pericyte-specific genetic model with post-natal Pdgfrβ deletion with either one being induced in the adult life, may help address: (i) whether loss of pericytes early in the developing CNS (as shown by Tallquist et al., 2003) evolves exponentially over time and becomes the primary force driving the loss of CNS microvascular homeostasis; and (ii) whether there is a major difference in the response of the embryonic CNS vs. the adult and aging brain to pericyte loss. The feasibility of creating mouse lines with inducible deletion of Pdgfrβ gene to address the above questions remains to be determined by the future studies.

Deficient PDGF-B/PDGFRβ signaling has been shown to initiate pericyte apoptosis leading to vascular regression in animal models of diabetic retinopathy (Geraldes et al., 2009) and tumors (Song et al., 2005). Cellular accumulation of different toxins such as oxidized glycated low density lipoproteins (Diffley et al., 2009), amyloid beta-peptide (Wilhelmus et al., 2007) or advanced glycation end products (Alikhani et al., 2010) can also trigger pericyte apoptosis as shown in pericyte cultures. We show now that a deficient PDGFRβ signaling in the adult and aging brain in Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice leads to pericyte-specific insult and apoptosis resulting in microvascular degeneration. Although the mechanism of age-dependent vascular pruning in pericyte deficient mice is unknown, it may reflect a loss of pericyte-derived trophic support including vascular endothelial growth factor (Bondjers et al., 2006). The observed cellular accumulation of serum proteins and cytotoxic macromolecules likely accelerates pericyte degeneration, consistent with in vitro studies.

The exact contributions of perfusion stress and BBB disruption to the development of neurodegenerative changes is not well understood at present. Our study in Meox2+/− mice with normal pericyte coverage and an intact BBB, but with a substantial perfusion deficit (Wu et al., 2005) comparable to that as in pericyte-deficient mice, has shown less pronounced changes in neuronal structure than in pericyte-deficient mice indicating that chronic perfusion alone can cause neuronal injury, but not to the extent when combined with the BBB breakdown. Recent findings have suggested that cultured human brain pericytes express low, but comparable levels of neurotrophic factors as cultured astrocytes (Shimizu et al., 2010). Given that the expression and role of pericyte-derived neurotrophic factors in brain in vivo have not been demonstrated and that pericytes do not make direct contacts with neurons (in contrast to astrocytes) (Zlokovic, 2008), it is unclear at present whether pericyte degeneration can increase neuronal susceptibility to injury through diminished neurotrophic support.

Perfusion stress and BBB compromise have been associated with neurodegenerative disorders (Zlokovic, 2008), as in Alzheimer’s disease (Iadecola et al., 1999; Deane et al., 2003; Chow et al., 2007; Bell et al., 2009) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Zhong et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2009; Rule et al., 2010). Our work in progress shows that a pericyte-restricted pattern of PDGFRβ expression is associated with pericyte loss in Alzheimer’s disease (Winkler, Bell and Zlokovic, unpublished observations) indicating that pericyte-deficient mice could potentially be used to study the role of brain pericytes in the development of human neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease or amytrophic lateral sclerosis. A temporal sequence of events in the present study suggests that degeneration of vascular pericytes can initiate circulatory insufficiency and BBB disruption first, that is followed by secondary neurodegenerative changes. This new vascular concept of neurodegeneration could have broader implications for our understanding of neurological disorders and might guide new therapeutic approaches directed at brain pericytes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 mice were generated as previously described (Tallquist et al., 2003) and kindly provided by Dr. Philippe Soriano. For the Pdgfrβ+/− mice a PGKneobpA expression cassette was used to replace a 1.8-kb genomic SmaI-EcoRV fragment spanning sequences coding for the signal peptide to the second immunoglobulin domain of PDGFRβ. The F7 mice were generated by point mutations that disrupt the following residues and designated signal transduction pathways; residue 578 (Src), residue 715 (Grb2), residues 739 and 750 (PI3K), residue 770 (RasGAP), residue 1008 (SHP-2), by changing the tyrosine to phenylalanine, and residue 1020 PLCγ, in which the tyrosine was mutated to encode an isoleucine. The Pdgfrβ+/− and F7 embryos have a significant 35–40% and 55–75%, respectively, reduction in pericytes in the neural tube at the level of heart and kidney in coronal sections at E14.5 (Tallquist et al., 2003). Meox2+/− mice were generated as we previously described (Wu et al., 2005). All mice were maintained on a 129S1/SvlmJ background and were shown to express PDGFRβ in brain exclusively in pericytes (Winkler et al., 2010). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Rochester using National Institute of Health guidelines.

Tissue Immunofluorescent and Fluorescent Lectin Staining

Mice were anesthetized intraperitoneally with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine and transcardially perfused with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) containing 5 U/ml heparin. Brains were dissected and embedded into O.C.T. compound (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA) on dry ice. O.C.T-embedded fresh frozen brain tissue sections were cryosectioned at a thickness of 14–18 μm and subsequently fixed in ice cold acetone. Sections were blocked with 5% normal swine serum (Vector Laboratories) for 60 min and incubated in primary antibody diluted in blocked solution overnight at 4° C. Sections were washed in PBS and incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. To visualize brain microvessels in specified experiments, sections were also incubated with biotin- or fluorescein-conjugated Lycopersicon esculentum lectin (Vector Laboratories). Sections were subsequently coverslipped with fluorescent mounting medium (Dako). For a detailed description of all primary antibodies, secondary antibodies and lectins used for detection of pericytes (PDGFRβ, NG2 and desmin), endothelial cells (CD31, lectin), neurons (SMI-32 and NeuN), microglia (Iba1), astrocytes (AQP4, α-syntrophin, GFAP), and other proteins (IgG, fibrin, thrombin, plasmin, laminin) please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)

Paraformaldhyde-fixed, paraffin embedded brain tissue sections were sectioned at a thickness of 7 μm. Immuofluorescent detection of pericytes (PDGFRβ) or neurons (NeuN) and/or endothelial-specific lectin fluorescent detection was conducted as described above. The DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega) was then completed as described by the manufacturer. Sections were coverslipped as described above.

Confocal Microscopy Analysis

All coverslipped fluorescently mounted tissue sections were scanned using a custom built Zeiss 510 meta confocal laser scanning microscope with a Zeiss Apochromat 25x/0.8 NA or C-Apochromat 40x/1.2 NA water immersion objective (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc.) For a detailed description of the laser wave lengths and band pass filters utilized to detect specified fluorophores please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Quantitative image analysis including desmin-positive pericyte coverage, NG2-positive pericyte number, lectin-positive capillary length, CD31-positive capillary length, fluorescent intensity analysis of extravascular IgG and fibrin accumulation, aquaporin-4-positive or α-syntrophin-positive astrocyte end-foot coverage, hypoxyprobe-1 positive hypoxic tissue, SMI-32-positive neuritic density and counting of GFAP-positive astrocytes, NeuN-positive neurons and Iba1-positive microglia was performed by blinded investigators using the NIH Image J software. For a detailed description of each analysis please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Bright-field Microscopy Analysis

Imaging and quantification of hematoxylin and eosin stained sections, Prussian-blue positive extravascular hemosiderin deposits, neuronal Golgi-Cox staining for determination of dendritic length and dendritic spine density and length, Iba1-positive microglia and neutrophil-specific dichloracetate esterase staining was conducted using an Olympus AX70 bright-field microscope and the NIH Image J software, respectively. For a detailed description of each technique and subsequent analysis, where applicable, please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Multiphoton In Vivo Microscopy Analysis

In vivo multiphoton experiments were performed as we previously described (Bell et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2010). Mice were anesthetized intraperitoneally with 750 mg/kg urethane and 50 mg/kg chloralose. A cranial window was placed over the parietal cortex. Imaging was completed within 40 min prior to any significant inflammation or gliosis are present. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details. All images were acquired using a custom built Zeiss 5MP multiphoton microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc.) coupled to a 900 nm mode-locked femtosecond pulsed DeepSee Ti:Sapphire laser (Spectra-physics, Newport corporation) with a Zeiss 20x/1.0 M27 W dipping objective. The 900 nm multiphoton laser excited fluorescein or TMR and the emission was collected using a 500–550 nm or 560–615 nm band pass filter, respectively.

Perfused Capillary Length

Fluorescein-conjugated mega-dextran (2,000,000 Da, Invitrogen, 0.1 ml of 10 mg/ml) was injected via the left femoral vein. Multiphoton z-stack images were immediately taken through the cranial window starting at 50 μm below the cortical brain surface continuing to scan 500 μm deep through cortical layers II and III with a 1 μm interval in between each image acquisition. Z-stacks were maximally projected and reconstructed using ZEN software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc.). The perfused capillary length was analyzed using the NIH Image J software. For detailed description of the analysis and rationale of using single time point analysis please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

BBB permeability

Cortical cerebrovascular permeability was determined using rapid in vivo multiphoton microscopy imaging as we previously described (Zhu et al., 2010). In brief, TMR-conjugated medium size dextran (40,000 Da, Invitrogen, 0.1 mL of 10 mg/ml) was injected via the left femoral vein. In vivo time-lapse images were acquired every 2 min for a total of 30 min. All images were subjected to threshold processing and the extravascular fluorescent intensity was measured using the integrated density measurement function by a blinded investigator. The in vivo BBB permeability for TMR-dextran was estimated as the PS product as we previously described (Deane et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2010) using the following formula: PS = (1−Hct) 1/Iv × V × dIt/dt, where Hct is the hematocrit (45%), Iv is the initial fluorescence intensity of the region of interest (ROI) within the vessel, It is the intensity of the ROI within the brain at time t, V is the vessel volume, and assuming 1 gram of brain is equivalent to 50 cm2. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Non-invasive Fluorometric BBB Permeability Measurements

The BBB permeability to different size tracers including TMR-dextran (MW=40,000 Da; Invitrogen), Cy3-IgG (MW=150,000 Da; Invitrogen), FITC-dextran (MW=500,000 Da; Sigma) and Fluorescein-mega-dextran (MW=2,000,000 Da; Invitrogen) was assessed in the cortex and hippocampus of anesthetized mice (100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine, intraperitoneally) using a non-invasive fluorometric technique. In brief, these tracers were injected intravenously via the femoral vein and blood and brain samples were collected within 30 min. Plasma samples and homogenized brain regions were analyzed using a fluorometric plate reader (Victor) to determine tracer concentration. The BBB PS product (ml/g/min) was calculated using the equation as we described (Mackic et al., 1998): PS = Cb/(0∫TCpxT), where Cb and 0∫TCp are the fluorescent tracer concentration in brain (per g) and integrated plasma concentration (per ml), respectively, and T is experimental time. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Quantitative 14C-iodoantipyrine autoradiography

Mice were anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane in 30% oxygen/70% nitrous oxide. Local CBF was measured by using intraperitoneal injection of radiolabeled 14C-iodoantipyrine (IAP) and a single blood sampling from the heart at the end of the experiment, as we previously described (Zhong et al., 2008). Blood flow, F (ml/100g/min) was calculated by using the equation, as we described (Zhong et al., 2008): F = λ/T ln (1− CI(T)/λ 0∫T CA(T), where CI(T) is 14C-IAP radioactivity (d.p.m.)/gram of brain tissue; T is the experimental time in seconds; CA(T) is 14C-IAP radioactivity (d.p.m.)/gram plasma determined as 14C-IAP integrated plasma concentration (0∫T) from 14C-tracer lag time after 14C-IAP i.p. injection (zero time) to the value measured in the blood sample from the frozen heart at the end of the experiment (at time T), by assuming a linear rise or ramp function over T; λ is 14C-IAP central nervous system tissue to blood partition coefficient, 0.8 ml/g. Arterial blood pressure, pH and blood gases were monitored before 14C-IAP administration. There were no significant changes in these physiological parameters between Pdgfrβ+/− or F7 mutants compared to Pdgfrβ+/+ control mice. See for details Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Laser-Doppler flowmetry

CBF responses to vibrissal stimulation in anesthetized mice (750 mg/kg urethane and 50 mg/kg chloralose) were determined using laser-Doppler flowmetry, as previously described (Iadecola et al.,1999; Chow et al., 2007, Bell et al., 2009). The tip of the laser-Doppler probe (Transonic Systems Inc.,) was stereotaxically placed 0.5 mm above the dura of the cranial window. The right vibrissae was cut to about 5 mm and stimulated by gentle stroking at 3–4 Hz, for 1 min with a cotton-tip applicator. The percentage increase in CBF due to vibrissal stimulation was obtained from the baseline CBF and stable maximum plateau, and averaged for the three trials. Arterial blood pressure was monitored continuously during experiment. pH and blood gases were monitored before and after CBF recordings. No significant changes in these physiological parameters were found between different genotypes and ages. In a separate set of experiments CBF responses were determined in the somatosensory cortex hindlimb region following electrical stimulation of the hindlimb using a 2 mA 0.5 second long stimulus.

Immunoblotting analysis

Isolated brain capillaries and capillary-depleted brains were prepared as we previously described. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details. Immunoblotting studies for the tight junction proteins (ZO-1, occludin and claudin-5) and vascular basement membrane proteins (laminin, collagen IV) in brain capillary homogenates and for blood-derived plasma proteins (thrombin, plasmin) in capillary-depleted brain homogenates were performed using primary antibodies as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. The relative abundance of studied proteins in microvessels and capillary-depleted brains was determined using scanning densitometry and β-actin as a loading control.

Behavior

Mice were subjected to novel object location and recognition behavioral tests. The novel object location and recognition tests were performed as previously described (Mumby et al., 2002; Winters and Bussy, 2005). For a detailed description please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Electrophysiologic Recordings

In vivo, extracellular electrophysiologic recordings were carried out in urethane anesthetized mice to quantify local field potential (LFP) amplitude, time-to-peak values, and LFP signals integrated over the time period of activation (ΣLFP) in layer II of the hindlimb somatosensory cortex following electrical stimulation of the contralateral hindlimb. For a detailed description please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Neuroinflammation

In addition to quantifying Iba1-positive microglia and neutrophil-specific dichloracetate esterase staining, we analyzed relative abundance of several neuroinflammatory cytokines/chemokines through quantitative real-time PCR using RNA isolated from snap-frozen brain samples as we previously described (Zhong et al., 2009). Gene expression was normalized to the house-keeping gene Gapdh. For cytokines/chemokines primer sequences please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Systemic Parameters

We have performed measurements of several hemodynamic, physiological and biochemical parameters including tests for the liver and kidney functions. For a detailed description please refer to Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by multifactorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey posthoc tests and Pearson’s correlation analysis. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NIH grants R37AG023084 and R37NS34467 to BVZ. We thank Dr. Philippe Soriano for providing the breeding pairs for Pdgfrβ+/− mice and the F7 mutants, Dr. Michelle Tallquist for providing brain tissue from xLacZ4 transgenic mice, Rachal Love for assisting with experiments in Meox2+/− mice and Theresa Barrett for assisting with Golgi-Cox imaging. We thank Dr. Maiken Nedergaard for letting us use her electophysiologic equipment for local field potential measurements, Dr. Karl Kasischke for assistance in measurements of blood flow responses to electrical hind limb stimulation, and Dr. Harris Gelbard and Daniel Marker for reviewing electrophysiological data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alikhani M, Roy S, Graves DT. FOXO1 plays an essential role in apoptosis of retinal pericytes. Mol Vis. 2010;16:408–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res. 2005;97:512–523. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer HC, Bauer H, Lametschwandtner A, Amberger A, Ruiz P, Steiner M. Neovascularization and the appearance of morphological characteristics of the blood-brain barrier in the embryonic mouse central nervous system. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;75:269–278. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Deane R, Chow N, Long X, Sagare A, Singh I, Streb JW, Guo H, Rubio A, Van Nostrand W, Miano JM, Zlokovic BV. SRF and myocardin regulate LRP-mediated amyloid-beta clearance in brain vascular cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:143–153. doi: 10.1038/ncb1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boillee S, Yamanaka K, Lobsiger CS, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kassiotis G, Kollias G, Cleveland DW. Onset and progression in inherited ALS determined by motor neurons and microglia. Science. 2006;312:1389–1392. doi: 10.1126/science.1123511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS, Xing Y, Lubischer JL, Krieg PA, Krupenko SA, Thompson WJ, Barres BA. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona AE, Pioro EP, Sasse ME, Kostenko V, Cardona SM, Dijkstra IM, Huang D, Kidd G, Dombrowski S, Dutta R, et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:917–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Cheng Q, Yang K, Lyden PD. Thrombin Mediates Severe Neurovascular Injury During Ischemia. Stroke. 2010 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZL, Strickland S. Neuronal death in the hippocampus is promoted by plasmin-catalyzed degradation of laminin. Cell. 1997;91:917–925. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow N, Bell RD, Deane R, Streb JW, Chen J, Brooks A, Van Nostrand W, Miano JM, Zlokovic BV. Serum response factor and myocardin mediate arterial hypercontractility and cerebral blood flow dysregulation in Alzheimer’s phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:823–828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608251104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, Welch D, Manness L, Lin C, Yu J, Zhu H, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Stern A, Schmidt AM, Armstrong DL, Arnold B, Liliensiek B, Nawroth P, Hofman F, Kindy M, Stern D, Zlokovic B. RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. 2003;9:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nm890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Flores L, Gutiérrez R, Madrid JF, Varela H, Valladares F, Acosta E, Martín-Vasallo P, Díaz-Flores L., Jr Pericytes. Morphofunction, interactions and pathology in a quiescent and activated mesenchymal cell niche. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24:909–969. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffley JM, Wu M, Sohn M, Song W, Hammad SM, Lyons TJ. Apoptosis induction by oxidized glycated LDL in human retinal capillary pericytes is independent of activation of MAPK signaling pathways. Mol Vis. 2009;15:135–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P, Katychev A, Wang X, Van Buren E. CNS microvascular pericytes exhibit multipotential stem cell activity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:613–624. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enge M, Bjarnegård M, Gerhardt H, Gustafsson E, Kalén M, Asker N, Hammes HP, Shani M, Fässler R, Betsholtz C. Endothelium-specific platelet-derived growth factor-B ablation mimics diabetic retinopathy. EMBO J. 2002;21:4307–4316. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaengel K, Genové G, Armulik A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial-mural cell signaling in vascular development and angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:630–638. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraldes P, Hiraoka-Yamamoto J, Matsumoto M, Clermont A, Leitges M, Marette A, Aiello LP, Kern TS, King GL. Activation of PKC-delta and SHP-1 by hyperglycemia causes vascular cell apoptosis and diabetic retinopathy. Nat Med. 2009;15:1298–1306. doi: 10.1038/nm.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes HP, Lin J, Renner O, Shani M, Lundqvist A, Betsholtz C, Brownlee M, Deutsch U. Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2002;51:3107–3112. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström M, Gerhardt H, Kalén M, Li X, Eriksson U, Wolburg H, Betsholtz C. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;30:543–553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström M, Kalén M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:3047–3055. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, Beck LH, Smith SR, D’Amore PA. Endothelial cells modulate the proliferation of mural cell precursors via platelet-derived growth factor-BB and heterotypic cell contact. Circ Res. 1999;84:298–305. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. The overlap between neurodegenerative and vascular factors in the pathogenesis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:287–296. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Zhang F, Niwa K, Eckman C, Turner SK, Fischer E, Younkin S, Borchelt DR, Hsiao KK, Carlson GA. SOD1 rescues cerebral endothelial dysfunction in mice overexpressing amyloid precursor protein. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:157–161. doi: 10.1038/5715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Oya T, Zheng L, Gao Z, Kawaguchi M, Sabit H, Matsushima T, Tokunaga A, Ishizawa S, Hori E, Nabeshima Y, Sasaoka T, Fujimori T, Mori H, Sasahara M. Mouse brains deficient in neuronal PDGF receptor-beta develop normally but are vulnerable to injury. J Neurochem. 2006;98:588–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E, Li L, Cunningham LA. Angiogenic recruitment of pericytes from bone marrow after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:545–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kröll S, El-Gindi J, Thanabalasundaram G, Panpumthong P, Schrot S, Hartmann C, Galla HJ. Control of the blood-brain barrier by glucocorticoids and the cells of the neurovascular unit. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1165:228–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrin F, Srun S, Raymond K, Martin S, van den Brink S, Freitas C, Bréant C, Mathivet T, Larrivée B, Thomas JL, Arthur HM, Westermann CJ, Disch F, Mager JJ, Snijder RJ, Eichmann A, Mummery CL. Thalidomide stimulates vessel maturation and reduces epistaxis in individuals with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nat Med. 2010;16:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nm.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levéen P, Pekny M, Gebre-Medhin S, Swolin B, Larsson E, Betsholtz C. Mice deficient for PDGF B show renal, cardiovascular, and hematological abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1875–1887. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Levéen P, Betsholtz C. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science. 1997;277:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom P, Gerhardt H, Liebner S, Abramsson A, Enge M, Hellstrom M, Backstrom G, Fredriksson S, Landegren U, Nystrom HC, et al. Endothelial PDGF-B retention is required for proper investment of pericytes in the microvessel wall. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1835–1840. doi: 10.1101/gad.266803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]