Abstract

The opening of specific segments of DNA is required for most types of genetic readout, including σ70-dependent transcription. To learn how this occurs, a series of single point mutations were introduced into σ70 region 2. These were assayed for duplex DNA binding, DNA opening and DNA double strand–single strand fork junction binding. Band shift assays for closed complex formation implicated a series of arginine and aromatic residues within a minimal 26 amino acid region. Permanganate assays implicated two additional aromatic residues in DNA opening, known to form a parallel stack of the type that can accept a flipped-out base. Substitution for either of these aromatics had no effect on duplex probe recognition. However, when a single unpaired –11 nucleotide is added to the probe, the mutants fail to bind appropriately to give heparin resistance. A model for DNA opening is presented in which duplex recognition by regions 2.3, 2.4 and 2.5 of sigma positions the pair of aromatic amino acids, which then create the fork junction required for stable opening.

Keywords: Escherichia coli/fork junction/promoter/σ70

Introduction

Escherichia coli transcription is accomplished by multi-subunit RNA polymerase holoenzymes. Each contains an exchangeable sigma subunit associated with a common core. The sigma subunit has the DNA recognition determinants and directs the holoenzyme to appropriate promoters by binding to unique DNA sequences. The most common sigma is σ70, which transcribes most of the cellular RNA.

Promoters recognized by σ70 and related holoenzymes typically contain recognition elements near positions –10 and –35 (Hawley and McClure, 1983). Consensus sequences have been derived, but promoters do not match this consensus exactly and many diverge very substantially. Promoter mutations most commonly map to these elements, confirming their primary importance. Other nearby DNA sequences also contribute to promoter recognition (Keilty and Rosenberg, 1987; Ross et al., 1993).

Despite the importance of these –10 and –35 sequences, their precise mechanistic role is uncertain, particularly with regard to the –10 element, which contains the most conserved nucleotides within promoters. The uncertainty exists because the –10 element is required to change structure during transcription, i.e. it is largely converted from the double-stranded to the single-stranded state as part of the polymerase-driven formation of a functional open complex. During this conversion, there appears to be recognition of duplex and single-stranded DNA (Roberts and Roberts, 1996), and of the distinctive fork junction at the upstream boundary between these two (Guo and Gralla, 1998; Guo et al., 1999). It is not clear how each nucleotide within the –10 element is recognized and in which state this recognition occurs.

Various studies have shown that the C–terminal part of conserved region 2 (regions 2.3, 2.4 and 2.5) of σ70 is involved in the use of the –10 region and adjacent DNA sequences. Suppression analysis has implicated amino acids 441, 440 and 437 (in region 2.4) in the recognition of nucleotides –13 and –12 (Kenney et al., 1989; Siegele et al., 1989; Zuber et al., 1989; Daniels et al., 1990; Waldburger et al., 1990; Marr and Roberts, 1997) and amino acids C–terminal to position 454 (in region 2.5) in the recognition of nucleotides from –14 to –20 (Barne et al., 1997; Bown et al., 1999). These amino acids are believed to be involved in double strand recognition, although direct evidence is lacking in the case of 437 and 440. Permanganate probing and single strand binding studies have implicated a series of aromatic residues (all or a subset of 425, 430, 433 and 434 in region 2.3) as potentially involved in the opening of the DNA, most probably via recognition of the non-template strand (Juang and Helmann, 1994; Huang et al., 1997; Marr and Roberts, 1997). Some of these studies used components from Bacillus subtilis, which creates uncertainty as its polymerase does not form open complexes that resist heparin treatment (Huang et al., 1997). These various studies generally are combined into a model in which the segment C–terminal to 436 (mostly region 2.4) recognizes double-stranded DNA, and the adjacent N–terminal segment (mostly region 2.3) is involved in DNA melting (Helmann and deHaseth, 1999).

The determination of how a region of DNA is recognized and then opened has implications well beyond this σ70 system. Similar processes must occur at all promoters, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic, and during DNA replication and repair. It is not yet known whether there are common modes of recognition that occur during the initial recognition and subsequent opening of DNA segments that must be melted in order to function. In terms of this recognition, the σ70 system is quite advanced as it includes a crystallographic structure for most of region 2 (Malhotra et al., 1996). For these reasons, we systematically have mutated likely targets in regions 2.3 and 2.4 of σ70 and applied a battery of tests for DNA binding and melting. The results lead to a fairly simple model that incorporates aspects of current proposals but also is different in important ways.

Results

Core polymerase binding by sigma mutants

Mutations were introduced into selected amino acids of the σ70 region that is involved in recognition of the downstream –10 region element. Positions were selected within the likely outer limits of helix 14 as identified in the crystal structure (Malhotra et al., 1996). The C–terminal limit was beyond the known structure and just before Pro453. The N–terminal edge was the aromatic residue 425, just beyond the known limit of the helix. Based on prior proposals, all aromatics in region 2.3 (which reaches to 434) were investigated and changed individually to alanines. Prior experiments have implicated hydrophilic residues in region 2.4 (Q437, T440 and R441) as being involved in double-stranded DNA recognition (see Introduction); however, the region between 442 and 453 has been largely unstudied. Thus, almost all hydrophilic amino acids within this region were mutated. These mutations were to serine in order to maintain fully the hydrophilic character of the side chains. As controls, additional serine substitutions were made in selected isoleucines and in the single lysine (K426). In aggregate, 18 of the 28 residues were altered. Collectively, the 10 non-targeted residues were either I, A, S or T. The 18 mutant sigmas were purified in parallel with wild type using a common protocol.

These sigmas were tested for the ability to form stable complexes with core RNA polymerase. No core-binding mutants have been detected within the segment, although an adjacent proline was detected in a screen (Sharp et al., 1999). Therefore, complex formation would be expected except in the case of misfolded proteins. In order to obtain a measure of complex half-lives, we used surface plasmon resonance (SPR; Biacore) to monitor complex formation. Each sigma contained a His6 tag that should mediate its attachment to a Biacore nickel chip. Sixteen of the 18 mutant proteins assayed were able to bind to this chip at levels comparable to wild type. The two exceptions were mutants I450S and I452S. Both showed very low levels of binding and were dissociated rapidly upon chase. The contrast with the other 17 proteins suggested that these two mutants were misfolded and that their histidine tag was inaccessible, consistent with the drastic nature of the I to S substitution. These two mutants also did not show activity in DNA-binding assays (below and data not shown) and are not considered further.

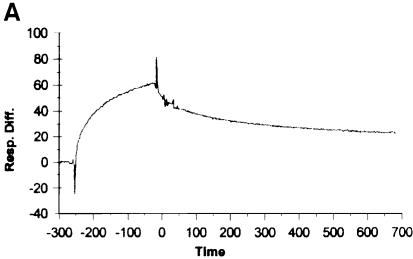

Wild-type and the other 16 proteins were each bound to the nickel chip and then saturated with core RNA polymerase. Levels of binding were roughly comparable for all sigmas. The excess core polymerase was removed and the complex was chased by flowing buffer solution over the chip. The dissociation of the core polymerase was then followed at subsequent times. A sample sensogram showing the progress of the binding and dissociation is given in Figure 1A. Semi-log plots (Figure 1B) were obtained from the dissociation data. All mutants, including ones with dissociation rates indistinguishable from wild type (F427A, shown by triangles) and those with defects (T440S, shown by filled circles), gave the expected linear semi-log plots. The half-lives for all proteins were calculated (11 min for wild-type under the conditions of the experiment) and are presented in Table I.

Fig. 1. Stability of holoenzymes using SPR. (A) A sensogram trace, indicating the initial binding of core to the sigma-saturated chip (prior to time zero) and the subsequent dissociation after beginning the chase at time zero. (B) The fraction of core remaining bound (FB) at each time was determined from the loss of signal response units. Semi-log plots of core dissociation are shown for wild-type sigma (♦), F427A (▴) and T440S (•). Half-lives were calculated from –ln2/slope.

Table I. The half-lives of the mutant sigmas in holoenzymes are compared with wild type.

| Mutation | Half-life (min) |

|---|---|

| Y425A | 12 |

| K426S | 4 |

| F427A | 12 |

| Y430A | 9 |

| W433A | 6 |

| W434A | 6 |

| R436S | 5 |

| Q437S | 9 |

| T440S | 2 |

| R441S | 12 |

| I443S | 2 |

| D445S | 6 |

| Q446S | 5 |

| R448S | 11 |

| T449S | 4 |

| I450S | X |

| R451S | 12 |

| I452S | X |

| Wild-type | 11 |

The two mutants I450S and I452S were unable to bind the nickel chip and their half-lives are designated with an X. Each experiment was carried out 3–5 times and the error was less than ±20%.

With two exceptions, the mutant holoenzymes exhibited half-lives within a factor of 3 of the wild-type value of 11 min. The exceptions were the third drastic (I to S) substitution (I443S) and a more conservative change from T to S (T440S), which, nonetheless, were stable for 2 min when chased. In fact, neither T440S nor I443S showed a severe defect in DNA-binding assays (shown below), suggesting that even the least stable mutant holoenzymes were not so unstable as to lessen DNA binding. All other holoenzymes were more stable, with half-lives of at least 4 min when chased. We expect these half-lives to be even longer when bound to DNA, as in the experiments below. No substitutions within this segment were obtained in a recent screen for core-binding mutants (Sharp et al., 1999). Thus, it is not surprising that these substitutions have only minor effects on the stability of the core–sigma complex.

Double strand binding to two promoters

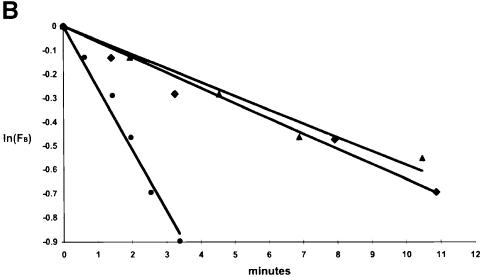

We tested the ability of these sigmas to bind promoter DNA in duplex form by the use of a band shift assay (electrophoresis mobility shift assay, EMSA). Labeled duplex probes were prepared corresponding to promoter sequences from –41 to +1. These contain the –35 and –10 recognition elements but lack the initial transcribed region that can enhance binding non-specifically. The probes were incubated with holoenzymes and subject to electrophoresis. The incubation and electrophoresis were carried out at <4°C in order to keep the duplex intact. Two different, well characterized promoters were used: lac UV5 and lambda PR′. Figure 2A shows the results of EMSA on the lac UV5 probe. The two left-most lanes in each panel show the result with and without wild-type sigma. The lower band without sigma represents core polymerase binding non-specifically to the probe. The addition of sigma leads to the appearance of the upper band corresponding to the binding of the holoenzyme. Unbound probe was run off the gel and the extent of binding in each experiment was determined in parallel control experiments (see quantitation in the legend to this and subsequent EMSA experiments).

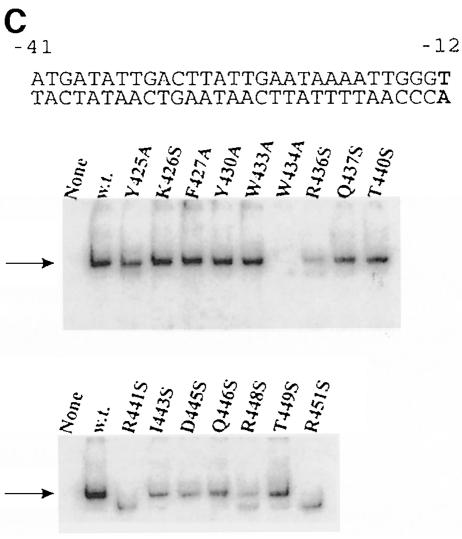

Fig. 2. EMSA of holoenzymes with mutant sigmas on three duplex DNA structures. The sequence of each labeled probe is at the top, with –10 element nucleotides shown in bold. The arrow shows the position of holoenzyme binding using the form of sigma indicated above the autoradiogram. ‘None’ has no sigma. Core is always limiting so the lower core-binding band appears to include a contribution from free forms of core present in holoenzyme preparations. (A) The lacUV5 probe from –41 to +1. In typical experiments, wild-type sigma bound 4% of the probe, 2–3% binding was seen with mutants at positions 426, 27, 30 33, 37, 40, 43 and 46, and <2% binding was seen with mutants at positions 445, 48 and 49, with positions 425, 34, 36, 41 and 51 being below the limit of detection. (B) The lambda PR′ probe from –41 to +1. In typical experiments, wild-type sigma bound 8% of the probe. Binding of 2–3% was seen with mutants at positions 426, 30, 33, 37, 40 and 49, and <2% binding was seen with mutants at positions 425, 27, 43, 45, 46 and 48, with positions 434, 36, 41 and 51 being below the limit of detection. (C) The truncated lambda PR′ probe from –41 to –12. Tighter binding on this probe is due to its partial fork junction character when the last base pair frays. In typical experiments, wild-type sigma bound 20% of the probe. Binding of 12–20% was seen with mutants at positions 426, 27, 30, 33, 37 and 40, 2–9% binding was seen with mutants at positions 425, 36, 43, 45, 46, 48 and 49, and with mutants at positions 434, 41 and 51, binding was below the limit of detection.

The mutant sigmas were tested in parallel. Five mutants did not give a detectable shifted band (Y425A, W434A, R436S, R441A and R451S), indicating a defect in lac UV5 duplex recognition. All other mutants gave a detectable shifted band, although the intensity varied considerably. We infer that many changes can have an effect on duplex recognition but that five substitutions were most damaging. These were in three arginine residues and two aromatics, and spanned the entire length of helix 14 and perhaps further.

The experiment was repeated using the λ PR′ promoter probe. Figure 2B shows that the results are very similar, although not identical. The five residues defined as defective on lac UV5 are also defective on this promoter probe (Y425A, W434A, R436S, R441S and R451S). Y425A does show some binding but is weaker than that of any of the other 11 mutant sigmas. Thus, the data are in substantial agreement with these five substitutions being the most damaging to double-stranded promoter recognition.

We created and tested a third probe that has the λ PR′ sequence beginning at the same –41 location but truncated at –12. This probe lacks the entire targeted melting region and measures interactions that are dependent on nucleotides from –12 upstream. However, it is truncated near the position at which the natural fork junction is created, and thus fraying of the terminal base pair might create a fork junction-binding substrate (Guo and Gralla, 1998; Guo et al., 1999). This may be minimal as the junction is not at the optimal location and the fraying is minimized by the use of low temperatures. Figure 2C shows the result of an EMSA using this truncated duplex probe.

In this assay, three of the five mutants identified above remain fully defective (W434A, R441S and R451S). Another previously defective mutant, R436S, is also a very weak binder to this probe. The Y425A mutant cannot be categorized as severely defective in this assay as its signal strength is now greater than that of some other mutants. We infer that the same set of four mutants are identified as defective on three probes, with a fifth, Y425A, exhibiting probe-dependent behavior. We note that the defects of these four mutants, all between positions 434 and 451, should reflect interactions at –12 and further upstream because the consensus nucleotides downstream from this position are missing in the experiment of Figure 2C.

Two further aspects of the data are worth noting. First, nearby mutants Y425A and F427A bind weakly on the full-length probes (Figure 2A and B), but binding is observed on the truncated probe (Figure 2C). This indicates that these residues affect binding downstream of the –12 nucleotide. Because F427 is buried in the sigma structure (Malhotra et al., 1996) and has been suggested previously to be involved in folding (Juang and Helmann, 1994), we cannot assess whether these effects are direct or are an indirect consequence of modest structural perturbations.

Secondly, mutants C–terminal to 441 (lower panel of Figure 2C) act as a set in showing weaker binding than the mutants N–terminal to 433 (upper panel). This difference is strongest using the truncated PR′ probe assay and is weakly evident in Figure 2A and B. The comparison suggests that the segment C–terminal to 441 may have a general role in recognition of the upstream duplex DNA segment beginning near position –12. This would be in addition to the critical role of the five mutants just discussed.

Binding to fork junction probes

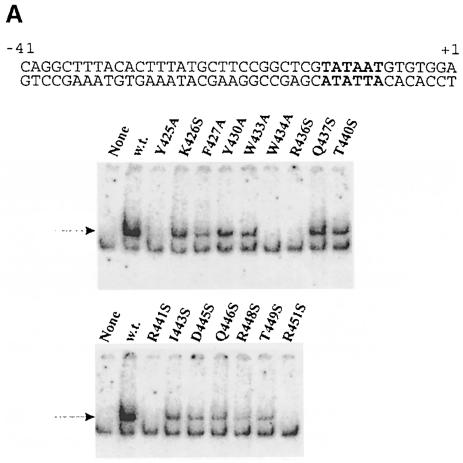

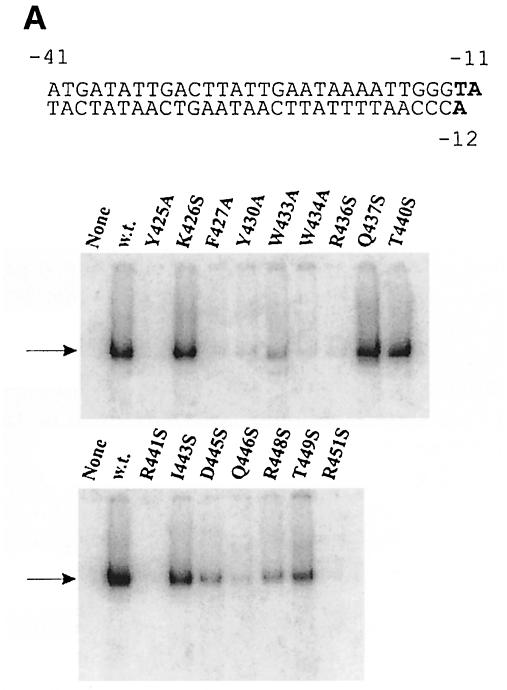

Prior experiments have suggested that interaction with the upstream junction between double- and single-stranded DNA is critical for open complex formation (Guo and Gralla, 1998; Guo et al., 1999), thus we created a probe that mimicked this fork junction. This involved adding a single unpaired nucleotide to the truncated double-stranded probe used in the experiments of Figure 2C (see Figure 3A, top). Binding to this fork junction probe in the previous experiments was shown to yield complexes that exhibited resistance to heparin, a common indicator of the kind of tight complexes that typify authentic open complexes (Guo and Gralla, 1998). The data in Figure 3A were derived from heparin challenge of complexes on the fork junction probe.

Fig. 3. EMSA of holoenzymes with mutant sigmas on fork junction probes derived from lambda PR′. The sequence of each labeled probe is at the top, with –10 element nucleotides shown in bold. Heparin was added to each reaction after the proteins were incubated with the probe. (A) The fork junction probe. In typical experiments, wild-type sigma bound 32% of the probe, 23–28% binding was seen with mutants at positions 426, 37 and 40, 8–14% binding was seen with mutants at positions 443 and 49, and <4% binding was seen with mutants at positions 430, 33, 45, 46 and 48, with positions 425, 27, 34, 36, 41 and 51 being below the level of detection. (B) A different fork junction probe. In typical experiments, wild-type sigma bound 70% of the probe, 23–63% binding was seen with mutants at positions 426, 37, 40, 43 and 49, 6–14% binding was seen with mutants at positions 430, 33, 45 and 48, and <4% binding was seen with mutants at positions 434, 36 and 46, with positions 425, 27, 41 and 51 being below the level of detection.

The data show that many point mutations reduce the ability to form heparin-resistant complexes with the fork junction probe. These include the five mutations discussed above. These five are likely to be defective in the fork-binding assay because they fail to bind the duplex segment of the probe (but see above for a discussion of the probe-dependent behavior of Y425A).

However, there are two striking differences between the results of duplex binding and heparin-resistant fork binding. These are mutants Y430A and W433A; they each bind double-stranded DNA well (Figure 2) but fail to bind well in the heparin challenge fork junction assay (Figure 3A). The specific loss of binding by Y430A and W433A was confirmed by studying a slightly different fork probe, which gave consistent results (Figure 3B). These two aromatic amino acids previously were among those implicated in melting in B.subtilis (Juang and Helmann, 1994; Huang et al., 1997). We conclude that the two mutants, Y430A and W433A, have specific defects in interacting with the upstream fork junction.

In addition, several other mutants showed lowered binding to the fork junction probes, primarily within a small patch centered near residue 446 (Figure 3). These mutant defects differ from Y430A and W433A in that there is a very significant contribution from a defect in binding to the double-stranded part of the fork probes. This can be seen in Figure 2C where all mutants within this patch show clear defects compared with the normal duplex binding by Y430A and W433A. Thus, the data suggest that Y430A and W433A have the strongest defect in specific binding to fork junctions.

Permanganate probing of open complexes

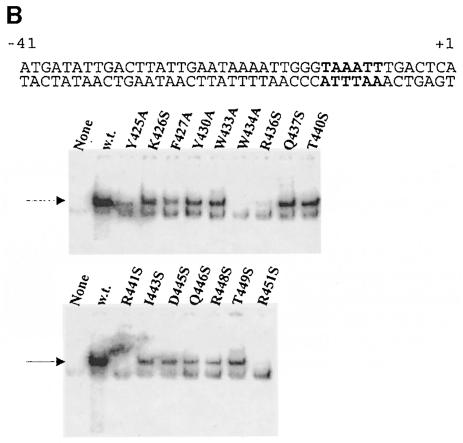

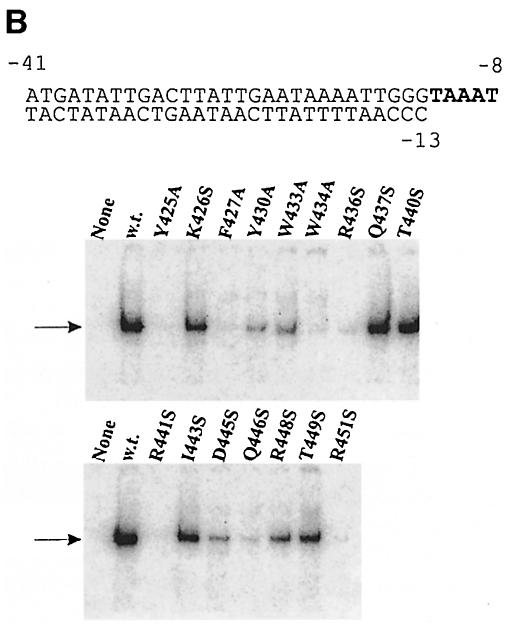

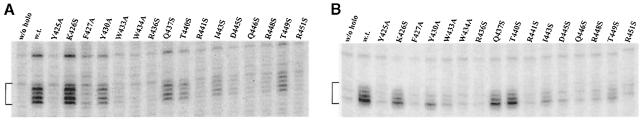

In a last set of experiments, we applied a permanganate assay for full open complex formation. This is the most stringent assay in the sense that any of several defects can lead to loss of permanganate signal: loss of duplex binding, loss of fork binding, loss of single strand binding and other unknown defects. This experiment uses supercoiled lac UV5 plasmid DNA and assays the sensitivity of thymines on the non-template strand. Because many of the mutants showed partial defects, the experiment was carried out at two temperatures: 30°C (Figure 4A) and 37°C (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4. KMnO4 reactivity using holoenzymes with mutant sigmas on the lac UV5 promoter by probing the non-template strand. Controls without holoenzyme and with wild-type holoenzyme are on the far left. Reactions at (A) 30°C and (B) 37°C.

Only three mutants (and wild type) show a clear permanganate signal at both temperatures: K426S, Q437S and T440S (Figure 4). Three others (Y430A, I443S and T449S) show a permanganate signal at one temperature: 30°C (Figure 4B). All other mutants either had no signal or a very weak one. The data agree reasonably well with those obtained by assaying heparin-resistant fork binding. Specifically, the set with a permanganate signal under both conditions (K426S, Q437S and T440S) is also the set that shows fork binding (Figure 3A). Two of the three mutants showing a permanganate signal under only one condition were also only partially defective in fork junction binding (I443S and T449S in Figure 3A). The only discrepancy is with mutant Y430A, which is partially defective in the permanganate assay but strongly defective in fork junction binding. This difference could be attributed to the use of supercoiled DNA as well as higher incubation temperatures in the permanganate assay.

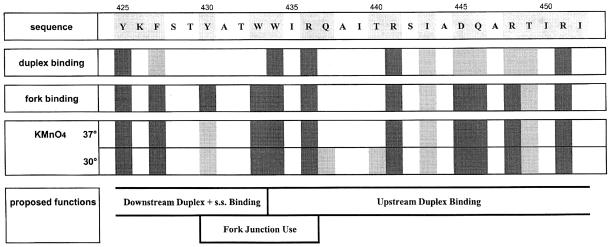

The comparisons imply that heparin-resistant fork junction binding and open complex formation are closely related. They also define a consistent set of residues that contribute to these interactions and to duplex DNA binding. The data for these and other experiments are summarized in Figure 5, which will be used as a basis for subsequent discussion.

Fig. 5. Summary of data and proposed functions of the σ70 region between amino acids 425 and 452. In the top line, shading shows the amino acids that were subjected to mutation. For the three assays shown on the left, dark shading indicates that mutation led to a strong defect and light shading indicates a detectable defect. The bottom of the figure indicates how the data best fit with the proposed functions of this region in E.coli σ70. In this display, fork junction use refers to the structure created when the –12 base pair is intact and –11 is melted. Upstream and downstream are relative to this fork junction.

Discussion

The data shown here lead to new and revised models for promoter recognition and opening. Current models (Malhotra et al., 1996; Bown et al., 1999; Helmann and deHaseth, 1999) emphasize the distinction between the aromatic residues of region 2.3 (involved in melting) and the hydrophilic residues of regions 2.4 and 2.5 (required for duplex recognition). The current data demonstrate that duplex recognition involves both types of amino acids and both regions. The subsequent DNA opening is shown to be connected closely to the creation of a DNA double strand–single strand fork junction (Guo and Gralla, 1998; Guo et al., 1999). The results give a glimpse of the protein determinants involved in junction recognition, which include a unique pair of aromatic residues previously connected to promoter melting (Juang and Helmann, 1994; Callaci and Heyduk, 1998).

Closed complex formation

The data show the importance of three arginine residues (R436, R441 and R451) and two aromatic residues (W434 and Y425) in duplex DNA binding (Figure 2). Serine substitution in any of the three arginines leads to strongly reduced binding to a promoter probe containing duplex sequences from –41 to –12 (Figure 2C), a segment of promoter that is not melted in open complexes (Kirkegaard et al., 1983; Sasse-Dwight and Gralla, 1989; Kainz and Roberts, 1992). Thus, the arginine trio is likely to be a dominant recognition element of the duplex region from –12 upstream. This trio includes one residue previously implicated in –13 recognition, R441 (Zuber et al., 1989; Daniels et al., 1990). Other substitutions in the 10 amino acid segment between 441 and 451 lead to observable binding defects on duplex probes that do not contain base pairs downstream from –12. Thus, we suspect that R441 recognizes –13, and the residues up to R451 continue recognition of the upstream DNA segment.

The current data on the recognition of the duplex from –12 downstream, which constitutes the –10 region consensus sequence, suggest differences from existing models. Prior models implicate Q437 and T440 in –12 recognition, based on suppressor analyses (Kenney et al., 1989; Siegele et al., 1989; Waldburger et al., 1990; Marr and Roberts, 1997). However, the original data only show minor defects in transcription when mutating these amino acids in σ70 (Siegele et al., 1989; Waldburger et al., 1990) or its B.subtilis analog (Kenney et al., 1989). Such proteins also show no detectable defect in the binding experiments presented here. Thus, the ability of substitutions to suppress –12 changes may reflect the proximity of Q437 and T440 to –12 rather than a direct role in –12 recognition. The current data suggest the more prominent involvement of two nearby residues, R436 and W434, as these are important for recognition of duplex probes truncated beyond this critically conserved –12 T:A base pair. Diverse studies using σE support the use of these amino acids to recognize the upstream edge of the –10 element (Jones and Moran, 1992; Tatti and Moran, 1995). Thus, we suspect that common recognition from –12 downstream begins near R436. Recognition from –13 upstream probably begins near R441, as it has been implicated in suppression at this position (Zuber et al., 1989; Daniels et al., 1990) and our data show that substitution there decreases binding.

It is not known how the remainder of the –10 region is recognized in duplex form. The closely spaced mutants Y425A and F427A show duplex recognition defects consistent with this possibility (see Results). Cleavage studies place Y425 in the vicinity of these nucleotides (Colland et al., 1999). Because F427 is buried in the structure (Malhotra et al., 1996), it cannot be determined definitively that these effects are direct. Overall, there is little experimental evidence concerning the role of the –10 to –7 region in duplex recognition, which is remarkable considering the common assumption of its importance in this process (Stefano et al., 1980). In fact, a duplex recognition contribution by elements outside of sigma region 2 cannot be excluded by the current genetic and biochemical data.

None of the mutants assayed here show serious enough defects in core binding to influence duplex recognition. Even the most unstable mutant holoenzymes, with a 5–fold reduction in half-life, bind duplex DNA well. For the five mutants that were severely defective in duplex binding, increasing the amount of holoenzyme or either the core or sigma components did not cure the defect (data not shown). The data indicate that this segment is not a major core-binding determinant, as also indicated from the lack of mutants in this segment from a screen for core-binding defects (Sharp et al., 1999).

Fork junction recognition and DNA melting

The data (summarized in Figure 5) demonstrate that proper closed complex formation requires an unexpectedly extensive set of residues encompassing minimally the region between Y425 and R451. The data also show that two aromatic residues within this segment, W433 and Y430, have no role in closed complex formation, but are required to open the DNA. Thus, the data indicate that melting occurs using a separate determinant within a larger duplex recognition element. In this model, region 2.3 is still involved in melting but it also has a role in closed complex formation along with regions 2.4 and 2.5.

The data support the hypothesis that melting is critically related to the creation and recognition of the upstream fork junction (Guo and Gralla, 1998; Guo et al., 1999). The two melting residues W433 and Y430 (Juang and Helmann, 1994; Callaci and Heyduk, 1998; the above permanganate data) are also the two residues uniquely required for fork junction binding. Specifically, they are not required to bind the duplex probe truncated at –12. However, when a single non-template strand adenine is added at –11, they become essential in forming a heparin-resistant complex with this fork probe. Thus, this aromatic pair has two properties that are likely to be co-joined: they are needed to stabilize the –12/–11 upstream fork junction and are required to melt the DNA.

Residues 445, 446 and 448 may also play a supporting role in melting and fork junction binding. They have moderate DNA-binding defects but the defects in fork junction and permanganate assays appear to be more severe (Figure 5). Prior studies detected conformational changes near R448 (Buckle et al., 1999) accompanying the large changes within polymerase that occur during opening (Roe et al., 1985; Polyakov et al., 1995). Thus, this region may contact duplex DNA and assist in the re-organization of the protein–DNA complex during opening.

Overview of how duplex DNA might be recognized and then melted

Overall, the data indicate that a series of aromatics and positively charged arginines are arrayed in a manner that allows initial recognition and subsequent opening of duplex DNA. Both types of residues contribute to recognition of the targeted region. The arginine trio (positions 436, 441 and 451) appears to be involved exclusively in duplex contacts from –12 upstream and is aided by nearby residues (445, 446 and 448). The aromatics are involved in both duplex recognition and DNA opening.

Within this recognition segment from 425 to beyond 451, two aromatic residues play a unique role in opening the duplex. W433 and Y430 are required to recognize the fork junction created when base pair –11 is melted out of the duplex. We note that in the crystal structure (Malhotra et al., 1996) this aromatic pair forms a nearly parallel stack with appropriate spacing to accept an intercalated nucleotide ring. One possibility is that transient exposure of the non-template –11 nucleotide allows it to become intercalated within the pair to form a triple ring stack and stabilize melting to drive open complex formation. An analogous triple stack forms when a modified base is ‘flipped out’ of a helix during DNA repair (Lau et al., 1998). Such an interaction has not been observed previously in opening during transcription, but the analogy suggests that the mechanism could have some generality in opening systems.

The process of duplex recognition and melting must occur during transcription, replication, repair and probably transposition, but there is as yet limited information about how this occurs. The T7 RNA polymerase uses stacking of amino acids to nucleotides and hydrogen bonds to stabilize the melted DNA (Cheetham et al., 1999). Indeed, stacks were predicted originally (Helmann and Chamberlin, 1988) based on the structure of single-stranded RNA-binding proteins (Coleman and Oakley, 1980). The promoter model suggested here includes recognition of a large region of duplex DNA and then use of a fork junction-binding motif to stabilize opening within it. It will be interesting to learn the applicability of this model to opening of DNA regions used for initiation of replication, transposition and various repair processes.

Materials and methods

Proteins and DNA

rpoD mutants were made using pQE30-rpoD (Wilson and Dombroski, 1997) by site-directed mutagenesis and transformed into supercompetent E.coli XL1 Blue cells (Stratagene). The transformed cells were plated on 200 μg/ml ampicillin, 2% glucose, LB plates. Colonies were screened for isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-induced sigma from sonicated extracts with proper migration by SDS–PAGE. Numerous sigma clones migrated to lower positions on protein gels, especially from W434A screens, and these were not studied further. Other mutants that were difficult to obtain were Y425A and F427A. The candidates that passed this mobility screen were sequenced and if they contained the correct mutation were purified as described (Wilson and Dombroski, 1997) and the mobility re-checked. The E.coli RNA polymerase core enzyme is a commercial product from Epicenter Technologies. Plasmid pAS21 (Stefano et al., 1980), which contains the lacUV5 promoter, was used in KMnO4 assays. All oligonucleotides were gel purified and probes were prepared as described (Guo and Gralla, 1998).

Electrophoresis mobility shift assay

Mobility assays were performed as follows: 20 nM core was mixed with 50 nM sigma in a 10 μl reaction mixture with 1× buffer A [30 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 6 ng/μl (dI–dC), 3.25% glycerol] and 1 nM annealed DNA probe, and incubated for 20 min on ice. For fork junction probes, 0.25 μl of 2 mg/ml heparin was added for an additional 5 min (Guo and Gralla, 1998). Samples were run on 5% PAGE with 1× TBE buffer, packed in ice.

Surface plasmon resonance

SPR was conducted with a Biacore X instrument using a nitrilotriacetic acid sensor chip (NTA chip). All experiments were conducted at 25°C in modified buffer A (30 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 50 μM EDTA, 0.005% P20 surfactant, 100 μg/ml CM-dextran). N–terminal, His6-tagged sigma was attached to an NTA chip as follows: 10 μl of 500 μM NiSO4 solution were injected over one flow cell at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. Then 50 nM sigma was injected over the same flow cell at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. A resulting resonance response unit (RU) of 50–100 was obtained. After immobilization of sigma to the chip, 50 nM core polymerase was injected over two flow cells (RU change of 100–150). An empty flow cell was used as a control for non-specific binding and bulk effects. After the dissociation phase, the NTA chip was regenerated by injection of 150 mM imidazole at 10 μl/min followed by an injection of 0.25 M EDTA at 10 μl/min. Half-lives for core polymerase binding to sigma were derived from the dissociation curves obtained. Each experiment was repeated 3–5 times and the average of these trials was used to determine the sigma–core half-lives (Table I).

KMnO4 footprinting

Sigma (100 nM), core polymerase (40 nM) and plasmid pAS 21 (2 nM) were incubated for 10 min on ice in slightly modified buffer A (30 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 50 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml BSA). This was followed by incubation at either 30 or 37°C for 15 min to allow formation of open complexes. A final concentration of 10 mM KMnO4 was then added to each sample, incubated at the appropriate temperature for 2 min and processed for primer extension analysis as described (Sasse-Dwight and Gralla, 1989). Each experiment was repeated 3–4 times and results were similar for the template and non-template strands.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Randy Yang and Chih Lew for their assistance in the initial stages of this work. The research was supported by a grant from the NIH (GM35754).

References

- Barne K.A., Bown, J.A., Busby, S.J. and Minchin, S.D. (1997) Region 2.5 of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase σ70 subunit is responsible for the recognition of the ‘extended-10’ motif at promoters. EMBO J., 16, 4034–4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bown J.A., Owens, J.T., Meares, C.F., Fujita, N., Ishihama, A., Busby, S.J. and Minchin, S.D. (1999) Organization of open complexes at Escherichia coli promoters. Location of promoter DNA sites close to region 2.5 of the σ70 subunit of RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 2263–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckle M., Pemberton, I.K., Jacquet, M.A. and Buc, H. (1999) The kinetics of sigma subunit directed promoter recognition by E.coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol., 285, 955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaci S. and Heyduk, T. (1998) Conformation and DNA binding properties of a single-stranded DNA binding region of σ70 subunit from Escherichia coli RNA polymerase are modulated by an interaction with the core enzyme. Biochemistry, 37, 3312–3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham G.M., Jeruzalmi, D. and Steitz, T.A. (1999) Structural basis for initiation of transcription from an RNA polymerase–promoter complex. Nature, 399, 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.E. and Oakley, J.L. (1980) Physical chemical studies of the structure and function of DNA binding (helix-destabilizing) proteins. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem., 7, 247–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colland F., Fujita, N., Kotlarz, D., Bown, J.A., Meares, C.F., Ishihama, A. and Kolb, A. (1999) Positioning of sigma (S), the stationary phase sigma factor, in Escherichia coli RNA polymerase–promoter open complexes. EMBO J., 18, 4049–4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels D., Zuber, P. and Losick, R. (1990) Two amino acids in an RNA polymerase sigma factor involved in the recognition of adjacent base pairs in the –10 region of a cognate promoter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 8075–8079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. and Gralla, J.D. (1998) Promoter opening via a DNA fork junction binding activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 11655–11660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Wang, L. and Gralla, J.D. (1999) A fork junction DNA–protein switch that controls promoter melting by the bacterial enhancer-dependent sigma factor. EMBO J., 18, 3736–3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley D.K. and McClure, W.R. (1983) Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 2237–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann J.D. and Chamberlin, M.J. (1988) Structure and function of bacterial sigma factors. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 57, 839–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann J.D. and deHaseth, P.L. (1999) Protein–nucleic acid interactions during open complex formation investigated by systematic alteration of the protein and DNA binding partners. Biochemistry, 38, 5959–5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Lopez de Saro, F.J. and Helmann, J.D. (1997) σ factor mutations affecting the sequence-selective interaction of RNA polymerase with –10 region single-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2603–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C.H. and Moran, C.P.,Jr (1992) Mutant sigma factor blocks transition between promoter binding and initiation of transcription. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 1958–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang Y.L. and Helmann, J.D. (1994) A promoter melting region in the primary sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis. Identification of functionally important aromatic amino acids. J. Mol. Biol., 235, 1470–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kainz M. and Roberts, J. (1992) Structure of transcription elongation complexes in vivo. Science, 255, 838–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilty S. and Rosenberg, M. (1987) Constitutive function of a positively regulated promoter reveals new sequences essential for activity. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 6389–6395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney T.J., York, K., Youngman, P. and Moran, C.P.,Jr (1989) Genetic evidence that RNA polymerase associated with σA factor uses a sporulation-specific promoter in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 9109–9113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkegaard K., Buc, H., Spassky, A. and Wang, J.C. (1983) Mapping of single-stranded regions in duplex DNA at the sequence level: single-strand-specific cytosine methylation in RNA polymerase–promoter complexes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 2544–2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A.Y., Scharer, O.D., Samson, L., Verdine, G.L. and Ellenberger, T. (1998) Crystal structure of a human alkylbase-DNA repair enzyme complexed to DNA: mechanisms for nucleotide flipping and base excision. Cell, 95, 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A., Severinova, E. and Darst, S.A. (1996) Crystal structure of a σ70 subunit fragment from E.coli RNA polymerase. Cell, 87, 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr M.T. and Roberts, J.W. (1997) Promoter recognition as measured by binding of polymerase to nontemplate strand oligonucleotide. Science, 276, 1258–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyakov A., Severinova, E. and Darst, S.A. (1995) Three-dimensional structure of E.coli core RNA polymerase: promoter binding and elongation conformations of the enzyme. Cell, 83, 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C.W. and Roberts, J.W. (1996) Base-specific recognition of the nontemplate strand of promoter DNA by E.coli RNA polymerase. Cell, 86, 495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe J.H., Burgess, R.R. and Record, M.T.,Jr (1985) Temperature dependence of the rate constants of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase–λ PR promoter interaction. Assignment of the kinetic steps corresponding to protein conformational change and DNA opening. J. Mol. Biol., 184, 441–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross W., Gosink, K.K., Salomon, J., Igarashi, K., Zou, C., Ishihama, A., Severinov, K. and Gourse, R.L. (1993) A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α subunit of RNA polymerase. Science, 262, 1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse-Dwight S. and Gralla, J.D. (1989) KMnO4 as a probe for lac promoter DNA melting and mechanism in vivo. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 8074–8081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp M.M., Chan, C.L., Lu, C.Z., Marr, M.T., Nechaev, S., Merritt, E.W., Severinov, K., Roberts, J.W. and Gross, C.A. (1999) The interface of sigma with core RNA polymerase is extensive, conserved and functionally specialized. Genes Dev., 13, 3015–3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegele D.A., Hu, J.C., Walter, W.A. and Gross, C.A. (1989) Altered promoter recognition by mutant forms of the σ70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol., 206, 591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano J.E., Ackerson, J.W. and Gralla, J.D. (1980) Alterations in two conserved regions of promoter sequence lead to altered rates of polymerase binding and levels of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res., 8, 2709–2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatti K.M. and Moran, C.P.,Jr (1995) σE changed to σB specificity by amino acid substitutions in its –10 binding region. J. Bacteriol., 177, 6506–6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldburger C., Gardella, T., Wong, R. and Susskind, M.M. (1990) Changes in conserved region 2 of Escherichia coli σ70 affecting promoter recognition. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. and Dombroski, A.J. (1997) Region 1 of σ70 is required for efficient isomerization and initiation of transcription by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol., 267, 60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber P., Healy, J., Carter, H.L., III, Cutting, S., Moran, C.P., Jr and Losick, R. (1989) Mutation changing the specificity of an RNA polymerase sigma factor. J. Mol. Biol., 206, 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]