Abstract

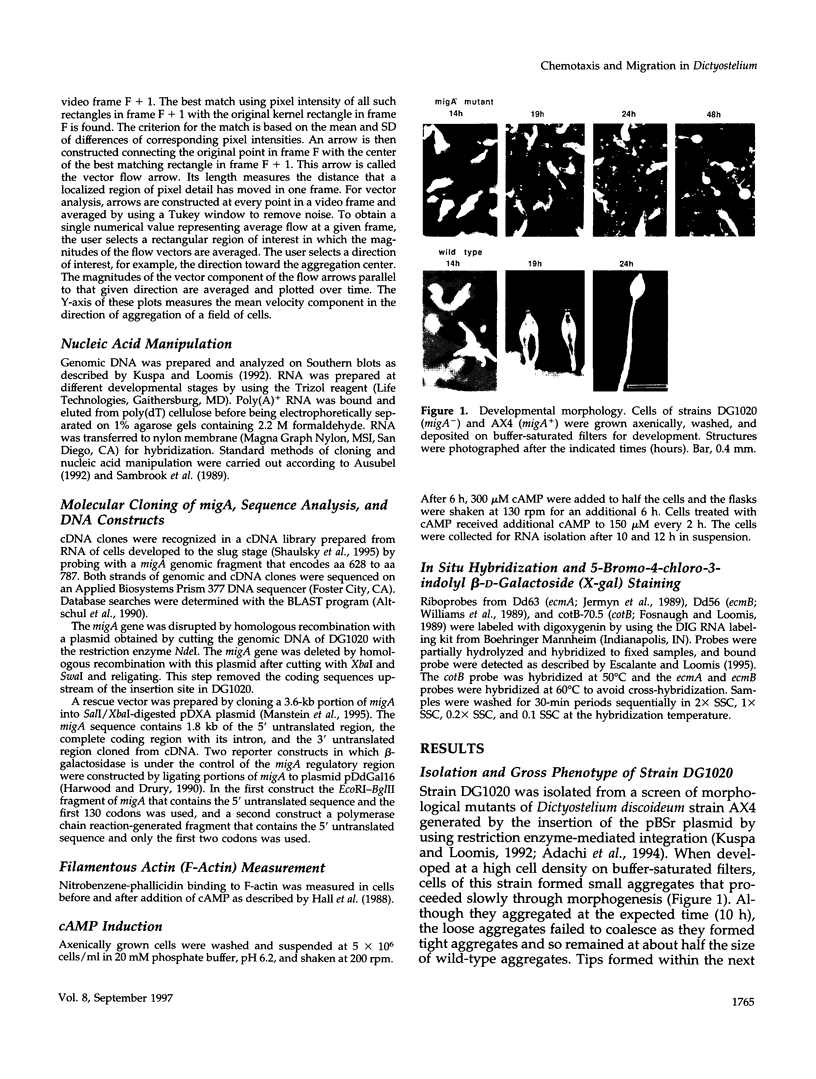

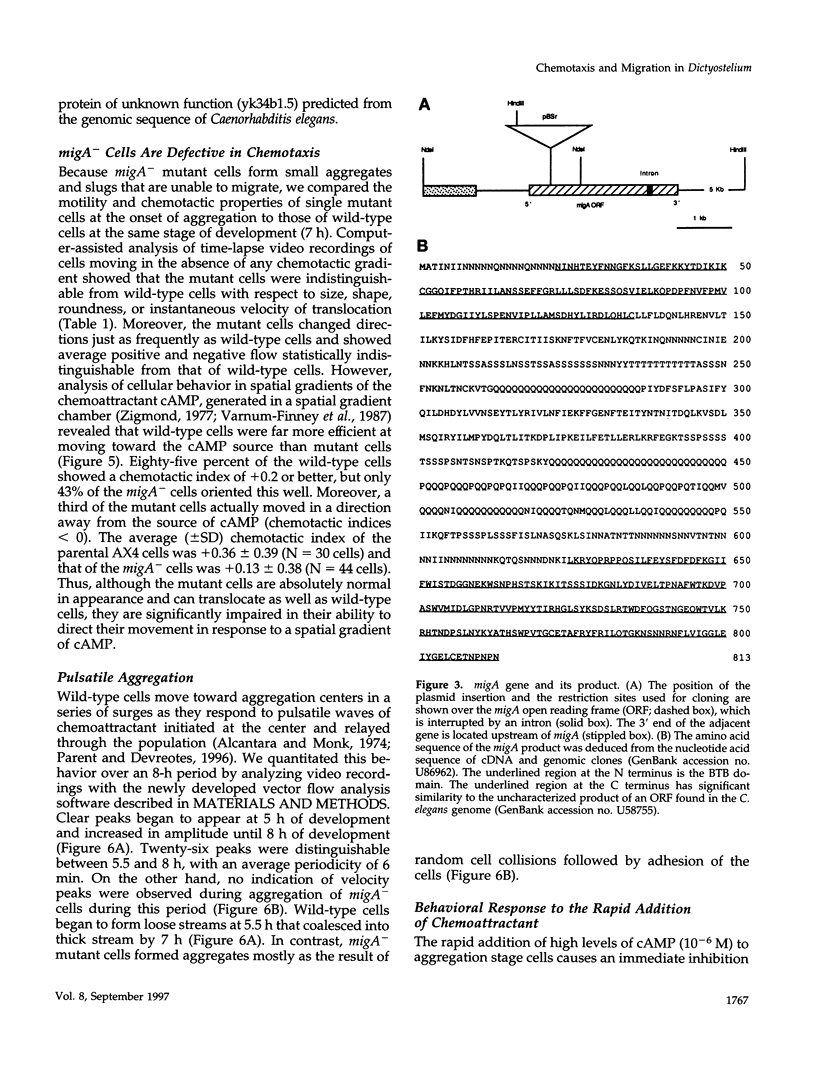

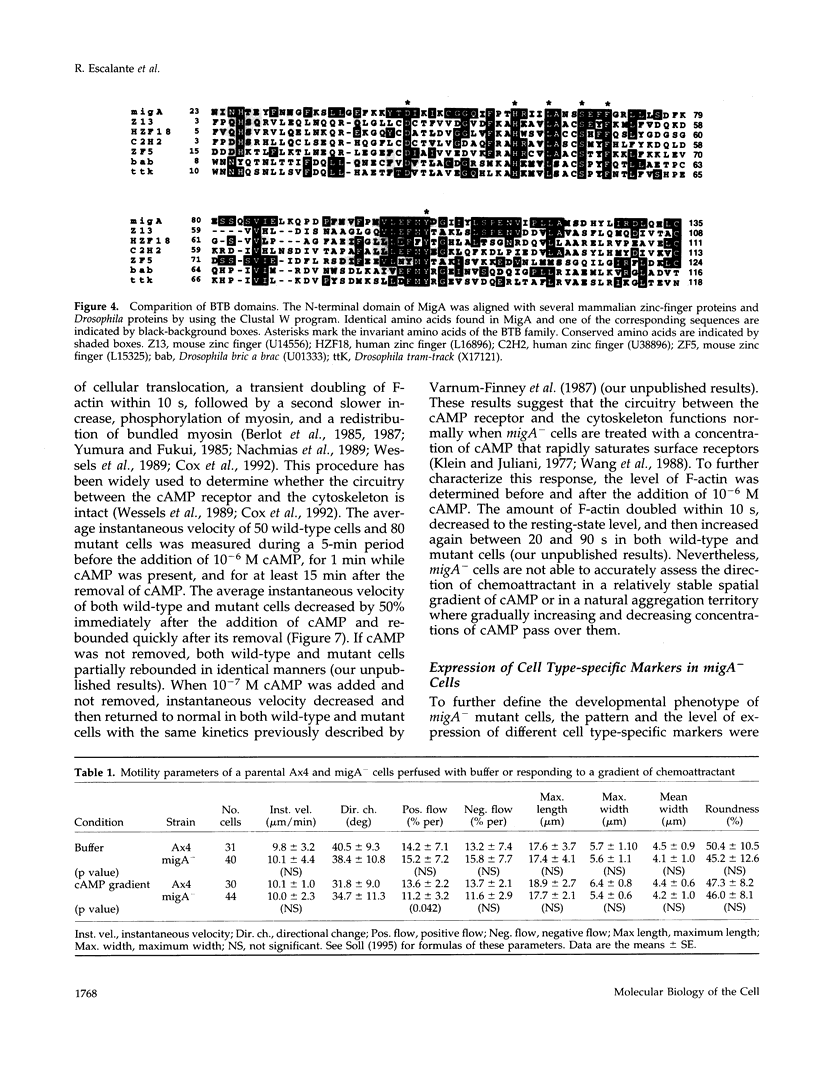

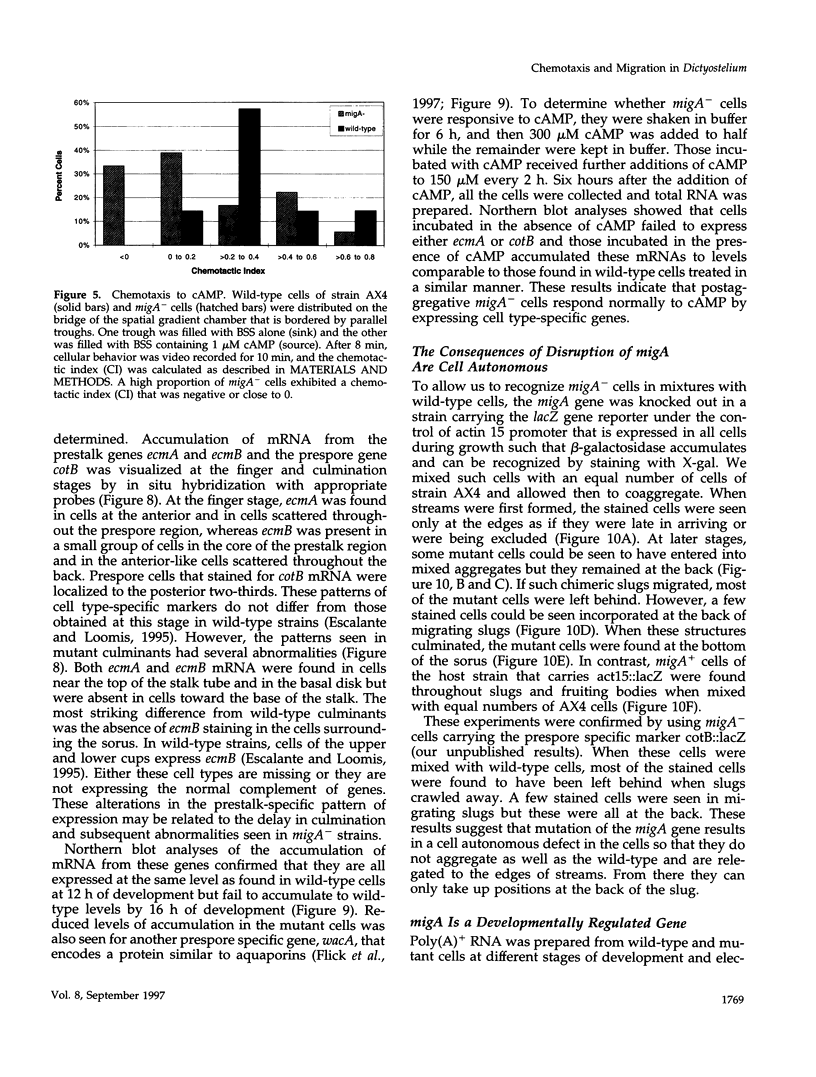

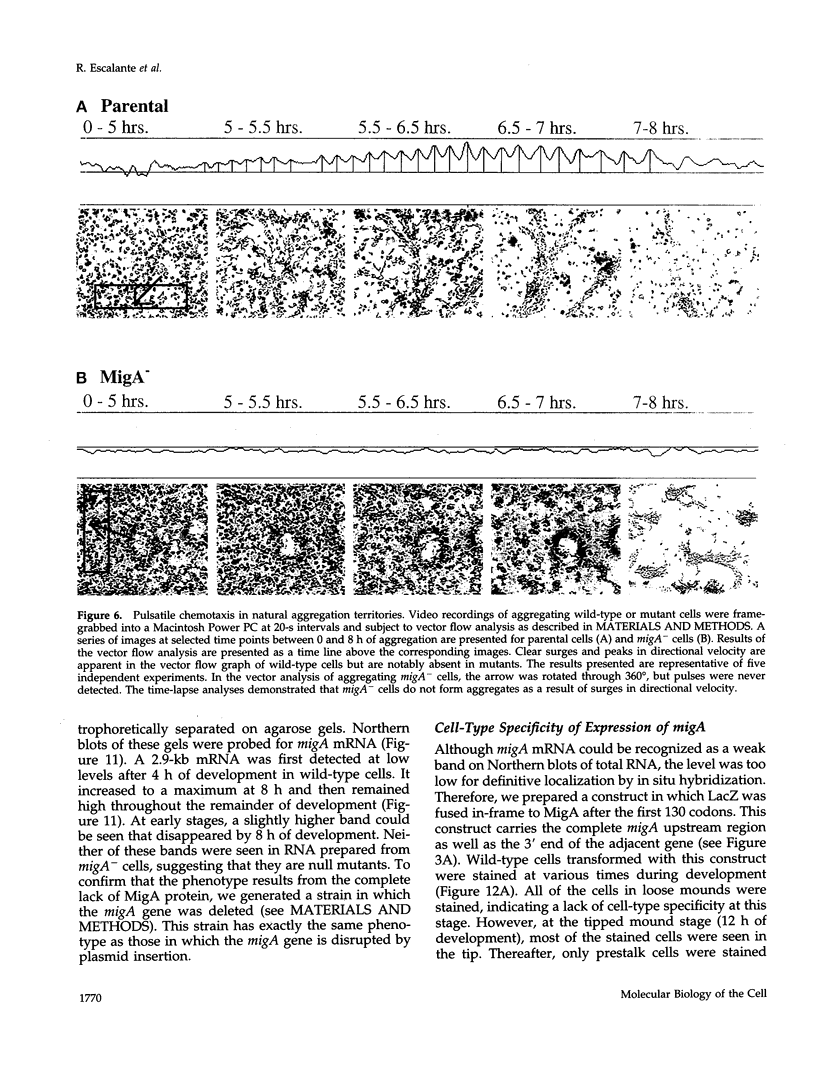

Chemotaxis in natural aggregation territories and in a chamber with an imposed gradient of cyclic AMP (cAMP) was found to be defective in a mutant strain of Dictyostelium discoideum that forms slugs unable to migrate. This strain was selected from a population of cells mutagenized by random insertion of plasmids facilitated by introduction of restriction enzyme (a method termed restriction enzyme-mediated integration). We picked this strain because it formed small misshapen fruiting bodies. After isolation of portions of the gene as regions flanking the inserted plasmid, we were able to regenerate the original genetic defect in a fresh host and show that it is responsible for the developmental defects. Transformation of this recapitulated mutant strain with a construct carrying the full-length migA gene and its upstream regulatory region rescued the defects. The sequence of the full-length gene revealed that it encodes a novel protein with a BTB domain near the N terminus that may be involved in protein-protein interactions. The migA gene is expressed at low levels in all cells during aggregation and then appears to be restricted to prestalk cells as a consequence of rapid turnover in prespore cells. Although migA- cells have a dramatically reduced chemotactic index to cAMP and an abnormal pattern of aggregation in natural waves of cAMP, they are completely normal in size, shape, and ability to translocate in the absence of any chemotactic signal. They respond behaviorally to the rapid addition of high levels of cAMP in a manner indicative of intact circuitry connecting receptor occupancy to restructuring of the cytoskeleton. Actin polymerization in response to cAMP is also normal in the mutant cells. The defects at both the aggregation and slug stage are cell autonomous. The MigA protein therefore is necessary for efficiently assessing chemical gradients, and its absence results in defective chemotaxis and slug migration.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abe K., Yanagisawa K. A new class of rapidly developing mutants in Dictyostelium discoideum: implications for cyclic AMP metabolism and cell differentiation. Dev Biol. 1983 Jan;95(1):200–210. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi H., Hasebe T., Yoshinaga K., Ohta T., Sutoh K. Isolation of Dictyostelium discoideum cytokinesis mutants by restriction enzyme-mediated integration of the blasticidin S resistance marker. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994 Dec 30;205(3):1808–1814. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albagli O., Dhordain P., Deweindt C., Lecocq G., Leprince D. The BTB/POZ domain: a new protein-protein interaction motif common to DNA- and actin-binding proteins. Cell Growth Differ. 1995 Sep;6(9):1193–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcantara F., Monk M. Signal propagation during aggregation in the slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum. J Gen Microbiol. 1974 Dec;85(2):321–334. doi: 10.1099/00221287-85-2-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990 Oct 5;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell V. J., Treisman R. The POZ domain: a conserved protein-protein interaction motif. Genes Dev. 1994 Jul 15;8(14):1664–1677. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.14.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlot C. H., Devreotes P. N., Spudich J. A. Chemoattractant-elicited increases in Dictyostelium myosin phosphorylation are due to changes in myosin localization and increases in kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1987 Mar 15;262(8):3918–3926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlot C. H., Spudich J. A., Devreotes P. N. Chemoattractant-elicited increases in myosin phosphorylation in Dictyostelium. Cell. 1985 Nov;43(1):307–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner J., Williams J. Inhibition of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in Dictyostelium prestalk cells impairs slug migration and phototaxis. Dev Biol. 1994 Jul;164(1):325–327. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider T., Siegert F., Weijer C. J. Three-dimensional scroll waves of cAMP could direct cell movement and gene expression in Dictyostelium slugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 May 9;92(10):4387–4391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar A., Wessels D., Soll D. R. A mutation that depresses cGMP phosphodiesterase activity in Dictyostelium affects cell motility through an altered chemotactic signal. Dev Biol. 1995 May;169(1):109–122. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. Y., Insall R. H., Devreotes P. N. Signaling through chemoattractant receptors in Dictyostelium. Trends Genet. 1996 Feb;12(2):52–57. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)81400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Zollman S., Couderc J. L., Laski F. A. The BTB domain of bric à brac mediates dimerization in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1995 Jun;15(6):3424–3429. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Cox D., Condeelis J., Wessels D., Soll D., Kern H., Knecht D. A. Targeted disruption of the ABP-120 gene leads to cells with altered motility. J Cell Biol. 1992 Feb;116(4):943–955. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.4.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D., Wessels D., Soll D. R., Hartwig J., Condeelis J. Re-expression of ABP-120 rescues cytoskeletal, motility, and phagocytosis defects of ABP-120- Dictyostelium mutants. Mol Biol Cell. 1996 May;7(5):803–823. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.5.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detterbeck S., Morandini P., Wetterauer B., Bachmair A., Fischer K., MacWilliams H. K. The 'prespore-like cells' of Dictyostelium have ceased to express a prespore gene: analysis using short-lived beta-galactosidases as reporters. Development. 1994 Oct;120(10):2847–2855. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante R., Loomis W. F. Whole-mount in situ hybridization of cell-type-specific mRNAs in Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 1995 Sep;171(1):262–266. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANCIS D. W. SOME STUDIES ON PHOTOTAXIS OF DICTYOSTELIUM. J Cell Physiol. 1964 Aug;64:131–138. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030640113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firtel R. A. Integration of signaling information in controlling cell-fate decisions in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 1995 Jun 15;9(12):1427–1444. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosnaugh K. L., Loomis W. F. Spore coat genes SP60 and SP70 of Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Nov;9(11):5215–5218. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. L., Schlein A., Condeelis J. Relationship of pseudopod extension to chemotactic hormone-induced actin polymerization in amoeboid cells. J Cell Biochem. 1988 Jul;37(3):285–299. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240370304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood A. J., Drury L. New vectors for expression of the E.coli lacZ gene in Dictyostelium. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 Jul 25;18(14):4292–4292. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.14.4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood A. J., Hopper N. A., Simon M. N., Bouzid S., Veron M., Williams J. G. Multiple roles for cAMP-dependent protein kinase during Dictyostelium development. Dev Biol. 1992 Jan;149(1):90–99. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90266-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insall R., Kuspa A., Lilly P. J., Shaulsky G., Levin L. R., Loomis W. F., Devreotes P. CRAC, a cytosolic protein containing a pleckstrin homology domain, is required for receptor and G protein-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase in Dictyostelium. J Cell Biol. 1994 Sep;126(6):1537–1545. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jermyn K. A., Duffy K. T., Williams J. G. A new anatomy of the prestalk zone in Dictyostelium. Nature. 1989 Jul 13;340(6229):144–146. doi: 10.1038/340144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C., Juliani M. H. cAMP,-induced changes in cAMP-binding sites on D; discoideum amebae. Cell. 1977 Feb;10(2):329–335. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuspa A., Loomis W. F. Tagging developmental genes in Dictyostelium by restriction enzyme-mediated integration of plasmid DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Sep 15;89(18):8803–8807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama H., Ishida S., Van Haastert P. J. Non-chemotactic Dictyostelium discoideum mutants with altered cGMP signal transduction. J Cell Biol. 1993 Dec;123(6 Pt 1):1453–1462. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis W. F. Genetic networks that regulate development in Dictyostelium cells. Microbiol Rev. 1996 Mar;60(1):135–150. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.135-150.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manstein D. J., Schuster H. P., Morandini P., Hunt D. M. Cloning vectors for the production of proteins in Dictyostelium discoideum. Gene. 1995 Aug 30;162(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias V. T., Fukui Y., Spudich J. A. Chemoattractant-elicited translocation of myosin in motile Dictyostelium. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1989;13(3):158–169. doi: 10.1002/cm.970130304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent C. A., Devreotes P. N. Constitutively active adenylyl cyclase mutant requires neither G proteins nor cytosolic regulators. J Biol Chem. 1996 Aug 2;271(31):18333–18336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond C. D., Schaap P., Véron M., Williams J. G. Dual role of cAMP during Dictyostelium development. Experientia. 1995 Dec 18;51(12):1166–1174. doi: 10.1007/BF01944734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler G. R., Fischer W. H., Firtel R. A. Cloning and characterization of the G-box binding factor, an essential component of the developmental switch between early and late development in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 1994 Feb 15;8(4):502–514. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulsky G., Kuspa A., Loomis W. F. A multidrug resistance transporter/serine protease gene is required for prestalk specialization in Dictyostelium. Genes Dev. 1995 May 1;9(9):1111–1122. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.9.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulsky G., Loomis W. F. Cell type regulation in response to expression of ricin A in Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 1993 Nov;160(1):85–98. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert F., Weijer C. J. Spiral and concentric waves organize multicellular Dictyostelium mounds. Curr Biol. 1995 Aug 1;5(8):937–943. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert F., Weijer C. J. Three-dimensional scroll waves organize Dictyostelium slugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Jul 15;89(14):6433–6437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll D. R. Methods for manipulating and investigating developmental timing in Dictyostelium discoideum. Methods Cell Biol. 1987;28:413–431. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61660-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll D. R. The use of computers in understanding how animal cells crawl. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;163:43–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman M. Cultivation and synchronous morphogenesis of Dictyostelium under controlled experimental conditions. Methods Cell Biol. 1987;28:9–29. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61635-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor D., Kessin R. H., Williams J. G. Chemotactic sorting to cAMP in the multicellular stages of Dictyostelium development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Sep 1;89(17):8303–8307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum-Finney B., Edwards K. B., Voss E., Soll D. R. Amebae of Dictyostelium discoideum respond to an increasing temporal gradient of the chemoattractant cAMP with a reduced frequency of turning: evidence for a temporal mechanism in ameboid chemotaxis. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1987;8(1):7–17. doi: 10.1002/cm.970080103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum B., Edwards K. B., Soll D. R. The developmental regulation of single-cell motility in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev Biol. 1986 Jan;113(1):218–227. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum B., Soll D. R. Effects of cAMP on single cell motility in Dictyostelium. J Cell Biol. 1984 Sep;99(3):1151–1155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Kuspa A. Dictyostelium development in the absence of cAMP. Science. 1997 Jul 11;277(5323):251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Van Haastert P. J., Devreotes P. N., Schaap P. Localization of chemoattractant receptors on Dictyostelium discoideum cells during aggregation and down-regulation. Dev Biol. 1988 Jul;128(1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels D., Schroeder N. A., Voss E., Hall A. L., Condeelis J., Soll D. R. cAMP-mediated inhibition of intracellular particle movement and actin reorganization in Dictyostelium. J Cell Biol. 1989 Dec;109(6 Pt 1):2841–2851. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels D., Soll D. R., Knecht D., Loomis W. F., De Lozanne A., Spudich J. Cell motility and chemotaxis in Dictyostelium amebae lacking myosin heavy chain. Dev Biol. 1988 Jul;128(1):164–177. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. G., Duffy K. T., Lane D. P., McRobbie S. J., Harwood A. J., Traynor D., Kay R. R., Jermyn K. A. Origins of the prestalk-prespore pattern in Dictyostelium development. Cell. 1989 Dec 22;59(6):1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yumura S., Fukui Y. Reversible cyclic AMP-dependent change in distribution of myosin thick filaments in Dictyostelium. Nature. 1985 Mar 14;314(6007):194–196. doi: 10.1038/314194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond S. H. Ability of polymorphonuclear leukocytes to orient in gradients of chemotactic factors. J Cell Biol. 1977 Nov;75(2 Pt 1):606–616. doi: 10.1083/jcb.75.2.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollman S., Godt D., Privé G. G., Couderc J. L., Laski F. A. The BTB domain, found primarily in zinc finger proteins, defines an evolutionarily conserved family that includes several developmentally regulated genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Oct 25;91(22):10717–10721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]