Abstract

Insights into bacterium-host interactions and genome evolution can emerge from comparisons among related species. Here we studied Helicobacter acinonychis (formerly H. acinonyx), a species closely related to the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Two groups of strains were identified by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting and gene sequencing: one group from six cheetahs in a U.S. zoo and two lions in a European circus, and the other group from a tiger and a lion-tiger hybrid in the same circus. PCR and DNA sequencing showed that each strain lacked the cag pathogenicity island and contained a degenerate vacuolating cytotoxin (vacA) gene. Analyses of nine other genes (glmM, recA, hp519, glr, cysS, ppa, flaB, flaA, and atpA) revealed a ∼2% base substitution difference, on average, between the two H. acinonychis groups and a ∼8% difference between these genes and their homologs in H. pylori reference strains such as 26695. H. acinonychis derivatives that could chronically infect mice were selected and were found to be capable of persistent mixed infection with certain H. pylori strains. Several variants, due variously to recombination or new mutation, were found after 2 months of mixed infection. H. acinonychis ' modest genetic distance from H. pylori, its ability to infect mice, and its ability to coexist and recombine with certain H. pylori strains in vivo should be useful in studies of Helicobacter infection and virulence mechanisms and studies of genome evolution.

Functional and sequence comparisons among related bacterial strains and species can provide insights into evolutionary mechanisms and help identify factors that contribute to the virulence of pathogens (37, 51). Here we report studies of strains of Helicobacter acinonychis (formerly H. acinonyx), which chronically infects the gastric mucosa of cheetahs and other big cats and that, based on 16S rRNA sequence data, seems to be the most closely related of known helicobacters to the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori (12, 13, 45). Chronic infection of cheetahs by H. acinonyx is thought to contribute to the development of severe gastritis, a frequent cause of their death in captivity (12, 35).

H. pylori itself is a most genetically diverse species: independent clinical isolates are usually distinguishable by DNA fingerprinting (4) and typically differ from one another by some 2% or more in sequences of essential housekeeping genes and 5% or more in gene content (1, 3, 5, 43). This diversity probably stems from a combination of factors, including (i) mutation (50); (ii) recombination between divergent strains and species (1, 5, 16, 46, 47); (iii) selection for host-specific adaptation during chronic infection, which reflects differences between people and also within individual stomachs in traits that can be important to H. pylori (2, 11, 25, 33); and (iv) a highly localized (preferentially intrafamilial) pattern of transmission (22, 38), which promotes genetic drift and minimizes the chance of selection for just one or a few potentially most-fit genotypes.

It is not known when H. pylori became human adapted. One theory proposes that its association with humans is truly ancient, that H. pylori infection has been near universal in humans and in our nonhuman primate ancestors for perhaps millions of years (6). This proposal was used in developing a controversial idea that chronic H. pylori infection and the gastritis accompanying it might be quite normal and, thus, it bears on discussions of whether H. pylori eradication should or should not be a societal goal (6). Our alternative theory (29) proposes that H. pylori infection became widespread in humans more recently, perhaps in early agricultural societies, some 10,000 years ago. As with the jumps of other pathogens in humans, this might have been promoted by the increased contact with animals, the higher population density, and the poorer sanitation in agricultural communities than in bands of hunter-gatherers (10, 29). The potential of H. pylori to surmount barriers between host species is illustrated by the many reports of human H. pylori strains adapted to mice and other mammals (11, 18, 19, 31, 42). The present study of H. pylori's close relative, H. acinonychis, was motivated by interest in understanding the control and specificity of infection, of how and when H. pylori may have become widespread in humans, and by the potential value of comparing related Helicobacter species in this context.

Earlier studies had shown that H. acinonychis could infect domestic cats (13), as can certain H. pylori strains (39), although an attempt to infect BALB/c mice was not successful (13). Part of a putative adhesin gene of H. acinonychis (hxaA) was 83% matched to that of H. pylori (hpaA [14]), and point mutations could be moved between H. pylori and H. acinonychis by DNA transformation in culture (40). Here we characterize sequence relationships of H. acinonychis isolates from captive big cats from North America and Europe to each other and to human H. pylori, identify two distinct groups of strains, and select H. acinonychis derivatives that can chronically infect mice either alone or in combination with certain H. pylori strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Helicobacter strains and culture.

Ten veterinary isolates of H. acinonychis were studied here. Six, named 89-2579, 90-119, 90-548, 90-624, 90-736, and 90-788, were from cheetahs with gastritis in the Columbus (Ohio) Zoo. HindIII digest genomic DNA profiling had indicated that these isolates were closely related to one another (12, 13). Four additional H. acinonychis strains were from animals in a European Circus: two from lions (named Sheeba and Mac), one from a tiger (named India), and one from a lion-tiger hybrid (named Sheena) (8, 40; G. Cattoli and J. G. Kusters, unpublished data). Each of these big cats was born in captivity. The six zoo animals may have been in contact with one another, directly and/or via handlers, utensils, etc., as may have been the four circus animals. To our knowledge, however, there had been no contact between the big cats in the United States and those in Europe, and it is not known when their ancestors were captured in the wild.

Five mouse-adapted strains of H. pylori were used here: SS1 (31, 36); X47 (also known as X47-2AL [2, 15]); 88-3887, a close relative of strain 26695 (24, 27, 34), whose genome has been fully sequenced (47); and AM1 from India and AL10103 from Alaska (D. Dailidiene, A. K. Mukhopadhyay, M. Zhang, and D. E. Berg, unpublished data).

Helicobacter strains were grown in a gas-controlled incubator under microaerobic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N2) at 37°C, usually on brain heart infusion agar (Difco) supplemented with 7% horse blood, 0.4% IsoVitaleX, and the antibiotics amphotericin B (8 μg per ml), trimethoprim (5 μg per ml), and vancomycin (6 μg per ml). Nalidixic acid (10 μg per ml), polymixin B (10 μg per ml), and bacitracin (200 μg per ml) were added to this medium when culturing Helicobacter isolates from mouse stomachs. H. acinonychis isolates were tested for susceptibility to metronidazole (MTZ) by spotting aliquots of diluted cultures containing, variously, 103 to 106 cells (10-fold dilutions) on media with fixed concentrations of antibiotics, as described elsewhere (9, 26). Tests for susceptibility to other antibiotics (tetracycline [Tet], clarithromycin [Cla], and chloramphenicol [Cam]) were carried out similarly but by spotting only about 106 cells on drug-containing media.

Strains carrying rRNA resistance mutations were constructed by transformation with 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) containing TTC in place of AGA at position 965 to 967 for Tet resistance (9) and 23S rDNA containing G in place of A at position 2144 for Cla resistance (49). Strains carrying vacA::cat (K. Ogura and D. E. Berg, unpublished data) and rdxA::cat (26) (chloramphenicol resistance) mutations were similarly generated by transformation (26) as needed.

Mice.

Mice of three inbred lines were used here: C57BL/6J wild type; the congenic C57BL/6J interleukin-12β (IL-12β; p40 large subunit) homozygous mutant knockout line; and BALB/cJ (all from Jackson Laboratories [hence, “J” designation], Bar Harbor, Maine). These mice were maintained in the Washington University Medical School Animal Quarters (Animal Welfare Assurance A-3381-01) with water and standard mouse chow ad libitum and used in protocols approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee (approval 20010039).

Experimental infection.

Helicobacter cultures were grown overnight on brain heart infusion agar and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline at densities of approximately 2 × 109 CFU per ml. A 0.5-ml aliquot of this suspension was used for each inoculation. In cases of mice inoculated with two strains, the 0.5-ml suspension contained an equal amount of each strain (final concentration, 2 × 109 CFU per ml). To score colonization, mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation and cut open with clean sterile scissors immediately after; their stomachs were removed and cut longitudinally along the lesser curvature, and any gastric contents were removed with clean, sterile forceps. The forestomach (not a major site of H. pylori colonization), which was identified as a rather thin structure that is separated from the corpus by a white line, was removed and discarded. The remainder of the stomach was homogenized, and the homogenate or dilutions of it were spread on agar medium.

DNA methods.

Helicobacter genomic DNAs were isolated from confluent cultures grown on agar medium using a QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen Corporation, Chatsworth, Calif.). Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprint analysis was carried out essentially as described previously (4) in 25-μl reaction mixtures containing either 5 or 20 ng of genomic DNA (to assess reproducibility of patterns), 5 mM MgCl2, 20 pmol of each of four arbitrary primers (Table 1), a 0.25 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 1 U of Biolase thermostable DNA polymerase (Midwest Scientific, St. Louis, Mo.) in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl under the following cycling conditions: 45 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 36°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min.

TABLE 1.

Primers for PCR and sequencing

| Gene | Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Length of PCR fragment (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| glmM (ureC) | glmM F | 5′-TTTGGGACTGATGGCGTGAGGG | 1,303 |

| glmM R | 5′-TCTTTTAATTCTTGCATTTTGGATTCTA | ||

| recA | recA1 F | 5′-GCGTTGGTACGCCTTGGGGATAAGCAA | 833 |

| recA4 R | 5′-GCCTTGCCCTAGCTTTTTATCCTGGT | ||

| hp519 | 519 F1 | 5′-GGCTTTTTCATAGCCAAATTCTGCG | 740 |

| 519 R1 | 5′-GTTGCCGTTTTCRCTTTGTATAGCT | ||

| picB | cagE-F | 5′-CACTCTCAATGAACCCGTTATG | 700 |

| cagE-R | 5′-GACGCATTCCTTAACGCTTTGT | ||

| picA | cagD-F | 5′-CATAAGAATTGAATACGGCCAATA | 1,000 |

| cagAR-0429 | 5′-TAGTGGTCTATGGAGTTG | ||

| glr | 5733 | 5′-CACATCGCCGCTCGCATGA | 800 |

| 6544 | 5′-AAGCTTTGTGTATTCTAAAATGCAAC | ||

| ppa | ppa8 | 5′-CCCCTAGAAAATCCTATTTTGATAATC | 902 |

| ppa9 | 5′-AGTGGTGAGCTTTAGCGACGCTC | ||

| cysS | cysS-F | 5′-CTACGGTGTATGATGACGCTCA | 1,287 |

| cysS-R | 5′-CCTTGTGGGGTGTCCATCAAAG | ||

| atpA | atpA1 | 5′-GCTTAAATGGTGTGATGTCG | 1,200 |

| atpA6 | 5′-CTTATTCGCCCTTGCCCATT | ||

| vacA | cysS-F2b | 5′-TGATGGACACCCCACAAGG | 530 |

| va1-R | 5′-CTGCTTGAATGCGCCAAAC | ||

| 2579-F2b | 5′-AGGTGTCGCTTCAAGAACAGCCGG | 1,580 | |

| 2579-R2 | 5′-GAGCATTTTCCCGCACTCATACCATG | ||

| 2579-F3b | 5′-GTGTGGATGGGCCGTTTGCAATAT | 1,000 | |

| 2579-R2 | 5′-GAGCATTTTCCCGCACTCATACCATG | ||

| Vam-Fb | 5′-GGCCCCAATGCAGTCAGTGAT | 706 | |

| Vam-R | 5′-GCTGTTAGTGCCTAAAGAAGCAT | ||

| vac6-Fb | 5′-TAATAGAGCAATTCAAAGAGCGCC | 790 | |

| vac6-R | 5′-CCAAAHCCDCCYACAATRGCTT | ||

| vac7-Fb | 5′-CCAATGTTTGGGCTAACGCTATTGG | 950 | |

| vac7-R | 5′-GCRYGGKTTTAAGACCGGTATTT | ||

| vacAs | va1-F | 5′-ATGGAAATACAACAAACACAC | s1,259 |

| va1-R | 5′-CTGCTTGAATGCGCCAAAC | s2,286 | |

| vacAs | vac5-Fc | 5′-GTGTCGCTTCAAGAACAGC | 100 |

| vac5-R | 5′-CCCAACCCTAATCTCYTTG | ||

| vacAmd | vam-F | 5′-GGCCCCAATGCAGTCAGTGAT | 706 |

| vam-R | 5′-GCTGTTAGTGCCTAAAGAAGCAT | ||

| vacAm2e | va4-F | 5′-GGAGCCCCAGGAAACATTG | 352 |

| va4-R | 5′-CATAACTAGCGCCTTGCAC | ||

| flaA | flaA-F | 5′-AAGAATTYCAAGTDGGKGCTTATTYTAAC | 870 |

| flaA-R | 5′-TTTTTGCACAGAACCYAARTCAGAKCGSAC | ||

| flaB | flaB-F | 5′-TTTWCTAAYAAAGAATTTCAAATYGGHGCG | 675 |

| flaB-R | 5′-CTGAARTTCACVCCGCTCACRATRATGTC | ||

| cag empty site | luni1 | 5′-ACATTTTGGCTAAATAAACGCTG | 535 |

| r5280 | 5′-GGTTGCACGCATTTTCCCTTAATC | ||

| cag empty site | luni 1 | 5′-ACATTTTGGCTAAATAAACGCTG | 850 |

| P4 | 5′-GCTTTGGATTTTTTCAAACCGCA | ||

| 16s rDNA | 16s-F | 5′-CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTTCAC | 1,400 |

| 16s-R | 5′-TATGGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTC | ||

| RAPD primers | |||

| 1254 | 5′-CCGCAGCCAA | ||

| 1281 | 5′-AACGCGCAAC | ||

| 1283 | 5′-GCGATCCCCA | ||

| 1290 | 5′-GTGGATGCGA |

For mixed bases, the following code was used: A/G = R, A/C = M, A/T = W, G/O = S, G/T = K, C/T = Y, A/G/O = V, A/G/T = D, A/C/T = H, G/C/T = B, A/G/C/T = N. Not shown here are sequences of additional standard cag PAI primers, designed from known H. pylori sequences (5, 47) and used to test for the possible presence of any cag genes (but for which no amplification was obtained), as detailed in the text. Sequences are available from authors on request.

Series of primer pairs used for vacA H. acinonychis sequencing.

Primer specific for H. acinonychis.

For PCR amplification of vacA mid-region; each primer was used for sequencing.

For vacA m2.

Gene-specific PCR was carried out in 20-μl volumes containing 5 to 10 ng of DNA, 0.25 to 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (Biolase; Midwest Scientific), 2.5 pmol of each primer (Table 1), and a 0.25 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, in a standard buffer for 30 cycles with the following cycling parameters: denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing generally at 52°C (low stringency, to compensate for possible mismatches with H. acinonychis sequences) for 30 s, and DNA synthesis at 72°C for an appropriate time (1 min per kb). PCR products for sequencing were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen) or extracted from agarose by centrifugation with Ultrafree-DA (Amicon, Millipore). DNA sequencing was carried out using a Big Dye Terminator DNA sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer) and ABI automated sequencers. Direct sequencing of PCR products was done with 5 μl of PCR fragment (about 100 ng of DNA), 1 μl of primer (1.6 pM), and 4 μl of Big Dye under the following conditions: 25 cycles of denaturation at 96°C for 10 s, annealing at 50°C for 5 s, and extension at 60°C for 4 min under oil-free conditions (Perkin-Elmer 2400). DNA sequence editing, alignment, and analysis were performed with the Vector NTI suite of programs (Informax, Bethesda, Md.) and with programs and data in the H. pylori Genome Sequence Databases (5, 47) and Blast and pfam (version 5.3) homology search programs (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/blast.cgi; http://pfam.wustl.edu/hmmsearch.shtml). Diversity within and between taxa were analyzed using MEGA 2.1 (30). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the neighbor-joining approach as implemented in PAUP version 4b10 (D. Swofford, Sinauer Associates). To determine the significance of observed groupings in the phylogeny, bootstrap analysis (PHYLIP Phylogeny Inference Package, version 3.573c; J. Felsenstein, Department of Genetics, University of Washington, 1993) was performed with 1,000 replicates in a neighbor-joining (41) environment, with Jukes-Cantor two-parameter distances as implemented in PAUP version 4b10 or/and PHYLIP version 3.573c.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences analyzed in this study were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under accession numbers AY269142 to AY269185. The primers used for PCR and sequencing are listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic relationships.

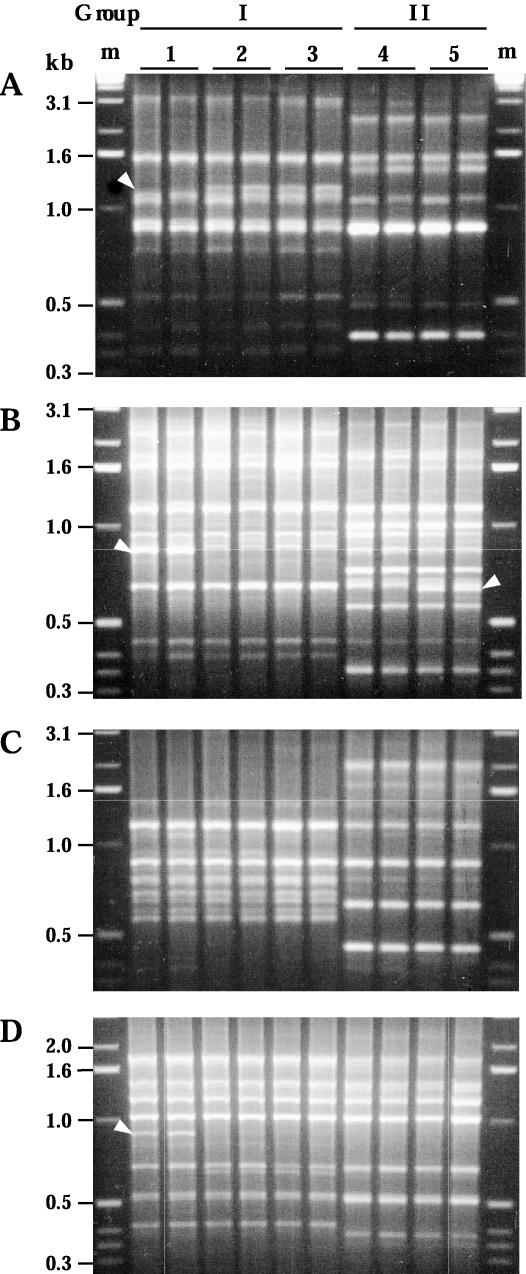

We studied H. acinonychis isolates from six cheetahs from a zoo in Ohio and from two lions, a tiger, and a lion-tiger hybrid from a European circus. Two H. acinonychis groups were identified by RAPD fingerprinting (Fig. 1). Group I contained all isolates from the cheetahs from the Ohio zoo and also two lions from the European circus; group II contained isolates from the tiger and the lion-tiger hybrid from the same circus. Two variants were found among group I isolates, differing reproducibly in 3 of 34 bands that were generated with four RAPD primers (Fig. 1). The two group II isolates also differed slightly but reproducibly from one another (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

RAPD fingerprinting identified two groups of H. acinonychis strains. Profiles shown were obtained with RAPD primers 1247 (A), 1254 (B), 1281 (C), and 1283 (D). With each DNA sample, RAPD tests were run with 5 ng (left lane) and with 20 ng (right lane) of template DNA to identify subtle differences that are reproducible and thus informative. Arrowheads identify bands that distinguish different strains of the same group. Lane pairs 1, 2, and 3 contain profiles of group I isolates (cheetah strain 89-2579, Mac, and Sheebah, respectively); lane pairs 4 and 5 contain profiles of group II isolates (Sheena and India, respectively). The profiles of cheetah strain 89-2579 shown here are representative of those obtained from other cheetah isolates,except for strain 90-548, which reproducibly yielded one extra band (1.1 kb) with primer 1254. m, marker DNA.

Lack of cag PAI.

Two sets of PCR tests indicated that H. acinonychis strains lack the cag pathogenicity island (PAI). First, no amplification was obtained with DNAs from group I or group II strains with sets of primers specific for the cagA gene nor for any of 11 other cag PAI genes (picA and picB, also near the right end, and hp520, hp522, hp524, and hp526-hp531 at or near the left end [47]). Although the cagA gene is so diverse in H. pylori populations that a lack of PCR amplification might be considered inconclusive (48, 52), an equivalent lack of amplification with all other cag PAI genes tested seemed definitive. This reasoning is based primarily on the following: (i) our sequence analyses of three other cag PAI genes (hp520, picA, and picB) in a global H. pylori strain collection and the finding that they were no more diverse than housekeeping (metabolic) genes (G. Dailide, M. Ogura, and D. E. Berg, unpublished data), which were readily amplified from H. acinonychis DNA (see below); and (ii) a sense that most genes whose proteins act internally in bacterial cells, unlike cagA, should not have been subject to diversifying selection. Second, as independent evidence that H. acinonychis does not contain the cag PAI, PCR products of sizes expected for cag PAI empty sites were obtained using primers specific for flanking genes (hp519 and glr; 0.53 and 0.85 kb, depending on primers used). Sequences from these products (GenBank accession numbers AY269155 and AY269157) were 91% matched to one another and 93% matched (group I) and 86% matched (group II) to corresponding empty sites of H. pylori clinical isolates that also lack the cag PAI (GenBank accession nos. AF084492 and AF084493, respectively). We conclude that these H. acinonychis strains lack a cag PAI.

vacA status.

PCR products were obtained from both groups of H. acinonychis isolates with primers that are specific for relatively conserved sites in the middle region of the vacA gene (vam-F and vam-R; Table 1). Products were also obtained with primers specific for the 5′ end (signal sequence region; va1-F and va1-R), although these products were 240 and 121 bp long (group I and II isolates, respectively), not 259 or 286 bp, which are obtained with H. pylori vacA s1 or s2 alleles, respectively (Table 1).

The sequence of a 4,006-bp DNA fragment containing the vacA gene from a group I strain (89-2579, from a cheetah) was determined (GenBank accession no. AY269171). It was 84% identical to the most closely related of currently available (as of July 2003) H. pylori vacA sequences (GenBank accession no. AF050327; strain CHN5114a). It differed from this H. pylori sequence by nine insertions and eight deletions ranging from 3 to 59 bp and ∼43 translational stops (due variously to out-of-frame insertions and deletions and base substitutions [nonsense codons]). The first 2.2 kb of vacA from a group II strain (Sheena) was also sequenced (GenBank accession no. AY269176). It differed from the corresponding part of the group I vacA sequence by 5.8% base substitutions and 11 insertions and deletions and from the corresponding part of the vacA sequence of H. pylori strain CHN5114a by 13 insertions and deletions and 22% base substitutions. The many disruptions of vacA open reading frames indicated that these vacA genes would not encode an active vacuolating cytotoxin or a full-length VacA protein.

Additional sequencing of vacA-containing segments from the two group I strains from lions in Europe (724 bp of the vacAs region from Sheeba; 996 bp of vacAs and 664 bp of the vacAm regions from Mac) identified only a 1-bp difference from the sequence of the U.S. cheetah strain (in the vacAs segment). This near-identity suggests that vacA-null alleles existed while these H. acinonychis strains infected big cats and were not artifacts of laboratory culture.

Relatedness assessed with functional genes.

Further sequence analyses were carried out using nine genes that are probably needed in vivo and thus likely to be intact, not inactivated by mutation: six housekeeping genes (glr, just to the right of the cag PAI; cysS, just upstream of vacA; and glmM, recA, atpA, and ppa), the flaA and flaB flagellin genes, and hp519, a putative regulatory gene just to the left of the cag PAI. PCR products of sizes expected based on H. pylori sequences were obtained for each gene from both groups of H. acinonychis strains. Because the primers used had been designed from H. pylori sequences, all amplification was carried out with low-stringency (52°C) annealing. The sequences of PCR products obtained from group I and II isolates differed from one another by about 1.8%, on average (Table 2). However, identical sequences were found in 645 bp of flaA and in all but 142 of the 1,080 bp of atpA (Table 2). These matches were noteworthy because identical sequences are only rarely found in independent H. pylori isolates. In addition, sequences identical to those of the U.S. cheetah strain (group I) were found in all genes sequenced from the European group I strains (glmM, recA, hp519, glr, cysS, and atpA from Mac; glmM and atpA from Sheeba). Similarly, the two group II strains were identical at all but 1 bp in the five genes sequenced from both of them (glmM, recA, hp519, glr, and cysS). Thus, these sequence and RAPD profile data (Fig. 1) each showed that these 10 H. acinonychis isolates belong to just two major lineages.

TABLE 2.

DNA sequence relationships of group Ia and group IIa H. acinonychis strains to each other and to a reference H. pylori straina

| Comparison | % Identity with gene (sequence length [bp])

|

Avg | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glmM (648) | flaB (615) | recA (642) | hp519 (726) | glr (768) | flaA (645) | cysS (659) | atpA (1,080) | ppa (427) | ||

| Cheetah (I) vs 26695 | 91.8 | 89.8 | 93.6 | 91.9 | 91.7 | 91.3 | 93.4 | 93.7 | 93.7 | 92.4 |

| Sheena (II) vs 26695 | 91.9 | 88.8 | 93.6 | 91.2 | 91.1 | 91.3 | 93.6 | 93.5 | 92.7 | |

| Cheetahb (I) vs Sheena (II) | 97.9 | 97.7 | 98.7 | 95.6 | 97.3 | 100 | 97.5 | 99.3c | 97.2 | 98.2 |

Group I and group II refer to sets of H. acinonychis strains with the different RAPD profiles illustrated in Fig. 1 and described in the text; 26695 is a reference strain of H. pylori whose genome has been fully sequenced.

Cheetah refers to strain 89-2579 from a cheetah. However, where tested, identical corresponding sequences were found in isolates from other cheetahs as well.

Divergence in atpA consists of 7 nt substitutions in 142 bp of the 1,080 bp sequenced.

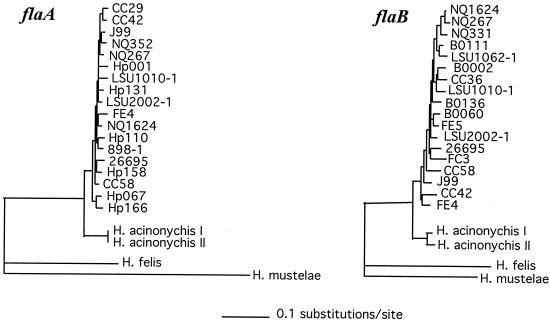

The H. acinonychis genes, other than vacA, that were analyzed were about 8% divergent from homologs in H. pylori reference strains such as 26695 (47) and J99 (5). The close, but distinct, species relationship between H. acinonychis and H. pylori is further illustrated by comparison of flaA and flaB gene sequences (Fig. 2). We note that two of the genes analyzed here, ppa and atpA, had also been studied in an unusual outgroup of H. pylori strains from South Africa (17). The ppa and atpA sequences from H. acinonychis were more closely related to those of the South African H. pylori outgroup (4.7% DNA divergence, on average) than either the H. acinonychis or outgroup sequences were to those of most other known H. pylori strains, including reference strains 26695 and J99 (divergences of 6.6 and 7.6% between sequences from reference H. pylori strains versus outgroup H. pylori strains and versus H. acinonychis, respectively).

FIG. 2.

The neighbor-joining tree of Helicobacter flagellin genes inferred from DNA sequences confirmed the separate species groupings of H. acinonychis strains. The H. acinonychis sequences were determined here. All other sequences are from the GenBank public database. Left, FlaA; right, FlaB.

Susceptibility to MTZ.

Resistance to the important anti-Helicobacter drug MTZ is common among strains of both H. acinonychis and H. pylori (8, 13, 26), probably in part because it is also much used against anaerobic and parasitic infections. The susceptibility or resistance of each H. acinonychis isolate to MTZ was characterized, in part, to help choose Mtzs strains for mouse infection studies (below). Two of the six Ohio zoo isolates and three European circus isolates were MTZ sensitive (MIC = 1.5 μg of MTZ/ml [or in one case, 3 μg of MTZ/ml]), and the other five isolates were moderately or highly resistant (MIC range from 8 to 128 μg of MTZ/ml) (Table 3). Two types of Mtzs H. pylori are known and can be distinguished by the ease of mutation to resistance: type I requires inactivation of just the rdxA nitroreductase gene (because the related frxA gene is quiescent), and type II requires inactivation of both rdxA and frxA (26, 34). The three mouse-colonizing strains of H. pylori characterized to date (SS1, X47, and 88-3887) are each type II (26, 34). Camr transformants of Mtzs H. acinonychis isolates were generated using an rdxA::cat (null) allele from H. pylori. Each Camr transformant was Mtzr, with MTZ MICs of 32 and 16 μg per ml in group I and II strains, respectively (Table 3), suggesting that the frxA nitroreductase gene is either quiescent or absent from these strains. The small differences in MICs were reproducible and suggested quantitative differences in parameters such as basal levels of other nitroreductases, of MTZ uptake, or of repair of MTZ-induced DNA damage (see references 26 and 34).

TABLE 3.

MTZ susceptibility profiles of H. acinonychis strains

| Strain | RAPDa group | MIC (μg of MTZ/ml)b for:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | rdxA::cat (null) | ||

| 89-2579 | I | 1.5 | 32 |

| 90-624 | I | 1.5 | 32 |

| 90-736 | I | 16 | NT |

| 90-548 | I | 32 | NT |

| 90-119 | I | 128 | NT |

| 90-788 | I | 128 | NT |

| Mac | IA | 1.5 | 32 |

| Sheeba | IA | 1.5 | NT |

| Sheena | II | 3 | 16 |

| India | II | 8 | 16 |

RAPD groups are defined in the legend for Fig. 1. The subtle differences in RAPD profiles between group I strains from cheetahs in a U.S. zoo and the strains from lions in a European circus (here designated group IA) are also illustrated in Fig. 1.

In the present usage, MIC indicates the lowest concentration of MTZ used that resulted in at least a 100-fold reduction in efficiency of colony formation. WT, wild type; NT, not tested.

Adaptation to mice.

An earlier effort to achieve H. acinonychis infection of BALB/c mice was not successful (13). Here, we also attempted to isolate mouse-colonizing H. acinonychis strains, but this time we used IL-12β-deficient C57BL/6J mice, which seem more permissive than congenic wild-type C57BL/6J or BALB/c mice for H. pylori (19, 24, 36), and pools of isolates, rather than just a single strain, to avoid possible problems of strain attenuation in culture. H. acinonychis organisms were recovered 2 weeks after inoculation from each of four mice that had received Mtzs group I strains (89-2579 and 90-624; Sheeba and Mac) (20 to 500 CFU per stomach) and also from two of four mice that had received group II strains (India and Sheena) (about 2,000 CFU per stomach). These pools of recovered H. acinonychis organisms were used in a second inoculation of IL-12β-deficient mice; 1,000 to 3,000 CFU were recovered 2 weeks later from each of 10 mice (5 inoculated with each H. acinonychis group). No further increase in bacterial yield was seen after a third cycle of infection of IL-12β-deficient mice. RAPD fingerprinting, as shown in Fig. 1, suggested that these mouse-adapted strains were derived from a cheetah isolate (group I) and from Sheena (group II). These strains, now adapted to IL-12β-deficient mice, were used to inoculate wild-type C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice: 1,000 to 3,000 CFU were obtained per C57BL/6J mouse stomach at 2 weeks and also at 12 weeks after inoculation (five mice per time point per strain); 1,000 to 3,000 CFU and 500 to 1,000 CFU were obtained per BALB/cJ mouse stomach inoculated with group I and group II strains (five mice in each group). Thus, H. acinonychis strains selected initially for colonization of C57BL/6J IL-12β-deficient mice were also well suited for infection of two other wild-type lines (C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ).

H. acinonychis-H. pylori mixed infection.

The similar genetic distances of H. acinonychis and the African H. pylori outgroup to other H. pylori strains, the ease of DNA transformation between the two species in culture, and interest in evolutionary consequences of interspecies gene transfer led us to test for mixed infection in vivo. In the first test, mice were inoculated with H. acinonychis and also SS1 or X47, H. pylori strains that colonize mice at high density but at different preferred gastric sites (SS1 in the antrum, X47 in the corpus) (2). Mice were sacrificed 2 weeks later, gastric contents were cultured, and single colonies were tested by PCR or by susceptibility when SS1 was marked genetically (Tetr) to distinguish the two species. Based on these tests, only 6 of 336 colonies from the mixed inoculation with SS1 were of the H. acinonychis type; similarly, just 1 of 96 colonies from the mixed inoculation with X47 was of the H. acinonychis type (Table 4). A sequential inoculation protocol was used next, to assess if the low yield of H. acinonychis might be due primarily to inefficient initiation of infection. A vacA-null (Camr) derivative of H. pylori strain SS1 was used because vacA is needed by this strain to initiate infection efficiently but not to maintain it after the first few critical days (42). Mice were inoculated with group II H. acinonychis first and then with H. pylori 1 week later; the mice were sacrificed and Helicobacter was cultured from them 2 weeks after superinfection. All but 6 of 230 single colonies tested (at least 20 per mouse) was resistant to chloramphenicol, indicating that most were of the SS1 vacA-null type (Table 4). Equivalent sequential inoculation tests were carried out using a Clar derivative of strain X47; all but 14 of 284 colonies tested was similarly of the Clar X47 type (Table 4). These results emphasized that H. pylori strains SS1 and X47 can each outcompete H. acinonychis, even if inoculated a week after the H. acinonychis infection has started.

TABLE 4.

H. pylori strains SS1 and X47 outcompete H. acinonychis

| Input

|

No. of colonies recovered

|

No. of mice | Single-colony test method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. acinonychis | H. pylori | H. acinonychis | H. pylori | ||

| Tests of single colonies | |||||

| I | SS1 WTa | 0b | 48 | 4 | PCR |

| I | SS1 Tetr | 2 | 118 | 4 | Phenotype |

| II | SS1 WT | 1b | 47 | 4 | PCR |

| II | SS1 Tetr | 3 | 117 | 4 | Phenotype |

| I | X47 WT | 0b | 48 | 4 | PCR |

| II | X47 WT | 1b | 47 | 5 | PCR |

| Sequential infectionc | |||||

| II | SS1 vacA::cat | 6 | 230 | 9 | Phenotype |

| II | X47 Clar | 14 | 284 | 9 | Phenotype |

WT, wild type.

PCR tests using pools of >1,000 colonies and primers vac5-1-F and vac5-1-R indicated that H. acinonychis was also present in each mixed infection.

Mice received H. acinonychis first and then H. pylori superinfection 1 week later.

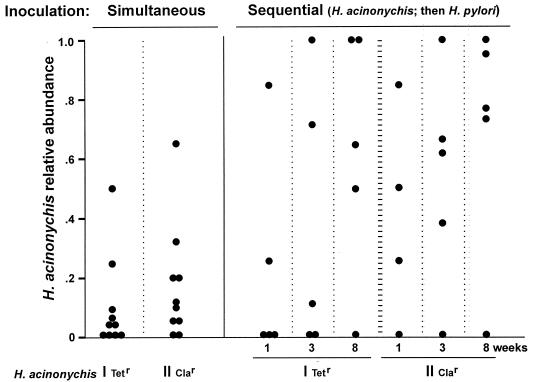

Given H. pylori's genetic diversity, it seemed that other mouse-adapted strains might be less vigorous or differ in tissue tropism from strain SS1 or X47 and, therefore, be able to establish a more balanced mixed infection with H. acinonychis. This was tested first by inoculating mice with genetically marked derivatives of H. acinonychis (Tetr group I, Clar group II) and of H. pylori strain 88-3887 (Camr; rdxA::cat) and scoring the types of helicobacters recovered 2 weeks later by drug resistance patterns. Figure 3 (left panel) shows that H. acinonychis was recovered from 14 of 20 mice coinoculated with these two species. Similar mixed infections were obtained after coinoculation with H. acinonychis group I and either of two other mouse-adapted H. pylori strains (AM1 and AL10103) (data not shown), indicating that the ability to coexist with H. acinonychis is not unique to strain 88-3887.

FIG. 3.

Mixed infections resulting from simultaneous and sequential inoculations with genetically marked H. acinonychis and H. pylori. The mutations conferring resistance to Tet and to Cla are in 16S and 23S rDNAs, respectively (9, 49). Cam resistance is conferred by a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene (cat) inserted in the rdxA nitroreductase gene of H. pylori strain 88-3887 (25, 34). Frequencies of each strain type were estimated by testing ≥20 single colonies per mouse for antibiotic susceptibility and also by colony counts on selective agar. Weeks refers to time between superinfection and mouse sacrifice and culturing of Helicobacters that they harbored.

A final set of coinfection studies was carried out by first inoculating mice with Tetr or Clar H. acinonychis, superinfecting them with Camr 88-3887 1 week later, and scoring the types of helicobacters recovered at 1, 3, and 8 weeks after superinfection. Much as with simultaneous inoculations, persistent mixed infections were found in just over half of the mice examined (Fig. 3, right): 5 of 9 mice scored at 1 week, 5 of 10 scored at 3 weeks, and 6 of 10 scored at 8 weeks after superinfection.

Variants accumulated during 8 weeks of mixed infection.

One Tets derivative of H. acinonychis group I and one Cams derivative of H. pylori were found among 337 Helicobacter colonies recovered 8 weeks after superinfection and screened for drug susceptibility (66 group I and 72 group II H. acinonychis; 199 H. pylori) (experiment in Fig. 3, right) (species of two susceptible isolates were identified by RAPD test). Analysis of the 16S rDNA sequence of the Tets isolate indicated that it arose by interstrain recombination involving the 16S rDNA genes: a replacement of a short patch in H. acinonychis (less than 137 bp) containing TTC (resistant allele) by AGA (sensitive allele) at positions 965 to 967. In contrast, PCR tests of the Cams H. pylori variant with rdxA- and cat-specific primers revealed only a normal-length rdxA::cat insertion allele, not an intact rdxA allele. In addition, Camr revertants of this Cams rdxA::cat strain were obtained at frequencies of about 10−6. No equivalent Camr mutants were detected among 108 cells of an isogenic control strain that lacks cat gene sequences. We therefore infer that this variant arose by mutation, not by replacement of the rdxA::cat allele with the intact rdxA gene of H. acinonychis.

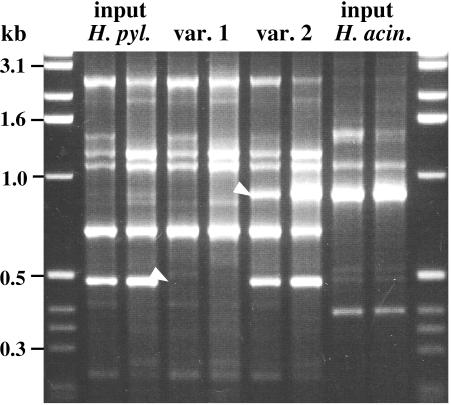

Two other variants, both H. pylori, were found by RAPD fingerprinting of 39 isolates (23 H. pylori; 6 group I and 10 group II H. acinonychis; Fig. 3, right); the primer 1247 profile of one variant lacked a characteristic ∼0.5-kb RAPD band, and that of the other contained an extra ∼0.9-kb band that comigrated with a characteristic H. acinonychis band (Fig. 4). No other difference from the input H. pylori strain was found in RAPD tests with any of four RAPD primers.

FIG. 4.

RAPD fingerprinting (primer 1247) identified two variant H. pylori strains isolated after 2 months of mixed infection with H. acinonychis in C57BL/6J IL-12β knockout mice. With each DNA sample, RAPD tests were run with 5 ng (left lane) and with 20 ng (right lane) of template DNA, as for Fig. 1. White arrowheads identify bands that distinguish variants. m, marker DNA.

DISCUSSION

Two groups of H. acinonychis strains were identified: one group consisting of isolates from six cheetahs from a U.S. zoo and two isolates from lions from a European circus, and the other group consisting of isolates from two other felines (a tiger and a lion-tiger hybrid) from the same circus. The two groups differed from one another by about 2% in gene sequence, on average, but were identical in one gene (flaA) and in most of another (atpA), a pattern suggesting recombination between lineages. Such exchange might have occurred during mixed infection in captivity, perhaps following direct contact between infected animals or transmission by human handlers. More remarkable, from an H. pylori perspective, was the near-identity of H. acinonychis isolates from the United States and Europe, since any given H. pylori isolate is usually easily distinguished from other independent isolates by the DNA tests used here (4, 17). Having so few H. acinonychis genotypes implies disproportionate contributions from very few index cases (a genetic bottleneck) and/or a far more epidemic mode of transmission of H. acinonychis in captive big cats than of H. pylori in humans.

Derivatives that could chronically infect mice were readily obtained from each H. acinonychis group using C57BL/6J IL-12β knockout mice as initial hosts and C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ wild-type mice later. H. acinonychis was so-named because it was first isolated from cheetahs (12, 13), and it is associated with severe gastritis, a frequent cause of their death in captivity (8, 12, 13, 35). H. acinonychis' ability to infect other felids (illustrated by the present lion and tiger isolates) and mice raises questions about its host range in nature. Are cheetahs or other big cats necessarily its only, or even most common, natural host? Or, might H. acinonychis also often infect other carnivores and/or even the herbivores on which they prey?

Any flexibility in Helicobacter host range bears on discussions of how and when H. pylori became a human pathogen (7). The popular ancient-origins theory envisions near-universal H. pylori infection in hominids for perhaps millions of years (6, 17). Our alternative theory envisions H. pylori infection of humans becoming widespread more recently, perhaps in early agricultural societies (29), facilitated by close animal-human contact and increased chances for person-to-person spread (10). The ease of adapting H. pylori to mice and other animals (11, 18, 19, 21, 31, 39) illustrates again that potential host species barriers are easily surmounted. Also noteworthy is an unusual outgroup of H. pylori strains from Africa, some 7% divergent from the more-abundant groups of H. pylori strains in housekeeping gene sequences (17). Although initially interpreted as representing an ancient H. pylori lineage sequestered until recently in a very isolated group of humans (17), this H. pylori outgroup seemed more closely related to H. acinonychis than either it or H. acinonychis were to predominant H. pylori groups. Thus, the data also fit with a model in which the ancestors of this H. pylori outgroup jumped from animals to people recently during human evolution. By extrapolation, the more-abundant groups of human-adapted H. pylori strains might also have been acquired quite recently by humans.

H. pylori strains SS1 and X47 were far more fit than H. acinonychis in mice: even after H. acinonychis had begun to establish itself, it was displaced soon after superinfection by these stronger H. pylori strains. In accord with this finding are preliminary observations that these two strains each also outcompete strain 88-3887 (M. Zhang, D. Dailidiene, and D. E. Berg, unpublished data). In further tests using strains that were genetically marked (for efficiency in scoring many colonies), derivatives of H. acinonychis (Tetr or Clar) were able to establish mixed infections with derivatives of H. pylori 88-3887 (rdxA::cat; Camr) and also with two other mouse-adapted H. pylori strains (AM1 and AL10103). In a sequential-infection experiment, half of the mice inoculated first with H. acinonychis and then H. pylori 88-3887 a week later harbored quite similar levels of the two species 8 weeks after superinfection. We suggest that such experimental mixed infections may provide good models for understanding the human condition, especially in many developing countries, where risks of infection are high for children and also for adults (23, 44).

Two cases of genetic change were detected among 337 single-colony isolates that were tested for drug resistance markers: a loss of tetracycline resistance from H. acinonychis by interstrain recombination and a loss of chloramphenicol resistance from H. pylori, but by mutation not recombination. This one case of mutation (among only 199 H. pylori isolates) was unexpected, but it is in accord with other indications that mutation can be frequent in this species (50). Two changes in the RAPD profile were also found in the screening of 39 isolates: one gain of an H. acinonychis-like RAPD band and one loss of a characteristic H. pylori band. Precedent suggests that these two variants may have arisen by interstrain recombination (28), although the possibility of a mutational origin also merits consideration.

People, like other mammalian hosts, are diverse in traits that can be important to individual H. pylori strains—for example, in distribution or abundance of carbohydrate structures that H. pylori uses for adherence, in gastric acidity, in the repertoire of host defenses, and in the history of other infections that in turn affect host responses to H. pylori (11, 20, 25, 33). H. pylori, in turn, is extraordinarily diverse genetically, in part probably because of legacies of diversifying selection in a succession of hosts and because of transmission patterns that minimize chances of population-wide selection for any one or a few most-fit genotypes. Given H. pylori's great genetic diversity, an important challenge will be to identify those polymorphic determinants in helicobacters that contribute to colonization and disease—a bacterial counterpart of the quantitative trait loci that determine many aspects of the phenotypes of humans and other higher organisms (32). We suggest that H. acinonychis may have just the right mix of moderate genetic distance from and similarity in physiology and gastric tropism to H. pylori for such studies. Mouse-adapted H. acinonychis should be valuable as a resource for analysis of the interplay between Helicobacter and its host that shapes the specificity and vigor of infection, the risks of various types of disease, and the evolutionary trajectories that may result.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Hoffman, Tatyana Golovkina, and Mark Jago for stimulating discussions.

This research was supported by grants from the U.S. Public Health Service to D. E. Berg (AI38166, DK53727, and DK63041), to K. Eaton (R01 AI43643 and R01 CA67498), and to the Washington University Division of Gastroenterology for Core Facilities (P30 DK52574).

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman, M., T. Azuma, D. E. Berg, Y. Ito, G. Morelli, Z. J. Pan, S. Suerbaum, S. A. Thompson, A. van der Ende, and L. J. van Doorn. 1999. Recombination and clonal groupings with Helicobacter pylori from different geographical regions. Mol. Microbiol. 32:459-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akada, J. K., K. Ogura, D. Dailidiene, G. Dailide, J. M. Cheverud, and D. E. Berg. 2003. Helicobacter pylori tissue tropism: mouse colonizing strains can target different gastric niches. Microbiology 149:1901-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akopyants, N. S., A. Fradkov, L. Diatchenko, J. E. Hill, P. D. Siebert, S. A. Lukyanov, E. D. Sverdlov, and D. E. Berg. 1998. PCR-based subtractive hybridization and differences in gene content among strains of Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13108-13113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akopyanz, N., N. O. Bukanov, T. U. Westblom, S. Kresovich, and D. E. Berg. 1992. DNA diversity among clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori detected by PCR-based RAPD fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:5137-5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alm, R. A., L. S. Ling, D. T. Moir, B. L. King, E. D. Brown, P. C. Doig, D. R. Smith, B. Noonan, B. C. Guild, B. L. deJonge, G. Carmel, P. J. Tummino, A. Caruso, M. Uria-Nickelsen, D. M. Mills, C. Ives, R. Gibson, D. Merberg, S. D. Mills, Q. Jiang, D. E. Taylor, G. F. Vovis, and T. J. Trust. 1999. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 397:176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaser, M. J. 1999. Hypothesis. The changing relationships of Helicobacter pylori and humans: implications for health and disease. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1523-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaser, M. J., and D. E. Berg. 2001. Helicobacter pylori genetic diversity and risk of human disease. J. Clin. Investig. 107:767-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cattoli, G., A. Bart, P. S. Klaver, R. J. Robijn, H. J. Beumer, R. van Vugt, R. G. Pot, I. van der Gaag, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, E. J. Kuipers, and J. G. Kusters. 2000. Helicobacter acinonychis eradication leading to the resolution of gastric lesions in tigers. Vet. Rec. 147:164-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dailidiene, D., M. T. Bertoli, J. Miciuleviene, A. K. Mukhopadhyay, G. Dailide, M. A. Pascasio, L. Kupcinskas, and D. E. Berg. 2002. Emergence of tetracycline resistance in Helicobacter pylori: multiple mutational changes in 16S rDNA and other genetic loci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3940-3946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond, J. 2002. Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature 418:700-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois, A., D. E. Berg, E. T. Incecik, N. Fiala, L. M. Heman-Ackah, J. Del Valle, M. Yang, H. P. Wirth, G. I. Perez-Perez, and M. J. Blaser. 1999. Host specificity of Helicobacter pylori strains and host responses in experimentally challenged nonhuman primates. Gastroenterology 116:90-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton, K. A., F. E. Dewhirst, M. J. Radin, J. G. Fox, B. J. Paster, S. Krakowka, and D. R. Morgan. 1993. Helicobacter acinonyx sp. nov., isolated from cheetahs with gastritis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:99-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaton, K. A., M. J. Radin, and S. Krakowka. 1993. Animal models of bacterial gastritis: the role of host, bacterial species, and duration of infection on severity of gastritis. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 280:28-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans, D. G., H. C. Lampert, H. Nakano, K. A. Eaton, A. P. Burnens, M. A. Bronsdon, and D. J. Evans, Jr. 1995. Genetic evidence for host specificity in the adhesin-encoding genes hxaA of Helicobacter acinonyx, hnaA of H. nemestrinae and hpaA of H. pylori. Gene 163:97-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ermak, T. H., P. J. Giannasca, R. Nichols, G. A. Myers, J. Nedrud, R. Weltzin, C. K. Lee, H. Kleanthous, and T. P. Monath. 1998. Immunization of mice with urease vaccine affords protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in the absence of antibodies and is mediated by MHC class II-restricted responses. J. Exp. Med. 188:2277-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falush, D., C. Kraft, N. S. Taylor, P. Correa, J. G. Fox, M. Achtman, and S. Suerbaum. 2001. Recombination and mutation during long-term gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori: estimates of clock rates, recombination size, and minimal age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:15056-15061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falush, D., T. Wirth, B. Linz, J. K. Pritchard, M. Stephens, M. Kidd, M. J. Blaser, D. Y. Graham, S. Vacher, G. I. Perez-Perez, Y. Yamaoka, F. Megraud, K. Otto, U. Reichard, E. Katzowitsch, X. Wang, M. Achtman, and S. Suerbaum. 2003. Traces of human migrations in Helicobacter pylori populations. Science 299:1582-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrero, R. L. and J. G. Fox. 2001. In vivo modeling of Helicobacter-associated gastrointestinal diseases, p. 565-582. In H. L. T. Mobley, G. L. Mendz, and S. L. Hazell (ed.), Helicobacter pylori: physiology and genetics. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 19.Ferrero, R. L., and P. J. Jenks. 2001. In vivo adaptation to the host, p. 583-592. In H. L. T. Mobley, G. L. Mendz, and S. L. Hazell (ed.), Helicobacter pylori: physiology and genetics. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 20.Fox, J. G., P. Beck, C. A. Dangler, M. T. Whary, T. C. Wang, H. N. Shi, and C. Nagler-Anderson. 2000. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces Helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat. Med. 6:536-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guruge, J. L., P. G. Falk, R. G. Lorenz, M. Dans, H. P. Wirth, M. J. Blaser, D. E. Berg, and J. I. Gordon. 1998. Epithelial attachment alters the outcome of Helicobacter pylori infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3925-3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han, S. R., H. C. Zschausch, H. G. Meyer, T. Schneider, M. Loos, S. Bhakdi, and M. J. Maeurer. 2000. Helicobacter pylori: clonal population structure and restricted transmission within families revealed by molecular typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3646-3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hildebrand, P., P. Bardhan, L. Rossi, S. Parvin, A. Rahman, M. S. Arefin, M. Hasan, M. M. Ahmad, K. Glatz-Krieger, L. Terracciano, P. Bauerfeind, C. Beglinger, N. Gyr, and A. K. Khan. 2001. Recrudescence and reinfection with Helicobacter pylori after eradication therapy in Bangladeshi adults. Gastroenterology 121:792-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman, P. S., N. Vats, D. Hutchison, J. Butler, K. Chisholm, G. Sisson, A. Raudonikiene, J. S. Marshall, and S. J. O. Veldhuyzen van Zanten. 2003. Development of an interleukin-12-deficient mouse model that is permissive for colonization by a motile KE26695 strain of Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 71:2534-2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ilver, D., A. Arnqvist, J. Ogren, I.-M. Frick, D. Kersulyte, E. T. Incecik, D. E. Berg, A. Covacci, L. Engstrand, and T. Boren. 1998. The Helicobacter pylori Lewis b blood group antigen binding adhesin revealed by retagging. Science 279:373-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong, J. Y., A. K. Mukhopadhyay, J. K. Akada, D. Dailidiene, P. S. Hoffman, and D. E. Berg. 2001. Roles of FrxA and RdxA nitroreductases of Helicobacter pylori in susceptibility and resistance to metronidazole. J. Bacteriol. 183:5155-5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Josenhans, C., K. A. Eaton, T. Thevenot, and S. Suerbaum. 2000. Switching of flagellar motility in Helicobacter pylori by reversible length variation of a short homopolymeric sequence repeat in fliP, a gene encoding a basal body protein. Infect. Immun. 68:4598-4603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kersulyte, D., H. Chalkauskas, and D. E. Berg. 1999. Emergence of recombinant strains of Helicobacter pylori during human infection. Mol. Microbiol. 31:31-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kersulyte, D., A. K. Mukhopadhyay, B. Velapatiño, W. W. Su, Z. J. Pan, C. Garcia, V. Hernandez, Y. Valdez, R. S. Mistry, R. H. Gilman, Y. Yuan, H. Gao, T. Alarcon, M. Lopez Brea, G. B. Nair, A. Chowdhury, S. Datta, M. Shirai, T. Nakazawa, R. Ally, I. Segal, B. C. Y. Wong, S. K. Lam, F. Olfat, T. Boren, L. Engstrand, O. Torres, R. Schneider, J. E. Thomas, S. Czinn, and D. E. Berg. 2000. Differences in genotypes of Helicobacter pylori from different human populations. J. Bacteriol. 182:3210-3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, A., J. O'Rourke, M. C. De Ungria, B. Robertson, G. Daskalopoulos, and M. F. Dixon. 1997. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology 112:1386-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackay, T. F. 2001. The genetic architecture of quantitative traits. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:303-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahdavi, J., B. Sonden, M. Hurtig, F. O. Olfat, L. Forsberg, N. Roche, J. Angstrom, T. Larsson, S. Teneberg, K. A. Karlsson, S. Altraja, T. Wadstrom, D. Kersulyte, D. E. Berg, A. Dubois, C. Petersson, K. E. Magnusson, T. Norberg, F. Lindh, B. B. Lundskog, A. Arnqvist, L. Hammarstrom, and T. Boren. 2002. Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science 297:573-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukhopadhyay, A. K., J.-Y. Jeong, D. Dailidiene, P. S. Hoffman, and D. E. Berg. 2003. The fdxA ferredoxin gene can down-regulate frxA nitroreductase gene expression and is essential in many strains of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 185:2927-2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munson, L., J. W. Nesbit, D. G. Meltzer, L. P. Colly, L. Bolton, and N. P. Kriek. 1999. Diseases of captive cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus jubatus) in South Africa: a 20-year retrospective survey. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 30:342-347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolan, K. J., D. J. McGee, H. M. Mitchell, T. Kolesnikow, J. M. Harro, J. O'Rourke, J. E. Wilson, S. J. Danon, N. D. Moss, H. L. Mobley, and A. Lee. 2002. In vivo behavior of a Helicobacter pylori SS1 nixA mutant with reduced urease activity. Infect. Immun. 70:685-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson, M. V., and A. Varki. 2003. Sequencing the chimpanzee genome: insights into human evolution and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4:20-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owen, R. J., and J. Xerry. 2003. Tracing clonality of Helicobacter pylori infecting family members from analysis of DNA sequences of three housekeeping genes (ureI, atpA and ahpC), deduced amino acid sequences, and pathogenicity-associated markers (cagA and vacA). J. Med. Microbiol. 52:515-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perkins, S. E., J. G. Fox, R. P. Marini, Z. Shen, C. A. Dangler, and Z. Ge. 1998. Experimental infection in cats with a cagA+ human isolate of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 3:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pot, R. G., J. G. Kusters, L. C. Smeets, W. Van Tongeren, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and A. Bart. 2001. Interspecies transfer of antibiotic resistance between Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter acinonychis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2975-2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salama, N. R., G. Otto, L. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2001. Vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori plays a role during colonization in a mouse model of infection. Infect. Immun. 69:730-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salama, N., K. Guillemin, T. K. McDaniel, G. Sherlock, L. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2000. A whole-genome microarray reveals genetic diversity among Helicobacter pylori strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14668-14673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soto, G., C. T. Bautista, R. H. Gilman, D. E. Roth, B. Velapatiño, M. Ogura, G. Dailide, M. Razuri, R. Meza, U. Katz, T. P. Monath, D. E. Berg, D. N. Taylor, et al. 2003. Helicobacter pylori reinfection is common in Peruvian adults following antibiotic eradication therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1263-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suerbaum, S., C. Kraft, F. E. Dewhirst, and J. G. Fox. 2002. Helicobacter nemestrinae ATCC 49396T is a strain of Helicobacter pylori (Marshall et al. 1985) Goodwin et al. 1989, and Helicobacter nemestrinae Bronsdon et al. 1991 is therefore a junior heterotypic synonym of Helicobacter pylori. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 52:437-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suerbaum, S., J. M. Smith, K. Bapumia, G. Morelli, N. H. Smith, E. Kunstmann, I. Dyrek, and M. Achtman. 1998. Free recombination within Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:12619-12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomb, J. F., O. White, A. R. Kerlavage, R. A. Clayton, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, K. A. Ketchum, H. P. Klenk, S. Gill, B. A. Dougherty, K. Nelson, J. Quackenbush, L. Zhou, E. F. Kirkness, S. Peterson, B. Loftus, D. Richardson, R. Dodson, H. G. Khalak, A. Glodek, K. McKenney, L. M. Fitzgerald, N. Lee, M. D. Adams, E. K. Hickey, D. E. Berg, J. D. Gocayne, T. R. Utterback, J. D. Peterson, J. M. Kelley, M. D. Cotton, J. M. Weidman, C. Fujii, C. Bowman, L. Watthey, E. Wallin, W. S. Hayes, M. Borodovsky, P. D. Karp, H. O. Smith, C. M. Fraser, and J. C. Venter. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388:539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Ende, A., Z. J. Pan, A. Bart, R. W. van der Hulst, M. Feller, S. D. Xiao, G. N. Tytgat, and J. Dankert. 1998. cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori populations in China and The Netherlands are distinct. Infect. Immun. 66:1822-1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Versalovic, J., M. S. Osato, K. Spakovsky, M. P. Dore, R. Reddy, G. G. Stone, D. Shortridge, R. K. Flamm, S. K. Tanaka, and D. Y. Graham. 1997. Point mutations in the 23S rRNA gene of Helicobacter pylori associated with different levels of clarithromycin resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:283-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, G., M. Z. Humayun, and D. E. Taylor. 1999. Mutation as an origin of genetic variability in Helicobacter pylori. Trends Microbiol. 7:488-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Welch, R. A., V. Burland, G. Plunkett III, P. Redford, P. Roesch, D. Rasko, E. L. Buckles, S. R. Liou, A. Boutin, J. Hackett, D. Stroud, G. F. Mayhew, D. J. Rose, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, N. T. Perna, H. L. Mobley, M. S. Donnenberg, and F. R. Blattner. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:17020-17024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamaoka, Y., M. S. Osato, A. R. Sepulveda, O. Gutierrez, N. Figura, J. G. Kim, T. Kodama, K. Kashima, and D. Y. Graham. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori: separation of H. pylori from East Asian and non-Asian countries. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:91-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]