Abstract

Context: Adverse events are estimated to affect up to 17% of hospitalized patients and to cause up to 98,000 patient deaths per year in the United States. Unexpected codes in hospitalized patients are one of the most significant adverse events, carrying a risk of death that is reported to range from 50% to 80%.

Objective: The Rapid Medical Response Team (RMRT) was an initiative designed to reduce adverse events, specifically failure to rescue, leading to nonintensive care unit (nonICU) codes. This initiative was funded, as part of the Transforming Care at the Bedside (TCAB) program, by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Design: To determine whether the RMRT had a significant impact on our nonICU code rate, we did a retrospective, noncohort comparison of 2004 (preRMRT) data with 2005 (postRMRT) data.

Main Outcome Measures: Our main outcome measures were nonICU codes, mortality rate, and unplanned patient transfers to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Results: There was a decrease in the nonICU code rate per 1000 discharges from 1.90 in 2004 to 1.01 in 2005. Implementation of the RMRT correlates to a statistically significant decrease in the nonICU code rate (p = .018; relative risk, 0.53 [95% confidence interval, 0.31–0.91]). The nonICU mortality rate remained unchanged at 2.01%. The unplanned ICU transfer rate for 2005 was 47%.

Conclusions: Implementation of RMRTs can decrease nonICU code rates and the rate of unplanned ICU transfers. RMRTs can empower staff, enhance expertise and communication skills, and support a culture of safety.

Clinical Vignette

Mr X, a 72-year-old man, was hospitalized with an infection of his dialysis graft. Within the preceding two days, Mr X had complained of abdominal pain. His abdomen remained soft and nontender. Today, during hemodialysis, Mr X complained of nausea and midepigastric pain. His blood pressure dropped to 70 mmHg systolic and his oxygen saturation fell to the mid-70s. The patient was diaphoretic, tachycardic, and pale.

Introduction

Safety is freedom from accidental injury.1 This definition from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Quality Committee is the foundation on which the health care community strives to provide quality patient care. Since the publication of the IOM's landmark books, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (1999)2 and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (2001),3 the health care community has focused increasingly on ensuring patient safety through the development of processes to avoid adverse events and improve the quality of care. This unwavering goal for Kaiser Permanente (KP) began in the early 1990s with the establishment of a relationship with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). KP's National Patient Safety Program, a product of this collaboration, which is a basic tenet for the provision of care in all Kaiser Foundation Health Plans and Hospitals, and independent Permanente Medical Groups, has embraced safety as its core component and includes strategic goals such as safe culture, safe support systems, and safe patients.

Delivering safe care on a daily basis is multifaceted and complex. It requires solid participation from leadership and all labor partners within the facility and a broad collaborative partnership with organizations such as the IHI. The commitment to quality within KP has been forged on the principle that all medical and nursing staff work routinely with KP leaders in program testing, implementation, and redesign. After the publication of the IOM books, the IHI launched major change initiatives intended to improve communication, prevent adverse events and avoidable deaths, and improve the overall quality of hospital care. Through initiatives such as Transforming Care at the Bedside (TCAB), which was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and launched in 2003, and the 100,000 Lives Campaign, which was launched in 2004, the IHI challenged the health care community to strengthen its commitment to make safety its highest priority. KP accepted that challenge and the Roseville Medical Center became one of three hospitals selected to receive the initial TCAB grants in 2003.

TCAB uses a rapid-cycle testing process with prescribed design targets. The targets focus specifically on patient safety and include no unanticipated deaths, no adverse events, and effective care teams within supportive environments. In the TCAB environment, staff can design short-term trials to mitigate identified issues and develop cohesive systems of care.

A fundamental goal for the Roseville Medical Center staff was to reduce adverse events. Adverse events are estimated to affect up to 17% of hospitalized patients and cause up to 98,000 patient deaths per year in the US.4,5 Research has shown that adverse events, defined as any harm that occurs to patients from medical care, whether or not as the result of error, are associated with higher rates of poor outcomes and death and that many adverse events are preceded by physiologic signs that are clearly abnormal.6–9 A review of the literature identifies three main systemic issues contributing to adverse events:

Failure to plan

Failure to communicate

Failure to recognize a patient's deteriorating condition (failure to rescue).

The Joint Commission, formerly known as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, states that two of three primary causes of sentinel adverse events are lack of communication among hospital staff and inadequate patient assessments.10

Through evaluation of incident and code reports, the Roseville Medical Center focused on identifying and developing methods to reduce the number of adverse events, specifically failure to rescue, leading to unexpected codes within our facility. Unexpected codes in hospitalized patients constitute one of the most significant adverse events; the death rate for unexpected codes has not changed since 1997. The risk of death from unexpected codes in hospitalized patients is reported to range from 50% to 80%.11

With the commitment and full support of our executive sponsors (Table 1), our TCAB committee opted to pilot a Rapid Medical Response Team (RMRT) in an effort to decrease the number of failure-to-rescue events. The RMRT, one of the IHI-recommended change initiatives, provides a systematic mechanism for medical-surgical staff to obtain immediate critical care expertise in evaluating patients and providing early interventions to minimize or prevent deterioration of patients' conditions. Unlike a code team, an RMRT has the objective of early intervention before the patient's condition deteriorates to the point that s/he requires resuscitation. RMRTs have been shown to reduce the incidence of cardiac arrests outside the intensive care unit (ICU) by 50%, reduce the rate of medical-surgical patient transfers to the ICU by 25% to 30%, and decrease hospital mortality by up to 26%.6 In addition to improving safety, quality, and care for patients, RMRTs benefit staff through the development of a service and educational partnership between hospital units and through enhanced communication and clinical skills. The ultimate result is a reduction in adverse events and improved clinical practice.

Table 1.

Roseville Medical Center Rapid Medical Response Team executive sponsors

Adverse events are estimated to affect up to 17% of hospitalized patients and cause up to 98,000 patient deaths per year in the US.4,5

Developing the Rapid Medical Response Team

The TCAB committee comprises licensed and unlicensed staff, who collaborated with representatives from our Labor-Management Partnership (labor partners), including respiratory therapy staff, executive leadership, and the representatives of the disciplines involved in our code process, to begin developing the initiative. Although RMRTs are a relatively new concept in the US, they have been successfully used in Australia since 1990.12 Since that time, several US health care organizations have developed initiatives. The TCAB committee reviewed the information on RMRTs implemented by other facilities and chose a design model based on one implemented at Baptist Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, that had been profiled by IHI. The target population was the nonICU (medical, surgical, and telemetry) hospitalized population, which, for Roseville Medical Center, is typically older (with a representative age of >70 years) with multiple comorbidities.

The initial RMRT discussions began in June 2004. A timeline was established for development that included the first trial targeted for September 4, 2004, and an evaluation of current resources, development of protocols, development of effectiveness metrics, and evaluation of staff educational needs. The TCAB committee outlined the concept, identified the activities essential to the initiative development, detailed how the components would work, and, later, supported implementation.

Integral to all Roseville Medical Center initiatives is the basic KP National Patient Safety Program quality strategic focus, which is to partner with our patients to maintain and improve their health through effective prevention, early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and follow-up. To ensure that this focus is the core of all initiatives, the overarching TCAB structure encompasses, as collaborative partners, our administrative leaders and Quality Assessment and Improvement Program staff, including leadership from all major committees such as the Patient Quality Committee, Risk Management Committee, the Professional Practice Committee, and the Code Blue Committee. Incident reports, unplanned ICU transfers, and code reports are evaluated by leaders in these committees to identify trends, performance improvement concepts, professional performance needs, and systems issues, as well as to formulate recommendations and to initiate change. Executive leadership reviews all recommendations from these groups.

Collaboration and continuing staff support from these major stakeholders, along with direct involvement and support of our administrative and executive leadership was fundamental to the development of this initiative and is essential to its ongoing success. The culture of the Roseville facility, as well as that of KP overall, begins with our leaders and their steadfast commitment to programs built on the foundation of safety and the use of outcomes as proactive opportunities for system improvements.

During the development process, the overarching objectives were defined as:

Maximizing the climate of safety for medical-surgical patients

Promoting a more cohesive clinical approach hospitalwide

Augmenting the expertise and communication skills of our nurses throughout the facility.

Because the focus population of RMRTs is nonICU patients, specifically medical-surgical and telemetry inpatients, we anticipated a cultural change. Through development of a more collaborative mind-set supporting enhanced nursing skills, we anticipated that staff would recognize changes early and minimize barriers that could compromise patients' safety. To evaluate the effectiveness of the initiative, the following specific outcome measures were proposed:

Decreased adverse events, including nonICU cardiopulmonary arrests (codes)

Decreased mortality

Decreased unplanned ICU transfers

Increased staff awareness of physiologic indicators of deterioration

Increased staff communication.

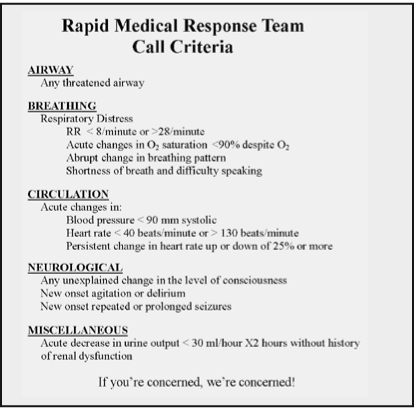

As the concept developed, the TCAB committee concluded that it was vital for the team to be accessible to anyone in the facility who felt a need for it, and the initiative was structured in such a way that anyone in the facility could initiate an RMRT call by contacting our facility operators. As call criteria were developed, they were made sufficiently broad to encourage calls for subjective concerns, such as the “intuition” nurses frequently describe or because they were worried about the patient, as well as more quantifiable physiologic changes that are premonitory signs of physical deterioration (Figure 1).6,7,13,14 The Roseville RMRT was designed to be composed of an ICU charge nurse, chosen for excellence in clinical nursing judgment, and a respiratory therapist (RT) for expertise essential for enhanced assessments and support of patients' pulmonary needs. Together, they provided the resources to establish an ICU level of care.

Figure 1.

Rapid Medical Response Team Call Criteria.

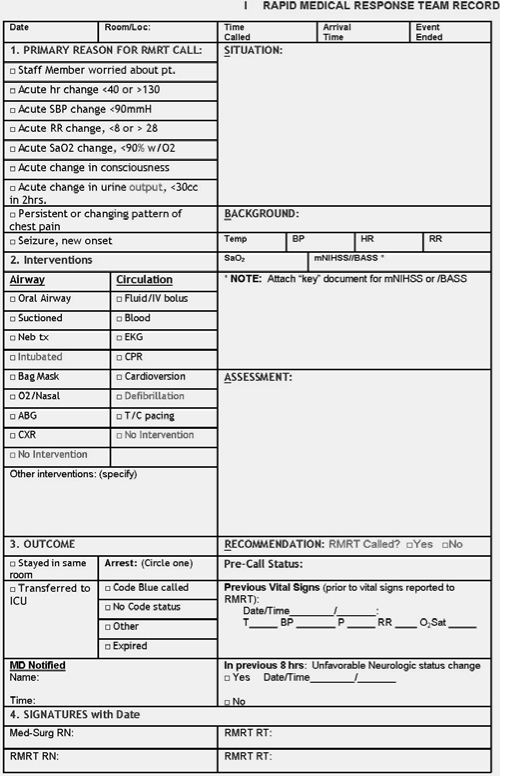

With a focus on promoting a safe culture, a critical prerequisite was to improve staff recognition of at-risk patients before their condition deteriorates to provide a safety net to prevent further deterioration. Consequently, a benchmark for the initiative would be the staff's ability to recognize the need to rescue. Therefore, education would be essential for success. The educational elements developed included components focused on eliminating barriers to contacting and using the RMRT. All staff, including physicians, nurses, and ancillary staff were included in the RMRT educational process. The education began initially with the RMRT introduction: the composition of the team, the objectives for the team, when and how to contact the team, how the data would be collected, and how staff and patients would receive feedback. All staff received copies of the call criteria, which were also prominently displayed in the two trial units, and the data collection tool (Figure 2). The key ongoing educational program components, implemented simultaneously with the introduction, consist of Human Factors and Critical Event Team Training (CETT) to enhance the skills of staff in detecting deterioration. Additionally, because our staff communicate and document using Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (SBAR), concurrent training in SBAR, underscoring the critical role of communication in quality patient care, is routinely provided. Current thinking postulates that “failure to communicate” leading to adverse events may be indicative of a nurse's hesitancy to call because of difficulty in communicating findings, because subtle changes may be difficult to articulate, or because of failure to appreciate the urgency of the situation, a lack of knowledge, or failure to seek advice. The commitment to ongoing staff education in communication and assessment skills remains crucial.

Figure 2.

Rapid Medical Response Team Record.

The data collection tool supports a direct measure of adverse events, specifically nonICU codes, mortality, and unplanned ICU transfers. The data collection process includes a debriefing mechanism that provides insight into staff awareness of the physiologic indicators of patient deterioration and of communication effectiveness and whether staff have embraced the collaborative cultural change approach that the RMRT provides. After an RMRT call, the completed data collection tool is reviewed by the department manager. All data are validated by chart reviews, staff interviews, and patient and family meetings. The manager then enters the data into a database, where it can be analyzed for trending and tracking as well as shared with other facilities and organizations. If an RMRT call results in calling a code, both RMRT data and code data are collected. The code data are reviewed and validated for process by management and forwarded to our Quality Department, where it is validated for meeting code criteria. It is then entered into the National Registry of CardioPulmonary Resuscitation (using software version 5.0/5.01; Digital Innovation, Inc, Forest Hill, Maryland), to be shared with the national registry as part of an international database of inhospital resuscitation events.

The RMRT data, after review and completion by the department manager, are entered into spreadsheets and charts compiled in Microsoft Office Excel 2003 (version 11; Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Reports are shared monthly with the TCAB and Patient Quality Committees for analysis and trending.

The RMRT process begins when a call is placed to the facility operators, requesting the RMRT. Once contacted, the operators use text-messaging and overhead paging to send the RMRT to the unit and room number. The overhead page allows workers in other disciplines, including physicians, nursing supervisors, and department managers, to participate in the call. The patient's primary nurse remains with the patient throughout the call. The ICU nurse, designated the team leader, completes an initial physiologic assessment with the primary nurse, while the respiratory therapist assesses respiratory needs, provides respiratory support, and makes respiratory recommendations. The ICU nurse collaborates with the physician on the assessment findings and subsequent recommendations. Either the primary nurse, a nursing supervisor, or the department manager records all events on the RMRT data collection tool. Another nurse from the unit remains available to the team throughout the call. When the outcome includes transfer to a unit with a higher level of care, the RMRT accompanies the patient. The department manager who chairs our TCAB committee is notified each time the RMRT is called. This manager is responsible for collecting the data tools from each event, validating all information entered on the tool, and, within 24 hours of the call, reviewing the patient chart for antecedent events. The department manager or designee also meets with the primary nurse who was caring for the patient at the time of the call to discuss the circumstances leading to the call, then contacts the patient or the patient's family members to assess outcomes, augment our personal approach to care, and further define the root cause of the call. If system problems are identified, executive leadership, quality, and other affected departments are alerted as an initial step in generating system analyses and changes.

Executive leadership has been involved with the initiative since inception and has supported staff through the change process with regular feedback about the activities and outcomes, planned educational opportunities, and successes. Executives, along with the quality program committees, use the information received from the individual call data to evaluate and modify existing processes to enhance clinical and operational results for quality of care and patient safety.

Beginning September 4, 2004, the initiative was piloted on two medical-surgical units on the evening shift. Results were evaluated at the one- and two-month marks, with changes in process made on the basis of outcomes, and the initiative was expanded to the night shift on the two units in November. Training continued for all staff. On January 1, 2005, the initiative was expanded hospital-wide and outcome data collection began in earnest.

Data Analysis

Code data from 2004 (preRMRT) were compared with 2005 (postRMRT) data, code and RMRT calls, to determine whether the RMRT had a significant impact on our nonICU code rate. This data excluded all “do not resuscitate” patient data and data from codes occurring in the Emergency Department or in other nonmedical-surgical areas. Prior to analysis, the data from both years were reviewed and validated by the department manager and the clinical nurse specialist to ensure accuracy. Incomplete information was eliminated from analysis; accordingly, the analysis is unadjusted for age, sex, or comorbidity.

To determine whether the RMRT had a significant impact on our nonICU code rate, data from January 1 through December 31, 2004, were compared with data from January 1 through December 31, 2005, using χ-square analysis. Statistical Analysis Software (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used to perform the analysis. The first full year of hospitalwide RMRT implementation was 2005. Four nonICU codes, which had occurred during the staff training period in 2004, were included with the 2004 data.

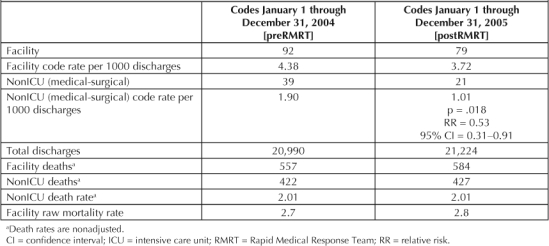

Data analysis reflected a decrease in nonICU code rate per 1000 discharges, from 1.90 in 2004 to 1.01 in 2005, dropping from 39 codes to 21 (46% decrease). The implementation of the RMRT correlates to a statistically significant decrease in the nonICU code rate (p = .018; relative risk, 0.53 [95% confidence interval, 0.31–0.91]; Table 2). Additionally, our facilitywide code rate decreased from 4.38/1000 discharges in 2004 to 3.72/1000 discharges in 2005. Considering that the average age of the Roseville Medical Center patient has historically been older than in other institutions and that older patients are more likely than other patients to have comorbidities, an adjusted analysis might have resulted in even greater statistical significance.

Table 2.

NonICU codes and deaths in 2004 and 2005

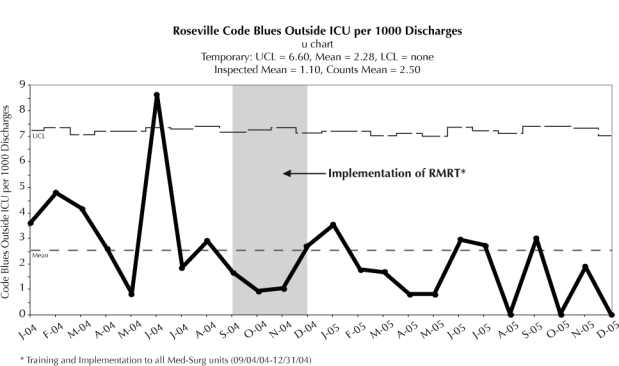

A second analysis method, Control Chart methodology, also indicates that a trend is beginning to emerge from the data to suggest more than a common cause. With this methodology, further data points will be necessary to confirm that the RMRT is the “special cause” (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Control Chart methodology for codes outside the intensive care unit (ICU).

A second method for determining the effect of the Rapid Medical Response Team (RMRT) is to use Control Chart methodology. This method, endorsed by the Institute of Healthcare Improvement, examines code blue calls outside of the ICU on a monthly basis to determine if variations have “common cause” or if instead they could be explained by the general characteristics of this measure, or “special cause.” Special cause is defined as some phenomenon that cannot be explained by chance alone but is caused by a change in some factor within the system. In this case, the special cause would be the implementation of the RMRT. LCL = lower control limit; Med-Surg = medical-surgical; UCL = upper control limit

… over the course of the year, the staff activated the RMRT sufficiently early to avoid transfers in 53% of the patients.

The overall unadjusted mortality rate in our facility rose slightly from 2.7% per 1000 discharges in 2004 to 2.8% in 2005; however, the nonICU mortality rate remained unchanged at 2.01%. During the same time frame, our total discharges from the facility increased from 20,990 (2004) to 21,224 (2005). Our unplanned ICU transfer rate for 2005 was 47%. Seventy-two transfers occurred as a result of 152 RMRT calls. This suggests that, over the course of the year, the staff activated the RMRT sufficiently early to avoid transfers in 53% of the patients. Over time, training will be modified on the basis of the type of physiologic changes most likely to require transfer.

Although other changes had been implemented in 2004 that were making a positive impact on our nonICU code rate, the effect of the RMRT implementation is readily apparent. As has been the case in other studies, there was an inverse relationship between the number of calls and the number of codes, with the exception of the first quarter of 2005, when there were 44 calls and eight codes (18%). Nurses' hesitancy to call may be one explanation. Theoretically, because the initiative was so new, staff might have been hesitant to place the call because of lack of familiarity with the team or they may not have identified the physiologic deterioration early enough. A 2006 study15 looking at nursing use of medical emergency team (MET) systems indicates that MET activation occurred in <40% of cases when the patients' conditions fulfilled calling criteria and that nurses who had 11 years' experience or more were more likely to activate the MET than were those with less experience. The authors of the study propose continual education and briefing sessions to encourage team use. For the Roseville Medical Center, ongoing education continued to improve our results, with 54 calls in the fourth quarter of 2005 and only two nonICU codes (4%).

Results

The implementation of the RMRT has signaled a complete cultural change for Roseville Medical Center. Prior to RMRT, contacting the physician was the only option available to nurses when they identified an adverse physiologic change in a patient. RMRT provides a second option that is immediately available and for which the only criterion is a “feeling of concern.” Anticipating a barrier to placing the call, we ensured that much of our preparatory and continuing education has focused on the perceived benefits of the initiative—for patients, nurses, and physicians. Consequently, nurses feel empowered to request assistance. RMRT provides that assistance immediately, shares critical care expertise and knowledge, and is supportive and nonjudgmental while sensitively fostering new working relationships. The trust that has developed between the RMRT and the medical-surgical staff endorses their mentoring relationship. The physicians have found that the interventions of the RMRT have frequently averted potential crises and augmented their ability to intervene by receiving, through the refined use of SBAR and enhanced critical-thinking skills, more succinct, comprehensive patient information. Since all staff have been encouraged to educate patients and their families about the availability of the RMRT, making our patients partners in ensuring safety, two family-initiated RMRT calls have been responded to, and the RMRT quickly resolved all concerns.

Evaluations of RMRT calls and outcomes have precipitated changes in the educational programs presented. CETT is routinely provided to support staff in augmenting their expertise in identifying patients with physiologic indicators of deterioration. The monthly trainings have been expanded to provide six-hour programs encompassing SBAR, Human Factors, and CETT for Roseville Medical Center staff as well as other KP facilities in a collaborative effort to support the expansion of RMRTs. Recently, a virtual patient simulator has been incorporated to further enhance teamwork, assessment skills, and patient care. This type of training has been shown to improve team performance, assessments, and patient outcomes.16 The ongoing education emphasizes specific patient-centered events, with identification of early deterioration being paramount. The global approach has centered on developing and supporting a collaborative mind-set.

Regular review of antecedent events has led to proactive systems changes. For example, instances in which patients were allowed to remove their oxygen sources during ambulation were identified. This occasionally led to hypoxic responses, patient distress, and, sometimes, RMRT calls. Once this problem was identified, a multidisciplinary Oxygen Task Force was created to evaluate and update our current standards; to implement team-centered, educationally based competencies focusing on respiratory issues; and, to provide a “reliable standard of excellent care.”17

The direct participation and collaboration of all staff and our labor partners during initiative development and implementation has strengthened the commitment felt toward the RMRT. A clear sense of mission and shared vision of enhancing patient safety and improving patient outcomes has stimulated the enthusiasm that staff have consistently displayed. As the team was called more frequently, the staff began to recognize the secondary gains of expert collaboration and support from the team. They also received acknowledgment and support for their own skills through event analyses and feedback. The advantages of better communication skills, with more concise information sharing and more expedient results, became apparent as well. Collectively, these have resulted in improved clinical proficiency and accentuated patient safety. Theoretically, these benefits, in addition to the decrease in nonICU codes, are a direct reflection of a broad, successful culture change.

As the team was called more frequently, the staff began to recognize the secondary gains of expert collaboration and support from the team.

With solid support from executive leadership throughout the implementation of the RMRT, the KP Patient Safety Program vision has been shared in ways that empower both our staff and our patients. A strong partnership has been built on mutual goals, resulting in both short-term and long-term quality gains emphasizing patient-centeredness. Continuous feedback, ongoing education, and information sharing have sustained the initial culture change and continue to ensure improvement. Additionally, patients at the Roseville Medical Center have demonstrated their satisfaction with the RMRT and the comprehensive cultural change by moving us from the top one-third in patient satisfaction surveys to the number-one ranking of KP facilities in Northern California for seven of eight months.

Presentations on our initiative have been given to the TCAB Learning & Innovation Community Meeting in Tampa, Florida (March 2005), and the Joint Commission Conference on Critical Linkages: Nurse Staffing, Patient Safety and Transforming Care at the Bedside, in Seattle, Washington (May 2006). In 2005, a regional committee, California Region RRT (Rapid Response Team) Collaborative, was formed to coordinate and evaluate all aspects of the teams and to support the development of RMRT teams, discuss emerging trends, and share ideas with other facilities (See Sidebar: “Northern California Regional Spread of Rapid Response Teams”). This committee has developed a standardized data collection tool that all KP Northern California facilities will use. The new tool will promote the collection of consistent, comparative data from all facilities. Our department manager has chaired this collaborative, which includes representatives from Sunnyside (Oregon), Hawaii, West Los Angeles, and Fontana (Los Angeles area), in addition to many non-KP facilities, such as Cedars-Sinai (Los Angeles), Queens in Honolulu, and the Department of Health Services Los Angeles County Hospitals.

Northern California Regional Spread of Rapid Response Teams.

In August 2005, the Roseville Medical Center reported the success of its project to many leadership groups in the Northern California Region of Kaiser Permanente (KP). Regional leadership decided to implement rapid response teams (RRTs) across the region in all 18 medical centers. Because issues were identified about encouraging nurses to call the RRT, a “change package” was developed regionally that included several elements:

Conducting Human Factors training for all staff and physicians in the medical-surgical units

Forming a multidisciplinary team to meet regularly and review RRT calls and code blue calls

Reporting monthly, in a standardized fashion, the number of RRT calls and codes outside of the intensive care unit to the Regional Risk Management Department

Participating in monthly collaborative meetings to compare and contrast models and issues across the region.

In the August 2005 Design and Build workshop, leaders from the Roseville Medical Center played an important role as faculty. During the workshop, the following agreements were made:

RRT calling criteria would be standardized

Definitions of terms and reporting forms would be standardized

There would be local control of RRT composition.

To present the change package, a launch workshop took place in September 2005, and leads from all medical centers were invited.

By the end of the first quarter of 2006, all 18 medical centers had at least pilot RRTs in one medical-surgical unit. As of August 2006, RRTs had been implemented in all KP medical-surgical units in Northern California, and all have been reporting their data monthly. The medical centers have also been participating in a monthly collaborative meeting. To date, significant trends have not yet been seen in decreases of rates of code blue calls or mortality; however, the benefits of improving competence and creating an environment conducive to calling for assistance early have been tremendous for nurses.

The measures will continue to be reviewed regularly with the expectation of demonstrating the benefits of RRTs.

Information from Northern California Regional Risk Management.

In an effort to further partner with other health care organizations, the initiative has been presented to the Sacramento–Sierra–Stanislaus–San Joaquin Area Patient Safety Collaborative. Additionally, the Roseville Medical Center RMRT has been the subject of articles published in the TPMG Forum (July–August 2005) and Advance for Nurses (July 2006).

With the success of the Roseville Medical Center RMRT, all of the Northern California and several of the KP Southern California Medical Centers have embarked on initiatives to implement RMRTs.

… these savings are likely far superseded by avoidance of the nonquantifiable psychological and physical toll that adverse events exact on patients and their families.

No additional costs have been incurred with the implementation of the RMRT. Conversely, significant cost savings may have been generated through hospital days saved. However, these savings are likely far superseded by avoidance of the nonquantifiable psychological and physical toll that adverse events exact on patients and their families.

Conclusion

The achievements of the RMRT at the Roseville Medical Center are clearly evident, with a decreased code rate and a decreased relative risk of nonICU codes being called for nonICU patients. As Donald Berwick, MD, MPP, FRCP, President and CEO, IHI, so succinctly stated during the launching of the 100,000 Lives Campaign, “Some is not a number, soon is not a time.”a With the incorporation of RMRTs throughout all KP Northern California facilities all medical-surgical patients can feel safer in their facilities and all the facilities can achieve a higher quality of patient care and better patient outcomes. The focus on patient safety has provided an opportunity to develop an initiative of excellence that dovetails with the mantra of KP's Patient Safety Program: “Patient safety is every patient's right and everyone's responsibility.”18

In the case vignette presented earlier, when Mr X showed symptoms of deterioration, the RMRT was called. An assessment led to immediate transfer to the ICU where he was stabilized, evaluated further and, within a very short time, successfully operated on for a perforated duodenal ulcer. Our team had averted a potential code and provided immediate ICU-level of expertise in care. Mrs X summarized the sentiments of many of the Roseville Medical Center's patients when she told the department manager, “Your team saved my husband's life.”

Acknowledgments

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

Disclosure

Parts of this article have been submitted to the Joint Commission as an initiative summary supporting the use of process and outcome measures to improve organization performance and quality and safety of care.

Footnotes

a Donald P Berwick, MD, MPP, Keynote Presentation 16th Annual National Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care 2004; Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

References

- Brennan TA, Gawande A, Thomas E, Studdert D. Accidental deaths, saved lives, and improved quality. N Engl J Med. 2005 Sep 29;353(13):1405–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb051157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin SE. Implementing a rapid response team. Am J Nurs. 2006 Oct;106(10):50–3. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200610000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002 Feb 16;324(7334):387–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7334.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds TC. Best-practice protocols: implementing a rapid response system of care. Nurs Manage. 2005 Jul;36(7):41–2. 58–9. doi: 10.1097/00006247-200507000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, et al. MERIT study investigators. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005 Jun 18–24;365(9477):2091–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66733-5. Erratum in: Lancet 2005 Oct 1;366(9492):1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur-Rouse F. Critical care outreach services and early warning scoring systems: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2001 Dec;36(5):696–704. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine J. The role of nurses in preventing adverse events related to respiratory dysfunction: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005 Mar;49(6):624–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root causes of sentinel events (all categories) [chart on the Internet] The Joint Commission; Washington (DC): Sentinel event statistics 2006 Dec 31 [cited 2007 Mar 13] Available from: www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/Statistics/ click on: Root Causes of Sentinel Events (all categories) [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A. Frequency and pattern of medical emergency team activation among medical cardiology patient care units. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2007 Jan–Mar;30(1):81–4. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200701000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi J. Nurses' experiences of making decisions to call emergency assistance to their patients. J Adv Nurs. 2000 Jul;32(1):108–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhill DR, McNarry AF, Mandersloot G, McGinley A. A physiologically-based early warning score for ward patients: the association between score and outcome. Anesthesia. 2005 Jun;60(6):547–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. Prospective controlled trial of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Care Med. 2004 Apr;32(4):916–21. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000119428.02968.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamonson Y, Heere BV, Everett B, Davidson P. Voices from the floor: nurses' perceptions of the medical emergency team. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2006 Jun;22(3):138–43. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita MA, Schaefer J, Lutz J, Wang H, Dongilli T. Improving medical emergency team (MET) performance using a novel curriculum and a computerized human patient simulator. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005 Oct;14(5):326–31. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amalberti R, Auroy Y, Berwick D, Barach P. Five system barriers to achieving ultrasafe health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005 May 3;142(9):756–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakland (CA): Kaiser Permanente Patient Safety; kpnet.kp.org:81/california/qmrs/ps/ [homepage on the Intranet (password protected)] [cited 2007 Mar 20]. Available from: http://kpnet.kp.org:81/california/qmrs/ps/ [Google Scholar]