Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) negatively regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, primarily by base-pairing with the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of their target mRNAs. Many miRNAs are expressed in a tissue/organ-specific manner and are associated with an increasing number of cell proliferation, differentiation and tissue development events. Cardiac muscle expresses distinct genes encoding structural proteins and a subset of signal molecules that control tissue specification and differentiation. The transcriptional regulation of cardiomyocyte development has been well established, yet only until recently has it been uncovered that miRNAs participate in the regulatory networks. A subset of miRNAs are either specifically or highly expressed in cardiac muscle, providing an opportunity to understand how gene expression is controlled by miRNAs at the post-transcriptional level in this muscle type. miR-1, miR-133, miR-206 and miR-208 have been found to be muscle-specific, and thus have been called myomiRs. The discovery of myomiRs as a previously unrecognized component in the regulation of gene expression adds an entirely new layer of complexity to our understanding of cardiac muscle development. Investigating myomiRs will not only reveal novel molecular mechanisms of the miRNA-mediated regulatory network in cardiomyocyte development, but also raise new opportunities for therapeutic intervention for cardiovascular disease.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs, miRs) are a class of endogenous noncoding small RNAs, which are ~22 nt long and modulate gene expression by targeting mRNAs for post-transcriptional repression. In animals, miRNA-dependent repression is achieved through imperfect base-pairing between the miRNA and its target mRNA, resulting in target mRNA degradation and/or translational repression. Recent studies indicate that miRNAs participate in many essential biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. miRNAs are also associated with important diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease. More than 900 miRNAs have been identified in humans. Among them, a subset of miRNAs are muscle tissue-specific, and have been called myomiRs. Those include miR-1, miR-133, miR-206 and miR-208.

Cardiac myocytes derive from embryonic mesoderm during development. The regulation of muscle gene expression by well-known transcriptional networks involving serum response factor (SRF), myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) and other transcription factors is complex. SRF, MEF2 and other cardiac transcription factors activate the expression of cardiac genes encoding many contractile proteins. Recently, it was found that SRF and MEF2 regulate the expression of two clusters of muscle-specific miRNA genes: miR-1-1/miR133a-2 and miR1-2/miR133a-1. On the other hand, miR-208, another myomiR specifically expressed in cardiomyocytes, is involved in the regulation of the myosin heavy chain (MHC) isoform switch during development and in pathophysiological conditions. miR-206 is another myomiR specifically expressed in skeletal muscle and shown to play a key role in neuromuscular interaction. Emerging evidence demonstrates that a complex network of myomiRs-post-transcriptional regulated gene expression coordinates overall cardiomyocyte development and function. Here, we review recent developments on miRNAs and cardiomyocyte development, emphasizing the direction of future research in this field.

miRNAs, tiny molecules with huge functional potential

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) represent a large class of functional transcripts in higher organisms and perform a variety of roles. One family of small ncRNAs – called miRNAs due to their short length (~22 nucleotides) – is an especially abundant and fundamental class of regulators of gene expression. The very first miRNA genes lin-4 and let-7 were identified more than a decade ago. Since then, additional genetic studies have been performed in C. elegans and Drosophila melanogaster to support the view that miRNAs have a crucial role in animal development [1; 2; 3]. To date, more than 3,000 miRNAs have been identified in animals, plants and viruses, including 940 mature miRNAs identified in the human genome (miRBase database, http://www.mirbase.org/). Many of these miRNAs are highly conserved across a number of species [4; 5].

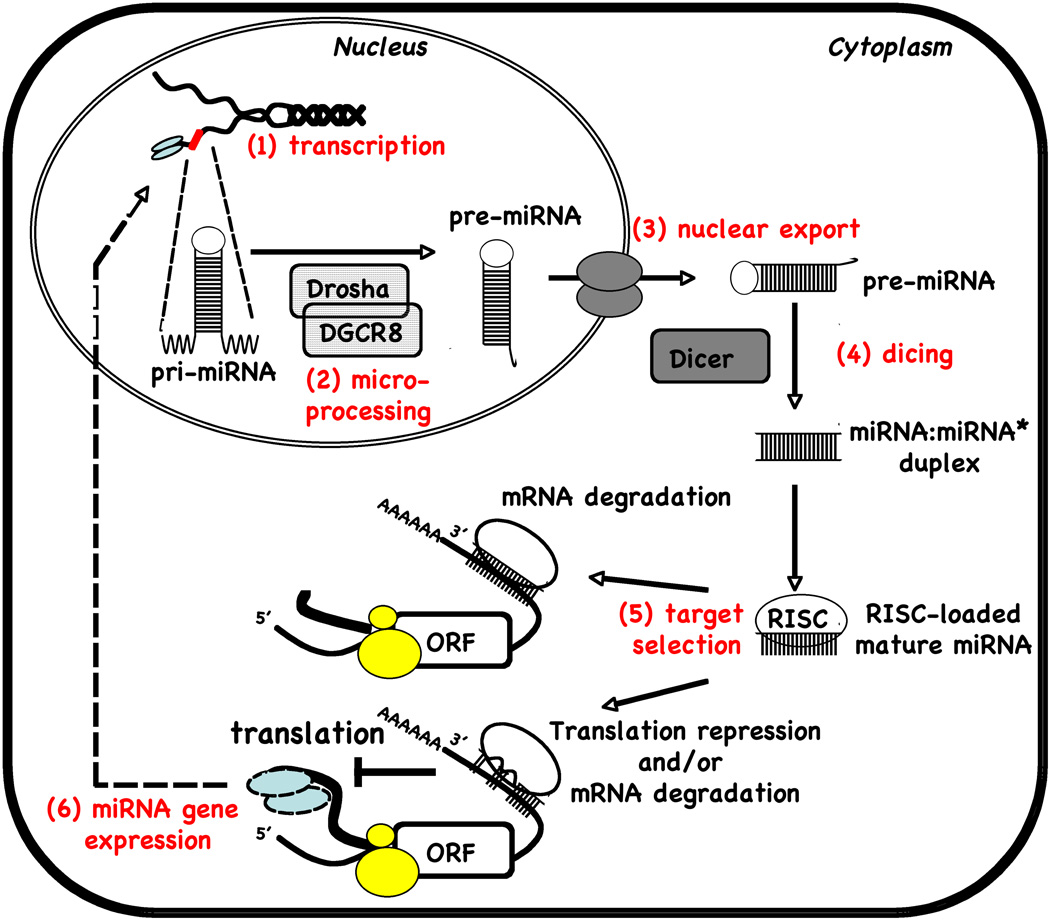

Approximately 50% of known miRNAs are clustered in the genome and transcribed as polycistronic primary transcripts, while the rest are expressed as individual transcripts from intergenic or intronic locations [6; 7]. These RNA molecules are initially transcribed by RNA polymerase II as long transcripts known as primary-miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) [8; 9] (Fig.1). Pri-miRNAs are processed in the nucleus by the RNase III enzyme, Drosha and the dsDNA binding protein DGCR8/Pasha, yielding ~70-nt stem-loop structures called precursor miRNA (pre-miRNAs) [10]. These pre-miRNAs are then transported into the cytoplasm by the nuclear export factor exportin 5, where they serve as substrates of Dicer, another RNase III enzyme, to generate ~22-nt mature miRNA duplexes [11]. Finally, the mature miRNA duplexes dissociate and one strand is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The miRNA-loaded RISC is capable of binding to the 3’-UTR of target mRNAs and inhibits their translation or leads to their degradation.

Figure 1.

miRNA biogenesis and function.

Target specificity of a given miRNA is largely governed by its highly conserved seed sequence (nucleotides 2 to 8) of the miRNA [12]. Individual mRNAs can be targeted by several miRNAs, and a single miRNA can regulate multiple target mRNAs; therefore, miRNA-mediated inhibition brings enormous complexity to the regulation of gene expression [13]. Identifying the targets of specific miRNAs is a prerequisite as well as a challenge for understanding the precise molecular mechanisms underlying their function. Most animal miRNAs are partially complementary to their target sites, which impedes simple homology searches to identify target sequences. In response, several bioinformatics-prediction algorithms were developed and are proving to be an indispensable guide for advancing miRNA research [14]. However, further experimental testing is required to validate miRNA targets. With an excess of predicted mRNA targets, it is believed that these small RNAs have enormous regulatory potential in a variety of biological processes, from cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis to cancer.

Cardiac and skeletal-muscle specific miRNAs, myomiRs

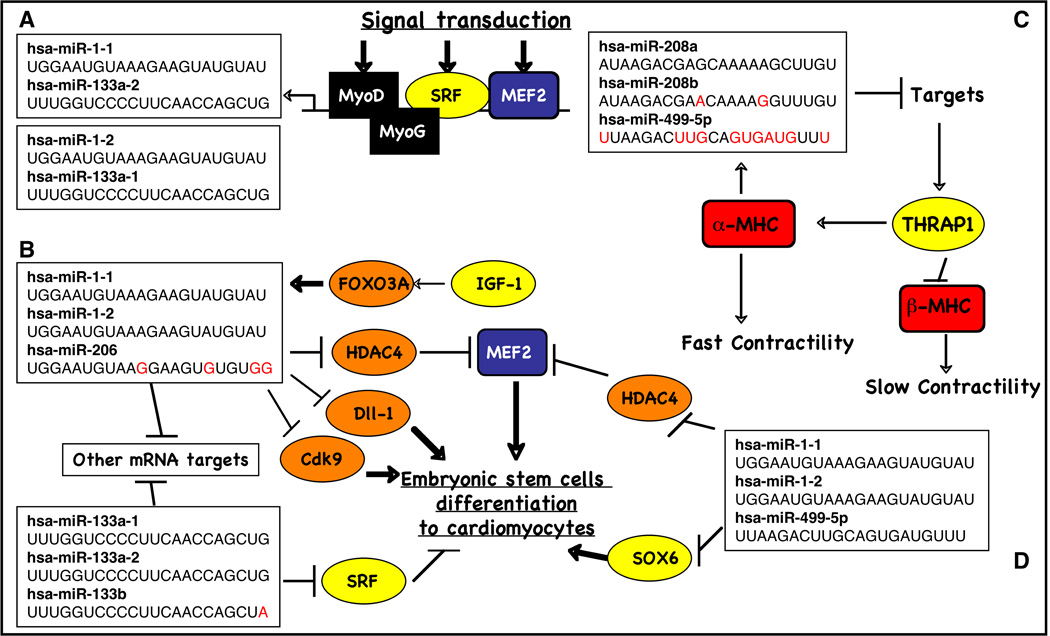

A subset of miRNAs, miR-1, -133, -206 and -208, are either specifically or highly expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle and are called myomiRs [15, 16, 17, 18] (Fig. 2). Members of the miR-1 family are among the most highly conserved of all miRNAs, and are found in organisms ranging from nematodes and flies to vertebrates. The miR-1 family comprises the miR-1 subfamily and miR-206, the latter being expressed in skeletal but not cardiac muscle. The only cardiac-specific miRNA widely acknowledged to date, miR-208, is encoded in an intron of the alpha-MHC gene (Myh7) [19]. The miR-1 subfamily consists of two closely related transcripts, miR-1-1 and miR-1-2, encoded by distinct genes found on chromosome 2 and 18, respectively. The miR-1 subfamily is expressed together with members of miR-133 family, which comprises miR-133a-1, miR-133a-2 and miR-133b. The miRNA pairs miR-1-1/miR-133a-2 and miR-1-2/miR-133a-1 are encoded by a bicistronic miRNA gene [16; 20; 21; 22; 23]. The primary transcript of miR-1-1/miR-133a-2 is derived from independent ncRNA, whereas the precursor of miR-1-2/miR-133a-1 is encoded on the opposite strand of Mib1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase [16]. Considering the ubiquitous expression pattern of Mib1, the muscle specific expression of miR-1-2/miR-133a-1 must therefore rely on its own promoter, independent from Mib1 transcription.

Figure 2.

Regulating circuit that involves transcription regulators, myomiRs and their targets.

SRF and MEF2 activate skeletal-muscle-specific genes in combination with myogenic basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factors, including myogenic differentiation 1 (MyoD) and myogenin (MyoG) [24; 25] (Fig. 2 and 3). SRF and MEF2 both regulate the expression of miR-1-1/miR133a-2 and miR1-2/miR133a-1 pairs. SRF binds to and activates the enhancer regions of miR-1/miR-133 in vitro and in vivo through a serum response element conserved from fly to human [23]. Similarly, SRF and Mef2 regulate somatic muscle expression through bHLH and Twist in Drosophila [26; 27]. Mef2 can also activate transcription of the bicistronic miR-1/miR-133 transcript via an intragenic muscle-specific enhancer, which provides cooperative temporo-spatial regulation of miRNA expression [20]. SRF enhances the expression of these miRNAs in ventricular and atrial myocytes [21], whereas MEF2 binds to the intronic enhnacer of these miRNA genes to activate their expression in ventricular myocytes.

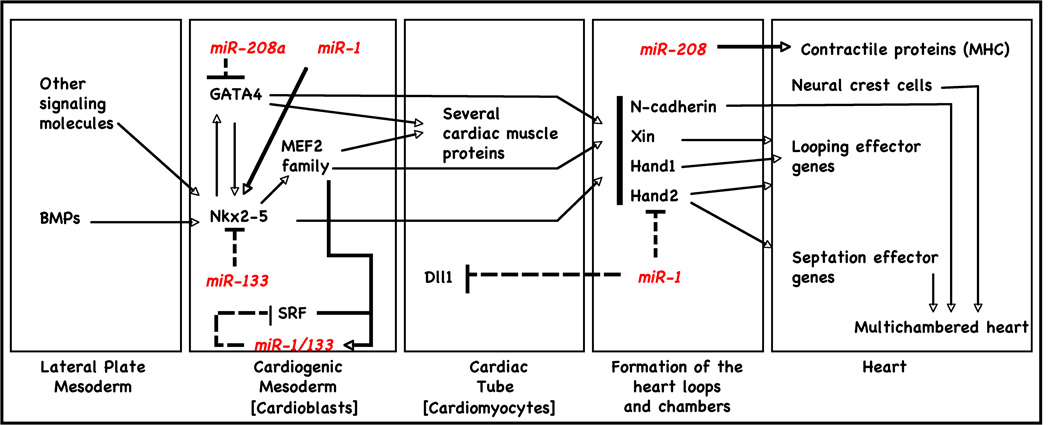

Figure 3.

myomiRs expression and regulation during cardiogenesis.

The miR-208 family is constituted of two transcripts, miR-208a and miR-208b. miR-208a is encoded by an intron of its host gene, alpha-MHC. Both miR-208a and alpha-MHC are cardiac specific and are concurrently expressed during development, suggesting that their expression levels are controlled by a common regulatory element [28]. miR-208b, which shares a high level of sequence similarity with miR-208a, is located within an intron of the gene encoding beta-MHC [29]. miR-499, a novel miRNA associated with cardiomyocyte progenitor cells,, is located in an intron of the myosin heavy chain 7b (Myh7b) gene [29; 30].

myomiRs regulate cardiomyocyte development

Cardiac- and skeletal-muscle development begin when mesoderm stem cells adopt muscle-specific fates in response to cues from adjacent tissues [31; 32]. During differentiation of embryonic stem (ES) cells into aggregates called embryoid bodies (EBs), which to a limited extent recapitulate embryonic development, cardiomyocytes are among the first cell types to arise (Fig. 3). During early cell fate decisions of mouse and human ES cells in mesoderm, miR-1 and miR-133 are functionally expressed to promote mesoderm induction and suppress differentiation into the ectodermal or endodermal lineages in animals such as zebrafish and mice [16; 18; 33]. miR-1 and miR-133 have antagonistic effects on further adoption of muscle lineages. miR-1 promotes differentiation of cardiac progenitors and exit from the cell cycle in mammals and flies [23; 26; 34]. In contrast, miR-133 inhibits differentiation of skeletal myoblasts and maintains them in a proliferative state [16]. Furthermore, while miR-1-1 is initially strongly expressed in the less proliferative inner curvature of the heart loop and in atria, miRNA-1-2 can be found mainly in the ventricles [35]. This suggests that there may be differential regulation of miR-1 and miR-133 to regulate their target mRNA in the muscle differentiation pathway, and further analysis of these targets might be useful in identifying potential clinical applications of miR-1 and miR-133.

Overexpression of miR-1 in a transgenic mouse model resulted in a phenotype characterized by thin-walled ventricles from premature differentiation and early withdrawal of cardiomyocytes from the cell cycle [23]. Conversely, hearts of adult miR-1-2 knockout mice presented thickened chamber walls from prolonged hyperplasia [34]; many of the embryos from these mice suffered from ventricle septal defects. This effect may be partially mediated by Hand2, which regulates expansion of ventricular cardiomyocytes by inhibiting cardiomyocyte progenitor proliferation [34; 36]. Impaired expression of miR-133 was responsible for increased proliferation and altered cardiac tissue formation with disorganized looping and chamber formation. Along with miR-1, these two opposing effects demonstrate the critical importance of correct timing and dosage of miRNAs for heart development [35].

Takaya et al [37] investigated the expression profiles of miR-1, miR-133, and miR-143 during myocardial differentiation of mouse ES cells and found that all of these miRNAs were increased during spontaneous differentiation. Overexpression of miR-1 or miR-133, but not that of miR-143, inhibited the expression of cardiac genes. miR-1 inhibited cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (Cdk9) translation in ES cells, suggesting that miR-1 regulates myocardial differentiation in part by repressing Cdk9 post-transcriptionally. In addition, several direct targets of miR-1 have been described in vivo (Table 1), including Hand2, a transcription factor required for expansion of cardiac progenitors and promotion of ventricular cardiomyocyte expansion [23; 34; 38; 39], and the Notch Delta ligand in Drosophila [26]. Kwon et al provide evidence that miR-1 targets Notch Delta ligand transcripts, supporting a potential mechanism for the expansion of cardiac and muscle progenitor cells in vivo by targeting a pathway required for progenitor cell specification and asymmetric cell division. Similarly, Delta-like 1 (Dll-1), a human homolog of the Notch Delta, is translationally repressed in miR-1 expressing mouse ES cells. Depletion of Dll-1 from mouse ES cells results in a bias toward the cardiac lineage similar to the repression seen in fly, while suppressing endoderm and neuroectoderm differentiation [40]. Furthermore, miR-1 has highly relevant in silico targets that include Ras GTPase–activating protein (RasGAP), Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb), and fibronectin, which Sayed et al confirmed to be valid in vivo targets as well [41].

Table 1.

miRNAs associate with cardiac defects.

IGF-1 is a member of a family of proteins involved in mediating growth and development. Elia et al demonstrated not only through IGF-1 stimulation but also with transfection of AKT or its downstream transcription factor Foxo3a that the IGF-1 pathway controls miR-1 expression [42]. As expected, overexpression of AKT in neonatal cardiomyocytes reduces miR-1 expression, whereas overexpression of Foxo3a increases the miR-1 level. These data are further supported by the identification of IGF-1R as a miR-1 target. Due to the main role of the IGF-1 signaling pathway in heart development and its novel association with miR-1 expression, it would be interesting to further investigate the transcriptional process involved in insulin-regulated miR-1 expression. Together, the reciprocal activation state of the IGF-1 signal transduction cascade regulates miR-1 expression through the Foxo3a transcription factor [42], demonstrating a feedback loop between miR-1 expression and the IGF-1 signal, at least in mouse neonatal cardiomyocytes.

miR-208a has been investigated in cardiomyocyte development particularly due to its involvement in regulating MHC isoform switching. Mice lacking miR-208a fail to upregulate β-MHC (Myh7) under stress and do not develop hypertrophy [28]. Disruption of miR-208a resulted in ectopic activation of the fast skeletal muscle gene program. These gene expression effects were induced by direct inhibition of the thyroid receptor-associated protein THRAP1 [19; 28]. THRAP1 acts as a co-regulator of the thyroid receptor to suppress β-MHC expression. In response to stress, miR-208a inhibits THRAP1, which in turn reduces thyroid receptor signalling, leading to increased β-MHC expression and predictably poorer cardiac function. Thrap1, myostatin and the transcription factor GATA4 are regulated concertedly by miR-208a on gain- and loss-of-function mouse models, regulating cardiac hypertrophy and conduction [19]. Deletion of miR-208b did not alter β-MHC expression; thus, miR-208a appears to function as the most “ upstream” and dominant regulatory miRNA to control expression of both slow myosins β-MHC and Myh7b and their corresponding intronic miRNAs in the heart. miR-208b and miR-499 play redundant roles in the specification of muscle fiber identity by activating slow and repressing fast myofiber gene programs [43]. In another study, miR-499 was investigated in association with miR-1 to regulate the proliferation of human cardiomyocyte progenitor cells (CMPCs) [30]. In a unique model, human fetal CMPCs were isolated, cultured, and efficiently differentiated into beating cardiomyocytes. miRNA expression profiling demonstrated that muscle-specific miR-1 and miR-499 were highly upregulated in differentiated cells. Transient transfection of miR-1 and miR-499 in CMPC enhanced differentiation into cardiomyocytes, in part via the repression of HDAC4 or Sox6.

myomiRs in heart disease

Recent studies have established a direct role for miRNAs in normal heart development and function, implying the potential involvement of this class of novel regulators in cardiac disease. Dysregulation of miRNA expression during hypertrophic growth has recently been reported to occur in the hearts of mice subjected to traverse aortic constriction (TAC) [33; 41; 44], in transgenic calcineurin mice [45], in mice with physiological hypertrophy [33], and most importantly, in human heart diseases [33; 45]. In another study, miRNA expression was profiled in biopsy specimens or explanted hearts from 67 patients diagnosed with aortic stenosis, ischemic cardiomyopathy, or idiopathic cardiomyopathy [46]. Of 87 miRNAs evaluated, the expression of 43 was significantly different from that in normal hearts in at least one group; 7 showed responses common to all (let-7c, miR-23a, miR-100, miR-103, miR-140, and miR-214 increased, whereas miR-126 decreased). These data suggest that although levels of only a few miRNAs are increased or reduced in response to heart failure, many others are regulated in direct response to the pathological cause of the heart failure syndrome. This study also documented that cardiac-specific miRNAs (miR-1, mir-133, and miR-208) are impaired in hearts with cardiomyopathy.

Given that miRNAs are involved in cardiovascular disease, the study of miRNA transcriptomes may allow us to develop diagnostic and/or prognostic tools. On one side, the profile of miRNA expression has been shown to serve as an important phenotypic signature. On the other side, specific miRNAs might harbor prognostic significance, defining the response to therapy and survival, and some might even represent early warning markers of disease [47]. However, much more work needs to be done to better define miRNA profiles in the cardiology setting. Individual miRNAs are dysregulated either negatively or positively with disease, so strategies are needed to counteract misexpression through reconstituting and targeting regimes. miRNA can be replenished with synthetic miRNAs (miR-mimics), which are short lengths of RNA that usually contain the same sequence as the endogenous miRNA but have chemically modified backbone sugars. This approach has been used to repress the cardiac pacemaker genes HCN2 or HCN4 in rat cardiomyocytes, thus avoiding miR-1-related effects on other proteins [48]. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) or anti-miRNA oligonucleotides (AMOs) can be synthesized to be complementary to miRNA or their precursors, and thus they block either miRNA biogenesis or the incorporation of mature miRNA into the RISC or miRNA biogenesis. Systemic administration of AMOs has been reported to be effective in inhibiting cardiac miRNAs and altering cardiac phenotypes [33; 49]. Overall, it is postulated that recently developed tools (including miRNA sponges and antagomirs) have great potential to become powerful tools to inhibit “disease miRNAs” in patients with cardiovascular disease. Conversely, it is conceivable to predict that increasing the expression level of “healthy miRNAs” could improve cardiac function.

Conclusion

miRNAs are important regulators of cell fate determination, differentiation, proliferation, and other processes during embryogenesis and in adult life. Convincing evidences have, through complementary approaches, ascertained the importance of the miRNA pathway in maintaining cardiomyocyte function and development. The unique expression signature of miRNAs in heart development might eventually provide an additional diagnostic tool to assess heart diseases. Significant progress has been made in the understanding of cardiomyocyte development and miRNA-mediated mechanisms have been explored, but knowledge of the underlying networks is still incomplete. The biology of miRNAs is a young research area and there are many more unanswered questions. Clearly, future investigation and understanding of the molecular mechanisms for miRNA function will be the next key step in therapeutic development. We are optimistic that the tiny miRNAs will hugely impact cardiovascular biology and medicine.

Acknowledgements

Research in the Wang lab was supported by the March of Dimes Foundation, Muscular Dystrophy Association and the NIH. DZ Wang is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

Contributor Information

Andrea P. Malizia, Department of Cardiology, Children's Hospital Boston, Harvard Medical School, 320 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA

Da-Zhi Wang, Department of Cardiology, Children's Hospital Boston, Harvard Medical School, 320 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA. dwang@enders.tch.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993 Dec;75(5):843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston RJ, Hobert O. A microRNA controlling left/right neuronal asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003 Dec;426(6968):845849. doi: 10.1038/nature02255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Carthew RW. A microRNA mediates EGF receptor signaling and promotes photoreceptor differentiation in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 2005 Dec;123(7):1267–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berezikov E, Thuemmler F, van Laake LW, Kondova I, Bontrop R, Cuppen E, Plasterk RH. Diversity of microRNAs in human and chimpanzee brain. Nat Genet. 2006 Dec;38(12):1375–1377. doi: 10.1038/ng1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004 Jan;32:D 109–D 111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2002 Sep;21(17):4663–4670. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mourelatos Z, Dostie J, Paushkin S, Sharma A, Charroux B, Abel L, Rappsilber J, Mann M, Dreyfuss G. miRNPs: a novel class of ribonucleoproteins containing numerous microRNAs. Genes Dev. 2002 Mar;16(6):720–728. doi: 10.1101/gad.974702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004 Oct;23(20):4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng Y, Cai X, Cullen BR. Use of RNA polymerase II to transcribe artificial microRNAs. Methods Enzymol. 2005;392:371–380. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)92022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregory RI, Chendrimada TP, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2005 Nov;123(4):631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004 Jul;5(7):522–531. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003 Dec;115(7):787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010 Feb;11(2):113–127. doi: 10.1038/nrm2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sethupathy P, Megraw M, Hatzigeorgiou AG. A guide through present computational approaches for the identification of mammalian microRNA targets. Nat Methods. 2006 Nov;3(11):881–816. doi: 10.1038/nmeth954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callis TE, Wang DZ. Taking microRNAs to heart. Trends Mol Med. 2008 Jun;14(6):254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2006 Feb;38(2):228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002 Apr;12(9):735–739. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wienholds E, Kloosterman WP, Miska E, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Berezikov E, de Bruijn E, Horvitz HR, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RH. MicroRNA expression in zebrafish embryonic development. Science. 2005 Jul;309(5732):310–311. doi: 10.1126/science.1114519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callis TE, Pandya K, Seok HY, Tang RH, Tatsuguchi M, Huang ZP, Chen JF, Deng Z, Gunn B, Shumate J, Willis MS, Selzman CH, Wang DZ. MicroRNA-208a is a regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and conduction in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009 Sep;119(9):2772–2786. doi: 10.1172/JCI36154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu N, Williams AH, Kim Y, McAnally J, Bezprozvannaya S, Sutherland LB, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. An intragenic MEF2-dependent enhancer directs muscle-specific expression of microRNAs 1 and 133. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007 Dec;104(52):20844–20849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu Z, Li A, Zhang SX, Schwartz RJ. Serum response factor micromanaging cardiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19(6):618–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao PK, Kumar RM, Farkhondeh M, Baskerville S, Lodish HF. Myogenic factors that regulate expression of muscle-specific microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006 Jun;103(23):8721–8726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602831103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005 Jul;436(7048):214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKinsey TA, Zhang CL, Olson EN. Signaling chromatin to make muscle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002 Dec;14(6):763–772. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potthoff MJ, Olson EN. MEF2: a central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development. 2007 Dec;134(23):4131–4140. doi: 10.1242/dev.008367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon C, Han Z, Olson EN, Srivastava D. MicroRNA1 influences cardiac differentiation in Drosophila and regulates Notch signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005 Dec;102(52):18986–18991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509535102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sokol NS, Ambros V. Mesodermally expressed Drosophila microRNA-1 is regulated by Twist and is required in muscles during larval growth. Genes Dev. 2005 Oct;19(19):2343–2354. doi: 10.1101/gad.1356105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Rooij E, Olson EN. MicroRNAs: powerful new regulators of heart disease and provocative therapeutic targets. J Clin Invest. 2007 Sep;117(9):2369–2376. doi: 10.1172/JCI33099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M, Lin C, Socci ND, Hermida L, Fulci V, Chiaretti S, Foà R, Schliwka J, Fuchs U, Novosel A, Müller RU, Schermer B, Bissels U, Inman J, Phan Q, Chien M, Weir DB, Choksi R, De Vita G, Frezzetti D, Trompeter HI, Hornung V, Teng G, Hartmann G, Palkovits M, Di Lauro R, Wernet P, Macino G, Rogler CE, Nagle JW, Ju J, Papavasiliou FN, Benzing T, Lichter P, Tam W, Brownstein MJ, Bosio A, Borkhardt A, Russo JJ, Sander C, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007 Jun;129(7):1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sluijter JP, van Mil A, van Vliet P, Metz CH, Liu J, Doevendans PA, Goumans MJ. MicroRNA-1 and -499 Regulate Differentiation and Proliferation in Human-Derived Cardiomyocyte Progenitor Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010 Jan; doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.197434. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.197434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buckingham M. Myogenic progenitor cells and skeletal myogenesis in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006 Oct;16(5):525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solloway MJ, Harvey RP. Molecular pathways in myocardial development: a stem cell perspective. Cardiovasc Res. 2003 May;58(2):264–277. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carè A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, Bang ML, Segnalini P, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Elia L, Latronico MV, Høydal M, Autore C, Russo MA, Dorn GW, 2nd, Ellingsen O, Ruiz-Lozano P, Peterson KL, Croce CM, Peschle C, Condorelli G. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007 May;13(5):613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao Y, Ransom JF, Li A, Vedantham V, von Drehle M, Muth AN, Tsuchihashi T, McManus MT, Schwartz RJ, Srivastava D. Dysregulation of cardiogenesis, cardiac conduction, and cell cycle in mice lacking miRNA-1-2. Cell. 2007 Apr;129(2):303–317. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catalucci D, Latronico MV, Condorelli G. MicroRNAs control gene expression: importance for cardiac development and pathophysiology. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008 Mar;1123:20–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McFadden DG, Barbosa AC, Richardson JA, Schneider MD, Srivastava D, Olson EN. The Hand1 and Hand2 transcription factors regulate expansion of the embryonic cardiac ventricles in a gene dosage-dependent manner. Development. 2005 Jan;132(1):189–201. doi: 10.1242/dev.01562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takaya T, Ono K, Kawamura T, Takanabe R, Kaichi S, Morimoto T, Wada H, Kita T, Shimatsu A, Hasegawa K. MicroRNA-1 and MicroRNA-133 in spontaneous myocardial differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Circ J. 2009 Aug;73(8):1492–1497. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srivastava D, Thomas T, Lin Q, Kirby ML, Brown D, Olson EN. Regulation of cardiac mesodermal and neural crest development by the bHLH transcription factor, dHAND. Nat Genet. 1997 Jun;16(2):154–160. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamagishi H, Yamagishi C, Nakagawa O, Harvey RP, Olson EN, Srivastava D. The combinatorial activities of Nkx2.5 and dHAND are essential for cardiac ventricle formation. Dev Biol. 2001 Nov;239(2):190–203. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ivey KN, Muth A, Arnold J, King FW, Yeh RF, Fish JE, Hsiao EC, Schwartz RJ, Conklin BR, Bernstein HS, Srivastava D. MicroRNA regulation of cell lineages in mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008 Mar;2(3):219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayed D, Hong C, Chen IY, Lypowy J, Abdellatif M. MicroRNAs play an essential role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2007 Feb;100(3):416–424. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257913.42552.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elia L, Contu R, Quintavalle M, Varrone F, Chimenti C, Russo MA, Cimino V, De Marinis L, Frustaci A, Catalucci D, Condorelli G. Reciprocal regulation of microRNA-1 and insulin-like growth factor-1 signal transduction cascade in cardiac and skeletal muscle in physiological and pathological conditions. Circulation. 2009 Dec;120(23):2377–2385. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.879429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Rooij E, Quiat D, Johnson BA, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Kelm RJ, Jr, Olson EN. A Family of microRNAs encoded by myosin genes governs myosin expression and muscle performance. Dev Cell. 2009 Nov;17(5):662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tatsuguchi M, Seok HY, Callis TE, Thomson JM, Chen JF, Newman M, Rojas M, Hammond SM, Wang DZ. Expression of microRNAs is dynamically regulated during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007 Jun;42(6):1137–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Rooij E, Sutherland SL, Liu N, Williams AH, McAnally J, Gerard RD, Richardson JA, Olson EN. A signature pattern of stress-responsive microRNAs that can evoke cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Nov;103(48):18255–18260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608791103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ikeda S, Kong SW, Lu J, Bisping E, Zhang H, Allen PD, Golub TR, Pieske B, Pu WT. Altered microRNA expression in human heart disease. Physiol Genomics. 2007 31;:367–373. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00144.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Latronico MV, Condorelli G. MicroRNAs and cardiac pathology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009 Jun;6(6):419–429. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao J, Yang B, Lin H, Lu Y, Luo X, Wang Z. Novel approaches for gene-specific interference via manipulating actions of microRNAs: examination on the pacemaker channel genes HCN2 and HCN4. J Cell Physiol. 2007 Aug;212(2):285–292. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, Galuppo P, Just S, Rottbauer W, Frantz S, Castoldi M, Soutschek J, Koteliansky V, Rosenwald A, Basson MA, Licht JD, Pena JT, Rouhanifard SH, Muckenthaler MU, Tuschl T, Martin GR, Bauersachs J, Engelhardt S. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature. 2008 Dec;456(7224):980–984. doi: 10.1038/nature07511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao J, Luo X, Lin H, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Wang N, Zhang Y, Yang B, Wang Z. MicroRNA miR-133 represses HERG K+ channel expression contributing to QT prolongation in diabetic hearts. J Biol Chem. 2007 Apr;282(17):12363–12367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang B, Lin H, Xiao J, Lu Y, Luo X, Li B, Zhang Y, Xu C, Bai Y, Wang H, Chen G, Wang Z. The muscle-specific microRNA miR-1 regulates cardiac arrhythmogenic potential by targeting GJA1 and KCNJ2. Nat Med. 2007 Apr;13(4):486–491. doi: 10.1038/nm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen JF, Murchison EP, Tang R, Callis TE, Tatsuguchi M, Deng Z, Rojas M, Hammond SM, Schneider MD, Selzman CH, Meissner G, Patterson C, Hannon GJ, Wang DZ. Targeted Deletion of Dicer in the Heart Leads to Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Feb;105(6):2111–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710228105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dong S, Cheng Y, Yang J, Li J, Liu X, Wang X, Wang D, Krall TJ, Delphin ES, Zhang C. MicroRNA expression signature and the role of microRNA-21 in the early phase of acute myocardial infarction. J Biol Chem. 2009 Oct;284(43):29514–29525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]