Targeting XLαs expression to the mouse renal proximal tubule augments Gsα-mediated responses and mitigates the PTH-resistance phenotype observed in mice with maternal Gsα ablation.

Abstract

XLαs, a variant of the stimulatory G protein α-subunit (Gsα), can mediate receptor-activated cAMP generation and, thus, mimic the actions of Gsα in transfected cells. However, it remains unknown whether XLαs can act in a similar manner in vivo. We have now generated mice with ectopic transgenic expression of rat XLαs in the renal proximal tubule (rptXLαs mice), where Gsα mediates most actions of PTH. Western blots and quantitative RT-PCR showed that, while Gsα and type-1 PTH receptor levels were unaltered, protein kinase A activity and 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1-α-hydroxylase (Cyp27b1) mRNA levels were significantly higher in renal proximal tubules of rptXLαs mice than wild-type littermates. Immunohistochemical analysis of kidney sections showed that the sodium-phosphate cotransporter type 2a was modestly reduced in brush border membranes of male rptXLαs mice compared to gender-matched controls. Serum calcium, phosphorus, and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D were within the normal range, but serum PTH was ∼30% lower in rptXLαs mice than in controls (152 ± 16 vs. 222 ± 41 pg/ml; P < 0.05). After crossing the rptXLαs mice to mice with ablation of maternal Gnas exon 1 (E1m−/+), male offspring carrying both the XLαs transgene and maternal Gnas exon 1 ablation (rptXLαs/E1m−/+) were significantly less hypocalcemic than gender-matched E1m−/+ littermates. Both E1m−/+ and rptXLαs/E1m−/+ offspring had higher serum PTH than wild-type littermates, but the degree of secondary hyperparathyroidism tended to be lower in rptXLαs/E1m−/+ mice. Hence, transgenic XLαs expression in the proximal tubule enhanced Gsα-mediated responses, indicating that XLαs can mimic Gsα in vivo.

The stimulatory heterotrimeric G protein mediates intracellular generation of cAMP in response to many hormones, neurotransmitters, and autocrine/paracrine factors (1, 2). The α-subunit of this ubiquitous signaling protein (Gsα) is encoded by exons 1–13 of the GNAS complex locus (3). In addition to Gsα, GNAS gives rise to several different gene products including extra-large Gsα (XLαs), which uses an alternative upstream promoter and a first exon that splices onto exons 2–13 (4–6). Gsα expression is biallelic in most tissues, whereas XLαs is derived exclusively from the paternal GNAS allele. As a result of sharing all but the first exon, XLαs is identical to Gsα over almost the entire amino acid sequence, with the exception of a unique N terminus that is much larger than the corresponding region of Gsα. At least two other variants of XLαs have been described, including XLαs-N1 (7), which is a C-terminally truncated variant analogous to Gsα-N1 (8), and XXLαs, which is an N-terminally extended variant, which includes the entire coding sequence of XLαs (9, 10). Originally, XLαs was shown to stimulate adenylyl cyclase activity but without the ability to transduce activation of typical Gsα-coupled receptors in cultured cells (11). Additional studies, however, demonstrated functional coupling of XLαs to different classes of Gsα-coupled receptors (12, 13). Likewise, XXLαs has been shown to mediate receptor-activated cAMP stimulation (10).

Disruption of exon XL in mice (Gnasxl knockout mice) results in high early postnatal mortality caused by a failure of the pups to adapt to feeding and the resultant hypoglycemia (14). Surviving Gnasxl knockout mice (i.e., about 20% of the total number of pups in some genetic backgrounds) are hypermetabolic and lean and demonstrate defects in glucose and energy metabolism (14, 15). These phenotypes are similar to those observed in mice heterozygous for the disruption of paternal Gnas exon 2; note that the paternal copy of Gsα is ablated in addition to the complete knockout of XLαs in these mice (16–18). In addition, mice carrying a paternally inherited missense mutation in Gnas exon 6 (V159E) exhibit similar early postnatal defects (19, 20). Of note, children with large paternal deletions of GNAS have also been reported to have feeding difficulties and abnormalities in sc fat tissue that are reminiscent of the findings observed in XLαs knockout mice (21, 22). These phenotypes, which may be attributed to the deficiency of XLαs (and/or XXLαs but not XLαs-N1), differ markedly from those observed in mice heterozygous for disruption of Gsα alone (23, 24), which were generated by disruption of Gnas exon 1 (E1). Mice with maternal (E1m−/+) or paternal (E1+/p−) E1 mutations recapitulate some of the findings in patients with pseudohypoparathyroidism (PHP) type-Ia and pseudopseudohypoparathyroidism, respectively. Furthermore, Gnasxl knockout mice had elevated basal and receptor-stimulated cAMP levels in brown, but not white, adipose tissue (14), suggesting that the in vivo role of XLαs may oppose the role of Gsα. Thus, it has remained unclear whether XLαs is capable of acting similarly to Gsα in vivo.

We have now generated transgenic mice in which XLαs expression is specifically targeted to the renal proximal tubule, a tissue in which Gsα expression is largely restricted to the maternal allele, Gsα mediates most actions of PTH, and alterations in this signaling pathway result in phenotypes that involve PTH actions. Our analyses revealed that renal proximal tubular responses that are typically mediated by Gsα are enhanced in the XLαs transgenic mice compared with control mice, thus demonstrating that XLαs is able to serve as a Gsα-like protein in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Materials

[32P] deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP) and chemiluminescence immunodetection reagents were from NEN Life Science Products (Boston, MA). Restriction endonucleases were obtained from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, MA). BSA-Alexafluor-555 was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). HEK293 and COS7 cells were obtained from ATCC. Taq polymerase and deoxynucleotide triphosphate mix were from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). All other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The plasmid constituting the rat type I γ-glutamyl transpeptidase promoter (γGTI) was provided by Dr. Andrew Stewart (University of Pittsburgh). The cDNA encoding rat XLαs was provided by Dr. William Huttner (University of Heidelberg) (4).

Generation of polyclonal antiserum against rat/mouse XLαs

Polyclonal antiserum was raised in the rabbit against the following epitope, which is conserved between mouse and rat XLαs and located within the XLαs-specific domain: ARAAAARAAYAGPLVWGA. This peptide was synthesized and conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin via a C-terminally added cysteine at the Massachusetts General Hospital Biopolymer Core Facility. Peptide injections and serum collections were performed at Cocalica Biologicals (Reamstown, PA).

Experimental animals

All animal experiments described in this article were conducted in accordance with accepted standards of humane animal care, and the studies were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care. The mouse strain in which Gnas exon 1 is ablated through Cre-lox recombination in all tissues has been previously described (23). Before mating with the mice transgenic for renal proximal tubular expression of XLαs (rptXLαs mice), these mice were crossed with wild-type FVB/N mice for at least three generations. Early postnatal expression of endogenous XLαs was examined in kidneys from wild-type CD1 mice.

Generation of rptXLαs mice

The rat XLαs cDNA was subcloned immediately downstream to the γGTI promoter and exon 1 by using XhoI and HindIII restriction sites. The transgene was then released from the plasmid by XbaI restriction digest and injected into the pronuclei of fertilized eggs from FVB/N females, which were subsequently transferred to pseudopregnant female CD1 mice. Southern blots were performed to identify the pups carrying the transgene. Genomic DNA was isolated from tail tips of 3-wk-old pups, digested with BamHI/BglII, separated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. An XhoI/BamHI fragment of the transgene, which included sequences from XLαs but not Gsα, was radiolabeled by random priming and [32P] deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP) and used as a hybridization probe. Hybridization, washing, and autoradiography were performed as previously described (25).

Northern blot, RT-PCR, and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated by using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) from whole kidneys or proximal tubule enriched renal cortices. The latter were prepared by type-2 collagenase (Whartman) digestion and centrifugation on 45% percoll, as described (26). For Northern blots, total RNA was separated on 1% agarose, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and hybridized to the same probe used in Southern blots. The conditions for hybridization, washing, and autoradiography were as previously described (10). For RT-PCR, 1 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed by using the Superscript First-Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen) in a total reaction volume of 20 μl. One microliter of the first-strand mixture was used as template for PCR. Both mouse and rat XLαs transcripts were amplified by the following forward and reverse primers: 5′-CCCTCTGCTAGAGCCCATC-3′ (exon XL) and 5′-TGAACTGGTTCTCAGGGTTG-3′ (exon 5). Amplicons generated by RT-PCR were purified by using the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and sequenced by using the reverse amplification primer at the Massachusetts General Hospital DNA Core Facility. Forward and reverse primers used to determine tissue-specific amplification of the XLαs transgene were 5′-CAGCCTGCTCTAACGGTTTC-3′ and 5′-ACTCGGCTTCGGTGTCAG-3′, respectively. The forward primer was located in γGTI exon 1 and the reverse primer in XLαs cDNA. For real-time PCR, Quantitect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) was used. As template, 1–2 μl of the first-strand mixture was included in a 20 μl reaction. Expression of Gsα or 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1-α-hydroxylase (Cyp27b1) mRNA was assessed relative to endogenous β-actin and/or succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A (Sdha) transcripts. For quantification of endogenous XLαs expression in early postnatal mouse kidneys, data were normalized to endogenous Gsα mRNA, the levels of which did not appear to change from postnatal d 2 to 6 based on similar cycle threshold values observed during the amplification. Amplification efficiency of each product was ∼2. Data were analyzed as described previously (27). Primers for amplification of rat/mouse XLαs, Gsα, β-actin, and Sdha transcripts were as previously described (10, 28). Note that, while the reverse primer for the amplification of XLαs and Gsα were located in exon 2, the forward primer for the amplification of XLαs was located in the XLαs-specific exon and the forward primer for Gsα was located in exon 1 (which is specific for Gsα). Cyp27b1 mRNA was amplified by using the following primers: 5′-CAAATGGCTTTGTCCCAGAT-3′ (forward) and 5′- GGCTGTCTTCCGAATGGTTA-3′ (reverse). The type-1 PTH/PTHrP receptor (PTHR1) mRNA was amplified by using the following primers: 5′-CGCAGACGATGTCTTTACCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCCACCCTTTGTCTGACTCC-3′ (reverse).

Western blot

HEK293 cells were transfected with rat XLαs cDNA by using the Effectene reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). COS7 cells were transduced with an adenovirus encoding rat XLαs, which was constructed by using the ViraPower Adenoviral Expression System (Invitrogen). Transfected HEK293 and transduced COS7 cells, as well as whole kidneys from 2-d-old (P2) and 6-d-old (P6) CD1 pups were lysed in a Tris-buffered solution containing 150 mm NaCl and 1% Triton and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Proximal tubule enriched renal cortices were lysed directly in 2 × SDS-PAGE loading buffer [125 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 20% Glycerol, and 2% SDS]. Protein concentration was measured by using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce) using BSA as standard. Equal amounts of proteins (10–40 μg) were loaded per well, separated by either 7% or 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto polyvinyldifluoride. For detection of XLαs, either the aforementioned polyclonal anti-XLαs antiserum (1:2000) or a rabbit polyclonal anti-Gsα C terminus antibody (Millipore, Bedford, ME) (1:2000) was used. For detection of Gsα alone, the latter antibody was used. A mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA) was used (1:1000) as gel loading control. Protein kinase A (PKA) activation was assessed in proximal tubule enriched renal cortices of 1-month-old mice. For detection of phosphorylated substrates of PKA, a rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) was used, detecting peptides and proteins that contain a phospho-Ser/Thr residue with arginine at the −3 and −2 positions (RRXS*/T*). Immunoreactivity of each antibody was detected by incubation with anti-IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and visualized by using the Western Lightning Plus enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (PerkinElmer, Foster City, CA). Densitometric analysis of each Western blot was performed by using ImageJ.

Measurement of PTH-induced cAMP accumulation in renal proximal tubules

PTH-induced cAMP accumulation in renal proximal tubules was measured essentially as described (18). Proximal tubule enriched renal cortices isolated from 1-month-old mice were incubated in duplicates at 37°C for 15 min with 10−8 m [Nle8, 21, Y34]rPTH (1–34) (PTH) in a 100-μl buffer containing 1 mm isobutyl methylxanthine. The reactions were stopped by placing the tubes on ice, and tubules were lysed by the addition of 100 μl ice-cold 10% tricholoroacetic acid, followed by centrifugation at 5000 × g at 4°C. The concentration of cAMP in the supernatant was measured by a RIA. Proteins in the pellet were solubilized in a buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.25 N NaOH and quantified by the BCA Protein Reagent (Thermo Scientific) using BSA as standard. The concentration of cAMP in the supernatant was normalized according to the protein concentration in the same reaction tube.

Immunohistochemistry

Kidneys were isolated from 2-month-old rptXLαs mice and wild-type controls. Fixation and cryoprotection were performed as described previously with minor modifications (29, 30). Serial sections (5 μm) were incubated with affinity-purified antibodies against mouse type 2a sodium phosphate cotransporter (Npt2a) (1:1000) and Npt2c (1:1000). Subsequently, sections were treated with Envision (+) rabbit peroxidase (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 30 min at room temperature, and immunoreactivity was detected upon treatment with 0.8 mm diaminobenzidine.

Laser-capture microdissection of renal proximal tubules

Wild-type and transgenic littermates were injected via the tail vein with 1 mg BSA-Alexafluor-555, as previously described (31). Kidneys were removed 15 min after the injection, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and sectioned at 5 μm. Fluorescently labeled proximal tubules were visualized under fluorescent microscopy, microdissected by using a PixCell II LCM system (Arcturus, Mountain View, CA), and lysed directly in the buffer provided by Absolutely RNA nanoprep kit (Strategene). Total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Serum biochemistries

Samples for calcium and phosphorus measurements were obtained from the tail vein, and samples for PTH and 1,25 dihyroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) measurements were collected by submandibular puncture. Ionized calcium was determined by using a Siemens Rapidlab 348 analyzer. Serum phosphorus was measured by using a kit from Wako. Plasma intact PTH and 1,25(OH)2D were measured by ELISA (Immutopics) and radioreceptorassay (Immundiagnostik, Bensheim, Germany), respectively.

Statistical analysis

Mean ± sem of multiple independent measurements were calculated. Student's t test was used for determining statistical significance of differences in PKA activity, Cyp27b1 mRNA levels, and serum biochemistries between wild-type littermates and rptXLαs mice. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test was used for determining statistical significance of biochemical differences among the offspring of male rptXLαs and female E1m−/+ mice. Student's t test was used for comparing the change in blood ionized calcium levels between male E1m−/+ and rptXLαs/E1m−/+ mice. Statistical tests were performed by using GraphPad Prism.

Results

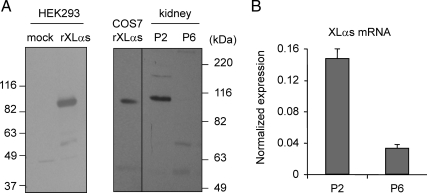

XLαs expression in wild-type mouse kidney declines dramatically within a week after birth

To examine whether XLαs is endogenously expressed in the kidney, we developed a polyclonal antiserum directed against the unique portion of this protein. Western blots using this XLαs-specific antiserum could readily detect rat XLαs protein in whole cell lysates from transfected HEK293 and adenovirally transduced COS7 cells (Fig. 1A). Using whole kidney lysates from 2-d-old wild-type mice (P2), the same antiserum immunoreacted with a protein that appeared to be slightly larger than the recombinant rat XLαs protein expressed in COS7 cells (Fig. 1A). The mouse XL domain is predicted to be larger than rat XL domain (422 vs. 367 amino acids) according to GenBank accession no. AF116268 and X84047, respectively, and therefore the immunoreactive band in the kidney lysates most likely represents mouse XLαs. Interestingly, no immunoreactive bands of similar size were detectable in whole kidney lysates from 6-d-old wild-type mice (P6) (Fig. 1A), suggesting that XLαs expression is significantly reduced in the next 4 d. To confirm this finding, we isolated total RNA from mouse whole kidneys at the same ages and performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR experiments, which demonstrated a dramatic drop in the level of XLαs mRNA between P2 and P6 (Fig. 1B). These findings indicated that, although XLαs is expressed endogenously in early postnatal mouse kidney, its expression level is markedly reduced within the first week after birth.

Fig. 1.

Endogenous XLαs expression in early postnatal kidney of wild-type mouse. A, Western blot analysis using the antirat/mouse XLαs antiserum developed in our lab was used to assess expression of XLαs protein in whole kidneys from P2 and P6 mice. The anti-XLαs antiserum was characterized by analyzing lysates of HEK293 and COS7 cells transfected or adenovirally transduced with cDNA encoding rat XLαs, respectively. B, Real-time RT-PCR revealed a dramatic decline in the renal XLαs mRNA level from P2 to P6. One microgram total RNA was used as template for real-time RT-PCR; data were normalized to the percent of Gsα mRNA, which was amplified with similar cycle thresholds from P2 and P6 samples. Data are representative of three experiments with similar results.

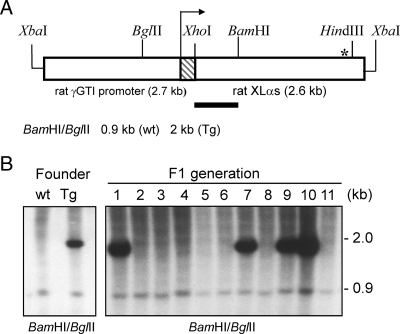

Targeting rat XLαs to the mouse renal proximal tubule

To determine whether XLαs can contribute to Gsα signaling in vivo, we targeted XLαs expression to the renal proximal tubule, in which the cAMP signaling pathway mediates most actions of PTH. For the expression of XLαs in this segment of the nephron, we used the γGTI promoter, which has been previously used for targeting the rasT24 oncogene to this tissue (32). The transgene consisted of the full-length rat XLαs cDNA placed immediately downstream of the rat γGTI promoter and exon 1 (Fig. 2A). Using this XLαs transgene, we obtained five transgenic founders. In each case, Southern blot analysis of tail-tip DNA showed that the transgene was transmitted from the founder to the offspring (i.e., the F1 generation) (Fig. 2B). Offspring from the F1 generation were analyzed at 2 months of age with respect to the expression of the transgene. Northern blots using total RNA from whole kidneys showed a hybridizing band corresponding to the size of rat XLαs mRNA in transgenic mice from lines G14 and G28, but not the remaining three lines (Fig. 3A). The expression level of XLαs was much higher in the G14 line than the G28 line (Fig. 3A). In all samples, including those from wild-type littermates, the Northern blots detected another apparent transcript, which appeared to be smaller than that encoding endogenous mouse XLαs according to previously reported Northern blot data (14) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2.

Development of transgenic mice with targeted ectopic expression of rat XLαs in the renal proximal tubule. A, Transgene for targeting XLαs expression to renal proximal tubules was constructed by placing rat XLαs cDNA immediately downstream of the type-I rat γ-GTI and exon 1 (hatched box); the arrow indicates the start of the transcribed portion; asterisk indicates the approximate location of the termination codon. The probe (horizontal bar) was a 1-kb XhoI/BamHI fragment of the transgene. B, Southern blot analysis of tail-tip DNA demonstrated genomic incorporation of the transgene and its transmission to the F1 generation. Data were obtained from the G28 line; wt, wild-type; Tg, transgenic.

Fig. 3.

Transgenic expression of XLαs in mouse kidney. A, Northern blots using the same probe used in Southern blot analyses indicated expression of rat XLαs transcript in kidneys from the F1 generation of the G14 and G28 founder lines. XLαs expression was not detectable in the remaining three lines. Whole kidneys were isolated at 2 months of age. The presence or the absence of the transgene (Tg) in the genomic DNA is indicated by + or −, respectively. B, Western blot analysis using a polyclonal antiserum against the C terminus of XLαs demonstrated expression of XLαs in total lysates of proximal tubule enriched renal cortices from G14 rptXLαs mice but not wild-type littermates. Lysates from COS7 cells transiently transfected with rat XLαs cDNA were used as a positive control. Results were obtained from two different sets of transgenic and wild-type littermates, and the proteins were separated on either 7% (left) or 10% (right) SDS-PAGE. The exposure of the x-ray film was increased in the image derived from the 10% SDS-PAGE to visualize both XLαs and Gsα. C, XLαs transcript was amplified by RT-PCR using total RNA from 2-month-old rptXLαs mice. Total RNA from P2 mouse kidney and rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells were used as controls. Primers were designed to amplify both mouse and rat XLαs and corresponded to sequences from exon XL (forward) and exon 5 (reverse); RT, reverse transcriptase. D, Nucleotide sequence analysis of RT-PCR amplicons confirmed the expression of the transgenic rat XLαs mRNA in rptXLαs mice. A short segment of the sequence traces is shown as an example. Nucleotides that differ between mouse and rat are indicated by arrows above the sequence traces.

Transgenic rat XLαs protein was also detected in lysates of proximal tubule enriched renal cortices from the G14 transgenic mice by using Western blots and a polyclonal antibody directed against the C-terminal end of XLαs (Fig. 3B). Because the C terminus of XLαs and Gsα are identical, these Western blots also detected endogenous Gsα, which appeared to be expressed at markedly higher levels than the transgene-derived XLαs (Fig. 3B). RT-PCR experiments also detected the expression of the XLαs transgene in 2-month-old rptXLαs mice, using total RNA isolated from whole kidneys and primers specific for both mouse and rat XLαs (but not Gsα) transcripts (Fig. 3C). Although kidney total RNA from 2-month-old wild-type mice did not yield a specific product, total RNA from rat PC12 cells and whole kidneys of wild-type P2 mice, which were used as controls, led to the amplification of the endogenous XLαs transcript (Fig. 3C). Nucleotide sequence analysis of the RT-PCR products confirmed expression of the transgene-derived rat XLαs in kidneys isolated from rptXLαs mice (Fig. 3D). Previously, the γGTI promoter has been shown to be active in the brain and the eye, as well as the renal proximal tubule (32). Consistent with that finding, our RT-PCR experiments revealed the expression of the XLαs transgene in brain and cerebellum, in addition to renal cortex, whereas no expression was detected in spleen, heart, or liver (data not shown).

The expression of XLαs protein in the renal proximal tubule could be detected in the G14 line only. While RT-PCR could amplify the transgene-derived XLαs transcript from whole kidneys of transgenic G28 mice, Western blots were unable to demonstrate any XLαs protein expression (data not shown). Therefore, further studies were conducted by using the G14 line. The rptXLαs mice appeared grossly normal without any defects. No significant differences were present between 2-month-old rptXLαs mice and wild-type littermates regarding body weight (20.3 ± 0.5 vs. 20.3 ± 0.3 g for transgenic vs. wild-type females and 26.4 ± 0.8 vs. 25.5 ± 0.7 g for transgenic vs. wild-type males, respectively). We also did not observe any differences in kidney morphology, as determined by H&E staining of renal sections obtained at the same age (data not shown).

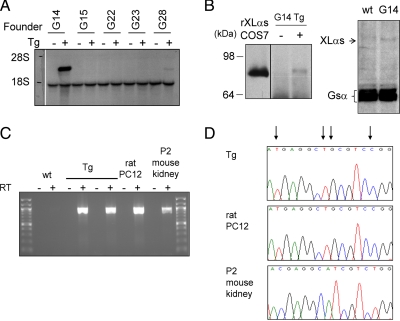

Responses downstream of Gsα signaling are enhanced in the renal proximal tubules of rptXLαs mice

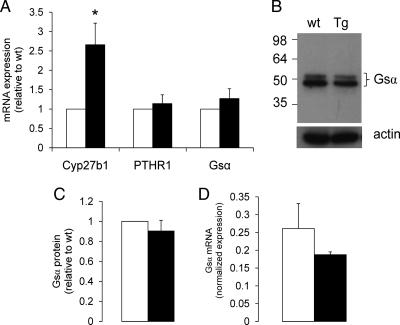

Gsα mediates generation of cAMP by stimulating adenylyl cyclase. Because PTHR1 couples to Gsα, we measured PTH-induced cAMP generation in proximal tubule enriched cortices. Although PTH treatment resulted in a robust elevation of cAMP, no significant differences could be detected between rptXLαs and control mice (Fig. 4A). Basal, nonstimulated cAMP levels also did not appear to be different (3.9 ± 0.6 and 3.8 ± 0.6 pmol/mg protein for wild-type and transgenic littermates, respectively, n = 4). On the other hand, basal activity of PKA, which is downstream of cAMP, was ∼2-fold increased in the renal proximal tubule of rptXLαs mice compared with wild-type mice, as determined by Western blot experiments using an antibody detecting phosphorylated PKA substrates (Fig. 4B). In the renal proximal tubule, the Gsα signaling pathway mediates the transcriptional activation of Cyp27b1 (33, 34), the gene encoding 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1-α-hydroxylase. We thus measured the level of Cyp27b1 mRNA by using real-time quantitative RT-PCR and total RNA isolated from proximal tubule enriched renal cortices. Our experiments showed that the level of Cyp27b1 mRNA was elevated by ∼2.5-fold in the transgenic mice compared with wild-type littermates (Fig. 5A). In contrast, PTHR1 mRNA was not increased in transgenic mice compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 5A). Likewise, both Gsα mRNA (amplified by using primers specific for Gsα) and Gsα protein levels were comparable between transgenic and wild-type littermates (Fig. 5, A–C), indicating that the elevation of Cyp27b1 mRNA levels was not attributable to an increase in the abundance of endogenous PTHR1 or Gsα. Because Gsα is expressed broadly and abundantly, we also isolated renal proximal tubules by laser capture microscopy and, thereby, aimed to minimize contamination by surrounding tissues. Real-time RT-PCR experiments using total RNA from these tubules also ruled out an increase in endogenous Gsα mRNA (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 4.

Elevated basal PKA activity, but not PTH-induced cAMP accumulation, in renal proximal tubules of rptXLαs mice. A, Treatment of proximal tubule enriched renal cortices with 10−8 m PTH in the presence of isobutyl methylxanthine resulted in a marked increase in cAMP accumulation, but this response was similar in wild-type (wt) and rptXLαs (Tg) littermates. Data represent mean ± sem basal (black bars) and PTH-stimulated (gray bars) cAMP levels obtained from four (basal) or five (PTH-stimulated) independent experiments, each including a transgenic mice and a wild-type littermate. B, Western blot analysis using a phospho-PKA substrate antibody showed increased immunoreactivity of multiple proteins in lysates of proximal tubule-enriched renal cortices from rptXLαs mice (Tg) compared with wild-type littermates (wt). The image is representative of five independent experiments with similar results. B, Quantitative analysis of the Western blot data were performed by densitometry. Data are mean ± sem of five independent experiments. Wild-type (white bar); rptXLαs (black bar). *, P < 0.05 compared with wild-type according to Student's t test for paired samples.

Fig. 5.

Increased Cyp27b1 mRNA expression in rptXLαs mice. A, Real-time RT-PCR experiments showed that the proximal tubular abundance of Cyp27b1, but not PTHR1 or Gsα, mRNA is significantly elevated in rptXLαs mice (black bars) compared with wild-type littermates (white bars). Levels were measured first relative to β-actin mRNA, and subsequently, each experiment was normalized to the level in wild-type littermates. Data are mean ± sem of four independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 compared with wild-type according to Student's t test for paired samples. B, Western blot experiments showed that the endogenous Gsα protein levels are comparable in rptXLαs mice (Tg) and wild-type littermates (wt). C, Densitometric analysis of data presented in B; wild-type (white bar); rptXLαs (black bar). Data are mean ± sem of three independent experiments. D, Real-time RT-PCR experiments by using renal proximal tubules isolated by laser capture microscopy confirmed that Gsα transcript levels are not higher in rptXLαs mice (black bar) than wild-type controls (white bar). Expression levels were calculated by using β-actin mRNA as a reference control. Data are mean ± sem of two independent experiments.

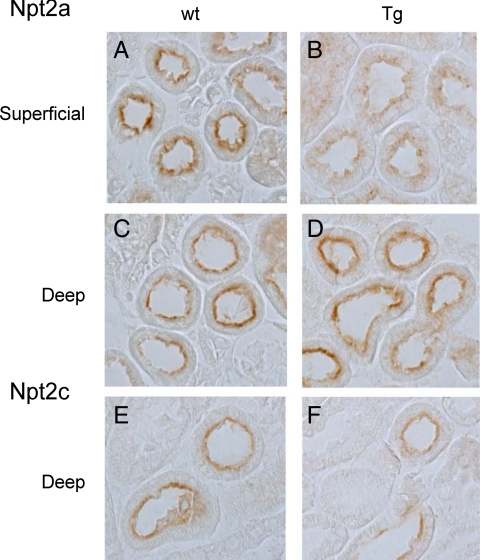

Gsα signaling also mediates, at least in part, the regulation of Npt2a in the proximal renal tubule (35, 36). Immunohistochemical analyses of superficial renal sections using an antibody against the C-terminal portion of Npt2a indicated that, whereas Npt2a was localized to the brush border membrane in male wild-type mice, it was less abundant on the apical surface and localized partially intracellularly in male rptXLαs mice (Fig. 6, A and B). This difference, however, was not consistently observed in female mice (data not shown). In addition, the difference in the abundance and subcellular localization of Npt2a was evident in the superficial, but not deep, cortex (Fig. 6, C and D), consistent with previous studies that identified superficial cortex as the most sensitive site of PTH-induced Npt2a internalization (37, 38). In contrast to these findings with Npt2a, we did not observe a significant change in the expression level of Npt2c, (Fig. 6, E and F), for which immunoreactivity was primarily detected in the deep portion of the renal cortex.

Fig. 6.

Reduced Npt2a expression at the brush border membranes of superficial renal cortex from male rptXLαs mice. Immunohistochemical analysis of kidney sections using an antibody against the C-terminal portion of Npt2a revealed lower abundance and partial internalization of this transporter in the superficial (A and B) but not deep (C and D) cortex of male rptXLαs mice. No remarkable differences were present between transgenic and wild-type mice with respect to the abundance and subcellular localization of Npt2c (E and F). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Cyp27b1 catalyzes the synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D, which directly increases intestinal absorption of calcium and inhibits, as a feedback mechanism, the synthesis and secretion of PTH (39). Reduction of Npt2a expression at the brush border membranes of the renal proximal tubule diminishes reabsorption of phosphate from the glomerular filtrate (39). We thus investigated our transgenic mouse model further to determine whether the observed changes in Cyp27b1 mRNA and Npt2a protein correlate with serum biochemistries. Blood ionized calcium and serum phosphorus and 1,25(OH)2D levels of the rptXLαs mice were not significantly different from those in wild-type controls, although serum 1,25(OH)2D tended to be higher (Table 1). There were no gender-specific differences in serum phosphorus levels between rptXLαs and control littermates (Table 1). Serum PTH, however, was significantly suppressed (∼30%) in rptXLαs mice compared with wild-type littermates, and this was clearly evident in both females and males (Table 1).

Table 1.

Serum biochemistries of wild-type and rptXLαs littermates

| Wild-type | rptXLαs | |

|---|---|---|

| iCa (mm) | 1.14 ± 0.01 (6) | 1.13 ± 0.01 (8) |

| P (mg/dl) | 6.09 ± 0.24 (26) | 6.13 ± 0.21 (41) |

| Females | 6.16 ± 0.29 (15) | 6.34 ± 0.25 (26) |

| Males | 6.00 ± 0.43 (11) | 5.65 ± 0.36 (15) |

| 1,25(OH)2D (pg/ml) | 44.5 ± 5.86 (21) | 57.9 ± 6.28 (31) |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 222 ± 41 (12) | 152 ± 16 (21)a |

| Females | 230 ± 71 (6) | 152 ± 21 (6) |

| Males | 214 ± 48 (6) | 152 ± 22 (15) |

Values are represented as mean ± sem. The number of mice analyzed is given in parentheses. iCa, ionized calcium; P, phosphorus.

Significantly lower than wild-type (P < 0.05) according to Student's t test.

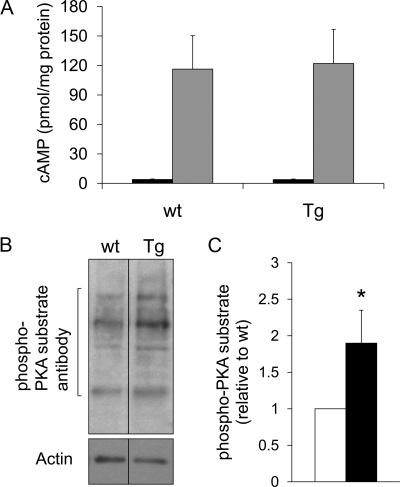

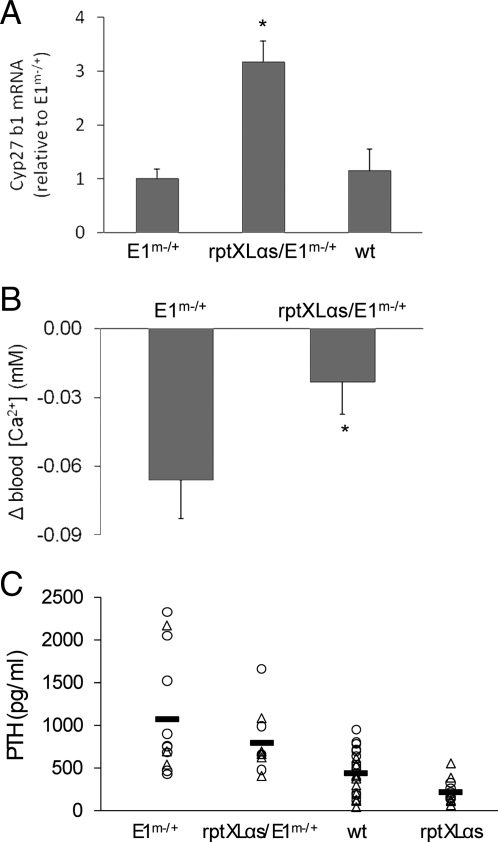

The XLαs transgene partially rescues the PTH-resistance phenotype of mice with ablation of maternal Gsα

Because knockout of the maternal Gsα allele leads to reduced Gsα expression in renal cortex (18, 24), we crossed male rptXLαs mice to female mice heterozygous for Gnas exon 1 ablation (23). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR experiments using total RNA from proximal tubule enriched renal cortices showed that wild-type offspring and offspring with maternal Gnas exon 1 ablation alone (E1m−/+) had similar Cyp27b1 mRNA levels. This finding was rather unexpected, given that maternal Gsα knockout in mice has been reported to cause renal PTH resistance (24). Nonetheless, mice carrying both the XLαs transgene and maternal Gnas exon 1 ablation (rptXLαs/E1m−/+) had significantly higher (∼3-fold) Cyp27b1 mRNA levels than both wild-type and E1m−/+ littermates (Fig. 7A). Offspring from rptXLαs and E1m−/+ crosses were then analyzed with respect to serum biochemistries. Blood ionized calcium was significantly lower in E1m−/+ mice than wild-type littermates. In rptXLαs/E1m−/+ mice, however, results depended on the gender. While marked hypocalcemia was present in female rptXLαs/E1m−/+ and E1m−/+ littermates, the hypocalcemia of male E1m−/+ mice was mostly rescued in male rptXLαs/E1m−/+ mice (Table 2; Fig. 7B). Serum phosphorus appeared to be higher in E1m−/+ mice than wild-type and rptXLαs mice, although the difference was statistically significant when compared with rptXLαs mice only (Table 2). On the other hand, no significant differences existed between male or female E1m−/+ and rptXLαs/ E1m−/+ mice with respect to serum phosphorus (Table 2). Serum 1,25(OH)2D levels did not appear to be significantly different among these genotypes of mice, and no gender-specific distinctions were observed (Table 2). Serum PTH values were variable, particularly for the E1m−/+ mice (Fig. 7C). Overall, the mean serum PTH value for E1m−/+ mice was ∼2.5-fold higher than for wild-type controls, indicating secondary hyperparathyroidism (Fig. 7C; Table 2). Consistent with the results presented above (see Table 1), the rptXLαs offspring had lower serum PTH than wild-type littermates, although the data did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7C; Table 2). Likewise, the rptXLαs/E1m−/+ offspring tended to have lower PTH values than E1m−/+ littermates, but the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 7C; Table 2). Similar trends in serum PTH values were observed in both genders (Table 2).

Fig. 7.

Partial rescue by the XLαs transgene of the phenotype observed in E1m−/+ mice. A, Based on real-time RT-PCR analysis of proximal tubule-enriched renal cortices, Cyp27b1 transcript levels were significantly higher in rptXLαs/E1m−/+ mice than both E1m−/+ and wild-type (wt) littermates. Expression levels were calculated with Sdha mRNA as a reference control, and the mean values in each experiment were normalized to those obtained from E1m−/+ mice. Data represent mean ± sem of at least four independent experiments in which eight E1m−/+ (three males and five females), five rptXLαs/E1m−/+ (three males and two females), and five wild-type (two males and three females) mice were analyzed. *, P < 0.001 compared with E1m−/+ and P < 0.01 compared with wild-type mice by one-way ANOVA. B, The reduction of serum ionized calcium was significantly more pronounced in male E1m−/+ mice than in gender-matched rptXLαs/E1m−/+ mice. Differences were calculated by subtracting individual measurements from the mean value obtained from wild-type mice. Data are mean ± sem (n = 11 for E1m−/+ and n = 7 for rptXLαs/E1m−/+). *, P < 0.05 according to Student's t test. C, Serum PTH values of the offspring from rptXLαs and E1m−/+ crosses showed significantly higher PTH in E1m−/+ mice compared with wild-type (wt) and rptXLαs mice, while the difference between E1m−/+ and rptXLαs/E1m−/+ mice were not statistically significant. Individual data points with calculated mean values (horizontal lines) are shown. The numbers of male and female mice analyzed and the mean values are the same as those given in Table 2. Females and males are depicted by triangles and circles, respectively. Median values were 751, 679, 420, and 182 pg/ml, respectively.

Table 2.

Blood ionized calcium and serum phosphorus, 1,25(OH)2D, and PTH values in offspring from male rptXLαs mice mated with female mice heterozygous for Gnas exon 1 ablation

| E1m−/+ | rptXLαs/E1m−/+ | Wild-type | rptXLαs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iCa (mm) | 1.13 ± 0.01 (15)a,b | 1.14 ± 0.01 (13)c,d | 1.19 ± 0.01 (24) | 1.21 ± 0.01 (11) |

| Females | 1.14 ± 0.02 (4) | 1.10 ± 0.01 (6)e | 1.18 ± 0.02 (9) | 1.20 ± 0.03 (5) |

| Males | 1.13 ± 0.02 (11)e | 1.17 ± 0.01 (7) | 1.19 ± 0.01 (15) | 1.21 ± 0.01 (6) |

| P (mg/dl) | 6.86 ± 0.27 (18)h | 6.73 ± 0.35 (15) | 6.17 ± 0.19 (31) | 5.86 ± 0.21 (19) |

| Females | 6.98 ± 0.21 (6) | 7.16 ± 0.47 (9) | 6.36 ± 0.30 (16) | 6.18 ± 0.30 (9) |

| Males | 6.80 ± 0.41 (12) | 6.10 ± 0.46 (6) | 5.97 ± 0.22 (15) | 5.58 ± 0.27 (10) |

| 1,25(OH)2D (pg/ml) | 73.2 ± 9.45 (15) | 84.8 ± 18.8 (9) | 92.6 ± 12.2 (25) | 88.6 ± 13.2 (18) |

| Females | 70.0 ± 20.9 (6) | 84.9 ± 22.6 (7) | 97.4 ± 18.7 (13) | 80.7 ± 20.0 (9) |

| Males | 75.3 ± 8.80 (9) | 84.4 ± 43.7 (2) | 87.4 ± 16.2 (12) | 96.5 ± 18.1 (9) |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 1079 ± 191 (13)f | 798 ± 116 (10)d | 443 ± 58 (21) | 220 ± 38 (13) |

| Females | 1028 ± 384 (4)g | 696 ± 90 (6) | 313 ± 60 (11) | 221 ± 69 (7) |

| Males | 1102 ± 233 (9)d | 951 ± 261 (4) | 561 ± 84 (10) | 219 ± 28 (6) |

Values are represented as mean ± sem. The number of mice analyzed is given in parentheses. iCa, ionized calcium; P, phosphorus.

P < 0.01 compared with wild-type;

P < 0.001 compared with rptXLαs;

P < 0.05 compared with wild-type;

P < 0.01 compared with rptXLαs;

P < 0.05 compared with wild-type and rptXLαs;

P < 0.001 compared with wild-type and rptXLαs;

P < 0.01 compared with wild-type and rptXLαs;

P < 0.05 compared with rptXLαs (according to one-way ANOVA).

Discussion

To address whether XLαs is able to mimic Gsα in vivo, we generated transgenic mice in which XLαs expression is targeted to the renal proximal tubule. We chose targeting XLαs expression to the renal proximal tubule, because both increases and decreases in proximal tubular Gsα expression have been associated with significant phenotypes (18, 24, 40–42). Because these phenotypes predominantly entail PTH actions, we focused our analyses on the evaluation of PTH-mediated proximal tubular responses and related changes in serum biochemistries. The transgenic mice displayed increased basal levels of PKA activation and renal Cyp27b1 mRNA. In addition, the abundance of Npt2a protein was lower at the brush border membranes of superficial renal cortex, although this finding could be demonstrated more consistently in males rather than females. Moreover, both male and female rptXLαs mice exhibited diminished serum PTH levels with normal serum calcium, phosphorus, and 1,25(OH)2D. This trend in serum biochemistries is nearly identical to that observed in mice in which Gsα expression is almost doubled specifically in the renal proximal tubule because of a loss of imprinting (40, 41). The latter mice showed normal serum calcium and phosphorus despite having diminished serum PTH; note that serum 1,25(OH)2D levels were not reported in those mice (40, 41). Thus, our results clearly indicate that the targeted expression of XLαs in the renal proximal tubule results in augmented Gsα signaling. The observed changes in serum biochemistries probably reflect feedback inhibition of PTH synthesis and secretion attributable to increased renal sensitivity to this hormone. It is likely that an initial increase in 1,25(OH)2D and calcium levels is responsible for the lowering of serum PTH, which then remains low to maintain normocalcemia.

By crossing our transgenic mice to mice with ablation of the maternal Gsα allele (E1m−/+ mice), we could achieve transgenic XLαs expression in a setting where Gsα expression is diminished (23). As previously described for mice in which maternal Gnas exon 1 was disrupted by targeted insertion of a neomycin resistance cassette (24), E1m−/+ mice displayed hypocalcemia and elevated serum PTH, and the targeted expression of XLαs in the proximal tubule resulted in a gender-specific, partial rescue of hypocalcemia and tended to limit the extent of secondary hyperparathyroidism in this PHP type Ia mouse model, providing further evidence that XLαs can mimic Gsα in vivo. The findings regarding Cyp27b1 mRNA levels in E1m−/+ mice, however, were rather unexpected, as reduction of Cyp27b1 mRNA was not observed in these mice despite biochemical findings consistent with PTH resistance. It is conceivable that Cyp27b1 mRNA levels are maintained at normal levels by as-yet-undefined mechanisms in these mice, as well as in mice with the targeted disruption of maternal Gnas exon 1 (24), for which the levels of renal Cyp27b1 mRNA or serum 1,25(OH)2D have not been reported. Alternatively, it is possible that the decrease in Cyp27b1 mRNA attributable to maternal Gsα ablation is confined to such a small segment of the proximal tubule that we were unable to detect this reduction.

The expression level of the XLαs transgene in rptXLαs mice was much lower than endogenous Gsα, and this was also the case in the double mutant offspring of the rptXLαs and E1m−/+ crosses (data not shown). The relatively low expression of the transgene could be the reason that PTH-induced cAMP accumulation was not significantly enhanced in the proximal tubule of rptXLαs mice compared with wild-type controls. The lack of such an enhancement in the PTH-induced cAMP elevation is unlikely to reflect inability of PTHR1 to couple to XLαs, because previous studies have demonstrated that PTHR1 can signal via XLαs in transfected cells, including opossum kidney cells (13), which express PTHR1 endogenously and demonstrate typical characteristics of renal proximal tubular cells (43). Nonetheless, the apparent inability of XLαs to significantly enhance PTH-induced cAMP generation in rptXLαs mice, despite causing elevated basal signaling, may explain why the enhancement of proximal tubular responses typically mediated by PTH was modest in the rptXLαs mice and why the rescue of the PTH-resistance observed in E1m−/+ mice was incomplete. In fact, our results do not rule out the possibility that the phenotypes observed in the rptXLαs mice reflect constitutively elevated cAMP/PKA signaling independent of PTH and/or enhanced signaling via activation of other receptors that are able to couple to XLαs.

Although we detected a small but significant increase in the abundance of proteins phosphorylated by PKA in the renal proximal tubule of the transgenic mice, basal cAMP accumulation was seemingly indistinguishable between transgenic and wild-type littermates. It is conceivable that this result reflects an as-yet-undefined property of XLαs, in that XLαs may increase PKA activation not only by mediating the generation of cAMP but also via other mechanisms. For example, one could speculate that XLαs stabilizes, directly or indirectly, the interactions between PKA and its substrates. While this hypothesis could be explored, a more plausible explanation perhaps is that our cAMP RIA was not sensitive enough to detect the modest elevation of basal cAMP in the tubules of the transgenic mice.

The changes in the subcellular localization and abundance of Npt2a in kidney sections from rptXLαs mice were also quite modest. In addition to the relatively low expression of the transgene, this finding may reflect the involvement of non-PKA-dependent signaling pathways, such as those mediated by protein kinase C, in the regulation of phosphate handling in the proximal tubule (44). The difference between males and females regarding Npt2a could be attributable to estrogen levels. It has been reported that estrogen negatively affects the level of Npt2a in the renal proximal tubule (45), and this tonic inhibition by estrogen might obliterate the effect of the XLαs overexpression on Npt2a in females. Because we did not see a sexual dimorphism with respect to the differences in serum PTH and proximal tubular Cyp27b1 mRNA levels, it is unlikely that the transgene expression is lower in females than in males.

Previous data from mice in which XLαs is ablated suggest that XLαs has unique cellular roles and that it may oppose Gsα in a tissue-specific manner (14). Although the predominant cellular role of XLαs may be different from the role of Gsα, some findings from in vivo mouse models are consistent with a Gsα-like role for XLαs. For example, there is evidence that XLαs ablation in addition to the ablation of one Gsα copy leads to more severe premature hypertrophy of growth plate chondrocytes than the ablation of one Gsα copy alone (28). Thus, while XLαs may functionally oppose Gsα in some cells, it may add to it in others.

We could detect endogenous XLαs expression in kidney shortly after birth, but its level was diminished markedly within a week after birth. A similar decline in XLαs expression has also been reported for adipose tissue (15), suggesting that the main role of this protein in these tissues might be developmental. As such, XLαs may compensate for Gsα deficiency in certain settings, such as in patients with PHP type Ia and type Ib, who have markedly reduced Gsα expression and/or activity in the renal proximal tubule attributable to maternally inherited GNAS mutations yet lack PTH-resistance until after infancy (46, 47). It is thus conceivable that the delay in the development of PTH resistance in these patients reflects compensatory signaling provided by the paternally expressed XLαs. Alternatively, this could result from a delay in the establishment of paternal Gsα silencing, which is the primary reason that maternally inherited GNAS mutations nearly abolish Gsα expression/activity in the renal proximal tubule (18). Further studies are necessary to address these possibilities and thereby elucidate the mechanisms underlying the latency of PTH-resistance in PHP. Nonetheless, we herein demonstrate that XLαs overexpression in the proximal tubule can mitigate PTH-resistance caused by Gsα deficiency, and one could therefore imagine new potential treatments of PHP that aim to increase XLαs expression from the intact paternal GNAS allele.

In summary, we developed transgenic mice in which XLαs expression is targeted to the renal proximal tubule. Data obtained from these mice provide strong evidence that XLαs can add to Gsα signaling in vivo. It will be important to determine whether XLαs replaces Gsα in certain tissues and developmental stages and whether changes in XLαs activity contribute to the pathogenesis of diseases caused by GNAS mutations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Harald Jüppner and Henry Kronenberg (Massachusetts General Hospital) for insightful discussions and critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01DK073911 to M.B). Part of this study was also supported by a NIH Grant DK038452 and by Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (BADERC) Grant DK057521-08 (to V.M.). This work was also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIDDK, NIH. C.A. received a research fellowship award from Gülhane Military Medical Academy, Turkish General Staff, Ankara, Turkey.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- 1,25(OH)2D

- 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D

- Cyp27b1

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D 1-α-hydroxylase

- γGTI

- γ-glutamyl transpeptidase promoter

- Gsα

- G protein α-subunit

- Npt2

- type 2 sodium phosphate cotransporter

- PHP

- pseudohypoparathyroidism

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- PTHR1

- the type-1 PTH/PTHrP receptor

- rptXLαs

- renal proximal tubular expression of XLαs

- Sdha

- succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A

- XLαs

- extra-large Gsα.

References

- 1. Weinstein LS, Liu J, Sakamoto A, Xie T, Chen M. 2004. Minireview: GNAS: normal and abnormal functions. Endocrinology 145:5459–5464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Plagge A, Kelsey G, Germain-Lee EL. 2008. Physiological functions of the imprinted Gnas locus and its protein variants Galpha(s) and XLalpha(s) in human and mouse. J Endocrinol 196:193–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kozasa T, Itoh H, Tsukamoto T, Kaziro Y. 1988. Isolation and characterization of the human Gsα gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:2081–2085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kehlenbach RH, Matthey J, Huttner WB. 1994. XLαs is a new type of G protein. Nature [Erratum (1995) 375:253] 372:804–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hayward B, Kamiya M, Strain L, Moran V, Campbell R, Hayashizaki Y, Bronthon DT. 1998. The human GNAS1 gene is imprinted and encodes distinct paternally and biallelically expressed G proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:10038–10043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peters J, Wroe SF, Wells CA, Miller HJ, Bodle D, Beechey CV, Williamson CM, Kelsey G. 1999. A cluster of oppositely imprinted transcripts at the Gnas locus in the distal imprinting region of mouse chromosome 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:3830–3835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pasolli H, Klemke M, Kehlenbach R, Wang Y, Huttner W. 2000. Characterization of the extra-large G protein alpha-subunit XLalphas. I. Tissue distribution and subcellular localization. J Biol Chem 275:33622–33632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crawford JA, Mutchler KJ, Sullivan BE, Lanigan TM, Clark MS, Russo AF. 1993. Neural expression of a novel alternatively spliced and polyadenylated Gs alpha transcript. J Biol Chem 268:9879–9885 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abramowitz J, Grenet D, Birnbaumer M, Torres HN, Birnbaumer L. 2004. XLalphas, the extra-long form of the alpha-subunit of the Gs G protein, is significantly longer than suspected, and so is its companion Alex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:8366–8371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aydin C, Aytan N, Mahon MJ, Tawfeek HA, Kowall NW, Dedeoglu A, Bastepe M. 2009. Extralarge XLαs (XXLαs), a variant of stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit (Gsα), is a distinct, membrane-anchored GNAS product that can mimic Gsα. Endocrinology 150:3567–3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klemke M, Pasolli H, Kehlenbach R, Offermanns S, Schultz G, Huttner W. 2000. Characterization of the extra-large G protein alpha-subunit XLalphas. II. Signal transduction properties. J Biol Chem 275:33633–33640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bastepe M, Gunes Y, Perez-Villamil B, Hunzelman J, Weinstein LS, Jüppner H. 2002. Receptor-mediated adenylyl cyclase activation through XLalphas, the extra-large variant of the stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit. Mol Endocrinol 16:1912–1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Linglart A, Mahon MJ, Kerachian MA, Berlach DM, Hendy GN, Jüppner H, Bastepe M. 2006. Coding GNAS mutations leading to hormone resistance impair in vitro agonist- and cholera toxin-induced adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate formation mediated by human XLαs. Endocrinology 147:2253–2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Plagge A, Gordon E, Dean W, Boiani R, Cinti S, Peters J, Kelsey G. 2004. The imprinted signaling protein XLalphas is required for postnatal adaptation to feeding. Nat Genet 36:818–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xie T, Plagge A, Gavrilova O, Pack S, Jou W, Lai EW, Frontera M, Kelsey G, Weinstein LS. 2006. The alternative stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit XLalphas is a critical regulator of energy and glucose metabolism and sympathetic nerve activity in adult mice. J Biol Chem 281:18989–18999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu S, Castle A, Chen M, Lee R, Takeda K, Weinstein LS. 2001. Increased insulin sensitivity in Gsalpha knockout mice. J Biol Chem 276:19994–19998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu S, Gavrilova O, Chen H, Lee R, Liu J, Pacak K, Parlow A, Quon M, Reitman M, Weinstein L. 2000. Paternal versus maternal transmission of a stimulatory G-protein alpha subunit knockout produces opposite effects on energy metabolism. J Clin Invest 105:615–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu S, Yu D, Lee E, Eckhaus M, Lee R, Corria Z, Accili D, Westphal H, Weinstein LS. 1998. Variable and tissue-specific hormone resistance in heterotrimeric Gs protein α-subunit (Gsα) knockout mice is due to tissue-specific imprinting of the Gsα gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:8715–8720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Skinner J, Cattanach B, Peters J. 2002. The imprinted oedematous-small mutation on mouse chromosome 2 identifies new roles for gnas and gnasxl in development. Genomics 80:373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kelly ML, Moir L, Jones L, Whitehill E, Anstee QM, Goldin RD, Hough A, Cheeseman M, Jansson JO, Peters J, Cox RD. 2009. A missense mutation in the non-neural G-protein alpha-subunit isoforms modulates susceptibility to obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 33:507–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aldred MA, Aftimos S, Hall C, Waters KS, Thakker RV, Trembath RC, Brueton L. 2002. Constitutional deletion of chromosome 20q in two patients affected with albright hereditary osteodystrophy. Am J Med Genet 113:167–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Genevieve D, Sanlaville D, Faivre L, Kottler ML, Jambou M, Gosset P, Boustani-Samara D, Pinto G, Ozilou C, Abeguile G, Munnich A, Romana S, Raoul O, Cormier-Daire V, Vekemans M. 2005. Paternal deletion of the GNAS imprinted locus (including Gnasxl) in two girls presenting with severe pre- and post-natal growth retardation and intractable feeding difficulties. Eur J Hum Genet 13:1033–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen M, Gavrilova O, Liu J, Xie T, Deng C, Nguyen AT, Nackers LM, Lorenzo J, Shen L, Weinstein LS. 2005. Alternative Gnas gene products have opposite effects on glucose and lipid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:7386–7391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Germain-Lee EL, Schwindinger W, Crane JL, Zewdu R, Zweifel LS, Wand G, Huso DL, Saji M, Ringel MD, Levine MA. 2005. A mouse model of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy generated by targeted disruption of exon 1 of the Gnas gene. Endocrinology 146:4697–4709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fröhlich LF, Bastepe M, Ozturk D, Abu-Zahra H, Jüppner H. 2007. Lack of Gnas epigenetic changes and pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib in mice with targeted disruption of syntaxin-16. Endocrinology 148:2925–2935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Doctor RB, Chen J, Peters LL, Lux SE, Mandel LJ. 1998. Distribution of epithelial ankyrin (Ank3) spliceoforms in renal proximal and distal tubules. Am J Physiol 274:F129–F138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chillambhi S, Turan S, Hwang DY, Chen HC, Jüppner H, Bastepe M. 2010. Deletion of the noncoding GNAS antisense transcript causes pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib and biparental defects of GNAS methylation in cis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:3993–4002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bastepe M, Weinstein LS, Ogata N, Kawaguchi H, Jüppner H, Kronenberg HM, Chung UI. 2004. Stimulatory G protein directly regulates hypertrophic differentiation of growth plate cartilage in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:14794–14799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Segawa H, Yamanaka S, Ohno Y, Onitsuka A, Shiozawa K, Aranami F, Furutani J, Tomoe Y, Ito M, Kuwahata M, Imura A, Nabeshima Y, Miyamoto K. 2007. Correlation between hyperphosphatemia and type II Na-Pi cotransporter activity in klotho mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292:F769–F779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Segawa H, Yamanaka S, Onitsuka A, Tomoe Y, Kuwahata M, Ito M, Taketani Y, Miyamoto K. 2007. Parathyroid hormone-dependent endocytosis of renal type IIc Na-Pi cotransporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292:F395–F403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Skinner M, El Annan J, Futai M, Sun-Wada GH, Bourgoin S, Casanova J, Wildeman A, Bechoua S, Ausiello DA, Brown D, Marshansky V. 2006. V-ATPase interacts with ARNO and Arf6 in early endosomes and regulates the protein degradative pathway. Nat Cell Biol 8:124–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schaffner DL, Barrios R, Massey C, Banez EI, Ou CN, Rajagopalan S, Aguilar-Cordova E, Lebovitz RM, Overbeek PA, Lieberman MW. 1993. Targeting of the rasT24 oncogene to the proximal convoluted tubules in transgenic mice results in hyperplasia and polycystic kidneys. Am J Pathol 142:1051–1060 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brenza HL, Kimmel-Jehan C, Jehan F, Shinki T, Wakino S, Anazawa H, Suda T, DeLuca HF. 1998. Parathyroid hormone activation of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D3–1alpha-hydroxylase gene promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:1387–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murayama A, Takeyama K, Kitanaka S, Kodera Y, Kawaguchi Y, Hosoya T, Kato S. 1999. Positive and negative regulations of the renal 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1alpha-hydroxylase gene by parathyroid hormone, calcitonin, and 1alpha,25(OH)2D3 in intact animals. Endocrinology 140:2224–2231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Traebert M, Volkl H, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. 2000. Luminal and contraluminal action of 1–34 and 3–34 PTH peptides on renal type IIa Na-P(i) cotransporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278:F792–F798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Honegger KJ, Capuano P, Winter C, Bacic D, Stange G, Wagner CA, Biber J, Murer H, Hernando N. 2006. Regulation of sodium-proton exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) by PKA and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:803–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Traebert M, Roth J, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. 2000. Internalization of proximal tubular type II Na-Pi cotransporter by PTH: immunogold electron microscopy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278:F148–F154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lotscher M, Scarpetta Y, Levi M, Halaihel N, Wang H, Zajicek H, Biber J, Murer H, Kaissling B. 1999. Rapid downregulation of rat renal Na/P(i) cotransporter in response to parathyroid hormone involves microtubule rearrangement. J Clin Invest 104:483–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bringhurst FR, Demay MB, Kronenberg HM. 2008. Hormones and disorders of mineral metabolism. In: Kronenberg HM, Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR. eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1203–1268 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Williamson CM, Ball ST, Nottingham WT, Skinner JA, Plagge A, Turner MD, Powles N, Hough T, Papworth D, Fraser WD, Maconochie M, Peters J. 2004. A cis-acting control region is required exclusively for the tissue-specific imprinting of Gnas. Nat Genet 36:894–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu J, Chen M, Deng C, Bourc'his D, Nealon JG, Erlichman B, Bestor TH, Weinstein LS. 2005. Identification of the control region for tissue-specific imprinting of the stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:5513–5518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fröhlich LF, Mrakovcic M, Steinborn R, Chung UI, Bastepe M, Jüppner H. 2010. Targeted deletion of the Nesp55 DMR defines another Gnas imprinting control region and provides a mouse model of autosomal dominant PHP-Ib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:9275–9280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Teitelbaum AP, Strewler GJ. 1984. Parathyroid hormone receptors coupled to cyclic adenosine monophosphate formation in an established renal cell line. Endocrinology 114:980–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cunningham R, Biswas R, Brazie M, Steplock D, Shenolikar S, Weinman EJ. 2009. Signaling pathways utilized by PTH and dopamine to inhibit phosphate transport in mouse renal proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296:F355–F361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Faroqui S, Levi M, Soleimani M, Amlal H. 2008. Estrogen downregulates the proximal tubule type IIa sodium phosphate cotransporter causing phosphate wasting and hypophosphatemia. Kidney Int 73:1141–1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tsang R, Venkataraman P, Ho M, Steichen J, Whitsett J, Greer F. 1984. The development of pseudohypoparathyroidism. Involvement of progressively increasing serum parathyroid hormone concentrations, increased 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and ‘migratory’ subcutaneous calcifications. Am J Dis Child 138:654–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Linglart A, Gensure RC, Olney RC, Jüppner H, Bastepe M. 2005. A novel STX16 deletion in autosomal dominant pseudohypoparathyroidism type Ib redefines the boundaries of a cis-acting imprinting control element of GNAS. Am J Hum Genet 76:804–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]