Abstract

We propose a structural mean modeling approach to obtain compliance-adjusted estimates for treatment effects in a randomized-controlled trial comparing 2 active treatments. The model relates an individual's observed outcome to his or her counterfactual untreated outcome through the observed receipt of active treatments. Our proposed estimation procedure exploits baseline covariates that predict compliance levels on each arm. We give a closed-form estimator which allows for differential and unexplained selectivity (i.e. noncausal compliance-outcome association due to unobserved confounding) as well as a nonparametric error distribution. In a simple linear model for a 2-arm trial, we show that the distinct causal parameters are identified unless covariate-specific expected compliance levels are proportional on both treatment arms. In the latter case, only a linear contrast between the 2 treatment effects is estimable and may well be of key interest. We demonstrate the method in a clinical trial comparing 2 antidepressants.

Keywords: Causal inference, Randomized-controlled trials, Structural mean models

1. INTRODUCTION

Regulators and stakeholders agree that today's drug evaluation process has become expensive to the point of threatening new drug development (DiMasi and others, 2003). At the same time, technological developments have raised the hope for more targeted, individualized medicine. The challenge is to learn as much as possible from pivotal randomized studies, for instance, on departures from randomized treatment, including prescribed changes of treatment, noncompliance, and dose–response relationships (Efron and Feldman, 1991) or more accurate estimation of treatment efficacy (the causal effect of the prescribed dose as intended) (Goetghebeur and Lapp, 1997).

Analysis of data on actual treatments can be complex. In phase III trials, a standard intention to treat (ITT) analysis is a good starting point, especially for drug regulators motivated by the desire for a conservative conclusion. Conventional alternatives such as per-protocol analysis risk serious bias since nonadherence to the study protocol (treatment noncompliance) may be related to treatment and outcome. In this paper we focus on compliance-adjusted linear regression analysis, which uses randomization as an instrument (White, 2005; Sommer and Zeger, 1991; Goetghebeur and Lapp, 1997; Vansteelandt and Goetghebeur, 2003). Technically, our approach is an application of the theoretical developments in Robins (1994) for parameter estimation in structural mean models (SMMs).

Applications of SMMs have hitherto focused on adjusting for observed experimental exposure in trials with a placebo group or an untreated control group. However, active-controlled trials (ACTs) are increasingly warranted as drug treatment becomes standard for ever more diseases (Ellenberg and Temple, 2000). ACTs present new challenges in comparing efficacy. First, unlike in placebo-controlled trials, in ACTs treatment noncompliance need not attenuate the ITT difference. For example, it is possible to observe an ITT difference when 2 treatments are equally efficacious but one is more commonly discontinued. Second, some ACTs are aimed at demonstrating noninferiority of the new treatment to the standard treatment, not superiority. Noncompliance then exaggerates any evidence of equivalence in outcomes, potentially leading to anticonservative behavior (Jones and others, 1996; Vrijens and Urquhart, 2005) as pointed out in the ICH E10 guideline (International Conference On Harmonisation Of Technical Requirements For Registration Of Pharmaceuticals For Human Use, 1999). Third, compliance-adjusted analysis is complicated in ACTs by the lack of a reference group of unexposed participants. Without a directly observed treatment-free reference, even the choice and interpretation of the causal estimand requires attention (Cuzick and others, 1997).

Some authors have tackled compliance adjustment in ACTs by making strong assumptions. Robins (1998) did not exploit the randomization but relied on the untestable no-unmeasured-confounders assumption. Roy and others (2008) added relatively strong untestable parametric assumptions.

This paper studies the potential and limitations of the instrumental variable–based SMM estimator of treatment effects in ACTs. Our case study is a clinical trial of fluoxetine and paroxetine, 2 common antidepressant drugs (Demyttenaere and others, 2008). Like most mental health trials, it is compromised both by noncompliance and by dropout, with nonadherent patients particularly prone to dropout (Dunn and others, 2003).

In Section 2, we formalize the model and its estimating equations for our problem. A closed-form estimator is derived in Section 3. Identifiability conditions are discussed in Section 4. In Section 5, we demonstrate the usage of the estimator on the antidepressant trial. We end with a discussion in Section 6.

2. AN SMM FOR THE COMPARISON OF 2 ACTIVE TREATMENTS

Consider a randomized 2-arm trial, where n patients are randomized to one of 2 active treatments, A or B. We define the following (observed or potential) variables for each patient i = 1,…,n: YiA, YiB: (potential) outcome under assignment to treatment A or B, respectively; Yi0: potential treatment-free outcome; CiA, CiB: (potential) vectors of treatment compliance summaries observed under assignment to A or B, respectively; Xi: a vector of baseline covariates; RiA, RiB: randomization indicators, with value 1, when patient i is randomized to A (B) and 0 otherwise. We will also use the notation Ri = RiA and Yi = YiARiA + YiBRiB for the observed outcome.

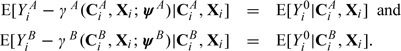

An SMM defines the average effects of assignment to A and B as the expected differences E(YiA − Yi0|Xi,CiA) and E(YiB − Yi0|Xi,CiB) and assumes these are known functions γA and γB of compliance, baseline characteristics, and unknown parameter vectors ψA or ψB, respectively (Goetghebeur and Lapp, 1997). Subtracting postulated effects from corresponding outcomes yields on average the expected treatment-free response, conditional on compliance and baseline characteristics:

|

(2.1) |

It is common to assume the following “exclusion restrictions” hold:

| (2.2) |

Thus, if no active treatment is received, expected outcome equals expected treatment-free outcome.

Equations in (2.1) reflect 2 SMMs, equivalent to the models introduced by Goetghebeur and Lapp (1997). The functions γA(CiA,Xi;ψA) and γB(CiB,Xi;ψB) represent average effects of A or B assignment in a subgroup of patients at given levels of X and CA or CB. The models allow for treatment effect heterogeneity, make no assumptions on the effects of one treatment dose in patients observed to take a different dose and make no assumptions on the association between CA and CB. However, as the Yi0-distribution is not observed, the estimator proposed in Goetghebeur and Lapp (1997) is not directly applicable here.

The main interest lies often in a difference between the 2 treatment effects. Conditioning jointly on CiA and CiB leads to the single equation:

| (2.3) |

Now the difference γA(CiA,Xi;ψA) − γB(CiB,Xi;ψB) has a direct interpretation as the expected outcome difference under A and B assignments in a subgroup of patients with given values of X, CA, and CB. As the 2 potential compliance measures are never jointly observed in a parallel trial, such subgroups are not identified.

By taking expectations conditional on Xi only, either (2.1) or (2.3) implies

| (2.4) |

As the expectations of the variables appearing on the left are estimable from arm A and those on the right from arm B data, (2.4) suggests the following estimation procedure. With ψ = (ψA;ψB), an unbiased estimating equation for ψ is

| (2.5) |

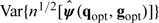

where Hi(ψ) = Yi − RiAγA(CiA,Xi;ψA) − RiBγB(CiB,Xi;ψB); g(Ri,Xi) is any vector with dim(ψ) elements, satisfying E[g(Ri,Xi)|Xi] = 0, and q(Xi) is any function of Xi. Efficient estimates are obtained with optimal choices of g and q. Following Robins (1994), the optimal function qopt is qopt(Xi) = E[Hi(ψ0)|Xi], with ψ0 the true (unknown) value of ψ. A different choice of q(Xi) will not introduce bias in the estimating equation, but the variance of the solution  is a function of Var[Hi(ψ0) − q(Xi)|Xi] and thus depends on how well q(Xi) approximates Hi(ψ0). So a better precision of

is a function of Var[Hi(ψ0) − q(Xi)|Xi] and thus depends on how well q(Xi) approximates Hi(ψ0). So a better precision of  can be achieved by including in Xi covariates that are predictive for the potential treatment-free outcome.

can be achieved by including in Xi covariates that are predictive for the potential treatment-free outcome.

Since E[Hi(ψ0)|Xi] = E[Yi0|Xi] is the expected treatment-free response, it is not directly estimable from the data on either active treatment arm, unlike in the placebo-controlled trial with no contamination in the control arm (Goetghebeur and Lapp, 1997). However, with a parametric model q(Xi) = q(Xi;α), consistent estimates for ψ and α are obtained by simultaneously solving the unbiased estimating equations (2.5) and

| (2.6) |

with d(Xi) being any function of Xi. By analogy with generalized linear models, we choose  .

.

Given q, the optimal function gopt is described in Robins (1994) or Goetghebeur and Lapp (1997):

| (2.7) |

where wopt,i = Var{Hi(ψ)|Xi} − 1 can be dropped if the variance does not change with Xi. When q and g have their optimal forms,  attains the “semiparametric efficiency bound.” If the conditional variance of Hi(ψ) given Xi were to vary on either treatment arm beyond what is expected for the standard generalized linear model, one would weight (2.6) by the inverse variance.

attains the “semiparametric efficiency bound.” If the conditional variance of Hi(ψ) given Xi were to vary on either treatment arm beyond what is expected for the standard generalized linear model, one would weight (2.6) by the inverse variance.

With τ = E[∂Ui(ψ0,g,q)/∂ψ′] and Ω = Var[Ui(ψ0,g,q)], a consistent variance estimator for the estimated parameter vector is derived from the corresponding estimates as

3. CLOSED-FORM ESTIMATOR FOR A LINEAR SMM

A linear SMM is defined by

| (3.1) |

where the vectors ZiA and ZiB may contain compliance summaries (components of CiA and CiB) and their interactions with baseline covariates. This paper focuses on estimation of ψA and ψB and their contrast ψA − ψB, the latter being often of greatest interest, given the trial's objective of direct comparison between treatments A and B. In the absence of an untreated control group, we will show that inference on the contrast ψA − ψB is typically more robust.

Assuming a linear model q(Xi,α) = α′Xi for the dependence of potential treatment-free response on Xi, the optimal g becomes

| (3.2) |

where the expectations can be estimated by regression methods.

Let G, Z, X be matrices with ith row  (or

(or  if the use of weights is indicated), (RiAZiA′,RiBZiB′) and Xi, respectively, and let Y be the column vector with ith element Yi. The estimating equations (2.5) and (2.6) then have matrix representation

if the use of weights is indicated), (RiAZiA′,RiBZiB′) and Xi, respectively, and let Y be the column vector with ith element Yi. The estimating equations (2.5) and (2.6) then have matrix representation

| (3.3) |

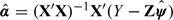

and the closed-form solution for ψ is

| (3.4) |

provided all inverse matrices exist. Here, I is an n×n identity matrix. The parameter vector α can subsequently be estimated as  . When in gopt, E(ZiA|Xi) and E(ZiB|Xi) are estimated from classical linear regression models, this estimator is equivalent to the 2-stage least squares estimator often used in econometrics and social science applications (Maracy and Dunn, 2010). A consistent estimator for the variance–covariance matrix of the estimated parameter vector ψ can be derived from (3.4), as

. When in gopt, E(ZiA|Xi) and E(ZiB|Xi) are estimated from classical linear regression models, this estimator is equivalent to the 2-stage least squares estimator often used in econometrics and social science applications (Maracy and Dunn, 2010). A consistent estimator for the variance–covariance matrix of the estimated parameter vector ψ can be derived from (3.4), as

| (3.5) |

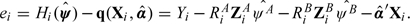

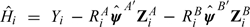

Here,  is the estimated variance of Hi(ψ) (given Xi), obtained as the residual variance:

is the estimated variance of Hi(ψ) (given Xi), obtained as the residual variance:  with df = n − dimψ − dimα and residuals ei defined by

with df = n − dimψ − dimα and residuals ei defined by  The estimator is easy to implement in software supporting simple matrix language. The main practical issue is identifiability of the parameters, which corresponds mathematically to the existence of inverse matrices in (3.4). We discuss this next.

The estimator is easy to implement in software supporting simple matrix language. The main practical issue is identifiability of the parameters, which corresponds mathematically to the existence of inverse matrices in (3.4). We discuss this next.

4. IDENTIFIABILITY

4.1. Condition for identifiability of the 2 distinct parameters in a simple linear SMM

Consider first univariate compliance summaries: (potential) exposures CiA and CiB, for example, the percentage of the assigned dose of drug that would be taken by patient i if assigned to treatment A or B, respectively. We assume Ci ≥ 0, although the methodology can accommodate negative values. The values Ci = 0 have here the special meaning of absence of treatment exposure. For a simple linear SMM, estimating equations are derived from

| (4.1) |

Note that this SMM implies for the ITT treatment effect: E(YiA − YiB) = ψAE(CiA) − ψBE(CiB). In the special case where E(CiA) = E(CiB) = μc, for instance, when compliance can be seen as an attribute of the patient (as in Efron and Feldman, 1991), the ITT treatment difference is proportional to the difference of the 2 SMM parameters: E(YiA − YiB) = (ψA − ψB)μc but this is not generally true. In general, the parameters ψA and ψB are identified under the following condition:

“The two distinct parameters of a simple linear SMM (4.1) comparing each active treatment with treatment free response are identified, unless there exists a constant k such that E(CiB|Xi) = kE(CiA|Xi). In the latter case, only the contrast δ = ψA − kψB is estimable.”

One hence needs baseline covariates which predict compliance differently across randomized groups. This would hold if the 2 treatments were preferred by different patient subcategories.

A detailed discussion on estimation when the 2 separate parameters cannot be estimated, with some practical recommendations, can be found in Section A of the Supplementary Material available at Biostatistics online.

4.2. Identifiability of a multiple linear SMM

For some purposes, a simple linear SMM is an oversimplification and model (3.1) would include the causal effect of multiple exposures or several summaries of dose timing (possibly interacting with certain baseline covariates). For all distinct parameters to be identified, it is then necessary and sufficient that the matrix E(Z|X) with ith row E(Zi|Xi) = E[(ZiA′,ZiB′)′|Xi] is of full column rank. This can happen as long as dim(Xi) ≥ dim(Zi) − 1 and none of the components of E(Zi|Xi) can be expressed as a linear combination of the others. Even then, linear or near-linear dependencies in E(Z|X) can make causal parameter estimates highly variable. They might nevertheless allow for precise estimation of useful contrasts such as δ.

4.3. Simulations

We conducted simulations to study the precision and possible finite sample bias of the estimates, assuming the model (4.1), also examining the performance when parameters are unidentified. Details of simulations are given in Section B of the Supplementary Material available at Biostatistics online.

The results indicate that estimator behaves quite well when the 2 expected compliance measures, given baseline characteristics, are different with correlation 0.75 or even 0.95, with a relatively small finite sample bias in small samples. When the correlation between the 2 expected compliance summaries is 1, but the 2 summaries differ by an additive constant, the estimate is still reasonably precise for sample size of 2,000 and might also work for n = 400. When the 2 summaries differ by a multiplicative constant or are equal, the estimates are more imprecise and in these cases one is unlikely to identify the 2 distinct parameters.

The simulations demonstrate that the difference δ = ψA − ψB is always estimated with much better precision than the 2 distinct parameters ψA and ψB, the SMM algorithm providing unbiased and relatively precise estimates even when the 2 expected compliance summaries are equal.

4.4. Extensions

The linear SMM defined by (3.1) can be applied in a much wider range of applications than the simple situation, where on each arm only one treatment, A or B, is available and the exclusion restriction (2.2) holds. Section C of the Supplementary Material available at Biostatistics online discusses 2 possible extensions. First, one can allow for contamination—treatment A being received by some patients on arm B and treatment B by some patients on arm A, which leads to a special case of an SMM with multivariate compliance summaries, possibly still simplified to a 2-parameter model. Second, one can relax the exclusion restriction by allowing a constant nonzero difference between potential outcomes on arms A and B in addition to the coefficients of the received dose. In this case, the SMM involves 3 causal parameters that may be difficult to identify in practice with reasonable precision.

5. A TRIAL OF 2 ANTIDEPRESSANTS

We apply our method to compare 2 antidepressant treatments, fluoxetine and paroxetine, accounting for variability in drug exposure due to suboptimal compliance with prescribed therapy.

The trial (Demyttenaere and others, 2004), (Demyttenaere and others, 2008) was designed as part of a study to develop an antidepressant compliance questionnaire. It was a double-blind randomized multicentre study in patients with major depressive disorder. 85 patients were randomized to fluoxetine (n = 42, later referred to as treatment A) or paroxetine (n = 43, treatment B), 20 mg/day, for 22 weeks after an initial wash out and run-in period on placebo. The severity of depression was assessed by the Hamilton depression scale at clinic visits before the run-in period (Visit 1), at randomization (Visit 2), after the initial 2 weeks on randomized treatment (Visit 3), and then every 4 weeks for the next 5 months (Visits 4–8). Medication event monitoring systems (MEMS) were used to automatically compile drug dosing histories (Vrijens and others, 2005); treatment compliance was the percentage of prescribed dose actually taken by the patient during a given time period.

As all patients returned their MEMS devices, complete compliance data were available. Also, Hamilton scores at Visits 1 and 2 were available for all 77 patients, but 3, 2, 4, 3, 4, and 8 patients dropped out prior to Visits 3–8, respectively, and so the Hamilton score at final Visit 8 was available for only 53 patients (69%).

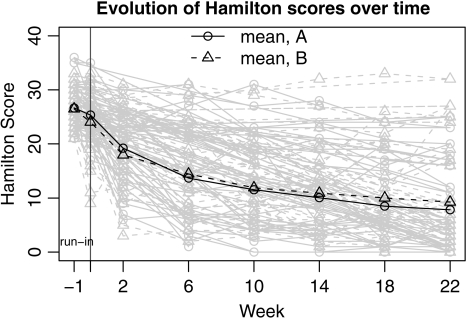

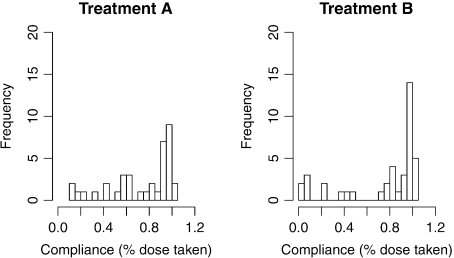

Figure 1 shows the evolution of individual Hamilton scores during the trial. The ITT analysis reveals no significant difference between the 2 treatment arms, although both arms saw significant reduction in average Hamilton scores over the active period (45% at 6 weeks and 76% at 22 weeks). Estimated treatment compliance varied widely between patients (Figure 2). Here, we use the SMM methodology to explore how drug effects compare at different drug-specific compliance levels. To handle dropouts in the data set, we used multiple imputation (Rubin, 1987) assuming the data are missing at random.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of Hamilton scores during the 23 weeks of the trial.

Fig. 2.

Histograms of compliance, estimated as percentage of prescribed dose taken by the time of Visit 8.

5.1. Possible SMMs for the antidepressant trial

Let Ci(j,k) denote the percentage of prescribed pills taken by patient i between Visits j and k and Ciw(j) the percentage of prescribed pills taken during the week before Visit j. Suppose CiA and CiB are vectors with components Ci(j,k) and Ciw(j) for all j and k. We assume the following models for the final (Visit 8) outcomes YiA(8) and YiB(8):

| (5.1) |

These models assume that the effect of each treatment comprises a cumulative effect of the total dose taken since baseline, reflected by ψ1A (ψ1B), and a short-term effect ψ2A (ψ2B). We fit this model and 4 nested models, with either (ψ1A,ψ1B), (ψ2A,ψ2B), (ψ2A,ψ1B), or (ψ1A,ψ2B) being set to equal (0,0), to explore whether one of these effects may be dominant.

5.2. A goodness of fit test

A test for goodness of fit (GOF) is based on

If the parameter estimates ψA and ψB are close to the true values, then the estimates  should have similar expectation, given X, in both randomized groups. So, as a (partial) GOF test, one can test for the interaction effect of R and X in a linear regression model for

should have similar expectation, given X, in both randomized groups. So, as a (partial) GOF test, one can test for the interaction effect of R and X in a linear regression model for  . In complete data, one can use the analysis of variance F-test comparing regression models for

. In complete data, one can use the analysis of variance F-test comparing regression models for  on X and R, with and without the interaction. The numerator and denominator degrees of freedom for the F-statistic are p − q and n − (1 + 2p − q), where p is the number of components in Xi and q is the number of estimated SMM parameters. In the presence of missing data, the testing procedure and degrees of freedom were modified using the formulas by Reiter (2007).

on X and R, with and without the interaction. The numerator and denominator degrees of freedom for the F-statistic are p − q and n − (1 + 2p − q), where p is the number of components in Xi and q is the number of estimated SMM parameters. In the presence of missing data, the testing procedure and degrees of freedom were modified using the formulas by Reiter (2007).

5.3. Results

First, a set of baseline covariates was selected based on the results of separate multiple regression models for compliance summaries and final Hamilton scores on both arms. Details on the covariate selection and multiple imputation procedure are given in Section D of the Supplementary Material available at Biostatistics online.

The resulting estimates for SMM parameters and their standard errors are presented in Table 1. According to the Wald test, all models except Model 5 provide either significant or borderline significant evidence against the null hypothesis that all causal parameters are 0, the p-value for Model 4 being below the conventional α-level of 0.05. Model 3 gives the best fit according to the F-test but the parameter estimates have high variability and the model is hard to interpret. Model 4 is the most convincing model and suggests that treatment A has a more cumulative effect (so CA(2,8) is important), whereas B has a more short-term effect (so Cw,B(8) is important)—both parameter estimates being significantly different from 0. The results are in accordance with the knowledge that fluoxetine (A) has significantly longer half-life than paroxetine (B) (Rosenbaum and others, 1998).

Table 1.

Estimated SMM parameters (standard error), treatment contrast (standard error) for full compliers, and GOF tests for 5 SMMs and the null model

| Coefficient |

Contrast for full compliers | Test for ψ = 0 (p-value) | GOF F (p-value) | ||||

| CA(2, 8) | Cw, A(8) | CB(2, 8) | Cw, B(8) | ||||

| Null | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.41 (0.20) |

| SMM 1 | − 14.7 (7.1) | — | − 9.3 (6.9) | — | − 5.4 (2.9) | 2.8 (0.07) | 0.96 (0.47) |

| SMM 2 | — | − 11.5 (4.6) | — | − 5.7 (4.2) | − 5.7 (3.5) | 3.2 (0.05) | 0.93 (0.50) |

| SMM 3 | − 12.7 (25.2) | 5.6 (18.4) | 22.2 (22.0) | − 31.7 (15.7) | 2.3 (5.9) | 2.3 (0.07) | 0.23 (0.97) |

| SMM 4 | − 15.9 (5.4) | — | — | − 13.4 (6.0) | − 2.5 (3.3) | 4.3 (0.02) | 0.51 (0.84) |

| SMM 5 | — | − 8.6 (5.1) | − 1.5 (4.5) | — | − 7.7 (3.3) | 2.3 (0.11) | 1.32 (0.25) |

The estimated treatment contrast for full compliers (both compliance summaries being equal to 1) is estimated with better precision than the distinct parameters. In the best-fitting Models 3 and 4, the hypothesis of no treatment difference for full compliers cannot be rejected. Model 4 estimates a significant effect of each separate treatment relative to the treatment-free reference, as defined here. Since Figure 2 reveals how few observations directly reflect the (near) treatment-free response, the latter result is model dependent and needs to be interpreted with caution.

In sensitivity analyses, we omitted one or more covariates from the causal analysis. This caused standard errors of the estimated causal effects to increase, but the results remained consistent with those tabulated.

The validity of the SMM approach in the presence of missing data (assuming the data is missing at random) was also tested in our simulation study (Section B of the Supplementary Material available at Biostatistics online). As expected, missing data led to somewhat increased mean squared error of the estimates using multiple imputation, but no biases are observed.

6. DISCUSSION

We have developed SMMs, which provide inferences about the causal effects of treatment, for trials where different arms are assigned different active treatments, in the presence of treatment noncompliance.

We have considered flexible causal models involving several causal parameters. Precise estimation of such models requires the existence of strong baseline predictors for observed exposure on each arm, and the data requirements increase with model dimension. It is common in randomized trials to record the covariates that are known to be associated with the outcome, but the present work highlights the important role of covariates that predict treatment compliance. Ideally, the covariates should produce different predictions for the 2 compliance summaries, as for example, when the treatments differ by aspects that are important to the patient, such as half-life, side effects, frequency of dosage, etc.

Our models assume that the baseline covariates do not modify the causal effect of either treatment. Interaction terms between compliance and baseline covariates could be included in the vector Z (3.1), as was done in placebo-controlled trials (Goetghebeur and Lapp, 1997). However, this cannot be done for all baseline covariates: the parameters are only identified when enough baseline covariates are (differentially) predictive for but are assumed not to freely interact with compliance on arms A or B.

From a clinical perspective, the ability of baseline covariates to identify patients whose compliance is likely to differ under the 2 assignments can help to guide treatment decisions. Our models can be used to estimate the benefit of assignment to treatment A rather than treatment B for a particular patient's set of baseline covariates.

Interpretation of parameters such as ψA and ψB requires care since different causal parameters defined in this paper pertain to different subpopulations. If one starts from (2.1) then ψAcA is the average causal effect of compliance cA compared with no compliance in the subpopulation with compliance cA. Equation (2.3), which conditions on the unobserved joint distribution of CiA and CiB, relies on a stronger assumption which implies that ψAcA − ψBcB is the ITT difference (the expected difference in outcome between assignment to A and assignment to B) for the subpopulation (CA,CB) = (cA,cB). The practical usefulness of this interpretation is limited as long as we have no information on how patients would comply with both treatment assignments. Thus, for example, if CA and CB are defined as percentages of assigned dose then ψA − ψB is the ITT difference in the “perfect compliers” subgroup with CA = CB = 1. However, such a subgroup may not exist or may be hard to identify if it does. It may be more realistic to consider the ITT difference in a subgroup defined by (for example) 0.8 ≤ (CA,CB) ≤ 1.2.

Equations (2.1) involve a counterfactual untreated outcome Y0. In some settings, some patients could not ethically receive no active treatment, so our use of Y0 is questionable. Models of form (2.3) avoid this problem.

In the depression trial analyzed here, (2.3) requires the causal effect of compliance with fluoxetine to be unaffected by the potential compliance of the same patients with paroxetine (and vice versa). There is no obvious reason to expect such interaction, so we interpret the estimated contrast ψA − ψB as the expected ITT difference for those patients whose compliance under either assignment would be close to 1. The causal parameter estimates in the best-fitting SMM seem to reflect known differences in the duration of action of the 2 treatments.

We close by reminding readers that the causal model framework provides some prior structure which our data alone can neither refute nor confirm. Nevertheless, in many problems, the linear SMM is a good first-order approximation to the true average causal effect.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at http://biostatistics.oxfordjournals.org.

FUNDING

UK Medical Research Council (U.1052.00.006) to K.F., I.R.W.; Interuniversity Attraction Poles research network grant P6/03 of the Belgian government (Belgian Science Policy) to E.G.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Cuzick J, Edwards R, Segnan N. Adjusting for non-compliance and contamination in randomized controlled trials. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16:1017–1029. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970515)16:9<1017::aid-sim508>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Adelin A, Patrick M, Walth'ere D, Katrien De B, Mich'ele S. Six-month compliance with antidepressant medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;23:36–42. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f1c1d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Albert A, Mesters P, Dewé W, Debruyckere K, Sangeleer M. Development of an antidepressant compliance questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;110:201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22:151–185. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G, Maracy M, Dowrick C, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Dalgard OS, Page H, Lehtinen V, Casey P, Wilkinson C, Vazquez-Barquero JL. and others Estimating psychological treatment effects from a randomised controlled trial with both non-compliance and loss to follow-up. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;183:323–331. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Feldman D. Compliance as an explanatory variable in clinical trials. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1991;86:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg SS, Temple R. Placebo-controlled trials and active-control trials in the evaluation of new treatments. part 2: practical issues and specific cases. Annals of International Medicine. 2000;133:464–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-6-200009190-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetghebeur E, Lapp K. The effect of treatment compliance in a placebo-controlled trial: regression with unpaired data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series C. 1997;46:351–364. [Google Scholar]

- International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements For Registration of Pharmaceuticals For Human Use. Choice of control group and related issues in clinical trials (E10). Technical Report. The International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. 1999 http://www.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA486.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jones B, Jarvis P, Lewis JA, Ebbutt AF. Trials to assess equivalence: the importance of rigorous methods. British Medical Journal. 1996;313:36–39. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7048.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maracy M, Dunn G. Estimating dose-response effects in psychological treatment trials: the role of instrumental variables. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0962280208097243. (in press: first published online on November 26, 2008). doi: 10.1177/0962280208097243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter JP. Small-sample degrees of freedom for multi-component significance tests with multiple imputation for missing data. Biometrika. 2007;94:502–508. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM. Correcting for non-compliance in randomized trials using structural nested mean models. Communications in Statistics—Theory and Methods. 1994;23:2379–2412. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM. Correction for non-compliance in equivalence trials. Sta tistics in Medicine. 1998;17:269–302. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980215)17:3<269::aid-sim763>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Rotnitzky A, Zhao LP. Estimation of regression coefficients when some regressors are not always observed. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1994;89:846–866. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Hoog SL, Ascroft RC, Krebs WB. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;44:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J, Hogan JW, Marcus BH. Principal stratification with predictors of compliance for randomized trials with 2 active treatments. Biostatistics. 2008;9:277–289. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer A, Zeger SL. On estimating efficacy from clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine. 1991;10:45–52. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansteelandt S, Goetghebeur E. Causal inference with generalized structural mean models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2003;65:817–835. [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens B, Tousset E, Rode R, Bertz R, Mayer S, Urquhart J. Successful projection of the time course of drug concentration in plasma during a 1-year period from electronically compiled dosing-time data used as input to individually parameterized pharmacokinetic models. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2005;45:461–467. doi: 10.1177/0091270004274433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens B, Urquhart J. Patient adherence to prescribed antimicrobial drug dosing regimens. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2005;52:616–627. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IR. Uses and limitations of randomization-based efficacy estimators. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2005;14:327–347. doi: 10.1191/0962280205sm406oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.