Abstract

γ-Radiation generates a variety of complex lesions in DNA, including the G[8,5-Me]T intrastrand cross-link in which C8 of guanine is covalently linked to the 5-methyl group of the 3′-thymine. We have investigated the toxicity and mutagenesis of this lesion by replicating a G[8,5-Me]T-modified plasmid in Escherichia coli with specific DNA polymerase knockouts. Viability was very low in a strain lacking pol II, pol IV, and pol V, the three SOS-inducible DNA polymerases, indicating that translesion synthesis is conducted primarily by these DNA polymerases. In the single-polymerase knockout strains, viability was the lowest in a pol V-deficient strain, which suggests that pol V is most efficient in bypassing this lesion. Most mutations were single-base substitutions or deletions, though a small population of mutants carrying two point mutations at or near the G[8,5-Me]T cross-link was also detected. Mutations in the progeny occurred at the cross-linked bases as well as at bases near the lesion site, but the mutational spectrum varied on the basis of the identity of the DNA polymerase that was knocked out. Mutation frequency was the lowest in a strain that lacked the three SOS DNA polymerases. We determined that pol V is required for most targeted G → T transversions, whereas pol IV is required for the targeted T deletions. Our results suggest that pol V and pol IV compete to carry out error-prone bypass of the G[8,5-Me]T cross-link.

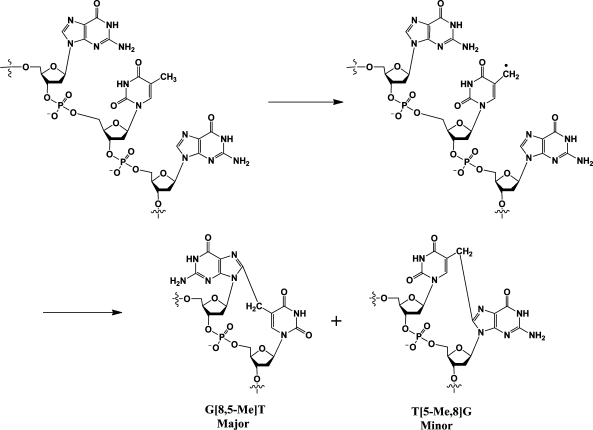

Ionizing radiation, including high-frequency UV, X-ray, and γ-ray radiation, causes numerous types of DNA damage, such as base modifications, strand breaks, protein−DNA cross-links, and abasic sites.1,2 In irradiated, aerated aqueous solutions, hydroxyl radical, which is also generated via normal cellular oxidation, is believed to be the major reactive species.3−5 Accordingly, the DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation is similar to oxidative stress, and these lesions have been implicated in aging and cancer. Biological effects of single-base damage by radiation or oxidation, such as 8-oxoguanine and thymine glycol, have been extensively studied. Only recently has the focus shifted to some of the more complex lesions. Tandem DNA lesions are formed at substantial frequency by ionizing radiation and metal-catalyzed H2O2 reactions (reviewed in ref (6)). Under anoxic conditions, the predominant double-base lesion is a species in which C8 of guanine is linked to the 5-methyl group of an adjacent 3′-thymine (G[8,5-Me]T) (Scheme 1).(7) Additional thymine-purine cross-links have been isolated from γ-irradiated DNA in an oxygen-free aqueous solution.(8) Wang and co-workers have detected a similar cross-link of guanine and cytosine in DNA.(9)

Scheme 1. Formation of G[8,5-Me]T and T[5-Me,8]G Cross-Links from a Thymine Radical.

The G[8,5-Me]T cross-link is subject to repair by the UvrABC nuclease, the nucleotide excision repair system in Escherichia coli.10,11 Using purified DNA polymerases, it was shown that the G[8,5-Me]T cross-link is a strong block of replication in vitro. Primer extension was terminated after incorporation of dAMP opposite the 3′-Thy by exo-free Klenow fragment and pol IV (dinB) of E. coli, whereas Taq polymerase was completely blocked at the nucleotide preceding the cross-link.(12) However, yeast and human DNA polymerase η (pol η) can bypass the G[8,5-Me]T cross-link, albeit with reduced efficiency relative to a control and with significantly reduced fidelity of nucleotide incorporation at the 5′-Gua.13−15 The incorporation of dAMP and dGMP is favored by yeast pol η over that of the correct nucleotide, dCMP, whereas the human enzyme incorporates the latter preferentially. In a prior study, we showed that G[8,5-Me]T is mutagenic in simian and human embryonic kidney cells, causing a wide variety of mutations at or near the cross-link, which included single- and multiple-base substitutions and small frameshifts.(14) A structurally similar lesion, G[8,5]C, is mutagenic in E. coli.(16) It induces mostly pol V-dependent G → T substitutions.(16)

In this work, we have investigated TLS of G[8,5-Me]T in several E. coli strains. We report here that pol IV and pol V compete to bypass this cross-link and that most targeted G → T transversions are caused by pol V, whereas pol IV is responsible for the targeted T deletions.

Materials and Methods

Materials

[γ-32P]ATP was from DuPont New England Nuclear (Boston, MA). EcoRV restriction endonuclease, T4 DNA ligase, T4 polynucleotide kinase, uracil DNA glycosylase, and exonuclease III were obtained from New England Bioloabs (Beverly, MA). Plasmid pMS2 was a gift from M. Moriya (State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY).

The following E. coli strains were used: AB1157 [F−thr-1 araC14 leuB6(Am) Δ(gpt-proA)62lacY1 tsx-33 supE44(AS) galK2(Oc) hisG4(Oc) rfbD1 mgl51 rpoS396(Am) rpsL31(Strr) kdgK51 xylA5 mtl-1 argE3(Oc) thi-1], pol II− (AB1157 but polBΔ1::Ω Sm-Sp), pol IV− (AB1157 but ΔdinBW2::cat), GW8017 (AB1157 but umuDC595::cat), and pol II−/pol IV−/pol V− (AB1157 but polBΔ1::Ω Sm-Sp dinB umuDC595::cat). All E. coli strains were provided by G. Walker (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA). Additional details of these strains have been provided in ref (17).

Methods

Synthesis and Characterization of Oligonucleotides

The G[8,5-Me]T-modified oligonucleotide 5′-GTGCG∧TGTTTGT-3′, containing the DNA sequence of p53 codons 272−275 in which the lesion was located in codon 273, was synthesized and characterized as reported previously.(10) Unmodified oligonucleotides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS analysis, which gave a molecular ion with a mass within 0.005% of the theoretical value, whereas adducted oligonucleotides were analyzed by ESI-MS in addition to digestion followed by HPLC analysis.

Construction and Characterization of pMS2 Vectors Containing a Single G[8,5-Me]T Cross-Link

The single-stranded pMS2 shuttle vector, which contains its only EcoRV site in a hairpin region, was prepared as described previously.(18) The pMS2 DNA (58 pmol, 100 μg) was digested with a large excess of EcoRV (300 pmol, 4.84 μg) for 1 h at 37 °C and then held at room temperature overnight. A 58-mer scaffold oligonucleotide was annealed overnight at 9 °C to form the gapped DNA. The control and lesion-containing oligonucleotides were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase, hybridized to the gapped pMS2 DNA, and ligated overnight at 16 °C. Unligated oligonucleotides were removed by being passed through a Centricon-100, and the DNA was precipitated with ethanol. The scaffold oligonucleotide was digested by being treated with uracil DNA glycosylase and exonuclease III; the proteins were extracted with a phenol/chloroform mixture, and the DNA was precipitated with ethanol. The final construct was dissolved in 1 mM Tris-HCl and 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8), and a portion was subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel to assess the amount of circular DNA.

Transformation in E. coli and Analyses of Progeny

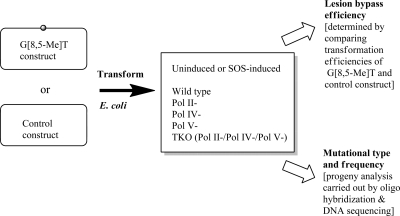

The control and G[8,5-Me]T construct were used to transform E. coli cells,(19) and transformants were analyzed by oligonucleotide hybridization.(14) Scheme 2 shows the general approach of replication of the constructs and analysis of the resultant progeny phagemid. Oligonucleotide probes containing the complementary 15-mer sequence were used for analysis. Two 14-mer left and right probes were used to select phagemids containing the correct insert, and transformants that did not hybridize with both the left and right probes were omitted. Any transformant that hybridized with the left and right probes but failed to hybridize with the 15-mer wild-type probe was subjected to DNA sequence analysis. Lesion bypass efficiency was calculated via comparison of the transformation efficiency of the G[8,5-Me]T construct with that of the control, whereas mutation frequency (MF) was calculated on the basis of hybridization and sequence analysis.

Scheme 2. General Approach to Replication of the Plasmid and Analysis of the Resultant Progeny Conducted in This Study.

Results

Viability of the G[8,5-Me]T Cross-Link in E. coli

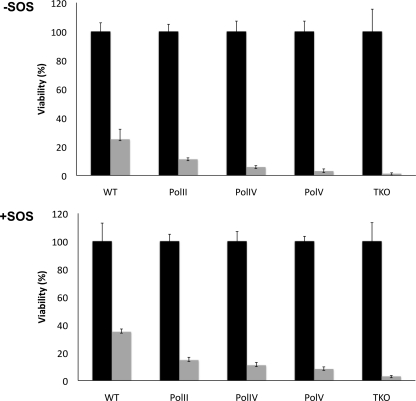

Compared to the control, the viability of the G[8,5-Me]T construct in wild-type cells was 25%, which increased to 35% in cells irradiated with UV to express the SOS functions (Figure 1). This suggests that G[8,5-Me]T is a replication-blocking lesion. Additional reduction in the viability of the lesion-containing construct was noted in the strains with a deficiency in pol II, pol IV, or pol V, the lesion-bypass polymerases in E. coli, but it was most pronounced in the pol V-deficient strain, where transformation efficiency was reduced to 3 and 8.3% without and with SOS, respectively (Figure 1). In a strain with knockouts of all three bypass polymerases, the corresponding efficiencies were 1.2 and 3.1%, respectively. This suggests that pol V is the major DNA polymerase for bypassing the G[8,5-Me]T lesion, but pol II and pol IV also play a role in the TLS, as suggested by a reduction in the level of survival in their absence.

Figure 1.

Viability of the G[8,5-Me]T construct in each strain without (top) and with SOS (bottom) determined in comparison to the control construct. The dark and gray bars represent transformation efficiencies of the control and G[8,5-Me]T construct, respectively. The data represent at least three independent experiments.

Mutagenesis of G[8,5-Me]T

As noted in mammalian cells,(14) in addition to targeted mutations, semitargeted mutations that occur at bases near the lesion site have been detected in all E. coli strains employed in this study. Though double-base mutations occurred at a low frequency, the major type of mutations by G[8,5-Me]T involved single-base substitutions or deletions. Table 1 summarizes the frequency of mutations in various E. coli strains. Mutations were analyzed for two independently constructed vectors. Although the types and frequencies of mutations were consistent in these transfections, they were combined for ease of analysis. Table S1 of the Supporting Information shows the frequency of each type of single mutation. It is important to point out that we also analyzed the progeny from a control construct, in which the MF in the 12-mer region was less than 1% in all strains of E. coli (data not shown).

Table 1. Mutations in E. Coli.

| polymerase knocked out | SOSa | expt no. | no. of colonies screened | single mutation (%) | double mutation (%) | total % MFb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| none | − | 1 | 151 | 17 | 3 | 12.0 |

| 2 | 165 | 16 | 2 | |||

| total | 316 | 33 (10.4) | 5 (1.6) | |||

| + | 1 | 91 | 21 | 3 | 27.2 | |

| 2 | 166 | 43 | 3 | |||

| total | 257 | 64 (24.9) | 6 (2.3) | |||

| pol V | − | 1 | 155 | 14 | 3 | 11.6 |

| 2 | 121 | 12 | 3 | |||

| total | 276 | 26 (9.4) | 6 (2.2) | |||

| + | 1 | 89 | 14 | 2 | 16.6 | |

| 2 | 128 | 18 | 2 | |||

| total | 217 | 32 (14.7) | 4 (1.8) | |||

| pol IV | − | 1 | 132 | 21 | 2 | 16.5 |

| 2 | 110 | 14 | 3 | |||

| total | 242 | 35 (14.5) | 5 (2.1) | |||

| + | 1 | 63 | 12 | 2 | 24.2 | |

| 2 | 135 | 25 | 9 | |||

| total | 198 | 37 (18.7) | 11 (5.6) | |||

| pol II | − | 1 | 133 | 16 | 4 | 15.4 |

| 2 | 101 | 13 | 3 | |||

| total | 234 | 29 (12.4) | 7 (3.0) | |||

| + | 1 | 57 | 7 | 2 | 29.0 | |

| 2 | 176 | 39 | 14 | |||

| 3 | 125 | 31 | 11 | |||

| total | 358 | 77 (21.5) | 27 (7.5) | |||

| pol II, pol IV, and pol V | − | 1 | 87 | 3 | 2 | 5.5 |

| 2 | 78 | 2 | 2 | |||

| total | 165 | 5 (3.0) | 4 (2.4) | |||

| + | 1 | 73 | 3 | 1 | 6.4 | |

| 2 | 67 | 5 | 0 | |||

| total | 140 | 8 (5.7) | 1 (0.7) |

SOS was induced with 20 J/m2 UV irradiation.

For each strain, the MF of the control construct was <1% (data not shown).

Role of SOS Polymerases in G[8,5-Me]T Mutagenesis

The fact that the bypass polymerases pol II, pol IV, and pol V caused most mutations in the progeny from the G[8,5-Me]T construct was confirmed in the strain that lacked these three DNA polymerases. In this triple-knockout (TKO) strain, in the absence of SOS, MF dropped from 12.0% in the wild type to 5.5% (Table 1). With SOS, MF decreased from 27.2% in the wild type to 6.4% in TKO cells (Table 1). By contrast, without SOS, MF remained approximately the same (12.0% vs 11.6%) in the pol V-deficient strain and was increased in pol II-deficient (15.4%) and pol IV-deficient (16.5%) strains. Upon induction of SOS, the total MF was slightly higher in pol II-deficient (29.0%) and a little lower in pol IV-deficient (24.2%) strains relative to the wild type (27.2%), whereas it was markedly lower in a pol V-deficient (16.6%) strain (Table 1). This is not unexpected, because pol V is the dominant error-prone TLS polymerase in SOS-induced E. coli.20−23 Therefore, in the pol V-deficient strain, upon induction of SOS, the MF was appreciably lower compared to the values for all other strains.

Marked Change in the Types of Mutations in Strains with pol IV or V Knockouts

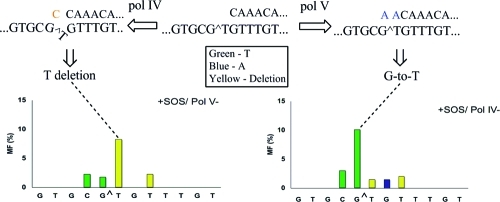

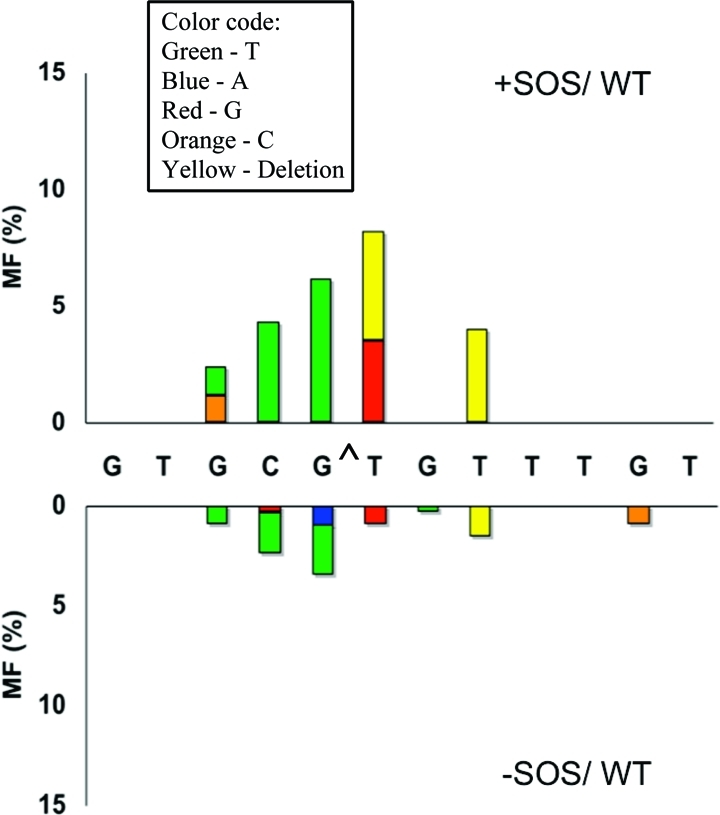

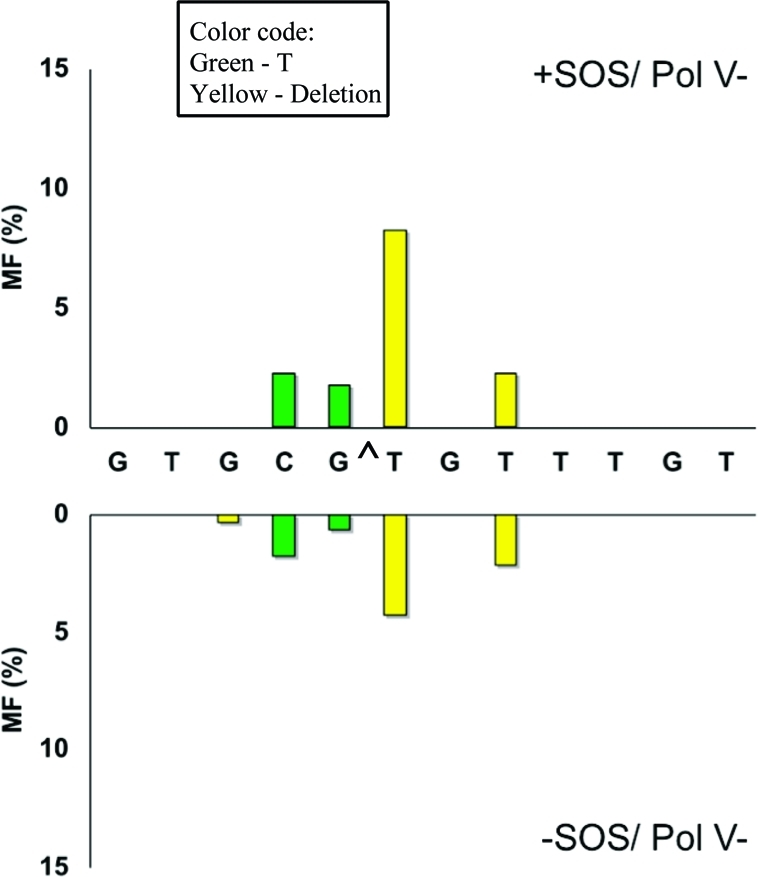

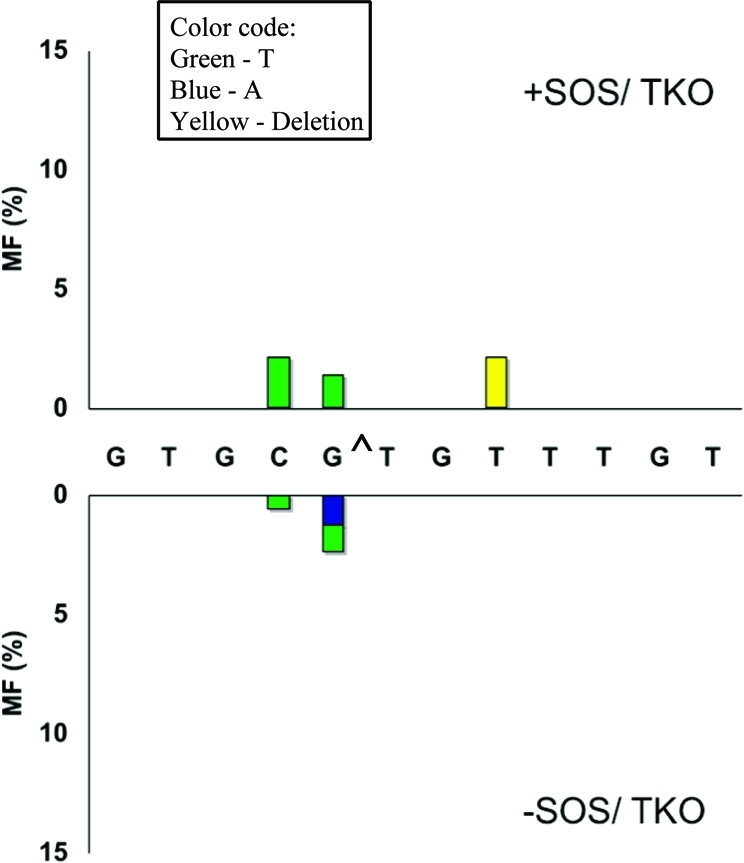

Particularly significant was the change in the mutational spectrum in the pol V- and pol IV-deficient strains relative to the wild type. Without SOS, targeted G → T transversions occurred at a 2.5% frequency in wild-type E. coli (Figure 2), which decreased to 0.7% in the pol V-deficient strain (Figure 3) and increased to 8.3% in the pol IV-deficient strain (Figure 4). With SOS, likewise, 6.2% targeted G → T transversion in the wild type (Figure 2) decreased to 1.8% in the pol V-deficient strain (Figure 3) and increased to 10.1% in the pol IV-deficient strain (Figure 4). This suggests that most targeted G → T transversion was induced by pol V. Similarly, targeted T deletion was absent in the uninduced wild-type strain (Figure 2) and was detected at 1.2% frequency in the pol IV-deficient strain (Figure 4), but it occurred at a 4.3% frequency in the pol V-deficient strain (Figure 3). The corresponding MFs in SOS-induced E. coli were 4.7% in the wild type (Figure 2), 1.5% in the pol IV-deficient strain (Figure 4), and 8.3% in the pol V-deficient strain (Figure 3). This suggests that pol IV was responsible for most targeted T deletions. Taken together, these data also indicate a competition between pol IV and pol V in TLS of G[8,5-Me]T, when both polymerases are active. Each plays a much more dominant role in the absence of the other.

Figure 2.

Types and frequencies of single-base substitution or deletion induced by G[8,5-Me]T with (top) and without (bottom) SOS in wild-type (AB1157) cells. The following colors are used: green for T, blue for A, red for G, orange for C, and yellow for a one-base deletion. Deletion of T from the run of three T residues is arbitrarily shown at the T closest to the lesion.

Figure 3.

Same as in Figure 2 for pol V-deficient cells.

Figure 4.

Same as in Figure 2 for pol IV-deficient cells.

Role of pol II and Other Polymerases

It is interesting to note that the deletion of T from a run of three T residues occurred at an approximately similar frequency in all strains, with the exception of SOS-induced pol II, where it was undetectable. We suspect that this deletion was induced even by the high-fidelity DNA polymerases. The C → T mutation at the C immediately 5′ to G[8,5-Me]T was also detected at comparable frequencies in all strains, suggesting that this mutation was induced by various DNA polymerases. However, the role of pol II in TLS of G[8,5-Me]T is uncertain. pol II has been suggested to be a major editor of pol III-mediated replication errors.(24) There was clearly a change in the mutational specificity in this strain compared to the wild type, and the most pronounced effect was on the frequency of one-base deletions (Figure 5). If the double mutations are included, one-base deletions occurred at an approximately 50% frequency in the pol II-deficient strains, with or without SOS. Even though it was less frequent than in the strain lacking pol V that is well-known for its ability to interact with DinB to inhibit the −1 frameshift activity,(25) it is conceivable that pol II plays a role in reducing the one-base deletions as well. This is unexpected in view of pol II's ability to conduct TLS of both full-length and looped out structures that are up to three nucleotides shorter than the template strand.(26) Also, in contrast to our result, pol II was found to be responsible for the frameshift mutagenesis pathway of the C8-dG adduct of AAF at the NarI site, whereas pol V bypasses the adduct in an error-free manner.(27) Despite pol II's ability to continue DNA synthesis of looped out structures, it was suggested that if the sequence is not as GC-rich as the NarI site, it is possible that the template and primer would realign without causing frameshift.(26) This distinction further underscores the importance of the lesion structure and DNA sequence context in error-prone and error-free TLS.

Figure 5.

Same as in Figure 2 for pol II-deficient cells.

In the TKO strain, MF decreased significantly (Table 1), and the only types of mutations observed were low levels of targeted G → T and 5′-C → T transversions and deletion of a T from the run of three T residues (Figure 6). It is likely that pol III is responsible for these mutations, though a role of pol I cannot be ruled out. A comparison of the mutations in the wild-type strain versus the various knockout strains indicates that targeted T → G transversion (1.0 and 3.5% without and with SOS, respectively) occurred only when all three bypass polymerases were present (Figure 2). One explanation of this is participation of all three TLS polymerases, at least occasionally, in bypass of G[8,5-Me]T, although the mechanism for such a process has not yet been established.

Figure 6.

Same as in Figure 2 for TKO (pol II-, pol IV-, and pol V-deficient) cells.

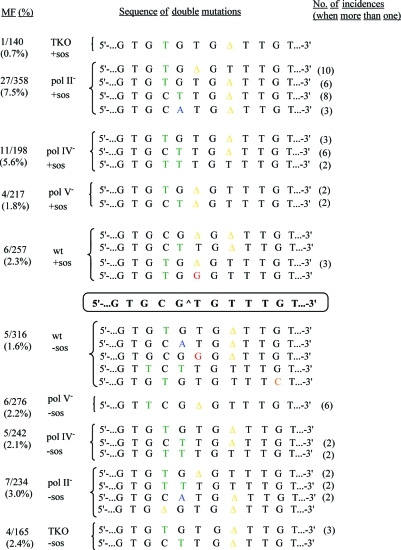

Double Mutations

A major fraction of the double mutations includes deletion of either the cross-linked T or a T from the run of three thymines, plus a base substitution nearby (Figure 7). In fact, of all the double mutations in various strains, 54% contained the deletion of a T from the run of three T residues, whereas 36% contained a deletion of the cross-linked T. Two mutations in a short stretch of DNA are statistically rare, and a significant frequency of double mutations, as noted in this study (Figure 7), raises the function played by the lesion and the DNA polymerase that has conducted TLS. Two mutations in the proximity of each other also raise the question of whether both errors are made by the same DNA polymerase. At least two different scenarios can be considered. In the first scenario, both are made by the same error-prone DNA polymerase. This would be the case in which both mutations are at or 5′ to the cross-link, which happened in 43% of the double mutations. In the second scenario, the first one is made by the processive DNA polymerase, pol III, and the second mutation occurs after a bypass polymerase is recruited. This was observed in 56% of the double mutations, and the majority of these involved a deletion of T from the run of three T residues. So, one can postulate that pol III makes a slippage error in the run of three T residues and stops at or before the cross-link, when a TLS polymerase is recruited. The newly recruited polymerase makes another error. When examined in SOS-induced strains, the frequency of double mutations was high (5.6%) in the pol IV-deficient strain and even higher (7.5%) in the pol II-deficient strain, whereas it was appreciably lower in the pol V-deficient and wild-type strains (1.8 and 2.3%, respectively). The targeted T deletion was particularly prevalent in pol II-deficient and pol V-deficient strains, while it was rare in the pol IV-deficient strain. So, pol IV could have been responsible for the double mutations that included targeted T deletions, which was noted for the single-point mutations.

Figure 7.

List of double mutations in wild-type, pol V-, pol IV-, and pol II-deficient, and TKO strains without (bottom) and with (top) SOS. MF (%) and the number of incidences are also shown.

Discussion

Previous studies showed that G[8,5-Me]T is strongly mutagenic in simian and human embryonic kidney cells.(14) In both mammalian cell lines, targeted as well as semitargeted mutations up to two bases 5′ and three bases 3′ to the cross-link have been detected. The lesion-induced mutations in this study in E. coli exhibited an analogous pattern. The mutational signature of G[8,5-Me]T is significantly different from that of G[8,5]C, the only other similar lesion studied in E. coli, which exhibited pol V-dependent targeted mutations.(16) It is worth mentioning that another tandem lesion, the thymine-thymine 6-4 photoproduct, causes mutations at and near the lesion site in mammalian cells,(28) but in E. coli, it induces only targeted mutations.(29) The mechanism of semitargeted mutations is not well-understood, but misaligned template−primer structures with the correct nucleotide inserted opposite the damaged base have been postulated to lead to semitargeted mutations.(30) The fact that low-fidelity DNA polymerases can make errors not only at the lesion site but also at bases near it has been shown for G[8,5-Me]T bypass by pol η from yeast and human.(15) The sequence context also may play a role in causing the semitargeted mutations, but investigation of other types of DNA damage in the sequence context employed in our study showed only a low level of mutations near the lesion site (e.g., ref (31)).

Of the five DNA polymerases in E. coli,22,32,33 the primary replicative polymerase is pol III, and its catalytic subunit is encoded by dnaE. pol I, encoded by polA, is involved in processing Okazaki fragments and in gap filling during excision repair.(34) The other three DNA polymerases are induced at a much higher level of expression by SOS and are involved in TLS.22,33 pol II, a B-family DNA polymerase encoded by polB, has proofreading 3′-exonuclease activity and is an accurate DNA polymerase, but its function still remains unclear.(35) By contrast, the other two SOS-inducible DNA polymerases of the Y-family, pol IV and pol V, encoded by dinB and umuDC, respectively, lack proofreading exonuclease activity.22,36 The Y-family polymerases have large active sites, allowing them to accommodate damaged DNA easily.(22) These low-fidelity DNA polymerases bypass many replication blocking lesions, and in many cases, they do it at an appreciably high rate of error.(36) The basal levels of DNA polymerases II, IV, and V are approximately 40, 250, and 15 copies, which increase to 280, 2500, and 200, respectively, when SOS-induced.37−39 The viability data of G[8,5-Me]T indicated that bypass of this cross-link requires the inducible DNA polymerases, pol II, pol IV, and pol V, as the level of survival dropped to 1−3% in the absence of these proteins. When a single DNA polymerase was knocked out, the absence of pol V had the most pronounced effect, suggesting that pol V is most efficient in bypassing the G[8,5-Me]T cross-link.

The pattern of mutagenesis in the polymerase knockout strains was helpful in identifying the polymerases responsible for two specific mutations. It is apparent that most targeted G → T transversions and T deletions were caused by pol V and pol IV, respectively. pol V has been shown to incorporate dAMP preferentially opposite several guanine lesions,(17) as we have noted here. The propensity of pol IV to induce one-base deletion is also well documented,(40) and UmuD and RecA act in concert to modulate this activity.(25) Nevertheless, it is conceivable that insertion opposite the lesion and extension of the damaged base pair are conducted by two different DNA polymerases. Multiple two-polymerase mechanisms for TLS in eukaryotes have been postulated.41,42 In E. coli, on the other hand, a polymerase “tool belt” model for switching pol III with pol IV at a stalled replication fork, where both polymerases bind simultaneously to the β-clamp, has been proposed.(43) However, the involvement of more than one TLS polymerase working in succession to bypass a lesion has not yet been shown in E. coli. Moreover, DinB can catalyze both insertion and extension with high efficiency,(44) whereas pol V is considered the major SOS TLS polymerase.22,33,45

It is interesting that pol IV does not appear to be responsible for deletions of T from the run of three T residues. Targeted T deletion was absent, however, in the absence of SOS in the wild-type strain, which seems to suggest a dominant role of pol V even without SOS. With SOS, there appears to be a competition, but more error-prone TLS was conducted by pol V, as evidenced by the viability data and a higher rate of G → T transversion relative to targeted T deletions. Only when pol V was impaired did the pol IV-dependent T deletions become dominant. The C → T transversion immediately 5′ to the G[8,5-Me]T cross-link was induced even in the absence of all three bypass polymerases, and its frequency was not significantly altered in any of these strains. The replicative DNA polymerase, pol III, may have been responsible for these mutations, which implies that at least occasionally pol III can bypass G[8,5-Me]T, even though a role for pol I cannot be ruled out. On the basis of the mutational spectrum in TKO, either pol III or pol I may also be considered responsible for a small fraction of the targeted G → T transversions. The fact that the G[8,5-Me]T cross-link lesion was responsible for these mutations was indicated by their absence in the progeny from the control construct.

It is interesting that in an earlier in vitro study primer extension was terminated after incorporation of dAMP opposite the 3′-T of G[8,5-Me]T by pol IV.(12) In contrast, the data of our in vivo study showed that pol IV is quite efficient in bypassing the cross-link. The discrepancy between the in vitro experiments using purified DNA polymerase and the current in vivo study may stem from the critical role played by the accessory proteins in vivo. pol V requires several accessory proteins such as RecA and single-stranded binding protein. Goodman and co-workers have shown that the presence of pol III's processivity β,γ-complex increases the DNA synthesis efficiency of pol IV by 3000-fold.(45) The in vitro experiment in which pol IV was unable to bypass G[8,5-Me]T did not include the β,γ-complex.

In conclusion, G[8,5-Me]T bypass was conducted mainly by pol II, pol IV, and pol V, the TLS polymerases in E. coli. Both targeted and semitargeted mutations were detected. Using polymerase knockout strains, we established that the majority of mutations were induced by the TLS polymerases. Most targeted G → T events were caused by error-prone replication by pol V, whereas pol IV was responsible for the targeted T deletions. On the basis of the difference in the mutational signatures of the two polymerases, it is likely that pol IV and pol V compete for TLS of G[8,5-Me]T.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- G[8,5-Me]T or G∧T

guanine-thymine intrastrand cross-link in which C8 of guanine is covalently bonded to the methyl carbon of the 3′-thymine

- pol

DNA polymerase

- pol η

DNA polymerase η

- MF

mutation frequency

- TLS

translesion synthesis

- TKO

triple-knockout E. coli strain (i.e., of pol II, pol IV, and pol V).

Supporting Information Available

Compilation of the single-point mutations induced by G[8,5-Me]T in various E. coli strains with (top) and without (bottom) SOS (Table S1). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant ES013324.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Finkel T.; Holbrook N. J. (2000) Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408, 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. D.; Dizdaroglu M.; Cooke M. S. (2004) Oxidative DNA damage and disease: Induction, repair and significance. Mutat. Res. 567, 1–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu M. (1992) Measurement of radiation-induced damage to DNA at the molecular level. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 61, 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu M.; Jaruga P.; Birincioglu M.; Rodriguez H. (2002) Free radical-induced damage to DNA: Mechanisms and measurement. Free Radical Biol. Med. 32, 1102–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J.; Berger M.; Douki T.; Ravanat J. L. (1997) Oxidative damage to DNA: Formation, measurement, and biological significance. Rev. Physiol., Biochem., Pharmacol. 131, 1–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box H. C.; Dawidzik J. B.; Budzinski E. E. (2001) Free radical-induced double lesions in DNA. Free Radical Biol. Med. 31, 856–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box H. C.; Budzinski E. E.; Dawidzik J. D.; Wallace J. C.; Evans M. S.; Gobey J. S. (1996) Radiation-induced formation of a crosslink between base moieties of deoxyguanosine and thymidine in deoxygenated solutions of d(CpGpTpA). Radiat. Res. 145, 641–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellon S.; Ravanat J. L.; Gasparutto D.; Cadet J. (2002) Cross-linked thymine-purine base tandem lesions: Synthesis, characterization, and measurement in γ-irradiated isolated DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 15, 598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C.; Wang Y. (2005) Thermodynamic and in vitro replication studies of an intrastrand G[8−5]C cross-link lesion. Biochemistry 44, 8883–8889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Colis L. C.; Basu A. K.; Zou Y. (2005) Recognition and incision of γ-radiation-induced cross-linked guanine-thymine tandem lesion G[8,5-Me]T by UvrABC nuclease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 18, 1339–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C.; Zhang Q.; Yang Z.; Wang Y.; Zou Y. (2006) Recognition and incision of oxidative intrastrand cross-link lesions by UvrABC nuclease. Biochemistry 45, 10739–10746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellon S.; Gasparutto D.; Saint-Pierre C.; Cadet J. (2006) Guanine-thymine intrastrand cross-linked lesion containing oligonucleotides: From chemical synthesis to in vitro enzymatic replication. Org. Biomol. Chem. 4, 3831–3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; Hong H.; Cao H.; Wang Y. (2007) In vivo formation and in vitro replication of a guanine-thymine intrastrand cross-link lesion. Biochemistry 46, 12757–12763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colis L. C.; Raychaudhury P.; Basu A. K. (2008) Mutational specificity of γ-radiation-induced guanine-thymine and thymine-guanine intrastrand cross-links in mammalian cells and translesion synthesis past the guanine-thymine lesion by human DNA polymerase η. Biochemistry 47, 8070–8079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhury P.; Basu A. K. (2010) Replication Past the γ-Radiation-Induced Guanine-Thymine Cross-Link G[8,5-Me]T by Human and Yeast DNA Polymerase η. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 101495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H.; Cao H.; Wang Y. (2007) Formation and genotoxicity of a guanine-cytosine intrastrand cross-link lesion in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 7118–7127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeley W. L.; Delaney S.; Alekseyev Y. O.; Jarosz D. F.; Delaney J. C.; Walker G. C.; Essigmann J. M. (2007) DNA polymerase V allows bypass of toxic guanine oxidation products in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12741–12748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya M. (1993) Single-stranded shuttle phagemid for mutagenesis studies in mammalian cells: 8-Oxoguanine in DNA induces targeted G.C → T.A transversions in simian kidney cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 1122–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilario P.; Yan S.; Hingerty B. E.; Broyde S.; Basu A. K. (2002) Comparative mutagenesis of the C8-guanine adducts of 1-nitropyrene and 1,6- and 1,8-dinitropyrene in a CpG repeat sequence. A slipped frameshift intermediate model for dinucleotide deletion. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45068–45074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maor-Shoshani A.; Reuven N. B.; Tomer G.; Livneh Z. (2000) Highly mutagenic replication by DNA polymerase V (UmuC) provides a mechanistic basis for SOS untargeted mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 565–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timms A. R.; Bridges B. A. (2002) DNA polymerase V-dependent mutator activity in an SOS-induced Escherichia coli strain with a temperature-sensitive DNA polymerase III. Mutat. Res. 499, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M. F. (2002) Error-prone repair DNA polymerases in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 17–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q.; Karata K.; Woodgate R.; Cox M. M.; Goodman M. F. (2009) The active form of DNA polymerase V is UmuD′(2)C-RecA-ATP. Nature 460, 359–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banach-Orlowska M.; Fijalkowska I. J.; Schaaper R. M.; Jonczyk P. (2005) DNA polymerase II as a fidelity factor in chromosomal DNA synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 58, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy V. G.; Jarosz D. F.; Simon S. M.; Abyzov A.; Ilyin V.; Walker G. C. (2007) UmuD and RecA directly modulate the mutagenic potential of the Y family DNA polymerase DinB. Mol. Cell 28, 1058–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Yang W. (2009) Structural insight into translesion synthesis by DNA Pol II. Cell 139, 1279–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs R. P.; Fujii S. (2007) Translesion synthesis in Escherichia coli: Lessons from the NarI mutation hot spot. DNA Repair 6, 1032–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentil A.; Le Page F.; Margot A.; Lawrence C. W.; Borden A.; Sarasin A. (1996) Mutagenicity of a unique thymine-thymine dimer or thymine-thymine pyrimidine pyrimidone (6−4) photoproduct in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 1837–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeClerc J. E.; Borden A.; Lawrence C. W. (1991) The thymine-thymine pyrimidine-pyrimidone(6−4) ultraviolet light photoproduct is highly mutagenic and specifically induces 3′ thymine-to-cytosine transitions in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 9685–9689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechkoblit O.; Kolbanovskiy A.; Malinina L.; Geacintov N. E.; Broyde S.; Patel D. J. (2010) Mechanism of error-free and semitargeted mutagenic bypass of an aromatic amine lesion by Y-family polymerase Dpo4. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 379–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt D. L.; Utzat C. D.; Hilario P.; Basu A. K. (2007) Mutagenicity of the 1-nitropyrene-DNA adduct N-(deoxyguanosin-8-yl)-1-aminopyrene in mammalian cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 20, 1658–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori H.; Friedberg E. C.; Fuchs R. P.; Goodman M. F.; Hanaoka F.; Hinkle D.; Kunkel T. A.; Lawrence C. W.; Livneh Z.; Nohmi T.; Prakash L.; Prakash S.; Todo T.; Walker G. C.; Wang Z.; Woodgate R. (2001) The Y-family of DNA polymerases. Mol. Cell 8, 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuning P. J.; Simon S. M.; Godoy V. G.; Jarosz D. F.; Walker G. C. (2006) Characterization of Escherichia coli translesion synthesis polymerases and their accessory factors. Methods Enzymol. 408, 318–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin M. C.; Wang J.; Steitz T. A. (2001) Structure of the replicating complex of a pol α family DNA polymerase. Cell 105, 657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan S.; Woodgate R.; Goodman M. F. (1999) A phenotype for enigmatic DNA polymerase II: A pivotal role for pol II in replication restart in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 9224–9229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohmi T. (2006) Environmental stress and lesion-bypass DNA polymerases. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60, 231–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate R.; Ennis D. G. (1991) Levels of chromosomally encoded Umu proteins and requirements for in vivo UmuD cleavage. Mol. Gen. Genet. 229, 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z.; Goodman M. F. (1997) The Escherichia coli polB locus is identical to dinA, the structural gene for DNA polymerase II. Characterization of Pol II purified from a polB mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 8611–8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. R.; Matsui K.; Yamada M.; Gruz P.; Nohmi T. (2001) Roles of chromosomal and episomal dinB genes encoding DNA pol IV in targeted and untargeted mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J.; Gruz P.; Kim S. R.; Yamada M.; Matsui K.; Fuchs R. P.; Nohmi T. (1999) The dinB gene encodes a novel E. coli DNA polymerase, DNA pol IV, involved in mutagenesis. Mol. Cell 4, 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shachar S.; Ziv O.; Avkin S.; Adar S.; Wittschieben J.; Reissner T.; Chaney S.; Friedberg E. C.; Wang Z.; Carell T.; Geacintov N.; Livneh Z. (2009) Two-polymerase mechanisms dictate error-free and error-prone translesion DNA synthesis in mammals. EMBO J. 28, 383–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livneh Z.; Ziv O.; Shachar S. (2010) Multiple two-polymerase mechanisms in mammalian translesion DNA synthesis. Cell Cycle 9, 729–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indiani C.; McInerney P.; Georgescu R.; Goodman M. F.; O’Donnell M. (2005) A sliding-clamp toolbelt binds high- and low-fidelity DNA polymerases simultaneously. Mol. Cell 19, 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz D. F.; Cohen S. E.; Delaney J. C.; Essigmann J. M.; Walker G. C. (2009) A DinB variant reveals diverse physiological consequences of incomplete TLS extension by a Y-family DNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21137–21142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M.; Pham P.; Shen X.; Taylor J. S.; O’Donnell M.; Woodgate R.; Goodman M. F. (2000) Roles of E. coli DNA polymerases IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature 404, 1014–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.