Abstract

P2X ion channels have been functionally characterized from a range of eukaryotes. Although these receptors can be broadly classified into fast and slow desensitizing, the molecular mechanisms underlying current desensitization are not fully understood. Here, we describe the characterization of a P2X receptor from the cattle tick Boophilus microplus (BmP2X) displaying extremely slow current kinetics, little desensitization during ATP application, and marked rundown in current amplitude between sequential responses. ATP (EC50, 67.1 μM) evoked concentration-dependent currents at BmP2X that were antagonized by suramin (IC50, 4.8 μM) and potentiated by the antiparasitic drug amitraz. Ivermectin did not potentiate BmP2X currents, but the mutation M362L conferred ivermectin sensitivity. To investigate the mechanisms underlying slow desensitization we generated intracellular domain chimeras between BmP2X and the rapidly desensitizing P2X receptor from Hypsibius dujardini. Exchange of N or C termini between these fast- and slow-desensitizing receptors altered the rate of current desensitization toward that of the donor channel. Truncation of the BmP2X C terminus identified the penultimate residue (Arg413) as important for slow desensitization. Removal of positive charge at this position in the mutant R413A resulted in significantly faster desensitization, which was further accentuated by the negatively charged substitution R413D. R413A and R413D, however, still displayed current rundown to sequential ATP application. Mutation to a positive charge (R413K) reconstituted the wild-type phenotype. This study identifies a new determinant of P2X desensitization where positive charge at the end of the C terminal regulates current flow and further demonstrates that rundown and desensitization are governed by distinct mechanisms.

Introduction

P2X receptors are extracellular ATP-gated ion channels that facilitate the ionotropic component of purinergic signaling (Surprenant and North, 2009). These channels form as homomeric or heteromeric trimers (Nicke et al., 1998; Barrera et al., 2005) with each monomer consisting of intracellular amino and carboxyl termini, two transmembrane domains, and a large extracellular region containing five disulfide bonds (Clyne et al., 2002; Ennion and Evans, 2002a) and the agonist binding site (Roberts et al., 2006). The determination of the crystal structure of zebrafish P2X4 at 3.1-Å resolution (Kawate et al., 2009) has allowed previous biochemical and mutagenic studies to be interpreted in a structural context (Browne et al., 2010; Young, 2010) and has provided the basis for the commencement of a rudimentary understanding of molecular mechanisms governing aspects of channel function such as ion permeation, channel gating, and agonist/antagonist binding. The zebrafish P2X4 structural model, however, does not include the intracellular N- and C-terminal domains, because these were largely removed to aid crystallization (Kawate et al., 2009). It is clear from previous studies that these domains play important roles in regulating P2X channel function, particularly desensitization, which manifests itself in two distinct forms. The first, often referred to as “rundown,” is a decline in current amplitude in sequential responses to repeated applications of ATP and has been observed in P2X1, P2X3, P2X4, and P2X7 receptors. The second is a decline in current during the continued presence of agonist and is an integral part of the “time course” of an individual response. To avoid confusion, the former will subsequently be referred to as rundown and the latter simply as desensitization. Desensitization of ATP-evoked currents in P2X receptors varies between different subtypes, and receptors can be broadly classified into those that desensitize very rapidly during the continued presence of agonist, such as P2X1, P2X3, and HdP2X (Bavan et al., 2009), those that display moderate (several seconds) rates of desensitization, including P2X4, P2X5, and most other known invertebrate P2X channels, and those that desensitize slowly such as mammalian P2X2 and P2X7. The molecular mechanisms controlling desensitization are poorly understood and likely multifactorial involving movement of intracellular, transmembrane, and extracellular domains and possibly interactions with other proteins or intracellular messengers (Stojilkovic et al., 2005; Roberts et al., 2006).

Involvement of the transmembrane domains in P2X receptor desensitization was first demonstrated by chimeric P2X1-P2X2 receptors (Werner et al., 1996). Mutation of extracellular domain residues can also profoundly alter current kinetics, for example, mutation of human P2X1 Lys68, a key residue in the ATP binding site, significantly slows the rate of desensitization (Ennion et al., 2000). Furthermore, chimeric P2X2-P2X3 channels swapping parts of the extracellular domain indicate that the N-terminal half of this domain influences the stability of the desensitized conformation state (Zemkova et al., 2004). The intracellular N-terminal domain also plays a prominent role in regulating desensitization. This region contains a consensus protein kinase C site that is conserved in all known P2X receptors from Dictyostelium discoideum to human. Disruption of this site by mutagenesis leads to an increased rate of desensitization in P2X2 (Boué-Grabot et al., 2000) and the already fast-desensitizing P2X1 receptor (Ennion and Evans, 2002b). A desensitizing P2X2 splice variant (P2X2b) lacking 69 C-terminal amino acids first demonstrated that the intracellular C-terminal domain can also regulate desensitization (Brändle et al., 1997; Simon et al., 1997), and subsequent mutagenic studies narrowed the functional motif involved to a six-amino acid region located near the second transmembrane domain (Koshimizu et al., 1998). The juxtamembrane C-terminal region of P2X4 has also been shown to play an important role in desensitization with an aromatic moiety at position 374 and an amino rather than a guanidino group at position 373 being essential for prolonged P2X4 currents (Fountain and North, 2006). Furthermore, exchange of the C-terminal domains in P2X2 and P2X3 receptors results in faster desensitization in P2X2 and slower desensitization in P2X3 (Paukert et al., 2001).

In this study, we describe a novel invertebrate P2X receptor cloned from the cattle tick Boophilus microplus (BmP2X). This receptor displays extremely slow desensitization properties, which we use in chimeric and mutagenic studies to identify a new example by which the C-terminal domain can govern P2X receptor desensitization during ATP application by virtue of positive charge at the penultimate position. Our results also further indicate that desensitization during the continued presence of agonist and rundown of currents between sequential applications are distinct processes regulated by different mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Identification and Cloning of a B. microplus P2X Receptor.

BLAST searches of the GenBank EST database identified partial 5′ (accession no. CK189412) and 3′ (accession no. CK189413) sequences from an EST clone (BEACR91) (Guerrero et al., 2005) that showed homology to the vertebrate P2X receptor family. The insert of this clone was sequenced and found to contain an open reading frame of 1242 bp. This coding sequence was subsequently subcloned by PCR (Table 1; primer pair 1) into a pcDNA3-based Xenopus laevis oocyte expression vector (Agboh et al., 2004) to introduce a mammalian Kozak sequence around the start codon. The inclusion of this sequence did not alter the coding sequence of the original clone and had previously been found to aid the expression of nonvertebrate P2X receptors in X. laevis oocytes (Agboh et al., 2004). The cloned insert was fully sequenced on both strands using vector- and insert-specific primers (Automated ABI Sequencing Service, University of Leicester, Leicester, U.K.).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers

Primer pair 1, amplification of the BmP2X wild-type sequence to introduce a mammalian Kozak sequence. Primer pairs 2–9, BmP2X-HdP2X chimera generation. Region refers to the amino acid positions encoded in the resulting PCR product. EarI endonuclease recognition sites incorporated into primers are in bold.

| Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) | Region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BmP2X | GCCGCCACCATGGGCTTGAACTGCG | GCATACACTTGAGTGCTCG | 1–414 |

| 2 | BmP2X N-TM2 | GCCGCCACCATGGGCTTGAAC | AACTCTTCACAGCAGGCAGTTAAGAACAACAAG | 1–378 |

| 3 | HdP2X N-TM2 | GCCGCCACCATGACGAATTTCACTAATACG | AACTCTTCACTTCAGGAAGTCCGTTAAAAAGTC | 1–371 |

| 4 | BmP2X TM1-C | AACTCTTCACGTATCGGCGTGCTCAACAGGCTC | AGTGCTCGTTAGCATGCTCC | 28–414 |

| 5 | HdP2X TM1-C | AACTCTTCAAAGTTGGGCGCCATCAATCGGAC | GGAGTTTTGGTAGCGCACAG | 40–480 |

| 6 | BmP2X N | GCCGCCACCATGGGCTTGAAC | AACTCTTCACTTTTTGTTGCCGATGTGGAC | 1–28 |

| 7 | HdP2X N | GCCGCCACCATGACGAATTTCACTAATACG | AACTCTTCAACGAGTGCTGTAGACCTTGAC | 1–40 |

| 8 | BmP2X C | AACTCTTCAAAGCGTCGTGATCTGTACAAG | AGTGCTCGTTAGCATGCTCC | 378–414 |

| 9 | HdP2X C | AACTCTTCAAAGCGTCGTGATCTGTACAAG | GGAGTTTTGGTAGCGCACAG | 371–480 |

N, amino termini; C, carboxyl termini.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Point mutations in the BmP2X plasmid were introduced using the QuikChange Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Methionine at position 362 was mutated to leucine, tyrosine 411 was mutated to alanine, and arginine 413 was mutated to lysine, aspartic acid, and alanine. A series of truncation mutants were also generated by introducing a premature stop codon (denoted as Δ) at positions 388, 394, 400, 408, 410, 412, 413, and 414. Introduction of the correct mutation and the absence of spontaneous mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing on both strands.

Generation of BmP2X-HdP2X Chimeras.

Six chimeric constructs were generated in which one or both of the amino and carboxyl intracellular domains of the slow-desensitizing BmP2X receptor and the fast-desensitizing HdP2X receptor were interchanged (see Fig. 3). The positions of transmembrane domains TM1 and TM2 in HdP2X and BmP2X were predicted using the programs TMPred (Hofmann and Stoffel, 1993) and TopPredII (Claros and von Heijne, 1994). Because the two prediction programs varied slightly in assignment of start and end positions for TM domains, the splice residue for cloning was chosen slightly away from the outermost prediction to avoid the possibility of disrupting transmembrane sequence. The N-terminal regions interchanged consisted of residues 1 to 28 and 1 to 40 for BmP2X and HdP2X, respectively, whereas the C-terminal regions consisted of residues 378 to 414 for BmP2X and 371 to 480 for HdP2X. Intracellular domains were spliced to residue 29 (N terminus) and/or residue 377 (C terminus) in BmP2X and residues 41 and 370 in HdP2X. Chimeras were generated using the technique of seamless cloning. PCR primer pairs (Table 1), one of which incorporated an EarI restriction site, an enzyme that cuts outside of its recognition sequence, were designed to allow amplification of the two component parts of the chimera, which were subsequently ligated together after EarI digestion to produce a seamless join at the desired position. Both wild-type BmP2X and HdP2X sequences contain a single internal EarI site, and this was disrupted by site-directed mutagenesis to leave the coding sequence unchanged before commencing chimera generation. For chimeras A and C the acceptor wild-type P2X plasmid was first used in a PCR to amplify the sequence from the N terminus to the end of TM2. The reverse primer incorporates an EarI restriction site so that the overhang remaining on the bottom strand after EarI digestion of the PCR product corresponds to the inverse complement of the codon at the desired splice position. The C-terminal region from the donor P2X plasmid was amplified in a separate PCR where the forward primer incorporated an EarI site that would leave a top strand overhang corresponding to the codon of the splice position. The two EarI-digested PCR products were subsequently ligated together and blunt end-cloned into expression vector. A similar strategy in reverse was used to generate N-terminal exchange chimeras B and D. Chimeras containing a double intracellular domain exchange (E and F) were generated using chimeras B and D, respectively, as the acceptor sequence. PCRs consisted of 10 ng of plasmid template, 12.5 pmol of each primer, 0.25 mM nucleotides, 1× HF buffer (Stratagene), and 1.25 units of PfuUltra DNA polymerase (Stratagene). Thermal cycling consisted of 95°C for 2 min followed by 20 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, 10 s. All chimeric constructs were verified by sequencing on both strands.

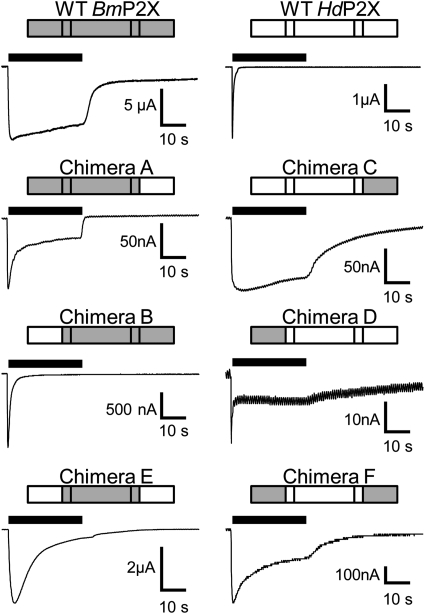

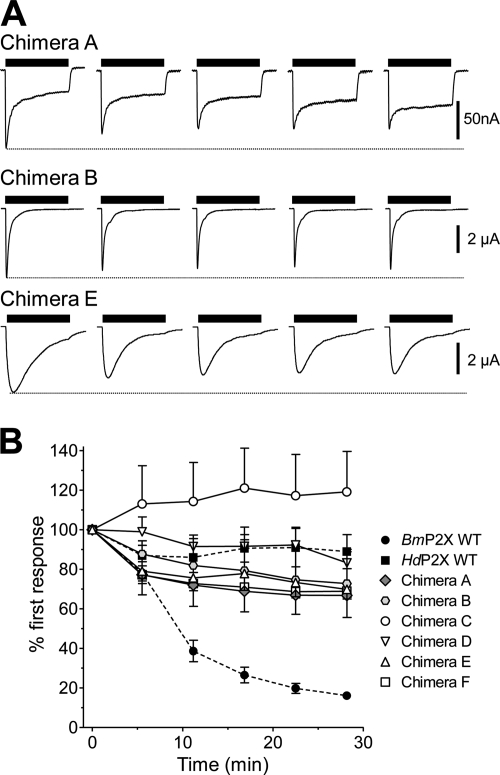

Fig. 3.

Changes in desensitization properties after exchange of intracellular domains in chimeric channels. Examples of membrane currents in response to a 30-s application of 1 mM ATP (black bars) are shown for wild-type and intracellular domain chimeras between BmP2X (gray) and HdP2X (white) channels.

Electrophysiological Recordings.

Sense strand cRNA was generated from linearized P2X plasmids using a T7 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Manually defolliculated stage V X. laevis oocytes were injected with 50 ng of cRNA and stored at 18°C in ND96 buffer (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6) before recording 3 to 7 days later. Two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings were made from P2X-expressing X. laevis oocytes at room temperature using an Axoclamp 900A amplifier with a Digidata 1440A data acquisition system and pClamp 10 acquisition software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Oocytes were clamped at −60 mV, and recording solution consisted of ND96 with BaCl2 (1.8 mM) substituting CaCl2 to prevent the activation of endogenous oocyte calcium-activated chloride channels. Microelectrodes were filled with 3 M KCl and had a resistance of 0.2 MΩ. ATP was applied from a nearby U-tube perfusion system, whereas suramin (Bayer, Berkshire, UK), ivermectin, and amitraz were bath-perfused and also present at the appropriate concentration in the U-tube application of ATP. To control for the rundown in responses displayed by BmP2X between sequential applications of ATP, concentration response data were normalized to a bracketing concentration of 100 μM ATP applied before and subsequent to the test concentration with a 5-min recovery period between applications. Current properties were analyzed using Clampfit 10.2 software (Molecular Devices). Desensitization in wild-type, chimeric, and mutant channels was quantified using the parameters of I20 (percentage of peak current amplitude after 20 s of ATP application) and T.10% (time taken for peak current to decay by 10%). T.10% was chosen rather than the more conventional T.50% (time for current to decay by 50%) because wild-type and some mutant channel currents did not decay by 50% even after prolonged (up to 6 min tested) application of agonist. Rundown was quantified by recording peak amplitudes after sequential ATP applications with a 5-min recovery period between the end of one application and the start of the next. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Differences between means were tested using one-way analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis) with Dunn's multiple comparison post test (Prism; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Concentration response data were fitted with the equation Y = ((X)nH · M)/((X)nH + (EC50)nH), where Y is response, X is agonist concentration, nH is the Hill coefficient, M is maximum response, and EC50 is the concentration of agonist evoking 50% of the maximum response. pEC50 is the −log10 of the EC50 value.

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals, nucleotides and drugs were obtained from Sigma Chemical (Poole, Dorset, UK).

Results

Sequence Analysis of BmP2X.

The EST clone BEACR91 was found to contain a full-length open reading frame (submitted to GenBank as accession no. HQ333533) encoding 414 amino acids with homology to the human P2X1–7 receptor family ranging from 30.6% (P2X7) to 43.6% identity (P2X4). Prediction of membrane topology using TMPred (Hofmann and Stoffel, 1993) and TopPredII (Claros and von Heijne, 1994) suggests a typical P2X topology with intracellular carboxyl and amino termini, two transmembrane domains, and a large extracellular loop. Typical features of vertebrate P2X receptors such as 10 extracellular cysteine residues, a consensus protein kinase C phosphorylation site in the amino-terminal domain, and positive and aromatic residues thought to be involved in ATP binding are also conserved in BmP2X.

BmP2X Is an ATP-Gated Ion Channel.

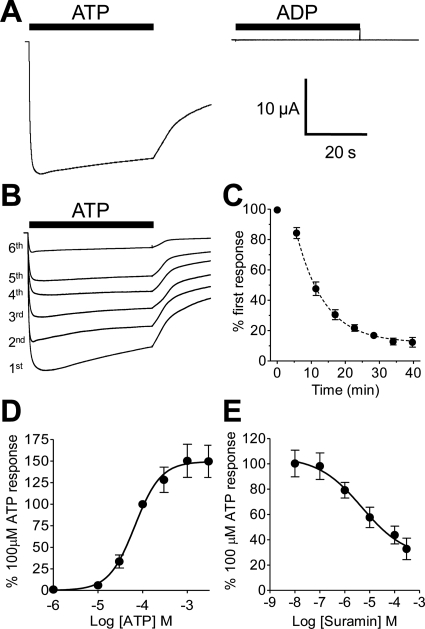

ATP evoked large (∼15 μA) inward currents at recombinant BmP2X receptors expressed in X. laevis oocytes (Fig. 1A). These currents displayed unusually slow kinetics, taking 4.5 ± 0.7 s to reach peak and 17.0 ± 2.4 s to decay by 10% during the continued presence of agonist (n = 24). Even after prolonged application of agonist (up to 6 min) currents did not decay by 50%, making measurement of T.50% (time for current to decay by 50%) impractical because of changes in holding current required to clamp oocytes at −60 mV over prolonged periods of large membrane currents. Despite this low level of current desensitization during the continued presence of agonist, a marked rundown in current amplitude was observed between sequential applications of agonist with current amplitudes ∼12% of their original amplitude after eight sequential 40-s applications of 100 μM ATP 5 min apart (Fig. 1C). The decline in amplitude between the second and eighth applications was best-fit with a single exponential (τ, 8.2 ± 1.3 min; n = 24 oocytes). The first ATP application was omitted from this fit because oocytes did not have a prior 5-min recovery period at this time point. ATP had an EC50 of 67.1 μM with a Hill slope of 1.5 ± 0.03 (Fig. 1D). Adenosine, ADP, and UTP (tested at 1 mM) did not evoke currents at BmP2X. The general P2 receptor antagonist suramin inhibited ATP-evoked BmP2X currents with an IC50 of 4.8 μM (Fig. 1E). However, there was a suramin-resistant component to the BmP2X current that persisted at the highest concentration of suramin tested (300 μM).

Fig. 1.

BmP2X is a slowly desensitizing ATP-gated ion channel. Membrane currents were recorded by two-electrode voltage clamp in X. laevis oocytes expressing BmP2X receptors. A, examples of current traces in response to a 40-s application (black bars) of 1 mM ATP (left) or 1 mM ADP (right) are shown. B, consecutive responses from the same oocyte demonstrated a marked rundown in current amplitude with sequential 40-s applications of 100 μM ATP and a 5-min recovery period between the end of one application and the start of the next. C, mean data expressed as percentage of peak current amplitude of the first response for consecutive ATP applications as described in B (n = 24 oocytes) are shown. Dotted line shows a single exponential fit (excluding time point zero); τ, 8.2 min. D, concentration response curve for ATP in BmP2X-expressing oocytes is shown. Mean currents (± S.E.M) were normalized to responses given by 100 μM ATP; EC50, 67.1 μM (n = 7 oocytes). E, inhibition curve for mean responses to 100 μM ATP in the presence of different concentrations of suramin (IC50, 4.8 μM) (n = 7) is shown.

Wild-Type BmP2X Is Not Potentiated by Ivermectin but the Mutation M362L Confers Ivermectin Sensitivity.

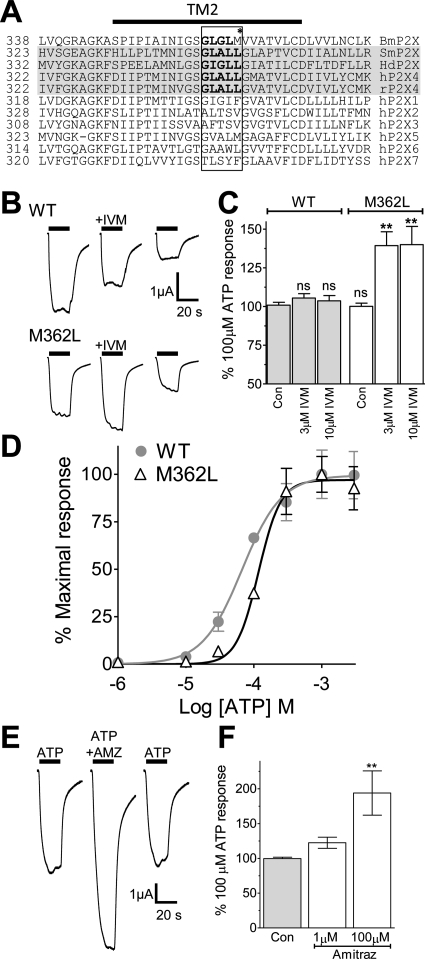

The macrocyclic lactone ivermectin is a broad-spectrum antiparasitic agent used in human and veterinary medicine and had previously been shown to potentiate ATP-activated currents in human and rat P2X4 (Khakh et al., 1999; Priel and Silberberg, 2004), the SmP2X receptor from the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni (Agboh et al., 2004), and the HdP2X receptor from the tardigrade Hypsibius dujardini (Bavan et al., 2009). Because ivermectin is an effective treatment against B. microplus infestation in cattle (Cramer et al., 1988a,b), we were interested to determine whether BmP2X currents were similarly affected by ivermectin. Wild-type BmP2X receptors show a marked rundown in current amplitude between sequential ATP applications, which may mask any subtle effects of ivermectin. We therefore normalized 100 μM ATP responses in the presence of either 3 or 10 μM ivermectin to ATP responses 5 min before and 5 min after the test application. Ivermectin, however, had no significant effect on ATP-evoked currents at both concentrations tested (Fig. 2, B and C). Ivermectin acts as an allosteric modulator of P2X4 by interacting with the transmembrane regions (Silberberg et al., 2007), and several predominantly nonpolar residues lying on the same side of their respective helices have been identified that when mutated to cysteine disrupt ivermectin sensitivity (Jelínkova et al., 2008). From alignment of P2X transmembrane sequences, the sequence motif (G(L/I)(G/A)LL) in TM2 is seen to be present only in those P2X channels known to be ivermectin-sensitive (SmP2X, HdP2X, human P2X4, and rat P2X4) (Fig. 2A). The first and last residues in this motif had previously been shown to be essential for ivermectin sensitivity (Jelínkova et al., 2008). Because the wild-type BmP2X receptor differed from this motif by only one amino acid (Met362), we mutated this residue to leucine and tested for ivermectin sensitivity. Ivermectin potentiated ATP-evoked currents at the M362L mutant by ∼40% at both 3 and 10 μM (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2, B and C). The M362L mutation had no effect on current rundown between sequential agonist application (data not shown) but was slightly less sensitive to ATP with an EC50 of 117.5 μM (Fig. 2D). The triazapentadiene compound amitraz is also widely used to treat tick infestation in cattle, and we therefore also tested the effects of this compound on BmP2X. Amitraz alone (100 μM) did not evoke membrane currents in X. laevis oocytes expressing BmP2X receptors (data not shown). However, when amitraz was coapplied with 100 μM ATP, membrane currents were potentiated by 22.5 ± 8 and 93.9 ± 31% at 1 and 100 μM amitraz, respectively (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

The mutation M362L confers ivermectin sensitivity in BMP2X. A, amino acid alignment of the region surrounding TM2 in BmP2X, SmP2X, (Agboh et al., 2004), HdP2X (Bavan et al., 2009), rat P2X4 (rP2X4), and human P2X1–7 (hP2X1–7) receptors is shown. Ivermectin-sensitive receptors are highlighted in gray. A TM2 motif (G(L/I)(G/A)LL) present only in those receptors sensitive to ivermectin is highlighted in bold. B, examples of two-electrode voltage clamp recordings from wild-type and M362L BmP2X-expressing X. laevis oocytes are shown. ATP (100 μM)-evoked currents were recorded from the same cell in the presence and absence of 3 μM ivermectin (+IVM) (applications indicated by bars). A 5-min recovery period was allowed between applications, and ivermectin was bath-perfused in the 5 min preceding the second recording and was present in the ATP application. C, mean data for ATP (100 μM) responses in the presence and absence of ivermectin (3 or 10 μM) as described in B are shown. Ivermectin responses were normalized to the mean of the bracketing ATP responses 5 min before and 5 min after the ivermectin response. **, P < 0.01 and ns, P > 0.05 in comparison with the wild-type control response (n = 10–15). D, ATP concentration response curve for M362L (n = 8) is shown. The wild-type BmP2X curve (gray) is also shown for comparison. E, examples of wild-type BmP2X current traces to sequential applications (5 min apart) of ATP (100 μM) in the presence and absence of 100 μM amitraz (+AMZ) are shown. F, mean data (n = 12–15) for ATP (100 μM) responses in the presence and absence of amitraz (1 or 10 μM) (protocol as described in B) are shown.

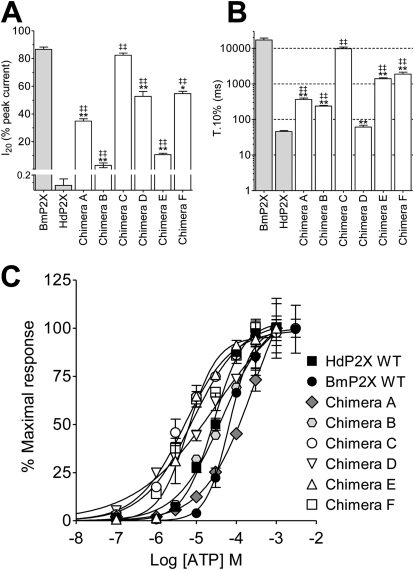

The Contribution of the Intracellular Domains in Determining Desensitization Properties of BmP2X and HdP2X Receptors.

The slow-desensitization properties of ATP-evoked currents in BmP2X receptors are in marked contrast to the exceptionally fast desensitization displayed by the HdP2X receptor (Bavan et al., 2009). To assess the contribution of the intracellular domains in determining these markedly contrasting desensitization kinetics, a series of six chimeric channels were generated by exchanging intracellular N and C termini between BmP2X and HdP2X (Fig. 3). All six chimeras produced functional ATP-gated channels (Fig. 3). However, maximal current amplitudes were significantly lower than the respective wild-type channels with some chimeras (A, C, and D) producing currents less than 100 nA (Table 2). Nevertheless, clear changes in desensitization properties were apparent, and these were quantified using the parameters of 10 to 90% rise time, I20, and T.10%. With the exception of chimera A, ATP was slightly more potent at chimeric channels compared with their respective wild type (Fig. 4C and Table 3). Marginal (<5-fold) shifts in ATP potency were observed for all chimeras, and in each case 1 mM ATP produced a maximal response. Chimera A, consisting of BmP2X with the C terminus replaced with that of HdP2X, displayed a rise time (269 ± 14 ms; n = 23) ∼3.5 times faster (P < 0.01) than wild-type BmP2X (Table 2). Chimera A currents initially desensitized rapidly with a mean T.10% of 364 ± 37ms followed by a much slower rate of desensitization reflected in an I20 value of 34.8 ± 1.7%. Likewise, replacement of the C terminus of HdP2X with that of BmP2X in chimera C also resulted in a change in current kinetics toward that of the C-terminal donor channel with rise time, I20 (Fig. 4A), and T.10% (Fig. 4B) values all significantly slower (P < 0.01) than HdP2X and similar to those of BmP2X (Table 2). Exchange of N-terminal domain regions in chimeras B and D also resulted in phenotypic changes in current kinetics toward those of the donor channel with chimera B becoming faster than BmP2X and chimera D becoming slower than HdP2X (Table 2). Despite the very small (∼22 nA) current amplitude displayed by chimera D, it was clear that, similar to chimera A, this channel also displayed an initial rapid phase of desensitization (T.10%, 61 ± 7 ms; n = 16) followed by a slower rate of desensitization that resulted in an I20 value of 52.7 ± 3.5%. Given the large shifts in desensitization properties resulting from exchange of a single intracellular N- or C-terminal domain, it was perhaps unexpected that the exchange of both intracellular termini together in chimeras E and F resulted in a less pronounced change compared with the single-domain swap chimeras. Nevertheless, chimera E displayed T.10% and I20 values that were significantly (P < 0.01) faster than wild-type BmP2X, and chimera F was significantly slower than wild-type HdP2X (Table 2 and Fig. 4, A and B).

TABLE 2.

Properties of ATP-evoked currents in wild-type, mutant, and chimeric P2X channels

Values are means ± S.E.M. n ≥ 15 for each channel.

| Channel | Peak Current | 10–90% Rise Time | T.10% | I20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nA | ms | % | ||

| WT BmP2X | −14,677 ± 882†† | 951 ± 129†† | 17,016 ± 2420†† | 86.6 ± 1.7†† |

| WT HdP2X | −1808 ± 141** | 65 ± 2** | 46 ± 3** | 0.1 ± 0.08** |

| Chimera A | −77 ± 6**†† | 269 ± 14**†† | 364 ± 37**†† | 34.8 ± 1.7**†† |

| Chimera B | −1282 ± 165** | 281 ± 8**†† | 237 ± 10**†† | 2.9 ± 0.2**†† |

| Chimera C | −63 ± 4**†† | 1730 ± 192†† | 10,020 ± 1391†† | 82.4 ± 1.5†† |

| Chimera D | −22 ± 1**†† | 195 ± 12** | 61 ± 7** | 52.7 ± 3.5**†† |

| Chimera E | −5441 ± 538 | 1072 ± 70†† | 1388 ± 92**†† | 10.6 ± 1.1**†† |

| Chimera F | −196 ± 12**†† | 482 ± 39†† | 1882 ± 249**†† | 54.7 ± 1.7*†† |

| Ser414Δ | −14,056 ± 628†† | 1515 ± 230†† | 16,244 ± 1374†† | 88.6 ± 1.6†† |

| Arg413Δ | −11,720 ± 883†† | 588 ± 75†† | 6469 ± 766**†† | 68.3 ± 3.3**†† |

| Leu412Δ | −8600 ± 1043**†† | 454 ± 39†† | 700 ± 41**†† | 5.1 ± 1.1**†† |

| Phe410Δ | −8670 ± 857**†† | 491 ± 31†† | 764 ± 41**†† | 8.4 ± 1.1**†† |

| Glu408Δ | −15,812 ± 1152†† | 358 ± 23**†† | 1118 ± 113**†† | 13.2 ± 1.7**†† |

| Lys400Δ | −7078 ± 864**†† | 276 ± 35**†† | 620 ± 77**†† | 9.8 ± 1.7**†† |

| Glu394Δ | −14,263 ± 1194†† | 328 ± 14**†† | 1337 ± 140**†† | 26.1 ± 2.6**†† |

| Tyr388Δ | NF | NF | NF | NF |

| Y411A | −14,379 ± 580†† | 731 ± 113†† | 16,207 ± 4615†† | 79.0 ± 3.8†† |

| R413K | −11,640 ± 1168†† | 1500 ± 313†† | 15,455 ± 3934†† | 84.5 ± 3.0†† |

| R413A | −7805 ± 1476**†† | 624 ± 91†† | 2964 ± 396**†† | 43.4 ± 5.7**†† |

| R413D | −7435 ± 871*†† | 275 ± 24**†† | 758 ± 50**†† | 40.0 ± 3.2**†† |

NF, nonfunctional.

P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01, significant difference from wild-type BmP2X.

P < 0.01, significant difference from wild-type HdP2X.

Fig. 4.

Quantification of current desensitization in X. laevis oocytes expressing wild-type and chimeric Bm-HdP2X channels is shown. A, I20 values for membrane currents in response to a 30-s application of 1 mM ATP (n = 15–25) are shown. B, T.10% values for the same traces as in A are shown (note log scale of y-axis). ** and ‡‡ denote a significant difference (P < 0.01) to wild-type BmP2X and HdP2X, respectively (*, P < 0.05). C, concentration response curves for wild-type and chimeric channels (see Table 3) are shown.

TABLE 3.

ATP concentration response data

| Channel | EC50 | pEC50 | Hill Slope |

|---|---|---|---|

| μM | |||

| WT BmP2X | 67.1 | 4.17 ± 0.03 | 1.5 ± 0.03 |

| BmP2X M362L | 117.5 | 3.93 ± 0.03 | 2.7 ± 0.03 |

| HdP2X | 25.5 | 4.59 ± 0.04 | 1.2 ± 0.01 |

| Chimera A | 100.2 | 4.00 ± 0.06 | 1.0 ± 0.12 |

| Chimera B | 34.8 | 4.46 ± 0.07 | 0.9 ± 0.11 |

| Chimera C | 5.2 | 5.29 ± 0.05 | 0.7 ± 0.06 |

| Chimera D | 12.1 | 4.92 ± 0.06 | 0.5 ± 0.04 |

| Chimera E | 7.2 | 5.14 ± 0.06 | 1.1 ± 0.13 |

| Chimera F | 6.9 | 5.16 ± 0.04 | 0.8 ± 0.05 |

Replacement of the Intracellular Domains Disrupts the Marked Current Rundown Displayed by BmP2X.

In contrast to BmP2X, which displayed a marked rundown in current amplitude between repeated applications of agonist (Fig. 1, B and C), HdP2X showed little rundown in current amplitude with a 5-min recovery period between sequential applications of agonist (Fig. 5B). We therefore investigated current rundown after six sequential applications of ATP, 5 min apart, in chimeras A to F to assess the potential roles of intracellular domains in determining these differing phenotypes. Similar to wild-type HdP2X, a small decrease in current amplitude between the first and second responses was observed in chimeras A, B, D, E, and F (Fig. 5). Subsequent applications, however, produced stable responses, and the amplitude of the second response was not significantly different from the sixth response (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5B). The amplitude of responses in chimera C similarly did not show rundown between sequential applications, and current amplitudes increased slightly during the course of the six applications.

Fig. 5.

Replacement of intracellular domains in BmP2X chimeras prevents the marked current rundown observed in WT BmP2X. A, examples of consecutive responses to a 30-s application of 1 mM ATP (black bars) with a 5-min recovery period between applications in X. laevis oocytes expressing chimeras consisting of a BmP2X core (chimeras A, B, and E) are shown. The marked rundown in current amplitude to sequential ATP applications displayed by wild-type BmP2X is abolished in these chimeras. B, mean peak current amplitudes to sequential application of ATP (1 mM, 5 min apart) in wild-type BmP2X and HdP2X (dashed lines) and chimeric channels (n = 5–7) are shown.

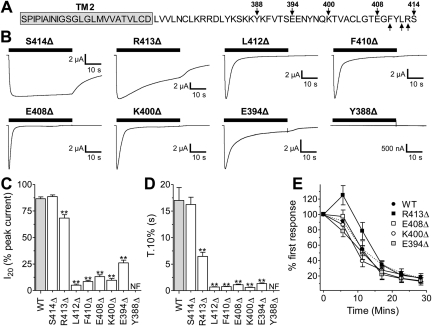

Truncation of the C Terminus Increases the Rate of BmP2X Desensitization but Does Not Prevent Current Rundown.

Replacement of the C-terminal domain in the fast-desensitizing HdP2X channel with that of the slowly desensitizing BmP2X (chimera C) was sufficient to convert HdP2X into a slowly desensitizing channel with T.10% decay time, 10 to 90% rise time, and I20 values not significantly different from BmP2X (Table 2). This suggests that the C-terminal domain plays a prominent role in determining the slow current desensitization properties of BmP2X. To investigate this further we created a series of truncation mutations by introducing premature stop codons in the C-terminal domain of BmP2X. As an initial screen, stop codons were introduced at positions 408, 400, 394, and 388. Truncation at the first three of these positions resulted in functional channels with peak amplitudes >7 μA, 10 to 90% rise time, and T.10% and I20 values significantly (P < 0.01) faster than the wild-type BmP2X channel (Table 2 and Fig. 6). The truncation Tyr388Δ, however, produced a nonfunctional channel. Removal of just the six terminal amino acids from the C-terminal domain by the mutation Glu408Δ was sufficient to produce marked speeding in the desensitization properties of the channel (Fig. 6). We therefore generated an additional four truncation mutants within this six-amino acid region to assess which residues were required for the slow-desensitization properties of the wild-type BmP2X channel. Removal of the terminal serine residue in the mutation Ser414Δ resulted in no significant change in current kinetics with 10 to 90% rise times and T.10% and I20 values all similar to wild type (Table 2 and Fig. 6, C and D). Truncation at position 413, removing the terminal arginine and serine residues, however, did result in a speeding of current desensitization with T.10% and I20 values significantly (P < 0.01) faster than wild type. This speeding in desensitization was more pronounced when truncations were made further upstream at positions 412 and 410, resulting in channels with very similar properties to the truncation mutants Lys400Δ and Glu408Δ. Similar to wild type, all functional truncation mutants displayed a rundown in peak current amplitude after sequential application of 1 mM ATP with a 5-min recovery period resulting in current amplitudes ∼12% of their original values after six sequential applications (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Truncation of the BmP2X C-terminal tail increases the rate of current desensitization. A, BmP2X C-terminal domain sequence indicating positions of truncation mutants (arrows) is shown. Predicted TM2 domain sequence is highlighted in gray. B, examples of current traces to a 40-s application of 1 mM ATP (black bars) recorded from X. laevis oocytes expressing BmP2X C-terminal truncation mutants are shown. C and D, mean I20 and T.10% values for truncation mutants (n = 12–18) are shown. ** denotes a significant difference to wild type (P < 0.01). NF in the case of Tyr388Δ denotes a nonfunctional channel. E, mean peak current amplitudes to sequential application of ATP (1 mM, 5 min apart) in WT BmP2X (dashed line) and truncation mutants (n = 7–9) are shown.

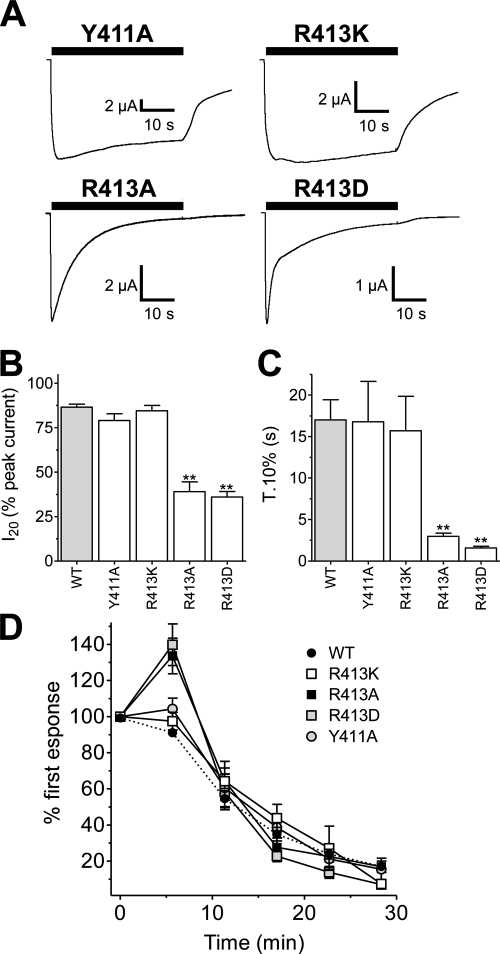

Positive Charge at Position 413 Is Required for the Slow Desensitization of BmP2X.

Truncations of the intracellular C-terminal domain identified the end of this region as being important in determining the slow-desensitization properties of BmP2X because truncations upstream of position 413 disrupted the slow-desensitizing phenotype. We therefore mutated Arg413 to alanine, aspartic acid, or lysine to determine whether charge at this position was an important factor, and we also mutated Tyr411 to alanine because this nearby residue partially met the criteria for a consensus tyrosine phosphorylation site. ATP-evoked currents in the Y411A mutant were not significantly different from those of the wild-type channel (Fig. 7 and Table 2), indicating that potential phosphorylation at this position does not play a role in determining the slow-desensitizing phenotype. However, mutation of arginine 413 to alanine, thereby neutralizing the positive charge at this position, resulted in a speeding of desensitization such that T.10% and I20 values were significantly (P < 0.01) faster than wild type. Converting the positive charge at this position to a negative charge further increased the initial rate of desensitization with mutant R413D displaying a T.10% approximately four times faster than R413A and ∼20 times faster than wild type. The current remaining after 20-s ATP application (I20), however, was very similar between the R413A and R413D with both mutants displaying approximately half the current of the wild-type channel at this time point (Table 2). Maintaining the positive charge at position 413 by mutation to lysine (mutant R413K) resulted in a wild-type phenotype with 10 to 90% rise time and T.10% and I20 values not significantly different from BmP2X (Fig. 7 and Table 2), demonstrating that it is positive charge rather than the arginine per se at this position that determines the slow-desensitization properties of BmP2X. Rundown after sequential ATP applications was still apparent in Arg413 and Y411A mutants with each, similar to wild type, displaying peak current amplitudes ∼15% of their original values after six sequential responses (Fig. 7D). The mutants R413A and R413D, however, initially showed an increase in current amplitude between the first and second responses before rundown occurred at a rate similar to wild type between the third and sixth responses (Fig. 7D). It is noteworthy that a similar phenomenon was also observed with the Arg413Δ truncation mutant (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 7.

Mutation of arginine 413 demonstrates that positive charge in this position is essential for the slow-desensitizing phenotype of wild-type BmP2X. A, examples of current traces recorded from X. laevis oocytes expressing Tyr411 and Arg413 mutant BmP2X channels are shown. Removal of positive charge in mutants R413A and R413D speeds the rate of current desensitization, whereas slow desensitization is restored in mutant R413K. B and C, mean I20 and T.10% values for truncation mutants (n = 8–15) are shown. ** denotes a significant difference to wild type (P < 0.01). D, mean peak current amplitudes to sequential application of ATP (1 mM, 5 min apart) in WT BmP2X (dashed line) and point mutants (n = 7–8) are shown.

Discussion

Functional evidence that BmP2X corresponds to an ATP-gated channel establishes the existence of P2X receptors in the phylum Arthropoda. This is of significance regarding our understanding of the evolution of purinergic signaling because P2X receptors are absent in the fully sequenced genomes of several other arthropods such as Anopheles gambiae, Drosophila melanogaster, and Apis mellifera, suggesting a selective loss of P2X receptors within this phylum has occurred in insects.

The ectoparasite B. microplus represents a significant problem to livestock production in tropical and subtropical regions through direct detrimental effects of blood feeding and also by the transmission of disease (Young et al., 1988). Our initial interest in BmP2X stemmed from the possibility that this channel could represent a target for the antiparasitic drug ivermectin. Although BmP2X proved to be ivermectin-insensitive (Fig. 2C), key residues within TM2 showed homology with ivermectin-sensitive P2X receptors (Fig. 2A). One obvious difference was BmP2X Met362, which is a leucine in ivermectin-sensitive P2X receptors. Because a BmP2X gene single-nucleotide polymorphism could have resulted in this difference we generated the mutant M362L. Leucine at position 362 conferred ivermectin sensitivity in BmP2X, confirming previous studies (Jelínkova et al., 2008) highlighting the importance of this residue in ivermectin binding. However, the effect of ivermectin on BmP2X M362L was relatively modest (∼40% potentiation), casting doubt on whether a potential single-nucleotide polymorphism at this position could be of relevance to the development of ivermectin resistance in B. microplus (Perez-Cogollo et al., 2010). The ectoparasiticide amitraz is also widely used to treat tick infestation and is thought to act via parasite muscle octopamine receptors (Chen et al., 2007). Amitraz is typically applied to cattle at a concentration of 0.025% (∼850 μM) (Eamens et al., 2001; Mekonnen, 2001). This concentration would be sufficient to affect BmP2X function because 100 μM amitraz approximately doubled ATP evoked currents (Fig. 2F). It is therefore possible that BmP2X potentiation is an additional target for the parasitacide action of amitraz, particularly in view of the fact that P2X receptors are known to play important roles in muscle contractility (Surprenant and North, 2009).

The extremely slow kinetics of BmP2X led us to use this receptor as a model to probe mechanisms of desensitization. Chimeras produced by swapping N- and C-terminal domains between the fast-desensitizing HdP2X and slow-desensitizing BmP2X were used to investigate the importance of intracellular domains in determining current desensitization and rundown. Although interpretation of these chimeric studies is complicated by difficulties in distinguishing between effects caused by introduction of a new domain and those resulting from removal of the replaced domain, the overall pattern that emerged was that both N and C termini play important roles in determining desensitization. However, the extent to which a particular domain exerts its effect depends on the context in which it is placed. For example, considering the two chimeras that resulted in the most complete fast-to-slow or slow-to-fast phenotype reversal (chimeras B and C), the N-terminal domain of the fast-desensitizing HdP2X seems to exert a dominant fast-desensitizing effect on the slow BmP2X C-terminal domain (chimera B). However, when the slow BmP2X C-terminal domain is placed in the context of the fast-desensitizing HdP2X (chimera C), it is the slow BmP2X C-terminal domain that dominates over the fast HdP2X N-terminal domain. A composite phenotype of fast- and slow-desensitizing components resulted when either the HdP2X C terminus was placed in the context of BmP2X or the BmP2X N terminus was placed in the context of HdP2X (chimeras A and D, respectively). Taken together, these findings suggest that although both terminal domains of both receptors can modulate desensitization, in HdP2X it is the N-terminal domain that is most important for fast desensitization, whereas in BmP2X it is the C-terminal domain that is most important for slow desensitization. When both N and C termini were exchanged together, a similar slow-to-fast (chimera E) and fast-to-slow (chimera F) reversal was observed. However, the effects of double N- and C-terminal exchange were not as pronounced as those in single exchanges, suggesting that, in addition to potentially interacting with each other, the intracellular domains may couple with other regions of the receptor, as has been proposed for P2X2 (He et al., 2002) and that these interactions are disrupted more by exchange of a single intracellular domain than by exchange of both domains together. Chimeras generated by exchange of transmembrane regions linked to N- or C-terminal domains between the fast-desensitizing P2X1 (or P2X3) and the slow-desensitizing P2X2 receptor previously demonstrated that transmembrane domains play an important role in desensitization (Werner et al., 1996). The Bm-HdP2X chimeras used in this current study, however, involved exchange of only intracellular domains and therefore demonstrate that both of these regions can modulate desensitization independently from their respective transmembrane sequence. This is also supported by the naturally occurring P2X2b (Brändle et al., 1997; Simon et al., 1997; Koshimizu et al., 1998) and mouse P2X2e (Koshimizu and Tsujimoto, 2006) splice variants, mutation of the protein kinase C site in the N-terminal domain (Boué-Grabot et al., 2000), mutation of a P2X4 C-terminal domain lysine residue (Fountain and North, 2006), and exchange of the C-terminal domains in P2X2 and P2X3 receptors (Paukert et al., 2001).

The intracellular C-terminal domains are highly variable in length between different P2X receptors and share little sequence similarity. The functional significance of this divergence is unclear but probably arises from the evolution of different regulatory mechanisms to control channel function. To further investigate the significance of the BmP2X C-terminal domain in regulating slow desensitization, we first generated a series of truncation mutants (Fig. 6). Similar to zebrafish P2X4 (Kawate et al., 2009), BmP2X channel function was quite tolerant to C-terminal truncation with all truncations up to and including Glu394 producing functional channels (Fig. 6). This is in contrast to human P2X4 where deletion of the terminal 15 amino acids prevented function (Fountain and North, 2006). No ATP-evoked currents were observed in the Tyr388Δ truncation, suggesting that the minimal C-terminal domain length required for BmP2X function lies between residues 388 and 394. All functional BmP2X truncations before the terminal serine at position 414 resulted in a speeding in the rate of desensitization (Fig. 6B), suggesting that the very end of the C-terminal domain is important in determining the slow-desensitization properties of BmP2X. Indeed, disruption of the positive charge at the penultimate residue (Arg413) in the mutants R413A and R413D significantly increased the speed of channel desensitization (Fig. 7A). The fact that substitution for lysine at this same position (R413K) resulted in a wild-type phenotype demonstrates that it is the positive charge at this position that is crucial for slow desensitization rather than arginine per se. Among human, rat, and mouse P2X1–7 and the known invertebrate P2X receptors, BmP2X is the only channel with an arginine at the penultimate position. A positively charged C-terminal lysine residue has also been shown to be important for slow desensitization in P2X4; however, in this case it is the amino group rather than the positive charge that is critical (Fountain and North, 2006).

In addition to desensitization during the continued presence of agonist, BmP2X responses displayed a marked rundown in current amplitude between sequential applications of agonist. The lack of rundown in the BmP2X-based chimeras A, B, and E suggests that, in addition to regulating desensitization during the continued presence of agonist, intracellular domains may play a role in the mechanism of rundown between sequential responses, possibly by influencing the rate of receptor internalization (Dutton et al., 2000) and trafficking (Bobanovic et al., 2002). However, the BmP2X N or C termini when added to the HdP2X core did not confer rundown, suggesting that the intracellular domains are not the sole determinants. Furthermore, chimeric channels generally had smaller current amplitudes than wild-type channels, making direct comparison of rundown difficult. C-terminal truncations (Fig. 6E) and Arg413 point mutants (Fig. 7D) did display peak current amplitudes that were comparable with wild-type BmP2X (Table 2). In these mutant channels rundown and desensitization seemed to be independent processes, because a marked increase in desensitization was not accompanied by a significant alteration in the rate of rundown after six sequential ATP applications. It was, however, interesting that truncation Arg413Δ and the point mutants R413A and R413D (but not R413K) initially showed an increase in current amplitude between first and second responses before rundown occurred at a rate similar to wild type (Figs. 6E and 7D). The reason for this is unclear, but given that Arg413 plays a key role in desensitization, it could suggest that although desensitization and rundown are largely governed by distinct mechanisms, positive charge at position 413 could also have a minor influence on rundown.

In summary, this study presents a new member of the P2X receptor family, BmP2X, and identifies a novel example by which P2X desensitization is regulated by positive charge at the end of the C terminus. BmP2X may also be of importance to the cattle industry either as a potential target for new antiparasitic agents or an epitope for vaccines against tick infestation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amina Bassou for technical assistance in the generation of truncation mutants and Manijeh Maleki-Dizaji for the preparation of X. laevis oocytes.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [Grant WT081601MA] and a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Studentship (to S.B.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://dmd.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/mol.110.070037.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- BmP2X

- P2X receptor from Boophilus microplus

- HdP2X

- P2X receptor from Hypsibius dujardini

- SmP2X

- P2X receptor from Schistosoma mansoni

- I20

- percentage of peak current amplitude after 20 s of ATP application

- T.10%

- time taken for peak current to decay by 10%

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- TM

- transmembrane

- WT

- wild type

- EST

- expressed sequence tag.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Ennion.

Conducted experiments: Bavan, Farmer, Singh, Guerrero, and Ennion.

Performed data analysis: Bavan, Farmer, Singh, and Ennion.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Straub, Guerrero, and Ennion.

References

- Agboh KC, Webb TE, Evans RJ, Ennion SJ. (2004) Functional characterization of a P2X receptor from Schistosoma mansoni. J Biol Chem 279:41650–41657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera NP, Ormond SJ, Henderson RM, Murrell-Lagnado RD, Edwardson JM. (2005) Atomic force microscopy imaging demonstrates that P2X2 receptors are trimers but that P2X6 receptor subunits do not oligomerize. J Biol Chem 280:10759–10765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavan S, Straub VA, Blaxter ML, Ennion SJ. (2009) A P2X receptor from the tardigrade species Hypsibius dujardini with fast kinetics and sensitivity to zinc and copper. BMC Evol Biol 9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobanovic LK, Royle SJ, Murrell-Lagnado RD. (2002) P2X receptor trafficking in neurons is subunit specific. J Neurosci 22:4814–4824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boué-Grabot E, Archambault V, Séguéla P. (2000) A protein kinase C site highly conserved in P2X subunits controls the desensitization kinetics of P2X2 ATP-gated channels. J Biol Chem 275:10190–10195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brändle U, Spielmanns P, Osteroth R, Sim J, Surprenant A, Buell G, Ruppersberg JP, Plinkert PK, Zenner HP, Glowatzki E. (1997) Desensitization of the P2X2 receptor controlled by alternative splicing. FEBS Lett 404:294–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne LE, Jiang LH, North RA. (2010) New structure enlivens interest in P2X receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 31:229–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, He H, Davey RB. (2007) Mutations in a putative octopamine receptor gene in amitraz-resistant cattle ticks. Vet Parasitol 148:379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claros MG, von Heijne G. (1994) TopPred II: an improved software for membrane protein structure predictions. Comput Appl Biosci 10:685–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne JD, Wang LF, Hume RI. (2002) Mutational analysis of the conserved cysteines of the rat P2X2 purinoceptor. J Neurosci 22:3873–3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer LG, Bridi AA, Amaral NK, Gross SJ. (1988a) Persistent activity of injectable ivermectin in the control of the cattle tick Boophilus microplus. Vet Rec 122:611–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer LG, Carvalho LA, Bridi AA, Amaral NK, Barrick RA. (1988b) Efficacy of topically applied ivermectin against Boophilus microplus (Canestrini, 1887) in cattle. Vet Parasitol 29:341–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton JL, Poronnik P, Li GH, Holding CA, Worthington RA, Vandenberg RJ, Cook DI, Barden JA, Bennett MR. (2000) P2X1 receptor membrane redistribution and down-regulation visualized by using receptor-coupled green fluorescent protein chimeras. Neuropharmacology 39:2054–2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eamens G, Spence S, Turner M. (2001) Survival of Mycobacterium avium subsp paratuberculosis in amitraz cattle dip fluid. Aust Vet J 79:703–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennion S, Hagan S, Evans RJ. (2000) The role of positively charged amino acids in ATP recognition by human P2X1 receptors. J Biol Chem 275:29361–29367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennion SJ, Evans RJ. (2002a) Conserved cysteine residues in the extracellular loop of the human P2X1 receptor form disulfide bonds and are involved in receptor trafficking to the cell surface. Mol Pharmacol 61:303–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennion SJ, Evans RJ. (2002b) P2X1 receptor subunit contribution to gating revealed by a dominant negative PKC mutant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 291:611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountain SJ, North RA. (2006) A C-terminal lysine that controls human P2X4 receptor desensitization. J Biol Chem 281:15044–15049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero FD, Miller RJ, Rousseau ME, Sunkara S, Quackenbush J, Lee Y, Nene V. (2005) BmiGI: a database of cDNAs expressed in Boophilus microplus, the tropical/southern cattle tick. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 35:585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He ML, Koshimizu TA, Tomić M, Stojilkovic SS. (2002) Purinergic P2X2 receptor desensitization depends on coupling between ectodomain and C-terminal domain. Mol Pharmacol 62:1187–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K, Stoffel W. (1993) TMbase: a database of membrane spanning proteins segments. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 374:166 [Google Scholar]

- Jelínkova I, Vávra V, Jindrichova M, Obsil T, Zemkova HW, Zemkova H, Stojilkovic SS. (2008) Identification of P2X4 receptor transmembrane residues contributing to channel gating and interaction with ivermectin. Pflugers Arch 456:939–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawate T, Michel JC, Birdsong WT, Gouaux E. (2009) Crystal structure of the ATP-gated P2X4 ion channel in the closed state. Nature 460:592–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Proctor WR, Dunwiddie TV, Labarca C, Lester HA. (1999) Allosteric control of gating and kinetics at P2X4 receptor channels. J Neurosci 19:7289–7299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshimizu T, Tomić M, Koshimizu M, Stojilkovic SS. (1998) Identification of amino acid residues contributing to desensitization of the P2X2 receptor channel. J Biol Chem 273:12853–12857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshimizu TA, Tsujimoto G. (2006) Functional role of spliced cytoplasmic tails in P2X2-receptor-mediated cellular signaling. J Pharmacol Sci 101:261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen S. (2001) In vivo evaluation of amitraz against ticks under field conditions in Ethiopia. J S Afr Vet Assoc 72:44–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicke A, Bäumert HG, Rettinger J, Eichele A, Lambrecht G, Mutschler E, Schmalzing G. (1998) P2X1 and P2X3 receptors form stable trimers: a novel structural motif of ligand-gated ion channels. EMBO J 17:3016–3028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paukert M, Osteroth R, Geisler HS, Brandle U, Glowatzki E, Ruppersberg JP, Gründer S. (2001) Inflammatory mediators potentiate ATP-gated channels through the P2X3 subunit. J Biol Chem 276:21077–21082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cogollo LC, Rodriguez-Vivas RI, Ramirez-Cruz GT, Rosado-Aguilar JA. (2010) Survey of Rhipicephalus microplus resistance to ivermectin at cattle farms with history of macrocyclic lactones use in Yucatan, Mexico. Vet Parasitol 172:109–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priel A, Silberberg SD. (2004) Mechanism of ivermectin facilitation of human P2X4 receptor channels. J Gen Physiol 123:281–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JA, Vial C, Digby HR, Agboh KC, Wen H, Atterbury-Thomas A, Evans RJ. (2006) Molecular properties of P2X receptors. Pflugers Arch 452:486–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg SD, Li M, Swartz KJ. (2007) Ivermectin Interaction with transmembrane helices reveals widespread rearrangements during opening of P2X receptor channels. Neuron 54:263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J, Kidd EJ, Smith FM, Chessell IP, Murrell-Lagnado R, Humphrey PP, Barnard EA. (1997) Localization and functional expression of splice variants of the P2X2 receptor. Mol Pharmacol 52:237–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojilkovic SS, Tomic M, He ML, Yan Z, Koshimizu TA, Zemkova H. (2005) Molecular dissection of purinergic P2X receptor channels. Ann NY Acad Sci 1048:116–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surprenant A, North RA. (2009) Signaling at purinergic P2X receptors. Annu Rev Physiol 71:333–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, Seward EP, Buell GN, North RA. (1996) Domains of P2X receptors involved in desensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:15485–15490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AS, Groocock CM, Kariuki DP. (1988) Integrated control of ticks and tick-borne diseases of cattle in Africa. Parasitology 96:403–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MT. (2010) P2X receptors: dawn of the post-structure era. Trends Biochem Sci 35:83–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemkova H, He ML, Koshimizu TA, Stojilkovic SS. (2004) Identification of ectodomain regions contributing to gating, deactivation, and resensitization of purinergic P2X receptors. J Neurosci 24:6968–6978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]