Abstract

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) plays an important role in hematopoietic differentiation, and constitutively active FLT3 mutant proteins contribute to the development of acute myeloid leukemia. Little is known about the protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) affecting the signaling activity of FLT3. To identify such PTP, myeloid cells expressing wild type FLT3 were infected with a panel of lentiviral pseudotypes carrying shRNA expression cassettes targeting different PTP. Out of 20 PTP tested, expressed in hematopoietic cells, or presumed to be involved in oncogenesis or tumor suppression, DEP-1 (PTPRJ) was identified as a PTP negatively regulating FLT3 phosphorylation and signaling. Stable 32D myeloid cell lines with strongly reduced DEP-1 levels showed site-selective hyperphosphorylation of FLT3. In particular, the sites pTyr-589, pTyr-591, and pTyr-842 involved in the FLT3 ligand (FL)-mediated activation of FLT3 were hyperphosphorylated the most. Similarly, acute depletion of DEP-1 in the human AML cell line THP-1 caused elevated FLT3 phosphorylation. Direct interaction of DEP-1 and FLT3 was demonstrated by “substrate trapping” experiments showing association of DEP-1 D1205A or C1239S mutant proteins with FLT3 by co-immunoprecipitation. Moreover, activated FLT3 could be dephosphorylated by recombinant DEP-1 in vitro. Enhanced FLT3 phosphorylation in DEP-1-depleted cells was accompanied by enhanced FLT3-dependent activation of ERK and cell proliferation. Stable overexpression of DEP-1 in 32D cells and transient overexpression with FLT3 in HEK293 cells resulted in reduction of FL-mediated FLT3 signaling activity. Furthermore, FL-stimulated colony formation of 32D cells expressing FLT3 in methylcellulose was induced in response to shRNA-mediated DEP-1 knockdown. This transforming effect of DEP-1 knockdown was consistent with a moderately increased activation of STAT5 upon FL stimulation but did not translate into myeloproliferative disease formation in the 32D-C3H/HeJ mouse model. The data indicate that DEP-1 is negatively regulating FLT3 signaling activity and that its loss may contribute to but is not sufficient for leukemogenic cell transformation.

Keywords: Phosphatase, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase, Signal Transduction, shRNA, siRNA

Introduction

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) is a class III receptor tyrosine kinase and plays a role in proliferation and differentiation of B-cell progenitors, myelomonocytic and dendritic cells, as well as in the maintenance of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells (reviewed in Refs. 1, 2). Recently, FLT3 has received much attention as an important oncoprotein. Mutations in FLT3 that lead to constitutive activation are among the most common molecular lesions found in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)2 (3–5). Prevalent mutations result in internal tandem duplications (ITD) of amino acid stretches in the juxtamembrane domain of FLT3 (6) and in the N-terminal region of the kinase domain (7, 8). FLT3-ITD is constitutively active, can transform myeloid cell lines in vitro (9), and can induce a myeloproliferative disease when retrovirally transduced into primary murine bone marrow cells (10). Wild type FLT3 and FLT3-ITD exhibit qualitative differences in signal transduction. The wild type receptor signals via the PI3K/AKT and the RAS/ERK pathways, whereas FLT3-ITD can activate additional pathways, notably phosphorylation of STAT5 (reviewed in Ref. 11). Altered signaling quality is at least partially mediated by retention of the constitutive active receptor in an intracellular compartment (12–14).

Phosphorylation of wild type FLT3 and AML-associated mutant FLT3 was recently analyzed using site-specific phosphotyrosine antibodies (15). Interestingly, the phosphorylation pattern of the different FLT3 variants showed quantitative and also qualitative differences. Although FLT3-ITD or mutations in the kinase domain resulted in ligand-independent FLT3 autophosphorylation and signaling activity, the wild type receptor is only autophosphorylated in response to stimulation with its cytokine FL.

Signaling of receptor tyrosine kinases is modulated by protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) (16), and aberrations in PTP function play a role in carcinogenesis (17). Some PTP, notably SHP-2, have been found to positively influence growth-stimulatory signaling pathways, and mutations leading to gain-of-function of these PTP can potentially be oncogenic. It has been demonstrated that SHP-2 directly interacts with FLT3 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner via phosphotyrosine 599. SHP-2 contributes to FL-mediated ERK activation and proliferation (18, 19), but it appears dispensable for cell transformation by the FLT3-ITD mutant receptor (18). Little is known about PTP, which negatively regulate FLT3. Loss of such PTP could potentially also contribute to transformation of AML cells. Initial studies demonstrated that co-expression of FLT3 with the PTP SHP-1, PTP1B, and PTP-PEST leads to FLT3 dephosphorylation, suggesting an inhibitory function of these PTP for FLT3 signaling (14).

To further elucidate the function of PTP in FLT3 signaling, we have analyzed a panel of relevant PTP by using shRNA-mediated down-regulation in myeloid 32D cells expressing wild type FLT3 as a model system. Stable down-regulation of the transmembrane PTP DEP-1/PTPRJ positively affected signaling of FLT3. In addition, we found that autophosphorylation of FLT3 as well as FL-stimulated cell proliferation were enhanced in response to DEP-1 depletion. Overexpression of DEP-1 inhibited FLT3 phosphorylation and signaling. Direct interaction studies using DEP-1 “trapping mutants” and dephosphorylation in vitro further supported that FLT3 is a bona fide substrate of DEP-1. Identification of DEP-1 as a negatively regulating PTP for FLT3 will enable analyzing a possible role in transformation of myeloid cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines, Antibodies, and Antisera

The IL-3-dependent murine myeloid cell line 32D clone 3 (32D) (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ), Braunschweig, Germany) was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with sodium pyruvate (5 mg/ml), 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), l-glutamine (2 mm), and 1 ng/ml IL-3 or conditioned medium obtained from murine IL-3 producing BPV cells (20). Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. 32D cells stably expressing murine FLT3 wild type were kindly provided by Drs. R. Grundler and J. Duyster (Technical University Munich, Germany). Recombinant human FL and murine IL-3 were purchased from PeproTech Ltd., London, UK. Human THP-1 cells (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) endogenously expressing wild type FLT3 were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS. HEK293 cells were cultivated in DMEM/F-12 medium (1:1) (Invitrogen), supplemented with stabilized glutamine and 10% FCS.

Anti-P-AKT (Ser-473) (193H12), anti-AKT (catalog no. 9272), anti-P-p44/42 MAPK (Tyr-202/Tyr-204), anti-P-STAT5 (Tyr-694, EPITOMICS catalog no. 1208-1), and anti-STAT5 (catalog no. 9310) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Frankfurt, Germany). Anti-ERK1 (catalog no. M12320) was purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories. Polyclonal anti-FLT3 antibody (from goat, AF768) recognizing the extracellular domain of the murine protein, anti-DEP-1 antibody (from goat, AF1934) recognizing murine DEP-1 and cross-reacting with human DEP-1, and anti-CD45 antibody (from goat, AF114) were obtained from R&D Systems (Wiesbaden, Germany). Monoclonal antibody 143-41 against the human DEP-1 (CD148) and polyclonal antibodies recognizing Thr-202 of ERK1/2 (sc-101760) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Human FLT3 was detected with polyclonal rabbit antibody C-20 obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Polyclonal rabbit ubiquitin antibody (U5379) was from Sigma.

For immunoprecipitation of human FLT3, S-18 polyclonal rabbit antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology was used, and for immunoprecipitation of murine FLT3, R&D antibody (AF768) was used. Phosphorylation-specific antibodies against individual tyrosine phosphorylation sites in FLT3 were raised by immunizing rabbits and purified as described earlier (15). 4G10 or pTyr-100 (I-9411) anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies were from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Milton Keynes, UK) or Cell Signaling Technology (Frankfurt, Germany), respectively. Immunoprecipitation of DEP-1 was done with monoclonal mouse antibody 143-41 (sc-21761, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Antibodies recognizing β-actin or vinculin were obtained from Sigma. HRP-coupled secondary anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were from KPL (Gaithersburg, MD). HRP-coupled secondary anti-goat IgG (sc2056) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

DNA Expression Vectors

Plasmid pLKO.1 vectors encoding shRNA constructs targeting murine PTP and plasmid pLKO.1 encoding a nontargeting control shRNA were obtained from Sigma (MISSION® shRNA lentivirus-mediated transduction system, Taufkirchen, Germany). If necessary, the puromycin resistance gene was replaced by a neomycin resistance-conferring gene using standard cloning techniques.

pMSCV-huFLT3-IRES-gfp plasmid encoding wild type human FLT3 was constructed by replacing SHP-2 (kindly provided by Drs. Golam Mohi and Benjamin Neel (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston)) by human FLT3 (9), kindly provided by Hubert Serve (Frankfurt, Germany). For expression of DEP-1, the sequence of human DEP-1 was cut out from pNRTIS33-DEP-1-WT (21) and inserted into the retroviral vector pMEX-IRES-puro (22).

Constructs for expression of GST-DEP-1 (wild type or C1239S cytoplasmic domain) fusion proteins in E. coli were described earlier (23). Expression in bacteria (strain Escherichia coli BL21) and purification of GST fusion proteins were performed by standard techniques. Constructs for transient expression of wild type DEP-1 or DEP-1 C1239S mutant were described previously (24). An expression construct for the DEP-1 D1205A trapping mutant was kindly provided by Dr. Tencho Tenev (The Breakthrough Breast Cancer Centre, Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK).

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated Knockdown of Dep-1

Dep-1 siRNA duplex oligonucleotides (5′-UACUGUGUCUUGGAAUCUAdGdC-3′ (sense) and 5′-UAGAUUCCAAGACACAGUAdGdG-3′ (antisense)) or control siRNA (target DNA sequence AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT; SI03650325) used in this study were obtained from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). siRNA was transfected into THP-1 cells using AMAXA Nucleofector system, program version 01. 1.5 × 106 cells were transfected with 2.1 μg of siRNA using Nucleofector buffer V.

Production of Pseudoviral Particles and Cell Transduction

For generation of retroviral particles, Phoenix amphotropic packaging cells (kindly provided by Dr. Gary Nolan, Stanford, CA) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS. The cells were transiently transfected with the pMSCV-derivative plasmids using polyethyleneimine, and retrovirus-containing media were collected 48 h after transfection. 104 32D cells were infected three times with the pseudotyped particles in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene (1,5-dimethyl-1,5-diazaundecamethylene polymethobromide, AL-118, catalog no. 10,768-9, Sigma). The transduction efficiency was in the range of 10–30% as assessed by parallel transduction with GFP-expressing viral particles. Selecting the population of the transduced cell pool with 2 μg/ml puromycin was started 48 h after transduction. Sufficiently propagated cell pools (5–10 × 106 cells) were subjected for phenotypic characterization immediately after establishment. In some cases, cells were sorted for equal FLT3 levels before analysis.

Production of lentiviral particles and transduction of 32D cells with corresponding cell supernatants was carried out essentially following the above protocol, except that Phoenix gp cells were used for virus particle production by transfecting them with pLKO.1 derivative plasmids in combination with pRev, pEnv-VSV-G, and pMDLg (kindly provided by Dr. Carol Stocking, Hamburg, Germany) (25, 26). Transduced cell pools were selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin. 104 32D cells were infected three times with the pseudotyped particles in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene. The transduced cell pool was selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin or 400 μg/ml G418 48 h post-transduction and subjected to analysis. In some cases cells were sorted for equal FLT3 levels before analysis. Independent rounds for the knockdown of DEP-1 were performed and analyzed five times independently. In each round of transduction, the corresponding control shRNA cell pools were generated and analyzed in parallel.

Physical Association of DEP-1 with Wild Type FLT3

HEK293 cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding DEP-1 WT, DEP-1 C1239S, or DEP-1 D1205A along with a plasmid encoding human FLT3 in the molar ratio 1:1 using polyethyleneimine. 36 h after transfection, cells were starved for 8 h and stimulated with 100 ng/ml FL for 5 min. Cells were then lysed, and immunoprecipitation of DEP-1 or FLT3 was carried out as described above.

DEP-1-mediated Dephosphorylation of FLT3

THP-1 cells were starved in cytokine-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.5% FCS and stimulated with FL (100 ng/ml) for 2.5 min. Subsequently, cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and lysed. For FLT3 immunoprecipitation, lysis was done in 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA. Immunoprecipitated FLT3 was incubated with the amounts of purified GST fusion proteins of wild type or catalytically inactive C1239S DEP-1 catalytic domain indicated in the figure in PTP assay buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 5 mm DTT) at 30 °C for 30 min. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting. Dephosphorylation of FLT3 was analyzed by assessing the ratio of phosphorylated FLT3 (by using phosphotyrosine-specific antibody pTyr-Y100) to total FLT3 protein (detected by anti-FLT3 antibody C-20).

Assessment of Cell Proliferation and Clonal Growth in Methylcellulose

To assess proliferation of the different 32D cell pools, cells were washed twice in IL-3-free medium, seeded in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS, and sodium pyruvate (5 mg/ml) in cytokine-free medium, or supplemented with FL or IL-3. For 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (27), 20,000 cells per well were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated in specified growth conditions. MTT was added in the final concentration of 0.5 μg/μl. The formazan crystals were solubilized, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm. The assay was performed in triplicate. For GFP-based assays, 2 × 105 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (white plates with clear bottom). At the time points indicated in the figure legends, proliferation of quadruplicate samples was determined measuring GFP fluorescence intensity with a TECAN reader (Crailsheim, Germany).

To analyze colony formation of 32D cell lines, 3 × 104 cells were plated in 1 ml of a culture mixture containing Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Invitrogen), 1% methylcellulose, and 20% FCS per well of a 6-well plate. All samples were prepared in triplicate. The plates were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for the indicated time periods before counting and photographing representative sections of the wells. Photographs were taken with a Zeiss AxioCam HRC digital camera attached to a Zeiss Axiovert 25 inverted microscope.

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

To obtain cell populations with a similar FLT3 protein level, cell pools were sorted for a similar GFP level using an ARIA FACS cell sorter (BD Biosciences). For detection of expression of human DEP-1, retrovirally transduced 32D cells were labeled with primary anti-DEP-1 antibody and subsequently co-stained with Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody. Overexpression of DEP-1 was analyzed with a FACS Canto cytometer (BD Biosciences) using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences). For isolation of 32D cells stably overexpressing huDEP-1, an ARIA FACS cell sorter was used.

Signaling Analysis and FLT3 Immunoprecipitation

32D cells were washed twice with PBS and starved in serum- and cytokine-free RPMI 1640 medium for 4 h before stimulation at 37 °C with 50 ng/ml FL or 1 ng/ml IL-3 for the time periods indicated. THP-1 cell were starved in cytokine-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.5% FCS. Subsequently, cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS and lysed. For FLT3 immunoprecipitation, lysis was done in 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA. For detection of activated signaling proteins in cell lysates, RIPA buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% deoxycholate, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA was used. Lysis buffers were freshly supplemented with proteinase inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (2 μg/ml leupeptin, 1% aprotinin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mm PMSF, 1 mm Pefabloc, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm glycerol phosphate), and lysis was allowed on ice for 15 min before thorough vortexing and centrifugation. FLT3 immunoprecipitations were performed by incubating with anti-FLT3 S-18 antibodies at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with protein A- or protein G-Sepharose beads. Adjusted aliquots of the cell extracts were subjected SDS-PAGE, followed by transfer to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and probing with the indicated primary antibodies. After subsequent incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, the blots were developed using Western Lightning chemiluminescence detection (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and quantitatively evaluated using a CCD camera-based system (LAS3000, Fuji). For quantification of specific phosphorylation, blots for phosphorylated proteins were stripped and subsequently reprobed with pan-specific antibodies. Specific phosphorylation was calculated as the ratio of the signals for phosphorylated protein to the signal for total protein detected. Values of the nonstimulated samples of cells expressing the control shRNA cells were set to 1.0.

Radiation-induced Apoptosis

A total of 106 cells were starved from cytokines and serum for 4 h, placed in 6-well plates, and exposed to 5 gray γ-irradiation. Immediately after irradiation, cells were supplemented with FL (50 ng/ml), IL-3 (1 ng/ml), or no cytokine with 10% heat-inactivated FCS. Cell viability was analyzed using the annexin-V-PE apoptosis assay using flow cytometry. Cells staining negative for both annexin-V and 7-aminoactinomycin D were counted as viable cells.

Animal Experiments

Eight- to 10-week-old male C3H/HeJ mice, which are syngeneic to 32Dcl3 cells, were used to assess the in vivo development of leukemia-like disease. 32D muFLT3 shDEP-1 A2/A3 cells (2 × 106) were injected into the lateral tail vein. The experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the local Committee on Animal Experimentation.

RESULTS

Screening of PTP Affecting FLT3 Signaling in Hematopoietic Cells

To analyze the role of individual PTP on the activity of FLT3, we used 32D cells stably expressing FLT3 wild type protein (28). This murine bone marrow-derived cell line is strictly growth factor-dependent and therefore suitable to study receptor-mediated signaling and physiologic activity. A panel of 20 classical PTP was selected according to their known expression in 32D cells or generally in hematopoietic cells (29) or because of a presumed role in oncogenesis or tumor suppression (supplemental Table S1)(17).

shRNA expression cassettes were introduced in 32D FLT3 cells using the MISSION® shRNA lentivirus transduction system. Nonvalidated target sets of 4–5 shRNAs targeting each a particular PTP were packed into lentiviral pseudoparticles and transduced into 32D FLT3 cells. Transduced cell pools were selected by antibiotic treatment starting 2 days post-transduction and were subsequently expanded. Care was taken to ensure relatively high transduction efficiencies (10–30%) and to carry out analyses with cell pools that were only propagated for short periods to minimize clonal drifts. The effect of PTP knockdown on FLT3-mediated signaling quality was characterized by analyzing FL-mediated phosphorylation of ERK as a functional readout. Cells were starved in cytokine-free medium and subsequently stimulated with FL. Whole cell lysates of PTP-shRNA-expressing cells pools were immunoblotted with phospho-ERK antibodies, and its activation was scored. Although many shRNAs had little effect, several PTP-shRNAs caused altered ERK activation. These were subjected to a second validation screen, repeating shRNA transduction and ERK activation measurements with independently derived cell pools. For some positively scoring PTP in the second round, knockdown was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting (supplemental Table S1). Notably, two independent shRNAs targeting DEP-1 (further designated A2 and A3) reproducibly resulted in enhanced FLT3-mediated ERK phosphorylation (supplemental Fig. S1). To validate the knockdown, protein and mRNA levels of DEP-1 were analyzed. As indicated in Fig. 1A, DEP-1 protein was reduced to 7 or 38% using shRNA targets A2 or A3, respectively, as compared with cells expressing a nontargeting control shRNA (or nontransduced cells, supplemental Fig. S2A). DEP-1 mRNA expression was similarly reduced to 9 or 38%, respectively (Fig. 1B). Depletion of CD45 in 32D FLT3 cells also enhanced FL-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2, indicating that this PTP may likewise interfere with FLT3 signaling (supplemental Table S1). A closer investigation of this finding revealed, however, that FLT3 surface expression was elevated in CD45-depleted cells by unknown mechanisms (data not shown). Therefore, the role of CD45 was not further investigated at this point. To analyze if DEP-1 depletion would lead to alterations in CD45 levels, the latter were checked in DEP-1-depleted cell pools. CD45 protein and mRNA levels were, however, unaffected by DEP-1 depletion (supplemental Fig. S2, A and C).

FIGURE 1.

Down-regulation of DEP-1 in 32D cells results in enhanced FLT3 signaling and enhanced phosphorylation of FLT3. A, whole cell lysates of 32D cells expressing wild type muFLT3 and DEP-1-specific shRNA (targets A2 or A3) or a nontargeting control shRNA were subjected to SDS-PAGE, blotted to a PVDF membrane, and analyzed with antibodies recognizing DEP-1 and vinculin. Chemiluminescence signals were detected using a CCD camera-based chemiluminescence detection system and calculated relative to vinculin. Relative (rel.) levels of DEP-1 normalized to vinculin are indicated. B, quantitative RT-PCR for DEP-1 mRNA in the above cell lines. Mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. C–F, indicated cell lines were starved for 4 h in serum- and cytokine-free medium and were stimulated with FL (50 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods. C–H, activation of ERK (C and E), AKT (C), STAT5 (D), or PLCγ (G) was analyzed using the indicated phospho-specific antibodies. Blots were reprobed for total signaling proteins. β-Actin was analyzed as loading control. Numbers above the phospho-specific blots represent quantification of the phosphor-specific signals, normalized to the corresponding signals with pan-specific antibodies, and relative to the signal in unstimulated cells harboring control shRNA, which was set to 1.0. The blots shown are representative for at least three experiments with consistent results. F, comparison of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 detected by conventional anti-pThr-202/pTyr-204 antibodies, and anti-pThr-202 antibodies. Ratio between ERK1/2 phosphorylation of shDEP-1 to shControl cells of three independent experiments is shown. H, FLT3 was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLT3, phosphotyrosine (pY100), or phospho-FLT3 (pY591) antibodies. HM, high mannose; CG, complex glycosylated FLT3. Quantification refers to complex glycosylated (surface) FLT3. Representative blots of at least three time repeated experiments are shown.

We considered the possibility that PTP depletion would affect signaling of FLT3-ITD, the transforming mutant version of FLT3. shRNA-mediated down-regulation of DEP-1 did not, however, alter the autophosphorylation of FLT3-ITD nor the magnitude of constitutive or FL-stimulated FLT3-ITD signaling (data not shown). It is possible that FLT3-ITD signaling can override the activity of DEP-1, and therefore DEP-1 depletion has no further consequences in FLT3-ITD-expressing cells.

Depletion of DEP-1 Stimulates FLT3 Signaling in Myeloid Cells

Subsequently, the effect of DEP-1 depletion on FLT3 signaling activity was characterized. Major signaling pathways downstream of the FLT3 wild type receptor are the PI3K/AKT and the RAS/ERK pathways. Therefore, phosphorylation of AKT and ERK was monitored. Enhanced phosphorylation of ERK in DEP-1-depleted cells lines with either shRNA A2 or A3 confirmed the screening results. Phosphorylation of ERK was enhanced reproducibly. In contrast, FL-mediated activation of AKT remained unchanged in response to DEP-1 knockdown as compared with control cells (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, the kinetics of signaling of control shRNA and DEP-1-depleted 32D FLT3 cell lines was not different (Fig. 1C). Additionally, we analyzed FL-mediated activation of STAT5. Although STAT5 is known to be not activated or only weakly activated by ligand-stimulated wild type receptor, oncogenic FLT3 variants mediate constitutive activation of STAT5 (9, 28, 30). Depletion of DEP-1 resulted in a slight but reproducibly elevated STAT5 phosphorylation in cells containing shRNA A2, which caused the more pronounced DEP-1 depletion (Fig. 1D). No significant alteration of STAT5 phosphorylation could, however, be observed in cells expressing DEP-1 shRNA A3 (data not shown).

Sacco et al. (31) have recently demonstrated that DEP-1 can directly regulate ERK activity by dephosphorylating pTyr in the pThr-202–Glu–pTyr-204 motif of the activation loop (numbering according to the human ERK1 protein). The pERK1/2 antibody employed for our screening and the experiments described above recognizes both phosphorylated Thr-202 and pTyr-204 with an unknown contribution of the two single sites to the combined signal intensity. Therefore, increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation by DEP-1 knockdown in our experiments could potentially have been caused by reduced direct DEP-1 activity toward ERK1/2 pTyr-204. We reasoned that it should be possible to distinguish between direct dephosphorylation of ERK1/2 by DEP-1 or an event regulated by DEP-1 upstream of ERK1/2 by analyzing phosphorylation of ERK1/2 at Thr-202. Phosphothreonine 202 cannot serve as a direct substrate of DEP-1; therefore, the effects of DEP-1 knockdown on ERK1/2 pThr-202 could only be caused by upstream events. Indeed, depletion of DEP-1 caused stimulation of ERK1/2 Thr-202 phosphorylation to a comparable extent as the phosphorylation detected with the “conventional” antibody recognizing the doubly phosphorylated peptide (Fig. 1, E and F). We also analyzed the phosphorylation of PLCγ in response to FLT3 activation. This was likewise elevated in DEP-1-depleted 32D FLT3 cells compared with cells expressing the control shRNA (Fig. 1G).

Taken together, several signaling molecules downstream of FLT3 were found activated in DEP-1-depleted cells, including ERK1/2, PLCγ, and, weakly, STAT5. This observation and the finding of elevated ERK1/2 Thr-202 phosphorylation are consistent with a role of DEP-1 in attenuating an event proximal to receptor activation.

We therefore addressed the question whether FL-stimulated receptor phosphorylation was directly affected by DEP-1 depletion. Notably, FLT3 is detectable as a 130-kDa immature high mannose glycoprotein and as 150-kDa complex glycosylated protein (14). Only the latter form is accessible for FL at the cell surface, and consequently, only the 150-kDa band shows increased phosphorylation upon FL stimulation. Immunoblotting of immunoprecipitated FLT3 derived from DEP-1-depleted 32D cells with phosphotyrosine-specific antibodies revealed that total FLT3 phosphorylation was indeed somewhat elevated as compared with the FLT3 immunoprecipitated from control cells (Fig. 1H). Tyrosine residue 591 of FLT3 is known to be phosphorylated in vivo following ligand stimulation and has been identified as site contributing to Src binding and activation (19, 32). Phosphorylation of this specific tyrosine residue was also enhanced in cells where DEP-1 expression was down-regulated (Fig. 1H). The limited quality of muFLT3-specific antibodies, however, greatly limited analysis of FLT3 phosphorylation in these particular cells.

DEP-1 Affects Phosphorylation of FLT3 at Multiple Sites

To study DEP-1-mediated receptor dephosphorylation in more detail, we focused on cells expressing human FLT3. In this analysis, we took advantage of antibodies that are specific for individual FLT3 phosphorylation sites. These were previously used to comprehensively characterize the phosphorylation pattern of human FLT3 proteins in Ba/F3 cells (15). For this purpose, we generated 32D cells stably expressing the human FLT3 receptor following the previously described strategy of Grundler et al. (33). Human FLT3 encoding DNA was placed on a retroviral expression cassette upstream of a transcriptionally coupled GFP gene. 32D cells were transduced with corresponding pseudoviral particles, and cell populations with comparable GFP levels were obtained by sorting using flow cytometry. These cells were subsequently transduced with lentiviral particles encoding DEP-1-shRNA A2, A3, or nontargeting control shRNA. The obtained knockdown of DEP-1 was comparable with the one in 32D cells expressing the murine FLT3 receptor (supplemental Fig. S3). In addition, cells harboring both DEP-1-specific shRNAs were obtained by sequential transduction with DEP-1 A3 shRNA on a vector with puromycin resistance, followed by transduction of A2 shRNA on a vector allowing G418 selection. Transduction of cells with both shRNAs yielded a more pronounced down-regulation of DEP-1 (supplemental Fig. S3).

Initially, we analyzed total FLT3 tyrosine phosphorylation. FLT3 immunoprecipitated from FL-stimulated 32D cells expressing both shRNAs A2/A3 showed a more than 2-fold higher overall phosphorylation as compared with cells expressing the control shRNA (Fig. 2A). The kinetics of FL-mediated FLT3 phosphorylation was similar in both cell types as follows: 2.5 min after addition of the FL receptor, phosphorylation already reached a maximum, remained nearly stable until 5 min, and decreased to nearly control values 10 min after onset of stimulation. Noteworthy, a significant amount (up to 50%) of phosphorylated FLT3 molecules was detectable at a molecular mass above 200 kDa. Reprobing of the immunoblot with a specific antibody revealed ubiquitination of the receptor, whose change in intensity with time mirrored the kinetics of phosphorylation (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Down-regulation of DEP-1 causes hyperphosphorylation of human FLT3. 32D cells expressing human FLT3- and DEP-1-specific shRNAs A2 and A3 or a control shRNA were starved and stimulated with FL (50 ng/ml) for indicated time periods. FLT3 was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLT3 or phosphotyrosine (4G-10, A) or phospho-FLT3 (pY591, B) antibodies. HM, high mannose; CG, complex glycosylated FLT3; UB, ubiquitinated. Graphs demonstrate specific phosphorylation of total FLT3 receptor. Phosphospecific to total FLT3 receptor chemiluminescence signals are shown (sum of high mannose, complex glycosylated FLT3, and UB protein). Means ± S.D. are of at least three independent experiments.

Next, FLT3 phosphorylation was studied in detail using site-specific antibodies. Antibodies recognizing the phosphorylation sites pTyr-572, pTyr-589, pTyr-591, pTyr-599, pTyr-768, pTyr-793, pTyr-842, and pTyr-955 have been described earlier and were all validated for specificity using appropriate tyrosine-mutant FLT3 versions (15, 19). Tyrosine phosphorylation at these positions was analyzed by immunoblotting of immunoprecipitated huFLT3. Multiple experiments were performed and quantified. An exemplary blot is shown for pTyr-591 in Fig. 2B. Example blots for the other pTyr sites used are shown in the supplemental Fig. S4, A–G. The stimulation of site-specific FLT3 tyrosine phosphorylation in the DEP-1-depleted cells compared with control cells is shown in Table 1. Values were normalized to pTyr of control cells.

TABLE 1.

Alteration of site-specific phosphorylation of human FLT3 in response to DEP-1 depletion

32D cells expressing human FLT3 and DEP-1-specific shRNAs A2 and A3 or a control shRNA were starved and stimulated with FL (50 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods. FLT3 was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by immunoblotting with site-specific phosphotyrosine FLT3 antibodies as indicated or phosphotyrosine antibody 4G-10. Total immunoprecipitated FLT3 was quantified using anti-FLT3 antibodies. Data represent the ratio of specific FLT3 phosphorylation to total receptor (sum of all of FLT3 forms, including ubiquitinated protein) of DEP-1-depleted cells divided by values obtained from control shRNA-expressing cells. The data are mean values of at least three independent experiments. Standard deviation was calculated using the ratios of three independent experiments. Because of the low phosphorylation of unstimulated samples, the calculation was error-prone and therefore excluded from the table.

| pY site | Specific phosphorylation (shDEP-1 to shControl) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 5 | 10 | FL | |

| min | ||||

| pY572 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | |

| pY589 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | |

| pY591 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | |

| pY599 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | |

| pY768 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | |

| pY793 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | |

| pY842 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | |

| pY955 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | |

| Total (4G10) | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | |

In general, phosphorylation of all FLT3 tyrosine sites was elevated in the DEP-1 knockdown cells. This applied to the FL-stimulated receptor, but some enhanced specific phosphorylation was already visible in the unstimulated resting cells (Fig. 2, A and B; supplemental Fig. S4, A–G), suggesting that DEP-1 may interact with both unstimulated and ligand-stimulated FLT3. Kinetics of stimulation and decay of phosphorylated receptor remained unchanged upon DEP-1 depletion. The juxtamembrane tyrosine residues (Tyr-589, Tyr-591, and Tyr-599) showed a more pronounced elevation of phosphorylation in the DEP-1-depleted line. In addition, kinase domain-localized tyrosines Tyr-842 and Tyr-955 likewise showed a rather pronounced stimulation of FLT3 phosphorylation upon DEP-1 depletion. In contrast, phosphorylation of tyrosine residues Tyr-572, Tyr-768, and Tyr-793 was only moderately affected. To further link elevated FLT3 phosphorylation to the knockdown of DEP-1 expression, alteration of receptor phosphorylation was compared in cell lines expressing only shRNA A3, A2, or both. As shown in supplemental Fig. S5, enhancement of FLT3 phosphorylation occurred in all DEP-1-depleted cells, indicating that the effect is independent of the targeting shRNA sequence. Moreover, the stimulation of FLT3 phosphorylation was inversely correlated with the degree of DEP-1 down-regulation (supplemental Fig. S5), supporting the conclusion that DEP-1 depletion and FLT3 hyper-phosphorylation are directly linked.

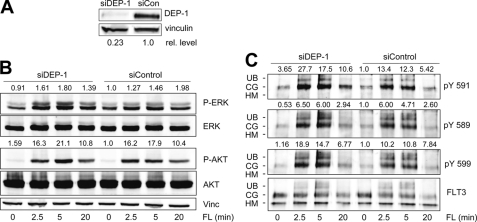

To further characterize DEP-1 as a negative regulator of FLT3, we have chosen the human AML cell line THP-1 constitutively expressing wild type FLT3. For acute down-regulation of DEP-1, the cells were transiently transfected with a specific siRNA duplex. Using this technique, the most efficient DEP-1 knockdown was observed 48 h post-transfection. DEP-1 levels were reduced to 20–30% as compared with control cells (Fig. 3A). The effects of transient DEP-1 knockdown in this cell line were less pronounced than in 32D cells. However, analysis of downstream signals revealed that stimulation of FLT3 in DEP-1-depleted THP-1 cells weakly (about 1.5-fold) but reproducibly enhanced the activation of ERK as compared with the cells transfected with control siRNA, whereas activation of AKT remained unchanged (Fig. 3B). This was consistent with the findings in 32D cells. In addition, down-regulation of DEP-1 resulted in a slight elevation of phosphorylation of FLT3 autophosphorylation sites Tyr-589, Tyr-591, and Tyr-599 compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 3C). 2.5 min after FL stimulation, phosphorylation of tyrosine Tyr-591 and Tyr-599 were 1.5–2-fold elevated in response to DEP-1 depletion.

FIGURE 3.

Depletion of DEP-1 in THP-1 cells results in elevated FL-mediated signaling activity and FLT3 receptor phosphorylation. Human THP-1 cells were transfected with a siRNA targeting DEP-1 (siDEP-1) or a nontargeting control siRNA (siCon). 48 h post-transfection, cells were starved and stimulated with FL (100 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods. Cells were lysed and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. A, cell lysates were probed with antibodies recognizing DEP-1 and vinculin (Vinc.). Depletion of DEP-1 was quantified as ratio of DEP-1 to vinculin. Relative (rel.) levels of DEP-1, normalized to vinculin, are indicated. B, total cell lysates were probed with antibodies recognizing phosphorylated signaling proteins AKT or ERK. Blots were reprobed for total signaling proteins. C, subsequent to stimulation and cell lysis, FLT3 was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by immunoblotting with site-specific phosphotyrosine FLT3 antibodies as indicated and reprobed for total immunoprecipitated FLT3. HM, high mannose; CG, complex glycosylated; UB, ubiquitinated FLT3. Numbers above the phosphotyrosine blots indicate specific phosphorylation of complex glycosylated FLT3. The blots are representative for at least four experiments.

Overexpression of DEP-1 Impairs FLT3 Receptor Phosphorylation and Activity

Because DEP-1 depletion led to FLT3 activation, overexpression of this phosphatase should result in inverse effects. To address this question, 32D cells expressing FLT3 were transduced with a retroviral expression cassette encoding DEP-1, and stable cell pools were selected and tested for elevated DEP-1 levels. As it turned out, initially detected DEP-1 overexpression was rather unstable and diminished rapidly. Therefore, a population of puromycin-resistant cells with significant synthesis of DEP-1 was enriched by sorting of immunofluorescence-labeled cells using a cell sorting system. These cells were briefly expanded and then analyzed immediately. As shown by immunoblotting of whole cell lysates and surface immunostaining with subsequent flow cytometry, the selected cells showed a significant overexpression of DEP-1 compared with control cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Assuming similar reactivity of the used antibody for (endogenous) murine and (exogenous) human DEP-1, calculations from immunoblotting data indicated an extent of overexpression of 8–10-fold in these sorted pools. 32D FLT3 cells overexpressing DEP-1 were characterized by reduced FL-mediated signaling activity (Fig. 4C). FL-mediated activation of ERK and AKT was drastically reduced in response to overexpression of DEP-1. This observation was different from the situation observed in DEP-1-depleted cells, where AKT remained unaffected. Moreover, general tyrosine phosphorylation (as shown using 4G-10 tyrosine-specific antibody), as well as specific phosphorylation of FLT3 (exemplified for the juxtamembrane tyrosine residue Tyr-589), was considerably reduced about 2-fold (Fig. 4D). Taken together, overexpression of DEP-1 in 32D cells resulted in impaired FLT3 phosphorylation and signaling activity.

FIGURE 4.

Overexpression of DEP-1 impairs FLT3 signaling and phosphorylation. 32D cells expressing huFLT3, stably transduced with an expression construct for human DEP-1 or the corresponding control vector, were analyzed for DEP-1 expression, FL-mediated signaling activity, and receptor phosphorylation. A, whole cell lysates were blotted with antibodies recognizing both endogenous murine and exogenous human DEP-1 and vinculin for control (Con). B, expression of transduced huDEP-1 was detected by labeling with a monoclonal antibody recognizing a surface epitope of human DEP-1 and subsequent labeling with anti-mouse-Cy3 antibody. Surface-localized DEP-1 was quantified by flow cytometry. C and D, indicated cell lines were starved for 4 h in serum- and cytokine-free medium and were stimulated with FL (50 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods. Whole cell lysates were blotted and activation of ERK or AKT was analyzed using phospho-specific antibodies. Blots were reprobed for total signaling proteins. D, phosphorylation of FLT3 was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G-10 and anti-phospho FLT3 antibody pTyr-591, and blots were subsequently reprobed for total FLT3. HM, high mannose; CG, complex glycosylated FLT3. Representative blots of experiments repeated at least three time are demonstrated.

DEP-1 Interacts Directly with FLT3

To elucidate the possibility that phosphorylated FLT3 serves as a direct substrate of DEP-1, we first analyzed the capacity of DEP-1 to dephosphorylate FLT3 in vitro. Phosphorylated FLT3 was immunoprecipitated from FL-stimulated THP-1 cells. Aliquots of immunoprecipitated FLT3 were then incubated with different amounts of recombinant GST-DEP-1 (catalytic domain) fusion proteins, and the dephosphorylation was subsequently assessed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies. As shown in Fig. 5A, catalytically active DEP-1 dephosphorylated FLT3 in a concentration-dependent manner. In contrast, incubation of FLT3 with catalytically inactive DEP-1 C1239S protein did not alter the phosphorylation status of FLT3.

FIGURE 5.

DEP-1 directly interacts with and dephosphorylates FLT3. A, THP-1 cell were starved in cytokine-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.5% FCS, and left unstimulated, or were stimulated with FL (100 ng/ml) for 30 min (FL +). Cells were subsequently lysed, and FLT3 was immunoprecipitated. Immunoprecipitated FLT3 obtained from stimulated cells was incubated with the indicated amounts of recombinant wild type GST-DEP-1 (catalytic domain) fusion protein (WT) or the corresponding catalytically inactive GST-DEP-1 C1239S protein (CS) in the indicated amounts (μg of protein) for 30 min. The samples were subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Blots were probed with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (pY100) and reprobed with anti-FLT3 antibody, as indicated. Tyrosine phosphorylation of FLT3 was quantified as the ratio of phosphorylated FLT3 to total FLT3 (numbers above pY100 blot). This experiment was performed twice with consistent results. B, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with expression plasmids for human FLT3 and wild type (WT) DEP-1 or catalytically inactive DEP-1 C1239S (CS) in the indicated amounts (μg) using polyethyleneimine. 36 h after transfection, cells were starved for 8 h and then stimulated with 100 ng/ml FL for 5 min. The cells were subsequently lysed, and FLT3 was immunoprecipitated (IP). The blots were probed for phosphorylation of FLT3 by immunoblotting and reblotted for the amounts of FLT3. Quantification denotes the FLT3 phosphorylation signal normalized to the amounts of FLT3, relative to the control in absence of DEP-1. Co-purified DEP-1 protein in the immunoprecipitates was analyzed using anti-DEP-1 antibody. DEP-1 expression in the cell lysates was also analyzed (lowest panel). HM, high mannose; CG, complex glycosylated FLT3. A representative experiment of three with consistent results is depicted. C, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding human FLT3 along with wild type DEP-1 (WT) or the DEP-1 D1205A trapping mutant (DA, as indicated) in the molar ratio 1:1. The cells were starved and stimulated with FL as in A and lysed, and either DEP-1 (upper panel) or FLT3 (lower panel) was immunoprecipitated. For a specificity control, immunoprecipitation was carried out with unspecific IgG. Immunoprecipitated and co-immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLT3, anti-DEP-1, or anti-phosphotyrosine (pY100) antibodies as indicated. HM, high mannose; CG, complex glycosylated FLT3. A representative experiment of three with consistent results is shown.

In addition, dephosphorylation of FLT3 by DEP-1 was tested by co-expression experiments (Fig. 5B). FLT3 and DEP-1 were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells, and the cells were stimulated with FL, and FLT3 was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by immunoblotting. Overexpression of wild type DEP-1 strongly reduced FLT3 autophosphorylation, whereas the FLT3 phosphorylation status did not change upon co-expression of the inactive DEP-1 C1239S mutant. Interestingly, probing immunoprecipitated FLT3 for the presence of DEP-1 revealed an efficient association of the DEP-1 C1239S mutant protein but not of wild type DEP-1 with FLT3 (Fig. 5B).

Association of catalytically inactive PTP versions with their substrates is often comparatively stable, whereas the complex between active PTP and substrate rapidly decomposes because of efficient dephosphorylation. This phenomenon has been described as PTP “substrate trapping” (34). We also employed another DEP-1 substrate- trapping mutant DEP-1 D1205A, which has previously been used to find substrates (35). Again, a physical interaction of DEP-1 and FLT3 could be demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5C, upper panel). DEP-1 D1205A mutant protein efficiently co-immunoprecipitated with FLT3. FL-mediated stimulation of FLT3 phosphorylation even enhanced interaction of both proteins. Wild type DEP-1 was, however, not co-purified by FLT3, consistent with an effective dephosphorylation of FLT3 by DEP-1.

Reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation similarly revealed that both proteins interact directly. Although the wild type DEP-1 protein did not co-purify FLT3, DEP-1 D1205A efficiently co-immunoprecipitated FLT3. Again, co-purification of FLT3 was slightly elevated in response to ligand stimulation of FLT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5C, lower panel). Interestingly, by probing immunoprecipitated DEP-1 with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies, we could observe that the DEP-1 DA trapping mutant was phosphorylated by FLT3, indicating a mutual enzymatic interaction.

FLT3-ITD could be co-immunoprecipitated with DEP-1 C1239S protein with similar efficiency as wild type FLT3 (supplemental Fig. 6), excluding that the lack of an effect of DEP-1 knockdown on FLT3-ITD autophosphorylation (see above) was due to an inability of the mutant FLT3 for interaction with DEP-1.

Suppression of DEP-1 Stimulates FLT3-dependent Proliferation and Colony Formation of 32D Cells

To characterize the physiological consequences of altered FLT3 activity, first proliferation of 32D cell lines with shRNA-mediated DEP-1 knockdown was analyzed. Proliferation was measured using either MTT assays or measurement of GFP fluorescence, which is correlated with cell numbers. 32D muFLT3 cell lines remained cytokine-dependent, irrespective of DEP-1 depletion. No appreciable proliferation could be observed if cells were cultivated in the absence of cytokine. The FL-mediated growth of cells expressing DEP-1 shRNA A2 was, however, stimulated compared with the shRNA control cells (Fig. 6, A and B). The effect was quite moderate when scored with the MTT assay after 3 days but more pronounced upon prolonged growth and detecting GFP fluorescence. No growth alteration could be observed for cells harboring the shRNA A3 (data not shown), indicating that the achieved suppression levels of DEP-1 in these cells were insufficient to translate to a growth response. Incubation of the cells in presence of IL3 resulted in strong growth stimulation. We also observed a very weakly elevated IL3-stimulated growth for the DEP-1-depleted cells as compared with the control cells (Fig. 6B). This finding may indicate that events downstream of IL3 receptor stimulation are perhaps also negatively controlled by DEP-1, a possibility that requires further investigation.

FIGURE 6.

Depletion of DEP-1 stimulates proliferation and clonal growth of 32D cell lines. A, 32D cells expressing wild type muFLT3 and DEP-1 shRNA A2 or control shRNA were seeded in 96-well plates and cell growth in the absence of cytokines, in the presence of FL (20 ng/ml), or in the presence of IL-3 (2 ng/ml) and was measured after 2 days using the MTT method. B, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 0.8 × 105 per ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum without cytokines, with FL (20 ng/ml), or IL-3 (2 ng/ml) as indicated. Cell growth was measured at the indicated time points by measuring cellular GFP fluorescence. Values are means of triplicates, and the shown data set is representative for three experiments with consistent results. C, clonal growth of 32D cells in methylcellulose. The above cell pools were subjected to colony formation assays in methylcellulose, in cytokine in the absence or presence of FL (20 ng/ml) or IL-3 (2.5 ng/ml). Representative sections were photographed after 12 days (FL samples) or 6 days (IL-3 samples) of culture, and colonies were quantified by counting representative fields of the wells.

Because STAT5 acts as an important mediator of cellular transformation and we had observed a weakly enhanced activation of STAT5 upon DEP-1 depletion, we subjected the DEP-1-depleted cell lines to colony assays in the presence of FL in semisolid media. Although the control shRNA expressing cells did not grow in methylcellulose plates, the efficient knockdown of DEP-1 using shRNA A2 reproducibly translated into colony growth (Fig. 6C). In the presence of IL-3, abundant colony formation of all cell lines occurred, and colony numbers were not different in control cells or DEP-1-depleted cells. Somewhat increased size of colonies of DEP-1-depleted cells in the presence of IL-3 may correlate to the above described weak growth advantage. No colonies were formed in the absence of cytokine, indicating that colony formation of DEP-1-depleted cells in the presence of FL is specifically mediated by FLT3. Prompted by this capacity of DEP-1-depleted cells to form colonies in semisolid medium, we addressed the question as to whether the elevated FLT3 activity would possibly translate into driving tumor formation in vivo. Therefore, the ability of DEP-1-depleted 32D cells expressing wild type FLT3 to cause a leukemia-like disease in syngeneic C3H/HeJ mice was tested. As shown previously, in these experiments FLT3-ITD-expressing 32D cells caused development of a myeloproliferative disease within 2–3 weeks (18), but animals injected with DEP-1-depleted 32D FLT3 wild type cells did not develop an obvious disease up to 3 months after injection (data not shown).

It had been reported that constitutively active FLT3 induces resistance to radiation-induced apoptosis (9). Therefore, we finally also examined the effect of elevated FLT3 activity in DEP-1-depleted 32D FLT3 cells on DNA damage-induced apoptosis. As shown in supplemental Fig. S7, 32D FLT3 shDEP-1 cells remained highly sensitive to γ-irradiation. Three days after exposure, less than 10% viable cells were detected.

DISCUSSION

By carrying out a screen of 20 different PTP, we identified DEP-1/PTPRJ as a phosphatase negatively affecting the signaling activity of FLT3. To perform the screen, we have chosen phosphorylation of ERK as a surrogate readout of altered receptor kinase activity. Depletion of DEP-1 reproducibly showed a robust stimulation of ERK phosphorylation for two independent shRNA cassettes, indicating that the observed effects were not caused by off-target effects. Furthermore, overexpression of DEP-1 in the same system led to a reduction of FLT3 signaling. We have previously established SHP-2 as a positive mediator of FLT3 signaling and FLT3-dependent cell proliferation in 32D cells (18). Several PTP can dephosphorylate FLT3 in an overexpression setting (14). DEP-1 is the first PTP for which a role in negative regulation of FLT3 signaling has now been demonstrated unequivocally with a loss-of-function approach.

DEP-1 could potentially affect FLT3 signaling by regulating receptor activity directly, by dephosphorylating downstream signaling molecules, or both. Elevated ERK activation upon FLT3 activation as seen in DEP-1-depleted cell lines could indicate a direct regulation of ERK phosphorylation by DEP-1, as has been described recently (31). Similar considerations could be made for the observed weak elevation of STAT5 phosphorylation in DEP-1-depleted cells. Showing elevated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 Thr-202 upon DEP-1 depletion, we could, however, rule out that increased ERK1/2 activation occurs solely through direct ERK dephosphorylation. Hyperphosphorylation at Thr-202 upon DEP-1 knockdown can only occur by an upstream event. Also, in addition to activation of ERK1/2 and weak STAT5 activation, we observed enhanced phosphorylation of PLCγ, another known signaling molecule downstream of FLT3. These findings are consistent with data sets demonstrating direct dephosphorylation of FLT3 by DEP-1. First, hyperphosphorylation of FLT3 occurred in DEP-1-depleted cells. Hyperphosphorylation was detectable at multiple phosphorylation sites, was observed with two different shRNA constructs and a distinct siRNA pool, was dependent from the extent of DEP-1 depletion, and was detectable in two different cell types. Second, recombinant DEP-1 dephosphorylated immunoprecipitated FLT3 in vitro and co-expressed DEP-1 dephosphorylated FLT3 in stably transfected 32D cells and transiently transfected HEK293 cells. Third, mutual co-immunoprecipitation of FLT3 and DEP-1 substrate trapping mutants further established FLT3 as a bona fide substrate of DEP-1.

DEP-1 has been described earlier as a PTP that can dephosphorylate receptor tyrosine kinases, including the EGF receptor (36, 37), PDGFβ receptor (38), VEGF receptor, and c-Met (39, 40). Our data demonstrate that DEP-1 can in addition dephosphorylate the receptor tyrosine kinase FLT3. As suggested previously (37), DEP-1 thus appears to be a relatively pan-specific PTP for receptor tyrosine kinases.

Interestingly, depletion of DEP-1 affected phosphorylation of particular tyrosine sites differently. Among the regulated sites, Tyr-572, which was identified to be phosphorylated in 32D but not in Ba/F3 cells (19), was least affected in response to DEP-1 down-regulation. Tyr-572 contributes to the autoinhibitory conformation of the juxtamembrane domain (41). Likewise Tyr-768, established as one of the binding sites for Grb2, showed only weak stimulation of phosphorylation in DEP-1-depleted cells. Phosphorylation of tyrosine residues Tyr-589 and Tyr-591, which are known as prominently contributing to signaling activity of wild type and oncogenic FLT3 protein, including STAT5 activation downstream of FLT3-ITD (32, 42), were among the most strongly stimulated sites in DEP-1-depleted 32D cells. Hyperphosphorylation of these sites may cause the observed STAT5 activation upon DEP-1 knockdown. In addition, kinase domain-localized Tyr-842, and to a lesser extent Tyr-793, which are also involved in activity regulation, were also phosphorylated more strongly upon DEP-1 depletion (8, 43). Differential effects of DEP-1 on the different phosphorylation sites could reflect differential accessibility by steric reasons or be related to DEP-1 substrate specificity, as shown earlier for the PDGFβ receptor (44). Clearly, dephosphorylation of FLT3 by DEP-1 is another example of site selectivity of a PTP for a multiply phosphorylated cellular substrate. Whereas the DEP-1 knockdown affected mainly the extent of FL-stimulated phosphorylation of the mature, surface-located FLT3 and its ubiquinated counterpart, a weak elevation of basal phosphorylation could also be detected for some sites, for example Tyr-591 and Tyr-842. This observation indicates that DEP-1 may interact not only with a ligand-stimulated receptor but to some extent also with unstimulated FLT3, possibly to prevent basal phosphorylation.

Depletion of DEP-1 stimulated FL-dependent proliferation of 32D cells. This phenotype may relate to elevated ERK activation observed in these cells. Remarkably, DEP-1 depletion also caused 32D cells expressing wild type FLT3 to form colonies in semisolid medium in an FL-dependent manner. This may be explained by the slight but reproducible stimulation of STAT5 activation. Further pathways may, however, be involved, which we are currently trying to identify. This includes pathways activated by IL-3, because somewhat elevated responses to IL-3 were also observed in the DEP-1-depleted cells, including a moderately elevated proliferation. Despite driving colony formation in vitro, DEP-1 depletion did not lead to the development of myeloproliferative disease when the 32D cells were injected into syngeneic mice. Thus, DEP-1 depletion contributes to but is not sufficient for leukemic cell transformation via FLT3 activation. It will be important to analyze if loss of DEP-1 functionality occurs in the context of AML.

Although the data presented here identify DEP-1 as a FLT3-regulating PTP, the effects of shRNA-mediated depletion of DEP-1 on signaling and biological readouts were relatively moderate. It appears likely that other PTP cooperate with DEP-1 in the dephosphorylation of FLT3 and/or inactivation of downstream signaling events. Using Ptprj knock-out mice and CD45/Ptprj double knock-out mice, Zhu et al. (45) recently uncovered a role of DEP-1 for B-cell and macrophage immunoreceptor signaling, which only became apparent in the background of the CD45 knock-out mice. These studies clearly indicated a remarkable redundancy of the two only distantly related transmembrane PTP for regulation of Src family kinases in B-cells and macrophages (45). Similarly, other PTPs may cooperate with DEP-1 in regulation of FLT3 signaling and have the capacity to compensate DEP-1 loss-of-function. Although knockdown of CD45 in 32D FLT3 cells increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and of FLT3 by yet unclear mechanisms (supplemental Table S1 and data not shown). A combinatorial depletion of the DEP-1 and CD45 did not result in synergistic effects on FLT3-mediated signaling (data not shown). The possibility of redundant activities of DEP-1 and other PTP on FLT3 need to be explored in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ari Elson and Akepati Vasudheva Reddy for help with PTP-GLEPP1 expression analysis and Drs. Mohi, Neel, Tenev, and Nolan for reagents. We also thank Dr. Hubert Serve for providing array data of hematopoietic 32D FLT3 cells and DNA constructs.

This work was supported by European Community Grant “PTP-NET” Marie Curie Network MRTN-CT-2006-035830 and Deutsche Krebshilfe Collaborative Grant 108401, TP2 (to F. D. B.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7 and Table S1.

- AML

- acute myeloid leukemia

- PTP

- protein-tyrosine phosphatase

- FL

- FLT3 ligand

- PLCγ

- phospholipase Cγ

- ITD

- internal tandem duplication

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stirewalt D. L., Radich J. P. (2003) Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 650–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schmidt-Arras D., Schwäble J., Böhmer F. D., Serve H. (2004) Curr. Pharm. Des. 10, 1867–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gilliland D. G., Griffin J. D. (2002) Blood 100, 1532–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thiede C., Steudel C., Mohr B., Schaich M., Schäkel U., Platzbecker U., Wermke M., Bornhäuser M., Ritter M., Neubauer A., Ehninger G., Illmer T. (2002) Blood 99, 4326–4335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Small D. (2006) Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program, 178–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakao M., Yokota S., Iwai T., Kaneko H., Horiike S., Kashima K., Sonoda Y., Fujimoto T., Misawa S. (1996) Leukemia 10, 1911–1918 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heidel F., Solem F. K., Breitenbuecher F., Lipka D. B., Kasper S., Thiede M. H., Brandts C., Serve H., Roesel J., Giles F., Feldman E., Ehninger G., Schiller G. J., Nimer S., Stone R. M., Wang Y., Kindler T., Cohen P. S., Huber C., Fischer T. (2006) Blood 107, 293–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kindler T., Breitenbuecher F., Kasper S., Estey E., Giles F., Feldman E., Ehninger G., Schiller G., Klimek V., Nimer S. D., Gratwohl A., Choudhary C. R., Mueller-Tidow C., Serve H., Gschaidmeier H., Cohen P. S., Huber C., Fischer T. (2005) Blood 105, 335–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mizuki M., Fenski R., Halfter H., Matsumura I., Schmidt R., Müller C., Grüning W., Kratz-Albers K., Serve S., Steur C., Büchner T., Kienast J., Kanakura Y., Berdel W. E., Serve H. (2000) Blood 96, 3907–3914 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kelly L. M., Yu J. C., Boulton C. L., Apatira M., Li J., Sullivan C. M., Williams I., Amaral S. M., Curley D. P., Duclos N., Neuberg D., Scarborough R. M., Pandey A., Hollenbach S., Abe K., Lokker N. A., Gilliland D. G., Giese N. A. (2002) Cancer Cell 1, 421–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choudhary C., Müller-Tidow C., Berdel W. E., Serve H. (2005) Int. J. Hematol. 82, 93–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmidt-Arras D., Böhmer S. A., Koch S., Müller J. P., Blei L., Cornils H., Bauer R., Korasikha S., Thiede C., Böhmer F. D. (2009) Blood 113, 3568–3576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Choudhary C., Olsen J. V., Brandts C., Cox J., Reddy P. N., Böhmer F. D., Gerke V., Schmidt-Arras D. E., Berdel W. E., Müller-Tidow C., Mann M., Serve H. (2009) Mol. Cell 36, 326–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schmidt-Arras D. E., Böhmer A., Markova B., Choudhary C., Serve H., Böhmer F. D. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 3690–3703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Razumovskaya E., Masson K., Khan R., Bengtsson S., Rönnstrand L. (2009) Exp. Hematol. 37, 979–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ostman A., Böhmer F. D. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ostman A., Hellberg C., Böhmer F. D. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 307–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Müller J. P., Schönherr C., Markova B., Bauer R., Stocking C., Böhmer F. D. (2008) Leukemia 22, 1945–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heiss E., Masson K., Sundberg C., Pedersen M., Sun J., Bengtsson S., Rönnstrand L. (2006) Blood 108, 1542–1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heyworth C. M., Spooncer E. (1992) in Haemopoiesis: A Practical Approach (Molineux G., Testa N. G. eds) pp. 37–53, Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jandt E., Denner K., Kovalenko M., Ostman A., Böhmer F. D. (2003) Oncogene 22, 4175–4185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kitamura T., Koshino Y., Shibata F., Oki T., Nakajima H., Nosaka T., Kumagai H. (2003) Exp. Hematol. 31, 1007–1014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petermann A., Haase D., Wetzel A., Balavenkatraman K. K., Tenev T., Gührs K. H., Friedrich S., Nakamura M., Mawrin C., Böhmer F. D. (December 27, 2010) Brain Pathol. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00464.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gross S., Knebel A., Tenev T., Neininger A., Gaestel M., Herrlich P., Böhmer F. D. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26378–26386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dull T., Zufferey R., Kelly M., Mandel R. J., Nguyen M., Trono D., Naldini L. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 8463–8471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beyer W. R., Westphal M., Ostertag W., von Laer D. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 1488–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mosmann T. (1983) J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grundler R., Miething C., Thiede C., Peschel C., Duyster J. (2005) Blood 105, 4792–4799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mizuki M., Schwable J., Steur C., Choudhary C., Agrawal S., Sargin B., Steffen B., Matsumura I., Kanakura Y., Böhmer F. D., Müller-Tidow C., Berdel W. E., Serve H. (2003) Blood 101, 3164–3173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choudhary C., Schwäble J., Brandts C., Tickenbrock L., Sargin B., Kindler T., Fischer T., Berdel W. E., Müller-Tidow C., Serve H. (2005) Blood 106, 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sacco F., Tinti M., Palma A., Ferrari E., Nardozza A. P., Hooft van Huijsduijnen R., Takahashi T., Castagnoli L., Cesareni G. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 22048–22058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rocnik J. L., Okabe R., Yu J. C., Lee B. H., Giese N., Schenkein D. P., Gilliland D. G. (2006) Blood 108, 1339–1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grundler R., Thiede C., Miething C., Steudel C., Peschel C., Duyster J. (2003) Blood 102, 646–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flint A. J., Tiganis T., Barford D., Tonks N. K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 1680–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Palka H. L., Park M., Tonks N. K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5728–5735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Berset T. A., Hoier E. F., Hajnal A. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1328–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tarcic G., Boguslavsky S. K., Wakim J., Kiuchi T., Liu A., Reinitz F., Nathanson D., Takahashi T., Mischel P. S., Ng T., Yarden Y. (2009) Curr. Biol. 19, 1788–1798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kappert K., Paulsson J., Sparwel J., Leppänen O., Hellberg C., Ostman A., Micke P. (2007) FASEB J. 21, 523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chabot C., Spring K., Gratton J. P., Elchebly M., Royal I. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 241–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grazia Lampugnani M., Zanetti A., Corada M., Takahashi T., Balconi G., Breviario F., Orsenigo F., Cattelino A., Kemler R., Daniel T. O., Dejana E. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161, 793–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fröhling S., Scholl C., Levine R. L., Loriaux M., Boggon T. J., Bernard O. A., Berger R., Döhner H., Döhner K., Ebert B. L., Teckie S., Golub T. R., Jiang J., Schittenhelm M. M., Lee B. H., Griffin J. D., Stone R. M., Heinrich M. C., Deininger M. W., Druker B. J., Gilliland D. G. (2007) Cancer Cell 12, 501–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vempati S., Reindl C., Wolf U., Kern R., Petropoulos K., Naidu V. M., Buske C., Hiddemann W., Kohl T. M., Spiekermann K. (2008) Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 4437–4445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Griffith J., Black J., Faerman C., Swenson L., Wynn M., Lu F., Lippke J., Saxena K. (2004) Mol. Cell 13, 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Persson C., Sävenhed C., Bourdeau A., Tremblay M. L., Markova B., Böhmer F. D., Haj F. G., Neel B. G., Elson A., Heldin C. H., Rönnstrand L., Ostman A., Hellberg C. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2190–2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhu J. W., Brdicka T., Katsumoto T. R., Lin J., Weiss A. (2008) Immunity 28, 183–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.