Abstract

Although the secreted phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) family has been generally thought to participate in pathologic events such as inflammation and atherosclerosis, relatively high and constitutive expression of group X sPLA2 (sPLA2-X) in restricted sites such as reproductive organs, the gastrointestinal tract, and peripheral neurons raises a question as to the roles played by this enzyme in the physiology of reproduction, digestion, and the nervous system. Herein we used mice with gene disruption or transgenic overexpression of sPLA2-X to clarify the homeostatic functions of this enzyme at these locations. Our results suggest that sPLA2-X regulates 1) the fertility of spermatozoa, not oocytes, beyond the step of flagellar motility, 2) gastrointestinal phospholipid digestion, perturbation of which is eventually linked to delayed onset of a lean phenotype with reduced adiposity, decreased plasma leptin, and improved muscle insulin tolerance, and 3) neuritogenesis of dorsal root ganglia and the duration of peripheral pain nociception. Thus, besides its inflammatory action proposed previously, sPLA2-X participates in physiologic processes including male fertility, gastrointestinal phospholipid digestion linked to adiposity, and neuronal outgrowth and sensing.

Keywords: Arachidonic Acid, Eicosanoid, Mouse, Phospholipase A, Phospholipid

Introduction

The human and mouse genomes contain more than 30 genes encoding phospholipase A2 (PLA2)3 or related enzymes that liberate fatty acids and lysophospholipids from membrane phospholipids. About one-third of these genes belong to the secreted PLA2 (sPLA2) family, which contains typically disulfide-rich, low molecular weight (typically 14–18 kDa) enzymes with strict Ca2+ dependence and a His-Asp catalytic dyad (1, 2). Although potential actions of sPLA2s on phospholipid vesicles or cellular membranes have been demonstrated in a number of in vitro studies and, hence, these enzymes have been implicated in several biological processes such as inflammation, host defense, and atherosclerosis (1, 2), the precise in vivo functions of individual enzymes, including their modes of action, expression, target membranes on which they act, and pathophysiological outcomes still remain largely obscure.

Recent studies employing transgenic (gain-of-function) and knock-out (loss-of-function) mice have provided some important insights into the pathophysiological roles of several sPLA2s in vivo. sPLA2-IB, a pancreatic sPLA2, is secreted from the pancreas into the duodenum to digest dietary and biliary phosphatidylcholine (PC). Deletion of its gene in mice (Pla2g1b−/−) reduces the intestinal digestion of PC and thereby absorption of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), resulting in protection from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance (3, 4). sPLA2-IIA, often referred to as an inflammatory sPLA2, is induced by proinflammatory stimuli, and its serum level is well correlated with the severity of inflammatory and cardiovascular diseases (1, 2). Recent studies using Pla2g2a-deficient and transgenic mice have provided evidence for the proinflammatory roles of sPLA2-IIA in inflammatory arthritis (5) and atherosclerosis (6). sPLA2-IIA also efficiently degrades bacterial membranes, thereby contributing to the first line of anti-bacterial defense (7, 8). sPLA2-V, which is expressed in macrophages, is involved in zymosan-elicited eicosanoid synthesis (9), fungal killing by facilitating phagocytosis (10), and atherosclerosis by hydrolyzing lipoprotein-associated PC in the arterial wall (11). The enzyme is also expressed in the bronchial epithelium and participates in inflammatory conditions of the airway, such as asthma and acute respiratory distress syndrome, through augmentation of lipid mediator synthesis or excessive degradation of pulmonary surfactant PC (12, 13). On the other hand, Pla2g5−/− mice exhibit accentuated inflammatory arthritis because of impaired phagocytotic clearance of immune complexes by macrophages, revealing an unexpected anti-inflammatory aspect of sPLA2-V (5). sPLA2-III, an atypical sPLA2, is secreted from luminal epithelial cells in the epididymis, and deletion of its gene (Pla2g3−/−) hampers epididymal sperm maturation due to perturbed phospholipid remodeling in the sperm membrane (14). Transgenic overexpression of sPLA2-III in mice (Pla2g3tg/+) causes systemic inflammation, probably through augmentation of lipid mediator production (15), and exacerbates atherosclerosis through systemic production of pro-atherosclerotic lipoprotein particles (16).

Among the sPLA2 members, sPLA2-X has recently attracted attention because it is the isoform that binds tightly to PC-rich membranes (e.g. outer plasma membrane and lipoproteins) in comparison to other mammalian sPLA2s (17–22). Forcible transfection or exogenous addition of sPLA2-X to cultured cells, even in the absence of other inflammatory stimuli, triggers the release of arachidonic acid and its metabolites such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (17, 18). Because of this potent in vitro action, most investigators in this area of research have focused on the proinflammatory role of sPLA2-X through production of lipid mediators. Indeed, studies using mice with targeted disruption of its gene (Pla2g10−/−) have highlighted the roles of sPLA2-X in asthma and ischemic myocardial injury, where the enzyme appears to regulate disease-associated eicosanoid synthesis (21, 22). Hydrolysis of lipoprotein-bound PC by sPLA2-X allows the production of more atherogenic small-dense lipoprotein particles that facilitate the formation of foam cells from macrophages (19). In line with its proinflammatory and proatherogenic potential, deficiency of sPLA2-X reduces the incidence of angiotensin-II-induced atherosclerosis and aneurysm in apoE−/− mice (20).

It is notable that under physiological conditions, sPLA2-X is expressed in the testis and gastrointestinal tract at much higher levels than in other tissues (23, 24). sPLA2-X is also uniquely located in peripheral neuronal fibers in several tissues and exerts a neuritogenic action on cultured neuronal cells in vitro (25, 26). However, the physiological functions of sPLA2-X at these locations in vivo have remained unresolved. Our recent finding that spermatozoa from Pla2g10−/− mice display reduced fertility has provided new insight into the unexplored physiological function of sPLA2-X as a regulator of male reproduction (27). In the present study, by utilizing mice with knock-out or transgenic overexpression of sPLA2-X, we have obtained evidence that sPLA2-X does exert physiological roles at these sites. First, although sPLA2-X is expressed in both gametes, it participates in fertility only in spermatozoa, acting beyond the step of flagellar motility. Second, Pla2g10−/− mice maintained on a chow diet were found to display a lean phenotype as they aged, likely because phospholipid digestion in the gut was reduced in these mice. Third, neuritogenesis of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) explants ex vivo and peripheral pain nociception in vivo were reduced in Pla2g10−/− mice and conversely augmented in Pla2g10tg/+ mice relative to those in control mice, suggesting a neuronal function of sPLA2-X.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

All mice were housed in climate-controlled (23 °C) specific pathogen-free facilities with a 12-h light-dark cycle, with free access to standard laboratory food (CE2; Laboratory Diet) (CLEA Japan) and water. Mice overexpressing human sPLA2-X (Pla2g10tg/+) (13) and mice deficient in sPLA2-X (Pla2g10−/−) (22), sPLA2-V (Pla2g5−/−) (9), or microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) (Ptges−/−) (28), which were backcrossed on a C57BL/6 genetic background (n > 12), were described previously. All procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science and Showa University in accordance with the Standards Relating to the Care and Management of Experimental Animals in Japan.

PCR Genotyping

Approximately 0.1 μg of genomic DNA were obtained from tail biopsy of mice. For genotyping of Pla2g10tg/+ mice, the genomic DNA was subjected to PCR amplification with the GeneAmp Fast PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and a set of primers 5′-ggcctccaggatattacgtgtgc-3′ and 5′-tcagtcacacttgggcgagtcc-3′ obtained from Sigma Genosys (Japan). For genotyping of Pla2g10−/− mice, combined sets of sense primers 5′-gaactaatgtcgacaactgagaga-3′ or 5′-ccgcttgggtggagaggctattc-3′ and antisense primers 5′-cagggtgctggaactaggtgttg-3′ or 5′-gcaaggtgagatgacaggagatc-3′ were used. The PCR conditions were 95 °C for 10 s and then 35 cycles of 95 °C for 0 s and 65 °C for 1 min on Applied Biosystems 9800 Fast thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). The PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Synthesis of cDNA was performed using 0.5 μg of total RNA from cells and tissues and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase, according to the manufacturer's instructions supplied with the RNA PCR kit (Takara Biomedicals). Subsequent amplification of the cDNA fragments was performed using 0.5 μl of the reverse-transcribed mixture as a template with specific primers (Fasmac) for Pla2g10 (a set of 23-bp oligonucleotide primers corresponding to the 5′- and 3′-nucleotide sequences of its open reading frame (29, 30)) and galanin (Gal) (5′-atggccagaggcagcgttatcc-3′ and 5′-ccattatagtgcggacaatgttg-3′). The PCR conditions were 94 °C for 30 s followed by 30 cycles of amplification at 94 °C for 5 s and 68 °C for 4 min using the Advantage cDNA polymerase mix (Clontech). Amplification of β-actin (Actb) was performed as described previously (29, 30). The PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide. For quantitative RT-PCR, PCR reactions were performed on the ABI7700 Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan Gene Expression System with Pla2g10 and Gapdh TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems).

Microarray Gene Profiling

Total RNA from DRG of fetal Pla2g10−/− and Pla2g10+/+ mice (E12.5) was purified using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cRNA targets were synthesized and hybridized with Whole Mouse Genome Oligo Microarray according to the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent). The array slides were scanned with a Laser Scanner GenePix 4000B (Molecular Devices) using appropriate gains on the photomultiplier to obtain the highest intensity without saturation. Gene expression values were background-corrected and normalized using the GenePix software (Molecular Devices).

Isolation and Culture of Mouse DRG Explants

Mouse DRG explants were prepared from E12.5 of C57BL/6 mice as described previously (25). In brief, mouse fetuses were incised longitudinally from the upper cervical vertebrae to the tail along the spinal cord. The spinal cord sections were separated and removed, and DRG neurons attached to the spinal cord were picked up and harvested. DRG explants were then cultured for up to 36 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co.) supplemented with appropriate concentrations of nerve growth factor (NGF) in poly-d-lysine-coated glass-bottom dishes (MatTek) precoated with 20 μg/ml laminin (Biochemical Technologies).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, mounted on glass slides, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in ethanol with increasing concentrations of water. The tissue sections (4 μm thick) were incubated with Target Retrieval Solution (DAKO) as required, incubated for 10 min with 3% (v/v) H2O2, washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min each, incubated with 5% (w/v) skim milk in PBS for 30 min, washed 3 times with PBS for 5 min each, and incubated with rabbit antiserum for human or mouse sPLA2-V and -X (30) or preimmune serum at 1:500 dilution in PBS overnight at 4 °C. The sections were then treated with a CSA (catalyzed signal-amplified) system staining kit (DAKO) with diaminobenzidine substrate followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin and eosin. The cell type was identified from conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining of serial sections adjacent to the specimen used for immunohistochemistry. Human tissue sections were obtained by surgery at Toho University (Tokyo, Japan) after approval by the ethical committee of the Faculty and informed consent from the patient.

Confocal Laser Microscopy

Paraffin-embedded mouse DRG sections were sequentially treated with 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in PBS (blocking solution) for 1 h at room temperature, with rabbit anti-mouse sPLA2-X antibody (30), mouse anti-neurofilament 200 (NF200) antibody (an A-fiber marker; Sigma), or goat anti-peripherin antibody (a C-fiber marker; Santa Cruz) at a 1:200 dilution in PBS containing 1% albumin at 4 °C overnight, and then with appropriate combinations of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), Cy3- or Cy5-conjugated, species-specific anti-rabbit, mouse, or goat IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at a 1:200 dilution for 1 h at room temperature in PBS containing 1% albumin with 3 washes with PBS at each interval. For double immunostaining of DRG explants for sPLA2-X and βIII tubulin, DRG explants on laminin-coated dishes were fixed with blocking solution for 1 h, treated with rabbit anti-mouse sPLA2-X antibody and mouse anti-βIII tubulin antibody (Chemicon) at 1:200 dilution in blocking solution for 2 h, and then with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit and Alexa546-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibodies (Molecular Probes) at a 1:200 dilution in blocking solution for 2 h with 3 washes in each interval. After 6 washes with PBS, the fluorescent signal was visualized with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). We ensured lack of cross-reactivity of fluorochrome-labeled secondary antibodies with primary antibodies from species to which they were not raised.

In Vitro Fertilization

Female mice (10 weeks old) were injected intraperitoneally with 7.5 IU or pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (Asuka Pharmacy) followed 48 h later with 7.5 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (Asuka Pharmacy). Oviducts were collected 13 h later, and the oocyte cumulus complexes were placed in 100 μl of HTF medium (ARK Resource) in a 60-mm culture dish (Iwaki), and droplets were covered by embryo-tested mineral oil (Nakarai Tesque). Spermatozoa collected from the cauda epididymidis were allowed to swim into 50 μl of HTF medium, aspirated, incubated in 200 μl of HTF medium for 60 min at 37 °C to permit capacitation, diluted, and added to oocyte droplets to achieve a concentration of 200 spermatozoa/μl. After the spermatozoa and oocytes were preincubated for 6 h at 37 °C, the oocytes were washed and cultured for 24 h before examination of oocyte fertilization, as demonstrated by the presence of a second polar body and two pronuclei, one near a sperm tail.

Sperm Motility

Male mice (8 weeks old) were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and a tubule segment was dissected from the cauda epididymidis. The luminal sperm were allowed to disperse in 200 μl of HTF medium (ARK Resource) for 10 min. After the tissue had been removed, the sperm were allowed to capacitate for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in air. A 5-μl aliquot of the sperm suspension was then placed in a counting chamber (Standard Count; Laje) for assessment of motility by computer-assisted analysis using a Sperm Motility Analysis System (KAGA Electronics). The parameters measured were the percentage of motile sperm cells, vigor of movement (curvilinear velocity), speed of forward progression (straight-line velocity), amplitude of lateral head displacement, beat cross-frequency, and linearity of swim path.

Measurement of Serum Biomedical Markers

With or without an overnight fast, mice were anesthetized, and blood samples were immediately collected by cardiac puncture. Sera were applied to the clinical chemistry analyzer VetScan with V-DPP rotors (Abaxis). Serum concentrations of insulin, adiponectin, leptin, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and corticosterone were quantified using ultrasensitive mouse insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Mercodia), Quantikine mouse adiponectin/Acrp30 and leptin immunoassay kits (R&D Systems), mouse IGF-I ELISA kit (R&D Systems) and corticosterone ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical), respectively.

Western Blotting

Tissues (100 μg) were soaked in 500 μl of 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 5 mm EDTA, 10 μg/ml leupeptin (Sigma), 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma), 1 mm Na3VO4, and 0.1 mm Na2MoO4 and then homogenized with a Polytron homogenizer. The homogenates (20 μg of protein equivalents) were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10% gels under reducing conditions with 2-mercaptoethanol. Protein concentrations in the samples were determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) using bovine serum albumin (Sigma) as a standard. The separated proteins were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell) with a semidry blotter (Transblot SD) (Bio-Rad). After blocking with 5% (w/v) skim milk in TBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBS-T), the membranes were probed with rabbit antibody against Akt or phosphorylated Akt (Ser-473; Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution in TBS-T for 2 h followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Zymed Laboratories Inc.) at a 1:5000 dilution in TBS-T for 2 h and then visualized using the ECL Western blot system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Electrospray Ionization/Mass Spectrometry (ESI/MS)

Lipids were extracted from samples with the addition of PC28:0 as an internal standard (1 nmol of internal standard per 1 mg of protein equivalents). The ESI-MS of phospholipids were performed using a 4000Q TRAP, quadrupole-linear ion trap hybrid mass spectrometer (MDS Sciex; Applied Biosystems) with a UltiMate 3000 nano/cap/micro-liquid chromatography (LC) system (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA) combined with HTS PAL autosampler (CTC Analytics AG, Zwingen, Switzerland). Phospholipids were subjected directly to ESI-MS analysis by flow injection; typically, 3 μl (3 nmol of phosphorus equivalent) of sample was applied. The mobile phase composition was acetonitrile/methanol/water (6:7:2) (plus 0.1% ammonium formate (pH 6.8)) at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. The scan range of the instrument was set at m/z 200–1000 at a scan speed of 1000 Da/s. The trap fill-time was set at 1 ms in the positive ion mode and at 5 ms in the negative ion mode. The ion spray voltage was set at 5500 V in the positive ion mode and at −4500 V in the negative ion mode. Nitrogen was used as curtain gas (setting of 10, arbitrary units) and as collision gas (set to “high”). Detailed procedure for ESI-MS was described previously (14, 16).

Quantification of Eicosanoids

Mouse spinal cords were dissected, immediately frozen under liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until use. The tissues were crushed to powder with an SK-100 mill (Tokken) without thawing, and lipids were extracted using 1 ml of ethanol with a mixture of deuterium-labeled internal eicosanoid standards. The extracts were further cleaned up with Oasis HLB extraction cartridges (30 mg, Waters), and eicosanoids in the homogenates were quantified as described (31). Briefly, a TSQ-7000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization ion source (Thermo Electron) was operated in negative electrospray ionization and selected reaction monitoring mode. A reverse-phase high performance LC system consisting of four LC-10A pumps and a CTO-10 column oven (Shimadzu), an electrically controlled 6-port switching valve (Valco), and a 3033 HTS autosampler (Shiseido) was connected to the MS instrument and used for rapid resolution of PGs with a Capcell Pak C18 MGS3 (1 × 100 mm) column (Shiseido) within 10 min. For accurate quantification, an internal standard method was used. As internal standards, a mixture of deuterium-labeled eicosanoids was used. Automated peak detection, calibration, and calculation were carried out using the Xcalibur 1.2 software package (Thermo Electron).

Glucose and Insulin Tolerance Tests

After overnight fasting, glucose (0.75 mg glucose/g body weight) (Wako) or insulin (0.75 mIU/g of body weight) (Sigma) in saline was intraperitoneally injected into mice. Blood glucose concentrations were monitored at various time intervals using a Medisafe-Mini blood glucose monitoring system (Terumo).

Computed Tomographic (CT) Analysis

Mice were anesthetized with Nembutal (0.5 mg/g of body weight) (Dainippon Sumitomo Pharmaceutical), and their adiposity and bone density were analyzed using a micro-CT system (Latheta LCT-100, Aloka).

Separation of Lipoproteins

Lipoproteins in mouse sera (100 μl per run after 1:10 dilution) were separated by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on TSK gel Lipopropak XL (TOSOH) with TSK Eluent PL1 (TOSOH) as a running buffer at a flow rate of 0.35 ml/min. Total cholesterol and phospholipid levels were determined with Determinar TC2 (Kyowa Medex) and Phospholipid C Test (Wako), respectively.

Adipocyte Differentiation

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), obtained from E13.5 fetus according to a standard protocol, were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 1 mm sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), 0.1 mm nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), and 100 mg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma). After reaching a confluence, the cells were stimulated for 2 days with an adipocyte differentiation mixture comprising 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), 1 μm dexamethasone (Sigma), and 0.5 μm isobutylmethylxanthine (Sigma) and then for 1 week with 10 μg/ml insulin, with replacement with fresh medium every 2 days. The cells were fixed in 10% formalin in PBS for 10 min and washed with PBS. Saturated oil red O solution was prepared by dilution of 3 mg/ml oil red O in 60% isopropyl alcohol followed by filtration through a 0.45-μm filter. After equilibration in 60% isopropyl alcohol, the cells were stained in saturated oil red O. After a brief wash with 60% isopropyl alcohol, the cells were equilibrated in PBS. Mouse preadipocytic 3T3-L1 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were infected with lentivirus for sPLA2-X or control virus followed by selection with Blasticidin, as described previously (29). Stable clones thus obtained were subjected to adipogenesis as above.

Pain Tests

The acetic writhing reaction was induced in mice by intraperitoneal injection of 0.9% or 0.4% (v/v) acetic acid solution into mice at a dose of 5 ml/kg, as described previously (28). The number of writhing responses was counted every 5 min or after 30 min according to the experimental settings. In the hot plate test, mice were placed on a hot/cold plate (Ugo Basile) at 52.5 °C, and the latency of licking, standing, and jumping behavior was monitored.

Statistics

Data were statistically evaluated by unpaired Student's t test at a significance level of p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Expression of Pla2g10 mRNA in Mice

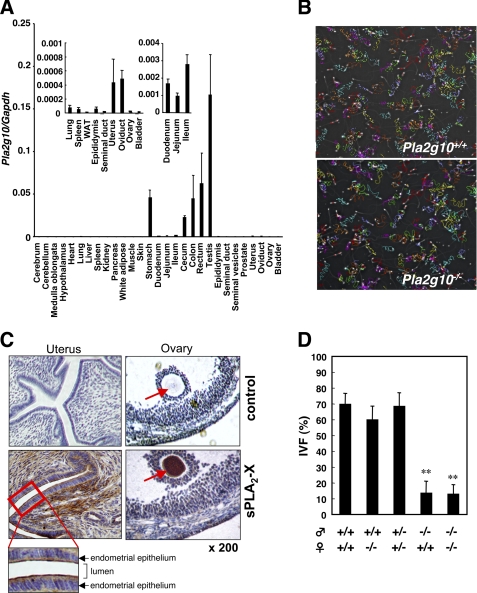

It has been believed that sPLA2-X is expressed in various tissues and cells, with the most intensive focus on inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and macrophages (18, 21, 22, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33). However, several studies employing more quantitative methods have shown that sPLA2-X is expressed in the testis and gastrointestinal tract much more abundantly than in immune organs (23, 24). To ascertain the precise tissue distribution of sPLA2-X, we performed quantitative RT-PCR using a wide range of mouse tissues. As shown in Fig. 1A, Pla2g10 mRNA was most abundantly expressed in testis followed by stomach and colon and then by small intestine of adult C57BL/6 mice. It was also detectable at significant levels in male and female genital organs including epididymis, uterus, and oviduct (Fig. 1A, inset). Relatively low but significant expression of sPLA2-X in lung and spleen may reflect that the enzyme is localized only in specific cell populations among various cell types, such as airway epithelial cells (21), neutrophils (22), and peripheral neurons (25). In other tissues its expression was rather low or not detected at all (Fig. 1A). This distribution pattern is essentially consistent with some previous reports (23, 24, 33) as well as public databases for the expression profile of Pla2g10. Therefore, the recognition that sPLA2-X is expressed in a wide variety of tissues could be misleading, and its abundant expression in the genital and gastrointestinal organs suggests its specific roles at these locations.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of sPLA2-X in mouse tissues and its role in fertilization. A, expression of Pla2g10 mRNA in various tissues of 16-week-old C57BL/6 mice was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR. The expression levels of Pla2g10 mRNA were normalized with those of Gapdh mRNA. Inset, expression levels of Pla2g10 mRNA in several tissues are magnified. Values are the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). WAT, white adipose tissue. B, sperm motility is shown. Trails of sperm from Pla2g10+/+ (upper panel) and Pla2g10−/− (lowen panel) mice were analyzed using a Sperm Motility Analysis System (original magnification, ×100). C, immunohistochemistry of sPLA2-X in mouse female reproductive organs is shown. Uterus and ovary were stained with anti-sPLA2-X or control antibody. D, impaired IVF of Pla2g10−/− sperm but not oocytes is shown. Fertilization efficiency was evaluated as the number of 2-cell stage eggs relative to the total number at 24 h (mean ± S.D. (n = 3∼4); **, p < 0.01).

Reduced Fertility of Pla2g10−/− Mice

We have recently shown that spermatozoa of Pla2g10−/− mice display partial reduction of their fertilization capacity in the IVF assay due to a decreased premature acrosome reaction, a process that eliminates a suboptimal sperm population from the pool available for fertilization (27). However, several points remain unresolved. First, it is unclear whether, in fact, a step before the acrosome reaction is defective in Pla2g10−/− mice. This point seems important, as spermatozoa from mice lacking another sPLA2, Pla2g3−/−, have a severe defect of sperm motility and, thereby, fertility (14). Second, breeding records for male Pla2g10−/− mice reveal no decrease of litter size when crossed with wild-type females, whereas reduced fertility is evident upon crossing with Pla2g10−/− females (27), suggesting that sPLA2-X is supplied from the female genital tract and may compensate for the absence of sPLA2-X in sperm.

To address these issues, we first assessed the motility of cauda epididymal spermatozoa of Pla2g10−/− mice by computer-assisted sperm analysis. This revealed that all motility parameters of Pla2g10−/− sperm, including straight-line and curvilinear velocities and amplitude, were similar to those of control sperm (Fig. 1B and supplemental Table S1), thus ruling out the possibility that Pla2g10−/− sperm have a defect of capacitated flagellar movement. This finding together with the fact that the number (supplemental Table S1) and morphology (27) of cauda epididymal spermatozoa were normal in Pla2g10−/− mice indicates that testicular spermatogenesis and epididymal sperm maturation are not impaired in these mice. Next, we carried out immunohistochemistry of the genital tract of 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice using anti-mouse sPLA2-X antibody, as there has been no detailed analysis of sPLA2-X localization and function in female reproductive organs. In the uterus (Fig. 1C) and oviduct (data not shown), the apical rather than the basolateral side of endometrial epithelial cells as well as the interstitium beneath the epithelium were positively stained with anti-sPLA2-X antibody but not with control antibody. Considering that exogenous sPLA2-X can powerfully boost the spontaneous acrosome reaction of spermatozoa (27), it is tempting to speculate that sPLA2-X secreted from the endometrial epithelium into the lumen may assist in a paracrine manner the spontaneous acrosome reaction of sperm cells passing through the uterine duct. Notably, ovarian oocytes, but not surrounding follicular cells and cumulus granulosa cells, were intensely stained with anti-sPLA2-X, but not control, antibody (Fig. 1C). To assess whether sPLA2-X in oocytes would contribute to fertility, we performed an IVF assay in which oocytes from Pla2g10+/+ or Pla2g10−/− females were inseminated with spermatozoa from Pla2g10+/+ or Pla2g10−/− males. As shown in Fig. 1D, although the fertility of Pla2g10−/− sperm was markedly impaired, that of Pla2g10−/− oocytes was nearly identical to that of Pla2g10+/+ oocytes. Thus, at least under the conditions we employed, impaired IVF could be ascribed mainly to the absence of sPLA2-X in sperm cells but not in oocytes.

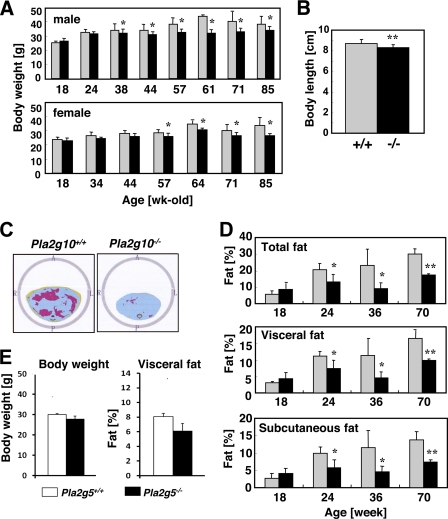

A Lean Phenotype of Aged Pla2g10−/− Mice Reveals a Digestive Role of sPLA2-X in the Gut

A recent report has shown that sPLA2-X is expressed in adipose tissue and that Pla2g10−/− mice fed a diet containing 6.2% caloric fat exhibit increased adiposity (32), although our data shown in Fig. 1A indicate that the expression of sPLA2-X in adipose tissue is very low. In contrast, another study has reported that Pla2g10−/− mice have normal body weight (22). Under a chow diet condition (fat 4.8%; CLEA rodent diet CE-2), we found that the body weight of Pla2g10−/− mice did not differ appreciably from that of wild-type mice until 9∼12 months of age (similarly to the latter study (22)), but subsequently (after the age of 38 weeks for males and 57 weeks for females) the null mice showed a propensity for less weight gain than did the control mice (Fig. 2A). The body length of Pla2g10−/− mice was also slightly less than that of Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 2B), whereas bone density did not differ significantly between the genotypes (supplemental Fig. S1). CT analysis demonstrated deposits of visceral and subcutaneous fat in 1-year-old Pla2g10+/+ mice, whereas age-matched Pla2g10−/− mice showed markedly reduced adiposity at both sites (Fig. 2C). In male Pla2g10−/− mice, the decreases in total, visceral, and subcutaneous fat mass were already evident as early as 24 weeks (Fig. 2D), at which time the change in body weight had not yet become apparent (Fig. 2A). A similar trend was observed in female Pla2g10−/− mice (data not shown). In comparison, body weight and adiposity were similar between 1-year-old Pla2g5−/− (which lack sPLA2-V) and Pla2g5+/+ mice (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 2.

Age-associated lean phenotype of Pla2g10−/− mice. A, monitoring of body weight of male and female Pla2g10+/+ (gray bars) and Pla2g10−/− (solid bars) mice during aging is shown. B, body length of 70-week-old male Pla2g10+/+ (gray bars) and Pla2g10−/− (solid bars) mice (mean ± S.D., n = 8; **, p < 0.01) is shown. C, abdominal CT scanning of 70-week-old male WT and Pla2g10−/− mice is shown. Red and yellow areas indicate visceral and subcutaneous fat, respectively. D, monitoring of total, visceral, and subcutaneous fat contents in male Pla2g10+/+ (gray bars) and Pla2g10−/− (solid bars) mice during aging is shown. Values are the mean ± S.D. (n = 6∼8; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). E, body weight and visceral adiposity of 62-week-old Pla2g5+/+ and Pla2g5−/− mice (mean ± S.D., n = 5) are shown.

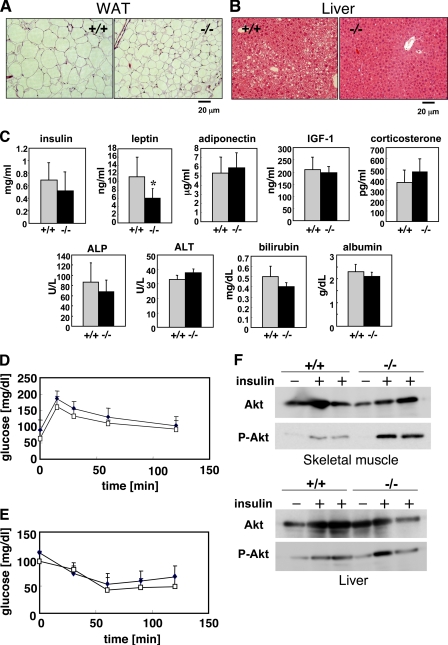

In agreement with these observations, histological examination showed that individual adipocytes in epigonadal fat pads were smaller in 1-year-old male Pla2g10−/− mice than in Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 3A). In addition, age-associated lipid deposition in the liver was less obvious in Pla2g10−/− mice than in Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 3B). Thus, the deficiency of sPLA2-X unexpectedly protected the mice from age-related adiposity and fatty liver. Food intake (data not shown) and energy expenditures as assessed by locomotion and respiration quotient (supplemental Fig. S2) were indistinguishable between Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice. Fasting serum insulin levels did not differ significantly between the genotypes (Fig. 3C), suggesting normal insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells in 1-year-old Pla2g10−/− mice. Of the two adipokines, leptin and adiponectin, the serum concentration of the former was significantly lower in Pla2g10−/− mice than in Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 3C), consistent with lower adiposity in the null mice. Neither IGF-I nor corticosterone in serum differed significantly between the genotypes (Fig. 3C), implying that the reduced body size and adiposity of Pla2g10−/− mice might not be due to imbalance of the growth hormone or glucocorticoid signaling. Several serum biomarkers for liver function, including alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, bilirubin, and albumin, were within the normal ranges in Pla2g10−/− mice (Fig. 3C). Also, serum ions and biomarkers of pancreatic (amylase) and renal (creatinine and nitrogen urea) function did not differ between the genotypes (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Histology of adipose tissue and liver and serum levels of various biological markers and insulin sensitivity in aged Pla2g10−/− mice. A and B, histology of white adipose tissue (WAT; A) and liver (B) of 72-week-old Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice is shown. C, serum levels of insulin, leptin, adiponectin, IGF-1, corticosterone, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), bilirubin, and albumin (mean ± S.D., n = 6∼8; *, p < 0.05) are shown. D, shown is a glucose tolerance test. After being fasted for 16 h, 67∼72-week-old Pla2g10+/+ (filled symbols) and Pla2g10−/− (open symbols) mice were administered 0.75 mg/kg body weight glucose intraperitoneally, and the levels of blood glucose were monitored at the indicated times (mean ± S.D., n = 7). E, shown is an insulin tolerance test. After being fasted for 16 h, 67∼72-week-old Pla2g10+/+ (filled symbols) and Pla2g10−/− (open symbols) mice were administered 0.75 mIU/kg body weight insulin intraperitoneally, and the levels of blood glucose were monitored at the indicated times (mean ± S.D., n = 8). F, 72-week-old Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally with insulin (+) or saline (−), and then 5 min later femoral muscle (upper panel) and liver (lower panel) homogenates were subjected to Western blotting with antibodies against Akt and its phosphorylated form (P-Akt).

We then performed an insulin tolerance test (Fig. 3D) and a glucose tolerance test (Fig. 3E) after an overnight fast using 1-year-old Pla2g10−/− mice and littermate controls. Although insulin sensitivity (Fig. 3D) and glucose clearance (Fig. 3E) did not differ significantly between the two groups, we observed a propensity for slightly lower plasma glucose levels in Pla2g10−/− mice than in Pla2g10+/+ mice in both tests, suggesting a better insulin sensitivity in the null mice than in the wild-type mice. Nonetheless, because of the difficulty in observing a clear difference in the insulin sensitivity of the animals kept on a chow diet by these methods, we evaluated the insulin sensitivity of skeletal muscle and liver, two major sites of insulin action, by detecting the phosphorylation of Akt, which lies downstream of the insulin signaling pathway. The animals were injected intraperitoneally with insulin, and then 5 min later homogenates of the skeletal muscle and liver were subjected to immunoblotting using an antibody against a phosphorylated form of Akt (P-Akt), employing immunoblotting with an antibody against total Akt protein as a reference. Notably, although the level of P-Akt was elevated in the skeletal muscle of both genotypes after insulin treatment, the degree of phosphorylation was apparently higher in Pla2g10−/− mice than in Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 3F). In contrast, the levels of P-Akt in the liver were comparable between the genotypes (Fig. 3F). Thus, the skeletal muscle in Pla2g10−/− mice showed better insulin sensitivity than that in wild-type mice, which may contribute at least partly to the reduced adiposity seen in Pla2g10−/− mice.

Because sPLA2-X is capable of potently hydrolyzing PC in plasma lipoproteins in vitro (19, 20) and because alteration of lipid transport by lipoproteins among tissues could affect adiposity, we next examined whether the levels of plasma lipoproteins were altered in Pla2g10−/− mice. The elution profiles of lipoproteins on HPLC, as monitored by total phospholipids and cholesterol, were similar between 1-year-old Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice (supplemental Fig. S3A). In agreement, the serum levels of total cholesterol and phospholipids in both genotypes were identical (supplemental Fig. S3B). Fractionation of individual lipoprotein components (chylomicron, VLDL, LDL, and HDL) by HPLC revealed no appreciable difference between the genotypes (supplemental Fig. S3C). Thus, it is unlikely that endogenous sPLA2-X affects lipid partitioning among tissues by altering plasma lipoprotein metabolism under physiological conditions.

To assess whether or not sPLA2-X would affect adipogenesis, we performed in vitro adipocyte differentiation of MEF from Pla2g10−/− mice or littermate wild-type mice. However, we found no difference in the frequency of oil red O-positive cells, and importantly, we failed to detect any expression of endogenous sPLA2-X in the wild-type MEF culture by RT-PCR (data not shown). We then examined the adipogenesis of MEF from mice with transgenic overexpression of sPLA2-X (Pla2g10tg/+) and found that this was increased in comparison with MEF from control mice (supplemental Fig. S4B). On the other hand, artificial overexpression of sPLA2-X in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes prevented adipogenesis (supplemental Fig. S4A), in agreement with a recent report proposing that polyunsaturated fatty acids released by sPLA2-X prevent adipogenesis by repressing liver X receptor activation (32). These results suggest that sPLA2-X can exert either a positive or a negative effect on adipogenesis in the context of the types and/or differentiation stages of adipocytes or the expression levels of sPLA2-X. Importantly, the expression level of Pla2g10 mRNA in white adipose tissue of adult mice was very low in comparison with that in reproductive and gastrointestinal tissues (Fig. 1A). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that a trace level of sPLA2-X can function in an adipose niche, as has been reported recently (32), it is more likely that the reduced adiposity of Pla2g10−/− mice observed here may be attributable to another causative factor(s).

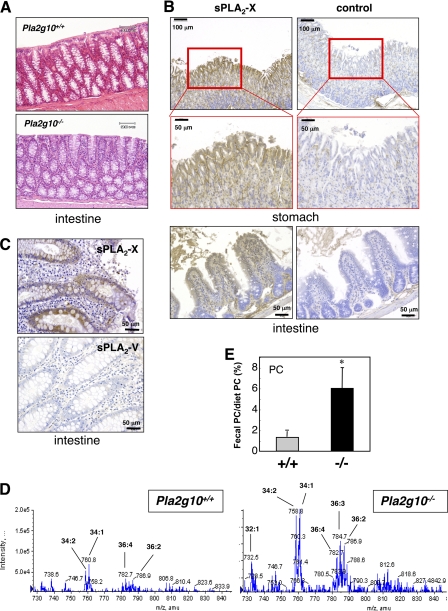

Although the expression of endogenous Pla2g10 mRNA was minimal in adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle, which are major sites involved in the metabolic control of lipids, it was expressed abundantly in the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 1A). Because reduced absorption of nutrients in the gastrointestinal tract could affect adiposity, we next investigated whether aged Pla2g10−/− mice might have certain gastrointestinal abnormalities that could account for the lean phenotype. No histological abnormality was evident throughout the stomach, small intestine (data not shown), and colon (Fig. 4A) of 1-year-old Pla2g10−/− mice, arguing against the idea that the lean phenotype of Pla2g10−/− mice may be attributable to gut inflammation. A recent in situ hybridization study has revealed the distribution of Pla2g10 mRNA in the columnar epithelial cells of mucosal villi in the mouse ileum and colon (33). In good agreement with this, immunohistochemistry of mouse gastrointestinal tissue using an anti-mouse sPLA2-X antibody demonstrated the localization of sPLA2-X protein in gastric and ileac epithelial cells (Fig. 4B). Likewise, glandular epithelial cells in the human intestinal mucosa were positively stained with anti-human sPLA2-X antibody but not with anti-human sPLA2-V antibody used as a control (Fig. 4C). These results imply that sPLA2-X is secreted from the gastrointestinal mucosa into the lumen.

FIGURE 4.

Reduced gastrointestinal phospholipid digestion in Pla2g10−/− mice. A, hematoxylin and eosin staining of the colon of aged (65 weeks old) Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice. B, shown is immunohistochemical localization of sPLA2-X in the stomach and ileum of wild-type mice. Mucosal epithelial cells in the gastric and ileac glands were intensely stained with anti-sPLA2-X, but not control, antibody. C, shown is immunohistochemical localization of sPLA2-X in human colon. Intense staining of sPLA2-X was found in epithelial cells in the mucosal glands adjacent to empty-looking goblet cells, whereas staining of sPLA2-V was scarcely evident. D and E, ESI-MS analysis of PC extracted from stools of 65-week-old Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice is shown. A representative MS spectrum is shown in D, and quantification of the peak of PC (34:2 (16:0–18:2)) (mean ± S.D., n = 3, *, p < 0.05) is shown in E. Values represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 3; *, p < 0.05), with a pool from 3 mice in each measurement.

Deletion of sPLA2-IB (Pla2g1b−/−), a pancreatic sPLA2 that is secreted from pancreatic acinar cells into the duodenum, decreases the digestion of dietary and biliary phospholipids in the intestinal lumen, thereby protecting the animals from high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin intolerance (3, 4). To address the possibility that sPLA2-X in the gut might also participate in this process, i.e. phospholipid digestion, we examined fecal phospholipid contents in 1-year-old Pla2g10−/− mice in comparison with age-matched controls. Interestingly, ESI-MS analysis revealed that the feces of Pla2g10−/− mice contained more PC molecular species, such as PC-34:2 (16:0–18:2, indicating the presence of the two fatty acyl chains 16:0 and 18:2; m/z = 758), PC-34:1 (16:0–18:1; m/z = 760), PC-36:4 (16:0–20:4; m/z = 782), PC-36:3 (18:1–18:2 or 18:0–18:3, m/z = 784), and PC-36:2 (18:0–18:2; m/z = 786) than those of Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 4D). Quantification of the peak for PC-34:2 showed that Pla2g10−/− mice had 5-fold more fecal “undigested” PC output than did Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 4E). Neither LPC-16:0 (m/z = 496) nor −18:0 (m/z = 524) was detected in the stools of either Pla2g10+/+ or Pla2g10−/− mice (data not shown), indicating that LPC, once produced, could be fully absorbed or degraded during passage through the gastrointestinal tract in both genotypes. Collectively, these results suggest that the digestion of phospholipids in the gastrointestinal tract is substantially reduced in Pla2g10−/− mice relative to Pla2g10+/+ mice. This subtle but sustained reduction of gastrointestinal phospholipid digestion during aging may eventually affect the weight gain, adiposity, and muscular insulin sensitivity in aged Pla2g10−/− mice.

Roles of sPLA2-X in Neurons

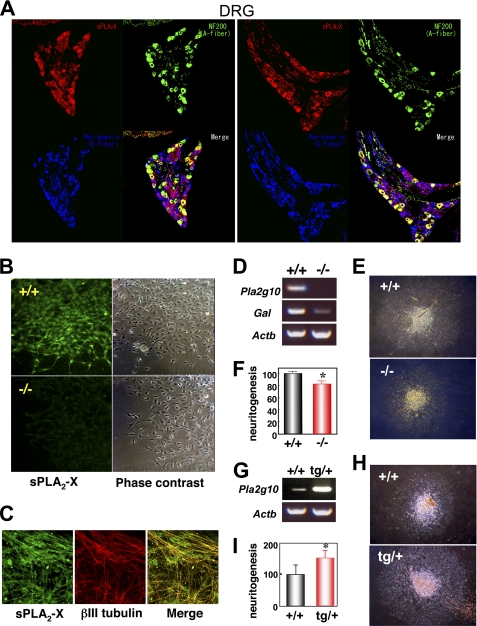

Although the expression of sPLA2-X in many tissues other than the reproductive and gastrointestinal organs is rather low or even below the detection limit (Fig. 1A), previous studies have reported that it is uniquely restricted to neuronal fibers of multiple peripheral tissues and that it has the ability to augment neurite outgrowth of cultured neuronal cells through production of LPC (25, 26, 33). To gain further insights into this issue, we confirmed the localization of sPLA2-X in peripheral neuronal fibers of human tissues by immunohistochemistry. Consistent with a previous report (25), neuronal fibers in various tissues as well as DRG were positively stained with anti-human sPLA2-X antibody but not with anti-human sPLA2-V or control antibody (supplemental Fig. S5). Triple immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of mouse DRG using antibodies against mouse sPLA2-X, NF200 (an A-fiber marker), and peripherin (a C-fiber marker) revealed that sPLA2-X was localized in both NF200-positive A-fibers and peripherin-positive C-fibers, more intense signals being associated with A-fibers (Fig. 5A). We then isolated DRG from mouse fetuses (E12.5) and cultured them with 20 ng/ml NGF for 24 h on laminin-coated plates, a condition under which marked extension of neuronal fibers took place (25). When DRG explants from Pla2g10−/− mice and littermate Pla2g10+/+ mice were immunostained with anti-mouse sPLA2-X antibody, Pla2g10+/+, but not Pla2g10−/−, DRG showed staining signals in the extending neurites (Fig. 5B). In Pla2g10+/+ DRG explants, immunoreactivity for sPLA2-X largely overlapped that of βIII-tubulin, an immature neuronal filament marker (Fig. 5C). Expression of Pla2g10 mRNA in Pla2g10+/+, but not in Pla2g10−/−, DRG was verified by RT-PCR (Fig. 5D). After culture for 48 h in the presence of 20 ng/ml NGF, the extending DRG explants from Pla2g10−/− mice appeared slightly smaller than those from littermate Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 5E). On average, the neurite area of Pla2g10−/−-derived DRG explants was ∼20% smaller than that of Pla2g10+/+-derived ones (Fig. 5F), suggesting that sPLA2-X participates only partly, but significantly, in neuritogenesis of DRG neurons in this ex vivo experimental setting.

FIGURE 5.

sPLA2-X is expressed in mouse DRG neurons and promotes ex vivo neuritogenesis. A, triple confocal laser immunofluorescence staining of mouse DRG with antibodies against sPLA2-X (red), NF200 (green), and peripherin (blue) is shown. Stainings of two representative sections are shown. Merged imaging indicated that sPLA2-X was localized in both A-fibers (yellow) and C-fibers (purple). B, DRG explants from Pla2g10+/+ (upper panels) and Pla2g10−/− (lower panels) fetuses (E 12.5) were cultured for 48 h with 20 ng/ml NGF and immunostained with anti-sPLA2-X antibody (left panels). Phase-contrast images are shown in the right panels. Original magnification, ×200. C, DRG explants from Pla2g10+/+ mice were subjected to double confocal laser immunofluorescence staining with anti-sPLA2-X (green) and anti-βIII-tubulin (red) antibodies and merged (yellow). Original magnification, ×400. D, expression of Pla2g10 (sPLA2-X), Gal (galanin), and Actb (β-actin) mRNAs in DRG neurons freshly isolated from Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− fetuses was assessed by RT-PCR. E, light microscopic images of DRG explants from Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice. Original magnification, ×40. F, evaluation of neurite outgrowth from Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− explants, with areas of Pla2g10+/+ DRG explants regarded as 100% (n = 7, mean ± S.D.; *, p < 0.05). G, expression of Pla2g10 and Actb mRNAs in DRG neurons freshly isolated from Pla2g10tg/+ and Pla2g10+/+ mice was assessed by RT-PCR. H, light microscopic images of DRG explants from Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10tg/+ mice after culture for 48 h with 1 ng/ml NGF. Original magnification, ×40. I, evaluation of neurite outgrowth of Pla2g10tg/+ and Pla2g10+/+ DRG explants, with areas of Pla2g10+/+ DRG explants regarded as 100% (n = 7, mean ± S.D.; *, p < 0.05).

To corroborate these findings further, we next examined the ex vivo neuritogenesis of DRG explants from Pla2g10tg/+ mice in comparison with those from littermate controls. RT-PCR analysis verified that the expression of Pla2g10 mRNA in Pla2g10tg/+ DRG was higher than that of endogenous Pla2g10 mRNA in wild-type DRG (Fig. 5G). When DRG explants from control mice and Pla2g10tg/+ mice were maintained in the presence of a suboptimal concentration (1 ng/ml) of NGF for 2 days, neuritogenesis was more prominent in the DRG from transgenic mice than in those from control mice (Fig. 5H). On average, there was an ∼1.5-fold increase of neurite outgrowth in the DRG from Pla2g10tg/+ mice compared with that in DRG from control mice (Fig. 5I). Thus, as opposed to the reduced DRG neuritogenesis in Pla2g10−/− mice, increased expression of sPLA2-X in Pla2g10tg/+ mice accelerated this event. These results are compatible with previous findings that exogenous addition or overexpression of sPLA2-X in cultured neuronal cells facilitates neuritogenesis (25, 26).

To obtain additional evidence for the neuritogenic role of sPLA2-X in vivo, DRG neurons freshly isolated from E12.5 fetuses of Pla2g10−/− mice and their littermate controls were subjected to microarray gene profiling. We found that, among >30,000 genes, the expression levels of several neuron-associated genes that have been implicated in neurite growth, neuronal transmission, synaptic plasticity, and nociception were reproducibly lower in the null mice than in wild-type mice. These genes included homeobox B8 (Hoxb8), C-terminal kinesin superfamily motor (Kifc1), galanin (Gal), Ca2+-transporting plasma membrane ATPase 2 (Atp2b2), neurotropic tyrosine kinase receptor type 2 (Ntrk2 or TrkB), casein kinase 1ϵ (Csnk1e), ankyrin 2 (Ank2), and N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein (Nsf) (the Pla2g10−/− versus Pla2g10+/+ values being 0.43 ± 0.11, 0.53 ± 0.17, 0.59 ± 0.04, 0.63 ± 0.38, 0.68 ± 0.08, 0.68 ± 0,14, 0.70 ± 0.16, and 0.72 ± 0.15, respectively, for two evaluations). Consistent with this gene profiling, the expression of Gal mRNA, as assessed by RT-PCR, was substantially reduced in DRG neurons of Pla2g10−/− mice relative to those of Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 5D).

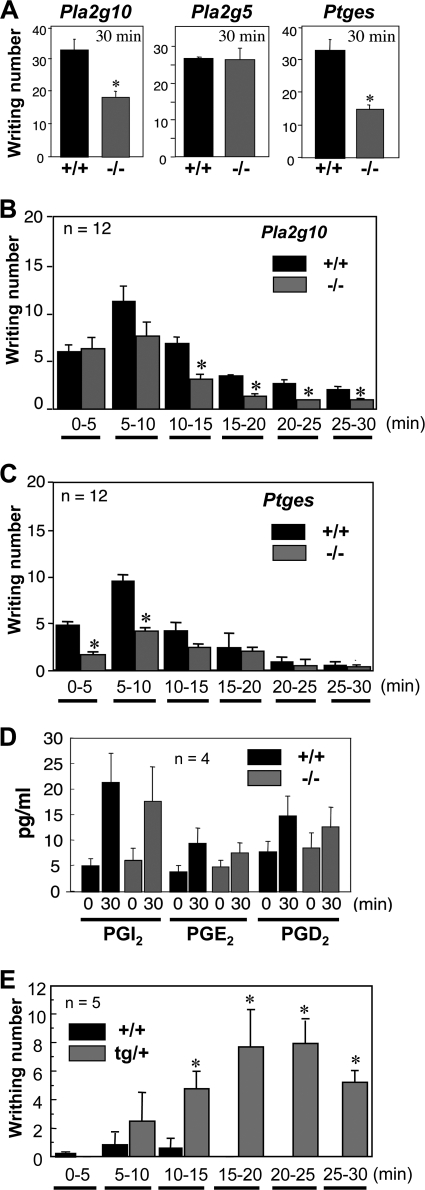

It has been reported that mice lacking galanin or its receptor show attenuation of the late phase of pain after a chemical stimulus (34–39). We, therefore, sought to clarify whether sPLA2-X would participate in pain sensation in vivo. To address this issue, we performed the acetic acid writhing test, a commonly used model for the evaluation of peripheral noxious pain (28). For this test, 0.9% acetic acid solution in saline was injected intraperitoneally into Pla2g10−/− and Pla2g10+/+ mice, and the number of episodes of stretching behavior over 30 min was counted. Interestingly, the writhing response of Pla2g10−/− mice was reduced by half in comparison with replicate Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 6A, left). However, when the same experiment was carried out using Pla2g5−/− mice and their littermate controls, their pain responses were comparable (Fig. 6A, middle), suggesting that sPLA2-V does not contribute to pain sensation in this model. Because prostanoids such as PGE2 can stimulate pain sensation (40–45), we also examined the pain response of mice deficient in mPGES-1 (Ptges−/−), an enzyme crucial for PGE2 synthesis downstream of PLA2, in the same model. As expected (28), the writhing response of Ptges−/− mice was reduced by nearly half compared with replicate Ptges+/+ mice (Fig. 6A, right).

FIGURE 6.

sPLA2-X is involved in pain perception. A, Pla2g10-, Pla2g5-, and Ptges-deficient mice and their littermate wild-type mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.9% (v/v) acetic acid, and their episodes of stretching behavior over 30 min were counted (n = 12, mean ± S.D.; *, p < 0.01 versus wild type (+/+)). B and C, the writhing responses of Pla2g10−/− (B) and Ptges−/− (C) mice in comparison with those of their littermate wild-type mice were counted every 5 min (n = 12, mean ± S.D.; *, p < 0.05 versus wild-type for each time interval). D, spinal eicosanoid levels with or without intraperitoneal administration of acetic acid in Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice are shown. The pain-nociceptive eicosanoid levels were determined by column-switching reverse-phase LC-MS/MS (n = 4, mean ± S.D.). E, Pla2g10tg/+ and control Pla2g10+/+ mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.4% (v/v) acetic acid, and their episodes of stretching behavior were counted every 5 min (n = 5, mean ± S.D.; *, p < 0.01 versus wild-type for each time interval).

On the basis of these results, one could argue that sPLA2-X might be placed upstream of mPGES-1 in the PGE2 biosynthetic pathway (i.e. sPLA2-X supplies AA for PGE2 synthesis), thereby participating in pain nociception. However, this possibility was shown to be unlikely, as we found a notable kinetic difference in the pain sensation between Pla2g10−/− mice and Ptges−/− mice; when the writhing response was monitored every 5 min in control mice, it peaked 5–10 min after acetic acid injection and then declined gradually up to 30 min (Fig. 6, B and C). Although the pain responses in Pla2g10−/− mice and Pla2g10+/+ mice were similar during the initial 5 min, thereafter Pla2g10−/− mice showed fewer responses in each time interval, thereby displaying earlier recovery than did Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 6B). In contrast, pain reduction in Ptges−/− mice, in comparison with Ptges+/+ mice, was evident only during the initial 10 min, whereas during the later phase (10–30 min) there was no significant difference in the writhing reaction between the genotypes (Fig. 6C). Thus, the apparent phase separation of the altered pain responses in Pla2g10−/− mice versus Ptges−/− mice argues against the idea that sPLA2-X and mPGES-1 lie in the same PGE2 biosynthetic pathway. Because the late phase of pain behavior induced by chemical stimuli is thought to involve central mechanisms within the spinal cord (46), we determined the spinal eicosanoid levels in Pla2g10+/+ and Pla2g10−/− mice using LC-MS/MS analysis. In wild-type mice, the levels of pain-nociceptive prostanoids, such as PGI2 (6-keto-PGF1α as a stable end product), PGE2, and PGD2 (40–45), were increased ∼4-, 2-, and 1.5-fold, respectively, after 30 min of acetic acid challenge relative to their basal levels (Fig. 6D). The levels of these prostanoids in acetic acid-treated Pla2g10−/− mice did not differ significantly from those in replicate wild-type mice. Thus, pain modulation by sPLA2-X may occur independently of prostanoid synthesis.

In light of these findings in Pla2g10−/− mice, we next tested whether the pain response would be conversely enhanced in Pla2g10tg/+ mice. After intraperitoneal injection of a lower concentration (0.4%) of acetic acid, which produced only a modest pain response in wild-type mice, Pla2g10tg/+ mice exhibited a striking increase in the pain response over 30 min (Fig. 6E). Monitoring of the writhing response every 5 min showed that, although the response was minimal during the initial 5 min in both Pla2g10tg/+ and Pla2g10+/+ mice, thereafter the transgenic, but not control, mice exhibited a markedly augmented writhing reaction during each time interval (Fig. 6E), revealing increased and sustained pain through overexpression of sPLA2-X.

We also examined whether disruption of the Pla2g10 gene would influence thermal algesia. In this test, Pla2g10−/− mice and Pla2g10+/+ mice were kept on a hot plate at 52.5 °C, and their escape behavior, including licking, standing, and jumping, was monitored as a function of retention time. However, there were no differences in this behavior between the genotypes (supplemental Fig. S6). Thus, unlike chemical-induced pain (see above), sPLA2-X plays no role in the acute pain response elicited by exposure to noxious heat.

DISCUSSION

Because the ability of sPLA2-X to act on PC, a major phospholipid in cellular membranes or lipoprotein particles, is far more potent than that of other mammalian sPLA2s (1, 2), it has been postulated that this particular sPLA2 isoform may play roles in the hydrolysis of cellular membrane phospholipids, leading to production of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators (17, 18) and in the hydrolysis of lipoproteins leading to atherosclerosis (19, 20). This idea has been supported by recent studies demonstrating that Pla2g10−/− mice were refractory to Th2-dependent asthma (21) and ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial injury (22), in which reductions of eicosanoids in the null mice were evident. However, the fact that sPLA2-X is constitutively expressed at high levels in genital and gastrointestinal organs (Fig. 1A) (23, 24, 33, 27) has raised a question as to the physiological roles of this enzyme in these locations. In the present study, we have highlighted the inflammation-unrelated roles of this particular sPLA2 in homeostasis of these organs.

Reproduction

By analyzing the fertility of Pla2g10−/− mice, we have recently shown that sPLA2-X is a bona fide sperm acrosomal sPLA2 that regulates fertility (27). Thus, sPLA2-X is released from sperm acrosomes and boosts the acrosome reaction, a prerequisite step for successful fertilization. LPC, a PLA2 reaction product that has been postulated to be required for proper acrosome function or sperm-egg fusion (47, 48), is capable of restoring the reduced fertility of Pla2g10−/− spermatozoa (27). However, several points have yet to be resolved. First, it is still unknown whether Pla2g10−/− spermatozoa have some additional abnormalities in a step before acrosome reaction. In this study, we have obtained evidence that the abnormality in Pla2g10−/− spermatozoa does not occur before the acrosome reaction step, as the null sperm cells displayed normal capacitive motility (Fig. 1B and supplemental Table S1). Second, our previous observation that a reduction of litter size was evident only when Pla2g10−/− males were crossed with Pla2g10−/−, but not with wild-type, females (27) suggests that sPLA2-X in both genders may contribute to fertility; however, the expression and function of sPLA2-X in female genital organs have not yet been addressed. Here, we found that sPLA2-X is expressed in luminal epithelial cells in the uterus as well as in oocytes in the ovary of female mice (Fig. 1C). The luminal endometrial localization of sPLA2-X suggests its paracrine action from the epithelium onto spermatozoa ejaculated into the uterine duct, where the enzyme may play a supporting role in sperm sorting by boosting a premature acrosome reaction (27). The localization of sPLA2-X in oocytes led us to speculate that sPLA2-X from both spermatozoa and oocytes may be required for fully successful fertilization. Indeed, polyunsaturated fatty acids can function in oocytes as precursors of signals that control sperm recruitment in Caenorhabditis elegans (49), and oocytes release vesicles (a potential sPLA2 target) into the perivitelline space that confer sperm-fusion ability (50). Contrary to this expectation, however, Pla2g10−/− oocytes showed the same fertilizing capacity as wild-type oocytes (Fig. 1D), indicating that the deficiency of sPLA2-X in oocytes does not have a profound impact on fertility, at least under the IVF conditions we employed.

Beyond the sperm-egg interaction, it is possible that sPLA2-X may also participate in other regulatory steps of female reproduction, such as ovulation, implantation, decidualization, and parturition, in which lipid mediators such as PGE2 and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) play crucial roles (51–55). Although deficiency of group IVA cytosolic PLA2α (cPLA2α) impairs implantation and parturition, the presence of residual prostanoids at the time of implantation in the Pla2g4a−/− uterus implies the contribution of additional PLA2(s) to this process (55). Interestingly, sPLA2-X co-localizes with cPLA2α and cyclooxygenase in the uterine epithelium during the course of implantation (55). Likewise, although a lack of cyclooxygenase-2 or the PGE2 receptor EP2 impairs ovulation (51, 54), no abnormality in the ovulation has been reported for mice deficient in cPLA2α, suggesting the involvement of other PLA2(s) in this step. Whether sPLA2-X could serve as an alternative source of arachidonic acid in ovulation, implantation, or other female reproductive processes requires further elucidation.

Phospholipid Digestion in the Gut

Phospholipids entering the digestive tract from the diet and bile comprise the second most abundant lipid class found in the intestinal lumen (56). It has been suggested that PLA2 functions in hydrolyzing these phospholipids into lysophospholipids, most of which can be absorbed by enterocytes and transported to the liver via the portal circulation (57). Hydrolysis of phospholipids by PLA2 on the surface of lipid emulsion is required before digestion of triglycerides, a major lipid nutrient (58). Pancreatic lipase and carboxyl ester lipase work together to mediate the hydrolysis and subsequent absorption of a large portion of dietary triglycerides, and reduced lipid absorption efficiency due to inactivation of these lipase genes results in protection against diet-induced obesity (59). For a long time, sPLA2-IB, a pancreatic sPLA2, has been believed to be the sole sPLA2 isoform that works in the digestion of dietary phospholipids in the gastrointestinal tract. Indeed, gene targeting of Pla2g1b, which encodes sPLA2-IB, leads to a marked reduction in the production and absorption of LPC in the gastrointestinal tract under a high-fat/carbohydrate diet (3). Increased intestinal absorption of LPC promotes postprandial hyperglycemia by inhibiting glucose uptake by the liver and muscle, and accordingly, Pla2g1b−/− mice are protected from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance (4). Under basal dietary conditions, however, intestinal phospholipid digestion in Pla2g1b−/− mice appears normal, leading to the suggestion that an additional enzyme(s) in the gastrointestinal tract could compensate for the lack of sPLA2-IB (60).

In the present study, we found that Pla2g10−/− mice displayed a lean phenotype as they aged (Fig. 2). It appears that this phenotype of Pla2g10−/− mice is, from several standpoints, similar to that of Pla2g1b−/− mice (3), even though each of these studies was performed under distinctly different dietary conditions (i.e. chow and high-fat/carbohydrate diets) and time scales (over 1 year and 14∼15 weeks) in different facilities. Thus, under a chow diet, Pla2g10−/− mice showed lower adiposity and higher muscle insulin sensitivity than did wild-type mice (Figs. 2 and 3). Because serum levels of lipoproteins, insulin, and other biomedical and hormonal markers as well as food intake and energy expenditure were unaffected in Pla2g10−/− mice and because no or only low expression of sPLA2-X was found in the blood, liver, muscle, and adipose tissue, it is unlikely that sPLA2-X has a great impact on lipoprotein hydrolysis, hormonal secretion, lipolysis, and fat oxidation in these locations. Although body weight loss and increased insulin sensitivity are reminiscent of the key clinical features of hypocortisolism (61), the serum corticosterone levels did not differ significantly between Pla2g10−/− and Pla2g10+/+ mice even though the former tended to show a higher level. In this regard, a recent study has shown that serum corticosterone levels are significantly higher in another line of Pla2g10−/− mice relative to control mice and that sPLA2-X has the ability to suppress liver X receptor-mediated activation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, which is a master regulator of steroid synthesis, in adrenal cells (62). Nevertheless, we found no evidence that Pla2g10−/− mice had altered food intake and energy expenditure, as would be expected if altered corticosterone levels were having a central effect on adiposity.

The fact that sPLA2-X is abundantly expressed in the gut (Fig. 1A), where its mRNA (33) and protein (Fig. 4B and C) are enriched in the mucosal epithelium in both mice and humans, suggests that it is secreted into the gastroenteric lumen to encounter its target substrates. Notably, we found that 5-fold more undigested PC remained in the fecal content of Pla2g10−/− mice in comparison with Pla2g10+/+ mice (Fig. 4, D and E), suggesting that phospholipid digestion in the gastrointestinal lumen is reduced in the absence of sPLA2-X. Considering that the main phospholipid in the gastrointestinal lumen is PC from dietary and biliary origins, the high binding capacity of sPLA2-X (relative to other sPLA2s) toward PC appears in accord with the digestive role of this enzyme. As such, subtle but continuous reduction in PC digestion (and thereby perturbation of LPC production and absorption) over a long period in the gastrointestinal lumen may culminate in reduced adiposity and increased muscle insulin sensitivity in aged Pla2g10−/− mice (Figs. 2 and 3). The significantly reduced body length of aged Pla2g10−/− mice compared with that of Pla2g10+/+ mice also supports this idea (Fig. 2B). This speculation is in line with the view that, even if dietary fat digestion and absorption are completed, their delay leads to changes in the spatiotemporal distribution of fat absorption in the gastrointestinal tract that can be linked to decreased adipose fat storage and altered metabolic efficiency, as evidenced by ablation of pancreatic and carboxyl ester lipases (59) or monoacylglycerol acyltransferase (MGAT2), a major fat re-esterification enzyme in the proximal intestine that is coupled with transport of lipids to chylomicron for distribution to peripheral tissues (63).

Taken together with previous data, the present study has provided new insight into the physiological function of sPLA2-X as a component of phospholipid digestion in the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, sPLA2-IB and sPLA2-X, the two particular sPLA2s that can be activated through proteolytic removal of the N-terminal propeptide, may play a compensatory role in phospholipid digestion in the gastroenteric lumen. Because sPLA2-IB is abundantly secreted into the duodenum from the pancreatic gland (3), whereas sPLA2-X is constitutively expressed throughout the gastrointestinal mucosa (Fig. 1A) (23, 24, 33), these two “digestive” sPLA2s may spatiotemporally control the hydrolysis of dietary and biliary phospholipids and thereby absorption of their hydrolytic products, depending on the quantity and quality of dietary and biliary fat input.

In Pla2g1b−/− mice under a hypercaloric diet, the absence of the elevation of postprandial LPC increases fatty acid uptake and utilization in the liver, and this eventually results in less fatty acid availability to extrahepatic tissues such as adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, thereby contributing to the reduced adiposity and increased insulin sensitivity (4, 64). It is likely that the improved insulin sensitivity in the skeletal muscle of Pla2g10−/− mice is caused by a similar mechanism, given the common (even if not entirely identical) role of sPLA2-IB and sPLA2-X in gastrointestinal lipid digestion. As such, age-associated accumulation of lipids may inhibit muscle insulin signaling and further promote age-associated insulin resistance (known as the process of lipotoxicity (65)) in wild-type mice, whereas altered fat partitioning due to the absence of sPLA2-X may contribute to improved insulin tolerance in the skeletal muscle. Indeed, as obesity develops in humans, high serum levels of LPC correlates positively with early-stage obesity (66), and elevated LPC levels precede the lipotoxic phenomena hallmarked by the overflow of fatty acids and dysregulation of the lipid sensor PPAR signaling (67).

Several questions remain to be answered, however. First, how does gastrointestinal sPLA2-X influence obesity and associated metabolic disorders when dietary fat is abundant, a situation that seems to be more relevant to modern life in developed countries? As sPLA2 activity could be dramatically affected by the abundance of neutral lipids and detergent-like components (e.g. bile acid), the relative contributions of sPLA2-IB, sPLA2-X, and possibly another gastroenteric phospholipase(s) to phospholipid digestion may vary according to meal content under certain animal housing conditions. In this context the outcome of lipid digestion and, thereby, adiposity, might be affected differently by several variables that are unique to each research institution, including the gastrointestinal microflora and drinking water, and this might explain why deletion of Pla2g10 has been reported to have positive (32), negative (this study), or no (22) impact on adiposity in different studies. This idea also fits with a recent view that sPLA2-X modulates the signaling of liver X receptor, a lipid-sensing nuclear receptor whose activation can be influenced by dietary lipid content and composition (32, 62). Second, considering that digestion and absorption of lipids occur mostly in the small intestine, what is the role of sPLA2-X in the distal colon, where the enzyme is expressed at a much higher level? Third, does sPLA2-X take part in some forms of gastrointestinal pathology such as colitis and cancer, which are affected by several extrinsic and intrinsic factors including ingested food, the enterobacterial flora, and defensive or offensive lipid mediators? In this context, the proposed anti-bacterial and PGE2-producting capacities of sPLA2-X in vitro (17, 18, 33, 68) suggest that the enzyme may have additional functions in the gastrointestinal tract. Indeed, recent evidence has revealed that the enterobacterial flora may be linked with metabolic syndrome and immunity (69, 70). From this viewpoint, modification of the gastroenteric microbiota by sPLA2-X through its bactericidal activity (68) might have variable influences on the incidence, onset, and severity of obesity, inflammation, and cancer.

Neuronal Function

Although the expression levels of sPLA2-X in tissues other than reproductive and digestive organs are low, its immunoreactivity is associated with neuronal fibers in multiple peripheral tissues (supplemental Fig. S5). In vitro, sPLA2-X is capable of promoting neurite outgrowth through the production of LPC, a neuritogenic lysophospholipid, in cultured neuronal cells, in which the enzyme is preferentially localized at the leading edges of growth cones or bulges, where secretory vesicles are abundant (25, 26). In an effort to explore the physiological relevance of this in vitro observation, we found that Pla2g10 gene-manipulated mice displayed notable neuronal phenotypes, namely alterations in neuritogenesis of DRG explants ex vivo and pain nociception in vivo. The fact that gene disruption and transgenic overexpression resulted in opposite phenotypes implies that our present findings reflect the true functional aspects of sPLA2-X, which is intrinsically localized in peripheral neurons (25).

The DRG represents an assembly of primary afferent nerve fibers that transmit the impulses of peripheral nociceptive signals. We found that ex vivo neuronal outgrowth of DRG explants from Pla2g10−/− mice was reduced modestly but significantly, whereas that from Pla2g10tg/+ mice was enhanced relative to that from control mice (Fig. 5). These results are in good agreement with previous observations that overexpression and knockdown of sPLA2-X had augmentative and suppressive effects, respectively, on neurite extension by affecting LPC production in cultured PC12 cells (25, 26). LPC, a primary PLA2 reaction product, can modulate neuronal outgrowth through multiple mechanisms (26). LPC in combination with fatty acids induces enlargement of nerve terminals, closely mimicking the changes observed in sPLA2-treated neurons (71). In this way LPC remains confined mainly to the external leaflet of the presynaptic membrane, whereas fatty acids have a high rate of transbilayer movement and will partition between the two membrane leaflets. In view of the fact that cell membrane expansion is achieved through fusion of transport organelles with the plasma membrane, such a configuration, with the inverted cone-shaped LPC in trans and the cone-shaped fatty acid in cis with respect to the membrane fusion site, may allow axonal membrane expansion. Moreover, ω-3 and ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids stimulate neuronal cell membrane expansion by acting on syntaxin 3, a SNARE protein that is essential for axonal growth (72). Thus, LPC and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which can be produced simultaneously by sPLA2-X (or possibly other neuronal PLA2(s)), may act in synergy to facilitate the addition of transport vesicle material to the plasma membrane.

Microarray gene profiling of DRG freshly isolated from E12.5 Pla2g10−/− and Pla2g10+/+ fetuses revealed that the expression of several genes that have been implicated in neuronal outgrowth and function was reduced in the null mice. For instance, gene manipulation of Hoxb8, a homeobox-containing transcription factor, resulted in abnormalities in the obsessive-compulsive disorder circuit in the central nervous system, ontogenesis, and development of the upper cervical DRG and the nociceptive response (73–75). Kifc2 is a neuron-specific C-terminal kinesin superfamily motor for the transport of multivesicular body-like organelles in dendrites (76). Ntrk2/TrkB, a receptor for brain-derived neurotrophic factor, plays a role in neuronal survival and pain transmission (77). Galanin is a neuropeptide that facilitates the developmental survival and neuritogenesis of a subset of DRG and regenerating sensory neurons (34, 35). Mice deficient in galanin receptor 2 (Galr2) show decreased neurite outgrowth from adult sensory neurons and an impaired pain response (36, 37). Intriguingly, the second phase of irritant-induced pain via the transient receptor potential channels TRPA1 and TRPV1 is attenuated in Gal- or Galr2-knock-out mice (38), and TRPV1 and galanin receptor 2 are co-localized in some populations of primary afferent DRG neurons (39). Thus, the reduced expression of these genes in Pla2g10−/− mice lends support to the idea that sPLA2-X may play a role in DRG neuritogenesis and pain transmission in vivo.

Indeed, we found that peripheral pain nociception was markedly altered in Pla2g10-deficient and -overexpressing mice. The acid-induced writhing response, a model of the noxious pain mediated by TRPV1 (78, 79), was ameliorated in Pla2g10−/− mice but conversely increased in Pla2g10tg/+ mice, as compared with replicate control mice (Fig. 6). It is noteworthy that, as has been reported for Gal- or Galr2-null mice (38), the pain modulations observed in Pla2g10-deficient and -transgenic mice were obvious in the late, rather than initial, phase of the pain response. This was in marked contrast to Ptges−/− mice, in which the pain reduction was limited to the initial few minutes and was not evident in the later period, thus arguing against the contribution of sPLA2-X to the mPGES-1/PGE2-dependent pain response in this setting. The fact that neither the spinal (Fig. 6D) nor peripheral (data not shown) level of prostanoids was significantly altered in Pla2g10−/− mice relative to controls supports this speculation. A likely explanation for these results is that some sPLA2-X-dependent developmental changes in the neuronal micro-network, which are supported by ex vivo DRG neuritogenesis and by gene profiling, may eventually influence the pain-sensory response of adult animals. Unfortunately, our efforts to evaluate the differences in bulk levels of LPC, a potential neuritogenic product of sPLA2-X (25, 26), in neuronal samples from Pla2g10−/− and Pla2g10+/+ mice were unsuccessful because of very high background levels of LPC in biological fluids. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that subtle and spatiotemporal alterations of neuronal micro-networks by sPLA2-X might occur within neuronal microenvironments. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that the absence of sPLA2-X dramatically alters the number or type of pain fibers in vivo, as the pain response to noxious heat was unchanged (supplemental Fig. S6) and as expression of only a subset of genes was decreased in Pla2g10-null DRG.

However, we do not fully rule out the possibility that sPLA2-X may affect the “local” production of some lipid mediators linked to pain sensation. It is known that PGE2 and PGI2 are critically involved in pain transmission (40–43) and that PGD2 modulates PGE2-evoked allodynia (44, 45). These prostanoids stimulate a population of TRPV1-positive, C-fiber DRG neurons to release peptide neurotransmitters (80). Observations that the late, prostanoid-dependent phase of chemical-induced pain is suppressed by a pan-sPLA2 inhibitor (81) and that the noxious heat-evoked, TRPV1-dependent response does not depend on prostanoids (80) appear to be compatible with our present findings. LPA, which is produced from LPC by autotaxin, plays a role in neuropathic pain via its receptor LPA1 by promoting demyelination of A-fibers and subsequent direct contact between A- and C-fibers (82, 83). Arachidonic acid itself can enhance the current of acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3), another class of pain sensor expressed in DRG neurons (84). Overall, even though the majority of these neuronal pain-sensing lipid mediators may be produced through the pathways dependent upon other phospholipases (83, 85), it is still possible that the coordinated action of the lipid products produced by sPLA2-X at certain neuronal microdomains may have a spatiotemporal effect on neuronal transmission leading to persistent pain nociception.

Although our present study has highlighted the neuritogenic and nociceptive roles of sPLA2-X, the neuronal location of sPLA2-X in several peripheral tissues (supplemental Fig. S5) may underlie an alternative mechanism for the regulation of tissue-specific homeostasis by this enzyme. For instance, localization of sPLA2-X in neuronal fibers in male genital organs suggests that the enzyme might be involved in the autonomic nervous response for ejaculation. The expression of sPLA2-X in ganglion cells of the myenteric plexus between smooth muscle cell fibers in the gastrointestinal tract (25, 33) might be a reflection of its potential role in the peristaltic reflex controlled by the enteric nervous system, which could exert further influence on gastrointestinal lipid digestion and absorption. Finally, besides the reported negative regulatory role of sPLA2-X in liver X receptor-dependent metabolic processes in the adrenal glands and adipose tissues (32, 62), the neuronal location of sPLA2-X in adipose tissue might be related to the neuroendocrine regulation of adiposity.

Conclusion

Studies by several groups in the past few years have revealed diverse functional aspects of sPLA2-X in pathology and physiology. Findings that Pla2g10−/− mice were protected from disease models of asthma, ischemic myocardial injury, and aneurysm (20–22) beyond moderate defects in fertility (27) and hair growth (86) point to this enzyme as a potential drug target. On the basis of our present findings, such a sPLA2-X-inhibitory agent may also be applicable as a novel analgesic drug. Likewise, considering that oral administration of a pan-sPLA2 inhibitor prevents diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance (87), inhibition of gastrointestinal sPLA2s (IB and X) may be useful for treatment of patients with diet-induced metabolic syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. J. P. Arm (Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Cambridge, MA) and S. Akira (Osaka University, Suita, Tokyo) for providing Pla2g5- and Ptges-deficient mice, respectively, and Drs. T. Shimizu and Y. Kita (University of Tokyo) for ESI-MS/MS analysis of eicosanoids.

This work was supported by grants-in aid for Scientific Research and for Young Scientists from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, PRESTO and CREST from the Japan Science and Technology Agency, Mitsubishi Science Foundation, the Uehara Science Foundation, and the Toray Science Foundation.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S6.

- PLA2

- phospholipase A2

- sPLA2

- secreted PLA2

- sPLA2-X

- group X sPLA2

- cPLA2α

- cytosolic PLA2α

- CT

- computed tomographic

- DRG

- dorsal root ganglion

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- IGF-1

- insulin-like growth factor 1

- IVF

- in vitro fertilization

- LPC

- lysophosphatidylcholine

- MEF

- mouse embeyonic fibroblast