Abstract

Myocardial ischemia is transmurally heterogeneous where the subendocardium is at higher risk. Stenosis induces reduced perfusion pressure, blood flow redistribution away from the subendocardium, and consequent subendocardial vulnerability. We propose that the flow redistribution stems from the higher compliance of the subendocardial vasculature. This new paradigm was tested using network flow simulation based on measured coronary anatomy, vessel flow and mechanics, and myocardium-vessel interactions. Flow redistribution was quantified by the relative change in the subendocardial-to-subepicardial perfusion ratio under a 60-mmHg perfusion pressure reduction. Myocardial contraction was found to induce the following: 1) more compressive loading and subsequent lower transvascular pressure in deeper vessels, 2) consequent higher compliance of the subendocardial vasculature, and 3) substantial flow redistribution, i.e., a 20% drop in the subendocardial-to-subepicardial flow ratio under the prescribed reduction in perfusion pressure. This flow redistribution was found to occur primarily because the vessel compliance is nonlinear (pressure dependent). The observed thinner subendocardial vessel walls were predicted to induce a higher compliance of the subendocardial vasculature and greater flow redistribution. Subendocardial perfusion was predicted to improve with a reduction of either heart rate or left ventricular pressure under low perfusion pressure. In conclusion, subendocardial vulnerability to a acute reduction in perfusion pressure stems primarily from differences in vascular compliance induced by transmural differences in both extravascular loading and vessel wall thickness. Subendocardial ischemia can be improved by a reduction of heart rate and left ventricular pressure.

Keywords: coronary flow, stress and flow analysis, coronary network anatomy, myocardial contraction effects, myocardial ischemia

myocardial ischemia, a major cause of morbidity and mortality, is transmurally heterogeneous where the subendocardium is at higher risk than the midwall or epicardium (22). Despite the significant clinical relevance, the physical determinants of subendocardial vulnerability remain controversial. Although subendocardial metabolic demands are somewhat higher than subepicardial ones (22), data have suggested that it is the lower blood supply to the subendocardium, rather than the higher demand, that induces subendocardial vulnerability (23). For example, under partial occlusions (2) or otherwise decreased (9) perfusion pressure in the nonautoregulated coronary circulation, subendocardial blood supply has been observed to be compromised to a higher extent than subepicardial flow, whereas increased perfusion pressure was found to improve primarily the subendocardial supply (3). Hence, changes in perfusion pressure induce transmural flow redistribution, i.e., changes in the subendocardial-to-subepicardial perfusion ratio (Endo/Epi).

Subendocardial vulnerability to ischemia has been previously attributed to several mechanisms, namely, the greater subendocardial systolic compression was proposed to induce one or more of the following: 1) increased subendocardial vessel resistance (5, 36), 2) systolic backflow from endocardial to epicardial vessels (14) induced by systolic-diastolic interactions (23, 39), or 3) transient vessel collapse (12), which would result in effectively higher subendocardial backpressures (2). The first two mechanisms account for a preferentially epicardial blood flow (i.e., Endo/Epi decrease) under increased systolic compression. The predicted effect on flow was not shown to increase, however, under reduced perfusion pressure. It is thus unclear whether these mechanisms alone can account for the measured Endo/Epi decrease under such conditions (2). The proposed transmural differences in backpressures (2), on the other hand, may account for the measured change in Endo/Epi under reduced perfusion pressure. However, vessel collapse has not been demonstrated in the coronary vessels (19, 21, 24), and whether backpressure differences exist or are large enough to account for substantial Endo/Epi changes is still unknown (22, 23). Another proposed mechanism relates to anatomically induced higher resistance of subendocardial conduit vessels or lower resistance of subendocardial microcirculation, which has been suggested (8) to reduce the driving pressure of the subendocardial microcirculation. This mechanism cannot account for flow redistribution under reduced perfusion pressure, as discussed below. Moreover, the pressure drop over conduit vessels has been shown (35) to be small in magnitude.

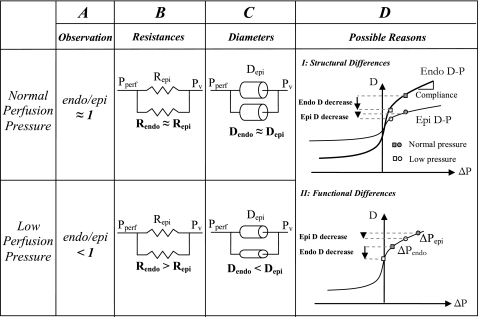

Here, we propose that the measured flow redistribution, and the consequent subendocardial vulnerability under reduced perfusion pressure, results from a higher compliance of the subendocardial vasculature compared with the respective subepicardial vasculature. This hypothesis is based on the premise that since both subendocardial and subepicardial flows are driven by the same pressure source, a difference in transmural flow distribution (Fig. 1A) may only stem from a difference in the respective vascular resistances (Fig. 1B). Flow resistance depends on vascular diameters (Fig. 1C), and diameters depend on the pressure through vascular compliance. Hence, only a higher compliance of the subendocardial vasculature (Fig. 1D) can induce a greater increase in resistance to flow there compared with the subepicardium.

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of subendocardial vulnerability to ischemia. A: the observation that reduced perfusion pressure (Pperf) decreases the subendocardial-to-subepicardial perfusion ratio (Endo/Epi). B: simplified representation of the epicardial and endocardial coronary network. Under normal Pperf, the transmural distribution of flow is approximately homogeneous, implying that subepicardial and subendocardial time-averaged resistances (Repi and Rendo, respectively) are approximately equal. The observed reduction in Endo/Epi must stem from a higher subendocardial resistance than the respective subepicardial resistance under reduced Pperf. Capacitors (representing vascular capacitance) are not considered as, according to circuit theory, they do not affect the time-averaged flow conditions. Pv, vascular pressure. C: physical interpretation of the resistance differences in B. Since vascular resistance highly depends on its diameter, a higher subendocardial resistance under reduced Pperf implies smaller diameters there. Dendo, endocardial diameter; Depi, epicardial diameter. D: possible reasons for smaller subendocardial diameters under low Pperf. I: anatomic differences induce differences between the vessel diameter-pressure (D-P) relations in the subendocardium (Endo) versus the subepicardium (Epi), which result in higher subendocardial compliance (i.e., D-P slope). Hence, under similar transvascular pressures (ΔP), reductions (from shaded to open symbols) will induce a higher diameter decrease in subendocardial vessels (circles) than in subepicardial vessels (rectangles). II: functional differences. Differences between subendocardial and subepicardial time-averaged transvascular pressures ( ), when combined with vascular nonlinear D-P, result in higher subendocardial compliance and a consequent larger diameter reduction in subendocardial vessels, as long as the pressures are within the concave (high) range of the D-P curve.

), when combined with vascular nonlinear D-P, result in higher subendocardial compliance and a consequent larger diameter reduction in subendocardial vessels, as long as the pressures are within the concave (high) range of the D-P curve.

Specifically, we hypothesized that 1) the extravascular loading exerted by the contracting myocardium on its vessels induces lower transvascular pressures (ΔP) in the deep myocardial layers; 2) this effect, when combined with vessel pressure-dependent compliance, induces a higher compliance of the subendocardial vasculature and consequent flow redistribution away from the subendocardium under reduced perfusion pressure; and 3) the thinner subendocardial vascular walls (10) have greater compliance, which further enhances flow redistribution.

Experimental validation of these hypotheses must overcome several difficulties. First, in vivo measurements of coronary flow conditions are generally difficult to perform and are restricted largely to the epicardial layers. Second, coronary vessels are uniquely loaded by both intravascular and extravascular (“intramyocardial”) pressures (PIV and PEV, respectively), with the latter stemming from myocardial contraction. The physical origins of this loading have been the subject of long-standing debate (43) and have only recently been clarified (1). Finally, the coronary vessels are tethered to their adjacent myocytes, so that the commonly measured (11) compliance of isolated vessels is substantially higher (19) than the true, in situ compliance. Moreover, in situ vascular compliance cannot be deduced from in vivo (21, 40) or in situ (16) diameter measurements unless ΔP is simultaneously measured. To address these difficulties, the hypotheses were tested using a biophysical flow analysis, which has been previously validated using a broad range of experimental data, including the dynamic patterns of pressures, flow, and diameters and their transmural and longitudinal distributions (1).

METHODS

The dynamic, transmural flow analysis scheme (Fig. 2) has been previously described in detail (1) and is presented in the Supplement Material.1 The goals of our previous study (1) were to investigate the nature of local contraction-induced extravascular loading, based on detailed network flow analysis. Since ischemia occurs over time scales that are longer than a single beat, the mean beat-to-beat flow conditions are emphasized here rather than systolic/diastolic flow fluctuations. A brief outline of the scheme developed in Ref. 1 is presented here, followed by modifications introduced in the present study aimed to address the present hypotheses. The platform integrates the network reconstructed (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Material, Supplement I) morphometry (29–31), the flow model in each single vessel (Fig. 2B; Supplement II), and a micromechanical vessel-in-myocardium submodel (Fig. 2C; Supplement III). The latter incorporates vessel and myocardium mechanical properties and the effect of myocyte systolic shortening and thickening. Finally, the platform integrates the mechanism of interaction between the contracting myocardium and the coronary blood flow, which was found to be consistent with a large body of coronary physiological data (1). This mechanism consists of the combined effect of left ventricular cavity pressure (LVP) and of myocyte shortening-induced intracellular pressure (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Scheme of the simulation platform. A: network anatomy was reconstructed from statistical morphometric data of porcine coronaries (29–31). A, artery; V, vein. B: the nonlinear analog circuit used to analyze each vessel flow. PIV, intravascular pressure; PEV, extravascular pressures. R(t), vessel (time-varying) resistance; C(t), vessel (time-varying) capacitance. The entire network flow was analyzed based on the conditions of mass conservation both within each vessel and at each network junction (open circles). C: the vessel-in-myocardium micromechanical submodel. The in situ vessel D-P relationship was determined using a nonlinear finite deformation stress analysis of the vessel inside a cylinder of the myocardium. The analysis accounts for the measured stress-free (unloaded and free of residual stress) configuration of the two cylinders (left). Right, the submodel-predicted sigmoid (Eq. 2) D-P curve in an unpressurized 1.3-mm-diameter vessel (solid line) and comparison with coronary data (19) (error bars). x-axis, ΔP (equal to PIV − PEV, in mmHg); y-axis, diameter normalized relative to zero-pressure diameter (1.3 mm). D: each network vessel was subject to an PEV, which was previously found (1) to stem from a combination of the effects of left ventricular cavity pressure (LVP; left) and contraction-induced intramyocyte pressure (38) (Eq. 3). Patm, atmospheric pressure. E: heart rate (HR), contractility, hematocrit, LVP(t), Pperf(t), and Pv(t) are inputs to the flow analysis. F: predictions of the flow analysis in terms of transmural distribution of flow and dynamic ΔP were compared with experimental data.

Flow Analysis

The reconstructed network (Fig. 2A; Supplement I) consists of microvascular subnetworks positioned at four representative myocardial wall layers between the subepicardium and subendocardium and are interconnected to the major epicardial vessels by a symmetric arterial tree (31) and a symmetric venous tree (30). The entire simulated network, consisting of vessels ranging from 0.6 mm down to 4 μm in diameter (capillaries), includes 906 vessels. Flow in each single vessel is represented by a validated (28) nonlinear lumped analog circuit (Fig. 2B), which accounts for the vascular time-varying hydraulic resistance and capacitance (28) (Supplement II). Blood viscosity was assumed to depend on hematocrit and instantaneous diameter (37). The network flow is driven by inlet and outlet epicardial pressures and was solved (in terms of PIV and flows in each vessel) by imposing conservation of mass at each bifurcation (Fig. 2B) in the dynamically compressed vessel network. The dynamic changes of each vessel compression, resistance, and capacitance (Supplement II) depend on the vessel in situ compliances and on ΔP. These were determined as outlined below.

In Situ Vessel Compliance

Vessel compliance is defined as the diameter change (ΔD) due to a change in its ΔP, with the latter being the difference between the vessel's internal and external pressures (PIV and PEV, respectively), as follows:

| (1) |

By relating vessel compliance to its diameter, both the formulation and analysis are simplified, since flow redistribution depends directly on the vessel's resistance (Fig. 1), which is a function of the vessel diameter. An alternative definition of compliance is the ratio of vessel volume change per unit pressure change (24). The latter definition is analogous to the current one (Eq. 1), since the effect of pressure on vessel diameter is much higher than the effect on vessel length (18).

Transmural compliance differences may stem from either 1) intrinsic differences, such as the observed (10) thinner subendocardial vessel walls (structural differences, Fig. 1D), or 2) differences in vessel loading (functional differences, Fig. 1D), since vessel compliance is pressure dependent (11, 19), i.e., at higher pressures, the vessel is less compliant (Fig. 1D). The differentiation between the effects of these mechanisms is potentially important since this can guide therapeutic management.

Vessel compliance (Eq. 1) is the slope of the diameter-pressure curve (Fig. 1D). The measured (19) nonlinearity of this curve implies that vessel compliance is pressure dependent. Both experimental observations of the in situ coronary vessels (19) and micromechanical modeling of the vessel in the myocardium (1) have shown that diameter-pressure curves are sigmoid in shape, as follows:

| (2) |

where D, D+, D0, and D− are the loaded, maximum inflated, zero-pressure, and maximum deflated diameters, respectively, and ΔP1/2 is the transvascular pressure corresponding to a diameter equal to the average of D+ and D−. In light of the paucity of pertinent data, the values of these four parameters were obtained for each vessel from a micromechanical submodel of the vessel in the myocardium (Fig. 2C; Supplement III), based solely on reported properties and dimensions of the vessel and myocardium with no parameter adjustment.

Transvascular Pressure

PIV values in each vessel were calculated from network flow analysis based on conservation of mass and momentum. PEV was validated in our previous study (1) to stem from the combined effect of LVP-induced interstitial pressure and contraction-induced intramyocyte pressure (38) (Fig. 2D), as follows (see Eq. 2E in Ref. 1):

| (3) |

where MRD is the myocardial relative depth, which varies between 0 (epicardium) and 1 (endocardium); α is a scale factor (Table 1) that relates myocyte contraction to PEV (1); and SSR is the sarcomere stretch ratio waveform (modified from Ref. 26). The baseline value of α was obtained from PEV measured (20) in isolated papillary muscle, whereas the SSR waveform represents the observed 16% myocyte shortening from diastole to systole (1).

Table 1.

Baseline, high, and low levels of flow determinants

| Determinant | Baseline | High | Low |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pperf, mmHg | 95/95 | 175/175 | 35/35 |

| Pperf pulse pressure, mmHg | 0 | 40 | 0 |

| Heart rate, beat/min | 90 | 120 | 60 |

| Systolic LVP, mmHg | 120 | 180 | 60 |

| Diastolic LVP, mmHg | 5 | 40 | 2.5 |

| α, mmHg/% shortening | 140 | 280 | 0 |

| In situ stretch | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

In the present study, the flow analysis scheme of Ref. 1 was extended to study subendocardial vulnerability by adding the features described below.

Transmural Differences in Vessel Wall Thickness

In addition to the longitudinal differences in vessel wall thickness (i.e., differences between vessels of different diameters and between arteries, capillaries, and veins), recent data have shown that endocardial vessel walls are ∼50% thinner than the respective epicardial vessels (10). This observation was expected to account for the generally small transmural differences in in situ vessel compliance, since in situ compliance is due to the combined effects of vessel and myocardium intrinsic mechanical properties (Fig. 2C). Even small compliance differences may affect flow distribution, however, since flow depends on the fourth power of diameters (Poiseuille's law). Hence, the simulated wall thickness of each vessel was modified in the vessel-in-myocardium micromechanical submodel to vary linearly with transmural vessel location, consistent with experimental data (10).

Other Transmural Anatomic Differences

Subendocardial perfusion in the nonbeating heart was observed (16) to be twice higher than subepicardial perfusion, which implies either larger subendocardial vessels or greater number density (24). To comply with this observation, the network was adapted in two alternative manners (24): 1) by linearly varying the vessel reference diameters (1) between 90% (at the subepicardium) to 110% (at the subendocardium) of their measured cast values (29–31) and 2) by reconstructing an alternative network consisting of two subendocardial microvascular networks for each subepicardial network (Supplement I), which represents a twofold higher vessel density in the subendocardium than in the subepicardium. In the latter case, the reference diameters were not transmurally adjusted.

The aforementioned anatomic differences between the endocardium and epicardium induce differences in vessel compliance (Fig. 3A), as predicted by the vessel-in-myocardium micromechanical submodel (Supplement III).

Fig. 3.

Vessel D-P curves predicted by the model. A: differences between subendocardial (solid line) and subepicardial (dashed line) arterioles of ∼35 μm in diameter under baseline conditions. The arrow denotes the difference in diameters at diastolic pressure (see methods). Compliance is the curve slope. B: pressure-dependent (Eq. 2; solid line) versus constant (Eq. 4; dashed line) compliance in a ∼35-μm-diameter subendocardial arteriole. C: predicted effects of in situ vessel stretch on D-P curves. The diameter at vessel cast pressure (31) is an input to the vessel-in-myocardium submodel (Supplement III) and thus remains unchanged at different stretch values. Higher vessel axial stretch induces a lower slope of the vessel D-P curve (i.e., lower vessel compliance). x-Axis, ΔP (in mmHg); y-axis: vessel diameter (in μm).

The flow analysis scheme was used to predict time-averaged ΔP ( ; expected to be lower in subendocardial vessels, hypothesis 1) and the subendocardial-to-subepicardial flow ratio (expected to decrease with perfusion pressure, hypothesis 2), as outlined below.

; expected to be lower in subendocardial vessels, hypothesis 1) and the subendocardial-to-subepicardial flow ratio (expected to decrease with perfusion pressure, hypothesis 2), as outlined below.

To study the effect of contraction on subendocardial vulnerability, flow was compared between the cases of the beating heart versus the arrested heart. To that end, contraction effects were abolished by zeroing PEV (namely, Eq. 3 becomes PEV = 0).

To study the effect of pressure-dependent vessel compliance (i.e., nonlinear diameter-pressure curve), predictions of the baseline case were compared with the hypothetical case of constant vessel compliance. To that end, compliance was taken as independent of pressure (Fig. 3B) by replacing Eq. 2 by its linear approximation as follows:

| (4) |

where Dlin is the vessel linearized pressure-dependent diameter and Dnonlin is the nonlinear diameter as calculated from Eq. 2. Maximal ΔP (ΔPmax) was taken as 160 mmHg, which satisfies Dlin = Dnonlin under the highest (160 mmHg) and lowest (−160 mmHg) pressures at which in situ diameters have been measured (19), and was varied for sensitivity analysis between half and twice this baseline value. Hypothesis 3 (effect of structural differences on flow redistribution) was tested by comparing the predicted subendocardial-to-subepicardial flow ratio with and without vascular anatomic transmural differences: lower subendocardial vessel wall thickness (10) and either larger subendocardial diameters or higher numbers of subendocardial vessels (24).

Flow Redistribution

Preliminary results indicated that Endo/Epi varies nonlinearly with perfusion pressure. Hence, flow redistribution was quantified by the Endo/Epi relative change under a 60-mmHg reduction in perfusion pressure [from 95 mmHg (baseline) to 35 mmHg; Table 1].

Flow Redistribution Under Varied Conditions

Flow analysis was performed under perturbations (Table 1) of mean and pulsatile perfusion pressure (the latter being the difference between maximum systolic and minimum diastolic pressures) and of heart rate (HR), LVP, contractility, and vessel compliance. Under baseline conditions, perfusion pressure pulsatility was taken as zero (constant perfusion pressure; Table 1) to comply with data of flow redistribution under similar conditions (9). The highest value of pulsatility was taken as 40 mmHg to avoid a diastolic venous pressure exceeding perfusion pressure at the lowest perfusion pressure examined. Changes in HR (between 60 and 120 beats/min) included the known HR effect on diastolic time fraction (15). Systolic and diastolic LVP levels were varied separately, with systolic LVP between 60 and 180 mmHg and diastolic LVP between 2.5 and 40 mmHg (increase in preload) (22). Effects of contractility were assessed by changing the scale factor α in Eq. 3 between zero and twice the baseline value. Vessels compliance depends on both vessel and myocardium nonlinear material (constitutive) laws (the three-dimensional stress-strain relationship). Each of these laws (Supplement III) has a number of material parameters. To the best of our knowledge, there are no data regarding the change of these parameters under pathologies that affect vessel compliance. Hence, compliance was altered (Fig. 3C) in the present study by varying the in situ vessel stretch (induced by vessels tethered to the myocardium via collagen struts) in the range between previously measured levels of 1.0 (25) and 1.4 (42). Changes in hematocrit [between 25% and 65% (22)] were found to have a small effect on the study results and are thus not presented.

RESULTS

Hypothesis 1: Transmural Differences in

Under baseline (beating) conditions, subendocardial vessels are subjected to more compressive loading than the respective subepicardial vessels, i.e.,  values are lower by >40 mmHg (Fig. 4A). When abolishing the effect of contraction, however, this

values are lower by >40 mmHg (Fig. 4A). When abolishing the effect of contraction, however, this  difference is considerably reduced (from >40 to 6 mmHg; Fig. 4A). Hence, myocardial contraction induces significant transmural heterogeneity in

difference is considerably reduced (from >40 to 6 mmHg; Fig. 4A). Hence, myocardial contraction induces significant transmural heterogeneity in  . The predicted 6-mmHg

. The predicted 6-mmHg  difference in the arrested condition is likely due to anatomically induced compliance heterogeneity, since by abolishing both myocardial contraction and transmural anatomic differences (in both vessel wall thickness and their diameters and number), there was no transmural difference in

difference in the arrested condition is likely due to anatomically induced compliance heterogeneity, since by abolishing both myocardial contraction and transmural anatomic differences (in both vessel wall thickness and their diameters and number), there was no transmural difference in  (results not shown). Under beating conditions, similar

(results not shown). Under beating conditions, similar  differences were predicted in both the presence and absence of transmural anatomic differences. Finally, by incorporating constant (Eq. 4) rather than pressure-dependent (Eq. 2) vessel compliance (Fig. 3B), the predicted

differences were predicted in both the presence and absence of transmural anatomic differences. Finally, by incorporating constant (Eq. 4) rather than pressure-dependent (Eq. 2) vessel compliance (Fig. 3B), the predicted  difference in beating conditions was only slightly modulated (by 10 mmHg; Fig. 4A).

difference in beating conditions was only slightly modulated (by 10 mmHg; Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Major determinants of the transmural difference in  (

( epi −

epi −  endo). A: predicted effects of myocardial contraction and of the vessel pressure-dependent (vs. constant) compliance. With contraction,

endo). A: predicted effects of myocardial contraction and of the vessel pressure-dependent (vs. constant) compliance. With contraction,  levels of vessels that perfuse the subepicardium or drain it are substantially higher than the levels of the respective subendocardial vessels, whether vessel compliance is pressure dependent (solid line) or constant (dashed line). Without contraction (dashed-dotted line), the ΔP difference is considerably lower. B: predicted effects of systolic LVP. Low levels (60 mmHg, dashed-dotted line) are predicted to substantially decrease the ΔP difference compared with normal (120 mmHg, solid line) levels. C: predicted effects of vessel compliance. High compliance (dashed-dotted line), induced by a low level (1.0) of in situ stretch (see Fig. 3C), increases the predicted ΔP difference compared with normal (1.2, solid line) in situ stretch, although the effect is predicted to be lower compared with that of systolic LVP. D: predicted effects of a Pperf reduction. Lower Pperf levels (35 mmHg, dashed-dotted line) are predicted to moderately increase the ΔP difference compared with normal (95 mmHg; solid line) Pperf. x-Axis, vessel time-averaged diameter (in μm; veins on the left of 0 and arteries on the right of 0); y-axis, difference between

levels of vessels that perfuse the subepicardium or drain it are substantially higher than the levels of the respective subendocardial vessels, whether vessel compliance is pressure dependent (solid line) or constant (dashed line). Without contraction (dashed-dotted line), the ΔP difference is considerably lower. B: predicted effects of systolic LVP. Low levels (60 mmHg, dashed-dotted line) are predicted to substantially decrease the ΔP difference compared with normal (120 mmHg, solid line) levels. C: predicted effects of vessel compliance. High compliance (dashed-dotted line), induced by a low level (1.0) of in situ stretch (see Fig. 3C), increases the predicted ΔP difference compared with normal (1.2, solid line) in situ stretch, although the effect is predicted to be lower compared with that of systolic LVP. D: predicted effects of a Pperf reduction. Lower Pperf levels (35 mmHg, dashed-dotted line) are predicted to moderately increase the ΔP difference compared with normal (95 mmHg; solid line) Pperf. x-Axis, vessel time-averaged diameter (in μm; veins on the left of 0 and arteries on the right of 0); y-axis, difference between  values of the subepicardial vessels and respective subendocardial vessels (in mmHg).

values of the subepicardial vessels and respective subendocardial vessels (in mmHg).

Determinants of transmural  differences.

differences.

Systolic LVP is the most important determinant of contraction-induced transmural differences in  . A decrease in systolic LVP from 120 to 60 mmHg (Table 1) was predicted to result in a moderate ΔP difference of 20 mmHg (Fig. 4B), whereas a decrease in diastolic LVP (from 5 to 2.5 mmHg; Table 1) did not significantly affect the ΔP difference (<2 mmHg). A reduction of in situ vessel stretch increased this contraction-dependent difference in

. A decrease in systolic LVP from 120 to 60 mmHg (Table 1) was predicted to result in a moderate ΔP difference of 20 mmHg (Fig. 4B), whereas a decrease in diastolic LVP (from 5 to 2.5 mmHg; Table 1) did not significantly affect the ΔP difference (<2 mmHg). A reduction of in situ vessel stretch increased this contraction-dependent difference in  (by ∼7 mmHg, mainly in smallest venules; Fig. 4C). A lower HR (60 instead of 90 beats/min) modestly elevated the contraction-induced difference in

(by ∼7 mmHg, mainly in smallest venules; Fig. 4C). A lower HR (60 instead of 90 beats/min) modestly elevated the contraction-induced difference in  (by 3 mmHg). The effects of perfusion pressure pulsatility and of cardiac contractility on transmural differences in

(by 3 mmHg). The effects of perfusion pressure pulsatility and of cardiac contractility on transmural differences in  were predicted to be small (<2 mmHg). Finally, a reduction in perfusion pressure (from 95 to 35 mmHg; Table 1) did not significantly affect transmural differences in

were predicted to be small (<2 mmHg). Finally, a reduction in perfusion pressure (from 95 to 35 mmHg; Table 1) did not significantly affect transmural differences in  (<2 mmHg; Fig. 4D). The effect was more prominent in arteries than in veins.

(<2 mmHg; Fig. 4D). The effect was more prominent in arteries than in veins.

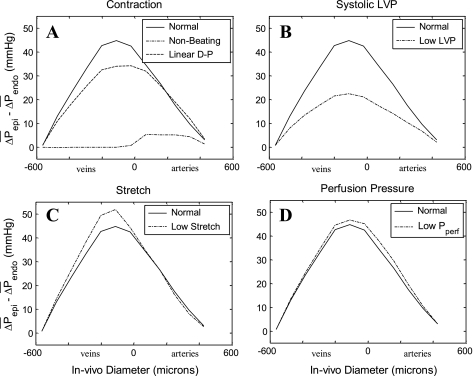

Hypothesis 2: Flow Redistribution Under Reduced Perfusion Pressure

Under baseline (beating) conditions, Endo/Epi changed by −20% (Fig. 5A) when perfusion pressure was reduced to 35 mmHg. When constant compliance was assumed (Eq. 4), however, the effect of such a reduction in perfusion pressure was abolished, i.e., Endo/Epi remained constant (Fig. 5A). Hence, myocardial contraction induces flow redistribution away from subendocardium under reduced perfusion pressure only when combined with pressure-dependent vessel compliance. Without contraction, the predicted changes of Endo/Epi with perfusion pressure were also small (−3%; Fig. 5A). These small changes represent the contribution of vessel anatomic (“structural”) differences to subendocardial vulnerability in the noncontracting and non-left ventricular pressurized heart. If we ignore both contraction and transmural vessel anatomy differences, subendocardial and subepicardial perfusions are equal, regardless of the perfusion pressure (not shown).

Fig. 5.

Predicted sensitivity of Endo/Epi to major flow determinants. A: dependence of Endo/Epi on Pperf (x-axis, in mmHg). Under baseline conditions (Table 1), Endo/Epi is significantly affected by Pperf (solid line), whereas under constant compliance (linear D-P curves, Eq. 4, dashed-dotted line) or when the effect of myocardial contraction (dashed line) is ignored, the dependence is milder and baseline Endo/Epi is elevated. B: same as in A but with a focus on the effect of in situ stretch. Lower stretch (dashed-dotted line) induces a significant drop of Endo/Epi under a reduction of Pperf, whereas higher stretch (dashed line) induces the opposite effect. The data points are reproduced from Bache and Schwartz (2) (open squares), Chilian and Layne (9) (solid diamonds), and Boatwright et al. (3) (shaded circles). C: predicted sensitivity of Endo/Epi under baseline Pperf to perturbations (Table 1) in vessel compliance (CMP), HR, diastolic LVP (DLVP), systolic LVP (SLVP), cardiac contractility (CTR), and Pperf pulsatility (PPP). Solid and open columns indicate low and high values, respectively (Table 1). The horizontal solid line is the Endo/Epi level under the baseline level of the flow determinants. D: predicted sensitivity of the change of Endo/Epi under a reduction of Pperf from 95 to 35 mmHg (flow redistribution) to flow determinants. The solid horizontal line is the Endo/Epi change under baseline conditions. The effects on flow redistribution of vessel compliance (altered by varying the in situ vessel stretch between levels of 1.0 and 1.4; Table 1) can be seen to be substantial.

Other determinants of transmural flow redistribution.

The effect of in situ stretch and the associated change in vessel compliance (Fig. 3C) on flow redistribution is of pivotal importance. A large vessel compliance (associated with a vessel in situ stretch of 1.0 instead of 1.2; Table 1) induced a 67% decrease in Endo/Epi under the 60-mmHg reduction in perfusion pressure. In contrast, smaller than baseline compliance (at an in situ stretch of 1.4) induced the opposite effect of a 68% increase in the subendocardial-to-subepicardial flow ratio (Fig. 5B). Measured data of Endo/Epi (2, 3, 9) (Fig. 5B) were in agreement with the baseline in situ stretch level of 1.2, which was used in the present study (Table 1).

A number of pharmacologically controllable parameters were predicted to affect flow redistribution as well. A reduction in HR from 90 to 60 beats/min induced both an increase in Endo/Epi (from 1.0 to 1.2; Fig. 5C) and a milder flow redistribution (from −20% to −13% Endo/Epi change under a 60-mmHg pressure reduction; Fig. 5D). Similarly, a reduction of either systolic LVP (from 120 to 60 mmHg) or diastolic LVP (from 5 to 2.5 mmHg) resulted in both increased Endo/Epi (to 1.3 and 1.03, respectively; Fig. 5C) and a decreased flow redistribution (−14% and −18% change, respectively; Fig. 5D). Conversely, a smaller contractility was predicted to decrease baseline Endo/Epi (to 0.95; Fig. 5C) and to increase redistribution (−26% change; Fig. 5D). A perfusion pressure pulsatility of 40 mmHg was predicted to lower baseline Endo/Epi (to 0.8; Fig. 5C) and to increase redistribution (−38% change; Fig. 5D).

Hypothesis 3: Effect of Transmural Differences in Vascular Anatomy

If we ignored the observed distribution in vessel wall thickness (10) and further assumed no transmural differences in vessel diameters and number density, Endo/Epi at 95-mmHg perfusion pressure dropped from 1.0 to 0.6 (Fig. 6). Under this homogeneous anatomy, flow redistributed only modestly (Endo/Epi change by −9% under the 60-mmHg pressure reduction compared with the −20% change under baseline anatomy). Hence, regional anatomic differences that induce regional differences in vascular compliance (Fig. 3A) enhance flow redistribution in the beating heart.

Fig. 6.

Anatomic determinants of subendocardial vulnerability in the beating heart. Shown are the predicted Endo/Epi under baseline (95 mmHg; Table 1) Pperf (open bars, left y-axis scale) and its change with a reduction (to 35 mmHg) of Pperf (solid bars, right y-axis scale) under the following anatomic conditions: 1) no transmural differences in diameter, vessel wall thickness, and vessel number density (D=,WT=,N = ); 2) thinner subendocardial vessel wall thickness (10), homogeneous diameters, and a higher number of subendocardial vessel (D=,WT↓,N↑); 3) thinner subendocardial vessel walls (10), homogeneous diameters, and no differences in vessel number (D=,WT↓,N = ); and 4) no transmural differences in vessel wall thickness and vessel numbers but larger subendocardial diameters (D↑,WT=,N = ). Under baseline anatomy (horizontal line), the subendocardial vessel wall is thinner and subendocardial vessel diameters are assumed to be larger than the respective subepicardial vessel diamters. The baseline vessel number is taken to be homogeneous (D↑,WT↓,N = ). The reported heterogeneity in wall thickness induces higher flow redistribution, i.e., a higher Endo/Epi decrease, as seen by the comparison of anatomic condition 4, solid bar, against the horizontal reference line. Transmural heterogeneity in diameters (anatomic condition 3 vs. the horizontal line) or in vessel numbers (anatomic condition 2 vs. 3) substantially affects Endo/Epi under baseline Pperf (open bars) but only modestly affects flow redistribution (solid bars).

If we ignored the observed (10) transmural differences in vessel wall thickness but incorporated larger subendocardial diameters (as in baseline), Endo/Epi at 95-mmHg perfusion pressure changed from 1.0 at baseline to 1.05, but flow redistribution was diminished (to a −6% change) compared with baseline (Fig. 6). Collectively, these two predictions imply that the observed transmural differences in wall thickness enhance flow redistribution.

If we assumed no transmural differences in vessel diameters or number density but accounted for the thinner subendocardial wall thickness, Endo/Epi at 95-mmHg perfusion pressure was substantially lower than at baseline (0.55 instead of 1.0). Hence, diameter differences between subendocardial and subepicardial vessels (associated with an Endo/Epi level of 1.0) equalize transmural flow under physiological conditions in the beating heart. On the other hand, flow redistribution without transmural diameter differences was still substantial (Fig. 6) and close to baseline.

If a greater vessel number density was assigned to the subendocardial microvessels of orders 5 to −5 (30, 31) and to the respective penetrating vessels of orders 8 to 5 (31) and orders −5 to −8 (30) compared with the subepicardium vessels, the flow redistribution was similar to that of the case of larger subendocardium vessel diameter (baseline anatomy), although Endo/Epi at 95-mmHg perfusion pressure became higher (from 1.0 to 1.15; Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

This study explores the mechanism underlying the ischemic vulnerability of the subendocardium to reduced perfusion pressure. The major findings are that 1) myocardial contractions induce lower ΔP in subendocardial compared with subepicardial vessels and 2) this transmural difference in ΔP, when coupled with vascular pressure-dependent compliance, results in a redistribution of blood flow away from the subendocardium when perfusion pressure is reduced. The results also suggest that the observed transmural differences in vascular wall thickness further enhance this flow redistribution.

Transvascular Pressures

Myocardial contractions result in transmural variations in PEV (Eq. 3). The results suggest that PEV induces significantly lower (more compressive) ΔP values in deeper myocardial layers (Fig. 4A). Low LVP reduces PEV mainly in the subendocardium (Eq. 3) and hence moderates the predicted ΔP transmural variation (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the transmural variation in ΔP decreases when the HR is reduced due to the associated lower time fraction of systolic compression (15). In contrast, changes in contractility levels affect PEV similarly at all vessels (Eq. 3) and consequently maintain the same level of transmural difference relative to normal conditions. A drop in perfusion pressure reduces PIV similarly in the subepicardium and subendocardium, albeit more prominently in arteries than in veins (Fig. 4D) due to the more distal longitudinal location of the latter.

Although direct experimental data are unavailable, Hoffman et al. (23) speculated that subendocardial ΔP values are lower than epicardial ΔP values due to the combined effect of external (systolic) compression, blood viscosity, and vessel compliance, a combination that results in systolic blood flow away from the subendocardium. The present analysis supports and quantifies (Fig. 4) this hypothesis based on a detailed micromechanical flow analysis. Based on lymphatic data, Fibich et al. (13) speculated that PEV is only partially (∼75%) transmitted into the coronary capillary lumen (13). This again implies lower ΔP values for the subendocardium, since PEV values are higher there than in the subepicardium (Eq. 3).

Transmural Perfusion

Under physiological conditions (baseline; Table 1), contraction-induced lower ΔP levels in the subendocardial vasculature (Fig. 4A) induce a higher compliance there (Fig. 1D). Hence, a perfusion pressure reduction is predicted to decrease subendocardial diameters more prominently than subepicardial diameters and to change the transmural distribution of coronary resistance and perfusion.

Accordingly, a higher vasculature compliance (obtained by a decrease in vessel in situ stretch, see methods) is predicted to increase the tendency to redistribute the flow (Fig. 5D). In addition, a higher compliance increases the subepicardial diameters more prominently than subendocardial diameters because of the lower ΔP levels in the latter, and thus Endo/Epi will decrease (Fig. 5C).

A lower LVP is predicted to reduce subendocardial extravascular loading more prominently compared with subepicardial loading (Eq. 3; Fig. 4B). Under such conditions, two effects occur: 1) subendocardial diameters increase compared with normal LVP levels, and thus Endo/Epi increases (Fig. 5C); and 2) the compliance of subendocardial vasculature decreases, such that a reduced perfusion pressure affects vascular diameters more homogeneously than under normal LVP levels, i.e., the coronary flow redistribution is reduced (Fig. 5D).

Under lower HRs, the diastolic time fraction increases (15), and thus the time-averaged extravascular compression is decreased. Hence, a low HR induces effects that are qualitatively similar to those of lower LVP levels (Fig. 5, C and D).

An intriguing relation between the effects of contractility and perfusion pressure on arterial and venous transmural compliance is shown in Fig. 7: under high contractility, both arterial and venous ΔP levels decrease in magnitude (Fig. 7, A and B, respectively). In arteries, such ΔP decreases result in a vessel narrowing that is more substantial in the subendocardium than in the subepicardium (Fig. 7A). In contrast, a reduced venous pressure substantially narrows subepicardial but not subendocardial venous diameters (Fig. 7B). This is due to the convexity of the sigmoid diameter-pressure curves under venous (low) ΔP levels. Hence, the greater narrowing of subepicardial veins (compared with endocardial veins) counteracts the smaller narrowing of epicardial arteries. The predicted Endo/Epi increase under higher than baseline contractility levels (α = 280 mmHg/% shortening; Fig. 5C) is thus due to the higher influence of the venous countereffect (Fig. 7C) on total flow (compared with the effect of arteries). In contrast to higher contractility, a 20-mmHg reduction in perfusion pressure similarly affects arterial ΔP levels (Fig. 7A) but hardly affects venous ΔP levels (Fig. 7B). The total network response to a perfusion pressure reduction is thus influenced mainly by arterial diameter changes (Fig. 7C), which tend to decrease Endo/Epi (Fig. 5B). The venous countereffect is not predicted under changes of LVP or HR levels since both changes do not significantly affect subepicardial pressures, and thus the venous diameter changes are correspondingly small.

Fig. 7.

Effect of contractility on coronary diameters. A: predicted diameters in representative subendocardial and subepicardial arterioles. Symbols indicate  in each vessel as predicted by the flow analysis. Diameters were determined from the corresponding D-P curves in the subendocardium (solid line) and subepicardium (dashed line). Under baseline conditions (squares; Table 1), both subendocardial and subepicardial vessel diameters are 0.1 mm. Under high contractility (change of scale factor α in Eq. 2 from 140 to 280 mmHg/% shortening; diamonds), the vessel diameter decreases (compared with baseline; arrowheads) more prominently in the subendocardium than in the subepicardium due to the higher slope (i.e., compliance) of subendocardial D-P curve. Similar diameter changes occur under reduced Pperf (from 95 to 75 mmHg; circles). x-Axis, ΔP (in mmHg); y-axis, vessel diameter (in mm). B: predicted diameters in representative subendocardial and subepicardial venules. In the venules, high contractility reduces the predicted ΔP in both subepicardial and subendocardial veins. Subepicardial diameters decrease accordingly, whereas subendocardial diameters are hardly affected by the contractility-induced pressure change, due to the low slope of the D-P curve. In contrast, reduced Pperf hardly changes the predicted pressures and diameters since their ΔP is little affected by Pperf. C: longitudinal distribution of the transmural difference in diameter changes. The predicted decrease in arterial diameters due to contractility elevation (CTR; dashed line) is up to 5% higher in the subendocardium than in the subepicardium, whereas the reduction in subepicardial venous diameters is up to 10% higher than in subendocardial venous diameters. In contrast, after a Pperf reduction (solid line), the reduction in subepicardial venous diameters is only mildly lower than in subendocardial venous diameters. x-Axis, vessel time-averaged diameter (in μm; veins on the left of 0 and arteries on the right of 0); y-axis, difference between the predicted diameter change in vessels feeding the endocardium and epicardium (EndoD change − EpiD change).

in each vessel as predicted by the flow analysis. Diameters were determined from the corresponding D-P curves in the subendocardium (solid line) and subepicardium (dashed line). Under baseline conditions (squares; Table 1), both subendocardial and subepicardial vessel diameters are 0.1 mm. Under high contractility (change of scale factor α in Eq. 2 from 140 to 280 mmHg/% shortening; diamonds), the vessel diameter decreases (compared with baseline; arrowheads) more prominently in the subendocardium than in the subepicardium due to the higher slope (i.e., compliance) of subendocardial D-P curve. Similar diameter changes occur under reduced Pperf (from 95 to 75 mmHg; circles). x-Axis, ΔP (in mmHg); y-axis, vessel diameter (in mm). B: predicted diameters in representative subendocardial and subepicardial venules. In the venules, high contractility reduces the predicted ΔP in both subepicardial and subendocardial veins. Subepicardial diameters decrease accordingly, whereas subendocardial diameters are hardly affected by the contractility-induced pressure change, due to the low slope of the D-P curve. In contrast, reduced Pperf hardly changes the predicted pressures and diameters since their ΔP is little affected by Pperf. C: longitudinal distribution of the transmural difference in diameter changes. The predicted decrease in arterial diameters due to contractility elevation (CTR; dashed line) is up to 5% higher in the subendocardium than in the subepicardium, whereas the reduction in subepicardial venous diameters is up to 10% higher than in subendocardial venous diameters. In contrast, after a Pperf reduction (solid line), the reduction in subepicardial venous diameters is only mildly lower than in subendocardial venous diameters. x-Axis, vessel time-averaged diameter (in μm; veins on the left of 0 and arteries on the right of 0); y-axis, difference between the predicted diameter change in vessels feeding the endocardium and epicardium (EndoD change − EpiD change).

The biophysical basis of vessel diameter-pressure curves deserves consideration. Under positive ΔP values, the curve is concave, since inflation induces circumferential stretch of the vessel wall and its surrounding myocardium and consequent circumferential stiffening (e.g., Fig. 7A, right). Conversely, compressive ΔP values (Fig. 7A, left) induce stretch (and consequent stiffening) of the vessel-tethering collagen struts (7), resulting in curve convexity. Hence, in situ coronaries are expected to remain patent under such negative pressures (19). This prediction is consistent with the fact that in vivo coronary collapse has not been observed (21, 24).

Subendocardial Vulnerability

Several mechanisms have been previously proposed to account for the underlying mechanisms of subendocardial vulnerability to hypoperfusion. In one study (2), it was attributed to transmural differences in backpressures. As indicated above, whether such differences exist and are large enough is still unknown (22, 23). In the present study, an anatomically based coronary network was considered where both subendocardium and subepicardium vessels were connected through conduit veins to the same large epicardial veins, thus sharing a common “global” backpressure (23).

Subendocardial vulnerability was also attributed (8) to lower “local” driving pressures, due to the larger pressure drop over the subendocardial (compared with subepicardial) conduit arterioles (orders 8 to 6) and venules (orders −8 to −6). If the transmural compliance differences are not considered, however, the transmural difference in vessel resistance is not expected to change under reduced perfusion pressure, and thus the local and global (aortic − right atrial) driving pressures are likely to change proportionally. Hence, the mechanism of lower local driving pressures alone cannot account for the observed (2, 3, 9) change in Endo/Epi under reduced perfusion pressure.

Another previous hypothesis to account for subendocardial vulnerability is the systolic/diastolic interaction (23), which was thought to induce a systolic blood translocation from the endocardium to epicardium (14). This concept does not specifically address the effect of changes in mean perfusion pressure on the transmural distribution of vascular flow and resistances. In the systolic/diastolic interaction hypothesis, Endo/Epi is expected to remain at its baseline level regardless of the mean perfusion pressure level, which is not in agreement with published data (2, 3, 9).

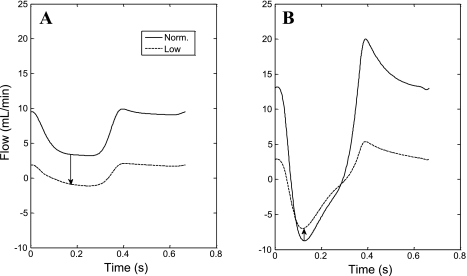

Observations of subendocardial retrograde flows during systole (40) support a systolic blood shift from the subendocardium to subepicardium. Our model predictions are in good agreement with these observations (Fig. 8) (1). For systolic blood shift to induce a reduction in Endo/Epi under reduced perfusion pressure, however, the amount of redistributed blood must increase. In contrast, the present results imply that systolic retrograde flow hardly changes in magnitude in the subendocardium (Fig. 8A) but is highly diminished in the epicardium (Fig. 8B) under a reduced perfusion pressure. In fact, these results imply that it is the diastolic flow reduction (being more prominent in the endocardium) that induces the overall drop in Endo/Epi under reduced perfusion pressure.

Fig. 8.

Predicted dynamic flow waveforms in large arteries. A: flow waveform in a 450-μm-diameter artery perfusing the external half of the myocardial wall under normal and reduced (low) Pperf (from 95 to 35 mmHg; Table 1). B: flow waveform in a 450-μm-diameter artery perfusing the internal half of the myocardium under similar conditions. Both arteries share a common inlet. In the former vessel, the reduced Pperf attenuates flow during the entire cardiac cycle, whereas systolic flow in the latter hardly changes (arrows).

The original intramyocardial pump model (39), which did not consider differences between subendocardial and subepicardial flow and thus could not predict Endo/Epi changes, was later (4) extended to represent flow in several myocardial layers. Each compartment was assumed to feature a sigmoid pressure-volume relation. The study, however, did not address Endo/Epi changes with perfusion pressure. Furthermore, the different myocardial layers were decoupled, in contrast to the true coronary anatomy. A subsequent study (41) imposed empirically based (15) higher subendocardial changes in resistance due to pressure changes (i.e., higher subendocardial vessel compliance). The physical origins of the higher subendocardial compliance were not considered, however, due to the empirical, lumped model. Finally, Klocke (32) presented a combined waterfall intramyocardial pump model. The model did not consider transmural differences in vascular resistance and flow under a reduction of perfusion pressure.

Anatomic Heterogeneity Affects Perfusion Distribution

In the beating heart, vascular anatomic differences, namely, larger vessel diameters and thinner vessel walls in the subendocardium (Fig. 3A), have been shown to significantly enhance flow redistribution (from −9% Endo/Epi change under homogeneous anatomy to −20% Endo/Epi change under baseline anatomy; Fig. 6) under a 60-mmHg reduction in perfusion pressure. In the diastolic heart, however, the predicted effect of anatomic differences is less significant (from 0% Endo/Epi change under homogeneous anatomy to −3% Endo/Epi change under larger vessel diameters and thinner vessel walls in the subendocardium; Fig. 5A). This modest effect of anatomic differences in diastole is likely due to the small differences [as predicted by the vessel-in-myocardium submodel (Fig. 3A) and measured in isolated coronaries (33)] between subepicardial and subendocardial vessel compliances in the high-pressure region.

Clinical Implications

The present study examined the effects of clinically relevant factors such as HR, LVP, and contractility on subendocardial vulnerability. The results imply that a pharmacological reduction of HR, in addition to reducing myocardial metabolic demand, is predicted to enhance subendocardial blood supply as follows: 1) by increasing total coronary flow, 2) by increasing Endo/Epi (Fig. 5C), and 3) by decreasing the redistribution of blood away from the subendocardium (Fig. 5D).

Under severe aortic valve stenosis, systolic LVP is considerably higher than aortic (i.e., coronary perfusion) pressure. The treatment of valve stenosis should thus result in both lower systolic LVP and possibly higher coronary perfusion pressure. Both effects are predicted (Fig. 5) to be beneficial for subendocardial coronary flow (27).

In contrast, pharmacological reduction of afterload reduces simultaneously both the aortic (coronary perfusion) pressure and the systolic LVP level. The effect on subendocardial perfusion is more complex, as the former reduction diminishes subendocardial supply, whereas the latter increases it (Fig. 5). Our model predicts that the effect of aortic pressure is more significant than the systolic LVP effect, i.e., when both pressures are simultaneously reduced by 60 mmHg from their baseline level (Table 1), the total coronary flow drops to 20% of its respective baseline level.

Elevated diastolic LVP, often observed in patients with congestive cardiomyopathy, is predicted to compromise both total and especially subendocardial flow (Fig. 5), in line with previous observations (22).

Study Limitations

The present study considers a nonautoregulated (fully dilated) vascular bed, since flow redistribution was observed only under these conditions (2, 3, 9). In the autoregulated state, vascular tone is likely to counterbalance the higher passive reduction of subendocardial vessel diameters, by an increased reduction of smooth muscle tension. Thus, the effect on Endo/Epi will not be observed up to a certain point at which the capacity of subendocardial autoregulation is exhausted. This process agrees with the observed (6) tendency of subendocardial autoregulation to be exhausted first.

Vascular compliance cannot be deduced from in vivo (40) or in situ (16) diameter measurements unless ΔP is simultaneously measured. Moreover, most of the available simultaneous pressure and diameter data are from isolated vessels (11), even though collagen tethering (7) has been shown (19) to significantly affect in situ vessel compliance. To cope with this paucity in data, the present study used diameter-pressure curves obtained from the micromechanical vessel-in-myocardium stress analysis (Eq. 2; Supplement III). It was assumed that these curves, which fit (Fig. 2C) in situ measurements in large coronary arteries (19), are also valid for capillaries and veins.

Structural differences affecting vessel in situ compliance were assumed to stem from transmural differences in vascular anatomy, i.e., diameters (24), vessel numbers (24), and wall thickness (10). Additional possible factors may include vessel and myocardium constitutive properties and residual strains. Subendocardial tissue has been proposed (34) to be more compliant than the subepicardium, due to the higher compliance of subendocardial coronary vessels. Such higher subendocardial compliance is expected to increase regional compliance differences (Fig. 3A), which supports the present conclusions.

The effect of vessel and myocardium systolic shortening on vessel diameter-pressure curves was not considered in the present study, since it was previously found (1) to have only a modest contribution.

Each flow determinant was altered separately in the present sensitivity analysis. In reality, however, such separation seldom occurs as these determinants are interrelated. For example, a perfusion pressure reduction has been shown (17) to diminish cardiac contractility (“Gregg effect”). The magnitude of the Gregg effect and the conditions under which it occurs are presently unclear (43). For example, with autoregulation intact, its magnitude is minimal (43). Thus, this secondary effect of a perfusion pressure reduction was not included in the present analysis. If considered, the Gregg effect is predicted to increase hypoperfusion-induced flow redistribution (since under low perfusion pressure, reduced contractility decreases Endo/Epi; Fig. 5, C and D), thus reinforcing the study conclusions. Furthermore, the nonlinear resistance of epicardial stenosis (44) implies that perfusion pressure affects not only  but also its pulsatility. This secondary effect is also predicted to have no qualitative significance on flow redistribution (Fig. 5D) and is thus not expected to alter the study conclusions.

but also its pulsatility. This secondary effect is also predicted to have no qualitative significance on flow redistribution (Fig. 5D) and is thus not expected to alter the study conclusions.

Conclusions

A novel mechanism was proposed to explain subendocardial vulnerability to acute coronary stenosis. Using a validated coronary flow analysis based on physical principles and on realistic coronary anatomy, it was found that the subendocardial vulnerability to hypoperfusion stems from the combined effects of cardiac contraction, vascular pressure-dependent compliance, and potential transmural differences in vessel anatomy. These results may be of significant clinical relevance as they provide a rational basis for clinical strategies such as a reduction in HR and treatment of aortic valve stenosis to reduce LVP.

GRANTS

This work was supported by United States of America-Israel Binational Science Foundation Grant 2003-095 and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-055554-12.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental Material for this article is available at the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology website.

REFERENCES

- 1. Algranati D, Kassab GS, Lanir Y. Mechanisms of myocardium-coronary vessel interaction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H861–H873, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bache RJ, Schwartz JS. Effect of perfusion pressure distal to a coronary stenosis on transmural myocardial blood flow. Circulation 65: 928–935, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boatwright RB, Downey HF, Bashour FA, Crystal GJ. Transmural variation in autoregulation of coronary blood flow in hyperperfused canine myocardium. Circ Res 47: 599–609, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bruinsma P, Arts T, Dankelman J, Spaan JA. Model of the coronary circulation based on pressure dependence of coronary resistance and compliance. Basic Res Cardiol 83: 510–524, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buckberg GD, Fixler DE, Archie JP, Hoffman JI. Experimental subendocardial ischemia in dogs with normal coronary arteries. Circ Res 30: 67–81, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Canty JM, Jr, Klocke FJ. Reduced regional myocardial perfusion in the presence of pharmacologic vasodilator reserve. Circulation 71: 370–377, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caulfield JB, Borg TK. The collagen network of the heart. Lab Invest 40: 364–372, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chilian WM. Microvascular pressures and resistances in the left ventricular subepicardium and subendocardium. Circ Res 69: 561–570, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chilian WM, Layne SM. Coronary microvascular responses to reductions in perfusion pressure. Evidence for persistent arteriolar vasomotor tone during coronary hypoperfusion. Circ Res 66: 1227–1238, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choy JS, Kassab GS. Wall thickness of coronary vessels varies transmurally in the LV but not the RV: implications for local stress distribution. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H750–H758, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cornelissen AJ, Dankelman J, VanBavel E, Stassen HG, Spaan JA. Myogenic reactivity and resistance distribution in the coronary arterial tree: a model study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1490–H1499, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Downey JM, Kirk ES. Inhibition of coronary blood flow by a vascular waterfall mechanism. Circ Res 36: 753–760, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fibich G, Lanir Y, Liron N. Mathematical model of blood flow in a coronary capillary. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 265: H1829–H1840, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flynn AE, Coggins DL, Goto M, Aldea GS, Austin RE, Doucette JW, Husseini W, Hoffman JI. Does systolic subepicardial perfusion come from retrograde subendocardial flow? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H1759–H1769, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fokkema DS, VanTeeffelen JW, Dekker S, Vergroesen I, Reitsma JB, Spaan JA. Diastolic time fraction as a determinant of subendocardial perfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2450–H2456, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goto M, Flynn AE, Doucette JW, Jansen CM, Stork MM, Coggins DL, Muehrcke DD, Husseini WK, Hoffman JI. Cardiac contraction affects deep myocardial vessels predominantly. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1417–H1429, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gregg DE. Effect of coronary perfusion pressure or coronary flow on oxygen usage of the myocardium. Circ Res 13: 497–500, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo X, Kassab GS. Variation of mechanical properties along the length of the aorta in C57bl/6 mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H2614–H2622, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hamza LH, Dang Q, Lu X, Mian A, Molloi S, Kassab GS. Effect of passive myocardium on the compliance of porcine coronary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H653–H660, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heslinga JW, Allaart CP, Yin FC, Westerhof N. Effects of contraction, perfusion pressure, and length on intramyocardial pressure in rat papillary muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H2320–H2326, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hiramatsu O, Goto M, Yada T, Kimura A, Chiba Y, Tachibana H, Ogasawara Y, Tsujioka K, Kajiya F. In vivo observations of the intramural arterioles and venules in beating canine hearts. J Physiol 509: 619–628, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoffman JI. Transmural myocardial perfusion. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 29: 429–464, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoffman JI, Baer RW, Hanley FL, Messina LM. Regulation of transmural myocardial blood flow. J Biomech Eng 107: 2–9, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoffman JI, Spaan JA. Pressure-flow relations in coronary circulation. Physiol Rev 70: 331–390, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holzapfel GA, Sommer G, Gasser CT, Regitnig P. Determination of layer-specific mechanical properties of human coronary arteries with nonatherosclerotic intimal thickening and related constitutive modeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H2048–H2058, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hurst JW, Logue RB. The Heart, Arteries, and Veins. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970, p. 77 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iwanaga S, Ewing SG, Husseini WK, Hoffman JI. Changes in contractility and afterload have only slight effects on subendocardial systolic flow impediment. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H1202–H1212, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jacobs J, Algranati D, Lanir Y. Lumped flow modeling in dynamically loaded coronary vessels. J Biomech Eng 130: 054504, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kassab GS, Fung YC. Topology and dimensions of pig coronary capillary network. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H319–H325, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kassab GS, Lin DH, Fung YC. Morphometry of pig coronary venous system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H2100–H2113, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kassab GS, Rider CA, Tang NJ, Fung YC. Morphometry of pig coronary arterial trees. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 265: H350–H365, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klocke FJ, Mates RE, Canty JM, Jr, Ellis AK. Coronary pressure-flow relationships. Controversial issues and probable implications. Circ Res 56: 310–323, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kuo L, Davis MJ, Chilian WM. Myogenic activity in isolated subepicardial and subendocardial coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 255: H1558–H1562, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. May-Newman K, Omens JH, Pavelec RS, McCulloch AD. Three-dimensional transmural mechanical interaction between the coronary vasculature and passive myocardium in the dog. Circ Res 74: 1166–1178, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mittal N, Zhou Y, Linares C, Ung S, Kaimovitz B, Molloi S, Kassab GS. Analysis of blood flow in the entire coronary arterial tree. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H439–H446, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moir TW. Subendocardial distribution of coronary blood flow and the effect of antianginal drugs. Circ Res 30: 621–627, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gessner T, Sperandio MB, Gross JF, Gaehtgens P. Resistance to blood flow in microvessels in vivo. Circ Res 75: 904–915, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rabbany SY, Funai JT, Noordergraaf A. Pressure generation in a contracting myocyte. Heart Vessels 9: 169–174, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Spaan JA, Breuls NP, Laird JD. Diastolic-systolic coronary flow differences are caused by intramyocardial pump action in the anesthetized dog. Circ Res 49: 584–593, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Toyota E, Ogasawara Y, Hiramatsu O, Tachibana H, Kajiya F, Yamamori S, Chilian WM. Dynamics of flow velocities in endocardial and epicardial coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1598–H1603, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van den Wijngaard JP, Kolyva C, Siebes M, Dankelman J, van Gemert MJ, Piek JJ, Spaan JA. Model prediction of subendocardial perfusion of the coronary circulation in the presence of an epicardial coronary artery stenosis. Med Biol Eng Comput 46: 421–432, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang C, Garcia M, Lu X, Lanir Y, Kassab GS. Three-dimensional mechanical properties of porcine coronary arteries: a validated two-layer model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1200–H1209, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Westerhof N, Boer C, Lamberts RR, Sipkema P. Cross-talk between cardiac muscle and coronary vasculature. Physiol Rev 86: 1263–1308, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Young DF. Fluid mechanics of arterial stenoses. J Biomech Eng 101: 157–175, 1979 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.