Abstract

The phosphoprotein (P) of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) interacts with nascent nucleoprotein (N), forming the N0–P complex that is indispensable for the correct encapsidation of newly synthesized viral RNA genome. In this complex, the N-terminal region (PNTR) of P prevents N from binding to cellular RNA and keeps it available for encapsidating viral RNA genomes. Here, using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), we show that an isolated peptide corresponding to the 60 first N-terminal residues of VSV P (P60) and encompassing PNTR has overall molecular dimensions and a dynamic behavior characteristic of a disordered protein but transiently populates conformers containing α-helices. The modeling of P60 as a conformational ensemble by the ensemble optimization method using SAXS data correctly reproduces the α-helical content detected by NMR spectroscopy and suggests the coexistence of subensembles of different compactness. The populations and overall dimensions of these subensembles are affected by the addition of stabilizing (1M trimethylamine-N-oxide) or destabilizing (6M guanidinium chloride) cosolvents. Our results are interpreted in the context of a scenario whereby VSV PNTR constitutes a molecular recognition element undergoing a disorder-to-order transition upon binding to its partner when forming the N0–P complex.

Keywords: rhabdovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, phosphoprotein, SAXS, NMR, intrinsically disordered proteins, molecular recognition element

Introduction

In the last decade, our understanding of the relationships between protein structure and function was revolutionized by the discoveries that numerous proteins are intrinsically disordered (IDPs) or contain intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) and that these disordered proteins are implicated in various biological functions.1–5 These findings continuously raise new challenges in structural biology for predicting IDPs or IDRs from the amino acid sequence and for characterizing their structural properties. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy6–8 and small-angle scattering9,10 revealed to be particularly suitable for providing detailed structural information on these proteins. Various algorithms were developed for identifying IDPs or for locating IDRs.11,12 Complete genome surveys revealed that not all kingdoms of life are equal when we consider the abundance of IDPs and IDRs encoded in the genomes. A large fraction (20–40%) of eukaryote genomes encodes IDP or proteins containing long IDRs, whereas they are much less abundant (<10%) in archea and bacteria.13–15 Viruses, and in particular RNA viruses, occupy an intermediate position between eukaryotes and bacteria and exhibit a high rate of loosely packed proteins.16

The Rhabdoviridae is a family of nonsegmented negative-sense RNA viruses, which includes human (rabies virus—RV), animal (vesicular stomatitis virus—VSV), and plant pathogens. The machinery of RNA transcription and replication of these viruses is composed of the genomic RNA and of three viral proteins: the nucleoprotein (N), the phosphoprotein (P), and the large subunit of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L). The RNA genome is encapsidated by N. Every N binds to nine nucleotides, forming a long helical N–RNA complex17 that serves as a template for both transcription and replication.18 The crystal structure of circular N–RNA complexes of both VSV and RV revealed that the N protein contains a N-terminal domain (NNTD) and a C-terminal (NCTD) domain separated by a positively charged groove, which binds the RNA.19,20 NNTD and NCTD act like jaws that close around and completely enwrap the RNA, forming multiple salt bridges with the phosphate backbone of the RNA. The phosphoprotein (P) is involved in different stages of the viral replication process.21,22 First, it associates with the L protein, forming active RNA polymerase complexes that catalyze both transcription and replication of the viral genome. In these complexes, L carries out the RNA synthesis and the 5′ and 3′ RNA processing required for the production of messenger RNAs, whereas P acts as an essential cofactor21 by attaching L to its N–RNA template.23,24 P possesses binding sites for both L and the N–RNA complex and thus ensures the correct positioning of the polymerase onto its template. Second, P is essential for encapsidating newly synthesized RNA genomes.25–27 P binds to nascent N molecules, forming a N0–P complex (the superscript 0 denotes the absence of RNA), which prevents N from binding to cellular RNAs and maintains N in a soluble form, available for the encapsidation of newly synthesized RNA genomes.22,25,27–30 In both VSV and RV P, the N-terminal region of the protein (PNTR), residues 4–40 in RV and residues 11–30 in VSV, is sufficient for maintaining N in a soluble and monomeric form.29,30 Because PNTR is rich in negatively charged residues, it was hypothesized that PNTR binds in the RNA-binding cavity of N,29,31 thereby preventing the nonspecific attachment of N0 to cellular RNA.

Recently, we showed that both RV and VSV P form dimers in solution32 and are modular proteins made of structured domains and IDRs.12 The consensus prediction of disordered regions in both RV and VSV P obtained by combining results from different disorder predictors suggested that the 39 N-terminal amino acids of VSV P and the 52 N-terminal amino acids of RV P are structured,12,33 whereas the following residues (aa 40–90 in VSV; aa 53–86 in RV) would be disordered. However, in a previous study, an isolated peptide corresponding to the N-terminal region of RV P (RV P68; aa 1–68) appeared to be disordered in solution.12 Static light scattering revealed that RV P68 was monomeric, its Stokes' radius measured by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) corresponded to that expected for an unfolded protein of the same molecular mass, and its mean secondary structure content measured by circular dichroism (CD) was less than 5%.12 These contradicting features, namely predictions of a folded domain in P68 and experimental results showing that P68 is disordered in solution, are reminiscent of some recently identified short protein motifs that fold only upon binding to their partners and were named molecular recognition elements (MoREs) or molecular recognition features.34–37

To further investigate the structural properties of the N-terminal region of P, we studied a peptide corresponding to the 60 N-terminal residues of VSV P (P60) by NMR spectroscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). We choose to work with a peptide of this length to ascertain that it extends beyond the N0-binding region (PNTR)30 and the N-terminal region that was predicted to be structured.12 Also, an equivalent peptide of 60 residues was shown to inhibit more efficiently the transcription and replication in RV than a peptide corresponding to the 40 N-terminal residues.38 Although the NMR spectra recorded with VSV P60 exhibit typical features of disordered proteins, transiently formed secondary structures were identified from NMR chemical shifts and the dynamics of the polypeptide chain was probed by 15N relaxation rates. In addition, the average compactness of P60 was probed by SAXS, and a conformational ensemble that accounts for all experimental observations was built by modeling SAXS data with the ensemble optimization method (EOM). Also, the effects of denaturing or stabilizing cosolvents on the size distribution of the representative ensemble were measured by SAXS. Our results revealed that, in solution, P60 is a highly dynamic protein transiently forming α-helical elements and populating compact conformers that could play a major role in the formation of the N0–P complex.

Results

Isolated VSV P60 is intrinsically disordered but exhibits transient secondary structures

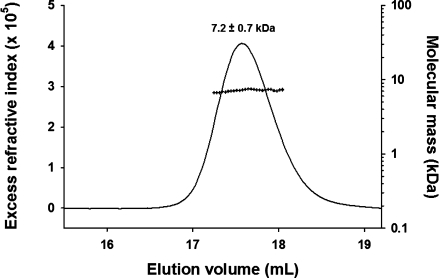

The N-terminal domain of VSV P (P60, aa 1–60) was produced in Escherichia coli as a recombinant protein containing a C-terminal His-tag (8 aa). The long-term stability of P60 was significantly improved in the presence of a mixture of 50 mMl-Arg and 50 mMl-Glu.39 Under these conditions, an average molecular mass of 7.2 ± 0.7 kDa was determined by SEC combined with detection by multiangle laser light scattering and refractometry (SEC/MALLS/RI), indicating that P60 was monomeric (MM calculated from the sequence = 8054 Da) and well behaved in solution up to concentrations of 2 mM (Fig. 1). Its Stokes' radius of 2.3 ± 0.1 nm indicated an extended conformation, closer to that expected for an unfolded protein of the same molecular mass (RS = 2.5 nm) than to that expected for a globular protein (RS = 1.5 nm).40

Figure 1.

Molecular mass and Stokes' radius of isolated VSV P60 measured by SEC/MALLS/RI. The line shows the SEC elution profile as monitored by refractometry (left axis). The crosses show the molecular mass calculated from light scattering and refractometry data across the elution peak (right axis). The Stokes's radius (RS) was determined from the elution volume by calibrating the system with standard proteins of known Stokes' radius (see Materials and Methods).

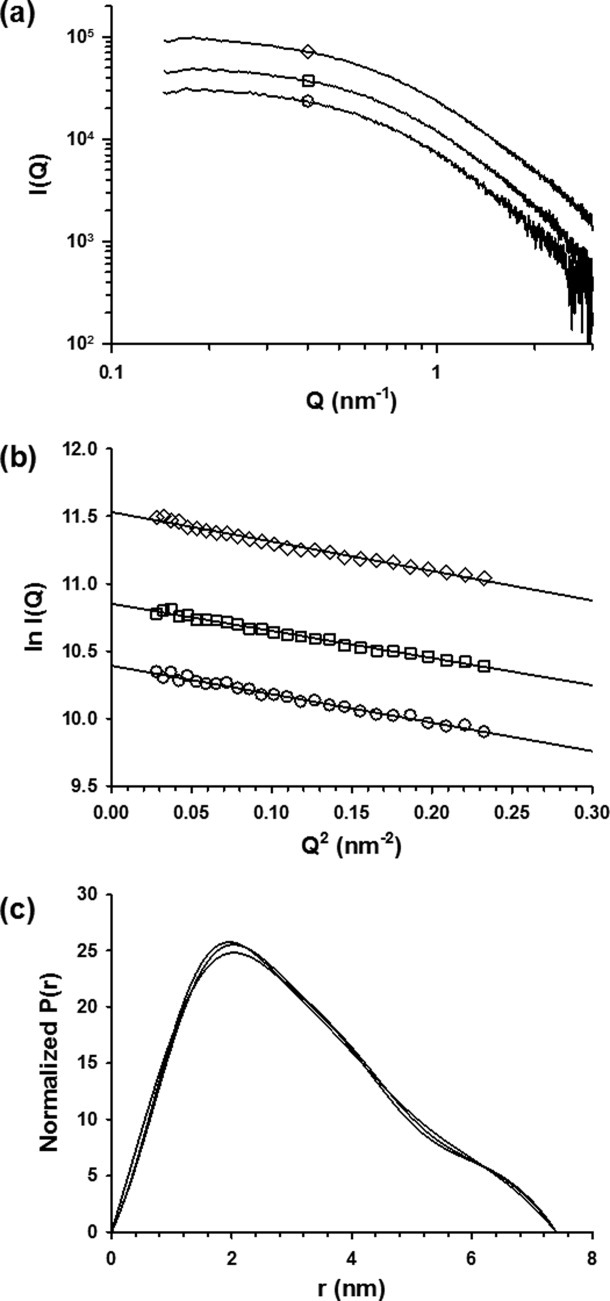

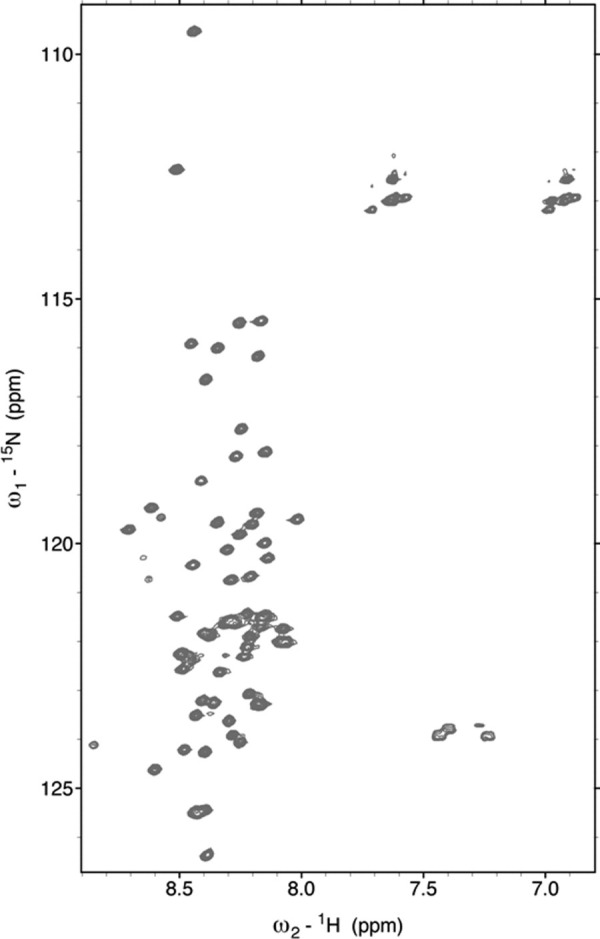

SAXS profiles of P60 were collected for scattering vector values (Q = 4π(sinθ)/λ) ranging from 0.1 to 3.0 nm−1 over a concentration range of 5–18 mg mL−1. The profiles obtained at different protein concentrations had the same shape and were flat at low Q values, indicating the absence of significant aggregation [Fig. 2(a)]. The radius of gyration, Rg, values derived from the Guinier approximation at low Q value (Q.Rg < 1.4) [Fig. 2(b)] or from the distance distribution function (P(r)) [Fig. 2(c)] showed no significant dependence on protein concentration, confirming the absence of aggregation (Table I). The average Rg value of 2.4 ± 0.1 nm was close to the value of 2.5 nm calculated for a random coil of 68 amino acids (peptide + His-Tag) according to Flory's power-law dependence on chain length [(2)] and using parameters predicted for a random coil with excluded volume41 and to the value of 2.3 nm calculated from the same power-law dependence using parameters derived from experimental measurements of Rg for IDPs.10 The forward scattering intensity, I(0), was proportional to protein concentration and yielded an estimated molecular mass of 11 ± 1 kDa, in agreement with SEC/MALLS/RI measurements, confirming that P60 was monomeric and well behaved in solution. The 2D 1H-15N-HSQC NMR spectrum of P60 exhibited narrow line widths and poor dispersion of the amide proton chemical shifts (Fig. 3), in agreement with structural disorder in solution. These results indicate that VSV P60 has overall molecular dimensions and NMR spectroscopic properties of a disordered protein, as shown previously for RV P68.12

Figure 2.

Small-angle X-ray scattering experiments. (a) Scattering curve of P60 recorded at different concentrations. In this panel and in panels b and c, the protein concentration was 5 mg mL−1 (circles), 8 mg mL−1 (squares), or 18 mg mL−1 (diamonds). (b) Guinier plot. The fitted lines using 0.10 < Q < 0.28 nm−1 yield the radii of gyration shown in Table I. The fit corresponds to a range of 0.5 < Q.Rg < 1.5. The I(0) value calculated from the intercept together with protein concentrations yielded a molecular mass estimate of 11 ± 1 kDa. (c) Distance distribution function. The distance distribution functions were calculated with GNOM by using Dmax values shown in Table I. The surface areas under the curves were normalized to account for the differences in protein concentration.

Table I.

Molecular Dimensions Calculated from SAXS Data

| Cosolvent | Protein concentration (mg mL−1) | Rg (Guinier) (nm) | Rg (P(r)) (nm) | Dmax (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 mM Arg/ 50 mM Glu | 5 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 |

| 8 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 | |

| 18 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 | |

| 10 mM Arg/ 10 mM Glu | 5 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 7.9 |

| 6M GdmCl | 5 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 8.2 |

| 1M TMAO | 5 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 7.0 |

Rg values were determined from the Guinier plot or from the distance distribution function (P(r) vs. r). Dmax values beyond which P(r) = 0 were adjusted in order that the Rg values obtained with the program GNOM agree with those obtained from the Guinier analysis.

Figure 3.

2D [1H-15N]-HSQC NMR spectrum of VSV P60. The spectrum was recorded in 20 mM Tris, pH 6.0, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Arg, and 50 mM Glu at 10°C.

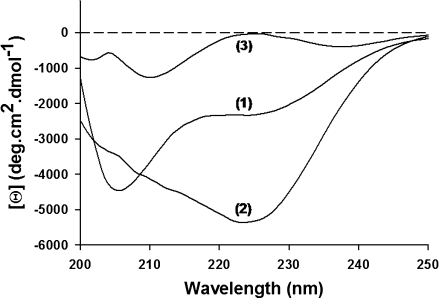

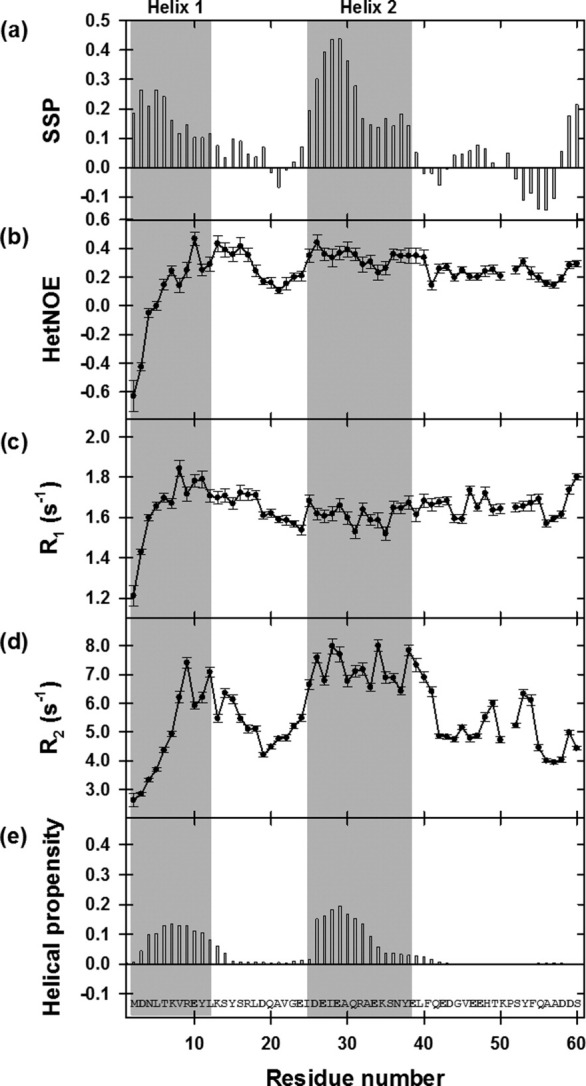

The far-UV CD spectrum exhibited a prominent shoulder near 222 nm and a minimum near 205 nm, suggesting the presence of α-helical structure (Fig. 4). Assuming that the molar ellipticity value at 222 nm reports only on the presence of α-helix, the average helical content of P60 was estimated to be 7%.12,42 NMR spectroscopy is highly sensitive to local structure and therefore provides information about the location and population of fluctuating secondary structures within an otherwise flexible protein.8,43–47 After complete assignment of the backbone nuclei (Cα, Cβ, C′, N, and HN), the chemical shifts and 15N nuclear relaxation rates were used to identify transient structural features within P60. The secondary structure propensity (SSP) calculated by combining secondary chemical shifts of Cα and Cβ showed continuous stretches of positive propensity (SSP > 0.1) for residues 2–12 (helix 1) and 25–38 (helix 2), with the highest population in the region 25–31, suggesting the presence of residual helical structures in these two regions of the protein [Fig. 5(a)].45 It also showed a stretch of negative propensity for residues 53–57 characteristic of an extended β structure. Averaging these propensities over P60 yielded α-helical and β-structure contents of 9 and 1%, respectively, in good agreement with the helical content estimated from the CD spectrum. The uniformly low values of the heteronuclear {1H}-15N NOEs indicated high backbone flexibility on the picosecond to nanosecond time scale [Fig. 5(b)]. The presence of transient secondary structures is, however, suggested from the 15N nuclear relaxation rates, R1 and R2 [Fig. 5(c,d)]. In particular, the 15N R2 rates are larger in the regions of the peptide that have helical propensity according to the SSP score. The regions 3–14 and 26–34 of P60 exhibited significant intrinsic helical propensity [Fig. 5(e)],48,49 and amino acids that can accept hydrogen bonds from free backbone amide groups and have high N-capping preferences50 were found at the N-terminal extremity of each helical segment. The program AGADIR predicted intrinsic N-capping propensities near 5% for Asp2 and Asn3 (Ncap for helix 1) and of 13.5% for Asp25 (Ncap for helix 2).48,49 These results suggest that the fluctuating helical elements are locally encoded in the amino acid sequence and stabilized by short-range interactions.

Figure 4.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy of VSV P60. CD spectra were recorded at 20°C in 20 mM Tri-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 50 mM Arg and 50 mM Glu (1), 1M TMAO (2), or 6M GdmCl (3).

Figure 5.

NMR dynamics of isolated VSV P60. (a) Secondary structure propensity (SSP). The SSP parameter was calculated from Cα and Cβ secondary chemical shifts. (b) {1H}-15N heteronuclear NOEs. (c, d) Relaxation rates of longitudinal, R1, and transverse, R2, magnetization of backbone 15N nuclei. The shaded area highlights the regions predicted to be helical from the SSP parameter (aa 2–12 and 24–39). NMR data were recorded at 600 MHz and 10°C using a peptide sample in 20 mM Tris, pH 6.0, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Arg, and 50 mM Glu. (e) Intrinsic helical propensity. Bar graph showing the intrinsic helical propensity per residue calculated with the program AGADIR.48

To probe the effect of the remaining part of P on the conformation of the N-terminal region, we recorded an NMR spectrum of full-length VSV P. Because the full-length protein aggregates at low pH, the NMR spectrum was obtained at pH 7.5. VSV P is a dimer of 62 kDa, but only a limited number of narrow amide backbone resonances were observed with a restricted 1H chemical shift dispersion (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Although these resonances were not assigned, the spectral features suggest that only residues located in flexible regions of VSV P were visible. A comparison with an NMR spectrum of P60 recorded under identical conditions showed that most of the resonances visible at pH 7.5 match with resonances of full-length VSV P. These results clearly argued that the N-terminal part of VSV P is also globally disordered in the context of the full-length dimeric protein.

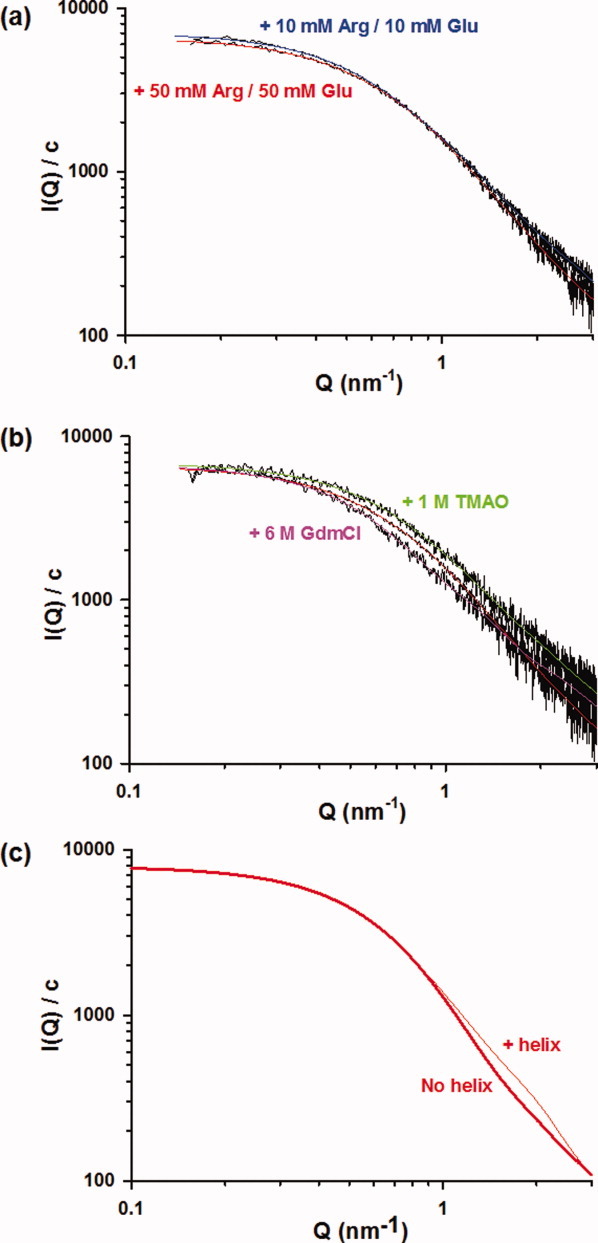

Modeling VSV P60 as a conformational ensemble

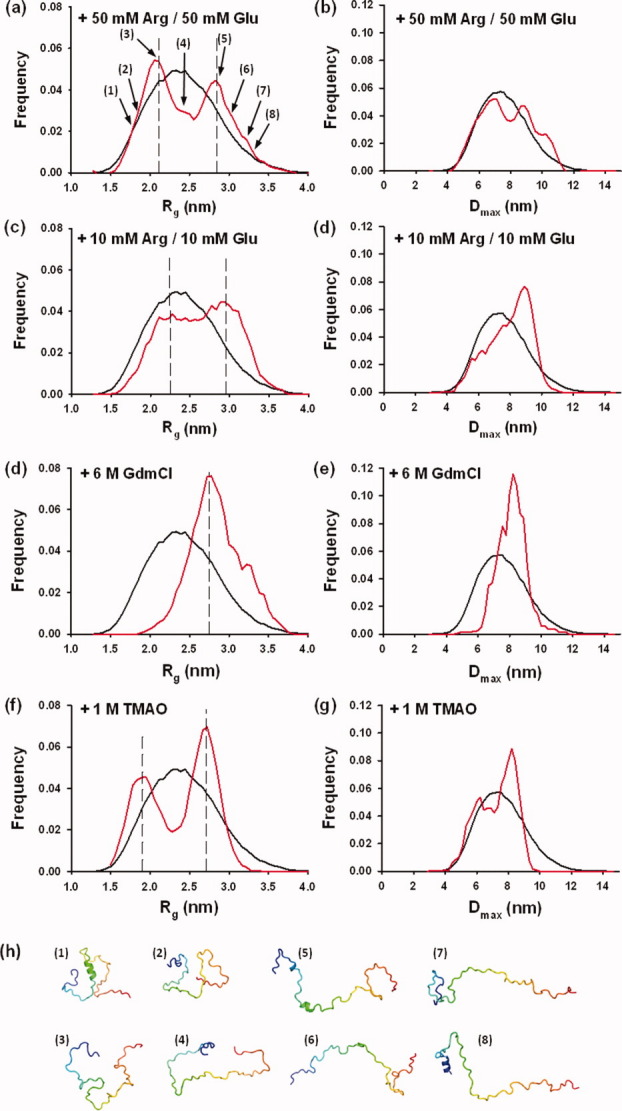

Recently, different methods were developed for building low-resolution models based on SAXS data.51–54 Many of these ab initio methods are not suitable for modeling highly flexible molecules because they yield a unique structure that at best would provide an average model of the most frequent conformers present in solution.55,56 Because VSV P60 appeared as a disordered protein with fluctuating helical structures, we used the EOM9 (Fig. 6). This method starts from a large ensemble of randomly generated conformers and selects a subensemble of conformers that collectively reproduces the experimental SAXS data and represents the distribution of structures adopted by the protein in solution.9 Based on the location of residual helical elements identified by NMR spectroscopy, an initial ensemble of 4500 conformers of P60 was built using the Flexible Meccano algorithm57 by pooling an ensemble of 500 conformers containing no helical structure with eight ensembles, of 500 conformers each, containing helices of different lengths (helix 1: aa 2–9 or 2–19, helix 2: aa 25–32 or 25–38) as described in Materials and Methods. The black curves in Figure 6 show the Rg and Dmax distributions calculated for the initial ensemble of conformers. These distributions are broad and slightly asymmetrical, with Rg values extending from 1.4 to 4.0 nm with a maximum frequency near 2.3 nm [Fig. 6(a)] and with Dmax values extending from 4.0 to 12.0 nm with a maximum frequency near 7.3 nm, respectively [Fig. 6(b)]. A subensemble of 20 conformers was selected for which the average back-calculated SAXS curve reproduced correctly the experimental curve (χ = 0.630) [Fig. 7(a)]. The red curves in Figure 6 show the Rg and Dmax distributions of the EOM-selected subensemble. They have widths similar to those of the initial ensemble as expected for a disordered P60 [red curve in Fig. 6(a,b)]. Figure 6(i) shows representative members of the selected ensemble exhibiting varying Rg values as indicated in Figure 6(a). However, the Rg distribution within the selected ensemble exhibited two maxima suggesting the presence of two distinct and almost equally important subpopulations of conformers with average Rg values centered on 2.0 and 2.9 nm [Fig. 6(a)]. The Dmax distribution is not as clearly bimodal [Fig. 6(b)]. Variation in the number of conformers selected by the EOM procedure from 50 to 2 had no significant effect on the quality of the fit and yielded similar bimodal distributions of Rg values (data not shown). The presence of helical elements in the models introduced specific features in the scattering curve at Q values above 1 nm−1 [Fig. 7(c)], and therefore, the average helix content of the selected ensemble of about 7% was in good agreement with estimations obtained from CD and NMR. Models containing helical elements were found in both subpopulations of compact and extended conformers [Fig. 6(a,i)]. Successive and independent selections by EOM yielded similar results and similar ensembles of conformers showing that the bimodal distribution of the selected ensemble was reproducible. Also, a similar bimodal distribution was obtained independently by using another initial ensemble of 10,000 conformers devoid of any explicit secondary structure generated with the program RanCh9 (data not shown). A simulation indicated that, at least under some conditions, the program EOM is capable of revealing the existence of two different populations of different average size (Supporting Information Fig. S2). The EOM approach thus revealed features in the disordered ensemble that could not be detected from the average dimensions measured as RS by SEC or as Rg by SAXS. In our case, the overall ensemble has average dimensions close to those calculated from random-coil statistics,10,41,58 whereas the EOM approach suggested the coexistence of two different subensembles with molecular dimensions lower and higher than those predicted for a random coil.

Figure 6.

Conformational ensemble selection and effects of stabilizing and destabilizing cosolutes. Ensembles of 20 conformers that collectively reproduce the experimental curves were selected from the initial ensemble. In each figure, the black curve shows the Rg and Dmax distributions calculated for the initial ensemble of conformers, whereas the red curve shows the Rg and Dmax distributions of the selected ensemble that fit the experimental SAXS data. (a) Rg and (b) Dmax distribution from the EOM analysis in 50 mM Glu and 50 mM Arg. (c) Rg and (d) Dmax distribution from the EOM analysis in 10 mM Glu and 10 mM Arg. (e) Rg and (f) Dmax distributions from the EOM analysis in 6M GdmCl. (g) Rg and (h) Dmax distributions from the EOM analysis in 1M TMAO. (i) Members of the conformational ensemble. The cartoon models show some of the selected models at varying Rg values, highlighting the presence of residual helical structures. The chains are colored from the N-terminal (blue) to the C-terminal (red). The numbers refer to their position in the distribution shown in Figure 6(a).

Figure 7.

Reproducing SAXS curves. (a) Effects of Arg and Glu on the SAXS curve of P60. The SAXS curve in 50 mM Arg and 50 mM Glu was obtained at three different protein concentrations (Fig. 2), and the EOM analysis was performed on the curve at 5 mg mL−1 to allow direct comparison with SAXS curves obtained in 10 mM Arg/10 mM Glu, 1M TMAO, and 6M GdmCl that were also obtained at 5 mg mL−1. The fitted curve calculated using the EOM procedure for P60 in 10 mM Arg/10 mM Glu is shown in blue and that in 50 mM Arg/50 mM Glu is shown in red. Data were recorded at 20°C in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, buffer containing the corresponding cosolutes. (b) Effects of 1M TMAO and 6M GdmCl on the SAXS curve of P60. The fitted curve calculated using the EOM procedure for P60 in 50 mM Arg/50 mM Glu is shown in red, that in 1M TMAO in green, and that in 6M GdmCl in magenta. Data were recorded at 20°C in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, buffer containing the corresponding cosolutes. (c) Simulated SAXS curves of ensembles containing different amounts of helical elements. The curves are average SAXS profiles calculated for the 500 models that contain no helical elements (no helix) and for the 500 models that contain helices in the regions 2–19 and 25–38 (32% helical content).

To test the effect of Arg and Glu, we also recorded SAXS data in the presence of 10 mM Arg/10 mM Glu. The average Rg value was slightly larger (2.6 ± 0.1 nm) than in 50 mM Arg/50 mM Glu, indicating that these cosolutes induce the compaction of the protein. The SAXS profile was also different [Fig. 7(a)], and the selected ensemble obtained with EOM showed a different distribution of population [Fig. 6(c,d)]. Although the Rg and Dmax distributions of the selected ensemble conserved a similar width than in 50 mM Arg and 50 mM Glu, the two subpopulations were not as clearly individualized, showing that a higher concentration of these cosolutes stabilizes the more compact subensemble.

The addition of stabilizing (trimethylamine-N-oxide, TMAO) or destabilizing (guanidinium chloride, GdmCl) cosolutes induced variations in the average helical content as shown by far-UV CD spectroscopy (Fig. 4). In 1M TMAO, a well-known stabilizing cosolute,59 the ellipticity at 222 nm indicated a higher helical content (15%), whereas in 6M GdmCl, it indicated a lower helical content (<1%). These cosolutes also affected the average size of P60, and analysis of the SAXS profiles yielded a higher average Rg values of 2.9 ± 0.1 nm in 6M GdmCl and a lower average Rg value of 2.3 ± 0.1 nm in 1M TMAO (Table I). The back-calculated SAXS curve from the ensemble of 20 conformers selected by the program EOM also adequately reproduced the experimental curve in the presence of these cosolutes [Fig. 7(b)]. The modeling of SAXS curves using the program EOM revealed that the variations of the average Rg value arose from changes in the subpopulations of compact and expanded conformers and from slight variations of the average Rg values of these two subpopulations. In the presence of 6M GdmCl, the subpopulation of compact conformers completely disappeared, and the width of the selected distributions was significantly reduced [Fig. 6(e,f)] when compared with those in 50 mM Arg/50 mM Glu [Fig. 6(a,b)]. A single maximum was observed in both distributions of Rg and Dmax [Fig. 6(e,f)] with a maximum frequency at Rg value near 2.7 nm and Dmax value near 8.2 nm. These values were slightly lower than the Rg and Dmax values found for the extended subpopulation observed in the presence of 50 mM Arg/50 mM Glu, suggesting that the subensemble with the highest average Rg value contained extended conformers that could not be further unfolded by addition of 6M GdmCl. The Rg value of 2.9 nm found for this subensemble is larger than that of 2.5 nm predicted for a random coil of this size in a good solvent41 and also larger than that of 2.3 for an IDP of this size.10 Because P60 has a high negative net charge at neutral pH, this discrepancy could result from charge repulsion leading to an expansion of the molecule.60 GdmCl can act as both denaturant and salt and, therefore, could reduce repulsions between charged residues by screening charges, a behavior which would explain the little compaction of the structural ensemble observed in 6M GdmCl.

By contrast, in the presence of 1M TMAO, both subensembles remained equally populated [Fig. 6(g)]. They became slightly more compact than in 50 mM Arg/50 mM Glu with maximal frequencies centered on Rg values of 1.9 and 2.7 nm in agreement with the smaller experimental average Rg and Dmax values measured directly from the SAXS curves (Table I). The distribution of Dmax values in the selected ensemble also appeared slightly bimodal with a maximum at a Dmax value of 8.2 nm and a shoulder near 6.2 nm [Fig. 6(h)]. Also, in the presence of 1M TMAO, the models selected by the EOM procedure contained more residual α-helical structure in average and longer helices (the average helical content in the selected ensemble was 30%) (data not shown) in agreement with CD experiments.

Discussion

The conformational ensemble representing P60

The narrow line widths in the NMR spectrum and the limited chemical shift dispersion reflect the rapid interconversion between heterogeneous conformations of VSV P60.15N relaxation experiments show that the protein is highly flexible with the exception of two regions, aa 2–12 and aa 25–38, that exhibit an increased level of order. This observation is supported by secondary chemical shifts that indicate that both regions transiently populate α-helical conformations. The presence of α-helix is confirmed by CD spectrum, and the SSP parameter derived from the Cα and Cβ chemical shifts provides an estimate of the time and ensemble average population of these helical elements near 9%. Short elements of secondary structure such as α-helices, β-strands, or turns are locally encoded and often stable in water.61–63 α-Helices form very quickly in the 10- to 100-ns time range in agreement with the timescale probed by 15N relaxation measurements.64 NMR experiments thus provide a dynamic picture of P60 where the polypeptide chain is highly flexible but populates fluctuating α-helices in two regions.

The hydrodynamic radius of P60 measured by SEC and its radius of gyration measured by SAXS are close to those expected for denatured proteins58 or for IDPs10 of the same size. The dimensions of both classes of proteins follow power-law dependences on chain length characteristic of random-coil behavior.65,66 However, the random-coil model is insensitive to the presence of stiff elements in an otherwise flexible chain, and the presence of transient formation of α-helical elements in a disordered polypeptide chain is coherent with random-coil statistics,41,67,68 as already pointed out by Tanford66 and demonstrated by simulations.41,69 The size distribution (Rg) of our selected ensemble has a width similar to that of the initial ensemble, showing that P60 samples a global conformational space predicted for a random coil although it contains on average 9% of fluctuating α-helices.

Recently, using NMR and SAXS experiments, unfolded or IDPs have been modeled as structural ensembles to convey the highly dynamic character of these proteins.9,36,44,57,70 Here, we combined information from NMR experiments showing the existence of two fluctuating α-helical elements with SAXS data to build an ensemble of 20 different conformations that together represent the dynamic structural organization of VSV P60. The ensemble of 20 conformations selected by fitting the SAXS curve exhibits an average helical content in agreement with estimations obtained by CD and NMR and correctly captures the dynamical behavior of the polypeptide chain. The structure of the selected models must, however, be considered with care. The models selected by the EOM procedure only represent plausible conformers that together reproduce the SAXS data. They should by no means be taken as actual structures. No correlation has been found between the presence of helical conformation and the size of the conformers, and residual helical structures are found in conformers of different compactness. This argues that α-helices in P60 are stabilized by local interactions as suggested by the predicted and observed propensity of the amino acid sequence to form helices in solution and, therefore, their presence is independent of the compactness of the peptide chain. However, it is also probable that the information content of SAXS data is insufficient to correlate the presence of helical structure with the degree of compaction of the chain.

In addition, a detailed analysis of the population distribution in the EOM-selected ensemble and the effects of denaturing and stabilizing cosolutes suggest the coexistence of two distinct subpopulations with different degrees of compactness. The EOM proved capable of revealing the coexistence of two subpopulations exhibiting a large difference in Rg value.71 Here, we used a simulation to demonstrate that EOM is also capable of distinguishing between unimodal and bimodal distributions under certain conditions (Supporting Information Fig. S2). In our approach, the addition of cosolutes was not intended to mimic physiological conditions although the intracellular medium is complex and contains large concentrations of various cosolutes. The addition of 50 mM Arg/50 mM Glu was used to improve solubility and prevent aggregation,39 and the addition of TMAO and GdmCl was used to probe the conformational space accessible to P60. The mechanism by which Arg and Glu achieve their effects has not been clearly demonstrated.39,72 Because the effects are observed at low concentration of cosolutes, they may result from binding to protein surface, and it has been suggested that the charges of the cosolutes interact with opposite charges on the protein surface, while the hydrophobic parts of the amino acids mask exposed hydrophobic patches.39 In another study, it was suggested that Arg and Glu induce the ordering of residues at the protein surface and act as crowding agents.72 In our case, the addition of 50 mM Arg and 50 mM Glu increases the population of compact conformers and therefore reduces the average size of the molecule.

The addition of TMAO or GdmCl was used to probe the conformational space that is accessible to the polypeptide chain and revealed how the peptide adapts to variations of the environment. Addition of GdmCl and TMAO changes the average size of the molecule and the population distribution selected by the EOM program. In particular, in 6M GdmCl, the width of the size distribution is substantially reduced and the distribution becomes unimodal [Fig. 6(e)], whereas in 1M TMAO, the bimodal distribution becomes more clearly visible [Fig. 6(g)]. These results suggest the presence of one subpopulation that is more compact than that predicted by random-coil statistics and one that is more expanded. Some IDPs are more compact than predicted from random-coil statistics because of the presence of long-range interactions involving hydrophobic clusters,73,74 hydrogen bonding,75 or charge–charge attractions.60,76 Others appear more expanded because of charge–charge repulsions.77–79 Charge–charge interactions thus seem to play a critical role in modulating the dimensions of the conformational ensemble of IDPs60,76; repulsions between like charges can lead to the expansion of the peptide chain, whereas attractions between opposite charges can lead to collapse. VSV P60 is rich in charged residues, containing 15 acidic residues (D and E), seven basic residues (K and R), and one histidine residue (net charge at neutral pH of −7 or −8 if H is charged or neutral) and therefore different interactions between charged residues could explain the existence of the two different conformational subensembles. The salt properties of GdmCl can explain the disappearance in 6M GdmCl of the compact subensemble if its formation is driven by opposite charge interactions. Conversely, TMAO favors compaction of random coils,80 and we observed slight reductions of the average dimensions of both selected conformational subensembles. Also, TMAO induces helix formation,81 and we observed a larger α-helical content as judged by CD spectroscopy and a higher number of models containing helical elements in the EOM-selected ensemble.

In conclusion, our data show that P60 is highly flexible and has overall molecular dimensions of a random-coil chain, but it contains helical structures and can adopt compact and extended conformers. The presence of fluctuating helical elements and of a distinct population of compact conformers suggests that P60 may exist in conformers that prefigure its structure in the N0–P complex and could be involved in the recognition of N0. However, the distribution of population observed here in vitro depends on environmental conditions and need not reflect the distribution under physiological conditions. Also, in its natural context, the peptide is part of a large dimeric protein, and although our data indicate that P60 is also flexible and disordered in full-length VSV P, it is possible that the remaining part of P influences the distribution of population of the two ensembles.

Role for a MoRE in the chaperone function of P

The discovery here that, in solution, P60 populates preorganized conformers containing helical elements suggests a mechanism by which PNTR could fold upon binding to its N0 partner.3 PNTR could thus be a MoRE, that is, a short motif within a disordered protein that promotes binding to a partner.36,37,82–84 Structural ensembles of disordered proteins that fold upon binding to a partner usually contain conformations similar to those adopted in the final complex.36,70,85 The fluctuating α-helices might prefigure structural elements involved in the formation of the N0–P complex. The first helix (aa 8–12) is amphipathic exposing three positively charged residues and two negatively charged residues on one face of the helix and four hydrophobic residues on the other face. The second helix (aa 25–38) is hydrophilic exposing charged residues around the helix and containing only two hydrophobic residues (I27 and Y37). Both helices could thus interact with positively charged residues lining the RNA-binding groove of N0. One might speculate that the highly flexible character of isolated P60 helps the protein to get into the RNA-binding groove and allows the correct positioning of the helical elements.

In the viral replication cycle, the N0–P complex is not an end product. It forms only transiently as an intermediate during the synthesis of new nucleocapsids. The N0-bound P must be outcompeted by the newly synthesized genomic RNA, and, therefore, the affinity of P for N0 cannot be too high. The mechanism of folding upon binding provides a means of specific recognition without the corollary of high affinity.3,86 Indeed, the folding or the adoption of a rigid structure by the ligand when it binds to its receptor will generally lead to the formation of multiple specific intermolecular interactions that confer a great specificity and, consequently, a high affinity. If the ligand is disordered in its unbound form, this strong binding energy is opposed by the high entropy of the disordered protein. We might thus speculate that, by being disordered in its free form, PNTR recognizes N0 with high specificity but moderate affinity, thus allowing its displacement by the newly synthesized viral RNA.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of VSV P60

The cDNA-encoding VSV P60 (aa 1–60) was amplified and cloned into a pET28a(+) plasmid between the NcoI and XhoI restriction sites using standard PCR techniques. A His6-tag, including a linker of two amino acids (Glu-Leu), was introduced at the C-terminal extremity. The construct was verified by standard dideoxy sequencing. The plasmid was transfected into E. coli strain BL21(DE3). 15N and 13C protein samples for NMR spectroscopy were produced in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 1.0 g L−1 of 15NH4Cl, 2.0 g L−1 of 13C glucose, and MEM vitamins (Gibco). Cells were grown in the medium containing 100 μg mL−1 of kanamycin at 37°C until OD600 reached 0.6–0.8 A.U. At this point, IPTG at a final concentration of 0.5 mM was added. After an incubation of 3 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Glu, and 50 mM Arg, pH 7.5 (Buffer A) supplemented with antiproteases (Complete™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets, Roche), and cells were disrupted by sonication. The extract was centrifuged at 20,000g during 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered (0.45 μm), loaded onto a Ni2+ resin column, and pre-equilibrated with Buffer A. The resin was washed with three bed volumes of Buffer A, then with three bed volumes of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5M NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole at pH 7.5, and the protein was eluted using Buffer A supplemented with 400 mM imidazole. The recombinant protein was loaded onto a SEC column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 prep grade, GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with Buffer A. Separations were performed at a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1. The purified protein was concentrated (Vivaspin—5000 MWCO) and stored at 4°C. The purity of the protein samples was assessed by SDS-PAGE. Protein concentration was measured by RI.

NMR spectroscopy

The resonance assignment of VSV P60 was carried out using a double-labeled (13C, 15N) sample of the peptide in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Glu, and 50 mM Arg with 10% D2O adjusted to pH 6.0 to avoid loss of resonances due to fast amide proton exchange with the solvent protons. The protein concentration was 0.9 mM. All NMR experiments were carried out at 10°C and a 1H resonance frequency of 599.67 MHz. The assignment was obtained from a series of BEST-type triple resonance experiments87,88: HNCO, intraresidue HN(CA)CO, HN(CO)CA, intraresidue HNCA, HN(COCA)CB, and intraresidue HN(CA)CB. The spectra were acquired with a sweep width of 8 kHz and 512 complex points in the 1H dimension, and a sweep width of 1.2 kHz and 32 complex points in the 15N dimension. For the 13C dimension, the spectra were acquired with a sweep width of 1.2 kHz and 60 complex points (HNCO and intraresidue HN(CA)CO), 3 kHz and 110 complex points (HN(CO)CA and intraresidue HNCA), and 10 kHz and 100 complex points (HN(COCA)CB and intraresidue HN(CA)CB). All spectra were processed with NMRPipe89 and analyzed using SPARKY.90 Automatic assignment of the resonances on the basis of the SPARKY peak lists was done using the program MARS.91

15N R1, R2 (CPMG) relaxation and {1H}-15N steady-state nuclear Overhauser effect (nOe) experiments were acquired using standard pulse sequences92 on an 15N-labeled sample of P60 with a protein concentration of 1.4 mM. The buffer conditions were as described above for the double-labeled sample. The spectra were acquired with a sweep width of 7.0 kHz and 512 complex points in the 1H dimension, and a sweep width of 1.2 kHz and 250 complex points in the 15N dimension.

The magnetization decay was sampled at (0, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1100, 1500, and 1900) ms for longitudinal and at (10, 30, 50, 70, 90, 130, 170, 210, and 250) ms for transverse relaxation, and the peak heights were used to extract the relaxation rates. To obtain estimates of the errors on the relaxation rates, a repeat measurement of one of the relaxation delays was performed in each case (600 ms for R1 and 70 ms for R2).

For the heteronuclear nOes, the amide protons were saturated using a 3-s WALTZ16 decoupling scheme that in the reference experiment was replaced by a 3-s delay. The recycle delay in both experiments was set to 2 s. Heteronuclear NOE values were obtained from the ratio between signal intensities in the saturated and the reference experiments, where the standard deviation in the noise was taken as a measure for the error in the signal intensity. The experiment was repeated twice, and the NOE values were averaged.

SEC-MALLS-RI

SEC was performed with an S75 Superdex column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris/HCl at pH 7.5 containing 150 mM NaCl. Separations were performed at 20°C with a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1. Fifty microliters of P60 solution at a concentration of 470 μM (3.8 mg mL−1) was injected. The peptide samples were prepared in the equilibration buffer supplemented with 50 mM Arg and 50 mM Glu. Online MALLS detection was performed with a DAWN-EOS detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA) using a laser emitting at 690 nm. Data were analyzed, and weight-averaged molecular masses (Mw) were calculated using the ASTRA software (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA) as described previously.32 The column was calibrated with proteins of known Stokes' radii (RS)35: bovine serum albumin (RS = 3.4 nm), RNAse A (RS = 1.9 nm), ovalbumin (RS = 3.0 nm), β-lactoglobulin (RS = 2.7 nm), and chymotrypsinogen (RS = 2.3 nm).40

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Far-UV CD spectra were recorded at 20°C on a JASCO model J-810 CD spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier temperature controller. VSV P60 was diluted to a final concentration of about 950 μM, in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Arg, and 50 mM Glu. Spectra were measured in a cuvette with a path length of 0.1 mm. After subtracting the blank signal, the CD signal (in millidegrees) was converted to mean molar residue ellipticity (in deg cm2 dmol−1), and helix content was calculated by using formalism derived from isolated peptide42 as described previously.12

Small-angle X-ray scattering experiments

The monodispersity of the samples used in SAXS experiments was checked by SEC combined with detection by MALLS and RI.32,93 SAXS data were collected at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France) on beamline ID14-3. The sample-to-detector distance was 1 m, and the wavelength of the X-rays was 0.0995 nm. Samples were contained in a 1.9-mm-wide quartz capillary. The time of exposure was optimized for reducing radiation damage. Data acquisition was performed at 20°C. Protein concentrations ranged from 5 to 18 mg mL−1. Data reduction was performed using the established procedure available at ID14-3, and buffer background runs were subtracted from sample runs.

The radius of gyration and forward intensity at zero angle (I(0)) were determined with the programs PRIMUS94 by using the Guinier approximation at low scattering vector values, Q  , in a Q Rg range up to 1.3:

, in a Q Rg range up to 1.3:

| (1) |

The forward scattering intensity was calibrated using bovine serum albumin and lysozyme as references. The radius of gyration and pairwise distance distribution function, P(r), were calculated with the program GNOM.95 The maximum dimension (Dmax) value was adjusted so that the Rg value obtained from GNOM agreed with that obtained from the Guinier analysis.

The radius of gyration, Rg, was calculated using the power-law dependence established for random-coil polymers65:

| (2) |

where R0 is the persistence length, N is the number of residues in the peptide, and ν is the exponential scaling factor. Values for R0 and ν were taken either from the random-coil polymer theory41 or from experiments with IDPs.10

A conformational ensemble of 4500 conformers was generated with the program Flexible-Meccano57 by pooling nine subensembles of 500 conformers in which helical element of different lengths were imposed in the putative helical regions of P60 identified by NMR spectroscopy as follows: Ensemble 1: no helix; Ensemble 2: aa 2–9; Ensemble 3: aa 2–19; Ensemble 4: aa 25–32; Ensemble 5: aa 25–38; Ensemble 6: aa 2–9 and aa 25–32; Ensemble 7: aa 2–9 and aa 25–38; Ensemble 8: aa 2–19 and aa 25–32; and Ensemble 9: aa 2–19 and aa 25–38. All helices were invoked with a population of 100%. Side chains for these conformations were added with the program SCCOMP.96 An optimized ensemble of conformations that agrees with the experimental SAXS data was selected from the large conformational ensemble using the EOM software.9 The size of the optimized ensemble was varied from 50 to 2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Partnership for Structural Biology for the excellent structural biology environment.

References

- 1.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:321–331. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Obradovic Z. Identification and functions of usefully disordered proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;62:25–49. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tompa P. Intrinsically unstructured proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:527–533. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uversky VN, Gillespie JR, Fink AL. Why are "natively unfolded" proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins. 2000;41:415–427. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<415::aid-prot130>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eliezer D. Biophysical characterization of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Unfolded proteins and protein folding studied by NMR. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3607–3622. doi: 10.1021/cr030403s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen MR, Markwick PR, Meier S, Griesinger C, Zweckstetter M, Grzesiek S, Bernado P, Blackledge M. Quantitative determination of the conformational properties of partially folded and intrinsically disordered proteins using NMR dipolar couplings. Structure. 2009;17:1169–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernado P, Mylonas E, Petoukhov MV, Blackledge M, Svergun DI. Structural characterization of flexible proteins using small-angle X-ray scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5656–5664. doi: 10.1021/ja069124n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernado P, Blackledge M. A self-consistent description of the conformational behavior of chemically denatured proteins from NMR and small angle scattering. Biophys J. 2009;97:2839–2845. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He B, Wang K, Liu Y, Xue B, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Predicting intrinsic disorder in proteins: an overview. Cell Res. 2009;19:929–949. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gérard FCA, Ribeiro EA, Leyrat C, Ivanov I, Blondel D, Longhi S, Ruigrok RWH, Jamin M. Modular organization of rabies virus phosphoprotein. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:978–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward JJ, Sodhi JS, McGuffin LJ, Buxton BF, Jones DT. Prediction and functional analysis of native disorder in proteins from the three kingdoms of life. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oldfield CJ, Cheng Y, Cortese MS, Brown CJ, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Comparing and combining predictors of mostly disordered proteins. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1989–2000. doi: 10.1021/bi047993o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunker AK, Obradovic Z, Romero P, Garner EC, Brown CJ. Intrinsic protein disorder in complete genomes. Genome Inform Ser Workshop Genome Inform. 2000;11:161–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tokuriki N, Oldfield CJ, Uversky VN, Berezovsky IN, Tawfik DS. Do viral proteins possess unique biophysical features? Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, Chanock RM, Melnik TP, Roizman B, Straus SE. Fields' virology. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnheiter H, Davis NL, Wertz G, Schubert M, Lazzarini RA. Role of the nucleocapsid protein in regulating vesicular stomatitis virus RNA synthesis. Cell. 1985;41:259–267. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albertini AA, Wernimont AK, Muziol T, Ravelli RB, Clapier CR, Schoehn G, Weissenhorn W, Ruigrok RW. Crystal structure of the rabies virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex. Science. 2006;313:360–363. doi: 10.1126/science.1125280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green TJ, Zhang X, Wertz GW, Luo M. Structure of the vesicular stomatitis virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex. Science. 2006;313:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.1126953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emerson SU, Yu Y. Both NS and L proteins are required for in vitro RNA synthesis by vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol. 1975;15:1348–1356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.15.6.1348-1356.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masters PS, Banerjee AK. Complex formation with vesicular stomatitis virus phosphoprotein NS prevents binding of nucleocapsid protein N to nonspecific RNA. J Virol. 1988;62:2658–2664. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2658-2664.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emerson SU, Schubert M. Location of the binding domains for the RNA polymerase L and the ribonucleocapsid template within different halves of the NS phosphoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5655–5659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellon MG, Emerson SU. Rebinding of transcriptase components (L and NS proteins). to the nucleocapsid template of vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol. 1978;27:560–567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.27.3.560-567.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peluso RW, Moyer SA. Viral proteins required for the in vitro replication of vesicular stomatitis virus defective interfering particle genome RNA. Virology. 1988;162:369–376. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peluso RW. Kinetic, quantitative, and functional analysis of multiple forms of the vesicular stomatitis virus nucleocapsid protein in infected cells. J Virol. 1988;62:2799–2807. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2799-2807.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard M, Wertz G. Vesicular stomatitis virus RNA replication: a role for the NS protein. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:2683–2694. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-10-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mavrakis M, Iseni F, Mazza C, Schoehn G, Ebel C, Gentzel M, Franz T, Ruigrok RW. Isolation and characterisation of the rabies virus N degrees-P complex produced in insect cells. Virology. 2003;305:406–414. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mavrakis M, Mehouas S, Real E, Iseni F, Blondel D, Tordo N, Ruigrok RW. Rabies virus chaperone: identification of the phosphoprotein peptide that keeps nucleoprotein soluble and free from non-specific RNA. Virology. 2006;349:422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen M, Ogino T, Banerjee AK. Interaction of vesicular stomatitis virus P and N proteins: identification of two overlapping domains at the N-terminus of P that are involved in N0-P complex formation and encapsidation of viral genome RNA. J Virol. 2007;81:13478–13485. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01244-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudson LD, Condra C, Lazzarini RA. Cloning and expression of a viral phosphoprotestructure suggests vesicular stomatitis virus NS may function by mimicking an RNA template. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:1571–1579. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-8-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gérard F, Ribeiro E, Albertini A, Zaccai G, Ebel C, Ruigrok R, Jamin M. Unphosphorylated Rhabdoviridae phosphoproteins form elongated dimers in solution. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10328–10338. doi: 10.1021/bi7007799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ribeiro EA, Jr, Favier A, Gérard FC, Leyrat C, Brutscher B, Blondel D, Ruigrok RW, Blackledge M, Jamin M. Solution structure of the C-terminal nucleoprotein-RNA binding domain of the vesicular stomatitis virus phosphoprotein. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:525–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Nature. 2007;447:920–921. doi: 10.1038/nature05858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jensen MR, Houben K, Lescop E, Blanchard L, Ruigrok RW, Blackledge M. Quantitative conformational analysis of partially folded proteins from residual dipolar couplings: application to the molecular recognition element of Sendai virus nucleoprotein. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8055–8061. doi: 10.1021/ja801332d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohan A, Oldfield CJ, Radivojac P, Vacic V, Cortese MS, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. Analysis of molecular recognition features (MoRFs) J Mol Biol. 2006;362:1043–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castel G, Chteoui M, Caignard G, Prehaud C, Mehouas S, Real E, Jallet C, Jacob Y, Ruigrok RW, Tordo N. Peptides that mimic the amino-terminal end of the rabies virus phosphoprotein have antiviral activity. J Virol. 2009;83:10808–10820. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00977-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golovanov AP, Hautbergue GM, Wilson SA, Lian LY. A simple method for improving protein solubility and long-term stability. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8933–8939. doi: 10.1021/ja049297h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uversky VN. Use of fast protein size-exclusion liquid chromatography to study the unfolding of proteins which denature through the molten globule. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13288–13298. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fitzkee NC, Rose GD. Reassessing random-coil statistics in unfolded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12497–12502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404236101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo P, Baldwin RL. Mechanism of helix induction by trifluoroethanol: a framework for extrapolating the helix-forming properties of peptides from trifluoroethanol/water mixtures back to water. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8413–8421. doi: 10.1021/bi9707133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:311–333. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90214-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen MR, Salmon L, Nodet G, Blackledge M. Defining conformational ensembles of intrinsically disordered and partially folded proteins directly from chemical shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1270–1272. doi: 10.1021/ja909973n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marsh JA, Singh VK, Jia Z, Forman-Kay JD. Sensitivity of secondary structure propensities to sequence differences between alpha- and gamma-synucleimplications for fibrillation. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2795–2804. doi: 10.1110/ps.062465306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eliezer D, Chung J, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Native and non-native secondary structure and dynamics in the pH 4 intermediate of apomyoglobin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2894–2901. doi: 10.1021/bi992545f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spera S, Bax A. Empirical correlation between protein backbone conformation and Cα and Cβ 13C nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5490–5492. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munoz V, Serrano L. Elucidating the folding problem of helical peptides using empirical parameters. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:399–409. doi: 10.1038/nsb0694-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lacroix E, Viguera AR, Serrano L. Elucidating the folding problem of alpha-helices: local motifs, long-range electrostatics, ionic-strength dependence and prediction of NMR parameters. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:173–191. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doig AJ, Baldwin RL. N- and C-capping preferences for all 20 amino acids in alpha-helical peptides. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1325–1336. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franke D, Svergun DI. DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J Appl Cryst. 2009;42:342–346. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svergun DI, Petoukhov MV, Koch MH. Determination of domain structure of proteins from X-ray solution scattering. Biophys J. 2001;80:2946–2953. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Konarev P, Petoukhov M, Volchkov V, Svergun DI. ATSAS 2.1, a program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Cryst. 2006;39:277–286. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Putnam CD, Hammel M, Hura GL, Tainer JA. X-ray solution scattering (SAXS) combined with crystallography and computation: defining accurate macromolecular structures, conformations and assemblies in solution. Q Rev Biophys. 2007;40:191–285. doi: 10.1017/S0033583507004635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernado P. Effect of interdomain dynamics on the structure determination of modular proteins by small-angle scattering. Eur J Biophys. 2010;39:769–780. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0549-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heller WT. Influence of multiple well defined conformations on small-angle scattering of proteins in solution. Acta Cryst D. 2010;61:33–44. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904025855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernado P, Blanchard L, Timmins P, Marion D, Ruigrok RW, Blackledge M. A structural model for unfolded proteins from residual dipolar couplings and small-angle x-ray scattering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17002–17007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506202102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kohn JE, Millett IS, Jacob J, Zagrovic B, Dillon TM, Cingel N, Dothager RS, Seifert S, Thiyagarajan P, Sosnick TR, Hasan MZ, Pande VS, Ruczinski I, Doniach S, Plaxco KW. Random-coil behavior and the dimensions of chemically unfolded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12491–12496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403643101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bolen DW, Baskakov IV. The osmophobic effect: natural selection of a thermodynamic force in protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:955–963. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muller-Späth S, Soranno A, Hirschfeld V, Hofmann H, Ruegger S, Reymond L, Nettels D, Schuler B. Charge interactions can dominate the dimensions of intrinsically disordered proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14609–14614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baldwin RL, Rose GD. Is protein folding hierarchic? I. Local structure and peptide folding. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:26–33. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fitzkee NC, Fleming PJ, Gong H, Panasik N, Jr, Street TO, Rose GD. Are proteins made from a limited parts list? Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Insights into the structure and dynamics of unfolded proteins from nuclear magnetic resonance. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;62:311–340. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eaton WA, Munoz V, Hagen SJ, Jas GS, Lapidus LJ, Henry ER, Hofrichter J. Fast kinetics and mechanisms in protein folding. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:327–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flory PJ. Principles of polymer chemistry. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanford C. Protein denaturation. Adv Protein Chem. 1968;23:121–282. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60401-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Millett IS, Doniach S, Plaxco KW. Toward a taxonomy of the denatured state: small angle scattering studies of unfolded proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;62:241–262. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jha AK, Colubri A, Freed KF, Sosnick TR. Statistical coil model of the unfolded state: resolving the reconciliation problem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13099–13104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506078102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller WG, Goebel CV. Dimensions of protein random coils. Biochemistry. 1968;7:3925–3935. doi: 10.1021/bi00851a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lange OF, Lakomek NA, Fares C, Schroder GF, Walter KF, Becker S, Meiler J, Grubmuller H, Griesinger C, de Groot BL. Recognition dynamics up to microseconds revealed from an RDC-derived ubiquitin ensemble in solution. Science. 2008;320:1471–1475. doi: 10.1126/science.1157092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bernado P, Perez Y, Svergun DI, Pons M. Structural characteization of the active and inactive states of Src kinase in solution by small-angle X-ray scattering. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:492–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blobel J, Schmidl S, Vidal D, Nisius L, Barnado P, Millet O, Brunner E, Pons M. Protein tyrosine phosphatase oligomerization studied by a combination of 15N NMR relaxation and 129Xe NMR. Effetc of buffer containing arginine and glutamic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5946–5953. doi: 10.1021/ja069144p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Felitsky DJ, Lietzow MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Modeling transient collapsed states of an unfolded protein to provide insights into early folding events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6278–6283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710641105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mittag T, Orlicky S, Choy WY, Tang X, Lin H, Sicheri F, Kay LE, Tyers M, Forman-Kay JD. Dynamic equilibrium engagement of a polyvalent ligand with a single-site receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17772–17777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809222105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moglich A, Joder K, Kiefhaber T. End-to-end distance distributions and intrachain diffusion constants in unfolded polypeptide chains indicate intramolecular hydrogen bond formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12394–12399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mao AH, Crick SL, Vitalis A, Chicoine CL, Pappu RV. Net charge per residue modulates conformational ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8183–8188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911107107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Uversky VN, Gillespie JR, Millett IS, Khodyakova AV, Vasiliev AM, Chernovskaya TV, Vasilenko RN, Kozlovskaya GD, Dolgikh DA, Fink AL, Doniach S, Abramov VM. Natively unfolded human prothymosin alpha adopts partially folded collapsed conformation at acidic pH. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15009–15016. doi: 10.1021/bi990752+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Permyakov SE, Millett IS, Doniach S, Permyakov EA, Uversky VN. Natively unfolded C-terminal domain of caldesmon remains substantially unstructured after the effective binding to calmodulin. Proteins. 2003;53:855–862. doi: 10.1002/prot.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Uversky VN, Li J, Souillac P, Millett IS, Doniach S, Jakes R, Goedert M, Fink AL. Biophysical properties of the synucleins and their propensities to fibrillate: inhibition of alpha-synuclein assembly by beta- and gamma-synucleins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11970–11978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Qu Y, Bolen CL, Bolen DW. Osmolyte-driven contraction of a random coil protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9268–9273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Celinski SA, Scholtz JM. Osmolyte effects on helix formation in peptides and the stability of coiled-coils. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2048–2051. doi: 10.1110/ps.0211702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bourhis JM, Johansson K, Receveur-Brechot V, Oldfield CJ, Dunker KA, Canard B, Longhi S. The C-terminal domain of measles virus nucleoprotein belongs to the class of intrinsically disordered proteins that fold upon binding to their physiological partner. Virus Res. 2004;99:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oldfield CJ, Cheng Y, Cortese MS, Romero P, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Coupled folding and binding with alpha-helix-forming molecular recognition elements. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12454–12470. doi: 10.1021/bi050736e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fuxreiter M, Simon I, Friedrich P, Tompa P. Preformed structural elements feature in partner recognition by intrinsically unstructured proteins. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gsponer J, Christodoulou J, Cavalli A, Bui JM, Richter B, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. A coupled equilibrium shift mechanism in calmodulin-mediated signal transduction. Structure. 2008;16:736–746. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schanda P, Van Melckebeke H, Brutscher B. Speeding up three-dimensional protein NMR experiments to a few minutes. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9042–9043. doi: 10.1021/ja062025p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lescop E, Schanda P, Brutscher B. A set of BEST triple-resonance experiments for time-optimized protein resonance assignment. J Magn Reson. 2007;187:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. San Francisco: University of California; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jung YS, Zweckstetter M. Mars—robust automatic backbone assignment of proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2004;30:11–23. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000042954.99056.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Farrow NA, Muhandiram R, Singer AU, Pascal SM, Kay CM, Gish G, Shoelson SE, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wyatt PJ. Submicrometer particle sizing by multiangle light scattering following fractionation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1998;197:9–20. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1997.5215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Konarev PV, Volkov VV, Sokolova AV, Koch MHJ, Svergun DI. PRIMUS: a windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Cryst. 2003;36:1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Semenyuk AV, Svergun D. GNOM—a program package for small-angle scattering data processing. J Appl Cryst. 1991;24:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eyal E, Najmanovich R, McConkey BJ, Edelman M, Sobolev V. Importance of solvent accessibility and contact surfaces in modeling side-chain conformations in proteins. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:712–724. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]