Abstract

Conventional models of ligand–receptor regulation predict that agonists enhance the tone of signals generated by the receptor in the absence of ligand. Contrary to this paradigm, stimulation of the type 2 (AT2) receptor by angiotensin II (Ang II) is not required for induction of apoptosis but the level of receptor protein expression is critical. We compared Ang II-dependent and -independent AT2 receptor signals involved in regulating apoptosis of cultured fibroblasts, epithelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells. We found that induction of apoptosis—blocked by pharmacological inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and caspase 3—is a constitutive function of the AT2 receptor. Biochemical and genetic studies suggest that the level of AT2 receptor expression is critical for physiological ontogenesis and its expression is restricted postnatally, coinciding with cessation of developmental apoptosis. Re-expression of the AT2 receptor in remodeling tissues in the adult is linked to control of tissue growth and regeneration. Therefore, we propose that overexpression of the AT2 receptor itself is a signal for apoptosis that does not require the renin–angiotensin system hormone Ang II.

Keywords: angiotensin II/apoptosis/AT2 receptor/p38/vascular smooth muscle cells

Introduction

Hormonal regulation of in vivo functions of the type 2 receptor (AT2) for the octapeptide angiotensin II [Ang II (Asp1-Arg2-Val3-Tyr4-Ile5-His6-Pro7-Phe8-COO–)] is an enigma. Ang II is an important mediator of the renin–angiotensin system’s functions. Almost all of the classical physiological effects attributed to Ang II regulation are mediated by the Ang II type 1 (AT1) receptor, leaving an unexplained role for the AT2 receptor in the renin–angiotensin system. Ang II is widely regarded as the physiological ligand for the AT2 receptor, although Ang II binding does not elicit the usual second-messenger responses or desensitization and down-regulation of the AT2 receptor, the biochemical responses considered hallmarks of ligand regulation of receptor functions (Bottari et al., 1991; Brechler et al., 1993; Hein et al., 1995, 1997; Ichiki et al., 1995; Matsubara, 1998; Horiuchi et al., 1999). Expression of the AT2 receptor is developmentally regulated; genetic defects in it are linked to attenuated apoptosis of mesenchymal cells, contributing to aberrant ontogenesis of the kidney and urinary tract (Nishimura et al., 1999). Apoptosis in cultured pheochromocytoma and fibroblast cell lines is accompanied by overexpression of the AT2 receptor (Yamada et al., 1996; Matsubara, 1998; Nishimura et al., 1999). AT2 receptor gene knockout leads to defective navigational control in mice (Hein et al., 1995; Ichiki et al., 1995). Transgenic cardiac overexpression leads to malfunctioning pacemaker cells and abnormal blood pressure regulation (Masaki et al., 1998). Besides contributing to apoptosis through signals, the AT2 receptor is reported to regulate activities of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), inward rectifier potassium channel, T-type calcium channel, protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 and protein phosphatase 2B (for a review see Matsubara, 1998).

The AT2 receptor is a seven transmembrane (7TM) helical receptor that binds subtype selective ligand PD123319 and CGP42112 (Brechler et al., 1993). It is an atypical receptor with regard to agonist recognition, GTP analogue-dependent agonist affinity modulation, G-protein coupling, and the ability to activate second-messenger pathways (Bottari et al., 1991; Pucell et al., 1991; Brechler et al., 1993; Nakajima et al., 1995; Miura and Karnik, 1999). Although the AT2 receptor contains consensus sites for phosphorylation, it is not phosphorylated in response to Ang II and does not internalize (Hein et al., 1997). Abundant expression of the AT2 receptor in fetal tissues is essential for physiological ontogenesis. Its expression in adults is limited to few tissues, but re-expressed ∼5- to 25-fold over basal during remodeling of tissues where the AT2 receptor is thought to play a role in the apoptosis of smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts and endothelial cells (Bottari et al., 1991; Pucell et al., 1991; Stoll et al., 1995; Dimmeler et al., 1997; Matsubara, 1998; Horiuchi et al., 1999). Thus, the importance of AT2 receptor functions is beginning to be documented, but there is still no explanation of how Ang II regulates the receptor’s functions.

In an earlier study (Miura and Karnik, 1999) we elucidated that the chemical groups on Ang II essential for high affinity binding to the AT2 receptor each contributed only a small proportion (<10%) of the overall binding energy. It is generally believed that the high affinity of hormones is a consequence of their selective binding to receptors that are already active, so that the hormone shifts the equilibrium in favor of active receptors. Alternatively, hormones could bind to inactive receptors and facilitate isomerization to the active state and stabilize the active receptor (Gether and Kobilka, 1998; Karnik, 2000). In either mechanism, agonist analogs, differing in the ability to influence activation, also display large differences in affinity. The lack of affinity discrimination of Ang II analogs (Miura and Karnik, 1999) suggested to us that either the native AT2 receptor is already in an active state or Ang II is not a classical agonist for the AT2 receptor. The current study explores the specificity of the Ang II–AT2 receptor complex in the regulation of signals that contribute to apoptosis. Our results suggest that the AT2 receptor, without Ang II stimulation, generates signals that are critical for the cell death program. Also, consistent with Ang II-independent regulation, the AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis of R3T3 fibroblasts, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) epithelial cells and the A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) is not further enhanced by Ang II.

Results and discussion

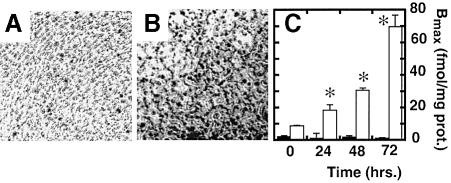

Apoptosis in R3T3 fibroblasts may not require Ang II

Whether Ang II is essential in vivo for the AT2 receptor to mediate apoptosis during embryonic development or physiological and pathological remodeling is unclear. The R3T3 fibroblast cell line has been used as a model for study since apoptosis in these cells resembles the in vivo situation described in ovarian granulosa cells and other remodeling tissues (Pucell et al., 1991; Stoll et al., 1995; Yamada et al., 1996; Matsubara, 1998; Speth et al., 1999). AT2 receptor overexpression precedes apoptosis in confluent R3T3 cells, which express low levels of AT1 and AT2 receptors (2 ± 0.4 versus 9 ± 0.3 fmol/mg protein) when grown in serum. Serum starvation leads to an ∼10-fold increase in AT2 receptor density in the confluent state (see Figure 1). However, in non-confluent R3T3 cells, serum depletion itself was sufficient to induce apoptosis, which was not accompanied by an increase in AT2 receptor density. However, addition of Ang II was not required for induction of apoptosis and the apoptosis could not be blocked by the AT2 receptor-selective antagonist PD123319 (not shown). Thus, the up-regulation of AT2 receptor gene expression might be a signal for apoptosis in vivo. These results are qualitatively similar to those reported in several cultured cell models that lead to the conclusion that Ang II is required to induce apoptosis via the AT2 receptor. Since our finding differs significantly with regard to the specificity of apoptosis induction by the Ang II–AT2 receptor complex, we conclude that it is difficult to separate the critical effects of culture conditions and AT2 receptor overexpression on induction of apoptosis. Hence, the AT2 receptor-expressing native cell lines are not a suitable model to conclude the requirement of an Ang II–AT2 receptor complex for apoptosis and are even less appropriate to conclude a role for induced overexpression of AT2 receptor protein. Cell models where levels of AT2 receptor expression can be controlled are better suited for these studies.

Fig. 1. Apoptosis in R3T3 cells in the presence of 10% serum (A) and under serum-free conditions (B) without Ang II, shown by the TUNEL method. Nuclear stain (see speckled stain pattern) indicates apoptotic cells. The expression levels of AT1 (black bars) and AT2 receptors (white bars) under serum-free conditions for 72 versus 0 h (n = 3, *p <0.05) was measured by saturation binding of 125I-[Sar1,Ile8]Ang II (C).

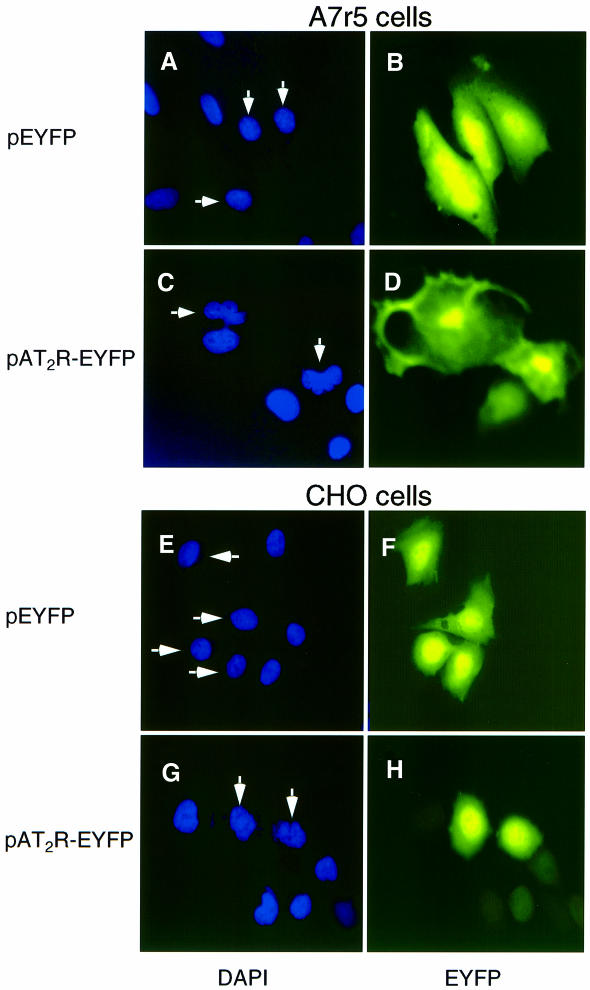

AT2 receptor expression induces apoptosis in CHO cells and VSMCs

To link de novo expression of AT2 receptor to apoptosis, we used the CHO and A7r5 cells as surrogate models (Figure 2). CHO cells are an established epithelial lineage of non-transformed cells that are capable of growing under low-serum conditions with appropriate supplements (Kao and Puck, 1968). A7r5 is an established cell line that retains several smooth muscle characteristics (Kimes and Brandt, 1976). VSMCs, a key component of the blood vessels, is a relevant cell model because it is subjected to apoptotic and mitogenic stimulation, respectively, by AT2 and AT1 receptors in vivo (Kimes and Brandt, 1976; Stouffer and Owens, 1992; Duff et al., 1995; Horiuchi et al., 1999). Expression of the endogenous AT2 receptor is undetectable by 125I-[Sar1-Ile8]Ang II binding and RT–PCR using AT2 receptor mRNA-specific primers, under conditions of both serum-stimulated growth and serum deprivation in both these cell lines. The endogenous AT1 receptor (<18 ± 6 fmol/mg protein) does not elicit any significant inositol phosphate production and MAPK phosphorylation. However, transfection of AT1 receptor cDNA elicited both these responses, indicating that the signal transduction components are present in both cell lines. RT–PCR analysis indicated that these cells do not express angiotensinogen, a key source of intracellular Ang II production and paracrine/autocrine regulation (data not shown). Therefore, by introducing the AT2 receptor in these cells, its effects on apoptosis can be studied without the hypertrophic or mitogenic signaling from the AT1 receptor and/or autocrine influence of Ang II.

Fig. 2. Chromatin condensation and DNA strand break in A7r5 cells (A–D) and CHO cells (E–H) transiently transfected with the AT2 receptor expression vector. Cells transfected with pEYFP (A, B, E and F) or pAT2R-EYFP (C, D, G and H) were stained with DAPI to visualize nuclear morphology (shown in A, C, E and G). The arrows indicate nuclei of EYFP-positive cells without nuclear condensation (A and E) and with nuclear fragmentation (C and G).

Exogenous overexpression of the AT2 receptor induced apoptosis in both CHO and A7r5 cells. Nuclear DNA condensation and fragmentation began ∼24 h (time at which growth arrest is established) after shifting to the low-serum growth condition and was complete after 72 h (Figure 2). Specifically in the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)-positive cells transfected with pAT2R-EYFP, morphological features associated with the apoptotic cells, such as irregular shaped nuclei in conjunction with chromatin condensation, appeared (Figure 2C and G). These cells also exhibited membrane blebbing, cytoplasmic shrinkage and inhibition of protein synthesis (data not shown). In contrast, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining of the pEYFP-transfected control cell nuclei showed sharp round edges and diffuse chromatin (Figure 2A and E). These cells did not exhibit apoptotic features, indicating that the observed apoptosis is specific for the AT2 receptor and is not an artifact of transfection, serum deprivation or EYFP expression.

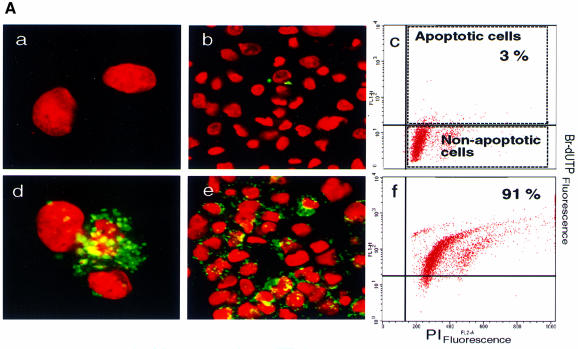

The APO-BRDU™ chromatin DNA fragmentation method was used to quantitate the percentage of cells in apoptosis, employing fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (Figures 3 and 4; see Materials and methods for details). Fluorescein-labeled DNA break points (green) shown in Figure 3A illustrate nuclei in apoptosis in an AT2 receptor-transfected A7r5 culture. Figure 3Ad and 3Ae shows early phase apoptotic nuclei that are characterized by preservation of the nuclear envelope (propidium iodide stained, red). The vector-transfected control cells were mostly not stained with fluorescein (Figure 3Aa and 3Ab). APO-BRDU staining of CHO cells yielded similar results (not shown).

Fig. 3. (A) TUNEL analysis of A7r5 cell nuclei visualized by propidium iodide staining in cells transfected with pcDNA3 (a–c) and pcDNA3-AT2R (d–f). Cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide (red), then Br-dUTP labeled with terminal deoxynucleotide transferase and then stained with the fluorescein-R-1 antibody (green). Cells were imaged on a confocal microscope. Flow cytometric distribution of cells in apoptosis in each condition is shown in c and f. The upper right quadrant in each plot represents TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells (see legend to Figure 4 for details). (B) Influence of various culture conditions on apoptosis in mock, wild-type (WT) or mutant (N127G) AT2 receptor-transfected A7r5 and CHO cells. Effect measured by FACS analysis upon treatment with 0.2% fetal bovine serum (Sf), 10% fetal bovine serum (Se), 0.1 µM agonist [Sar1]Ang II and 10 µM non-peptide antagonist PD123319; n = 3, *p <0.05 versus mock, †p <0.05 versus serum condition.

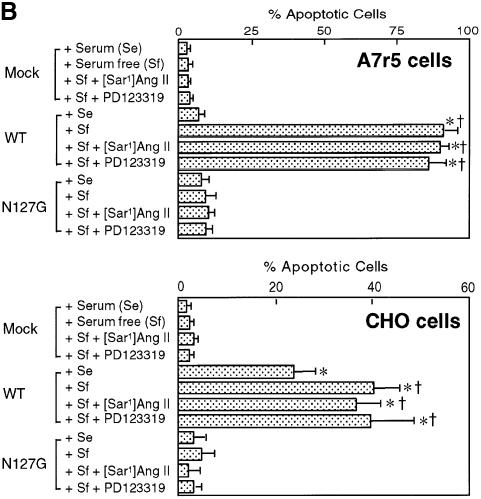

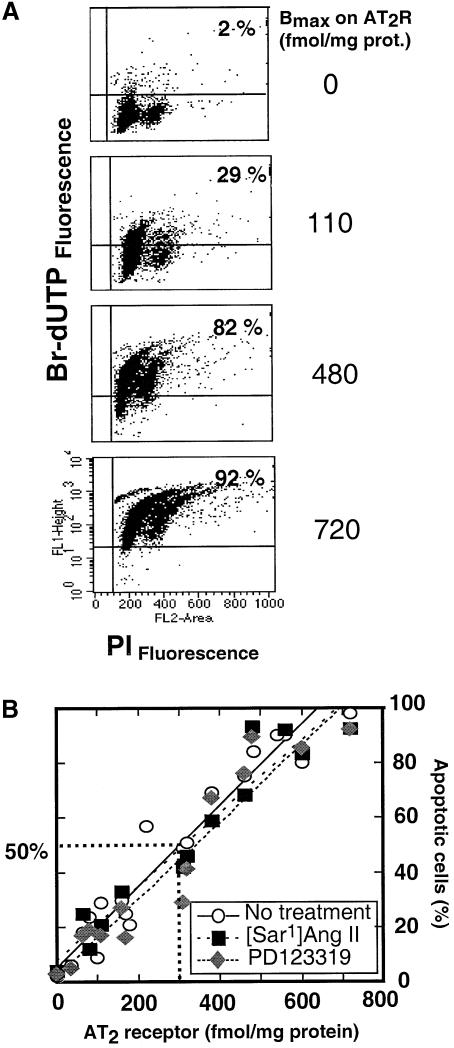

Fig. 4. (A) Quantitation of the AT2 receptor’s influence on A7r5 cell apoptosis. The percentage of cells in apoptosis in the samples shown was 2% in 12 µg (per 106 cells) pcDNA3 empty vector DNA-transfected control, 29% in a 1:1 mixture of pcDNA3 (6 µg) + pcDNA3-AT2 receptor (6 µg) and 92% in 12 µg pcDNA3-AT2 receptor expression vector-transfected sample. Transfected cells (1 × 106) were TUNEL stained and counterstained with propidium iodide (see Materials and methods for details). FACscan shows the distribution of cells within different cell cycle stages indicated on top. The upper right quadrant in each plot represents TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells. In each instance, 10 000 propidium iodide-stained cells were monitored and the percentage of apoptotic cells per dish was calculated. (B) Correlation between the expressed AT2 receptor number and the percentage of apoptotic A7r5 cells. Regression lines from independent transfection experiments are shown, y = 5.3 + 0.15x, n = 19, r = 0.97, p <0.05 (no treatment); y = 8.0 + 0.13x, n = 10, r = 0.94, p <0.05 (0.1 µM [Sar1]Ang II); y = 2.9 + 0.14x, n = 14, r = 0.96, p <0.05 (10 µM PD123319). The expression levels of the AT2 receptor (Bmax) were calculated from Scatchard plot analysis of 125I-[Sar1-Ile8]Ang II binding (represented as Bmax) measured in parallel.

The percentage of A7r5 cells in apoptosis determined by FACS was 3% in the pcDNA3 empty vector-transfected (12 µg/106 cells) control sample (Figure 3Ac)and 91% in the pcDNA3-AT2R expression vector-transfected (12 µg/106 cells) sample (Figure 3Af). The presence of 10% bovine calf serum completely suppressed apoptosis in A7r5 cells (Figure 3B). The maximum AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis observed in CHO cells was ∼40% under serum starvation. In the presence of serum, a significant fraction of AT2 receptor-transfected CHO cells (∼20%) still exhibited apoptosis. The reasons for differing effects of serum on AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis in different cells lines are not known at present. Serum starvation by itself did not induce apoptosis, nor did the treatments with the agonist [Sar1]Ang II and the antagonist PD123319 in vector-transfected A7r5 and CHO cells (Figure 3B). Rather unexpectedly, [Sar1]Ang II and PD123319 also did not modulate apoptosis in pcDNA3-AT2R-transfected cells.

To evaluate the ability of the AT2 receptor protein to induce apoptosis directly, we expressed different levels of the receptor in A7r5 cells and measured the percentage of cells in apoptosis by FACS analysis (Figure 4A). Transfecting variable mixtures of the expression vector with and without the AT2 receptor cDNA insert (see Materials and methods for details) led to variable levels of expression of the AT2 receptor that were directly correlated with the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis (r = 0.97; y = 4.8 + 0.15x; n = 19). An average of 50% cells are in apoptosis when the AT2 receptor level is 300 fmol/mg protein (Figure 4B). The expression level of AT2 receptor in normal adult tissues is ∼10–20 fmol/mg protein. The expression level is ∼260 fmol/mg protein in 18-day fetal tissue (Viswanathan et al., 1991), ∼453 fmol/mg protein in the atretic ovarian follicular membrane (Speth et al., 1999) and ∼345 fmol/mg protein in confluent mesangial cells (Goto et al., 1997). In most model systems a significant increase in AT2 receptor mRNA, but not the exact receptor numbers, is reported. Therefore, the expression level of ∼300 fmol/mg protein was used for pharmacological studies (see later).

A specific conformation of the AT2 receptor is necessary for induction of apoptosis

Overexpression of AT2 receptors on the cell surface could abrogate cell–matrix interaction or the cell’s access to essential sustenance for growth. To determine whether the overexpression of the protein or the specific function of the native receptor is responsible for the apoptosis induced by the AT2 receptor, we transfected the N127G mutant (Figure 3B). This mutation decreases the affinity of the antagonist PD123319 80-fold. The affinity of the agonist [Sar1]Ang II and various agonist analogs is also decreased 2- to 20-fold, suggesting that the conformation of the mutant receptor is different from that of the wild-type (WT) AT2 receptor. The N127G mutant AT2 receptor was expressed on the plasma membrane in the A7r5 and CHO cells, and the expression level of the mutant was comparable to that of the WT AT2 receptor (Bmax of WT versus N127G is 605 ± 15 versus 540 ± 20 fmol/mg protein in A7r5 cells and 1030 ± 40 versus 1250 ± 50 fmol/mg protein in CHO cells). The maximum apoptosis induced by the N127G mutant was ∼10% of that induced by the WT AT2 receptor in both cell lines. [Sar1]Ang II at 1–10 µM (>100-fold over Kd) did not stimulate apoptosis in both A7r5 and CHO cells transfected with the N127G mutant, indicating that decreased agonist affinity is not the cause of the defect in this mutant. Thus, cell surface expression of the AT2 receptors is not sufficient, rather the observations suggest a specific conformation attained by the WT protein to induce apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner. Apoptosis in the CHO cells correlated with the level of expression of the WT AT2 receptor. Expression of the N127G mutant did not induce apoptosis in CHO cells (Figure 3B). Thus, no unique characteristic feature of smooth muscle cells seems to be critical for AT2 receptor to induce apoptosis.

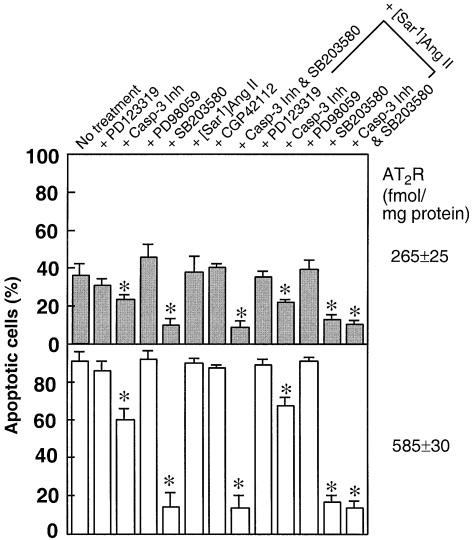

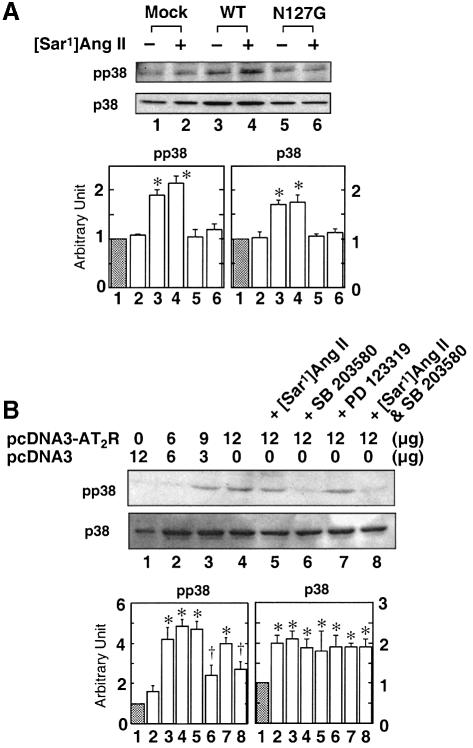

AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis is mediated by p38 MAPK and caspase-3

Mechanisms for the recruitment of distinct members of the MAPK superfamily and caspase family do exist in the AT2 receptor. Pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAPK and caspase-3 blocked apoptosis induced by two different levels of AT2 receptor expression in A7r5 cells (Figures 5–7). The p38 MAPK-specific inhibitor SB203580 blocked AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis by ∼80%. The SB203580 inhibitor alone had no significant effect on A7r5 cells. The maximal inhibitory effect of SB203580 (10 µM) occurred when the inhibitor was present during serum starvation; this inhibitor was not effective when added 24 h after serum starvation, suggesting a small time window for its action. Immunoblot analysis indicated that a protein of ∼44 kDa that cross-reacted with p38 MAPK-specific antiserum is present in A7r5 cells (Figure 6A). VSMCs have also been shown to contain p38 MAPK (Kusuhara et al., 1998). In AT2 receptor-transfected cells, basal levels of both p38 MAPK and phospho-p38 MAPK were elevated. In contrast, cells transfected with empty vector or the N127G mutant contained lower levels of mostly non-phosphorylated p38 MAPK (Figure 6A). Treatment with [Sar1]Ang II did not further increase phospho-p38 MAPK levels but treatment with SB203580 decreased levels in these cells. PD123319 treatment had no effect. None of the treatments affected p38 MAPK levels (Figure 6B). These results suggest a significant functional role for p38 MAPK in AT2 receptor-mediated apoptotic signaling.

Fig. 5. Pharmacological intervention of apoptosis in AT2 receptor-transfected A7r5 cells. Effect measured by FACS analysis upon treatment with 30 µM MEK inhibitor PD98059, 10 µM p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, 1 µM caspase-3 inhibitor DEVD-cmk, 1 µM CGP42112, 10 µM PD123319 and 0.1 µM [Sar1]Ang II; n = 3, *p <0.05 versus no treatment.

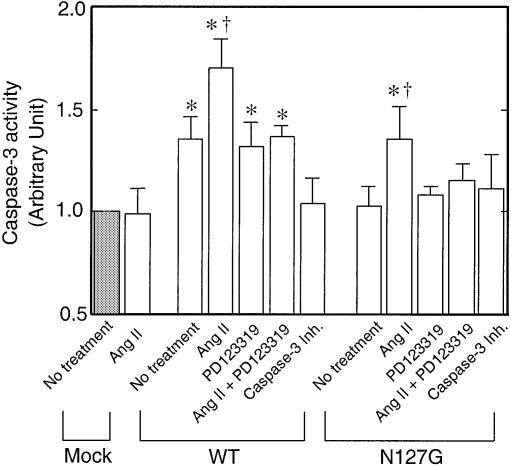

Fig. 7. Caspase-3-like activity was measured in A7r5 cells transfected with pcDNA3 (Mock), pcDNA3-AT2R (WT), pcDNA3-AT2R N127G mutant plasmid. Cells were treated with [Sar1]Ang II (0.1 µM), PD123319 (10 µM) or caspase-3 Inh. (1 µM). The activity of the enzyme in the pcDNA3-transfected cell extract, 1.73 pmol of pNA liberated/µg protein/h at 37°C, was considered as one arbitrary unit. *p <0.05 versus mock, †p <0.05 versus no treatment in each group.

Fig. 6. Immunoblot analysis of the p38 MAPK and phospho-p38 MAPK levels in A7r5 cells transfected with various expression vectors (A) and with various treatments (B) following serum starvation. An equal amount of total protein was loaded in each lane. *p <0.05 versus control shown in lane 1 in each group; †p <0.05 versus AT2 receptor control shown in lane 4 in each group. Results shown are of three experiments normalized; the control was set at 1.0 arbitrary unit.

To characterize the roles of p42/44 MAPK in AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis, we measured the effect of PD98059, a specific inhibitor of MEK, on the AT2 receptor-stimulated apoptosis (Figure 5). PD98059 at 30 µM, a concentration that blocked accumulation of phospho-p42/44 MAPK, alone did not induce apoptosis, nor did it potentiate an apoptotic response to AT2 receptor expression (not shown). MEK activates p42/44 MAPK by phosphorylation and the AT2 receptor-coupled MAPK-phosphatase 1 dephosphorylates p42/44 MAPK (Yamada et al., 1996). Down-regulation of p42/p44 MAPK activity in VSMCs, neuroblastoma cells, cultured primary neurons and rat fibroblasts has been suggested to contribute to the anti-growth effect associated with the AT2 receptor (Duff et al., 1995; Nakajima et al., 1995; Huang et al., 1996; Yamada et al., 1996). However, this regulatory loop does not seem to be critical in the apoptotic pathway, but may have a role in exerting an anti-growth effect. We did not investigate the activation of the c-jun-kinase, because an increase in its activity is slower and specific inhibitors do not yet exist. Furthermore, nearly complete blockade of apoptosis by SB203580 is indicative of an exclusive role of p38 MAPK in AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis.

We examined activation of caspases since the activation of class II caspases, a process essential for the execution of catastrophic proteolysis of regulatory proteins in a cell destined to die, is considered a hallmark of programmed cell death (Ashkenazi and Dixit, 1998). The caspase-3 inhibitor Ac-DEVD-cmk (1 µM) inhibited ∼30% of the AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis (Figure 5). The partial blockade might be because this class of inhibitors are not very potent. The measured caspase-3-like activity in cell-free extracts prepared from WT AT2 receptor-transfected cells was significantly higher than that in pcDNA3-transfected (mock) and N127G mutant-transfected cells (Figure 7). The increase in caspase-3-like activity in the WT AT2 receptor-transfected cells was not suppressed by the antagonist PD123319. The observations that N127G mutant receptor does not induce apoptosis or activate caspase-3-like activity and that the WT receptor activates caspase-3-like activity suggest that this activity is critical for induction of apoptosis. The involvement of other caspases in the process can not be ruled out. Thus, the activation and involvement of the caspase cascade in the AT2 receptor-induced apoptotic process are indicated.

Apoptosis induced by AT2 receptor expression is not enhanced by Ang II nor inhibited by the AT2 receptor antagonist

Several lines of evidence suggest that the activation of programmed cell death may be a constitutive function of the AT2 receptor. In AT2 receptor-transfected CHO and A7r5 cell models, induction of apoptosis was not enhanced by the agonist [Sar1]Ang II and was not inhibited by the antagonist PD123319 (Figure 3B). A similar mechanism may be involved in apoptosis in R3T3 fibroblasts as discussed earlier. Since Ang II dependence of apoptosis induction by the AT2 receptor has been indicated in several studies earlier, we systematically examined the influence of [Sar1]Ang II and PD123319 at several different levels of expression in A7r5 cells (Figure 4B). Measured apoptosis was neither enhanced by [Sar1]Ang II nor inhibited by PD123319. Treatment of cells with 0.1–10 µM [Sar1]Ang II did not increase the apoptotic index (calculated from the slope). A seeming decrease in the apoptotic index at receptor densities ≤300 fmol/mg, by treatment with the AT2 receptor antagonist PD123319, was not statistically significant, indicating a lack of inhibition by the compound. The drug had no effect on apoptosis at receptor densities ≥300 fmol/mg. In another experiment, we varied the AT2 receptor number from 10 to 720 fmol/mg protein, with and without [Sar1]Ang II or PD123319, to measure the time of onset of apoptosis. The differences among the three conditions were small and not significant. In the CHO cells, treatment with 0.1–10 µM [Sar1]Ang II did not increase the percentage of apoptosis and also had no influence on the apoptosis index (not shown).

To examine Ang II independence of various AT2 receptor signals that contribute to apoptosis, we evaluated the potency of various pharmacological inhibitors on apoptosis with and without [Sar1]Ang II treatment (Figure 5). These experiments were carried out at two different levels of AT2 receptor expression, 265 ± 25 and 585 ± 30 fmol/mg protein, as shown in Figure 5. Combined treatment with [Sar1]Ang II + PD98059 did not have a synergistic effect on apoptosis, as would be anticipated, at both levels of expression (Figure 5). Furthermore, [Sar1]Ang II treatment did not antagonize the inhibition of apoptosis by SB203580, and the caspase-3 inhibitor DEVD-cmk. The most unexpected observation from these studies is the lack of an apoptosis-activating effect by [Sar1]Ang II. These findings are comparable to the observations reported in earlier studies that indicate that Ang II does not induce the cascade of events that are hallmarks of receptor regulation by agonists. For instance, Pucell et al. (1991) and Hein et al. (1997) reported that Ang II does not stimulate endocytosis of the AT2 receptor, implying that signals responsible for endocytosis are not generated. Similarly, AT2 receptor–Gi immune complex is insensitive to dissociation by GTPγS, unlike what would be expected (Zhang and Pratt, 1996).

Blockade of AT2 receptor-induced apoptosis by SB203580 suggests that members of the p38 MAPK family are recruited for mediating this process (Figure 5). Accumulation of phospho-p38 MAPK in AT2-transfected cells is blocked by SB203580 but not affected by the agonist [Sar1]Ang II and the antagonist PD123319 (Figure 6). This observation indicates that the p38 MAPK activation is linked to the level of expression of AT2 receptor protein and not to activation of the AT2 receptor by the ligand. The SB series inhibitors are proposed to be specific inhibitors of α and β isoforms of p38 MAPK. In some cell types (such as Jurkat lymphoma and HeLa cells), p38β is involved in attenuation of apoptosis and p38α in augmentation of apoptosis (Wang et al., 1998). Assuming a similar mode of action in AT2 receptor-transfected A7r5 and CHO cells, inhibition of p38α may shift the balance in favor of anti-apoptotic effects. Ectopic expression of p38 MAPK is known to induce cell death in PC12 cells (Wang et al., 1998). Activated p38 MAPK is capable of phosphorylating the activating transcription factor-2 (Eliopoulos et al., 1999), which disregulates the cell cycle progression (Xia et al., 1995; Lavoie et al., 1996).

AT2 receptor expression-linked apoptosis is partially blocked by caspase-3 inhibitor but the inhibition is not altered by ligands of the AT2 receptor (Figure 5). However, [Sar1]Ang II caused a significant increase in caspase-3-like activity in both WT and N127G mutant receptor-transfected cells (Figure 7). This fraction of caspase-3-like activity could be suppressed by PD123319 + [Sar1]Ang II treatment in both instances. Since PD123319 alone could not suppress caspase-3 activation by the WT AT2 receptor and [Sar1]Ang II treatment did not enable the N127G mutant to activate apoptosis, these observations together suggest that [Sar1]Ang II-induced caspase-3-like activity is not only not sufficient for inducing apoptosis in the N127G mutant but may also not be critical for apoptosis through the WT receptor. In contrast, caspase-3 activation by overexpression of the WT receptor is critical for apoptosis. The activation of caspase-3 is thought to be important for specific cleavage of the cell cycle regulatory proteins p21waf1 and p27kip1 in apoptotic cells (Levkau et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1998).

Induction of apoptosis by the AT2 receptor through constitutive signal transduction

In several cell culture models, recent studies have demonstrated that Ang II is capable of inducing anti-growth and apoptosis effects via the AT2 receptors, which are not overexpressed. This anti-growth signaling is mediated by down-regulation of p42/p44 MAPK and apoptosis is considered to be an extreme form of anti-growth signaling. While apoptosis in coronary endothelial cells is proposed to be Ang II/AT2 receptor mediated (Stoll et al., 1995), in human umbilical endothelial cells it has been shown that the process is Ang II dependent but is not exclusively mediated by the AT2 receptor, and depends on complex interplay between AT1 and AT2 receptors (Dimmler et al., 1997). In cardiomyocytes, an entirely distinct mechanism for Ang II-induced apoptosis via the AT1 receptor has been described (Kajstura et al., 1997). Thus, Ang II-induced apoptosis in different cell types presents a complex picture.

Overexpression of AT2 receptor generates signals that are distinct and may be important in vivo. In ovarian atretic follicles, granulosa cells that express high levels of AT2 receptor also exhibit marked apoptosis mediating follicular atresia. Up-regulation of AT2 receptor at sites of vascular injury, myocardial infarction, healing skin wound and remodeling uterine endometrium suggests that AT2 receptor plays an important role in the pathophysiology of these remodeling processes. High levels of AT2 receptor are expressed in adrenal medulla in the adult mammals where the role of AT2-induced apoptosis is not clear. High levels of AT2 receptor expression are essential in the developing fetus where its primary role is to regulate apoptosis in ontogenic tissue. However, existing evidence is insufficient to conclude that Ang II stimulation of AT2 receptor is a prerequisite for in vivo apoptosis in the remodeling process. Although the sequence of molecular events underlying the induction of AT2 receptor overexpression in vivo is different from the experimental system here, our experiments suggest that the overexpressed AT2 receptor was the source of the death signal that could be turned off only by mutation of the receptor and pharmacological interception of the signal flow (i.e. p38 MAPK inhibition, caspase-3 inhibition).

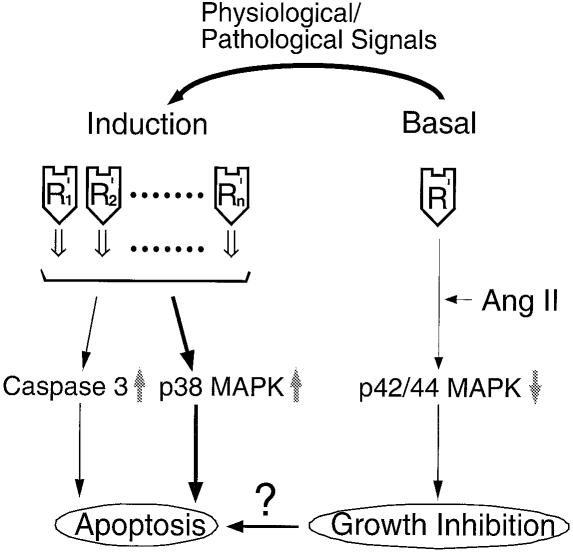

To reconcile the observations presented here with those reported earlier, we propose the model depicted in Figure 8. We propose that overexpressed AT2 receptors enhance a low tone signal that promotes the cells to enter programmed cell death. The activities of p38 MAPK and caspase-3 are integral components of this signal. A unique conformation of the WT receptor that is not significantly affected by the binding of Ang II and PD123319 is essential. The apoptosis observed upon overexpression of the AT2 receptor is merely a result of the increase in number of receptors, not the proportion of active and inactive receptor states, which is normally regulated by agonists and inverse agonists (Gether and Kobilka, 1998; Karnik, 2000). Our model assumes that the receptor exists in a finite number of states, each of which could play a distinct role in the growth control of cells. It has recently been proposed that multiple-state models are better suited to the accurate depiction of the behavior of 7TM receptors (Chidiac, 1995).

Fig. 8. A model of Ang II-dependent and constitutive signaling by the AT2 receptor.

Although the results presented (Figure 4) suggest that the pro-apoptotic activity is a property of the entire population of AT2 receptors, these experiments do not rule out the possibility that receptors attain a ‘different active state’ conformation that uniquely triggers this process. Then why does Ang II not affect the apoptosis linked to this state by altering the equilibrium between various states? The observation needs further study, but the unique binding profile of Ang II analogs, which suggests that Ang II may function more like a neutral ligand, is an important consideration (Miura and Karnik, 1999). In other receptors, neutral ligands do not disturb the equilibrium between different functional states of the receptor and may exhibit relatively uncommon zero efficacy. The behavior of PD123319 suggests that it functions as a competitive antagonist, not an inverse agonist (Gether and Kobilka, 1998). Therefore, it is evident that modulation of the AT2 receptor level plays the key role in vivo to switch the cells to apoptosis. Regulation by overexpression of signaling molecules is a relatively common paradigm, but the observation that additional hormone-independent signals lead to a distinctly different biological outcome represents a unique mode of regulation. Whether this type of regulation is unique to the AT2 receptor or generally important in ontogenesis and remodeling is an unexplored question. The discovery of orphan G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are developmentally modulated might indicate that hormone-independent regulation by GPCRs may be more general than currently appreciated.

Regulation by increased tone of a ligand-independent signal through the overexpression of the receptor is not a well understood process and is irreconcilable with the prevailing concept of a two-state model for activation of a 7TM receptor: hormone binding (Ang II) activates the intracellular response and antagonist (PD123319) binding is able to block the signal. This type of signaling by the AT2 receptor has been reported to induce an ‘anti-growth state’ in many cell types and apoptosis (Pucell et al., 1991; Nakajima et al., 1995; Stoll et al., 1995; Yamada et al., 1996; Dimmeler et al., 1997; Matsubara, 1998; Horiuchi et al., 1999; Nishimura et al., 1999). These studies also suggest that a mechanism that is not directly explained by the two-state model governs induction of apoptosis by the AT2 receptor. Some of these questions have been alluded to above. Our experiments do not exclude agonist-dependent signaling by the AT2 receptor. Ang II-mediated inhibition of the p42/p44 MAPK by the AT2 receptor is consistent with this model but raises several unanswered questions. For example, we do not yet know the key differences between anti-growth and the apoptotic signal transduction process. We suspect that coupling to specific members of the MAPK superfamily may be critical for different modes of AT2 receptor function. We hope that experiments and the model described here will open a new window into the AT2 receptor-coupled apoptotic process and facilitate additional studies into these questions.

In summary, high-level expression of the AT2 receptor as part of the fetal genetic program has been broadly implicated in ontogenesis, remodeling of adult tissues, development and differentiation. Transfected AT2 receptor activates p38 MAPK-mediated apoptotic signaling and activation of cell death-promoting proteases. On the basis of the results presented here, we propose that induction of apoptosis is an intrinsic property of the native AT2 receptor, limited by a threshold number of molecules per cell. One of the functions of the AT2 receptor is to ensure abrupt switching to the apoptosis program, and our study suggests that Ang II activation is not essential for this function. The findings in this study have important implications for the predicted functions of AT2 receptors in vivo. Inductive control of AT2 receptor expression in vivo is likely to be a contributory factor to tissue remodeling. We predict that the constitutive pro-apoptotic activity of the AT2 receptor is the reason why AT2 receptor expression is placed under inducible control. The observations presented here suggest that in vivo apoptosis induced by re-expression of the AT2 receptor is likely to be a regulatory mechanism that is independent of the renin–angiotensin system.

Materials and methods

Materials

The following antibodies and reagents were generously provided as indicated or purchased: AT2 receptor-selective non-peptide antagonist PD123319 (Research Biochemical International), a specific inhibitor of the MEK kinase, PD98059, 2-(2′-amino-3′-methoxyphenyl)oxanaphthalen-4-one (Biomol); the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580, 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfonylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole (Upstate Bio); the caspase-3 inhibitor, Ac-DEVD-chloro methyl ketone (Calbiochem); anti-phospho p38 MAPK antibody #9211S and anti-p38 MAPK antibody #9102 (New England Biolabs). 125I-[Sar1,Ile8]Ang II was purchased from Dr Robert Speth, Washington State University.

Cell cultures and treatments

The mouse fibroblast line, R3T3 cells (Dudley et al., 1991), CHO-K1 cells (ATCC CCL-61) (Kao and Puck, 1968) and the embryonic rat thoracic aorta-derived VSMC line, A7r5 cells (ATCC CRL-1444) (Kimes and Brandt, 1976) were cultured using penicillin- and streptomycin-supplemented Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s essential medium (DMEM) (Gibco-BRL) with 10% bovine calf serum (HyClone) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Apoptosis was measured in cells maintained for 48 h in DMEM containing 0.2% fetal calf serum. Cell viability was >95% by trypan blue exclusion analysis in control experiments. The level of AT2 receptor stimulation was measured in the presence of 0.1 µM [Sar1]Ang II (Kd = 0.3 nM), and inhibition in the presence of 10 µM AT2 selective non-peptide antagonist PD123319 (Kd = 5 nM). [Sar1]Ang II was added every 12 h to compensate for potential degradation. Inhibition experiments were performed in the presence of the p42/p44 MAPK-specific inhibitor PD98059 (30 µM), the p38 MAPK-specific inhibitor SB203580 (10 µM) and the caspase-3 inhibitor (1 µM) for 48 h after transfection.

VSMCs and CHO cell transfection

The expression vector pcDNA3-AT2R contains rat AT2 receptor cDNA (Invitrogen). In mock transfection control samples, the pcDNA3 empty vector (without the AT2 receptor cDNA insert) was used. To vary the expression levels of the AT2 receptor without compromising the transfection efficiency (>80%), the plasmid DNA concentration was maintained constant (12 µg/plate), but the ratio of pcDNA3:pcDNA-AT2R was varied (see legend to Figure 5). The pAT2R-EYFP expression vector was constructed by fusion of the coding sequence of EYFP (Clontech) to the 3′ end of the AT2 receptor coding sequence. Cells were transfected using DOSPER [1,3-di-oleoyloxy-2-(6-carboxyspermyl)-propylamid] liposomal reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer Mannheim). The efficiency of transfection in each experiment was estimated in parallel from transfection of 12 µg/plate p-EYFP. Cells were harvested and flow cytometric analysis was conducted by using FACS (Becton Dickinson).

Immunoblotting

For each time point or manipulation, protein extracts were prepared from a 100 mm plate. After the cells were washed, lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5% NP-40) was added, scraped, transferred to a microcentrifuge tube, and boiled for 5 min. The viscosity of the sample was reduced using a Microson® ultrasonic cell disrupter, followed by centrifugation for 5 min. Total protein content in the supernatant was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce). An equal amount of protein (10–30 µg) per well was loaded onto 10% SDS–PAGE gels. Western blot analysis was performed with primary antibodies as specified in each case. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and the enhanced chemiluminescent substrate system (Amersham) were used as a detection system. The signal was independently quantified by a digital image analysis system (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY).

Analysis of apoptosis

R3T3 cells. Apoptotic cells were determined by the in situ Cell Death Detection Kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Boehringer Mannheim). Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate nicked end labeling (TUNEL) reaction mix was added. Anti-BrdU antibody Fab fragment conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and the metal-enhanced substrate 3,3′-diaminobenzidine were added next. Cells were analyzed by light microscopy.

VSMCs and CHO cells. Apoptotic cells were determined by TUNEL flow cytometry using the APO-BRDUTM kit (Phoenix Flow Systems, Inc.). Briefly, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and washed and then labeled with Br-dUTP using the terminal deoxynucleotide transferase enzyme. Cells were stained with the fluorescein–PRB-1 antibody. Propidium iodide/RNase solution was added to remove RNA and label nuclear DNA. Cells were analyzed by flow cytomety using Vantage [Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA (a gift from the Keck foundation)]. The same samples were imaged using a Leica TCS-SP laser scanning confocal microscope. For imaging, the cells were plated on lysine-coated microscope slides and after transfection the cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 15 min. The slides were then stained with DAPI for detection of chromatin condensation. The cells were imaged using a Leika DMIRB digital fluorescent microscope.

Caspase-3-like activity assay

Caspase-3-like protease activity was determined by colorimetric assay using the CaspACETM assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected and control cells (106) were lysed in the lysis buffer by freezing and thawing, followed by centrifugation (15 000 g for 20 min at 4°C). Caspase-3-like activity was measured in supernatants by following the proteolytic cleavage of the colorimetric substrate Ac-DEVD-pNA. DEVD-pNA was used as standard in assay buffer (λmax 405 nm).

Receptor binding assay

The ligand binding experiments were carried out as described earlier (Noda et al., 1996; Miura and Karnik, 1999). Kd and Bmax of the receptor were estimated by 125I-[Sar1,Ile8]Ang II equilibrium binding and Scatchard plot analysis.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of three or more independent determinations. Significant differences in measured values were evaluated with an analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s test and unpaired Student’s t-test. Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were calculated. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Jingli Zhang and John Boros for excellent technical assistance, Amy Raber at the FACS core facility for assistance in cell sorting, and Judith Drazba for assistance in fluorescence microscopy. Suggestions and criticism of the work by Ramaswamy Ramchandran and Chang-sheng Chang are gratefully acknowledged. We thank Robin Lewis and Christine Kassuba for assistance in manuscript preparation. We gratefully acknowledge the Radio-iodination Center of the Washington State University for supplying 125I-[Sar1,Ile8]Ang II. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL5648 and the American Heart Association Established Investigator Award to S.K.

References

- Ashkenazi A. and Dixit,V.M. (1998) Death receptors: Signaling and modulation. Science, 281, 1305–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottari S.P., Taylor,V., King,I.N., Bogdal,Y., Whitebread,S. and deGasparo,M. (1991) Angiotensin II AT2 receptors do not interact with guanine nucleotide binding proteins. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 207, 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechler V., Jones,P.W., Levens,N.R., deGasparo,M. and Bottari,S.P. (1993) Agonistic and antagonistic properties of angiotensin analogs at the AT2 receptor in PC12W cells. Regul. Pept., 44, 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidiac P. (1995) Receptor state and ligand efficacy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci., 16, 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S., Rippmann,V., Weiland,U., Haendeler,J. and Zeiher,A.M. (1997) Angiotensin II induces apoptosis of human endothelial cells. Protective effect of nitric oxide. Circ. Res., 81, 970–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley D.T., Hubbell,S.E. and Summerfelt,R.M. (1991) Characterization of angiotensin II (AT2) binding sites in R3T3 cells. Mol. Pharmacol., 40, 360–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff J.L., Marrero,M.B., Paxton,W.G., Schieffer,B., Bernstein,K.E. and Berk,B.C. (1995) Angiotensin II signal transduction and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Cardiovasc. Res., 30, 511–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliopoulos A.G., Gallagher,N.J., Blake,S.M., Dawson,C.W. and Young,L.S. (1999) Activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by Epstein–Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 co-regulates interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 production. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 16085–16096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gether U. and Kobilka,B.K. (1998) G protein-coupled receptors. II. Mechanism of agonist activation. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 17979–17982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M. et al. (1997) Growth-dependent induction of angiotensin II type 2 receptor in rat mesangial cells. Hypertension, 30, 358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein L., Barsh,G.S., Pratt,R.E., Dzau,V.J. and Kobilka,B.K. (1995) Behavioral and cardiovascular effects of disrupting the angiotensin II type-2 receptor in mice. Nature, 377, 744–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein L., Meinel,L., Pratt,R.E., Dzau,V.J. and Kobilka,B.K. (1997) Intracellular trafficking of angiotensin II and its AT1 and AT2 receptors: evidence for selective sorting of receptor and ligand. Mol. Endocrinol., 11, 1266–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi M., Akishita,M. and Dzau,V.J. (1999) Recent progress in angiotensin II type 2 receptor research in the cardiovascular system. Hypertension, 33, 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.C., Richards,E.M. and Sumners,C. (1996) Mitogen-activated protein kinases in rat brain neuronal cultures are activated by angiotensin II type 1 receptors and inhibited by angiotensin II type 2 receptors. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 15635–15641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiki T. et al. (1995) Effects on blood pressure and exploratory behavior of mice lacking angiotensin II type-2 receptor. Nature, 377, 748–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajstura J., Cigola,E., Malhotra,A., Li,P., Cheng,W., Meggs,L.G. and Anversa,P. (1997) Angiotensin II induces apoptosis of adult ventricular myocytes in vitro. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol., 29, 859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao F.T. and Puck,T.T. (1968) Genetics of somatic mammalian cells, VII. Induction and isolation of nutritional mutants in Chinese hamster cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 60, 1275–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnik S.S. (2000) Conformational theories on receptor activation from studies of the AT1 receptor. In Husain,A. and Graham,R.M. (eds), Drugs, Enzymes and Receptors of the Renin–angiotensin System: Celebrating a Century of Discovery. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kimes B.W. and Brandt,B.L. (1976) Characterization of two putative smooth muscle cell lines from rat thoracic aorta. Exp. Cell Res., 98, 349–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuhara M., Takahashi,E., Peterson,T.E., Abe,J., Ishida,M., Han,J., Ulevitch,R. and Berk,B.C. (1998) p38 kinase is a negative regulator of angiotensin II signal transduction in vascular smooth muscle cells: effects on Na+/H+ exchange and ERK1/2. Circ. Res., 83, 824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie J.N., L’Allemain,G., Brunet,A., Muller,R. and Pouyssegur,J. (1996) Cyclin D1 expression is regulated positively by the p42/p44MAPK and negatively by the p38/HOGMAPK pathway. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 20608–20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkau B., Koyama,H., Raines,E.W., Clurman,B.E., Herren,B., Orth,K., Roberts,J.M. and Ross,R. (1998) Cleavage of p21Cip1/Waf1 and p27Kip1 mediates apoptosis in endothelial cells through activation of Cdk2: Role of a caspase cascade. Mol. Cell, 1, 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki H. et al. (1998) Cardiac-specific over expression of angiotensin II AT2 receptor causes attenuated response to AT1 receptor-mediated pressor and chronotropic effects. J. Clin. Invest., 101, 527–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara H. (1998) Pathophysiological role of angiotensin II type 2 receptor in cardiovascular and renal diseases. Circ. Res., 83, 1182–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura S. and Karnik,S.S. (1999) Angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors bind angiotensin II through different types of epitope recognition. J. Hypertens., 17, 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M., Hutchinson,H.G., Fujinaga,M., Hayashida,W., Morishita,R., Zhang,L., Horiuchi,M., Pratt,R.E. and Dzau,V.J. (1995) The angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) receptor antagonizes the growth effects of the AT1 receptor: gain-of-function study using gene transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 10663–10667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura H. et al. (1999) Role of the angiotensin type 2 receptor gene in congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, CAKUT, of mice and men. Mol. Cell, 3, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda K., Feng,Y.H., Liu,X.P., Saad,Y., Husain,A. and Karnik,S.S. (1996) The active state of the AT1 angiotensin receptor is generated by angiotensin II induction. Biochemistry, 35, 16435–16442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucell A.G., Hodges,J.C., Sen,I., Bumpus,F.M. and Husain,A. (1991) Biochemical properties of the ovarian granulosa cell type 2-angiotensin II receptor. Endocrinology, 128, 1947–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speth R.C., Daubert,D.L. and Grove,K.L. (1999) Angiotensin II: a reproductive hormone too? Regul. Pept., 79, 25–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll M., Steckelings,U.M., Paul,M., Bottari,S.P., Metzger,R. and Unger,T. (1995) The angiotensin AT2-receptor mediates inhibition of cell proliferation in coronary endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest., 95, 651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer G.A. and Owens,G.K. (1992) Angiotensin II-induced mitogenesis of spontaneously hypertensive rat-derived cultured smooth muscle cells is dependent on autocrine production of transforming growth factor-β. Circ. Res., 70, 820–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M., Tsutsumi,K., Correa,F.M.A. and Saavedra,J.M. (1991) Changes in expression of angiotensin receptor subtypes in the rat aorta during development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 179, 1361–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Huang,S., Sah,V.P., Ross,J.,Jr, Brown,J.H., Han,J. and Chien,K.R. (1998) Cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy and apoptosis induced by distinct members of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase family. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 2161–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z., Dickens,M., Raingeaud,J., Davis,R.J. and Greenberg,M.E. (1995) Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science, 270, 1326–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Horiuchi,M. and Dzau,V.J. (1996) Angiotensin II type 2 receptor mediates programmed cell death. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 156–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. and Pratt,R.E. (1996) The AT2 receptor selectively associates with Giα2 and Giα3 in the rat fetus. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 15026–15033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]