Abstract

Few mating-regulated genes have been characterized in Candida albicans. C. albicans FIG1 (CaFIG1) is a fungus-specific and mating-induced gene encoding a putative 4-transmembrane domain protein that shares sequence similarities with members of the claudin superfamily. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Fig1 is required for shmoo fusion and is upregulated in response to mating pheromones. Expression of CaFIG1 was also strongly activated in the presence of cells of the opposite mating type. CaFig1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) was visible only during the mating response, when it localized predominantly to the plasma membrane and perinuclear zone in mating projections and daughter cells. At the plasma membrane, CaFig1-GFP was visualized as discontinuous zones, but the distribution of perinuclear CaFig1-GFP was homogeneous. Exposure to pheromone induced a 5-fold increase in Ca2+ uptake in mating-competent opaque cells. Uptake was reduced substantially in the fig1Δ null mutant. CaFig1 is therefore involved in Ca2+ influx and localizes to membranes that are destined to undergo fusion during mating.

INTRODUCTION

Candida albicans is part of the normal microflora in the gastrointestinal tract and is also a clinically important opportunistic pathogen in humans. A parasexual mating pathway in this obligately diploid fungus has been investigated intensively over the last 10 years, and the studies have shown similarities to and distinct differences from the orthologous mating process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. C. albicans mating may occur on or within the human body and has been shown to occur either through heterothallic or homothallic interactions (2, 16, 23, 28, 35, 36). Transcriptome studies showed that the mating response involved the upregulation of a specific set of genes via the transcription factor Cph1, which also regulates virulence factor expression and promotes filamentous growth. This suggests that the mating response in C. albicans may directly influence host-pathogen interactions as well as creating novel recombinant genotypes via genetic recombination (7, 55). Although the activity of pheromone-regulated transcription factors has been described, the function of their effectors has received less attention.

Unlike the case for mating in the haploid yeast S. cerevisiae, diploid C. albicans cells must first become homozygous at the mating-type locus (MTL), which promotes the switch from white yeast-shaped cells to mating-competent, bean-shaped opaque cells (22, 33, 36). The mechanism that leads to homozygosity in vivo is not well understood, but the genotype can be generated in vitro either by deletion of the MTLa or MTLα genes or by plating cells on l-sorbose, which causes loss of one copy of chromosome 5 bearing the MTL (24, 35). In vitro, MTL-homozygous cells arise predominantly by the loss of one chromosome 5 homolog, followed by duplication of the retained homolog (51). MTL-homozygous cells switch to the opaque form at high frequency to produce mating-competent, pheromone-secreting mating partners that form shmoo mating projections (34). In the process of shmoo formation, pheromone-dependent chemotropism can occur in a biofilm which stabilizes chemotropic gradients, hence, facilitating the directed growth of mating projections toward each other (16). Chemotropism is followed by fusion and the formation of a tetraploid daughter cell (6).

In S. cerevisiae, calcium influx is essential for cell survival and efficient fusion of gametes during the mating process (17). In C. albicans, directional growth responses depend on the influx of calcium ions through calcium channels in the plasma membrane (10, 12). Two calcium uptake systems in S. cerevisiae have been described, and homologous systems in C. albicans have been identified (12, 37, 38). The high-affinity calcium uptake system (HACS), comprising the Mid1-Cch1 complex, is activated in low-Ca2+ medium and in response to alkaline, cold, iron, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (8, 40, 48). A third protein, Fig1 (mating factor-induced gene 1), was identified as a component of the low-affinity calcium uptake system (LACS) that was activated during growth in rich medium (37). In C. albicans, deletion of calcium channel gene CCH1 or MID1 reduced Ca2+ uptake during vegetative growth, but deletion of FIG1 had no measurable effect on calcium ion transport in yeast or hyphal cells (12). However, Cafig1Δ null mutants had altered hyphal tropic responses, suggesting that CaFIG1 was expressed at low levels during vegetative growth (12). FIG1 expression was upregulated in both S. cerevisiae and C. albicans in response to mating pheromone (34, 38). In S. cerevisiae, FIG1 expression increased 5- to 7-fold in response to mating pheromone and S. cerevisiae Fig1-green fluorescent protein (ScFig1-GFP) was distributed homogeneously in the plasma membrane of shmoos and to occasional reticular or punctate intracellular foci (38). Deletion of ScFIG1 resulted in incomplete fusion between the tips of mating shmoos, which was thought to be due to the loss of a calcium-dependent membrane repair mechanism (1, 38). Transcription profiling in C. albicans suggested that Fig1 function could be likewise predominantly associated with the mating process because white/opaque switching and exposure to mating pheromone caused a significant increase in FIG1 gene expression (34).

There is no clear Fig1 homologue outside the fungal kingdom (17, 54), but the protein sequence contains characteristics found in the large mammalian PMP22/EMP/MP20/claudin superfamily (NCBI accession number pfam00822), the members of which selectively limit or promote paracellular ion flux across epithelial tight junctions and regulate the expression of proteins at the cell surface (44, 49). Sequence characteristics include four putative transmembrane domains and a conserved claudin motif [GΦΦGxC(n)C, where Φ is a hydrophobic amino acid and n is any number] in the large first extracellular loop (29, 45). Claudin-like proteins in fungi include Sur7 in C. albicans and Dni1 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Sur7 is an eisosome protein involved in plasma membrane organization and cell wall growth (4). In S. pombe, Dni1-GFP localized to sites of apposition between mating cells, and its deletion caused fusion defects which appeared to be due to membrane mislocalization (15). These two claudin-like proteins in fungi therefore appear to be involved in membrane dynamics.

In C. albicans, Fig1 has been associated with tip reorientation in response to environmental cues. Chemotropism of mating projections in response to pheromone and thigmotropism of vegetative hyphae require directionally regulated polarized growth (12, 17). The molecular processes involved in tip guidance are not well understood but appear to involve Ca2+ uptake (9). Both polarized growth morphologies are Cph1 dependent, and gene deletion and transcription studies indicate that Fig1 activity could be involved in Ca2+ influx and in tropic tip guidance (12, 14, 34). However, the role of Fig1 in shmoo orientation and in mating for C. albicans has not been defined. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the role of Fig1 during mating by studying calcium uptake, gene expression, and protein localization during the C. albicans mating process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, culture conditions, and general genetic manipulation.

The C. albicans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. White and opaque cells were maintained on YPD agar (2% [wt/vol] peptone, 2% [wt/vol] glucose, 1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% [wt/vol] agar) (Oxoid) at 30°C and 25°C, respectively. SD medium (0.67% [wt/vol] yeast nitrogen base [YNB] without amino acids [BD], 2% [wt/vol] glucose, 0.067% [wt/vol] complete supplement mix minus uracil [CMS-uracil; Qbiogene, Cambridge, United Kingdom]) or SD medium supplemented with 1 mg/ml 5-fluoroorotic acid (Melford) and 25 μg/ml uridine (Sigma) was used for selecting uridine prototrophs or auxotrophs, respectively. Strains with homozygosity (a/a or α/α) or hemizygosity (a/− or α/−) at the MTL locus were derived by l-sorbose selection (24) or by deletion mutagenesis (52), respectively. For monosomic chromosome 5 selection, colonies were grown on SD medium supplemented with 2% (wt/vol) l-sorbose instead of glucose. The presence of MTLa and/or MTLα was verified by colony PCR using primers mtla5, mtla3, mtlα5, and mtlα3, listed in Table 2 (35). Deletion of the whole MTL was based on previously used methods using the nourseothricin resistance gene, CaSAT1, as a selectable marker (52). Opaque cells were obtained from red sectors picked from colonies grown on YPD plates supplemented with 5 μg/ml phloxine B (cyanosine; Sigma) (5). Extensor PCR with proofreading activity (Thermo Scientific) was used for amplification of cassettes used for transformation.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | MTL | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAI4 | ura3Δ iro1Δ::imm434/ura3Δ iro1Δ::imm434 | a/α | 19, 20 |

| NGY152 | CAI4/CIp10, as CAI4, RPS1/rps1::pCIp10 | a/α | 11 |

| NGY372 | As CAI4, fig1Δ::dpl200/fig1Δ::dpl200/RPS1/rps1::pCIp10 | a/α | 12 |

| NGY493 | As CAI4, FIG1/FIG1-GFP | a/α | This study |

| NGY494 | As CAI4, FIG1/FIG1-GFP | a/a | This study |

| NGY495 | As CAI4, FIG1/FIG1-GFP | α/α | This study |

| NGY496 | As CAI4, RPS1/rps1::placpoly6-PFIG1 | a/α | This study |

| NGY497 | As CAI4, RPS1/rps1::placpoly6-PFIG1 | a/a | This study |

| NGY498 | As CAI4, RPS1/rps1::placpoly6-PFIG1 | α/α | This study |

| NGY499 | CAI4 | −/α | This study |

| NGY500 | CAI4 | a/− | This study |

| NGY501 | As CAI4, fig1Δ::dpl200/fig1Δ::dpl200/RPS1/rps1::pCIp10 | −/α | This study |

| NGY502 | As CAI4 fig1Δ::dpl200/figΔ::dpl200/RPS1/rps1::pCIp10 | a/− | This study |

| NGY576 | As CAI4, fig1Δ::dpl200/FIG1-GFP (A)a | a/α | This study |

| NGY577 | As CAI4, fig1Δ::dpl200/FIG1-GFP (B)a | a/α | This study |

Independent transformant.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer (reference) | Sequence (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|

| FIG1-GFP-F | TTTAAGTGCTTGTTTATCATGGTGGATGGAAATTAGAATGAGTAAATTGAATGGAAAATCACTGCAACACCAACAACAACCACTGGTGGATACAAAAATTGGTGGTGGTTCTAAAGGTGAAGAATTATT |

| FIG1-GFP-R | CTACATTGTTTATGAGTTGTTGATTTATTGACTTGTGTTGTTATGTCAGTAGAAGACTATAAACGGTTTTTATTGTATTTTTTTGGCAGAAATTTGTACATCTAGAAGGACCACCTTTGATTG |

| CAI4-FIG1-F | ATTATCCTTTGTTATTGTGTC |

| xFG-f/F-R | AAATTCTAACAAGACCATGTG |

| Meg17-F (30) | GGTTGAATTAGATGGTGATG |

| Meg16-R (30) | CATACCATGGGTAATACCAG |

| FIG1-plac-F | CGCATCTGCAGACCATTTTTAGCTACCATTGC |

| FIG1-plac-R | GGCTAGCTCGAGATACAATGGTGAATTTCAATGG |

| mtla5 (35) | TTGAAGCGTGAGAGGCAGGAG |

| mtla3 (35) | GTTTGGGTTCCTTCTTTCTCATT |

| mtlα5 (35) | TTTCGAGTACATTCTGGTCGCG |

| mtlα3 (35) | TGTAAACATCCTCAATTGTACCC |

| Clp10-GS | GTACATTCCTACTCCTGTTCG |

Underlining indicates region of homology with genomic DNA flanking the 3′ end of the FIG1 gene.

Construction of FIG1-LacZ reporter.

The genomic region between the stop codon of orf19.137, upstream of FIG1, and the FIG1 start codon (315 bp) was amplified using primers FIG1plac-F and FIG1plac-R, containing restriction sites PstI and XhoI, respectively. The amplicon was poly(A)-tailed, purified, and ligated into plasmid pGEM-T Easy to generate plasmid pGEMT-PFIG1. The pGEMT-PFIG1 fragment containing the FIG1 promoter was excised by digestion with PstI and XhoI and ligated upstream of the promoterless Streptococcus thermophilus lacZ gene in plasmid placpoly6 (39) to generate plasmid placpoly6-PFIG1. Correct ligation and orientation of the FIG1 promoter was confirmed by PCR using primers FIG1plac-F and Clp10-GS. The placpoly6-PFIG1 plasmid possesses the URA3 gene for selection in C. albicans. StuI-digested placpoly6-PFIG1 was targeted to the RPS1 site in CAI4 (19). Transformants were analyzed by PCR using primers FIG1plac-F and Clp10-GS to verify genomic localization and Southern analysis to screen out transformants with multiple insertions.

Construction of FIG1-GFP fusions.

Construction of the Fig1-GFP fusion protein was carried out using a PCR-based method described previously (19). In the CAI4 (FIG1/FIG1) or fig1Δ/FIG1 (heterozygous) background, the stop codon of one of the FIG1 alleles was replaced by the cassette containing GFP and the prototrophic marker URA3 amplified from plasmid pGFP-URA3 by using long primers FIG1-GFP-F and FIG1-GFP-R. The fusion construct of FIG1-GFP was confirmed by PCR using primers CAI4-FIG1-F and xFG-f/F-R and by Southern blotting. Transcription of GFP was verified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using primers Meg17-F and Meg16-2-R (30).

Thigmotropism assay.

Thigmotropism assays were carried out as previously described to determine whether the GFP-Fig1 allele was functional (12). Briefly, yeast cells were adhered to poly-l-lysine-coated quartz slides featuring ridges of 0.79 μm ± 40 nm and a pitch of 25 μm (Kelvin Nanotechnology, Glasgow, United Kingdom). Slides were incubated in 20 ml prewarmed 20% (vol/vol) newborn calf serum–2% (wt/vol) glucose at 37°C for 6 h. The number of hyphae reorienting on contact with a ridge was expressed as the percentage of the total observed interactions. A minimum of 100 interactions was observed per strain in each experiment, and results were reported as means ± standard errors from a minimum of 3 independent experiments.

Synthesis of α-factor peptide.

The α-pheromone 13-mer peptide GFRLTNFGYFEPG (7) was synthesized by Open Biosystems. Freeze-dried powder was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma) to 100 mg/ml as master stock solution and further diluted 10-fold in sterile water to make working stock solutions.

LacZ reporter of FIG1 promoter activity.

Stationary-phase cells carrying the FIG1p-LacZ construct were cross-streaked on SD agar by using replica plating. Plates were incubated for 48 h at room temperature. Cells were lysed by flooding the plate with 15 ml chloroform and incubating at room temperature for 5 min. Excess chloroform was poured off, and the plate was air dried in a flow hood for 10 min. Low-melting-point 1% agarose in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer containing 250 μg/ml X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) was poured at an approximate temperature of 45°C. Plates were sealed and incubated at 30°C overnight. For quantitative measurement of enzyme activity, a single opaque colony was inoculated into 10 ml YPD and incubated at 23°C for 48 h to reach stationary phase. The white/opaque ratio of the culture was verified by light microscopy. Opaque cells were subcultured into 100 ml fresh YPD at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 and incubated at 23°C for 5 h prior to the addition of pheromone. For positive controls, opaque cell suspensions were mixed at a 1:1 ratio in YPD without pheromone. After a further 12 h of incubation at 23°C, the OD600 was recorded and 10-ml samples were centrifuged and pellets stored at −20°C. For analysis, cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol) in Eppendorf tubes. Chloroform (50 μl), SDS (0.1%), and samples were shaken vigorously for 5 min to lyse cells. Samples were prewarmed at 37°C, and then 200 μl of 4 mg/ml prewarmed ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) was added. After 2 h, 0.8 ml of the reaction mixture was removed and mixed with 0.4 ml 1 M Na2CO3 to stop the reaction. The cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation. The supernatant was removed and the optical density was read at a wavelength of 420 nm. Calculations of β-galactosidase (βgal) activities were based on the method of Munro et al. (39).

Imaging of mating by fluorescence microscopy.

Both a and α opaque cells were grown in modified Lee's medium (MLM) (5a) to stationary phase. Samples of 0.5 ml of each mating type were mixed at a 1:1 ratio in 50 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Oxoid), dropped onto YPD agar, and incubated at 25°C for 48 h. A sample of the mating mixture was washed once with PBS, centrifuged, and resuspended in 100 μl PBS. Nuclei and cell wall chitin were visualized using DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) at 200 μg/ml in DMSO and 100 μg/ml calcofluor white (CFW) (Sigma), respectively. The styryl dye FM4-64 (Invitrogen) was used at 1 μg/ml for vacuole staining (46). For DAPI and CFW staining, samples were first incubated in CFW and then DAPI at room temperature for 45 min each and finally washed once with PBS. For FM4-64 and CFW costaining, cells were resuspended in 100 μl modified Lee's medium before FM4-64 was added and incubated at room temperature with agitation for 45 min. Cells were then washed once with modified Lee's medium and stained with CFW as described above. For microscopy, 5 μl of cell suspension was spotted onto a glass slide and covered with a coverslip, and the edges were sealed with a 1:1:1 mix of molten petrolatum, paraffin, and lanolin. Images were captured using a Delta Vision RT Deconvolution imaging system and processed using the Imaris Softworx suite version 1.3 (46).

Calcium uptake measurements.

Opaque cells were grown in 5 ml modified Lee's medium at 25°C for 48 h until they reached stationary phase. The white/opaque ratio was determined by light microscopy, and cultures of >99% opaque cells were used for further analysis. Cells were washed twice in sterile H2O and resuspended in 5 ml modified Lee's medium at 3 × 107 cells/ml. Ca2+ uptake was determined in mating mixtures, in which a and α cells were used at a 1:1 ratio and a density of 3 × 107 cells/ml or in MTLa cells after the addition of α-pheromone to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Trace 45Ca2+ (PerkinElmer) was added to cultures at time zero. The OD600 of the cell culture and uptake of 45Ca2+ were determined at 12 h for mating cells or 3 h for α-pheromone-induced cells. Culture samples were filtered through glass microfiber paper disks (25-mm diameter) (Whatman, Kent, United Kingdom) by using a Millipore filtration unit. Filters were washed with 25 ml buffer containing 5 mM Ca2+ and dried at 80°C for 45 min. 45Ca2+ activity was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

Bioinformatic analysis.

Candidate protein transmembrane topology was analyzed using Phobius. NetNGlyc was used for prediction of N-glycosylation sites. FIG1 orthologues were aligned using ClustalW from the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI).

RESULTS

Orthologous Fig1 structure and conserved motifs.

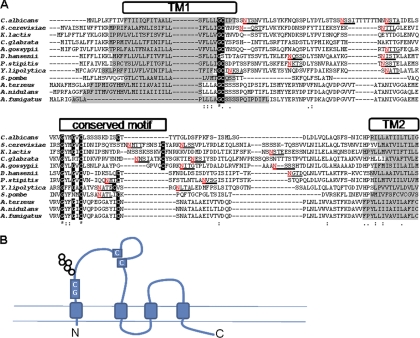

Researchers have identified Fig1 orthologues in the sequenced genomes from the Ascomycota group but not in those from the basidiomycetes, Ustilago maydis, or zygomycete Rhizopus oryzae (42). Sequence alignment using ClustalW showed that all orthologues contained 4 potential transmembrane (TM) domains, with two conserved motifs in the predicted extracellular loop region between TM1 and TM2 (Fig. 1A and B). The glycine-cysteine motif was conserved in all species, with the exception of Debaromyces hansenii, and located at the C terminus of TM1. The second domain, GΦΦGxC(n)C, is a feature of the claudin superfamily. With the exception of the Pezizomycotina subgroup that consisted of 3 Aspergillus species, all species contained 1 to 4 potential N-glycosylation sites in the TM1-TM2 intervening region. Within the claudin superfamily, the positioning of N-glycosylation sites between TM1 and TM2 is a characteristic of the EMP (epithelial membrane protein) subgroup (44).

Fig. 1.

Predicted structure and conserved motifs in fungal orthologues of Fig1. (A) The amino acid sequences of the extracellular regions of Fig1 orthologues from 12 sequenced Ascomycota fungal species were aligned using ClustalW. Areas with a gray background indicate putative hydrophobic transmembrane domains predicted using Phobius. Highly conserved amino acid residues are highlighted with a black background and constitute a conserved Gly-Cys motif and a second conserved motif that is characteristic of the claudin superfamily. Putative N-glycosylation sites, predicted by NetNGlyc, are underlined, and the modified asparagine residues are shown in red. K. lactis, Kluyveromyces lactis; C. glabrata, Candida glabrata; A. gossypii, Ashbya gossypii; P. stipitis, Pichia stipitis; Y. lipolytica, Yarrowia lipolytica; A. terreus, Aspergillus terreus; A. nidulans, Aspergillus nidulans; A. fumigatus, Aspergillus fumigatus. *, identical; :, conserved substitution; ·, semiconserved. (B) The predicted structure of the Fig1 protein family suggests that there are four transmembrane domains giving rise to two extracellular loops. The conserved Gly-Cys, N-glycosylation, and claudin motifs are contained within loop 1.

FIG1 deletion reduces calcium uptake under mating conditions.

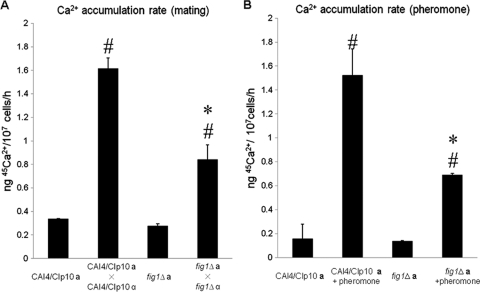

To determine whether Fig1 is involved in Ca2+ uptake during mating in C. albicans, mating-competent a or α (MTL-homozygous) fig1Δ deletion mutants were generated from a parent MTLa/α strain, NGY372 (12). Homozygous fig1Δ a (NGY502) and fig1Δ α (NGY501) strains underwent normal white/opaque switching (data not shown). The accumulation of 45Ca2+ in a 1:1 mixed population of opaque mating-competent control strains, CAI4 a (NGY500) and CAI4 α (NGY499), increased 5-fold over a 12-h period, indicating that Ca2+ uptake occurs during mating in C. albicans (Fig. 2A). A similar increase was observed when the CAI4 a strain was exposed to α-pheromone (Fig. 2B). Deletion of FIG1 did not affect Ca2+ accumulation in unstimulated cells, but reduced levels of uptake occurred in fig1 null mutants in mating populations and in fig1 MTLa cells that were treated with α-pheromone.

Fig. 2.

The effect of FIG1 deletion on calcium uptake under mating conditions. (A) Uptake of 45Ca2+ in mating populations of the control strain or the fig1Δ mutant was determined by mixing mating-competent a and α opaque cells at a ratio of 1:1. (B) Uptake of 45Ca2+ in cultures of mating-competent CAI4/CIp10 a (NGY500) cells or fig1Δ a (NGY502) cells, with and without the addition of 10 μg/ml α-pheromone, was determined. Means and standard deviations (error bars) were from two independent experiments. Asterisks denote a significant difference from the value obtained for the control strain under same treatment. Number signs indicate a significant difference from the value for the relevant untreated control strain (P < 0.05 [two-tailed Student's t test]).

FIG1 expression is activated by α-pheromone and mating.

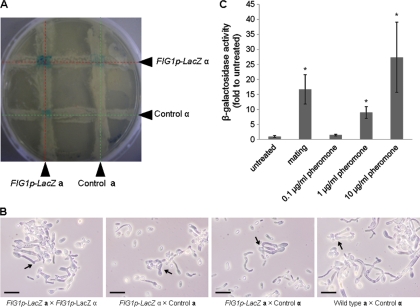

Activation of the FIG1 promoter was assayed using strains bearing the FIG1 promoter inserted upstream of the LACZ reporter gene. Opaque-phase MTLa and MTLα control strains carrying the FIG1p-LacZ reporter construct (FIG1p-LacZ a and FIG1p-LacZ α strains) were cross-streaked on solid YPD agar and incubated at room temperature for 48 h. Whole-plate images were photographed following cell lysis and overlay of X-Gal. Blue pigment was visible only where streaks of cells of opposite mating types carrying the FIG1p-LacZ reporter intersected, indicating that FIG1 expression was activated when mixed populations of MTLa and MTLα occurred together but not in populations with homogeneous mating types (Fig. 3A). As predicted, fainter blue pigment was observed at the intersection of Fig1p-LacZ-carrying strains of either mating type with cells carrying no reporter. Shmoo formation and cell fusion were observed in all cell samples picked from the cross-streaked intersections and viewed by light microscopy (Fig. 3B), indicating that the FIG1 promoter was activated in cells of both mating types.

Fig. 3.

Fig1 promoter activation in response to pheromone and cells of the opposite mating type. (A) MTLα and MTLa cells of the control strain were cross-streaked on YPD agar with MTLα and MTLa cells carrying the FIG1p-LacZ reporter. After 48 h of incubation at 25°C, β-galactosidase activity was determined by the appearance of blue pigment, indicating transcription of LacZ driven by the activated FIG1 promoter. (B) The morphology of cells taken from the four cross-streaked intersections was viewed by light microscopy. Arrows indicate mating events. Scale bars = 10 μm. (C) FIG1p-LacZ a cells were mixed with FIG1p-LacZ α (NGY498) cells in YPD medium at a 1:1 ratio and incubated at 25°C. FIG1p-LacZ a (NGY497) cells were treated with α-pheromone at increasing concentrations (0.1, 1.0, and 10 μg/ml). Promoter activity was measured in triplicate in a colorimetric β-galactosidase activity assay in 3 independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05; two-tailed Student's t test) compared to the value for the untreated sample. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Opaque-phase MTLa and MTLα control strains carrying the FIG1p-LacZ reporter construct (FIG1p-LacZ a and FIG1p-LacZ α strains) were mixed in a 1:1 ratio in liquid MLM and incubated at 25°C for 12 h. Colorimetric analysis showed that exposure to cells of opposite mating types induced a 16-fold increase in FIG1 expression compared to that of populations of a single mating type (Fig. 3C). Opaque, mating-competent FIG1p-LacZ a cells grown in liquid YPD medium were exposed to increasing concentrations of synthetic 13-mer α-pheromone for a period of 12 h. α-Pheromone at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml failed to induce a detectable increase of FIG1 promoter activity over that observed in unstimulated cells, but activity increased in a dose-dependent manner on exposure to 10-fold increases in the α-pheromone concentration (Fig. 3C). From this, the concentration of pheromone produced by the mixture of mating cells in 12-h cultures was estimated to be around 5 μg/ml.

Dynamics of Fig1-GFP expression.

To visualize Fig1-GFP expression and localization in single cells during shmoo formation and mating, an enhanced GFP cassette containing the URA3 auxotrophic marker was fused to the C terminus of the Fig1 protein in the FIG1/FIG1 and fig1Δ/FIG1 genetic backgrounds. FIG1-GFP was therefore under the transcriptional control of the native FIG1 promoter (21). To test whether the Fig1-GFP fusion was functional, strains harboring a single GFP-tagged allele of FIG1 were assayed for their ability to reorient their growing tips on contact with ridges in the substrate. In previous studies, the fig1Δ/fig1Δ null mutant was significantly defective in this thigmotropic response (12). The two fig1Δ/FIG1-GFP independent transformants (NGY576 and NGY577) exhibited thigmotropic responses that were not significantly different from those of the control strain, unlike the null mutant, which was defective in thigmotropism (Fig. 4A). This suggests that FIG1-GFP was functional. The same result was observed for the FIG1/FIG1-GFP (NGY493) strain. This strain was used to generate mating-competent FIG1-GFP a (NGY494) and FIG1-GFP α (NGY495) strains by selection on l-sorbose, followed by PCR screening for the two mating type alleles. Opaque cells were picked and restreaked from sectored white cell colonies grown in the presence of phloxine B. FIG1-GFP a cells were exposed to 50 μg/ml α-pheromone for a period of 12 h, and images were captured using time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. Fig1-GFP was detectable at the site of shmoo formation 40 to 60 min after the addition of α-pheromone, as the emerging shmoo tip itself became visible (Fig. 4B). Fig1-GFP localized primarily to the shmoo apices. Fig1-GFP associated with the entire shmoo structure during the early stages but became tip biased in more elongated cells after 4 h of pheromone exposure (Fig. 4C). The same Fig1-GFP distribution was observed in populations of mating cells on YPD agar (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 4.

Temporal expression and localization of Fig1-GFP during shmoo formation and extension. (A) Cells expressing a single copy of FIG1-GFP show normal contact-sensing responses to a ridged substrate (error bars represent standard errors of the means [n = 3]). Asterisk indicates a significant difference compared to the control strain (P < 0.01; Dunnett's t test). (B) Bean-shaped mating-competent FIG1-GFP a cells in modified Lee's medium were treated with 50 μg/ml α-pheromone, and image capture commenced immediately for a period of 100 min. (C) Cells were treated at 0 h (time zero) with 50 μg/ml α-pheromone. Image capture started at 4 h and continued until 13 h. Scale bars = 5 μm.

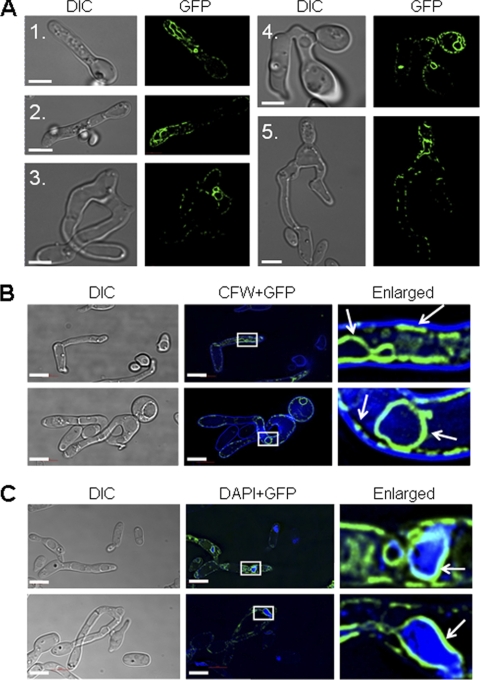

Fig. 5.

Fig1-GFP localization in shmoos and fused cells. (A) FIG1-GFP a (NGY494) and FIG1-GFP α (NGY495) cells were mixed at a ratio of 1:1, spotted on 2% YPD agar, and incubated for 48 h at 25°C. Cells were taken from the plate and viewed by fluorescence microscopy. Fig1-GFP was observed in shmoos (panels 1 and 2), a zygote (panel 3), and daughter cells (panels 4 and 5). Cell wall chitin was stained with 100 μg/ml CFW. Fig1-GFP (green) localized in microdomains adjacent to the CFW-chitin wall layer (blue; arrows) (B) and more homogeneously adjacent to DAPI-stained perinuclear regions (enlarged image) (C). DIC, differential interference contrast. Scale bars = 5 μm.

Contrasting distribution patterns of Fig1-GFP in the shmoo plasma membrane and the nuclear periphery.

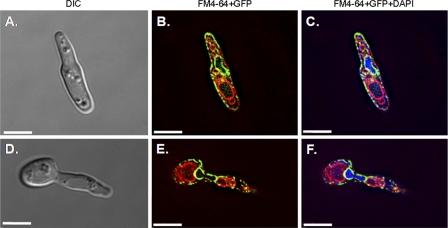

Fig1-GFP was visualized by fluorescence microscopy in shmoos produced in populations of MTLa and MTLα cells mixed at a ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 5A). By using deconvolution microscopy, we observed Fig1-GFP as discontinuous zones at the periphery of the shmoo and in continuous intracellular structures within the shmoo, the body of the mother cell, and the newly formed daughter cell (Fig. 5A). In order to identify the intracellular structures associated with Fig1-GFP, mating cells were stained with DAPI (for nuclei), FM4-64 (for vacuoles), and CFW (for walls). The discontinuous microdomains of Fig1-GFP were immediately adjacent to the CFW-stained cell wall, suggesting that Fig1-GFP localized to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the continuous zones of Fig1-GFP surrounded the nuclear regions, suggesting that it localized to the proximal ER or the nuclear periphery (Fig. 5C and 6). Perinuclear Fig1-GFP persisted during nuclear migration and fusion and was still present at the nuclear periphery in the newly formed daughter cell (Fig. 5A, panels 4 and 5). Elongated DAPI-stained structures that were not associated with Fig1-GFP were observed in the shmoo, possibly representing the localization of mitochondrial DNA (Fig. 6C and F). Fig1-GFP was not detectable in the FM4-64-stained endosomal and vacuolar membranes (Fig. 6). This suggests that Fig1-GFP was not targeted to the vacuole for degradation at a significant rate in shmooing cells.

Fig. 6.

Fig1 in shmooing cells from mating mixtures of FIG1-GFP a and FIG1-GFP α cells stained with DAPI (200 μg/ml) and FM4-64 (1 μg/ml). Scale bars = 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

Fig1 as a member of the claudin superfamily.

Fig1 is a member of a fungus-specific family of proteins that contains sequence characteristics found in the large mammalian PMP22/EMP/MP20/claudin (pfam00822). Claudins combine as dynamic multimeric complexes at the cell membrane. It is thought that their basic function lies in cell-cell adhesion. Claudins are also found in the epithelia of invertebrates, which lack tight junctions, where they are thought to perform a signaling function (50). The family includes regulators of solute movement through epithelial tight junctions, scaffolding proteins for the assembly of adhesion and receptor complexes, and γ subunits for the membrane delivery of the large α subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels (reviewed by Van Itallie and Anderson [45]). In mammalian epithelia, claudins form ion-selective intercellular pores, but there is no evidence that they directly admit ions across the plasma membrane into the cell. Although Fig1 is involved in Ca2+ uptake, its lack of homology to any known ion influx channel suggests that its role may be as an indirect facilitator of Ca2+ influx.

We generated a series of mutant strains that were of the MTLa or MTLα mating type in order to study Fig1 activity under conditions in which the gene was predicted to be highly expressed. Specifically, the aim was to determine whether FIG1 is involved in Ca2+ uptake in C. albicans and to understand more about its role during polarized growth and mating.

Fig1-GFP localizes to shmoo apices during mating.

In a time course study, expression of Fig1-GFP, controlled by the native CaFIG1 promoter, was easily detectable by fluorescence microscopy on exposure of a cells to α-pheromone. Fig1-GFP was observed at the site of mating projection formation, approximately 50 min after exposure to mating pheromone. Fig1-GFP was visible at the cell periphery and in reticular structures throughout the cell but localized predominantly within the mating projection. The reticular distribution in C. albicans contrasted with the pattern observed using a ScFig1::βgal fusion protein during shmoo formation in S. cerevisiae, where Fig1 appeared as punctate spots at the cell periphery (17). By use of deconvolution microscopy of C. albicans cells, we found the distribution of Fig1-GFP at the cell membrane to be discontinuous, which suggested that it may be present in microdomains. CFW staining showed that Fig1-GFP appeared in flattened zones in apposition with the cell wall. The intracellular reticular structures carrying Fig1-GFP localized within bright, perinuclear regions that persisted throughout shmoo formation and cell-cell fusion and in nuclei of the newly formed daughter cell. It is possible that the perinuclear localization of Fig1-GFP resulted from its biosynthesis in the ER. However, many other mating-induced genes, such as FUS1 and PRM1, whose expression is induced in other fungi during mating, do not accumulate in the ER or the nuclear periphery (18, 41). Furthermore, Fig1-GFP was not visualized in the FM4-64-stained vacuolar membrane during shmoo elongation. Low levels of expression of ScFig1::βgal were visible in the perinuclear zone in S. cerevisiae cells prior to treatment with mating pheromone, supporting the possibility that Fig1 may have a second nuclear function (17). It has been reported that in mammalian cells, perinuclear Ca2+ release affects nuclear Ca2+ much more strongly than distal Ca2+ influx and a sustained rise in nuclear [Ca2+] is required for calcineurin-NFAT (the CaCRZ1 product homologue) and cyclic AMP response binding element (CREB) signaling (13, 27, 31, 43). Fig1 may also have a general role in limiting membrane damage or promoting membrane fusion of the nuclear envelope and at the plasma membrane, both of which undergo fusion during mating.

Mating-dependent Fig1 expression and Ca2+ uptake in C. albicans.

Ca2+ uptake increased approximately 5-fold in mixtures of opaque MTLa or MTLα cells, and in MTLa cells treated with α-pheromone (10 μg/ml), an 8- to 10-fold increase in Ca2+ uptake compared to that of untreated controls was observed. Together, these results demonstrate that exposure to mating pheromone in C. albicans mating-competent cells causes a significant increase in the intracellular [Ca2+], as seen in S. cerevisiae (38). Deletion of FIG1 in C. albicans reduced Ca2+ uptake to 50% of the control level, confirming that Fig1 is involved in Ca2+ influx but implying that mating also involves Fig1-independent Ca2+ uptake. The Fig1-LacZ reporter construct was activated in both MTL mating types, demonstrating that this pathway forms part of a general mating response and is not MTL specific. In addition, the level of activity of the Fig-LacZ reporter construct increased in a pheromone dose-dependent manner. Taken together, these results suggest a positive correlation between pheromone concentration, Fig1 expression, and Ca2+ uptake. Mid1-Cch1, the HACS complex, may therefore also contribute to Ca2+ uptake during mating in C. albicans. HACS expression is influenced by the calcineurin-CRZ1 Ca2+-dependent signaling pathway in C. albicans, but its expression is not thought to be highly regulated (26). We have not been able to visualize Cch1-GFP or Mid1-GFP in C. albicans, but in S. cerevisiae, Mid1-GFP was visualized at the plasma membrane and in an ER-like zone around the nucleus in nonmating conditions and did not relocalize to the shmoo on treatment with mating pheromone (25, 32, 53). The highly enriched and spatially distinct domains of Fig1-GFP at the shmoo plasma membrane suggest that the functions of the two Ca2+ uptake systems differ during mating and that Fig1 might be involved in the generation of Ca2+ signals at specific sites. It has been reported that both chelation of extracellular Ca2+ and deletion of FIG1 dramatically reduced mating efficiency of C. albicans (3). Our finding that Fig1 is involved in 50% of the Ca2+ uptake during mating confirms its importance in the mating process.

Mating-independent Fig1 expression.

We previously identified Fig1 as a protein required for the normal thigmotropic response by C. albicans, where FIG1 deletion significantly reduced the ability of hyphal tips to reorient on contact with ridges in the underlying substrate; this role of Fig1 is in contrast to its mating-dependent functions (12). All hyphal tropisms we have studied to date have been shown to be dependent on Ca2+ influx, but deletion of FIG1 did not affect Ca2+ uptake during vegetative growth. Although FIG1 mRNA was detected under all growth conditions tested, including in kidney tissue isolated from infected mice, a Fig1-GFP construct in yeasts or hyphae could not be visualized. This suggests that Fig1 is present at very low levels during vegetative growth but that even basal level expression of Fig1 influences hyphal growth and orientation.

It is possible that the function and activity of Fig1 depend on its colocalization with other effectors. Two lines of evidence in S. cerevisiae suggest that ScFig1 has Ca2+-related and Ca2+-unrelated functions. First, output from the aequorin/Ca2+ reporter peaked during mating, while Fig1-Myc levels remained high, which suggested that Fig1 was still required in the plasma membrane after mating-induced Ca2+ uptake was complete (38). Second, mating-induced rapid cell death was found to be dependent on Fig1 but independent of its Ca2+ uptake activity (54). The involvement of other effectors in Fig1 function is suggested by the observation that membrane localization of Fig1 was necessary but not sufficient for LACS activity (38). In C. albicans, Fig1-GFP localization appeared to be perinuclear and at the plasma membrane. Both membranes are sites of membrane perturbation and fusion during mating. Fig1 was proposed to be necessary in S. cerevisiae for limiting the zone of membrane fusion during mating (38). FIG1 deletion in S. cerevisiae resulted in defective cell fusion during mating, with undissolved wall material at the fusion site, which was rescued by the addition of extracellular Ca2+. Such fusion defects were not observed in fig1 null mutants of C. albicans, but Fig1 could nevertheless function to stabilize membranes in response to perturbation during polarized growth, possibly by limiting membrane expansion during critical stages in morphological change. Two observations provide evidence for this. First, FIG1 deletion resulted in hypha formation on solid SD medium, while the control strain grew as yeast (12). This suggests that Fig1 may be a negative regulator of polarized growth in certain conditions. Second, FIG1 deletion decreases the likelihood that hyphae will reorient the growth axis on contact with a small obstacle (12). Thus, although Fig1 is undoubtedly upregulated as part of the mating signaling pathway, its role may well be more generally related to membrane stability during morphological transitions, whether internally or externally induced. Fig1 therefore participates in the polarized growth of both mating projections and vegetative fungal hyphae, presumably by regulating calcium ion uptake at sites of polarized tip growth. FIG1 expression represents a convenient marker for the mating process, but low levels of Fig1 in nonmating cells also influence the physiology of growth and development of C. albicans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Signalpath EC Marie Curie Actions funding network (a studentship for M.Y. and BBSRC grant BB/E008372/1 to A.B.), and it was funded in part by the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at Iowa, an NIH National Resource. We also acknowledge funding from the BBSRC (SABR) and the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 January 2011.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aguilar P. S., Engel A., Walter P. 2007. The plasma membrane proteins Prm1 and Fig1 ascertain fidelity of membrane fusion during yeast mating. Mol. Biol. Cell 18:547–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alby K., Schaefer D., Bennett R. J. 2009. Homothallic and heterothallic mating in the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. Nature 460:890–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alby K., Schaefer D., Sherwood R. K., Jones S. K., Jr., Bennett R. J. 2010. Identification of a cell death pathway in Candida albicans during the response to pheromone. Eukaryot. Cell 9:1690–1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alvarez F. J., Douglas L. M., Rosebrock A., Konopka J. B. 2008. The Sur7 protein regulates plasma membrane organization and prevents intracellular cell wall growth in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:5214–5225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anderson J. M., Soll D. R. 1987. Unique phenotype of opaque cells in the white-opaque transition of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 169:5579–5588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a. Bedell G. W., Soll D. R. 1979. Effects of low concentrations of zinc on the growth and dimorphism of Candida albicans: evidence for zinc-resistant and -sensitive pathways for mycelium formation. Infect. Immun. 26:348–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bennett R. J., Miller M. G., Chua P. R., Maxon M. E., Johnson A. D. 2005. Nuclear fusion occurs during mating in Candida albicans and is dependent on the KAR3 gene. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1046–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bennett R. J., Uhl M. A., Miller M. G., Johnson A. D. 2003. Identification and characterization of a Candida albicans mating pheromone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:8189–8201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonilla M., Cunningham K. W. 2003. Mitogen-activated protein kinase stimulation of Ca2+ signaling is required for survival of endoplasmic reticulum stress in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:4296–4305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brand A., Gow N. A. 2009. Mechanisms of hypha orientation of fungi. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:350–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brand A., Lee K., Veses B., Gow N. A. 2009. Calcium homeostasis is required for contact-dependent helical and sinusoidal tip growth in Candida albicans hyphae. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1155–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brand A., MacCallum D. M., Brown A. J. P., Gow N. A. R., Odds F. C. 2004. Ectopic expression of URA3 can influence the virulence phenotypes and proteome of Candida albicans but can be overcome by targeted reintegration of URA3 at the RPS10 locus. Eukaryot. Cell 3:900–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brand A., et al. 2007. Hyphal orientation of Candida albicans is regulated by a calcium-dependent mechanism. Curr. Biol. 17:347–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chawla S., Hardingham G. E., Quinn D. R., Bading H. 1998. CBP: a signal-regulated transcriptional coactivator controlled by nuclear calcium and CaM kinase IV. Science 281:1505–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen J., Chen J., Lane S., Liu H. 2002. A conserved mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is required for mating in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1335–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clemente-Ramos J. A., et al. 2009. The tetraspan protein Dni1p is required for correct membrane organization and cell wall remodelling during mating in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Microbiol. 73:695–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Daniels K. J., Srikantha T., Lockhart S. R., Pujol C., Soll D. R. 2006. Opaque cells signal white cells to form biofilms in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 25:2240–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erdman S. E., Lin L., Malczynski M., Snyder M. 1998. Pheromone-regulated genes required for yeast mating differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 140:461–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fleissner A., Diamond S., Glass N. L. 2009. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae PRM1 homolog in Neurospora crassa is involved in vegetative and sexual cell fusion events but also has postfertilization functions. Genetics 181:497–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fonzi W. A., Irwin M. Y. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. García M. G., O'Connor J.-E., Garcia L. L., Martinez S. I., Herrero E., del Castillo Agudo L. 2001. Isolation of a Candida albicans gene, tightly linked to URA3, coding for a putative transcription factor that suppresses a Saccharomyces cerevisiae aft1 mutation. Yeast 18:301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gerami-Nejad M., Berman J., Gale C. 2001. Cassettes for the PCR-mediated construction of green, yellow, and cyan fluorescent protein fusions in Candida albicans. Yeast 18:859–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hull C. M., Johnson A. D. 1999. Identification of a mating type-like locus in the asexual pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Science 285:1271–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hull C. M., Raisner R. M., Johnson A. D. 2000. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science 289:307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Janbon G., Sherman F., Rustchenko E. 1999. Appearance and properties of L-sorbose-utilizing mutants of Candida albicans obtained on a selective plate. Genetics 153:653–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanzaki M., et al. 1999. Molecular identification of a eukaryotic, stretch-activated nonselective cation channel. Science 285:882–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karababa M., et al. 2006. CRZ1, a target of the calcineurin pathway in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1429–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kornhauser J. M., et al. 2002. CREB transcriptional activity in neurons is regulated by multiple, calcium-specific phosphorylation events. Neuron 34:221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lachke S. A., Lockhart S. R., Daniels K. J., Soll D. R. 2003. Skin facilitates Candida albicans mating. Infect. Immun. 71:4970–4976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lal-Nag M., Morin P. 2009. The claudins. Genome Biol. 10:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lenardon M. D., Whitton R. K., Munro C. A., Marshall D., Gow N. A. R. 2007. Individual chitin synthase enzymes synthesize microfibrils of differing structure at specific locations in the Candida albicans cell wall. Mol. Microbiol. 66:1164–1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lipp P., Thomas D., Berridge M. J., Bootman M. D. 1997. Nuclear calcium signalling by individual cytoplasmic calcium puffs. EMBO J. 16:7166–7173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Locke E. G., Bonilla M., Liang L., Takita Y., Cunningham K. W. 2000. A homolog of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels stimulated by depletion of secretory Ca2+ in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6686–6694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lockhart S. R., et al. 2002. In Candida albicans, white-opaque switchers are homozygous for mating type. Genetics 162:737–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lockhart S. R., Zhao R., Daniels K. J., Soll D. R. 2003. Alpha-pheromone-induced “shmooing” and gene regulation require white-opaque switching during Candida albicans mating. Eukaryot. Cell 2:847–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Magee B. B., Magee P. T. 2000. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLalpha strains. Science 289:310–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller M. G., Johnson A. D. 2002. White-opaque switching in Candida albicans is controlled by mating-type locus homeodomain proteins and allows efficient mating. Cell 110:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Muller E. M., Locke E. G., Cunningham K. W. 2001. Differential regulation of two Ca2+ influx systems by pheromone signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 159:1527–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Muller E. M., Mackin N. A., Erdman S. E., Cunningham K. W. 2003. Fig1p facilitates Ca2+ influx and cell fusion during mating of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278:38461–38469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Munro C. A., et al. 2007. The PKC, HOG and Ca2+ signalling pathways co-ordinately regulate chitin synthesis in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1399–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peiter E., Fischer M., Sidaway K., Roberts S. K., Sanders D. 2005. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ca2+ channel Cch1pMid1p is essential for tolerance to cold stress and iron toxicity. FEBS Lett. 579:5697–5703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Proszynski T. J., Klemm R., Bagnat M., Gaus K., Simons K. 2006. Plasma membrane polarization during mating in yeast cells. J. Cell Biol. 173:861–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rispail N., et al. 2009. Comparative genomics of MAP kinase and calcium-calcineurin signalling components in plant and human pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46:287–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shibasaki F., Price E. R., Milan D., McKeon F. 1996. Role of kinases and the phosphatase calcineurin in the nuclear shuttling of transcription factor NF-AT4. Nature 382:370–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Taylor V., Welcher A. A., EST Program Amgen, and Suter U. 1995. Epithelial membrane protein-1, peripheral myelin protein 22, and lens membrane protein 20 define a novel gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 270:22824–22833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Van Itallie C. M., Anderson J. M. 2006. Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 68:403–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Veses V., Gow N. A. 2008. Vacuolar dynamics during the morphogenetic transition in Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 8:1339–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Veses V., et al. 2005. ABG1, a novel and essential Candida albicans gene encoding a vacuolar protein involved in cytokinesis and hyphal branching. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1088–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Viladevall L., et al. 2004. Characterization of the calcium-mediated response to alkaline stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279:43614–43624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wadehra M., Su H., Gordon L. K., Goodglick L., Braun J. 2003. The tetraspan protein EMP2 increases surface expression of class I major histocompatibility complex proteins and susceptibility to CTL-mediated cell death. Clin. Immunol. 107:129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu V. M., Schulte J., Hirschi A., Tepass U., Beitel G. J. 2004. Sinuous is a Drosophila claudin required for septate junction organization and epithelial tube size control. J. Cell Biol. 164:313–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu W., Pujol C., Lockhart S. R., Soll D. R. 2005. Chromosome loss followed by duplication is the major mechanism of spontaneous mating-type locus homozygosis in Candida albicans. Genetics 169:1311–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wu W., Lockhart S. R., Pujol C., Srikantha T., Soll D. R. 2007. Heterozygosity of genes on the sex chromosome regulates Candida albicans virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1587–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yoshimura H., Tada T., Iida H. 2004. Subcellular localization and oligomeric structure of the yeast putative stretch-activated Ca2+ channel component Mid1. Exp. Cell Res. 293:185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang N. N., et al. 2006. Multiple signaling pathways regulate yeast cell death during the response to mating pheromones. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:3409–3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhao R., et al. 2005. Unique aspects of gene expression during Candida albicans mating and possible G1 dependency. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1175–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]