Abstract

Truncated Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) with the 11th β-strand removed is potentially interesting for bioconjugation, imaging, and the preparation of semi-synthetic proteins with novel spectroscopic or functional properties. Surprisingly, the truncated GFP generated by removing the 11th strand, once refolded, does not reassemble with a synthetic peptide corresponding to strand 11, but does reassemble following light activation. The mechanism of this process has been studied in detail by absorption, fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy. The chromophore in this refolded truncated GFP is found to be in the trans configuration. Upon exposure to light a photostationary state is formed between the trans and cis conformations of the chromophore, and only truncated GFP with the cis configuration of the chromophore binds the peptide. A kinetic model describing the light activated reassembly of this split GFP is discussed. This unique light-driven reassembly is potentially useful for controlling protein-protein interactions.

Introduction

Split green fluorescent proteins (GFPs) are useful for making semi-synthetic GFPs1,2,3 containing unnatural amino acids with novel properties, for imaging and bioconjugation, and for fundamental studies of β-strand assembly and stability. We recently showed that split GFPs with one β-strand removed (originally developed for measuring protein solubility4) can readily be obtained for in vitro studies by inserting a loop containing a protease cleavage site between the secondary structural element to be removed and the rest of the protein, cleaving the loop with a protease and removing the structural element by size exclusion chromatography, as shown in Figure 1A 5. Because any of GFP’s 11 β strands or the central helix that contains the chromophore can be made into the C- or N-terminus by circular permutation, this method can be applied to any of these secondary structural elements. Due to the huge diversity of possibilities, a systematic notation was developed as illustrated for the specific case of β strand 11 in Figure 1A 5. In this scheme “loop” refers to the sacrificial loop insertions that contain a protease cleavage site, and “s11” refers to the 11th strand of the β-barrel. A strike through loop implies the loop was cleaved with trypsin (or another protease), and a strike though s11 implies the original peptide was removed by denaturation and size exclusion. Added synthetic peptides are underlined, e.g. s11, and the dot (•) implies that a noncovalent complex has been formed between the protein and the synthetic peptide.

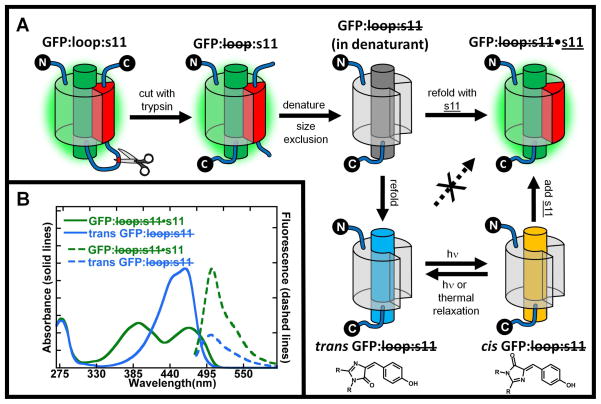

Figure 1.

A) GFP:loop:s11 has a loop containing a proteolytic cleavage site that isolates stave 11 from the rest of the protein and is expressed in high yield with the GFP chromophore formed. This protein is digested with trypsin to make a noncovalent complex GFP: loop:s11, which is then denatured in 6M guanidine hydrochloride to break up the stable noncovalent complex. Size exclusion chromatography then separates GFP: loop:s11 from the native stave 11 in denaturing conditions. When GFP: loop:s11 is diluted out of denaturant in the presence of synthetic strand 11, s11, the GFP: loop:s11•s11 complex is formed, whose absorption and fluorescence spectra are indistinguishable from the original GFP:loop:s11. If, however, GFP: loop:s11 is refolded by itself, in the absence of s11, a new species is formed, denoted trans GFP: loop:s11. Surprisingly, trans GFP: loop:s11 does not non-covalently associate with added s11. If trans GFP: loop:s11 is irradiated, a photostationary state is established between the trans and cis configuration of the chromophore (chromophore structures shown below their cartoon counterparts), and cis GFP: loop:s11 rapidly combines with s11 to form GFP: loop:s11:s11 whose properties are indistinguishable from the original GFP:loop:s11. Note that a β-barrel configuration is shown for GFP: loop:s11 in denaturant, trans GFP: loop:s11 and cis GFP: loop:s11 for purpose of illustration only; the actual structures are not known. B) Absorbance and fluorescence spectra of trans GFP: loop:s11 and GFP: loop:s11•s11. Absorbance spectra of trans GFP: loop:s11 and GFP: loop:s11•s11 are shown by blue and green solid lines, respectively. Fluorescence emission spectra of trans GFP :loop:s11 and GFP: loop:s11•s11 are shown by blue and green dotted lines respectively. The absorbance spectrum of refolded trans GFP: loop:s11 has a single band in the visible region unlike the protein with s11 covalently attached or GFP: loop:s11•s11 (which are indistinguishable). All spectra are normalized by concentration so that the relative intensities of the absorbance spectra reflect differences in extinction coefficients, and the emission spectra relative intensities reflect the difference in extinction coefficient and quantum yield upon excitation at 468nm.

In the initial implementation of this method5, GFP: loop:s11 was refolded from denaturing solution (upper series of steps in Figure 1A) into a solution containing an excess of s11 to make GFP: loop:s11•s11, whose absorption and fluorescence spectra were indistinguishable from the original GFP: loop:s11, which in turn is very similar to GFP itself (the properties of this reassembled protein can be altered by changing the sequence of s111). If instead GFP: loop:s11 is refolded without s11, we were surprised to discover a species whose absorption and fluorescence are quite different from that of GFP as shown in Figure 1B. Also, the fluorescence quantum yield of this refolded form was surprisingly only about five times less than the native, fully folded protein (Figure 1B). This was unexpected as the fluorescence from denatured GFP: loop:s11 (or denatured native GFP) is very low as the chromophore is in an unstructured environment and non-radiative decay pathways lead rapidly to the ground state6. The high fluorescence quantum yield of the chromophore and the decreased yet still existent secondary structure of GFP: loop:s11 observed by circular dichroism suggests that GFP: loop:s11 has some residual structure5. Furthermore, as discussed in detail below, refolded GFP: loop:s11 does not bind to s11. By chance, however, we observed that refolded GFP: loop:s11 does rebind s11 in the presence of light (initially observed in room light). As described in the following and shown schematically in the lower part of Figure 1A, we propose that refolded GFP: loop:s11 has the chromophore in the trans configuration (denoted trans GFP: loop:s11), but light activation creates a photostationary state with the cis configuration of the chromophore (cis GFP: loop:s11), and only cis GFP: loop:s11 can bind s11. We note that cis and trans apply to the chromophores in simple solvent, while these may be twisted somewhat from their ideal geometry by constraints in the protein. Quantitative justification for this model and the conformation of the chromophore is presented in the following, but the framework of the model and notation in Figure 1A will aid the initial discussion of the results.

Results

As seen in Figure 1B, the absorption spectrum of refolded GFP: loop:s11 is quite different from that of either the protonated (peak at 400 nm) or deprotonated (peak at 475 nm) forms of the chromophore observed in native GFP7,8. The observation that the fluorescence quantum yield is quite high suggests that there is some residual structure in refolded GFP: loop:s11 which constrains the chromophore and prevents motions that lead to non-radiative decay. Systematic irradiation of the chromophore in refolded GFP: loop:s11 with visible light leads to a wavelength dependent and light intensity independent change in the absorbance spectrum (Supplementary Figure 1). The wavelength dependence of the changes in the absorbance spectrum suggests that the light generates a photostationary state, where the ratios of concentrations of the two forms (denoted cis and trans GFP: loop:s11) are determined by the product of the ratios of the extinction coefficients, ε, and the photoisomerization quantum yields (ϕ, equation (1))9:

| (1) |

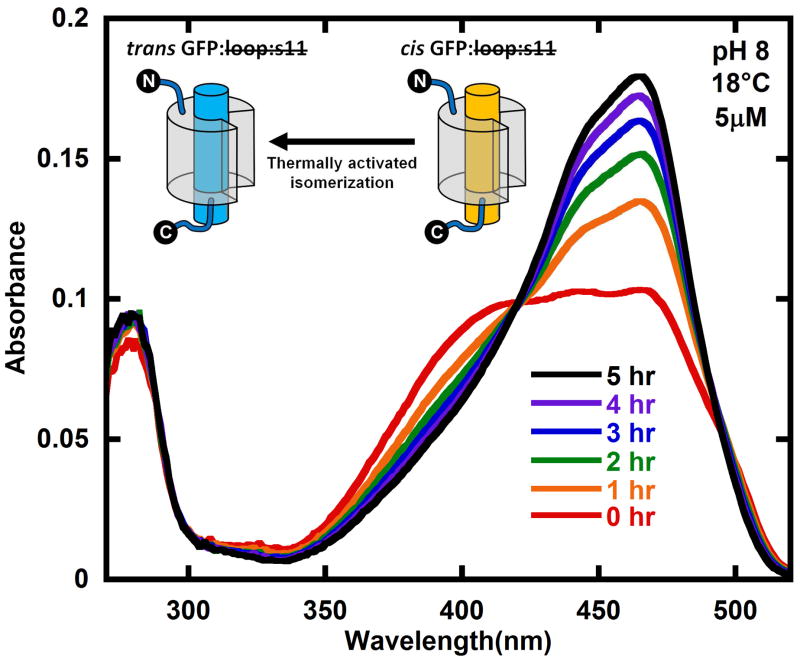

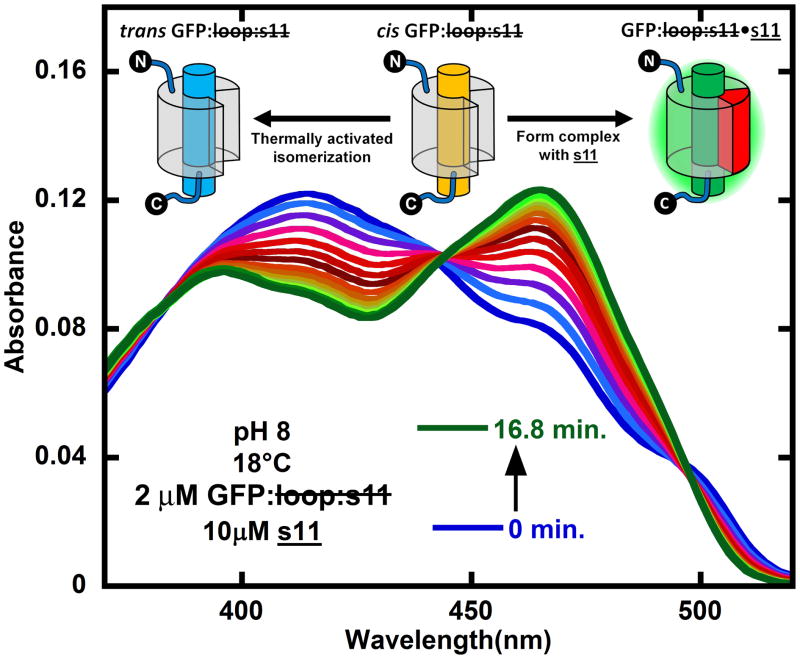

Following creation of the photostationary state, the absorbance spectrum shifts back to the original absorbance spectrum when the sample is left in the dark (Figure 2), where the final spectrum in Figure 2 is nearly identical to that of the original trans GFP: loop:s11 spectrum. If trans GFP: loop:s11 and s11 are mixed together in the dark, no changes in the absorbance spectrum are observed; however, if trans GFP: loop:s11 is light activated to form a photostationary mixture of cis and trans GFP: loop:s11, and s11 is added, the absorbance changes associated with GFP: loop:s11•s11 are quickly observed (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Reformation of trans GFP: loop:s11 (compare final black spectrum with Figure 1B) in the dark after creating the photostationary state of trans and cis GFP: loop:s11 (red) with 460 nm light. The sample was kept rigorously in the dark and the absorption spectrum sampled infrequently. The cartoons show the part of the kinetic model that describes this data. The protein was at a concentration of 5 μM in pH 8 buffer at 18°C. See Figure 5 for kinetics as a function of temperature.

Figure 3.

Competition between cis → trans thermal isomerization and binding of s11 to cis GFP: loop:s11 to form GFP: loop:s11•s11 starting from the initial photostationary mixture of refolded GFP: loop:s11 generated by light activating trans GFP: loop:s11 with 460 nm light (blue). The spectra following from blue to green are shown for every 1.2 minutes after mixing in s11 in the dark. The cartoon inset shows the kinetic model that describes the processes taking place, namely cis GFP: loop:s11 is partitioning between binding s11 to form GFP: loop:s11•s11 and reverting back to trans GFP: loop:s11. The initial concentrations of trans GFP: loop:s11 and s11 were 2 μM and 10 μM, respectively, and they were in pH 8 buffer at 18°C.

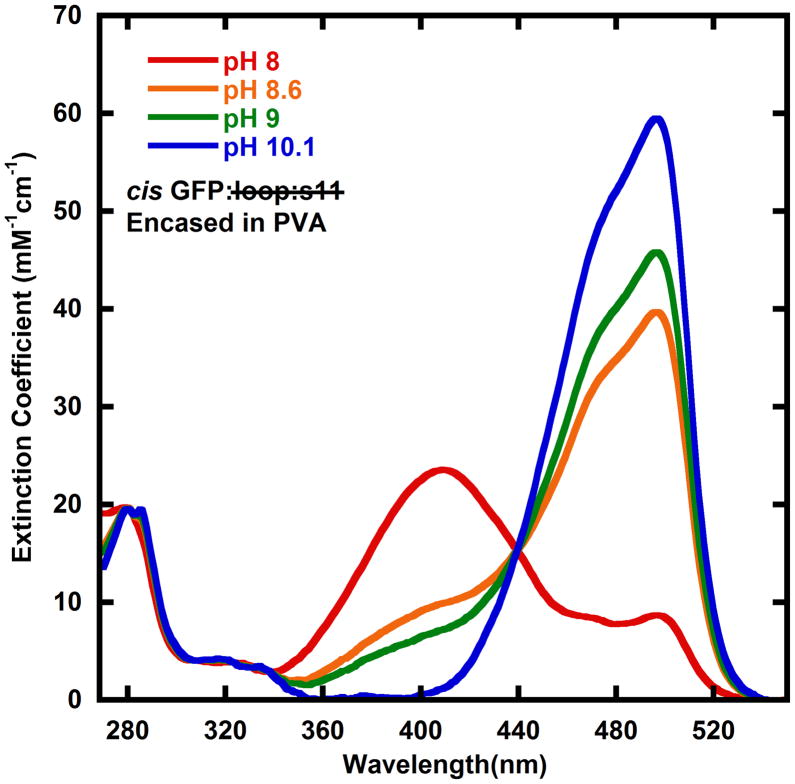

We observed that cis GFP: loop:s11 tends to form stable aggregates that can be characterized by size-exclusion chromatography (see supplementary material), and this interferes with and complicates the determination of the absorbance spectrum of this species for quantitative analysis. We note that this aggregation may be mitigated by supercharging GFP10. In order to avoid aggregation of the protein while still observing the light-induced changes in the absorbance spectrum, GFP: loop:s11 was encased in polymer (PVA) films (Supplementary Figure 5). As the pH is increased the wavelength dependence of the changes in the absorbance spectrum decreases. By pH 10 there is no wavelength dependence to the photostationary state. The subtleties implied by the pH dependence are discussed in detail below. The pH and wavelength dependence allow us to determine the absorption spectrum of cis GFP: loop:s11 (Figure 4).

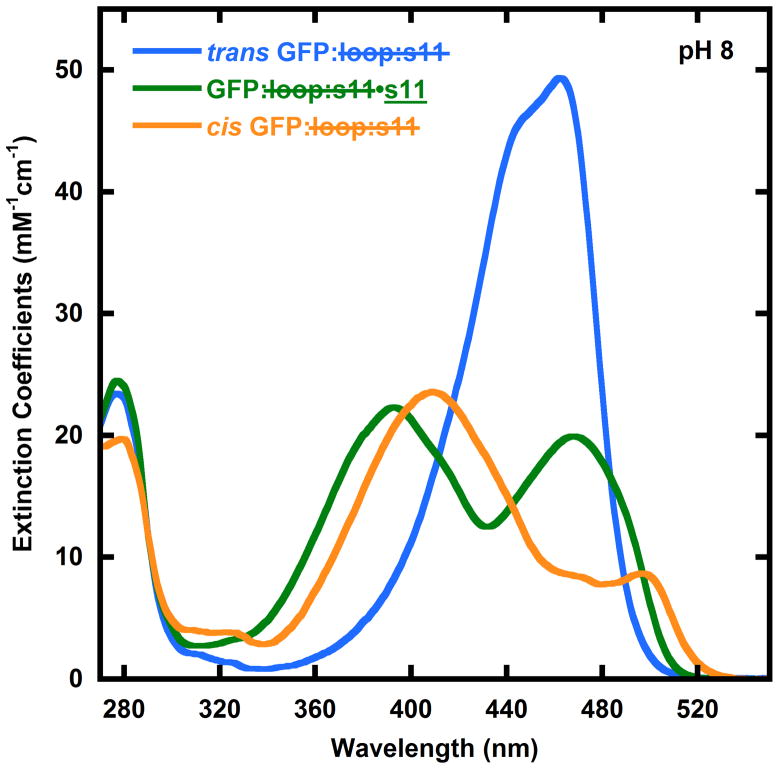

Figure 4.

Absorbance spectra of cis GFP: loop:s11 (yellow), trans GFP: loop:s11 (blue), and GFP: loop:s11•s11 (green). The absorbance spectra of GFP: loop:s11•s11 (green) and trans GFP: loop:s11 (blue) are reproduced from Figure 1B for comparison. The cis GFP: loop:s11 absorbance spectrum is derived from observing the changes in the photostationary state of GFP: loop:s11 with pH and photoactivation wavelength. These absorbance spectra are used to fit the data in Figures 2 and 3 to determine the concentrations of cis GFP: loop:s11, trans GFP: loop:s11 and GFP: loop:s11•s11.

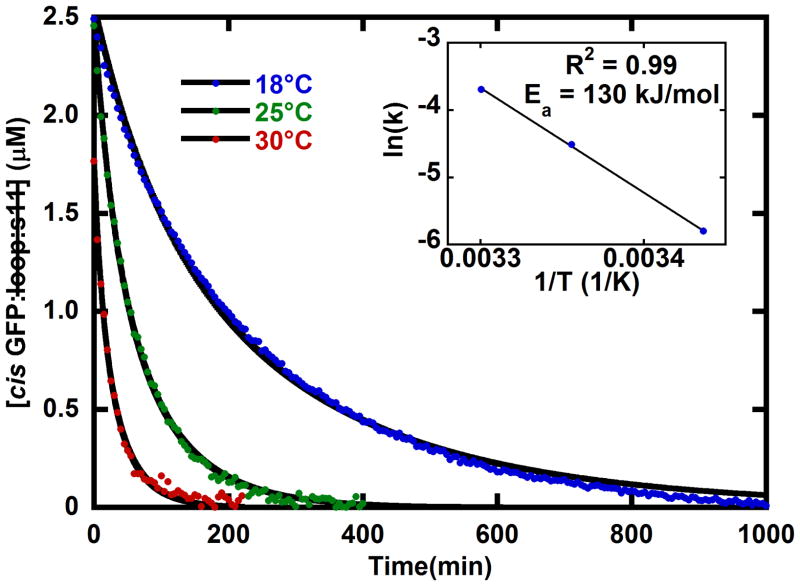

Absorbance spectra of the photostationary state decaying back to trans GFP: loop:s11 (Figure 2) were fit with the basis spectra from Figure 4, and the spectrum of the aggregated protein (Supplementary Figure 4) to give the concentrations in time so that the relevant parameters in the kinetic model in Figure 1A can be determined. As expected by the simple kinetic model in Figure 1A the cis GFP: loop:s11 in the photostationary mixture converts back to trans GFP: loop:s11 when left in the dark (Figure 5). The decay of cis GFP: loop:s11 to trans shows Arrhenius behavior with an activation energy of 130 kJ/mol (Figure 5 inset).

Figure 5.

Temperature dependence of the decay of cis GFP: loop:s11 from the photostationary state to form the more stable trans GFP: loop:s11. The red, green, and blue dots show the concentration decrease in time after the light activated generation of cis GFP: loop:s11 at 30°C, 25°C, and 18°C, respectively. The solid black line fits are obtained from fitting the concentrations of all species with the kinetic model shown in Figure 2 (a unimolecular reaction of cis converting back to trans GFP: loop:s11 and a bimolecular aggregation of cis GFP: loop:s11, see supplementary section). Inset: The temperature dependence shows Arrhenius behavior with an activation energy of 130 kJ/mol. All three samples had a total protein concentration of 5 μM and were in pH 8 buffer.

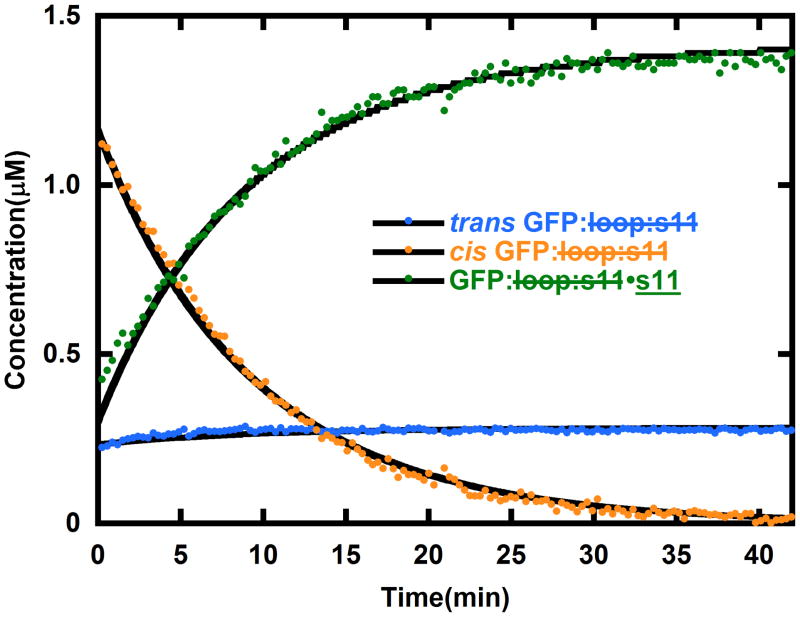

When s11 is introduced to the photostationary mixture of cis and trans GFP: loop:s11, the cis GFP: loop:s11 should partition between binding s11 to form GFP: loop:s11•s11 and converting back to trans GFP: loop:s11 according to the simple kinetic model (schematic in Fig. 4). The absorbance spectra obtained after light activating GFP: loop:s11 and mixing in s11 were fit with the basis spectra shown in Figure 4, and the resulting evolution of concentrations in time were fit with the kinetic model as shown in Figure 6. The kinetic fits reveal that the bimolecular rate constant of s11 binding to cis GFP: loop:s11 is 150 M−1s−1. There is leftover trans GFP: loop:s11 in Figure 6 because the fraction of trans GFP: loop:s11 in the photostationary mixture does not bind the peptide; however, if the sample is illuminated continuously during the reassembly, the entire sample can be driven to GFP: loop:s11•s11. Additionally, when GFP: loop:s11•s11 at 1 μM concentration was mixed with a hundred times excess s11 with the E222Q mutation (the E222Q mutation is known to change the absorbance spectrum1), no changes in the absorbance spectrum were observed over a period of days. Also, attempts to compete out E222Q s11 with s11 were unsuccessful. The absence of displacement allows for an estimate that the upper bound of the binding constant is sub picomolar, assuming that E222Q s11 and s11 have identical on and off rates. We also note that once GFP: loop:s11•s11 is formed, further irradiation does not lead to displacement of strand 11. Efforts to discover conditions in which light-induced dissociation would be possible are in progress as such a system could have obvious applications in imaging.

Figure 6.

The evolution of concentrations of trans GFP: loop:s11 (blue), cis GFP: loop:s11 (yellow) and GFP: loop:s11•s11 (green) after generating a photostationary mixture of cis and trans GFP: loop:s11 and mixing in s11. The solid black lines are generated by the model in Figure 3 (a unimolecular reaction of cis converting back to trans GFP: loop:s11, and a bimolecular reaction of s11 forming a complex with cis GFP: loop:s11). As expected from this model the cis GFP: loop:s11 concentration drops as the other species rise, and after the cis GFP: loop:s11 is gone the concentrations of trans GFP: loop:s11 and GFP: loop:s11•s11 remain constant. If the sample is excited with additional light the re-assembly can be driven to completion (data not shown). The initial concentrations of trans GFP: loop:s11 and s11 in this experiment were 2 μM and 10 μM, respectively, and they were in pH 8 buffer at 18°C.

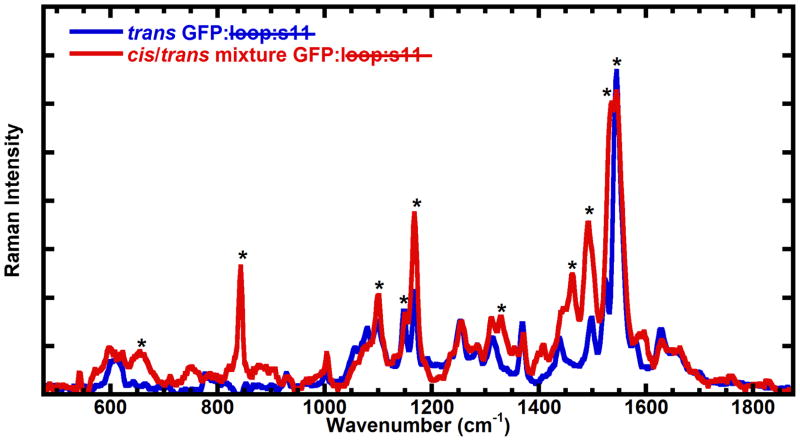

Pre-resonance Raman spectroscopy is able to distinguish between the cis and trans configuration of the GFP chromophore11, so Raman spectra were obtained for the refolded GFP: loop:s11 before and after light activation (Figure 7). The spectra were obtained at 170K in a frozen aqueous solution to avoid aggregation of cis GFP: loop:s11 at the high concentrations required to obtain Raman spectra (1 – 3mM), and 633 nm light, which is not absorbed by either form of truncated GFP, was used to obtain the Raman spectrum. EYQ1 is a GFP with the F64L, T203Y, and E222Q mutations that has been shown previously to undergo light-activated photoisomerization11. In EYQ1, the thermally stable isomerization state of the chromophore is the cis configuration, so with this truncated GFP the Raman spectrum of the light-activated form is expected to be similar to the Raman spectrum of EYQ1 prior to light activation. The starred changes are indeed consistent with changes observed previously in EYQ111, with the previously stated exception that the light-activated form in this case is the cis configuration of the chromophore (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Raman spectra obtained with 633 nm (pre-resonant) excitation of GFP: loop:s11 at 170K in pH 10 buffer before (trans GFP: loop:s11 in the model) and after light activation (photostationary mixture of trans and cis GFP: loop:s11 in the model, generated with 460 nm light). The starred peaks are consistent with the changes observed in EYQ1 previously except that light activation leads to generation of some chromophore in the cis configuration in this particular case (see text). At the pH these Raman spectra were obtained complete conversion of trans GFP: loop:s11 to cis GFP: loop:s11 is expected to take place (see Figure 8 and discussion), but since the solid was opaque, and the 633 nm light is expected to penetrate deeper into the solid, the spectrum most likely reflects a mixture of cis and trans GFP: loop:s11. The peaks growing in at 850 cm−1, 1260 cm−1, 1450 cm−1, and 1500 cm−1 as well as the decrease of the peak at 1150 cm−1 are consistent with model chromophore Raman spectra.

A pH dependence in absorbance spectra has been observed in several GFPs, and is often due to a simple titration from the protonated to the deprotonated phenol moiety of the chromophore8, but exceptions are known12. Typically the protonated state absorbs at approximately 400 nm and the deprotonated state absorbs at approximately 475 nm. The solid lines shown in Figure 8 are the absorbance spectra of cis GFP: loop:s11 derived from encasing GFP: loop:s11 in PVA and activating with light of various wavelengths. It appears that cis GFP: loop:s11 also has a titratable chromophore. Interestingly, at high pH the light-activated absorbance spectrum is the same when photoactivated at 435 nm and 460 nm. The ratio of extinction coefficients between the deprotonated cis GFP: loop:s11 (the pH 10 spectrum) and trans GFP: loop:s11 are very different at 435 nm and 460 nm, so according to equation (1) the ratios of concentrations are expected to change, unless the quantum yield of going from the deprotonated cis GFP: loop:s11 to trans GFP: loop:s11 is negligibly low. This leads us to suggest that the deprotonated cis GFP: loop:s11 has no appreciable rate of photoisomerization back to the trans form, thus when trans GFP: loop:s11 is light activated at pH 10, all of the trans GFP: loop:s11 is converted to cis GFP: loop:s11. Therefore the spectrum at pH 10 is the observed spectrum after light activation of trans GFP: loop:s11 to deprotonated cis GFP: loop:s11, and the spectrum of the protonated cis GFP: loop:s11 was determined by subtracting away the trans GFP: loop:s11 and deprotonated cis GFP: loop:s11 spectrum from lower pH light activated spectra. The quantum yields were measured to be 0.20 (φcis→trans of the protonated cis state) and 0.045 (φtrans→cis) and were obtained by measuring the kinetics of reaching the 460 nm photostationary state and fitting using supplementary equations S1 and S2 (see supplementary materials)13. The quantum yield φcis→trans of the deprotonated cis state is close to zero (see evaluation of the pH 10 data above).

Figure 8.

Absorbance spectra cis GFP: loop:s11 at multiple pHs. The absorbance spectra appear to change with pH similar to several titratable GFPs, leading us to assign the higher energy peak as the protonated form of the chromophore, and the lower energy band to the deprotonated form of the chromophore. The pH 10 spectrum is the same as the pH 10 PVA data in the supplementary materials because trans GFP: loop:s11 can be converted entirely to cis GFP: loop:s11 due to the quantum yield of going from deprotonated cis GFP: loop:s11 being negligible (see text). The pH 8, 8.6, and 9 data have the trans GFP: loop:s11 spectra subtracted out (see supplementary material for raw absorbance data).

Discussion

The observation that the light-activated spectra are independent of light intensity suggests that the light generates a photostationary state of the cis and trans forms of the chromophore. The photostationary states depend on the wavelength of activation light because the ratio of cis and trans concentrations depends on the product of the ratio of extinction coefficients and quantum yields of photoisomerization (equation (1)). The trans GFP: loop:s11 is ostensibly more stable in the dark because after light activation to form a photostationary mixture of trans and cis GFP: loop:s11, the absorbance spectrum shifts back to the original trans spectrum. The activation energy of 130 kJ/mol is significantly larger than model chromophore isomerization activation energies 50 kJ/mol (half life 3–5 minutes)14. The thermal isomerization half-lives of chromophores in GFPs and RFPs have been reported to be as fast 30 seconds15 and as slow as 14 hours15 with several examples in between16,17,18,19. The spread in activation energies is possibly due to the variable access of nucleophiles to the bridging methine group of the chromophore in the different protein structures20.

Photoisomerization from the cis to the trans configuration was initially considered because there are many reversibly photoswitchable GFPs21,22 and cis/trans isomerization of the chromophore has been shown to be their underlying mechanism in mTFP0.7, asFP595-A143S, Padron, and Dronpa by crystallography18,23,24,25, and in both EYQ1 and eqFP611 by pre-resonance Raman spectroscopy11,26. The Raman spectra shown in Figure 7 are not identical to Raman spectra of cis or trans model GFP chromophores obtained previously, but some of the changes are very similar to the changes observed upon converting trans model chromophore to cis model chromophore11. The two peaks at 1150 cm−1 that shift their relative proportions, the dramatic increase in intensity of the peaks at 850 cm−1, 1450 cm−1, and 1500 cm−1 are all predicted changes based on the Raman spectra of model chromophores. In the absence of a crystal structure of trans GFP: loop:s11, the similarity of the Raman data to structurally characterized systems leads us to describe the chromophore as cis or trans; however, there are likely to be subtle distortions from planarity of the chromophore due to constraints in the fold of both cis and trans GFP: loop:s11.

In both aqueous solution and in most GFP structures the chromophore is most stable in the cis configuration. We have shown that when strand 11 is removed and the resulting protein is re-folded the trans configuration of the chromophore is surprisingly more stable and the fluorescence quantum yield is quite high. The proposal that the trans configuration of the chromophore in truncated GFP is more stable and also has an appreciable quantum yield of fluorescence is uncommon, but not unprecedented27. Light activation to form a photostationary mixture of the trans and the more native cis form of the chromophore activates the truncated protein to rebind the removed strand of the β-barrel. All of these observations likely result from specific constraints in the folded structure of GFP: loop:s11, though in the absence of a three dimensional structure of trans GFP: loop:s11 we cannot be more specific. Lastly we have demonstrated that only the protonated from of cis GFP: loop:s11 has a light activated conversion pathway back to trans GFP: loop:s11. While the trans GFP: loop:s11 cannot currently be produced for in vivo protein interaction control due to the required in vitro processing, we note that this system is currently useful for forcing protein-protein interactions in ex vivo systems, such as on cell surfaces. Also note that photostationary states that are nearly all trans truncated GFP or mostly cis truncated GFP can be created depending on the wavelength of light, so one can target specific areas by judiciously using ‘activating’ and ‘deactivating’ light.

A few examples of light-driven association/dissociation of protein complexes have been reported including dissociation of enzymatically cleaved rhodopsin28, association of FKF1 (a protein with a LOV domain)29 and GIGANTEA complexes30, and reversible association and dissociation of phytochrome to PIF331. In all of these cases the light activated processes are driven by light activation of their external cofactors. The light-activated protein reassembly of split GFP described below is unusual in that it requires no external cofactors. This makes trans GFP: loop:s11 effectively a caged protein for reassembly that may offer novel approaches for imaging and protein interaction control32,33.

Methods and Materials

Preparation of GFP: loop:s11 and s11

Two native cysteines that were included in the original report of GFP:loop:s11 were removed in this work to avoid disulfide bond formation upon removing strand 11 (see supplementary materials for sequence). GFP:loop:s11 was expressed in a pET-15b vector in BL21(DE3) cells (Stratagene). The cells were induced with IPTG (0.25g/L) at OD 0.6 and then incubated for 4 hours at 37°C. The cells were spun down, resuspended in lysis buffer (50mM HEPES, 300mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol at pH 8), and lysed with a homogenizer. The cell lysate was spun down, and the supernatant poured onto a Ni:NTA column (Qiagen). The column was washed with the lysis buffer with 20mM imidazole and the proteins were eluted with the lysis buffer with 200mM imidazole. The proteins were then dialyzed into the anion exchange buffer (20mM Tris, 10mM NaCl at pH 8) and bound to an anion exchange column. The proteins were eluted by running a gradient from 10 mM NaCl to 200 mM NaCl with the buffer concentration and pH held constant in the anion exchange buffer. Liquid chromatography in tandem with electrospray mass spectrometry (Waters 2795 HPLC and ZQ single quadrupole MS) was used to check the purity and identity of the protein. Protein sequences inferred from DNA sequencing and verified by mass spectrometry are shown in the supplementary materials. Lyophilized trypsin (bovine pancreas trypsin, Sigma) used for digestions was weighed out and dissolved in 1 mM HCl immediately prior to use. 40 μM GFP:loop:s11 was digested with 100 units of trypsin per mL solution in trypsin buffer (50mM Tris, 20mM CaCl2, pH 8.0) for three hours, and subsequent anion exchange removed the trypsin and minor cleavage products. The cut protein was denatured in 6M guanidine hydrochloride, and size exclusion in lysis buffer plus 6M guanidine hydrochloride was performed to separate GFP: loop:s11 from s11. GFP: loop:s11 was refolded in lysis buffer overnight at room temperature by diluting from ~2mM denatured GFP: loop:s11 in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride to 40 μM GFP: loop:s11 in lysis buffer. The refolding process was observed by absorbance of the chromophore, and appears to be similar to the spectra observed in Figure 2, which suggest that the chromophore starts off in the cis configuration in denaturant and converts to the trans configuration upon refolding of the truncated protein. Size exclusion in lysis buffer removed leftover guanidine hydrochloride and some aggregated protein. Mass spectrometry and known trypsin cut sites were used to infer the protein sequence for trans GFP: loop:s11 shown in the supplementary materials. The peptide s11 was synthesized using Fmoc chemistry on a 431A Applied Biosystems Peptide Synthesizer, purified by HPLC (Shimadzu) and the mass and purity were verified by liquid chromatography in tandem with electrospray mass spectrometry (Waters 2795 HPLC and ZQ single quadrupole MS). All concentrations of proteins containing the GFP chromophore were obtained by denaturing the protein in 0.1M NaOH and comparing to the known extinction coefficient of the wild-type GFP chromophore at 448 nm (44100M−1cm−1)34.

Light Activation of GFP: loop:s11

Photostationary mixtures of cis and trans GFP: loop:s11 were generated by illuminating with 10mW of 460 nm laser light (unless specified otherwise) for two minutes in lysis buffer. The light used to generate the photostationary states was obtained from the frequency doubled output of a mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser (Tsunami Ti:S oscillator (Newport) pumped by a solid state Nd:YAG laser (Newport)). The samples were illuminated from above in standard 3mL quartz cuvettes while placed in a Perkin-Elmer absorbance spectrometer with stirring. To generate the data in Figure 2 and Figure 5, 5μM trans GFP: loop:s11 was illuminated as outlined above, then the lid was replaced on the spectrometer to block the laser light while absorbance spectra were taken for hours at either 18, 25, or 30°C. To generate the data shown in Figure 3, 5μM trans GFP: loop:s11 was illuminated as outlined above, the laser was blocked, 10μM s11 was spiked in, and then absorbance spectra were taken for hours. All absorbance spectra were only obtained every 20 seconds to avoid conversion of trans GFP: loop:s11 to cis GFP: loop:s11.

GFP: loop:s11 absorption spectra in polyvinylacrylamide (PVA)

trans GFP: loop:s11 in lysis buffer was diluted into 10% PVA (40,000 g/mol) with 300 mM NaCl in pH 8 (50mM HEPES), 8.6 (50mM HEPES), 9 (50mM bis-tris propane), and 10 (50mM sodium carbonate) buffer on glass coverslips with a 1 inch diameter rubber gasket to keep the liquid in place. The slides were left in the dark for 5 days to allow the PVA to dry and form films. Spectra in PVA were obtained in a Perkin Elmer spectrometer, and the photoactivated spectra were obtained by illuminating for approximately two minutes at variable angles with 10mW of light of various wavelengths. Additional illumination, or doubled intensity did not change the light activated spectra.

Raman Spectra

The Raman spectrum of trans GFP: loop:s11 shown in Figure 7 was obtained by exchanging the protein into pH 10 buffer (50 mM sodium carbonate and 300 mM sodium chloride), lowering the temperature to 170K using a Joule-Thomson refrigerator (MMR Technologies), and then taking the Raman spectrum using a reflection Raman spectrometer (LabRAM HR from Horiba Jobin Yvon) with a helium-neon laser light source (633 nm, which is to the red of any GFP absorption). The Raman spectrum of the mixture of cis and trans GFP: loop:s11 was obtained by illuminating the sample with a Xenon lamp directed through a 10 nm band pass filter centered at 460 nm (approximately 50mW) prior to taking the Raman spectrum. The sample was opaque because the buffer was frozen. No cryoprotectants were added because of the intense background Raman signals. Both Raman spectra were signal averaged for 30 minutes.

Fitting Procedure

The concentrations in Figures 5 and 6 were determined from fitting with the basis spectra in Figure 4. Matlab was used to solve A * X = B using standard linear algebra techniques, where A is the m by n matrix with all of the basis spectra, X is the n by o matrix of concentrations, and B is the m by o matrix of the data in Figures 2 and 3 (m is the number of absorbance measurements at different wavelengths, n is the number of species, and o is the number of time points). The kinetic fits were obtained from Berkeley Madonna by numerically solving the differential equations representing the models in Figure 2 and Figure 3, and minimizing the error between data points by altering the rate constants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Hongjie Dai and Scott Tabakman at Stanford for access to and assistance with their Raman Spectrometer, Professor Lubert Stryer for alerting us to reference 28, and Luke Oltrogge and Keunbong Do for many helpful discussions and comments. The fluorimeter used in these measurements was purchased with funds from NSF CHE-0639053. This research was supported in part by a grant from the NIH (GM27738).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Plot showing the wavelength dependence of photostationary states, description of quantum yield measurement, evidence for aggregation, absorbance spectra in PVA, quality of absorbance spectrum fits, and amino acid sequences.

References

- 1.Kent KP, Childs W, Boxer SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9664–9665. doi: 10.1021/ja803782x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakamoto S, Kudo K. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9574–9582. doi: 10.1021/ja802313a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang YM, Bystroff C. Biochemistry. 2009;48:929–940. doi: 10.1021/bi802027g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabantous S, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:102–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kent KP, Oltrogge LM, Boxer SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15988–15989. doi: 10.1021/ja906303f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niwa H, Inouye S, Hirano T, Matsuno T, Kojima S, Kubota M, Ohashi M, Tsuji FI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13617–13622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chattoraj M, King BA, Bublitz GU, Boxer SG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8362–8367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsien RY. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson AR, Maroney W. J Am Chem Soc. 1934;56:1320–1322. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrence MS, Phillips KJ, Liu DR. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10110–10112. doi: 10.1021/ja071641y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luin S, Voliani V, Lanza G, Bizzari R, Nifosi R, Amat P, Tozzini V, Serresi M, Beltram F. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:97–103. doi: 10.1021/ja804504b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Violot S, Carpentier P, Blanchoin L, Bourgeois D. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10356–10357. doi: 10.1021/ja903695n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lees AJ. Anal Chem. 1996;68:226–229. doi: 10.1021/ac9507653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He X, Bell AF, Tonge PJ. FEBS Letters. 2003;549:35–38. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stiel AC, Trowitzsch S, Weber G, Andresen M, Eggeling C, Hell SW, Jakobs S, Wahl MC. Biochem J. 2007;402:35–42. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bizzarri R, Serresi M, Cardarelli F, Abbruzzetti S, Campanini B, Viappiani C, Beltram F. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:85–95. doi: 10.1021/ja9014953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ando R, Flors C, Mizuno H, Hofkens J, Miyawaki A. Biophys J. 2007;92:L97–L99. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson JN, Ai H, Campbell RE, Remington SJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6672–6677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700059104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quillin ML, Anstrom DA, Shu XK, O’Leary S, Kallio K, Chudakov DA, Remington SJ. Biochem. 2005;44:5774–5787. doi: 10.1021/bi047644u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong J, Abulwerdi F, Baldridge A, Kowalik J, Solntsev KM, Tolbert LM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14096–14098. doi: 10.1021/ja803416h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukyanov KA, Chudakov DM, Lukyanov S, Verkhusha VV. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2005;6:885–891. doi: 10.1038/nrm1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Patterson G. Trends Cell Bio. 2009;19:555–565. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andresen M, Wahl MC, Stiel AC, Gräter F, Schäfer LV, Trowitsch S, Weber G, Eggeling C, Grubmüller H, Hell SW, Jakobs S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13070–13074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502772102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brakemann T, Weber G, Andresen M, Groenhof G, Stiel AC, Trowitzsch S, Eggeling C, Grubmüller H, Hell SW, Wahl SW, Wahl MC, Jakobs S. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14603–14609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.086314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andresen M, Stiel AC, Trowitzsch S, Weber G, Eggeling C, Wahl MC, Hell SW, Jakobs S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13005–13009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700629104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loos DC, Habuchi S, Flors C, Hotta J, Wiedenmann J, Nienhaus GU, Hofkens J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6270–6271. doi: 10.1021/ja0545113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen J, Wilmann PG, Beddoe T, Oakley AJ, Devenish RJ, Prescott M, Rossjohn J. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44626–44631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pober JS, Stryer L. J Mol Biol. 1975;95:477–481. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christie JM, Salomon M, Nozue K, Wada M, Briggs WR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8779–8783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawa M, Nusinow DA, Kay SA, Imaizumi T. Science. 2007;318:261–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1146994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni M, Tepperman JM, Quail PH. Nature. 1999;400:781–784. doi: 10.1038/23500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levskaya A, Weiner OD, Lim WA, Voigt CA. Nature. 2009;461:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature08446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yazawa M, Sadaghiani AM, Hsueh B, Dolmetsch RE. Nature Biotech. 2009;27:941–946. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deluca M, McElroy W. Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence. Academic Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.