Abstract

The tubules of the kidney display a remarkable capacity for self-renewal on damage. Whether this regeneration is mediated by dedifferentiating surviving cells or, as recently suggested, by stem cells has not been unequivocally settled. Herein, we demonstrate that aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity may be used for isolation of cells with progenitor characteristics from adult human renal cortical tissue. Gene expression profiling of the isolated ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cell fractions followed by immunohistochemical interrogation of renal tissues enabled us to delineate a tentative progenitor cell population scattered through the proximal tubules (PTs). These cells expressed CD24 and CD133, previously described markers for renal progenitors of Bowman's capsule. Furthermore, we show that the PT cells, and the glomerular progenitors, are positive for KRT7, KRT19, BCL2, and vimentin. In addition, tubular epithelium regenerating on acute tubular necrosis displayed long stretches of CD133+/VIM+ cells, further substantiating that these cells may represent a progenitor cell population. Furthermore, a potential association of these progenitor cells with papillary renal cell carcinoma was discovered. Taken together, our data demonstrate the presence of a previously unappreciated subset of the PT cells that may be endowed with a more robust phenotype, allowing increased resistance to acute renal injury, enabling rapid repopulation of the tubules.

See related Commentary on page 490

The nephron of the normal kidney is mitotically quiescent. However, the renal epithelium has a considerable capacity for tubular regeneration on acute renal injury (ARI). In contrast to regeneration of glomerular podocytes, which may emanate from progenitor cells among the parietal epithelial cells (PECs) of Bowman's capsule,1–3 the cellular origin of regenerating tubular cells is less clear. Tubular regeneration may be a stochastic process in which the least-injured cells dedifferentiate and repopulate the denuded basal membranes.4,5 This view has been challenged by the concept of renal and/or bone marrow–derived stem cells participating in the regenerative process.6 Recent data, however, indicate a minor role for the latter cell type,7,8 and the search for the defining features of adult tubular stem or progenitor cells has, to date, been inconclusive, with discrepant results regarding their proper histologic markers and their histologic location. It is, therefore, not surprising that little is known about potential links between putative kidney stem cells and the renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), which are malignancies that arise from the renal tubular epithelium. Renal cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 3% of adult malignancies globally, and the incidence is increasing.9 The major RCC types are clear cell, papillary (pRCC), chromophobe, collecting duct, and unclassified, whereas oncocytoma and cortical adenoma are examples of benign tumors.

The family of aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs) is thought to play a role in stem cell maintenance by converting retinal into retinoic acid.10 Accordingly, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) based on ALDH activity has successfully been used mainly for the isolation of hematopoietic stem cells but also for isolating breast cancer stem cells, intestinal mucosal stem cells, and liver cancer stem cells.11

In the present study, we isolated cells with elevated ALDH activity from human kidney cortex by means of FACS. By gene expression profiling of the isolated ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cell fractions and by subsequent immunohistochemical (IHC) interrogation of renal cortical tissues, we could delineate a tentative progenitor cell population with a scattered distribution in the epithelial layer of the proximal tubules (PTs). Functional and bioinformatics analyses indicated that these cells are endowed with a robust phenotype allowing increased resistance to ARI. This, together with an apparent immunophenotypical resemblance to stretches of cells seen in regenerating tubules, suggests that these cells may spearhead the repopulation of renal tubules after injury. The cells also displayed transcriptional similarities to those of pRCCs, a notion that was supported at the protein level using IHC analysis. Taken together, our data indicate that this previously unappreciated subset of the PT cells may be implicated in pathologic processes, including renal neoplasms and tubular regeneration after renal injury.

Materials and Methods

Procurement of Renal Tissue

Renal tissue samples were obtained from nephrectomies performed owing to malignancy or from renal biopsies performed using 18-gauge needles. All the specimens were collected after informed consent was obtained from the patients. Ethical permission was granted by the ethical committee at Lund University (LU680-08 and LU289-07).

IHC and Cytochemical Analyses

For IHC analysis, sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human renal tissue (4 μm thick) were deparaffinized using xylene followed by graded ethanols for rehydration according to the standard protocol. Boiling in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer at pH 6 was performed as antigen retrieval. Staining was detected using the EnVision system and DAKO Techmate 500 staining equipment according to the instructions of the manufacturer (DAKO, Carpenteria, CA). The chromogens used were diaminobenzidine (black/brown) and Permanent Red. For nuclear counterstaining, hematoxylin was used. As negative control, the primary antibody was omitted. Immunofluorescence (IF) was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded or fresh frozen material. For formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections, antigen retrieval was performed using Diva Decloaker solution (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA). Fresh frozen sections were fixed in cold acetone for 5 minutes. After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin in 10 mmol/L PBS, sections were incubated with primary antisera overnight at 8°C. After washing, secondary antibodies were applied according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by rinsing and mounting using DAPI–containing mountant. The sections were subsequently scanned by means of confocal imaging using the Zeiss LSM 710 system (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). The details of antibodies and dilutions are given in Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

Dissociation of Human Renal Tissue

The cortical tissue farthest from the tumor was selected and put in ice-cold Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The tissues were rinsed, minced, and subjected to overnight collagenase treatment at 37°C in a processing medium consisting of Ham's F-12/Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [1:1 (v/v); Invitrogen], supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, collagenase IV at a final concentration of 300 U/ml (Invitrogen), and deoxyribonuclease I type II at a final concentration of 200 U/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After trituration by slow repeated pipetting through a 10-ml pipette, the resulting tissue suspension was serially passed through tissue strainers with mesh sizes of 100 and 70 μm, respectively, thereby excluding glomeruli from the preparation. The suspension was treated with 1X trypsin–EDTA for 5 minutes and then was passed through a 20-μm strainer, which resulted in single cells. Finally, the cells were resuspended in ALDEFLUOR assay buffer (STEMCELL Technologies Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada) and were treated according to the ALDEFLUOR protocol described in the following subsection.

Separation of ALDEFLUOR-Positive Kidney Cells Using FACS

To isolate kidney cells with high ALDH enzymatic activity, the ALDEFLUOR kit (STEMCELL Technologies Inc.) was used. Briefly, cells obtained from freshly dissociated kidneys were suspended in ALDEFLUOR assay buffer containing the ALDH substrate BODIPY-aminoacetaldehyde at a concentration of 1.5 μmol/L per 1 × 106 cells, followed by incubation for 30 minutes at 37°C. The BODIPY-aminoacetaldehyde enters the cells via passive diffusion, and intracellular ALDH converts it into negatively charged BODIPY-aminoacetate, causing the cell to become fluorescent depending on the amount and activity of ALDH. As negative control, an aliquot of the cell suspension was allowed to react in the presence of the specific ALDH inhibitor diethylaminobenzaldehyde at a concentration of 15 μmol/L per 0.5 × 106 cells. To exclude nonviable cells from the FACS step, the cells were assayed for viability by exposure to 0.25 μg of 7-amino-actinomycin D (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) per 1 × 106 cells for 10 minutes before sorting, according to the protocol of the manufacturer. The cells were then subjected to FACS analysis using FACSAria I (BD Biosciences). Subsequent analyses were performed using FACS Diva version 6.1.1 software (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo v7.5.4 software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the QIAshredder and RNeasy mini kits (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations followed by DNase treatment. The cDNA synthesis was performed by using random primers and MultiScribe reverse transcriptase enzyme (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The amplifications were run using a GeneAmp 7300 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems) as previously described.12 Real-time detection of the PCR product was performed using the SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and all the reactions were performed in triplicate. Three housekeeping genes (UBC, YWHAZ, and SDHA) were used for normalization.13 The following primer sequences were used: UBC forward: 5′-ATTTGGGTCGCGGTTCTTG-3; UBC reverse: 5′-TGCCTTGACATTCTCGATGGT-3′; YWHAZ forward: 5′-ACTTTTGGTACATTGTGGCTTCAA-3′; YWHAZ reverse: 5′-CCGCCAGGAGGACAAACCAGTAT-3′; SDHA forward: 5′-TGGGAACAAGAGGGCCATCTG-3′; SDHA reverse: 5′-CCACCACTGCATCAAATTCATG-3′; CD133 forward: 5′-TGGATGCAGAACTTGACAACG T-3′; and CD133 reverse: 5′-ATACCTGCTACGACAGTCGTGGT-3′.

Attachment Independent Growth of FACS-Sorted Cells

To assess substrate-independent growth, the cells sorted based on ALDH activity were plated immediately after sorting, in triplicate, in ultra-low attachment plates. Single-cell suspensions were plated in 24-well ultra-low attachment plates (Corning Inc., Lowell, MA) at a density of 400, 1200, or 3600 cells per well in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 supplemented with B27, 20 ng/ml of epidermal growth factor, 40 ng/ml of fibroblast growth factor, and 100 U/ml of penicillin. The cells were observed for 21 days.

Sphere Culture of FACS-Sorted Cells in Matrigel Support

Single-cell suspensions were dissolved in 75% BD Matrigel Matrix Growth Factor Reduced (BD Biosciences) diluted in B27-supplemented Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 and seeded in 24-well Boyden chambers (Corning Inc) at a density of 1000, 5000, or 10,000 cells per well. The lower compartment of the chamber was supplemented with 500 μL of medium, and the Matrigel cell suspension was overlaid with 200 μL of medium to avoid dryness. The cells were observed for 21 days, and the medium was changed every third day.

Gene Expression Profiling

Total RNA from three pairs of ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cell fractions was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), followed by purification using the RNeasy micro kit (QIAGEN Inc.) and hybridization to HumanHT-12 v3.0 Expression BeadChips (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA) at the SCIBLU Genomics Centre at Lund University. Data management and normalization were performed using BioArray Software Environment (BASE).14 Raw intensity values representing mean bead pool intensity values for each probe were background corrected, negative intensities were capped to zero, followed by the addition of an intensity constant of 20 to all probe intensities. Data were normalized using a quantile normalization algorithm as implemented in BASE and subsequently log2 transformed. Probes were mapped to RefSeq Release 22 (NCBI Build 36.2) and UniGene Build 199. Only probes with an annotated gene symbol were used in further analyses. The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus database15 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through accession number GSE23911.

For gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA),16 probes were ranked according to the mean of the relative expression differences between each ALDHhigh and ALDHlow replicate pair. The preranked gene list tool in GSEA was applied using the c2 curated gene sets, the c3 transcription factor targets, and the c5 Gene Ontology (GO) gene set collections as supplied by the Molecular Signatures Database (http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/msigdb). Significance thresholds were calculated by 1000 permutations, and false discovery rate (FDR) q-values <0.05 were considered significant. Furthermore, a gene set specific for normal kidney cortex was applied in GSEA. This signature included the 100 most significant kidney cortex–specific reporters (FDR < 0.001, δ > 11.45) as determined by means of significance analysis of microarrays17 between 4 kidney cortex samples and 345 samples obtained from 64 other tissue sites in the Gene Expression Omnibus data set with accession number GSE3526.18 For the analyses of possible associations between ALDEFLUOR-sorted cells and pRCC, two additional gene sets were applied in GSEA. The first of these pRCC-specific signatures comprised the 100 most discriminatory reporters (FDR < 0.001, δ > 5.6) from a significance analysis of microarrays between 11 pRCCs and a series of 21 normal cortex, 32 clear cell, 12 oncocytoma, and 6 chromophobe tumor samples from a data set by Jones et al with Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GSE15641.19 The second gene set included genes with high relative expression in class 1 compared with class 2 pRCCs. Here, the 100 most discriminatory reporters (FDR < 0.001, δ > 5.77) were selected from a significance analysis of microarrays comparing 22 class 1 with 12 class 2 pRCCs in a gene expression data set published by Yang et al with Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GSE2748.20

Results

ALDH Activity–Based Isolation of Renal Cells with Stem Cell Characteristics

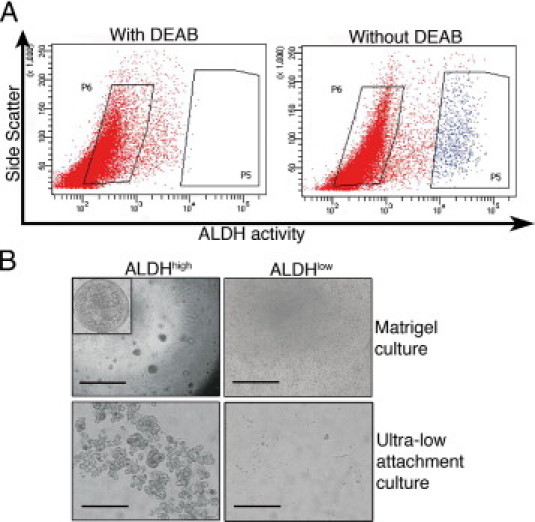

Single-cell suspensions of normal renal cortical tissue deprived of glomeruli were obtained by means of mechanical and enzymatic dissociation followed by sieving. We used the FACS-based ALDEFLUOR assay to assess and isolate cell populations with respect to cellular ALDH activity, enabling the definition of ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cell populations (Figure 1A). Cell suspensions from nine patients were analyzed, and the fraction of ALDHhigh cells constituted approximately 7% of the total number of viable cells. Consistent with the hypothesis that ALDH activity is associated with cells displaying progenitor cell characteristics, we observed a drastically increased colony-forming capacity in Matrigel of ALDHhigh cells compared with ALDHlow cells (Figure 1B). At a plating density of 5000 cells per well, the ALDHhigh cells resulted in a mean ± SD of 26 ± 6 hollow epithelial spheres per well, measuring a mean ± SD of 1.7 ± 0.4 mm, whereas the ALDHlow population possessed no sphere-forming capacity. The sorted cell fractions were also seeded in ultra-low attachment plates to assess the ability for anchorage-independent growth during nonadhesive conditions. The ALDHhigh cells survived and multiplied during the study, whereas the ALDHlow cells had no such capacity, indicating that these cells display low survival and growth capabilities after tissue dissociation (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Isolation of primary renal cortex cells based on ALDH activity. A: Representative FACS analysis of a single-cell suspension of normal renal cortical tissue incubated with fluorescent ALDH substrate. The left panel shows the cellular fluorescence in the presence of the ALDH inhibitor diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB), and the right panel shows the uninhibited reaction with the gate defining the ALDHhigh cells. The FACS gatings used are marked by boxes. In all the experiments, cells were first viability sorted by incubation in 7-amino-actinomycin D. B: The ALDHhigh population was enriched for cells with colony-forming capacity as assessed by plating in Matrigel culture (top row; scale bar = 1000 μm). Inset: A cellular sphere formed in the ALDHhigh culture at higher magnification (×40). The ALDHhigh population was also enriched for cells with the capacity to grow under ultra-low attachment conditions (bottom row; scale bar = 200 μm). The ALDHlow cells displayed none of these capacities.

Transcriptional Characterization of ALDEFLUOR-Sorted Cell Populations

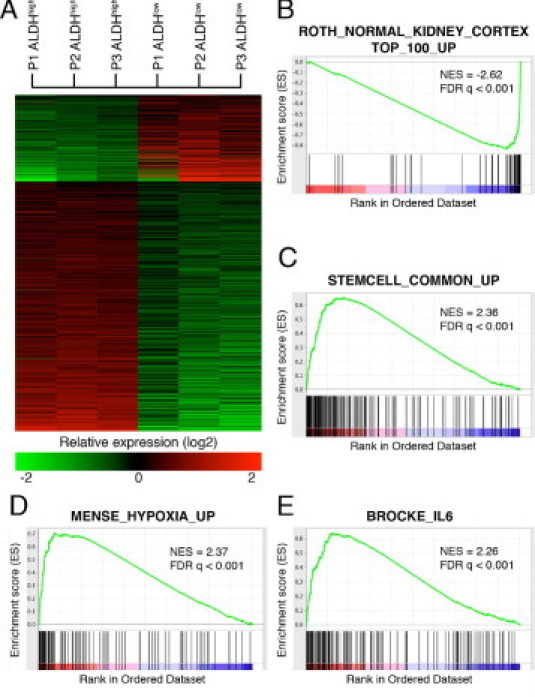

Both ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cell fractions were subjected to whole genome expression profiling. In total, 1445 probes showed a more than twofold difference between the ALDHhigh and its corresponding ALDHlow population in all three replicate pairs (Figure 2A and see Supplemental Table S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Of these, 1078 probes had high relative expression in the ALDHhigh population, and the remaining 367 probes showed high relative expression in ALDHlow cells. As expected, the expression levels of several ALDH genes were elevated in ALDHhigh cells, eg, ALDH1A3, ALDH1A2, and ALDH1B1.

Figure 2.

Gene expression profiling of three pairs of ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cell fractions. A: Gene expression heatmap illustrating the 1445 probes that showed a more than twofold difference between the ALDHhigh and its corresponding ALDHlow populations in all three replicate pairs. B–E: A GSEA of a gene list in which genes were ranked according to their relative expression difference in ALDHhigh compared with ALDHlow cells. Graphs display enrichment score (y axis) versus gene rank (x axis); genes with high relative expression in the ALDHhigh population are given a low rank order value (leftmost tail), and genes with high relative expression in ALDHlow cells are given a high rank order value (rightmost tail) of the gene rank representation. The rank of each gene in the respective gene set is indicated as a horizontal line below the enrichment plot. Normalized enrichment scores (NESs) and FDR q-values for each analysis are shown.

We next applied GSEA to obtain a functional description of the transcriptional differences between the ALDHhigh and ALDHlow populations. The GO terms significantly associated with the ALDHlow fraction were related to transmembrane transport, solute carrier functions, lysosomal activity, and hydrolytic and metabolic processes, features well in line with the primary function of renal tubular epithelium (see Supplemental Table S3A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The connection between the ALDHlow population and renal tubular cells was further substantiated in a GSEA using a gene signature specific for normal human kidney cortex (Figure 2B). For the ALDHhigh population, GO terms such as actin binding, intermediate filament cytoskeleton, focal adhesion, leading edge, and adherence junction were significantly enriched, indicating differences in cellular structure, adhesive potential, and migratory capacity between the two different cell populations. Furthermore, several ontology terms related to transcriptional activity were enriched. The GO term negative regulation of apoptosis (eg, BCL2L1, BCL2L2, and BAG3) was also significant, suggesting that the ALDHhigh population may be more resistant to apoptotic cues. From a GSEA using Molecular Signatures Database–curated gene sets, again, many gene sets were found to be significantly associated with the ALDHhigh signature, eg, a metasignature for stem cells, hypoxic response signatures, and several signatures associated with cellular stress, such as nuclear factor κB and interleukin-6 response gene signatures (Figure 2, C–E, and see Supplemental Table S3B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In addition, profiles associated with proliferative responses of RAS and MYC were significant. We next extended the GSEA to investigate whether binding sites for specific transcription factors were enriched in genes associated with the two separate ALDH fractions (see Supplemental Table S3C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Recognition sequences for HNF1 were the only gene sets significant for the ALDHlow population. HNF1A (TCF1) and HNF1B (TCF2) are transcription factors with key roles in differentiated renal tubule epithelia,21–23 thus further substantiating the tubular origin of the ALDHlow cell population and the validity of using this cell fraction as a reference for comparisons with the ALDHhigh fraction. For ALDHhigh-specific genes, significant enrichment of many more gene sets was observed. For example, binding sites for transcription factors such as AP1, FOXD3, ATF1-3, NFE2L2, YY1, and BACH1 were all significantly enriched.

Thus, based on the bioinformatics analyses, we conclude that ALDH-based sorting separates two cell populations from the renal cortex with divergent transcriptional profiles. Whereas the ALDHlow fraction displayed expression profiles associated with functions important for normal renal tubule epithelia, the ALDHhigh counterpart showed a much more complex transcriptional program, indicating a stem cell phenotype and resistance to apoptotic stimuli, possibly reflecting the higher plasticity and sturdiness of these potential progenitor cells.

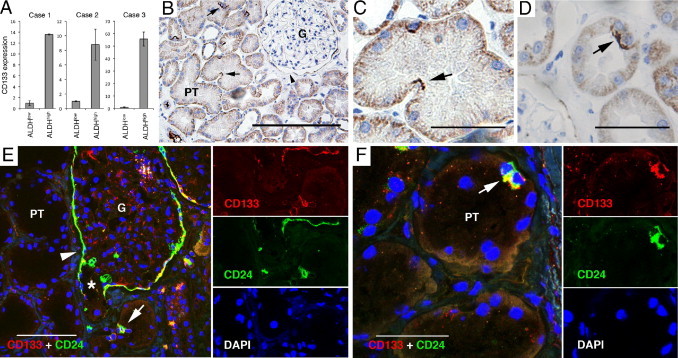

ALDH-Based Cell Sorting Identifies a Scattered Cell Population Within the PTs

Based on the gene expression profiling analyses, we performed an IHC interrogation to histologically map the isolated ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cells in renal tissue. One of the most up-regulated genes in the ALDHhigh population was CD133 (PROM1; see Supplemental Table S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The plasma membrane protein CD133 is a marker for renal progenitor cells of the parietal epithelial layer of Bowman's capsule.2,3 The elevated CD133 expression was confirmed by means of real-time quantitative PCR in an independent series of three ALDEFLUOR-sorted replicate pairs (Figure 3A). Importantly, IHC analysis not only detected CD133 positivity in Bowman's capsule but also identified scattered cells localized to the PTs that carried apical CD133 expression (Figure 3, B–D). The cells were often localized to the apices of creases formed by the convolution of the PTs (Figure 3C) and were frequently found in doublets (Figure 3D). Another gene highly expressed in the ALDHhigh cells was CD24. This gene has also been ascribed to the parietal progenitor cells of Bowman's capsule.2,3 Using IF, we established that CD24 expression co-localized to the CD133-expressing cells of the PTs and Bowman's capsule (Figure 3, E and F).

Figure 3.

CD133 and CD24 expression in renal tissue. A: Quantitative PCR measuring mean relative expression of CD133 mRNA in three paired ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cell fractions. Error bars represent SD. n = 3. B–D: The IHC analyses of CD133 protein expression in renal tissue revealed apical CD133 staining (black) in occasional PT cells (arrows) and in cells of the parietal layer of Bowman's capsule (arrowhead in B). Diffuse basolateral positivity was noted in all the tubular cells. The cells were often found in tubular curvatures (C) and sometimes in doublets (D). E and F: Staining with IF demonstrating co-expression of CD133 (red) and CD24 (green). Separate images of the respective fluorochrome channels are shown to the right of the merged images. E: Co-expression of CD24 and CD133 was seen in the parietal cells of Bowman's capsule (arrowhead), which extended down to the urinary pole (star), and in scattered cells of the PTs (arrow). F: A characteristic cell doublet positive for CD24 and CD133 (arrow). G, glomerulus. Scale bars = 200 μm (B and E); 50 μm (C, D, and F).

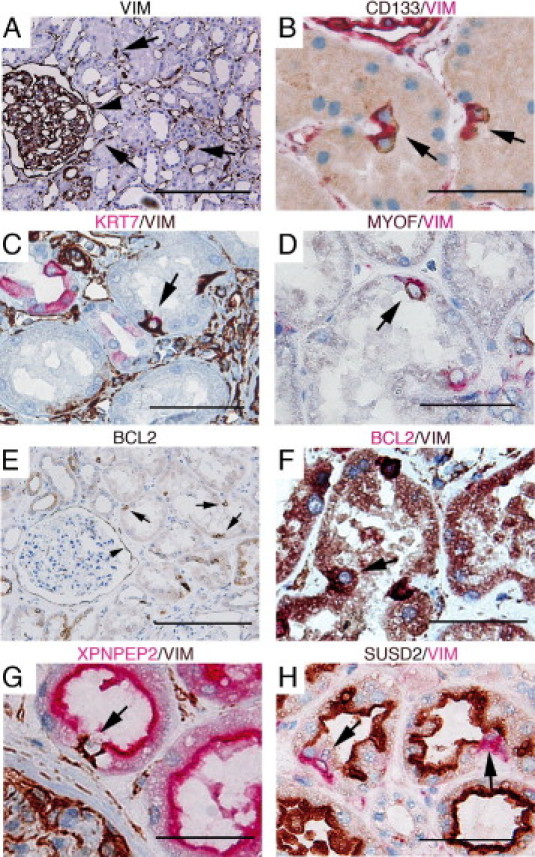

The gene expression profiling analysis further suggested that the ALDHhigh population also could be defined by the expression of a variety of intermediate filaments, such as vimentin (VIM) and cytokeratins 7 and 19 (KRT7 and KRT19), none of which are recognized to be expressed by the bulk of epithelial cells in the PTs. The IHC analysis of vimentin revealed basal positivity in scattered cells of the PTs, frequently seen in doublets and often at the apices of tubular creases and in the parietal layer of Bowman's capsule, ie, analogous to the staining patterns of CD133 and CD24 (Figure 4A). Co-localization staining validated that the vimentin-positive cells also expressed CD133 (Figure 4B). Using this costaining approach, we also demonstrated that the vimentin-positive cells express KRT7 (Figure 4C) and KRT19 (see Supplemental Figure S1A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). One of the most differentially expressed genes in the ALDHhigh fraction was MYOF (FER1L3), coding for a transmembrane protein believed to be involved in membrane regeneration and repair.24 In line with the findings previously herein, MYOF specifically costained the scattered vimentin-positive cells (Figure 4D). KRT7, KRT19, and MYOF expression was also seen in the PECs of Bowman's capsule (see Supplemental Figure S1, B–D, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), further highlighting the similarity between the PEC progenitor cell population and the scattered PT cells observed in the present study.

Figure 4.

The IHC interrogation of genes characteristic of ALDHhigh and ALDHlow cells in renal tissue. A–F: Protein expression of genes specific for ALDHhigh cells was found in scattered cells of the PTs (arrows) and in the PECs of Bowman's capsule (arrowheads in A and E). A: Positive staining of vimentin (VIM) was seen in interstitial cells and podocytes as expected but also in rare PT cells. B–D: Vimentin co-localization with CD133 (B), KRT7 (C), and MYOF (D). KRT7 positivity was also seen in the principal cells of cortical collecting ducts and to a lesser degree in distal tubules; however, these cells were negative for vimentin (C). BCL2 expression (E) was also found to co-localize with vimentin (F). Expression of the ALDHlow-specific genes XPNPEP2 (G) and SUSD2 (H) exclusively stained bulk epithelial cells of the PTs but not the vimentin-positive cells (arrows). The colors of the respective chromogens are given above the images. Scale bars = 200 μm (A); 50 μm (B–H).

The bioinformatics analyses further indicated that the ALDHhigh cells are characterized by a more robust phenotype with increased protection from apoptosis. The IHC analysis of BCL2, a key suppressor of apoptosis, detected cytoplasmic expression in scattered cells of the PTs and in the PECs of Bowman's capsule (Figure 4E). The BCL2 positivity also proved to co-localize with vimentin positivity (Figure 4F).

We next investigated protein expression of transcripts specific for the ALDHlow fraction. Two of the most discriminatory genes for this fraction, XPNPEP2 and SUSD2, stained exclusively the PT cells of the nephron. The scattered vimentin-positive cells were negative for these markers, thus adding support to the suggested cellular heterogeneity in the epithelial layer of the PTs (Figure 4, G and H). Furthermore, HNF1, which was implicated as a central transcription factor for ALDHlow-specific genes in the GSEA, showed a similar staining pattern, ie, positive staining for bulk cells in the PTs and absence of staining in the vimentin-expressing cells (see Supplemental Figure S1E at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

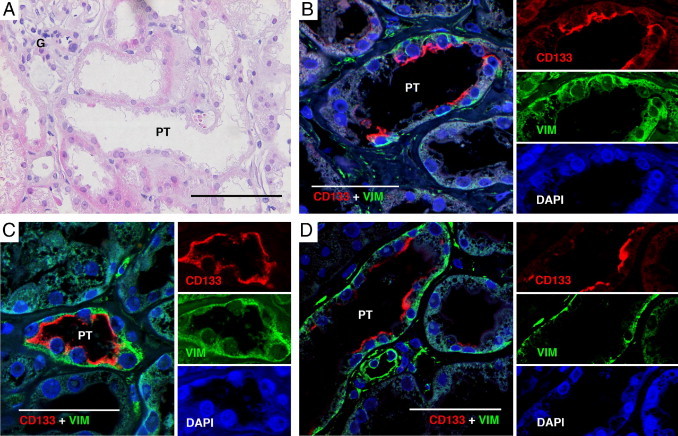

Distribution of VIM+/CD133+ Cells During Tubular Regeneration

To evaluate the status of the potential renal progenitor cell during tubular regeneration, renal biopsy cases demonstrating signs of acute tubular necrosis in restitution were identified by a renal pathologist (M.E.J.). Light microscopic signs of tubular regeneration were focally present, such as nuclear prominence, flattening of tubular cells, and scattered mitoses. Concomitant signs of recent acute tubular necrosis were also seen, such as luminal sloughing of tubular epithelial cells and apical plasma membranes alongside with nonisometric vacuolization of the cytoplasm (Figure 5A). We performed IF for CD133 and vimentin in tissue sections from these cases (Figure 5, B–D). In regions of tubular regeneration, stretches of cells bearing apical CD133 positivity and basal vimentin staining were seen, occasionally spanning the whole circumference of the tubule except for necrotic cells (Figure 5B), an observation indicating that the rare PT cells may be activated during tubular regeneration.

Figure 5.

CD133 and vimentin expression during tubular regeneration. A: H&E slide demonstrating a representative tubular region bearing the cardinal signs of tubular regeneration (nuclear enlargement, flattening of epithelial cells, and reduction of epithelial height). B–D: Staining with IF of CD133 and vimentin. Co-expression of CD133 and vimentin was detected in long stretches of epithelial cells, sometimes even spanning the whole tubular circumference. Separate images of the respective fluorochrome channels are shown to the right of the merged images. G, glomerulus. Scale bars = 200 μm (A); 50 μm (B–D).

Association between ALDHhigh Cells and Renal Malignancies

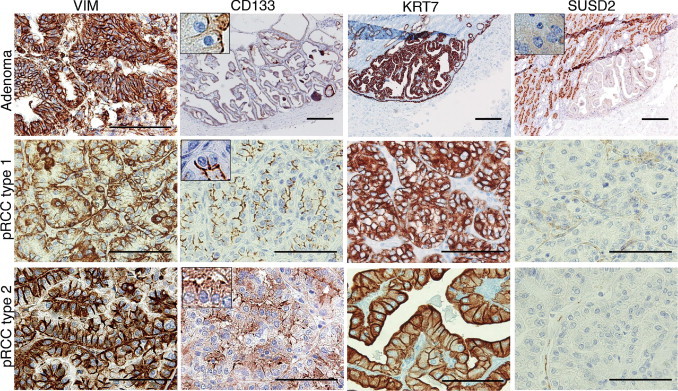

One unique characteristic of the ALDHhigh population was the concomitant expression of VIM, KRT7, and KRT19. In a pattern distinct from all other RCC subtypes, the combined expression of these three markers is characteristic of pRCC.25,26 We, therefore, explored the possibility that pRCC may arise through malignant conversion of the ALDHhigh cells. As a first step, pRCC-derived gene signatures from two public data sets were applied in a GSEA. A substantial overlap was noted between the expression profile of ALDHhigh cells and pRCCs, and in particular type 1 pRCC (see Supplemental Figure S2, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). To further substantiate this connection, we performed IHC analyses of 10 cases of pRCC (six type 1 and four type 2) and 4 cases of cortical adenomata because these benign renal neoplasms are suggested to be precursor lesions of pRCC.27 Positive staining for KRT7, KRT19, and CD133 was observed in all cases of cortical adenomata, a pattern that was mirrored throughout nearly all of the analyzed cases of pRCC (Figure 6 and Table 1, and see Supplemental Figure S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Conversely, SUSD2, which was specifically expressed in bulk epithelial cells of the PTs (Figure 4H), stained negatively in all these neoplastic lesions (Figure 6 and Table 1). Together, these results indicate a potential origin of adenomas and pRCCs from the scattered CD133+/VIM+ cells found in the PTs.

Figure 6.

Protein expression of ALDHhigh- and ALDHlow-specific genes in cortical adenomas and pRCCs. In adenomas and type 1 and 2 pRCCs, a consistent VIM/CD133/KRT7 positivity was observed, whereas SUSD2 staining was negative. To facilitate interpretation of the apical CD133 and SUSD2 staining patterns, insets of higher magnification are added at ×500 magnification. Scale bars = 200 μm (all adenoma images); 100 μm (vimentin staining of adenoma and all pRCC type 1 and type 2 images).

Table.

IHC Analysis of Markers Specific for ALDHhigh and ALDHlow Cells in Renal Neoplasms

| Tissue (n) | VIM | CD133 | KRT7 | KRT19 | SUSD2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical adenoma (4) | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 0/4 |

| pRCC type 1 (6) | 6/6 | 5/6 | 6/6 | 6/6 | 0/6 |

| pRCC type 2 (4) | 4/4 | 3/4 | 3/4 | 4/4 | 0/4 |

For each marker, the number of positively staining neoplasms per total number of investigated cases is indicated.

Discussion

Two decades ago, Moll et al reported that the human kidney holds occasional cells in the epithelial layer of the PTs that express VIM, KRT7, and KRT19.28 This important observation has, to our knowledge, been greatly overlooked in the recent literature, despite the fact that the cells responsible for reepithelization on ARI express vimentin.29 Herein, we show that ALDH activity may be used to isolate cells with progenitor-like characteristics from the tubular fraction of the renal cortex. We provide substantial evidence identifying the ALDHhigh cells as the vimentin/KRT7/KRT19-positive cell population of the PTs. We could also delineate an expanded set of markers that distinguish these sparsely distributed PT cells from their surrounding bulk epithelial counterparts. Functionally, we show that the ALDHhigh cells display sphere formation and anchorage-independent growth, two classic stem cell properties. Our data provide arguments that the vimentin-positive cells observed during tubular regeneration are derivatives of preprogrammed resident progenitor cells, inconspicuously blending with bulk epithelial cells of the PTs.

The scattered PT cells were characterized by elevated levels of CD133, a marker that has been used for isolation and propagation of progenitor cells from human and murine renal tissues.6 Studies using glomerular preparations from human renal tissue have identified pluripotent CD133+/CD24+ cells residing in Bowman's capsule that were capable of podocyte and tubular differentiation in vitro and of integration into renal tubules when injected into SCID mice with induced acute tubular necrosis.2,3 The existence of a progenitor cell population in Bowman's capsule has been further strengthened by lineage tracing studies in mice, where podocytes were shown to be replenished from PECs.1 Hence, accumulating data suggest that the parietal epithelium in Bowman's capsule holds progenitor cells that can replenish podocytes and, potentially, tubular epithelial cells.

Two studies have used cortical tissue deprived of glomeruli for isolation of progenitor cells.30,31 These studies are, however, highly discrepant regarding the histoanatomical localization of their isolated CD133+ fraction. Bussolati et al identified occasional CD133+ cells restricted to the renal interstitium, whereas in the study by Sallustio et al, cytoplasmic and membrane-associated CD133 positivity was detected in most tubular cells and in most tubular profiles. The distinct apical CD133 staining pattern of scattered tubular cells reported herein thus stands in stark contrast to these previous studies. Moreover, we did not detect any CD133+ cells in the renal interstitium. These apparently conflicting results may be related to the specificity of the applied antibodies and their capacity to recognize glycosylated forms of CD133, as previously reported.32 The validity of our CD133 staining pattern to define a distinct cell population was strongly supported by our costaining experiments.

The ALDHhigh cells were also characterized by a transcriptional profile associated with negative regulation of apoptosis, a finding that was corroborated by the IHC staining of BCL2. Knockout experiments in mice have shown that BCL2 is crucial for tubule development and for repair after renal injury.33,34 It has also been shown that renal cells expressing high levels of BCL2 are protected against mitochondrial injury and fragmentation after ARI,33,35 lending further experimental support to the possible protective role of BCL2 for the scattered progenitor cells on kidney damage.

Moreover, the expression pattern of the ALDHhigh fraction showed a strong correlation to a previously published metasignature derived from embryonal, neuronal, and hematopoietic stem cells.36 Although the ALDHhigh fraction most likely represents a relatively differentiated cell type with distinct PT-associated characteristics, certain traits associated with a stem/progenitor cell phenotype are thus retained. Furthermore, it is generally believed that stem or progenitor cells residing in adult organs are remnants deposited from the founding embryonic progenitor cells of the organ in question.37 Several of the characteristic markers for the cells described in this study, such as CD24, CD133, VIM, KRT19, and BCL2, are also expressed in the metanephric mesenchyme during nephrogenesis.28,34,38 A possible interpretation of these observations is that a subset of nephrogenic progenitor cells persists in the adult renal tubular epithelium. Because the scattered PT cells show substantial immunophenotypical similarity to the PEC progenitors, we hypothesize that they may represent a local PT-specific repository of remnant nephrogenic progenitor cells, analogous to the model that has been proposed for the PEC progenitors of Bowman's capsule.39

To provide some initial data concerning the in vivo function of the VIM+/CD133+ cells, we chose to study renal tissue from patients with a clinical and pathologic diagnosis of acute tubular necrosis in restitution. Prominent regeneration was seen mainly in the PTs. In contrast to the staining pattern of histologically normal PTs, long rows of VIM+/CD133+ cells were seen in tubules of regenerating kidneys. We interpret this phenomenon as cells expanding from a tubular progenitor cell population, possibly in the form of a transit amplifying population. On completion of basal membrane coverage, the cells repolarize and lose their VIM+/CD133+ profile, except for the remaining scattered progenitor cells still expressing vimentin and CD133.

The cell of origin for pRCC has not been unequivocally determined. In the present analysis, we demonstrate a significant transcriptional similarity between the putative PT progenitor cell and pRCCs. This similarity was further corroborated at the protein level using IHC analysis, wherein pRCCs stained positive for a set of markers characteristic of the progenitor cell population, whereas staining was negative for SUSD2, a marker for bulk epithelial cells. An identical immunoprofile was obtained for cortical adenomas, a tentative precursor lesion of pRCC. Thus, our study provides initial data suggesting that pRCC develops from these progenitor cells and that cortical adenomas may represent a benign intermediate step during this oncogenic process. This would also explain the enigmatic co-expression of vimentin and cytokeratins seen in pRCC, which is uncommon in carcinomas.

The functional and transcriptional characteristics of the ALDHhigh cells and the immunophenotypical similarity to regenerating tubules strongly argue for a PT-specific cell type endowed with an enhanced capacity to withstand renal injury and, if injury occurs, take the lead in reestablishment of the tubular epithelium. The rapid kinetics of clinically significant ARI is such that swift repopulation of the renal tubules is an absolute requirement to prevent uremia followed by death of the organism. We believe that the time factor makes deployment of renal stem or progenitor cells responsible for regeneration elsewhere, as in the papillae40 or interstitium,30 biologically inconceivable. Renal tubular function depends on strict polarization, an absolute prerequisite for vectorial transport against steep electroosmotic gradients.41 Therefore, the morphologic features of tubular progenitor cells should be expected to be similar to those of adjacent differentiated cells with junctional complexes and adherence and tight junctions, blending imperceptibly with the adjacent cells so as not to short-circuit the electrochemical electrolyte gradient, the foundation of vectorial transport. Further study of renal progenitor cells during various acute and chronic renal diseases, such as nephrosclerosis, glomerulonephritis, diabetic nephropathy, and renal transplantation, most probably holds several keys to the understanding of these important diseases.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from SUS Malmö ALF funding, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Crafoord Foundation, Gunnar Nilsson's Cancer Foundation, the National Association for Kidney Diseases, the Malmö University Hospital Research Fund, Ollie and Elof Ericsson's Foundation, and the Swedish Society for Medical Research.

H.A. and M.E.J. contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org and at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.10.026.

Supplementary data

Expression of KRT7, KRT19, MYOF, and HNF1A in renal tissue. A: Protein expression of the ALDHhigh cell–specific marker KRT19 was found in scattered cells of the PTs (arrow). Apart from in scattered PT cells, expression of KRT7 (B), KRT19 (C), and MYOF (D) was also seen by the parietal cells of Bowman's capsule (arrowheads). E:HNF1 was abundantly expressed in the PT cells in a pattern that did not co-localize with vimentin (arrow). The colors of the respective chromogens are given above the images. Scale bars: 50 mm (A and E); 100 mm (B-D).

A GSEA demonstrating a significant association between the transcriptional profile of ALDHhigh cells and pRCC. The GSEA and the ranking of genes were performed as in Figure 2. A: The GSEA using a gene set consisting of the 100 most up-regulated genes in pRCC compared with a set of normal cortex samples and various other renal neoplasms. B: The GSEA using a gene set representing the 100 most up-regulated genes in type 1 pRCC compared with type 2 pRCC. Normalized enrichment scores (NESs) and FDR q-values for each analysis are shown.

Expression of KRT19 in cortical adenomata and pRCC. In adenomas and type 1 and 2 pRCCs, a consistent KRT19 positivity was observed, whereas SUSD2 staining was negative. Scale bars: 200 mm (adenoma); 100 mm (pRCCs).

List of antibodies.

A total of 1445 probes with a more than twofold difference in expression between the ALDHhigh and ALDHlow fractions in all three replicate pairs. The first four columns (Reported Id, Gene.Symbol, Accession, and Locus Link) provide gene-centered information for each Illumina probe according to RefSeq Release 22 (NCBI Build 36.2) and UniGene Build 199. The following three columns (R_001_N, R_002_N, and R_003_N) represent gene expression data obtained from three paired ALDHhigh/ALDHlow cell fractions provided as the ALDHhigh expression relative to the expression of its corresponding ALDHlow fraction value on a log2 base. In the last column (log2 mean.diff), the mean of these log2 ALDHhigh/ALDHlow expression differences is supplied.

Results of GSEA for whole genome expression profiling data comparing ALDHhigh with ALDHlow cell fractions. Significance thresholds were calculated by 1000 permutations, and all gene sets with FDR q-values < 0.05 are listed. Gene sets with positive normalized enrichment scores (NESs) are associated with the ALDHhigh phenotype, whereas gene sets with negative NESs show association with the ALDHlow phenotype. The GSEA applying the c5 GO gene set collection (A), the c2 curated gene sets (B), and the c3 transcription factor target gene set collection (C).

References

- 1.Appel D., Kershaw D.B., Smeets B., Yuan G., Fuss A., Frye B., Elger M., Kriz W., Floege J., Moeller M.J. Recruitment of podocytes from glomerular parietal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:333–343. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronconi E., Sagrinati C., Angelotti M.L., Lazzeri E., Mazzinghi B., Ballerini L., Parente E., Becherucci F., Gacci M., Carini M., Maggi E., Serio M., Vannelli G.B., Lasagni L., Romagnani S., Romagnani P. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:322–332. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sagrinati C., Netti G.S., Mazzinghi B., Lazzeri E., Liotta F., Frosali F., Ronconi E., Meini C., Gacci M., Squecco R., Carini M., Gesualdo L., Francini F., Maggi E., Annunziato F., Lasagni L., Serio M., Romagnani S., Romagnani P. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman's capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2443–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogetseder A., Palan T., Bacic D., Kaissling B., Le Hir M. Proximal tubular epithelial cells are generated by division of differentiated cells in the healthy kidney. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C807–C813. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00301.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogetseder A., Picard N., Gaspert A., Walch M., Kaissling B., Le Hir M. Proliferation capacity of the renal proximal tubule involves the bulk of differentiated epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C22–C28. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00227.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benigni A., Morigi M., Remuzzi G. Kidney regeneration. Lancet. 2010;375:1310–1317. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffield J.S., Park K.M., Hsiao L.L., Kelley V.R., Scadden D.T., Ichimura T., Bonventre J.V. Restoration of tubular epithelial cells during repair of the postischemic kidney occurs independently of bone marrow-derived stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1743–1755. doi: 10.1172/JCI22593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphreys B.D., Valerius M.T., Kobayashi A., Mugford J.W., Soeung S., Duffield J.S., McMahon A.P., Bonventre J.V. Intrinsic epithelial cells repair the kidney after injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson E.C., Evans C.P., Lara P.N., Jr Renal cell carcinoma: current status and emerging therapies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chute J.P., Muramoto G.G., Whitesides J., Colvin M., Safi R., Chao N.J., McDonnell D.P. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase and retinoid signaling induces the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11707–11712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603806103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douville J., Beaulieu R., Balicki D. ALDH1 as a functional marker of cancer stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:17–25. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjolund J., Johansson M., Manna S., Norin C., Pietras A., Beckman S., Nilsson E., Ljungberg B., Axelson H. Suppression of renal cell carcinoma growth by inhibition of Notch signaling in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:217–228. doi: 10.1172/JCI32086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Preter K., Speleman F., Combaret V., Lunec J., Laureys G., Eussen B.H., Francotte N., Board J., Pearson A.D., De Paepe A., Van Roy N., Vandesompele J. Quantification of MYCN, DDX1, and NAG gene copy number in neuroblastoma using a real-time quantitative PCR assay. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:159–166. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallon-Christersson J., Nordborg N., Svensson M., Hakkinen J. BASE: 2nd generation software for microarray data management and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:330. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A.E. Gene Expression Omnibus: nCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., Mesirov J.P. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tusher V.G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth R.B., Hevezi P., Lee J., Willhite D., Lechner S.M., Foster A.C., Zlotnik A. Gene expression analyses reveal molecular relationships among 20 regions of the human CNS. Neurogenetics. 2006;7:67–80. doi: 10.1007/s10048-006-0032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones J., Otu H., Spentzos D., Kolia S., Inan M., Beecken W.D., Fellbaum C., Gu X., Joseph M., Pantuck A.J., Jonas D., Libermann T.A. Gene signatures of progression and metastasis in renal cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5730–5739. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X.J., Tan M.H., Kim H.L., Ditlev J.A., Betten M.W., Png C.E., Kort E.J., Futami K., Furge K.A., Takahashi M., Kanayama H.O., Tan P.H., Teh B.S., Luan C., Wang K., Pins M., Tretiakova M., Anema J., Kahnoski R., Nicol T., Stadler W., Vogelzang N.G., Amato R., Seligson D., Figlin R., Belldegrun A., Rogers C.G., Teh B.T. A molecular classification of papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5628–5637. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maher J.M., Slitt A.L., Callaghan T.N., Cheng X., Cheung C., Gonzalez F.J., Klaassen C.D. Alterations in transporter expression in liver, kidney, and duodenum after targeted disruption of the transcription factor HNF1α. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:512–522. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pontoglio M., Barra J., Hadchouel M., Doyen A., Kress C., Bach J.P., Babinet C., Yaniv M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 inactivation results in hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, and renal Fanconi syndrome. Cell. 1996;84:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saji T., Kikuchi R., Kusuhara H., Kim I., Gonzalez F.J., Sugiyama Y. Transcriptional regulation of human and mouse organic anion transporter 1 by hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 α/β. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:784–790. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.128249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernatchez P.N., Sharma A., Kodaman P., Sessa W.C. Myoferlin is critical for endocytosis in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C484–C492. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00498.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langner C., Wegscheider B.J., Ratschek M., Schips L., Zigeuner R. Keratin immunohistochemistry in renal cell carcinoma subtypes and renal oncocytomas: a systematic analysis of 233 tumors. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0948-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skinnider B.F., Folpe A.L., Hennigar R.A., Lim S.D., Cohen C., Tamboli P., Young A., de Peralta-Venturina M., Amin M.B. Distribution of cytokeratins and vimentin in adult renal neoplasms and normal renal tissue: potential utility of a cytokeratin antibody panel in the differential diagnosis of renal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:747–754. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000163362.78475.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang K.L., Weinrach D.M., Luan C., Han M., Lin F., Teh B.T., Yang X.J. Renal papillary adenoma: a putative precursor of papillary renal cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moll R., Hage C., Thoenes W. Expression of intermediate filament proteins in fetal and adult human kidney: modulations of intermediate filament patterns during development and in damaged tissue. Lab Invest. 1991;65:74–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grone H.J., Weber K., Grone E., Helmchen U., Osborn M. Coexpression of keratin and vimentin in damaged and regenerating tubular epithelia of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 1987;129:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bussolati B., Bruno S., Grange C., Buttiglieri S., Deregibus M.C., Cantino D., Camussi G. Isolation of renal progenitor cells from adult human kidney. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:545–555. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sallustio F., De Benedictis L., Castellano G., Zaza G., Loverre A., Costantino V., Grandaliano G., Schena F.P. TLR2 plays a role in the activation of human resident renal stem/progenitor cells. FASEB J. 2010;24:514–525. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karbanova J., Missol-Kolka E., Fonseca A.V., Lorra C., Janich P., Hollerova H., Jaszai J., Ehrmann J., Kolar Z., Liebers C., Arl S., Subrtova D., Freund D., Mokry J., Huttner W.B., Corbeil D. The stem cell marker CD133 (Prominin-1) is expressed in various human glandular epithelia. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:977–993. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brooks C., Wei Q., Cho S.G., Dong Z. Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1275–1285. doi: 10.1172/JCI37829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veis D.J., Sorenson C.M., Shutter J.R., Korsmeyer S.J. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell. 1993;75:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks C., Wang J., Yang T., Dong Z. Characterization of cell clones isolated from hypoxia-selected renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F243–F252. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00236.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramalho-Santos M., Yoon S., Matsuzaki Y., Mulligan R.C., Melton D.A. “Stemness”: transcriptional profiling of embryonic and adult stem cells. Science. 2002;298:597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1072530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Temple S. The development of neural stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:112–117. doi: 10.1038/35102174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivanova L., Hiatt M.J., Yoder M.C., Tarantal A.F., Matsell D.G. Ontogeny of CD24 in the human kidney. Kidney Int. 2010;77:1123–1131. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romagnani P. Toward the identification of a “renopoietic system”? Stem Cells. 2009;27:2247–2253. doi: 10.1002/stem.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oliver J.A., Maarouf O., Cheema F.H., Martens T.P., Al-Awqati Q. The renal papilla is a niche for adult kidney stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:795–804. doi: 10.1172/JCI20921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson W.J. Adaptation of core mechanisms to generate cell polarity. Nature. 2003;422:766–774. doi: 10.1038/nature01602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression of KRT7, KRT19, MYOF, and HNF1A in renal tissue. A: Protein expression of the ALDHhigh cell–specific marker KRT19 was found in scattered cells of the PTs (arrow). Apart from in scattered PT cells, expression of KRT7 (B), KRT19 (C), and MYOF (D) was also seen by the parietal cells of Bowman's capsule (arrowheads). E:HNF1 was abundantly expressed in the PT cells in a pattern that did not co-localize with vimentin (arrow). The colors of the respective chromogens are given above the images. Scale bars: 50 mm (A and E); 100 mm (B-D).

A GSEA demonstrating a significant association between the transcriptional profile of ALDHhigh cells and pRCC. The GSEA and the ranking of genes were performed as in Figure 2. A: The GSEA using a gene set consisting of the 100 most up-regulated genes in pRCC compared with a set of normal cortex samples and various other renal neoplasms. B: The GSEA using a gene set representing the 100 most up-regulated genes in type 1 pRCC compared with type 2 pRCC. Normalized enrichment scores (NESs) and FDR q-values for each analysis are shown.

Expression of KRT19 in cortical adenomata and pRCC. In adenomas and type 1 and 2 pRCCs, a consistent KRT19 positivity was observed, whereas SUSD2 staining was negative. Scale bars: 200 mm (adenoma); 100 mm (pRCCs).

List of antibodies.

A total of 1445 probes with a more than twofold difference in expression between the ALDHhigh and ALDHlow fractions in all three replicate pairs. The first four columns (Reported Id, Gene.Symbol, Accession, and Locus Link) provide gene-centered information for each Illumina probe according to RefSeq Release 22 (NCBI Build 36.2) and UniGene Build 199. The following three columns (R_001_N, R_002_N, and R_003_N) represent gene expression data obtained from three paired ALDHhigh/ALDHlow cell fractions provided as the ALDHhigh expression relative to the expression of its corresponding ALDHlow fraction value on a log2 base. In the last column (log2 mean.diff), the mean of these log2 ALDHhigh/ALDHlow expression differences is supplied.

Results of GSEA for whole genome expression profiling data comparing ALDHhigh with ALDHlow cell fractions. Significance thresholds were calculated by 1000 permutations, and all gene sets with FDR q-values < 0.05 are listed. Gene sets with positive normalized enrichment scores (NESs) are associated with the ALDHhigh phenotype, whereas gene sets with negative NESs show association with the ALDHlow phenotype. The GSEA applying the c5 GO gene set collection (A), the c2 curated gene sets (B), and the c3 transcription factor target gene set collection (C).