Abstract

It has recently been shown that the high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) E6 proteins can target the PDZ-domain containing proteins, Dlg, MUPP-1, MAGI-1 and hScrib for proteasome-mediated degradation. However, the E6 proteins from HPV-16 and HPV-18 (the two most common high-risk virus types) differ in their ability to target these proteins in a manner that correlates with their malignant potential. To investigate the underlying mechanisms for this, we have mutated HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6s to give each protein the other’s PDZ-binding motif. Analysis of these mutants shows that the greater ability of HPV-18 E6 to bind to these proteins and to target them for degradation is indeed due to a single amino acid difference. Using a number of assays, we show that the E6 proteins interact specifically with only one of the five PDZ domains of MAGI-1, and this is the first interaction described for this particular PDZ domain. We also show that the guanylate kinase homology domain and the regions of MAGI-1 down-stream of amino acid 733 are not required for the degradation of MAGI-1. Finally, in a series of comparative analyses, we show that the degradation of MAGI-1 occurs through a different mechanism from that used by the E6 protein to induce the degradation of Dlg and p53.

Keywords: HPV, E6, Dlg, MAGI-1, transformation

Introduction

The HPV-18 and HPV-16 E6 proteins have been shown to target a number of cellular proteins for ubiquitin-mediated degradation, including p53 (Scheffner et al., 1990; Huibregtse et al., 1991, 1993), c-Myc (Gross-Mesilaty et al., 1998) and Bak (Thomas and Banks, 1998, 1999). More recently, they have also been shown to target a number of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) proteins, including Dlg (Kiyono et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1997; Gardiol et al., 1999; Pim et al., 2000), hScrib (Nakagawa and Huibregtse, 2000), and MAGI-1 (Glaunsinger et al., 2000), as well as a non-MAGUK, PDZ domain-containing protein, MUPP-1 (Lee et al., 2000). The MAGUK proteins are characterized by having a large number of specific protein recognition domains, including WW or SH3 domains, a guanylate kinase (GuK) homology domain and several PDZ domains (Ponting and Phillips, 1995; Saras and Heldin, 1996; Kim, 1997; Kim et al., 1998). Interestingly, the high-risk E6 proteins all appear to interact with their target MAGUKs via the PDZ domains (Kiyono et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1997, 2000; Gardiol et al., 1999; Glaunsinger et al., 2000; Nakagawa and Huibregtse, 2000). These domains are characterized by stretches of 80–90 amino acids (Ponting and Phillips, 1995; Fanning and Anderson, 1999), which bind with high affinity to specific sequences (T/SXV) (Songyang et al., 1997), usually found in the extreme carboxy termini of their target proteins. Such specific carboxy terminal sequences have been identified in the Adenovirus 9 E4-ORF1 protein, the E6 proteins of high-risk HPV types and the HTLV-1 Tax protein (Lee et al., 1997) and, depending on the assay system used, contribute to viral transforming activity (Kiyono et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1997). MAGUKs are localized at regions of cell-cell contact, such as tight junctions in epithelial cells and synaptic junctions in neurons, where they are believed to function as molecular scaffolds in the formation of multi-molecular complexes via their protein-protein interacting domains (Gomperts, 1996; Mitic and Anderson, 1998; Craven and Bredt, 1998). Although little is known about the function of many of these proteins, two of the E6 targets, Dlg and Scrib have been shown to be essential for the regulation of cell growth and polarity in Drosophila, leading to their being characterized as potential tumour suppressor proteins (Bilder et al., 2000). MAGI-1 (membrane associated guanylate kinase with inverted domain structure) has also been shown to be localized at tight junctions of epithelial cells (Dobrosotskaya et al., 1997; Ide et al., 1999). It is also found in complex with β-catenin (Dobrosotskaya and James, 2000), deregulation of which is a hallmark of tumour progression in many different cancers (reviewed in Polakis, 1999). The closely related MAGI-2 and MAGI-3 proteins, have also recently been shown also to be associated with the regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor, a component of the PKB/Akt kinase regulation pathway (Wu et al., 2000a,b; Li et al., 1998; Downward, 1998; Stambolic et al., 1998). In this case, both MAGI-2 and 3 were shown to be required for PTEN’s activity in efficiently down-regulating the PKB pathway, upregulation of which is associated with cell survival and proliferation (Marte and Downward, 1997; Downward 1988, for reviews). Therefore, the high risk HPV E6 proteins would appear to be intimately involved in de-regulating a number of aspects of cell homeostasis related to the regulation of cell growth and polarity in response to cell contact.

In this study we have analysed in detail the interactions between the HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 proteins and their MAGUK target proteins, MAGI-1 and Dlg. A mutational analysis of the PDZ-binding motif of HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 showed that a single amino acid residue difference (L/V) is sufficient to have significant effects upon the ability of E6 to bind to the MAGUKs. This change largely accounts for the differences between HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6s in their abilities to target MAGUKs for degradation. However, comparison of the E6-mediated degradation of p53, Dlg and MAGI-1, together with a mutational analysis of HPV-18 E6, provides strong evidence that E6 proteins use substantially different mechanisms to induce the degradation of each of these three protein targets.

In addition, we also demonstrate that, of the five PDZ domains of MAGI-1, the HPV-18 E6 protein binds specifically only to PDZ domain 1, and that this binding is required for the induction of MAGI-1 degradation. This is the first description of a specific interaction for this PDZ domain of MAGI-1 and indicates that the targeting of PDZ domains by HPV E6 proteins is also highly specific. The potential for design of specific antiviral compounds is clear.

Results

Comparison of the HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 PDZ binding motifs

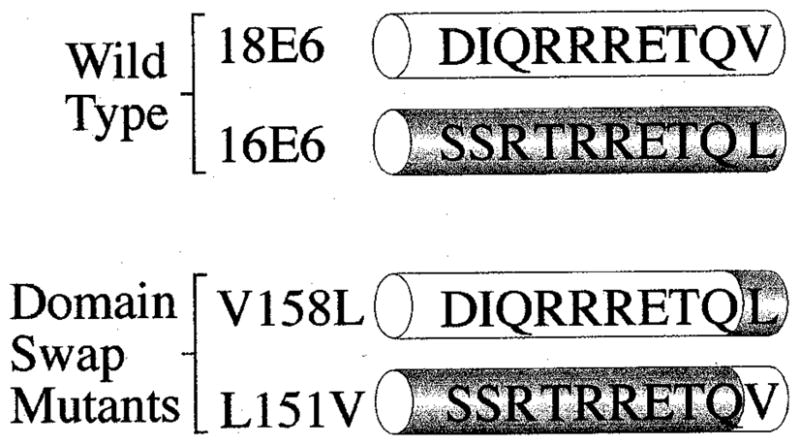

We had previously shown that HPV-18 E6 could target the Dlg tumour suppressor for degradation more efficiently than HPV-16 E6. This activity appeared to be related to the higher affinity with which HPV-18 E6 could interact with this PDZ domain-containing target protein (Gardiol et al., 1999; Pim et al., 2000). Since HPV-18 E6 has a perfect consensus PDZ-binding motif, and HPV-16 E6 has a degenerate one, it seemed possible that differences between the two HPV E6 proteins with respect to their ability to target PDZ domain containing targets might be due to this intertypic variation. To assess this possibility, we made mutations in the PDZ-binding motifs of the HPV-18 and HPV-16 E6 proteins, such that each protein acquired the other’s PDZ binding motif. The sequences of these domains swap mutants (18E6V158L and 16E6L151V) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Alignment of the carboxy-terminal amino acid residues of wild type and mutant HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 proteins

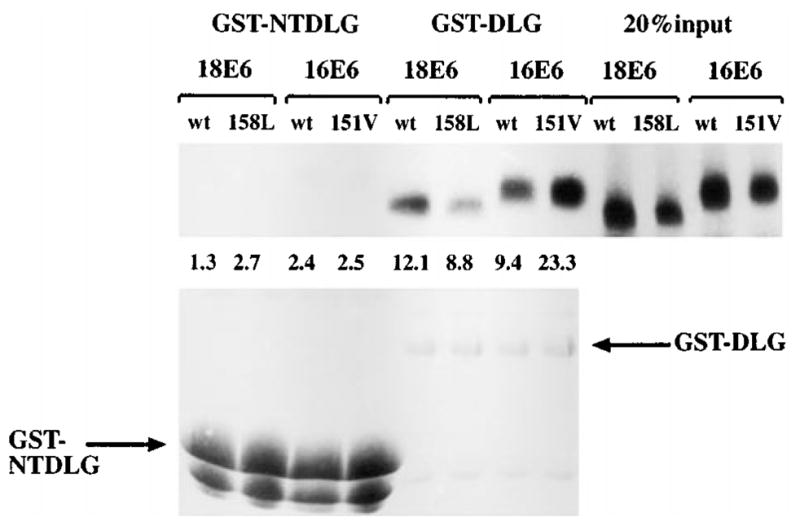

We then investigated the effects of these mutations upon the binding activities of the E6 proteins to Dlg. To do this, we performed GST pull-down assays using in vitro translated E6 proteins, together with either GST-Dlg or GST-NTDlg, which lacks the PDZ domains and is thus not a target for E6 binding (Lee et al., 1997; Gardiol et al., 1999). The GST fusion proteins were extracted and bound to glutathione-agarose and a binding assay was performed as described previously (Pim et al., 2000). The results can be seen in Figure 2 where it is clear that, as expected, HPV-18 E6 binds to GST-Dlg somewhat more strongly than HPV-16 E6 and neither E6 protein binds to GST-NTDlg. Most significantly however, it is clear that the 18E6V158L mutant binds considerably less strongly than the wild type HPV-18 E6, whereas the 16E6L151V mutant binds much more strongly than the wild type HPV-16 E6 protein. These results demonstrate that the single amino acid difference between the HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 proteins in this binding motif has a profound effect upon the ability of these E6 proteins to bind to a MAGUK target.

Figure 2.

The domain-swap mutants of E6 differ in their ability to bind GST-DLG in vitro. The upper panel shows 20% of input in vitro translated E6 proteins, together with that retained on either GST-NTDLG or GST-DLG. The numbers indicate the percentage of load retained. The lower panel shows the same gel rehydrated and stained with Coomassie Blue to control GST fusion protein input

In vitro degradation of E6 target proteins

Having shown that this single amino acid difference in the PDZ binding motif of E6 has a significant effect upon its binding to a PDZ domain-containing target, we then wished to know what effect it had upon the ability of E6 to degrade known target proteins. We therefore performed degradation assays using in vitro translated wild type and mutant E6 proteins together with in vitro translated MAGI-1, Dlg and p53. The results of these assays are shown in Figure 3. The wild type HPV-18 E6 and HPV-16 E6 clearly induce the degradation of all three targets, with HPV-18 E6 being somewhat more effective than HPV-16 E6 in degrading Dlg and MAGI-1, and the reverse being true for p53, as might be expected from previous reports (Scheffner et al., 1990, 1991; Huibregtse et al., 1991, 1993). However the PDZ binding domain swap mutants show two interesting characteristics: first, 18E6V158L is severely reduced in its ability to induce the degradation of both MAGI-1 and Dlg, showing that wild type HPV-18E6’s greater effectiveness in this assay correlates with its having a more effective PDZ binding motif. Secondly, and more interestingly, 16E6L151V is much more effective than either wild type HPV-16 or HPV-18 E6 in inducing the degradation of both MAGI-1 and Dlg. This correlates perfectly with the increased levels of 16E6L151V binding to Dlg seen in Figure 2, and demonstrates that sequences outside the core ETQV/L PDZ binding domain of E6 contribute to its ability to bind PDZ domain-containing targets.

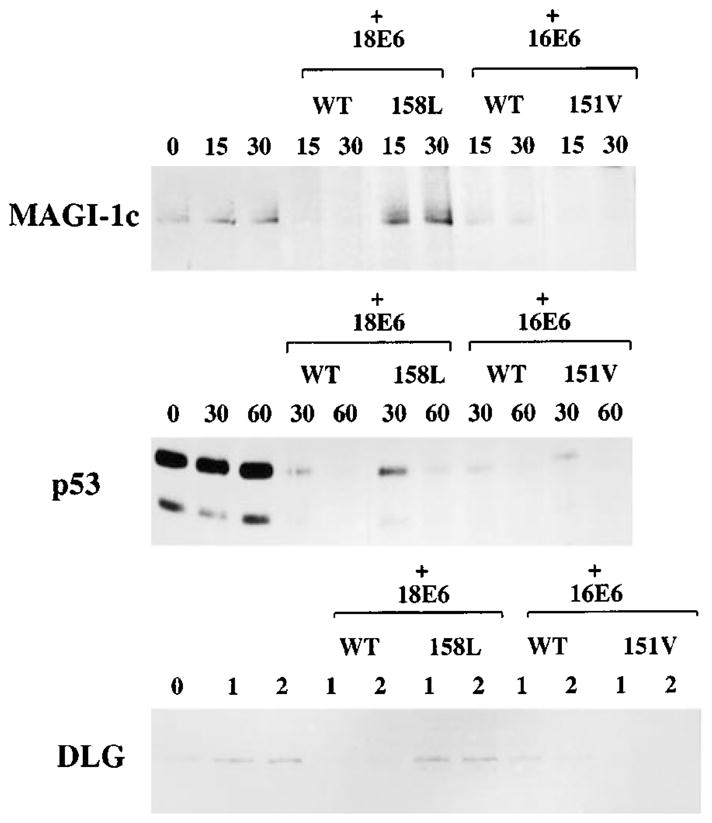

Figure 3.

In vitro degradation of E6 target proteins with the domain swap mutants. In vitro translated wild type and mutant E6 proteins were incubated with in vitro translated MAGI-1, DLG or p53. The MAGI-1 assay was incubated for 15 and 30 min, the p53 assay for 30 and 60 min, and the DLG assay for 1 and 2 h. In each case, the remaining target protein was detected by immunoprecipitation, followed by SDS–PAGE and auto-radiography

A final, and perhaps most interesting, point of interest from this analysis is the comparative time taken for E6 to degrade its different target proteins. Thus, MAGI-1c and p53 are degraded with similar kinetics whereas Dlg is significantly less susceptible to E6-induced degradation. This suggests that the degradation of Dlg and MAGI-1 by E6 most likely occurs through different mechanisms.

Affinity of HPV-18 E6 for its target proteins

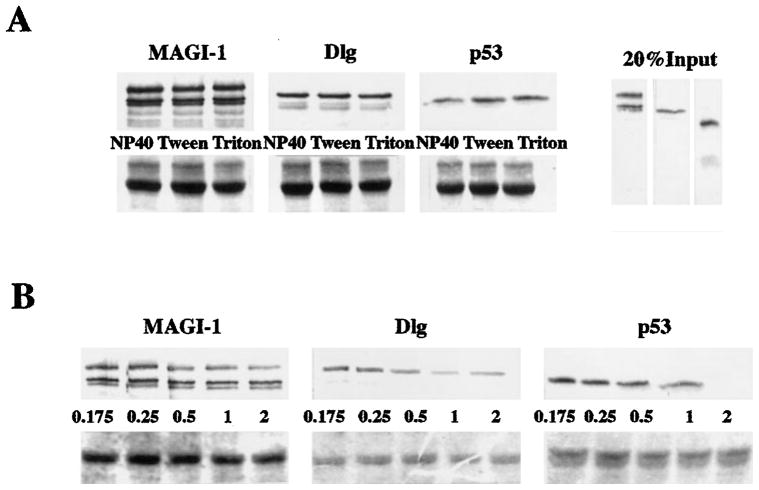

It was possible that the differences in susceptibility to E6-induced degradation seen in Figure 3 might be related to the affinity of binding between the E6s and their targets. To investigate this possibility we performed in vitro binding assays with GST-18E6 fusion protein and in vitro translated MAGI-1, Dlg and p53 with a number of different detergents and at various concentrations of NaCl. The results are shown in Figure 4. It is clear from Figure 4a that both MAGI-1 and Dlg bind to GST-18E6 with similar stabilities in the presence of 2% Nonidet P-40, 2% Tween and 2% Triton X-100. The binding of p53 to GST-18E6 appears to be similarly stable, except in the presence of 2% NP-40, which appears to significantly reduce the level of binding.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the binding affinities between GST-HPV-18 E6 and the E6 target proteins. (a) Binding affinities in different detergents. The upper panels show GST pull-down assays using GST-18E6 and in vitro translated MAGI-1, Dlg and p53. The samples were each washed with 2% of the detergent shown, in PBS. Twenty per cent of the respective input protein are shown in the right hand panel. The lower panels show the rehydrated and Coomassie-stained gels. (b) Binding affinities at increasing concentrations of NaCl. Similar binding assays were washed with either PBS alone (0.175 M NaCl), or with increasing concentrations (M) of NaCl, as indicated. The lower panels show the rehydrated and Coomassie-stained gels

When increasing concentrations of NaCl were used, as can be seen in Figure 4b, the binding of MAGI-1 and Dlg to GST-18E6 again appeared to be similar, with readily detectable levels of binding being retained in 2 M NaCl. In contrast, the binding of p53 is completely disrupted by 2 M NaCl. Thus the binding affinities of MAGI-1 and Dlg to HPV-18 E6 appear to be similar, and the binding of p53 is somewhat more easily disrupted. It is noteworthy that these binding affinities show no correlation with the susceptibility to E6-induced degradation seen in Figure 3, where MAGI-1 and Dlg exhibit very different kinetics of degradation, yet have very similar binding affinities.

Thus the differences in the susceptibility of MAGI-1 and Dlg to HPV E6-induced degradation are not a reflection of differences in the E6/MAGUK binding. It seems most probable that they reflect differences in the exact mechanism of interaction of the E6 proteins and their substrates with the components of the degradation machinery.

Mutational analysis of MAGI-1

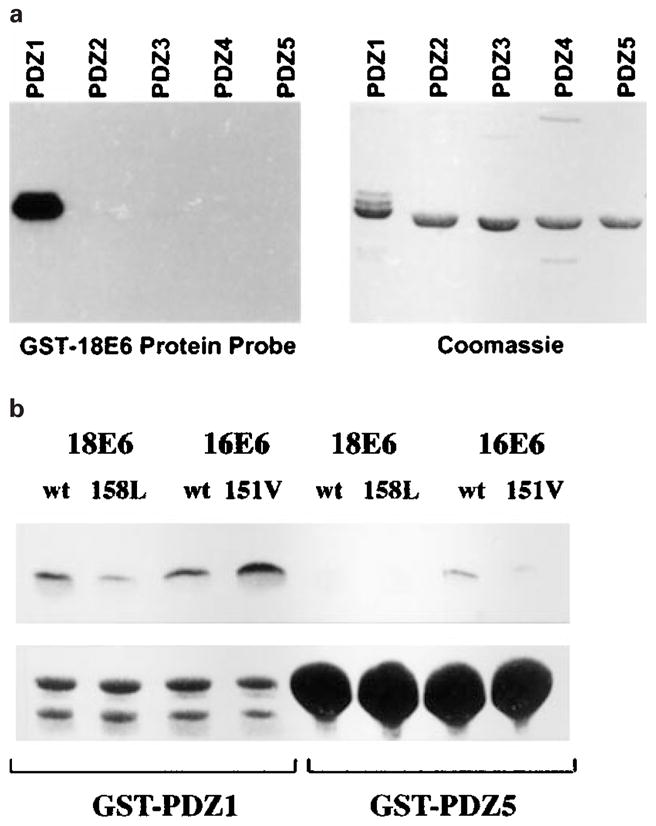

Having shown that a single amino acid difference between the PDZ-binding motifs of HPV-16 E6 and HPV-18 E6 was responsible for the differences in their strength of interaction with the MAGUKs, we turned our attention to the MAGI-1 protein. Previous studies have shown that the individual PDZ binding domains of MAGI proteins interact specifically with target proteins (Dobrosotskaya and James, 2000; Wu et al., 2000a,b; Patrie et al., 2001). Therefore it was obviously of interest to determine whether the E6/MAGI-1 interaction was specific to one PDZ domain. To do this, a series of constructs was made, in which each of the MAGI-1 PDZ domains was individually fused to GST. To assess the binding of E6 to these regions, they were expressed in E. coli and, after purification, were separated by SDS –PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane. This membrane was then probed with a radiolabelled HPV-18 E6 and analysed by auto-radiography after extensive washing. It can be seen from the results shown in Figure 5a that HPV-18 E6 binds predominantly to GST-PDZ1. An equivalent assay was also performed using a mutant of HPV-18 E6 with a disrupted PDZ-binding motif (V158A), in this case no binding was seen (data not shown).

Figure 5.

GST-18E6 binds specifically to GST-PDZ domain 1 of MAGI-1. (a) GST fusion proteins were constructed, consisting of each individual PDZ domain of MAGI-1. They were purified, separated by SDS –PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane, which was then probed with a purified, radiolabelled GST-HPV18 E6 fusion protein. Bound radiolabelled protein was detected by autoradiography. (b) A GST pull-down assay was performed using GST-PDZ1 and GST-PDZ5 proteins, together with in vitro translated wild type HPV-18 and HPV-16 E6s, and the domain-swap mutants E6. The percentage of wt 18E6, V158L, wt 16E6, L151V loads retained were 14.3, 6.7, 10.8 and 22.1% respectively on GST-PDZ1, and 2.5, 2.4, 3.2 and 2.6% respectively on GST-PDZ5

To assess the binding of the domain-swap mutants to MAGI-1 a GST pull-down assay was performed using in vitro translated HPV E6 proteins and GST-PDZ1 and GST-PDZ5 expressed in E. coli. The results can be seen in Figure 5b: the E6 proteins appear to bind strongly to GST-PDZ1 with qualitatively similar affinities to their affinities for GST-Dlg (as seen in Figure 2). However none of the E6 proteins binds strongly to GST-PDZ5, confirming the specificity of the interaction. This is particularly striking since the PDZ domains 1 and 5 of MAGI-1 share the greatest homology (Dobrosotskaya et al., 1997) and yet the binding seen here is substantially different.

In vitro degradation of MAGI-1 requires only a small portion of the protein in addition to PDZ domain 1

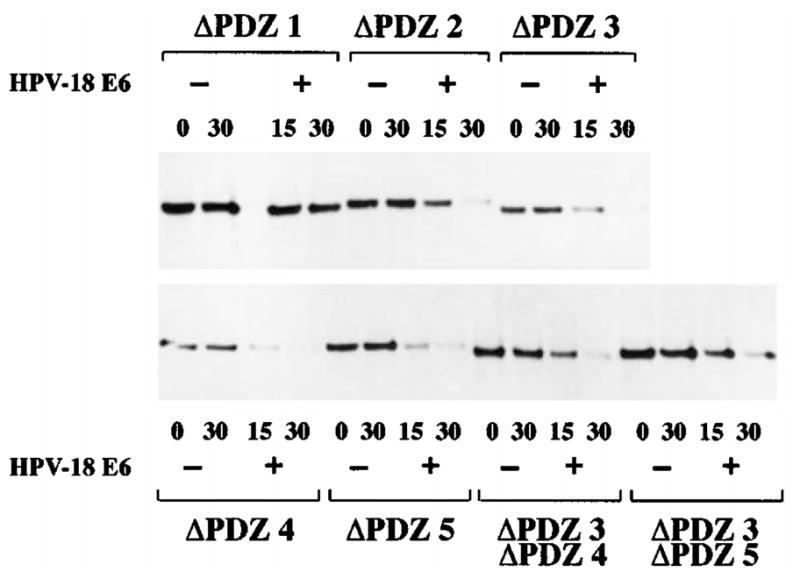

To determine whether PDZ domain 1 was required for the E6-induced degradation of MAGI-1, a series of deletion mutants was made, each lacking either one or two PDZ domains. For technical reasons these mutants were made in the MAGI-1b isoform. These mutants and HPV-18 E6 were translated in vitro, and an in vitro degradation assay was performed as before. It is clear from the results shown in Figure 6 that HPV-18 E6 can induce the degradation of each of the mutants, with the exception of the ΔPDZ1 mutant. A degradation assay using HPV-16 E6 gave precisely similar results (data not shown). Thus the binding of E6 to MAGI-1 occurs through the PDZ1 domain, and this binding is required for the induction of MAGI-1 degradation.

Figure 6.

In vitro degradation of MAGI-1 requires PDZ domain 1. The MAGI-1b PDZ deletion mutants were translated in vitro, and were then incubated at 30°C for the time/minutes indicated, with or without HPV-18 E6. The remaining protein was detected by immunoprecipitation and autoradiography, as before

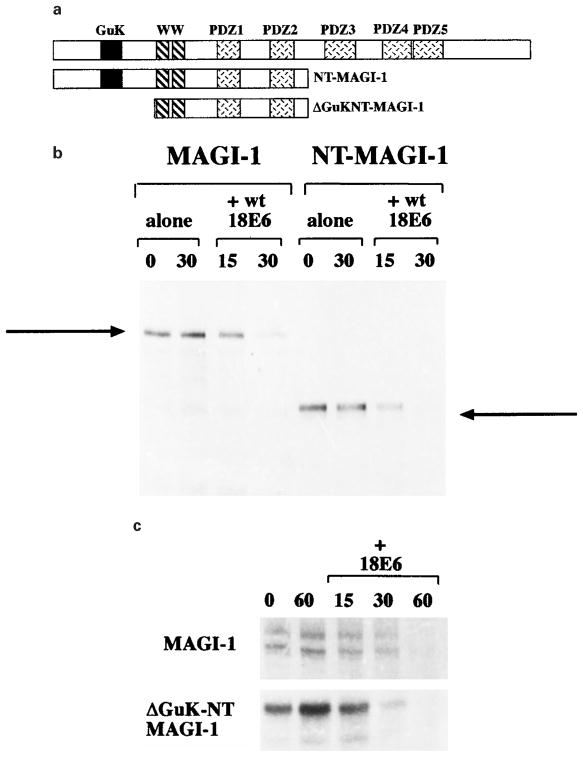

Having shown that the binding of E6 to the PDZ1 domain is essential for induction of MAGI-1 degradation, we were then interested in determining whether any other region of MAGI-1 was also required. We therefore constructed a truncation mutant of MAGI-1, which terminates at amino acid residue 773 and thus lacks the PDZ domains 3–5; this was named NT-MAGI-1 and is shown schematically in Figure 7a. As before, an in vitro degradation assay was performed using full-length MAGI-1 as a positive control. It can be seen in Figure 7b that the NT-MAGI-1 is as susceptible to HPV-18 E6-induced degradation as the full-length MAGI-1.

Figure 7.

Only the amino terminal half of MAGI-1 is required for HPV-18 E6-induced degradation. (a) A schematic diagram of the MAGI-1 deletion mutants. (b) Wild type MAGI-1 and the NT-MAGI-1 mutant were translated in vitro and in vitro degradation assays were performed in the presence of HPV-18 E6 for 15 and 30 min. (c) Wild type MAGI-1 and the ΔGuK-NT-MAGI-1 mutant were translated in vitro and in vitro degradation assays were performed as in b

The NT-MAGI-1 mutant was then further truncated, removing the amino terminal 293 amino acid residues (also shown in Figure 7a). As can be seen from Figure 7c this mutant, called ΔGuK-NT-MAGI-1, is also similarly susceptible to HPV-18 E6-mediated degradation. These analyses indicate that, at most, only the region of the protein from amino acid residue 293 to 733 is required for the susceptibility to E6-induced degradation. Furthermore, they imply that the ubiquitin-protein ligase specific for the degradation must also bind to the N-terminal part of the MAGI-1 protein, but that neither the guanylate kinase homology domain (amino acid residues 142–206) nor the PDZ domain 2 (amino acid residues 628–701) is involved. This suggests that only the region between amino acid residues 293 and 627 is required.

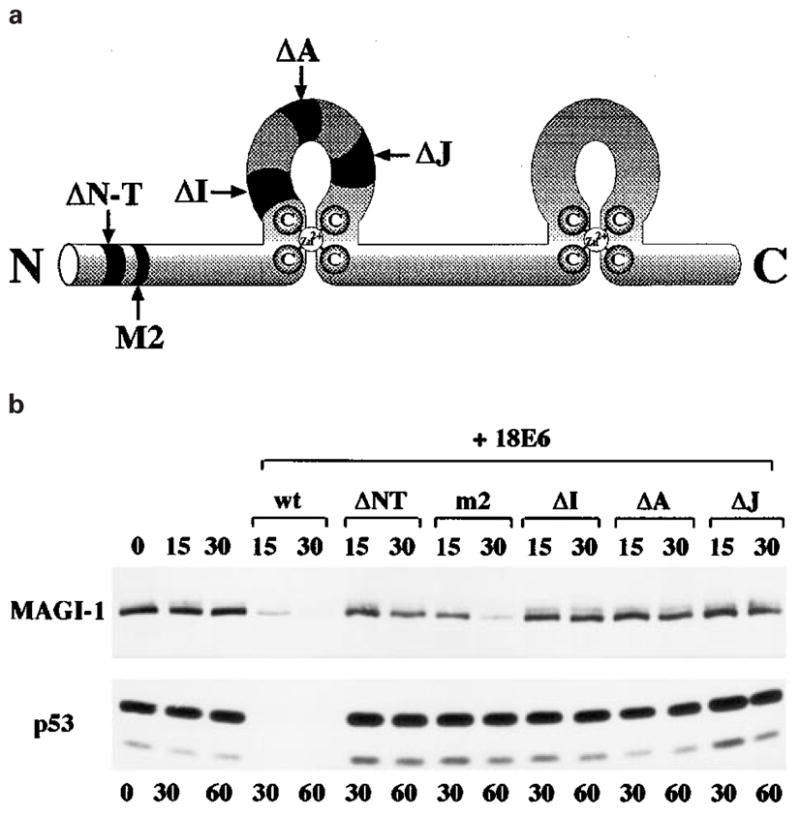

Comparison of HPV-18 E6 mutants in the degradation of MAGI-1 and p53

Multiple regions of E6 are required for binding and inducing the degradation of p53, with regions in the carboxy terminal half being principally involved in p53 binding and regions in the amino terminal half being required for p53 degradation (Crook et al., 1991a; Mietz et al., 1992; Pim et al., 1994; Li and Coffino, 1996; Gardiol and Banks, 1998). Previously, we had shown that E6-mediated degradation of Dlg was different from E6-mediated degradation of p53, based on a mutational analysis of the HPV-18 E6 protein, and on the ability of HPV-18 E6 to induce the degradation of Dlg in wheatgerm extract (Pim et al., 2000). Therefore we used the same panel of HPV-18 E6 mutants (Pim et al., 1994; Gardiol and Banks, 1998), shown in Figure 8a, to determine whether MAGI-1 degradation by E6 was also different from that of p53. In vitro degradation assays were performed using the different E6 mutants, and p53 and MAGI-1 were compared. The results are shown in Figure 8b. It is clear that, as we would expect, none of these mutants was capable of inducing the degradation of p53. It is also clear, however, that the m2 and, to a lesser extent, ΔNT mutants are capable of inducing the degradation of MAGI-1.

Figure 8.

HPV-18 E6 induces the degradation of MAGI-1 by a different mechanism from that used in the degradation of p53. (a) A schematic diagram of the HPV-18 E6 protein, showing the positions of the deletion mutants used. (b) A comparison of the in vitro degradation of p53 and of MAGI-1 induced by the deletion mutants of HPV-18 E6. MAGI-1 was incubated with E6 for 15 and 30 min, while p53 was incubated for 30 and 60 min

These results thus provide further evidence that the means by which E6 induces the degradation of p53 and MAGI-1 are completely different.

Discussion

A number of DNA tumour virus proteins have the ability to target certain cellular proteins and inactivate them. The best known interactions are those involving the tumour suppressor proteins p53 and pRb, which are targeted by, amongst others, Adenovirus, Simian virus 40 (SV40) and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) proteins. The fact that a diverse range of viruses all inactivate the same targets, albeit by different means, implies that these viruses have a common requirement to overcome certain obstacles to their replication and, further, that their doing so may predispose their host cells to oncogenic transformation. Recently, some members of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family have also been shown to be targets for the Adenovirus 9 E4-ORF1 and the E6 proteins of the oncogenic HPV types (Kiyono et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1997, 2000; Gardiol et al., 1999; Pim et al., 2000; Glaunsinger et al., 2000).

In this study we have performed an extensive analysis of the interactions between the MAGI-1 scaffolding protein and the E6 proteins of the oncogenic HPV types 16 and 18. We had previously shown that HPV-18 E6 was more effective than HPV-16 E6 in binding to Dlg and in inducing its degradation (Gardiol et al., 1999; Pim et al., 2000). Here we show that the single amino acid difference in the PDZ binding motif, ETQV/L, is solely responsible for the increased effectiveness of HPV-18 E6, and we also show that this appears to hold true in the case of another PDZ domain protein, MAGI-1.

The PDZ binding motif has been strictly defined and our results show that it is HPV-18E6’s possession of a perfect motif that renders it more effective in the induction of Dlg and MAGI-1 degradation. However it is interesting that if this motif is transferred to HPV-16 E6, that protein becomes much more effective than wild type HPV-18 E6 in binding and inducing the degradation of these MAGUKs. In contrast, when the HPV-16 E6 binding motif is transferred to HPV-18 E6, then its ability to bind and degrade its MAGUK targets is almost completely abolished. These results highlight two important features of the E6-MAGUK interaction. First, HPV-18 E6 is the more efficient degrader of these proteins, largely due to its intrinsically stronger ability to bind, due to having a Valine rather than Leucine as the carboxy terminal residue. Secondly, that other residues, in addition to the core S/TXV/L binding motif, also play a role in the E6-MAGUK interaction. It is interesting to speculate that specificity may also be conferred, in part, by the run of basic Arginine residues immediately prior to the consensus PDZ binding motif. Studies are currently in progress to investigate this further.

There is mounting evidence that the degradation of MAGUK proteins by E6 is different from their degradation of p53. HPV-18 E6 can induce the degradation of Dlg in wheatgerm extract (Pim et al., 2000), from which E6AP is absent (Huibregtse et al., 1991, 1993); and low-risk HPV E6 proteins, which do not interact with E6-AP, can also degrade Dlg when provided with a PDZ-binding consensus sequence (Pim et al., 2000). In addition, we have shown here that mutants of HPV-18 E6 that cannot induce the degradation of p53 (ΔNT and m2) are still able to induce the degradation of MAGI-1. This indicates that if E6AP is, in fact, involved in the degradation of MAGI-1, its mode of action must be different from that involved in p53 degradation. Similarly, we had previously reported that the ΔNT and m2 mutants also retain the ability to induce the degradation of Dlg. This might suggest that Dlg and MAGI-1 are degraded by E6 through similar mechanisms. However, a compelling argument against this is found in the contrast between the similarity of the MAGI-1 and Dlg binding affinities on GST-18E6 and the very marked difference in the kinetics of their E6-induced degradation. Thus, MAGI-1 is highly susceptible to E6-induced degradation, with complete clearance of the protein in 30 min. In contrast, complete clearance of Dlg requires at least 2 h.

Perhaps the most interesting finding in this study is that the binding of E6 to MAGI-1 occurs only through PDZ domain 1. Since this occurs despite the high levels of homology, both of PDZ domains (particularly PDZ1 and PDZ5 of MAGI-1), and of PDZ domain-binding motifs, it is particularly striking. This is the first report of any specific binding to this MAGI-1 PDZ domain and is of great interest for several reasons: it might even be possible to determine what class of proteins normally interacts with this PDZ domain, by comparison with the E6 binding domain. This also raises the question of why this particular PDZ domain is targeted by HPV E6. It is possible that MAGI-1 might be involved in some interactions particularly detrimental to viral replication when that particular PDZ domain is vacant. In addition to raising these intellectually interesting questions, this finding also raises the possibility of engineering chemotherapeutic agents specifically capable of preventing the interaction of high risk HPV E6 proteins with one of their cellular targets.

Members of the MAGI protein family have been shown to interact with the PTEN tumour suppressor (Wu et al., 2000a,b). This phosphatase specifically dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5 triphosphate (PtIns(3,4,5)P3) which, in turn, prevents activation of Protein B Kinase (Klippel et al., 1996; Marte et al., 1997; Franke et al., 1997). Protein kinase B (PKB) is a major regulator of cellular growth and has been implicated, once activated, in a number of pathways leading to cell survival and proliferation (Marte and Downward, 1997; Downward, 1998, for reviews). The interaction of MAGI family proteins with PTEN appears to be crucial for their activity in this system and thus for PTEN’s tumour suppressor activities (Wu et al., 2000a,b). Thus, the intervention of HPV E6 proteins in directing the degradation of MAGI-1 would, in theory, tend to increase cell survival and proliferation, providing a suitable environment for viral DNA replication, but also increasing the like-lihood of oncogenic transformation. Interestingly, one preliminary study detected PTEN mutations in the majority of endometrial carcinomas tested, but in none of the cervical carcinomas tested (Tashiro et al., 1997); this is suggestively similar to the case with p53, which is rarely mutated in cervical cancers and which is also a target for E6-induced degradation (Crook et al., 1991b; Scheffner et al., 1991). In this context, our finding that the HPV E6 proteins interact specifically with only one of MAGI-1’s five PDZ domains leads to the encouraging possibility of devising inhibitors of the E6/MAGI-1 interaction that do not affect other PDZ domain interactions. These in turn might lead to the development of more specific and non-toxic chemotherapeutic agents.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 genes were cloned into pSP64, and have been described previously, as has the HPV-18 E6 mutant series (Pim et al., 1994; Gardiol and Banks, 1998).

The domain swap mutants, HPV-18 E6 V158L and HPV-16 E6 L151V, were generated by oligo-directed PCR, cloned into pSP64 and verified by sequencing using the Amersham Sequenase kit.

FLAG-tagged MAGI-1c was cloned into pCDNA-3, as described previously (Glaunsinger et al., 2000)

The pCDNA-3:Dlg construct, for in vitro translation, and the pGEX:Dlg and pGEX:NTDlg, for GST-fusion protein expression have been described previously (Gardiol et al., 1999), as has the pSP64:p53 (Thomas et al., 1995).

The NT-MAGI-1 expressing plasmid was constructed as follows: pGWI:HA-MAGI-1 was digested with HindIII and ApaI and the resulting fragment was ligated into pCDNA-3. When expressed in vitro this gives an HA-tagged MAGI-1, truncated at amino acid residue (aa) 773.

The ΔGuK-NT-MAGI-1 expressing plasmid was constructed by oligo-directed PCR mutagenesis of the NT-MAGI-1 expressing plasmid and the resulting fragment was cloned into the HindIII and ApaI sites of pCDNA-3. When expressed in vitro this gives a protein consisting of the aa 293–733 of MAGI-1.

The MAGI-1b PDZ deletion mutants were cloned into the HindIII/EcoRI sites of pCDNA-3 with FLAG tags at their amino termini, and they contain the following deletions: ΔPDZ1 lacks nucleotides 2284–2571 (aa 454–582); ΔPDZ2 lacks nucleotides 2800–3030 (aa 628–701); ΔPDZ3 lacks nucleotides 3313–3549 (aa 796–875); ΔPDZ4 lacks nucleotides 3784–4003 (aa 953–1026); ΔPDZ5 lacks nucleotides 4054–4272 (aa 1003–1076); ΔPDZ3,4 lacks nucleotides 3313–3549 and 3784–4003 (aa 796–875 and 953–1026); ΔPDZ3,5 lacks nucleotides 3313–3549 and 4054–4272 (aa 796–875 and 1003–1076).

GST-fusion protein pull-down assays

These were performed as described previously (Pim et al., 2000). Briefly, overnight cultures of E. coli containing the plasmid of interest were passaged and, once in log phase, the expression of GST fusion protein was induced by adding β-D-isopropylthiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM. After 3 h the cells were harvested, resuspended in PBS/1% Triton X-100 and lysed by sonication for 20 s. The cleared supernatant was incubated overnight with glutathione-agarose and washed extensively with PBS/1% Triton. SDS –PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining were used to assess the effectiveness of the washing procedure and to balance the GST fusion protein inputs. Aliquots were incubated with equal concentrations of in vitro translated proteins at room temperature for 1 h. After extensive washing with PBS/1% Nonidet-P40, unless otherwise stated in the text, the retained proteins were visualized by SDS –PAGE and autoradiography and phosphorimager analysis was used to obtain the percentage of load retained.

In vitro degradation assays

Proteins were translated using the Promega TNT coupled transcription translation system, and were radiolabelled with [35S]Cysteine. A 1 μl aliquot of each translate was quantitated by SDS –PAGE and phosphorimager analysis. Using the results of this quantitation, translated target proteins were mixed at a ratio of 1: 5 with the relevant E6 protein and volumes were equalized using water-primed lysate. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C and aliquots taken at the relevant times. Typically, MAGI-1 degradation assays were incubated for 15 and 30 min, p53 degradation assays for 30 and 60 min and Dlg assays for 1 and 2 h. Remaining target protein was immunoprecipitated using 1801 monoclonal antibody (Banks et al., 1986) for p53; a polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against GST-NTDLG (Gardiol et al., 1999) for DLG; a polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against a GST-WW domain fusion protein for un-tagged MAGI-1 and for ΔGuK-NT-MAGI-1; a polyclonal goat anti-FLAG for tagged MAGI-1b (Santa Cruz), or a monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) for tagged NT-MAGI-1.

GST fusion protein blotting

Protein blotting assays and preparation of 32P-labelled probes were performed as described previously (Weiss et al., 1997). Briefly, equivalent amounts of MAGI-1 PDZ domain fusion proteins were separated by SDS –PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Membranes were blocked for 1 h in TBST containing 5% milk, and incubated for 12 h at 4°C with the 32P-labelled GST-18E6 probe (5×105 c.p.m./ml) in TBST. Membranes were then washed extensively in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS) and developed by autoradiography

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Associazione Italiana per Ricerca sul Cancro to L Banks and grant number RO1 CA58541 from the National Institutes of Health to R Yavier.

Footnotes

Note added in proof

A new ligand of the PDZ1 domain of MAGI-1 has recently ben identified as mNET1 (Dobrosotskaya, 2001. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 283, 969–975).

References

- Banks L, Matlashewski G, Crawford L. Eur J Biochem. 1986;159:529–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Li M, Perrimon N. Science. 2000;289:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven S, Bredt D. Cell. 1998;93:495–498. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook T, Tidy J, Vousden K. Cell. 1991a;67:547–556. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook T, Wrede D, Vousden KH. Oncogene. 1991b;6:873–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrosotskaya I, Guy R, James G. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31589–31597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrosotskaya I, James G. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:903–909. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning A, Anderson J. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:767–772. doi: 10.1172/JCI6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke T, Kaplan D, Cantley L, Toker A. Science. 1997;275:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiol D, Banks L. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:1963–1970. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-8-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiol D, Kühne C, Glaunsinger B, Lee S, Javier R, Banks Oncogene. 1999;18:5487–5496. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaunsinger B, Lee S, Thomas M, Banks L, Javier R. Oncogene. 2000;19:5270–5280. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomperts S. Cell. 1996;84:659–662. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross-Mesilaty S, Reinstein E, Bercovich B, Tobias K, Schwartz A, Kahana C, Ciechanover A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8058–8063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huibregtse J, Scheffner M, Howley P. EMBO J. 1991;10:4129–4135. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huibregtse J, Scheffner M, Howley P. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:775–784. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide N, Hata Y, Nishioka H, Hirao K, Yao I, Deguchi M, Mizoguchi A, Nishimori H, Tokino T, Nakamura Y, Takai Y. Oncogene. 1999;18:7810–7815. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, DeMarco S, Marfatia S, Chishti A, Sheng M, Strehler E. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1591–1595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:853–859. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyono T, Hiraiwa A, Fujita M, Hayashi Y, Akiyama T, Ishibashi M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11612–11616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klippel A, Reinhard C, Kavanaugh W, Apell G, Escobedo Mand Williams L. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4117–4127. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Weiss R, Javier R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6670–6675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Glaunsinger B, Mantovani F, Banks L, Javier R. J Virol. 2000;74:9680–9693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9680-9693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Simpson L, Takahashi M, Miliaresis C, Myers M, Tonks N, Parsons R. Cancer Res. 1998;56:5667–5672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Coffino P. J Virol. 1996;70:4509–4516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4509-4516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marte B, Downward J. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:355–358. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marte B, Rodriguez-Vinciana P, Wennstrom S, Warne P, Downward J. Curr Biol. 1997;7:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mietz J, Unger T, Huibregtse J, Howley P. EMBO J. 1992;11:5013–5020. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitic L, Anderson J. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:121–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Huibregtse J. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;21:8244–8253. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8244-8253.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrie KM, Drescher AJ, Goyal M, Wiggins RC, Margolis B. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:667–677. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V124667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pim D, Storey A, Thomas M, Massimi P, Banks L. Oncogene. 1994;9:1869–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pim D, Thomas M, Javier R, Gardiol D, Banks L. Oncogene. 2000;19:719–725. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polakis P. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting C, Phillips C. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:102–103. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88973-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saras J, Heldin C. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:455–458. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)30044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner M, Werness B, Huibregtse J, Levine A, Howley P. Cell. 1990;63:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner M, Munger K, Byrne JC, Howley PM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5523–5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Fanning A, Fu C, Xu J, Marfatia S, Chisti A, Crompton A, Chan A, Anderson J, Cantley L. Science. 1997;275:73–77. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de al Pompa J, Brothers G, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, Ruland J, Penninger J, Siderovski D, Mak T. Cell. 1998;95:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro H, Blazes M, Wu R, Cho K, Bose S, Wang S, Li J, Parsons R, Ellenson L. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3935–3940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Banks L. Oncogene. 1998;17:2943–2954. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Banks L. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1513–1517. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-6-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Massimi P, Jenkins J, Banks L. Oncogene. 1995;10:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R, Gold M, Vogel H, Javier R. J Virol. 1997;71:4385–4394. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4385-4394.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Hepner K, Castelino-Prabhu S, Do D, Kaye M, Yuan X, Wood J, Ross C, Sawyers C, Whang Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000a;97:4233–4238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Dowbenko D, Spencer S, Laura R, Lee J, Gu Q, Laskey L. J Biol Chem. 2000b;275:21477–21485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909741199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]