SUMMARY

Bacteria selectively consume some carbon sources over others through a regulatory mechanism termed catabolite repression. Here, we show that the base pairing RNA Spot 42 plays a broad role in catabolite repression in Escherichia coli by directly repressing genes involved in central and secondary metabolism, redox balancing, and the consumption of diverse non-preferred carbon sources. Many of the genes repressed by Spot 42 are transcriptionally activated by the global regulator CRP. Since CRP represses Spot 42, these regulators participate in a specific regulatory circuit called a multi-output feedforward loop. We found that this loop can reduce leaky expression of target genes in the presence of glucose and can maintain repression of target genes under changing nutrient conditions. Our results suggest that base pairing RNAs in feedforward loops can help shape the steady-state levels and dynamics of gene expression.

Keywords: CRP, dynamics, glucose, regulatory network, small RNA

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria sense and respond to changes in their environment through gene regulatory networks. These networks receive environmental signals and determine the strength and timing of the response. Efforts to study the structure of transcriptional regulatory networks have identified reoccurring patterns termed network motifs (Alon, 2007; Milo et al., 2002; Shen-Orr et al., 2002). These motifs have been implicated in signal processing and are thought to ensure an appropriate and accurate response to environmental changes.

One of the motifs prevalent in the transcriptional regulatory architecture of bacteria is the feedforward loop (Reviewed in Alon, 2007). This motif is comprised of three genes (A, B, and C), where A and B co-regulate C, and A regulates B. When A and B co-regulate multiple genes, the loop is defined as a multi-output feedforward loop. Each feedforward loop can be divided into two regulatory arms responsible for the regulation of C: a direct arm where A regulates C and an indirect arm where A regulates C through B. When the regulatory arms work in opposition to activate or repress C, the loop is termed an incoherent feedforward loop. When the regulatory arms work together, the loop is termed a coherent feedforward loop. Coherent feedforward loops have been predicted to perform a number of functions including processing of multiple environmental signals and shaping the regulatory dynamics of gene expression (Kalir et al., 2005; Mangan and Alon, 2003; Mangan et al., 2003). While feedforward loops and other regulatory circuits solely comprised of transcription regulators have been studied in detail, we are only beginning to understand how regulators operating through other modes of gene regulation are incorporated into regulatory circuits (Reviewed in Beisel and Storz, 2010).

A common class of post-transcriptional regulators in bacteria is the regulatory small RNAs (sRNAs) (Reviewed in Waters and Storz, 2009). Bacterial sRNAs have been implicated in diverse cellular responses associated with environmental stresses, changes in nutrient conditions, and host invasion. sRNAs operate through multiple regulatory mechanisms, such as binding directly to regulatory proteins or base pairing with target mRNAs. Most base pairing sRNAs rely on the RNA chaperone Hfq to form limited base-pairing interactions with target mRNAs. This base pairing affects mRNA stability and/or translational efficiency, resulting in either an increase or decrease in protein synthesis. While regulators and gene targets of many base pairing sRNAs have been identified, little is known how these sRNAs participate in regulatory networks to help cells respond to changes in the environment.

To better understand sRNA participation in gene regulatory networks, we explored how the Hfq-binding sRNA Spot 42 contributes to catabolite repression in E. coli. Catabolite repression is a prevalent regulatory mechanism that allows bacteria to selectively consume specific sugars in a mixture of carbon sources. Underlying catabolite repression are complex regulatory systems that sense the presence of preferred carbon sources and subsequently turn off the uptake and catabolism of non-preferred carbon sources.

One of the central regulators in catabolite repression is the cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) (Reviewed in Görke and Stülke, 2008). CRP is a transcription regulator capable of activating or repressing gene expression, where many of the genes activated by CRP are involved in the uptake and catabolism of non-preferred carbon sources. CRP can regulate gene expression only when bound to the secondary messenger cyclic AMP (cAMP). cAMP is synthesized by adenylate cyclase in response to different nutrient conditions including the absence of glucose in E. coli. Thus, when glucose is absent in the environment, cAMP activates CRP, which in turn upregulates the expression of genes involved in the consumption of non-preferred carbon sources.

One of the many targets of CRP is the spf gene encoding the base pairing sRNA Spot 42. This sRNA was originally identified over 30 years ago in E. coli as a cellular RNA that is highly abundant in the presence of glucose (Sahagan and Dahlberg, 1979a, b). Subsequent work showed that transcription of spf is repressed by CRP (Polayes et al., 1988). In addition, overexpression of Spot 42 was shown to hamper growth on succinate and introduce a lag in growth following the transfer of cells from minimal glucose media to Luria-Bertani broth (LB) or to minimal glucose media containing casamino acids (Rice and Dahlberg, 1982). Most recently, Spot 42 was shown to function as an Hfq-binding sRNA that base pairs with the galK mRNA to mediate discoordinate expression of the gal operon (Møller et al., 2002a; Møller et al., 2002b). Although galK was the only known target of Spot 42, the reported growth phenotypes following Spot 42 overexpression suggested that this sRNA plays a much broader role in cellular metabolism.

In this study we report that Spot 42 regulates at least 14 additional operons involved in multiple aspects of cellular metabolism including the uptake and catabolism of diverse non-preferred carbon sources. Many of these operons are co-regulated by CRP and Spot 42, which participate in a coherent feedforward loop. We found that, within this loop, Spot 42 can expand the dynamic range of gene regulation and influence the dynamics of the transition into and out of catabolite repression. Our results suggest that feedforward loops containing proteins and sRNAs display different regulatory properties than feedforward loops containing only protein regulators, allowing sRNAs to fill unique regulatory roles in cells.

RESULTS

Spot 42 represses genes linked to catabolite repression

We first carried out microarray analysis to determine whether the Spot 42 RNA acts on transcripts in addition to the galK mRNA. Relative mRNA levels were measured from E. coli cells after transient overexpression of Spot 42. These analyses revealed 16 different genes—5 singly-encoded and 11 encoded in 10 operons—whose levels were consistently increased or decreased at least two-fold relative to the empty vector control across three independent experiments (Table 1). mRNAs for some of the genes were enriched following Hfq co-immunoprecipitation in E. coli and Salmonella and showed altered levels in a Salmonella hfq deletion strain (Table S2) (Ansong et al., 2009; Sittka et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2003). One of the 16 genes was the known Spot 42 target galK, supporting the validity of the newly identified targets. Although a previous study suggested that Spot 42 represses galK only at the level of translation, our microarray analysis suggests that overexpression of Spot 42 can destabilize the galK mRNA.

Table 1.

Microarray analysis of genes modulated at least two-fold following Spot 42 overexpression across three independent experiments.

| Gene | Operon | Assigned genetic function of regulated genea | Evidence for CRP regulation?b | Evidence for Hfq binding and regulation?c | Ratiod |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central/secondary metabolism | |||||

| gltA | gltA | Citrate synthase | Y | Y | −3.0 ± 0.5 |

| maeAe | maeA | Malate dehydrogenase | - | Y | −2.4 ± 0.2 |

| Redox balancing | |||||

| sthA | sthA | Pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase | - | Y | −4.2 ± 0.5 |

| Sugar transport | |||||

| dppBf | dppABCDF | Subunit of dipeptide ABC transporter | - | Y | 2.9 ± 0.8 |

| lldP | lldPRD | Lactate transporter | - | Y | −4.1 ± 3.3 |

| nanC | nanCM | N-acetylneuraminic acid outer membrane channel | Y | - | −3.5 ± 1.8 |

| nanT | nanATEK-yhcH | Sialic acid MFS transporter | Y | Y | −4.3 ± 1.7 |

| srlA | srlAEBD-gutM- srlR-gutQ | Glucitolsorbitol-specific IIC | Y | Y | −12.6 ± 15.9 |

| xylF | xylFGHR | Subunit of xylose ABC transporter | Y | - | −3.3 ± 0.9 |

| Sugar catabolism | |||||

| ebgC | ebgAC | Cryptic gene (evolved β-galactosidase subunit) | - | - | −2.8 ± 1.0 |

| fucI | fucPIKUR | L-fucose isomerase | Y | - | −3.6 ± 1.9 |

| fucK | fucPIKUR | L-fuculose kinase | Y | - | −3.2 ± 1.4 |

| galK | galETKM | Galactokinase | Y | Y | −2.7 ± 0.5 |

| Antioxidant biosynthesis | |||||

| gsp | gsp | Fused glutathionylspermidine amidase & synthetase | - | Y | 4.4 ± 0.5 |

| Unknown | |||||

| yjiA | yjiAX | P-loop guanosine triphosphatase | - | Y | −5.0 ± 0.6 |

| ytfJ | ytfJ | Predicted protein | - | Y | −5.6 ± 0.7 |

Descriptions taken from Ecocyc (www.ecocyc.org).

See Table S1 for a summary of the evidence for catabolite repression and CRP regulation. Y, evidence available; -, no evidence available.

See Table S2 for a summary of the evidence for Hfq binding and regulation.

Ratio of gene levels for pBRplac and pSpot42 samples. Values reflect the average and standard deviation from three independent experiments. Positive and negative values reflect induction and repression, respectively.

maeA is directly regulated by the base pairing sRNA FnrS (Durand and Storz, 2010).

dppA, the gene encoded upstream of dppB in the same operon, is directly regulated by the base pairing sRNA GcvB (Urbanowski et al., 2000).

Most of the downregulated genes identified by microarray analysis are involved in metabolic processes. The gene gltA encodes a citrate synthase that is part of the citric acid cycle, while maeA encodes an NADH-dependent malate dehydrogenase involved in gluconeogenesis. Another gene, sthA, encodes a pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase that uses NAD+ to oxidize NADPH. Most of the remaining genes are involved in the uptake and catabolism of diverse carbon sources, including L-fucose (fucI, fucK), D-xylose (xylF), D-sorbitol (srlA), N-acetylneuraminic acid (nanC, nanT), and L-lactic acid (lldP). The utilization of many of these carbon sources is suppressed under catabolite repression (Table 1), in line with Spot 42-mediated repression of the corresponding genes in the presence of glucose. The two remaining downregulated genes, yjiA and ytfJ, are uncharacterized but may encode regulatory proteins.

One of the upregulated genes, dppB, encodes part of a dipeptide transporter that imports exogenous peptides as a source of amino acids, which may reduce the metabolic burden of amino acid biosynthesis. The other upregulated gene, gsp, encodes a glutathionylspermidine amidase/synthetase. Recent evidence suggests that glutathionylspermidine is synthesized under oxidizing conditions in E. coli and acts as an antioxidant, which may protect glucose-fed cells from oxidative damage during increased metabolic activity (Chiang et al., 2010).

Expression of two of the identified genes, maeA and dppB, is known to be regulated by other base pairing sRNAs. maeA is repressed by the sRNA FnrS (Durand and Storz, 2010) and dppA, the gene upstream of dppB in the same operon, is repressed by the sRNA GcvB (Urbanowski et al., 2000). This observation adds to the growing number of examples of genes and operons whose expression is regulated by multiple sRNAs (See Beisel and Storz, 2010; Vogel, 2009).

To help confirm that Spot 42 affects the expression of the identified targets, we measured mRNA levels for gltA, maeA, sthA, and srlA following Spot 42 overexpression (Figure 1). To increase the mRNA levels of srlA, strains were supplemented with D-sorbitol, the natural inducer of the srl operon (Yamada and Saier, 1988). Northern blot analysis demonstrated that overexpression of Spot 42 reduced gltA, maeA, and sthA mRNA levels (Figure 1A). The analysis also revealed that the addition of the inducer IPTG rapidly increased srlA mRNA levels, which was counteracted by overexpression of Spot 42 (Figure 1B). The increase in srlA mRNA levels following the addition of IPTG was confirmed using four different oligo probes with a plasmid-free strain (data not shown). Overall, these results suggest that Spot 42 represses the levels of the gltA, maeA, sthA, and srlA mRNAs.

Figure 1.

Repression of gltA, maeA, sthA, and srlA following Spot 42 overexpression. The Spot 42 gene spf was cloned downstream of an IPTG-inducible promoter in the plasmid pBRplac, yielding pSpot42. NM525 Δspf::kanR (GS0433) cells transformed with pBRplac or pSpot42 were grown in (A) LB or (B) LB containing 0.2% D-sorbitol to an ABS600 of ~0.3 and treated with 1 mM IPTG. After different periods of time, total RNA was isolated and subjected to northern blot analysis with probes for (A) gltA, maeA, sthA, and (B) srlA. 5S RNA served as a loading control. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

Spot 42 base pairs directly with target genes via three separate regions

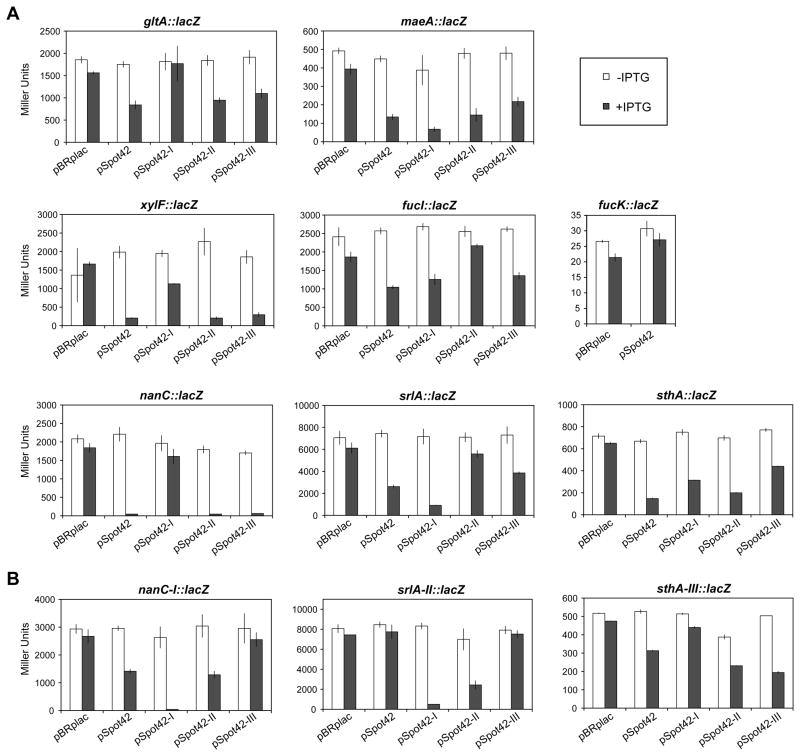

As an independent assay of gene regulation by Spot 42, we constructed lacZ translational reporter fusions under the control of the pBAD promoter for eight of the repressed genes: gltA, maeA, sthA, srlA, nanC, xylF, fucI, and fucK. The lacZ fusions were constructed with regions from each gene spanning from either the transcriptional start site (gltA, maeA, sthA, srlA, nanC) or ~100 nts upstream of the start codon (fucI, fucK) to 9 – 15 codons into the coding region (Mandin and Gottesman, 2009). Assays of these fusions showed that overexpression of wild type Spot 42 reduced β-galactosidase levels for almost all of the tested fusions (Figure 2). The extent of repression varied from 2-fold for gltA to 47-fold for nanC. The one exception was the fucK fusion, which showed no effect of Spot 42 overexpression. The lack of regulation suggests that Spot 42 base pairs with fucK outside of the region included in the lacZ fusion or Spot 42 indirectly regulates fucK mRNA levels by targeting fucI in the same operon.

Figure 2. Mutational analysis of base-pairing interactions between Spot 42 and target mRNAs.

(A) Results for β-galactosidase assays of PM1205 Δspf::kanR (GS0434) cells containing lacZ translational fusions. (B) Results for β-galactosidase assays for lacZ translational fusions with compensatory mutations in the predicted location of base pairing with Spot 42. Derivatives of PM1205 Δspf::kanR transformed with the indicated plasmid were grown in LB to an ABS of ~0.1 and treated with 0.2% arabinose or 0.2% arabinose and 1 mM IPTG for 1 h before being subjected to β-galactosidase assays. The mutations in pSpot42 variant I – III correspond to the indicated mutations in Figure 3A. The compensatory mutations in the lacZ translational fusions correspond to the indicated mutations in Figure 3C. The reported averages and standard deviations are from measurements of cultures from three separate colonies. See Figure S1 for predicted base-pairing interactions between Spot 42 variant I and the srlA::lacZ and maeA::lacZ fusions.

We used the folding algorithm NUPACK to predict whether Spot 42 can base pair directly to the genes used to construct the lacZ fusions (Zadeh et al., 2010). NUPACK predicted that Spot 42 base pairs to these mRNAs through three single-stranded regions found in the sRNA (I – III, Figure 3A,C) (Møller et al., 2002b). In contrast, NUPACK predicted no base pairing interactions between Spot 42 and other known sRNA targets, including ompC, ompF, rpoS, and sodB. Base pairing with the Spot 42 target genes is predicted to occur primarily near the ribosome binding site, although pairing was also predicted upstream of the ribosome binding site (gltA) and within the coding region (sthA) (Figure 3C). The one exception was maeA, for which no base pairing interactions with Spot 42 were predicted. Consistent with the prediction that much of the sRNA is involved in base pairing with target mRNAs, the entire length of Spot 42 is highly conserved in Enterobacteria (Møller et al., 2002b). Although most base pairing sRNAs are predicted to act via one single-stranded region, the FnrS sRNA has been shown to regulate target genes through two single-stranded regions (Durand and Storz, 2010).

Figure 3. Predicted base-pairing interactions between the single-stranded regions of Spot 42 and target mRNAs.

(A) Secondary structure of Spot 42 reported previously (Møller et al., 2002b). The three single-stranded regions are highlighted in gray. Three consecutive nucleotides (white) in each single-stranded region were mutated to disrupt predicted base-pairing interactions with target mRNAs (I – III). (B) Northern blot analysis of NM525 Δspf::kanR (GS0433) cells transformed with pBRplac, pSpot42, or pSpot42 variants I – III. Cells were grown in LB to an ABS600 of ~0.3, treated with 1 mM IPTG, and incubated for 0 min or 30 min. An equimolar concentration of probes spf.north1 and spf.north2 were used to detect all Spot 42 variants on the same membrane. 5S RNA served as a loading control. (C) Genes identified by microarray analysis and base-pairing interactions with Spot 42 predicted by the folding algorithm NUPACK. NUPACK did not predict any significant base-pairing interactions between Spot 42 and maeA. Mutations introduced into pSpot42 and the lacZ translational fusions are designated. The bar below each target gene indicated as a darker arrow designates the predicted location of base pairing with Spot 42. The number above each promoter specifies the number of nucleotides between a transcriptional start site and the start codon of the first gene in the operon.

The lacZ translational fusions were used to investigate whether Spot 42 directly regulates the expression of identified genes through the predicted regions of base pairing. We generated three variants of Spot 42 containing mutations in each single-stranded region that we designed to disrupt the predicted base-pairing interactions (Figure 3A). Northern blot analysis showed that the size and stability of the Spot 42 variants were similar to that of the wild type Spot 42 (Figure 3B). For almost all of the tested fusions, mutations in the single-stranded region of Spot 42 predicted to be involved in base pairing had the greatest impact on regulation (Figure 2A, 3C). The mutation in region I had the greatest impact on the regulation of the gltA, xylF, and nanC fusions, the mutation in region II had the greatest impact on the regulation of the srlA and fucI fusion, and the mutation in region III had the greatest impact on the regulation of the sthA fusion. Note that NUPACK did not predict base pairing between fucI and the mutated nucleotides in region II of Spot 42, suggesting that the NUPACK predictions for fucI are incorrect. None of the mutations had a substantial negative impact on the regulation of the maeA fusion, suggesting that this fusion is regulated through base-pairing interactions that are unaffected by the tested mutations or that the effects of Spot 42 are indirect. The maeA and srlA fusions were more strongly regulated by Spot 42 variant I than by Spot 42, which may be attributed to formation of novel base-pairing interactions between this variant and each fusion as predicted by NUPACK (Figure S1). Overall, these results suggest that the three single-stranded regions of Spot 42 are involved in direct base-pairing interactions with the gltA, nanC, xylF, srlA, and fucI mRNAs.

To validate base pairing through the three single-stranded regions of Spot 42, we made compensatory mutations in the nanC, srlA, and sthA fusions (Figure 3A,C). The compensatory mutations restored regulation by the corresponding variant of Spot 42 and disrupted regulation by the other variants (Figure 2B). The only exception was repression of the mutated srlA fusion by Spot 42 variant I, which also was observed for the srlA fusion (Figure 2A). These results confirm that three single-stranded regions of Spot 42 are involved in base pairing with target mRNAs.

Overexpression of Spot 42 limits growth on specific non-preferred carbon sources

Previous studies showed that cells overexpressing Spot 42 grow slowly on succinate as the sole carbon source (Rice and Dahlberg, 1982). Our analysis identified genes regulated by Spot 42 involved in the consumption of other carbon sources, including N-acetylneuraminic acid (nanC, nanT), D-xylose (xylF), D-sorbitol (srlA), L-fucose (fucI), and L-lactic acid (lldP). We hypothesized that overexpression of Spot 42 would hamper growth on these carbon sources as observed for succinate. To test this hypothesis, we examined growth for cells overexpressing Spot 42 in different types of media (Figure 4). Overexpression of Spot 42 in cells grown in nutrient-rich LB or on casamino acid-enriched M9 containing glycerol slightly reduced growth as cells approached stationary phase. In contrast, overexpression of Spot 42 in cells grown on casamino acid-enriched M9 containing L-fucose, D-sorbitol, D-xylose, N-acetylneuraminic acid and L-lactic acid reduced growth as early as two hours after Spot 42 induction. The observed growth phenotypes were similar to the previously reported growth defect on succinate (Figure 4) (Rice and Dahlberg, 1982). Removal of casamino acids had a negligible impact on the growth defect for glycerol and strengthened the growth defect for L-fucose and D-xylose (Figure S2A). We also measured the growth defect for ΔfucI cells grown in L-fucose and ΔxylF cells grown in D-xylose. The growth defect for both deletion strains was weaker than the growth defect in Spot 42-overexpressing cells, suggesting that Spot 42 regulates multiple genes involved in L-fucose and D-xylose catabolism (Figure S2B). Overall, the additional mRNA targets and the numerous growth phenotypes suggest that Spot 42 plays a much broader role in cellular metabolism than previously realized.

Figure 4. Limited growth on non-preferred carbon sources following Spot 42 overexpression.

NM525 Δspf::kanR (GS0433) cells transformed with pBRplac or pSpot42 were grown overnight in LB or in casamino acid-enriched M9 containing the indicated carbon source and diluted to an ABS600 of 0.01 into the same type of media with or without 1 mM IPTG. ABS600 was measured at different times during cell growth. Applied concentration of specific carbon sources: 0.4% glycerol, 0.8% sodium succinate hexahydrate, 0.2% L-fucose, 2 mM N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), 0.2% D-sorbitol, 0.2% D-xylose, and 60 mM L-lactic acid. Results are representative of two independent experiments. See Figure S2 for growth data for extended time periods, for media lacking casamino acids, and for strains containing a deletion of Spot 42 target genes.

CRP and Spot 42 are components of a multi-output feedforward loop

To begin exploring how sRNAs participate in regulatory networks, we investigated how the confirmed targets of Spot 42 are regulated at the transcriptional level. We found evidence suggesting that at least 8 out of the 16 identified genes are transcriptionally activated by CRP (Table 1). The evidence includes the presence of potential CRP binding sites, in vitro binding assays, and the requirement for CRP for transcription initiation (Table S1). Integrating the fact that CRP represses the transcription of Spot 42 (Polayes et al., 1988; Sahagan and Dahlberg, 1979b), CRP and Spot 42 appear to participate in a feedforward loop that regulates the expression of multiple genes – what is called a multi-output feedforward loop (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Steady-state behavior of the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop.

(A) CRP and Spot 42 participate in a multi-output coherent feedforward loop. CRP positively regulates target expression directly at the transcriptional level and indirectly by repressing Spot 42. Mutations were introduced into the wild type SPA fusion strain (wt) that reduce the loop to direct regulation by CRP (Δspf) or eliminate regulation by both CRP and Spot 42 (Δspf Δcrp). (B) Results from quantitative western blot analysis for srlA-SPA strains. (C) Results from quantitative western blot analysis for fucI-SPA strains. For both B and C, strains were grown in LB or LB containing 0.2% glucose. Northern blot analysis was used to detect the levels of Spot 42. GroEL and 5S RNA served as loading controls. Results are representative of two independent experiments. See Figure S3 for dilution series, for data for cells grown in casamino acid-enriched M9 containing glycerol or casamino acid-enriched M9 containing glycerol and glucose, for β-galactosidase assay results for srlA-lacZ and fucI-lacZ fusion strains, and steady-state data for strains containing a destabilized version of SrlA-SPA.

To investigate the properties of the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop, we focused on two validated targets of Spot 42, srlA and fucI. We chose these genes because of strong evidence that both are transcriptionally activated by CRP; two CRP binding sites upstream of the fucI promoter have been mapped (Chen et al., 1987) and the srlA promoter contains a potential CRP binding site and has been shown to require CRP for transcription initiation (Yamada and Saier, 1988; Zheng et al., 2004) (Table S1). To effectively measure the protein output of this feedforward loop, we fused SPA – a composite peptide tag containing three FLAG epitopes – to the 3′ end of the genomic copy of srlA or fucI (Zeghouf et al., 2004).

Spot 42 can reduce leaky expression under catabolite repression

We first evaluated how the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop regulates the expression of target genes under steady-state conditions. In addition to each wild type strain containing the full feedforward loop (wt), two mutant strains were generated with reduced loops: one reduced to direct regulation by CRP through deletion of spf (Δspf) and another with the entire loop disrupted through deletion of both spf and crp (Δspf Δcrp) (Figure 5A). Strains were grown in LB to activate CRP or in LB and glucose to deactivate CRP since the Δcrp strains showed no growth in casamino acid-enriched M9 in the absence of glucose. Quantitative western blot analysis then was performed to measure the relative levels of SrlA-SPA and FucI-SPA under each experimental condition (Figure 5B,C and S3A,B).

This analysis showed that glucose reduced SrlA-SPA protein levels ~60-fold in the wt strain (Figure 5B). In the Δspf strain, glucose only reduced protein levels ~10-fold, consistent with a loss of Spot 42-mediated repression. Further deletion of crp eliminated the detectable expression of SrlA-SPA, showing that CRP is required for srlA transcription as observed previously (Yamada and Saier, 1988). We obtained similar results when the wt and Δspf strains were grown in casamino acid-enriched M9 containing glycerol (Figure S3C). We also obtained comparable results using an srlA-lacZ fusion, where glucose reduced fusion levels 61-fold in the wt strain and 37-fold in the Δspf strain (Figure S3E). These results suggest that Spot 42 acts to reduce leaky expression of srlA in the presence of glucose.

Glucose reduced FucI-SPA protein levels ~3-fold in the wt strain. In the Δspf strain, glucose also reduced FucI-SPA levels ~3-fold. Further deletion of crp reduced protein levels in the presence and absence of glucose, where protein levels were slightly lower in the presence of glucose likely due to faster growth. We obtained similar results when the wt and Δspf strains were grown in casamino acid-enriched M9 containing glycerol (Figure S3D). We also tested a fucI-lacZ fusion, where glucose reduced fusion levels 6.2-fold in the wt strain and 4.7-fold in the Δspf strain (Figure S3F). This small difference in repression by glucose would be difficult to detect by quantitative western blot analysis. Overall, our steady-state results indicate that, as part of the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop, Spot 42 can reduce leaky expression under repressing conditions.

Spot 42 influences the dynamics of catabolite repression

Coherent feedforward loops comprised of transcription regulators can confer altered regulatory dynamics in comparison to direct regulation, as predicted by computational modeling and observed in multiple experimental systems (Kalir et al., 2005; Mangan and Alon, 2003; Mangan et al., 2003). To examine the regulatory dynamics conferred by the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop, we measured how quickly SrlA-SPA and FucI-SPA levels change after CRP is activated or deactivated. The deactivation of CRP was achieved by growing cells in casamino acid-enriched M9 containing glycerol and adding glucose, while the activation of CRP was achieved by growing cells in casamino acid-enriched M9 containing glycerol and glucose and adding cAMP.

Under conditions of CRP deactivation, the deletion of spf delayed gene repression (Figure 6, S4). For both SrlA-SPA and FucI-SPA, the addition of glucose had a negligible effect on protein levels over the first ~30 min (Figure 6A,C and S4E,G). After this time interval, protein levels in the wt strain began to decline while protein levels in the Δspf strain required an additional ~60 min before declining. The difference in the dynamics of gene repression between the wt and Δspf strains cannot be attributed to a difference in the growth rate (Figure S4I,J). In support of Spot 42 contributing to gene repression after ~30-min, Spot 42 reached maximal expression after ~20 min following glucose addition (Figure S4K,M). Western blotting results were confirmed through two independent experiments, although the results for FucI-SPA were more prone to variability due to the smaller change in protein levels following glucose addition. These results show that, in the context of the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop, Spot 42 acts to accelerate the repression of target genes.

Figure 6. Regulatory dynamics of the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop.

(A) Time course for SrlA-SPA levels following deactivation of CRP. srlA-SPA strains containing the full loop (wt) or the loop reduced to direct regulation by CRP (Δspf) were grown in casamino acid-enriched M9 containing 0.4% glycerol in multiple tubes and 0.2% glucose was added to each tube at the indicated time prior to harvesting the cultures. Normalized protein levels calculated from quantitative western blot analysis were rescaled to span 0 to 100. (B) Time course for SrlA-SPA levels following activation of CRP. wt and Δspf strains were grown in casamino acid-enriched M9 containing 0.4% glycerol and 0.2% glucose in multiple tubes and 10 mM cAMP was added to each tube at the indicated time prior to harvesting the cultures. (C) Time course for FucI-SPA levels following deactivation of CRP. fucI-SPA strains containing the full loop (wt) or the loop reduced to direct regulation by CRP (Δspf) were grown as described in A. (D) Time course for FucI-SPA levels following activation of CRP. wt and Δspf strains were grown as described in B. Results are representative of three independent experiments. See Figure S4 for dilution series, for an independent set of time course data, for growth rates of the srlA-SPA and fucI-SPA strains, and for time course data for strains expressing a destabilized version of SrlA-SPA.

Under conditions of CRP activation, the deletion of spf accelerated gene activation (Figure 6, S4). For SrlA-SPA, the addition of cAMP resulted in a rapid increase in protein levels that peaked at ~45 min for the wt strain and ~20 min for the Δspf strain (Figure 6B, S4F). For FucI-SPA, the addition of cAMP also resulted in a rapid increase in protein levels that peaked at ~30 min for the wt strain and ~10 min for the Δspf strain (Figure 6D, S4H). In support of Spot 42 contributing to the delay in gene activation over an ~30-min time interval, Spot 42 levels declined over ~20 min following the addition of cAMP (Figure S4L,M). These results suggest that, in the context of the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop, Spot 42 acts to delay the activation of target genes.

We also measured the steady-state behavior and dynamics of the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop using a destabilized version of SrlA-SPA. A frameshift mutation was introduced into the SrlA binding partner SrlE, which reduced the half-life of SrlA-SPA to ~2 min (data not shown). Quantitative western blot analysis showed that the stabilized and destabilized versions of SrlA-SPA behaved similarly under steady-state conditions (Figure 5B, S3G) and following the addition of cAMP (Figure 6B, S4O). Compared to the stabilized version of SrlA-SPA, the addition of glucose resulted in a much more rapid decrease in destabilized SrlA-SPA levels for the wt and Δspf strains. However, destabilized SrlA-SPA levels rebounded ~30 min after glucose addition for the Δspf strain but only partially rebounded for the wt strain, consistent with the repressive role of Spot 42 (Figure S4N).

Altogether, our results suggest that inclusion of Spot 42 in the CRP-Spot 42 feedforward loop can affect the dynamics of target gene regulation in two ways: (i) accelerate gene repression when the preferred carbon source appears and (ii) delay gene activation when the preferred carbon source disappears.

DISCUSSION

Physiological role of Spot 42

In this study we identified and validated numerous targets of the Hfq-binding sRNA Spot 42 in addition to the previously known target galK. The identified targets are involved in many aspects of cellular metabolism including central and secondary metabolism, oxidation of NADPH, and the uptake and catabolism of diverse non-preferred carbon sources. We also showed that Spot 42 overexpression reduced growth on several non-preferred carbon sources transported or metabolized by the identified gene targets. These growth phenotypes build on the previous observation that overexpression of Spot 42 reduces growth on succinate (Rice and Dahlberg, 1982). The growth phenotype on succinate may be associated with some of the target genes identified by microarray analysis or genes regulated by Spot 42 at the level of translation not detected by the microarrays. Taken together, these results suggest that Spot 42 makes multiple contributions to catabolite repression.

A previous study revealed that different sugar transport and catabolism genes show complex transcriptional responses to glucose and their respective carbon source under steady-state conditions, despite sharing similar regulatory schemes (Kaplan et al., 2008). We found that Spot 42 regulates numerous transport and catabolism genes that also respond to glucose and other specific carbon sources. Among these genes are a few that were investigated by Kaplan et al (fucI, galK). Thus, post-transcriptional regulation of metabolic genes introduces yet another layer of complexity in the cellular responses to changing nutrient conditions that was not considered in previous studies.

Feedforward loops that incorporate sRNAs

We found that Spot 42 participates with the global regulator CRP in a coherent feedforward loop that regulates multiple genes. This loop is comprised of three regulatory interactions: CRP represses Spot 42, CRP activates target genes, and Spot 42 represses target genes. One possible contribution of this feedforward loop as shown for the regulation of srlA and fucI is reducing leaky gene expression under steady-state repressing conditions. By reducing the leaky expression of multiple genes unnecessary for glucose catabolism, Spot 42 could help divert metabolic resources toward cell growth and the consumption of glucose.

Reduced leakiness could be a considerable benefit of other coherent feedforward loops, yet this property has been rarely discussed. One explanation is that coherent feedforward loops have been studied primarily in the context of transcriptional regulation. Here, two transcription regulators bind a single promoter in order to regulate expression of the downstream gene. Regulation often is described as requiring both regulators to bind the promoter (A AND B to regulate C) or at least one regulator to bind the promoter (A OR B to regulate C) (Alon, 2007). For either mode of co-regulation, gene expression is either ON or OFF depending on the combination of regulators present. When the feedforward loop is composed of a transcription regulator and an sRNA, regulation occurs under two different mechanisms—transcription and post-transcription/translation. By separating the mechanism of regulation, both regulators can influence gene expression independently and subsequently reduce leaky expression.

We found that the CRP-Spot 42 coherent feedforward loop also showed altered regulatory dynamics in comparison to direct regulation by CRP. Transcriptional coherent feedforward loops with the same configuration as the CRP-Spot 42 loop have been predicted to show a delay when the loop is activated but similar dynamics when the loop is deactivated (Mangan and Alon, 2003). Equivalent dynamics were predicted for coherent feedforward loops composed of an sRNA and a transcription regulator (Shimoni et al., 2007). While our results revealed a delay when CRP was activated, our results also revealed a faster decrease in protein levels when CRP was deactivated (Figure 6). The faster decrease in protein levels may be attributed to Spot 42 inducing the degradation or translational repression of the srlA and fucI mRNAs. The ability to accelerate gene repression may allow cells to adapt more rapidly to new environmental conditions such as the presence of glucose. This ability is not associated with feedforward loops incorporating transcription factors, highlighting one potential advantage of sRNAs over proteins.

There is compounding evidence that other bacterial sRNAs besides Spot 42 participate in feedforward loops. The sRNAs MicC and MicF both appear to form coherent feedforward loops with the sensory regulator OmpR to control outer membrane protein biosynthesis (Chen et al., 2004; Mizuno et al., 1984; Shimoni et al., 2007). Furthermore, the ongoing identification of gene targets of Hfq-binding sRNAs suggests that additional sRNAs participate in feedforward loops with their transcription regulator. For example, the genes mqo, sodA, yebZ, and yobA were found to be repressed by the anaerobically-induced sRNA FnrS by microarray analysis and the promoters of these genes contain potential binding sites for the FnrS regulator FNR (Boysen et al., 2010; Durand and Storz, 2010). As a second example, the sdh operon is directly regulated by the iron-responsive sRNA RyhB and the promoter of this operon contains a potential binding site for the RyhB regulator Fur (Massé and Gottesman, 2002; Zhang et al., 2005). Finally, the genes gabD, modC, and fepA were identified by microarray analysis following overexpression of the CRP-activated sRNA CyaR (De Lay and Gottesman, 2009). A CRP binding site was mapped in the promoter of gabD and is required for transcription (Germer et al., 2001; Marschall et al., 1998), while the promoters of modC and fepA each contain a potential CRP binding site (Zhang et al., 2005; Zheng et al., 2004). Thus, the feedforward loop may represent a prevalent regulatory circuit that includes base pairing sRNAs. It would be interesting to test if these sRNAs participate in the proposed feedforward loops and, if so, to determine how these loops contribute to the response to changes in environmental conditions.

The inclusion of base pairing sRNAs in feedforward loops is similar to that observed for microRNAs (miRNAs), the regulatory counterparts to base pairing sRNAs in most eukaryotes (Reviewed in Carthew and Sontheimer, 2009). Many miRNAs appear to participate in coherent feedforward loops within developmental circuits (Hornstein and Shomron, 2006; Tsang et al., 2007). The miRNA-containing feedforward loops are hypothesized to reduce leaky expression of developmental genes and thus maintain the developmental state of the cell (Hornstein and Shomron, 2006). A similar reduction in leaky expression also was achieved with an engineered coherent feedforward loop comprised of a transcription repressor and a synthetic miRNA (Deans et al., 2007). Although recent studies have focused on the regulatory contributions of miRNAs in feedforward loops under steady-state conditions, our work demonstrates that the dynamics of these feedforward loops also may be influenced by the inclusion of regulatory RNAs. Thus, sRNAs in bacteria and eukaryotes may play key roles in shaping the steady-state behavior and dynamics of signaling and developmental pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid and strain construction

The plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S3. The bacterial strains used in this study are all derivatives of E. coli K-12 MG1655 and are listed in Table S3. Plasmid and strain construction is described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Growth conditions

All strains were grown by shaking at 250 RPM at 37°C unless otherwise noted. Strains were grown in Luria-Bertani media (LB) or in 1× M9 salts supplemented with 10 μg/ml thiamine, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and 0.2% casamino acids (M9). Cell density was obtained by measuring the ABS600 using an Ultrospec 3000 UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Pharmacia Biotech).

RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated using the hot phenol extraction procedure (Aiba et al., 1981). The concentration of RNA following ethanol precipitation was determined using a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

Microarray analysis

NM525 cells harboring pBRplac or pSpot42 were grown in LB to an ABS600 of ~0.4 and treated with 1 mM IPTG. After 7 min, total RNA was isolated as described above. cDNA preparation and hybridization to the Genechip E. coli Genome 2.0 array (Affymetrix) was conducted as described previously (Durand and Storz, 2010). The complete microarray data set from the three independent experiments was deposited in NCBI GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE24875).

Northern blot analysis

Northern blot analysis was conducted as described previously (Durand and Storz, 2010). The RNA Millenium Marker (Ambion) was used as a size marker on the agarose gels and the Perfect Mark RNA Marker (Novagen) was used as a size marker on the polyacrylamide gels.

5′ RACE analysis

5′ RACE was performed on srlA and sthA generally as described previously (Mandin and Gottesman, 2009). See the Supplemental Experimental Procedures for further details.

β-galactosidase assays

Three colonies from each transformed strain were inoculated into separate tubes containing LB and grown overnight. Overnight cultures were diluted into 3 ml of LB to an ABS600 of 0.01 and grown to an ABS600 of ~0.1 and either 0.2% arabinose or 0.2% arabinose with 1 mM IPTG was added to each culture. After 1 h, cultures were subjected to β-galactosidase assays as described previously (Miller, 1972).

Quantitative western blot analysis

For the steady-state measurements, overnight cultures were diluted to an ABS600 of 0.01 in the same type of media and grown until an ABS600 of 0.4 – 0.6. For the dynamic measurements, overnight cultures were diluted to an ABS600 of 0.01 into 9 or 10 tubes containing the same type of media and grown to an ABS600 of 0.4 – 0.6. At the indicated time prior to harvesting the cells, 0.2% glucose (CRP deactivated) or 10 mM cyclic AMP (CRP activated) was added to each tube. Supplementing the media with cAMP rapidly activates CRP even in the presence of glucose as shown previously (Kaplan et al., 2008; Mangan et al., 2003).

To harvest the cells, 1 ml of each culture was mixed with 0.4 ml of ice-cold 1X PBS, and cells were pelleted and frozen on dry ice. Total protein from an equal number of cells was resolved on a Novex 15-well 16% tricine gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to a 0.45 μm pore nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen). The SPA tag was detected using the mouse monoclonal ANTI-FLAG M2-alkaline phosphatase antibody (Sigma) with the Lumi-Phos WB reagent (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The loading control GroEL was detected with the mouse anti-GroEL monoclonal antibody (Abcam) and the Immunopure goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (Pierce) with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Protein levels were calculated using the ImageJ software package (Rasband, 1997–2009). Background intensity measured directly below each band was subtracted and a dilution series in the same gel was used to calculate relative protein levels. For each time point, relative protein levels of the SPA fusion were divided by relative protein levels of the loading control GroEL to yield normalized protein levels. For the dynamic measurements, normalized protein levels were rescaled to span 0 to 100 in order to directly compare the dynamics between strains.

Detailed methods

See Supplemental experimental procedures for complete details on all methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Fozo, R. Fuchs, S. Gottesman, M. Goulian, E. Hobbs, B. Janson, M. Thomason, and L. Waters for their comments on this manuscript and S. Durand for technical assistance. P. Mandin kindly provided the E. coli strain PM1205 and the plasmid pSpot42 and N. Majdalani kindly provided the E. coli strain NM525. Work carried out in the laboratory of G.S. is supported by the Intramural Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. C.B. is a Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aiba H, Adhya S, de Crombrugghe B. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:11905–11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon U. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansong C, Yoon H, Porwollik S, Mottaz-Brewer H, Petritis BO, Jaitly N, Adkins JN, McClelland M, Heffron F, Smith RD. Global systems-level analysis of Hfq and SmpB deletion mutants in Salmonella: implications for virulence and global protein translation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisel CL, Storz G. Base pairing small RNAs and their roles in global regulatory networks. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:866–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boysen A, Møller-Jensen J, Kallipolitis B, Valentin-Hansen P, Overgaard M. Translational regulation of gene expression by an anaerobically induced small non-coding RNA in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10690–10702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.089755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zhang A, Blyn LB, Storz G. MicC, a second small-RNA regulator of Omp protein expression in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6689–6697. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6689-6697.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YM, Zhu Y, Lin EC. The organization of the fuc regulon specifying L-fucose dissimilation in Escherichia coli K12 as determined by gene cloning. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;210:331–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00325702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang BY, Chen TC, Pai CH, Chou CC, Chen HH, Ko TP, Hsu WH, Chang CY, Wu WF, Wang AH, et al. Protein S-thiolation by Glutathionylspermidine (Gsp): the role of Escherichia coli Gsp synthetase/amidase in redox regulation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25345–25353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lay N, Gottesman S. The Crp-activated small noncoding regulatory RNA CyaR (RyeE) links nutritional status to group behavior. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:461–476. doi: 10.1128/JB.01157-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans TL, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. A tunable genetic switch based on RNAi and repressor proteins for regulating gene expression in mammalian cells. Cell. 2007;130:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand S, Storz G. Reprogramming of anaerobic metabolism by the FnrS small RNA. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:1215–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germer J, Becker G, Metzner M, Hengge-Aronis R. Role of activator site position and a distal UP-element half-site for sigma factor selectivity at a CRP/H-NS-activated σS-dependent promoter in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:705–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görke B, Stülke J. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:613–624. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornstein E, Shomron N. Canalization of development by microRNAs. Nat Genet. 2006;38(Suppl):S20–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalir S, Mangan S, Alon U. A coherent feed-forward loop with a SUM input function prolongs flagella expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Syst Biol. 2005;1:2005–0006. doi: 10.1038/msb4100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S, Bren A, Zaslaver A, Dekel E, Alon U. Diverse two-dimensional input functions control bacterial sugar genes. Mol Cell. 2008;29:786–792. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandin P, Gottesman S. A genetic approach for finding small RNAs regulators of genes of interest identifies RybC as regulating the DpiA/DpiB two-component system. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:551–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan S, Alon U. Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11980–11985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133841100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan S, Zaslaver A, Alon U. The coherent feedforward loop serves as a sign-sensitive delay element in transcription networks. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall C, Labrousse V, Kreimer M, Weichart D, Kolb A, Hengge-Aronis R. Molecular analysis of the regulation of csiD, a carbon starvation-inducible gene in Escherichia coli that is exclusively dependent on σS and requires activation by cAMP-CRP. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:339–353. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massé E, Gottesman S. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4620–4625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032066599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Milo R, Shen-Orr S, Itzkovitz S, Kashtan N, Chklovskii D, Alon U. Network motifs: simple building blocks of complex networks. Science. 2002;298:824–827. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5594.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Chou MY, Inouye M. A unique mechanism regulating gene expression: translational inhibition by a complementary RNA transcript (micRNA) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1966–1970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller T, Franch T, Hojrup P, Keene DR, Bachinger HP, Brennan RG, Valentin-Hansen P. Hfq: a bacterial Sm-like protein that mediates RNA-RNA interaction. Mol Cell. 2002a;9:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller T, Franch T, Udesen C, Gerdes K, Valentin-Hansen P. Spot 42 RNA mediates discoordinate expression of the E. coli galactose operon. Genes Dev. 2002b;16:1696–1706. doi: 10.1101/gad.231702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polayes DA, Rice PW, Garner MM, Dahlberg JE. Cyclic AMP-cyclic AMP receptor protein as a repressor of transcription of the spf gene of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3110–3114. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3110-3114.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband WS. ImageJ. Bethesda, MD: U. S. National Institutes of Health; 1997–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rice PW, Dahlberg JE. A gene between polA and glnA retards growth of Escherichia coli when present in multiple copies: physiological effects of the gene for spot 42 RNA. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:1196–1210. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.3.1196-1210.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahagan BG, Dahlberg JE. A small, unstable RNA molecule of Escherichia coli: spot 42 RNA. I. Nucleotide sequence analysis. J Mol Biol. 1979a;131:573–592. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahagan BG, Dahlberg JE. A small, unstable RNA molecule of Escherichia coli: spot 42 RNA. II. Accumulation and distribution. J Mol Biol. 1979b;131:593–605. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen-Orr SS, Milo R, Mangan S, Alon U. Network motifs in the transcriptional regulation network of Escherichia coli. Nat Genet. 2002;31:64–68. doi: 10.1038/ng881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni Y, Friedlander G, Hetzroni G, Niv G, Altuvia S, Biham O, Margalit H. Regulation of gene expression by small non-coding RNAs: a quantitative view. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:138. doi: 10.1038/msb4100181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittka A, Lucchini S, Papenfort K, Sharma CM, Rolle K, Binnewies TT, Hinton JC, Vogel J. Deep sequencing analysis of small noncoding RNA and mRNA targets of the global post-transcriptional regulator, Hfq. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang J, Zhu J, van Oudenaarden A. MicroRNA-mediated feedback and feedforward loops are recurrent network motifs in mammals. Mol Cell. 2007;26:753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanowski ML, Stauffer LT, Stauffer GV. The gcvB gene encodes a small untranslated RNA involved in expression of the dipeptide and oligopeptide transport systems in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:856–868. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J. A rough guide to the non-coding RNA world of Salmonella. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters LS, Storz G. Regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Cell. 2009;136:615–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Saier MH., Jr Positive and negative regulators for glucitol (gut) operon expression in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:569–583. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh JN, Steenberg CD, Bois JS, Wolfe BR, Pierce MB, Khan AR, Dirks RM, Pierce NA. NUPACK: Analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. J Comput Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcc.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeghouf M, Li J, Butland G, Borkowska A, Canadien V, Richards D, Beattie B, Emili A, Greenblatt JF. Sequential Peptide Affinity (SPA) system for the identification of mammalian and bacterial protein complexes. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:463–468. doi: 10.1021/pr034084x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A, Wassarman KM, Rosenow C, Tjaden BC, Storz G, Gottesman S. Global analysis of small RNA and mRNA targets of Hfq. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1111–1124. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Gosset G, Barabote R, Gonzalez CS, Cuevas WA, Saier MH., Jr Functional interactions between the carbon and iron utilization regulators, Crp and Fur, in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:980–990. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.3.980-990.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D, Constantinidou C, Hobman JL, Minchin SD. Identification of the CRP regulon using in vitro and in vivo transcriptional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5874–5893. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.