Abstract

Quorum-sensing (QS), the regulation of bacterial gene expression in response to changes in cell density, involves pathways that synthesize signaling molecules (auto-inducers). The luxS/AI-2-mediated QS system has been identified in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Bacillus anthracis, the etiological agent of anthrax, possesses genes involved in luxS/AI-2-mediated QS, and deletion of luxS in B. anthracis Sterne strain 34F2 results in inhibition of AI-2 synthesis and a growth defect. In the present study, we created a ΔluxS B. anthracis strain complemented in trans by insertion of a cassette, including luxS and a gene encoding erythromycin resistance, into the truncated plcR regulator locus. The complemented ΔluxS strain has restored AI-2 synthesis and wild-type growth. A B. anthracis microarray study revealed consistent differential gene expression between the wild-type and ΔluxS strain, including downregulation of the B. anthracis S-layer protein gene EA1 and pXO1 virulence genes. These data indicate that B. anthracis may use luxS/AI-2-mediated QS to regulate growth, density-dependent gene expression and virulence factor expression.

Keywords: luxS, virulence, quorum-sensing, microarray, furanone

Introduction

Bacillus anthracis is a gram-positive, non-motile, rod-shaped bacterium that is the etiological agent of anthrax.1–3 The virulent nature of B. anthracis is attributed to two large plasmids, the 181.6 kb pXO1 and the 96.2 kb pXO2, that encode primary pathogenetic factors, including toxin production and capsule formation, respectively.4–12 The three proteins that comprise the two B. anthracis toxins are lethal factor (LF), edema factor (EF) and protective antigen (PA). In two different combinations, these three proteins comprise the lethal toxin (PA + LF) and the edema toxin (PA + EF).5,7,9–18 Maximum production of toxins occurs during the transition from log to the stationary phase of growth, suggesting growth phase-regulation of expression.19

Quorum-sensing (QS) is a process by which bacteria regulate the expression of density- and growth phase-dependent genes.20–25 QS involves the synthesis, release and detection of small signaling molecules, termed auto-inducers. The auto-inducer concentration is directly correlated to the bacterial population. Utilization of QS systems is critical for the regulation of virulence gene expression in many pathogenic bacteria. Inhibition of QS circuits by QS antagonists, such as the halogenated furanones from the red-sea alga Delisea pulchra, offers an attractive method for inhibiting bacterial pathogens.26–36

B. anthracis synthesizes AI-2 or an AI-2-like auto-inducer molecule that induces bioluminescence in the Vibrio harveyi bioassay.37 Furthermore, analysis of the B. anthracis genome indicated the presence of a gene, luxS, which typically is involved in QS. Disruption of luxS resulted in the inability of B. anthracis to synthesize a functional AI-2 or AI-2-like molecule recognizable in the V. harveyi bioassay, and in a defect in growth in vitro for the B. anthracis luxS mutant.37 These data suggest that B. anthracis may utilize the luxS/AI-2 QS system to regulate growth as well as density-dependent gene expression.

In the present report, we characterize the differential gene expression of Bacillus anthracis strains 34F2, 34F2ΔluxS and 34F2luxS:comp. To further characterize the role of QS in B. anthracis, by microarray analysis we analyzed B. anthracis gene expression in wild-type cells grown in the presence or absence of halogenated furanones. Finally we utilize a custom tiled genome Affymetrix array to identify possible small RNAs differentially expressed in the luxS mutant compared to the wildtype.

Results

Complementation of AI-2 deficiency.

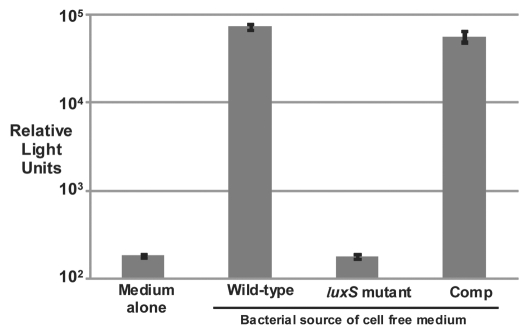

Cell-free medium (CFM) was collected from B. anthracis strains 34F2, 34F2:ΔluxS and 34F2ΔluxS:comp for assessment in the Vibrio harveyi BB170 bioluminescence assay. The AI-2 bioassay utilizes a deficiency in the AI-1 sensor in V. harveyi strain BB170. Without the luxN AI-1 encoded sensor, strain BB170 only exhibits bioluminescence in response to AI-2 or an AI-2-like molecule. Growth of strain BB170 overnight, followed by dilution 1:10,000 (to yield low cell density), reduces the level of endogenous AI-2 below the threshold required for luminescence. In this experimental system, the addition of exogenous AI-2 from bacteria possessing luxS function can restore the bioluminescence phenotype of the BB170 cells. As a negative control, the V. harveyi reporter strain BB170 was incubated with sterile cell-free medium (CFM) alone, and as a positive control, CFM from a high-density culture of strain BB170 was used (Fig. 1). Addition of sterile CFM to cells of BB170 served as the standard for baseline luminescence, whereas, as expected, addition of CFM from the high-density BB170 culture induced a >100-fold increase in luminescence. Additional controls included were CFM from B. anthracis strain 34F2ΔluxS (negative control) and B. anthracis 34F2 (positive control). CFM from B. anthracis strain 34F2ΔluxS:comp exhibits AI-2 activity comparable to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 1). These data demonstrate that the luxS chromosomal complementation fully restored AI-2 production that was deficient in B. anthracis strain 34F2ΔluxS (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Induction of bioluminescence in V. harveyi reporter strain by CFM from B. anthracis cells. V. harveyi strain BB170 only upregulates the expression of the lux operon [measured as relative light units (RLU)], when AI-2 or AI-2-like molecules are present in its milieu. Cell free medium (CFM) obtained from AI-2-synthesizing bacteria can induce expression of the bioluminescence-generating luxCDABE operon in BB170. (A) In the experiments shown, CFM from 5-h cultures of B. anthracis strains 34F2 and 34F2ΔluxS and sterile CFM alone were used as positive and negative controls. The baseline is the value when uninoculated (sterile) CFM alone at 5 h were used. Each bar represents the mean (±SD) of triplicate experiments. Compared to the negative and positive controls, 34F2ΔluxS:comp showed restored AI-2 activity compared to wild-type 34F2. (B) In the experiment shown, CFM from 5-h cultures of wild-type 34F2 and 34F2ΔluxS:comp were serially diluted 1:1, 1:10 and 1:100. Each bar represents the mean (±SD) of triplicate experiments.

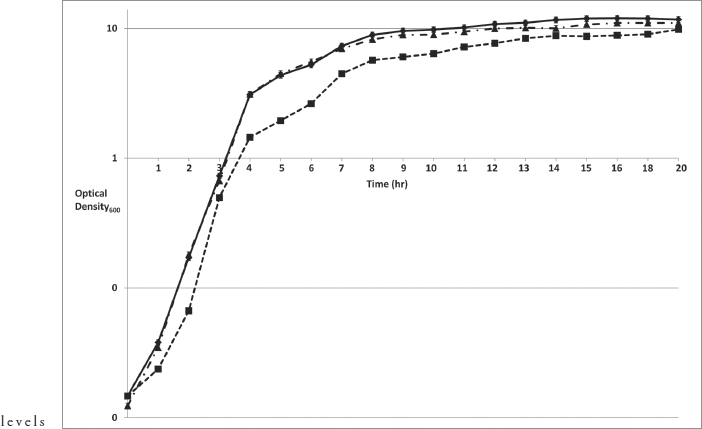

Complementation of the growth defect in B. anthracis strain 34F2ΔluxS.

When cultured in liquid medium, B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS exhibited a moderate, but reproducible, growth defect compared to wild-type B. anthracis 34F2.37 To determine whether the growth defect was directly related to the deletion of luxS, we compared the growth of B. anthracis wild-type strain 34F2, strain 34F2ΔluxS, and the 34F2ΔluxS:comp strain. As determined by triplicate cell densities and based on OD600, the 34F2ΔluxS:comp strain showed restored growth compared to the ΔluxS strain (Fig. 2). These data suggest that luxS/AI-2-mediated quorum sensing is involved in regulating metabolic functions in B. anthracis under aerobic conditions. Based on these findings, we sought to characterize the growth defect in 34F2ΔluxS by examining the transcriptional profile of the 34F2ΔluxS strain compared to the wild type parental strain.37

Figure 2.

Growth rate analysis of B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS:comp. B. anthracis strains 34F2, 34F2ΔluxS, and 34F2ΔluxS:comp were grown overnight and diluted in sterile BHI media to an optical density (OD600) of ≈0.01. Cell growth was monitored, CFM removed and passed through a 0.2 µm filter for use in the V. harveyi bioassay. The graph represents the mean (±SD) of triplicate experiments performed on the same day. Solid line with filled diamonds represent strain 34F2, dotted line with filled squares represent strain 34F2ΔluxS and short dash line with filled triangles represents strain 34F2ΔluxS:comp.

Differential gene expression of a B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS strain grown aerobically.

To identify genes regulated by the luxS/AI-2 QS system, B. anthracis microarrays were utilized. Total RNA was isolated from B. anthracis strains 34F2 and 34F2ΔluxS grown in BHI in the absence of sodium bicarbonate. Isolated RNA samples were hybridized to spotted B. anthracis array slides and analyzed using TM4 software (www.tm4.org).38 Significance of microarray (SAM) analysis of array data revealed that 576 genes were differentially expressed in the 34F2ΔluxS strain, compared to the wild-type 34F2 strain based on a false discovery cutoff of 7%. Select upregulated genes ≥2-fold (Table 2) and downregulated genes ≥2-fold (Table 3) are listed. Genes that were not downregulated ≥2-fold, but are in the middle of a presumed operon in which other genes have a ≥2-fold change are included. Among the genes downregulated in the 34F2ΔluxS strain are the luxS gene (as expected), the S-layer virulence gene EA1, encoding putative S-layer proteins, and genes involved in phosphotransferase systems (PTS) (Table 3). Genes that were upregulated ≥2-fold included those encoding a phospholipase C, a bacitracin protease and resistance protein (Table 2). These data suggest that luxS/AI-2 is involved in regulating peptide transport and S-layer expression. To further elucidate impact of luxS/AI-2 on B. anthracis gene expression we performed an analysis of down and upregulated genes to determine cellular and functional roles. Analysis of downregulated genes revealed that a significant portion are involved in energy metabolism (23%) and transport and binding proteins (12.7%), and analysis of upregulated genes revealed a significant portion are involved with cellular processes (18.8%).

Table 2.

B. anthracis chromosomal genes upregulated in the 34F2ΔluxS strain as determined by microarray analysis, sorted by locus

| Locusc | Gene Nameb | 30 mina | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min |

| BA0194 | oligopeptide ABC transporter, oligopeptide-binding protein | 1.42 | 5.03 | 4.44 | 7.67 |

| BA0369 | methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 6.15 | 11.47 | 6.68 | 6.28 |

| BA0558 | methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 12.47 | 11.47 | 11.00 | 9.85 |

| BA0575 | methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 4.86 | 7.16 | 6.45 | 8.51 |

| BA0677 | phospholipase C (plc) | 4.14 | 7.06 | 5.28 | 6.54 |

| BA0682 | hypothetical protein | 3.46 | 5.70 | 7.06 | 6.36 |

| BA0796 | conserved hypothetical protein | 2.20 | 5.39 | 6.82 | 16.56 |

| BA2025 | hypothetical protein | 9.32 | 14.22 | 10.85 | 12.73 |

| BA2114 | RNA polymerase sigma-70 factor, ECF subfamily | 1.17 | 3.61 | 6.82 | 12.21 |

| BA2115 | hypothetical protein | 1.68 | 3.48 | 7.84 | 9.99 |

| BA2363 | transcriptional regulator, ArsR family | 3.78 | 11.63 | 12.38 | 7.67 |

| BA2606 | hypothetical protein | 7.52 | 11.63 | 7.94 | 6.41 |

| BA2732 | RNA polymerase sigma factor SigX, putative | 1.35 | 2.77 | 15.67 | 64.00 |

| BA3029 | succinylornithine transaminase, putative | 1.23 | 4.89 | 7.41 | 7.78 |

| BA3034 | hypothetical protein | 1.55 | 5.06 | 4.23 | 8.22 |

| BA3114 | membrane protein, putative | 13.45 | 10.78 | 7.36 | 11.24 |

| BA3305 | transcriptional regulator, ArsR family | 3.76 | 7.67 | 5.06 | 10.34 |

| BA3405 | ABC transporter, permease protein | 1.28 | 1.83 | 8.57 | 11.63 |

| BA3406 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 0.71 | 2.46 | 6.77 | 18.13 |

| BA3407 | hypothetical protein | 1.08 | 2.22 | 7.11 | 8.28 |

| BA4264 | nitroreductase family protein | 1.52 | 2.81 | 3.97 | 7.16 |

| BA5481 | conserved domain protein | 7.31 | 14.03 | 4.89 | 7.26 |

| BA5628 | iron compound ABC transporter | 1.85 | 4.11 | 3.76 | 7.01 |

Numbers represent fold change over the 120 min time course of the experiments;

Functional annotations were obtained from the B. anthracis complete genome sequence (www.jcvi.org);

Locus based on Ames strain of B. anthracis.

Table 3.

B. anthracis chromosomal genes downregulated in the 34F2ΔluxS strain as determined by microarray analysis, sorted by locus

| Locusc | Gene nameb | 30 mina | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min |

| BA0238 | hypothetical protein | −3.41 | −29.65 | −5.78 | −15.78 |

| BA0239 | hypothetical protein | −3.86 | −22.16 | −5.86 | −19.29 |

| BA0240 | 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (hppD) | NaN | −11.63 | −9.51 | −6.41 |

| BA0509 | formate acetyltransferase (pfl) | −33.13 | −125.37 | −56.89 | −35.51 |

| BA0510 | pyruvate formate-lyase-activating enzyme (pflA) | −1.26 | −23.26 | −36.00 | −21.71 |

| BA0668 | ribose ABC transporter, permease protein (rbsC) | −1.42 | −14.42 | −12.91 | −7.94 |

| BA0669 | ribose ABC transporter, ribose-binding protein (rbsB) | −1.58 | −15.89 | −11.88 | −6.96 |

| BA0887 | S-layer protein EA1 (eag) | −7.26 | −25.63 | −46.85 | −3.97 |

| BA1086 | sugar-binding transcriptional regulator, LacI family | −3.14 | −19.29 | −11.08 | −4.20 |

| BA2125 | respiratory nitrate reductase, alpha subunit (narG) | −6.68 | −4.20 | −52.71 | −42.22 |

| BA2126 | respiratory nitrate reductase, beta subunit (narH) | −1.13 | −3.18 | −29.24 | −17.39 |

| BA2128 | respiratory nitrate reductase, gamma subunit (narI) | −1.25 | −3.12 | −38.59 | −18.13 |

| BA2133 | molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis protein A (narA-1) | −1.84 | −6.36 | −45.25 | −14.83 |

| BA2134 | molybdopterin biosynthesis protein MoeB, putative | −1.07 | −5.06 | −103.97 | −13.55 |

| BA2135 | molybdopterin biosynthesis protein MoeA (moeA-1) | −1.12 | −2.19 | −35.26 | −13.64 |

| BA2136 | molybdopterin converting factor, subunit 2 (moaE-1) | −1.13 | −2.95 | −48.84 | −20.53 |

| BA2137 | molybdopterin converting factor, subunit 1 (moaD-1) | −1.36 | −1.91 | −22.78 | −29.86 |

| BA2138 | nitrate transporter (narK) | −1.24 | −1.92 | −37.53 | −21.11 |

| BA2146 | nitrite reductase [NAD(P)H], large subunit (nirB) | −1.33 | −76.11 | −60.97 | −210.84 |

| BA2267 | alcohol dehydrogenase, zinc-containing | −3.61 | −12.91 | −6.45 | −9.19 |

| BA2295 | acetate CoA-transferase, subunit A (atoD) | −1.01 | NaN | −8.11 | −22.16 |

| BA2350 | carboxyvinyl-carboxyphosphonate phosphorylmutase (yqiQ) | −1.52 | −5.24 | −12.13 | −19.16 |

| BA2547 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | −2.01 | −13.36 | −19.70 | −10.48 |

| BA2548 | acetyl-CoA carboxylase, biotin carboxylase, putative | −1.66 | −7.06 | −17.27 | −9.99 |

| BA2552 | carboxyl transferase domain protein | −1.24 | −16.45 | −11.39 | −10.27 |

| BA3479 | transcriptional regulator, ArsR family | −36.00 | −44.94 | −37.27 | −136.24 |

| BA3481 | hypothetical protein | −38.85 | −315.17 | −137.19 | −69.55 |

| BA3482 | conserved hypothetical protein | −32.67 | −36.00 | −64.45 | −140.07 |

| BA3483 | conserved hypothetical protein | −30.48 | −67.18 | −53.82 | −219.79 |

| BA3663 | anaerobic ribonucleoside-triphosphate reductase | NaN | −14.03 | −4.66 | −9.92 |

| BA5047 | autoinducer-2 production protein LuxS (luxS) | −14.72 | −28.84 | −29.86 | −494.56 |

| BA5696 | superoxide dismutase, Mn (sodA-2) | −1.77 | −7.62 | −14.62 | −7.11 |

Numbers represent fold change over the 120 min time course of the experiments;

Functional annotations were obtained from the B. anthracis complete genome sequence (www.jcvi.org);

Locus based on Ames strain of B. anthracis;

NaN indicates a miss data point.

Closer examination of genes downregulated in B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS strain revealed several operons involved in nitrate/nitrite metabolism (Table 3) when grown either aerobically or in the presence of sodium bicarbonate. Nitrate reduction has three fundamental roles: (1) utilization as a nitrogen source (nitrate assimilation); (2) maintenance of oxidation-reduction balance (nitrate dissimilation), and (3) utilization as a terminal electron acceptor (nitrate respiration).39 In-depth analysis of nitrate/nitrite respiration regulation in B. subtilis revealed the ability of the bacterium to convert nitrate or nitrite to ammonium when grown aerobically.40 The conversion of these nitrogen sources to ammonium is catalyzed by assimilatory nitrate and nitrate reductases. Mutation in nasD, nasE or nasF (assimilatory nitrite reductases) led to growth defects in B. subtilis when glucose was depleted.40 These observations coupled with the transcriptional profile of the 34F2ΔluxS strain, suggests that luxS/AI-2 may play a role in regulating nitrate/nitrite metabolism in B. anthracis, and that the observed growth defect in the luxS mutant is due to the inability to utilize nitrate/nitrite. It is interesting to note that complementation of luxS in B. anthracis strain 34F2ΔluxS did not fully restore the transcriptional expression of the nitrate/nitrite regulon to wildtype (data not shown), suggesting that additional factors may contribute to the growth defect of the luxS mutant, and that luxS/AI-2 quorum-sensing is not the only factor regulating nitrate/nitrite metabolism. To further elucidate the potential role of luxS/AI-2 in nitrate/nitrite metabolism we will make use of inhibitors of AI-2-mediated quorum-sensing.

Differential gene expression of B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS grown with 0.8% sodium bicarbonate.

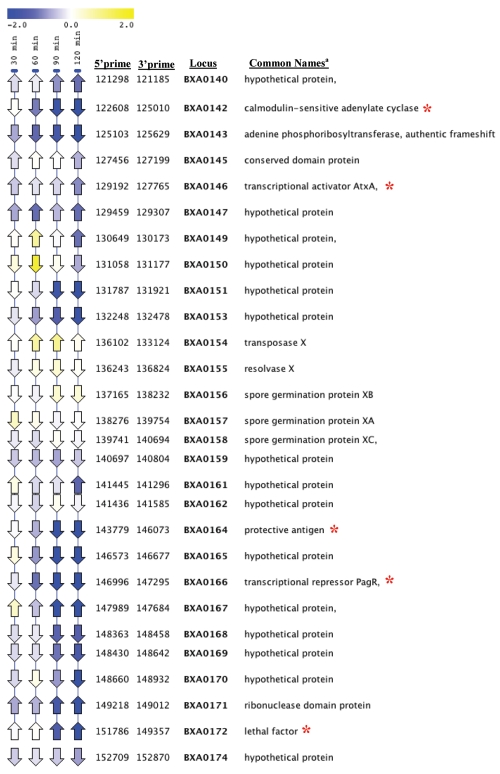

QS has been implicated in the regulation of virulence gene expression for a number of pathogenic bacteria.24,28,30,41–48 To identify genes regulated by the luxS/AI-2 QS system and CO2/bicarbonate, total RNA was isolated from B. anthracis strains 34F2 and 34F2ΔluxS grown in BHI in the presence of 0.8% sodium bicarbonate. CO2/bicarbonate is critical for activation of toxin gene expression in B. anthracis. Isolated RNA samples were hybridized to spotted B. anthracis array slides and analyzed using Spotfinder and TMeV software. Analysis of the microarray data revealed substantial differential expression of virulence genes on plasmid pXO1 in the 34F2ΔluxS strain compared to the parental strain 34F2. Genes downregulated on pXO1 include the protective antigen (pagA), pagR, lethal factor (lef) and the calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase (cya) (Table 4, Fig. 3). Figure 3 demonstrates temporal changes in gene expression within the pathogenicity island on pXO1 in strain 34F2ΔluxS with regard to the downregulation of the toxin components. The virulence regulator atxA was only slightly downregulated in the 34F2ΔluxS strain compared to the wild type, suggesting that luxS/AI-2 influence on expression of the toxin components is regulated by factors in addition to atxA. Analysis of the transcriptional profile of the 34F2ΔluxS complement strain revealed near wildtype levels of toxin components pagA, lef and cya compared to the luxS mutant strain (Table 5). Based on these data, we hypothesize that luxS/AI-2 may play a role in influencing additional regulators that modulate toxin expression.

Table 4.

Select genes downregulated on pXO1 in B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS as determined by microarray analysis, sorted by locus

| Locusc | Gene nameb | 30 mina | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min |

| BXA0142 | calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase (cya) | 1.03 | −2.00 | −3.46 | −4.69 |

| BXA0146 | transcriptional activator AtxA (atxA) | −1.34 | −1.16 | −1.25 | −1.83 |

| BXA0164 | protective antigen (pagA) | −1.02 | −1.53 | −7.21 | −26.17 |

| BXA0165 | hypothetical protein | 1.21 | −1.74 | −7.52 | −20.97 |

| BXA0166 | transcriptional repressor PagR (pagR) | −1.13 | −2.13 | −6.11 | −13.36 |

| BXA0167 | hypothetical protein | 1.36 | −1.39 | −5.70 | −10.27 |

| BXA0168 | hypothetical protein | −1.20 | −1.13 | −2.46 | −2.62 |

| BXA0169 | hypothetical protein | −1.23 | −1.20 | −2.10 | −2.89 |

| BXA0170 | hypothetical protein | −1.24 | 1.16 | −1.71 | −4.23 |

| BXA0171 | ribonuclease domain protein | −1.59 | −1.49 | −2.99 | −7.62 |

| BXA0172 | lethal factor (lef) | −1.02 | 1.05 | −2.71 | −4.92 |

Numbers represent fold change over the 120 min time course of the experiments; Bolded genes indicate genes involved in B. anthracis toxin production or its regulation;

Functional annotations were obtained from the B. anthracis complete genome sequence (www.jcvi.org);

Locus based on Ames strain of B. anthracis.

Figure 3.

Analysis of pXO1 pathogenicity island gene expression in B. anthracis strain 34F2ΔluxS compared to strain 34F2 using Linear Expression Map (LEM) viewer. Time points are indicated at the top of each column. Arrows indicate the direction of gene orientation. The color scale indicates the log2 changes in expression, according to the scale shown above. Locus ID based on B. anthracis Florida strain A2012. aGenes bolded relate to production or regulation of toxins. bRed asterisk indicates virulence genes.

Table 5.

Select virulence genes downregulated on pXO1 in 34F2ΔluxS compared to 34F2luxS:comp

| Locusc | Gene nameb | 120 mina |

| BXA0124 | S-layer protein | −5.16 |

| BXA0142 | calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase | −3.97 |

| BXA0146 | transcriptional activator AtxA | −2.9 |

| BXA0164 | protective antigen | −13.78 |

| BXA0165 | hypothetical protein | −16.83 |

| BXA0166 | transcriptional repressor PagR | −14.66 |

| BXA0172 | lethal factor | −4.32 |

Numbers represent fold change over; Bolded genes indicate genes involved in B. anthracis toxin production or its regulation

Functional annotations were obtained from the B. anthracis complete genome sequence (www.jcvi.org);

Locus based on B. anthracis strain A2012.

Effect of halogenated furanones on B. anthracis gene expression.

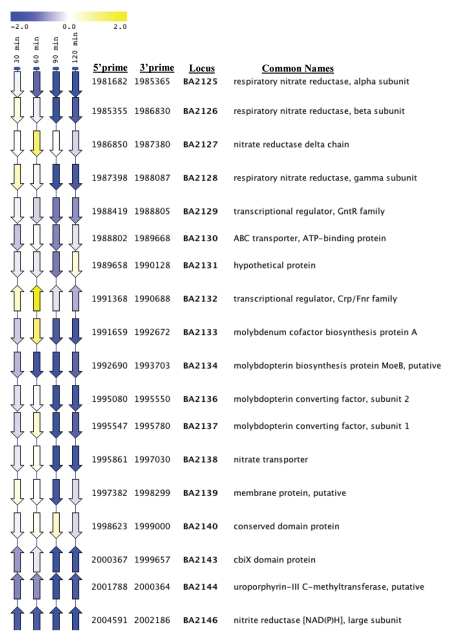

To better understand the mechanism by which B. anthracis may utilize luxS/AI-2-mediated QS to regulate gene expression, we studied the effect of halogenated furanones in microarray experiments. Previous studies showed that halogenated furanones can inhibit AI-2-regulated genes in E. coli without inhibiting bacterial growth. However, our recent data showed that halogenated furanones inhibit B. anthracis growth in a dosedependent manner.30 B. anthracis cultures were grown to mid-log phase and then supplemented with diluent alone (negative control) or diluent with 20 µg/ml of fur-2.30 This concentration of fur-2 was selected due to its ability to inhibit expression of B. anthracis toxin gene promoter: lacZ fusions, and because fur-2 showed no significant toxicity to human THP-1 monocytes at concentrations ≤20 µg/ml (unpublished data). The data reveal that fur-2 can stimulate or inhibit B. anthracis gene expression (Fig. 4). Inhibition and stimulation by fur-2 was not a global event, with only ∼5% of the genome showing ≥3-fold differential expression. Expression of the B. anthracis toxin components (lef and pagA) on pXO1 were significantly downregulated two hours post-exposure to fur-2 (Table 6). These data are consistent with the observation that fur-2 significantly inhibits expression of lacZ fusions to the promoters of the toxin components.30 In addition to the toxin components, furanone treatment of B. anthracis cells inhibited respiratory nitrate systems as mentioned above.

Figure 4.

Analysis of respiratory nitrate genes in strain 34F2ΔluxS compared to strain 34F2 and strain 34F2 exposed to 20 µg/ml of fur-2 using LEM. Time points (left-most 4 columns) and sample (exposure to fur-2 for one hour; right-most column) are indicated at the top of each column. Arrows indicate the direction of gene orientation. The color scale indicates the log2 changes in expression, according to the scale shown above. Locus ID based on B. anthracis strain Ames.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer designation | Nucleotide sequence (5′ → 3′)a |

| P1F | TTTGAACGTGCGATGAAAG |

| P2R | GATTGTGGAACTGATGTAACAG |

| P3F | GCGGATCCATTGAAGAAACTGCTGAAGCTC |

| P4R | GCGGATCCAGGAATAGATGTATATCAGAAC |

| P5F | CGTTAAAGCCTGATGTAAGCA |

| P6R | GGTTACGTGGTTGCTTAC |

| P9F | GCGGATCCTTAAAGTATTATAGCACGACTG |

| P10R | GCTCTACAATATCCAGTGTCGAAACGTC |

| P11F | GCGGTACCTTTGAACGTGCGATGAAAG |

| P12R | GCGGTACCGATTGTGGAACTGATGTAACAG |

| BAluxSF | ATGCATCAGTAGAAAGCTTTG |

| BAluxSR | TTATCCAAATACTTTCTCAAGTTC |

Restriction sites underlined; BamHI (GGATCC) and KpnI (GGTACC).

To determine whether fur-2 was inhibiting genes regulated by the luxS/AI-2 QS system, the differentially expressed genes in cells treated with fur-2 were compared to those differentially expressed in the B. anthracis ΔluxS strain (Tables 2 and 3). Analysis of microarray data revealed that B. anthracis toxin components and respiratory nitrate reductase systems were downregulated under both experimental conditions (Fig. 4). However, fur-2 did not inhibit the expression of luxS directly. These data indicate that fur-2 does not directly inhibit the transcriptional activity of luxS, but may interact with the luxS product at the cellular level. Furthermore, fur-2 inhibits genes that may be regulated by luxS/AI-2 mediated QS in B. anthracis. These data support the hypothesis that luxS/AI-2-mediated QS may play a role in the regulation of the B. anthracis toxin components (pagA, lef and cya) and nitrate/nitrite metabolism.

Analysis of small RNA s in B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS strain.

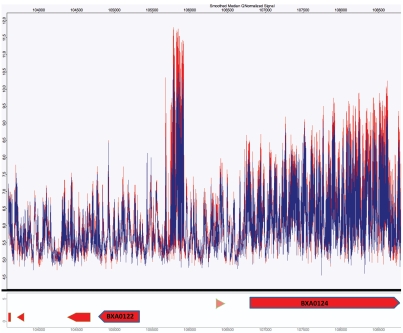

Small RNAs have been implicated in regulating pathways involved in QS.49 To investigate the effect of a luxS mutation on small RNAs in B. anthracis, we utilized an Affymetrix custom genome tiled array. This platform permitted us to investigate the transcriptional activity of small and antisense RNAs. Analysis of pXO1 revealed several regions on the virulence plasmid demonstrating differential transcriptional activity in intergenic regions (Fig. 5). The intergenic region between locus BXA0122 and BXA0124 had substantial transcriptional activity. Furthermore, a comparison of the 34F2ΔluxS strain with the wildtype demonstrated a lower transcriptional profile, suggesting that luxS/AI-2 may play a role in regulating the transcriptional activity of small RNAs in B. anthracis. However, to better understand the regulatory network of luxS/AI-2-mediated QS, additional experiments will be necessary.

Figure 5.

Analysis of small non-coding RNA of strain 34F2ΔluxS compared to strain 34F2 using an Affymetrix tiled array. A select region (between BXA0122 and BXA0124) based on pXO1 from B. anthracis strain A2012, demonstrating transcriptional activity in intergenic regions. Red indicates the transcriptional activity of the parental strain and blue represents strain 34F2ΔluxS.

Discussion

In this study, we were able to complement the luxS/AI-2 deficiency in the 34F2ΔluxS mutant. First, we assessed whether insertion of the luxS ORF plus its putative promoter into the plcR locus, creating 34F2ΔluxS:comp strain, would restore luxS/AI-2 activity. Cell-free medium collected from the 34F2ΔluxS:comp strain was able to fully stimulate luminescence in the V. harveyi reporter strain (Fig. 1), indicating that the B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS:comp strain produces AI-2 or an AI-2-like molecule, likely similar in structure to AI-2 from V. harveyi. Serial dilutions of CFM collected from the 34F2ΔluxS:comp strain were able to stimulate luminescence in the V. harveyi strain to a similar extent as the wild-type 34F2 strain, providing strong evidence that the strain is fully complemented for AI-2 activity. The growth defect observed in the B. anthracis ΔluxS strain suggests that luxS is involved in regulating B. anthracis growth. That the growth of B. anthracis strain ΔluxS:comp was restored to wildtype levels (Fig. 2) provides direct evidence that luxS is in fact involved in regulating B. anthracis growth. Regulation of growth by luxS has been observed in Streptococcus pyogenes.50 In total, these data demonstrate that the altered phenotypes in the ΔluxS strain are due to luxS disruption and not to other undefined coincident mutations.

To better understand the role of luxS/AI-2-mediated QS in regulating B. anthracis gene expression and growth regulation, we utilized microarray analysis. Our use of microarrays permitted us to identify a number of genes potentially regulated by the luxS/AI-2 QS system, but which in total represent <1% of those in the B. anthracis genome. Downregulation in the ΔluxS strain of key virulence genes pagA, pagR, lef and cya, is notable. Inhibition of nitrate metabolism might explain the growth defect present in the 34F2luxS strain. The observed inhibition of the plasmid-encoded toxin gene expression may or may not be direct; AI-2 can modulate the expression of Vibrio cholerae toxins in concert with small RNAs (sRNA).44 Furthermore, recent data has demonstrated that small RNAs play a critical role in regulating virulence and sporulation in V. cholerae and B. subtilis, respectively.51–54 One potential mechanism for luxS/AI-2-mediated quorum-sensing modulation of B. anthracis toxin expression is through the regulation of sRNAs. Detection of AI-2 by bacterial cells could potentially up or downmodulate regulatory small RNAs, leading to differential expression of the B. anthracis toxins.

To further understand the mechanisms by which B. anthracis utilizes the luxS/AI-2-mediated QS system to regulate growth-phase-dependent gene expression, we studied halogenated furanones, known inhibitors of QS.30–36,55 Furanone-1 [(5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone] has been shown to inhibit >70% of the AI-2 regulated genes in E. coli, without affecting bacterial growth rate.31 We recently showed that halogenated furanones inhibit B. anthracis growth in a dose-dependent manner, and can inhibit the expression of lacZ when fused to the promoters of the toxin components.30 The microarray analyses now reveal that treatment of cells with furanone (fur-2) results in inhibition of the transcription of virulence genes lef and cya on pXO1, and respiratory nitrate systems (Open reading frames BA2125-28, BA2133-38 and BA2142-46). Upstream sequence analysis of each potential operon revealed a conserved promoter motif, suggesting coordinate regulation of these operons (Suppl. Table 1). However this motif was not found upstream of atxA or other virulence genes. These data indicate that fur-2 inhibits B. anthracis virulence gene expression and may lead to the development of a novel therapeutic agent against anthrax infections. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, respiratory nitrate regulation has been implicated to be QS-dependent.56

We conclude that B. anthracis utilizes luxS to regulate AI-2-dependent QS and bacterial growth; with specific regulation of expression of the S-layer protein EA1, respiratory nitrate systems and potentially, the lethal and edema toxins. We do recognize the limitation of our study working with an attenuated strain lacking pXO2. The experimentation performed in a pXO2-strain done for reasons concerning biosafety, however it would be fascinating to know what impact the pX02-background might have on the gene expression patterns measure. We further conclude that the study of halogenated furanones may be used to guide development of novel inhibitors of B. anthracis virulence gene expression, as well as novel treatments for anthrax. Finally, identification of small RNAs on pXO1 suggests a novel mechanism for the regulation of virulence gene expression in B. anthracis. Further interrogating these small RNAs may illuminate greater understanding on how the toxins are expressed, since no atxA binding motif has ever been identified.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

B. anthracis strains 34F2 (Colorado Serum Company, Denver, CO), 34F2ΔluxS and 34F2ΔluxS:comp were routinely grown in Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI) or BHI with 0.8% sodium bicarbonate at 37°C. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was routinely grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) at 37°C. Ampicillin (50 µg/ml) was added for cultivation of DH5α strains harboring recombinant plasmids. V. harveyi strain BB170, kindly provided by Bonnie Bassler (Princeton University, Princeton, NJ), was routinely grown in Auto-inducer Bioassay medium (AB) at 30°C.57,58

Generation of cell-free culture medium and V. harveyi bioassays.

B. anthracis strains were grown overnight with aeration at 37°C. Cell-free conditioned culture medium (CFM) was prepared by centrifugation of cultures at 4,000 rpm (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810R) and passing the medium through a 0.2 µm pore-size MILLIPORE syringe filters (Carrigwohill Company, Cork, Ireland). CFM preparations were stored at −20°C until used. CFM from V. harveyi strain BB170 was prepared in the same manner, except that cultures were grown at 30°C. V. harveyi bioluminescence assays were performed essentially as previously described.37 Briefly, V. harveyi strain BB170 was grown at 30°C with aeration for 16 h, cultures were diluted 1:10,000 in fresh AB broth, and then 10% CFM or dilutions thereof from the bacterial cultures to be tested was added. Aliquots of 1.0-ml were taken 5 h after CFM was added, and bioluminescence measured, expressed as relative light units (RLU), using a luminometer.

Construction of a B. anthracis ΔluxS: complement strain.

To complement the luxS deletion in B. anthracis strain 34F2ΔluxS, the plcR operon, which encodes a pleiotropic regulator of hemolysins and phospholipases in Bacillus cereus, was selected as the site for integration of the luxS complementation cassette. In wild-type B. anthracis strains, plcR contains a nonsense mutation making it naturally inactive and thus a neutral spot for an in trans complementation locus.59 The luxS ORF including its putative promoter were cloned into the plcR ORF. PCR was used to amplify a 3 kb fragment from the plcR locus, including 1.05 kb upstream and 1.1 kb downstream of the plcR ORF using primers P1 and P2 (Table 1). The PCR-amplified product was purified using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and subsequently cloned into pGEM-T easy. A plasmid with the correct insert and orientation was designated pMJ601. pMJ601 was modified by inverse PCR to add BamHI sites (primers P3 and P4; Table 1) in the middle of the cloned insert for insertion of the luxS complementation cassette. The luxS complementation cassette was created by using purified chromosomal DNA of B. anthracis strain 34F2. B. anthracis luxS was cloned using primers P9 and P10 to generate a 715-bp fragment including the putative luxS promoter. Downstream of the luxS ORF an erythromycin resistance cassette (ErmR) was inserted into the XbaI/BamHI site by restriction digest to enable selection for plasmid integration. Finally, primers P11 and P12 (Table 1) were used to clone the plcR region containing the luxS/ErmR complementation cassette into B. anthracis shuttle vector pUTE29 that confers TetR. A plasmid with the correct insert was designated pMJ602ET. Purified pMJ602ET from SCS110 was electroporated into B. anthracis strain 34F2:ΔluxS and colonies selected for erythromycin resistance. Transformants were initially picked on medium containing 5 µg/ml of erythromycin, and then subcultured twice daily in the absence of antibiotics at 37° with aeration, for 15 days. Individual colonies were subsequently screened to identify clones that were both ErmR and TetS. This would suggest loss of pMJ602ET and incorporation of the modified plcR allele into the chromosome. For clones with the appropriate antibiotic phenotype, the correct insertion was confirmed by PCR using primers luxSF/P6 and luxSR/P5 (Table 1).

RNA isolation for microarray analysis.

B. anthracis RNA was isolated from bacterial cultures grown to mid-log in BHI media with or without sodium bicarbonate, RNAprotect (Qiagen) was directly added to the growth media at a concentration of 2:1 (volume of RNAprotect to bacterial culture). RNA was isolated from bacterial cultures grown in the presence of or the absence of furanone- 2 (fur-2; 3-butyl-5-(dibromomethylene)-2-(5H)-furanone), as stated above. Cells treated with RNAprotect were pelleted and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction, using the Ambion mir-Vana RNA kit (Austin, TX) in combination with the Barocycler (Pressure BioSciences, South Easton, MA). RNA quantity and quality was assessed by measuring total RNA using a nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and visualizing RNA on an agarose gel. Purified RNA was stored at −80°C.

Generation of probes for microarray experiments.

DNA probes for microarray experiments were generated by adding 2 µg of total RNA in a mixture containing 6 µg of random hexamers (Invitrogen), 0.01 M dithiothreitol, an aminoallyl-deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture containing 25 mM each dATP, dCTP and dGTP, 15 mM dTTP, and 10 mM amino-allyl-dUTP (aa-dUTP) (Sigma), reaction buffer, and 400 units of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) at 42°C overnight. The RNA template then was hydrolyzed by adding NaOH and EDTA to a final concentration of 0.2 and 0.1 M, respectively, and incubating at 65°C for 15 min. Unincorporated aa-dUTP was removed with a Minelute column (Qiagen). The probe was eluted with a phosphate elution buffer (4 mM KPO4, pH 8.5, in ultrapure water), dried and resuspended in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.0). To couple the amino-allyl cDNA with fluorescent labels, normal human serum-Cy3 or normal human serum-Cy5 (Amersham) was added at room temperature for 1 h. Uncoupled label was removed using the Qiagen Minelute column (Valencia, CA) (intranet.jtc.jcvsf.org/sops/M007.pdf).

Microarray hybridization, scanning, image analysis, normalization and analysis.

Aminosilane-coated slides printed with a set of 15,552 B. anthracis open reading frame sequences (www.jcvi.org) were prehybridized in 5x SSC (1x SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) (Invitrogen), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 1% bovine serum albumin at 42°C for 60 min. The slides then were washed at room temperature with distilled water, dipped in isopropanol and allowed to dry. Equal volumes of the appropriate Cy3- and Cy5-labeled probes were combined, dried and then resuspended in a solution of 40% formamide, 5x SSC and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Resuspended probes were heated to 95°C prior to hybridization. The probe mixture then was added to the microarray slide and allowed to hybridize overnight at 42°C. Hybridized slides were washed sequentially in solutions of 1x SSC-0.2% SDS, 0.1x SSC-0.2% SDS and 0.1x SSC at room temperature, then dried in air and scanned with an Axon GenePix 4000 scanner (intranet.jtc.jcvsf.org/sops/M008.pdf). All wash buffers were supplemented with 1-ml of 0.1 M DTT per liter of wash buffer. Individual TIFF images from each channel were analyzed with TIGR Spotfinder (available at (pfgrc.jcvi.org/index.php/bioinformatics.html). Microarray data were normalized by LOWESS normalization and with in-slide replicate analysis using TM4 software MIDAS (available at (pfgrc.jcvi.org/index.php/bioinformatics.html).38,60 We selected genes in which comparison of wild-type cells exposed to diluent alone and cells exposed to 20 µg/ml of fur-2 yielded log2 value |≥1.5| in all samples. We also selected genes that had a log2 value |≥1.5| in all samples, comparing wild-type cells to ΔluxS cells. Genes with a log2 value |≤1.5| but a log2 value |≥1| were selected if the gene appeared in the middle of an operon.

Analysis of upstream promoter motifs.

A selected set of genes that appeared to be co-regulated in the linear expression map were analyzed to discover motifs in upstream areas that may identify common transcription factor binding sites. For motif discovery analysis, 200 base sequences upstream of each gene in the genome were collected. These upstream sequences were truncated when necessary to exclude sequences that crossed a neighboring gene boundary. Upstream sequences less than 30 bases were excluded. If the gene was transcribed on the minus strand, the reverse complement of the upstream region was analyzed. Motif finding was performed using the discriminative motif finding tool, DEME.61 DEME requires two input sequence lists; one input corresponds to upstream areas believed to possibly contain a shared motif and the other set consists of upstream sequences of genes that are thought to not contain the motif within the positive group. The algorithm attempts to find a motif that best separates the positive group of upstream sequences corresponding to the co-regulated gene set from the negative set, representing all other upstream sequences in the genome. A 15 base window was used and the reverse complement of each upstream section also was analyzed. DEME reports a consensus motif and upstream sequence matches for each positive and negative sequence. NCBI refseq was the source for the whole genome sequence file and the coordinate file (ptt file) used to extract upstream sequences.

Analysis of small RNA s in B. anthracis 34F2ΔluxS strain.

Cells were grown to early log phase and pellets collected at 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes. Total RNA was extracted from cell pellets previously treated with RNAprotect (Qiagen), and the extracted RNAs were treated with Turbo DNA-free DNase (Ambion), then converted to cDNA and labeled according to the Affymetrix protocol. Labeled probes were hybridized onto the Affymetrix platform and incubated overnight in an Affymetrix oven. Chips were washed, scanned and .CEL files were imported into genomeMTV (www.genomeMTV.org) for analysis. Data were normalized by the genomeMTV software, based on quantum normalization. Analysis of pXO1 using the sliding window of genomeMTV permitted us to visually scan the virulence plasmid and inspect for intergenic transcriptional activity.

Table 6.

Select B. anthracis genes on pXO1 downregulated by fur-2

| Locusc | Gene nameb | Symbol | 120 mina |

| BXA0124 | S-layer protein | −16.63 | |

| BXA0142 | calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase | cyaA | −1.41 |

| BXA0146 | transcriptional activator AtxA | atxA | −1.34 |

| BXA0164 | protective antigen | pagA | −13.48 |

| BXA0166 | transcriptional repressor PagR | pagR | −5.81 |

| BXA0172 | lethal factor | lef | −2.03 |

Numbers represent fold change;

Functional annotations were obtained from the B. anthracis complete genome sequence (www.jcvi.org);

Locus based on B. anthracis strain A2012.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Garabedian for providing instrumentation. This work was supported in part by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Northeast Biodefense Center NIAID Regional Center for Excellence (U54 AI057 158), RO1 AI 068409 from the National Institutes of Health, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the UNCF/Merck Graduate Dissertation Fellowship, the Pathogen Functional Genomics Resource Center (PFGRC) contract (contract No. N01-AI15447) and funding by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/virulence/article/10752

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Dutz W, Kohout E. Anthrax. Pathol Annu. 1971;6:209–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hambleton P, Carman JA, Melling J. Anthrax: the disease in relation to vaccines. Vaccine. 1984;2:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(84)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turnbull PC. Anthrax vaccines: past, present and future. Vaccine. 1991;9:533–539. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90237-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ullmann A, Mock M. A particular class of virulence factors: calmodulin-activated bacterial adenylate cyclases. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1994;281:284–295. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makino S, Uchida I. The pathogenesis of Bacillus anthracis. Nippon Saikingaku Zasshi. 1996;51:833–840. doi: 10.3412/jsb.51.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna PC, Ireland JA. Understanding Bacillus anthracis pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:180–182. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brossier F, Mock M. Toxins of Bacillus anthracis. Toxicon. 2001;39:1747–1755. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mock M, Fouet A. Anthrax. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:647–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koehler TM. Bacillus anthracis genetics and virulence gene regulation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;271:143–164. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-05767-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mock M, Mignot T. Anthrax toxins and the host: a story of intimacy. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:15–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahuja N, Kumar P, Bhatnagar R. The adenylate cyclase toxins. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2004;30:187–196. doi: 10.1080/10408410490468795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moayeri M, Leppla SH. The roles of anthrax toxin in pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mock M, Ullmann A. Calmodulin-activated bacterial adenylate cyclases as virulence factors. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90089-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brossier F, Guidi-Rontani C, Mock M. Anthrax toxins. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1998;192:437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanna P. Anthrax pathogenesis and host response. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;225:13–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80451-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little SF, Ivins BE. Molecular pathogenesis of Bacillus anthracis infection. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu S, Schubert RL, Bugge TH, Leppla SH. Anthrax toxin: structures, functions and tumour targeting. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3:843–853. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrami L, Reig N, van der Goot FG. Anthrax toxin: the long and winding road that leads to the kill. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sirard JC, Mock M, Fouet A. The three Bacillus anthracis toxin genes are coordinately regulated by bicarbonate and temperature. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5188–5192. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.5188-5192.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray KM. Intercellular communication and group behavior in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:184–188. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison DA. Streptococcal competence for genetic transformation: regulation by peptide pheromones. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:27–37. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardman AM, Stewart GS, Williams P. Quorum sensing and the cell-cell communication dependent regulation of gene expression in pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1998;74:199–210. doi: 10.1023/a:1001178702503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassler BL. How bacteria talk to each other: regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:582–587. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bassler BL. Small talk. Cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Cell. 2002;109:421–424. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manefield M, Welch M, Givskov M, Salmond GP, Kjelleberg S. Halogenated furanones from the red alga, Delisea pulchra, inhibit carbapenem antibiotic synthesis and exoenzyme virulence factor production in the phytopathogen Erwinia carotovora. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;205:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hentzer M, Givskov M. Pharmacological inhibition of quorum sensing for the treatment of chronic bacterial infections. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1300–1307. doi: 10.1172/JCI20074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hentzer M, Wu H, Andersen JB, Riedel K, Rasmussen TB, Bagge N, et al. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 2003;22:3803–3815. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith KM, Bu Y, Suga H. Induction and inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing by synthetic autoinducer analogs. Chem Biol. 2003;10:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones MB, Jani R, Ren D, Wood TK, Blaser MJ. Inhibition of Bacillus anthracis Growth and Virulence-Gene Expression by Inhibitors of Quorum-Sensing. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1881–1888. doi: 10.1086/429696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren D, Bedzyk LA, Ye RW, Thomas SM, Wood TK. Differential gene expression shows natural brominated furanones interfere with the autoinducer-2 bacterial signaling system of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88:630–642. doi: 10.1002/bit.20259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren D, Bedzyk LA, Setlow P, England DF, Kjelleberg S, Thomas SM, et al. Differential gene expression to investigate the effect of (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone on Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4941–4949. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4941-4949.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren D, Zuo R, Wood TK. Quorum-sensing antagonist (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone influences siderophore biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;66:689–695. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren D, Wood TK. (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone reduces corrosion from Desulfotomaculum orientis. Environ Microbiol. 2004;6:535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren D, Sims JJ, Wood TK. Inhibition of biofilm formation and swarming of Bacillus subtilis by (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2002;34:293–299. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2002.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren D, Sims JJ, Wood TK. Inhibition of biofilm formation and swarming of Escherichia coli by (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone. Environ Microbiol. 2001;3:731–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones MB, Blaser MJ. Detection of a luxS-signaling molecule in Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3914–3919. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3914-3919.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morozkina EV, Zvyagilskaya RA. Nitrate reductases: structure, functions and effect of stress factors. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2007;72:1151–1160. doi: 10.1134/s0006297907100124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakano MM, Yang F, Hardin P, Zuber P. Nitrogen regulation of nasA and the nasB operon, which encode genes required for nitrate assimilation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:573–579. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.573-579.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmer BM, van Reeuwijk J, Timmers CD, Valentine PJ, Heffron F. Salmonella typhimurium encodes an SdiA homolog, a putative quorum sensor of the LuxR family, that regulates genes on the virulence plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1185–1193. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1185-1193.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manefield M, Harris L, Rice SA, de Nys R, Kjelleberg S. Inhibition of luminescence and virulence in the black tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon) pathogen Vibrio harveyi by intercellular signal antagonists. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2079–2084. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.5.2079-2084.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hentzer M, Riedel K, Rasmussen TB, Heydorn A, Andersen JB, Parsek MR, et al. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria by a halogenated furanone compound. Microbiology. 2002;148:87–102. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller MB, Skorupski K, Lenz DH, Taylor RK, Bassler BL. Parallel quorum sensing systems converge to regulate virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Cell. 2002;110:303–314. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00829-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitehead NA, Byers JT, Commander P, Corbett MJ, Coulthurst SJ, Everson L, et al. The regulation of virulence in phytopathogenic Erwinia species: quorum sensing, antibiotics and ecological considerations. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002;81:223–231. doi: 10.1023/a:1020570802717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haralalka S, Nandi S, Bhadra RK. Mutation in the relA gene of Vibrio cholerae affects in vitro and in vivo expression of virulence factors. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4672–4682. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4672-4682.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manna AC, Cheung AL. sarU, a sarA homolog, is repressed by SarT and regulates virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2003;71:343–353. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.343-353.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novick RP, Jiang D. The staphylococcal saeRS system coordinates environmental signals with agr quorum sensing. Microbiology. 2003;149:2709–2717. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hammer BK, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:101–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lyon WR, Madden JC, Levin JC, Stein JL, Caparon MG. Mutation of luxS affects growth and virulence factor expression in Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:145–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lenz DH, Bassler BL. The small nucleoid protein Fis is involved in Vibrio cholerae quorum sensing. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:859–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lenz DH, Miller MB, Zhu J, Kulkarni RV, Bassler BL. CsrA and three redundant small RNAs regulate quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:1186–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lenz DH, Mok KC, Lilley BN, Kulkarni RV, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell. 2004;118:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding Y, Davis BM, Waldor MK. Hfq is essential for Vibrio cholerae virulence and downregulates sigma expression. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ren D, Zuo R, Wood TK. Quorum-sensing antagonist (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone influences siderophore biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004 doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toyofuku M, Nomura N, Kuno E, Tashiro Y, Nakajima T, Uchiyama H. Influence of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal on denitrification in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7947–7956. doi: 10.1128/JB.00968-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bassler BL, Greenberg EP, Stevens AM. Cross-species induction of luminescence in the quorum-sensing bacterium Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4043–4045. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4043-4045.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bassler BL, Wright M, Silverman MR. Multiple signalling systems controlling expression of luminescence in Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes encoding a second sensory pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:273–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agaisse H, Gominet M, Okstad OA, Kolsto AB, Lereclus D. PlcR is a pleiotropic regulator of extracellular virulence factor gene expression in Bacillus thuringiensis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1043–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saeed AI, Bhagabati NK, Braisted JC, Liang W, Sharov V, Howe EA, et al. TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:134–193. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Redhead E, Bailey TL. Discriminative motif discovery in DNA and protein sequences using the DEME algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:385. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.