Abstract

Muscles expend energy to perform active work during locomotion, but they may also expend significant energy to produce force, for example when tendons perform much of the work passively. The relative contributions of work and force to overall energy expenditure are unknown. We therefore measured the mechanics and energetics of a cyclical bouncing task, designed to control for work and force. We hypothesized that near bouncing resonance, little work would be performed actively by muscle, but the cyclical production of force would cost substantial metabolic energy. Human subjects (n = 9) bounced vertically about the ankles at inversely proportional frequencies (1–4 Hz) and amplitudes (15–4 mm), such that the overall rate of work performed on the body remained approximately constant (0.30 ± 0.06 W/kg), but the forces varied considerably. We used parameter identification to estimate series elasticity of the triceps surae tendon, as well as the work performed actively by muscle and passively by tendon. Net metabolic energy expenditure for bouncing at 1 Hz was 1.15 ± 0.31 W/kg, attributable mainly to active muscle work with an efficiency of 24 ± 3%. But at 3 Hz (near resonance), most of the work was performed passively, so that active muscle work could account for only 40% of the net metabolic rate of 0.76 ± 0.28 W/kg. Near resonance, a cost for cyclical force that increased with both amplitude and frequency of force accounted for at least as much of the total energy expenditure as a cost for work. Series elasticity reduces the need for active work, but energy must still be expended for force production.

Keywords: elastic energy, movement efficiency, resonant frequency

walking and running require metabolic energy expenditure for active contraction of muscle, largely associated with the production of work as muscle fibers actively change length. During these cyclical movements, the limbs often perform negative and positive work in succession, allowing elastic tendons to store and return energy. This reduces the need for active work but not for active muscle force, which may also come at substantial metabolic cost. In many tasks, both muscle work and force might thus contribute simultaneously to overall energy expenditure, in proportions largely unknown. Quantification of the active and elastic work contributions could reveal the energetic cost of producing active muscle force, and the energetic savings gained through series elasticity of tendon. Here we estimate these relative contributions in vivo, from a cyclical bouncing task that shares some features with human locomotion.

Elastic energy storage can improve the apparent efficiency of locomotion. Muscles normally perform positive work with a peak efficiency of ∼25% for converting metabolic energy to mechanical energy (21, 22). But in cyclical tasks such as hopping and running, the apparent efficiency—defined as the rate of positive musculotendon work divided by the net metabolic rate—has been observed near 40% (5, 27) as series elasticity, mainly from tendon, contributes substantial work through passive stretching and shortening. This action allows muscle fibers to displace by a smaller amount and perform less work than the muscle and tendon together (24).

Even if elastic tendon were to perform all the work, force from active muscle fibers would still be required to support body weight and load the tendon. The energetic cost of running appears to include a large contribution from the production of force (23), in addition to the expected cost of active muscle fibers performing work (24). Under controlled isometric conditions, the cost of producing force can be quite high even when no active work is performed, and this cost increases with shorter durations of force (6). We refer to this phenomenon as a cost of producing force cyclically (8, 9). A crude model of the cost per contraction increases in proportion to muscle force, and inversely to contraction duration (8). The mechanism for such a cost may be associated with sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase activity (i.e., calcium transport), as opposed to the actomyosin interactions that produce work (15), because the former may become a limiting factor in the production of cyclical force at high frequencies (6). Here we are concerned not with the mechanism, but the degree to which force cycling contributes to the cost of locomotion. That contribution is difficult to quantify during tasks such as running because both work and force usually occur in combination, obscuring the individual costs.

One means of distinguishing between costs is to study simple movements where contraction conditions may be quantified in vivo. Simple models of contractile and elastic components have been particularly effective in identifying the relative displacements of the triceps surae muscles and their shared tendon that acts across the ankle joint, using only noninvasive measurements such as kinematics and ground reaction forces (14), in addition to electromyograms (2). Such identification methods have shown how series elasticity reduces the work needed from active muscle fibers, an observation separately verified through imaging measurements of muscle fascicle length (26). We propose to apply such parameter identification to test the hypothesis that the overall metabolic cost of a hopping-like task includes a cost for producing force cyclically, in addition to the cost for performing work.

The purpose of this study was to estimate the costs of work and cyclic force in human ankle bouncing. This is a simplified form of bipedal hopping without an aerial phase, and with the ankles isolated so that other joints perform little work. We designed the experiment to control for the amount of work performed on the body as a function of bouncing frequency, while varying the amount of force. This was intended to facilitate parameter identification of series elasticity and to separate the two proposed costs. We estimated work due to active muscle and its expected proportion of metabolic cost, and used this as an indicator of the hypothesized cost of producing cyclic force.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We measured the mechanics and energetics of cyclical ankle bouncing performed by human participants. We controlled the overall rate of work performed on the body by varying the frequency of bouncing and prescribing the amplitude of bouncing at each frequency. We also measured the rate of metabolic energy expenditure and tested whether the apparent efficiency of work performed on the body exceeded that expected for active muscle work alone. Using parameter identification of a fixed tendon stiffness across bouncing frequencies, we estimated the relative proportions of displacement and work due to muscle fibers and to tendon. We then estimated the metabolic cost for producing active force by comparing the overall metabolic cost with that expected due to active muscle work alone, based on an assumption of fixed efficiency for active work. Below we describe the experimental procedures as well as the parameter estimation method for identifying tendon stiffness.

Experiment.

Human subjects were asked to perform a bilateral bouncing task, oscillating vertically about the ankles at seven prescribed frequencies ranging from 1 to 4 Hz. As detailed below, the amplitudes decreased with frequency to keep the rate of work performed on the body relatively fixed. Nine healthy adult subjects participated in this study (age 26.9 ± 2.8 yr, body mass 64.9 ± 15.9 kg, leg length 0.93 ± 0.02 m, mean ± SD). Informed consent was obtained and the protocol was reviewed and approved in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan Medical School.

The bouncing task was designed to produce substantial work and force, while maintaining aerobic conditions. Hopping tasks can be too taxing to maintain for durations long enough to collect steady-state respirometry data and often require anaerobic effort (10). To reduce the task demands, subjects bounced not on the balls of the feet but about a fulcrum that provided a reduced moment arm for body weight (Fig. 1A). Subjects stood on a frame with an adjustable rotational axis that served as the fulcrum. Fore/aft fulcrum position was adjusted to reduce the anatomical moment arm rA (estimated as 0.14 ± 0.02 m) that the ankle muscles normally encounter, the distance from directly under the lateral malleolus to the fifth metatarsal (approximately the ground contact point for the balls of the feet), parallel to the foot platform. The task moment arm rF, defined as the distance from the lateral malleolus to the fulcrum, again along the foot platform, was set to 80% of rA (Fig. 1B). The metal support frame introduced nonnegligible compliance to the system, sufficient to introduce possible errors in the measured bounce amplitude. We determined the frame's linear stiffness, 213 kN/m, and used it to correct for compliance by subtracting the frame's deformation from the total observed displacement of the body.

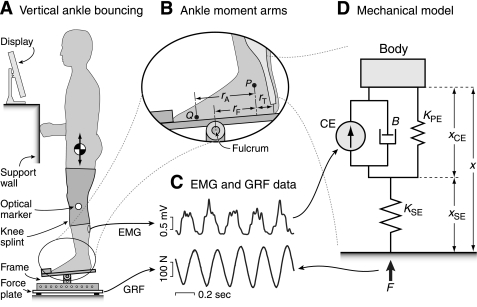

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup for vertical ankle bouncing, with electromyographic (EMG) and ground reaction force (GRF) data used to identify a simple mechanical model of relative muscle and tendon displacements and work. A: subjects performed the bouncing task while standing on a metal frame with an adjustable fulcrum and maintaining balance against a support wall. EMGs were collected from the left plantarflexors, and GRFs were collected by a force plate under the frame. A computer display provided visual feedback of the target bouncing amplitude. B: the adjustable fulcrum was used to reduce the moment arm of bouncing (rF) by ∼20%, to make the task easier for subjects to sustain. The anatomical moment arm rA was defined as the distance between the lateral malleolus (P) and the fifth metatarsal (Q), parallel to the foot platform. Muscle-tendon force is related to GRF by the ratio of rT to rF, where rT is the moment arm of the triceps surae tendon about the ankle joint. C: EMG and GRF data were collected and used as input and output data for a mechanical model (D) of the plantarflexors. The muscles and tendon were represented by a contractile element CE, damper B, and parallel elasticity KPE, in series with series elasticity KSE, acting against the mass M of the body. Model parameter values were fitted to best match the gain and phase relationships between the EMG and GRF data at each frequency. These values were used to estimate the contributions of muscle and tendon (xCE and xSE, respectively) to body displacement; for simplicity, these are expressed in the scale of body displacements rather than actual muscle lengths. F, force.

To enforce ankle bouncing, subjects wore splints to keep the knees extended. To maintain balance, they were allowed to lightly place one hand against a wall for support, so that minimal vertical forces were applied to the wall. Subjects reported no difficulties sustaining this task.

Several mechanical recordings were taken during each trial. A single motion analysis marker (Optotrak, Northern Digital, Waterloo, Canada) on the lower leg measured vertical position at a sampling rate of 100 Hz. Vertical ground reaction force (GRF) was sampled at 100 Hz by a force platform embedded in the floor (AMTI Biomechanics Platform Model OR6-5, Watertown, MA). We also collected electroymyographic (EMG) data at 2,000 Hz from the left lateral gastrocnemius, medial gastrocnemius, and soleus. EMG data were amplified with a custom-built amplifier, band-pass filtered at 20–1,000 Hz, then rectified, summed, and finally smoothed with a low-pass filter at 25 Hz, similar to the procedure of Hof et al. (13). At each bounce frequency, the processed EMG signal and GRF were fit with sinusoids, each with amplitude, phase, and amplitude offset as parameters (Fig. 1C). We calculated a force-EMG gain and phase relationship at each frequency from the amplitudes and phases, respectively, of the GRF and EMG sinusoids.

We measured metabolic rate using an open-circuit respirometry system (VMax29, SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA). To reach an energetic steady state, subjects were asked to bounce at each frequency for at least 6 min, of which only the final 3 min was averaged to estimate energetic demand. Oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production were converted to rate of metabolic energy expenditure Ėmet using standard formulas (3). A baseline trial was performed with subjects standing quietly at rest, and this rate (1.38 ± 0.19 W/kg, mean ± SD) was subtracted from the gross to yield a net metabolic rate for bouncing. During all trials, the respiratory quotient was monitored and found to be below 0.90, indicating that subjects were not exercising anaerobically.

Design of amplitude and frequency conditions.

The amplitude and frequency of the bouncing task were controlled experimentally. Subjects were asked to bounce to the beat of a metronome, at seven frequencies ranging from 1 to 4 Hz. They were also asked to adjust the bounce amplitude using visual feedback displayed on a computer monitor along with the target amplitude. The bounce amplitude was varied depending on the movement frequency to keep the positive mechanical work rate approximately constant across trials, as follows. The vertical displacement is approximated by a sinusoid with frequency ω and amplitude A(ω),

| (1) |

Ground reaction force associated with this movement is equal to

| (2) |

where M denotes the mass of the subject, and g the gravitational acceleration. The rate of mechanical work is the product of force F(t) with vertical velocity ẋ(t). To keep the average rate of positive work relatively fixed for all trials, the bounce amplitude must change in inverse proportion to frequency,

| (3) |

where A0 is a nominal bounce amplitude for the lowest frequency of 1 Hz. This was set to ∼2 cm less than each subject's total possible range of motion.

We estimated force and work performed on the body by the musculotendon complex from the ground reaction force and vertical displacement of the body. Combining the equations above, the amplitude of force fluctuations F(ω) about body weight increases linearly with frequency,

| (4) |

The actual force produced by the musculotendon complex depends on the ratio between rF and the plantarflexor moment arm rT about the ankle joint (see Fig. 1B). Rather than determine the latter, we treated ground reaction force F(t) as a proportional indicator of musculotendon force and computed the rate of work performed on the body center of mass (COM) from its product with velocity (4). The work performed on the body was treated as equivalent to the overall musculotendon work. The rate of positive musculotendon work ẆMT+ was defined as the positive work on the body per cycle, divided by the cycle period.

Subject-specific parameter identification.

To estimate series elasticity and tendon work in individual subjects, we used a simple mechanical model of the musculotendon system powering rhythmic plantarflexion, similar to that reported by Bach et al. (2). The model includes a muscle with a contractile component, damper with coefficient B, and parallel elasticity KPE, along with tendon with series elasticity KSE, all expressed in the scale of effective forces and displacements of the body, so that they act directly against the mass M of the body (Fig. 1D). To convert these parameters to actual muscle stiffness and damping, they must be multiplied by (rT/rF)2. The muscle lumps together the actions of the triceps surae with a transfer function, in the Laplace domain, from EMG signal E(s) to ground reaction force F(s):

| (5) |

where G is the gain between EMG and force, and τd a time delay for force production, approximated by a first-order linear filter. This constitutes the model with fewest parameters to be identified that provides a good match to experimental data (see Supplementary Material, available with the online version of this article, for comparisons with other models). We used the EMG signal to estimate the force produced by the contractile component of the muscle. The calculated gain and phase shift values between the EMG and GRF data were used to determine the subject-specific parameters that gave the best match to the experimental data. To determine the least-squares fit, we calculated R2 values between the experimental data and the model predictions for gain and phase shift.

We tested the correction for compliance of the support frame under the subject's feet. This was conducted by first identifying model parameters for a subject performing the normal bouncing trials including the frame. The model was then adjusted to remove the frame, thereby forming a prediction for bouncing on rigid force plates. This was compared with a separate set of trials of the same subject performing the same tasks but without the frame. A comparison of the model's predictions with the experimental transfer function yielded reasonable agreement (R2 = 0.86 for gain prediction, R2 = 0.99 for phase prediction). In other words, data from one set of conditions were able to predict another set of data for an independent set of conditions, indicating that the model was reasonably accurate.

The parameter values calculated from the model were used to estimate the rates of positive work by muscle fibers and by tendon (ẆM+ and ẆT+, respectively) at each frequency. These two sum to yield the rate of positive musculotendon work ẆMT+ performed on the body. We also estimated the peak forces, and body displacements xCE and xSE due to muscle and tendon, respectively (see Fig. 1). Both xCE and xSE refer to contributions to body displacements and may be converted to the actual musculotendon displacements by multiplying by the ratio of moment arms rT/rF.

The work and metabolic rates were used to estimate the costs of producing work and force. We tested for two competing contributions to overall metabolic cost. The first was a hypothesized energy expenditure rate ĖW proportional to work rate:

| (6) |

where we assumed a work efficiency of 25% as a maximum constant of proportionality. The other was a cost for force cycling, hypothesized to be a cost per contraction increasing with force F (body weight plus an inertial term; Eq. 2) and bounce frequency ω (8, 9), where ω is assumed to be inversely proportional to contraction duration. This is intended to crudely model the limiting effects of muscle activation and deactivation time constants, whereby a short burst of muscle force requires relatively more calcium to be released (and pumped) than a longer burst of the same force. To produce a predicted rate of energy expenditure ĖF, the cost per contraction is multiplied by bounce rate ω to yield

| (7) |

Dimensionless variables.

To account for anthropometric differences between subjects, we converted our results to dimensionless variables, normalizing force by body weight Mg, bounce amplitude by the nominal amplitude A0, and mechanical and metabolic rates of work by , where M is mass, g is gravity, and L is leg length. We also corrected for differences in the amplitude of the task between subjects by normalizing the dimensionless rate of work values by the ratio of each individual's nominal amplitude to the average across subjects. The calculated force cycling rate values were converted to dimensionless values by dividing by Mg2/L. To facilitate convenient interpretation, we report results in more familiar dimensional form, multiplying the nondimensional values by the average normalization factors. Apparent efficiency was defined as the rate of positive musculotendon work performed on the body divided by the net metabolic rate. Active work efficiency was defined as the rate of positive muscle work, as estimated by the model, divided by the net metabolic rate.

Statistics.

We performed one-way repeated-measures ANOVA to test for frequency-dependent differences in the calculated dimensionless measures of bounce amplitude, peak force, positive musculotendon work rate, metabolic work rate, rate of force/time, and efficiency. Additional one-way repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed to test for differences in the simulated values for muscle rate of work, tendon rate of work, and change in muscle length, with frequency as the independent variable. We also compared the experimentally measured metabolic cost to that predicted using only positive muscular rate of work (Eq. 6) with an assumed efficiency of 25%. Where appropriate, post hoc t-tests were performed to determine the frequencies at which significant differences occurred. For all tests, we treated P < 0.05 as statistically significant.

RESULTS

We found the bouncing task to require work on the body to be performed at a constant rate across bounce frequencies, and yet to require greater metabolic energy expenditure at both the lowest and highest bouncing frequencies. Energy expenditure was therefore not explained solely by work performed on the body at constant efficiency. The apparent work efficiency far exceeded 25% at intermediate frequencies, consistent with bouncing at resonance where little active work is required and the elastic tendon can account for much of the overall displacement. Using the identified, subject-specific series elasticity, we formed estimates of the relative displacements due to muscle and tendon and found these to agree well with the expectation that tendon would perform an increasing proportion of work at higher frequencies. But using the resulting estimate of active work by muscle fibers was still insufficient to explain the overall metabolic cost of bouncing. We found that an additional cost, not proportional to work, was necessary. The hypothesized cost of force cycling was found to agree well with this additional cost. We next consider details of these findings, beginning with basic measurements of the task itself.

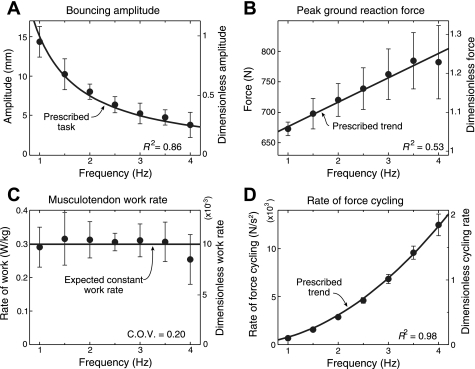

Subjects roughly followed the prescribed bouncing behavior and thus kept the rate of musculotendon work nearly constant across frequency. As prescribed, the bounce amplitude varied in inverse proportion to bounce frequency (Fig. 2A), while the peak force increased approximately linearly with frequency (Fig. 2B). The rate of musculotendon work performed on the body remained relatively constant (0.30 ± 0.06 W/kg), with no significant difference across frequencies (Fig. 2C, P = 0.266). However, the rate of force cycling increased approximately with frequency squared (Fig. 2D), therefore predicting an increasing metabolic rate at high frequencies.

Fig. 2.

Mechanical measurements of vertical ankle bouncing at prescribed frequencies and amplitudes, averaged across subjects (n = 9). A: actual bounce amplitude was inversely proportional to bounce frequency, as prescribed by Eq. 3. B: peak ground reaction force increased approximately linearly with bounce frequency (Eq. 4). C: the average rate of positive work performed on the body remained approximately constant across frequencies (ANOVA, P = 0.266), as was intended by the choice of amplitude. The ratio of the SD and the mean, or coefficient of variation (COV), was 0.20. D: a rate of force cycling, hypothesized to also contribute to metabolic cost, increased approximately with the square of frequency. The curves of C and D represent the prescribed trends expected from the task conditions and are both hypothesized to contribute to overall metabolic cost, to be tested by the experiment. Data points shown are means across subjects, with error bars representing SD. Left-hand vertical axes show scale in absolute units, and right-hand axes show scale in dimensionless form, using body mass, gravitational acceleration, and leg length as base units to account for anthropometric differences between subjects.

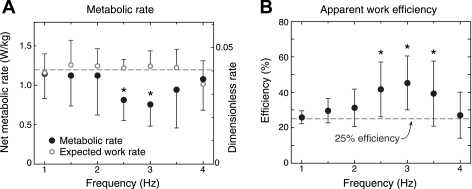

Despite a relatively constant musculotendon work rate, the metabolic rate varied across frequencies, with a minimum value near 3 Hz (Fig. 3A). Each of the nine subjects had a minimum metabolic cost either in the 3-Hz condition or one of the neighboring frequencies. An assumed constant work efficiency of 25%—the metabolic rate expected from active muscle work alone—greatly overestimated the actual cost at the intermediate frequencies. The apparent efficiencies, found by dividing the rate of positive work performed on the body by actual metabolic rate, varied significantly (P < 0.05) with frequency (Fig. 3B). The apparent efficiency was 26 ± 4% (mean ± SD) at 1 Hz, and peaked at 45 ± 15% at 3 Hz. Each subject had a peak apparent efficiency that exceeded 25%, suggesting work performed by elastic tendon (27).

Fig. 3.

Metabolic rate and apparent efficiency of work during ankle bouncing. A: rate of metabolic energy expenditure was not constant, and differed significantly from that predicted by the rate of musculotendon work on the body (ANOVA, P < 0.0001), assuming constant 25% work efficiency. Significant differences were observed at the intermediate frequencies of 2.5 Hz (P = 0.0024) and 3 Hz (P = 0.0007). B: apparent efficiency, defined as rate of positive mechanical work performed on the body divided by metabolic rate, changed significantly across frequency (ANOVA, P < 0.0001). Efficiencies were significantly higher than 25% at 2.5 Hz (P = 0.012), 3 Hz (P = 0.004), and 3.5 Hz (P =0.049). Data points shown are means ± SD of the group data.

We found the parameter identification model to fit well with each subject's data. The gain and phase relationships produced by the transfer function between the EMG and GRF displayed frequency-dependent trends that agreed well with experimental data (see Supplementary Material, available with the online version of this article, for sample plots). The gain exhibited a peak at an intermediate frequency, while the phase shift decreased with increasing bounce frequencies. The model's peak gain occurred at the mechanical resonant frequency, which averaged 3.07 ± 0.43 Hz (mean ± SD). The average parameter values are given in Table 1, in both dimensional and dimensionless form. Across subjects, the calculated R2 values between experimental data and the identified model ranged from 0.86 to 0.96 for the gains, and from 0.97 to 0.99 for the phase shifts.

Table 1.

Model parameter values, both dimensional and dimensionless

| Parameter | Dimensional Value | Dimensionless Value |

|---|---|---|

| M | 64.9 ± 15.9 kg | 1 |

| B | 2,620 ± 940 N/ms−1 | 12.5 ± 3.6 |

| KPE | 10,000 ± 3570 N/m | 14.6 ± 4.4 |

| KSE | 30,200 ± 7,800 N/m | 44.7 ± 9.6 |

| G | 2,410 ± 1,150 | Not applicable |

| τd | 129 ± 66 ms | 0.424 ± 0.228 |

Values are means ± SD. To calculate the dimensionless parameters, mass was normalized by M, damping by M, stiffness by Mg/L, and time delay by , where M is subject mass, g is the acceleration of gravity, and L is the subject leg length (defined as greater trochanter height). B, damper coefficient; KPE and KSE, parallel elasticity and series elasticity parameters, respectively; G, gain between EMG and force; τd, time delay for force production.

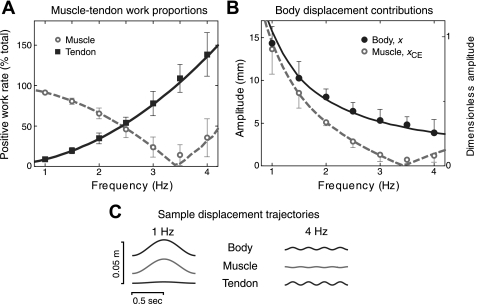

The identified subject-specific mechanical parameters were used to estimate the relative contributions of the muscle and tendon to the total positive musculotendon work performed on the body. The tendon work rate increased with bounce frequency, whereas the muscle work rate decreased up to about resonant frequency (Fig. 4A). As prescribed, the amplitude of the body's displacement decreased with frequency, but the displacement due to changes in muscle length decreased to a greater extent (Fig. 4, B and C), with tendon responsible for increasing amounts of displacement. Above resonant frequency, the muscle work rate increased as the muscle and tendon acted increasingly in opposite phase (i.e., the muscle lengthened as the tendon shortened, and vice versa). This caused the displacement due to tendon to exceed the overall displacement of the body, reflected by tendon work contributions greater than 100% (Fig. 4A). Even though the rate of work performed on the body was nearly constant, the proportion performed by tendon increased sharply with bounce frequency.

Fig. 4.

Estimates of work proportions and body displacement contributions due to muscle and tendon, as computed from the mechanical model. A: proportion of the positive work rate due to muscle changed significantly across frequency (ANOVA, P < 0.0001); work rate at frequencies below 2.5 Hz was significantly larger than at higher frequencies (P < 0.018). Tendon work rate was not constant (ANOVA, P < 0.0001) and increased with frequency. B: the bounce amplitude and displacement due to muscle each changed significantly with frequency (ANOVA, P < 0.0001). The displacement due to muscle decreased significantly with higher frequencies (P < 0.01), with tendon length changes accounting for the difference with body displacement. Subject-specific model estimates (data points) shown are means ± SD across subjects. Analytical predictions (continuous lines) are based on average parameter values. C: sample simulation trajectories show how body, muscle, and tendon displacement differ at 1 Hz vs. 4 Hz bouncing. At higher frequencies, the greater ground reaction forces resulted in greater displacement due to tendon, as both body displacement and displacement due to muscle decreased.

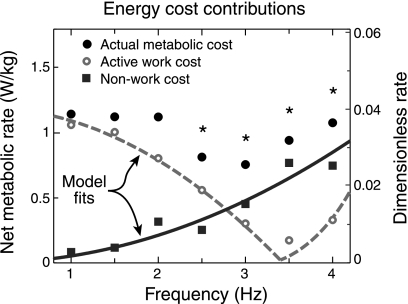

The estimate of active muscle work was then used to predict the metabolic cost of performing this work (Fig. 5), and subsequently a residual cost not explained by work. At low frequencies (≤2 Hz), positive muscular work (from Fig. 4) at 25% efficiency was a reasonable predictor of metabolic cost. For example, at 1 Hz, the active work efficiency (active work rate divided by metabolic rate) was 24 ± 3%, agreeing well with the apparent efficiency (total work rate divided by metabolic rate). This is consistent with the expectation that slow movements cause little dynamic loading of tendon, with the tendon loaded nearly statically by body weight and thus performing little work at 1 Hz. But the agreement was much poorer at higher frequencies, most notably near resonance, where there was a substantial metabolic cost despite very little work by muscle. At 3 Hz, an assumed 25% efficiency for active work could only account for ∼40% of the actual metabolic cost. The difference between actual metabolic cost and that predicted by muscle work, referred to as a “nonwork cost,” increased with bounce frequency. This nonwork cost was consistent with the hypothesized cost of force cycling, which was predicted to increase with frequency squared (Eq. 7; R2 = 0.34).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of actual metabolic rate with predicted work cost (Eq. 6), based on muscle work alone. Assuming constant work efficiency, the work cost due to active muscle (dashed line) was significantly different from the actual metabolic cost as a function of frequency (ANOVA, P < 0.0001), particularly at 2.5–4 Hz (P < 0.05). The difference, or the “nonwork cost,” was fit by a factor proportional to frequency squared (R2 = 0.34), as predicted by the hypothesized cost of force cycling (Eq. 7). Actual metabolic cost data are from Fig. 3, and predicted work cost data are from Fig. 4.

DISCUSSION

This experiment was designed to examine the energetic cost of bouncing at different frequencies while keeping the rate of positive musculotendon work constant. Energetic cost was minimized at a bouncing frequency near 3 Hz, very similar to the average resonant frequency of 3.07 Hz calculated independently from the parameter identification model. We found evidence for two frequency-dependent contributions to energy expenditure: a cost of using muscles to perform positive work, and a cost of producing force cyclically even when elastic tendon performs much of the work passively. As expected, a cost of performing active muscle work was able to explain the overall metabolic cost of bouncing at low frequencies. But at higher frequencies, there was a portion of overall cost not explained by muscle work, especially at resonance, when little active work was needed and its associated cost approached a minimum. This residual was found to agree well with the hypothesized force cycling cost. We next consider the evidence for work- and force-related costs, as well as the assumptions and limitations in interpreting that evidence.

Although we used parameter identification to estimate muscle work, many of the overall conclusions can be explained on a qualitative basis. For example, the indication of tendon work may be examined solely from the apparent efficiency of work performed on the body. This efficiency was close to 25% for low frequencies at which little elastic energy storage and return are expected, consistent with active muscle work. But as the loading increased at higher frequencies the efficiency increased, indicating less work performed actively by muscle, as has previously been observed in both hopping (26) and running (5). The peak efficiency of ∼45% occurred near the identified resonant frequency, where no muscle work is required except to overcome dissipative losses. In our calculations, we neglected negative work with typical efficiency of about −120% (e.g., 22), but its inclusion would only lower the expected efficiency, and thus reinforce the indication of work performed passively by tendon.

Another immediate observation is that the proportion of tendon work increased steadily with frequency. The increasing ground reaction force with bounce frequency (Fig. 2B) suggests roughly proportional increases in tendon displacement. Coupled with decreasing body displacement, this implies a relatively greater proportion of passive work by tendon, nearly 100% at resonance. These estimates of mechanical behavior, as well as our more detailed model predictions, are consistent with the experimental measurements of Takeshita et al. (26), who measured the amplitudes of musculotendon length and muscle fascicle length during a bouncing task. At low frequencies, nearly all of the length change was due to muscle shortening. As frequency increased (up to ∼3 Hz), an increasing proportion of the length change occurred in the tendon. At frequencies above 3 Hz, the length changes occurred out of phase, as work performed by one element was taken up by the other. Even though muscles would be expected to perform little active work at intermediate frequencies, we found that the overall energetic cost of bouncing never approached zero. This nonzero cost may be due to the cost of producing force cyclically and may explain the substantial cost of producing force under isometric conditions (25).

The proportion of the total metabolic rate not explained by muscular work was considerable, ∼60% when bouncing near resonance. The nonwork cost per time increased approximately with frequency squared (Fig. 5) under the frequency conditions prescribed here. This increase was consistent with our hypothesized energetic cost to produce force cyclically (8), which was also predicted to increase quadratically with bounce frequency. Although we have speculated that the cost is associated with force cycling, perhaps due to the pumping of calcium (8), further conclusions cannot be drawn without more direct physiological measurements from muscle (e.g., 15, 16, 26). Future experiments could further test the contribution of a nonwork cost for other tasks, and under more combinations of work and force as has been performed for a leg swinging task (8, 9).

Our estimates of work proportion are subject to a number of limitations. We used a simple linearized model of muscle and tendon with parallel and series elasticity, which assumes constant stiffness. Other studies of triceps surae indicate that stiffness is fairly constant at the loads of ∼70 N·m applied here (12), and have found linear systems models to fit reasonably well with similar data (e.g., 2, 26). We identified a series elasticity equivalent to ∼30 kN/m and thus a resonant frequency of 3.1 Hz, which agreed well with the observed minimum for metabolic rate. The elasticity is also comparable to the 32 kN/m reported by Bach et al. (2) for a jump landing. The linearized model also predicted the gain and phase relationships reasonably well, indicating adequate accuracy for the estimates performed here. (An additional analysis of model complexity and effect of nonlinearities is included in the Supplementary Material, available with the online version of this article.)

For our simple bouncing task, the cost of cyclically producing muscle force was a major contributor to metabolic cost when the muscle was producing small amounts of work and the tendon was storing and returning energy. A similar cost of producing muscle force exists during isolated leg swing (8, 9), at amplitudes and frequencies comparable to the back-and-forth motion of the legs during human walking and running. We would expect the cost of producing force to be relevant not only to leg motion but also to other instances in gait when muscles are contracting nearly isometrically. Recent human ultrasound studies have reported near-isometric behavior during walking, for example in the vastus lateralis in early stance (7), and the medial gastrocnemius through much of the stance phase (11, 20). Simply approximating metabolic cost as proportional to the positive musculotendon work may yield an overestimate by not accounting for elastic savings, while estimating metabolic cost from muscle work alone may yield an underestimate by neglecting the cost of producing force cyclically. The contribution of elastic work is well recognized and has been incorporated into complex musculoskeletal models of walking (1, 28). Our results suggest the possibility of quantifying the cost of cyclical force production as well, although further experiments are needed to generalize to other muscles.

We examined a relatively simple bouncing task. Although the extreme simplicity of bouncing makes it quite different from locomotion, it was intended to isolate a cost originally proposed for the energetics of human walking (17). The presence of series elasticity presents the opportunity to avoid muscle work by producing isometric force, for example to swing the leg or bounce about the ankles. In some cases, the amount of work might be minimized by producing high forces in very short bursts (18), yet such extremes are often avoided in favor of intermediate forces with nonzero work (19), suggesting that there is some cost for producing high forces without work. The hypothesized cost of producing cyclic force may therefore help determine preferred patterns for locomotion and other movements.

GRANTS

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DC-006466.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J. C. Dean is currently affiliated with the Medical University of South Carolina.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anderson FC, Pandy MG. Dynamic optimization of human walking. J Biomech Eng 123: 381–390, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bach TM, Chapman AE, Calvert TW. Mechanical resonance of the human body during voluntary oscillations about the ankle joint. J Biomech 16: 85–90, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brockway JM. Derivation of formulae used to calculate energy expenditure in man. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr 41: 463–471, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cavagna GA. Force platforms as ergometers. J Appl Physiol 39: 174–179, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cavagna GA, Saibene FP, Margaria R. Mechanical work in running. J Appl Physiol 19: 249–256, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chasiotis D, Bergström M, Hultman E. ATP utilization and force during intermittent and continuous muscle contractions. J Appl Physiol 63: 167–174, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chleboun GS, Busic AB, Graham KK, Stuckey HA. Fascicle length change of the human tibialis anterior and vastus lateralis during walking. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 37: 372–379, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doke J, Kuo AD. Energetic cost of producing cyclic muscle force, rather than work, to swing the human leg. J Exp Biol 210: 2390–2398, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doke J, Donelan JM, Kuo AD. Mechanics and energetics of swinging the human leg. J Exp Biol 208: 439–445, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farley CT, Blickhan R, Saito J, Taylor CR. Hopping frequency in humans: a test of how springs set stride frequency in bouncing gaits. J Appl Physiol 71: 2127–2132, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fukunaga T, Kubo K, Kawakami Y, Fukashiro S, Kanehisa H, Maganaris CN. In vivo behaviour of human muscle tendon during walking. Proc Biol Sci 268: 229–233, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hof AL. In vivo measurement of the series elasticity release curve of human triceps surae muscle. J Biomech 31: 793–800, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hof AL, Elzinga H, Grimmius W, Halbertsma JPK. Speed dependence of averaged EMG profiles in walking. Gait Posture 16: 78–86, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hof AL, Van Zandwijk JP, Bobbert MF. Mechanics of human triceps surae muscle in walking, running and jumping. Acta Physiol Scand 174: 17–30, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hogan MC, Ingham E, Kurdak SS. Contraction duration affects metabolic energy cost and fatigue in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 274: E397–E402, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawakami Y, Muraoka T, Ito S, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T. In vivo muscle fibre behaviour during counter-movement exercise in humans reveals a significant role for tendon elasticity. J Physiol 540: 635–646, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuo AD. A simple model of bipedal walking predicts the preferred speed-step length relationship. J Biomech Eng 123: 264–269, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuo AD. Energetics of actively powered locomotion using the simplest walking model. J Biomech Eng 124: 113–120, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuo AD, Donelan JM, Ruina A. Energetic consequences of walking like an inverted pendulum: step-to-step transitions. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 33: 88–97, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lichtwark GA, Bougoulias K, Wilson AM. Muscle fascicle and series elastic element length changes along the length of the human gastrocnemius during walking and running. J Biomech 40: 157–164, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Margaria R. Positive and negative work performances and their efficiencies in human locomotion. Int Z Angew Physiol 25: 339–351, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Margaria R, Cerretelli P, Aghemo P, Sassi G. Energy cost of running. J Appl Physiol 18: 367, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roberts TJ, Kram R, Weyand PG, Taylor CR. Energetics of bipedal running. I. Metabolic cost of generating force. J Exp Biol 201: 2745–2751, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts TJ, Marsh RL, Weyand PG, Taylor CR. Muscular force in running turkeys: the economy of minimizing work. Science 275: 1113, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryschon TW, Fowler MD, Wysong RE, Anthony A, Balaban RS. Efficiency of human skeletal muscle in vivo: comparison of isometric, concentric, and eccentric muscle action. J Appl Physiol 83: 867–874, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takeshita D, Shibayama A, Muraoka T, Muramatsu T, Nagano A, Fukunaga T, Fukashiro S. Resonance in the human medial gastrocnemius muscle during cyclic ankle bending exercise. J Appl Physiol 101: 111–118, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thys H, Cavagna GA, Margaria R. The role played by elasticity in an exercise involving movements of small amplitude. Pflügers Arch 354: 281–286, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Umberger BR. Stance and swing phase costs in human walking. J R Soc Interface 7: 1329–1340, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.