Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated that methyl jasmonate (MeJA) induces stomatal closure dependent on change of cytosolic free calcium concentration in guard cells. However, these molecular mechanisms of intracellular Ca2+ signal perception remain unknown. Calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) function as Ca2+ signal transducers in various plant physiological processes. It has been reported that four Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) CDPKs, CPK3, CPK6, CPK4, and CPK11, are involved in abscisic acid signaling in guard cells. It is also known that there is an interaction between MeJA and abscisic acid signaling in guard cells. In this study, we examined the roles of these CDPKs in MeJA signaling in guard cells using Arabidopsis mutants disrupted in the CDPK genes. Disruption of the CPK6 gene impaired MeJA-induced stomatal closure, but disruption of the other CDPK genes did not. Despite the broad expression pattern of CPK6, we did not find other remarkable MeJA-insensitive phenotypes in the cpk6-1 mutant. The whole-cell patch-clamp analysis revealed that MeJA activation of nonselective Ca2+-permeable cation channels is impaired in the cpk6-1 mutant. Consistent with this result, MeJA-induced transient cytosolic free calcium concentration increments were reduced in the cpk6-1 mutant. MeJA failed to activate slow-type anion channels in the cpk6-1 guard cells. Production of early signal components, reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide, in guard cells was elicited by MeJA in the cpk6-1 mutant as in the wild type. These results provide genetic evidence that CPK6 has a different role from CPK3 and functions as a positive regulator of MeJA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells.

Guard cells, which form stomatal pores in the leaf epidermis of higher plants, can respond to various environmental stimuli, including light, drought, and pathogen infection (Israelsson et al., 2006; Melotto et al., 2006; Shimazaki et al., 2007). To regulate carbon dioxide uptake for photosynthesis, transpirational water loss, and innate immunity adequately, plants have developed a fine-tuned signal transduction system in guard cells.

The volatile phytohormone methyl jasmonate (MeJA) regulates various physiological processes, including pollen maturation, tendril coiling, and responses to wounding and pathogen attack (Liechti and Farmer, 2002; Turner et al., 2002). Similar to abscisic acid (ABA), MeJA plays a role in the induction of stomatal closure (Gehring et al., 1997; Suhita et al., 2003, 2004). Jasmonate-induced stomatal closure has been observed in various plant species, including Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Suhita et al., 2004; Munemasa et al., 2007; Saito et al., 2008), Hordeum vulgare (Tsonev et al., 1998), Commelina benghalensis (Raghavendra and Reddy, 1987), Vicia faba (Liu et al., 2002), Nicotiana glauca (Suhita et al., 2003), Paphiopedilum supersuk (Gehring et al., 1997), and Paphiopedilum tonsum (Gehring et al., 1997). These findings suggest that jasmonate-induced stomatal closure is one of the fundamental physiological responses in plants.

Calcium has been shown to serve as an important second messenger for the regulation of stomatal movement (Roelfsema and Hedrich, 2007; Kudla et al., 2010). ABA induces stomatal closure via the elevation of cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt). ABA activates guard cell plasma membrane nonselective Ca2+-permeable cation (ICa) channels, which mediate Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000), and also induces Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (Leckie et al., 1998; Grabov and Blatt, 1999; Garcia-Mata et al., 2003; Lemtiri-Chlieh et al., 2003). ICa channels open on membrane hyperpolarization (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000), and ABA activation of ICa channels requires reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Kwak et al., 2003) and protein phosphorylation (Köhler and Blatt, 2002). ABA-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores is mediated by several second messengers, including nitric oxide (NO; Garcia-Mata et al., 2003; Sokolovski et al., 2005).

It has been shown that MeJA-induced stomatal closure is inhibited by Ca2+ channel blockers and calmodulin inhibitors (Suhita et al., 2003, 2004). Additionally, our previous study revealed that MeJA activates guard cell plasma membrane ICa channels and that MeJA activation of ICa channels is abolished in the MeJA-insensitive mutant coi1 (Munemasa et al., 2007). Activation of ICa channels has been proposed to contribute to [Ca2+]cyt elevation in guard cell ABA signaling (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000). These findings suggest that cytosolic Ca2+ serves as an important second messenger in MeJA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells.

Calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) are unique enzymes found in plants and some protozoa and are characterized as [Ca2+]cyt sensors in plants. Recently, Mori et al. (2006) and Zhu et al. (2007) suggested that four Arabidopsis CDPKs, CPK3, CPK6, CPK4, and CPK11, are involved in ABA-induced stomatal closure. There are functional redundancies between CPK3 and CPK6 (Mori et al., 2006) and between CPK4 and CPK11 (Zhu et al., 2007). CPK4 and CPK11 phosphorylate the ABA-responsive transcriptional factors ABF1 and ABF4 (AREB2) in vitro (Zhu et al., 2007). It was revealed that CPK3 and CPK6 are essential factors for ABA activation of ICa channels and slow-type (S-type) anion channels of guard cell plasma membrane, but downstream targets of CPK3 and CPK6 remain unknown (Mori et al., 2006). It has been reported that MeJA signaling and ABA signaling are partially overlapping and form a signaling network in guard cells (Suhita et al., 2003, 2004; Munemasa et al., 2007; Saito et al., 2008). These findings lead us to hypothesize that these CDPKs function as [Ca2+]cyt sensors in the MeJA signaling in guard cells.

In this study, we examined the roles of four CDPKs, CPK3, CPK6, CPK4, and CPK11, in MeJA-induced stomatal closure using a reverse genetic approach. We analyzed the stomatal phenotypes of these CDPK mutants and found that the cpk6 mutation impaired MeJA-induced stomatal closure. In CPK6 disruption mutants, MeJA activation of ICa channels and S-type anion channels was disrupted. We also addressed the roles of CPK6 in the production of early signal components, ROS and NO, in guard cell MeJA signaling. Our results suggest that CPK6 functions as a positive regulator in MeJA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells.

RESULTS

Impairment of MeJA-Induced Stomatal Closure in cpk6 Mutants

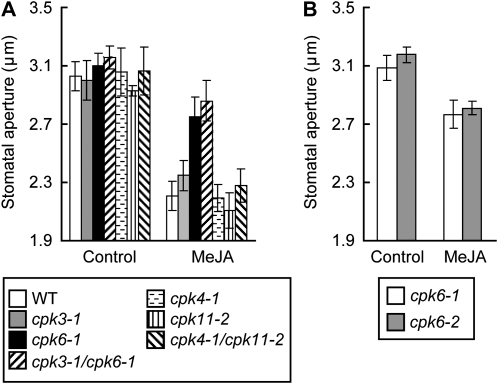

To identify CDPKs that are involved in MeJA signaling in guard cells, the effect of MeJA on stomatal aperture was examined in four single Arabidopsis CDPK mutants, cpk3-1, cpk6-1, cpk4-1, and cpk11-2, and two double mutants, cpk3-1/cpk6-1 and cpk4-1/cpk11-2. Exogenous application of 10 μm MeJA induced stomatal closure in the single cpk3-1, cpk4-1, and cpk11-2 mutants and the double cpk4-1/cpk11-2 mutant similar to the wild type (Fig. 1A). The single cpk6-1 and double cpk3-1/cpk6-1 mutants showed MeJA insensitivity in stomatal closure. MeJA-induced stomatal closure was also impaired in another cpk6 mutant allele, cpk6-2 (Fig. 1B), suggesting that gene disruption in CPK6 confers the MeJA insensitivity. Mori et al. (2006) showed that CPK6 is expressed in mesophyll cells as well as in guard cells. We also found CPK6 expression in flowers, stems, cauline leaves, and roots (Supplemental Fig. S1A). In addition to stomatal movements, we checked the effects of MeJA on the expression of the MeJA-responsive genes VSP1 and VSP2 (Berger et al., 1995; Ellis and Turner, 2001; Liu et al., 2005) and on root growth (Staswick et al., 1992; Feys et al., 1994) in the cpk6-1 mutant. However, we could not find any remarkable phenotype of the cpk6-1 mutant in these observations (Supplemental Fig. S1, B and C).

Figure 1.

MeJA-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis CPK3, CPK6, CPK4, and CPK11 gene disruption mutants. A, MeJA-induced stomatal closure in the wild type (WT) and cpk3-1, cpk6-1, cpk3-1/cpk6-1, cpk4-1, cpk11-2, and cpk4-1/11- 2 mutants. B, MeJA-induced stomatal closure in the cpk6-1 and cpk6-2 mutants. Twenty averages from three independent experiments (60 total stomata per bar) are shown. Error bars represent se.

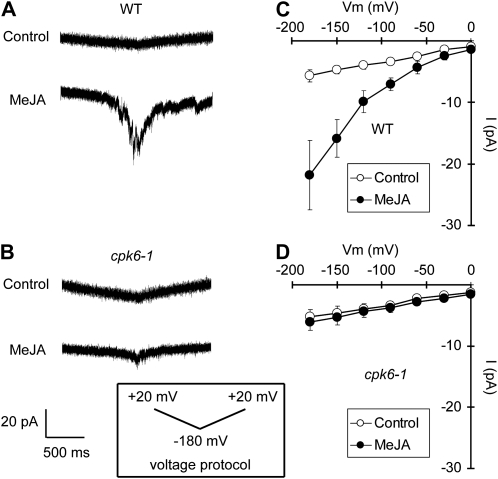

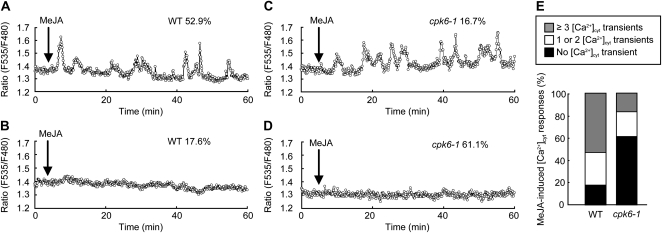

Impairment of Activation of ICa Currents and Elevation of [Ca2+]cyt by MeJA in cpk6-1 Guard Cells

Hyperpolarization-activated plasma membrane ICa channels function in guard cell ABA signaling (Grabov and Blatt, 1998; Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000). ROS production (Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Kwak et al., 2003) and protein phosphorylation (Köhler and Blatt, 2002) are involved in the regulation of ICa channel activity. The ICa channels are also activated by exogenous application of MeJA (Munemasa et al., 2007). We examined the effects of the CPK6 disruption on MeJA activation of ICa channels. MeJA activated ICa currents in wild-type guard cell protoplasts (GCPs; P < 0.05 at −180 mV; Fig. 2, A and C) but did not activate ICa currents in cpk6-1 GCPs (P = 0.71 at −180 mV; Fig. 2, B and D) and cpk6-2 GCPs (P = 0.71 at −180 mV; Supplemental Fig. S2A). Activation of ICa channels contributes to the elevation of guard cell [Ca2+]cyt (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000). To assess the effect of impairment in MeJA activation of ICa channels on [Ca2+]cyt status in cpk6-1 guard cells, we conducted guard cell [Ca2+]cyt imaging using a Ca2+ reporter protein, yellow cameleon 3.6 (Nagai et al., 2004; Young et al., 2006). Three or more transient [Ca2+]cyt increments were observed in 52.9% of wild-type guard cells treated with 10 μm MeJA (n = 9 of 17 cells; Fig. 3, A and E), and no transient [Ca2+]cyt increment was observed in 17.6% of guard cells treated with 10 μm MeJA (n = 3 of 17 cells; Fig. 3, B and E). Compared with the wild type, a higher percentage of cells with no [Ca2+]cyt transient was observed in cpk6-1 guard cells (61.1%; n = 11 of 18 cells; Fig. 3, D and E). Three or more [Ca2+]cyt transients induced by MeJA were observed in only 16.7% of cpk6-1 guard cells (n = 3 of 18 cells; Fig. 3, C and E). We tested the effects of an ICa channel blocker, LaCl3 (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000), on MeJA-induced transient [Ca2+]cyt increments. In wild-type guard cells pretreated with 50 μm LaCl3, MeJA-induced transient [Ca2+]cyt increments were not observed (100%; n = 16 of 16 cells; data not shown). These results suggest that CPK6 contributes to [Ca2+]cyt elevation by regulating ICa channel activity during MeJA-induced stomatal closure.

Figure 2.

ICa currents in wild-type GCPs and cpk6-1 GCPs. A, ICa currents in wild-type (WT) GCPs treated without MeJA (top trace) or with 10 μm MeJA (bottom trace). B, ICa currents in cpk6-1 GCPs treated without MeJA (top trace) or with 10 μm MeJA (bottom trace). C, Current-voltage relationships for MeJA activation of ICa currents in wild-type GCPs (n = 8) as recorded in A (white circles, control; black circles, 10 μm MeJA). D, Current-voltage relationships for MeJA activation of ICa currents in cpk6-1 GCPs (n = 6) as recorded in B (white circles, control; black circles, 10 μm MeJA). A ramp voltage protocol from +20 to −180 mV (holding potential, 0 mV; ramp speed, 200 mV s−1) was used. GCPs were treated with 10 μm MeJA for 1 h before recordings. After making the whole-cell configuration, ICa currents were recorded 16 times for each GCP.

Figure 3.

MeJA-induced [Ca2+]cyt increments in wild-type (WT) and cpk6-1 guard cells. A, A representative fluorescence emission ratio (535:480 nm) showing transient [Ca2+]cyt increments in 10 μm MeJA-treated wild-type guard cells (nine of 17 cells = 52.9%). B, A representative fluorescence emission ratio (535:480 nm) showing no transient [Ca2+]cyt increment in 10 μm MeJA-treated wild-type guard cells (three of 17 cells = 17.6%). C, A representative fluorescence emission ratio (535:480 nm) showing transient [Ca2+]cyt increments in 10 μm MeJA-treated cpk6-1 guard cells (three of 18 cells = 16.7%). D, A representative fluorescence emission ratio (535:480 nm) showing no transient [Ca2+]cyt increment in 10 μm MeJA-treated cpk6-1 guard cells (11 of 18 cells = 61.1%). E, Stack column representation of the number of MeJA-induced transient [Ca2+]cyt increments in wild-type guard cells (n = 17) and cpk6-1 guard cells (n = 18).

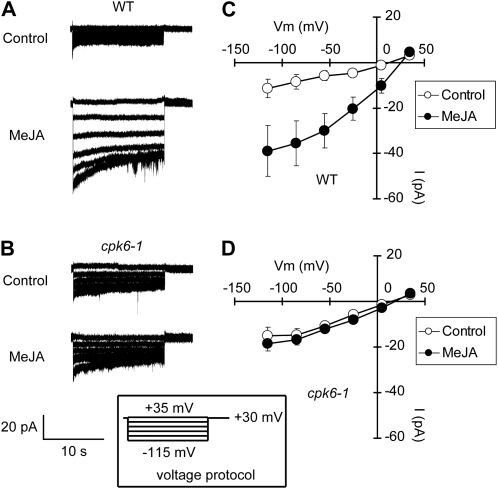

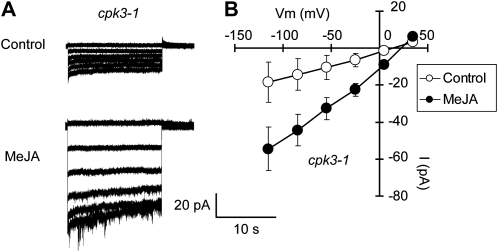

Impairment of Activation of S-Type Anion Currents by MeJA in cpk6-1 Guard Cells

Our previous results demonstrated that activation of S-type anion channels is indispensable for MeJA-induced stomatal closure (Munemasa et al., 2007) and that CPK6 functions as a positive regulator of S-type anion channels in ABA signaling in guard cells (Mori et al., 2006). In this study, we examined MeJA activation of S-type anion channels in the cpk6-1 mutant using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique. MeJA activated S-type anion currents in wild-type GCPs (P < 0.04 at –115 mV; Fig. 4, A and C). In contrast, MeJA failed to activate S-type anion currents in cpk6-1 GCPs (P = 0.48 at –115 mV; Fig. 4, B and D) and cpk6-2 GCPs (P = 0.53 at −115 mV; Supplemental Fig. S2B). These results are consistent with the stomatal phenotype of the cpk6 mutants shown in Figure 1. In cpk3-1 GCPs, MeJA activated S-type anion currents similar to wild-type GCPs (P < 0.05 at –115 mV; Fig. 5). This result is consistent with the result that MeJA induces stomatal closure in the cpk3-1 mutant (Fig. 1A). Allen et al. (2002) and Siegel et al. (2009) indicated that the increased [Ca2+]cyt was required for ABA or extracellular high [Ca2+] activation of S-type anion channels. In this paper, we also used a pipette solution with 2 μm [Ca2+] to measure S-type anion channel activity. Note that similar to several previous studies (Allen et al., 2002; Mori et al., 2006; Munemasa et al., 2007; Siegel et al., 2009), only small whole-cell currents were observed in MeJA-untreated GCPs.

Figure 4.

MeJA activation of S-type anion currents in wild-type GCPs and cpk6-1 GCPs. A, S-type anion currents in wild-type (WT) GCPs treated without MeJA (top trace) or 10 μm MeJA (bottom trace). B, S-type anion currents in cpk6-1 GCPs treated without MeJA (top trace) or 10 μm MeJA (bottom trace). C, Steady-state current-voltage relationships for MeJA activation of S-type anion currents in wild-type GCPs as recorded in A (white circles, control; black circles, 10 μm MeJA). D, Steady-state current-voltage relationships for MeJA activation of S-type anion currents in cpk6-1 GCPs as recorded in B (white circles, control; black circles, 10 μm MeJA). The voltage protocol was stepped up from +35 mV to −115 mV in 30-mV decrements (holding potential, +30 mV). GCPs were treated with 10 μm MeJA for 2 h before recordings. Note that [Ca2+]cyt was buffered to 2 μm. Each data point was obtained from at least seven GCPs. Error bars represent se.

Figure 5.

MeJA activation of S-type anion currents in cpk3-1 GCPs. A, S-type anion currents in wild-type GCPs treated with 0 μm MeJA (top trace) or 10 μm MeJA (bottom trace). B, Steady-state current-voltage relationships for MeJA activation of S-type anion currents in wild-type GCPs as recorded in A (white circles, control; black circles, 10 μm MeJA). GCPs were treated with 10 μm MeJA for 2 h before recordings. Note that [Ca2+]cyt was buffered to 2 μm. Each data point was obtained from at least six GCPs. Error bars represent se.

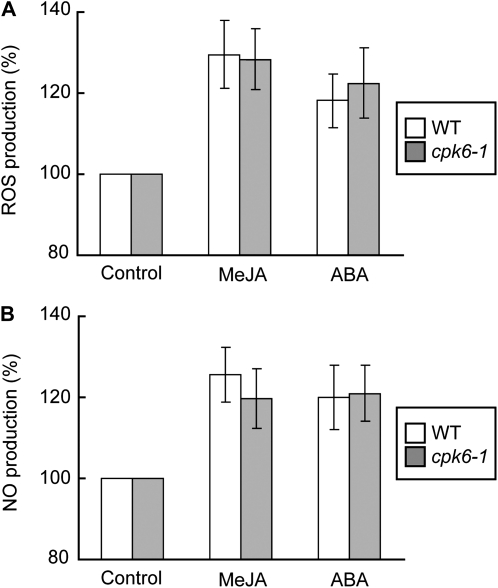

Effects of the cpk6-1 Mutation on the Production of ROS and NO Induced by MeJA in Guard Cells

To clarify how CPK6 mediates MeJA signaling in guard cells, we evaluated the production of ROS and NO, which function as early signal components in guard cells. ROS produced by two NAD(P)H oxidases, AtrbohD and AtrbohF, are important second messengers and function upstream of ICa channel activation in Arabidopsis guard cells (Kwak et al., 2003). These two NAD(P)H oxidases are also involved in guard cell MeJA signaling (Suhita et al., 2004). Recently, it has been suggested that plant NAD(P)H oxidases are phosphorylated and activated by CDPKs (Kobayashi et al., 2007; Ogasawara et al., 2008). We tested the effects of CPK6 disruption on MeJA-induced ROS production in guard cells using the ROS-detection fluorescent dye, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA). We found that MeJA evoked ROS production in cpk6-1 guard cells as well as in wild-type guard cells (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Production of ROS and NO induced by MeJA and ABA in wild-type and cpk6-1 guard cells. A, Effects of MeJA (10 μm) and ABA (10 μm) on ROS production in wild-type (WT) guard cells (n = 4; white bars) and in cpk6-1 guard cells (n = 4; gray bars). B, Effects of MeJA (10 μm) and ABA (10 μm) on NO production in wild-type guard cells (n = 4; white bars) and in cpk6-1 guard cells (n = 4; gray bars). The vertical scale represents the percentage of H2DCF-DA fluorescence levels (ROS) and DAF-2DA fluorescence levels (NO) when fluorescence intensities of MeJA- or ABA-treated cells are normalized to a control value taken as 100% for each experiment. Each data point was obtained from more than 24 total guard cells. Error bars represent se.

NO also functions as an important second messenger in MeJA signaling in guard cells. It has been suggested that NO mediates Ca2+ release from intracellular stores during ABA-induced stomatal closure (Garcia-Mata et al., 2003; Sokolovski et al., 2005). To further understand the roles of CPK6 in MeJA signaling, we evaluated MeJA-induced NO production in cpk6-1 guard cells using the NO-detection fluorescent dye, 4,5-diaminofluorescein-2 diacetate (DAF-2DA). In wild-type guard cells, MeJA evoked NO production (Fig. 6B), which is consistent with our previous results (Munemasa et al., 2007). MeJA-induced NO production was also observed in cpk6-1 guard cells (Fig. 6B). The roles of CPK6 in ROS and NO production induced by ABA in guard cells have not yet been examined (Mori et al., 2006). We found that ROS and NO production induced by ABA were not impaired either in the cpk6-1 mutant (Fig. 6) or in the cpk3-1/cpk6-1 double mutant (data not shown), which show stronger ABA-insensitive phenotypes than the single cpk3 and cpk6 mutants (Mori et al., 2006).

DISCUSSION

The cpk6-1 Mutant Did Not Show MeJA-Induced Stomatal Closure

Previous studies have shown the similarity of ABA- and MeJA-signaling pathways that induce stomatal closure (Suhita et al., 2003, 2004; Munemasa et al., 2007; Saito et al., 2008; Islam et al., 2009, 2010). Although roles of second messengers, such as [Ca2+]cyt, ROS, and NO, were elucidated in ABA signaling in guard cells, those in MeJA signaling have not been examined. Recent studies have shown that CDPKs play unambiguous roles in ABA signaling in guard cells (Mori et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2007; Geiger et al., 2010). In this study, we present the involvement of CPK6 in MeJA-induced stomatal closure as well as in ABA signaling. This finding provides evidence for a common molecular mechanism in Ca2+ recognition in guard cells.

[Ca2+]cyt elevation has been shown to be an essential step in early guard cell MeJA signaling (Suhita et al., 2003, 2004; Munemasa et al., 2007). Although pharmacological experiments have implied that CDPKs are involved in MeJA signaling in guard cells (Suhita et al., 2003, 2004), the mechanism by which elevated [Ca2+]cyt is linked to downstream signal components in guard cell MeJA signaling is still unclear. In this study, to identify CDPKs functioning in guard cell MeJA signaling, we examined four Arabidopsis CDPK disruption mutants that show ABA-insensitive stomatal phenotypes (Mori et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2007). We found that the cpk6-1 and cpk6-2 mutants showed MeJA insensitivity in stomatal closure, while cpk3-1, cpk4-1, and cpk11-2 mutants did not (Fig. 1), suggesting that CPK6 functions as a positive regulator of MeJA signaling in guard cells. Mori et al. (2006) have revealed that stomata of cpk3/cpk6 double mutants were less sensitive to ABA than those of single cpk3 and cpk6 mutants, suggesting that CPK3 and CPK6 are involved in ABA signaling in guard cells with their partial functional redundancy. Interestingly, our data indicate that the single gene disruption of CPK6 but not CPK3 reduced MeJA sensitivity in stomatal closure (Fig. 1). This result suggests that CPK3 could be involved in ABA signaling but not in MeJA signaling and that the function of CPK6 is not completely overlapping with that of CPK3 in the phytohormone signaling network in guard cells. It has been demonstrated that CPK4 and CPK11 mediate ABA signaling in guard cells and phosphorylate the ABA-responsive transcriptional factors ABF1 and ABF4 (AREB2) in vitro (Zhu et al., 2007). The results from Figure 1A imply that MeJA does not induce stomatal closure via ABF1- and ABF4 (AREB2)-dependent pathways.

Impairment of MeJA Activation of ICa Channels in cpk6-1 Guard Cells

Activation of plasma membrane ICa channels contributes to the elevation of [Ca2+]cyt in guard cells and is elicited by extracellular application of hydrogen peroxide, fungal elicitors, MeJA, and ABA (Hamilton et al., 2000; Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001; Klüsener et al., 2002; Munemasa et al., 2007). It has been suggested that protein phosphorylation is necessary for the activation of ICa channels in Vicia guard cells (Köhler and Blatt, 2002). Mori et al. (2006) showed that in GCPs of cpk6 mutants, ABA failed to activate ICa channels. In this study, we found that MeJA also failed to activate ICa channels in cpk6 GCPs (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. S2A), indicating that the [Ca2+]cyt sensor, CPK6, is essential for the regulation of ICa channel activity. Hamilton et al. (2000) showed that increasing [Ca2+]cyt suppressed the open probability of ICa channels. Similar to this study, our results here suggest that [Ca2+]cyt itself regulates ICa channel activity.

Guard cell [Ca2+]cyt imaging using yellow cameleon 3.6 (Mori et al., 2006; Young et al., 2006) revealed that MeJA induced transient increments of [Ca2+]cyt in wild-type guard cells (Fig. 3, A, B, and E) like ABA (Gilroy et al., 1991; Allen et al., 1999, 2000). Compared with the wild type, a higher percentage of nonresponding cells was observed in the cpk6-1 mutant (Fig. 3, C–E). MeJA-induced [Ca2+]cyt transient increments were reduced but not completely abolished in cpk6-1 guard cells (Fig. 3), while MeJA activation of ICa was completely abolished (Fig. 2). It has been supposed that in addition to Ca2+ influx from extracellular space mediated by plasma membrane ICa channels, Ca2+ release from intracellular stores contributes to [Ca2+]cyt elevation in guard cells (Leckie et al., 1998; Grabov and Blatt, 1999; Garcia-Mata et al., 2003; Lemtiri-Chlieh et al., 2003). Our results here suggest that in cpk6-1 guard cells, ICa channel activity is abolished but that these other Ca2+ transport pathways may be still active and can release Ca2+ to cytosol from intracellular stores. Several reports has shown that Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in guard cells is mediated by NO (Garcia-Mata et al., 2003; Sokolovski et al., 2005). Previously, we reported that a NO-specific scavenger, 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide, partly inhibited MeJA-induced stomatal closure (Munemasa et al., 2007). However, pretreatment with 100 μm 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide did not reduce transient increments of [Ca2+]cyt induced by MeJA (Supplemental Fig. S3), indicating that NO production might not be involved in increments of [Ca2+]cyt induced by MeJA.

Impairment of MeJA Activation of S-Type Anion Channels in cpk6-1 Guard Cells

ABA activation of S-type anion channels triggers a long-term plasma membrane depolarization, which is the primary driving force for K+ efflux from guard cells (Schroeder et al., 1987; Schroeder and Keller, 1992; Schmidt et al., 1995; Pei et al., 1997). Similar to ABA, MeJA activates S-type anion channels, and the activation is disrupted in the MeJA-insensitive mutant coi1 (Munemasa et al., 2007). In this study, we showed that MeJA activation of S-type anion channels was disrupted in cpk6-1 and cpk6-2 GCPs (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S2B). CPK6 is also implicated in the ABA activation of S-type anion channels (Mori et al., 2006). These results indicate that CPK6 is closely associated with S-type anion channel activation in the phytohormone signaling network in guard cells. Arabidopsis SLOW ANION CHANNEL-ASSOCIATED1 (SLAC1) was identified as a guard cell plasma membrane protein that mediated S-type anion channel activity (Negi et al., 2008; Vahisalu et al., 2008). Recently, Geiger et al. (2010) showed that CPKs directly interact with SLAC1 and activate it. The activation was inhibited by protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C). They also confirmed direct interaction between CPK6 and SLAC1 using bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis in Xenopus oocytes. Previously, we reported that MeJA failed to induce stomatal closure in the ABA-insensitive PP2C mutants abi1-1 and abi2-1 (Munemasa et al., 2007). Together with these findings, our results here imply that MeJA activates CPK6 via down-regulation of the PP2C activity, resulting in the activation of SLAC1. In the future, it should be elucidated how MeJA affects core components of early ABA signaling and ABA receptors PYR/PYL/RCAR, PP2Cs, SnRKs, and CDPKs. Note that in guard cell ABA signaling, S-type anion channels are also activated by a [Ca2+]cyt-independent pathway (Grabov et al., 1997; Levchenko et al., 2005; Geiger et al., 2009). The [Ca2+]cyt-independent pathway in guard cell MeJA signaling remains to be investigated.

We found that CPK3 gene disruption, which reduced ABA sensitivity in guard cells (Mori et al., 2006), did not affect the MeJA activation of S-type anion channels (Fig. 5). This result is consistent with the stomatal phenotype of the cpk3-1 mutant shown in Figure 1A, which provides evidence that CPK6 plays different roles from CPK3 in guard cell signaling.

The Roles of CPK6 in MeJA Regulation of ROS and NO Production in Guard Cells

ROS are key players during stomatal closure (Pei et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2001; Suhita et al., 2004). In Arabidopsis guard cells, two NAD(P)H oxidases, AtrbohD and AtrbohF, catalyze the ROS production observed during ABA-induced and MeJA-induced stomatal closure (Kwak et al., 2003; Suhita et al., 2004).Recently, Kobayashi et al. (2007) showed that two potato (Solanum tuberosum) CDPKs, StCDPK4 and StCDPK5, directly phosphorylated StrbohB in vitro and regulated the oxidative burst. The closest homolog of StCDPK4 and StCDPK5 in Arabidopsis is CPK6. Ogasawara et al. (2008) suggest that the activity of AtrbohD to produce ROS is regulated by phosphorylation. These previous findings led us to examine the effects of CPK6 disruption on ROS production in guard cells induced by MeJA. Similar to ROS, NO also functions as an important second messenger in MeJA signaling (Orozco-Cárdenas and Ryan, 2002; Huang et al., 2004; Munemasa et al., 2007) and ABA signaling (Desikan et al., 2002; Neill et al., 2002; Guo et al., 2003), while the mechanism of NO synthesis in plants remains controversial. Recent studies revealed the roles of [Ca2+]cyt in NO production in plant cells (Gonugunta et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2008). In this study, we analyzed the effects of CPK6 disruption on NO production in guard cell MeJA signaling. Figure 6 shows that MeJA evoked the production of ROS and NO in the cpk6-1 guard cells, which is equivalent to ROS and NO production induced by MeJA in wild-type guard cells. These results suggest that CPK6 functions downstream of ROS and NO production in guard cell MeJA signaling.

Here, we clarified the roles of CPK6 in guard cell MeJA signaling. In guard cells, after perception by COI1 (Yan et al., 2009), MeJA induces the production of ROS and NO. The signal pathway of MeJA-induced ROS and NO production remains unclear. Although Suhita et al. (2004) suggested that Ca2+-binding proteins (e.g. CDPKs and calmodulins) mediate MeJA-induced ROS production, our data indicate that CPK6 seems not to be involved in ROS production induced by MeJA. MeJA evokes [Ca2+]cyt elevation via both activation of ICa channels and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (Suhita et al., 2003; Munemasa et al., 2007). Elevated [Ca2+]cyt could activate CPK6. Interestingly, in the cpk6 mutants, MeJA activation of ICa channels was impaired, suggesting that the CDPK regulates ICa channel activity by a feedback loop as proposed by Mori et al. (2006). CPK6 is also involved in the regulation of S-type anion channel activity. We cannot exclude pleiotropic and indirect effects of cpk6 mutation on this ion channel regulation. However, the provided results give strong evidence that CPK6 functions as a positive regulator of MeJA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells and has different roles from CPK3 in the phytohormone signaling network in guard cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth

Throughout this study, we used the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Columbia as the wild-type plant. Wild-type and cpk mutant plants were grown on a soil mixture of 70% (v/v) vermiculite (Asahi-kogyo) and 30% (v/v) Kureha soil (Kureha Chemical) in growth chambers at 22°C under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod with photon flux density of 80 μmol m−2 s−1.

Stomatal Aperture Measurements

Stomatal aperture measurements were performed as described previously (Pei et al., 1997; Murata et al., 2001; Munemasa et al., 2007). Excised rosette leaves were floated on medium containing 5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES-Tris (pH 6.15) for 2 h in the light to induce stomatal opening, followed by the addition of MeJA. After 2 h of incubation in the light, leaves were blended for 30 s and epidermal peels were collected. Twenty stomatal apertures were measured on each individual experiment.

Analysis of Gene Expression by Reverse Transcription-PCR

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-PCR were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plants were sprayed with 0.1% ethanol or 10 μm MeJA and kept in growth chambers for 2 h. Then, RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 3 μg of RNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa Bio). PCR was performed with 1 μL of reverse transcription reaction mixture using BIOTAQ DNA polymerase (Bioline). Primers used in PCR amplification are as follows: for CPK6, 5′-CTCTATATCTTACTAAGTGGTGTCCCG-3′ (CPK6F) and 5′-CTCAAACCTTCAAGGATTTAGCTGG-3′ (CPK6R); for VSP1, 5′-CTCTCTAGTATTCCCTACTACGC-3′ (VSPF) and 5′-GATTCTCGACAGTGACTTCTGAC-3′ (VSP1R); for VSP2, 5′-CTCTCTAGTATTCCCTACTACGC-3′ (VSPF) and 5′-GTCGAGAGTGACATTCTTCCACAAC-3′ (VSP2R); and for Actin2, 5′-TCTTAACCCAAAGGCCAACA-3′ (ACT2F) and 5′-CAGAATCCAGCACAATACCG-3′ (ACT2R).

Assay of Root Growth Inhibition

Seeds were sown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing MS salt mixture (Nihon Pharmaceutical), 2% (w/v) Suc, 3 mg L−1 thiamine hydrochloride, 0.5 mg L−1 pyridoxine hydrochloride, 5 mg L−1 nicotinic acid, and 0.5% (w/v) Gellan gum (San-Ei Gen). Plates were kept at 4°C for 4 d and then transferred to growth chambers in a vertical orientation. Five-day-old seedlings were transferred to MS plates containing 10 μm MeJA. After 5 d, root length was measured.

Electrophysiology

For whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of ICa and S-type anion currents, Arabidopsis GCPs were prepared from rosette leaves of 4- to 6-week-old plants by the enzymatic method described previously (Pei et al., 1997). Whole-cell currents were recorded as described previously (Munemasa et al., 2007). For ICa current measurements, the pipette solution contained 10 mm BaCl2, 0.1 mm dithiothreitol, 3 mm NADPH, 4 mm EGTA, and 10 mm HEPES-Tris (pH 7.1). The bath solution contained 100 mm BaCl2, 0.1 mm dithiothreitol, and 10 mm MES-Tris (pH 5.6; Pei et al., 2000; Murata et al., 2001). For S-type anion current measurements, the patch-clamp solutions contained 150 mm CsCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 6.7 mm EGTA, 5.58 mm CaCl2 (free Ca2+ concentration, 2 μm), 5 mm ATP, and 10 mm HEPES-Tris (pH 7.1) in the pipette and 30 mm CsCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES-Tris (pH 5.6) in the bath (Pei et al., 1997). In both cases, osmolarity was adjusted to 500 mmol kg−1 (pipette solutions) and 485 mmol kg−1 (bath solutions) with d-sorbitol.

Guard Cell [Ca2+]cyt Imaging

Arabidopsis yellow cameleon 3.6-expressing plants were used to examine [Ca2+]cyt changes in guard cells as described (Allen et al., 1999; Young et al., 2006) with slight modifications. The abaxial side of excised rosette leaves was softly mounted on a glass slide using a medical adhesive, followed by the removal of upper cell layers with a razor blade. The abaxial epidermal peels were kept in a solution containing 5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES-Tris (pH 6.15) under the light condition for 2 h. Then, the abaxial epidermal peels were treated with 10 μm MeJA by a peristatic pump after 5 min from the start of measurement. The cyan fluorescent protein and yellow fluorescent protein fluorescence in guard cells was captured and analyzed using the W-View System and AQUA COSMOS software (Hamamatsu Photonics).

Detection of ROS and NO

ROS production in guard cells was analyzed using H2DCF-DA (Lee et al., 1999; Murata et al., 2001; Suhita et al., 2004). Epidermal peels were incubated for 3 h in medium containing 5 mm KCl, 50 μm CaCl2, and 10 mm MES-Tris (pH 6.15), and then 50 μm H2DCF-DA was added to this medium. The epidermal tissues were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and then the excess dye was washed out. The dye-loaded tissues were treated with 10 μm MeJA or 10 μm ABA for 20 min, and then the fluorescence of guard cells was imaged and analyzed using AQUA COSMOS software. For NO detection in guard cells, 10 μm DAF-2DA was added instead of 50 μm H2DCF-DA (Foissner et al., 2000; Neill et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2004).

Statistical Analysis

Significance of differences between data sets was assessed by Student’s t test analysis in this paper, except for in Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure S3. In these figures, χ2 analysis was performed. We regarded differences at the level of P < 0.05 as significant.

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative numbers for the genes discussed in this article are as follows: CPK3 (At4g23650), CPK6 (At2g17290), CPK4 (At4g09570), CPK11 (At1g35670), VSP1 (At5g24780), VSP2 (At5g24770), and Actin2 (At3g18780).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. CPK6 expression and cpk6-1 mutant phenotype.

Supplemental Figure S2. ICa currents and S-type anion currents in cpk6-2.

Supplemental Figure S3. Effect of cPTIO on MeJA-induced [Ca2+]cyt increments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Seeds of cpk4-1, cpk11-2, and cpk4-1/cpk11-2 were kind gifts from Dr. Da-Peng Zhang (China Agricultural University).

References

- Allen GJ, Chu SP, Schumacher K, Shimazaki CT, Vafeados D, Kemper A, Hawke SD, Tallman G, Tsien RY, Harper JF, et al. (2000) Alteration of stimulus-specific guard cell calcium oscillations and stomatal closing in Arabidopsis det3 mutant. Science 289: 2338–2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GJ, Kwak JM, Chu SP, Llopis J, Tsien RY, Harper JF, Schroeder JI. (1999) Cameleon calcium indicator reports cytoplasmic calcium dynamics in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J 19: 735–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GJ, Murata Y, Chu SP, Nafisi M, Schroeder JI. (2002) Hypersensitivity of abscisic acid-induced cytosolic calcium increases in the Arabidopsis farnesyltransferase mutant era1-2. Plant Cell 14: 1649–1662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S, Bell E, Sadka A, Mullet JE. (1995) Arabidopsis thaliana Atvsp is homologous to soybean VspA and VspB, genes encoding vegetative storage protein acid phosphatases, and is regulated similarly by methyl jasmonate, wounding, sugars, light and phosphate. Plant Mol Biol 27: 933–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan R, Griffiths R, Hancock J, Neill S. (2002) A new role for an old enzyme: nitrate reductase-mediated nitric oxide generation is required for abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 16314–16318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C, Turner JG. (2001) The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 has constitutively active jasmonate and ethylene signal pathways and enhanced resistance to pathogens. Plant Cell 13: 1025–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys BJF, Benedetti CE, Penfold CN, Turner JG. (1994) Arabidopsis mutants selected for resistance to the phytotoxin coronatine are male sterile, insensitive to methyl jasmonate, and resistant to a bacterial pathogen. Plant Cell 6: 751–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foissner I, Wendehenne D, Langebartels C, Durner J. (2000) In vivo imaging of an elicitor-induced nitric oxide burst in tobacco. Plant J 23: 817–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mata C, Gay R, Sokolovski S, Hills A, Lamattina L, Blatt MR. (2003) Nitric oxide regulates K+ and Cl− channels in guard cells through a subset of abscisic acid-evoked signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 11116–11121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring CA, Irving HR, McConchie R, Parish RW. (1997) Jasmonates induce intracellular alkalinization and closure of Paphiopedilum guard cells. Ann Bot (Lond) 80: 485–489 [Google Scholar]

- Geiger D, Scherzer S, Mumm P, Marten I, Ache P, Matschi S, Liese A, Wellmann C, Al-Rasheid KA, Grill E, et al. (2010) Guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is regulated by CDPK protein kinases with distinct Ca2+ affinities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 8023–8028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger D, Scherzer S, Mumm P, Stange A, Marten I, Bauer H, Ache P, Matschi S, Liese A, Al-Rasheid KA, et al. (2009) Activity of guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is controlled by drought-stress signaling kinase-phosphatase pair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 21425–21430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy S, Fricker MD, Read ND, Trewavas AJ. (1991) Role of calcium in signal transduction of Commelina guard cells. Plant Cell 3: 333–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonugunta VK, Srivastava N, Puli MR, Raghavendra AS. (2008) Nitric oxide production occurs after cytosolic alkalinization during stomatal closure induced by abscisic acid. Plant Cell Environ 31: 1717–1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabov A, Blatt MR. (1998) Membrane voltage initiates Ca2+ waves and potentiates Ca2+ increases with abscisic acid in stomatal guard cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4778–4783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabov A, Blatt MR. (1999) A steep dependence of inward-rectifying potassium channels on cytosolic free calcium concentration increase evoked by hyperpolarization in guard cells. Plant Physiol 119: 277–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabov A, Leung J, Giraudat J, Blatt MR. (1997) Alteration of anion channel kinetics in wild-type and abi1-1 transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana guard cells by abscisic acid. Plant J 12: 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo FQ, Okamoto M, Crawford NM. (2003) Identification of a plant nitric oxide synthase gene involved in hormonal signaling. Science 302: 100–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DWA, Hills A, Köhler B, Blatt MR. (2000) Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane of stomatal guard cells are activated by hyperpolarization and abscisic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4967–4972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Stettmaier K, Michel C, Hutzler P, Mueller MJ, Durner J. (2004) Nitric oxide is induced by wounding and influences jasmonic acid signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 218: 938–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MM, Hossain MA, Jannat R, Munemasa S, Nakamura Y, Mori IC, Murata Y. (2010) Cytosolic alkalization and cytosolic calcium oscillation in Arabidopsis guard cells response to ABA and MeJA. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MM, Tani C, Watanabe-Sugimoto M, Uraji M, Jahan MS, Masuda C, Nakamura Y, Mori IC, Murata Y. (2009) Myrosinases, TGG1 and TGG2, redundantly function in ABA and MeJA signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1171–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israelsson M, Siegel RS, Young J, Hashimoto M, Iba K, Schroeder JI. (2006) Guard cell ABA and CO2 signaling network updates and Ca2+ sensor priming hypothesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9: 654–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klüsener B, Young JJ, Murata Y, Allen GJ, Mori IC, Hugouvieux V, Schroeder JI. (2002) Convergence of calcium signaling pathways of pathogenic elicitors and abscisic acid in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant Physiol 130: 2152–2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Ohura I, Kawakita K, Yokota N, Fujiwara M, Shimamoto K, Doke N, Yoshioka H. (2007) Calcium-dependent protein kinases regulate the production of reactive oxygen species by potato NADPH oxidase. Plant Cell 19: 1065–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler B, Blatt MR. (2002) Protein phosphorylation activates the guard cell Ca2+ channel and is a prerequisite for gating by abscisic acid. Plant J 32: 185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudla J, Batistič O, Hashimoto K. (2010) Calcium signals: the lead currency of plant information processing. Plant Cell 22: 541–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak JM, Mori IC, Pei ZM, Leonhardt N, Torres MA, Dangl JL, Bloom RE, Bodde S, Jones JDG, Schroeder JI. (2003) NADPH oxidase AtrbohD and AtrbohF genes function in ROS-dependent ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. EMBO J 22: 2623–2633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckie CP, McAinsh MR, Allen GJ, Sanders D, Hetherington AM. (1998) Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure mediated by cyclic ADP-ribose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 15837–15842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Choi H, Suh S, Doo IS, Oh KY, Choi EJ, Schroeder Taylor AT, Low PS, Lee Y. (1999) Oligogalacturonic acid and chitosan reduce stomatal aperture by inducing the evolution of reactive oxygen species from guard cells of tomato and Commelina communis. Plant Physiol 121: 147–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemtiri-Chlieh F, MacRobbie EAC, Webb AAR, Manison NF, Brownlee C, Skepper JN, Chen J, Prestwich GD, Brearley CA. (2003) Inositol hexakisphosphate mobilizes an endomembrane store of calcium in guard cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10091–10095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levchenko V, Konrad KR, Dietrich P, Roelfsema MR, Hedrich R. (2005) Cytosolic abscisic acid activates guard cell anion channels without preceding Ca2+ signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 4203–4208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechti R, Farmer EE. (2002) The jasmonate pathway. Science 296: 1649–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang SQ, Lou CH, Yu FY. (2002) Effect of localized scorch on the transport and distribution of exogenous jasmonic acid in Vicia faba. Acta Bot Sin 44: 164–167 [Google Scholar]

- Liu YL, Ahn JE, Datta S, Salzman RA, Moon J, Huyghues-Despointes B, Pittendrigh B, Murdock LL, Koiwa H, Zhu-Salzman K. (2005) Arabidopsis vegetative storage protein is an anti-insect acid phosphatase. Plant Physiol 139: 1545–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Smigel A, Tsai YC, Braam J, Berkowitz GA. (2008) Innate immunity signaling: cytosolic Ca2+ elevation is linked to downstream nitric oxide generation through the action of calmodulin or a calmodulin-like protein. Plant Physiol 148: 818–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotto M, Underwood W, Koczan J, Nomura K, He SY. (2006) Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell 126: 969–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori IC, Murata Y, Yang Y, Munemasa S, Wang YF, Andreoli S, Tiriac H, Alonso JM, Harper JF, Ecker JR, et al. (2006) CDPKs CPK6 and CPK3 function in ABA regulation of guard cell S-type anion- and Ca(2+)-permeable channels and stomatal closure. PLoS Biol 4: e327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munemasa S, Oda K, Watanabe-Sugimoto M, Nakamura Y, Shimoishi Y, Murata Y. (2007) The coronatine-insensitive 1 mutation reveals the hormonal signaling interaction between abscisic acid and methyl jasmonate in Arabidopsis guard cells: specific impairment of ion channel activation and second messenger production. Plant Physiol 143: 1398–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol Plant 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Pei ZM, Mori IC, Schroeder JI. (2001) Abscisic acid activation of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels in guard cells requires cytosolic NAD(P)H and is differentially disrupted upstream and downstream of reactive oxygen species production in abi1-1 and abi2-1 protein phosphatase 2C mutants. Plant Cell 13: 2513–2523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A. (2004) Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicators for Ca(2+) by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10554–10559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi J, Matsuda O, Nagasawa T, Oba Y, Takahashi H, Kawai-Yamada M, Uchimiya H, Hashimoto M, Iba K. (2008) CO2 regulator SLAC1 and its homologues are essential for anion homeostasis in plant cells. Nature 452: 483–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill SJ, Desikan R, Clarke A, Hancock JT. (2002) Nitric oxide is a novel component of abscisic acid signaling in stomatal guard cells. Plant Physiol 128: 13–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara Y, Kaya H, Hiraoka G, Yumoto F, Kimura S, Kadota Y, Hishinuma H, Senzaki E, Yamagoe S, Nagata K, et al. (2008) Synergistic activation of the Arabidopsis NADPH oxidase AtrbohD by Ca2+ and phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 283: 8885–8892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Cárdenas ML, Ryan CA. (2002) Nitric oxide negatively modulates wound signaling in tomato plants. Plant Physiol 130: 487–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Kuchitsu K, Ward JM, Schwarz M, Schroeder JI. (1997) Differential abscisic acid regulation of guard cell slow anion channels in Arabidopsis wild-type and abi1 and abi2 mutants. Plant Cell 9: 409–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Murata Y, Benning G, Thomine S, Klüsener B, Allen GJ, Grill E, Schroeder JI. (2000) Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 406: 731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra AS, Reddy KB. (1987) Action of proline on stomata differs from that of abscisic acid, g-substances, or methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol 83: 732–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema MRG, Hedrich R. (2007) Making sense out of Ca2+ signals: their role in regulating stomatal movements. Plant Cell Environ 33: 305–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N, Munemasa S, Nakamura Y, Shimoishi Y, Mori IC, Murata Y. (2008) Roles of RCN1, regulatory A subunit of protein phosphatase 2A, in methyl jasmonate signaling and signal crosstalk between methyl jasmonate and abscisic acid. Plant Cell Physiol 49: 1396–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C, Schelle I, Liao YJ, Schroeder JI. (1995) Strong regulation of slow anion channels and abscisic acid signaling in guard cells by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 9535–9539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Keller BU. (1992) Two types of anion channel currents in guard cells with distinct voltage regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 5025–5029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Raschke K, Neher E. (1987) Voltage dependence of K channels in guard-cell protoplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 4108–4112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K, Doi M, Assmann SM, Kinoshita T. (2007) Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 219–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RS, Xue S, Murata Y, Yang Y, Nishimura N, Wang A, Schroeder JI. (2009) Calcium elevation-dependent and attenuated resting calcium-dependent abscisic acid induction of stomatal closure and abscisic acid-induced enhancement of calcium sensitivities of S-type anion and inward-rectifying K channels in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J 59: 207–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolovski S, Hills A, Gay R, Garcia-Mata C, Lamattina L, Blatt MR. (2005) Protein phosphorylation is a prerequisite for intracellular Ca2+ release and ion channel control by nitric oxide and abscisic acid in guard cells. Plant J 43: 520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE, Su W, Howell SH. (1992) Methyl jasmonate inhibition of root growth and induction of a leaf protein are decreased in an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 6837–6840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhita D, Kolla VA, Vavasseur A, Raghavendra AS. (2003) Different signaling pathways involved during the suppression of stomatal opening by methyl jasmonate or abscisic acid. Plant Sci 164: 481–488 [Google Scholar]

- Suhita D, Raghavendra AS, Kwak JM, Vavasseur A. (2004) Cytoplasmic alkalization precedes reactive oxygen species production during methyl jasmonate- and abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure. Plant Physiol 134: 1536–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsonev TD, Lazova GN, Stoinova ZG, Popova LP. (1998) A possible role for jasmonic acid in adaptation of barley seedlings to salinity stress. J Plant Growth Regul 17: 153–159 [Google Scholar]

- Turner JG, Ellis C, Devoto A. (2002) The jasmonate signal pathway. Plant Cell (Suppl) 14: S153–S164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahisalu T, Kollist H, Wang YF, Nishimura N, Chan WY, Valerio G, Lamminmäki A, Brosché M, Moldau H, Desikan R, et al. (2008) SLAC1 is required for plant guard cell S-type anion channel function in stomatal signalling. Nature 452: 487–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Zhang C, Gu M, Bai Z, Zhang W, Qi T, Cheng Z, Peng W, Luo H, Nan F, et al. (2009) The Arabidopsis CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 protein is a jasmonate receptor. Plant Cell 21: 2220–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JJ, Mehta S, Israelsson M, Godoski J, Grill E, Schroeder JI. (2006) CO(2) signaling in guard cells: calcium sensitivity response modulation, a Ca(2+)-independent phase, and CO(2) insensitivity of the gca2 mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7506–7511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang L, Dong F, Gao J, Galbraith DW, Song CP. (2001) Hydrogen peroxide is involved in abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure in Vicia faba. Plant Physiol 126: 1438–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SY, Yu XC, Wang XJ, Zhao R, Li Y, Fan RC, Shang Y, Du SY, Wang XF, Wu FQ, et al. (2007) Two calcium-dependent protein kinases, CPK4 and CPK11, regulate abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 3019–3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.