Abstract

Drosophila melanogaster is one of the most well studied genetic model organisms, nonetheless its genome still contains unannotated coding and non-coding genes, transcripts, exons, and RNA editing sites. Full discovery and annotation are prerequisites for understanding how the regulation of transcription, splicing, and RNA editing directs development of this complex organism. We used RNA-Seq, tiling microarrays, and cDNA sequencing to explore the transcriptome in 30 distinct developmental stages. We identified 111,195 new elements, including thousands of genes, coding and non-coding transcripts, exons, splicing and editing events and inferred protein isoforms that previously eluded discovery using established experimental, prediction and conservation-based approaches. Together, these data substantially expand the number of known transcribed elements in the Drosophila genome and provide a high-resolution view of transcriptome dynamics throughout development.

INTRODUCTION

Drosophila melanogaster is an important non-mammalian model system that has played a critical role in basic biological discoveries, such as identifying chromosomes as the carriers of genetic information1 and uncovering the role of genes in development2,3. Because it shares a substantial genic content with humans4, Drosophila is increasingly used as a translational model for human development, homeostasis, and disease5.

High quality maps are needed for all functional genomic elements. Previous studies demonstrated that a rich collection of genes is deployed during the life cycle of the fly6-8. While expression profiling using microarrays has revealed the expression of ~13K annotated genes, it is difficult to map splice junctions and individual base modifications generated by RNA editing9 using such approaches. Single-base-resolution is essential to precisely define the elements that comprise the Drosophila transcriptome.

Estimates of the number of transcript isoforms are less accurate than estimates of the number of genes. While ~20% of Drosophila genes are annotated as encoding alternatively spliced pre-mRNAs, splice-junction microarray experiments suggest that this number is at least 40%7. Determining the diversity of mRNAs generated by alternative promoters, alternative splicing and RNA editing will substantially increase the inferred protein repertoire. Non-coding RNA genes (ncRNAs) including siRNAs and miRNAs (reviewed in 10), and longer ncRNAs such as bxd11 and rox12 play important roles in gene regulation, while others such as snoRNAs and snRNAs are important components of macromolecular machines such as the ribosome and spliceosome. The transcription and processing of these ncRNAs must also be fully documented and mapped.

As part of the modENCODE project to annotate the functional elements of the D. melanogaster and C. elegans genomes13-15, we used RNA-Seq and tiling microarrays to sample the Drosophila transcriptome at unprecedented depth throughout development from early embryo to aging, male and female adults. We report on a high-resolution view of the discovery, structure and dynamic expression of the D. melanogaster transcriptome.

RESULTS

Strategy for Characterization of the Transcriptome

To discover new transcribed features (Supplementary Table 1) and comprehensively characterize their expression dynamics throughout development, we conducted complementary tiling microarray and RNA-Seq experiments using RNA isolated from 30 whole-animal samples representing 27 distinct stages of development (Supplementary Table 2). These included 12 embryonic samples collected at two-hour intervals for 24 hours, six larval, six pupal, and three sexed adult stages at 1, 5, and 30 days post-eclosion. We used 38 bp resolution genome tiling microarrays to analyze total RNA from all 30 biological samples and poly(A)+ mRNA from the 12 embryonic samples (Supplementary Fig. 1). To attain single nucleotide resolution and to facilitate the analysis of alternative splicing and RNA editing, we performed non-strand specific poly(A)+ RNA-seq from all 30 samples generating a combination of single and paired-end ~75 bp reads on the Illumina GAIIx platform (short poly (A)+ RNA-Seq) (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 2). To identify primary transcripts and non-coding RNAs, the 12 embryonic time points were also interrogated with strand-specific 50 bp sequence reads from partially rRNA-depleted total RNA on the Applied Biosystems SOLiD platform (Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Fig. 3). To improve connectivity, mixed-stage embryos, adult males and adult females were used to generate ~250 bp reads on the Roche 454 platform (non-strand specific long poly(A)+ RNA-Seq) (Supplementary Table 5). In total, we generated 176,962,906,041 bp of mapped sequence representing 1,266-fold coverage of the genome and 5,902-fold coverage of the annotated D. melanogaster transcriptome.

Discovery of New Transcribed Regions

We identified 1,938 New Transcribed Regions (NTRs) not linked to any annotated gene models. Herein, “transcripts” refer to RNA molecules synthesized from a genomic locus while “genes” refer to one or more transcripts that share exons in their mature spliced form. modENCODE cDNAs fully support 13% of the NTRs (Supplementary Fig. 4) and partially support 23%. Most NTRs (84%) are detected by poly(A)+ RNA-seq, 44% by total RNA-Seq, and 42% by tiling array. Approximately half of the NTRs are conserved in the distantly related D. pseudoobscura and D. mojavensis (Supplementary Fig. 4b) and 30% of these are detected by poly(A)+ RNA-Seq data from D. pseudoobscura or D. mojavensis adult heads (Supplementary Fig. 4c,d, Supplementary Table 6). The NTRs most likely eluded prior detection because they are expressed at low levels, in temporally restricted patterns, and are enriched for single exon genes. The new multi-exon gene models (48%) have fewer, shorter, and less conserved exons than annotated genes.

Nearly one-third of the NTRs have a predicted ORF greater than 100 aa. The remaining NTRs could encode small peptides but many are likely to be non-coding RNAs. A small fraction (9%) of NTRs are heterochromatic, the majority of these (232) have sequence similarity (greater than 100 nt match and greater than 60% identity) to transposable elements (TEs) and represent transcribed TEs or TE fragments. It remains to be determined if these regions have any function, although recent studies describe TE associated regions that have acquired functions16,17.

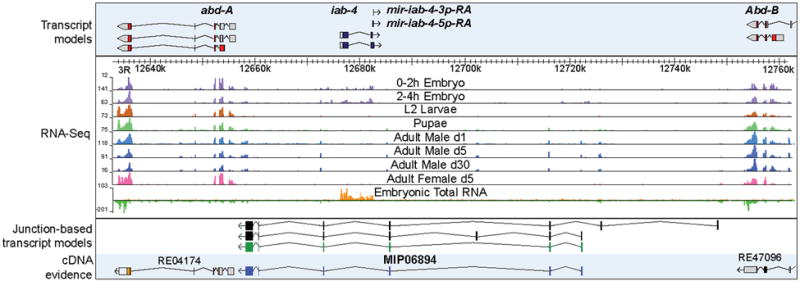

Even in the well-studied bithorax complex2, we found an NTR. Known genetic breakpoints in the infra-abdominal regions iab-3 to iab-8, which lie between the homeotic genes abdominal-A (abd-A) and Abdominal-B (Abd-B), disrupt normal male development and affect fertility18,19. Within this region are regulatory elements20 and evidence for long non-coding RNAs that have eluded detection for over 20 years21-23. We used the RNA-seq data to infer the structures of at least three overlapping transcripts and validated one form (Fig. 1). The RNAs are expressed in embryos and adult males but not females. Based on the presumed role of this new gene and spatial expression in the embryonic gonad (data not shown), we have named it male specific abdominal (msa). The cDNA contains short open reading frames (ORFs) that are conserved in the melanogaster subgroup and could encode male specific peptides. Whether they function as regulatory and/or as peptide encoding RNAs is an important question for understanding development and segmental morphological diversity.

Figure 1. Discovery of new RNAs in the bithorax complex.

Genomic organization and experimental evidence for new transcripts located between the HOX genes, abd-A and Abd-B based on short poly(A)+ RNA and total RNA-seq expression profiles. The numbers to the left of each track indicate the maximal number of reads for that sample. Three manually curated junction-based transcript models are shown, the green transcript model was fully validated by a cDNA, MIP06894.

Discovery of small non-coding RNAs

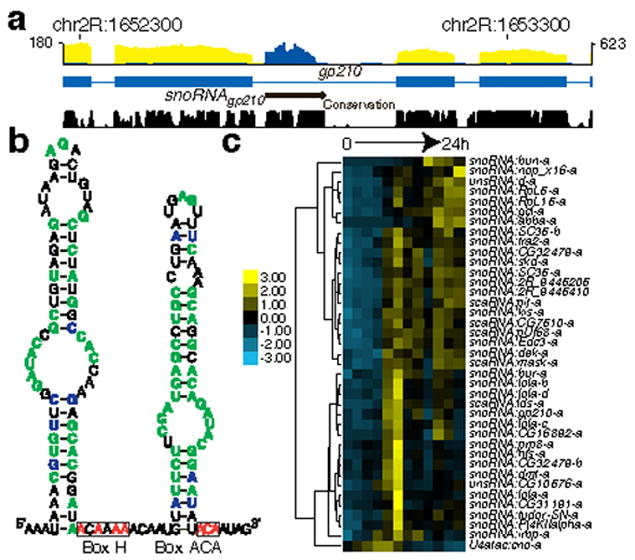

We identified 37 unannotated intron-encoded and two unannotated intergenic small ncRNAs (<300 nt) with an average fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM)24 >20 from total embryonic RNA-Seq (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 7). Most of these ncRNAs are highly conserved in Drosophila sibling species25. We found published but unannotated ncRNAs: a U4atac snRNA26 and four small Cajal body-specific RNAs (scaRNAs)27. Of the remaining 34 ncRNAs, three are box C/D-like snoRNAs, 28 are box H/ACA-like snRNAs, one is a scaRNA-like RNA, and two are unclassified. One-third are located in the introns of genes encoding RNA binding proteins, the majority involved in pre-mRNA splicing (xl6, SC35, tra2, dek, prp8, tudor-SN, and pUf68).

Figure 2. Discovery of small non-coding RNAs.

a. Poly(A)+ (yellow) and total RNA (blue) data from 10-12 h embryos are shown for the gp210 gene which hosts a representative new snoRNA. The maximal number of reads in the poly(A)+ and total RNA-Seq data are shown on the left and right of the track, respectively. b. The predicted RNA secondary structure of snoRNAgp210 is characteristic of a H/ACA-box snoRNA. Nucleotides that are 100% conserved in sequence or base-pairing are indicated in green and blue, respectively. c. Embryonic expression of the new small RNAs. The scale bar indicates FPKM Z-scores.

Discovery of microRNA primary transcripts

MicroRNAs are processed from primary microRNA transcripts (pri-miRNAs) and are either independently transcribed or embedded in the introns of protein-coding genes. We identified 23 putative independently transcribed pri-miRNAs from the total embryonic RNA-Seq and tiling array data that encode 37 annotated miRNAs (Supplementary Table 8). Only two primary transcripts were previously annotated (bft and iab-4). The pri-miRNAs range from 1 to 18 kb and terminate at the mature miRNA (pre-mir-315, Supplementary Fig. 5a). Twelve of the 23 precursors have Cap Analysis of Gene Expression (CAGE) peaks that map at their initiation sites28. pri-miRNA expression is dynamic in embryonic development (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Overview of the Drosophila Transcriptome

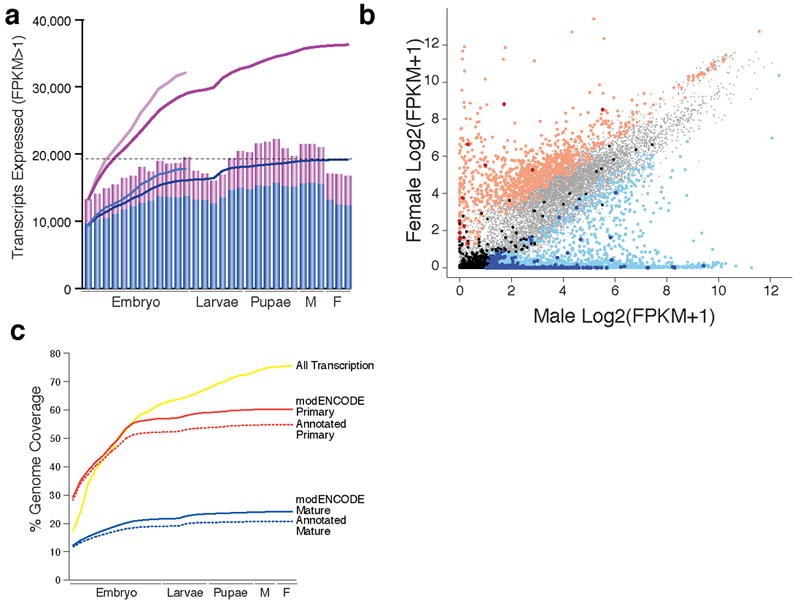

We calculated expression levels of annotated genes, transcripts, and NTRs (Supplementary Table 9) in the short poly(A)+ RNA-Seq and tiling array datasets. From the RNA-Seq data we detected expression of 14,862 genes (Supplementary Fig. 7a) and 36,274 transcripts (Fig. 3a) with an FPKM>1 (Supplementary Tables 9-18) of which 67% of genes and 58% of transcripts were also observed in the array data (score >300) (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Tables 19 & 20). This includes the confirmation of 87% of annotated genes and transcripts and the discovery of 17,745 new transcripts. In addition, from the total RNA-Seq data we detected expression of 12,854 genes and 32,139 transcripts with an FPKM>1 (Supplementary Tables 12,13,21 & 22) of which 77% of genes and 89% of transcripts were also observed in the array data. Of the genes and transcripts observed exclusively in the total RNA-Seq data, 519 genes and 1,005 transcripts (primarily noncoding) were previously annotated and 122 genes and 1,422 transcripts are new discoveries. The genes and transcripts not detected in any dataset include small genes (< 200 bp), members of multi-copy gene families such as ribosomal RNAs, paralogs (expected due to our mapping parameters), genes known to be expressed at low levels or in small numbers of cells (e.g. gustatory and odorant receptor genes), and non-polyadenylated transcripts.

Figure 3. Dynamics of Gene Expression.

a. Transcripts expressed (FPKM>1) in the short poly(A)+ RNA-Seq data, FB5.12 (blue), modENCODE (purple). The bar graphs indicate the number of transcripts expressed in each sample (Supplementary Table 1), and the lines, the cumulative number of expressed transcripts. The lighter blue and purple lines indicate the cumulative number of transcripts expressed in the embryonic Total RNA-Seq samples. The horizontal dotted lines indicate the number of expressed previously annotated transcripts. b. Scatter plot of sex-biased gene expression. light red: female-biased annotated (n=960), dark red: female-biased NTRs (n=12), light blue: male-biased annotated (n=2,401), dark blue: male-biased NTRs (n=431), light grey: unbiased annotated (n=8,217), black: unbiased NTRs (n=136). c. Genome Coverage. For each developmental sample, the short poly(A)+ reads were used to estimate the percent of the genome covered using a cutoff of two reads. The mature and primary transcripts were inferred for the previously FB5.12 (dotted lines) and modENCODE (solid lines) gene models.

Expression Dynamics

We examined the dynamics of gene expression throughout development using the short poly(A)+ RNA-Seq data. The numbers of expressed genes (FPKM >1) (Supplementary Fig. 7a) and transcripts (Fig. 3a) gradually increases, from 7,045 (0-2 hr embryos) to 12,000 (adult males). Adult males express ~3,000 more genes than adult females, consistent with the known transcriptional complexity of the testis29. We observed that 40% of expressed genes are constitutively expressed in 30 samples (Supplementary Fig. 7b). We also observed developmentally regulated expression of transposable elements (Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Fig. 8).

We observed pronounced expression changes in over 1,500 genes in the first two third instar larval samples (Supplementary Fig. 7a,c). Expression of 1,199 genes increased at least 10-fold, and 421 genes decreased at least 10-fold (Supplemental Table 23). Nearly all of the up-regulated genes are expressed for the first time during the third instar stage and most are poorly characterized genes.

The earliest known event in metamorphosis is the “mid-3rd transition”30,. identified by the synchronous changes in the transcription of a number of well-studied genes, Ecdysone-induced protein 28/29kD and fat body protein 1 (reviewed in31) and the switch from proximal to distal promoters of Alcohol dehydrogenase32. These markers coincide with the surge reported here. The mid-3rd transition has no morphological or behavioral correlates and is associated with a pulse of the steroid hormone, ecdysone33 acting through a non-standard receptor34. Whether the onset of testis development is a consequence of the mid-3rd transition, or whether the two events are functionally related remains to be investigated.

Over 29% of protein-coding genes showed significant sex-biased expression in adults (FDR<0.1%), with more male-biased (1,829) or male-specific genes (572) than female-biased (945) or female-specific genes (15) (Supplementary Tables 24 & 25) and Fig. 3b). Known female (ovo and otu) and male (dj) sex-biased genes were expressed as expected. We found that 74% of the NTRs expressed in adults were significantly male-biased whereas only 2.1% were significantly female-biased.

Genome Coverage

Mature mRNAs are encoded by 20% of the D. melanogaster genome and primary transcripts by 60% (Fig. 3c). An additional 15% of the genome (~75% total) is detected when considering all of the short poly(A)+ RNA-Seq data. However, as greater than 99% of the reads map within the bounds of the transcript models, the reads that map to intergenic regions constitute a small minority of our data. Thus, though pervasive transcription of mammalian genomes has been observed in microarray studies35, we found little evidence of such “dark matter”36.

Discovery and dynamics of alternative splicing

To characterize constitutive and alternative splicing, we identified 71,316 splice junctions, of which 22,965 were new discoveries. Of the new splice junctions, 26% were supported by multiple experimental data types and 74% by only one data type, (Supplementary Fig. 9a) primarily short poly(A)+ RNA-Seq. Of the 20,751 new junctions from the short poly(A)+ RNA-Seq data, 7,833 were incorporated into new transcript models or transcribed regions (NTRs). The remaining new junctions have yet to be incorporated into transcript models.

We also identified a total of 102,026 exons (Supplementary Table 26). Of the 52,914 representing new and revised exons, 65% were validated by capture and sequencing of cDNAs and 2,586 were supported by RNA-Seq data from D. mojavensis and D. pseudoobscura. Of the new exons, 3,392 were identified from the new splice junctions but have yet to be incorporated into transcript models.

To examine splicing dynamics throughout development, we categorized all splicing events into the common types of alternative splicing events (Table 1). We identified a total of 23,859 splicing events, of which 18,490 were new or recategorized, a three-fold increase from annotated splicing events. An additional 2,988 intron-retention events were identified from the short poly(A)+ RNA-seq data, and are yet to be supported by other experimental data. In all, 7,473 genes contain at least one alternative splicing event, 60.7% of the 12,295 expressed multi-exon genes – also a three-fold increase in the fraction of genes with alternatively spliced transcripts. While smaller than the fraction of human genes with alternatively spliced transcripts (95%)37,38, a larger proportion of Drosophila genes encode alternative transcripts than was previously known.

Table 1.

Classification of Alternative Splicing Events

| FlyBase r5.12 |

modENCODE |

New Events |

Short Poly(A)+ RNA-Seq |

Significantly Changing |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cassette Exons | 793 | 2,717 | 2,014 | 2,369 | 1,539 | |

| Alternative 5’ Splice Sites | 843 | 5,192 | 4,599 | 4,583 | 3,142 | |

| Alternative 3’ Splice Sites | 879 | 6,253 | 5,505 | 5,579 | 3,242 | |

| Mutually Exclusive Exons | 229 | 251 | 123 | 228 | 226 | |

| Coordinate Cassette Exons | 301 | 1,227 | 979 | 992 | 467 | |

| Alternative First Exons | 1,767 | 4,936 | 3,442 | 4,473 | 3,996 | |

| Alternative Last Exons | 227 | 604 | 553 | 553 | 471 | |

| Retained/Unprocessed Introns | 1,434 | 2,679 (5,667) | 1,275 (4,263) | 2,439 (35,641) | 868 (8,998) | |

| 6,473 | 23,859 (26,847) | 18,490 (21,478) | 21,216 (54,418) | 13,951 (22,081) | ||

The number of retained/unprocessed introns indicated in parentheses indicates the total number identified, while the number not in parentheses indicates the subset of identified events that have been validated by cDNA sequences or FlyBase 5.12 annotations.

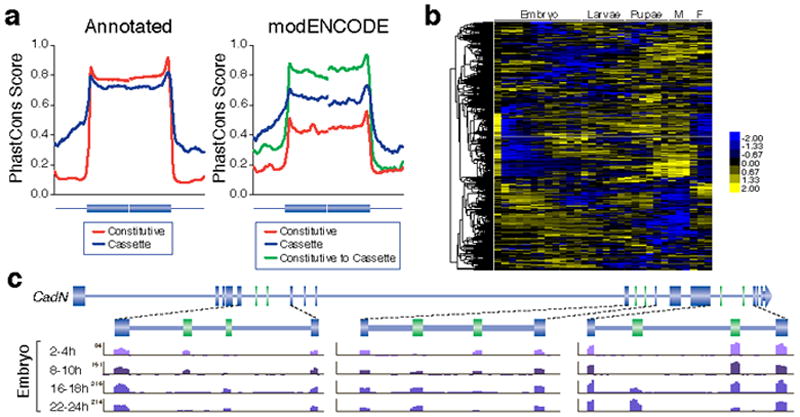

Of the new alternative exons, 8,226 were previously annotated as constitutive. As observed39, annotated cassette exons, and their flanking introns are more highly conserved than annotated constitutive exons (Fig. 4a). The newly discovered cassette exons are more highly conserved than the new constitutive exons, though both classes are less conserved than the corresponding class of annotated exons. New cassette exons that were previously annotated as constitutive exons are the most highly conserved set of exons (Fig. 4a). Annotated and new cassette exons show a strong tendency to preserve reading-frame (Supplementary Fig. 9b) suggesting that these transcripts increase protein diversity. Both annotated and new cassette exons tend to be shorter than their constitutive counterparts, though both sets of new exons tend to be shorter than annotated exons.

Figure 4. Developmentally regulated splicing events.

a. Conservation of internal constitutive and cassette exons >50 nt that were annotated or new discoveries. (Annotated Constitutive, n=26,127; Annotated Cassette, n=438; modENCODE Cassette n=173; modENCODE Constitutive n=306; 5.12 Constitutive to modENCODE Cassette n=304). b. Clusters of regulated cassette exon events during development. The scale bar indicates Z-scores of Ψ. c. Regulated alternative splicing in CadN during embryogenesis. The maximal number of reads in the poly(A)+ RNA-Seq data are indicated for each track

To assess the extent of splicing variation we calculated the “percent spliced in” or Ψ38 for each splicing event in each sample as well as the switch score (ΔΨ) by determining the difference between the highest and lowest Ψ values across development (ΔΨ = ΨMAX - ΨMIN). This revealed a very smooth distribution of ΔΨ among all events indicating that the splicing of most exons is fairly constant while only a minority change dramatically (Supplementary Fig. 9c, Supplemental Table (was old 31 now is Table 27). Only 831 splicing events have a ΔΨ value >90. Further statistical analyses (see Methods) identified 15,847 (67%) alternative splicing events that change significantly throughout development (Supplemental Table (was old 32 now is Table 28).

Hierarchical clustering of cassette exon events revealed the dynamic nature of splicing throughout development (Fig. 4b) as exemplified by Cadherin-N (CadN), a gene with three sets of mutually exclusive exons (Fig. 4c). In each set, one exon is preferentially included in early embryos, the other in late embryos, with a smooth transition between the two. Our analysis also identified groups of exons that have coordinated splicing patterns (Fig. 4b). A set of 55 genes contains exons that are preferentially included in early embryos, late larvae, early pupae, and females but skipped in all other stages. GO analysis of these genes suggests that many encode proteins involved in epithelial cell-to-cell junctions. GO analysis of genes that contain exons preferentially included during late pupal and adult stages, suggests that many encode proteins that are part of neuronal synapses.

Sex-biased alternative splicing

Sex determination in Drosophila is mediated by a cascade of regulated alternative splicing events involving Sex lethal (Sxl), transformer (tra), male-specific lethal 2 (msl-2), doublesex (dsx), and fruitless (fru) that specify nearly all physical and behavioral dimorphisms between males and females as well as X chromosome dosage compensation40. Our RNA-Seq data confirm sex-biased splicing of Sxl (ΔΨ=89.6), tra (ΔΨ=39.2), dsx (ΔΨ=59.7), and fru (ΔΨ=100).

In addition to the canonical sex-determination cascade, we identified 119 strongly sex-biased splicing events (ΔΨ>70) (Supplementary Fig. 9d). One striking example is Reps which was annotated as containing six constitutive exons. RNA-Seq data indicate that exon five is a sex-biased alternative cassette exon (ΔΨ=73.39) (Supplementary Fig. 10). This highly conserved exon is included in males and skipped in females. The intron upstream of this cassette exon contains conserved SXL binding sites suggesting it is regulated by SXL and is a candidate sex differentiation gene.

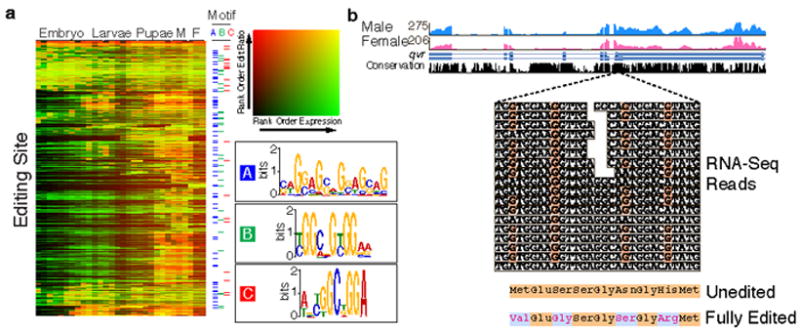

Discovery of RNA editing sites

Previous studies identified 127 sites in 55 Drosophila genes that undergo A-to-I RNA editing41. This post-transcriptional modification is catalyzed by dADAR, which is expressed at increasing levels throughout development and is thought to target products involved in nervous system function. We analyzed the poly(A)+ RNA-Seq data to identify exonic nucleotide positions consistent with A-to-I editing and defined 972 edited positions within transcripts of 597 genes, including previously described edited sites in the transcripts of 36 genes (Supplementary Table 29). These genes include those required for rapid neurotransmission and other widely ranging functions. For most sites, the frequency of editing increases throughout development and does not correlate with overall expression levels (Fig. 5a). Editing typically begins in late pupal stages, although we find transcripts that appear to be edited in late embryogenesis. Consistent with earlier studies42, exons containing editing sites are more highly conserved than unedited exons. The majority of the edited positions (630) alter amino acid coding, the others are either silent (201) or within UTRs (141). For example, the transcripts of quiver (qvr) are edited at six positions, four that result in amino acid changes (Fig. 5b). qvr encodes a potassium channel subunit that modulates the function of the voltage-gated Shaker (SH) potassium channel. Sh transcripts are also edited at multiple positions43. The combinatorial editing of both proteins likely plays an important role in modulating action potentials in the arthropod nervous system and may have implications for the regulation of sleep44. ESTs, long poly(A)+ RNA-seq and cDNAs cross validate nearly a quarter (214) of the newly discovered sites.

Figure 5. Discovery of RNA editing events.

a. Rows represent an edited sites. Rank ordered expression levels (number of reads) are shown in green and the rank ordered editing ratios are shown in red. Pictogram representations of editing motifs A, B, and C are shown. b. RNA editing of qvr. Male and female expression and conservation tracks are shown above RNA-Seq reads from adult females that align to the edited positions (orange). Conceptual translation of the unedited and fully transcripts result in four amino acid changes (red) at the C-terminus of QVR.

Computational analysis identified three potential editing associated sequence motifs (Fig. 5a). We observe 381 sites with one or more motifs in close proximity to the edited nucleotide (Supplementary Table 30). Motif ‘C’, while less common than motifs ‘A’ and ‘B’, is more strongly associated with the editing site. Most (93%) instances of motif ‘C’ occur on the sense strand of the transcript and the A at the 3’ end of the motif is the edited nucleotide. This motif is overrepresented in editing events that occur early in development.

DISCUSSION

Our interrogation of the transcriptome of D. melanogaster throughout development has considerably expanded the number of building blocks used to make a fly. Specifically, we identified nearly 2,000 NTRs, increased the number of alternative splicing events by three-fold and the number of RNA editing sites by an order of magnitude. The resulting view of the transcriptome at single-base resolution dramatically improves our understanding of expression dynamics throughout the Drosophila life cycle and has substantial biological implications.

The D. melanogaster, C. elegans and human genomes are organized quite differently. Specifically, 20%, 45% and 2.5% of the D. melanogaster, C. elegans and human genomes, respectively, encode exons or mature transcripts. Primary transcripts comprise a larger fraction of each genome – 60%, 82% and 37%. This highlights the facts that primary transcripts and introns are much shorter in D. melanogaster and C. elegans than in human and that the D. melanogaster and C. elegans genomes are more compact than the human genome.

The existence of unannotated genes was suggested by microarray studies8,45 and conservation among Drosophilid genomes25. However, the NTRs we identified were not identified by comparative sequence analysis46 as they are less conserved than most previously known genes. This emphasizes the importance of using both comparative analyses and transcriptome profiling for genome annotation.

Despite the depth of our sequencing, the annotation of the D. melanogaster transcriptome is not finished. We failed to detect expression of 1,488 annotated genes including members of gene families to which short reads can not be uniquely mapped and genes expressed at low levels or in spatially and temporally restricted patterns. Moreover, though we substantially increased the fraction of genes that encode alternatively spliced or edited transcripts, we again failed to detect several annotated RNA processing events. Study of more temporally and spatially restricted samples will allow deeper exploration of the Drosophila transcriptome, and almost certainly result in the discovery of yet additional features. Furthermore, functional studies of the new and previously unstudied elements, will provide valuable insight into metazoan development.

METHODS SUMMARY

Animal Staging, Collection and RNA extraction

Isogenic (y1; cn bw1 sp1) embryos were collected at two-hour intervals for 24 hours. Collection of later staged animals started with synchronized embryos and included resynchronizing with appropriate age indicators. Six larval, six pupal, and three adult sexed stages, 1, 5 and 30 days were collected. RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen), DNased, and purified on a RNAeasy column (Qiagen). poly(A)+ RNA was prepared from an aliquot of each total RNA sample using an Oligotex kit (Qiagen).

Tiling Arrays

RNAs from three biological replicates of each sample were independently hybridized on 38-bp arrays (Affymetrix GeneChip® Drosophila Tiling 2.0R Array) as described47.

RNA-Seq

Libraries were generated and sequenced on an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx using single or paired-end chemistry and 76 bp cycles. SOLiD sequencing used total RNA treated with the RiboMinusTM Eukaryote Kit (Invitrogen). Samples were fragmented, adaptors ligated (Ambion) and sequenced for 50 bases using SOLiD V3 chemistry. 454 sequencing used poly(A)+ RNA from Oregon R adult males and females and mixed-staged y1; cn bw1 sp1 embryos. Sequences are available from the Short Read Archive and the modENCODE website (http://www.modencode.org/).

Targeted RT-PCR and cDNA Isolation and Sequencing

Standard procedures were used for RT-PCR and targeted cDNA isolation and sequencing.

Analysis

Cufflinks24 was used to identify new transcript models and to calculate expression levels for annotated and predicted transcript models. MFold48 was used to predict secondary structures from the new snoRNA-like RNAs. JuncBASE 49 identified alternative splicing events and calculated percent spliced in (Ψ)38. Editing sites were identified by comparing aligned reads to the reference genome.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cole Trapnell and Lior Pachter for discussions and assistance with Cufflinks, and Emily Clough for comments and feedback. This work was funded by a contract from the National Human Genome Research Institute modENCODE Project, contract U01 HG004271, to S.E.C. under Department of Energy contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231, and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Intramural Research Program (B.O.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.A., M.R.B., P.C., T.R.G., B.R.G., R.A.H., T.C.K., B.O., N.P., and S.E.C. designed the project. J.A., S.E.B., M.R.B., P.C., T.R.G., B.R.G., R.A.H., B.O., and S.E.C. managed the project. D.M. prepared biological samples. T.C.K. oversaw biological sample production. D.Z. and B.E. prepared RNA samples. J.A. oversaw RNA sample production. W.L. and A.W. analyzed array data. P.K. managed array data production. L.Y. prepared Illumina RNA-Seq libraries. C.A.D., L.L., J.E.S., K.H.W., and L.Y. performed Illumina sequencing. J.M.L., B.R.G., and S.E.C. managed Illumina sequencing production. M.B. and R.E.G. performed 454 sequencing of adults. R.A.H. managed production of the embryonic SOLiD and 454 sequencing. C.A.D. managed data transfers. C.Z. managed databases and formatted array and sequence data for submission. P.J.B., A.N.B., S.D., M.O.D. and D.S. developed analysis methods. J.B.B., N.B., B.W.B., A.N.B., J.W.C., S.E.C., L.C., P.C., C.A.D., A.D., M.O.D., B.R.G., R.L., N.R.M., Yi.Z. analyzed data. B.B.T. aligned the SOLiD data. M.J.V. and J.M.L. generated annotations. C.G.A., D.S., and J.H.M. analyzed species validation data. L.J., C.G.A., D.S., and N.R.M. performed species RNA-Seq QC. Yu.Z. and J.H.M. oversaw sequencing and gathered species samples. C.G.A., A.N.B., J.W.C., L.C., P.C., A.H., D.S., J.M.L., R.L. N.R.M., J.H.M., and B.O. contributed to the text. A.H. assisted with manuscript preparation. B.R.G. and S.E.C. wrote the paper with input from all authors. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature. All sequence data has been deposited in the SRA (SRA009364), cDNA sequences have been deposited in GenBank, and array data deposited in GEO. All data is also available at www.modencode.org.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Morgan TH. Sex Limited Inheritance in Drosophila. Science. 1910;32:120–122. doi: 10.1126/science.32.812.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis EB. A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature. 1978;276:565–570. doi: 10.1038/276565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nusslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature. 1980;287:795–801. doi: 10.1038/287795a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin GM, et al. Comparative Genomics of the Eukaryotes. Science. 2000;287:2204–2215. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spradling AC. Learning the common language of genetics. Genetics. 2006;174:1–3. doi: 10.1093/genetics/174.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbeitman MN, et al. Gene expression during the life cycle of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2002;297:2270–2275. doi: 10.1126/science.1072152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stolc V, et al. A gene expression map for the euchromatic genome of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2004;306:655–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1101312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manak JR, et al. Biological function of unannotated transcription during the early development of Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1151–1158. doi: 10.1038/ng1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bass BL. RNA editing. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rana TM. Illuminating the silence: understanding the structure and function of small RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipshitz HD, Peattie DA, Hogness DS. Novel transcripts from the Ultrabithorax domain of the Bithorax Complex. Genes and Development. 1987;1:307–322. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meller VH, Wu KH, Roman G, Kuroda MI, Davis RL. roX1 RNA paints the X chromosome of male Drosophila and is regulated by the dosage compensation system. Cell. 1997;88:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celniker SE, et al. Unlocking the secrets of the genome. Nature. 2009;459:927–930. doi: 10.1038/459927a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kellis M, et al. Science. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerstein MB, et al. Science. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bejerano G, et al. A distal enhancer and an ultraconserved exon are derived from a novel retroposon. Nature. 2006;441:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nature04696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie X, Kamal M, Lander ES. A family of conserved noncoding elements derived from an ancient transposable element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11659–11664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604768103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karch F, et al. The abdominal region of the Bithorax Complex. Cell. 1985;43:81–96. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celniker SE, Sharma S, Keelan D, Lewis EB. The molecular genetics of the bithorax complex of Drosophila cis-regulation in the Abdominal-B domain. European Molecular Biology Organization Journal. 1990;9:4277–4286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho MC, et al. Functional evolution of cis-regulatory modules at a homeotic gene in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Herrero E, Akam M. Spatially ordered transcription of regulatory DNA in the bithorax complex of Drosophila. Development. 1989;107:321–329. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae E, Calhoun VC, Levine M, Lewis EB, Drewell RA. Characterization of the intergenic RNA profile at abdominal-A and Abdominal-B in the Drosophila bithorax complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99 doi: 10.1073/pnas.222671299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender W. MicroRNAs in the Drosophila bithorax complex. Genes Dev. 2008;22:14–19. doi: 10.1101/gad.1614208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark AG, et al. Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007;450:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nature06341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padgett RA, Shukla GC. A revised model for U4atac/U6atac snRNA base pairing. RNA. 2002;8:125–128. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202017156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tycowski KT, Shu MD, Kukoyi A, Steitz JA. A conserved WD40 protein binds the Cajal body localization signal of scaRNP particles. Mol Cell. 2009;34:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoskins RA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of promoter architecture in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 2010 doi: 10.1101/gr.112466.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parisi M, et al. A survey of ovary-, testis-, and soma-biased gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster adults. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R40. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-6-r40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andres AJ, Cherbas P. Tissue-specific ecdysone responses: regulation of the Drosophila genes Eip28/29 and Eip40 during larval development. Development. 1992;116:865–876. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andres AJ, Fletcher JC, Karim FD, Thummel CS. Molecular analysis of the initiation of insect metamorphosis: a comparative study of Drosophila ecdysteroid-regulated transcription. Dev Biol. 1993;160:388–404. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockett TJ, Ashburner M. Temporal and spatial utilization of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene promoters during the development of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1989;134:430–437. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warren JT, et al. Discrete pulses of molting hormone, 20-hydroxyecdysone, during late larval development of Drosophila melanogaster: correlations with changes in gene activity. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:315–326. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costantino BF, et al. A novel ecdysone receptor mediates steroid-regulated developmental events during the mid-third instar of Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birney E, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Bakel H, Nislow C, Blencowe BJ, Hughes TR. Most “dark matter” transcripts are associated with known genes. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1413–1415. doi: 10.1038/ng.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang ET, et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philipps DL, Park JW, Graveley BR. A computational and experimental approach toward a priori identification of alternatively spliced exons. RNA. 2004;10:1838–1844. doi: 10.1261/rna.7136104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez L. Sex-determining mechanisms in insects. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:837–856. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072396ls. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stapleton M, Carlson JW, Celniker SE. RNA editing in Drosophila melanogaster: New targets and functional consequences. RNA. 2006;12:1922–1932. doi: 10.1261/rna.254306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jepson JE, Reenan RA. Genetic approaches to studying adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing. Methods Enzymol. 2007;424:265–287. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)24012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoopengardner B, Bhalla T, Staber C, Reenan R. Nervous system targets of RNA editing identified by comparative genomics. Science. 2003;301:832–836. doi: 10.1126/science.1086763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang JW, Wu CF. Modulation of the frequency response of Shaker potassium channels by the quiver peptide suggesting a novel extracellular interaction mechanism. J Neurogenet. 2010;24:67–74. doi: 10.3109/01677061003746341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hild M, et al. An integrated gene annotation and transcriptional profiling approach towards the full gene content of the Drosophila genome. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stark A, et al. Discovery of functional elements in 12 Drosophila genomes using evolutionary signatures. Nature. 2007;450:219–232. doi: 10.1038/nature06340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cherbas L. The Transcriptional Diversity of 25 Drosophila Cell Lines. Genome Res. 2010 doi: 10.1101/gr.112961.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brooks AN, et al. Conservation of an RNA Regulatory Map between Drosophila and Mammals. Genome Research. 2010 doi: 10.1101/gr.108662.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.