Abstract

In the respiratory chain free energy is conserved by linking the chemical reduction of dioxygen to the electrogenic translocation of protons across a membrane. Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) is one of the sites where this linkage occurs. Although intensively studied, the molecular mechanism of proton pumping by this enzyme remains unknown. Here, we present data from an investigation of a mutant CcO from Rhodobacter sphaeroides [Asn-139 → Asp, ND(I-139)] in which proton pumping is completely uncoupled from the catalytic turnover (i.e., reduction of O2). However, in this mutant CcO, the rate by which O2 is reduced to H2O is even slightly higher than that of the wild-type CcO. The data indicate that the disabling of the proton pump is a result of a perturbation of E(I-286), which is located 20 Å from N(I-139) and is an internal proton donor to the catalytic site, located in the membrane-spanning part of CcO. The mutation results in raising the effective pKa of E(I-286) by 1.6 pH units. An explanation of how the mutation uncouples catalytic turnover from proton pumping is offered, which suggests a mechanism by which CcO pumps protons.

Heme–copper respiratory oxidases are integral membrane–protein complexes, which are the last components of the respiratory chains in aerobic organisms where they catalyze the reduction of molecular oxygen to water (O2 + 4e– + 4H+ → 2 H2O). Most members of this family of enzymes are redox-driven proton pumps, i.e., the O2-reduction reaction is energetically coupled to proton translocation across the membrane. One member of the family is cytochrome c oxidase (CcO), which uses a water-soluble or membrane-anchored cytochrome c as an electron donor. In CcO (cytochrome aa3) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, electrons from cytochrome c are first transferred to a copper center, CuA, located on the electrically positive (P) side of the membrane, and are then transferred via heme a to a heme-copper center (heme a3 and CuB binuclear center), which is the catalytic site of the CcOs. Dioxygen binds to reduced heme a3, which is followed by stepwise reduction, requiring four electrons and four protons (for review, see refs. 1–3). These four protons are taken up from the negative (N) side of the membrane. The considerable free energy available from this process is coupled to driving the electrogenic pumping of four additional protons from the N side to the P side, across the membrane. The sequence of events associated with the proton translocation, triggered by the chemical reaction (i.e., O2 reduction) at the catalytic site, is likely to shift the pKa of at least one protonatable group within CcO for which there is a kinetic preference to take a proton from a donor on the N side of the membrane when its pKa is raised and to donate the proton to an acceptor on the P side of the membrane when its pKa is lowered.

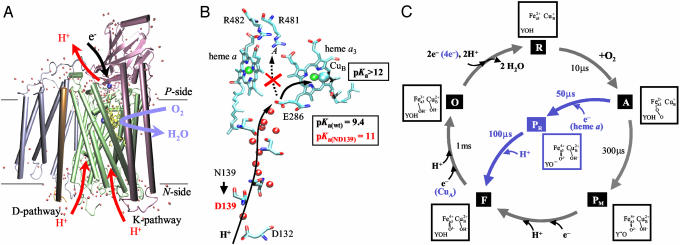

Two proton-conducting pathways (the D and the K pathway) have been identified leading from the N-side surface of CcO to the binuclear center (Fig. 1A, for structural information, see refs. 4–7). The K pathway was shown to be used for uptake of one to two protons during reduction of the binuclear center, and it is not used for proton uptake during the following oxidation of CcOby O2 (9–15). Previous studies of mutant forms of CcO have shown that the D pathway is used for the uptake of both substrate protons (protons used during reduction of O2 to H2O) and “pumped protons” (10, 16). Hence, there must be a branch point within the D pathway from which protons are transferred either to the binuclear center (substrate protons) or to a protonatable group in the output pathway (pumped protons). The results from the current as well as previous work (17–27) indicate that the pathway branches at Glu-286 [E(I-286)] (see Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A) The structure of CcO from R. sphaeroides (1m56 in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org/pdb; ref. 7). (B) The redox-active groups (except CuA) and the D proton-transfer pathway in the R. sphaeroides CcO. The red spheres are water molecules in the D pathway. The location of residues discussed in this work is indicated. The D pathway is used for the transfer of both substrate and pumped protons (see arrows). At E(I-286), there is a possible branching point from which substrate protons are transferred to the binuclear center and pumped protons are transferred to an acceptor (dashed arrow) in contact with the proton output side. In the wild-type and ND(I-139) mutant CcO, the apparent pKa values of E(I-286) are 9.4 and ≈11, respectively. The pKa of the acceptor at the binuclear center is suggested to be ≥12 (see text), whereas that at the hemes a and a3 propionate–Arg(I-481/482) cluster (acceptor A) is only slightly higher than that of E(I-286) in the wild-type CcO. In the ND(I-139) mutant CcO proton transfer from E(I-286) to A is impaired due to the increased pKa of E(I-286). (C) A schematic representation of the reaction of CcO having a reduced binuclear center (state R) with dioxygen. Reduction of the oxidized (state O) binuclear center (with two electrons) is associated with net proton uptake from the bulk solution. Oxygen binds to the reduced heme a3 (state A) after which the O[ONK]O bond is broken, forming state PM. The transfer of the third and fourth electron (from an external electron donor) to the binuclear center are each associated with the uptake of one proton from solution through the D pathway, forming states F and O, respectively. If the CcO is initially fully reduced (blue pathway), after binding of O2 an electron is transferred rapidly from heme a to the binuclear center with a time constant of 50 μs, followed by proton uptake from solution, forming state F with a time constant of ≈100 μs. The fourth electron is transferred from CuA through heme a. The images in A and B were prepared by using VISUAL MOLECULAR DYNAMIC software (8).

The reaction sequence of reduced CcO from R. sphaeroides with O2 is illustrated in Fig. 1C (see ref. 28 for example). The reduced binuclear center (with two electrons, state R) binds O2 forming the A state with a time constant of ≈10 μs(at1mMO2). The binding of O2 is followed by breaking of the O O bond and formation of a ferryl state, denoted PM, with a time constant of ≈300 μs. The consecutive transfer of a third and fourth electron to the catalytic site are each accompanied by the uptake of one proton through the D pathway to form the F and O states, respectively (28–30). The individual steps of the reaction can be examined by investigating the reaction of the fully reduced CcO with O2 (i.e., starting with four electrons within CcO, see blue path in Fig. 1C). Because both heme a and CuA are reduced in the fully reduced CcO, after binding of O2 to heme a3 (state A), an electron is transferred rapidly to the binuclear center from heme a with a time constant of ≈50 μs, associated with breaking of the O O bond, forming a ferryl state denoted PR (31–34). Thus, the difference between states PM and PR is the additional electron at the catalytic site. This additional electron yields a protonatable group with a high proton affinity in the latter state. Because the transfer of the third electron to the catalytic site is faster than the transfer of the proton, formation of intermediate PR is followed by proton uptake with a time constant of ≈100 μs (at pH 7.5) forming intermediate F (28, 35, 36) (see blue arrows in Fig. 1C). Thus, an investigation of the reaction of the fully reduced CcO with O2 makes it possible to specifically investigate the proton-transfer reaction from solution to the binuclear center through the D pathway (see PR → F transition in Fig. 1C).

In this work, we examined a mutant of the R. sphaeroides CcO in which Asn-139 in subunit I [N(I-139)], located near the entrance of the D pathway (see Fig. 1B), is replaced by an Asp [ND(I-139)]. The specific activity of O2 reduction of this mutant CcO is twice that of the wild-type CcO, but it does not pump protons (ref. 37, see also ref. 38). There are previously reported results from studies of CcO with site-specific mutations in the D pathway, which yield an enzyme that does not pump protons, but in most cases these mutant CcOs have substantially reduced oxidase (O2 reduction) activities due to inhibition of proton uptake through the D pathway (for examples, see refs. 10 and 39). The cause of the uncoupling of proton pumping from the oxidase activity in the ND(I-139) CcO is obviously due to a different reason, because the high activity shows that proton transfer through the D pathway is not impeded. Consequently, the ND(I-139) mutant CcO is an ideal system for investigation of the proton-pumping mechanism of CcO. Previous studies have indicated that the proton-pumping stoichiometry of CcO may be related to the apparent pKa of E(I-286) (40). Therefore, we examined the pH dependence of the reaction of the fully reduced CcO with O2. The results are discussed in terms of a possible proton pumping mechanism of CcO in which E(I-286) serves as a ratchet that distributes substrate and pumped protons to the catalytic site and a proton acceptor on the output (positive) side of CcO, respectively.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of CcO. Histidine-tagged wild-type and mutant CcO were purified from R. sphaeroides, and the concentration was determined by using UV-visible spectroscopy as described (41). Further purification was done by using fast protein liquid chromatography (Amersham Pharmacia, AKTA-519) with tandem DEAE-5PW columns (Toso-Haas) (42).

Measurements of Proton Pumping. CcO-containing liposomes were prepared in H2O as described (43). For measurements in D2O, the same proteoliposome batch was used and H2O was exchanged for D2O by using size exclusion chromatography on a PD-10 column (Amersham Pharmacia), which was preequilibrated with D2O. Measurements were made in 45 mM KCl/44 mM sucrose/1 mM EDTA/100 μM phenol red, pH-meter reading 7.5. Proton pumping was investigated upon mixing reduced cytochrome c (by hydrogen gas using platinum black as a catalyst, ref. 44) and the CcO-containing liposomes in the presence of 10 μM valinomycin by using a stopped-flow apparatus (Applied Photophysics, the mixing time was ≈2 ms). Next, 5 μM of the proton ionophore carbonylcyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) was added to the proteoliposome sample and the measurements were repeated with the uncoupled system. The pH changes were determined from absorbance changes of the dye phenol red at 558.7 nm, which is an isosbestic point for cytochrome c oxidation.

Measurement of the Reaction Between Fully Reduced CcO and Oxygen. CcO at a concentration of 15 μM, solubilized in 0.1% dodecyl-β-d-maltoside/100 mM KCl/100 μM Hepes, was reduced with sodium ascorbate (5 mM) and PMS (1 μM) under N2 atmosphere, followed by exchange of N2 by CO (1 mM). Care was exercised to keep the pH ≈7.5. The CcO–CO complex was mixed at a ratio of 1:5 with an O2-saturated buffer-containing solution (100 mM) in a stopped-flow apparatus (≈10 ms mixing time). The pH after mixing was determined by the pH of the O2-saturated buffer solution. About 100 ms after mixing, CO was dissociated from CcO by means of a 6-ns laser (Quantel Brilliant B) flash at 532 nm (flow-flash technique). The buffers Bis-Tris (pKa 6.5), Hepes (pKa 7.55), and CAPS (pKa 10.4) at 100 mM were used, depending on pH. The pH was adjusted by additions of HCl or KOH. The reaction was followed by recording the absorbance changes at single wavelengths (445 nm, 580 nm, 605 nm, and 830 nm; for a detailed description of the experimental setup, see ref. 11). The cuvette path length was 1.00 cm. The time-resolved absorbance changes, measured at different wavelengths, were fitted globally to a multiexponential function by using the pro-k software (Applied Photophysics, Surrey, U.K.). The rate constants of the transitions were extracted from these fits.

Results

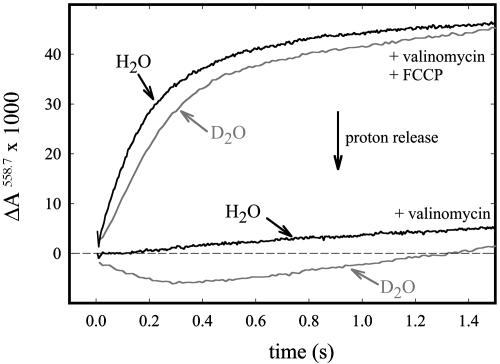

Proton Pumping. Proton pumping was investigated by mixing proteoliposomes containing CcO with reduced cytochrome c in the presence of O2 and the pH-indicator dye phenol red. Absorbance changes of the dye were monitored at 558.7 nm (ΔA558.7). The K+ ionophore valinomycin was added to prevent the buildup of an electrical gradient across the membrane. As shown in Fig. 2 (see also ref. 37), there was no acidification of the outside bulk solution during turnover of the ND(I-139) mutant CcO (lower trace, H2O), which shows that the mutant CcO does not pump protons at pH 7.5 in H2O. However, when the experiment was done in D2O (lower trace, D2O), we observed a decrease in absorbance, consistent with acidification of the bulk solution. This result shows that in D2O proton pumping was partly restored to ≈0.2 pumped H+/e–. Addition of the proton ionophore CCCP resulted in an increase in absorbance of the pH indicator dye during turnover, consistent with a net uptake of protons. Because in the presence of CCCP the net change in proton concentration on both the inside and outside of the proteoliposomes is monitored, this increase in absorbance corresponds to an average uptake of one proton per oxidized cytochrome c, associated with reduction of O2 to water. This change in absorbance was slower in D2O than in H2O (see Fig. 2) because the turnover rate of CcO slows in D2O.

Fig. 2.

Proton pumping by CcO reconstituted in phospholipid vesicles in H2O and D2O as indicated. With valinomycin (K+ ionophore), only the net proton release to the outside of the vesicles is monitored. With both valinomycin and CCCP (H+ ionophore) the net proton consumption by CcO is monitored (an average of one H+ per electron). The slow drift is due to proton leakage across the vesicles. The experimental conditions are described in Materials and Methods.

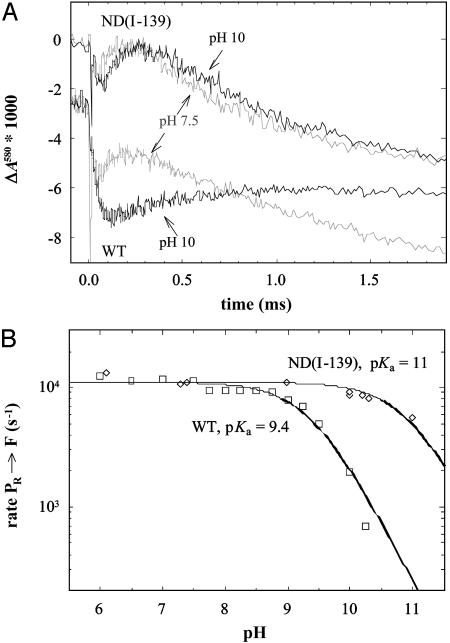

Internal Proton Transfer During the PR → F Transition. To determine the transition rates between the intermediate states during reaction of reduced CcO with O2, a solution of the fully reduced CcO–CO complex was mixed with an O2-saturated solution, followed by flash-induced dissociation of CO. Fig. 3A shows absorbance changes at 580 nm (ΔA580) associated with stepwise oxidation of wild-type and ND(I-139) mutant CcO in the presence of O2. With the wild-type CcO at pH 7.5 the initial decrease in absorbance at t = 0 is due to the dissociation of CO. It is followed by a small decrease in absorbance with a time constant of ≈50 μs, associated with formation of the PR state (see time range ≈0–100 μs). The increase in absorbance with a time constant of ≈100 μs (see time range ≈100–300 μs) and the following decrease in absorbance with a time constant of ≈1 ms are associated with the PR → F and F → O transitions, respectively. At pH 10, with the wild-type CcO both transitions were a factor of 5 slower (τPR→F ≅ 500 μs, τF→O ≅ 5 ms) than at pH 7.5 (the decrease in absorbance associated with the F → O transition at pH 10 is not seen on the time scale shown in Fig. 3A). It should be noted that although the kinetic phases associated with formation of the PR state (τ ≅ 50 μs) have the same amplitudes at pH 7.5 and pH 10, the amplitude of this phase appears to be larger at pH 10 than at pH 7.5 because the following PR → F transition is slower at pH 10.

Fig. 3.

(A) Absorbance changes at 580 nm associated with the PR → F (increase in absorbance, τ ≅ 100 μs at pH 7.5) and F → O (decrease in absorbance, τ ≅ 1 ms at pH 7.5) transitions in the wild-type (WT, two lower traces) and ND(I-139) mutant (two upper traces) CcOs at pH 7.5 and 10, as indicated in the graph. The traces measured with the wild-type CcO have been moved down for clarity (compare absorbance levels at t < 0). Conditions: 2.5 μMCcO solubilized in 0.1% dodecyl-β-d-maltoside, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM sodium ascorbate, 1 μM PMS, 1 mM CO. The buffers Hepes and CAPS at 100 mM were used at pH 7.5 and 10, respectively. (B) The rate of the PR → F transition (see A) in the wild-type (squares) and ND(I-139) (circles) CcOs as a function of pH. The solid lines are fits of the data with standard titration curves with pKa values of 9.4 and 11, respectively.

Remarkably, with the ND(I-139) mutant CcO, the time constants of the PR → F and F → O transitions were essentially the same at pH 10 as at pH 7.5 (Fig. 3A, two upper graphs). Fig. 3B shows the pH dependence of the PR → F transition rate in the wild-type and ND(I-139) CcOs. We focus on this transition because the results from previous studies have shown that the rate-limiting step of the PR → F transition is an internal proton transfer, most likely from E(I-286) to the catalytic site (45–48). Therefore, the rate of the PR → F transition depends on the extent of protonation of E(I-286) (45), and measuring this rate provides a way to determine the effective pKa value of E(I-286). As seen in Fig. 3B, the apparent pKa in the pH-dependence of the PR → F rate in the ND(I-139) CcO increased by ≈1.6 pH units, from pH 9.4 to ≈11. As described in Materials and Methods, these experiments were done by mixing an unbuffered CcO solution with a buffer-containing solution that determined the final pH after mixing. This procedure was exercised to avoid a prolonged exposure of CcO to high pH. Earlier studies showed that the CcO equilibrates with the final pH within the time (≈100 ms) between mixing and initiation of the reaction by flash photolysis of CO (45). As a control, in the present study the experiments at pH 10.2 were also repeated with CcO equilibrated at the final pH before mixing with the O2 solution. The same results were obtained with both approaches.

The amplitude of the 580-nm absorbance increase, associated with the PR → F transition in the ND(I-139) mutant CcO, was the same in the entire measured pH range (up to pH 11, compare data at pH 7.5 and 10 in Fig. 3A) and the same as that observed with the wild-type CcO at pH 7.5. This result shows that in the ND(I-139) mutant CcO the extent of formed F state was the same up to pH 11.

It should be noted that the reaction pathway (i.e., the buildup and decay of the intermediate states) were the same at high as at low pH, which shows that CcO is fully functional also in the high-pH range. In addition, the observation of an essentially constant F-formation rate up to pH 10 in the ND(I-139) mutant CcO also indicates that there are no unspecific structural changes induced by the high pH.

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated a mutant CcO from R. sphaeroides in which proton pumping is uncoupled from the oxidase activity. The objective of the study was to understand the basis for this uncoupling at the molecular level, which provides information toward understanding the proton-pumping mechanism in the wild-type CcO. The results from previous studies have shown that both substrate and pumped protons are transferred through the D pathway, where E(I-286) presumably is the branching point for the pumped vs. substrate protons, and the proton acceptor in the exit pathway is likely to consist of a cluster of protonatable residues formed by the heme a3/heme a propionates and two arginine residues Arg(I-481)/Arg(I-482) (17–24) (see Fig. 1B).

To investigate the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of the proton-transfer reactions through the D pathway in the ND(I-139) mutant CcO, we studied the pH dependence of the PR → F transition. The proton-transfer reaction associated with this transition takes place through the D pathway in two distinct steps; a rate-limiting proton transfer from E(I-286) to the catalytic site with a time constant of ≈100 μs is followed by rapid (<100 μs) reprotonation of E(I-286) from the N-side bulk solution (ref. 46, see also ref. 49). An investigation of the pH dependence of the rate of the internal proton transfer from E(I-286) to the binuclear center showed that the apparent pKa of E(I-286) in the wild-type CcO is 9.4 (45).

The crystal structure of CcO from R. sphaeroides shows that the D pathway “below” E(I-286) consists of an array of hydrogen-bonded water molecules (see Fig. 1B), providing a rapid proton connectivity between the N-side bulk solution and the Glu. The distance between E(I-286) and the binuclear center (≈10 Å) is too long to allow direct transfer of protons between these sites. Even though no water molecules are seen in the hydrophobic regions between E(I-286) and the binuclear center, or between E(I-286) and the heme propionates region, the results from theoretical calculations have shown that a number of water molecules are likely to be found in these cavities (24–26). These chains of water molecules form an Y-shaped structure originating from the glutamate, with one “arm” branching toward the binuclear center and one arm branching toward the heme propionates region (see Fig. 1B). Because of the hydrophobic properties of these cavities, the water molecules are likely to be unstructured and they may form stable hydrogenbonded chains only transiently during catalytic turnover (26), which most likely is the reason why they are not seen in the crystal structure.

The proton-transfer rate between E(I-286) and the binuclear center is not simply determined by the driving force between the donor and the acceptor upon F formation because the observed rate at neutral pH is about the same in the wild-type as in the ND(I-139) mutant CcO, even though the pKa of the donor is higher in the mutant CcO. The results from previous studies indicate that the proton-transfer reaction is preceded by a structural reorientation of E(I-286) (50). In addition, the formation of the proton-transferring water structure between E(I-286) and the catalytic site may be rate limiting for proton transfer between the sites (see ref. 25).

The observation that the amplitude of the absorbance increase at 580 nm was the same with the ND(I-139) mutant CcO at high pH (up to 11) as with the wild-type CcO at pH 7.5 (Fig. 3A) indicates that the extent of formation of the F intermediate was ≈100% in the ND(I-139) mutant CcO at high pH. This observation implies that the proton-transfer reaction from E(I-286) to the catalytic site during the PR → F transition is irreversible even at pH 11. This means that the proton acceptor at the catalytic site, presumably the Tyr-288– [Y(I-288)–] or OH– bound to  (see Fig. 1C), has a pKa of ≥12, providing a large driving force for the transfer of the substrate proton and making the PR → F transition insensitive to the 1.6 pH unit change in the pKa of the E(I-286) proton donor. At the same time, the increase in the pKa of E(I-286) correlates with uncoupling of the catalytic turnover from proton pumping. It is important to note that the cause of the uncoupling of proton pumping from the oxidase activity in the ND(I-139) CcO is not due to impeded proton transfer through the D pathway from the N-side protein surface to E(I-286). On the basis of the results from the present study, we speculate that proton pumping is impaired in the mutant CcO because of the increased pKa of E(I-286), which results in decreasing the effective protonation rate of the heme propionate-arginine cluster. This conclusion, together with the observation of structural changes in the heme propionate–arginine cluster in the crystal structure of mutant R. sphaeroides CcO in which E(I-286) was replaced by a nonprotonatable glutamine [EQ(I-286)] (7), sets the basis for a model for proton pumping by CcO (see also ref. 51). The crystal structure shows that a hydrogen bond that is observed in the wild-type CcO between the E(I-286) side chain and the carbonyl oxygen of M(I-107) is absent in the EQ(I-286) mutant CcO (7) (as well as in the wild-type CcO at pH 10, unpublished data). The structural consequences of the loss of this hydrogen bond extend to the region of the proposed proton acceptor group (A in Fig. 1B). In this region, the distance between the D-ring propionate of heme a3 and R(I-481) increases, and a water molecule enters between the two groups. In addition, there is a rotation of the R(I-482) side chain. Hence, there appears to be a structural linkage between perturbations at the site of E(I-286) and the region of the exit pathway. The deprotonation of E(I-286) upon proton transfer to the catalytic site, which would also eliminate the hydrogen bond to M(I-107) carbonyl oxygen, is likely to trigger the same conformational changes in the protein. According to the model, the proton transfer from E(I-286) to the catalytic site renders a transiently unprotonated E(I-286), which results in the above described local structural changes. The local structural changes around the heme propionates/Arg(I-481)/Arg(I-482) cluster result in creation of an acceptor (A in Fig. 1B) for pumped protons in the proton-exit pathway. Thus, the initial proton transfer from E(I-286) to the catalytic site results in proton transfer through the D pathway to A.

(see Fig. 1C), has a pKa of ≥12, providing a large driving force for the transfer of the substrate proton and making the PR → F transition insensitive to the 1.6 pH unit change in the pKa of the E(I-286) proton donor. At the same time, the increase in the pKa of E(I-286) correlates with uncoupling of the catalytic turnover from proton pumping. It is important to note that the cause of the uncoupling of proton pumping from the oxidase activity in the ND(I-139) CcO is not due to impeded proton transfer through the D pathway from the N-side protein surface to E(I-286). On the basis of the results from the present study, we speculate that proton pumping is impaired in the mutant CcO because of the increased pKa of E(I-286), which results in decreasing the effective protonation rate of the heme propionate-arginine cluster. This conclusion, together with the observation of structural changes in the heme propionate–arginine cluster in the crystal structure of mutant R. sphaeroides CcO in which E(I-286) was replaced by a nonprotonatable glutamine [EQ(I-286)] (7), sets the basis for a model for proton pumping by CcO (see also ref. 51). The crystal structure shows that a hydrogen bond that is observed in the wild-type CcO between the E(I-286) side chain and the carbonyl oxygen of M(I-107) is absent in the EQ(I-286) mutant CcO (7) (as well as in the wild-type CcO at pH 10, unpublished data). The structural consequences of the loss of this hydrogen bond extend to the region of the proposed proton acceptor group (A in Fig. 1B). In this region, the distance between the D-ring propionate of heme a3 and R(I-481) increases, and a water molecule enters between the two groups. In addition, there is a rotation of the R(I-482) side chain. Hence, there appears to be a structural linkage between perturbations at the site of E(I-286) and the region of the exit pathway. The deprotonation of E(I-286) upon proton transfer to the catalytic site, which would also eliminate the hydrogen bond to M(I-107) carbonyl oxygen, is likely to trigger the same conformational changes in the protein. According to the model, the proton transfer from E(I-286) to the catalytic site renders a transiently unprotonated E(I-286), which results in the above described local structural changes. The local structural changes around the heme propionates/Arg(I-481)/Arg(I-482) cluster result in creation of an acceptor (A in Fig. 1B) for pumped protons in the proton-exit pathway. Thus, the initial proton transfer from E(I-286) to the catalytic site results in proton transfer through the D pathway to A.

A basic assumption of models addressing the function of CcO is that the proton to be pumped must be transferred to the acceptor site before the substrate proton reaches the binuclear center, otherwise the free energy available from the redox reaction for proton pumping is lost. This condition is not fulfilled by the model outlined above. However, if (substrate) proton transfer to the catalytic site is tightly coupled to an endergonic structural rearrangement, which renders an acceptor for protons to be pumped, the free energy is conserved. A requirement for efficient proton pumping is that the proton is transferred to the acceptor group before E(I-286) is reprotonated and/or before the structural change relaxes to the original conformation. This is achieved if the pKa of A is higher than that of E(I-286) and if the D pathway allows rapid proton transfer to A when E(I-286) is in the unprotonated state (for a detailed discussion, see ref. 51).

The increased apparent pKa of E(I-286) in the ND(I-139) mutant CcO provides a plausible explanation for the deficiency of proton pumping in this enzyme. As discussed above, the proton acceptor at the catalytic site has a pKa≥12. We propose that the proton acceptor A in the pumping pathway, in contrast, has a pKa that is only slightly higher (≤1.6 units) than that of E(I-286), making the transfer rate of the pumped protons sensitive to either electrostatic or conformational perturbations of E(I-286) (see ref. 40). Thus, because in the ND(I-139) mutant enzyme the pKa of E(I-286) is increased, E(I-286) becomes reprotonated (and the structure relaxes to the initial state) before a proton is transferred to the acceptor A (see Fig. 1B). Because not only the PR → F transition (which may not necessarily be part of the catalytic reaction in vivo; refs. 2 and 52, but see ref. 53), but also other reaction steps associated with proton pumping during catalytic turnover involve proton transfer from E(I-286) to the catalytic site, the model can be generalized also to proton pumping during other transitions of the reaction cycle (see pathway through PM in Fig. 1C).

This model also explains why proton pumping is partly restored in D2O, because the proton pumping efficiency (stoichiometry) is determined by the relative rates of protonation of acceptor A and reprotonation of E(I-286) (followed by the structural relaxation). Thus, if, with the ND(I-139) mutant CcO in D2O, the relative rates of proton transfer to A, reprotonation of E(I-286), and reformation of the hydrogen bond between E(I-286) and M(I-107) [i.e., relaxation of the structure to that with protonated E(I-286)] are altered, then in a fraction of the CcO population a proton may be transferred to A.

Summary

In conclusion, our results show that the uncoupling of the proton pump in the ND(I-139) mutant CcO correlates with an increase in the apparent pKa of E(I-286) by 1.6 pH units. The proposed model includes E(I-286) as the branch point in the D pathway, providing protons both to the catalytic site and to a proton acceptor located in the exit pathway of the pump. Normal function of the proton pump requires a proton to be transferred within a limited time to a proton acceptor in the proton “input” mode. A delay in this proton transfer results in loss of proton pumping.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pia Ädelroth, Margareta Blomberg, Magnus Brändén, Gwen Gilderson, Mikael Oliveberg, Per Siegbahn, and Alexei Stuchebrukhov for valuable discussions. This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (to P.B.), Human Frontier Science Program Grant RG0315 (to R.B.G. and P.B.), and National Institutes of Health Grant HL16101 (to R.B.G.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: CcO, cytochrome c oxidase; N-side, negative side of the membrane; P-side, positive side of the membrane; CCCP, carbonylcyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone.

References

- 1.Ferguson-Miller, S. & Babcock, G. T. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2889–2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babcock, G. T. & Wikström, M. (1992) Nature 356, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaslavsky, D. & Gennis, R. B. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1458, 164–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukihara, T., Aoyama, H., Yamashita, E., Tomizaki, T., Yamaguchi, H., Shinzawa-Itoh, K., Nakashima, R., Yaono, R. & Yoshikawa, S. (1996) Science 272, 1136–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwata, S., Ostermeier, C., Ludwig, B. & Michel, H. (1995) Nature 376, 660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abramson, J., Riistama, S., Larsson, G., Jasaitis, A., Svensson-Ek, M., Laakkonen, L., Puustinen, A., Iwata, S. & Wikström, M. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 910–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svensson-Ek, M., Abramson, J., Larsson, G., Törnroth, S., Brzezinski, P. & Iwata, S. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 321, 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. (1996) J. Mol. Graphics 14, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ädelroth, P., Gennis, R. B. & Brzezinski, P. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 2470–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstantinov, A. A., Siletsky, S., Mitchell, D., Kaulen, A. & Gennis, R. B. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 9085–9090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brändén, M., Sigurdson, H., Namslauer, A., Gennis, R. B., Ädelroth, P. & Brzezinski, P. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5013–5018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruitenberg, M., Kannt, A., Bamberg, E., Ludwig, B., Michel, H. & Fendler, K. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4632–4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wikström, M., Jasaitis, A., Backgren, C., Puustinen, A. & Verkhovsky, M. I. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1459, 514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jünemann, S., Meunier, B., Gennis, R. B. & Rich, P. R. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 14456–14464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosler, J. P., Shapleigh, J. P., Mitchell, D. M., Kim, Y., Pressler, M. A., Georgiou, C., Babcock, G. T., Alben, J. O., Ferguson-Miller, S. & Gennis, R. B. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 10776–10783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brzezinski, P. & Ädelroth, P. (1998) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 30, 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behr, J., Michel, H., Mäntele, W. & Hellwig, P. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 1356–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofacker, I. & Schulten, K. (1998) Proteins 30, 100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puustinen, A. & Wikström, M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 35–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills, D. A., Florens, L., Hiser, C., Qian, J. & Ferguson-Miller, S. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1458, 180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mills, D. A. & Ferguson-Miller, S. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1555, 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michel, H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12819–12824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pomès, R., Hummer, G. & Wikström, M. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1365, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riistama, S., Hummer, G., Puustinen, A., Dyer, R. B., Woodruff, W. H. & Wikström, M. (1997) FEBS Lett. 414, 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wikström, M., Verkhovsky, M. I. & Hummer, G. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1604, 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng, X., Medvedev, D. M., Swanson, J. & Stuchebrukhov, A. A. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1557, 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jünemann, S., Meunier, B., Fisher, N. & Rich, P. R. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 5248–5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ädelroth, P., Ek, M. & Brzezinski, P. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1367, 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paula, S., Sucheta, A., Szundi, I. & Einarsdóttir, Ó. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 3025–3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallén, S. & Nilsson, T. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 11853–11859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitagawa, T. & Ogura, T. (1998) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 30, 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proshlyakov, D. A., Pressler, M. A., DeMaso, C., Leykam, J. F., DeWitt, D. L. & Babcock, G. T. (2000) Science 290, 1588–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan, J. E., Verkhovsky, M. I., Palmer, G. & Wikström, M. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 6882–6892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karpefors, M., Ädelroth, P., Namslauer, A., Zhen, Y. J. & Brzezinski, P. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 14664–14669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell, R., Mitchell, P. & Rich, P. R. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1101, 188–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveberg, M., Hallén, S. & Nilsson, T. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 436–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pawate, A. S., Morgan, J., Namslauer, A., Mills, D., Brzezinski, P., Ferguson-Miller, S. & Gennis, R. B. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 13417–13423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfitzner, U., Hoffmeier, K., Harrenga, A., Kannt, A., Michel, H., Bamberg, E., Richter, O. M. H. & Ludwig, B. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 6756–6762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fetter, J. R., Qian, J., Shapleigh, J., Thomas, J. W., García-Horsman, A., Schmidt, E., Hosler, J., Babcock, G. T., Gennis, R. B. & Ferguson-Miller, S. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 1604–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilderson, G., Aagaard, A. & Brzezinski, P. (2002) Biophys. Chem. 98, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitchell, D. M. & Gennis, R. B. (1995) FEBS Lett. 368, 148–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hiser, C., Mills, D. A., Schall, M. & Ferguson-Miller, S. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 1606–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jasaitis, A., Verkhovsky, M. I., Morgan, J. E., Verkhovskaya, M. L. & Wikström, M. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 2697–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosen, P. & Pecht, I. (1976) Biochemistry 15, 775–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Namslauer, A., Aagaard, A., Katsonouri, A. & Brzezinski, P. (2003) Biochemsitry 42, 1488–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smirnova, I. A., Ädelroth, P., Gennis, R. B. & Brzezinski, P. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 6826–6833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karpefors, M., Ädelroth, P., Zhen, Y., Ferguson-Miller, S. & Brzezinski, P. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13606–13611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ädelroth, P., Karpefors, M., Gilderson, G., Tomson, F. L., Gennis, R. B. & Brzezinski, P. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1459, 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nyquist, R. M., Heitbrink, D., Bolwien, C., Gennis, R. B. & Heberle, J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8715–8720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karpefors, M., Ädelroth, P. & Brzezinski, P. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 6850–6856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brzezinski, P. & Larsson, G. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1605, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oliveberg, M. & Malmström, B. G. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 3560–3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jasaitis, A., Backgren, C., Morgan, J. E., Puustinen, A., Verkhovsky, M. I. & Wikström, M. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 5269–5274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]