Abstract

E. coli ribonucleotide reductase is an α2β2 complex that catalyzes the conversion of nucleoside 5′-diphosphates (NDPs) to deoxynucleotides (dNDPs). The active site for NDP reduction resides in α2, and the essential diferric-tyrosyl radical (Y122•) cofactor that initiates radical transfer to the active site cysteine in α2 (C439), 35 Å removed, is in β2. The oxidation is proposed to involve a hopping mechanism through aromatic amino acids (Y122→W48→Y356 in β2 to Y731→Y730→C439 in α2) and reversible proton coupled electron transfer (PCET). Recently 2,3,5-F3Y (F3Y) was site-specifically incorporated in place of Y356 in β2, and 3-NH2Y (NH2Y) in place of Y731 and Y730 in α2. A pH rate profile with F3Y356-β2 suggested that as the pH is elevated, the rate-determining step of RNR can be altered from a conformational change to PCET and that the altered driving force for F3Y oxidation, by residues adjacent to it in the pathway, is responsible for this change. Studies with NH2Y731(730)-α2/β2/CDP/ATP resulted in detection of NH2Y radical (NH2Y•) intermediates capable of dNDP formation. In this study, the reaction of F3Y356-β2/α2/CDP/ATP has been examined by stopped flow (SF) absorption and rapid freeze quench EPR spectroscopy and has failed to reveal any radical intermediates. F3Y356-β2/CDP/ATP has also been examined with NH2Y731-α2 (or NH2Y730-α2) by stopped-flow kinetics from pH 6.5–9.2 and revealed rate constants for NH2Y• formation that support a change in rate limiting step at elevated pH. The results together with kinetic simulations provide a guide for future studies to detect radical intermediates in the pathway.

Ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) are responsible for reduction of nucleotides to 2′-deoxynucleotides (dNDPs), supplying the precursors required for DNA replication and repair (1, 2). Active E. coli RNR is a 1:1 complex of two homodimeric subunits: α2 and β2 (3-5). α2 harbors the active site, where thiyl radical-mediated (C439•) nucleotide reduction occurs (6-8), and the binding sites for allosteric effectors, which control the rate and specificity of reduction (9). β2 houses the essential diferric-tyrosyl radical (Y122•) cofactor (10, 11). Each turnover requires oxidation of C439 in α2 by Y122• in β2 (12). A structure of the active α2β2 complex is unavailable. However, a docking model of this complex, based on shape complementarity of the structures of the individual subunits, led Uhlin and Eklund to propose that radical transfer between subunits occurs over a distance of 35 Å by a pathway involving aromatic amino acid radicals (Fig. 1 A, B) (13). Mutagenesis studies suggested that the residues shown in Figs. 1A and 1B are important for catalysis (14-16). The inactivity of the mutants, however, precluded mechanistic studies. We have recently incorporated unnatural amino acids site-specifically into the pathway. Our studies have provided direct evidence for the three proposed redox-active tyrosines (Y356, Y731 and Y730) (17-19), the pathway dependence (20), and the docking model (21). In the present study, we investigate 2,3,5-F3Y (F3Y) site-specifically incorporated in place of Y356 in β2 with wt-α2 and with 3-NH2Y (NH2Y) incorporated site-specifically in place of Y731 or Y730 in α2 (Figs. 1A & 1B) using rapid freeze quench (RFQ) EPR and stopped flow (SF) absorption spectroscopies. These studies provide evidence that altering the driving force for oxidation of F3Y356 by adjacent residues in the pathway by raising the pH, can change the rate-limiting step of RNR from a conformational change to proton coupled electron transfer (PCET) and that no radical intermediates are detected.

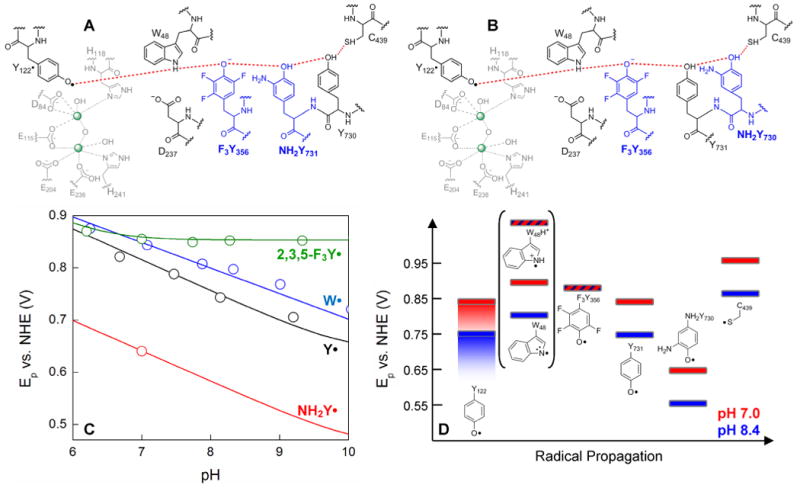

Figure 1.

The proposed radical initiation pathway and its energetics in E. coli RNR with site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids (13). Residues in grey are associated with the diferric cluster, in black are proposed pathway residues (13), and in blue are the unnatural amino acids (F3Y and NH2Y) to probe the pathway in the present studies. Note that the structural location of Y356 is unknown. (C) Peak potentials (Ep) for free (NH2Y), and N-acetylated and C-amidated (Y, W, F3Y) amino acids, as a function of pH. The Eps for Y•, W• and 2,3,5-F3Y• have been previously determined (25) and the trace for NH2Y• has been generated from the reduction potential determined at pH 7, assuming Nernstian behavior (27). (D) The Eps from panel (C) have been assigned to residues in the radical propagation pathway to provide a qualitative energy landscape. Red and blue rectangles represent the peak potentials for each amino acid at pH 7.0 and 8.4, respectively. The peak potentials of WH•+ and F3Y• are represented by red rectangles with blue diagonal lines as they do not change between pH 7–8.4. The Ep range for Y122• is expanded (indicated by shading), because its properties relative to the other three Ys, including its pKa, are unique. Y122• has a half-life of ∼4 days and likely represents a thermodynamic hole (45). Brackets are placed around W48 as no direct evidence is available that places it on the pathway. If it is on the pathway, its protonation state, W48H•+ vs. W48•, that participates in radical transfer is unknown, and therefore Eps for both of these species are included.

Y analogs with altered reduction potentials and/or pKas were of interest for site-specific incorporation into RNR, as oxidation of Y is a PCET process with peak potentials (Ep) being modulated by pH (Fig. 1C) (22-24). Studies on blocked-FnY analogs, N-acetylated and C-amidated, revealed the appropriateness of these analogs for studying PCET as their phenolic pKas ranged from 5.6 to 8.4 and their Eps varied from −50 mV to +270 mV relative to blocked Y in the physiological pH range (25). Perturbation of both of these properties could be mechanistically informative in studying PCET.

Expressed protein ligation (EPL) was used to incorporate FnYs (where n=1–4) (18, 25, 26) in place of Y356 in β2. To obtain sufficient amounts of semisynthetic β2 to carry out physical biochemical studies, two additional mutations, V353G and S354C in β2, were required. This double mutant, V353G/S354C-β2 at pH 7.6 had 25 % the activity of the wt-β2. Henceforth, intein wt-β2 refers to V353G/S354C-β2 made by EPL.

The pH rate profiles of FnY356-β2s with α2, CDP and ATP were studied from pH 6.5 to 9.2 and the ability to produce dNDPs compared to intein wt-β2 (18). Analysis of the rates of dNDP formation relative to intein wt-β2 vs. the relative differences in the Ep of each FnY relative to Y at each pH (Fig. 1C), revealed three different activity regimes. In the first regime, where the Ep difference between FnY and Y varied from −40 to +80 mV, the rate-limiting step in dNDP formation is a conformational change that precedes radical transfer. The intein-wt β2 and FnY-β2s within this range are 100 % active. In the second regime, where the Ep difference increased from +80 to +200 mV greater than Y, the specific activities of mutant RNRs decreased from 100 % to a few %. These data suggested that the rate-limiting step had changed from a conformational change to a step (or steps) in the radical propagation process. Finally, in the third regime, where the Ep difference was greater than 200 mV, no dNDPs are produced and the radical transfer process was completely shut down. If the interpretation of the pH rate profiles of FnY-β2s is correct, then it may be possible to detect transient intermediates during radical propagation in the second activity regime. Our studies suggested that F3Y356-β2 would be the most interesting FnY-β2 to investigate in this regime.

The proposed pathway (Fig. 1A) has been further explored by replacing Y730 and Y731 in α2 with NH2Y, a tyrosine analog that is easier to oxidize than Y by 190 mV at pH 7 (Fig. 1C). α in these studies has a single mutation: Y to NH2Y (27). SF experiments in the presence of β2, CDP and ATP revealed that an NH2Y radical (NH2Y•) is generated in a kinetically competent fashion in two phases with rate constants of 18 s-1 and 2.5 s-1 with Y730NH2Y-α2 and of 12 s-1 and 2.5 s-1 with Y730NH2Y-α2 at pH 7.6 (19). These studies and more recent studies (Minnihan, Seyedsayamdost & Stubbe, manuscript in preparation) have further revealed that these mutants can make dNDPs at rates of 0.3–0.6 s-1, substantially slower than the rates of NH2Y• formation.

In the present paper, F3Y356-β2 was examined with α2/CDP/ATP to look for radical intermediates by SF and RFQ EPR spectroscopy and none were detected. The hypothesis that an Ep difference of >80 mV between F3Y and Y changes the rate-determining step of RNR from conformational gating to a step or steps involved in PCET has also been examined: F3Y-β2 was incubated with NH2Y731-α2 or NH2Y730-α2 and the pH rate profile of NH2Y• formation from pH 6.5 to 9.2 was investigated by SF absorption spectroscopy. The rate constants for NH2Y• formation are triphasic. Despite the kinetic complexity, they reveal that the pH rate profile for NH2Y• formation is very similar to that observed previously in the steady state for dNDP formation with F3Y356-β2/α2/CDP/ATP and are distinct from the steady state data with intein wt-β2 control. A kinetic model to accommodate these results is presented that supports the proposed shift in the rate-limiting step and the kinetic simulations provide an explanation for why transient radical intermediates are not detected. This model provides a framework for future studies involving FnY incorporation using evolved tRNA/tRNA synthetase pairs, and addressing the importance of W48 in the pathway (Figs. 1A & 1B).

Materials and Methods

Materials

[2-14C]-CDP (50 μCi/mL) was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals and calf-intestine alkaline phosphatase (20 U/μL) was from Roche. Lithium 8-hydroxyquinoline-6-sulfonate and Sephadex G-25 were from Sigma. 2-[N-morpholino]-ethanesulfonic acid (Mes), N-2-hydroxethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (Hepes), N-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl] -3-aminopropanesulfonic acid (Taps), 2-[cyclohexylamino]-ethanesulfonic acid (Ches) and Emulsifier-Safe scintillation liquid were obtained from EMD Bioscience. Slide-a-lyzer cassettes were from Pierce. α2 was expressed, purified, and pre-reduced as reported and had a specific activity of 2500 nmol/min mg (18, 28). E. coli thioredoxin (TR, 40 U/mg) (29) and TR reductase (TRR, 1800 U/mg) were isolated as previously described (30). Y730NH2Y-α2 and Y731NH2Y-α2 were isolated as previously described and had specific activities of 100 and 175 nmol/min mg, respectively (19).

Semisynthesis of F3Y356-β2

Generation of F3Y356-β2 by EPL and its purification were carried out as detailed previously (31).

Generation of apo F3Y356-β2 with lithium 8-hydroxyquinoline-6-sulfonate

The apo form of intein wt-β2 and F3Y356-β2 were generated by a modification of the procedure of Atkin et al (32). Briefly, a solution of 2.5 mL of each β2 variant (∼20 mg, 90 μM) was dialyzed against 500 mL of chelator solution consisting of 1 M imidazole, 30 mM NH2OH, 50 mM 8-hydroxyquinoline-6-sulfonate (pH 7.0) in a 3 mL Slide-a-lyzer cassette for 3 h. The chelator was then removed by dialysis against 4 L Hepes buffer (50 mM Hepes, 5 % glycerol, pH 7.6) for 3 h and further by desalting on a Sephadex G 25 column (1.5 × 23, 40 mL) equilibrated in Hepes buffer. This procedure gives the apo form of each β2 variant in 80–95 % yield. The concentration of apo β2 was determined using ε280 nm = 120 mM−1cm−1.

Reconstitution of apo β2

The apo form of each β2 variant was reconstituted as reported previously. This procedure yields a radical content of ∼1.2 Y122•/β2 as determined by the dropline procedure (33).

Spectrophotometric and radioactive RNR Assays

RNR activity assays were performed as previously described (18). The final concentration of α2 and β2 variants in these assays were each 3 μM. The specific activity of [2-14C] -CDP was 3800 cpm/nmol.

Single Wavelength and Diode Array SF Absorption Spectroscopy

SF absorption kinetics were performed on an Applied Photophysics DX. 17MV instrument equipped with the Pro-Data upgrade. The temperature was maintained at 25°C with a Lauda RE106 circulating water bath. Single wavelength kinetics experiments utilized PMT detection at 410 nm (λmax of Y122• with ε = 3700 M−1cm−1) (33), 510 nm (λmax of W• with ε = 2200 M−1cm−1) and 560 nm (λmax of WH•+ with ε = 3000 M−1cm−1) (34). Typically, pre-reduced α2 (50–70 μM) and ATP (6 mM) in one syringe were mixed with F3Y356-β2 (50–70 μM) and CDP (2 mM) in a 1:1 ratio in 50 mM Taps, 15 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.4. Time courses shown are the average of at least 5 individual traces. Diode array SF absorption spectroscopy was carried out with an Applied Photophysics PDA.1 Photodiode Array detector. The concentration of the reaction components were the same as described for single wavelength kinetics.

RFQ EPR Spectroscopy

RFQ EPR samples were prepared using an Update Instruments 1019 Syringe Ram Unit, a Model 715 Syringe Ram Controller and a quenching bath. The temperature of the liquid isopentane bath was controlled with a Fluke 52 Dual Input Thermometer, equipped with an Anritsu Cu Thermocouple probe for the isopentane bath and the funnel. Stainless steel packers were purchased from McMaster-Carr and were cut to a length of 40 cm and deburred at the MIT machine shop. The dead-time of the set-up was determined to be 16 ± 2 ms with two independent measurements of the myoglobin/NaN3 test reaction. A packing factor of 0.60 ± 0.05 was reproducibly obtained as tested with intein-wt β2 samples. Routinely, a ram push velocity of 1.25 or 1.6 cm/s was used and the displacement was adjusted to expel 300 μL sample after the reaction.

Operation of the apparatus was similar to the procedure previously described (35). Typically, pre-reduced α2 (50–70 μM) and ATP (6 mM) in one syringe were mixed with F3Y356-β2 and CDP (2 mM) in the second syringe in a 1:1 ratio in 50 mM Taps, 15 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.4. When the temperature of the EPR tube-funnel assembly had equilibrated to the bath temperature, the contents of each syringe were mixed rapidly in a mixing chamber and aged for a pre-determined time period by pushing the contents through a reaction loop. The sample was sprayed into the EPR tube-funnel assembly which was held at a distance of ≤1 cm from the spray nozzle. The assembly was immediately returned to the bath and the crystals allowed to settle for 15–30 s. The sample was then packed into the EPR tube using the stainless steel packers described above.

EPR spectra were recorded at the Department of Chemistry Instrumentation Facility on a Bruker ESP-300 X-band (9.4 GHz) spectrometer. Spectra at 77 K were recorded with a quartz finger dewar filled with liquid N2; spectra at 15 K were acquired with an Oxford liquid helium cryostat and an Oxford ITC 503 temperature controller. Unless noted otherwise, EPR parameters were as follows: Power = 50 μW, modulation amplitude = 1.5 G, modulation frequency = 100 kHz, time constant = 5.12 ms and scan time = 41.9 s.

pH Rate Profile of NH2Y• Formation in the Reaction of F3Y356-β2 with NH2Y-α2s monitored by SF-Absorption Spectroscopy

NH2Y-α2 was prepared and pre-reduced as detailed previously (19). In all experiments, pre-reduced NH2Y-α2 and ATP were mixed with F3Y356-β2 and CDP to yield final concentrations of 4 μM, 3 mM, 4 μM and 1 mM, respectively. Single wavelength kinetics were monitored using PMT detection at 320 nm (λmax of NH2Y731• with ε = 11000 M−1cm−1) or 325 nm (λmax of NH2Y730• with ε = 10500 M−1cm−1) (19). Reactions were carried out in 15 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM Goods Buffers [Mes (pH 6.5–7), Hepes (pH 7–8), Taps (pH 8–8.8) or Ches (pH 8.8–9.2) buffer] adjusted to the desired pH. Syringes and reaction lines were equilibrated in the desired buffer prior to the experiment. At each pH, 6-8 traces were averaged and analyzed using OriginPro Software. Iterative rounds of fitting were carried out until the R2 value was maximized (≥0.99) and the residual plot was randomly scattered around zero ± ≤0.001 AU.

Results

Pre-steady State Experimental Design

Previous pre-steady state examination of wt RNR at pH 7.6 has shown that production of dCDP is rate-limited by a conformational change that precedes radical transfer, resulting in a burst of dCDP formation in the first turnover with rate constants of 4.4–10 s−1 (36). In wt RNR, this conformational change(s) kinetically masks detection of the proposed aromatic amino acid radical intermediates during radical transfer (Figs. 1A & 1B). Thus, detection of transient radical intermediates requires, at a minimum, that the rate constant for radical transfer be diminished relative to that for the conformational step. Our previous results with FnY-β2s suggested that insertion of F3Y in place of Y356 provides a sufficient shift in the driving force for radical propagation, to make it rate-limiting at elevated pH (18). Thus it is possible that pathway radical intermediates could be detected by RFQ EPR methods at elevated pH.

Increasing the Y122• Radical Content of Semisynthetic F3Y356-β2

To maximize our chances of detecting low levels of pathway radical intermediates, we focused on increasing the concentration of Y122• in the semisynthetic β2s using the method of Atkins et al. (32). With both intein wt-β2 and F3Y356-β2, we were able to obtain ∼1.2 Y122•/β2 with good protein recoveries (80 to 95 %). The UV-vis spectrum, EPR spectrum, and SDS PAGE of these proteins are shown in Figs. S1 and S2. The spectra are identical to those of recombinant wt-β2 indicating an intact diferric-Y122• cofactor. Assays for dCDP production before and after application of this procedure, gave specific activities that correlated with Y122• content. Thus, the procedure increased the radical content of F3Y-β2 and elevated nucleotide reduction activity proportionally.

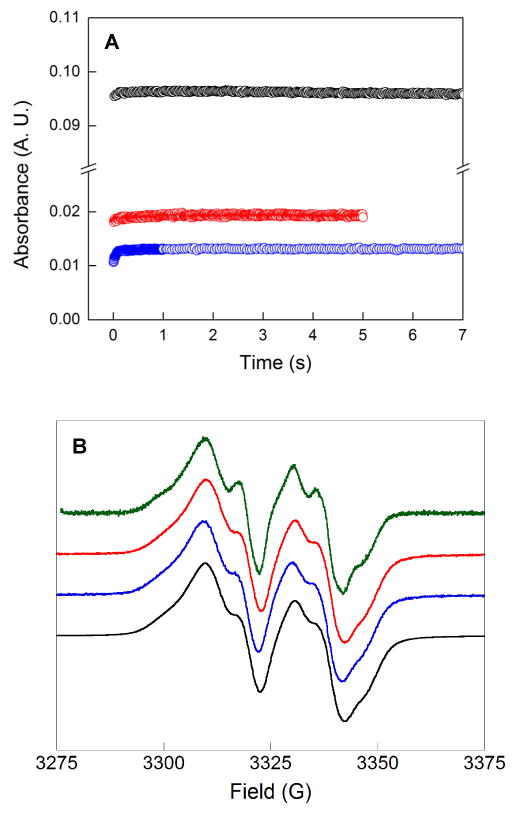

SF Absorption and RFQ EPR Spectroscopies with F3Y356-β2/α2

To test whether radical intermediates could be detected during the radical propagation process with F3Y356-β2 at pH 8.4, where this process is proposed to be rate-limiting, SF absorption and RFQ EPR studies were carried out with wt α2. Using the Eps measured for the blocked amino acids, W, F3Y, Y and NH2Y (Fig. 1C), an energy landscape for the pathway (Fig. 1D) was created to help visualize how insertion of F3Y into the pathway and pH might alter the ability of adjacent residues in the pathway to mediate its oxidation. If forward radical transfer is slow at pH 8.4 for example, then a neutral W48 could build up, if it is not rapidly reduced by Y122. W•s have reported λmaxs from 485–530 nm (ε = 1750–2300 M-1cm-1). We also considered the possibility that WH•+ might be observed and they have reported λmaxs between 560–600 (ε = 2500–2900 M-1cm-1) (34, 37). If reverse radical transfer is slow, then the species most likely to build up at pH 8.4 is the Y731•, based on Ep difference of 110 mV relative to F3Y (Figs. 1C & 1D). Y•s have λmaxs in the range of 407–410 (ε = 2750–3200 M-1cm-1) (38, 39). The results from SF absorption experiments are presented in Fig. 2A. They show that no changes are observed at 410 nm (λmax for Y122•), 510 nm or 560 nm. The minor changes that are observed are likely related to small structural perturbations associated with the di-iron cluster upon binding to α2 (20). SF diode array absorption spectroscopy also failed to reveal any changes in the region of 400-800 nm (data not shown). Under these experimental conditions, no absorption features associated with a W• or WH•+ were apparent.

Figure 2.

SF absorption and RFQ EPR spectroscopies with F3Y356-β2 in the presence of α2 and CDP/ATP at pH 8.4. (A) Single λ SF time courses monitored at 410 nm (black), 510 nm (red) and 560 nm (blue). (B) RFQ EPR spectra of samples quenched at 72 ms (black), 138 ms (blue) and 1.9 s (red) with the EPR spectrum recorded at 77 K. The EPR spectrum of the 1.9 s quench time point was collected at 15 K (green).

As mentioned above, the absorption features associated with the Y• range from 407–410 nm with varying degrees of sharpness. The Y122• and Y731• features are thus likely to be similar, making build up of a transient Y731• difficult to distinguish from Y122• by vis spectroscopy. The EPR features of Y122• and Y731•, on the other hand, are highly dependent on the dihedral angle of the β protons relative to the aromatic ring (40, 41). Based on the crystal structures of α2 and β2, Y122, Y731 and Y730 have dihedral angles of ∼90°, 33° and 37°, respectively (13), making it feasible that the EPR spectra of the latter two would be distinct from that of Y122• (42). In accord with the structural data, we recently determined a dihedral angle of 46° for NH2Y730• by EPR analysis (43). Consequently, RFQ-EPR studies were carried out under conditions similar to those in the SF absorption experiments to look for a new Y•. The reaction was quenched from 28 to 1912 ms. The traces obtained at 72, 138 and 1912 ms are shown in Fig. 2B and those at 28 and 612 ms in Fig. S3. EPR analysis and spin quantitation at 77 K or 15 K at all time points showed that the [Y•] observed is identical to the [Y122•] at time zero. The SF absorption and RFQ EPR spectroscopy experiments have thus failed to reveal formation of any pathway radical intermediates. We estimate that the lower limit of detection of W•s by SF spectroscopy would be 1 μM, ∼3 % of the amount of protein. The lower limit for Y• detection by EPR methods is 1.5–3 μM and is estimated to be 5–10 % of the protein. A rationalization for the lack of build-up of intermediates is presented below.

Use of NH2Y-α2 as a Reporter of Forward Radical Transfer with F3Y356-β2

Our previous SF studies at pH 7.6 with β2, Y731NH2Y-α2 (or Y730NH2Y-α2), CDP/ATP revealed that NH2Y• is formed with biphasic kinetics and rate constants of 18 s−1 and 2.5 s−1 (12 s−1 and 2.5 s−1) (19). The faster rate constants were proposed to be associated with electron delocalization within the protein in a non-productive conformation for nucleotide reduction, with NH2Y• formation resulting due to the ease of its oxidation. The slower rate constants were proposed to be associated with the rate limiting conformational change responsible for dNDP production under steady state conditions. NH2Y• formation was “complete” within 20 s and its concentration remained unchanged for several minutes. The decay of NH2Y• is slow with a rate constant of 0.0062 ± 0.0012 for NH2Y731• (Fig. S4) and 0.0043 ± 0.0011 s-1 for NH2Y730• (Fig. S5). Finally both 730 and 731 NH2Y mutants supported dCDP formation with rate constants of 0.3–0.6 s-1, substantially lower than the rate constant of NH2Y• production (Minnihan, Seyedsayamdost & Stubbe, manuscript in preparation). These rate constants would be further reduced with F3Y356-β2, as intein wt-β2 has 25 % the activity of wt-β2. These observations together suggest that under the conditions of the SF experiments described subsequently, NH2Y can function as a radical trap reporting on the rate constant for forward radical propagation.

SF Absorption Spectroscopy with F3Y356-β2/NH2Y-α2/CDP/ATP

SF experiments were thus carried out with F3Y356-β2 and NH2Y730-α2 or NH2Y731-α2. The final concentration of protein in these experiments was 4 μM, similar to those previously reported in the steady state pH rate profile studies (3 μM) (36). The ability to generate 1.2 Y122• per Y356F3Y-β2, greatly facilitated the analysis.

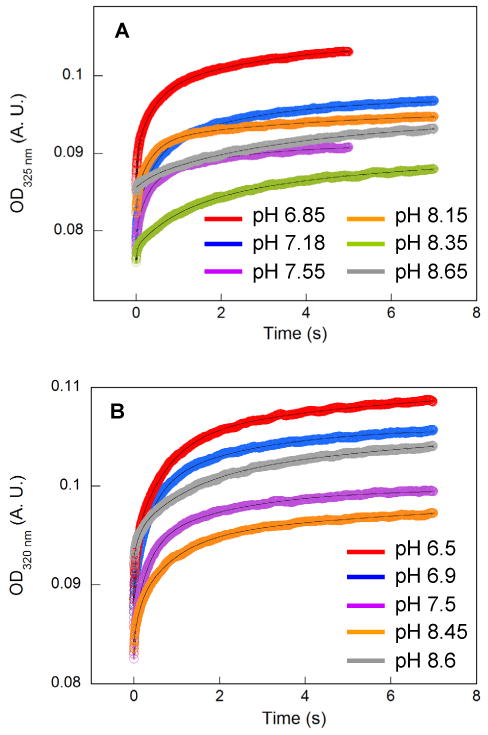

The results of the pH-dependent SF experiments with NH2Y730-α2 (or NH2Y731-α2) and F3Y356-β2 are shown in Fig. 3. Expanded views of the first several seconds of each trace are shown in Fig. S6 (for Y731NH2Y-α2) and Fig. S7 (for Y730NH2Y-α2). Reactions monitored for 20 s at pH 6.5, 8.45 and 8.6 (for Y731NH2Y-α2) and at 8.65 (for Y730NH2Y-α2) are shown in Fig. S8. The kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

SF absorption spectroscopy of NH2Y-α2s/F3Y356-β2/CDP/ATP as a function of pH. Reaction of F3Y356-β2 with NH2Y730-α2 (A) or NH2Y731-α2 (B). Each trace is an average of 6–8 traces. Black lines describe tri-exponential fits to the data. See Table 1 for kinetic parameters.

Table 1.

Summary of the kinetic parameters for NH2Y• formation in the reaction of NH2Y730-α2 or NH2Y731-α2 with F3Y356-β2 and CDP/ATP.

| 1st Phase | 2nd Phase | 3rd Phase | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | kobs (s−1) a | Amp b (% Y122•) |

kobs (s−1) a | Amp b (% Y122•) |

kobs (s−1) a | Amp b (% Y122•) |

| NH2Y730-α2 | ||||||

| 6.85 | 30.8 ± 3.7 | 10 ± 1 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 15 ± 2 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 13 ± 2 |

| 7.18 | 41.7 ± 5.0 | 7 ± 1 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 16 ± 2 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 15 ± 2 |

| 7.55 | 48.9 ± 5.9 | 6 ± 1 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 12 ± 1 | 0.52 ± 0.06 | 10 ± 1 |

| 8.15 | 21.8 ± 2.6 | 5 ± 1 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 13 ± 2 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 8 ± 1 |

| 8.35 | 32.9 ± 3.9 | 3 ± 1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 10 ± 1 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 14 ± 2 |

| 8.65 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2±1 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 9 ± 1 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 9 ± 2 |

| NH2Y730-α2 | ||||||

| 6.5 | 24.7 ± 3.0 | 11 ± 1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 20 ± 2 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 13 ± 2 |

| 6.9 | 26.2 ± 3.1 | 6 ± 1 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 18 ± 2 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 12 ± 1 |

| 7.5 | 28.6 ± 3.4 | 6 ± 1 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 17 ± 2 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 11 ± 1 |

| 8.45 | 7.8 ± 1.0 | 6 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 14 ± 2 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 9 ± 1 |

| 8.6 | 8.3 ± 1.0 | 5 ± 1 | 0.80 ± 0.1 | 12 ± 1 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 13 ± 2 |

| 9.2 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

Estimated errors based on systematic factors.

The amount of NH2Y• trapped has been reported as a % of total initial Y122•, which in these experiments was 4.8 μM.

Fits to the kinetic traces in all cases required three exponentials. These results contrast to those with wt-β2/NH2Y-α2, which generate a NH2Y• with all substrate/effector pairs in two kinetic phases. The molecular basis for the different phases is not understood, but our interpretation is that the slowest kinetic phase is associated with dCDP formation as observed in the steady state pH rate profile studies with F3Y356-β2/α2 and CDP/ATP (18). The second, kinetic phase may be associated with the mutations (V353G and S354C) that, as noted above, are required for efficient semisynthesis of β2. We propose that these two residues are likely located at the α2/β2 interface generating an additional conformation that binds to α2 and results in NH2Y• formation. We propose that the fastest phase is associated with non-productive conformational changes, as noted above. Three kinetic phases have previously been observed when fitting the data associated with 3-hydroxytyrosine radical (DOPA•) formation from DOPA-β2/α2/CDP/ATP, also made by the EPL method (17). The analysis of these pH profiles presented below focuses mainly on the slowest, third kinetic phase, as it corresponds to dCDP production in the steady state.

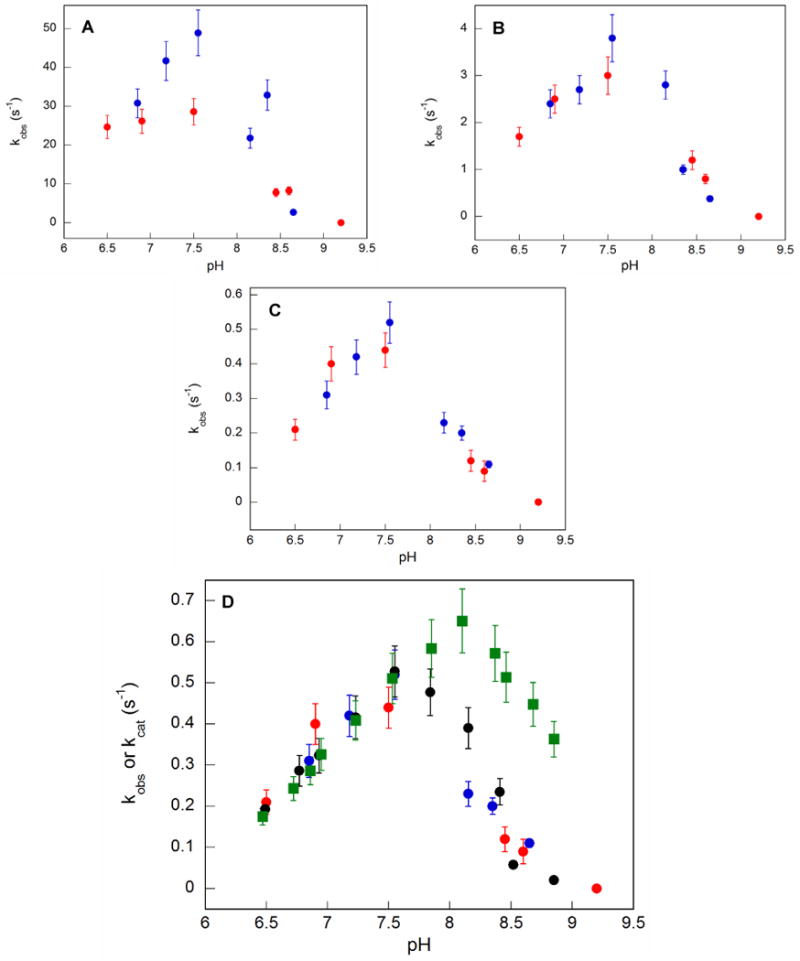

Analysis of the pH rate profile for NH2Y• formation with F3Y356-β2/NH2Y-α2

The pH dependence of wt RNR activity is not understood, but is associated with conformational changes and not chemistry. In the current case, pH is used to modulate the driving force for radical transfer (Figs. 1C & 1D) based on our previously observed correlation between the rate of dNDP formation and the Ep difference between F3Y and Y between pH 7.8 and 8.7. To analyze the results in Fig. 3, the rate constants for NH2Y• formation were plotted as a function of pH for each kinetic phase (Figs. 4A–4C).

Figure 4.

pH rate profiles for NH2Y• formation in the reactions of NH2Y730-α2 (blue dots) or NH2Y731-α2 (red dots) with F3Y356-β2 in the presence of CDP/ATP. pH dependence of the rate constants from the 1st (A), 2nd (B) and 3rd (C) kinetic phases determined from the tri-exponential fits (Table 1). In (D), the data from panel (C) are overlaid with the pH rate profiles for [14C]-dCDP formation with F3Y356-β2/wt α2 (black dots) and with intein wt-β2/wt α2 (green squares), determined in a previous study (18).

The data from the fastest phase with NH2Y730-α2 (Fig. 4A, blue dots) and NH2Y731-α2 (Fig. 4A, red dots) exhibited kobss that vary from 2.7–48.9 s-1 and from 7.8–26.2 s−1, respectively. The amplitudes in this phase account for the smallest amount, 10–26 %, of the total NH2Y•. Furthermore, unlike the other phases, the profile for NH2Y731-α2 is distinct from NH2Y730-α2 (Figs. 4A and S9). The second kinetic phase exhibits rate constants from 0.38–3.8 s−1 (0.80–3.0 s−1) with amplitudes of 37–50 % of the total absorbance change (Fig. 4B, blue dots and red dots), while the kobss for the third kinetic phase vary from 0.11–0.52 s−1 (0.09–0.42 s−1) with amplitudes of 27–52 % of the overall change (Fig. 4C, blue dots and red dots). The profiles of the two slow kinetic phases have shapes very similar to that observed for dCDP formation with F3Y-β2.

Our hypothesis is that the slowest kinetic phase is associated with the RNR conformation active in turnover. To analyze this phase further, the rate constants for NH2Y• formation with both 730 and 731 mutants were overlaid with those for dCDP formation in the steady state (Fig. 4D). Also included is the profile for dCDP formation with intein wt-β2 (green squares). A direct comparison between the rate constants for pre-steady state NH2Y• formation and steady state dCDP formation (by F3Y356-β2/α2) as a function of pH shows remarkable agreement. They overlap in all three activity regimes and are distinct from that of intein wt-β2 at pH > 7.8 (Fig. 4D, green squares). Because NH2Y• formation serves as a read-out for forward radical transfer, the results indicate that a step in this process has the same pH-dependent rate constants as kcat measured by steady state kinetic assays. This observation supports our original proposal that at high pH, the rate-determining step has shifted from a physical step to radical transfer and suggests that insertion of F3Y results in a decrease in the rate constant for forward radical transfer as the reaction pH is increased.

Discussion

Kinetic Simulations

To address our inability to detect radical intermediates with F3Y356-β2, despite an apparent shift in the rate-determining step, kinetic simulation studies have been carried out. Fig. 1D will be used as a means to predict the potential build-up of intermediates associated with F3Y insertion into the pathway. This energy landscape model of the pathway assumes that the reduction potentials and pKas of the residues involved are minimally perturbed by the protein environment. For residues Y356 in β2 and Y730 and Y731 in α2, these assumptions are supported by our recent studies in which 3-nitrotyrosine (NO2Y) has been site specifically incorporated into each of these positions (44, 45). The model suggests that during forward PCET, the step most likely to be rate-limiting at pH 8.4 would be the oxidation of F3Y by the W48• based on Eps of 0.85 V and 0.8 V, respectively, (Figs. 1C & 1D). In the reverse direction at pH 8.4, the slowest step would be the oxidation of F3Y by Y731• consistent with Eps of 0.85 V and 0.74 V, respectively (Figs. 1C & 1D).

The kinetic model in Fig. 5 is based on our previous kinetic model for wt RNR at pH 7.6 and the data and simulations reported herein (Fig. 5) (36). Two points should be reiterated prior to presentation of the model in detail. The first is that intein-wt β2 has 25 % the activity of wt-β2 due to the two additional mutations. Thus, the rate constants associated with the conformational change(s) used in the model could be elevated 4-fold for the wt RNR. The second is that while W48 has been incorporated into the original pathway model (13) and all subsequent renditions of this model (15, 24, 46), there is currently no direct evidence for its involvement in contrast with the proposed Y pathway residues. While in our model we have incorporated this residue, we and others are actively trying to address its involvement using multiple methods (45, 46).

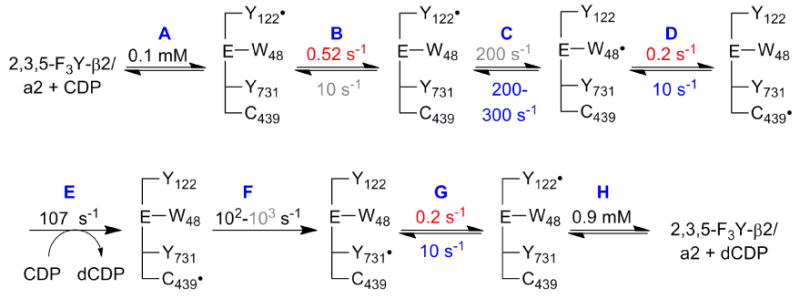

Figure 5.

Kinetic model for the catalytic cycle of F3Y356-β2 with wt α2 and CDP/ATP, which have been omitted for clarity. The Kds and the rate constants in black have been measured experimentally (45, 47, 48), the rate constants in grey have been adapted from our previous simulations (36) and those in red have been measured herein and assigned to steps B, D, and G as described in the text. Rate constants in blue have been simulated herein. When assuming rate-limiting reverse PCET, step D and the intermediate prior to D were eliminated from the model, and the kobs of 0.2 s-1 was assigned to step G. When assuming a rate-limiting forward PCET, step G and the intermediate prior to G were eliminated from the model and the kobs of 0.2 s-1 was assigned to step D. The krev in steps C, D and G have been assigned 200-300 s−1, 10 s−1 and 10 s−1, respectively, to reproduce the lack of observable intermediates (i.e. W48•).

In the model in Fig. 5, binding of CDP and effector ATP, step A, is followed by the rate-limiting conformational change, step B, that gates radical transfer. Subsequent to this change, Y122• is reduced and gives rise to a W48•, step C, which then generates a C439• via F3Y356, Y731 and Y730 transient radical intermediates, step D. One hopping step within step D, oxidation of F3Y by W48•, is proposed to be the rate-limiting step in the forward direction. C439• catalyzes nucleotide reduction, step E, which then gives rise to Y731• through a transient Y730• intermediate, step F. Y731• then regenerates Y122• via F3Y356 and W48, step G; this step could represent the rate-limiting step in reverse radical transfer. Dissociation of dCDP, step H, completes the catalytic cycle, although in the steady state the active site disulfide needs to be re-reduced for multiple turnovers to occur. In this model, the Kds and rate constants in black (steps A, E, F and H) have been determined experimentally (45, 47, 48). A rate constant of 107 s-1 for dCDP formation, step E, and 100 s-1 for Y356• formation, step F, have been recently determined in studies using NO2Y site-specifically incorporated in place of Y122 (NO2Y122-β2) (45). This protein does not have the additional mutations of the EPL-generated protein. A NO2Y• is transiently generated at position 122, that uncouples proton and electron transfer and unmasks for the first time, the rate constant of dCDP formation and for Y356• formation in the reverse direction. The rate constants in grey (steps C, F and krev in step B) were used in our original kinetic model for wt-RNR (pH 7.6) to reproduce our inability to observe disappearance and reappearance of Y122• or to detect any radical intermediates under a wide range of conditions (36). The rate constants in red (kfwd in steps B, D, and G) have been determined experimentally herein and assigned to these steps as described subsequently. Note that the rate constant associated with step B (0.5 s-1) might be elevated 4-fold as described above. The rate constants in blue have been simulated herein.

We began this exercise by simulating the effect of a solely rate-limiting reverse radical transfer. In this case, step D and the intermediate preceding it were eliminated from the model, and we assigned to step G the kobs of 0.2 s-1, obtained at pH 8.4 by SF absorption spectroscopy for NH2Y• formation (see Table 1). This assignment is consistent with Ep differences between F3Y and Y at pH 8.4 described above (25). The simulations show that with 20 μM RNR, Y731• would build up to > 12.5–14 μM. The RFQ-EPR studies, however, failed to detect any new Y•. Changing the parameters for step C (100–300 s−1 for krev) or step G (1-100 s-1 for krev) still yielded >12 μM of Y731•. Thus, within the current kinetic framework, and the caveat that the Y• would have detectable hyperfine by EPR spectroscopy (42), reverse radical transfer is not solely rate-limiting, consistent with our SF absorption studies where NH2Y-α2 served as a reporter for forward radical transfer.

We next assumed a solely rate-limiting forward radical transfer. In this case, step G and the intermediate preceding it were eliminated from the model (Fig. 5) and the slow step of 0.2 s-1 at pH 8.4 (see Table 1) was applied to step D, consistent with Ep difference between W and F3Y (Figs. 1C & 1D). The kinetic simulations show at 20 μM RNR, that W48• accumulates to 0.5–1.4 μM (using 102–103 s-1 for step F and 300 s-1 for krev of step C). As discussed above, these concentrations are at or below our lower limit of detection. In addition, given the half-sites reactivity for RNRs that we have observed in many of our experiments (17, 19), the actual concentration of the radical would be even lower (0.25–0.7 μM). The krev for step C had to be increased to ≥ 300 s-1 relative to our original kinetic model for RNR (200 s-1) in order to reproduce our inability to detect intermediates. This suggests an increased flux toward Y122• reformation when F3Y356 replaces Y356• The faster the krev for steps B or C, the lower the amount of W48• that would build up. This simulation makes it much less likely that a W48H•+ is involved during forward PCET (Figs. 1C & 1D, see below).

Finally, we assumed that forward and reverse radical transfers are both partially rate-limiting and assign steps D and G both to 0.2 s-1. In this case, the simulations show that Y731• and W48• would build up to <0.8 μM and 0.25–0.7 μM (after accounting for half-sites reactivity), respectively. Thus, within the framework of the current model, rate-limiting forward or partially rate-limiting forward and reverse PCET are consistent with the inability to observe intermediates despite an apparent change in rate-limiting radical transfer as a result of F3Y insertion into the pathway. This model serves as a starting point for examining the kinetics of F3Y356-β2 further, for example by using rapid chemical quench methodology to examine the rate of dCDP formation. The two models make different predictions about the lag phases in dCDP production. Evolution of a tRNA/tRNA synthetase pair for incorporation of F3Y is in progress. These studies should remove the kinetic complexity associated with the two additional mutations required by EPL method, increase the overall activity 4 fold and make further analysis simpler.

Implications for Radical Propagation

Despite the shift in the rate-determining step associated with the redox properties of F3Y relative to W48 or Y731 (Figs. 1C & 1D), no pathway intermediates are detectable. A modeling exercise incorporating recent kinetic parameters from studies with Y122 replaced with NO2Y, provides insight as to why this might be the case, and if W48 is on the pathway, as to why a W• and not a WH•+ is the most likely intermediate between Y122 and residue 356. We consider the WH•+ less likely given the following argument. If we assume the pKa of F3Y is minimally perturbed (44) and that a WH•+ participates in the pathway, the Ep difference between WH•+ and F3Y would not change between pH 7 and 8.4 (Fig. 1C). Our data indicates that the rate-determining step occurs between Y122• reduction and NH2Y oxidation. Therefore, the rate-limiting step would be associated with oxidation of W48 by Y122• (oxidation of F3Y by WH•+ is pH-independent and that of Y731 by F3Y• is thermodynamically favored, Fig. 1D). This conclusion is inconsistent with the observation that when FnYs are placed in position 356, their pH rate profiles differ from intein wt-β2. They would be the same if Y122•-mediated W oxidation was slow. It is also inconsistent with the >200 mV Ep difference (Fig. 1D, Y122 is special and appears to be a thermodynamic hole) at pH 7 and a >310 mV difference at pH 8.4 between Y122 and WH•+. With W48• as an intermediate, on the other hand, an explanation for the change in rate-determining step when F3Y is inserted into the pathway becomes apparent. In the case of the neutral W•, the Ep gap between Y122 and W48 does not change as a function of pH, F3Y•-mediated oxidation of Y or NH2Y is thermodynamically very favorable (Fig. 1D), and thus oxidation of F3Y by W48• remains as the basis for the observed changes. Between pH 7 and 8.4 (Fig. 1C) the reaction becomes less favorable by 70 mV.

While our previous studies have demonstrated the importance of a WH•+ in active metallo-cofactor assemble and more specifically Y122 oxidation (49, 50), in this case the reaction is irreversible, in contrast to the reversible PCET pathway (Fig. 1), and the “hot” Fe4+/Fe3+ oxidant could drive the reaction toward the Y•. These studies and our other studies suggest that Nature has chosen W and Y as reversible redox conduits over long distances as their reduction potentials require minimal perturbation. W and Y contrast to many metal or organic cofactors (flavins, hemes) used by enzymes in which the protein environment must modulate the reduction potentials by >500 mV for the cofactor to function (51, 52). W and Y have the appropriate chemical properties for fine-tuning the unusual radical propagation pathway in RNR.

The kinetic modeling provides a framework to think about optimal unnatural amino acids to perturb the pathway to detect intermediates and to study the PCET process at each step. For example, the model suggests that to detect intermediates in the pathway, a hot oxidant needs to replace the Y122•. Rapid reduction of the hot oxidant would lead to rapid production of pathway intermediates that would be unable to reoxidize the reduced form of the oxidant, allowing build up an intermediate(s). This approach has recently been shown to be successful by placing NO2Y at position 122 that can be oxidized by the Fe4+/Fe3+ radical, but cannot be reoxidized by pathway radicals (45). The studies further suggest that NH2Y substitution will be useful in examining the individual hopping steps of the three transiently involved Y•s in the pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ellen C. Minnhan for helpful discussions and the NIH (Grant 29595 to J.S.) for support of this work. M.R.S. is a Novartis Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation.

Abbreviations

- α

ribonucleotide reductase large subunit

- ATP

adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- β

ribonucleotide reductase small subunit

- C•

thiyl radical

- CDP

cytidine-5′-diphosphate

- DOPA

3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (or 3-hydroxytyrosine)

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

- EPL

expressed protein ligation

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- ET

electron transfer

- F3Y

2,3,5-trifluorotyrosine

- intein wt-β2

V353G/S354C-β2 generated by EPL

- kfwd

forward rate constant

- kobs

observed rate constant

- krev

reverse rate constant

- NDP

nucleoside 5′-diphosphate

- NH2Y

3-aminotyrosine

- NH2Y•

3-aminotyrosyl radical

- PCET

proton-coupled electron transfer

- RFQ

rapid freeze quench

- RNR

ribonucleotide reductase

- SF

stopped-flow

- TR

thioredoxin

- TRR

thioredoxin reductase

- W•

tryptophan radical

- wt

wild-type

- Y•

tyrosyl radical

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: SDS-PAGE, UV-vis and EPR characterization of the diferric Y122• cluster in semi-synthetic F3Y356-β2 after increasing its radical content (Figs. S1 & S2), RFQ EPR traces of additional time points in the reaction of F3Y356-β2 with wt α2 and CDP/ATP (Fig. S3), stability of NH2Y731• and NH2Y730• monitored by UV-vis and EPR spectroscopies (Figs. S4 & S5), magnified views of SF UV-vis traces in the reaction of F3Y356-β2 with NH2Y731-α2 or NH2Y730-α2 (Figs. S6–S8), comparison of the pH profiles of fast kobss for NH2Y• formation (Fig. S9). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Stubbe J, van der Donk WA. Protein radicals in enzyme catalysis. Chem Rev. 1998;98:705–762. doi: 10.1021/cr9400875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan A, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:71–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown NC, Reichard P. Ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase. Formation of active and inactive complexes of proteins B1 and B2. J Mol Biol. 1969;46:25–38. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thelander L. Physicochemical characterization of ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:4591–4601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Lohman GJ, Stubbe J. Enhanced subunit interactions with gemcitabine-5′-diphosphate inhibit ribonucleotide reductases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14324–14329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706803104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stubbe J. Ribonucleotide reductases: amazing and confusing. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5329–5332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stubbe J. Ribonucleotide reductases in the twenty-first century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2723–2724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Licht S, Gerfen GG, Stubbe J. Thiyl radicals in ribonucleotide reductases. Science. 1996;271:477–481. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:681–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehrenberg A, Reichard P. Electron spin resonance of the iron-containing protein B2 from ribonucleotide reductase. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:3485–3488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sjöberg BM, Reichard P, Gräslund A, Ehrenberg A. The tyrosine free radical in ribonucleotide reductase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:6863–6865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stubbe J, Nocera DG, Yee CS, Chang MCY. Radical initiation in the class I ribonucleotide reductase: long-range proton-coupled electron transfer? Chem Rev. 2003;103:2167–2201. doi: 10.1021/cr020421u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uhlin U, Eklund H. Structure of ribonucleotide reductase protein R1. Nature. 1994;370:533–539. doi: 10.1038/370533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Climent I, Sjöberg BM, Huang CY. Site-directed mutagenesis and deletion of the carboxyl terminus of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase protein R2. Effects on catalytic activity and subunit interaction. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4801–4807. doi: 10.1021/bi00135a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekberg M, Sahlin M, Eriksson M, Sjöberg BM. Two conserved tyrosine residues in protein R1 participate in an intermolecular electron transfer in ribonucleotide reductase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20655–20659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekberg M, Birgander P, Sjöberg BM. In vivo assay for low-activity mutant forms of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1167–1173. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1167-1173.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J. Site-specific replacement of Y356 with 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine in the β2 subunit of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2522–2523. doi: 10.1021/ja057776q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seyedsayamdost MR, Yee CS, Reece SY, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. pH rate profiles of FnY356-R2s (n = 2, 3, 4) in Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase: evidence that Y356 is a redox-active amino acid along the radical propagation pathway. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1562–1568. doi: 10.1021/ja055927j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seyedsayamdost MR, Xie J, Chan CT, Schultz PG, Stubbe J. Replacement of Y730 and Y731 in the alpha2 subunit of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase with 3-aminotyrosine using an evolved suppressor tRNA/tRNA-synthetase pair. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15060–15071. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minnihan EC, Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J. Use of 3-aminotyrosine to examine the pathway dependence of radical propagation in Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:12125–12132. doi: 10.1021/bi901439w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seyedsayamdost MR, Chan CT, Mugnaini V, Stubbe J, Bennati M. PELDOR spectroscopy with DOPA-β2 and NH2Y-α2s: distance measurements between residues involved in the radical propagation pathway of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15748–15749. doi: 10.1021/ja076459b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tommos C, Skalicky JJ, Pilloud DL, Wand AJ, Dutton PL. De novo proteins as models of radical enzymes. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9495–9507. doi: 10.1021/bi990609g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reece SY, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. pH Dependence of charge transfer between tryptophan and tyrosine in dipeptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1706:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reece SY, Hodgkiss JM, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Proton-coupled electron transfer: the mechanistic underpinning for radical transport and catalysis in biology. Philos Trans R Soc London, Ser B. 2006;361:1351–1364. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seyedsayamdost MR, Reece SY, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted fluorotyrosines: new probes for enzymes that use tyrosyl radicals in catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1569–1579. doi: 10.1021/ja055926r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reece SY, Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Electron transfer reactions of fluorotyrosyl radicals. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13654–13655. doi: 10.1021/ja0636688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeFelippis MR, Murthy CP, Broitman F, Weinraub D, Faraggi M, Klapper MH. Electrochemical properties of tyrosine phenoxy and tryptophan indolyl radicals in peptides and amino acid analogs. J Phys Chem. 1991;95:3416–3419. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salowe S, Bollinger JM, Jr, Ator M, Stubbe J. Alternative model for mechanism-based inhibition of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase by 2′-azido-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-diphosphate. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12749–12760. doi: 10.1021/bi00210a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chivers PT, Prehoda KE, Volkman BF, Kim BM, Markley JL, Raines RT. Microscopic pKa values of Escherichia coli thioredoxin. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14985–14991. doi: 10.1021/bi970071j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russel M, Model P. Direct cloning of the trxB gene that encodes thioredoxin reductase. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:238–242. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.238-242.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yee CS, Seyedsayamdost MR, Chang MCY, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Generation of the R2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase by intein chemistry: insertion of 3-nitrotyrosine at residue 356 as a probe of the radical initiation process. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14541–14552. doi: 10.1021/bi0352365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atkin CL, Thelander L, Reichard P, Lang G. Iron and free radical in ribonucleotide reductase. Exchange of iron and Mossbauer spectroscopy of the protein B2 subunit of the Escherichia coli enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:7464–7472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bollinger JM, Jr, Tong WH, Ravi N, Huynh BH, Edmondson DE, Stubbe J. Use of rapid kinetics methods to study the assembly of the diferric-tyrosyl radical cofactor of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. Methods Enzymol. 1995;258:278–303. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)58052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aubert C, Vos MH, Mathis P, Eker AP, Brettel K. Intraprotein radical transfer during photoactivation of DNA photolyase. Nature. 2000;405:586–590. doi: 10.1038/35014644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ballou DP. Freeze-quench and chemical-quench techniques. Methods Enzymol. 1978;54:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)54010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ge J, Yu G, Ator MA, Stubbe J. Pre-steady-state and steady-state kinetic analysis of E. coli class I ribonucleotide reductase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10071–10083. doi: 10.1021/bi034374r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baugher JF, Grossweiner LI. Photolysis mechanism of aqueous tryptophan. J Phys Chem. 1977;81:1349–1354. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feitelson J, Hayon E. Electron ejection and electron capture by phenolic compounds. J Phys Chem. 1973;77:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bansal KM, Fessenden RW. Pulse radiolysis studies of the oxidation of phenols by •SO4− and Br2− in aqueous solutions. Radiat Res. 1976;67:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pesavento RP, van der Donk WA. Tyrosyl radical cofactors. Adv Prot Chem. 2001;58:317–385. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)58008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lendzian F. Structure and interactions of amino acid radicals in class I ribonucleotide reductase studied by ENDOR and high-field EPR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1707:67–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svistunenko DA, Cooper CE. A new method of identifying the site of tyrosyl radicals in proteins. Biochem J. 2004;87:582–595. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.041046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seyedsayamdost MR, Argirevic T, Minnihan EC, Stubbe J, Bennati M. Structural examination of the transient 3-aminotyrosyl radical on the PCET pathway of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase by multifrequency EPR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15729–15738. doi: 10.1021/ja903879w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yokoyama K, Uhlin U, Stubbe J. Site-specific incorporation of 3-nitrotyrosine as a probe of pKa perturbation of redox-active tyrosines in ribonucleotide reductase. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8385–8397. doi: 10.1021/ja101097p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokoyama K, Uhlin U, Stubbe J. A hot oxidant, 3-NO2Y122 radical, unmasks conformational gating in ribonucleotide reductase. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15368–15379. doi: 10.1021/ja1069344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang W, Xie J, Varano PT, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr Two distinct mechanisms of inactivation of the class Ic ribonucleotide reductase from Chlamydia trachomatis by hydroxyurea: implications for the protein gating of intersubunit electron transfer. Biochemistry. 49:5340–5349. doi: 10.1021/bi100037b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Döbeln U, Reichard P. Binding of substrates to Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. J Biol Chem. 1976;253:3616–3622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allard P, Kuprin S, Shen B, Ehrenberg A. Binding of the competitive inhibitor dCDP to ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase from Escherichia coli studied by 1H NMR. Different properties of the large protein subunit and the holoenzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1992;280:635–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bollinger JM, Jr, Tong WH, Ravi N, Huynh BH, Edmondson DE, Stubbe J. Mechanism of assembly of the tyrosyl radical-diiron(III) cofactor of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. 3. kinetics of the limiting Fe2+ reaction by optical, EPR, and mossbauer spectroscopies. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:8024–8032. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baldwin J, Krebs C, Ley BA, Edmondson DE, Huynh BH, Bollinger JM., Jr Mechanism of rapid electron transfer during oxygen activation in the R2 subunit of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. 1. Evidence for a transient tryptophan radical. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:12195–12206. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solomon EI, Szilagyi RK, DeBeer George S, Basumallick L. Electronic structures of metal sites in proteins and models: contributions to function in blue copper proteins. Chem Rev. 2004;104:419–458. doi: 10.1021/cr0206317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walsh C, Fisher J, Spencer R, Graham DW, Ashton WT, Brown JE, Brown RD, Rogers EF. Chemical and enzymatic properties of riboflavin analogues. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1942–1951. doi: 10.1021/bi00603a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.