Abstract

Summary: State-of-the-art methods for topology of α-helical membrane proteins are based on the use of time-consuming multiple sequence alignments obtained from PSI-BLAST or other sources. Here, we examine if it is possible to use the consensus of topology prediction methods that are based on single sequences to obtain a similar accuracy as the more accurate multiple sequence-based methods. Here, we show that TOPCONS-single performs better than any of the other topology prediction methods tested here, but ∼6% worse than the best method that is utilizing multiple sequence alignments.

Availability and Implementation: TOPCONS-single is available as a web server from http://single.topcons.net/ and is also included for local installation from the web site. In addition, consensus-based topology predictions for the entire international protein index (IPI) is available from the web server and will be updated at regular intervals.

Contact: arne@bioinfo.se

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are avaliable at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today only 268 unique α-helical membrane protein structures are known according to the Orientation of Proteins in Membranes database (OPM, http://opm.phar.umich.edu/). The ‘topology’ of such proteins has proven to be a convenient concept. In essence, the topology specifies the number of transmembrane α-helices of the protein together with the location of the N-terminal end of the chain, i.e. whether it is in the cytosol (‘in’) or in the endoplamsatic reticulum (ER) lumen or extramembrane space (‘out’).

The TOPCONS algorithm (Bernsel et al., 2009) computes consensus predictions of membrane protein topology using a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) and input from several topology predictors. The original method is available as a web server (http://topcons.net/) and is based on five state-of-the-art topology prediction methods and typically takes a couple of minutes to run. The bulk of that time is spent running a PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) search against a sequence database to obtain evolutionary information that is then used by the underlying predictors. This approach is quite accurate, but woefully inappropriate when running predictions for many sequences, e.g. in studies of whole genomes.

2 DEVELOPMENT OF TOPCONS-SINGLE

Here, we have benchmarked the TOPCONS algorithm (Bernsel et al., 2009) using six different topology prediction methods that do not use any homology information, i.e. do not require BLAST to be run. Six individual methods were tested: SCAMPI-single (Bernsel et al., 2008) S-TMHMM (Viklund and Elofsson, 2004), HMMTOP (Tusnády and Simon, 2001), TopPred (von Heijne, 1992; Claros and Heijne, 1994), MEMSAT-1.0 (Jones et al., 1994) and PHOBIUS (Käll et al., 2004).

The methods were benchmarked using a modified version of the dataset used in SCAMPI (Bernsel et al., 2008). The original set consisted of two subsets stemming from the high-resolution structures (123 sequences) and from structures of lower resolution (146 sequences). This set was homology-reduced to 30% sequence identity using the method proposed and implemented by Holm and Sander (1998). The reduced set contain 101 sequences and was further divided into multi-spanning (79 sequences) and single-spanning (22 sequences) proteins resulting in three sets labeled ‘all’, ‘multi’ and ‘single’, respectively.

All possible combinations of three or more topology predictors were used as input to the TOPCONS algorithm and the results were evaluated. The best combination—the one scoring the highest accuracy over the dataset—is listed in Table 1. Accuracy is the proportion of correct predictions, and correct topology predictions are defined as by Krogh et al. (2001). All definitions and the full list of all method combinations are available in the Supplementary Material. To enable comparison, the performance of the original TOPCONS server based on homology information is listed, as well as the individual performance for the six single sequence methods.

Table 1.

The accuracy of different predictors on different datasets

| Topology predictor | Time (s) | All (101) (%) | Multi (79) (%) | Single (22) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCAMPI-single | 2 | 62 | 62 | 64 |

| HMMTOP | 10 | 57 | 53 | 73 |

| PHOBIUS | 26 | 52 | 56 | 41 |

| S-TMHMM | 10 | 51 | 53 | 45 |

| MEMSAT-1.0 | 18 | 56 | 54 | 64 |

| TOPPRED | 2 | 33 | 30 | 41 |

| TOPCONS-single | 64 | 73 | 68 | 91 |

| TOPCONS | 4483 | 79 | 77 | 86 |

Homology reduced to 30% sequence identity. The numbers in parenthesis denote the number of protein sequences in the set. ‘Time’ is the time it takes to process the set of 101 protein sequences.

The execution time for each run of TOPCONS-single was also measured. For the benchmark dataset, the time required from start to finish varied between 50 s (when using three methods) to 100 s (when using all six methods). For comparison, TOPCONS as implemented on http://topcons.net/ needed 4500 s and the fastest individual method, SCAMPI-single, finished in ∼2 s. Running the complete human genome (∼21000 sequences) through the TOPCONS-single pipeline took ∼60 min.

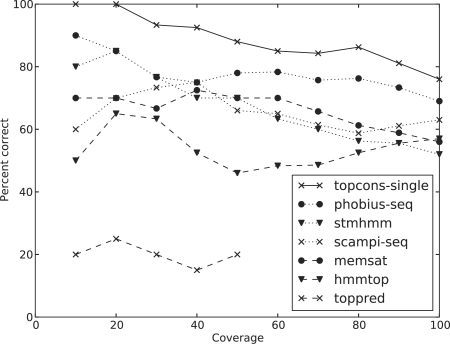

We have implemented a reliability score for TOPCONS-single as previously described (Bernsel et al., 2009) and also a reliability score for each individual method, as previously described (Melén et al., 2003). Definitions and descriptions of all reliability scores are listed in the Supplementary Material. We investigated the reliability scores by ranking the predictions by descending reliability score and plotting the fraction of correct predictions against the coverage in the ‘All’ benchmark dataset (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Coverage versus correct topology predictions for TOPCONS-single and each of the individual methods. The proteins in the test set (‘all’) are ordered according to the decreasing reliability score, and the percentage of correct predictions are calculated every 10% of coverage.

3 SUMMARY

We have constructed a consensus predictor for α-helical membrane proteins using the HMM-based TOPCONS algorithm with several fast single sequence-based prediction methods as input. After starting out with six predictors and benchmarking all possible combinations and subsets of them, we found that a combination of SCAMPI-single, HMMTOP, MEMSAT-1.0 and S-TMHMM yielded the best results. TOPCONS-single consistently outperforms each of its underlying single sequence predictors when they are used on their own, which confirms the notion of consensus prediction adding value. It does not use searches for homologous proteins and thus performs worse, but runs much faster than a corresponding approach using evolutionary information.

TOPCONS-single performs especially well on single-spanning membrane proteins in our dataset (Table 1) mainly by not over-predicting the number of transmembrane helices in the same extent as the single sequence methods (Supplementary Material).

A possible caveat to our approach is the use of benchmark sets where at least subsets have been previously used to train the underlying single sequence methods. We judge this to be less influential since the authors of said prediction methods have taken steps to avoid overtraining on their respective sets.

The best-performing version of TOPCONS-single, using four individual methods (Table 1), is available as an easy-to-use web-based prediction server at http://single.topcons.net/. It uses the globular protein filter of SCAMPI to weed out non-membrane proteins and then proceeds to run the rest of the predictors–HMMTOP, MEMSAT-1.0 and S-TMHMM—on the remaining set. The output consists of text files with well-defined formats for easy parsing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Dr. Håkan Viklund for writing the modhmm code used in TOPCONS.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (VR-NT 2009-5072, VR-M 2007-3065), SSF (the Foundation for Strategic Research), the EU 6'th Framework Program by support to the EMBRACE project (contract No: LSHG-CT-2004-512092) and the EU 7'th Framework Program by support to the EDICT project (contract No: FP7-HEALTH-F4-2007-201924).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul S.F., et al. Gapped blast and psi-blast: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernsel A., et al. Prediction of membrane-protein topology from first principles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7177–7181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711151105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernsel A., et al. Topcons: consensus prediction of membrane protein topology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W465–W468. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claros M.G., von Heijne G. TopPred II: an improved software for membrane protein structure predictions. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1994;10:685–686. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L., Sander C. Removing near-neighbour redundancy from large protein sequence collections. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:423–429. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.T., et al. A model recognition approach to the prediction of all-helical membrane protein structure and topology. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3038–3049. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käll L., et al. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A., et al. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melén K., et al. Reliability measures for membrane protein topology prediction algorithms. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;327:735–744. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusnády G.E., Simon I. The hmmtop transmembrane topology prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:849–850. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viklund H., Elofsson A. Best alpha-helical transmembrane protein topology predictions are achieved using hidden markov models and evolutionary information. Protein Science. 2004;13:1908–1917. doi: 10.1110/ps.04625404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. Membrane protein structure prediction. hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;225:487–494. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90934-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.