Abstract

Heterochromatin consists of highly ordered nucleosomes with characteristic histone modifications. There is evidence implicating chromatin remodeling proteins in heterochromatin formation, but their exact roles are not clear. We demonstrate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that the Fun30p and Isw1p chromatin remodeling factors are similarly required for transcriptional silencing at the HML locus, but they differentially contribute to the structure and stability of HML heterochromatin. In the absence of Fun30p, only a partially silenced structure is established at HML. Such a structure resembles fully silenced heterochromatin in histone modifications but differs markedly from both fully silenced and derepressed chromatin structures regarding nucleosome arrangement. This structure likely represents an intermediate state of heterochromatin that can be converted by Fun30p to the mature state. Moreover, Fun30p removal reduces the rate of de novo establishment of heterochromatin, suggesting that Fun30p assists the silencing machinery in forming heterochromatin. We also find evidence suggesting that Fun30p functions together with, or after, the action of the silencing machinery. On the other hand, Isw1p is dispensable for the formation of heterochromatin structure but is instead critically required for maintaining its stability. Therefore, chromatin remodeling proteins may rearrange nucleosomes during the formation of heterochromatin or serve to stabilize/maintain heterochromatin structure.

Keywords: Chromatin Remodeling, Chromatin Structure, DNA Topology, Nucleosome, Yeast, Heterochromatin, Transcriptional Silencing

Introduction

DNA in eukaryotes is packed into chromatin through the formation of nucleosomes. There are two structurally distinct types of chromatin that are interspersed in the genome. One is decondensed euchromatin that is permissive to gene transcription, and the other is condensed heterochromatin that silences the expression of genes embedded in it (1). Heterochromatin generally consists of regularly ordered nucleosomes with characteristic histone modifications that are thought to facilitate the folding of chromatin into high order structures (1–4). The structural and functional properties of heterochromatin have been extensively investigated in many model organisms. However, what makes nucleosomes adopt a highly ordered arrangement in heterochromatin has not been addressed (2). There is evidence implicating chromatin remodeling factors in heterochromatin formation, but their exact roles are not known (5–8).

Heterochromatin in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae exists at the HML3 and HMR loci as well as subtelomeric regions (9). Like its metazoan counterpart, yeast heterochromatin consists of highly ordered and stably positioned nucleosomes (10–12). It also bears characteristic histone modifications such as hypoacetylation and hypomethylation (9, 13, 14). The Sir complex composed of Sir2p, Sir3p, and Sir4p binds nucleosomes and serves as an integral part of yeast heterochromatin (9). Sir2p is an evolutionally conserved protein deacetylase that is responsible for the hypoacetylation of histones in heterochromatin (15). Establishment of heterochromatin is initiated via the recruitment of the Sir complex to silencers flanking the HM loci or telomeric repeats (9). A Sir complex recruited to a silencer or telomere deacetylates histones in adjacent nucleosomes (9, 15). The deacetylated nucleosome then binds additional Sir complexes, because Sir complex self-interacts and preferentially binds hypoacetylated histones (16–19). Through repeated cycles of histone deacetylation and Sir complex recruitment, Sir complexes propagate along the chromatin to form heterochromatin (9).

The high regularity of nucleosomes in heterochromatin may be achieved during chromatin replication when new nucleosomes are formed. Alternatively or in addition, preexisting nucleosomes may be repositioned by chromatin remodeling factors to form ordered arrays. None of the Sir proteins has chromatin remodeling activity. However, there is evidence for the involvement of three chromatin remodeling proteins Isw1p, Snf2p, and Fun30p in transcriptional silencing. Isw1p is required for HMR but not telomeric silencing, whereas Snf2p is required for telomeric but not HM silencing (20, 21). Fun30p, on the other hand, is required for silencing at both HMR and telomeric loci and is associated with heterochromatin (22). Whereas the chromatin remodeling activities of Isw1p and Snf2p have been long established, Fun30p has only recently been shown to possess histone H2A/H2B dimer exchange and nucleosome sliding activities (23). How any of these factors contributes to heterochromatin structure is not known.

In this report we examined the roles of Fun30p and Isw1p in heterochromatin at the HML locus. We found that although Fun30p and Isw1p are similarly required for efficient HML silencing, they differentially contribute to the structure and maintenance of HML heterochromatin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains

Yeast strains are listed in Table 1. Each strain is numbered according to the order of its first appearance. Replacement of a gene with the kanMX or natMX marker was achieved by transforming the parental strain to Geneticin- or nourseothricin-resistant with a PCR-generated fragment composed of kanMX or natMX bracketed by 5′- and 3′-flanking sequences of the coding region of the gene to be disrupted. Replacing a gene with the HIS3 or URA3 marker was achieved by transforming the parental strain to histidine or uracil prototrophy with a PCR-generated fragment composed of the HIS3 or URA3 gene bracketed by 5′- and 3′-flanking sequences of the coding region of the gene to be disrupted. Strain 16 was made by transforming strain VXB10s (12) to Geneticin-resistant with Tth111I-digested plasmid pUC-SK. pUC-SK was made by inserting the sir3-8 allele and kanMX cassette into pUC19.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains

| Number | Name | Relevant genotype | Reference/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | YXB61-1 | MATa ura3-52 ade2-1 lys1-1 leu2-3,112 his5-1 can1-100 sir3::LEU2 HML::URA3 TRP1-SIR3-SUP4-o | Ref. 24 |

| 1s | YXB61-1s | MATa ura3-52 ade2-1 lys1-1 leu2-3,112 his5-1 can1-100 sir3::LEU2 HML::URA3 | Ref. 24 |

| 2 | YQY691 | YXB61-1, fun30Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 3 | YQY684 | YXB61-1, isw1Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 4 | YQY709 | YXB61-1, fun30Δ::kanMX isw1Δ::natMX | This work |

| 5 | YXB6 | MATa ura3-52 ade2-1 lys1-1 his5-1 can1-100 [ciro] LEU2-GAL10-FLP1 E-FRT-hml::β2-FRT-I | Ref. 27 |

| 6 | YQY715 | YXB6, fun30Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 7 | YQY672 | YXB6, isw1Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 8 | YXZ90 | YXB6, fun30Δ::kanMX isw1Δ::URA3 | This work |

| 9 | YXB6s | YXB6, sir3::URA3 | Ref. 27 |

| 10 | CCFY101 | MATα ade2-1 can1-100 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-289 ura3-1 hmrΔe::TRP1 Tel VR-URA3 RDN1::ADE2-CAN1 | Ref. 26 |

| 11 | YQY540 | CCFY101, sir2Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 12 | YQY680 | CCFY101, fun30Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 13 | YQY674 | CCFY101, isw1Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 14 | YQY696 | CCFY101, isw1Δ::HIS3 fun30Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 15 | YQY707 | CCFY101, sir2Δ::HIS3 fun30Δ::kanMX | This work |

| 16 | YXB141 | YXB10s, sir3-8-kanMX | This work |

| 17 | YQY708 | YXB141, fun30Δ::natMX | This work |

| 18 | YQY717 | CCFY101, FUN30-Myc-kanMX | This work |

Analysis of DNA Topology

Cells were grown in YPR medium (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone and 2% raffinose) to log or stationary phase. Galactose (2%) was added to the culture that was further incubated for 2.5 h to induce the expression of PGAL10-FLP1. Nucleic acids were isolated using the glass bead method and fractionated on an agarose gel supplemented with 26 μg/ml chloroquine. After Southern blotting, the DNA circles were detected by an HML-specific probe. The profile of topoisomers from specific samples was obtained using the NIH image software.

Chromatin Mapping with Micrococcal Nuclease

Chromatin mapping was carried out as previously described (25). About 1 × 109 log phase cells were made into spheroplasts by zymolyase treatment. The spheroplasts were permeabilized with Nonidet P-40 as described (28). About 2 × 108 permeabilized spheroplasts were treated with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) at 120 or 160 units/ml at 37 °C for 5 min. The reaction was stopped by 0.5% SDS and 25 mm EDTA, and DNA was isolated. An aliquot of DNA was determined to contain fragments indicative of the presence of nucleosome ladders by gel electrophoresis. An aliquot of permeabilized spheroplasts not treated with MNase was used to isolate genome (naked) DNA that was digested with MNase at 7.5 units/ml. DNA from each sample was then digested with PvuII, EcoRI, or NgoMIV and run on a 1.0% agarose gel. Relevant fragments were visualized by hybridization with probe 1, 2, or 3 after Southern blotting.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP was carried out primarily as described (29). Briefly, cross-linked chromatin from 50 ml of mid-log phase cell culture was sonicated with Branson Sonifer 450 to yield DNA fragments of an average size of 500 bp. According to the A260, 120 units of whole-cell extract was used for immunoprecipitation with antibody against total histone H3 (C terminus, Abcam), H3 acetylated at lysines 9 and 14 (H3-K9,14-Ac, simplified as H3-Ac) (Upstate Biotechnology), H4-K5,8,12,16-Ac (H4-Ac) (Upstate Biotechnology), H3 trimethylated at K79 (H3-K79-Me) (Abcam), or Myc (Roche Applied Science). For semiquantitative PCR reactions, the proper amount of input or immunoprecipitated chromatin DNA to use was predetermined to be in the linear range by serial dilution analysis. PCR primers used are HML-1F (5′-GAAGTAGCTTTCGGATGGCA-3′) and HML-1R (CCCTTATCTACTTGCCTCTTTTGTT) for ChIP experiments with antibodies against histone H3, H3-Ac, H4-Ac, and H3-K79-Me, HML-2F (AAATCTTTCACTGCTCTTTTCTGTG) and HML-2R (CTCAGCTGGCATTAGAGAAATTTCG), and HMR-F (TCCCCGTCCAAGTTATGAGC) and HMR-R (TCGGAATCGAGAATCTTCGT) as well as ACT1-F (GATCCTTTCCTTCCCAATCTCTC) and ACT1-R (GCGCTAGAACATACCAGAATCC) for ChIP with Myc antibody. To correct for potential variations in nucleosome occupancy, the abundance of H3-Ac, H4-Ac, or H3-K79-Me was calculated as the ratio of signal (IP/input) obtained using antibody against H3-Ac, H4-Ac, or H3-K79-Me over that obtained using antibody against total H3. The means of data from three independent experiments together with corresponding S.D. were presented.

RESULTS

FUN30 and ISW1 Are Required for Efficient Transcriptional Silencing at the HML Locus

Although heterochromatin at HML and HMR loci is formed via a common mechanism, the extent and regulation of transcriptional silencing at each locus is not identical. For example, HMR silencing is more dependent on the nearby telomere than HML silencing, whereas HML silencing is preferentially affected by certain histone mutations (30, 31). Although FUN30 and ISW1 are required for HMR silencing, it has not been examined whether they are also required for HML silencing (20, 22). To address this question, we deleted FUN30 and ISW1 individually from strain 1 bearing a URA3 reporter in the middle of HML (Fig. 1A; Table 1). URA3 expression makes cells sensitive to 5-fluoroorotic acid (FOA), so URA3 silencing can be measured by cell growth on FOA-containing medium (32). We found that deletion of FUN30 and ISW1 reduced URA3 silencing to similar degrees (Fig. 1A, compare 2 and 3 with 1). Therefore, Fun30p and Isw1p are required for full transcriptional silencing at HML.

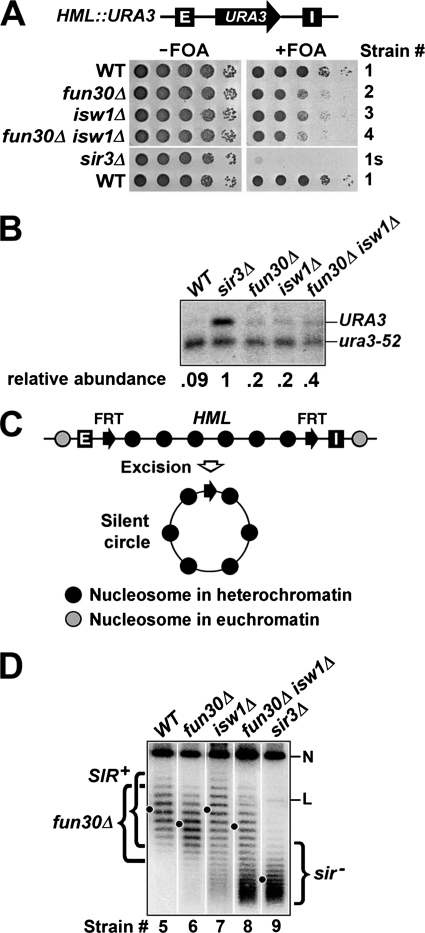

FIGURE 1.

Effects of fun30Δ and isw1Δ on transcriptional silencing and DNA supercoiling at HML. A, FUN30 and ISW1 are required for efficient HML silencing. Top, a schematic of the HML locus bearing a URA3 marker gene in strains 1–4 and 1s is shown. HML-E and -I silencers are shown as filled boxes with white letters. Bottom, growth phenotypes of strains 1–4 and 1s are shown. Cells of each strain were grown to log phase, and serial 10-fold dilutions were spotted and grown on synthetic medium with (+) or without (−) 1 mg/ml of FOA. B, Northern blot analysis of URA3 expression is shown. Total RNA was extracted from log phase cells of each strain, and 10 μg was loaded in each lane. URA3 mRNA was detected by Northern blotting and hybridization with a radioactive probe made from the coding sequence of URA3. Note that in the strains tested here, the transcript from the nonfunctional ura3-52 allele at the normal URA3 locus on chromosome V is truncated, due to the insertion of a Ty element into the URA3 coding sequence. Therefore, transcripts from both URA3 gene at HML and ura3-52 allele could be examined simultaneously. As the normal URA3 locus is not subject to SIR-dependent silencing, ura3-52 mRNA was used as an internal control for loading. The intensity of each band was quantified using NIH image, and the relative abundance of URA3 mRNA in each strain was calculated as the ratio of URA3 mRNA signal over ura3-52 mRNA signal. C, shown is the strategy for examining the topology of HML DNA (27). Two FRT (Flp1p recombination target) sequences (filled arrows) are inserted to flank HML. Recombination between FRTs by the site-specific recombinase Flp1p excises HML as a circular minichromosome. D, FUN30 but not ISW1 is required for the high negative supercoiling of HML DNA. DNA isolated from strains 5 (WT), 6 (fun30Δ), 7 (isw1Δ), 8 (fun30Δ isw1Δ), and 9 (sir3Δ) was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of 26 μg/ml chloroquine. After Southern blotting, topoisomers of the HML circle were detected by an HML-specific probe. Under the conditions employed here, more negatively supercoiled topoisomers migrate more slowly. The center of distribution of topoisomers from each strain is indicated by a dot. The nicked/relaxed and linear forms of the HML circle are indicated as N and L, respectively. Topoisomers of HML circle from WT, fun30Δ and sir3Δ strains are collectively designated SIR+, fun30Δ, and sir−, respectively.

The fact that neither FUN30 deletion (fun30Δ) nor isw1Δ completely eliminated HML silencing as does sir3Δ (Fig. 1A, compare 2 and 3 with 1s) made us wonder whether Fun30p and Isw1p were redundantly required for HML silencing. We showed that simultaneously deleting both FUN30 and ISW1 caused a decrease in URA3 silencing that is slightly more severe than the reduction of silencing caused by fun30Δ or isw1Δ alone (Fig. 1A, compare 4 with 2 and 3). Therefore, Fun30p and Isw1p seem to play partially overlapping roles in HML silencing.

To complement the assay of URA3 silencing by monitoring cell growth on FOA containing medium, we also used Northern blotting to directly measure the level of URA3 mRNA in wild type and sir3Δ strains as well as fun30Δ and isw1Δ single and double mutants. As expected, URA3 mRNA was abundant in the sir3Δ strain in which silencing was abrogated but was hardly detectable in the SIR3+ (wild type (WT)) strain where URA3 at HML was silenced (Fig. 1B, note the abundance of URA3 mRNA in WT strain was 11-fold less than that in sir3Δ strain). In the fun30Δ or isw1Δ strain, the URA3 mRNA level was 5-fold less than that in WT strain but 2-fold more than that in sir3Δ strain (Fig. 1B), supporting the notion that FUN30 and ISW1 are required for full transcriptional silencing. URA3 mRNA in the fun30Δ isw1Δ double mutant was 2-fold more abundant than that in either single mutant (Fig. 1B), suggesting that FUN30 and ISW1 play partially overlapping roles in HML silencing. In summary, these results are fully consistent with results of monitoring cell growth on FOA medium (Fig. 1, A and B).

FUN30 but Not ISW1 Is Required for the High Negative Supercoiling of Silent HML DNA

As both Fun30p and Isw1p have chromatin remodeling activities (23, 33), they may contribute to the formation of the special heterochromatin structure. We tested this notion using a DNA topology based assay. In eukaryotes, formation of each nucleosome constrains on average one negative supercoil on nucleosomal DNA (34). This number is reduced (to as low as 0.8) if histones in the nucleosome are acetylated (35, 36). Therefore, the topology of DNA spanning a specific region is a measure of the state of local chromatin. We and others have previously developed a method to examine DNA topology at a particular locus by excising the region as a circular minichromosome via a site-specific recombination in vivo and isolating the DNA circle whose supercoiling can be determined by gel electrophoresis in the presence of a DNA intercalator (Fig. 1C) (27, 37). Using this method, it was found that DNA from HML or HMR is more negatively supercoiled when the locus is silenced than when it is derepressed (24, 27, 37), which is a reflection of the high regularity/density of nucleosomes as well as low histone acetylation in heterochromatin (10, 11, 38, 39).

To test if FUN30 and ISW1 play roles in heterochromatin structure at HML, we deleted them individually from strain 5 in which the modified HML locus excluding the E and I silencers is flanked by two copies of FRT (Flp1p recombination target), the recognition site for the site-specific recombinase Flp1p (Fig. 1C). Induction by galactose of a PGAL10-FLP1 gene integrated elsewhere in the genome would lead to the expression of Flp1p and recombination between the FRT sites, resulting in the excision of an HML circle (Fig. 1C). After being deproteinized, the supercoiling of the circle could be examined by gel electrophoresis in the presence of the DNA intercalator chloroquine (Fig. 1D, strain 5). Deletion of SIR3, which completely disrupts heterochromatin, reduced the negative supercoiling of HML circle by a linking number change (ΔLk) of 9 (Fig. 1D, compare the centers of topoisomer distributions in lanes 5 and 9; note that more negatively supercoiled circles migrate more slowly under the condition used).

We showed that fun30Δ reduced the negative supercoiling of HML DNA by a linking number change of ∼2 (ΔLk = ∼2) (Fig. 1D, compare 5 and 6), suggesting a role of Fun30p in heterochromatin structure. It is obvious that the fun30Δ-induced change in HML DNA topology is significantly smaller than the ΔLk of 9 caused by the complete disruption of heterochromatin by sir3Δ (Fig. 1D, compare 5 and 6 with 9), which is consistent with the fact that fun30Δ does not completely abolish HML silencing (Fig. 1, A and B). Unlike fun30Δ, isw1Δ did not reduce the supercoiling of HML DNA (Fig. 1D, compare 7 with 5). On the other hand, a small portion of HML circles from isw1Δ cells had a topology similar to circles from sir3Δ cells (Fig. 1D, compare 7 and 9). We have shown previously that silent HML circles lacking silencers would gradually lose their high negative supercoiling and assume a topology similar to HML circles in sir− cells when the host cells progress in the cell cycle, which suggests that the heterochromatin dissociated from silencers is subject to disruption during cellular proliferation (27). Therefore, the minor population of sir− circles from isw1Δ cells was the result of disruption of heterochromatin on HML circle during the 2.5-h induction of circle excision when cells continued to grow. The fact that no sir− circles existed in samples from WT and fun30Δ strains suggests that HML heterochromatin is less stable in isw1Δ cells than in WT or fun30Δ cells.

HML circles from the fun30Δ isw1Δ strain consisted of two major populations, one with a topology similar to fun30Δ circles and the other similar to sir− circles (Fig. 1D, compare 8 with 6 and 9). This indicates that the effect of fun30Δ on the topology of HML DNA is dominant over than of isw1Δ, and that fun30Δ and isw1Δ have a synthetic destabilizing effect on the HML heterochromatin.

Contribution of Fun30p to the Special Structure of Heterochromatin

Our finding that fun30Δ reduces the negative supercoiling of HML DNA (Fig. 1D) suggests that fun30Δ alters the structure of heterochromatin. To directly test if Fun30p plays a role in the unique primary structure of heterochromatin, we mapped nucleosomes within HML in fun30Δ and FUN30 cells by MNase digestion and indirect end labeling. As MNase preferentially digests linker DNAs connecting the nucleosomes, indirect end labeling of MNase-digested DNA can reveal the borders of nucleosomes in the region of interest, thereby allowing the inference of the positions of nucleosomes (40).

DNA from chromatin treated with MNase was isolated and subjected to digestion by EcoRI, PvuII, or NgoMIV at the HML locus (Fig. 2A and 3A) followed by electrophoresis and Southern blotting. DNA fragments ending at the EcoRI, PvuII, and NgoMIV restriction sites were detected by probes 1 through 3, respectively (Figs. 2A and 3A). In the WT strain, 20 positioned nucleosomes could be inferred from the MNase digestion pattern of the 3.3-kb HML sequence bracketed by the E and I silencers (Figs. 2, B and C, and 3B, filled ovals labeled 1–20). The positions of these nucleosomes generally matched those of the 20 positioned nucleosomes (numbered 1–20) at HML inferred from previous chromatin mapping results obtained by Weiss and Simpson (11) and us (12). We numbered the 20 nucleosomes following the Weiss and Simpson early designations (11). Note the region between nucleosomes 9 and 10 containing the UAS of the α genes was free of nucleosomes (Fig. 2B). Deletion of SIR2 caused salient changes in the profile of MNase-sensitive sites across most of HML (Fig. 2, B and C, compare sir2Δ with WT; note the differences in intensities of MNase digestion sites between sir2Δ and WT lanes as indicated by open diamonds). These changes affected the borders of nucleosomes 4–16 to various extents, confirming that Sir complex promotes nucleosome rearrangement during the formation of heterochromatin structure at HML (11, 12). We noted that the lower parts of the Southern blots shown in Fig. 2B were over-exposed, which might have obscured changes in intensities of MNase sites there. To address this issue, we also presented the same blots that had been exposed for a shorter time in supplemental Fig. S1. This more clearly revealed the sir2Δ-induced changes around the shared borders of nucleosomes 3 and 4 (supplemental Fig. S1, compare sir2Δ with WT).

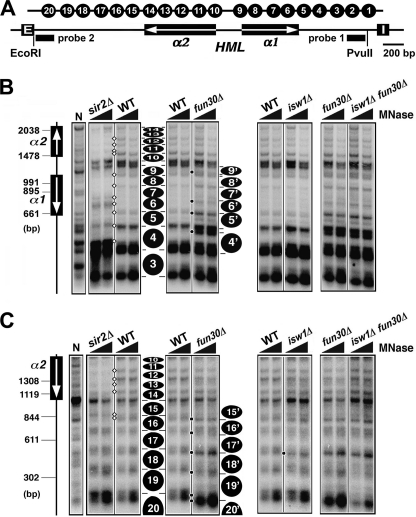

FIGURE 2.

Effects of fun30Δ and isw1Δ on the primary chromatin structure of HML. A, shown is the HMLα locus. The HML-E and -I silencers and the α1 and α2 genes are shown. Filled bars indicate the sequences of probes 1 and 2 used in indirect end labeling experiments shown in B and C, respectively. The positions of 20 nucleosomes inferred from a previous mapping experiment (11) are shown at the top. B and C, examination of HML chromatin in strains 10 (WT), 11 (sir2Δ), 12 (fun30Δ), 13 (isw1Δ), and 14 (fun30Δ isw1Δ) by MNase digestion and indirect end labeling is shown. DNA isolated from MNase-treated chromatin was digested with PvuII (B) or EcoRI (C) and fractionated on agarose gels. Genomic (naked) DNA from strain 10 (WT) was also treated with MNase and then digested with PvuII (B) or EcoRI (C). This sample is designated N. After Southern-blotting, DNA fragments were detected by probe 1 near the PvuII site (B) or probe 2 near the EcoRI site (C). The relative positions of the α1 and α2 genes are shown on the left. The positions of inferred nucleosomes are indicated by filled ovals. Some bands representing MNase sensitive sites are indicated by open diamonds or (see “Results” for descriptions).

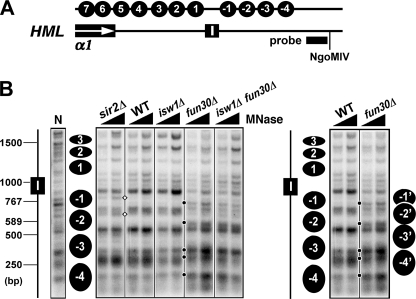

FIGURE 3.

Effects of fun30Δ and isw1Δ on the primary chromatin structure around the HML-I silencer. A, schematics of the region around HML-I are shown. The filled bar indicates the sequence of probe 3 used in the indirect end labeling experiment shown in B. The positions of nucleosomes 1–7 mapped previously (11) and -1 through -4 mapped in B are indicated at the top. B, mapping chromatin around HML-I in strains 10–14 is shown. DNA isolated from MNase treated chromatin was digested with NgoMIV and fractionated on an agarose gel. Genomic DNA (naked DNA, designated N) from strain 10 was also treated with MNase and then digested with NgoMIV. After Southern blotting, DNA fragments ending at the NgoMIV site were detected by hybridization with probe 3. The position of the HML-I silencer is shown on the left. The positions of inferred nucleosomes are indicated by filled ovals. Some bands representing MNase-sensitive sites are indicated by open diamonds or black dots (see “Results” for descriptions). Note the WT and fun30Δ lanes were aligned side by side on the right for better comparison and illustration of the positions of inferred nucleosomes.

We showed that deletion of FUN30 induced multiple alterations in the MNase digestion profile at HML (Fig. 2, B and C, and supplemental Fig. S1; note the unique presence or change in intensity of MNase sites in fun30Δ lanes versus WT lanes as indicated by black dots). Part of the alterations affected the borders of nucleosomes 5–8 in such a way that they suggest a fun30Δ-induced reduction in the translational dynamics of these nucleosomes (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. S1, compare fun30Δ and WT; note that sites coinciding with the borders of nucleosomes 5–8 were more accessible to MNase in fun30Δ versus WT cells).

FUN30 deletion induced the appearance of two strong MNase digestion sites in the regions covered by nucleosomes 4 and 9, suggesting a repositioning/sliding of these nucleosomes to positions 4′ and 9′, respectively (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. S1). As a consequence, nucleosomes 4′ and 5′ were separated by a relatively big gap, as were nucleosomes 8′ and 9′ (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. S1). The presence of these gaps may be related to the reduced silencing function of HML heterochromatin in fun30Δ cells (Fig. 1, A and B). A series of changes caused by fun30Δ affected the borders of nucleosomes 15–19 in such a way that they suggest a fun30Δ-induced sliding en bloc of nucleosomes 15–19 (and 20 by inference) toward the HML-E silencer to positions denoted 15′–20′ (Fig. 2C, compare fun30Δ and WT).

Importantly, the changes in MNase digestion (hence, the inferred alterations in nucleosome positioning) within HML caused by fun30Δ generally did not overlap with those induced by sir2Δ (Fig. 2, B and C). Therefore, in the absence of Fun30p, chromatin at HML adopts a unique structure that is different from both the fully silent heterochromatin structure (in WT strain) and the fully derepressed chromatin structure (in sir2Δ strain).

Mapping chromatin in the region surrounding the HML-I silencer revealed 4 nucleosomes (designated −1 through −4) positioned immediately outside of the border of HML defined by HML-I (Fig. 3B). Deletion of SIR2 renders two sites more accessible to MNase digestion with one in nucleosome -1 and the other around the shared border of nucleosomes -1 and -2 (Fig. 3B, bands in the sir2Δ lanes indicated by open diamonds). These changes suggest that nucleosomes -1 and -2 can adopt alternative positions in derepressed chromatin. Therefore, formation of Sir-dependent heterochromatin involves the repositioning/stabilization of nucleosomes -1 and -2. Interestingly, fun30Δ induced extensive changes in MNase digestion pattern in the region spanning nucleosomes -1 through -4 (Fig. 3B, right; note the unique presence or enhancement of MNase sites in fun30Δ lanes versus WT lanes as indicated by black dots). These changes suggest that in the absence of FUN30, nucleosomes -1 through -4 can slide en bloc toward the HML-I silencer to adopt alternative positions -1′ through -4′ (Fig. 3B, right). Again, these changes did not overlap with the changes induced by sir2Δ.

In summary, we found evidence indicating that fun30Δ leads to the change in the positioning and/or stability of at least 12 nucleosomes (#4–9 and #15–20) within HML and 4 nucleosomes outside of HML (#-1 to -4) (Figs. 2 and 3). Therefore, Fun30p plays a major role in the primary structure of HML heterochromatin. In the absence of Fun30p, heterochromatin seems to adopt an altered/intermediate state that is distinct from the fully silenced state (in WT cells) and the completely derepressed state (in sir2Δ cells).

Isw1p Does Not Significantly Contribute to Heterochromatin Structure

We found that, unlike fun30Δ, isw1Δ did not cause substantial changes in HML chromatin (Figs. 2, B and C, and 3B; compare isw1Δ and WT lanes), which was correlated with the lack of effect of isw1Δ on HML DNA supercoiling (Fig. 1D). One relatively obvious change induced by isw1Δ was the moderate increase in MNase sensitivity of a site coinciding with the shared border of nucleosomes 17 and 18 (Fig. 2C). Note that this change coincides with one of many alterations induced by fun30Δ (Fig. 3B, compare fun30Δ and isw1Δ). Therefore, unlike Fun30p, Isw1p seems to make a minimum contribution to the primary structure of HML heterochromatin.

Fun30p and Isw1p Do Not Play Redundant Roles in Heterochromatin Structure

It is possible that although Isw1p does not contribute significantly to heterochromatin structure on its own, it synergizes with Fun30p to facilitate the formation of heterochromatin. To test this hypothesis, we mapped HML chromatin in isw1Δ fun30Δ double mutant. We found that the pattern of MNase digestion in the double mutant was identical with that in the fun30Δ mutant (but not with that in the isw1Δ mutant) (Figs. 2, B and C, and 3B, compare isw1Δ fun30Δ with fun30Δ and isw1Δ lanes). Therefore, fun30Δ has a dominant effect over isw1Δ on the HML heterochromatin structure, and Fun30p and Isw1p do not cooperate to contribute to heterochromatin structure at HML.

Fun30p Does Not Remodel Derepressed HML Chromatin

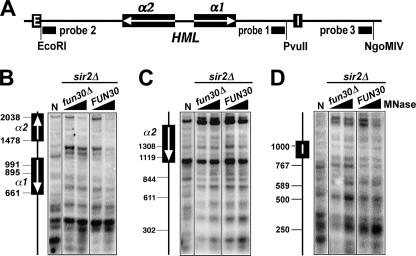

Results from the above experiments strongly suggest an important role of Fun30p in the formation of the primary heterochromatin structure at HML. It is possible that Fun30p helps to create a chromatin configuration prior to heterochromatin formation that is favorable for the spreading of Sir complex. This model predicts that Fun30p modulates HML chromatin in the absence of Sir complex. We tested this model by comparing HML chromatin structure in fun30Δ with that in FUN30 strain in the sir2Δ background. We found no obvious differences between sir2Δ and sir2Δ fun30Δ strains regarding the profile of MNase digestion across the entire HML locus (Fig. 4, B–D, compare fun30Δ and FUN30). Therefore, fun30Δ does not affect derepressed HML chromatin structure in the absence of Sir complex, which argues against the model that Fun30p facilitates the formation of heterochromatin structure by modulating derepressed chromatin in preparation for Sir complex spreading.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of fun30Δ on the primary chromatin structure of HML in the sir− background. A, shown is the HMLα locus. Filled bars indicate the sequences of probes 1–3 used in indirect end labeling experiments shown in B–D, respectively. B–D, examination of HML chromatin in strains 11 (sir2Δ) and 15 (sir2Δ fun30Δ) by MNase digestion and indirect end labeling. MNase-treated chromatin was digested with PvuII (B), EcoRI (C), or NgoMIV (D) and fractionated on an agarose gel. After Southern blotting, DNA fragments ending at the PvuII (B), EcoRI (C), or NgoMIV (D) site were detected by hybridization with probes 1–3, respectively. The position of the α genes and HML-I silencer are shown on the left of the blots. N, naked DNA.

FUN30 Is Required for de Novo Establishment of Fully Silent Heterochromatin Structure

Given that fun30Δ makes heterochromatin assume an altered/intermediate state but does not affect derepressed chromatin at HML, we propose that Fun30p is specifically involved in the formation of heterochromatin. We examined whether fun30Δ affected de novo establishment of heterochromatin. This was achieved by monitoring the kinetics of the transition from a derepressed to silenced state of a circular HML minichromosome after the activation of the Sir complex in a strain bearing sir3-8, a temperature-sensitive allele of SIR3 (41). Sir3-8p is nonfunctional at 30 °C but functional at 23 °C (41). The state of the HML minichromosome was measured by examining the negative supercoiling of the DNA.

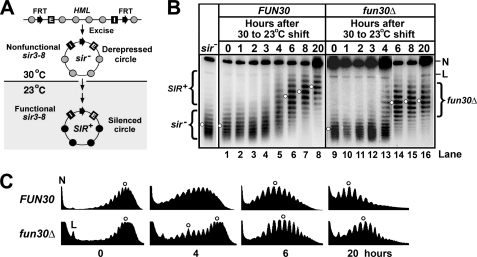

A pair of isogenic sir3-8 FUN30 and sir3-8 fun30Δ strains was constructed in which HML including the silencers was flanked by FRTs, and PGAL-FLP1 was integrated elsewhere in the genome (Fig. 5A). Each strain was first grown to log phase at 30 °C in YPR medium. Galactose was then added to the culture that was further incubated for 2.5 h to induce PGAL-FLP1 and the excision of the HML circle. Cells were then shifted to YPD (yeast extract/peptone + glucose) and further grown at 23 °C. The short half-life of Flp1p and the stringent repression by glucose of PGAL-FLP1 ensured that HML circles were excised exclusively during the 2.5 h of galactose induction (27, 42, 43). The HML circle isolated at 30 °C assumed a topology characteristic of HML circle from a sir− strain (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 1 and 9 with the sir− lane), which verifies the inactivity of sir3-8 at 30 °C.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of fun30Δ on de novo establishment of HML heterochromatin structure. A, shown is a strategy for examining the de novo establishment of heterochromatin on circular HML minichromosome. Shaded and filled circles denote nucleosomes in derepressed chromatin and heterochromatin, respectively. The HML locus including the E and I silencers is flanked by a pair of FRTs. See “Results” for description of the scheme. B, examination of the kinetics of establishment of heterochromatin on HML circle in strains 16 (sir3-8 FUN30) and 17 (sir3-8 fun30Δ). Cells of each strain grown at 30 °C in YPR medium were treated with galactose for 2.5 h to induce excision of the HML circle. Cells were then shifted to fresh YPD (yeast extract/peptone + glucose) medium and incubated at 23 °C for up to 20 h. Aliquots of the culture were harvested at time points 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 20 h. DNA was isolated and fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of 26 μg/ml chloroquine. Under the conditions used, more negatively supercoiled topoisomers run more slowly. N and L, nicked and linear forms of the HML circle, respectively. The topoisomers corresponding to the silent and derepressed states of HML circles are designated SIR+ and sir−, respectively. C, the profiles of topoisomers in lanes 1, 5, 6, and 8 and 9, 13, 14, and 16 were determined using the NIH image software. The centers of distribution of topoisomers are marked by open circles.

HML circles were isolated from aliquots of culture taken at a series of time points after the temperature shift from 30 to 23 °C. We found that in FUN30 cells, starting around hour 4, the HML circles became more and more negatively supercoiled (Fig. 5B, lanes 5–8), which is indicative of the formation of heterochromatin on these circles. The gradual nature of the increase of negative supercoiling of HML DNA (Fig. 5B) suggests that formation of fully silenced chromatin was a stepwise process.

HML circles in fun30Δ cells also became more negatively supercoiled after incubation at 23 °C (Fig. 5B, lanes 9–16), suggesting that heterochromatin was able to form on these circles in the absence of Fun30p. However, the level of negative supercoiling of HML circle did not increase significantly after hour 6 (Fig. 5B, lanes 14–16), which is different from the gradual increase of negative supercoiling found in the FUN30 background (Fig. 5B, lanes 6–8). As a consequence, the final level of supercoiling of the HML circle (after prolonged incubation at 23 °C) was lower in fun30Δ cells than in FUN30 cells (Fig. 5, B and C, compare fun30Δ and FUN30 samples at 20 h). These data are consistent with the notion that in fun30Δ cells, an altered/intermediate state of heterochromatin is formed that fails to be further converted to the fully silent state of heterochromatin (as can be formed in FUN30 cells). In addition, we showed that the rate of conversion of HML circles from derepressed state to silent state was reduced by fun30Δ (Fig. 5, B and C; note that at hour 4 the residual population of sir− circles in fun30Δ cells was significantly larger than that in FUN30 cells). Therefore, Fun30p is required for efficient de novo establishment of fully silenced heterochromatin.

Heterochromatin in fun30Δ Cells Retains Characteristic Histone Modifications

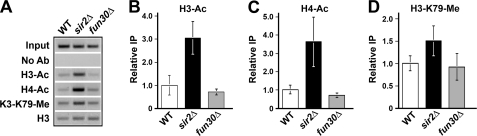

Yeast heterochromatin is characterized by histone hypoacetylation and hypomethylation (9, 13, 14, 38). We wondered whether the altered/intermediate state of heterochromatin formed in fun30Δ cells is different from fully silenced heterochromatin in FUN30 cells regarding the status of histone acetylation and methylation. To address this question, we measured the occupancy of acetylated histones H3 and H4 (H3-Ac and H4-Ac) and histone H3 trimethylated at lysine 79 (H3-K79-Me) at HML in fun30Δ, FUN30 (WT), and sir2Δ cells by ChIP. Three independent experiments were performed. The abundance of an HML sequence in immunoprecipitated chromatin fragments was measured by PCR, and a representative gel picture is shown in Fig. 6A. The intensity of each band was quantified and normalized against input control. To correct for potential variations in nucleosome occupancy in different strains, the occupancy of H3-Ac, H4-Ac, or H3-K79-Me in each strain was presented as the ratio of ChIP signal (IP/input) obtained using an antibody against the respective modified histone over that obtained using an antibody against total histone H3.

FIGURE 6.

Deletion of FUN30 does not affect histone hypoacetylation and hypomethylation in heterochromatin at HML. A, the abundance of an HML sequence in strain 10 (WT), 11 (sir2Δ), or 12 (fun30Δ) was measured by PCR before (Input) and after chromatin IP with antibodies for acetylated histones H3 and H4 (H3-Ac and H4-Ac), and histone H3 methylated at K79 (H3-K79-Me) as well as total H3 (H3). No Ab, samples from mock ChIP without using antibody. The gel picture of PCR products from one of three independent experiments is shown. The data were quantified and plotted in B–D. The value of relative IP of H3-Ac, H4-Ac, or H3-K79-Me was calculated as the ratio of signal (IP/input) for H3-Ac (B), H4-Ac (C), or H3-K79-Me (D) over that for total H3. The means of data from all three independent experiments together with corresponding S.D. are presented. The value for each WT sample is taken as 1.

As expected, the abundances of H3-Ac and H4-Ac at HML in WT cells were markedly lower than their respective counterparts in sir2Δ cells (Fig. 6, A–C), confirming Sir-dependent histone hypoacetylation in heterochromatin. The levels of H3-Ac and H4-Ac at HML in fun30Δ cells were similar to those in WT cells (Fig. 6, A–C). Moreover, fun30Δ and WT cells were similar regarding the abundance of H3-K79-Me at HML (Fig. 6, A and D). Therefore, fun30Δ does not affect the hypoacetylation of histone H3 and H4 and the hypomethylation of H3-K79 in heterochromatin.

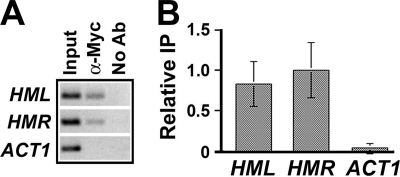

Association of Fun30p with the HML and HMR Loci

We tested if Fun30p could be cross-linked to HML locus by ChIP. The C terminus of endogenous FUN30 in strain 10 was tagged with Myc to make strain 18. Strain 18 was phenotypically indistinguishable from 10, and Fun30p-Myc was expressed as determined by Western blotting (data not shown). An anti-Myc antibody was used to perform ChIP on strain 18. The abundance of sequences from the silent HML and HMR loci as well as active ACT1 locus in the immunoprecipitated chromatin fragments was measured by PCR. Three independent experiments were performed, and a representative gel picture is shown in Fig. 7A. The intensity of each band was quantified and normalized against input control. The mean of data from all of the experiments was graphed in Fig. 7B. We found that Fun30p-Myc is preferentially enriched at the silent HML and HMR loci (Fig. 7B). This is consistent and extends an earlier study showing association of Fun30 with HMR locus (22).

FIGURE 7.

Fun30 is enriched at HML and HMR loci. A, the abundance of HML, HMR, and ACT1 sequences in strain 18 carrying FUN30-Myc was measured by PCR before (Input) and after (α-Myc) chromatin IP with α-Myc antibody. No Ab, samples from mock ChIP without using antibody. The gel picture of PCR products from one of three independent experiments is shown. The data were quantified and are plotted in B. The value of relative IP was calculated as the ratio of IP signal over input signal. The means of data from all three independent experiments together with corresponding S.D. are presented. The value for HMR sequence is taken as 1.

Isw1p Plays a Key Role in Maintaining the Stability of HML Heterochromatin

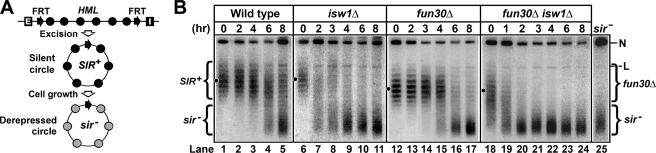

The fact that a small portion of silencer-free HML circles in isw1Δ cells assumes a topology similar to sir− circles (Fig. 1D) suggests that Isw1p is important for the stability of HML chromatin. To further examine the role of Isw1 in maintaining heterochromatin structure, we examined the effect of isw1Δ on the kinetics of the loss of the silent state of silencer-free HML circle after its excision from the genome (27).

Strains 5 (wild type) and 7 (isw1Δ) were grown in parallel to stationary phase before being treated with galactose for 2.5 h to induce the excision of silencer-free HML circles. Cells were then washed and diluted with fresh glucose medium, which inhibited PGAL10-FLP1 and allowed cell cycle progression to resume. The topology of the HML circle was followed during further cell growth in glucose medium. As cells were not growing (in stationary phase) when circles were being excised, the silent state on the HML circle was not disrupted. This was reflected by the fact that HML circle in wild type or isw1Δ cells lacks sir− topoisomers at the 0 h time point (Fig. 8, lanes 1 and 6). In wild type cells, as expected, the proportion of topoisomers with high negative supercoiling characteristic of heterochromatin (SIR+) gradually decreased, whereas that with lower negative supercoiling characteristic of derepressed chromatin (sir−) increased as a function of growth time (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 2–5 with lane 1). The rate of conversion of the HML circle from the SIR+ to sir− state was substantially higher in isw1Δ cells than that in wild type cells (Fig. 8B, compare isw1Δ and wild type). For example, sir− topoisomers were readily detectable by hour 2 in isw1Δ cells but were not present even by hour 4 in wild type cells (Fig. 8B, compare lane 7 with lane 3). By hour 6, most of HML circles had been converted to the sir− state in isw1Δ cells, whereas the majority of HML circles maintained the SIR+ state in wild type cells (Fig. 8B, compare lane 10 with 4). These results demonstrate a critical role of Isw1p in the stability of HML heterochromatin.

FIGURE 8.

ISW1 is required for maintaining the stability of HML heterochromatin. A, a strategy for examining the stability of heterochromatin on HML minichromosome dissociated from silencers is shown. Filled and shaded circles denote nucleosomes in silent and derepressed chromatins, respectively. See “Results” for a description. B, examination of the kinetics of the conversion of silent HML circle (SIR+) to derepressed circle (sir−) in strains 5 (wild type), 6 (fun30Δ), 7 (isw1Δ), and 8 (fun30Δ isw1Δ) is shown. Cells of each strain grown to stationary phase in YPR were treated with galactose for 2.5 h to induce the excision of the HML circle. Cells were then shifted and diluted into fresh yeast extract/peptone/glucose medium and further incubated for 8 h. Aliquots of culture were harvested at time points 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 h. DNA was isolated from the samples and fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of chloroquine. N and L, nicked and linear forms of the HML circle, respectively. Topoisomers corresponding to the silent and derepressed states of HML circles are designated SIR+ and sir−, respectively. Topoisomers of HML circle from the fun30Δ strain are designated fun30Δ.

We also examined if fun30Δ affected the stability of HML chromatin. We showed that the rate of loss of silent state of HML circles in fun30Δ cells was higher than that in wild type cells (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 12–17 with 1–5), albeit to a lesser extent relative to that in isw1Δ cells (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 12–17 with 6–11). This result suggests that HML chromatin in fun30Δ cells is less stable than that in wild type cells.

We further examined whether Isw1p was involved in the maintenance of the stability of HML chromatin in fun30Δ cells. We showed that the loss rate of the silent state of HML circle in the fun30Δ isw1Δ double mutant was markedly greater than that in fun30Δ and isw1Δ single mutants (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 18–24 with 12–17; note that by hour 2, nearly all HML circles had been converted to the sir− state in the fun30Δ isw1Δ double mutant, but no sir− topoisomers were detectable in fun30Δ cells). Therefore, Isw1p is also required for the stability of the intermediate state heterochromatin formed in the absence of Fun30p. In other words, Fun30p and Isw1p play redundant roles in the maintenance of heterochromatin stability.

DISCUSSION

Establishment of heterochromatin in eukaryotes involves rearrangement of the primary chromatin structure and potentially formation of high-order structures (2–4). Chromatin remodeling activities have been implicated in the formation of heterochromatin in different model organisms. In Drosophila, the chromatin remodeling factor dATRX is involved in heterochromatin function and co-localizes with the heterochromatin protein HP1 (5). In fission yeast, a Snf2p homolog Mit is required for heterochromatin at the silent mating locus, whereas the histone chaperone and remodeling complex FACT is required for centromeric-heterochromatin function (7, 8). In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, chromatin remodeling proteins Fun30p, Isw1p, and Snf2p each have been implicated in heterochromatin at one or more loci (20–22). However, the roles of chromatin remodeling factors in the structure and maintenance of heterochromatin remain unresolved. We show in this report that Fun30p plays a key role in nucleosome rearrangement associated with the formation of heterochromatin, whereas Isw1p is critically required for the stability of heterochromatin.

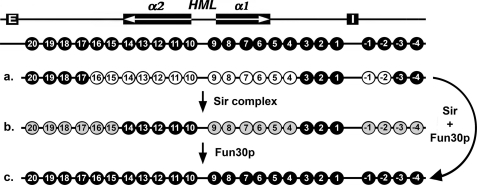

Deletion of FUN30 results in extensive changes in the primary structure of heterochromatin pertaining to nucleosome positioning at HML (Figs. 2 and 3). However, these changes are fundamentally different from those caused by sir2Δ that completely disrupts heterochromatin (summarized in Fig. 9). These results, together with the fact that partial HML silencing is maintained in fun30Δ cells (Fig. 1, A and B) suggest that in the absence of Fun30p, a partially silent, intermediate state of heterochromatin that differs from both the fully silent state and fully derepressed state of chromatin is formed. This intermediate state is associated with hypoacetylation and hypomethylation of histones (Fig. 6), two hallmarks of heterochromatin (9, 13, 14, 38). Why is the putative intermediate state of heterochromatin in fun30Δ cells less efficient in silencing relative to heterochromatin in FUN30 cells? We found that fun30Δ creates relatively large gaps between two adjacent nucleosomes in two instances (Fig. 2B, see the gap between 4′ and 5′ and that between 8′ and 9′). Given that large gaps in the nucleosome array are disruptive to heterochromatin function (25), it is possible that these fun30Δ-induced gaps in HML heterochromatin are at least part of the reason for the decrease in silencing. Therefore, Fun30p may serve to remove gaps in chromatin thereby contributing to efficient silencing mediated by heterochromatin.

FIGURE 9.

Contribution of Fun30p to the special primary structure of HML heterochromatin. Illustrated is a summary of chromatin mapping data shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The HML locus and nucleosomes 1–20 and -1 through -4 in silent (SIR+) HML heterochromatin are shown as filled ovals at the top. a, shown is nucleosome distribution in HML chromatin in the derepressed state (in the absence of Sir complex). Open circles represent the nucleosomes in the derepressed (sir−) state that differ in position and/or stability from their counterparts in the silent (SIR+) state. b, shown is nucleosome distribution in HML chromatin in an intermediate state (in the absence of Fun30p). Shaded circles represent the nucleosomes in the intermediate (fun30Δ) state that differ in position and/or stability from their counterparts in the silent (SIR+) state. c, shown is nucleosome distribution in HML chromatin in fully silenced heterochromatin state.

Fun30p might directly contribute to the formation of heterochromatin structure by the following three mechanisms that are not mutually exclusive. First, Fun30p may modulate chromatin before Sir complex spreading. As the Sir complex deacetylates and propagates along chromatin, the structure of the preexisting chromatin has the potential of influencing the efficiency of Sir complex spreading. It is believed that a highly regular array of nucleosomes is more conducive to Sir protein spreading than a random array. In fact, we have shown that large gaps between nucleosomes are inhibitory to the propagation of Sir complex (25). Fun30p may reposition nucleosomes into a better-ordered array that is more favorable for Sir complex spreading. However, this notion is not supported by our finding that Fun30p does not modulate the HML chromatin structure in a sir− background (Fig. 4). Second, Fun30p may remodel or reposition nucleosomes simultaneously with the spreading of Sir complex along chromatin (Fig. 9, curved arrow). Fun30p may remodel a nucleosome immediately after it is deacetylated by Sir complex or vice versa (i.e. Sir complex deacetylates and binds the nucleosome immediately after it is remodeled by Fun30p). Third, Fun30p may remodel chromatin after Sir complex spreading. This model implies that without Fun30p, Sir complex spreading (perhaps with the assistance of another yet to be identified chromatin remodeler(s)) only results in the formation of an immature or intermediate state of heterochromatin. Fun30p remodels such a chromatin structure thereby converting it into the final mature heterochromatin that is fully silenced (Fig. 9, sequential arrows designated Sir complex and Fun30p). The second and third models, especially the third one, are in line with our finding that partially silenced heterochromatin with a unique structure is formed at HML in the absence of Fun30p (Fig. 9b).

There is evidence suggesting that the establishment of yeast heterochromatin involves discrete ordered steps that are regulated by the cell cycle (44–46). When de novo formation of heterochromatin is allowed to begin in G1 phase, gene silencing does not occur in G1 phase, limited silencing happens in S-phase, partial silencing is achieved during G2/M, and it is not until telophase of mitosis that robust silencing takes place (44, 45). It is possible that intermediate chromatin structures are formed in the different stages of heterochromatin formation before the adoption of a final/mature structure. Fun30p might be involved in a specific stage(s) of the process of heterochromatin formation. Given that Fun30p is known to be subject to phosphorylation by the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1p (47), it is possible that the role of Fun30p in the formation of heterochromatin is subject to cell cycle regulation.

Our finding that fun30Δ affects heterochromatin but not derepressed chromatin at HML raises the important question of how Fun30p function is specifically directed to heterochromatin. Many chromatin remodeling proteins associate with other factors to form multisubunit complexes (48). These complexes contain conserved motifs such as the SANT, bromodomain, and chromodomain that recognize distinct features of chromatin. Therefore, these domains are responsible for targeting chromatin remodeling complexes to specific chromatin structures/loci. Fun30p belongs to a subfamily of Snf2p-like ATPases that contain one or two copies of a putative CUE (coupling of ubiquitin conjugation to ER (endoplasmic reticulum) degradation) motif that is similar to the UBA (ubiquitin-associated domain) motif that binds ubiquitin (22, 49). As there is evidence suggesting an involvement of protein ubiquitination in transcriptional silencing, it is possible that the CUE motif of Fun30p helps to target Fun30p activity to heterochromatin regions by recognizing a ubiquitinated component of heterochromatin.

Deletion of ISW1 reduces HML silencing to a similar extent as fun30Δ does. However, isw1Δ causes minimum change in heterochromatin structure and does not affect the supercoiling of HML DNA (Figs. 1–3), suggesting that Isw1p does not contribute significantly to the primary structure of heterochromatin as Fun30p does. Instead, Isw1p is critically required for the stability of heterochromatin (Fig. 8). This is in line with the fact that Isw1p has the ability to assemble or stabilize nucleosomes (33). Exactly how Isw1p helps to maintain the stability of heterochromatin remains unclear. Based on the fact that Isw1p contains a SANT motif that can recognize unmodified histone tails (50), it is possible that Isw1p is targeted to and remodels nucleosomes deacetylated by Sir2p, making them more stable during or after the propagation of Sir complex. The ISWI complex in Drosophila regulates high-order chromatin structure (6). Isw1p might also help to maintain yeast heterochromatin by stabilizing high-order chromatin structures.

The fact that a partially silent chromatin structure that is different from derepressed chromatin in nucleosome arrangement is still formed in the absence of Fun30p (and Isw1p) (Figs. 2 and 3) suggests that other chromatin remodeling activities may also be involved in forming heterochromatin structure. Besides Fun30p and Isw1p, there are several other known chromatin remodeling proteins including Isw2p, Chd1p, Ino80p, and Rad54p in yeast (51). Although deleting any one of them does not significantly affect heterochromatic gene silencing,4 it is formally possible that these factors play redundant roles in heterochromatin.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Kurt Runge and James Broach for the gifts of yeast strains.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM62484 (to X. B.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

X. Zhang, Q. Yu, and X. Bi, unpublished results.

- HML

- homothallic mating locus left

- HMR

- homothallic mating locus right

- MNase

- micrococcal nuclease

- FOA

- 5-fluoroorotic acid

- FRT

- Flp1p recombination target

- IP

- immunoprecipitation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Grewal S. I., Moazed D. (2003) Science 301, 798–7802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dillon N. (2004) Biol. Cell 96, 631–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sun F. L., Cuaycong M. H., Elgin S. C. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2867–2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wallrath L. L., Elgin S. C. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1263–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bassett A. R., Cooper S. E., Ragab A., Travers A. A. (2008) PLoS One 3, e2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corona D. F., Siriaco G., Armstrong J. A., Snarskaya N., McClymont S. A., Scott M. P., Tamkun J. W. (2007) PLoS Biol. 5, e232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lejeune E., Bortfeld M., White S. A., Pidoux A. L., Ekwall K., Allshire R. C., Ladurner A. G. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 1219–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sugiyama T., Cam H. P., Sugiyama R., Noma K., Zofall M., Kobayashi R., Grewal S. I. (2007) Cell 128, 491–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rusche L. N., Kirchmaier A. L., Rine J. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 481–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ravindra A., Weiss K., Simpson R. T. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 7944–7950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weiss K., Simpson R. T. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 5392–5403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yu Q., Elizondo S., Bi X. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 356, 1082–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ng H. H., Ciccone D. N., Morshead K. B., Oettinger M. A., Struhl K. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1820–1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Santos-Rosa H., Bannister A. J., Dehe P. M., Géli V., Kouzarides T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47506–47512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moazed D. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 232–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carmen A. A., Milne L., Grunstein M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4778–4781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hecht A., Strahl-Bolsinger S., Grunstein M. (1996) Nature 383, 92–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liou G. G., Tanny J. C., Kruger R. G., Walz T., Moazed D. (2005) Cell 121, 515–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rudner A. D., Hall B. E., Ellenberger T., Moazed D. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4514–4528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuperus G., Shore D. (2002) Genetics 162, 633–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dror V., Winston F. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 8227–8235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neves-Costa A., Will W. R., Vetter A. T., Miller J. R., Varga-Weisz P. (2009) PLoS One. 4, e8111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Awad S., Ryan D., Prochasson P., Owen-Hughes T., Hassan A. H. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9477–9484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bi X., Broach J. R. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1089–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bi X., Yu Q., Sandmeier J. J., Zou Y. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2118–2131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roy N., Runge K. W. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bi X., Broach J. R. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 7077–7087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kent N. A., Bird L. E., Mellor J. (1993) Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 4653–4654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chiu Y. H., Yu Q., Sandmeier J. J., Bi X. (2003) Genetics 165, 115–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park E. C., Szostak J. W. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 4932–4934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thompson J. S., Johnson L. M., Grunstein M. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 446–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Leeuwen F., Gottschling D. E. (2002) Methods Enzymol. 350, 165–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mellor J., Morillon A. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1677, 100–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Simpson R. T., Thoma F., Brubaker J. M. (1985) Cell 42, 799–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Norton V. G., Imai B. S., Yau P., Bradbury E. M. (1989) Cell 57, 449–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Norton V. G., Marvin K. W., Yau P., Bradbury E. M. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 19848–19852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cheng T. H., Li Y. C., Gartenberg M. R. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5521–5526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Braunstein M., Rose A. B., Holmes S. G., Allis C. D., Broach J. R. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 592–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Suka N., Suka Y., Carmen A. A., Wu J., Grunstein M. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 473–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ryan M. P., Stafford G. A., Yu L., Cummings K. B., Morse R. H. (1999) Methods Enzymol. 304, 376–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miller A. M., Nasmyth K. A. (1984) Nature 312, 247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Holmes S. G., Broach J. R. (1996) Genes Dev. 10, 1021–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Volkert F. C., Broach J. R. (1986) Cell 46, 541–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Katan-Khaykovich Y., Struhl K. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 2138–2149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lau A., Blitzblau H., Bell S. P. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2935–2945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Martins-Taylor K., Dula M. L., Holmes S. G. (2004) Genetics 168, 65–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ubersax J. A., Woodbury E. L., Quang P. N., Paraz M., Blethrow J. D., Shah K., Shokat K. M., Morgan D. O. (2003) Nature 425, 859–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Clapier C. R., Cairns B. R. (2009) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 273–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hurley J. H., Lee S., Prag G. (2006) Biochem. J. 399, 361–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. de la Cruz X., Lois S., Sánchez-Molina S., Martínez-Balbás M. A. (2005) Bioessays 27, 164–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Flaus A., Martin D. M., Barton G. J., Owen-Hughes T. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 2887–2905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]