Abstract

Type-specific dendrite morphology is a hallmark of the neuron and has important functional implications in determining what signals a neuron receives and how these signals are integrated. During the past two decades, studies on dendritic arborization neurons in Drosophila melanogaster have started to identify mechanisms of dendrite morphogenesis that may have broad applicability to vertebrate species. Transcription factors, receptor–ligand interactions, various signalling pathways, local translational machinery, cytoskeletal elements, Golgi outposts and endosomes have been identified as contributors to the organization of dendrites of individual neurons and the placement of these dendrites in the neuronal circuitry. Further insight into these mechanisms will improve our understanding of how the nervous system functions and might help to identify the underlying causes of some neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Starting with the seminal work of Ramon y Cayal1, the complexity and diversity of dendritic arbors has been recognized and well documented. How do neurons acquire their type-specific dendrite morphology? What controls the size of a dendritic arbor? How are dendrites of different neurons organized relative to one another? It is important to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of dendrite morphogenesis and to understand how dendrites develop characteristics distinct from those of axons (BOX 1) and how a nervous system is assembled to effectively and unambiguously process internal and external cues so that appropriate responses can be generated.

Box 1. Differential regulation of dendrite and axon growth.

Dendrites differ from axons in many important respects, both morphologically and functionally148. Dendrites have specialized structures including spines, which are the main excitatory synaptic sites that are not found in axons. Unlike axons, dendrites have tapering processes such that distal branches have smaller diameters than proximal ones. Furthermore, dendrites and axons contain different types of organelles — such as Golgi outposts, found primarily in dendrites. The orientation of microtubules also differs considerably in dendrites and axons; in both vertebrates and invertebrates, the microtubules uniformly orient with their plus-end distally in axons, whereas dendrites contain microtubules of both orientations149,150. It is likely that these different cytoskeletal arrangements influence the manner in which organelles and molecules are transported along axons and dendrites. Given their many structural and functional differences, axon and dendrite development must differ in crucial ways151. Indeed, molecules that function specifically in dendrite or axon growth have been discovered. For example, the ubiquitin ligase anaphase-promoting complex specifically regulates axon or dendrite morphogenesis in murine cerebellar granule cells depending on whether it recruits the co-activator cadherin 1 or CDC20 to the complex152,153.

Here, we review recent progress in uncovering the molecular and cell biological mechanisms controlling dendrite morphogenesis, including the acquisition of type-specific dendritic arborization, the regulation of dendrite size and the organization of dendrites emanating from different neurons (TABLE 1). We also consider evidence suggesting that defects in dendrite development and/or maintenance could contribute to neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia, Down’s syndrome, fragile X syndrome, Angelman’s syndrome, Rett’s syndrome and autism2–10.

Table 1.

Examples of molecules involved in dendrite morphogenesis

| Molecules | Functions in dendrite morphogenesis | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription regulators | ||

| CUT | A homeodomain protein that functions as a multi-level regulator of type-specific dendrite morphology of larval dendritic arborization neurons | 27 |

| Abrupt | A BTB–zinc finger protein that is expressed in larval class I dendritic arborization neurons, where it limits dendrite size and branching complexity | 28,29 |

| Collier (also known as Knot) | A member of the early B cell factor or olfactory neuronal transcription factor 1 family that functions in combination with CUT to distinguish class IV from class III dendritic arborization neuron dendrites | 30–32 |

| Spineless | A fly homologue of the mammalian dioxin receptor that diversifies dendrite morphology of larval dendritic arborization neurons | 36 |

| ACJ6 and Drifter | POU-domain proteins that regulate dendritic targeting in the fly olfactory system | 39 |

| CREST | A transactivator that regulates Ca2+-dependent dendrite growth of mammalian cortical and hippocampal neurons | 42 |

| NEUROD1 | A basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) protein that regulates activity-dependent dendrite morphogenesis of mammalian neurons | 41 |

| CREB | A DNA-binding protein that regulates activity-dependent dendrite morphogenesis of mammalian neurons | 43,44 |

| Neurogenin 2 | A bHLH protein that specifies the dendrite morphology of pyramidal neurons in the mammalian neocortex | 40 |

| nBAF complexes | Neuron-specific chromatin remodelling complexes that bind CREST and regulate activity-dependent dendrite development of mammalian CNS neurons; their D. melanogaster homologues are involved in dendrite morphogenesis in dendritic arborization neurons | 33,45 |

| Polycomb group genes | Components of the Polycomb complex that regulate the maintenance of larval dendritic arborization dendrites | 146 |

| Secreted proteins and cell surface receptors | ||

| Neurotrophins and tyrosine kinase receptors | Regulate dendritic growth and complexities of mammalian cortical neurons in a neuronal type-dependent manner | 54,55 |

| BMP7 | Promotes dendrite growth in rat sympathetic neurons | 56 |

| WNT and Dishevelled | Regulate dendrite morphogenesis in mammalian neurons | 72 |

| EPHB1, EPHB2 and EPHB3 | Promote dendritic complexity of mammalian hippocampal neurons | 91 |

| Semaphorins and Plexin–Neuropilin | Regulate dendritic targeting and branching in mammalian cortical neurons and fly olfactory neurons | 48,50,52 |

| Slit and Robo | Regulate dendrite growth and targeting of fly neurons | 46,47,127,128 |

| Netrin and Frazzled | Regulate dendritic targeting of fly motor neurons | 127,128 |

| Reelin | Regulates dendrite growth of mammalian cortical neurons | 135 |

| Cytoskeletal regulators | ||

| RAC and CDC42 | Rho family GTPases that regulate dendrite growth and branching in vertebrate and invertebrate neurons | 59,62,63, 69,71 |

| RHOA | A Rho family GTPase that limits dendrite growth in vertebrate and invertebrate neurons | 60,63,67 |

| Motors | ||

| KIF5 | A kinesin involved in dendrite morphogenesis of mammalian hippocampal neurons | 91 |

| Dynein | Mutations of Dynein cause a distal to proximal shift of the dendrite branching pattern of larval dendritic arborization neurons | 57,58 |

| LIS1 | A dynein-interacting protein linked to lissencephaly; mutations cause reduced dendritic arborization in flies and mice | 57,86–89 |

| Secretory pathway and endocytic pathway | ||

| DAR3 (fly) or SAR1 (mammalian) | A regulator of ER to Golgi transport preferentially required for dendrite growth of mammalian hippocampal neurons and larval dendritic arborization neurons | 82 |

| DAR2 (fly) or SEC23 (mammalian) and DAR6 (fly) or RAB1(mammalian) | Regulators of ER to Golgi transport preferentially required for dendrite versus axonal growth of larval dendritic arborization neurons | 82 |

| RAB5 | A component of the early endocytic pathway that promotes dendrite branching of fly dendritic arborization neurons | 58 |

| Shrub | A fly homologue of SNF7, a component of the ESCRT-III complex, which is a regulator of dendrite branching of larval dendritic arborization neurons | 83 |

| Cell adhesion | ||

| DSCAM (fly) | Mediates self-avoidance of dendrites of the same neuron and enables co-existence of dendrites of different neuron types | 102–105 |

| DSCAM and DSCAML1 (mouse) | Unlike their fly homologues, murine Dscam and Dscaml1 do not undergo extensive alternative splicing; they are required for dendrite self-avoidance but do not confer neuronal identity | 98,109 |

| Hippo pathway | ||

| TRC and FRY | Required for dendritic tiling of larval class IV dendritic arborization neurons | 123 |

| SAX-1 and SAX-2 | Homologues of TRC and FRY required for dendritic tiling in Caenorhabditis elegans | 125 |

| WTS and SAV | Regulators of the maintenance of larval class IV dendritic arborization neurons | 147 |

| Bantam | A microRNA required for dendritic scaling of larval class IV dendritic arborization neurons | 131 |

| Hippo | Regulates dendritic tiling and dendritic maintenance of larval class IV dendritic arborization neurons through the two NDR kinase family members, TRC and WTS, respectively | 147 |

| PIK3–mTOR pathway | ||

| AKT | Promotes dendritic growth and branching of larval class IV dendritic arborization neurons and mammalian cortical neurons | 132–136 |

| PTEN | Limits dendrite growth and branching of larval class IV dendritic arborization neurons | 132 |

| TORC2 | Required for dendritic tiling of larval class IV dendritic arborization neuron | 124 |

| RNA targeting and local translation | ||

| Pumilio and Nanos | RNA-binding proteins required for dendrite growth and branching of larval class III and class IV dendritic arborization neurons | 137 |

| Glorund and Smaug | Bind to Nanos mRNA and regulate dendrite growth of larval class IV dendritic arborization neurons | 138 |

| Staufen 1 | A murine homologue of fly Staufen, which functions in dendritic targeting of ribonucleoprotein particles and dendritic branching | 139 |

| CPEB | A PolyA-binding protein implicated in mRNA trafficking, translational regulation and experience-dependent dendrite growth in frog neurons | 141 |

| FMR1 | Involved in mRNA transport and translation regulation in dendrites, and dendrite morphogenesis | 6 |

| Others | ||

| Origin recognition complex | Regulates dendrite and spine development in mammalian neurons | 80 |

| Anaphase-promoting complex | Specifically regulates axon or dendrite morphogenesis in murine cerebellar granule cells depending on whether the co-activator CDH1 or CDH20 is recruited | 152,153 |

BMP7, bone morphogenetic protein 7 (also known as OP1); CDH, cadherin; CPEB, cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; CREST, Ca2+-responsive transactivator; DSCAM, Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule; DSCAML1, Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule-like protein 1 homologue; EPHB, ephrin receptor type B; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ESCRT, endosomal sorting complex required for transport; FMR1, fragile X mental retardation 1 protein; FRY, Furry; KIF5, kinesin-related protein 5; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; nBAF, neuron-specific BRG1-associated factor; NDR, nuclear DBF2-related; NEUROD1, neurogenic differentiation factor 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; POU, PIT1–OCT1–UNC86; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homologue; RAC, RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate; SAV, Salvador; TORC2, target of rapamycin complex 2; TRC, Tricornered; WTS, Warts.

This Review focuses on principles of dendrite morphogenesis that have primarily emerged from studies of dendritic arborization neurons in Drosophila melanogaster larvae, which we compare and contrast with studies in vertebrates. Presynaptic inputs and neuronal activity probably also influence dendrite morphogenesis — a topic that is outside the scope of this article, and reviewed elsewhere11–13.

Physiological requirements of dendrite patterns

A balance between the metabolic costs of dendrite elaboration and the need to cover the receptive field presumably determines the size and shape of dendrites14,15. Dendrites must satisfy the following physiological requirements to ensure proper neuronal function. First, a neuron’s dendrites need to cover the area (its dendritic field) that encompasses its sensory and/or synaptic inputs16,17. Second, the branching pattern and density of dendrites must be suitable for sampling and processing the signals that converge onto the dendritic field18,19. Third, dendrites need to have the flexibility for adjustment in development and in response to experience — as indicated, for example, by dynamic microtubule invasion of spines20,21, and NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor-mediated signalling that affects dendrite organization in the somatosensory cortex during development and in the mature nervous system22,23.

As different types of neurons must meet different requirements to fulfil their physiological functions, they are readily classified based on their dendritic field dimensions and dendrite branching patterns1. To consider how neurons acquire their particular dendrite morphology, we begin with recent findings about how the four classes of dendritic arborization neurons of the D. melanogaster larval peripheral nervous system (PNS) acquire their distinct dendrite morphology24,25, and discuss mechanisms that are likely to be of relevance to dendrite morphogenesis of neurons in vertebrates as well as invertebrates.

Generation of type-specific dendritic arbors

Recent genetic studies reveal a complex network of intrinsic and extrinsic regulators — namely, transcription factors and ligands for cell surface receptors, respectively — that are needed to produce the distinct dendrite morphology of the four classes of larval dendritic arborization neurons (BOX 2).

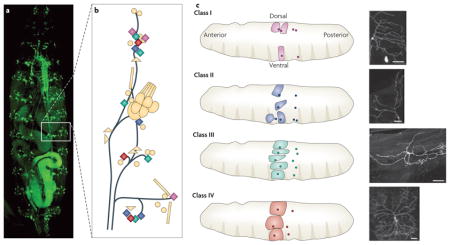

Box 2. The four classes of Drosophila melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons.

There are three class I, four class II, five class III and three class IV dendritic arborization neurons on either side of a larval abdominal segment26. Part a of the figure shows a dorsal view of a D. melanogaster larva with its dendritic arborization neurons labelled with green fluorescent protein. Part b schematically illustrates a single abdominal hemisegment, in which dendritic arborization neurons are depicted as diamonds and colour-coded according to their morphological classification. The territories (dendritic fields) of different dendritic arborization neuron classes in an abdominal hemisegment are arranged as shown in part c. The soma of the neurons are depicted as small coloured circles and their dendritic fields are indicated as shaded areas of the same colour. This pattern is repeated in each segment as exemplified by the small coloured circles in the neighbouring segment. The four classes of dendritic arborization neuron are distinguishable by their class-specific dendritic morphology: dorsal class I dendritic arborization neurons extend secondary dendrites mostly to one side of the primary dendrite, whereas class II dendritic arborization neurons have more symmetrically bifurcating dendrites. Compared with these two classes, each covering a small fraction of the body wall, class III dendritic arborization neurons have larger fields and greater branching complexity, plus the distinguishing feature of numerous spiked protrusions (dendritic spikes) that are rich in actin and lack stable microtubules. Class IV dendritic arborization neurons are the most complex in branching pattern (although they lack dendritic spikes) and achieve nearly complete coverage of the body wall. The dendrites of class III dendritic arborization neurons do not cross one another, and nor do those of class IV dendritic arborization neurons26 — a phenomenon known as tiling that allows the dendrites of a distinct type of neurons to detect incoming signals without redundancy. This phenomenon is probably important for the comprehensive and unambiguous coverage of the receptive field and is well documented in both vertebrates16,17 and invertebrates25,154. Scale bars in the right panel represent 50 μm. Part b and the left panel of part c are reproduced, with permission, from REF. 96 © Elsevier (2003). The right panel of part c is reproduced, with permission, from REF. 26 © (2002) The Company of Biologists.

These sensory neurons have become an important system for studying dendrite development because they can be readily subdivided into four classes based on dendrite complexity, dendritic-field coverage and the expression patterns of molecules that are important for dendrite morphogenesis26–32 (BOX 2; FIG. 1). Moreover, dendrite dynamics of fluorescently labelled dendritic arborization neurons can be visualized in vivo throughout larval development as they are located between the epithelium and muscle in an essentially two-dimensional array24,25. Studies that combine genetics with live imaging have facilitated the elucidation of principles of dendrite morphogenesis. Research into dendrite morphogenesis in vertebrates has yielded similar results, and therefore emerging principles are likely to be of general relevance.

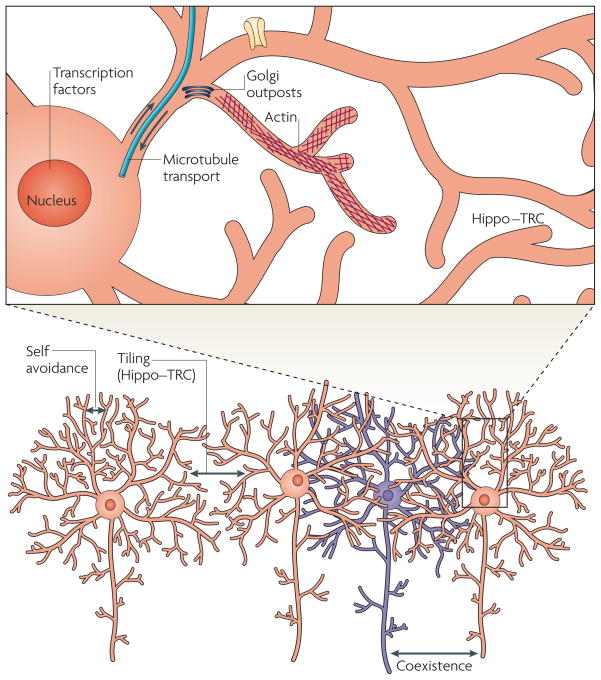

Figure 1. Mechanisms regulating the formation and organization of dendritic arbors of dendritic arborization neurons in Drosophila melanogaster.

Dendrites of the same neuron spread out by avoiding one another (self-avoidance). Moreover, dendrites of certain types of neurons such as class III and class IV dendritic arborization neurons avoid dendrites of neighbouring neurons of the same type (tiling), whereas dendrites of different neuronal types can cover the same territory (coexistence). Many factors shape the morphology of a dendritc arbor (top panel), including transcription factors, regulators of microtubules and actins (the primary cytoskeletal elements for major dendritic branches and terminal dendritic branches, respectively), Golgi outposts and signalling molecules such as Hippo and Tricornered (TRC) that mediate dendrite–dendrite interactions.

Transcription regulators of dendrite patterns

Many transcription factors contribute to the specification of neuronal type-specific dendrite patterns. A distinct dendrite morphology can be achieved by varying the levels of a single transcription factor, the specific expression of a transcription factor in a single type of neuron and combinatorial mechanisms that involve many transcription factors.

Transcription regulators of class I dendritic arborization neuron dendrite morphology

A systematic RNA interference screen has been used to identify more than 70 transcription factors that affect dendrite morphogenesis of class I dendritic arborization neurons33. One of these transcription factors, the BTB–zinc finger protein Abrupt, is expressed only in Class I dendritic arborization neurons. When Abrupt is ectopically expressed in class II, III or IV dendritic arborization neurons, it reduces their dendrite size and complexity, suggesting that it ensures the simple morphology of class I dendritic arborization neurons28,29. Future identification of genes that are downstream of Abrupt will help elucidate the mechanism underlying dendrite confinement. Moreover, larval class I dendritic arborization neurons extend secondary dendrites mostly to one side of the primary dendrite; these neurons remodel their dendrites during metamorphosis to adopt more symmetrical and complex patterns in the adult fly34. This raises fascinating questions concerning reprogramming the control of dendritic arborization.

CUT as a multi-level regulator of dendrite morphology of class II, III and IV dendritic arborization neurons

The four classes of dendritic arborization neurons express different levels of CUT, a homeodomain- containing transcription factor. Throughout embryonic and larval development, class I, II, IV and III dendritic arborization neurons have non-detectable, low, medium and high levels of CUT expression, respectively. Studies of loss-of-function mutations and class-specific overexpression of CUT show that the level of CUT expression determines the distinct patterns of dendrite branching27. A human CUT homologue, homeobox protein CUT-like 1 (CUX1; also known as CDP), can functionally substitute for D. melanogaster CUT in promoting the dendrite morphology that characterizes neurons with high levels of CUT27. Whether CUX1 is a multilevel regulator of dendrite morphology in humans is currently unknown. Apart from dendritic arborization neurons, CUT is also expressed in a subset of projection neurons in the adult D. melanogaster olfactory system and controls the targeting of their dendrites35.

Expression of Collier distinguishes class IV from class III dendritic arborization neuron dendrites

The transcription factor Collier (also known as Knot) is expressed in class IV but not in other classes of dendritic arborization neurons. In class IV dendritic arborization neurons, Collier suppresses the CUT-induced formation of actin-rich dendrite protrusions known as dendritic spikes. Co-expression of CUT and Collier ensures the correct dendrite morphogenesis of class IV dendritic arborization neurons without the formation of dendritic spikes. By contrast, class III dendritic arborization neurons express high levels of CUT but not Collier — a combination that favours the formation of dendritic spikes, which are unique to class III dendritic arborization neurons24,30–32. Thus, Collier and CUT provide an example of a combinatorial mechanism for specifying neuronal type-specific dendrite morphology.

Spineless for diversification of dendrite morphology

The D. melanogaster homologue of the mammalian aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor (AHR), Spineless, is expressed in all four classes of dendritic arborization neurons and is essential for the diversification of their dendrite patterns36. Spineless enables deviation from a common, perhaps primordial, dendrite pattern, allowing different types of dendritic arborization neurons to have distinct dendrite morphology36. Spineless might allow dendritic arborization neurons to take on specific dendrite patterns as dictated by other transcription factors and signalling molecules, perhaps analogously to its ability to endow alternative cell fate37,38.

Transcription factors for dendritic targeting of second-order olfactory neurons in D. melanogaster

Projection neurons in the olfactory system of the D. melanogaster brain express different POU (PIT1–OCT1–UNC86) homeodomain transcription factors in different cell lineages that specifically target their dendrites to intercalating but non-overlapping glomeruli39 such as ACJ6 in the anterodorsal (adPN) and Drifter in the lateral (lPN) lineage. Expression of ACJ6 in lPNs or Drifter in adPNs causes their dendrites to target inappropriate glomeruli, indicating that these transcription factors specify the projection of dendrites in the brain.

Transcription regulators of dendrite morphogenesis in mammalian neurons

The basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor Neurogenin 2 has a crucial role in the specification of dendrite morphology of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex: it promotes the outgrowth of a polarized leading process during the initiation of radial migration40. In addition, neuronal activity-dependent dendrite development is under the control of the bHLH transcription factor termed neurogenic differentiation factor 1 (NEUROD1)41, as well as Ca2+-responsive transactivator (CREST)42 and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)43,44, which respond to Ca2+ regulation. CREST, which interacts with CREB-binding protein (CBP) to regulate Ca2+-dependent dendrite growth42, is physically associated with the neuron-specific BRG1-associated factor (nBAF) chromatin remodelling complexes that distinguish neurons from neural progenitors45. D. melanogaster homologues of several subunits of nBAF complexes are important for dendrite development, underscoring their evolutionarily conserved function in regulating dendrite morphogenesis33,45.

Cell surface receptors for dendrite morphogenesis

Developing dendrites of invertebrate and vertebrate neurons are responsive to extrinsic signals that can not only stimulate or inhibit outgrowth but can also act as cues for directional growth.

The Slit ligand and Roundabout (Robo) receptor

In D. melanogaster, the Robo receptor and its ligand, Slit, which is a secreted protein, promote dendrite formation of the motor neurons RP3 and aCC46 as well as dendrite branching of the space-filling class IV dendritic arborization neurons, without affecting class I dendritic arborization neurons (BOX 2), as revealed by mutants that lack Robo24,47.

Transmembrane semaphorins may act as ligands or receptors

In the developing D. melanogaster antennal lobe, Semaphorin 1A (SEMA1A) is expressed in a graded fashion along the dendrites of projection neurons and functions as a receptor for an as yet unknown ligand that targets these dendrites to the appropriate glomeruli48,49. Interestingly, SEMA1A functions as ligand for the Plexin A receptor, mediating repulsion between axons of olfactory receptor neurons and thereby facilitating their selective targeting to the appropriate glomeruli50.

In vertebrates, the secreted form of semaphorins that are the ligands for the Plexin–Neuropilin receptors can be either chemorepellent or chemoattractant in axon guidance51 and dendrite morphogenesis24. For example, the secreted ligand SEMA3A promotes dendrite branching and spine maturation in mouse cortical neurons52. Interestingly, recent genome-wide linkage studies implicate SEMA5A as an autism susceptibility gene53.

Other cues for growth

Extrinsic factors such as neurotrophin 3, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) influence the dendrite morphology of cortical neurons54. The same neurotrophic factor can either inhibit or promote dendrite outgrowth in cortical slices, depending on the neuronal type55. Dendrite arborization of cultured sympathetic neurons can also be modulated by bone morphogenetic proteins in conjunction with NGF56. These studies illustrate the broad range of effects of diffusible or membrane-associated ligands of neuronal receptors on dendrite morphogenesis.

The cell biological basis of dendrite morphogenesis

Actin and microtubules are the major structural components that underlie dendrite morphology. Regulators of actin and microtubule dynamics therefore have important roles in dendrite morphogenesis. In addition, motors that mediate the transport of building blocks and organelles to dendrites are crucial for dendrite morphology57,58.

Multiple mechanisms of actin and microtubule regulation

The Rho family of GTPases control a wide range of cytoskeletal rearrangements that affect spine morphogenesis and the growth and branching of dendrites in both vertebrate and invertebrate neurons59–62. The small GTPase63 RHOA has opposing effects to the small GTPases RAS-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1) and CDC42 in controlling the growth and stability of actin-rich spines in mammalian neurons64. RAC1 and CDC42 activate the Arp2/3 complex, which binds to existing actin filaments and nucleates branched growth, whereas RHOA activates formins that mediate unbranched actin filament extension65. These small GTPases also influence the dynamics and plus-end capture of microtubules66.

Numerous studies suggest a key role for small GTPases in dendrite morphogenesis. In the CNS of D. melanogaster, RHOA mutant clones display excessive dendrite extension67. By contrast, loss of all three Rac homologues in central neurons of the mushroom body causes a reduction of dendrite size and complexity68. In larval class IV dendritic arborization neurons, RAC1 (REF. 69) and the actin filament-stabilizing protein tropomyosin70 are also important for dendrite growth and branching. In addition, loss of CDC42 function in neurons of the vertical system, which form part of the D. melanogaster visual system, disrupts the normal branching pattern and the tapering characteristic of dendrites of those neurons (BOX 1), and reduces the number of actin-rich spines71.

Small GTPases that modulate dendrite complexity and spine morphology are regulated by transmitters, neurotrophins and other extrinsic signals72–76. In addition, the non-canonical Wnt pathway involving catenins and Rac may promote dendrite growth and branching72,77,78. This pathway is modulated by the postsynaptic protein Shank79, as well as the origin recognition complex (ORC) that regulates dendrite branching and spine formation80. In early cortical development, coordination of radial migration of mammalian pyramidal neurons is dependent on the Rho family of small GTPases, with the leading process becoming the apical dendrite40,81.

Dendrite growth and branching also require signalling molecules, building materials and organelles such as Golgi outposts and endosomes, which are transported by molecular motors along microtubules.

Endosomes and Golgi outposts

The D. melanogaster protein Lava Lamp (LVA), a golgin coiled-coil adaptor protein, associates with the microtubule-based motor dynein–dynactin and has key roles in controlling the distribution of Golgi outposts in the dendrite as well as dendrite growth and patterning of D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons57,58,82. Reducing the level of LVA causes a shift of Golgi outposts from distal to proximal dendrites with a concomitant distal to proximal shift in dendrite branching57. Similarly, mutations in genes encoding the dynein subunits dynein light intermediate chain 2 and dynein intermediate chain result in distal to proximal shift of dendrite branching accompanied by a corresponding shift of Golgi outposts and endosomes from distal to proximal dendrites57,58.

The endocytic pathway may contribute to dendrite growth and branching by modulating signalling pathways that involve cell surface receptors that are involved in dendrite branching and patterning. RAB5, which associates with dynein and is a component of the early endocytic pathway, facilitates dendrite branching58. Moreover, the coiled-coil protein Shrub also affects dendrite branching and patterning in D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons83. Shrub is a homologue of the yeast protein Snf7, an essential component of the endosomal sorting complex that is required for the formation of endosomal compartments known as multivesicular bodies. It therefore seems that multivesicular bodies may have a role in dendrite morphogenesis is unknown.

Microtubule-dependent transport of endosomes and Golgi outposts to the dendrite57,58 is important for den-drite arborization of both vertebrate and invertebrate neurons82,84. In D. melanogaster, dendrite growth and branching of central neurons in the mushroom body is reduced by mutations of dynein subunits or LIS1, a dynein-interacting protein associated with lissencephaly85–88. In heterozygous LIS1-mutant mice, dendrites of heterotopic pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus show reduced dendrite length and branching compared with those of wild-type mice89. Therefore, compromised microtubule-dependent transport could be the cause of some neurological disorders.

Control of dendrite morphogenesis by proteins at the synapse

Postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95), a scaffold protein that contains multiple PDZ domains and is localized at the postsynaptic density (PSD), acts in a neuronal activity-independent manner and suppresses dendrite branching locally, possibly by altering microtubule organization90. Another multi-PDZ domain scaffold protein located within the PSD, glutamate receptor interaction protein 1 (GRIP1), functions as an adaptor for the microtubule-based motor kinesin-related protein 5 to facilitate trafficking of the receptor tyrosine kinase ephrin type B receptor 2 (REF. 91). These studies provide interesting examples of the ability of scaffold proteins at the PSD to coordinate both dendrite morphology and synaptic function.

Dendrite versus axon morphogenesis

Golgi outposts

In D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons and cultured hippocampal neurons, Golgi outposts reside in dendrites but not in axons and are often found at branch points of dendritic arbors82,84,92,93, suggesting that Golgi outposts serve as local stations to supply or recycle membrane to and from nearby dendritic branches. Indeed, in D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons, the direction of transport of Golgi outposts — towards or away from the neuronal soma — correlates with dendrite branch dynamics. Moreover, local damage to Golgi outposts reduces branch dynamics of dendritic arborization neurons82. Similarly, disruption of post-Golgi trafficking halts dendrite growth in developing hippocampal neurons and decreases the overall length of dendrites in more mature neurons84,92.

Genes essential for dendrite but not axon development

A group of dendritic arborization reduction (dar) genes identified in a D. melanogaster mutant screen affect the morphogenesis of dendrites but not axons of dendritic arborization neurons82. Similar to the D. melanogaster dar-mutant phenotypes82, knockdown of NEUROD1 in mammalian cerebellar granule cells reduces the length of dendrites without affecting axon development41.

Five dar genes have so far been identified. dar5 encodes a transferin-like factor and functions non-cell autonomously, whereas the other four function cell autonomously and regulate dendrite growth, as determined by studies using MARCM (mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker)94. dar1 encodes a novel krüppel family transcription factor, the mammalian homologue of which is krüppel-like factor 7. The other three genes, dar2, dar3 and dar6, are the D. melanogaster homologues of the yeast genes SEC23, SAR1 and RAB1, respectively82. The three proteins encoded by these genes are crucial regulators of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to Golgi transport mediated by coat protein complex II vesicles95. Compromised ER to Golgi transport affects dendrite, but not axon, growth of D. melanogaster and mammalian neurons during active growth, thus revealing an evolutionarily conserved difference between the growth of dendrites and axons in their sensitivity to a limited membrane supply from the secretory pathway82.

Dendrite morphogenesis entails not only the specification of dendrite patterns of individual neurons by transcription factors, cell surface receptors and other cell biological mechanisms, but also coordination between neurons for the correct organization of their respective dendritic fields, as discussed in the following section.

Relative organization of dendritic fields

At least three mechanisms contribute to the organization of dendritic fields: self-avoidance, tiling and coexistence. Dendrites of the same neuron avoid one another (self-avoidance). Dendrites of certain types of neurons — such as certain amacrine cells and retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in vertebrates, and class III and class IV dendritic arborization neurons in D. melanogaster — avoid one another (tiling). Self-avoidance and tiling presumably ensure efficient and unambiguous coverage of the receptive field. Furthermore, dendrites of different neuronal types can cover the same region (coexistence)96,97 allowing the sampling of different types of information from the same receptive field. These three principles for organizing dendrites rely on different molecular mechanisms.

As summarized below, the immense diversity of D. melanogaster Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (DSCAM) splice variants and the stochastic expression of a small subset of such isoforms in each dendritic arborization neuron ensure self-avoidance without compromising coexistence; mammalian DSCAM also mediates self-avoidance, indicating conservation of the function of this protein across species98.

DSCAM is important for dendrite self-avoidance and coexistence

DSCAM was originally identified as an axon guidance receptor. Extensive alternative splicing can potentially generate over 38,000 isoforms99. The stochastic expression of a small subset of DSCAM iso-forms in each neuron mediates neurite self-recognition by isoform-specific homophilic binding100; neurites that express the same set of isoforms or the same, single isoform repel each other, resulting in self-avoidance. As neighbouring neurons are unlikely to express the same set of DSCAM isoforms101–103, expression of this protein enables the coexistence of axons and dendrites in many D. melanogaster neurons including mushroom body neurons104 and projection neurons in the antennal lobe105. DSCAMs also have a role in circuit formation that is discussed in several recent reviews106–108.

Is DSCAM-mediated dendrite organization applicable to other species?

There are two mouse DSCAM homologues, DSCAM and DSCAML1, that are both expressed in the developing retina in largely non-overlapping patterns: DSCAM is expressed in essentially all RGCs and subsets of amacrine cells whereas DSCAML1 is expressed in rods, bipolar cells and different subsets of amacrine cells. Similar to D. melanogaster DSCAM, both mouse homologues play a part in self-avoidance98,109. In mutant mice lacking either DSCAM or DSCAML1, the dendrites of retinal neurons that normally express the respective gene aggregate with one another but not with dendrites of different cell subtypes109. This has led to the proposal that vertebrate DSCAMs prevent adhesion possibly by serving as ‘non-stick coating’ that masks the cell type-intrinsic adhesive cues109, in contrast to the active repulsive role of D. melanogaster DSCAM. Another important difference is that murine DSCAMs do not undergo extensive alternative splicing to generate a large number of isoforms. Thus, unlike D. melanogaster DSCAM, murine DSCAMs cannot function as a ‘bar code’ to endow each neuron with a unique identity to prevent inappropriate repulsion.

Interestingly, DSCAM function between species is diverse. DSCAM not only mediates homotypic repulsion but also homotypic adhesion, such as controlling the layer-specific synapse formation in the chick retina110 and trans-synaptic interactions involved in synapse remodelling in Aplysia californica111 — functions that are not shared by murine DSCAMs109. Furthermore, DSCAM also functions as a Netrin receptor and therefore has a role in axon guidance in D. melanogaster as well as vertebrates112–114.

These differences should be considered when addressing the question of how the vertebrate nervous system organizes its dendrites. One possibility is that there is a molecule in vertebrates that functions in the same manner as DSCAM in D. melanogaster. However, blocks of tandemly arranged alternative exons similar to those of D. melanogaster DSCAM have not yet been found in vertebrates. Another possibility is that combinatorial use of families of moderately diverse recognition molecules in vertebrates (such as immunoglobulins), rather than extensive alternative splicing of DSCAM106, might generate sufficient diversity to allow self-avoidance of similar dendrites and coexistence of different dendrites. A variation of this model is that DSCAM may function as part of a receptor complex that could contain different combinations of diverse co-receptors in vertebrates107. However, the strategy by which dendrites are organized in vertebrates may be entirely different; further studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Dendritic tiling

Tiling of axonal terminals or dendritic arbors has been observed in many invertebrates and vertebrates17,26,115–119. Dendrites of different types of neurons, such as the four classes of D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons26 and the more than 50 types of neurons in the mammalian retina120, show considerable variations in their tiling behaviour: some types of neurons do not show tiling, whereas others do. One common tiling mechanism involves homotypic dendrite–dendrite (or neurite–neurite) repulsion between neurons of the same type. This has been observed in the mammalian retina121, the sensory arbors that innervate the skin of the frog122, zebrafish118 and leech116, and D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons96,97. In these studies, ablation of a neuron resulted in the invasion of the vacated area by neurites of adjacent neurons of the same type.

Although the signals that mediate dendritic tiling in D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons remain largely unknown, two intracellular signalling molecules were identified several years ago: Tricornered (TRC), a kinase of the NDR family; and a positive regulator of TRC encoded by the furry (fry) gene123 (FIG. 2). In trc or fry mutants, class IV dendritic arborization dendrites no longer show their characteristic turning or retracting response when they encounter dendrites of neighbouring class IV dendritic arborization neurons, resulting in extensive overlap of their dendrites and therefore loss of tiling123. Recently, mutations of several genes of the target of rapamycin complex 2 (TORC2) including sin1, rapamycin-insensitive companion of Tor (rictor) and Tor were found to cause tiling phenotypes similar to that of trc mutants. TORC2 components associate physically with the TRC protein and their respective genes interact, suggesting that these proteins act in the same pathway that regulates tiling124.

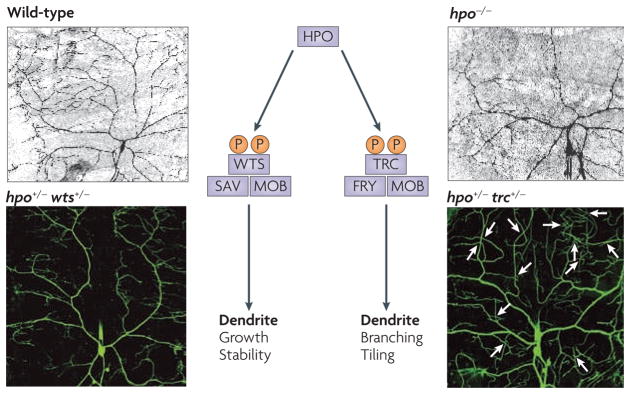

Figure 2. The Hippo pathway coordinates the tiling and maintenance of dendritic fields of Drosophila melanogaster class IV dendritic arborization neurons.

The serine–threonine kinase Hippo (HPO) regulates Tricornered (TRC) and Warts (WTS), the only members of the NDR (nuclear DBF2-related) family of kinases in D. melanogaster. TRC and its positive cofactor (Furry) FRY regulate tiling (arrows in the lower right panel indicate dendrite crossover, a tiling defect) whereas WTS and its positive cofactor Salvador (SAV) regulate maintenance. MOB is a shared cofactor. Images are reproduced, with permission, from REF. 147 © (2006). Macmillan Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

However, there is also evidence for dendritic tiling mechanisms other than dendrite–dendrite repulsion. Dendrites of Caenorhabditis elegans mechanosensory neurons overlap transiently in early development, and the overlap is later eliminated. Interestingly, SAX-1 and SAX-2 — which are the homologues of TRC and FRY, respectively125 — are required for tiling of these neurons, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role of these proteins. In addition, the dendrites of D. melanogaster motor neurons do not seem to rely on homotypic repulsion for their placement; these dendrites map myotopically along the antero-posterior axis and the medio-lateral axis, directed by guidance cues and their respective receptors such as Slit–Robo and Netrin–Frazzled for dendritic targeting117,126–128. Certain types of RGC, such as those expressing melanopsin, show tiling in the mammalian retina. In mice with loss-of-function mutations in the transcription factors POU class 4 homeobox 2 (also known as BRN3B) or protein atonal homologue 7 (also known as MATH5), the number of melanopsin-expressing RGCs is greatly reduced, resulting in incomplete tiling in the retina. Nonetheless, the remaining neurons are regularly spaced and normal dendrite size is maintained in the absence of dendrite–dendrite contact of neurons of the same type, suggesting that homotypic repulsion is not required for tiling129. However, caution should be taken when extrapolating from these observations in mutant retinas to the wild-type retina.

Transient tiling may have escaped notice in some cases. Indeed, imaging of the developing mouse retina reveals that the horizontal cells elaborate transient neurites that tile through homotypic interaction130. However, the mature horizontal cell dendrites overlap substantially (a phenomenon known as shingling)108. Therefore, transient tiling provides a mechanism for producing a non-random distribution of cells that are not sharply divided from one another.

It is also noteworthy that the assessment of tiling requires accurate classification of cell types. If different types of neurons are analysed together owing to a lack of appropriate markers or phenotype information, their overlapping dendrites could mask the tiling phenomenon. Therefore, future studies that distinguish between cell types might reveal more neuronal types that undergo tiling.

Dendrite growth, scaling and maintenance

The size of dendritic arbors increases in proportion to animal growth, a phenomenon known as dendritic scaling. The final size of a dendritic arbor, once reached, is maintained throughout the lifetime of the neuron.

Dendritic scaling

Dendrites of D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons first exhibit rapid growth in mid embryogenesis, to ‘catch up’ with body growth. This is followed by dendritic scaling in later larval stages, to match dendrite growth precisely with larval body growth — a tripling in body length over only 3 days131. Recently, some progress has been made in uncovering the mechanisms underlying dendritic scaling of D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons131. Dendritic scaling of class III and class IV dendritic arborization neurons is ensured by signalling from the overlying epithelial cells, which express the microRNA bantam. This microRNA inhibits the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) kinase pathway in dendritic arborization neurons, limiting their dendrite growth131 (discussed below). Class I dendritic arborization neurons also exhibit precise dendritic scaling, although with a different time course and involving distinct and as yet unknown mechanisms.

Whereas some neurons such as the mammalian cerebellar granule cells do not alter their dendrites extensively during later stages of development, the dendrite size and complexity of other neurons such as Purkinje neurons grow in proportion to the animal’s growth. Between these extremes is the intriguing example of how RGCs adjust to growth in the goldfish132. Two mechanisms operate in a compromise strategy: first, the number of RGCs increases during fish growth (similar to increasing the number of pixels in a camera), which improves visual resolution; second, arbor size increases in proportion to the square root of the diameter of the retina, increasing the accuracy with which light intensity can be detected. With this combination strategy, the fish achieves intermediary gains both in resolution and sensitivity, and so its ability to detect small objects increases with age and size132. Thus, different types of neurons may scale their dendrites in different ways depending on their functional requirements.

Once neuronal dendrites are sufficiently large to cover the dendritic field of the full-grown animal, it is important that dendritic coverage is maintained25. The molecular control of dendritic growth, scaling and maintenance is only beginning to be understood. Recently, kinase cascades131,133–136 and local translation in dendrites137–139 have been shown to be important for the control of dendrite size of certain mammalian neurons as well as D. melanogaster neurons.

Dendrite size control

The PI3K–mTOR kinase pathway, which is well known for its role in controlling cell size, has been shown to regulate dendrite size133,134. In addition, this pathway acts together with the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase cascade to regulate dendrite complexity and branching pattern133. BDNF activates both PI3K–mTOR and MAPK pathways, and hence induces primary dendrite formation135. The PI3K–mTOR pathway also acts downstream of Reelin, a secreted glycoprotein that regulates dendrite growth and branching of hippocampal neurons136.

In addition to the cellular machinery of dendrite growth discussed above (including the secretory pathway, endocytic pathway and cytoskeletal elements), local regulation of translation also has a role in controlling dendritic arborization140. For example, the RNA-binding proteins Pumilio and Nanos, which were initially identified for their involvement in targeting specific mRNA to the posterior end of D. melanogaster embryos and repressing the translation of as yet unlocalized mRNA, are important for dendrite morphogenesis of the space-filling class III and class IV dendritic arborization neurons but not the class I or class II dendritic arborization neurons with simpler dendrite patterns137. Moreover, following the initial elaboration of dendrites, maintenance or further extension of dendrite branches of class IV dendritic arborization neurons in larvae in the late third instar developmental stage requires dendritic targeting of nanos mRNA as well as its translation regulation by Glorund and Smaug — RNA-binding proteins that recognize the stem loops in the 3′ untranslated region of nanos mRNA138. Similarly, a mouse homologue of Staufen, another RNA-binding protein involved in anterior–posterior body patterning in D. melanogaster embryos, is important for dendritic targeting of ribonucleoprotein particles and dendrite branching139. In addition, the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein, which has been shown to have a role in mRNA trafficking and translation regulation, is implicated in experience-dependent dendrite growth in the developing frog visual system141.

Dendrite maintenance

Little is known about the mechanisms that are responsible for dendrite maintenance. Extended time-lapse analyses of mouse cortical neurons have revealed that, following a period of juvenile plasticity during which neurons establish normal dendritic fields, dendrites become stable with most neurons maintaining their dendritic fields for the remainder of their lifespan23,142–144.

Hippo, a kinase of the STE20 family, is a major regulator of organ size in flies and mammals145 and has recently emerged as an important regulator of dendrite maintenance for D. melanogaster class IV dendritic arborization neurons (FIG. 2). The core of the Hippo pathway is a kinase cascade: Hippo, together with the positive regulator Salvador (SAV), phosphorylates and thereby activates Warts (WTS), a kinase of the NDR (nuclear DBF2-related) family. This core complex inhibits genes including the Polycomb group (PcG) genes, which encode components of the Polycomb repressor complexes for transcriptional silencing. Mutation of PcG genes produces phenotypes of impaired dendrite maintenance146 similar to those caused by mutation of the core complex of the Hippo pathway. Moreover, trans-heterozygous flies carrying one mutant copy of a PcG gene and one mutant copy of a Hippo core complex gene display the same dendrite phenotype: the dendrites initially grow and tile normally, but the dendritic fields are not maintained, leading to progressive loss of dendrite branches and large gaps in the dendritic field146,147. Whereas complete loss of function of these genes may cause lethality owing to their role in early development, mosaic analyses reveal that neurons carrying one mutant allele of each of two such interacting genes display profound alterations in dendrite size and maintenance. Every pair of Hippo pathway and/or PcG mutants tested so far has produced abnormal dendrite phenotypes146,147.

In D. melanogaster, TRC and WTS are the only two members of the serine–threonine protein kinases of the NDR family and SAV and FRY are their respective positive regulators. TRC–FRY regulate tiling whereas WTS–SAV regulate maintenance147. Both pairs are also under the regulation of Hippo. Thus, the Hippo pathway coordinates the tiling and maintenance of dendritic fields (FIG. 2).

Questions for future studies

As summarized in this Review and in TABLE 1, recent studies reveal a complex control of dendrite pattern, size and maintenance involving various transcription factors, cell surface receptors, signalling cascades, regulators of cytoskeletal elements, and the secretory and endocytic pathways. In addition, dendrite morphology is modulated by signalling with other neurons as well as other cell types. Although we are still far from having a coherent mechanistic understanding, much of the progress made to date has been due to the identification of genes involved in dendrite morphogenesis that has allowed the formulation of more precise questions.

Many questions await further studies, including how dendrites signal to one another during tiling and how dendrite growth is coordinated to match body growth. In addition, because dendrites are highly compartmentalized, an important area of research is the regulation of the expression and dendritic localization of various signalling molecules. Molecular and cellular analyses of dendrite patterning, pruning and maintenance may also provide clues as to whether some mental disorders involve dysregulation of dendrite morphogenesis or maintenance, as discussed below.

Trans-heterozygosity could cause mental disorders

Studies of the mechanisms controlling dendrite formation, maintenance and pruning of D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons25 have identified an unexpectedly large number (probably more than 100) of genes146,147 (TABLE 1). Abnormalities in dendrite growth or pruning could contribute to mental disorders such as autism, which manifests in early childhood, and schizophrenia, which develops in late adolescence, both of which are heritable mental disorders with a largely unknown genetic basis (BOX 3). Genetic studies of dendrite morphogenesis and maintenance may therefore suggest possible mediators of these diseases. These complex mental disorders are likely to be large conglomerates of rare and genetically diverse diseases. The trans-heterozygous combination of mutations of two genes that individually (in heterozygotes) do not have a discernable effect on phenotype could compromise dendrite morphogenesis and result in mental disorders. A strong interaction between two gene products in the same pathway is evident when a reduction in the activity of both — but not of either one alone — results in mutant phenotypes, as is the case for genes of the Hippo pathway and Polycomb group that have key roles for dendrite stability146,147. It would be interesting to test whether trans-heterozygous mutant combinations in humans (either transmitted from parents or de novo mutations) could be the cause of some of the mental disorders that have a complex genetic basis. With current technologies, it is challenging to conduct genome-wide association studies of interacting genes that, in combination, cause mental disorders. It is more practical to attempt deep sequencing to look for mutations of human candidate genes that are homologous to those identified through genetic studies of dendrite morphogenesis in D. melanogaster. These studies should aim to identify alterations of these genes that, alone or in combination, associate with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism and schizophrenia.

Box 3. Dendrite abnormalities in human diseases.

Human cortical neurons start growing dendrites soon after they have entered their destined cortical layer155. With the arrival of thalamic or cortical afferent fibres and the expression of NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate) receptors, pyramidal neurons undergo a second phase of dendrite branching and extension until the third postnatal month156. Whereas layer V pyramidal neurons in the prefrontal cortex reach peak dendrite complexity between the third and sixteenth postnatal months, layer IIIC pyramidal neurons seem dormant during this period, and resume dendrite growth over the next 14 months156. The number of synapses and spines also approaches a maximum in early childhood, followed by synaptic pruning in adolescence10. Intriguingly, intellectual ability seems to correlate with an accelerated and prolonged increase of cortical thickness in childhood followed by equally vigorous cortical thinning in adolescence157. As discussed below, dendrite development shows strong temporal correlation with the emergence of behavioural symptoms of several mental disorders.

Mental disorders such as autism3–5 and Rett’s syndrome7 are often associated with abnormal brain size, suggesting overgrowth or lack of dendrite pruning as well as alterations of neuronal number during development. The emergence of behavioural symptoms in the first 3 years of life further begs the question whether abnormal dendrite morphogenesis contributes to these neurodevelopmental disorders. Single gene mutations linked to diseases such as Rett’s syndrome, Angelman’s syndrome, tuberous sclerosis and fragile X syndrome are known to greatly increase the risk for autism. However, the genetic underpinning of autism remains elusive in most cases despite the high heritability4,10,53,158.

In contrast to mental disorders with early manifestation of macrocephaly and behavioural symptoms, which may arise from overgrowth or lack of dendrite pruning in early childhood, schizophrenia could arise from over-pruning or failed maintenance of dendrites later in life. Notably, recent MRI studies reveal progressive grey-matter loss before and during psychosis development in schizophrenia in late adolescence, suggesting synaptic over-pruning9,159. Despite the heritability of schizophrenia160 and associated progressive brain volume changes161, and the linkage of schizophrenia to mutations of neuregulin 1 and its receptor159,162, the genetic basis for schizophrenia remains largely unknown163.

Acknowledgments

We are Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigators and our research is supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, USA.

- Dendritic field

The region occupied by the dendrites of a neuron that determines the extent of sensory or synaptic inputs to the neuron

- Plus-end capture

Stabilization of rapidly growing microtubules through interaction with their plus end

- Origin recognition complex

A molecular switch that controls the replication initiation machinery to ensure genome duplication during cell division

- Golgi outposts

Golgi cisternae that often reside in the dendrites

- Lissencephaly

Human neuron migration disorders that primarily affect the development of the cerebral cortex

- MARCM

(Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker). A sophisticated genetic technique using GAL80 that allows single (wild-type or mutant) neurons to be labelled

- Instar

A developmental stage of the larva

- Trans-heterozygous

Describes an animal that harbours one mutant allele of gene A and one mutant allele of gene B

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATABASES

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene

fry | trc

OMIM: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim

Angelman’s syndrome | autism | Down’s syndrome | fragile X syndrome | Rett’s syndrome | schizophrenia

UniProtKB: http://www.uniprot.org

Abrupt | CDC42 | Collier | CUT | CUX1 | DSCAM | DSCAML1 | Hippo | LIS1 | LVA | NEUROD1 | RAC1 | RHOA | SAV | SEMA1A | Shrub | Spineless | TRC | WTS

FURTHER INFORMATION

Lily and Yuh-Nung Jan’s homepage: http://physio.ucsf.edu/jan/

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

References

- 1.Ramon y Cayal S. In: Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrate. Swanson N, Swanson LW, translators. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufmann WE, Moser HW. Dendritic anomalies in disorders associated with mental retardation. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:981–991. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardo CA, Eberhart CG. The neurobiology of autism. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:434–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh CA, Morrow EM, Rubenstein JL. Autism and brain development. Cell. 2008;135:396–400. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelleher RJ, III, Bear MF. The autistic neuron: troubled translation? Cell. 2008;135:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagni C, Greenough WT. From mRNP trafficking to spine dysmorphogenesis: the roots of fragile X syndrome. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:376–387. doi: 10.1038/nrn1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramocki MB, Zoghbi HY. Failure of neuronal homeostasis results in common neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Nature. 2008;455:912–918. doi: 10.1038/nature07457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dindot SV, Antalffy BA, Bhattacharjee MB, Beaudet AL. The Angelman syndrome ubiquitin ligase localizes to the synapse and nucleus, and maternal deficiency results in abnormal dendritic spine morphology. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:111–118. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garey LJ, et al. Reduced dendritic spine density on cerebral cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1998;65:446–453. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourgeron T. A synaptic trek to autism. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong RO, Ghosh A. Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic growth and patterning. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:803–812. doi: 10.1038/nrn941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bestman J, Silva JSD, Cline HT. In: Dendrites. Stuart G, Spruston N, Häusser M, editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. pp. 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polleux F, Ghosh A. In: Dendrites. Stuart G, Spruston N, Häusser M, editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen Q, Chklovskii DB. A cost-benefit analysis of neuronal morphology. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:2320–2328. doi: 10.1152/jn.00280.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shepherd GM, Stepanyants A, Bureau I, Chklovskii D, Svoboda K. Geometric and functional organization of cortical circuits. Nature Neurosci. 2005;8:782–790. doi: 10.1038/nn1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wassle H, Boycott BB. Functional architecture of the mammalian retina. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:447–480. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacNeil MA, Masland RH. Extreme diversity among amacrine cells: implications for function. Neuron. 1998;20:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Losonczy A, Makara JK, Magee JC. Compartmentalized dendritic plasticity and input feature storage in neurons. Nature. 2008;452:436–441. doi: 10.1038/nature06725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spruston N. Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:206–221. doi: 10.1038/nrn2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu X, Viesselmann C, Nam S, Merriam E, Dent EW. Activity-dependent dynamic microtubule invasion of dendritic spines. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13094–13105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3074-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaworski J, et al. Dynamic microtubules regulate dendritic spine morphology and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2009;61:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espinosa JS, Wheeler DG, Tsien RW, Luo L. Uncoupling dendrite growth and patterning: single-cell knockout analysis of NMDA receptor 2B. Neuron. 2009;62:205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holtmaat A, Svoboda K. Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:647–658. doi: 10.1038/nrn2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corty MM, Matthews BJ, Grueber WB. Molecules and mechanisms of dendrite development in Drosophila. Development. 2009;136:1049–1061. doi: 10.1242/dev.014423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parrish JZ, Emoto K, Kim MD, Jan YN. Mechanisms that regulate establishment, maintenance, and remodeling of dendritic fields. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:399–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grueber WB, Jan LY, Jan YN. Tiling of the Drosophila epidermis by multidendritic sensory neurons. Development. 2002;129:2867–2878. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grueber WB, Jan LY, Jan YN. Different levels of the homeodomain protein cut regulate distinct dendrite branching patterns of Drosophila multidendritic neurons. Cell. 2003;112:805–818. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00160-0. This study showed that each of the four levels of CUT expression confers a distinct dendritic branching pattern in D. melanogaster dendritic arborization neurons. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugimura K, Satoh D, Estes P, Crews S, Uemura T. Development of morphological diversity of dendrites in Drosophila by the BTB-zinc finger protein abrupt. Neuron. 2004;43:809–822. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li W, Wang F, Menut L, Gao FB. BTB/POZ-zinc finger protein abrupt suppresses dendritic branching in a neuronal subtype-specific and dosage-dependent manner. Neuron. 2004;43:823–834. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jinushi-Nakao S, et al. Knot/Collier and cut control different aspects of dendrite cytoskeleton and synergize to define final arbor shape. Neuron. 2007;56:963–978. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hattori Y, Sugimura K, Uemura T. Selective expression of Knot/Collier, a transcriptional regulator of the EBF/Olf-1 family, endows the Drosophila sensory system with neuronal class-specific elaborated dendritic patterns. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1011–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crozatier M, Vincent A. Control of multidendritic neuron differentiation in Drosophila: the role of Collier. Dev Biol. 2008;315:232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parrish JZ, Kim MD, Jan LY, Jan YN. Genome-wide analyses identify transcription factors required for proper morphogenesis of Drosophila sensory neuron dendrites. Genes Dev. 2006;20:820–835. doi: 10.1101/gad.1391006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams DW, Truman JW. Remodeling dendrites during insect metamorphosis. J Neurobiol. 2005;64:24–33. doi: 10.1002/neu.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komiyama T, Luo L. Intrinsic control of precise dendritic targeting by an ensemble of transcription factors. Curr Biol. 2007;17:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim MD, Jan LY, Jan YN. The bHLH-PAS protein Spineless is necessary for the diversification of dendrite morphology of Drosophila dendritic arborization neurons. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2806–2819. doi: 10.1101/gad.1459706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wernet MF, et al. Stochastic spineless expression creates the retinal mosaic for colour vision. Nature. 2006;440:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature04615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang X, Powell-Coffman JA, Jin Y. The AHR-1 aryl hydrocarbon receptor and its co-factor the AHA-1 aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator specify GABAergic neuron cell fate in C. elegans. Development. 2004;131:819–828. doi: 10.1242/dev.00959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komiyama T, Johnson WA, Luo L, Jefferis GS. From lineage to wiring specificity. POU domain transcription factors control precise connections of Drosophila olfactory projection neurons. Cell. 2003;112:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hand R, et al. Phosphorylation of Neurogenin2 specifies the migration properties and the dendritic morphology of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex. Neuron. 2005;48:45–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaudilliere B, Konishi Y, de la Iglesia N, Yao G, Bonni A. A CaMKII-NeuroD signaling pathway specifies dendritic morphogenesis. Neuron. 2004;41:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aizawa H, et al. Dendrite development regulated by CREST, a calcium-regulated transcriptional activator. Science. 2004;303:197–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1089845. This paper documents the identification of CREST as a key mediator of activity-dependent dendritic growth. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wayman GA, et al. Activity-dependent dendritic arborization mediated by CaM-kinase I activation and enhanced CREB-dependent transcription of Wnt-2. Neuron. 2006;50:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Redmond L, Kashani AH, Ghosh A. Calcium regulation of dendritic growth via CaM kinase IV and CREB-mediated transcription. Neuron. 2002;34:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu JI, et al. Regulation of dendritic development by neuron-specific chromatin remodeling complexes. Neuron. 2007;56:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.021. A demonstration of the essential role of the neuron-specific chromatin remodelling complex in activity-dependent dendritic development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furrer MP, Vasenkova I, Kamiyama D, Rosado Y, Chiba A. Slit and Robo control the development of dendrites in Drosophila CNS. Development. 2007;134:3795–3804. doi: 10.1242/dev.02882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dimitrova S, Reissaus A, Tavosanis G. Slit and Robo regulate dendrite branching and elongation of space-filling neurons in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2008;324:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Komiyama T, Sweeney LB, Schuldiner O, Garcia KC, Luo L. Graded expression of semaphorin-1a cell-autonomously directs dendritic targeting of olfactory projection neurons. Cell. 2007;128:399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo L, Flanagan JG. Development of continuous and discrete neural maps. Neuron. 2007;56:284–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sweeney LB, et al. Temporal target restriction of olfactory receptor neurons by Semaphorin-1a/PlexinA-mediated axon-axon interactions. Neuron. 2007;53:185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishiyama M, et al. Cyclic AMP/GMP-dependent modulation of Ca2+ channels sets the polarity of nerve growth-cone turning. Nature. 2003;423:990–995. doi: 10.1038/nature01751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morita A, et al. Regulation of dendritic branching and spine maturation by semaphorin3A-Fyn signaling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2971–2980. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5453-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss LA, Arking DE. Gene Discovery Project of Johns Hopkins and the Autism Consortium, Daly, M. J. & Chakravarti, A. A genome-wide linkage and association scan reveals novel loci for autism. Nature. 2009;461:802–808. doi: 10.1038/nature08490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McAllister AK, Lo DC, Katz LC. Neurotrophins regulate dendritic growth in developing visual cortex. Neuron. 1995;15:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McAllister AK, Katz LC, Lo DC. Opposing roles for endogenous BDNF and NT-3 in regulating cortical dendritic growth. Neuron. 1997;18:767–778. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lein P, Johnson M, Guo X, Rueger D, Higgins D. Osteogenic protein-1 induces dendritic growth in rat sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1995;15:597–605. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng Y, et al. Dynein is required for polarized dendritic transport and uniform microtubule orientation in axons. Nature Cell Biol. 2008;10:1172–1180. doi: 10.1038/ncb1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Satoh D, et al. Spatial control of branching within dendritic arbors by dynein-dependent transport of Rab5-endosomes. Nature Cell Biol. 2008;10:1164–1171. doi: 10.1038/ncb1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newey SE, Velamoor V, Govek EE, Van Aelst L. Rho GTPases, dendritic structure, and mental retardation. J Neurobiol. 2005;64:58–74. doi: 10.1002/neu.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen H, Firestein BL. RhoA regulates dendrite branching in hippocampal neurons by decreasing cypin protein levels. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8378–8386. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0872-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sfakianos MK, et al. Inhibition of Rho via Arg and p190RhoGAP in the postnatal mouse hippocampus regulates dendritic spine maturation, synapse and dendrite stability, and behavior. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10982–10992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0793-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leemhuis J, et al. Rho GTPases and phosphoinositide 3-kinase organize formation of branched dendrites. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:585–596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luo L. Actin cytoskeleton regulation in neuronal morphogenesis and structural plasticity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:601–635. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.031802.150501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tada T, Sheng M. Molecular mechanisms of dendritic spine morphogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chhabra ES, Higgs HN. The many faces of actin: matching assembly factors with cellular structures. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee T, Winter C, Marticke SS, Lee A, Luo L. Essential roles of Drosophila RhoA in the regulation of neuroblast proliferation and dendritic but not axonal morphogenesis. Neuron. 2000;25:307–316. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ng J, et al. Rac GTPases control axon growth, guidance and branching. Nature. 2002;416:442–447. doi: 10.1038/416442a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee A, et al. Control of dendritic development by the Drosophila fragile X-related gene involves the small GTPase Rac1. Development. 2003;130:5543–5552. doi: 10.1242/dev.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li W, Gao FB. Actin filament-stabilizing protein tropomyosin regulates the size of dendritic fields. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6171–6175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06171.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scott EK, Reuter JE, Luo L. Small GTPase Cdc42 is required for multiple aspects of dendritic morphogenesis. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3118–3123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03118.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosso SB, Sussman D, Wynshaw-Boris A, Salinas PC. Wnt signaling through Dishevelled, Rac and JNK regulates dendritic development. Nature Neurosci. 2005;8:34–42. doi: 10.1038/nn1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schubert V, Dotti CG. Transmitting on actin: synaptic control of dendritic architecture. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:205–212. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Penzes P, Cahill ME, Jones KA, Srivastava DP. Convergent CaMK and RacGEF signals control dendritic structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Konur S, Ghosh A. Calcium signaling and the control of dendritic development. Neuron. 2005;46:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yoshihara Y, De Roo M, Muller D. Dendritic spine formation and stabilization. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yu X, Malenka RC. β-catenin is critical for dendritic morphogenesis. Nature Neurosci. 2003;6:1169–1177. doi: 10.1038/nn1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peng YR, et al. Coordinated changes in dendritic arborization and synaptic strength during neural circuit development. Neuron. 2009;61:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Quitsch A, Berhorster K, Liew CW, Richter D, Kreienkamp HJ. Postsynaptic shank antagonizes dendrite branching induced by the leucine-rich repeat protein Densin-180. J Neurosci. 2005;25:479–487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2699-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang Z, Zang K, Reichardt LF. The origin recognition core complex regulates dendrite and spine development in postmitotic neurons. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:527–535. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Olson EC, Kim S, Walsh CA. Impaired neuronal positioning and dendritogenesis in the neocortex after cell-autonomous Dab1 suppression. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1767–1775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3000-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ye B, et al. Growing dendrites and axons differ in their reliance on the secretory pathway. Cell. 2007;130:717–729. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.032. The authors identified the dar genes and Golgi outposts as key factors that are required for dendritic but not axonal growth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sweeney NT, Brenman JE, Jan YN, Gao FB. The coiled-coil protein shrub controls neuronal morphogenesis in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1006–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Horton AC, et al. Polarized secretory trafficking directs cargo for asymmetric dendrite growth and morphogenesis. Neuron. 2005;48:757–771. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.005. This study showed the important role of Golgi outposts in the dendritic development of cultured hippocampal neurons. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reuter JE, et al. A mosaic genetic screen for genes necessary for Drosophila mushroom body neuronal morphogenesis. Development. 2003;130:1203–1213. doi: 10.1242/dev.00319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu Z, Steward R, Luo L. Drosophila Lis1 is required for neuroblast proliferation, dendritic elaboration and axonal transport. Nature Cell Biol. 2000;2:776–783. doi: 10.1038/35041011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]