Abstract

We report the first inert gas sensing and characterization studies based on high resolution-localized surface plasmon resonance (HR-LSPR) spectroscopy. HR-LSPR was used to detect the extremely small change (< 3 × 10−4) in bulk refractive index (RI) between He (g) and Ar (g) or He (g) and N2 (g). We also demonstrate sub-monolayer sensitivity to adsorbed water from exposure of the sensor to air (40% humidity) vs. dry N2 (g). These measurements significantly expand the applications space and characterization tools for plasmonic nanosensors.

The development of high resolution-localized surface plasmon resonance (HR-LSPR) spectroscopy has demonstrated the possibility of measuring extremely small wavelength shifts in noble metal nanoparticle extinction spectra.1,2 The wavelength shift (Δλmax) can be approximated as:

| (1) |

where m is the refractive index (RI) sensitivity, n2 and n1 are the RI of different surrounding media, d is the effective thickness (in nm) of medium 2 (n2), and ld is the electromagnetic field decay length (in nm).3 The demonstrated ability to measure wavelength shifts on the order of 10−3 led us to ask - what is the smallest change in RI that can be measured by HR-LSPR? The use of inert gases has proven to be an excellent approach to answer this question. Sensitive and selective detection of gas phase analytes is a significant challenge across many disciplines, from chemical warfare agents4,5 to biomarker6 detection. Therefore, it is advantageous to expand traditional solution phase detection schemes to gaseous media. Plasmonic sensors have begun to expand into gas phase applications due to their high sensitivity to the surrounding environment. In order for plasmonic gas sensors to be functional for any applications mentioned above, the sensitivity of the sensor must be carefully characterized. Herein, the high sensitivity of a plasmonic sensor is demonstrated by detecting inert gases solely using changes in bulk RI.

The field of plasmonics is based on the LSPR spectroscopy of noble metal nanoparticles. A significant consequence of the LSPR is the wavelength-dependent extinction (absorption and scattering) that depends on the nanoparticle size, shape, and surrounding RI.7 LSPR nanosensors utilize changes in the local nanoparticle environment which are manifested as a red-shift in the extinction spectrum.

Propagating SPR spectroscopy has also been used for gas sensing due to its high sensitivity to bulk RI changes8,9 and has demonstrated imaging capabilities to distinguish He from Ar in a N2 atmosphere.10 Other RI-based detection methods include photonic microring resonators11 and optical microcavities.12 Luchansky et al. reported a refractive index sensitivity of ~2 × 10−6 RIU with a sensing decay length of 63 nm for a silicon photonic microring resonator.11 LSPR sensors have a smaller sensing volume than propagating SPR sensors13 and photonic sensors.11,12 Typically, this results in higher sensitivity per unit volume for the local environment, but lower sensitivity to bulk RI changes. Therefore, previous studies of LSPR nanosensor response have utilized changes between two liquid environments with relatively large RI differences. LSPR gas sensing has been demonstrated based on chemical changes occurring at the nanoparticle surface, but not based on small changes of bulk RI. For example, Hu et al. demonstrated gas sensing with Ag nanoparticles by measuring the disappearance and reappearance of the LSPR when the Ag was exposed to O2 (g) and H2 (g), respectively.14 Lu and coworkers demonstrated vapor sensing by LSPR spectroscopy by detecting volatile organic compounds15,16 and showed enhanced vapor selectivity using self-assembled monolayers.15 Here, we report inert gas detection utilizing HR-LSPR spectroscopy based on bulk RI changes alone. Further, we demonstrate the vapor sensing capability of our sensor utilizing humid air and dry N2 gas.

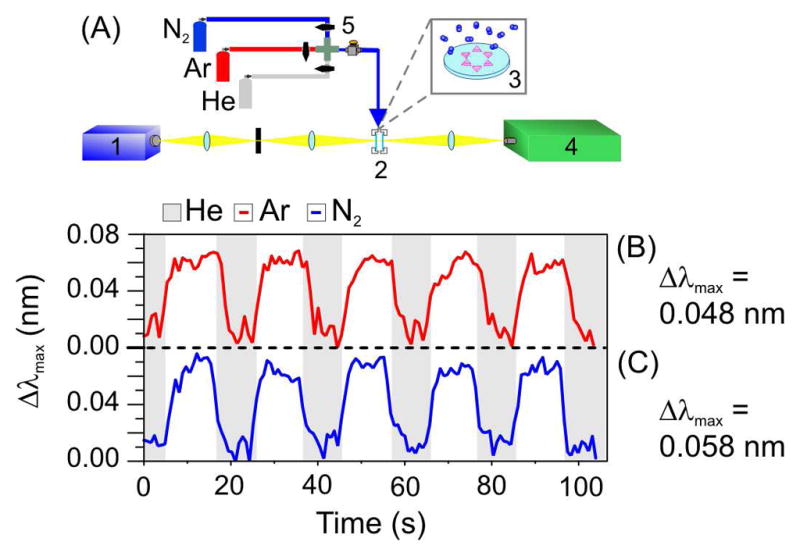

To demonstrate the gas sensing capabilities of the HR-LSPR nanosensor, the inert gases He, N2, and Ar were used to modulate the surrounding environment of Ag and Au nanoparticles fabricated by nanosphere lithography.17 The RI of He, Ar, and N2, are 1.000036, 1.000281, and 1.000298 RI units (RIU), respectively. The gas environment was switched between He and Ar, followed by He and N2 modulation every 10 s (Figure 1) and 5 s (supporting info). The HR-LSPR apparatus was interfaced with a gas dosing system to manually modulate between the three gases while measuring LSPR (Figure 1A). The gas temperature was the same as room temperature. The cylinders were held at room temperature, there was minimal adiabatic cooling at the slow flow rates employed, and there was sufficient time to equilibrate in the two stage pressure regulator and flow tube tubes. Extinction spectra were acquired every 600 ms and the λmax of each spectrum was plotted as a function of time. The plot of LSPR λmax vs. time for bare Ag nanoparticles using 10 s switching times is shown in Figure 1B (He/Ar) and 1C (He/N2), where the shaded regions represent He gas flow. The Δλmax vs. time plots exhibit mass-transport limited rise and fall times indicating the observation of bulk RI changes rather than adsorption to the nanoparticle surface. An average Δλmax of 0.048 nm and 0.058 nm for He/Ar and He/N2 switching, respectively, was observed which is consistent with predicted shifts based on eq 1 using m = 200 nm/RIU.18 Therefore, changes in the bulk environment differing in RI of only 2.45 × 10−4 and 2.62 × 10−4 RIU were observed. We expect that the signal to noise ratio can be improved by using automated mass flow controllers, lock-in detection, and improvements in lamp stability. Experiments performed using octanethiol-functionalized Ag nanoparticles (data not shown) demonstrated a RI sensitivity ~20% less than for bare nanoparticles, consistent with previous work.19 This result was expected, as the octanethiol layer occupies ~1.5 nm of the electromagnetic field decay length.20 These results confirm LSPR RI-based gas detection is possible when an adsorbate layer is present.

Figure 1.

(A) HR-LSPR gas detection apparatus. 1: lamp, 2: flow cell, 3: nanoparticle substrate, 4: HR-LSPR spectrometer, 5: gas dosing system. Plot of LSPR extinction maximum of Ag nanoparticles as a function of time as the gas is switched between (B) He (g) (shaded areas) and Ar (g) and (C) He(g) and N2(g).

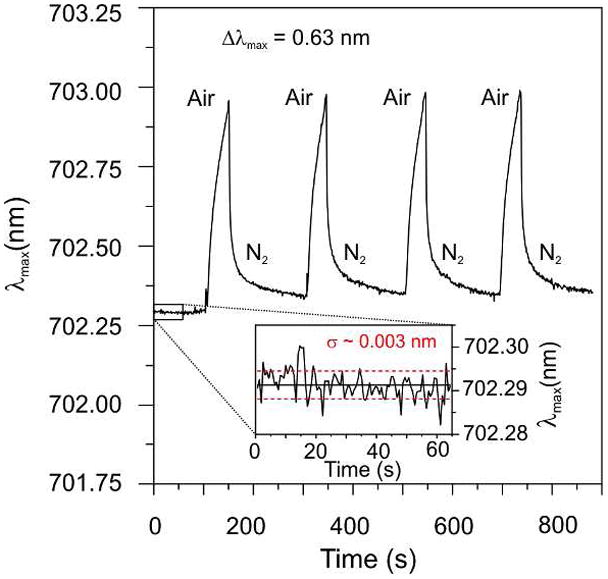

To further demonstrate the sensitivity of HR-LSPR spectroscopy, the response of Au nanoparticles to water vapor was examined. Au nanoparticles were selected instead of Ag to avoid any potential interference from silver oxidation. The bulk environment was modulated between dry N2 and 40% humid air by turning on/off the N2 gas flow. When the N2 flow was off, the N2 in the cell gradually escaped and exchanged with the ambient room air for 60 s, followed by 140 s N2 purges. The λmax response is plotted as a function of time (Figure 2). The RI of water vapor is 1.000261 RIU, slightly less than that of N2. Therefore, switching from N2 to water vapor would be expected to cause a small blue-shift if only the bulk RI change is considered. Instead, a large red shift was observed and the shape of the response indicates liquid water from the humid air adsorbs to the nanoparticle surface and then desorbs when N2 is added. The response was highly reproducible for multiple samples with an average Δλmax = 0.63 nm for the humid air exposure time (60 s). These shifts correspond to an effective adsorbate layer thickness of 0.024 nm, assuming a decay length (ld) of 5 nm. The striking conclusion drawn from this estimate is that HR-LSPR spectroscopy has sub-monolayer (~10% coverage) sensitivity to liquid water!

Figure 2.

Plot of LSPR extinction maximum as a function of time, switching between 40% humid air and dry N2 gas. A reproducible Δλmax= 0.63 nm was observed. The inset depicts the low level of noise (σ~0.003 nm) observed for the HR-LSPR experiment.

Detecting gases based on small RI changes not only demonstrates subtle bulk RI changes, but it also provides a reliable method to characterize the RI sensitivity of plasmonic materials and calibrate the plasmonic sensors using gas phase modulation. Liquids have been used for such characterization in the past, but solvent annealing, the ability to wash away weakly bound nanoparticles under strong flow, and potential interactions between the liquid and adsorbed molecules limit the applicability of liquid-based RI sensitivity characterization. Gas phase detection provides a benign characterization tool. Although the gas sensor has displayed excellent sensitivity, LSPR sensors are not inherently selective. The integration of reversible partition layers will solve this problem and is being addressed in continuing studies. In addition, volatile organic molecules which adsorb onto plasmonic surfaces can be detected and identified by using surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS).4

In conclusion, the first LSPR RI-based sensing experiment utilizing inert gases has now been demonstrated. Changes in RI as low as 2.45 × 10−4 RIU were observed reliably and reproducibly due to the low noise level in the HR-LSPR spectrometer. Additionally, the HR-LSPR gas sensor exhibited changes in the nanoparticle extinction spectrum λmax consistent with typical RI sensitivities of Ag nanoparticles. The gas sensor demonstrated rapid switching capabilities of 5 or 10 s – a significant characteristic of gas detection. We have also shown sub-monolayer sensitivity to water adsorbed on nanoparticles from exposure to 40% humid air. The HR-LSPR nanosensor has proven to be a sensitive method to detect gaseous analytes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (HDTRA 1-09-1-0007), the National Science Foundation (EEC-0647560, DMR-0520513, CHE-0911145), the National Cancer Institute (1 U54 CA119341-01), and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (5 F32 GM077020) to J.N.A.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Gas switching data using 5 s intervals. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Dahlin AB, Tegenfeldt JO, Hook F. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4416–4423. doi: 10.1021/ac0601967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall WP, Anker JN, Lin Y, Modica J, Mrksich M, Van Duyne RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5836–5837. doi: 10.1021/ja7109037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anker JN, Hall WP, Lyandres O, Shah NC, Zhao J, Van Duyne RP. Nat Mater. 2008;7:442–453. doi: 10.1038/nmat2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biggs KB, Camden JP, Anker JN, Van Duyne RP. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113:4581–4586. doi: 10.1021/jp8112649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart DA, Biggs KB, Van Duyne RP. Analyst. 2006;131:568–572. doi: 10.1039/b513326b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng C, Zhang X, Li N. J Chromatogr, B. 2004;808:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willets KA, Van Duyne RP. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2007;58:267–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liedberg B, Nylander C, Lunström I. Sens Actuators. 1983;4:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nylander C, Liedberg B, Lind T. Sens Actuators. 1982;3:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Notcovich AG, Zhuk V, Lipson SG. Appl Phys Lett. 2000;76:1665–1667. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luchansky MS, Washburn AL, Martin TA, Iqbal M, Gunn LC, Bailey RC. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.07.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vahala KJ. Nature. 2003;424:839–846. doi: 10.1038/nature01939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonzon CR, Jeoung E, Zou S, Schatz GC, Mrksich M, Van Duyne RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12669–12676. doi: 10.1021/ja047118q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J, Wang L, Cai W, Li Y, Zeng H, Zhao L, Liu P. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:19039–19045. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y-Q, Lu C-J. Sens Actuators, B. 2009;135:492–498. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng C-S, Chen Y-Q, Lu C-J. Talanta. 2007;73:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hulteen JC, Van Duyne RP. J Vac Sci Technol, A. 1995;13:1553–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen TR, Duval ML, Kelly KL, Lazarides AA, Schatz GC, Van Duyne RP. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:9846–9853. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malinsky MD, Kelly KL, Schatz GC, Van Duyne RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1471–1482. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haes AJ, Van Duyne RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10596–10604. doi: 10.1021/ja020393x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.