Abstract

Liver fibrosis is an outcome of many chronic diseases, and often results in cirrhosis, liver failure, and portal hypertension. Liver transplantation is the only treatment available for patients with advanced stage of fibrosis. Therefore, alternative methods are required to develop new strategies for anti-fibrotic therapy. Available treatments are designed to substitute for liver transplantation or bridge the patients, they include inhibitors of fibrogenic cytokines such as TGF-β1 and EGF, inhibitors of rennin angiotensin system, and blockers of TLR4 signaling. Development of liver fibrosis is orchestrated by many cell types. However, activated myofibroblasts remain the primary target for anti-fibrotic therapy. Hepatic stellate cells and portal fibroblasts are considered to play a major role in development of liver fibrosis. Here we discuss the origin of activated myofibroblasts and different aspects of their activation, differentiation and potential inactivation during regression of liver fibrosis.

Keywords: Activated myofibroblasts, Hepatic stellate cells, Portal fibroblasts, Fibrocytes, Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, Antifibrotic therapy

Introduction

Hepatic fibrosis is an outcome of many chronic liver diseases, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcoholic liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) 1. Hepatic fibrosis consists of a fibrous scar that is constituted by many extracellular matrix proteins (ECMs) including type I collagen. In all clinical and experimental liver fibrosis, myofibroblasts are the source of the ECM constituting the fibrous scar. Myofibroblasts express a-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and type I collagen and are only found in the injured, but not the normal, liver. Thus, activation and proliferation of hepatic myofibroblasts is a key mechanism in development of liver cirrhosis.

Several injury-triggered subsequent events were identified to be critical for pathogenesis of liver fibrosis and its resolution. They include: 1) immediate damage to the epithelial/endothelial barrier; 2) release of TGF-β1, the major fibrogenic cytokine; 3) increased intestinal permeability; 4) recruitment of inflammatory cells; 5) induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS); 6) activation of collagen producing cells; 7) matrix-induced activation of myofibroblasts.

Myofibroblasts are the primary target of anti-fibrotic therapy

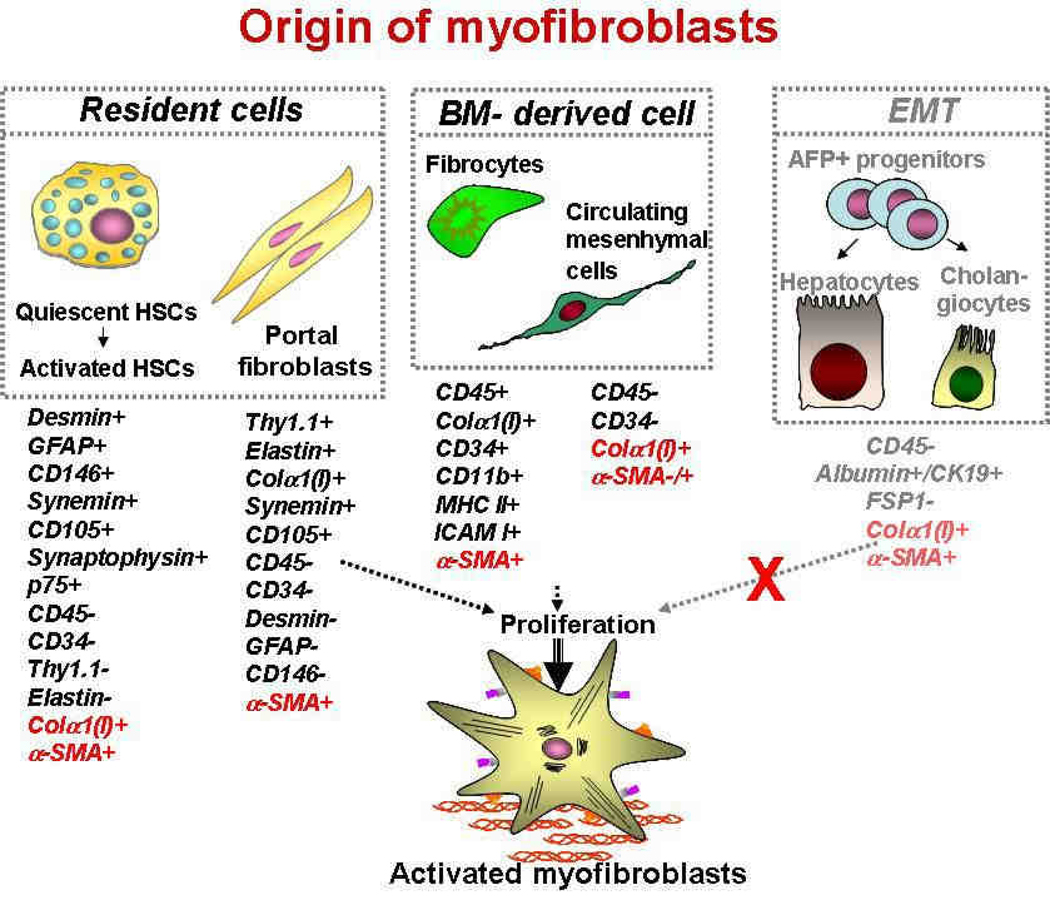

Liver myofibroblasts represent a primary target for antifibrotic therapy. The origin of fibrogenic cells (myofibroblasts) has been intensively discussed and studied, and several sources of myofibroblasts have been identified 2–5 (see Figure 1). In the fibrotic liver, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) have been reported to contribute > 80% of the collagen producing cells 1. Therefore, HSCs are currently considered to be the major, but not the only, source of myofibroblasts in the injured liver 6. Hepatic myofibroblasts may also originate from portal fibroblasts, bone marrow (BM)-derived mesenchymal cells and fibrocytes 7. Two other mechanisms were recently implicated in fibrogenesis are the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), when epithelial cells acquire features of mesenchymal cells and may give rise to fully differentiated myofibroblasts 9, 10, and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), when endothelial cells undergo a similar phenotypic change 11, 12.

Figure 1.

Three sources of myofibroblasts have been proposed in fibrotic liver: resident cells (Hepatic stellate cells and portal fibroblasts); BM-derived cells (fibrocytes and mesenchymal cells), and cells originated by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT or EndMT) and. Hence, recent studies suggested that EMT does not significantly contribute to liver fibrosis. Modified from 8.

Definition of myofibroblasts

Myofibroblasts are characterized by a stellate shape, expression of abundant pericellular matrix and fibrotic genes (α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), non-muscle myosin, fibronectin, vimentin,) 13. Ultrastructurally, myofibroblasts are defined by prominent rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER), a Golgi apparatus producing collagen, peripheral myofilaments, fibronexus (no lamina) and gap junctions 13. Myofibroblasts are implicated in wound healing and fibroproliferative disorders 14–16. Studies of fibrogenesis conducted in many organs strongly suggest that myofibroblasts are the primary source of ECM 8. In response to fibrogenic stimuli, such as TGF-β1, myofibroblasts in all tissues express α-SMA, secrete ECM (fibronectin, collagen type I and III), obtain high contractility and change phenotype (production of the stress fibers) 6. Classical myofibroblasts differentiate from a mesenchymal lineage and, therefore, lack expression of lymphoid markers such as CD45 or CD34. Sustained injury may trigger differentiation of myofibroblasts from several cellular sources, including HSCs 1.

Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSCs)

HSCs are perisinusoidal cells that normally reside in the space of Disse and contain numerous retinoid and lipid droplets 17, 18. Under physiological conditions, HSCs reside in the space of Disse and exhibit a quiescent phenotype. HSCs express neural markers, such as GFAP, synemin, synaptophysin 1, and nerve growth factor receptor p75 19, 20, Desmin, CD146, secrete HGF, and store vitamin A 21. HSCs are also implicated in phagocytosis and antigen presentation 22, 23. In response to injury, quiescent HSCs down-regulate vitamin A expression, acquire contractility and activate into collagen type I+ α-SMA+ myofibroblasts. During development HSCs are derived from the translocation of submesothelial mesenchymal cells from the liver capsule 24.

If HSCs are the primary source of myofibroblasts in certain fibrotic liver diseases, then drugs can be targeted specifically to HSCs at higher doses to avoid toxicity to other cells. Vitamin A-coupled liposomes have been used to carry an anti-fibrosis drug in experimental models of liver fibrosis 25. The concept is that HSCs will take up the vitamin A liposome containing the drug by receptor-mediated uptake bound to retinol binding protein. Other strategies have used synthetic peptide ligands targeted the PDGF receptor, which is unique to HSCs in the liver. Most recently, mannose 6-phosphate modified human serum albumin (M6PHSA) which binds to the mannose-6-phosphate/insulin growth factor type II receptor (M6P/IGII-R), has been used to target activated HSCs during experimental liver fibrogenesis 26.

Portal fibroblasts

Portal fibroblasts are spindle shaped cells of mesenchymal origin that are present in the portal tracts. Under normal conditions, they participate in physiological ECM turnover 6, 27–29 and lack expression of α-SMA. Induced mostly by cholestatic liver injury, portal fibroblasts proliferate (though much slower than HSCs 30) and deposit collagen (e.g. type I) around portal tracts 31. Portal fibroblasts are distinct from HSCs in that they express elastin and Thy-1.1 (a glycophosphatidylinositol-linked glycoprotein of the outer membrane leaflet described in fibroblasts of several organs) 32, 33, do not store retinoids, and do not express desmin or neural markers. Portal fibroblasts lack expression of Desmin, GFAP, CD146 or Vitamin A droplets. Their exact contribution to cholestatic liver injury or hepatic fibrosis of different etiologies is not well understood.

Fibrocytes

Fibrocytes originate from hematopoietic stem cells, and are defined as spindle shaped “CD45 and collagen type I (Col+) expressing leukocytes that mediate tissue repair and are capable of antigen presentation to naive T cells” 34. Due to their ability to differentiate into myofibroblasts, fibrocytes are implicated in the fibrogenesis of skin, lungs, kidneys, and liver 7, 35, 36. In addition to collagen Type I, fibronectin and vimentin, fibrocytes express CD45, CD34, MHCII, CD11b, Gr-1, and secrete growth factors (TGF-β1, MCP-1) that promote deposition of ECM 37, 38. Upon injury or stress, fibrocytes proliferate and migrate to the injured organ 34, 37. The number of recruited fibrocytes varies from 25% (lung fibrosis) 7, 39 to 5% (liver fibrosis, e.g. BDL and CCl4)2 of the collagen expressing cells, suggesting that the magnitude of fibrocyte differentiation into myofibroblasts depends on the organ and the type of injury. Although low number of fibrocytes was detected in response to BDL and CCl4 models of liver injury, this may not extend to some genetic defects causing hepatic fibrosis in mice. Thus, Abcb4 deficiency in mice results in a significant flux of fibrocytes to the liver, which may contribute to the severe fibrosis in these mice 40.

Originating in the BM, fibrocytes comprise a small subset (0.1%) of mononuclear cells, which in response to injury or stress, proliferate and migrate to the injured organ from the blood stream 34, 37. Under physiological conditions fibrocytes do not egress the BM, and only egress the BM in response to injury. Interestingly, in addition to the damaged liver, both cholestatic and toxic liver injury (BDL and CCl4) triggers migration of fibrocytes to lymphoid organs (spleen, and lymphoid patches in the intestine) 41, suggesting that the function of fibrocyte-like cells may not be limited to ECM deposition.

BM mesenchymal progenitors

Myofibroblasts can also arise from BM-derived mesenchymal progenitors 42, 43, and were shown to populate fibrotic lungs 44 and liver 43, and contribute to fibrosis by differentiating into tissue myofibroblasts 8, 17, 43. By fractionating the BM stem cell compartment, hepatic BM-derived myofibroblast-like cells were demonstrated to originate from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) 43, 45. MSCs are defined as self-renewable, multipotent progenitor cells with the capacity to differentiate into lineage specific cells that form bone, cartilage, fat, tendon and muscle 45, 46. Unlike hematopoietic stem cells, MSCs are more radioresistant 47, reside mostly in BM stroma, do not express hematopoietic markers and can be isolated as Lin−CD45−CD31−CD34−133−Sca-1+Vitamin A−CD146+ cells45, 48, 49. Whether circulating mesenchymal progenitors significantly contribute to ECM deposition in the course of liver fibrosis is unknown, but they most likely represent a population, distinct from hematopoietic-derived fibrocytes41.

Contribution of EMT and EndMT to hepatic fibrosis

Another mechanism implicated in fibrogenesis is EMT 9, 10, a process in which fully differentiated epithelial cells undergo phenotypic transition to fully differentiated mesenchymal cells (fibroblasts or myofibroblasts) 50. During EMT, epithelial cells detach from the epithelial layer, lose their polarity, down-regulate epithelial markers (e.g., cytokeratin-19 (K19), CK-7, E-cadherin) and tight junction proteins (zonula occludens-1, ZO-1), increase their motility, and obtain a (myo)fibroblast phenotype 51. Epithelial cells transitioning into (myo)fibroblasts are reported to express fibroblast specific protein-1 (FSP1), which is used as a universal marker of EMT in fibrogenesis and cancer 51, 52. However, an activated monocytic cell population expresses FSP1 in the injured liver, so FSP1 is not a valid marker of EMT in liver fibrosis. EMT of hepatocytes and cholangiocytes has been reported in patients and in mice with liver fibrosis 53–56. However, only minimal or no contribution of hepatocytes or cholangiocytes to myofibroblasts was detected in vivo 11, 57 using BDL or CCl4 models of liver fibrosis in mice. Moreover, genetic labeling of hepatocytes, cholangiocytes and their progenitors (Oval cells) has been recently tested using alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)-Cre mice in response to multiple liver injuries (Dr. R.G. Wells, in press). In concordance with previous studies, no EMT-derived myofibroblasts were detected in these mice.

Endothelial cells may also transition to mesenchymal cells (EndMT), giving rise to (myo)fibroblasts in response to fibrogenic injury. EndMT has been reported to contribute to cardiac 11 and renal 12 fibrosis. EndMT is identified by expression of myofibroblast genes 51 in endothelial cells that are expressing or have a “history” of expressing PECAM-1/CD31, Tie-1 11, Tie-2 and CD34 2, 12. A difficulty in interpreting these studies is that it is now recognized that Tie-2 is not a specific marker for endothelial cells in that it is also expressed in BM derived hematopoietic cells.

Thus, many studies have demonstrated a lack of EMT in the liver and other organs in experimental murine models using genetic fate mapping. However, due to differences in etiology and duration between liver fibrosis in patients and experimental models in mice, EMT of hepatocytes, cholangiocytes and their progenitors (Oval cells) has not been fully addressed in patients.

Progress in developing therapies for liver fibrosis

Several molecules have been successfully identified as targets for anti-fibrotic therapy. TGF-β1 plays a critical role in activation of myofibroblasts. Although inhibitors of TGF-β1 are effective in short-term animal models 58–62, they are not suitable for long term therapy because of the significant role of TGF-β1 in homeostasis and repair. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is a pleiotropic cytokine produced by hepatic stellate cells and implicated in liver regeneration and fibrosis. Similarly, treatment with inhibitors of HGF produces anti-fibrogenic effects, but also increases the risk of tumorigenesis in mice 63–65.

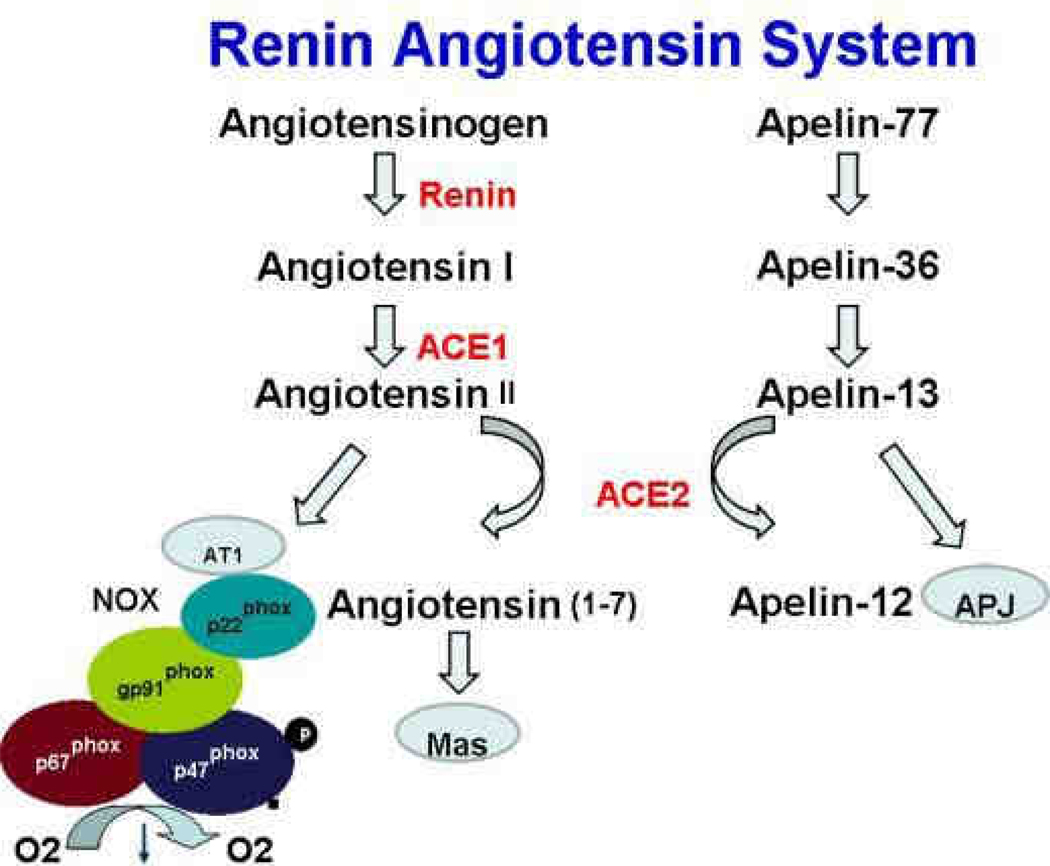

Inhibition of renin angiotensin system

The renin angiotensin pathway in hepatic stellate cells induces reactive oxygen species and accelerates hepatic fibrosis. The renin angiotensin system (RAS) regulates the systemic arterial blood pressure, but, in response to sustained liver injury, locally accelerates inflammation, tissue repair and fibrogenesis by production of angiotensin II (Ang II), a vasoconstricting agonist implicated in pathogenesis of liver fibrosis (see Figure 2). RAS is regulated by a series of subsequent enzymatic reactions: angiotensinogen (AGT) from the liver is proteolitically cleaved by rennin to form angiotensin I (Ang I), which, in turn, is processed into angiotensisn II (Ang II) by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE). Ang II binds either to AT1 or AT2 plasma membrane receptor to mediate its biological activity.

Figure 2.

The Renin Angiotensin pathway. The entire pathway is expressed in the fibrotic liver. ACE1 generates the fibrogenic Angiotensin II, which in turn binds to its receptor AT1 to activate NADPH oxidase (NOX). ACE2 has anti-fibrotic effects and degrades angiotensin II and apelin-12.

Fibrogenic actions of Ang II are mostly mediated by angiotensin receptor AT1. Stimulation of AT1 receptor by angiotensin II results in proliferation of HSCs and extracellular matrix deposition. Angiotensin II also plays an important role in ROS formation by activating NADPH oxidase in HSCs 66. In concordance, several experimental models of liver fibrosis in rodents have demonstrated that prolonged administration of angiotensin II directly causes HSC activation 67. Mice lacking AT1a receptors are protected from liver fibrosis.

This makes RAS an attractive target for antifibrotic therapy. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE1) and angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptors are upregulated in fibrotic livers, and can be successfully blocked by already widely used ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor antagonists. ACE inhibitors block angiotensin II production, while AT1 receptor antagonists prevent Ang II binding to AT1 receptors. Disruption of RAS pathway by RAS inhibitors have been shown to be effective to attenuate liver fibrosis 68 and are suitable for the long term treatment. On the other hand, ACE2 degrades the active angiotensin II to block fibrogenesis. Mice lacking ACE2 have increased liver fibrosis, and recombinant ACE2 inhibits murine models of liver fibrosis 69, 70.

Inhibition of TLR4 signalling and increased intestinal permeability

Development of liver fibrosis is associated with elevated levels of TGF-β1 and increased intestinal permeability. Gut sterilization with antibiotics attenuates liver fibrosis, whereas pathogen free animals are resistant to liver fibrosis 71. Bacteria and LPS signal via Toll-like receptor pathway. Consistently, mice with deficiencies in CD14, LPS binding protein (LBP), or TLR4 have impaired TLR signaling and are not susceptible to liver fibrosis 72. Emerging observations indicating that the TLR4 signaling pathway plays an important role in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Therefore, administration of TLR4 antagonists, LPS neutralizing agents or prolonged antibiotic intake are of major consideration for clinical trials of patients with liver fibrosis.

Inhibition of angiogenesis

Development of liver fibrosis is closely associated with angiogenesis and neovascularization. Extensive neovascularization is usually observed around dense scar tissue in cirrhotic liver, and is proposed to be mediated by elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiopoeitin 1 and 2 in the course of hepatic fibrosis. The mechanism of how angiogenesis promotes liver fibrosis remains unknown. However, administration of VEGF-receptor 1 and 2 neutralizing antibodies results in significant inhibition of liver fibrosis in mice 73. Inhibition of angiogenesis by several drugs has been also shown to be effective in suppression of liver fibrosis. Thus, semisynthetic analogue of fumagillin (TNP-470)74, exhibit anti-angiogenic properties and is currently used in clinical trials to prevent the progression of hepatic. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor Sunitinib (SU11248) also attenuates experimental models of liver fibrosis in rats. 74. In addition to other effects, inhibition of angiogenesis may also prevent progression of liver fibrosis into hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cellular therapy for cirrhosis

Therapies with the potential to substitute for liver transplantation or bridge the patient awaiting transplantation are required. Liver cell transplantation (LCT), an experimental procedure designed to reconstitute the liver mass with functional hepatocytes, is based on transplantation of isolated hepatocytes from a cadaver or from a liver portion from a living donor 75. This experimental procedure has been successfully used in patients to correct certain metabolic disorders 75. Another experimental procedure involves transplantation of hematopoietic bone marrow (BM) progenitor cells or adipose-tissue derived mesenchymal cells 76. Transplantation of fetal hepatocytes has also been considered as an alternative treatment 77.

Liver cell transplantation (LCT) has been attempted in patients with acute liver failure, chronic liver disease with end-stage cirrhosis, and children with metabolic disease 75. To date, the best outcome of allogenic hepatocyte transplantation was reported for treatment of acute liver failure. In this case, allogenic infusion of hepatocytes is aimed to provide rapid metabolism of liver toxins and stabilization of hemodynamic parameters. Thus, in 20% of patients LCT of hepatocytes from cadaver livers resulted in recovery without solid organ transplant, and in 30% bridged patients to liver transplantation 78–80. Some progress has been made in correction of metabolic diseases. According to their etiology, metabolic disorders could be divided in two groups, inherited clotting factor deficiencies and metabolic deficiencies 75. Since metabolic deficiencies are often associated with the severe damage to hepatocytes, transplanted hepatocytes have a growth advantage over recipient hepatocytes. Under these conditions, donor hepatocytes have a selective pressure and LCT has been reported in patients to correct ornithine trans-carbamylase (OTC) deficiency, α-1-anti-trypsin deficiency, glycogen storage disease type Ia, infantile Refsum’s desease, factor VII deficiency, bile salt export protein deficiency, and Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 75, 81, 82.

Purified hepatocytes are infused in patients via the portal vein or are injected into the spleen 83. On average, only 30% of hepatocytes survive transplantation. Therefore, successful engraftment often depends on the number of infused hepatocytes 83. Infusion of hepatocytes into the portal vein causes transient portal hypertension, and must be combined with pharmacological disruption of endothelial integrity required for hepatocyte extravazation 84. Hepatocytes do not tolerate cryopreservation well and lose expression of adhesion molecules, which play an important role in hepatocyte extravasation and engraftment between the host hepatocytes 84. In addition, cryopreservation further decreases the viability of hepatocytes by 30% 85, 86. Immunological rejection of hepatocytes requires prolonged immunosuppressive therapy in patients suitable for LCT 87. Identification and characterization of hepatocyte progenitor/stem cells and their differentiation into functionally mature liver cells is an evolving goal for the stem cell therapy.

The improvement of liver function following the transplantation of hematopoietic progenitors in mice and rats provided the basis for clinical trials. To date, 11 clinical trials with BM-derived cells have been conducted 77. Clinical studies with transplantation of autologous CD133+ BM cells in patients have been reported to stimulate liver regeneration, as demonstrated by a reduction of bilirubin, increased albumin, and improved coagulopathy 88. Similar to that, autologous infusion of CD34+ blood cells, or even concentrated monocytes, improved biochemical parameters and stimulated liver regeneration 89. While transplantation of hematopoietic progenitors appeared beneficial in patients, the mechanism of their action remains controversial and may not reflect the generation of BM-derived hepatocytes. Such improvement may result from release of cytokines and growth factors by transplanted hematopoietic cells, or occur due to infusion of scar-resorbing monocytes. In concordance with this observation, treatment with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was used to mobilize the BM cells and demonstrated a positive effect in patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis 90.

Mesenchymal stem cells serve as another attractive target for the liver stem cell therapy. Although infusion of MSCs often results in attenuation or improvement of liver disease, current studies have not provided definitive evidence that MSCs have a capability to differentiate into functional hepatocytes in vivo 91–95. In turn, these improvements could be attributed to the secretion of soluble factors by MSCs, rather then transdifferentiation into hepatocytes. In concordance with this notion, injection of MSC-derived conditioning media into a liver-assist device can prevent hepatocyte apoptosis and increase their proliferation 96, 97. Moreover, recent studies have raised a safety question of MSCs transplantation, demonstrating that MSCs can give rise to fibrogenic myofibroblasts in mice in response to liver injury. BM-derived MSCs contributed to the development of liver fibrosis in chimeric mice that received bone marrow transplantation with the enriched BM mesenchymal fraction, and subjected to the CCl4-liver injury 43. Taken together, both hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells demonstrated a limited contribution to hepatocyte replenishment, but may stimulate liver function by providing soluble growth factors or cytokines 41, 98, 99

A few clinical trials have been performed in patients with the cirrhosis caused by hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcohol, or cryptogenic. These patients were transplanted with autologous MSCs harvested from the iliac crest. The tested parameters (albumin, creatinine) demonstrated a modest but significant improvement without severe adverse effects, suggesting that MSCs injection might be useful for the treatment of end-stage liver disease with satisfactory tolerability 100. In a different clinical trial, MSCs were used in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. All patients showed good tolerance and decreased Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores, and improvement in albumin production and liver function after six month of follow up 100.

Reversal of liver fibrosis

Mechanism of regression of liver fibrosis

Until recently, it was believed that hepatic fibrosis was irreversible 101. However, sequential liver biopsies have documented that removing the underlying etiological agent may reverse hepatic fibrosis in patients with secondary biliary fibrosis 102, Hepatitis C 103, Hepatitis B 104, NASH 105, and autoimmune hepatitis 106. Furthermore, in experimental models of CCl4 107, 108 and BDL 109 induced liver fibrosis, removal of the etiological agent results in reversal of fibrosis 1. Withdrawal of the etiological source of the chronic injury (e.g. HBV, HCV) 1 results in decrease of pro-inflammatory and fibrogenic (TGFβ1) cytokines, decreased ECM production, increased collagenase activity 1, 2, and the disappearance of activated myofibroblasts. The currently accepted mechanism for the elimination of activated myofibroblasts is that these cells rapidly decline due to apoptosis of activated HSCs 110. Several mechanisms are implicated in the apoptosis of activated HSCs: 1). Activation of death receptor-mediated pathways (Fas or TNFR-1 receptors) and caspases 8 and 3; 2) up-regulation of pro-apoptotic proteins (e.g. p53, Bax, caspase 9); and 3) decrease of pro-survival genes (e.g. Bcl-2) 111. A population of liver associated natural killer (NK) cells and γδ T (NKT) cells stimulate apoptosis of activated HSCs. Drugs that induce apoptosis in activated HSCs (glyotoxin, sulfasalazine, IKK inhibitors, and anti-TIMP antibodies) cause liver fibrosis to regress 1, 2. Increased collagenase activity is a primary pathway of fibrosis resolution. At this stage, activated macrophages/Kupffer cells secrete matrix metalloproteinases, e.g. MMP-13 interstitial collagenase, responsible for matrix degradation 5, 112. Moreover, increased activity of collagen degrading enzymes correlates with decreased TIMPs, tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinasesis 111. Whether end-stage cirrhosis can reverse to a normal liver architecture remains controversial17, 113. However, significant improvement in hepatic structure and function provide evidence of regression of liver fibrosis114. Perhaps ECM remodeling is limited in cirrhosis by formation of non-reducible cross-linked collagen and an ECM rich with elastin fibers preventing its degradation. This pathophysiological state may lead to a “point of no return” for liver fibrosis17, 114.

The role of myofibroblasts in reversal of liver fibrosis

HSCs are a major source of collagen producing cells in fibrotic liver. Although HSC death by apoptosis 107 and senescence 115 during the regression of liver fibrosis is well documented, its quantitative contribution is unknown 114. Theoretically, activated HSCs/myofibroblasts may transdifferentiate into another phenotype or revert to quiescent HSCs. Although the cellular population of quiescent HSCs are restored in mice recovering from fibrosis, the source of these quiescent HSCs is unknown. In concordance, studies in culture suggest that HSCs, at least in part, can reverse to a quiescent phenotype. Therefore, the disappearance of activated α-SMA+ Col+ activated HSCs/myofibroblasts in the course of fibrosis reversal may indicate that activated HSCs return to a quiescent state.

The quiescent phenotype of HSCs is associated with expression of lipogenic genes and storage of vitamin A in lipid droplets. Depletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) constitutes a key molecular events for HSC activation, and ectopic expression of this nuclear receptor results in the phenotypic reversal of activated HSC to quiescent cells in culture 116. The treatment of activated HSC with an adipocyte differentiation cocktail or over-expression of SREBP-1c results in up-regulation of adipogenic transcription factors and causes morphologic and biochemical reversal of activated HSC to quiescent cells 117, 118. In addition, quiescence of HSCs largely depends of the ECM environment, and matrix composition is important to maintain the quiescent phenotype of HSCs. Thus, spontaneous activation of quiescent HSCs is attenuated when cultured on basement membrane-like ECM 119, and plastic activated HSCs reverse their phenotype and down-regulate fibroblast markers if transferred to basement membrane-like ECM 119. Although this data suggests that activated HSCs can reverse to quiescent state, these findings have only been documented in cultured cells.

Inactivation of myofibroblasts during reversal of fibrosis opens new prospectives for therapy

Hepatic fibrosis is reversible in patients and in experimental models with decreased fibrous scar and disappearance of the myofibroblast population. However, the fate of the myofibroblasts is unknown. Although some myofibroblasts undergo cell death 107, an alternative untested hypothesis is that the myofibroblasts revert to their original quiescent phenotype or obtain a new phenotype. Understanding of the origin and biology of fibrogenic myofibroblasts will provide a new target for anti-fibrotic therapy.

Summary

Inactivation of myofibroblasts during reversal of fibrosis opens new prospects for therapy. Hepatic fibrosis is reversible in patients and in experimental models with decreased fibrous scar and disappearance of the myofibroblast population. However, the fate of the myofibroblasts is unknown. Although some myofibroblasts undergo cell death 79, an alternative untested hypothesis is that the myofibroblasts revert to their original quiescent phenotype or obtain a new phenotype. Understanding of the origin and biology of fibrogenic myofibroblasts will provide a new target for anti-fibrotic therapy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest:

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Hepatic stellate cells and the reversal of fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21 Suppl 3:S84–S87. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1776–1784. doi: 10.1172/JCI20530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomperts BN, Strieter RM. Fibrocytes in lung disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:449–456. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0906587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallowfield JA, Mizuno M, Kendall TJ, et al. Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. J Immunol. 2007;178:5288–5295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parola M, Marra F, Pinzani M. Myofibroblast - like cells and liver fibrogenesis: Emerging concepts in a rapidly moving scenario. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Fibrogenesis of parenchymal organs. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:338–342. doi: 10.1513/pats.200711-168DR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Mechanisms of fibrogenesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:109–122. doi: 10.3181/0707-MR-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalluri R. EMT: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1417–1419. doi: 10.1172/JCI39675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi SS, Diehl AM. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions in the liver. Hepatology. 2009 doi: 10.1002/hep.23196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:952–961. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeisberg EM, Potenta SE, Sugimoto H, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2282–2287. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyden B. The myofibroblast: phenotypic characterization as a prerequisite to understanding its functions in translational medicine. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:22–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majno G, Gabbiani G, Hirschel BJ, Ryan GB, Statkov PR. Contraction of granulation tissue in vitro: similarity to smooth muscle. Science. 1971;173:548–550. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3996.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabbiani G, Ryan GB, Majne G. Presence of modified fibroblasts in granulation tissue and their possible role in wound contraction. Experientia. 1971;27:549–550. doi: 10.1007/BF02147594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schurch W, Seemayer TA, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: a quarter century after its discovery. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:141–147. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iredale JP. Models of liver fibrosis: exploring the dynamic nature of inflammation and repair in a solid organ. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:539–548. doi: 10.1172/JCI30542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geerts A. History, heterogeneity, developmental biology, and functions of quiescent hepatic stellate cells. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:311–335. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachs BD, Baillie GS, McCall JR, et al. p75 neurotrophin receptor regulates tissue fibrosis through inhibition of plasminogen activation via a PDE4/cAMP/PKA pathway. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:1119–1132. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendall TJ, Hennedige S, Aucott RL, et al. p75 Neurotrophin receptor signaling regulates hepatic myofibroblast proliferation and apoptosis in recovery from rodent liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2009;49:901–910. doi: 10.1002/hep.22701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senoo H, Kojima N, Sato M. Vitamin a-storing cells (stellate cells) Vitam Horm. 2007;75:131–159. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)75006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bataller R, Schwabe RF, Choi YH, et al. NADPH oxidase signal transduces angiotensin II in hepatic stellate cells and is critical in hepatic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1383–1394. doi: 10.1172/JCI18212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winau F, Hegasy G, Weiskirchen R, et al. Ito cells are liver-resident antigen-presenting cells for activating T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;26:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asahina K, Tsai SY, Li P, et al. Mesenchymal origin of hepatic stellate cells, submesothelial cells, and perivascular mesenchymal cells during mouse liver development. Hepatology. 2009;49:998–1011. doi: 10.1002/hep.22721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato Y, Murase K, Kato J, et al. Resolution of liver cirrhosis using vitamin A-coupled liposomes to deliver siRNA against a collagen-specific chaperone. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:431–442. doi: 10.1038/nbt1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno M, Gonzalo T, Kok RJ, et al. Reduction of advanced liver fibrosis by short-term targeted delivery of an angiotensin receptor blocker to hepatic stellate cells in rats. Hepatology. 51:942–952. doi: 10.1002/hep.23419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuchweber B, Desmouliere A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Rubbia-Brandt L, Gabbiani G. Proliferation and phenotypic modulation of portal fibroblasts in the early stages of cholestatic fibrosis in the rat. Lab Invest. 1996;74:265–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyot C, Lepreux S, Combe C, et al. Hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis: the (myo)fibroblastic cell subpopulations involved. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:135–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinnman N, Francoz C, Barbu V, et al. The myofibroblastic conversion of peribiliary fibrogenic cells distinct from hepatic stellate cells is stimulated by platelet-derived growth factor during liver fibrogenesis. Lab Invest. 2003;83:163–173. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000054178.01162.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells RG, Kruglov E, Dranoff JA. Autocrine release of TGF-beta by portal fibroblasts regulates cell growth. FEBS Lett. 2004;559:107–110. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knittel T, Kobold D, Saile B, et al. Rat liver myofibroblasts and hepatic stellate cells: different cell populations of the fibroblast lineage with fibrogenic potential. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1205–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudas J, Mansuroglu T, Batusic D, Saile B, Ramadori G. Thy-1 is an in vivo and in vitro marker of liver myofibroblasts. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;329:503–514. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0437-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yovchev MI, Zhang J, Neufeld DS, Grozdanov PN, Dabeva MD. Thymus cell antigen-1-expressing cells in the oval cell compartment. Hepatology. 2009;50:601–611. doi: 10.1002/hep.23012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med. 1994;1:71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J Immunol. 2001;166:7556–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strieter RM, Gomperts BN, Keane MP. The role of CXC chemokines in pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:549–556. doi: 10.1172/JCI30562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quan TE, Cowper S, Wu SP, Bockenstedt LK, Bucala R. Circulating fibrocytes: collagen-secreting cells of the peripheral blood. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellini A, Mattoli S. The role of the fibrocyte, a bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor, in reactive and reparative fibroses. Lab Invest. 2007;87:858–870. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strieter RM, Keeley EC, Hughes MA, Burdick MD, Mehrad B. The role of circulating mesenchymal progenitor cells (fibrocytes) in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0309132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roderfeld M, Rath T, Voswinckel R, et al. Bone marrow transplantation demonstrates medullar origin of CD34+ fibrocytes and ameliorates hepatic fibrosis in Abcb4−/− mice. Hepatology. 51:267–276. doi: 10.1002/hep.23274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kisseleva T, Uchinami H, Feirt N, et al. Bone marrow-derived fibrocytes participate in pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forbes SJ, Russo FP, Rey V, et al. A significant proportion of myofibroblasts are of bone marrow origin in human liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:955–963. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russo FP, Alison MR, Bigger BW, et al. The bone marrow functionally contributes to liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1807–1821. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hashimoto N, Jin H, Liu T, Chensue SW, Phan SH. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:243–252. doi: 10.1172/JCI18847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kallis YN, Forbes SJ. The bone marrow and liver fibrosis: friend or foe? Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1218–1221. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song L, Tuan RS. Transdifferentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow. FASEB J. 2004;18:980–982. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1100fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bartsch K, Al-Ali H, Reinhardt A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells remain host-derived independent of the source of the stem-cell graft and conditioning regimen used. Transplantation. 2009;87:217–221. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181938998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Short BJ, Brouard N, Simmons PJ. Prospective isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse compact bone. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;482:259–268. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-060-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simmons PJ, Przepiorka D, Thomas ED, Torok-Storb B. Host origin of marrow stromal cells following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Nature. 1987;328:429–432. doi: 10.1038/328429a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zavadil J, Bitzer M, Liang D, et al. Genetic programs of epithelial cell plasticity directed by transforming growth factor-beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6686–6691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111614398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1429–1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI36183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nitta T, Kim JS, Mohuczy D, Behrns KE. Murine cirrhosis induces hepatocyte epithelial mesenchymal transition and alterations in survival signaling pathways. Hepatology. 2008;48:909–919. doi: 10.1002/hep.22397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeisberg M, Yang C, Martino M, et al. Fibroblasts derive from hepatocytes in liver fibrosis via epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23337–23347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Omenetti A, Porrello A, Jung Y, et al. Hedgehog signaling regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition during biliary fibrosis in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3331–3342. doi: 10.1172/JCI35875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Syn WK, Jung Y, Omenetti A, et al. Hedgehog-Mediated Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Fibrogenic Repair in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2009 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seki E, de Minicis S, Inokuchi S, et al. CCR2 promotes hepatic fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:185–197. doi: 10.1002/hep.22952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Subeq YM, Ke CY, Lin NT, Lee CJ, Chiu YH, Hsu BG. Valsartan decreases TGF-beta1 production and protects against chlorhexidine digluconate-induced liver peritoneal fibrosis in rats. Cytokine. 53:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He H, Mennone A, Boyer JL, Cai SY. combination of retinoic acid and ursodeoxycholic acid attenuates liver injury in bile duct-ligated rats and human hepatic cells. Hepatology. doi: 10.1002/hep.24047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szuster-Ciesielska A, Plewka K, Daniluk J, Kandefer-Szerszen M. Betulin and betulinic acid attenuate ethanol-induced liver stellate cell activation by inhibiting reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytokine (TNF-alpha, TGF-beta) production and by influencing intracellular signaling. Toxicology. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu Y, Wang Z, Kwong SQ, et al. Inhibition of PDGF, TGF-beta and Abl signaling and reduction of liver fibrosis by the small molecule Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase antagonist Nilotinib. J Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giannelli G, Mazzocca A, Fransvea E, Lahn M, Antonaci S. Inhibiting TGF-beta signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baek JY, Morris SM, Campbell J, Fausto N, Yeh MM, Grady WM. TGF-beta inactivation and TGF-alpha overexpression cooperate in an in vivo mouse model to induce hepatocellular carcinoma that recapitulates molecular features of human liver cancer. Int J Cancer. 127:1060–1071. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trobridge P, Knoblaugh S, Washington MK, et al. TGF-beta receptor inactivation and mutant Kras induce intestinal neoplasms in mice via a beta-catenin-independent pathway. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1680–1688. e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arteaga CL, Dugger TC, Hurd SD. The multifunctional role of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta s on mammary epithelial cell biology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;38:49–56. doi: 10.1007/BF01803783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Minicis S, Brenner DA. NOX in liver fibrosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;462:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang L, Bataller R, Dulyx J, et al. Attenuated hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in angiotensin type 1a receptor deficient mice. J Hepatol. 2005;43:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yokohama S, Yoneda M, Haneda M, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of an angiotensin II receptor antagonist in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2004;40:1222–1225. doi: 10.1002/hep.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Molteni A, Heffelfinger S, Moulder JE, Uhal B, Castellani WJ. Potential deployment of angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitors and of angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptor blockers in cancer chemotherapy. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2006;6:451–460. doi: 10.2174/187152006778226521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schuppan D, Popov Y. Rationale and targets for antifibrotic therapies. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:949–957. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Isayama F, Hines IN, Kremer M, et al. LPS signaling enhances hepatic fibrogenesis caused by experimental cholestasis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00405.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and receptor interaction is a prerequisite for murine hepatic fibrogenesis. Gut. 2003;52:1347–1354. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tugues S, Fernandez-Varo G, Munoz-Luque J, et al. Antiangiogenic treatment with sunitinib ameliorates inflammatory infiltrate, fibrosis, and portal pressure in cirrhotic rats. Hepatology. 2007;46:1919–1926. doi: 10.1002/hep.21921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Soto-Gutierrez A, Navarro-Alvarez N, Yagi H, Yarmush ML. Stem cells for liver repopulation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14:667–673. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283328070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Forbes SJ. Stem cell therapy for chronic liver disease--choosing the right tools for the job. Gut. 2008;57:153–155. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.134247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fitzpatrick E, Mitry RR, Dhawan A. Human hepatocyte transplantation: state of the art. J Intern Med. 2009;266:339–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Strom SC, Chowdhury JR, Fox IJ. Hepatocyte transplantation for the treatment of human disease. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:39–48. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Habibullah CM, Syed IH, Qamar A, Taher-Uz Z. Human fetal hepatocyte transplantation in patients with fulminant hepatic failure. Transplantation. 1994;58:951–952. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199410270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sterling RK, Fisher RA. Liver transplantation. Living donor, hepatocyte, and xenotransplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2001;5:431–460. vii. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(05)70173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quaglia A, Lehec SC, Hughes RD, et al. Liver after hepatocyte transplantation for liver-based metabolic disorders in children. Cell Transplant. 2008;17:1403–1414. doi: 10.3727/096368908787648083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dhawan A, Mitry RR, Hughes RD. Hepatocyte transplantation for liver-based metabolic disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:431–435. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu YM, Joseph B, Berishvili E, Kumaran V, Gupta S. Hepatocyte transplantation and drug-induced perturbations in liver cell compartments. Hepatology. 2008;47:279–287. doi: 10.1002/hep.21937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kumaran V, Joseph B, Benten D, Gupta S. Integrin and extracellular matrix interactions regulate engraftment of transplanted hepatocytes in the rat liver. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1643–1653. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hughes RD, Mitry RR, Dhawan A. Hepatocyte transplantation for metabolic liver disease: UK experience. J R Soc Med. 2005;98:341–345. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.8.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Terry C, Mitry RR, Lehec SC, et al. The effects of cryopreservation on human hepatocytes obtained from different sources of liver tissue. Cell Transplant. 2005;14:585–594. doi: 10.3727/000000005783982765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bumgardner GL, Orosz CG. Unusual patterns of alloimmunity evoked by allogeneic liver parenchymal cells. Immunol Rev. 2000;174:260–279. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.am Esch JS, 2nd, Knoefel WT, Klein M, et al. Portal application of autologous CD133+ bone marrow cells to the liver: a novel concept to support hepatic regeneration. Stem Cells. 2005;23:463–470. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gordon MY, Levicar N, Pai M, et al. Characterization and clinical application of human CD34+ stem/progenitor cell populations mobilized into the blood by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1822–1830. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gaia S, Smedile A, Omede P, et al. Feasibility and safety of G-CSF administration to induce bone marrow-derived cells mobilization in patients with end stage liver disease. J Hepatol. 2006;45:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mercer AE, Regan SL, Hirst CM, et al. Functional and toxicological consequences of metabolic bioactivation of methapyrilene via thiophene S-oxidation: Induction of cell defence, apoptosis and hepatic necrosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;239:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Banas A, Teratani T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Rapid hepatic fate specification of adipose-derived stem cells and their therapeutic potential for liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:70–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kuo TK, Hung SP, Chuang CH, et al. Stem cell therapy for liver disease: parameters governing the success of using bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:2111–2121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.015. 21 e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abdel Aziz MT, Atta HM, Mahfouz S, et al. Therapeutic potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on experimental liver fibrosis. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sgodda M, Aurich H, Kleist S, et al. Hepatocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from rat peritoneal adipose tissue in vitro and in vivo. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2875–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yagi H, Parekkadan B, Suganuma K, et al. Long-term superior performance of a stem cell/hepatocyte device for the treatment of acute liver failure. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3377–3388. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van Poll D, Parekkadan B, Cho CH, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules directly modulate hepatocellular death and regeneration in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology. 2008;47:1634–1643. doi: 10.1002/hep.22236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Thorgeirsson SS, Grisham JW. Hematopoietic cells as hepatocyte stem cells: a critical review of the evidence. Hepatology. 2006;43:2–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.21015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alison MR, Islam S, Lim S. Stem cells in liver regeneration, fibrosis and cancer: the good, the bad and the ugly. J Pathol. 2009;217:282–298. doi: 10.1002/path.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kharaziha P, Hellstrom PM, Noorinayer B, et al. Improvement of liver function in liver cirrhosis patients after autologous mesenchymal stem cell injection: a phase I–II clinical trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1199–1205. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832a1f6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ramachandran P, Iredale JP. Reversibility of liver fibrosis. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hammel P, Couvelard A, O'Toole D, et al. Regression of liver fibrosis after biliary drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stenosis of the common bile duct. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:418–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arthur MJ. Reversibility of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis following treatment for hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1525–1528. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kweon YO, Goodman ZD, Dienstag JL, et al. Decreasing fibrogenesis: an immunohistochemical study of paired liver biopsies following lamivudine therapy for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2001;35:749–755. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dixon JB, Bhathal PS, Hughes NR, O'Brien PE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Improvement in liver histological analysis with weight loss. Hepatology. 2004;39:1647–1654. doi: 10.1002/hep.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Decreased fibrosis during corticosteroid therapy of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2004;40:646–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Iredale JP, Benyon RC, Pickering J, et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution of rat liver fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and reduced hepatic expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:538–549. doi: 10.1172/JCI1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Issa R, Zhou X, Constandinou CM, et al. Spontaneous recovery from micronodular cirrhosis: evidence for incomplete resolution associated with matrix cross-linking. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1795–1808. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Issa R, Williams E, Trim N, et al. Apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells: involvement in resolution of biliary fibrosis and regulation by soluble growth factors. Gut. 2001;48:548–557. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Phan SH. The myofibroblast in pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2002;122:286S–289S. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.286s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Iredale JP. Hepatic stellate cell behavior during resolution of liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:427–436. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Uchinami H, Seki E, Brenner DA, D'Armiento J. Loss of MMP 13 attenuates murine hepatic injury and fibrosis during cholestasis. Hepatology. 2006;44:420–429. doi: 10.1002/hep.21268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Friedman SL, Bansal MB. Reversal of hepatic fibrosis -- fact or fantasy? Hepatology. 2006;43:S82–S88. doi: 10.1002/hep.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Varga J, Brenner D, Phan SE. Fibrosis Research. Methods and Protocols. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell. 2008;134:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.She H, Xiong S, Hazra S, Tsukamoto H. Adipogenic transcriptional regulation of hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4959–4967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tsukamoto H. Fat paradox in liver disease. Keio J Med. 2005;54:190–192. doi: 10.2302/kjm.54.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tsukamoto H. Adipogenic phenotype of hepatic stellate cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:132S–133S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000189279.92602.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gaca MD, Zhou X, Issa R, Kiriella K, Iredale JP, Benyon RC. Basement membrane-like matrix inhibits proliferation and collagen synthesis by activated rat hepatic stellate cells: evidence for matrix-dependent deactivation of stellate cells. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:229–239. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]