Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) containing α6β2 subunits expressed by dopamine neurons regulate nicotine-evoked dopamine release. Previous results show that the α6β2* nAChR antagonist, N,N′-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-picolinium dibromide (bPiDDB) inhibits nicotine-evoked dopamine release from dorsal striatum and decreases nicotine self-administration in rats. However, overt toxicity emerged with repeated bPiDDB treatment. The current study evaluated the preclinical pharmacology of a bPiDDB analogue.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

The C10 analogue of bPiDDB, N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI), was evaluated preclinically for nAChR antagonist activity.

KEY RESULTS

bPiDI inhibits nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow (IC50 = 150 nM, Imax = 58%) from rat striatal slices. Schild analysis revealed a rightward shift in the nicotine concentration–response curve and surmountability with increasing nicotine concentration; however, the Schild regression slope differed significantly from 1.0, indicating surmountable allosteric inhibition. Co-exposure of maximally inhibitory concentrations of bPiDI (1 µM) and the α6β2* nAChR antagonist α-conotoxin MII (1 nM) produced inhibition not different from either antagonist alone, indicating that bPiDI acts at α6β2* nAChRs. Nicotine treatment (0.4 mg·kg−1·day−1, 10 days) increased more than 100-fold the potency of bPiDI (IC50 = 1.45 nM) to inhibit nicotine-evoked dopamine release. Acute treatment with bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) specifically reduced nicotine self-administration relative to responding for food. Across seven daily treatments, bPiDI decreased nicotine self-administration; however, tolerance developed to the acute decrease in food-maintained responding. No observable body weight loss or lethargy was observed with repeated bPiDI.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that α6β2* nAChR antagonists have potential for development as pharmacotherapies for tobacco smoking cessation.

Keywords: α6β2, nicotinic receptor antagonist, dopamine, nicotine, self-administration, tobacco smoking, rat

Introduction

Drugs of abuse activate the dopaminergic reward circuitry, leading to dopamine release in nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and striatum, which is associated with primary reward and habit formation respectively (Di Chiara et al., 2004; Koob and Volkow, 2010). The transition from reward seeking to compulsive behaviour associated with drug abuse appears to result from a shift from NAcc to striatal control (Koob and Volkow, 2010). Nicotine activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs; receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2009) that modulate dopamine release. Identifying nAChRs regulating dopamine release is important because dopamine plays a critical role in nicotine primary reward as revealed using self-administration models (Corrigall et al., 1992). Nicotine self-administration activates dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), and microinjection of nicotine into VTA maintains self-administration (Ikemoto et al., 2006; Cailléet al., 2009). Conversely, intra-VTA infusion of dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE; β2 nAChR antagonist) or NAcc infusion of 6-hydroxydopamine (Corrigall et al., 1992, 1994) reduces nicotine self-administration. Because nicotine fails to promote dopamine release, elicit hyperactivity or maintain self-administration in α4 or β2 subunit knockout mice (Picciotto et al., 1998; Marubio et al., 2003; King et al., 2004; Pons et al., 2008), it appears that nAChRs containing the α4 and β2 subunit contribute to the regulation of the abuse-related effects of nicotine.

Recent evidence suggests that nAChRs incorporating the α6 subunit also regulate nicotine reward. Expression of α6 is restricted primarily to dopaminergic neurons, on both presynaptic terminals and cell bodies (Champtiaux et al., 2002; Visanji et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2009). Evidence for this comes from a recent study demonstrating that 6-hydroxydopamine, which selectively attacks dopaminergic neurons, produces a >90% decrease in α6 subunit mRNA expression in the nigrostriatal tract (Visanji et al., 2006). Nicotine self-administration is absent in α6 (–/–) mice (Pons et al., 2008), whereas mice with gain-of-function α6 nAChRs are hypersensitive to nicotine (Drenan et al., 2008). Chronic nicotine administration decreases α6 expression in rats, mice and non-human primates (Mugnaini et al., 2006; Perry et al., 2007; Perez et al., 2009; but also see, Parker et al., 2004). The neuropeptide α-conotoxin MII (α-CtxMII), a selective α6β2* nAChR antagonist (* indicates possible presence of other nAChR subunits; Champtiaux et al., 2002), potently (Ki < 3 nM) inhibits a portion of [3H]epibatidine binding to mouse brain membranes (Whiteaker et al., 2000) and attenuates nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release from mouse striatal synaptosomes (Kulak et al., 1997; Salminen et al., 2004). The incomplete inhibition (Imax = 30%) in striatum produced by α-CtxMII is due to the lack of inhibition of α4β2* nAChRs (Perez et al., 2008). In contrast, α-CtxMII completely inhibits nicotine-evoked dopamine release from rat NAcc slices (Exley et al., 2008), perhaps indicating a greater functional role of α6β2* nAChRs in this brain region. Also, α-CtxMII reduces nicotine self-administration under a progressive-ratio schedule of reinforcement (Brunzell et al., 2009), indicating that α-CtxMII-sensitive, NAcc α6β2* nAChRs have a critical role in nicotine reinforcement. Unfortunately, the lack of small molecules acting as α6β2* nAChR antagonists has limited the evaluation of α6β2* nAChRs as a pharmacological target for the development of smoking cessation agents.

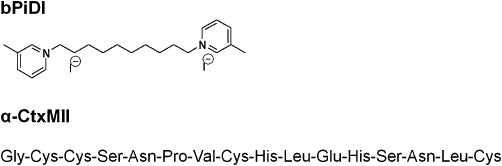

N,N′-Alkane-diyl-bis-3-picolinium analogues with C6-12 methylene linkers are inhibitors of α6β2* nAChRs (Dwoskin et al., 2008). The C12 analogue, N,N′-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-picolinium dibromide (bPiDDB), inhibits ∼60% of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release from rat striatal slices, and no additivity is observed with maximally inhibitory concentrations of bPiDDB (10 nM) and α-CtxMII (1 nM), indicating that bPiDDB acts at α6β2* nAChRs. Also, bPiDDB completely inhibits nicotine-evoked dopamine release from rat NAcc demonstrated using in vivo microdialysis (Rahman et al., 2007), and following peripheral administration of bPiDDB, specifically reduces nicotine self-administration (Neugebauer et al., 2006). However, toxicity emerged with repeated bPiDDB administration (lethality after 5.6 mg·kg−1·day−1s.c.; unpublished observations). The C10 analogue, N,N′-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI; Figure 1), attenuates nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release from striatal slices and hyperactivity in nicotine-sensitized rats, similarly to bPiDDB (Dwoskin et al., 2008). In order to more fully characterize the neuropharmacology of bPiDI, the current series of experiments was designed to assess the pharmacological mechanism of action for bPiDI, bPiDI inhibitory activity in drug naïve compared with nicotine-sensitized rats, as well as effects of bPiDI on nicotine self-administration following both acute and repeated administration. Our results show that bPiDI inhibits α-CtxMII-sensitive α6β2* nAChRs via a surmountable allosteric mechanism, and that inhibitory potency was increased 100-fold in nicotine-sensitized rats. Also, bPiDI decreased nicotine self-administration, and tolerance did not develop to this effect following repeated administration. Importantly, toxicity was not evident at behaviourally relevant doses following repeated administration.

Figure 1.

The structure of N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI).

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental protocols were in accordance with the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences National Research Council (1996), and approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan Industries, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled colony with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle. Experiments were conducted during the light phase. Unless stated otherwise, rats had ad libitum access to food and water in the home cage.

[3H]dopamine release

Nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow was determined using superfused rat striatal slices preloaded with [3H]dopamine (Grinevich et al., 2003). Coronal slices of dorsal striatum (not including nucleus accumbens core or shell; 500 µm, ∼5 mg) were incubated for 30 min in Krebs' buffer with 0.1 µM [3H]dopamine (final concentration) for 30 min. Slices were transferred to a 2500 Suprafusion system (Brandel, Inc.; Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and superfused (0.6 mL·min−1) for 60 min with Krebs' buffer. During the entire superfusion period, Krebs buffer contained nomifensine (10 µM) and pargyline (10 µM) at 34°C to assure that the [3H] collected primarily represents [3H]dopamine released into superfusate rather than [3H]metabolites (Zumstein et al., 1981). Evaluation of the inhibitory effect of bPiDI (20 µM) and mecamylamine (30 µM; reference compound) on nicotine (30 µM)-evoked endogenous dopamine concentrations and dihydroxyphenylacetic acid concentrations in superfusate were also conducted (drug concentrations based on results from radiolabeled-experiments; supplemental data). Following 60 min, two samples (2.4 mL·sample−1) were collected at 4-min intervals to determine basal [3H]dopamine outflow. Then, each slice from an individual rat was superfused for 36 min in either the absence or presence of one of five bPiDI concentrations (1 nM–10 µM) to determine bPiDI-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow. Nicotine (10 µM) was added to the buffer, and samples collected for 36 min to determine bPiDI-induced inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow. A control slice in each experiment was superfused for 36 min in the absence of bPiDI, followed by nicotine, to determine nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow. Repeated measures analysis was employed such that each concentration of bPiDI was evaluated using striatal slices from each individual rat; striatum (∼80 mg) was of sufficient size to allow repeated measures evaluation. Liquid scintillation spectrometry was employed to determine the amount of [3H] in superfusate and tissue samples.

Mechanism of bPiDI inhibition was determined using Schild analysis and α6β2 nAChR receptor interaction via additivity with α-CtxMII. Concentration response for nicotine was determined in the absence and presence of a single concentration of bPiDI using slices from a single rat. bPiDI inhibition was determined at 0.18, 1.8 and 10 µM. After 36 min of superfusion with and without bPiDI, one of six nicotine concentrations (0.1–100 µM) was added to the buffer and superfusion continued for 36 min. Each slice from a single rat was exposed to only one nicotine and one bPiDI concentration. Thus, a repeated-measures design was used to determine nicotine concentration response, and bPiDI concentration was a between-group factor. To determine if bPiDI interacts with α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs, maximally inhibitory concentrations of α-CtxMII (1 nM), bPiDI (1 µM), or α-CtxMII and bPiDI concurrently were superfused for 36 min in duplicate. Concentrations were chosen from concentration–response curves (Dwoskin et al., 2008). Slices were superfused for 36 min in the absence of antagonist, followed by superfusion with 10 µM nicotine (nicotine control). To determine maximal inhibition produced by blockade of nAChRs, slices were superfused with mecamylamine (10 µM; Teng et al., 1997), an antagonist at all known nAChRs. A repeated-measures design was used for this series of experiments.

bPiDI inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release was assessed in rats treated with repeated doses of nicotine (0.4 mg·kg−1, s.c.) or saline daily for 10 days, and locomotor activity was measured for 60 min immediately after injection. Striatal slices were obtained 24 h after the last injection. Concentration response for bPiDI (0.1 nM–10 µM) to inhibit [3H]dopamine overflow evoked by 10 µM nicotine was determined using the above protocol for bPiDI concentration response. Concentration of nicotine (10 µM) used to determine bPiDI inhibition was selected based on previous findings demonstrating that prior administration of nicotine (0.4 mg·kg−1, for 10 days) does not alter the concentration response for nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow (Smith et al., 2010). The latter findings are in agreement with earlier studies demonstrating that nicotine-evoked striatal dopamine release, either in vitro or in vivo, is not altered following repeated nicotine administration (Janson et al., 1991; Grilli et al., 2005).

Nicotine self-administration

Rats were trained to respond for food pellets (45 mg) by pressing one lever (active) in standard two-lever operant conditioning chambers (ENV-008, MED Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA). Jugular vein catheters were implanted in rats and, after 5 days for recovery, nicotine self-administration was initiated during daily 1 h sessions; rats were fed 15–20 g per day after behavioural sessions. Responding on the active lever [FR5 time out (TO) 20] resulted in simultaneous delivery of nicotine (0.03 mg·kg−1·infusion−1 over 5.9 s) and activation of cue lights for 20 s, which signalled a TO in which responding on either lever was not reinforced; inactive lever responses were recorded, but had no consequence. Behaviour was defined as stable once rats earned (i) ≥10 infusions per session; (ii) ≤20% variability in number of infusions earned; and (iii) a minimum of 2:1 active : inactive lever response ratio across three consecutive sessions. Effects of acute bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) and saline on nicotine self-administration were determined using a within-subjects Latin Square design. At least two maintenance sessions separated each drug session. In a separate series of experiments, effects of repeated bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) and saline on nicotine self-administration were determined using a between-subjects design. Rats were assigned randomly to receive 0, 1.94, 3.33 or 5.83 µmol·kg−1 of bPiDI for 7 consecutive sessions, followed by three sessions in which saline was administered.

Food-maintained responding

Rats were trained to respond for food pellets using the above methods, with the exceptions that no surgery was performed and a terminal FR5 TO180 schedule was used to approximate response rates obtained with nicotine self-administration. Rats received 20 g of food per day in the home cage. Effects of acute bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) and saline on responding for food were determined using a within-subjects design in two groups. One group was drug-naïve and the other group was treated with nicotine (0.4 mg·kg−1, s.c.) during 10 consecutive daily locomotor activity sessions prior to operant training, in order to model the nicotine exposure during acquisition of nicotine self-administration prior to evaluation of bPiDI. Effects of repeated bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) and saline on responding for food were determined in a group of drug-naïve rats using a between-subjects design similar to the nicotine self-administration procedures.

Data analysis

Data are presented as mean (±SEM). In [3H]dopamine overflow assays, fractional release was calculated by dividing [3H] in each sample by total tissue-[3H] at time of sample collection; fractional release was expressed as a percentage of basal [3H]outflow. Basal [3H]outflow was the average fractional release in the two samples before analogue addition to the buffer. Total [3H]overflow was the sum of the increase in fractional release above basal [3H]outflow resulting from drug exposure, with [3H]outflow for equivalent periods of drug exposure subtracted. bPiDI concentration–response curves were generated by nonlinear fit to the sigmoidal dose–response equation (variable slope): response = Bt + (Tp-Bt)/[1 + 10(logEC50–X)n], where X is log nicotine concentration and n is Hill slope. IC50 for bPiDI inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow was determined using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Effect of bPiDI on [3H]dopamine overflow and ability to inhibit nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow were analysed by one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (anova), with bPiDI concentration as a within-subjects factor (SPSS 15.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-way repeated-measures anova was performed to analyse the time course of bPiDI inhibition on nicotine-evoked fractional release with concentration as a between-groups factor and time as a within-subjects factor.

The mechanism by which bPiDI inhibits nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow was examined using Schild analysis. Nicotine concentration–response curves in the absence and presence of bPiDI were fit by nonlinear least-squares regression using a variable slope, sigmoidal function. To determine parallelism, slopes and X-axis intercepts were compared using one-way anova with bPiDI concentration as a between-groups factor. Dose ratio (Dr) for bPiDI was EC50 for nicotine in the presence of each bPiDI concentration, divided by EC50 for nicotine in the absence of bPiDI. Log (Dr–1) was plotted as a function of log bPiDI concentration, fit by linear regression, with the slope determined and linearity assessed using Prism 5.0.

Inhibitory effect of concomitant exposure to bPiDI and α-CtxMII was compared with inhibition produced by bPiDI or α-CtxMII alone using a one-way anova. A priori Student's t-tests compared [3H]overflow after either bPiDI or α-CtxMII alone with that following concomitant bPiDI and α-CtxMII, and compared [3H]overflow of all treatment groups with that following mecamylamine.

For repeated nicotine or saline administration, nicotine concentration–response and bPiDI concentration response were analysed using a two-way mixed anova with treatment (nicotine or saline) as a between-groups factor and concentration as a within-subjects factor. Concentration-response data were analysed as previously described. A priori Student's t-tests compared bPiDI inhibition between nicotine-treated and saline-control groups. Student's t-tests also were used to compare kinetic parameters for bPiDI inhibition (log IC50 and Imax) between nicotine-treated and saline-control groups

Data from behavioural experiments were analysed by one- or two-way repeated-measures anova, followed by post hoc Tukey's or Dunnett's tests as appropriate. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Materials

[3H]Dopamine (dihydroxyphenylethylamine, 3,4-[7-3H]) specific activity 28.0 Ci·mmoL−1) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). S-(-)-Nicotine ditartrate (nicotine), nomifensine maleate, pargyline hydrochloride and mecamylamine hydrochloride were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). TS-2 tissue solubilizer and scintillation cocktail were purchased from Research Products International (Mt. Prospect, IL, USA). Other assay buffer chemicals were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). α-CtxMII and bPiDI (Figure 1) were synthesized as described (Cartier et al., 1996; Ayers et al., 2002). bPiDI, mecamylamine and nicotine were dissolved in saline and administered (s.c., 1 mL·kg−1) 15 min prior to behavioural sessions. Nicotine solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4. Nicotine dose represents free base; bPiDI and mecamylamine doses represent salts.

Results

bPiDI inhibits nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow and endogenous dopamine release from rat striatum

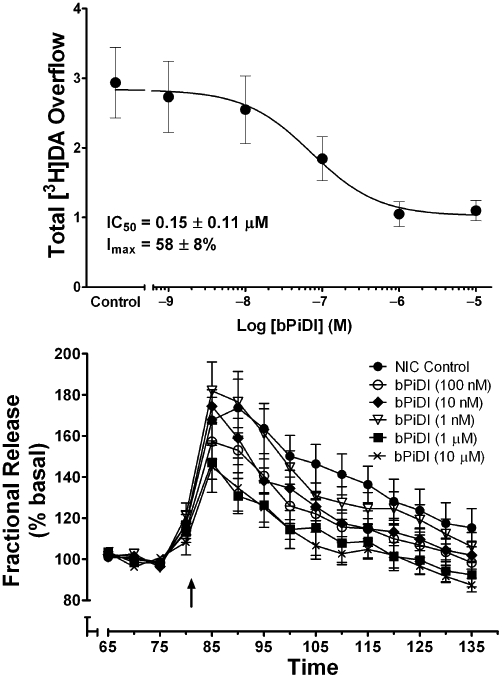

Initially, the effect of bPiDI to evoke [3H]dopamine overflow in the absence of nicotine was evaluated; however, bPiDI had no intrinsic activity, that is, did not evoke [3H]dopamine overflow, as expected of an antagonist (Supporting Information Table S1). In the same experiments, the ability of bPiDI to inhibit nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow was determined. A one-way anova revealed that bPiDI (1 nM–10 µM) inhibited nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release from superfused rat striatal slices in a concentration-dependent manner (F(5,25) = 6.55, P < 0.001; Figure 2A). bPiDI potently, but incompletely, inhibited nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow (IC50 = 150 ± 110 nM, Imax = 58 ± 8%). Analysis of the time course using two-way repeated measures anova revealed a main effect of concentration [F(5,32) = 2.88, P < 0.05; Figure 2B], a main effect of time [F(14 448) = 81.4, P < 0.0001] and a concentration × time interaction [F(70 448) = 1.67, P < 0.0001]. Post hoc analysis revealed that the 1 and 10 µM concentrations of bPiDI inhibited nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow beginning with the seventh sample after nicotine was added to the buffer and until the 10th sample was collected.

Figure 2.

Concentration dependence of N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI) inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow from superfused rat striatal slices. (A) Striatal slices were superfused in the absence or presence of bPiDI for 36 min and then for an additional 36 min with nicotine (10 µM) added to the buffer. Control represents [3H]dopamine overflow in response to 10 µM nicotine in the absence of bPiDI. Concentration response curve was generated by nonlinear regression. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM total [3H]dopamine overflow as a percentage of tissue-[3H] content; n = 6 rats. (B) Time course of bPiDI-induced inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow. Time course data were used to generate [3H]dopamine overflow data for bPiDI. Arrow indicates the time point at which nicotine was added to the superfusion buffer. Data are expressed as fractional release as a percentage of corresponding basal samples; n = 6 rats. Mean basal [3H]outflow was 0.79 ± 0.02 fractional release as percentage of tissue [3H]content. DA, dopamine.

A Schild analysis was performed to determine the mechanism of bPiDI inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow. bPiDI (0.18, 1.8 and 10 µM) shifted the nicotine concentration-effect curve to the right in a concentration-dependent manner, and inhibition was surmounted by increasing concentrations of nicotine (Figure 3). While the slopes of the linear portions of the curves were not different [F(3,18) = 0.26, P = 0.85], differences in the X-axis intercepts were obtained [F(3,18) = 4.07, P < 0.05], indicative of parallel curves. A linear fit (r2 = 1.00) to the Schild-transformed data (Figure 3, inset) revealed a slope of the Schild regression (1.48 ± 0.10) different from unity [t(10) = 45.53, P < 0.0001]. Together, these results are consistent with bPiDI exhibiting a surmountable allosteric inhibition (Kenakin, 1992).

Figure 3.

Schild analysis of N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI) inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow from superfused rat striatal slices. Assay buffer contained nomifensine (10 µM) and pargyline (10 µM) throughout superfusion. After collection of the second sample, slices were superfused with buffer in the absence and presence of bPiDI (0.18, 1.8 or 10 µM) for 36 min before the addition of nicotine (0.1–100 µM) to the buffer, and superfusion was continued for an additional 36 min. For each nicotine concentration, the control response is that for nicotine in the absence of bPiDI. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of total [3H]overflow during the 36-min exposure to nicotine in the absence and presence of bPiDI; n = 4 rats/bPiDI concentration; control, n = 12 rats (bPiDI was between-groups factor, control was contemporaneous with each bPiDI concentration). Concentration–response curves were generated by nonlinear regression. Inset shows the Schild regression in which log (dr–1) was plotted as a function of log [bPiDI] and data were fit by linear regression. DA, dopamine.

Assays determined if bPiDI inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release accurately reflects inhibition of nicotine-evoked endogenous dopamine release. Nicotine (10 and 30 µM) evoked endogenous dopamine overflow (Supporting Information Figure S1A). Neither bPiDI nor mecamylamine evoked dopamine release in the absence of nicotine (Supporting Information Figure S1B). Both bPiDI and mecamylamine inhibited nicotine (30 µM)-evoked endogenous dopamine overflow (Supporting Information Figure S1A,B).

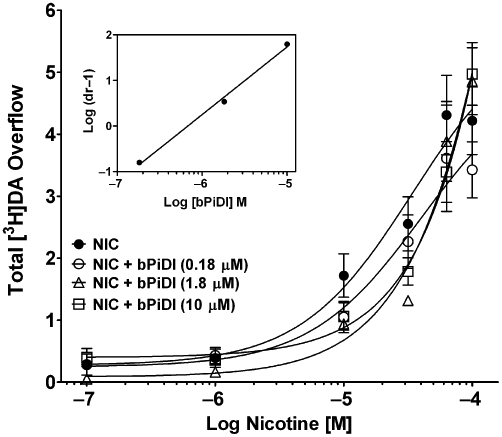

bPiDI interacts with α-CtxMII-sensitive α6β2-containing nAChR subtypes

To determine if bPiDI interacts with α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs, the effect of concomitant exposure of rat striatal slices to maximally inhibitory concentrations of bPiDI (1 nM) and α-CtxMII (1 nM) was compared with the effect of each antagonist alone. One-way anova revealed an effect of antagonist [F(3,19) = 32.30, P < 0.0001; Figure 4A], and post hoc analysis revealed that nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow in the presence of antagonist was different from nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow in the absence of antagonist (within-subject control). Inhibition produced by mecamylamine was greater than that produced by bPiDI, α-CtxMII or the combination of the two antagonists [t(10) = 5.46; t(9) = 2.75; t(9) = 3.69, all P < 0.05; Figure 4A]. Inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow resulting from concomitant exposure to both bPiDI and α-CtxMII was not different (P > 0.05) from that produced by either antagonist alone, indicating that bPiDI interacts with α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChR subtypes. The time course of the inhibitory effect of the antagonists shows that inhibition following concomitant exposure was not different from that following bPiDI or α-CtxMII alone (Figure 4B). Analysis of the time course revealed a main effect of antagonist [F(4,25) = 15.1, P < 0.0001], a main effect of time [F(9,225) = 46.9, P < 0.0001] and a concentration × time interaction [F(36,225) = 3.39, P < 0.0001].

Figure 4.

Concomitant exposure to concentrations of N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI) and α-CtxMII produces inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow not different from that after exposure to either antagonist alone. (A) Striatal slices were superfused in the absence or presence of mecamylamine (MEC; 10 µM), α-CtxMII (1 nM), bPiDI (1 µM), or α-CtxMII + bPiDI for 36 min. Superfusion continued for an additional 36 min following addition of nicotine (10 µM) to the buffer. Control represents nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow in the absence of antagonist. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of % basal fractional release. * indicates significant difference from control (nicotine alone; P < 0.05). # indicates significant difference from all other antagonist conditions. n = 6 rats. (B) Time course of nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine fractional release in the absence and presence of MEC, bPiDI, α-CtxMII or α-CtxMII + bPiDI. Data are expressed as fractional release as a percent of basal [3H]outflow. Arrow indicates the time point at which nicotine was added to the superfusion buffer. Mean basal [3H]outflow was 1.14 ± 0.02 fractional release as percentage of tissue [3H]content. DA, dopamine.

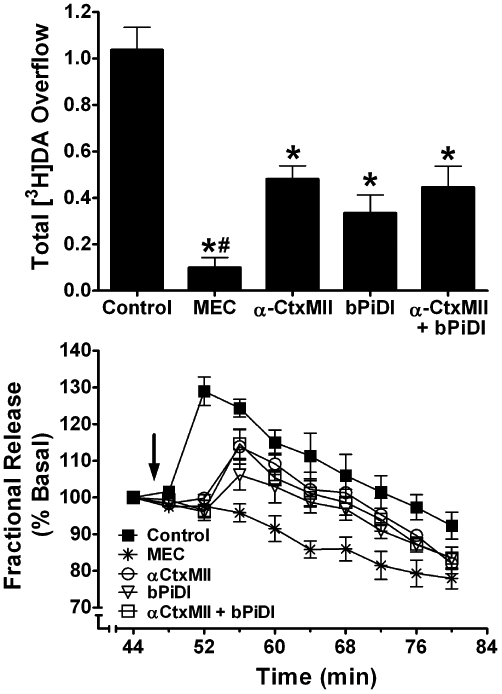

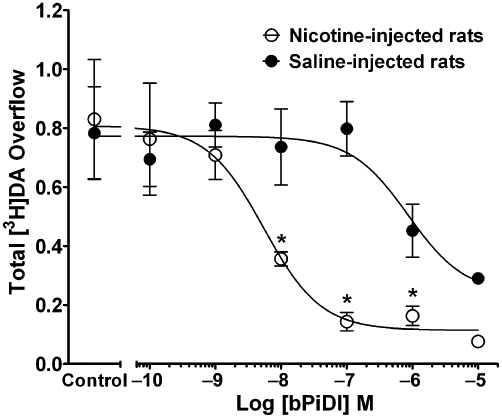

Repeated nicotine treatment increases the potency of bPiDI to inhibit nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release

Repeated administration of nicotine (0.4 mg·kg−1, s.c. once daily for 10 days) was found previously to not alter the concentration–response for nicotine to evoke [3H]dopamine overflow from rat striatal slices (Smith et al., 2010). The current study determined the concentration response for bPiDI to inhibit nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine overflow from striatal slices obtained from rats repeatedly given either nicotine or saline. A two-way mixed anova revealed main effects of prior nicotine treatment [F(1,66) = 8.43, P < 0.05] and bPiDI concentration [F(6,66) = 11.42, P < 0.05], as well as an interaction [F(6,66) = 3.24, P < 0.01; Figure 5]. The concentration–response curve for bPiDI was shifted to the left about 100-fold, following repeated nicotine treatment [IC50 = 1.45 ± 0.71 nM for nicotine-treated rats, and 179 ± 97 nM for saline-treated rats; t(6) = 3.19; P < 0.05]. Imax for the nicotine-treated group was greater than that for the saline-injected group [82 ± 5% vs. 57 ± 6%, respectively; t(11) = 3.18, P < 0.001]. Thus, repeated nicotine treatment increased both the potency and inhibitory activity of bPiDI.

Figure 5.

Repeated nicotine treatment increases the potency and inhibitory activity of N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI). Rats were given nicotine (0.4 mg·kg−1·day−1, s.c., for 10 days) or saline. Twenty-four hours after the last injection, the concentration response for bPiDI (0.1 nM–10 µM) to inhibit nicotine (10 µM)- [3H]dopamine overflow was determined. Slices were superfused with buffer in the absence and presence of bPiDI (0.1–10 µM) for 36 min before the addition of nicotine (10 µM) to the buffer; superfusion continued for 36 min. Control represents [3H]dopamine overflow in response to 10 µM nicotine in the absence of bPiDI. Data are mean ± SEM total [3H]dopamine overflow. n = 6 nicotine-treated rats and n = 7 saline-treated rats. Concentration-response curves were generated by nonlinear regression. * Indicates significant difference between repeated nicotine and repeated saline control groups (P < 0.05). DA, dopamine.

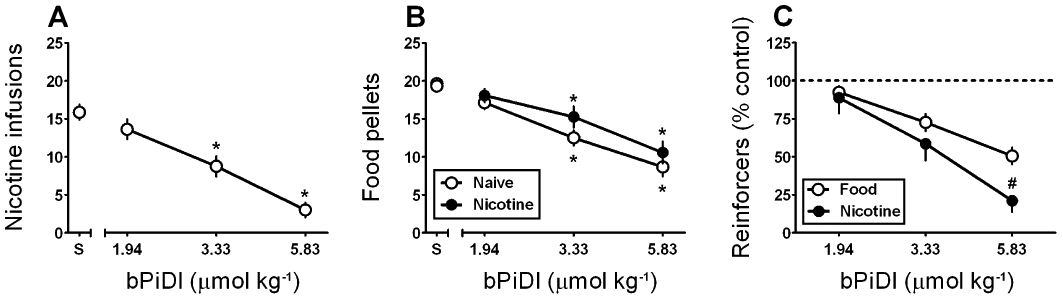

Acute bPiDI attenuates nicotine self-administration and food-maintained responding

Effects of acute pretreatment with bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) or saline on nicotine (0.03 mg·kg−1·infusion−1) self-administration were determined under a FR5 TO20 schedule. anova revealed a main effect of bPiDI dose [F(3,21) = 20.23, P < 0.001]; post hoc Dunnett's tests confirmed that bPiDI (3.33 and 5.83 µmol·kg−1; P < 0.01 and 0.001, respectively) decreased the number of nicotine infusions earned compared with saline (Figure 6A), without altering the number of responses on the inactive lever (data not shown). To determine specificity, the acute effect of bPiDI on responding for food was determined under a FR5 TO180 schedule (note the use of a longer TO in order to approximate response rates of nicotine self-administration) in drug-naive and nicotine (0.4 mg·kg−1·day−1 for 10 days)-treated rats. While the effect of bPiDI did not differ between groups, a main effect of bPiDI dose was found in both the drug-naïve [F(3,15) = 20.61, P < 0.001] and nicotine-treated [F(3,15) = 18.38, P < 0.001] groups. Post hoc tests confirmed that bPiDI (3.33 and 5.83 µmol·kg−1) decreased the number of pellets earned in each group compared with control (Figure 6B). To directly compare the effects of acute bPiDI on the two types of reinforcement, the number of nicotine infusions or food pellets was expressed as percentage of the respective saline control values. The highest dose of bPiDI (5.83 µmol·kg−1) reduced nicotine self-administration to a greater extent compared with food-maintained responding (P < 0.05; Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Acute N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI) preferentially reduces nicotine self-administration relative to food-maintained responding. (A) Effect of bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) on mean (±SEM) number of nicotine (0.03 mg·kg−1·infusion−1) infusions earned (n = 8 rats) (*P < 0.05 vs. saline; S). (B) Effect of bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) on mean (±SEM) number of food pellets earned in drug-naïve rats (n = 6, open symbols) or rats (n = 6, filled symbols) that were treated with nicotine (0.4 mg·kg−1, s.c.) for 10 days prior to operant training (*P < 0.05 vs. saline; S). (C) Effects of acute bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) on nicotine self-administration or food-maintained responding (food-maintained responding data represent the group average of drug-naïve and nicotine-treated rats presented in panel B) expressed as % saline control values. (# P < 0.05 vs. the effect of bPiDI on food-maintained responding).

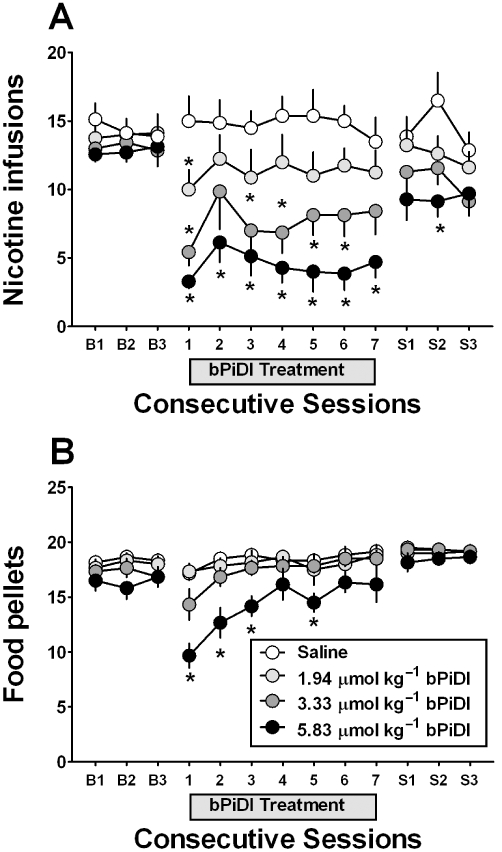

Following repeated administration, tolerance develops to the inhibitory effect of bPiDI on food-maintained responding, but not to the inhibitory effect on nicotine self-administration

A between-subjects design was employed to determine if the acute effects of bPiDI on nicotine self-administration and food-maintained responding were altered with repeated bPiDI administration. Once stable rates of nicotine self-administration were achieved, rats were assigned randomly to receive 1.94, 3.33 or 5.83 µmol·kg−1 of bPiDI (s.c.) or saline once daily for 7 days, followed by an additional three saline pretreatment sessions. During the three baseline sessions prior to drug treatment, the ratios of active : inactive lever responses were 3.96, 7.53, 6.93 and 4.88 for rats treated with saline, 1.94 µmol·kg−1 group, 3.3 µmol·kg−1 group and 5.8 µmol·kg−1 group, respectively, confirming that the allocation of responses was biased towards the active lever. With respect to the number of nicotine infusions earned, anova revealed a dose × day interaction [F(36,312) = 2.80, P < 0.001; Figure 7A]. Post hoc tests revealed decreases in the number of nicotine infusions earned following 1.94 µmol·kg−1 on day 1, 3.3 µmol·kg−1 on days 1 and days 3–6, and 5.8 µmol·kg−1 on days 1–7. Further, a separate anova confirmed that the effect of bPiDI was specific to the active lever {dose × lever interaction [F(3,52) = 4.95, P < 0.01; results not shown]}. Importantly, nicotine self-administration returned to baseline levels within 1 day following the final bPiDI treatment session. There was no significant difference in body weight between rats given bPiDI or saline repeatedly, indicating no overt toxicity.

Figure 7.

With repeated administration N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI) reduces nicotine self-administration but not food-maintained responding. (A) Effect of bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.; a single dose of bPiDI was given to each group) given once daily for 7 days on nicotine self-administration to rats (n = 7–8 per dose group) following three consecutive baseline sessions (‘B1’–‘B3’) and followed by three additional saline pretreatment sessions (‘S1’–‘S3’). (B) Effect of bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1, s.c.) on food-maintained responding given repeatedly for 7 days to rats (n = 6 per dose group) following three consecutive baseline sessions (‘B1’–‘B3’) and followed by 3 additional saline pretreatment sessions (‘S1’–‘S3’). (*P < 0.05 vs. saline).

Additional groups of rats trained to respond for food pellets under a FR5 TO180 schedule were assigned randomly to receive pretreatment with bPiDI (1.94–5.83 µmol·kg−1) or saline for seven daily sessions, followed by an additional three saline treatment sessions. Results revealed a dose × day interaction [F(36,240) = 5.48, P < 0.01; Figure 7B], but post hoc tests indicated that only 5.8 µmol·kg−1 decreased the number of food pellets earned on days 1–3 and day 5. Thus, with repeated administration, tolerance developed to the initial bPiDI-induced decrease in food-maintained responding, whereas no tolerance developed to the decrease in nicotine self-administration.

Discussion

Previous research by our laboratory demonstrated the ability of a series of N,N-alkane-diyl-bis-3-picolinium compounds, including bPiDI, to inhibit nicotine-evoked total [3H]dopamine release from rat striatal slices (Dwoskin et al., 2008). The current study replicates these findings by reporting that bPiDI potently inhibits (IC50 = 150 nM) nicotine-evoked dopamine release from rat striatal slices, although the inhibition was not complete (Imax = 53–57%). In contrast, the non-selective nAChR antagonist, mecamylamine, completely inhibited (>90%) nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release, which suggests that bPiDI acts at a subset of nAChRs mediating this effect. Further, the present results extend our previous study by elucidating the mechanism of action of bPiDI. Schild analysis revealed rightward shifts in the nicotine concentration–response curve with nicotine overcoming the bPiDI inhibition, and a linear fit of the Schild-regression revealed a slope different from unity. The current results are consistent with a surmountable allosteric mechanism and may be due to the presence of spare receptors (i.e. maximum response is obtained with <100% of available receptors occupied; Stephenson, 1956; Wenger et al., 1997). Allosteric antagonists produce rightward and downward shifts in the agonist concentration response; however, with spare receptors, the probability of activation of a sufficient number of receptors for obtaining maximal response increases as agonist concentration increases (Zhu, 1993; Agneter et al., 1997).

Several different subtypes of nAChRs mediate nicotine-evoked dopamine release in striatum. Studies using knockout mice have confirmed the critical role of β2-containing nAChRs in mediating nicotine-evoked dopamine release (Picciotto et al., 1998). Comprehensive molecular genetics studies suggest that four α-CtxMII-sensitive subtypes (i.e. α6β2*, α6β2β3*, α4α6β2* and α4α6β2β3*), and two α-CtxMII-insensitive subtypes (i.e. α4β2* and α4α5β2*), mediate nicotine-evoked striatal dopamine release (Salminen et al., 2004; Gotti et al., 2005). The α4α6β2β3* subtype constitutes ∼50% of α6-containing nAChRs on striatal dopaminergic terminals in mice and has the highest sensitivity to nicotine of any native nAChR (Grady et al., 2007; Salminen et al., 2007). The incomplete maximal inhibition produced by bPiDI is consistent with incomplete inhibition produced by α-CtxMII (Kulak et al., 1997; Azam and McIntosh, 2005), suggesting that bPiDI is a small molecule acting at α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs. Moreover, concomitant exposure of rat striatal slices to maximally effective concentrations of bPiDI (1 µM) and α-CtxMII (1 nM) did not result in greater inhibition of nicotine-evoked dopamine release compared with that produced by either antagonist alone, suggesting that bPiDI and α-CtxMII inhibit the same nAChR subtype(s). These results are interpreted to suggest that the inhibition produced by bPiDI is mediated by α6-containing nAChRs. Thus, bPiDI is a high potency and selective antagonist at α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs (i.e. α6β2*, α6β2β3*, α4α6β2* and/or α4α6β2β3*) that appear to mediate 60–70% of the response to nicotine in rat dorsal striatum.

With repeated nicotine treatment (0.4 mg·kg−1·day−1, 10 days), the concentration response for bPiDI to inhibit nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine release was shifted to the left by about 100-fold, with a 25% increase in Imax, compared with the control group. Studies suggest that repeated nicotine treatment or long-term nicotine exposure alters nAChR stoichiometry, conformation and composition (Harkness and Millar, 2002; Nelson et al., 2003; Lopez-Hernandez et al., 2004; McCallum et al., 2006; Visanji et al., 2006; Drenan et al., 2008), and receptor maturation by increasing subunit oligomerization and folding (Sallette et al., 2005; Corringer et al., 2006; Lester et al., 2009). The majority of the latter studies employed relatively high nicotine doses, constant nicotine infusions or long exposures of nicotine to cell cultures, limiting generalization of such receptor changes to the current study. Phosphorylation of specific amino acid residues in the nAChR structure by protein kinase A and C occurs in response to repeated or prolonged nicotine, which modulates the sensitivity of the receptors to ligands (Giniatullin et al., 2005; Picciotto et al., 2008). Studies show that repeated activation of α4* nAChRs results in receptor upregulation, whereas α6* nAChRs do not upregulate (Mugnaini et al., 2006; Perry et al., 2007; Perez et al., 2009), although mice with hypersensitive midbrain α6 nAChRs show exaggerated responses to nicotine probably due to high affinity interactions (Tapper et al., 2004; 2007; Perry et al., 2007; Drenan et al., 2008). Therefore, α-CtxMII-sensitive nAChRs may be regulated differentially depending on α4-subunit inclusion. Alternatively, repeated nicotine treatment is thought to shift nAChRs through different receptor states, and large shifts in ligand affinity accompany changes in receptor state (Dani and Heinemann, 1996; Marks et al., 2004; Picciotto et al., 2008). Thus, rather than interacting with an alternate subtype composition following repeated nicotine, bPiDI may stabilize or ‘lock’ the receptor subtype(s) into a high affinity state, consistent with the large potency shift for bPiDI following repeated nicotine.

Acute administration of bPiDI resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in the number of nicotine self-infusions earned. Similarly, mecamylamine and DHβE (nAChR antagonists), varenicline and sazetidine-A (nAChR partial agonists), and UCI-30002 (a nAChR negative allosteric modulator) decrease nicotine self-administration (Watkins et al., 1999; Yoshimura et al., 2007; Levin et al., 2010; O'Connor et al., 2010). However, in contrast with findings showing that mecamylamine and DHβE do not alter food-reinforced responding (Corrigall et al., 1988; Dwoskin et al., 2008), acute bPiDI administration decreased the number of food pellets earned, albeit to a lesser extent than the reduction in the number of nicotine infusions, suggesting that bPiDI is not an entirely ‘neutral’ antagonist. However, it is worth noting that similar results have been obtained in evaluations of medications currently approved for smoking cessation. For instance, the monoamine uptake inhibitor bupropion significantly decreased sucrose-maintained responding at a dose of 26 mg·kg−1, whereas a higher dose of 78 mg·kg−1 was necessary to attenuate nicotine self-administration (Rauhut et al., 2003). In contrast to bupropion, bPiDI preferentially decreased nicotine self-administration relative to food-maintained responding, suggesting that any potential off-target actions of bPiDI are unlikely to prevent clinical efficacy. Although bPiDI decreases nicotine-induced locomotor activity in nicotine-sensitized rats, bPiDI did not significantly alter activity when given alone (i.e. without nicotine; Dwoskin et al., 2008), and did not alter responding on the inactive lever in the current self-administration study, providing further evidence that general decreases in activity are not responsible for the decrease in nicotine self-administration. Finally, in addition to the observed antagonism of nAChRs in brain, which supports a centrally mediated action, bPiDI is distributed rapidly to brain and is detectable by high pressure liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry for 5–90 min following s.c. injection of 3.3 µmol·kg−1 of bPiDI (our unpublished observations).

The bPiDI-induced decrease in nicotine self-administration was maintained across seven daily treatments, whereas tolerance developed to the decrease in food-maintained responding. However, the highest dose of bPiDI (5.8 µmol·kg−1) decreased food-maintained responding on treatment days 1–3 and 5, suggesting that tolerance to the highest dose was not complete. Thus, the traditional approach of testing separate groups of rats with either nicotine or food was employed in the current study. One caveat in comparing across nicotine self-administration and food-maintained responding studies is that food-maintained responding was evaluated in the absence of any history of exposure to nicotine. While this may be minimized by using a multiple schedule of reinforcement in which the rats can earn either nicotine or food during different components within the same session, the multiple schedule requires extensive training and is typically less sensitive to classical antagonists such as mecamylamine (Stairs et al., 2010). Moreover, the ability of classical nAChR antagonists to decrease both nicotine- and food-maintained responding following repeated administration has not been reported in the literature. Also, future studies will be necessary to determine if bPiDI inhibition of nicotine self-administration is specific (e.g. inhibits self-administration of other psychostimulants) and if bPiDI attenuates cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking.

In conclusion, recent evidence from studies using genetically altered mice has revealed a critical role for α6β2* nAChRs in the reinforcing effects of nicotine, as mice lacking α6β2* nAChRs do not self-administer nicotine (Pons et al., 2008), and infusion of α-CtxMII into NAcc decreases nicotine intake in rats (Brunzell et al., 2009). The current results showed that bPiDI attenuated nicotine-evoked striatal dopamine release, inhibited α-CtxMII-sensitive α6β2* nAChRs via a surmountable allosteric mechanism and increased inhibitory potency 100-fold in nicotine-sensitized rats. Importantly, bPiDI decreased nicotine self-administration, and tolerance did not develop to this effect following repeated administration. Furthermore, no overt signs of toxicity (body weight loss or lethargy) were evident following repeated administration of behaviourally relevant bPiDI doses. Thus, the current findings demonstrate that bPiDI is a non-toxic, systemically active, small molecule, α6β2*-selective nAChR antagonist that specifically decreases nicotine self-administration. The current results support the hypothesis that α6β2* nAChRs have an important role in the abuse-related effects of nicotine. Antagonism of α6β2* nAChRs provides a new direction for the development of medications to reduce nicotine abuse (Dwoskin and Bardo, 2009).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants U19 DA017548 (LPD), R01 MH53631 and P01 GM48677 (JMM), T32 DA007304 (AMS) and F31 DA023853 (TEW). We thank Sangeetha Sumithran, Emily Denehy, Jason Ross, Lindsay Pilgrim and Matthew Joyce for their assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- bPIDDB

N,N′-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-picolinium dibromide

- bPiDI

N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide

- DHβE

dihydro-β-erythroidine

- FR5

fixed ratio 5

- NAcc

nucleus accumbens

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- s.c

subcutaneous

- TO180

180 min timeout

- TO20

20 min timeout

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- α-CtxMII

α-conotoxin MII

Conflict of interest

The University of Kentucky holds a patent on N,N-decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide, and a potential royalty stream to LPD and PAC may occur consistent with University of Kentucky policy. The other authors have no disclosures.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 N,N′-Decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI) inhibits nicotine-evoked endogenous dopamine (DA) overflow from superfused rat striatal slices. Basal outflow was average fractional release during the initial 10 min period prior to addition of drug to the buffer. Total dopamine overflow was the sum of increases in fractional release above basal during superfusion with drug. (A) Striatal slices were superfused in the absence or presence of bPiDI (20 µM) or mecamylamine (MEC; 30 µM) for 40 min and then for an additional 40 min with nicotine (30 µM) added to the buffer. Superfusion buffer contained nomifensine (10 µM) and pargyline (10 µM) throughout the experiment. Control represents dopamine overflow in response to 30 µM nicotine in the absence of bPiDI or mecamylamine. There were no differences in dihydroxyphenylacetic acid concentrations between the treatment conditions. Samples (1 mL) were collected into 100 µL of 0.1 M perchloric acid and processed immediately following collection. * indicates that both bPiDI (t12 = 2.53, P < 0.05) and mecamylamine (t12 = 2.80, P < 0.05) inhibited nicotine-evoked endogenous dopamine overflow. (B) Time course of bPiDI-induced inhibition of nicotine-evoked dopamine fractional release. Neither bPiDI nor mecamylamine evoked dopamine release when slices were exposed to these antagonists in the absence of nicotine (10–40 min). Data are expressed as fractional dopamine release (pg·mL−1·min−1; mean ± SEM), n = 6 rats.

Table S1 N,N′-Decane-1,10-diyl-bis-3-picolinium diiodide (bPiDI) does not evoke [3H]DA overflow from superfused rat striatal slices

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Agneter E, Singer EA, Sauermann W, Feuerstein TJ. The slope parameter of concentration-response curves used as a touchstone for the existence of spare receptors. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 1997;356:283–292. doi: 10.1007/pl00005052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl. 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers JT, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Grinevich VP, Zhu J, Crooks PA. bis-Azaaromatic quaternary ammonium analogues: ligands for alpha4beta2* and alpha7* subtypes of neuronal nicotinic receptors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:3067–3071. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00687-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam L, McIntosh JM. Effect of novel alpha-conotoxins on nicotine-stimulated [3H]dopamine release from rat striatal synaptosomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:231–237. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.071456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell DH, Boschen KE, Hendrick ES, Beardsley PM, McIntosh JM. Alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell regulate progressive-ratio responding maintained by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;35:665–673. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillé S, Guillem K, Cador M, Manzoni O, Georges F. Voluntary nicotine consumption triggers in vivo potentiation of cortical excitatory drives to midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10410–10415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2950-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier GE, Yoshikami D, Gray WR, Luo S, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM. A new α-conotoxin which targets α3β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7522–7528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Han ZY, Bessis A, Rossi FM, Zoli M, Marubio L, et al. Distribution and pharmacology of alpha 6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed with mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1208–1217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01208.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Herling S, Coen KM. Evidence for opioid mechanisms in the behavioral effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;96:29–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02431529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Franklin KB, Coen KM, Clarke PB. The mesolimbic dopaminergic system is implicated in the reinforcing effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:285–289. doi: 10.1007/BF02245149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Adamson KL. Self-administered nicotine activates the mesolimbic dopamine system through the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 1994;653:278–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corringer PJ, Sallette J, Changeux JP. Nicotine enhances intracellular nicotinic receptor maturation: a novel mechanism of neural plasticity? J Physiol. 2006;99:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA, Heinemann S. Molecular and cellular aspects of nicotine abuse. Neuron. 1996;16:905–908. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca MA, Spina L, Cadoni C, et al. Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Suppl 1):227–241. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, McClure-Begley T, McKinney S, Miwa JM, et al. In vivo activation of midbrain dopamine neurons via sensitized, high-affinity alpha 6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron. 2008;60:123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwoskin LP, Bardo MT. Targeting nicotinic receptor antagonists as novel pharmacotherapies for tobacco dependence and relapse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:244–246. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwoskin LP, Wooters TE, Sumithran SP, Siripurapu KB, Joyce BM, Lockman PR, et al. N,N′-Alkane-diyl-bis-3-picoliniums as nicotinic receptor antagonists: inhibition of nicotine-evoked dopamine release and hyperactivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:563–576. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.136630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exley R, Clements MA, Hartung H, McIntosh JM, Cragg SJ. Alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors dominate the nicotine control of dopamine neurotransmission in nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2158–2166. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniatullin R, Nistri A, Yakel JL. Desensitization of nicotinic ACh receptors: shaping cholinergic signaling. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Moretti M, Clementi F, Riganti L, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, et al. Expression of nigrostriatal alpha 6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors is selectively reduced, but not eliminated, by beta 3 subunit gene deletion. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:2007–2015. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Salminen O, Laverty DC, Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, et al. The subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on dopaminergic terminals of mouse striatum. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli M, Parodi M, Raiteri M, Marchi M. Chronic nicotine differentially affects the function of nicotinic receptor subtypes regulating neurotransmitter release. J Neurochem. 2005;93:1353–1360. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinevich VP, Crooks PA, Sumithran SP, Haubner AJ, Ayers JT, Dwoskin LP. N-n-alkylpyridinium analogs, a novel class of nicotinic receptor antagonists: selective inhibition of nicotine-evoked [3H] dopamine overflow from superfused rat striatal slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:1011–1020. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.051789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness PC, Millar NS. Changes in conformation and subcellular distribution of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors revealed by chronic nicotine treatment and expression of subunit chimeras. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10172–10181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10172.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Qin M, Liu ZH. Primary reinforcing effects of nicotine are triggered from multiple regions both inside and outside the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci. 2006;26:723–730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4542-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Janson AM, Meana JJ, Goiny M, Herrera-Marschitz M. Chronic nicotine treatment counteracts the decrease in extracellular neostriatal dopamine induced by a unilateral transection at the mesodiencephalic junction in rats: a microdialysis study. Neurosci Lett. 1991;134:88–92. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90515-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin TP. Tissue response as a functional discriminator of receptor heterogeneity: effects of mixed receptor populations on Schild regressions. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:699–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SL, Caldarone BJ, Picciotto MR. Beta2-subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are critical for dopamine-dependent locomotor activation following repeated nicotine administration. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Suppl 1):132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulak JM, Nguyen TA, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM. Alpha-conotoxin MII blocks nicotine-stimulated dopamine release in rat striatal synaptosomes. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5263–5270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05263.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester HA, Xiao C, Srinivasan R, Son CD, Miwa J, Pantoja R, et al. Nicotine is a selective pharmacological chaperone of acetylcholine receptor number and stoichiometry. Implications for drug discovery. AAPS. 2009;11:167–177. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Rezvani AH, Xiao Y, Slade S, Cauley M, Wells C, et al. Sazetidine-A, a selective {alpha}4{beta2} nicotinic receptor desensitizing agent and partial agonist, reduces nicotine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:933–939. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.162073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Hernandez GY, Sanchez-Padilla J, Ortiz-Acevedo A, Lizardi-Ortiz J, Salas-Vincenty J, Rojas LV, et al. Nicotine-induced up-regulation and desensitization of alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptors depend on subunit ratio. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38007–38015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Rowell PP, Cao JZ, Grady SR, McCallum SE, Collins AC. Subsets of acetylcholine-stimulated 86Rb+ efflux and [125I]-epibatidine binding sites in C57BL/6 mouse brain are differentially affected by chronic nicotine treatment. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:1141–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum SE, Collins AC, Paylor R, Marks MJ. Deletion of the beta 2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alters development of tolerance to nicotine and eliminates receptor upregulation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:314–327. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubio LM, Gardier AM, Durier S, David D, Klink R, Arroyo-Jimenez MM, et al. Effects of nicotine in the dopaminergic system of mice lacking the alpha4 subunit of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1329–1337. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini M, Garzotti M, Sartori I, Pilla M, Repeto P, Heidbreder CA, et al. Selective down-regulation of [125I]α-conotoxin MII binding in rat mesostriatal dopamine pathway following continuous infusion of nicotine. Neuroscience. 2006;137:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi CH, Zhou Y, Lindstrom J. Alternate stoichiometries of alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:332–341. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer NM, Zhang Z, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP, Bardo MT. Effects of a novel nicotinic receptor antagonist, N,N′-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-picolinium dibromide, on nicotine self-administration and hyperactivity in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:426–434. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor EC, Parker D, Rollema H, Mead AN. The alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine-receptor partial agonist varenicline inhibits both nicotine self-administration following repeated dosing and reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;208:365–376. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Fu Y, McAllen K, Luo J, McIntosh JM, Lindstrom JM, et al. Up-regulation of brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the rat during long-term self-administration of nicotine: disproportionate increase of the alpha6 subunit. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:611–622. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez XA, Bordia T, McIntosh JM, Grady SR, Quik M. Long-term nicotine treatment differentially regulates striatal alpha6alpha4beta2* and alpha6(nonalpha4)beta2* nAChR expression and function. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:844–853. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez XA, O'Leary KT, Parameswaran N, McIntosh JM, Quik M. Prominent role of alpha3/alpha6beta2* nAChRs in regulating evoked dopamine release in primate putamen: effect of long-term nicotine treatment. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:938–946. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.053801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry DC, Mao D, Gold AB, McIntosh JM, Pezzullo JC, Kellar KJ. Chronic nicotine differentially regulates alpha6- and beta3-containing nicotinic cholinergic receptors in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:306–315. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Lena C, Marubio LM, Pich EM, et al. Acetylcholine receptors containing the beta2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature. 1998;391:173–177. doi: 10.1038/34413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Addy NA, Mineur YS, Brunzell DH. It is not ‘either/or’: activation and desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors both contribute to behaviors related to nicotine addiction and mood. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;84:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons S, Fattore L, Cossu G, Tolu S, Porcu E, McIntosh JM, et al. Crucial role of alpha4 and alpha6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from ventral tegmental area in systemic nicotine self-administration. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12318–12327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3918-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, Neugebauer NM, Zhang Z, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP, Bardo MT. The effects of a novel nicotinic receptor antagonist N,N′-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-picolinium dibromide (bPiDDB) on acute and repeated nicotine-induced increases in extracellular dopamine in rat nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:755–763. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauhut AS, Neugebauer NM, Dwoskin LP, Bardo MT. Effect of bupropion on nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;169:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallette J, Pons S, Devillers-Thiery A, Soudant M, Prado de Carvalho L, Changeux JP, et al. Nicotine upregulates its own receptors through enhanced intracellular maturation. Neuron. 2005;46:595–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC, et al. Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1526–1535. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Drapeau JA, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ, Grady SR. Pharmacology of alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors isolated by breeding of null mutant mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1563–1571. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.031492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AM, Pivavarchyk M, Wooters TE, Zhang Z, Zheng G, McIntosh JM, et al. Repeated nicotine administration robustly increases bPiDDB inhibitory potency at α6β2* nicotinic receptors that mediate nicotine-evoked dopamine release. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stairs DJ, Neugebauer NM, Bardo MT. Nicotine and cocaine self-administration using a multiple schedule of intravenous drug and sucrose reinforcement in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21:182–193. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833a5c9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson RP. A modification of receptor theory. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1956;11:379–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1956.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Nashmi R, Schwarz J, Deshpande P, Labarca C, et al. Nicotine activation of alpha4* receptors: sufficient for reward, tolerance, and sensitization. Science. 2004;306:1029–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.1099420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper AR, McKinney SL, Marks MJ, Lester HA. Nicotine responses in hypersensitive and knockout alpha 4 mice account for tolerance to both hypothermia and locomotor suppression in wild-type mice. Physiol Genomics. 2007;31:422–428. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00063.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng L, Crooks PA, Sonsalla PK, Dwoskin LP. Lobeline and nicotine evoke [3H]overflow from rat striatal slices preloaded with [3H]dopamine: differential inhibition of synaptosomal and vesicular [3H]dopamine uptake. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:1432–1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visanji NP, Mitchell SN, O'Neill MJ, Duty S. Chronic pre-treatment with nicotine enhances nicotine-evoked striatal dopamine release and alpha6 and beta3 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mRNA in the substantia nigra pars compacta of the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SS, Epping-Jordan MP, Koob GF, Markou A. Blockade of nicotine self-administration with nicotinic antagonists in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;62:743–751. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger BW, Bryant DL, Boyd RT, McKay DB. Evidence for spare nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and a beta 4 subunit in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells: studies using bromoacetylcholine, epibatidine, cytisine and mAb35. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:905–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteaker P, McIntosh JM, Luo S, Collins AC, Marks MJ. 125I-alpha-conotoxin MII identifies a novel nicotinic acetylcholine receptor population in mouse brain. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:913–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang KC, Jin GZ, Wu J. Mysterious alpha6-containing nAChRs: function, pharmacology, and pathophysiology. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30:740–751. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura RF, Hogenkamp DJ, Li WY, Tran MB, Belluzzi JD, Whittemore ER, et al. Negative allosteric modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors blocks nicotine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:907–915. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.128751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu BT. The competitive and noncompetitive antagonism of receptor-mediated drug actions in the presence of spare receptors. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1993;29:85–91. doi: 10.1016/1056-8719(93)90055-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumstein A, Karduck W, Starke K. Pathways of dopamine metabolism in the rabbit caudate nucleus in vitro. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1981;316:205–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00505651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.