SYNOPSIS

Despite the benefits of treatment for late-life depression, we are faced with the challenges of underutilization of mental health services by older adults and non-adherence to offered interventions. This paper describes psychosocial and interactional barriers and facilitators of treatment engagement among depressed older adults served by community health care settings. We describe the need to engage older adults in treatment using interventions that: 1. target psychological barriers such as stigma and other negative beliefs about depression and its treatment; and 2. increase individuals’ involvement in the treatment decision-making process. We then present personalized treatment engagement interventions that our group has designed for a variety of community settings.

Keywords: depression, geriatric, treatment engagement, adherence, community settings

Major depression affects 0.7–1.4% of community-dwelling older adults [1,2], with higher rates seen in settings in which medical illness, functional disability, and pain are more common. Thus, 6–9% of primary care patients [3,4], 12% of elderly receiving home-delivered meals [5], and 14% of elderly home healthcare patients suffer from major depression [6].

When treating older depressed adults, clinicians strive to provide appropriate pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions to alleviate suffering and promote recovery. In recent years, primary care-based collaborative care interventions have improved depression outcomes as compared to usual care [7–11]. Interventions that are delivered in community and home-based settings have also demonstrated improvement in depressive symptoms [12–15].

Despite the benefits of such treatment, we are frequently faced with the duel challenges of underutilization of mental health services by older adults and non-adherence to offered interventions. Many conceptual models highlight the importance of an individual’s selfidentification of distressing symptoms and subsequent decisions on whether and where to seek care (i.e., “help-seeking pathways”) [16–21]. We focus in this paper on an individual’s degree of engagement in depression treatment after a community case worker or health care professional has identified depression. We define treatment engagement broadly as a process beginning with identification of depression in community settings; moving to a referral for mental health evaluation; treatment decision-making and acceptance of treatment recommendations; and early adherence and participation in care. We focus in particular on older adults encountered in community settings, which include any non-mental health specialty setting such as aging services, primary care, and home health care. These are the settings in which older adults are commonly served and where untapped opportunities exist for identifying and treating depression.

Barriers and facilitators of engaging in mental health services exist on multiple levels (e.g., societal, agency, provider, individual). We focus in this paper on individual-level factors. In particular, psychosocial factors such as negative attitudes and beliefs about mental illness, and interactional factors such as lack of involvement in medical decision-making can undermine older adults’ acceptance of mental health interventions. These factors may also play a role in adherence to interventions, and ultimately in depression outcomes. Thus, in light of the evidence base for the care of depressed older adults, we describe the need for, and benefits of engaging older adults in treatment using interventions that: 1. target psychological barriers such as stigma and other negative beliefs about depression and its treatment; and 2. increase individuals’ involvement in the treatment decision-making process. We then present personalized treatment engagement interventions that our group has designed for a variety of community settings. These include 1. the Open Door intervention, which targets identification and referral of depressed community-dwelling older adults to mental health service providers; 2. a Shared Decision-Making approach (SDM) for primary care patients, which targets treatment selection [22]; and 3. the Treatment Initiation Program (TIP), which targets patient adherence to pharmacologic depression treatment recommendations by primary care physicians [23].

Personalized research: a focus on the individual

As outlined in “The Road Ahead: Research Partnership to Transform Services,” equitable access is fundamental to fair mental healthcare service delivery. Elders are less likely than younger adults to use mental health services [24] and African American adults and elderly have the lowest rates of mental health service use, even when education and income level are accounted for [25]. Additionally, when elders do engage in care they are less likely to use specialty mental health facilities [26,25]. This reduces the number of venues where care may be obtained. There are many barriers to engaging older adults in mental health care. Barriers can emerge from individual (e.g., attitudes, mobility), interactional (e.g., involvement with health care professionals), systemic (e.g., availability of mental health care, lack of parity), and societal factors (e.g., ageism, stigma). By targeting the individual and his/her interaction with community workers and health care professionals, as we do in this paper, we are in a position to implement interventions targeting specific person by person factors that affect engagement in care.

In an overview of National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) priorities, there is a renewed interest in the individual perspective and the impact of psychosocial factors. The clinical vision offered by NIMH [27] outlines the four “Ps” of medical research: prediction, pre-emption, personalization, and participation. To personalize research is to highlight “individual biological, environment, and social factors” and develop interventions that are targeted to the needs of the individual. This new emphasis may pave the way for greater attention to personal and psychological perspectives on mental illness. When we consider older persons’ use of mental health services and treatments, we can view their personal choices as driven in part by social-psychological factors that either hinder or facilitate quality care.

Models relevant to mental health treatment engagement and care

A number of conceptual models identify factors relevant to help-seeking in general, and to treatment engagement in particular. As mentioned above, our focus is on treatment engagement after a community case worker or health care professional has identified depression. We define treatment engagement broadly from initial identification of need and referral for mental health evaluation through early adherence and participation in care. The Anderson Behavioral Model of Health Service Use proposes that need, enabling factors, and predisposing factors affect use of services [28,29]. In short, need reflects both perceived and evaluated symptoms. In community settings, a community worker or health care professional may identify the need and refer older adults for further evaluation or treatment, which may take place in either health or mental health settings. Enabling factors include family and community resources. Predisposing factors are demographic characteristics and health beliefs such as attitudes toward health services. Later updates to the Andersen model include provider and organizational-level factors [30] and illustrate multidimensional domains that influence use of services.

Seeking or accepting a recommendation for care is a health behavior that emerges out of an often “non-conscious cost benefit analysis” [31]. It is only when we ask older adults about the reasons for their choices and about their personal experiences that their attitudes and beliefs become clear. To accept a recommendation or referral and participate in mental health treatment reflects a balance of predisposing factors, enabling factors and perceived need for care. Clinicians are generally aware of tangible barriers older adults face due to transportation, lack of mental health parity in insurance costs, and the impact of medical illnesses. But often these factors obscure attitudes toward depression and concerns about treatment that may be equal determinants. Attitudes and beliefs may exacerbate tangible barriers (e.g., transportation, cost), making treatment inaccessible. In addition, for older adults with depression, low energy and resignation resulting from depressive symptoms, cognitive deficits, and associated disabilities all compound psychosocial barriers to treatment engagement [32].

There are a number of alternative models to the Andersen model that explain individual-level health behavior change, each relevant to different aspects of the treatment engagement process. The Health Belief model [33,34] emphasizes individual perceptions including benefits and barriers. Social Learning Theory [35] emphasizes the importance of self-efficacy. Beliefs are primary according to the Theory of Reasoned Action [36], including normative beliefs such as social stigma. Other conceptual models take into account interpersonal interactions between individuals and health care providers. For example, Interdependence Theory posits that health behavior change most effectively takes place in the context of relationships characterized by trust, respect, and shared power and decision-making [37–39]. The Network Episode model frames care-seeking as a dynamic process where contacts with mental health and lay providers affect an individual’s engagement in care over time [40].

Empirical findings related to treatment engagement

Perceived illness severity, stigma, and treatment preferences

Our work with community-dwelling older adults from a variety of settings has documented a number of barriers and facilitators of care, including perceived depression severity, stigma, and preferences for specific types of treatment. Among clients of senior services, we found that half of elders diagnosed with depression do not perceive themselves as suffering from an emotional illness [5]. Moreover, research from other groups has documented an association between perceived illness severity and treatment adherence [41,42]. We have also documented a high degree of concern by aging service clients about the social costs of being stigmatized for seeking depression treatment. Even for those elders who do initiate care, perceived stigma is a barrier to both participation in treatment and antidepressant medication adherence [43]. Among adult and elderly primary care patients, we have found strength of treatment preferences for antidepressant medication or psychotherapy to be associated with treatment initiation and ongoing adherence [44]. We have documented a wide array of depression treatment preferences among elderly home healthcare patients, with roughly half preferring active treatments as their first choice (e.g., antidepressant medication or psychotherapy) and half preferring inactive or complementary approaches (e.g., religious activities, do nothing) [45]. Patients with current or prior mental health treatment, white or Hispanic patients, those with greater functional impairment, and those with less personal stigma were more likely to prefer an active treatment approach.

Influence of socio-cultural factors on treatment engagement

Race, ethnicity, and cultural factors may play a significant role in the treatment engagement process. For example, barriers to using mental health care may reflect cultural assumptions about need and mental health care [46]. Attributions of depression to difficult life circumstances versus medical causes influence help-seeking and reactions to treatment recommendations [47–50]. Concerns about stigma, fear of involuntary hospitalization and reluctance to divulge personal information are common among minority elders [51,52]. Religious and spiritual beliefs may contribute to this reluctance and to delays in help-seeking [53].

Based on resilience theory, resistance to seeking care among minority seniors may reflect effective coping mechanisms and adaptations to surviving poverty, racism and discrimination into later years that now have become obstacles to health care [54,55]. Preferences for self-reliance, use of home remedies, and care avoidance due to mistrust of health care professionals may be powerful remnants from earlier healthcare abuses [56,54,55]. In these cases, the predisposing factors that once served to protect the individual have now become barriers to care.

Integrated Model of the Treatment Engagement Process

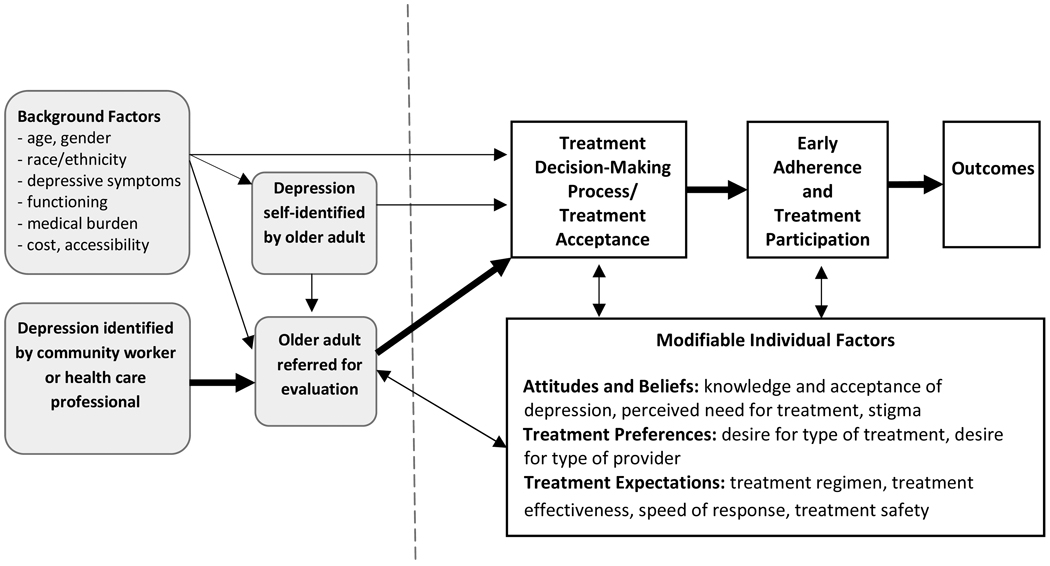

In conceptualizing the impact of both psychosocial and interactional factors on the treatment engagement process, we have integrated aspects of the Andersen, Health Belief, and Interdependence Models (Figure 1). Our model begins at the point where depression is identified. In some cases, older adults recognize the need for treatment and self-refer to health or mental health services. In other instances, a community worker or health care professional identifies depression and introduces the need for further evaluation or treatment. Referral for further evaluation to determine treatment need represents one opportunity for behavioral intervention, given low rates of follow through by older adults on such referrals (see Open Door study below). Interventions targeting the referral process are appropriate for settings in which mental health care is not available on site but must be pursued elsewhere.

Figure 1.

Treatment Engagement Process

Another opportunity for intervention is the treatment decision-making process between an individual and a health care professional (see Shared Decision-Making study below). This process involves some sort of interaction that can range from a simple treatment recommendation at the most basic end; to education about the effectiveness, side effects, and cost of a treatment approach (or approaches); to a truly mutual collaboration that results in a treatment decision that is tailored to the unique needs and background of the older adult. Interventions targeting treatment decision-making are appropriate for settings in which mental health care may or may not be available on site.

Yet another avenue for intervention in the treatment engagement process may focus on early adherence and participation in treatment. These types of interventions address an individual’s attitudes and beliefs about depression treatment after treatment recommendations have been given or treatment decisions have been made (see TIP study below).

Numerous a priori individual and environmental background factors (e.g., demographics, clinical status, medical and functional status, personality, cost, accessibility), health care professional factors, and modifiable individual factors affect how older adults respond to a referral for evaluation and how they participate in the treatment decision-making process and ongoing treatment. Interventions that address these areas may help older adults generate more positive and realistic attitudes, beliefs, and expectations about depression treatment, develop more informed treatment preferences, and participate more actively in their care.

Treatment engagement interventions

Many collaborative care interventions for depressed individuals attempt to encourage patient involvement in treatment decisions and subsequent treatment adherence. Very few targeted interventions, however, have been developed and tested regarding the treatment engagement process. The PRISM-E study [57], while not specifically focused on individual attitudes or beliefs, examined organizational changes to primary care in comparison to enhancing the referral process. Co-location of mental health specialists in primary care resulted in improved access to care for older adults, in comparison to “enhanced referral” to specialty services that addressed tangible barriers such as transportation and payment. In another study, a single session of psychoeducation to address stigma in Black adults referred for mental health treatment was found to reduce stigma among those with higher perceived treatment need or greater uncertainty about treatment [58]. Other studies have found shared decision-making interventions for depressed adults to increase their involvement and satisfaction with the treatment decision-making process [59–63].

In the following sections, we describe three personalized treatment engagement interventions that we have designed specifically for depressed community-dwelling older adults. Each intervention targets potential barriers at different junctures in the treatment engagement process, with the goal of improving treatment adherence and depression outcomes.

The Open Door intervention

The Open Door study is an NIMH-funded randomized controlled trial of a brief psychosocial intervention focused on the early part of our engagement model: the point at which depression is identified by a community worker who provides aging services. The intervention involves identification of both psychological and tangible barriers to care by a study clinician, who then collaboratively addresses these barriers with the depressed older adult. Its format is two 30-minute face-to-face sessions with one telephone follow-up. Using psychoeducation and problem-solving techniques combined with the inquiry style of motivational interviewing, the goal is to help the depressed older adult engage in a decision analysis about seeking care and to support use of mental health services.

Common barriers that need to be addressed with older depressed adults who receive aging services include a perception that depression is a natural part of aging, or that it is symptomatic of comorbid medical conditions. Older adults often do not readily identify these “symptoms” as abnormal. Instead, many depressed older persons struggle to get moving, take care of themselves and their families, and manage their day to day affairs (from their perspectives). They do not perceive themselves as suffering from a mental illness (our term). From their perspectives the difficulties they encounter are part of life, and therefore cannot be ameliorated by engaging in mental health care.

In a pilot study, the Open Door intervention was offered to all older adults who scored 10 or above on the PHQ-9 and participated in a home-delivered meal program in Westchester County, New York. Of 32 eligible participants over a 7-month period, we found that three older adults were already receiving treatment. The study clinician coached these individuals to discuss their continued distress with their existing clinician. Of the remaining 29, 20 (62%) accepted a mental health referral and scheduled a first appointment to be seen by a clinician in the community. Nine (38%) refused a referral. This successful referral rate was notably higher than a historical control rate of 22% (n=18/171 over a 7-month period). The current NIMH-funded study will allow us to conduct a fully powered randomized trial on the impact of this intervention, in comparison to a control condition where mental health referrals are offered through case management services, on attendance at mental health treatment and decrease in depressive symptoms.

Shared decision-making for elderly depressed primary care patients

We are currently evaluating a shared decision-making intervention in an NIMH-funded study among older depressed, low-income patients in an inner city New York hospital [22]. This brief intervention is also focused on an early stage of our engagement model: the point at which a primary care physician has identified depression and introduced the need for some kind of treatment. Developed from the patient-centered view of health care delivery [64] and in reaction to the traditional paternalistic approach in medicine [65], shared decision-making emphasizes a collaborative process. This involves an exchange of information on the pros and cons of different treatment options; exploration of patient expectations and preferences; and formulation of a mutually agreed-upon treatment decision [65]. Decision aid materials are commonly used as part of this process, and aim to clarify personal values and lead to more informed treatment preferences. These interventions attempt to counteract typical symptoms of helplessness, hopelessness, and lack of motivation by increasing patient involvement in their care. This challenge can be compounded in older adults who experience greater medical burden and cognitive impairment, and who have unique sets of psychological and tangible barriers to care.

Our shared decision-making intervention is delivered by a nurse within the primary care setting. The intervention consists of one 30–40 minute face-to-face meeting between the nurse and older depressed primary care patient, followed by 2 weekly 10–15 minute telephone follow-ups. The intervention is targeted to both English and Spanish-speaking patients, in whom barriers to treatment engagement may be even more pronounced. The nurse elicits the patient’s treatment experiences, values, preferences, and concerns regarding a variety of treatment approaches including antidepressant medication and psychotherapy. She then uses decision aid materials to educate the patient about each treatments’ effectiveness, speed of onset, side effects, and costs, and to clarify the patient’s values. We use a one-page form that presents treatment information in easy-to-understand language, with treatment options presented in column format so patients can compare their relevant characteristics. We also provide education handouts regarding late-life depression for patients and family members to review at home. Telephone follow-ups allow the nurse and patient to review treatment decisions and the patient’s ability to implement and adhere to them. The current study will evaluate the impact of this intervention, in comparison to Usual Care, on patient adherence to antidepressant medication or psychotherapy and on reduction in depressive symptoms.

Treatment Initiation Program in Primary Care (TIP-PC)

The Treatment Initiation Program (TIP-PC) is a brief intervention focused on a later stage in our engagement model: early adherence among older adults prescribed antidepressant medication by their primary care physicians. TIP-PC targets a number of psychological barriers that can interfere with antidepressant adherence. These include stigma, self-efficacy, resignation about antidepressant limitations, fears about antidepressants, and attribution of depressive symptoms to other causes which would make treatment unnecessary. We incorporate an understanding that while older adults may face many tangible barriers (e.g., transportation, medication copayments, and mobility), it is often their attitudes and beliefs that contribute to these barriers seeming insurmountable.

The TIP-PC intervention format is three 30-minute individual meetings with the patient during the first 6 weeks of pharmacotherapy, followed by two follow-up telephone calls at 8 and 10 weeks. The intervention involves 1. reviewing symptoms and assessing barriers to antidepressant recommendations; 2. assistance in defining personal goals regarding adherence; 3. providing psychoeducation; 4. collaborating to address barriers to adherence; 5. creating an adherence strategy; and 6. facilitating and empowering older adults to speak directly with their physician about treatment concerns.

We have conducted a randomized controlled pilot study of TIP-PC among 70 elderly primary care patients in New York city [23]. Subjects were assigned to receive either the TIP-PC intervention or Usual Care. Analyses indicated that TIP-PC participants had higher rates of antidepressant adherence than Usual Care participants at 6, 12, and 24 week follow up points. At 12 weeks the majority (82%) of TIP-PC participants were adherent to prescribed antidepressant medication at the 80% level or above, when compared with only 43% of Usual Care participants. Neither age, gender, nor baseline depression severity modified the impact of TIP-PC. TIP-PC participants also showed a greater decrease in depressive symptoms than Usual Care participants over the 24-week follow-up period. In collaboration with the University of Michigan (PI: Kales), we are currently conducting a larger-scale collaborative NIMH-funded study using a similar design.

Summary and future directions

We have described three personalized interventions aimed at identifying and addressing barriers to the treatment engagement of depressed older adults in community settings. Our conceptual model highlights the different junctures at which such interventions may be implemented. These range from the point at which a referral is provided for further evaluation, to the treatment decision-making process, to early treatment adherence following a specific treatment recommendation. Addressing barriers early in the process can maximize treatment engagement, while ongoing attention to new challenges and barriers can reinforce earlier intervention efforts. If these interventions are found to be useful, the next step will be to disseminate them more widely to other community settings.

Beyond the specific interventions described, there are a number of promising research agendas regarding treatment engagement. While much of our research is conducted among diverse low-income older adults, there is a need to address the needs of a variety of older adult populations where barriers to treatment engagement may be unique. For example, socio-demographic and cultural factors may impact the extent to which patients respond to and benefit from our interventions. In addition, we have investigated discrete interventions focused on very specific junctures of the engagement process. In certain service settings, combined aspects of these interventions may also prove fruitful. For example, addressing treatment barriers and engaging in shared decision-making are certainly compatible processes. These interventions may also be blended into other psychotherapeutic, pharmacologic, and collaborative care interventions to facilitate engagement. Key issues to investigate when combining such interventions are the feasibility of their implementation depending on service setting; their effectiveness relative to a single discrete intervention; and their cost. Lastly, as the evidence base builds for the effectiveness of these types of person-centered interventions in improving treatment engagement and clinical outcomes, efforts should turn to designing multi-faceted interventions that incorporate organizational issues. For example, adaptations of interventions to specific community agencies are necessary when attempting to maximize their uptake and sustainability [66]. Future research is needed to document factors that facilitate successful adoption and integration of such engagement interventions in community settings that serve older persons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant Nos. R01 MH084872; R01 MH087562; R01 MH079265; P30 MH085943 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Henderson AS, Jorm AF, MacKinnon A, et al. The prevalence of depressive disorders and the distribution of depressive symptoms in later life: a survey using Draft ICD-10 and DSM-III-R. Psychol Med. 1993;23:719–729. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and sociodemographic characteristics: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88:35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyness JM, Caine ED, King DA, et al. Psychiatric disorders in older primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:249–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulberg HC, Mulsant B, Schulz R, et al. Characteristics and course of major depression in older primary care patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;28:421–436. doi: 10.2190/G23R-NGGN-K1P1-MQ8N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Carpenter M, et al. Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among older adults receiving home delivered meals. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:1306–1311. doi: 10.1002/gps.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, et al. Major depression in elderly home health care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1367–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Williams JW, Jr, et al. Re-engineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2004;329:602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38219.481250.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. Bmj. 2006;332:259–263. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38683.710255.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee S, Shamash K, Macdonald AJ, et al. Randomised controlled trial of effect of intervention by psychogeriatric team on depression in frail elderly people at home. Bmj. 1996;313:1058–1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7064.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciechanowski P, Wagner E, Schmaling K, et al. Community-integrated home-based depression treatment in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;291:1569–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gellis ZD, McGinty J, Horowitz A, et al. Problem-solving therapy for late-life depression in home care: a randomized field trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:968–978. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180cc2bd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabins PV, Black BS, Roca R, et al. Effectiveness of a nurse-based outreach program for identifying and treating psychiatric illness in the elderly. Jama. 2000;283:2802–2809. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.21.2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogler LH, Cortes DE. Help-seeking pathways: a unifying concept in mental health care. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:554–561. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mechanic D. Sociocultural and social-psychological factors affecting personal responses to psychological disorder. J Health Soc Behav. 1975;16:393–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mechanic D. Removing barriers to care among persons with psychiatric symptoms. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:137–147. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briones DF, Heller PL, Chalfant HP, et al. Socioeconomic status, ethnicity, psychological distress, and readiness to utilize a mental health facility. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1333–1340. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.10.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg D, Huxley P. The pathway to psychiatric care. New York: Tavistock; 1980. Mental illness in the community. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenley JR, Mechanic D, Cleary PD. Seeking help for psychologic problems. A replication and extension. Med Care. 1987;25:1113–1128. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198712000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raue PJ, Schulberg HC, Lewis-Fernandez R, et al. Shared decision-making in the primary care treatment of late-life major depression: a needed new intervention? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1101–1111. doi: 10.1002/gps.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Kales HC. Improving antidepressant adherence and depression outcomes in primary care: the Treatment Initiation and Participation (TIP) Program. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:554–562. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cdeb7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartels SJ, Drake RE. Evidence-based geriatric psychiatry: an overview. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;28:763–784. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, et al. Administrative update: utilization of services. I. Comparing use of public and private mental health services: the enduring barriers of race and age. Community Ment Health J. 1998;34:133–144. doi: 10.1023/a:1018736917761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sirey JA, Meyers BS, Bruce ML, et al. Predictors of antidepressant prescription and early use among depressed outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:690–696. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institute of Mental Health. The National Institute of Mental Health Strategic Plan. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 2008. (NIH Publication 08-6368) http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/index.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen R. Research Series No. 25. Chicago: Center for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago; 1968. Behavioral model of families' use of health services. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersen RM. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med Care. 2008;46:647–653. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817a835d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glanz K, Rimer B, Lewis F, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice. 3rd Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiosses DN, Alexopoulos GS. IADL functions, cognitive deficits, and severity of depression: a preliminary study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:244–249. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker M, editor. The Health Belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974:2. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ajzen I, Fisbein M. Understanding attitudes and social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelley H, Thibaut J. Interpersonal relation: a theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis M, DeVeliis B, Sleath B. Social influence and interpersonal communication in health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Lewis F, editors. Health behavior and health education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 240–264. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rusbult C, Van Lange P. Interdependence processes. In: Higgins E, Kruglanski A, editors. Social psychology: handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 564–695. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pescosolido BA, Boyer CA, Lubell KM. The social dynamics of responding to mental health problems. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1998. pp. 441–460. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aikens JE, Nease DE, Jr, Nau DP, et al. Adherence to maintenance-phase antidepressant medication as a function of patient beliefs about medication. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:23–30. doi: 10.1370/afm.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DiMatteo MR, Haskard KB, Williams SL. Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2007;45:521–528. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318032937e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raue PJ, Schulberg HC, Heo M, et al. Patients' depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: a randomized primary care study. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:337–343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raue PJ, Weinberger MI, Sirey JA, et al. Depression treatment preferences in home healthcare. Psychiatr Serv. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.5.532. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al. Mental health care for Latinos: inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino Whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alverson HS, Drake RE, Carpenter-Song EA, et al. Ethnocultural variations in mental illness discourse: some implications for building therapeutic alliances. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1541–1546. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cabassa LJ, Hansen MC, Palinkas LA, et al. Azucar y nervios: explanatory models and treatment experiences of Hispanics with diabetes and depression. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:2413–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guarnaccia PJ, Lewis-Fernandez R, Marano MR. Toward a Puerto Rican popular nosology: nervios and ataque de nervios. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003;27:339–366. doi: 10.1023/a:1025303315932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis-Fernandez R, Das AK, Alfonso C, et al. Depression in US Hispanics: diagnostic and management considerations in family practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:282–296. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alvidrez J, Arean PA, Stewart AL. Psychoeducation to increase psychotherapy entry for older African Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:554–561. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.7.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. Jama. 1999;282:583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conrad MM, Pacquiao DF. Manifestation, attribution, and coping with depression among Asian Indians from the perspectives of health care practitioners. J Transcult Nurs. 2005;16:32–40. doi: 10.1177/1043659604271239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franklin A, Oscar S, Guishard M, et al. Factors contributing to colon cancer beliefs and screening practices for African Americans. Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Annual Meeting; Washington, D.C. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franklin A, Oscar S, Guishard M, et al. Resilience theory in studying African Americans beliefs and practices toward colon cancer screening. Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Annual Meeting; Washington, D.C. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Figaro MK, Russo PW, Allegrante JP. Preferences for arthritis care among urban African Americans: " don't want to be cut". Health Psychol. 2004;23:324–329. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1455–1462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, Rao SM, et al. Psychoeducation to address stigma in black adults referred for mental health treatment: a randomized pilot study. Community Ment Health J. 2009;45:127–136. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams JR, Drake RE. Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Community Ment Health J. 2006;42:87–105. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, et al. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schauer C, Everett A, del Vecchio P, et al. Promoting the value and practice of shared decision-making in mental health care. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2007;31:54–61. doi: 10.2975/31.1.2007.54.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wills C, Franklin M, Holmes-Rovner M. Feasiblity and outcomes testing of a patient-centered depression support intervention for depression in people with diabetes. Paper presented at the 4th International Shared Decision Making Conference; Freiburg, Germany. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wills CE, Holmes-Rovner M. Integrating decision making and mental health interventions research: research directions. Clin Psychol (New York) 2006;13:9–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levenstein JH, McCracken EC, McWhinney IR, et al. The patient-centered clinical method. 1. A model for the doctor-patient interaction in family medicine. Fam Pract. 1986;3:24–30. doi: 10.1093/fampra/3.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML. A model for intervention research in late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:1325–1334. doi: 10.1002/gps.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]