Abstract

Autism is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder of unknown aetiology that affects 1 in 100–150 individuals. Diagnosis is based on three categories of behavioural criteria: abnormal social interactions, communication deficits and repetitive behaviours. Strong evidence for a genetic basis has prompted the development of mouse models with targeted mutations in candidate genes for autism. As the diagnostic criteria for autism are behavioural, phenotyping these mouse models requires behavioural assays with high relevance to each category of the diagnostic symptoms. Behavioural neuroscientists are generating a comprehensive set of assays for social interaction, communication and repetitive behaviours to test hypotheses about the causes of austism. Robust phenotypes in mouse models hold great promise as translational tools for discovering effective treatments for components of autism spectrum disorders.

Autism is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder with extraordinarily high heritability. Concordance between monozygotic twins reaches 90% for autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), as compared with less than 10% for dizygotic twins and siblings, and approximately 0.6–1.0% occurrence in the general population, along with a 4:1 male:female ratio1–5. The number of reported cases of autism has risen rapidly over the past decade, largely due to better diagnostic instruments and public awareness, although environmental causes and gene–environment interactions are also under investigation6,7. Considerable efforts are now focused on understanding the genetic causes of autism (see `Further Information') and using the genetic findings to select rational targets for effective treatments. Large international consortia are conducting linkage analyses to identify chromosomal loci and association and whole-genome scans to discover candidate genes. Rare variants in candidate genes have been reported, both de novo and familial, as well as copy number variants and epigenetic factors8–10. Strong evidence indicates that functionally interrelated mechanisms underlie the disorder. Synaptic development genes implicated in autism include neurexins, neuroligins, shanks, reelin, integrins, cadherins and contactins. However, each candidate gene mutation occurs in only a few individuals with autism1,3,9–17. Signalling, transcription, methylation and neurotrophic genes implicated in ASDs include phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN), MET, engrailed 2 (EN2), methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2), fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1), tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2), calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L type, alpha 1C (CACNA1C), ubiquitin ligase E3A (UBE3A), Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion 2 (CADPS2) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)1,10,18–25. Neurotransmission genes, including the serotonin transporter, oxytocin and vasopressin receptors and GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) receptor subunit β3, have been repeatedly associated with autism or highly implicated in social and affiliative behaviours impaired in autism1,26,27. Copy number variants include chromosomal duplications at 15q11–13 and 17p11.2 and deletions at 16p11.2 and 22q13.3 (Refs 8,10,15,28–32).

One compelling approach to test hypotheses about the many candidate genes for autism is to generate analogous mutations in the mouse genome and evaluate the mutant line for phenotypes analogous to the symptoms of autism33–35. Effective animal models should incorporate face validity (strong analogies to the endophenotypes of the human syndrome), construct validity (the same biological dysfunction that causes the human disease, such as a gene mutation or anatomical abnormality) and predictive validity (analogous response to treatments that prevent or reverse symptoms in the human disease)36,37. Mouse models have been generated with chromosomal deletions and with knockout and humanized knock-in mutations in many of the candidate genes detected in subsets of individuals with ASDs1,25,29,38–68. Mouse models with construct validity are being used to evaluate hypotheses about both genetic and environmental causes of autism, including single gene polymorphisms, copy number variants, epigenetic modifications, environmental toxins, prenatal infections, immune dysfunctions and mitochondrial abnormalities22,63,69–77. Hypotheses about multiple risk genes and gene–environment interactions are tested in mouse models that incorporate construct validity for two or more hypothesized causes, using the same behavioural assays as read-outs. Naturally occurring phenotypic differences among inbred mouse strains have been successfully utilized to identify model systems with high face validity and cost efficiency78–91. Phenotypes with strong face validity provide ideal translational tools for evidence-based treatment discovery22,63,73–77,88,92. TABLE 1 presents examples of genetic mouse models displaying behavioural phenotypes that are relevant to the three diagnostic criteria for autism25,29,38–41,43–68,78–87,89–91.

Table 1.

Examples of autism-relevant behaviours in genetic mouse models of autism spectrum disorders

| Mouse model | Genetic characteristics | Behavioural phenotypes relevant to the symptoms of autism* |

|---|---|---|

| Nlgn4 | Null mutation in the murine orthologue of the human NLGN4 gene43 | |

| Nlgn3 | Homozygous mutation of humanized R451C mutation of the Nlgn3 gene44,45 | |

| Null mutation in the murine orthologue of the human NLGN3 gene41 | ||

| Neurexin 1α | Null mutation in the murine neurexin 1α generated by deleting the first exon of the gene46 | |

| Nlgn1 | Null mutation in the murine orthologue of the human NLGN1 gene47 | |

| Pten | Conditional null mutation, inactivated in neurons of the cortex and hippocampus, mouse orthologue of the human PTEN gene68 | |

| Pten haploinsufficent mutant line in which exon 5, and thus the core catalytic phosphatase domain, is deleted48 |

|

|

| En2 | Null mutation in the murine orthologue of the human EN2 gene49,50 | |

| 15q11–13 | Duplication in the genomic region on the mouse chromosome 7 homologous to the human genomic region 15q11–13 (REF. 29) | |

| 17p11.2 | Duplication in the genomic region of murine chromosome 11 homologous to the human genomic region 17p11.2 (REF. 51) | |

| Gabrb3 ‡ | Null mutation in the murine orthologue of the human GABRB3 gene52 | |

| Slc6a4 | Null mutation in the murine orthologue of the human serotonin transporter (SLC6A4) gene50 | |

| Haploinsufficient mutant line of the human serotonin transporter SLC6A gene48 |

|

|

| Oxt | Null mutation in the murine Oxt gene generated by either a deletion in the first exon40,53,54 or by deletions in the last two exons40 | |

| Avpr1b | Null mutation of the murine vasopressin receptor 1b Avpr1b gene55,56 | |

| Mecp2 | Heterozygous mutation in methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (REFS 39,57,58,59) | |

| Fmr1 | Null mutant mouse with a targeted mutation in the Fmr1 gene in three genetic backgrounds: C57BL/6J38,50,60,61; hybrid of FVB/NJ × C57BL/6J62; and FVB/N-129/OlaHsd50 | |

| Tsc | Heterozygous mutation that replaces the second exon in the Tsc2 gene63 |

|

| Heterozygous mutation generated by replacing exons 6–8 in the Tsc1 gene65 | ||

| Foxp2 | Homozygous and heterozygous mutations in the mouse homologue of the FOXP2 gene64 Knock-in mice for the mouse homologue of FOXP2 (REF. 67) |

|

| Fgf17 | Null mutation in the murine Fgf17 gene generated by deletion of the sites that encode the signal peptide66 | |

| Cadps2 | Null mutation in murine orthologue of the Cadps2 gene25 |

|

| BTBR | BTBR T + tf/J (BTBR strain) is a genetically homogenous inbred strain that displays behavioural traits with face validity to all three diagnostic symptoms of autism | |

| BALB | BALB/cJ and BALB/cByJ are genetically homogenous inbred strains that display relatively low social behaviour in various settings, reduced ultrasonic vocalizations and reduced empathy-like behaviour | |

| C58/J | C58/J is a genetically homogenous inbred strain that displays low sociability, primarily in males, and high levels of two distinct repetitive behaviours that emerge early in development |

Behavioural tests are described in the main text.

Phenotypes of survivors.

Avpr1b, arginine vasopressin receptor 1b; Cadps2, Ca2+-dependent activator protein for secretion 2; En2, engrailed 2; Fgf17, fibroblast growth factor 17; Fmr1, fragile × mental retardation syndrome 1; Foxp2, forkhead box protein 2; Gabrb3, gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor, subunit beta 3; Mecp2, methyl-CpG-binding protein 2; Nlgn, neuroligin; Oxt, oxytocin; Pten, phosphatase and tensin homologue; Slc6a4, solute carrier 6 member 4; Tsc, tuberous sclerosis.

How do we model the symptoms of autism in mice?

Designing mouse behavioural tasks that are relevant to human mental disorders presents a daunting challenge. Symptoms may be uniquely human and are often inherently variable. Autism diagnosis is currently based on purely behavioural criteria, as no consistent biological markers have yet been identified2,93–98. Until now, DSM-IV99, the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association, and ICD-10100, the diagnostic manual of the World Health Organization, have required the presence of core elements in three specific categories: abnormal reciprocal social interactions, which include reduced interest in peers and difficulty maintaining social interaction, and failure to use eye gaze and facial expressions to communicate efficiently; impaired communication, which generally presents as language delays, deficits in language comprehension and response to voices, stereotyped or literal use of words and phrases, poor pragmatics (knowing how and when to use language) and lack of prosody, resulting in monotone or exaggerated speech patterns; and repetitive behaviours, which include motor stereotypies, repetitive use of objects, compulsions and rituals, insistence on sameness, upset to change and unusual or very narrow restricted interests. Proposed DSM-V revisions may merge the first two criteria into a more general social-communication factor that includes lack of social reciprocity and deficits in nonverbal and verbal communication, beginning in early childhood.

Based on extensive advice generously contributed by autism clinical experts, behavioural neuroscientists are engaged in generating new mouse behavioural tasks and in refining existing paradigms from the behavioural neuroscience literature that maximize face validity to each of the core symptoms. Here, we review the tests that have proven most useful, along with the essential control measures, for the triad of diagnostic features of autism. Neuroanatomical, biochemical, electrophysiological and genetic similarities between mice and humans support the use of mouse models to further our understanding of biological mechanisms underlying the behavioural manifestations of autism. Similar responses to pharmacological treatments in mice and humans encourage the use of well-validated mouse models in the discovery of effective therapeutics for ASD.

Assays for social interaction abnormalities in mice

Mus musculus is a social species that engages in high levels of reciprocal social interactions, communal nesting, sexual and parenting behaviours, territorial scent marking and aggressive behaviours101–105. A variety of social assays have been described in the behavioural neuroscience literature34,37. The examples described below were designed to maximize relevance to the types of social deficits that are specific to autism.

Reciprocal social interactions

Fine-grained measures of interactions between pairs or groups of juvenile or adult mice placed together in standard cages or specialized arenas provide the most detailed insights into reciprocal social interactions. Parameters routinely evaluated include nose-to-nose sniffing, nose-to-anogenital sniffing, following, pushing past each other with physical contact, crawling over and under each other with physical contact, chasing, mounting and wrestling78,81,90,103,106. Parameters are scored from videotapes by investigators, using data sheets or event-recording software. Automated videotracking systems have also been used to score social interactions between two mice41,107. The experimental design, including the specific parameters scored, session duration, time of day, prior social isolation, environmental enrichment and pair composition by age, sex and strain, is optimized to meet the goals of the experiment. Repeated testing of the same mice is usually possible; this allows researchers to evaluate trajectories across the neurodevelopmental stages of pup, juvenile, young adult and older adult. FIG. 1 and Supplementary information S1 (movie) illustrate reciprocal social interactions in mice.

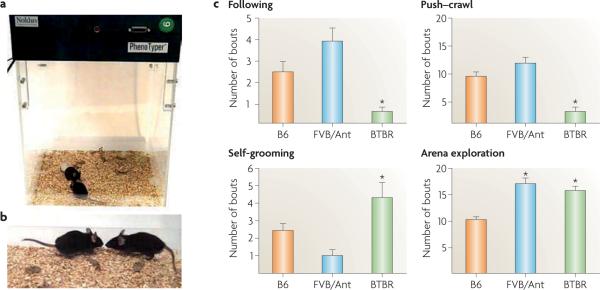

Figure 1. Reciprocal social interactions.

a | The Noldus PhenoTyper 3000 apparatus containing two unfamiliar juvenile male C57BL/6J (B6) mice engaged in social interaction. b | Nose-to-nose sniffing between two unfamiliar juvenile male B6 mice. A video camera records the 10-minute session. A human observer, uninformed of the treatment condition, scores parameters of social interaction and non-social exploration of the arena using Noldus Observer event-recording software. Social parameters scored include following (one mouse walks closely behind the other, keeping pace) and push–crawl (physical contact includes pushing the snout or head underneath the partner's body, squeezing between the partner and the arena wall or floor, and crawling over or under the partner's body). Non-social parameters include self-grooming (the mouse grooms its face and body regions in a normal sequential pattern) and arena exploration (walking around the arena, sniffing the walls, floor and bedding, and digging in the bedding). Detailed scoring methods are described in Refs 44,81,90,91,111. c | Representative data for reciprocal social interactions in pairs of juvenile males of two high-sociability inbred strains of mice, B6 and FVB/Ant, and a low-sociability strain, BTBR T+tf/J (BTBR). BTBR mice exhibited lower levels of following and push–crawl and higher levels of self-grooming and arena exploration than B6 mice, as previously reported81,90,111. FVB/Ant exhibited high levels of following and push–crawl similar to B6, low self-grooming similar to B6, and arena exploration similar to BTBR. These data further support the interpretation of a specific social deficit and unusual repetitive behaviour in BTBR mice. n = 12 B6 mice, 16 FVB/Ant mice and 12 BTBR mice. *p < 0.05 compared with B6 mice.

Social approach

Simpler, automated measures of direct social approach offer more standardized, higher-throughput assays, although fewer details of reciprocal interactions are captured. We developed an automated three-chambered social approach task, which scores time spent in a side chamber with a novel mouse versus time spent in a side chamber with a non-social novel object, an inverted wire pencil cup44,81,90,108,109. Sociability is defined as the subject mice spending more time in the chamber containing the novel target mouse than in the chamber containing the inanimate novel object. The wire cup serves as the novel object on one side and as the container control for novel object plus novel mouse on the other side. With the target novel mouse contained, the social approach is initiated by the subject mouse only. The widely spaced wire bars of the container permit olfactory, visual, auditory and some tactile contact while preventing aggressive and sexual interactions, thus ensuring a pure measure of simple interest in approaching and remaining in physical proximity to another.

Our photocell-equipped apparatus uses infrared beams embedded in the partitions between compartments40,44,81,83,90,91,109–111. As the subject mouse moves between the three compartments, beam-breaks are recorded by the software and converted to time the mouse spends in each compartment and number of entries into each compartment. To provide a corroborative and more specific measure of social investigation during the test session, an observer scores time spent sniffing the novel mouse and time spent sniffing the novel object from session videotapes or in real time. The number of entries between compartments provides an independent measure of general exploratory locomotion. Mice can be tested more than once in this task — for example, at different ages to follow developmental trajectories. Videotracking software systems have been successfully used with the three-chambered apparatus, as well as observer scoring from videotapes43,48,77,107. FIG. 2 and Supplementary information S2 (movie) illustrate the automated social approach test in mice.

Figure 2. Automated three-chambered social approach.

a | The test apparatus, a rectangular, three-chambered box made of clear polycarbonate44,81,82,83,90,91,109,111. Retractable doorways built into the two dividing walls control access to the side chambers. Entries into each chamber are automatically detected by photocells embedded in the doorways. The number of entries and time spent in each chamber are tallied by the software. The test session begins with a 10-minute habituation session in the centre chamber only, followed by a 10-minute habituation session with access to all 3 empty chambers. If an innate side preference for either the right or left chamber is detected during the habituation session, the testing environment is reorganized to equalize light levels, nearby objects, and so on. The subject is then briefly confined to the centre chamber while a novel object (an inverted stainless steel wire pencil cup) is placed in one of the side chambers. A novel mouse, previously habituated to the enclosure, is placed in an identical wire cup located in the other side chamber. A weighted plastic cup is placed on the top of each inverted wire cup to prevent the subject from climbing on top. The side chambers containing the novel object and the novel mouse are alternated between left and right across subjects. After the novel object and the novel mouse are positioned, the two side doors are simultaneously lifted and the subject is allowed access to all three chambers for 10 minutes. In addition to the automatically tallied time spent in each chamber and entries into each chamber, an observer with stopwatches scores the time spent sniffing the novel object and the novel mouse, in real time or from videotapes. The investigator scoring time spent sniffing is blind to the identity of the subject mice. b | Adult male C57BL/6J (B6) and FVB/Ant mice displayed sociability, defined as spending more time in the chamber containing the novel mouse than in the chamber containing the novel object, and more time sniffing the novel mouse than sniffing the novel object. Adult male BTBR T+tf/J (BTBR) mice did not display sociability, spending similar amounts of time in the chamber containing the novel mouse and in the chamber containing the novel object, and similar amounts of time sniffing the novel mouse and sniffing the novel object, as previously reported in Refs 81,83,90,91,111. n = 12 B6 mice, 16 FVB/Ant mice and 12 BTBR mice. *p < 0.01 for the comparison between novel mouse and novel object.

Partition test

Another simple test of sociability uses a standard cage divided in half by a perforated partition made of clear plastic61,112 or wire104,105. The subject mouse is able to see, hear and smell the target mouse through the holes in the plastic or wire divider, but physical interactions are blocked. Time spent at the partition represents the amount of interest in the social partner. Different social partners can be sequentially placed in one compartment to evaluate social preference and social memory in the subject mouse.

Social preference tests

Partner preference tests are used to evaluate components of social affiliation, social recognition and social memory. The choice between partners is measured by the amount of time spent by the subject mouse with each partner. Preference for social novelty is defined as the subject mouse spending more time in a chamber or in physical contact with a novel mouse than with a familiar mouse. Partners with different characteristics — for example, pair bonded mates, or familiar versus unfamiliar conspecifics — provide measures of social recognition. Partners can be present simultaneously44,81,82 or sequentially with time delays between presentations, to evaluate recognition memory113–116. Equipment used for social preference tasks include the three-chambered apparatus shown in FIG. 2, the partition test apparatus in which the subject mouse initiates more approaches and spends more time close to the partition adjacent to a novel mouse than to the partition adjacent to a familiar mouse56,84,87, a Y-maze113 and freely moving subject mice spending time with tethered target mice in three cages connected by tunnels116,117. Behavioural parameters during test sessions are scored from videotapes by investigators who are blind to the genotype or treatment condition, by software from photocell-equipped systems or by software from videotracking systems.

Social transmission of food preference

Interaction with a cagemate who has eaten a novel flavoured food will confer familiarity with the flavour, resulting in the subject mouse eating more of the now-familiar food than of a completely new food118–121. Familiarity is acquired when the observer mouse sniffs the breath, face and whiskers of the demonstrator mouse. Because face sniffing and close physical contact appear to contribute to the communication of flavour information, this task measures the tendency of the observer mice to obtain meaningful information through social interactions with the demonstrator.

Assays for communication deficits in mice

How mice communicate is not yet well understood. Olfactory cues are of primary importance101,122. Vocalizations in the ultrasonic and sonic ranges, visual cues, gustatory and tactile modalities may also contribute to communication of information and to social bonding123–128. Several behavioural tasks are in routine use to evaluate the olfactory and auditory cues emitted by mice and the responses to these cues by other mice.

Urinary pheromones

Mice deposit urinary steroidal pheromones that function as territorial scent marks and display high levels of interest in urinary scents from other mice. This is reflected in their tendency to explore the anogenital area of a novel mouse, investigate urinary scent marks in a cage, sniff a cotton swab soaked in urine and choose volatile urinary odours delivered by an olfactometer in an operant chamber104,105,129,130. The number of scent marks and countermarkings in close proximity to urinary olfactory cues may measure social motivation and/or olfactory communication89. Quantification methods include observer scoring of the number and duration of sniffing bouts from session videos and olfactory discrimination in operant tasks.

Olfactory habituation/dishabituation to social odours

Mice tend to sniff a novel odour and then quickly habituate to its novelty40,120,131–134. Repeated presentation of a sequence of cotton swabs containing the same odour will result in the mouse spending less and less time sniffing the swab with each presentation (habituation), as measured by an investigator with a stopwatch. Subsequent introduction of a cotton swab saturated with a new odour will reinstate a high level of sniffing (dishabituation). The social odours on the cotton swabs are obtained from urine collected from another mouse or from swipes across the bottom of a cage of novel mice40,132. These social odours elicit considerably higher levels of sniffing than non-social odours, such as almond extract or banana flavouring132,134. The shapes of the habituation and dishabituation curves document the ability of mice to discriminate same and different non-social and social odours. The height of the peaks of the curves provide a measure of interest in the social and nonsocial odours. FIG. 3 and Supplementary information S3 (movie) illustrate olfactory habituation and dishabituation.

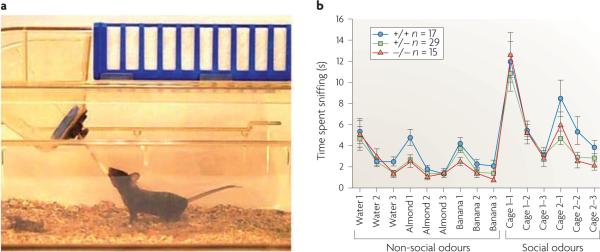

Figure 3. olfactory habituation/dishabituation.

a | The testing environment, an empty, clean mouse cage containing a thin layer of clean bedding and a hole for inserting a cotton-tipped swab40,120,131,132,134. b | Representative data from a line of oxytocin (Oxt, also known as OT)-knockout mice, comparing null mutants, heterozygotes and wild-type littermate controls. The first presentation of a water-saturated cotton swab elicited moderate sniffing that decreased across the second and third presentations of water swabs (habituation). The next presentations of three swabs saturated with almond extract (1:100 dilution) elicited significantly more sniffing (dishabituation), which decreased across the second and third presentations of the almond odour (habituation). The next presentations of three swabs saturated with imitation banana flavouring (1:100 dilution) elicited more sniffing (dishabituation) that decreased across the second and third banana presentations (habituation). The next presentations of three swabs swiped across the bottom of a cage containing soiled bedding from mice which had no previous contact with the subject (cage 1) elicited high levels of sniffing (dishabituation), which decreased across the second and third presentations of swipes from social cage 1 (habituation). The next presentations of three swabs swiped across the bottom of a different cage containing soiled bedding from mice that had no previous contact with the subject (cage 2) elicited high levels of sniffing (dishabituation), which decreased across the second and third presentations of swipes from social cage 2 (habituation). The shapes of the habituation and dishabituation curves confirm that the mice have the sensory abilities to detect and discriminate non-social and social odours. The heights of the peaks indicate interest in non-social and social odours. Time spent sniffing the social odours is generally higher than the number of sniffs of non-social odours. n = 7 male and 10 female Oxt+/+ mice, 14 male and 15 female Oxt+/− mice, 6 male and 9 female Oxt−/− mice. Part b is reproduced, with permission, from Ref. 40 © (2007) Elsevier.

Ultrasonic vocalizations

Complex vocalizations in the ultrasonic range are emitted by mice in social situations, including pups separated from the dam and nest, juvenile interactions, resident females in a resident–intruder task and males responding to female urinary pheromones56,84,87,123–128. Sensitive ultrasonic microphones, headphones and advanced software for detailed analyses of sonograms have revealed discrete categories of calls in mice56,84,87,124,126,128. Supplementary information S4 (audio) provides examples of mouse vocalizations in a social setting.

However, the intentional communicative nature of mouse vocalizations remains to be determined. Further research will be needed to understand which social situations elicit calls and how consistent those calls are during each specific social situation. Developing assays that are sensitive enough to detect subtleties of abnormal vocalizations in mice will be a challenge. Communication deficits in autism include developmental delays in the comprehension and use of expressive language, failure to respond to speech during early ages, the absence of rhythm and melodic prosody, literal use and interpretation of language, and the tendency to speak in monologues instead of interactively2,93,97,98. Although there is not a consistent vocalization endophenotype for autism during the first 2 years of life in humans (which would correspond to the pup stage in mice), ongoing studies are evaluating the relevance of juvenile and adult vocalizations in mouse models to the specific types of communication abnormalities in autism29,84,89,135.

Assays for repetitive behaviours

Stereotyped behaviours

Mice exhibit spontaneous motor stereotypies, including circling, jumping, backflips and self-grooming86,136–138. Scoring of stereotypies is conducted most reliably by an investigator observing video taped sessions or in real time. The observer records each bout of the stereotyped behaviour during a defined sampling period, using a scoresheet or an event recorder.

Repetitive behaviours

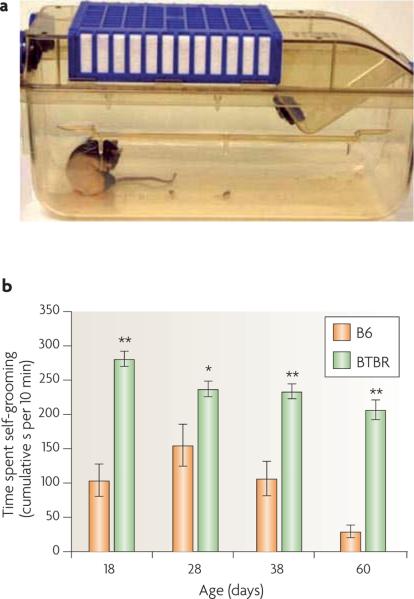

Sequences of behaviours may appear as normal patterns but persist for unusually long periods of time. BTBR T+tf/j mice (referred to here as BTBR) engage in extremely long episodes of repetitive self-grooming. BTBR mice may self-groom for up to 2 minutes, whereas bouts of self-grooming in standard control strains such as C57BL/6j(86) are much shorter, generally lasting between 5 and 10 seconds81,90,91,111. Repetitive behaviours are generally scored — from videotapes or in real time — by an observer with a stopwatch. Marble burying, a repetitive digging behaviour, is scored by counting the remaining unburied marbles139. FIG. 4 and Supplementary information S5 (movie) illustrate repetitive self-grooming in BTBR T+tf/j mice.

Figure 4. Repetitive self-grooming.

a | The testing arena, a clean, empty mouse cage. Each mouse was given a 10-minute habituation period in the empty cage, then scored for 10 minutes for cumulative time spent grooming all body regions81,90,111. b | Representative data in juvenile and adult male C57BL/6J (B6) mice and BTBR T+tf/J (BTBR) mice. High levels of repetitive self-directed grooming were evident in 18-, 28-, 38- and 60-day-old male BTBR mice compared with age-matched male B6 mice. n = 10 B6 mice and 10 BTBR mice. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. Part b is reproduced, with permission, from Ref. 81 © (2008) Blackwell Publishing.

Insistence on sameness

Perseverative behaviours are relatively common in mice. Reversal learning tasks measure the flexibility of the mouse to switch from an established habit to a new habit. A spatial habit is first established, for example, reinforcing entries into the left arm of a T-maze or by locating the hidden escape platform in one quadrant of a Morris water maze. The re inforcer is then moved to a new location − for example, the food reward is moved to the right arm of the T-maze or the hidden platform is moved to a different quadrant of the water maze pool44,82,140–142. A mouse model of autism is predicted to perform well on the initial acquisition but to fail on reversal owing to either increased perseveration or specific impairments in reversal learning. It may also be possible to model `upset to change' in mice. Olfactory disruptors introduced during a selective attention operant task produced a generalized disruption in performance143, illustrating an interesting response that could reflect an upset to a change.

Restricted interests

Methods to measure restricted interests in rodents are under development. One approach capitalizes on the tendency of mice to explore all aspects of a novel environment, including exploratory locomotion in a novel open field, sniffing of novel objects and nose poking into holes in the wall or floor144. Perseverative exploration of only one of the available objects or holes, rather than the normal strategy of exploring all novel objects or holes, may be analogous to restricted interests in human subjects with autism.

Assays to be developed

Designing mouse behavioural assays with high relevance to the diagnostic symptoms of autism presents a substantial challenge for capturing reasonable face validity. Several symptoms of autism, such as the literal use of language and difficulties in interpreting irony or sarcasm, are unlikely to be successfully modelled in mice.

`Theory of mind', the ability of one person to intuit what another person is feeling and thinking, may not be innate to the mouse repertoire. However, two recent reports support the possibility that mice display elements of empathy. Subject mice show greater responsiveness to a painful experience after observing cagemates who have experienced a painful stimulus80,145. Subtleties of language are also unlikely to be innate to mice. However, the complexity of mouse ultrasonic vocalization patterns may contain considerable communicative information135. Quantitative measures of the reward value of social interactions are not yet in place for mice or for autistic individuals. A starting point for measuring the reward value of social interactions in mice may be the literature on rat operant chambers that measure the number of lever presses for parental access to pups146, rat operant chambers that measure the number of lever presses for adult access to sexual partners147 and a mouse conditioned place preference task for social odours84,85.

Executive functions requiring the simultaneous integration of large amounts of complex social and non-social information may be localized in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region that is not well-developed in mice. Complex cognitive abilities are evaluated in mice using cognitive tests that depend on medial frontal cortex connections, such as the intradimensional and extra-dimensional attentional set-shift task148,149. Eye gaze is difficult to track in mice, as the pupil is hard to distinguish. However, elements of eye gaze, joint attention and attentional focus might be modelled in mice using sustained attention tasks, such as the five-choice serial reaction time test150 with auditory, visual or olfactory distracters151 Some features of autism, such as the 4:1 male:female ratio and regression of social communication after one year of age, have yet to be identified in a mouse model.

Associated symptoms

Associated symptoms, which occur in subsets of autistic individuals, include seizures, anxiety, mental retardation, hyperreactivity and hyporeactivity to sensory stimuli, sleep disruption and gastrointestinal distress152–154. Analogous pheno-types would be useful additions to a mouse model that displays robust social deficits. Standardized mouse assays are available to measure seizures (observer scoring, electroencephalography (EEG) recordings), anxiety-related behaviours (elevated plus-maze, light–dark exploration), cognitive abilities (spatial learning (Morris water maze), contextual and cued fear conditioned emotional learning, shock avoidance, object recognition and operant discrimination tasks, among others), hyper-sensitivity to sensory stimuli (acoustic startle, air puff startle, hot plate) and sleep (EEG recordings, circadian running wheels, home cage monitoring systems)37,155. Standard assays of mouse developmental milestones from birth through weaning are useful for identifying phenotypes that are relevant to associated symptoms of autism during early development37,44,56,87,98,156.

A fundamental issue resides in potential artefacts caused by mouse phenotypes which are relevant to an associated symptom of autism, but which confound the interpretation of a mouse phenotype with higher relevance to a specific core symptom of autism. For instance, mice with anxiety-like traits will engage in low exploratory activity, resulting in minimal entries into the side chambers in the three-chambered sociability task, thus rendering social approach data meaningless. Identifying phenotypes relevant to associated symptoms, versus artefacts that confound the interpretation of tests relevant to diagnostic symptoms, poses an internal paradox to be parsed on a case-by-case basis.

Methodological considerations

Control parameters

Severe physical disabilities will cause false positives in many of the behavioural tasks described above34–37,157–159. For example, olfactory deficits will inhibit performance on social approach, social recognition, olfactory discrimination and scent marking tests. Motor dysfunctions will prevent a mouse from active exploration of test environments that require locomotion, including social chambers, T-mazes and holeboards. To rule out artefacts, each new line of mutant mice has to be evaluated on a series of measures of general health, body weight, neurological reflexes, home cage behaviours, open-field activity, rotarod performance, visual forepaw placing, acoustic startle and pain sensitivity36,37. Given the fundamental role of olfaction in mouse social behaviours, social and non-social olfactory abilities are routinely evaluated with multiple tests, including latency to locate buried food, olfactory habituation/dishabituation to non-social and social odours, and preference for social novelty44,132.

Sample sizes and statistical analyses

The number of mice per group (n) for behavioural experiments is considerably larger than the number of mice needed for most biological assays. Larger numbers of mice are usually necessary to compensate for the unavoidable variability in environmental factors that influence mouse behaviours, such as handling by animal caretakers, vivarium conditions, early parental care and home cage dominance hierarchies. n = 10–20 per genotype and per sex is often required to achieve sufficient statistical power when performing, for example, a Two-Way Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). When a significant ANOVA is detected, a posthoc test, such as Newman–Keuls, Tukey's, Sheffe or Bonferroni–Dunn, is used to compare group means for specific differences between genotypes and/or treatment effects. If breeding, housing or testing capacity is limited, small subgroups can be generated to accumulate the needed numbers, as long as each genotype is represented in each subgroup on each day of behavioural testing, and the data from wild-type littermate controls do not differ across subgroups.

Replicability

The strength of a phenotype increases when the initial findings are replicated in a second and third cohort of littermates of all genotypes. Phenotypic replications that are produced by different investigators in the same laboratory, by different investigators in different laboratories, from independent lines of mice with the same mutation generated by different laboratories using different DNA constructs, or by breeding into different genetic backgrounds, clearly strengthen the conclusiveness of phenotypes. Minor methological differences and the influence of environmental factors become trivial when findings are well replicated across these different contexts.

Translational applications

The entire set of behavioural tasks described above can usually be conducted in the same set of mice, as long as reasonable attention is paid to the sequence in which the tests are conducted. For example, the most stressful tasks should be performed at the end of the sequence, and with sufficient intervals between testing days159. Occasionally a task cannot be conducted owing to species issues, such as body size or activity levels, physical or procedural artefacts caused by background genes, unexpected consequences of the targeted gene mutation, or side effects of a treatment. Most of the behavioural assays can be successfully applied to normal and mutant lines of mice and rats, inbred strains of mice and rats, and some other rodent species.

The field is now poised to pursue a comprehensive characterization of behavioural traits that are relevant to the symptoms of autism in each of the candidate gene mutant lines of mice. Positive findings obtained from a mutant mouse model will reinforce interest in pursuing a gene in molecular and clinical studies. For example, a rationale for developing metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) antagonists as therapeutics has been provided by studies showing that a genetic reduction of mGluR5 reversed some of the symptoms in Fmr1 mouse models of fragile X syndrome, in addition to studies showing that an mGluR5 antagonist treatment reversed Fmr1 phenotypes and repetitive self-grooming in BTBR mice74,88,160–162 (TABLE 2). Neuroanatomical, electrophysiological, neurochemical and other phenotypic characterizations can be used to test emerging hypotheses about the biological mechanisms responsible for the brain dysfunctions underlying neurodevelopmental disorders11,12,43,48,63,75,77,138,140,163. Identical phenotyping strategies can be applied to investigate putative environmental causes for autism. Interesting behavioural abnormalities have emerged from rodent models of prenatal exposure to valproic acid164, prenatal influenza infection165, immune dysfunctions71 and exposure to neurotoxins70.

Table 2.

Examples of treatments that prevented or reversed phenotypes in mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders

| Treatment | Mouse model | Phenotypic improvement |

|---|---|---|

| mGluR antagonists, MPEP88,161,162, fenobam162 | Fmr1 −/− | |

| BTBR |

|

|

| mTOR inhibitors, rapamycin63,77,177,178, RAD001 (Ref. 177) | Pten | |

| Tsc1 null-neuron inactivated in neurons63,177 | ||

| Tsc1GFAP inactivated in glia178 | ||

| Tsc2+/− (Ref. 63) |

|

|

| Oxytocin114 | OXT −/− |

|

| BDNF75 | Fmr1 −/− |

|

| Ampakines, CX546 (Ref. 73) | Mecp2 −/− |

|

| mGluR genetic reduction74 | Fmr1 −/− | |

| FMR1 gene replacement60,61,76 | Fmr1 −/− | |

| PAK genetic reduction92 | Fmr1 −/− | |

| MECP2 gene replacement174,176 | Mecp2−/+ is an inducible heterozygous transgenic176 | |

| Mecp2/Stop is an Mecp2 mutant with Mecp2 conditional activation174 |

|

See TABLE 1 and main text for further details on mouse models. AMPA,α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; Fmr1, fragile × mental retardation syndrome 1; Mecp2, methyl-CpG-binding protein 2; mGluR, metabotropic glutamate receptor; MPEP, 2-methyl-6-phenylethynyl-pyridine hydrochloride; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PAK, p21-activated kinase; Pten, phosphatase and tensin homologue; Tsc, tuberous sclerosis.

Treatments for the symptoms of autism are being intensively sought163,166. Early behavioural interventions, such as applied behaviour analysis, pivotal response training, parent training, behaviour management and social skills training in groups (all of which are primarily provided through special educational programmes), are currently the only treatments that significantly improve the first and second core symptoms (unusual reciprocal social interactions and communication deficits)156,167. Medications can have significant effects on associated symptoms such as hyperactivity or mood, but have not been shown to directly affect the core features of autism. Behavioural interventions have ameliorated symptoms in several mouse models of neurodevelopmental improved locomotion and rotarod performance in Rett syndrome Mecp2 mutant mice and reduced hyperactivity in fragile X syndrome Fmr1 knockout mice168–171. social peer enrichment improved social interactions in low-sociability BTBR mice reared as juveniles with social B6 cagemates172. Preclinical successes have been reported for genetic rescues and pharmacological reversals of aberrant phenotypes in mouse models of ASD. Successful drug candidates include mGluR5 antagonists, rapamycin, BDNF and oxytocin63,73–77,88,92,114,160–162,173–178 (TABLE 2). As knowledge grows about the genetic and environmental factors that confer susceptibility for autism, mouse models with construct validity and phenotypes that are relevant to core symptoms will offer strong translational systems for discovering rational therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

M. L. Scattoni, Istituto Superiore di Sanitá, Rome, Italy, generously contributed the supplementary audio file giving examples of mouse vocalizations. We thank A. Katz, Laboratory of Behavioural Neuroscience, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Bethesda, Maryland, USA, for the outstanding editing of the supplementary movies. J.N.C. is supported by the NIMH Intramural Research Program MH02179. C.L. is supported by NIMH grants R01MH81873, 1RC1MH089721 and 1R01MH089390.

Glossary

- Nesting

Building nests in the home cage and sleeping together in a huddle in the home cage.

- Social memory

Time-delayed recognition of a familiar mouse.

- Social affiliation

social affiliation behaviours in mice include parent–pup interactions, male–female pair bonding, mating and aggression.

- Social recognition

social recognition is the ability to distinguish familiar from novel conspecifics. social recognition by a subject mouse is defined by reduced social approach or reduced time spent investigating a familiar partner and reinstatement of investigation when a novel partner is introduced.

- Y-maze

A three-armed runway in the shape of the letter Y, used to measure exploratory behaviours in rodents.

- Repetitive self-grooming

Unusually long duration of the normal pattern of grooming of the entire body.

- T-maze

A device used to examine spatial position habit. subject mice are trained on an appetitive task with a spatially contingent reinforcer. failure of the subject to switch from a previously learned location to a new location represents resistance to change in routine.

- Morris water maze

A device used to test spatial learning. subject mice navigate a pool of water and utilize distal spatial cues to locate a hidden escape platform. failure of the subject to switch from a previously learned location to a new location models resistance to change in routine.

- Attentional set-shift task

An attentional task that requires the subject to simultaneously discriminate in two dimensions to obtain food reinforcement. for example, the food may be buried in sand versus gravel, and contained in a round bowl versus a square box. This task is dependent on intact frontal cortex functions and may be analogous to executive function tasks in humans.

- Five-choice serial reaction time test

A rodent attentional task analogous to sustained attention tasks for humans. The mouse must monitor five spatial locations simultaneously and nose-poke when the light above one is illuminated to obtain the food reinforcer. Accuracy and speed of response measure attentional performance. Distractors may be added to evaluate attentional shift.

- Elevated plus-maze

A device used to examine the naturalistic conflict between the tendency of mice to explore a novel environment and the aversive properties of an open elevated runway. Mice generally prefer the two enclosed arms, but will explore the two open arms to some extent. The total number of entries into all arms serves as a control for general locomotion. for example, motor dysfunctions or sedative effects of a drug treatment will reduce total arm entries.

- Applied behaviour analysis

An empirically validated teaching strategy that consists of a systematic process of studying and modifying observable behaviour, using environmental manipulations and behavioural response tracking to improve relevant behaviours.

- Pivotal response training

An intervention using a structured environment that includes items and activities that the affected individual prefers, and that can be used to meet goals. each learning interaction consists of the therapist offering choices, the individual making a choice and the therapist requiring an appropriate response in order for the individual to gain access to the item or activity.

- Social peer enrichment

Rearing and housing mice with social cagemates.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Abrahams BS, Geschwind DH. Advances in autism genetics: on the threshold of a new neurobiology. Nature Rev. Genet. 2008;9:341–355. doi: 10.1038/nrg2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A comprehensive overview of the genes that are implicated in autism and the available mouse models that incorporate candidate gene mutations.

- 2.Happe F, Ronald A. The `fractionable autism triad': a review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2008;18:287–304. doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lintas C, Persico AM. Autistic phenotypes and genetic testing: state-of-the-art for the clinical geneticist. J. Med. Genet. 2009;46:1–8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.060871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kogan MD, et al. Prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among children in the US, 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1395–1403. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charman T, et al. Commentary: Effects of diagnostic thresholds and research vs service and administrative diagnosis on autism prevalence. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009;38:1234–1238. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp256. author reply in 38, 1243–1244 (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fombonne E. Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr. Res. 2009;65:591–598. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819e7203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertz-Picciotto I, Delwiche L. The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology. 2009;20:84–90. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181902d15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook EH, Jr, Scherer SW. Copy-number variations associated with neuropsychiatric conditions. Nature. 2008;455:919–923. doi: 10.1038/nature07458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, et al. Common genetic variants on 5p14.1 associate with autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2009;459:528–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bucan M, et al. Genome-wide analyses of exonic copy number variants in a family-based study point to novel autism susceptibility genes. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss LA, et al. Variation in ITGB3 is associated with whole-blood serotonin level and autism susceptibility. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;14:923–931. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455:903–911. doi: 10.1038/nature07456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buxbaum JD. Multiple rare variants in the etiology of autism spectrum disorders. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009;11:35–43. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/jdbuxbaum. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourgeron T. A synaptic trek to autism. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009;19:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glessner JT, et al. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009;459:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature07953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamain S, et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nature Genet. 2003;34:27–29. doi: 10.1038/ng1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geschwind DH. Autism: the ups and downs of neuroligin. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:904–905. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto K, et al. Reduced serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult male patients with autism. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;30:1529–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimura K, et al. Genetic analyses of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene in autism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;356:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levitt P, Campbell DB. The genetic and neurobiologic compass points toward common signaling dysfunctions in autism spectrum disorders. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:747–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI37934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile × syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelleher RJ, Bear MF. The autistic neuron: troubled translation? Cell. 2008;135:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benayed R, et al. Autism-associated haplotype affects the regulation of the homeobox gene, ENGRAILED 2. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:911–917. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benayed R, et al. Support for the homeobox transcription factor gene ENGRAILED 2 as an autism spectrum disorder susceptibility locus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;77:851–868. doi: 10.1086/497705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadakata T, et al. Autistic-like phenotypes in Cadps2-knockout mice and aberrant CADPS2 splicing in autistic patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:931–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI29031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad HC, Steiner JA, Sutcliffe JS, Blakely RD. Enhanced activity of human serotonin transporter variants associated with autism. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2009;364:163–173. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakrabarti B, et al. Genes related to sex steroids, neural growth, and social-emotional behavior are associated with autistic traits, empathy, and Asperger syndrome. Autism Res. 2009;2:157–177. doi: 10.1002/aur.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar RA, et al. Association and mutation analyses of 16p11.2 autism candidate genes. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakatani J, et al. Abnormal behavior in a chromosome-engineered mouse model for human 15q11–13 duplication seen in autism. Cell. 2009;137:1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelan MC. Deletion 22q13.3 syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2008;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potocki L, et al. Characterization of Potocki–Lupski syndrome (dup(17)(p11.2p11.2)) and delineation of a dosage-sensitive critical interval that can convey an autism phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:633–649. doi: 10.1086/512864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vorstman JA, et al. Identification of novel autism candidate regions through analysis of reported cytogenetic abnormalities associated with autism. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:18–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crawley JN. Designing mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autistic-like behaviors. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2004;10:248–258. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawley JN. Mouse behavioral assays relevant to the symptoms of autism. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:448–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crawley JN. Medicine. Testing hypotheses about autism. Science. 2007;318:56–57. doi: 10.1126/science.1149801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crawley JN. Behavioral phenotyping strategies for mutant mice. Neuron. 2008;57:809–818. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crawley JN. What's Wrong With My Mouse? Behavioral Phenotyping of Transgenic and Knockout Mice. Wiley; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2007. [Google Scholar]; A comprehensive overview of the theory and methodology for the most commonly used mouse behavioural assays, including illustrations of necessary control experiments for reliable mouse behavioural phenotyping.

- 38.Mineur YS, Huynh LX, Crusio WE. Social behavior deficits in the Fmr1 mutant mouse. Behav. Brain Res. 2006;168:172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moretti P, Bouwknecht JA, Teague R, Paylor R, Zoghbi HY. Abnormalities of social interactions and home-cage behavior in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:205–220. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crawley JN, et al. Social approach behaviors in oxytocin knockout mice: comparison of two independent lines tested in different laboratory environments. Neuropeptides. 2007;41:145–163. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radyushkin K, et al. Neuroligin-3-deficient mice: model of a monogenic heritable form of autism with an olfactory deficit. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:416–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang M, Scattoni M, Chadman K, Silverman J, Crawley JN. In: Autism Spectrum Disorders. Geschwind D, Dawson G, editors. Oxford Univ. Press; In the press. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jamain S, et al. Reduced social interaction and ultrasonic communication in a mouse model of monogenic heritable autism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1710–1715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711555105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chadman KK, et al. Minimal aberrant behavioral phenotypes of neuroligin-3 R451C knockin mice. Autism Res. 2008;1:147–158. doi: 10.1002/aur.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tabuchi K, et al. A neuroligin-3 mutation implicated in autism increases inhibitory synaptic transmission in mice. Science. 2007;318:71–76. doi: 10.1126/science.1146221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Etherton MR, Blaiss CA, Powell CM, Sudhof TC. Mouse neurexin-1α deletion causes correlated electrophysiological and behavioral changes consistent with cognitive impairments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:17998–18003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910297106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blundell J, et al. Neuroligin-1 deletion results in impaired spatial memory and increased repetitive behavior. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:2115–2129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4517-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Page DT, Kuti OJ, Prestia C, Sur M. Haploinsufficiency for Pten and Serotonin transporter cooperatively influences brain size and social behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1989–1994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804428106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheh MA, et al. En2 knockout mice display neurobehavioral and neurochemical alterations relevant to autism spectrum disorder. Brain Res. 2006;1116:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moy SS, et al. Social approach in genetically engineered mouse lines relevant to autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:129–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Molina J, et al. Abnormal social behaviors and altered gene expression rates in a mouse model for Potocki–Lupski syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:2486–2495. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeLorey TM, Sahbaie P, Hashemi E, Homanics GE, Clark JD. Gabrb3 gene deficient mice exhibit impaired social and exploratory behaviors, deficits in non-selective attention and hypoplasia of cerebellar vermal lobules: a potential model of autism spectrum disorder. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;187:207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferguson JN, et al. Social amnesia in mice lacking the oxytocin gene. Nature Genet. 2000;25:284–288. doi: 10.1038/77040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winslow JT, et al. Infant vocalization, adult aggression, and fear behavior of an oxytocin null mutant mouse. Horm. Behav. 2000;37:145–155. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wersinger SR, Ginns EI, O'Carroll AM, Lolait SJ, Young WS. Vasopressin V1b receptor knockout reduces aggressive behavior in male mice. Mol. Psychiatry. 2002;7:975–984. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scattoni ML, et al. Reduced ultrasonic vocalizations in vasopressin 1b knockout mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;187:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen RZ, Akbarian S, Tudor M, Jaenisch R. Deficiency of methyl-CpG binding protein-2 in CNS neurons results in a Rett-like phenotype in mice. Nature Genet. 2001;27:327–331. doi: 10.1038/85906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guy J, Hendrich B, Holmes M, Martin JE, Bird A. A mouse Mecp2-null mutation causes neurological symptoms that mimic Rett syndrome. Nature Genet. 2001;27:322–326. doi: 10.1038/85899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gemelli T, et al. Postnatal loss of methyl-CpG binding protein 2 in the forebrain is sufficient to mediate behavioral aspects of Rett syndrome in mice. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;59:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spencer CM, Alekseyenko O, Serysheva E, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R. Altered anxiety-related and social behaviors in the Fmr1 knockout mouse model of fragile × syndrome. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4:420–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An assessment of social behaviour in Fmr1 mutant mice. Anxiety-related and abnormal social phenotypes were reported in the partition test.

- 61.Spencer CM, Graham DF, Yuva-Paylor LA, Nelson DL, Paylor R. Social behavior in Fmr1 knockout mice carrying a human FMR1 transgene. Behav. Neurosci. 2008;122:710–715. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McNaughton CH, et al. Evidence for social anxiety and impaired social cognition in a mouse model of fragile × syndrome. Behav. Neurosci. 2008;122:293–300. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ehninger D, et al. Reversal of learning deficits in a Tsc2+ mouse model of tuberous sclerosis. Nature Med. 2008;14:843–848. doi: 10.1038/nm1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fujita E, et al. Ultrasonic vocalization impairment of Foxp2 (R552H) knockin mice related to speech–language disorder and abnormality of Purkinje cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3117–3122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712298105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goorden SM, van Woerden GM, van der Weerd L, Cheadle JP, Elgersma Y. Cognitive deficits in Tsc1+ mice in the absence of cerebral lesions and seizures. Ann. Neurol. 2007;62:648–655. doi: 10.1002/ana.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scearce-Levie K, et al. Abnormal social behaviors in mice lacking Fgf17. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:344–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shu W, et al. Altered ultrasonic vocalization in mice with a disruption in the Foxp2 gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9643–9648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503739102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kwon CH, et al. Pten regulates neuronal arborization and social interaction in mice. Neuron. 2006;50:377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith SE, Li J, Garbett K, Mirnics K, Patterson PH. Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10695–10702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2178-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berman RF, Pessah IN, Mouton PR, Mav D, Harry J. Low-level neonatal thimerosal exposure: further evaluation of altered neurotoxic potential in SJL mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;101:294–309. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singer HS, et al. Prenatal exposure to antibodies from mothers of children with autism produces neurobehavioral alterations: a pregnant dam mouse model. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009;211:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.James SJ, et al. Cellular and mitochondrial glutathione redox imbalance in lymphoblastoid cells derived from children with autism. FASEB J. 2009;23:2374–2383. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ogier M, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and respiratory function improve after ampakine treatment in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10912–10917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1869-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dolen G, et al. Correction of Fragile × syndrome in mice. Neuron. 2007;56:955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lauterborn JC, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile × syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:10685–10694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2624-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paylor R, Yuva-Paylor LA, Nelson DL, Spencer CM. Reversal of sensorimotor gating abnormalities in Fmr1 knockout mice carrying a human Fmr1 transgene. Behav. Neurosci. 2008;122:1371–1377. doi: 10.1037/a0013047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou J, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 suppresses anatomical, cellular, and behavioral abnormalities in neural-specific Pten knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:1773–1783. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5685-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bolivar VJ, Walters SR, Phoenix JL. Assessing autism-like behavior in mice: variations in social interactions among inbred strains. Behav. Brain Res. 2007;176:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A survey of reciprocal social interactions in seven inbred strains of mice that are commonly used in research.

- 79.Brodkin ES, Hagemann A, Nemetski SM, Silver LM. Social approach-avoidance behavior of inbred mouse strains towards DBA/2 mice. Brain Res. 2004;1002:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen Q, Panksepp JB, Lahvis GP. Empathy is moderated by genetic background in mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McFarlane HG, et al. Autism-like behavioral phenotypes in BTBR T+tf/J. mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:152–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A comprehensive explication of social approach, preference for social novelty, juvenile reciprocal social interactions, repetitive self-grooming and control parameters in the BTBR inbred mouse strain.

- 82.Moy SS, et al. Social approach and repetitive behavior in eleven inbred mouse strains. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;191:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moy SS, et al. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behav. Brain Res. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Panksepp JB, et al. Affiliative behavior, ultrasonic communication and social reward are influenced by genetic variation in adolescent mice. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Panksepp JB, Lahvis GP. Social reward among juvenile mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:661–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ryan BC, Young NB, Crawley JN, Bodfish JW, Moy SS. Social deficits, stereotypy and early emergence of repetitive behavior in the C58/J inbred mouse strain. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;208:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scattoni ML, Gandhy SU, Ricceri L, Crawley JN. Unusual repertoire of vocalizations in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model of autism. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Silverman JL, Tolu SS, Barkan CL, Crawley JN. Repetitive self-grooming behavior in the BTBR mouse model of autism is blocked by the mGluR5 antagonist MPEP. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:976–989. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wohr M, Roullet F, Crawley J. Reduced scent marking and ultrasonic vocalizations in the BTBR T+tf/J. inbred strain mouse model of autism. Genes Brain Behav. 2010 Mar 22; doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00582.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang M, Clarke AM, Crawley JN. Postnatal lesion evidence against a primary role for the corpus callosum in mouse sociability. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:1663–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang M, et al. Social approach behaviors are similar on conventional versus reverse lighting cycles, and in replications across cohorts, in BTBR T+ tf/J, C57BL/6J and vasopressin receptor 1B mutant mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2007;1:1. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08/001.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hayashi ML, et al. Inhibition of p21-activated kinase rescues symptoms of Fragile × syndrome in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11489–11494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705003104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lord C, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A detailed description of the widely used autism diagnostic instrument, ADOS-G, which incorporates standardized contexts for standardized behavioural tasks across age ranges and language skills.

- 94.Lord C, Spence S. In: Understanding Autism: From Basic Neuroscience to Treatment. Moldin S, Rubenstein J, editors. Taylor & Francis; New York: 2006. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Landa RJ. Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in the first 3 years of life. Nature Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2008;4:138–147. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rapin I, Tuchman RF. Autism: definition, neurobiology, screening, diagnosis. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2008;55:1129–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Volkmar FR, State M, Klin A. Autism and autism spectrum disorders: diagnostic issues for the coming decade. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2009;50:108–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zwaigenbaum L, et al. Clinical assessment and management of toddlers with suspected autism spectrum disorder: insights from studies of high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1383–1391. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn APA; Washington D.C.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 100.World Health Organization . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Carter CS, Williams JR, Witt DM, Insel TR. Oxytocin and social bonding. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;652:204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb34356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miczek KA, Maxson SC, Fish EW, Faccidomo S. Aggressive behavioral phenotypes in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2001;125:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Terranova ML, Laviola G. Scoring of Social Interactions and Play in Mice During Adolescence. Wiley; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Arakawa H, Arakawa K, Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. A new test paradigm for social recognition evidenced by urinary scent marking behavior in C57BL/6J mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;190:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arakawa H, Blanchard DC, Arakawa K, Dunlap C, Blanchard RJ. Scent marking behavior as an odorant communication in mice. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2008;32:1236–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A review of the complexity of social olfactory communication in mice in social settings, including dominance hierarchies, mating and responses to predators.

- 106.Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Ethoexperimental approaches to the biology of emotion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1988;39:43–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Matsuo N, et al. Comprehensive behavioral phenotyping of ryanodine receptor type 3 (RyR3) knockout mice: decreased social contact duration in two social interaction tests. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2009;3:3. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.003.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Moy SS, et al. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:287–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-1848.2004.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A survey of sociability, perseverative behaviour and control assays in ten inbred mouse strains that are commonly used in biomedical research.

- 109.Nadler JJ, et al. Automated apparatus for quantitation of social approach behaviors in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yang M, Weber MD, Crawley JN. Light phase testing of social behaviors: not a problem. Front. Neurosci. 2008;2:186–191. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.029.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang M, Zhodzishsky V, Crawley JN. Social deficits in BTBR T+tf/J mice are unchanged by cross-fostering with C57BL/6J mothers. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2007;25:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kudryavtseva NN. Use of the `partition' test in behavioral and pharmacological experiments. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2003;33:461–471. doi: 10.1023/a:1023411217051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bakker J, Honda S, Harada N, Balthazart J. Sexual partner preference requires a functional aromatase (Cyp19) gene in male mice. Horm. Behav. 2002;42:158–171. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ferguson JN, Aldag JM, Insel TR, Young LJ. Oxytocin in the medial amygdala is essential for social recognition in the mouse. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:8278–8285. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08278.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lim MM, et al. Enhanced partner preference in a promiscuous species by manipulating the expression of a single gene. Nature. 2004;429:754–757. doi: 10.1038/nature02539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ahern TH, Modi ME, Burkett JP, Young LJ. Evaluation of two automated metrics for analyzing partner preference tests. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2009;182:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Winslow JT, Insel TR. The social deficits of the oxytocin knockout mouse. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:221–229. doi: 10.1054/npep.2002.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wrenn CC. Social transmission of food preference in mice. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2004;8:5G. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0805gs28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Galef BG., Jr. Social learning of food preferences in rodents: rapid appetitive learning. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2003;8:5D. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0805ds21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wrenn CC, Harris AP, Saavedra MC, Crawley JN. Social transmission of food preference in mice: methodology and application to galaninoverexpressing transgenic mice. Behav. Neurosci. 2003;117:21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Clipperton AE, Spinato JM, Chernets C, Pfaff DW, Choleris E. Differential effects of estrogen receptor α and β specific agonists on social learning of food preferences in female mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2362–2375. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Keverne EB. Mammalian pheromones: from genes to behaviour. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:R807–R809. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hofer MA, Shair HN. Ultrasonic vocalization, laryngeal braking, and thermogenesis in rat pups: a reappraisal. Behav. Neurosci. 1993;107:354–362. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.2.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang H, Liang S, Burgdorf J, Wess J, Yeomans J. Ultrasonic vocalizations induced by sex and amphetamine in M2, M4, M5 muscarinic and D2 dopamine receptor knockout mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Branchi I, Santucci D, Alleva E. Ultrasonic vocalisation emitted by infant rodents: a tool for assessment of neurobehavioural development. Behav. Brain Res. 2001;125:49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Holy TE, Guo Z. Ultrasonic songs of male mice. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first report to describe the complexity of male mouse vocalizations and provide indications for temporal sequencing, repeating patterns and similarities to birdsong.

- 127.Moles A, Costantini F, Garbugino L, Zanettini C, D'Amato FR. Ultrasonic vocalizations emitted during dyadic interactions in female mice: a possible index of sociability? Behav. Brain Res. 2007;182:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Scattoni ML, Crawley J, Ricceri L. Ultrasonic vocalizations: a tool for behavioural phenotyping of mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009;33:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A detailed review that emphasizes the importance of qualitative evaluation of mouse vocalizations in social situations.

- 129.Wesson DW, Keller M, Douhard Q, Baum MJ, Bakker J. Enhanced urinary odor discrimination in female aromatase knockout (ArKO) mice. Horm. Behav. 2006;49:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wersinger SR, et al. Vasopressin 1a receptor knockout mice have a subtle olfactory deficit but normal aggression. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:540–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]