Abstract

Lymphocyte-activation gene-3 (LAG-3, CD223) is a marker for recently activated effector T cells. Activated T lymphocytes are of major importance in many autoimmune diseases and organ transplant rejection. Therefore, specifically depleting LAG-3+ T cells might lead to targeted immunosuppression that would spare resting T cells while eliminating pathogenic activated T cells. We have shown previously that anti-LAG-3 antibodies sharing depleting as well as modulating activities inhibit heart allograft rejection in rats. Here, we have developed and characterized a cytotoxic LAG-3 chimeric antibody (chimeric A9H12), and evaluated its potential as a selective therapeutic depleting agent in a non-human primate model of delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH). Chimeric A9H12 showed a high affinity to its antigen and depleted both cytomegalovirus (CMV)-activated CD4+ and CD8+ human T lymphocytes in vitro. In vivo, a single intravenous injection at either 1 or 0·1 mg/kg was sufficient to deplete LAG-3+-activated T cells in lymph nodes and to prevent the T helper type 1 (Th1)-driven skin inflammation in a tuberculin-induced DTH model in baboons. T lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration into the skin was also reduced. The in vivo effect was long-lasting, as several weeks to months were required after injection to restore a positive reaction after antigen challenge. Our data confirm that LAG-3 is a promising therapeutic target for depleting antibodies that might lead to higher therapeutic indexes compared to traditional immunosuppressive agents in autoimmune diseases and transplantation.

Keywords: delayed-type hypersensitivity, LAG-3, primate, therapeutic antibodies

Introduction

Selectively inhibiting or deleting activated T lymphocytes represents a promising therapeutic approach as an alternative to current immunosuppressive treatments in autoimmunity and transplantation. One strategy might be the use of depleting antibodies that target specific antigens on activated T cells. This provides a competitive advantage of targeting only pathogeneic T cells that are specific for auto- or alloantigens without modifying the protective immunity directed against third-party antigens [1]. The proof of concept for selective depletion of pathogeneic T lymphocytes has been demonstrated in an engineered mouse model, whereby their T cells express a viral thymidine kinase suicide gene that metabolizes the non-toxic prodrug ganciclovir into a metabolite that is toxic only to dividing cells. The result was a significant delay in the rejection of skin and heart grafts and the induction of an immune tolerance in a fraction of the recipient mice [2]. However, the therapeutic translation of this strategy requires the targeting of an antigen that is highly specific for activated T cells. So far, few molecules that are expressed selectively by activated T cells have been identified. Among these are CD25, CD152, CD154 and CD223 (lymphocyte-activation gene-3; LAG-3[3]). LAG-3 is an important regulator of T cell homeostasis [4] that is related evolutionarily to CD4 and, like CD4, is associated with the T cell receptor. It has retained an affinity 2 logs higher than CD4 for their common ligand, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II. LAG-3 is a transmembrane protein that forms dimers at the surface of both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes [3,5] residing in inflamed secondary lymphoid organs or tissues (i.e. human tumours or rejected allograft), but not in spleen, thymus or blood. During inflammation LAG-3 and MHC class II are up-regulated strongly [6] and play an important role in antigen-presenting cell (APC) and dendritic cell (DC) activation [7,8]. In addition, LAG-3 is a negative regulator of T cell receptor (TCR)-mediated signal transduction in effector T cells and functions in the same manner as cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) [9–12]. Finally, LAG-3 controls activated regulatory T cells (Tregs), while it is not expressed by unstimulated natural Tregs[13]. However, LAG-3 is expressed by interleukin (IL)-10-secreting early growth response (Egr)-2+LAG-3+CD4+ Tregs associated with Peyer's patches [14].

We have shown previously that depleting anti-LAG-3 antibodies prevented the development of alloreactive effector T cells in a heart allotransplant model in rodents and represents an effective treatment for allograft rejection [15]. In this study, we have characterized a cytotoxic anti-LAG-3 chimeric antibody (chimeric A9H12) and evaluated its potential for selective therapeutic depletion in a non-human primate model of delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH), a low-invasive and non-terminal model based on the induction of local T helper type 1 (Th-1)-mediated cellular immune responses [16]. Our investigation demonstrated that LAG-3+ T lymphocytes could be depleted in vivo in primates and that this resulted in a long-lasting inhibition of immune responses in this preclinical model.

Materials and methods

Production of the chimeric A9H12 monoclonal antibody (mAb)

C57/B6 mice were immunized three times with Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with human LAG-3 cDNA, followed by an intravenous (i.v.) booster injection of a recombinant hLAG-3Ig protein purified from the supernatant of transfected CHO cells. Three days after the boost, splenocytes were fused with the X63.AG8653 fusion partner [17] to obtain hybridoma cells, using traditional techniques. The A9H12 hybridoma was selected for its antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity towards LAG-3 expressing cells and subcloned to yield a stable cell line.

A bicistronic vector coding for the variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) domains of A9H12 fused to human CL kappa and CH1-hinge-CH2-CH3 immunlglobulin (Ig)G1 regions was generated and used to transfect CHO-S cells (Invitrogen, Illkirch, France). After antibiotic selection and limiting dilutions, a stable subclone was selected to produce the chimeric A9H12 in ProCHO5 medium (Lonza, Vervier, Belgium). The product in the supernatant cell was purified by adsorption on a HiTrap recombinant Protein A FF column (GE Healthcare, Velizy, France), eluted by acid pH (Glycin HCl, 0·1 M, pH 2·8) and dialysed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen).

Flow cytometry

LAG-3+ CHO cells or human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) stimulated with 1 µg/ml of Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB; Sigma Aldrich, L'Isle D'Abeau Chesnes, France) for 48 h were used as targets. Chimeric A9H12 binding was revealed with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat F(ab′)2 anti-human IgG (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). The cross-reactivity of chimeric A9H12 against monkey T lymphocyte was assessed using baboon PBMCs isolated from whole blood by Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France), followed by red blood cell lysis. Freshly isolated PBMC were incubated for 48 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, with 10 µg/ml of concanavalin A (Sigma) in complete medium (RPMI-1640, 10% heat-inactivated baboon serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0·1 mg/ml streptomycin, 1% non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 5 mM HEPES; Sigma). PBMC were washed and stained with 10 µg/ml of anti-LAG-3 antibody (30 min at 4°C) followed by FITC-labelled goat anti-human IgG (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Cells were washed and analysed using an LSR II TM flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) with diva software. LAG-3+ T lymphocytes from inguinal lymph node biopsies were monitored by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis using a FITC-conjugated anti-LAG-3 antibody (clone 11E3) which does not compete with the A9H12 mAb.

Affinity assessment

The affinity of chimeric A9H12 was evaluated on a BIAcore 2000 using a sensor chip coated with 500 resonance units of hLAG-3Ig recombinant protein. Antibody solutions [5, 25 and 100 mM prepared in HEPES buffered saline (HBS)] were injected over a period of 3 min followed by a dissociation period of 5 min at 37°C.

ADCC

The potency of the chimeric A9H12 to induce ADCC was investigated on healthy PBMCs from cytomegalovirus (CMV)-positive donors. PBMCs were isolated from blood collected in lithium heparin tubes (BD Vacutainer®) by centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) and cryopreserved. PBMCs were thawed and cultured at 1 × 106/ml in the presence of a CMV peptide pool (mix of 138 15-mers with 11 amino acid overlaps spanning the entire sequence of the pp65 protein; BD Biosciences) in RPMI-1640, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 U/ml penicillin/50 µg/ml of streptomycin, 1× modified Eagle's medium (MEM) non-esssential amino acids; 10 mM HEPES (all from Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Hyclone, Brebières, France). The CMV peptides induced the expression of LAG-3 on CD8+ T cells, and to a lesser extent on CD4+ T cells, as well as inducing proliferation. After 5 days, 0·175 × 106/well of CMV-stimulated PBMCs were incubated in the presence of various concentrations of chimeric A9H12 or an isotype-matched control (human IgG1; Chemicon, Lyon, France) in U-bottomed 96-well plates over 4 h at 37°C to assess ADCC. The cells were then stained with CD3-phycoerythrin (PE), CD4-PE-Cy7, CD8-APC-Cy7, CD25-APC (BD Biosciences) and FITC-conjugated anti-LAG-3 mAb (17B4 antibody, 1 µg/point) for 30 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the cells were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD; BD Biosciences) and analysed by flow cytometry. After exclusion of dead cells based on size/granularity and 7-AAD staining, the percentage of LAG-3+ and CD25+ cells in the CD3+CD4+ and the CD3+CD8+ cell subpopulations were evaluated.

Animals

Baboons (Papio anubis, from the CNRS Primatology Center, Rousset, France) were negative for all quarantine tests, including a tuberculin skin test. Animals were housed at the large animal facility of our laboratory following the recommendations of the Institutional Ethical Guidelines of the Institut National de la Santé Et de la Recherche Médicale, France. All experiments were performed under general anaesthesia with Zoletil (Virbac, Carron, France). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies were performed during DTH experiments on five baboons receiving an i.v. bolus of either 1 mg/kg or 0·1 mg/kg of chimeric A9H12.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Chimeric A9H12 was quantified in baboon sera using a specific sandwich ELISA. LAG-3-Ig (Immutep, Orsay, France) was immobilized on plastic at pH 9·5 overnight at a concentration of 5 µg/ml. After saturation with 5% gelatin at 37°C for 2 h, serum diluted in PBS-0·05% Tween 20 were incubated for 4 h at room temperature, washed and revealed with a mouse anti-human IgG kappa chain antibody (EFS, Nantes, France) at a 1:2000 dilution, followed by peroxidase-labelled goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, Westgrove, PA, USA) at a 1:5000 dilution. Optical density was recorded at 450 nm after a tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) revelation period of 10 min at room temperature in the dark and addition of 25 µl 1 N sulphuric acid/well.

BCG vaccination and DTH assay

Baboons were immunized intradermally (i.d.) twice with a bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine (0·1 ml; 2–8 × 105 UFS; Sanofi Pasteur MSD, Lyon, France) in the upper region of the leg, 4 and 2 weeks before the DTH skin test. To investigate antigen-specific T cell immunity before DTH skin testing, successful immunization was confirmed by interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay (non-human primate IFN-γ ELISPOT kit; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) on freshly isolated PBMC, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Intradermal reactions (IDR) were performed with duplicate intradermal injections of two doses (2000 UI or 40 UI) of tuberculin-purified protein derivative (PPD; Symbiotics Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA) in 0·1 ml in the skin on the right back of the animals. Saline (0·1 ml) was used as a negative control. Dermal responses at the injection sites were measured using a caliper square. The diameter of each indurated erythema was measured by two observers from days 3–8, and were considered positive when > 4 mm in diameter. The mean of the reading was recorded. Skin biopsies from the DTH or control (saline) site were performed at day 4 on one duplicate and placed in Tissue Tek optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek, Villeneuve d'Ascq, France) for immunohistochemical analysis. A second IDR was performed after a 3-week washout period and animals received one i.v. injection of either 1 mg/kg or 0·1 mg/kg of chimeric A9H12 1 day before this second challenge with PPD. A third IDR was performed after a further 3–6-week washout period and animals were left untreated. In some cases, a fourth IDR was performed after another 3-month washout period and animals were also left untreated.

Immunohistochemical staining

Frozen sections (10 µm) were prepared from surgical skin biopsies embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound and maintained at −80°C. Sections were air-dried at room temperature for 1 h before acetone fixation for 10 min at room temperature. Sections were incubated with PBS containing 10% baboon serum, 2% normal goat serum and 4% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C and washed with PBS (and serum), followed by 90 min incubation with secondary antibodies. T cell infiltration analysis was performed with a rabbit anti-human CD3 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), followed by a FITC-labelled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch). CD4+ cells were analysed with a mouse anti-human CD4 (clone 13B8·2; Beckman Coulter) followed by an Alexa568-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibody (Invitrogen). CD8+ cells were analysed with a PE-labelled mouse anti-human CD8 (clone B9·11; Beckman Coulter). Macrophage infiltration was detected using a mouse anti-human CD68 (clone PGM1; Beckman Coulter), followed by an Alexa 568-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen). LAG-3+ cells were labelled with a mouse anti-human Lag3 (clone 11E3; Immutep) plus Alexa568-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibody (Invitrogen). All slides were analysed using fluorescent microscopy and AxioVision imaging software (Carl Zeiss, Le Pecq, France). A grading system from 0 to 3 was used, representing no infiltration, moderate (< 10% of the surface), medium (> 10% and < 30% of the surface) and severe (> 30% of the surface) infiltration of the observed region, evaluated on 10 microscope fields chosen randomly on the preparation.

Results

In vitro characterization of the anti-LAG-3 chimeric A9H12 mAb

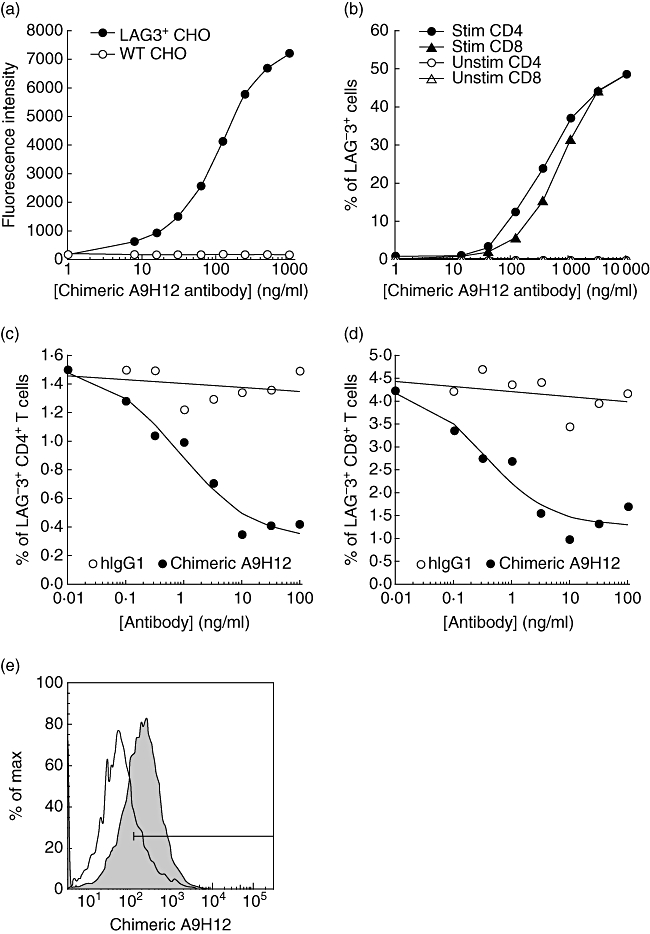

The murine A9H12 mAb was selected because of its high binding affinity to LAG-3 and its potency at inducing complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and ADCC on LAG-3+ cells (not shown). A chimeric form of A9H12 was generated in CHO cells by fusing the VH and VL chain regions of murine A9H12 to the constant regions of human IgG1. The ability of the resulting antibody to bind LAG-3 efficiently was tested on cells expressing an ectopic or a natural LAG-3 ligand (Fig. 1a,b, respectively). The analysis of real-time interaction performed using BIAcore surface plasmon resonance on a sensor chip coated with recombinant hLAG-Ig revealed good affinity of the antibody to its antigen (kD 5 × 10−10 M, Kon 2 × 106/M/s, Koff 1 × 10−3/s). The in vitro potency of the chimeric A9H12 mAb to induce cell-mediated cytotoxicity was studied using LAG-3+ primary T cells. To induce physiologically the expression of LAG-3 on T cells, PBMCs were stimulated with a CMV peptide pool. Stimulation induced the expression of the activation marker CD25 and LAG-3 on about 4·18 ± 0·13% of CD8+ T cells and 1·40 ± 0·04% of CD4+ T cells. The presence of the chimeric A9H12 mAb for 4 h dramatically reduced the percentage of living activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells showing the killing of LAG-3+ cells induced by the antibody (Fig. 1c,d, respectively). A 70% reduction in the number of LAG-3+ cells was observed both in the CD4 and the CD8 subsets at a 10 ng/ml antibody concentration. The half-maximum effective concentration was found at the ng/ml level [1 ± 0·4 ng/ml for CD4+ T cells and 0·7 ± 0·4 ng/ml for CD8+ T cells, mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) of five experiments]. The observed effect is not due to competition between the chimeric A9H12 mAb and the 17B4-FITC mAb used to reveal LAG-3, as the binding of 17B4-FITC is not inhibited by a threefold excess of the chimeric A9H12 mAb (not shown). A putative internalization of the membrane LAG-3 induced by the chimeric A9H12 was excluded because the disappearance of activated T cells was also observed with an anti-CD25 antibody (not shown). CDC and ADCC are probably the dominant mode of action of this antibody, as no agonist or antagonist effect could be evidenced in mixed lymphocyte reactions (data not shown). The chimeric A9H12 mAb cross-reacted with baboon LAG-3 because it bound to similar percentages of activated PBMC to that found for human cells, and did not bind to resting baboon PBMC (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

In vitro characterization of the chimeric A9H12 monoclonal antibody (mAb). Binding of chimeric A9H12 mAb at indicated concentrations to control or lymphocyte-activation gene-3 (LAG-3) Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (a) and to Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB)-stimulated (Stim) or resting (Unstim) peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (b). A fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human immunoglobulin (Ig)G was used to reveal the chimeric A9H12 mAb bound to the cells. The results in (a) represent the median of fluorescence intensity as a function of antibody concentrations. The graph in (b) presents the percentage of LAG-3+ cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subpopulations. (c,d) An antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) assay was performed with PBMCs from a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-positive human donor stimulated with a CMV peptide pool for 5 days. Various concentrations of chimeric A9H12 mAb or human IgG1 were added for 4 h and the viability of activated CD4+ or CD8+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Data shown are from one representative experiment of five. (e) Cross-reactivity of chimeric A9H12 with the baboon was assessed by flow cytometry. Target cells were concanavalin A-activated (shaded profiles) or resting (empty profiles) baboon PBMC.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic aspects of chimeric A9H12

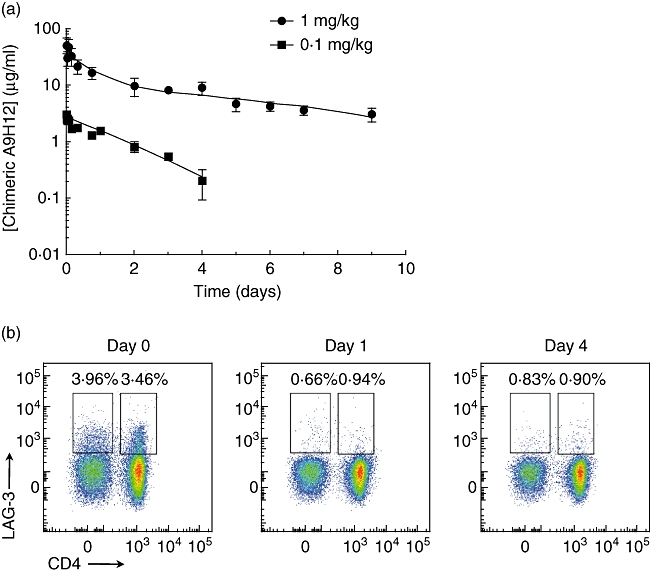

According to a two-compartment model, after an intravenous bolus administration of 1 mg/kg of chimeric A9H12 (n = 2), the elimination half-life was 86·1 ± 31·3 h (Fig. 2a). Three other animals received 0·1 mg/kg of chimeric A9H12. In that case, the elimination half-life was calculated as 23·8 ± 6·8 h (Fig. 2a). In order to evaluate whether chimeric A9H12 can deplete LAG-3+ target cells in vivo, inguinal lymph nodes were biopsied before, and on days 1 and 4 after treatment. The percentage of LAG-3+ cells was then evaluated by flow cytometry. We observed a reduction of both CD4+ and CD4−LAG3+CD3+ T lymphocytes after chimeric A9H12 administration (Fig. 2b). CD4−CD3+ T lymphocytes represent mainly CD8+ T cells, but can also contain a few NK T cells. This was not due to immunological masking, as the detecting fluorescent anti-LAG-3 antibody used did not compete with chimeric A9H12. As expected, administration of chimeric A9H12 induced no modification of lymphocyte count in the peripheral blood.

Fig. 2.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of chimeric A9H12. Blood samples were drawn at the indicated time-points from baboons treated intravenously (i.v.) with 1 or 0·1 mg/kg of chimeric A9H12 (a). Serum trough levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (b) Representative fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing lymphocyte-activation gene-3 (LAG-3) after gating on CD3+ cells in lymph nodes at days 0, 1 and 4 after a 0·1 mg/kg i.v. injection of chimeric A9H12.

Chimeric A9H12 controls IDR to tuberculin

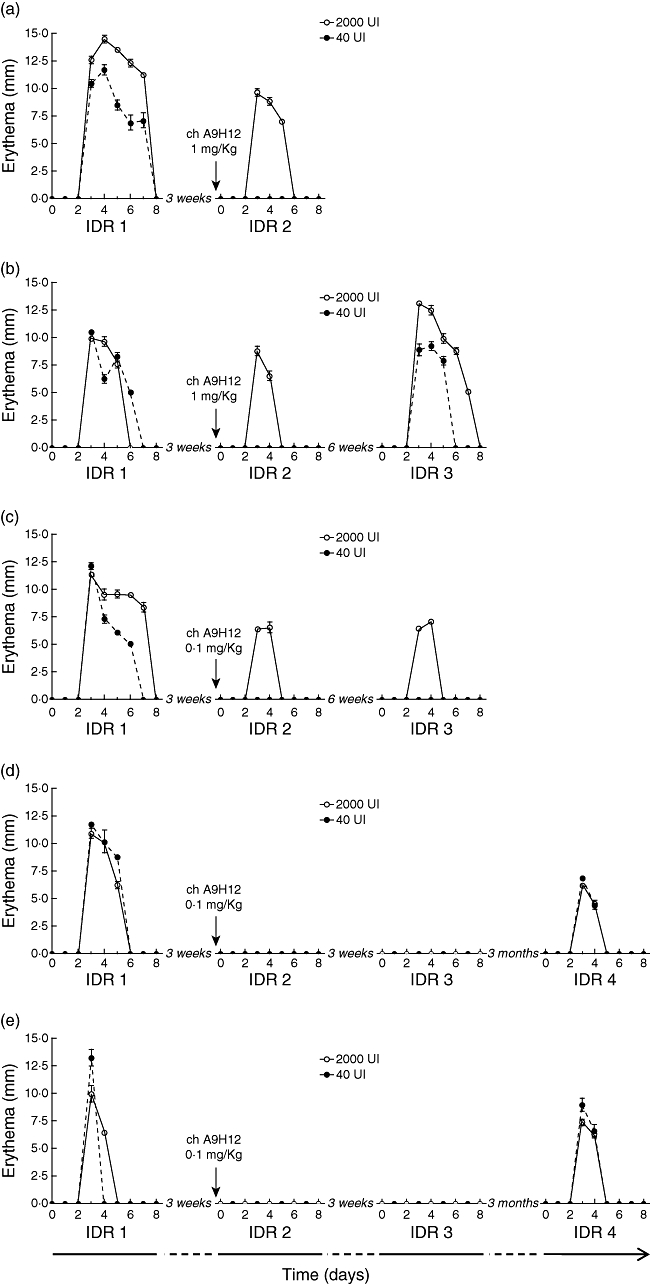

To test the efficacy of chimeric A9H12 in vivo, we established a DTH model in baboons after sensitization with BCG vaccine. That sensitized animals were indeed immunized was controlled after 1 month with an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay on PBMC. Of eight baboons vaccinated with BCG, all but one became immunized. Unsensitized animals presented a frequency of 1/61 845 ± 1/13 329 PBMC responding in vitro to tuberculin-PPD, and this rose to a frequency of 1/7 842 ± 1/1578 in sensitized animals. Two immunized baboons used as controls were challenged with tuberculin IDR three consecutive times over 5 months and demonstrated consistent and reproducible erythema after each IDR (Table 1). Two test animals challenged with an initial IDR showed a measurable erythema (minimal size of 4 mm) from days 3–6 or 8 after injection of 2000 or 40 UI PPD. After a 3-week washout period, the same animals were treated with 1 mg/kg chimeric A9H12 and were challenged the next day with a second IDR. They showed no cutaneous erythema with the 40 UI PPD dose and a milder reaction (diameter of the erythema and reaction time) with the 2000 UI PPD dose (Fig. 3a,b). One of these animals was challenged again for a third IDR 6 weeks later (a period of time sufficient to completely eliminate chimeric A9H12 from the blood representing up to 10 half-lives; data not shown) and showed a restored DTH reaction with an erythema similar to the first IDR (Fig. 3b).

Table 1.

Summary of intradermal reactions (IDR) responses after 40 UI tuberculin-purified protein derivative (PPD) intradermal injections

| Animal | ch A9H12 dose | IDR no. 1 | IDR no. 2 + ch A9H12 or vehicle | IDR no. 3 | IDR no. 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control 1 | 0 mg/kg | + | + | + | + |

| Control 2 | 0 mg/kg | + | + | + | + |

| V888F | 1 mg/kg | + | − | n.d. | n.d. |

| VX20 | 1 mg/kg | + | − | + | n.d. |

| PA997C | 0·1 mg/kg | + | − | − | + |

| V936BB | 0·1 mg/kg | + | − | − | + |

| V987B | 0·1 mg/kg | + | − | − | n.d. |

Ch A9H12, chimeric A9H12; n.d., not determined.

Fig. 3.

Delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses of animals treated with chimeric A9H12. Cutaneous erythema diameter measured at the injection site after 40 UI or 2000 UI tuberculin-purified protein derivative (PPD) intradermal injections, repeated two to four times over a maximum of 18 weeks. (a,b) Two individual animals treated with 1 mg/kg chimeric A9H12. (c–e) Three individual animals treated with 0·1 mg/kg chimeric A9H12. Data are mean ± standard deviation of the diameter of each erythema measured over 8 days following the antigenic challenge, performed in duplicate and by two observers.

In a second round of experiments, three other immunized animals were treated with 0·1 mg/kg on day 1 of the second IDR and showed a more pronounced inhibition of DTH reaction, as two of these animals did not develop any cutaneous erythema even with the 2000 UI PPD injection dose (Fig. 3d,e). The third animal developed no erythema with the 40 UI PPD injection and a decreased erythema (diameter and reaction time) with the 2000 UI PPD injection dose (Fig. 3c). The inhibitory action of chimeric A9H12 injected at 0·1 mg/kg was long-lasting, because subsequent IDRs performed 3-6 weeks after injection were similar to the second IDR performed during treatment. A 3-month washout period was actually necessary to recover a positive reaction in two of these animals (Fig. 3d,e).

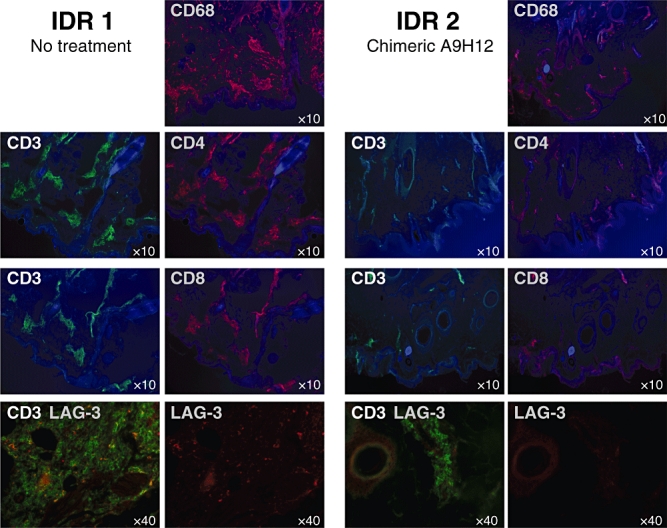

Skin biopsies were performed on day 3 after 40 UI PPD challenges on one duplicate IDR and processed for analysis by immunofluorescence. In accordance with the clinical DTH observations, these data revealed a reduction in T cell and macrophage infiltration after administration of chimeric A9H12 at 1 and 0·1 mg/kg (Table 2 and Fig. 4), an effect that persisted partially at the third IDR (in the absence of further administration of chimeric A9H12). Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were found reduced in the infiltrates after treatment. In agreement with our observations in lymph nodes (Fig. 2b), LAG-3+ cells in skin biopsies represented a minority of infiltrating T cells which, none the less, was also reduced after administration of chimeric A9H12.

Table 2.

Quantification of skin biopsies infiltration by CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, lymphocyte-activation gene-3 (LAG-3+) and CD68+ cells after 40 UI tuberculin-purified protein derivative (PPD) intradermal injections

| Animal no. | IDR no. and treatment | CD3 | CD4 | CD8 | LAG-3 | CD68 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V888F | 1, control | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 2, 1 mg/kg Chi A9H12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| VX20 | 1, control | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 2, 1 mg/kg Chi A9H12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3, control | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| V987B | 1, control | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 2, 0·1 mg/kg Chi A9H12 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3, control | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| V936BB | 1, control | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 2, 0·1 mg/kg Chi A9H12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3, control | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 4, control | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| PA997C | 1, control | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 2, 0·1 mg/kg Chi A9H12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 3, control | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| 4, control | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

0: infiltration not detectable; 1: moderate infiltration (< 10% of the surface); 2: medium infiltration (> 10% and < 30% of the surface); 3: severe infiltration (> 30% of the surface). IDR, intradermal reaction.

Fig. 4.

T lymphocyte and macrophage skin infiltration. Skin infiltration by CD3+ (green staining) and CD4+, CD8+, LAG-3+ and CD68+ cells (red staining) of a representative animal at the site of injection of 40 UI of purified protein derivative (PPD) during the first untreated intradermal reactions (IDR; left panel) and during the second IDR treated intravenously (i.v.) with 0·1 mg/kg of chimeric A9H12 (right panel). CD3 and, respectively, CD4, CD8 and lymphocyte-activation gene-3 (LAG-3) staining have been realized on consecutive slides. Autofluorescence with an ultraviolet filter (blue colour) was used to visualize tissue structure at ×10 magnification. Lower pictures: CD3 and LAG-3 co-localization and LAG-3 alone (red) are shown (lower pictures). Magnification (×10−1) is indicated on each picture.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the biological effect of the depletion of LAG-3+ cells in a non-human primate model of delayed-type hypersensitivity. First, we demonstrated that the chimeric A9H12 anti-LAG-3 monoclonal antibody could deplete in vitro by ADCC and in vivo in lymph nodes CD4+ and CD8+ target cells expressing LAG-3+. In vivo chimeric A9H12 showed efficacy at reducing skin inflammation in a tuberculin-induced DTH model in the baboon, an effect that persisted after elimination of the antibody.

Using antibodies that specifically deplete activated T cells represents a promising therapeutic strategy to prevent and/or treat autoimmune diseases and transplant rejection. Anti-CD40L antibodies, for example, prolong allograft survival in monotherapy, and show potential to induce immune tolerance in association with other immunosuppressants [18,19]. More specifically, experiments with anti-CD40L antibodies sharing non-Fc effector function demonstrated the importance of the depleting cytotoxic activity in addition to co-stimulation inhibition [20,21]. However, the use of anti-CD40L antibodies in the clinic was compromised by thromboembolic complications due to the presence of CD40L on platelets [22]. Another example concerns anti-CD25 (IL-2Rα) antibodies sharing partial depleting activity [23]. However, as CD25 is also expressed on natural Treg cells at very high levels this might interfere with the development of normal immune regulation by Tregs[24]. Because LAG-3 is expressed by activated CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes residing in inflamed secondary lymphoid organs or tissues (i.e. human tumours or rejected allograft [3,5,15]), is up-regulated strongly during inflammation [6] and is not expressed on unstimulated natural CD4+CD25+forkhead box P3 (FoxP3+) Tregs[13], it might represent an interesting therapeutic target with potential immunoregulatory properties. Of course, LAG-3 is expressed by activated Tregs[13] and potentially other Treg types [14] and participates in the suppressive function of Tregs[15,25]). Therefore, depleting anti-LAG-3 antibodies might also oppose the development of immune regulation.

The data presented here indicate that the depletion of LAG-3+ cells has an inhibitory action on T helper type 1 (Th1)-mediated immune responses into the skin after antigen challenge. The most straightforward explanation supporting our observations is the physical elimination of a significant part of presumably antigen-specific activated T cells into the draining lymph nodes that therefore have reduced capacities to migrate back into the skin and to induce inflammation. However, it has been demonstrated that skin-activated Treg cells, presumably expressing LAG-3, migrate to the lymph nodes during cutaneous immune responses where they inhibit immune responses [26]. Therefore, we could speculate that eliminating LAG-3-positive cells during an intradermal reaction has two opposite actions: on one hand, it could indeed eliminate effector T cells and block inflammation, and on the other hand it could prevent Treg cells from inhibiting immune responses in the draining lymph node. The net result would still be a reduction of the inflammation, due to the absence of effector cells. We found that administration of chimeric A9H12 at doses of 1 or 0·1 mg/kg both inhibited erythema after skin challenge. However, only the low dose induced a situation where animals were hyporesponsive or non-responsive to subsequent skin challenges, several weeks or months after treatment, when chimeric A9H12 antibody has been eliminated. The recovery of a normal response 6 weeks after initial treatment with 1 mg/kg chimeric A9H12 indicated that antigen-specific T cells had not all been depleted. Thus, it is conceivable that the low dose also did not completely eliminate antigen-specific T cells. However, low doses were as efficient and induced prolonged suppression. It is possible that this prolonged suppression was due to Treg cells, which might be eliminated with high doses of chimeric A9H12 but not, or to a lesser extent, with low doses. That anti-LAG-3 antibodies can eliminate Treg cells was demonstrated previously in a transplantation model, where very high doses could prevent tolerance induction and even break an established tolerance [15].

The DTH response has been well characterized in immunized animals, including rhesus monkeys [27,28], and humans as an antigen-specific reaction resulting in erythema and induration (within 24–72 h) at the site of injection. It is characterized as a type IV hypersensitivity reaction involving cell-mediated immunity initiated by CD4 and CD8 T cells. The exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis that we used here drives a cytokine-induced differentiation of naive CD4 Th cells to Th1 [29], and therefore can be considered as a surrogate in vivo assay for psoriasis inflammation.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that selectively targeting activated T cells with a LAG-3 cytotoxic antibody prevents T cell-driven skin inflammation in a preclinical DTH model in non-human primates. Our data suggest that depleting pathogen-specific activated LAG-3+ T cells might represent a promising new therapeutic approach in diseases where self-antigens (or alloantigens in the case of transplantation) and activated T cells (e.g. multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, different forms of thyroiditis, diabetes type I) are involved.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the ‘Progreffe’ foundation, by a grant from the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche no. ANR-06-RIB-010–01 and by a research grant from Immutep SA. The authors thank R. Bredoux for assistance in project management and C. Mary and A. Cariot for advice in pharmacokinetic evaluation.

Disclosure

T. H., F. T. and B. V. are inventors of the WO2008132601(A1) patent application on anti-LAG-3 antibodies.

References

- 1.Salvana EM, Salata RA. Infectious complications associated with monoclonal antibodies and related small molecules. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:274–90. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas-Vaslin V, Bellier B, Cohen JL, et al. Prolonged allograft survival through conditional and specific ablation of alloreactive T cells expressing a suicide gene. Transplantation. 2000;69:2154–61. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200005270-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Triebel F, Jitsukawa S, Baixeras E, et al. LAG-3, a novel lymphocyte activation gene closely related to CD4. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1393–405. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triebel F. LAG-3: a regulator of T-cell and DC responses and its use in therapeutic vaccination. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:619–22. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huard B, Mastrangeli R, Prigent P, et al. Characterization of the major histocompatibility complex class II binding site on LAG-3 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5744–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avice MN, Sarfati M, Triebel F, Delespesse G, Demeure CE. Lymphocyte activation gene-3, a MHC class II ligand expressed on activated T cells, stimulates TNF-alpha and IL-12 production by monocytes and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:2748–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreae S, Piras F, Burdin N, Triebel F. Maturation and activation of dendritic cells induced by lymphocyte activation gene-3 (CD223) J Immunol. 2002;168:3874–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Workman CJ, Wang Y, El Kasmi KC, et al. LAG-3 regulates plasmacytoid dendritic cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2009;182:1885–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huard B, Gaulard P, Faure F, Hercend T, Triebel F. Cellular expression and tissue distribution of the human LAG-3-encoded protein, an MHC class II ligand. Immunogenetics. 1994;39:213–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00241263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannier S, Tournier M, Bismuth G, Triebel F. CD3/TCR complex-associated LAG-3 molecules inhibit CD3/TCR signaling. J Immunol. 1998;161:4058–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Workman CJ, Vignali DA. The CD4-related molecule, LAG-3 (CD223), regulates the expansion of activated T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:970–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macon-Lemaitre L, Triebel F. The negative regulatory function of the lymphocyte-activation gene-3 co-receptor (CD223) on human T cells. Immunology. 2005;115:170–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang CT, Workman CJ, Flies D, et al. Role of LAG-3 in regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:503–13. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamura T, Fujio K, Shibuya M, et al. CD4+CD25-LAG3+ regulatory T cells controlled by the transcription factor Egr-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13974–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906872106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haudebourg T, Dugast AS, Coulon F, et al. Depletion of LAG-3 positive cells in cardiac allograft reveals their role in rejection and tolerance. Transplantation. 2007;84:1500–6. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000282865.84743.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black CA. Delayed type hypersensitivity: current theories with an historic perspective. Dermatol Online J. 1999;5:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coll JM. Injection of physiological saline facilitates recovery of ascitic fluids for monoclonal antibody production. J Immunol Methods. 1987;104:219–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirk A, Harlan D, Amstrong N, et al. CTLA4Ig and anti-CD40 ligand prevent renal allograft rejection in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8789–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillonneau C, Seveno C, Dugast AS, et al. Anti-CD28 antibodies modify regulatory mechanisms and reinforce tolerance in CD40Ig-treated heart allograft recipients. J Immunol. 2007;179:8164–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monk NJ, Hargreaves RE, Marsh JE, et al. Fc-dependent depletion of activated T cells occurs through CD40L-specific antibody rather than costimulation blockade. Nat Med. 2003;9:1275–80. doi: 10.1038/nm931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrant JL, Benjamin CD, Cutler AH, et al. The contribution of Fc effector mechanisms in the efficacy of anti-CD154 immunotherapy depends on the nature of the immune challenge. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1583–94. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirabet M, Barrabes JA, Quiroga A, Garcia-Dorado D. Platelet pro-aggregatory effects of CD40L monoclonal antibody. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:937–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strom TB, Kelley VR, Woodworth TG, Murphy JR. Interleukin-2 receptor-directed immunosuppressive therapies: antibody- or cytokine-based targeting molecules. Immunol Rev. 1992;129:131–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benghiat FS, Graca L, Braun MY, et al. Critical influence of natural regulatory CD25+ T cells on the fate of allografts in the absence of immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2005;79:648–54. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000155179.61445.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camisaschi C, Casati C, Rini F, et al. LAG-3 expression defines a subset of CD4(+)CD25(high)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells that are expanded at tumor sites. J Immunol. 2010;184:6545–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomura M, Honda T, Tanizaki H, et al. Activated regulatory T cells are the major T cell type emigrating from the skin during a cutaneous immune response in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:883–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI40926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maddison SE, Hicklin MD, Conway BP, Kagan IG. Transfer factor: delayed hypersensitivity to Schistosoma mansoni and tuberculin in Macaca mulatta. Science. 1972;178:757–9. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4062.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cordoba F, Wieczorek G, Preussing E, Bigaud M. Modeling of delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) in the non-human primate (NHP) Drug Discov Today. 2008;5:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi K, Kaneda K, Kasama T. Immunopathogenesis of delayed-type hypersensitivity. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;53:241–5. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]