Abstract

There is emerging evidence that C1 domains, motifs originally identified in PKC isozymes and responsible for binding of phorbol esters and diacylglycerol, interact with the Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum protein p23 (Tmp21). In this study, we investigated whether PKCδ, a kinase widely implicated in apoptosis and inhibition of cell cycle progression, associates with p23 and determined the potential functional implications of this interaction. Using a yeast two-hybrid approach, we found that the PKCδ C1b domain associates with p23 and identified two key residues (Asp245 and Met266) implicated in this interaction. Interestingly, silencing p23 from LNCaP prostate cancer cells using RNAi markedly enhanced PKCδ-dependent apoptosis and activation of PKCδ downstream effectors ROCK and JNK by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. Moreover, translocation of PKCδ to the plasma membrane by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate was enhanced in p23-depleted LNCaP cells. Notably, a PKCδ mutant that failed to interact with p23 triggered a strong apoptotic response when expressed in LNCaP cells. In summary, our data compellingly support the concept that C1 domains have dual roles both in lipid and protein associations and provide strong evidence that p23 acts as an anchoring protein that retains PKCδ at the perinuclear region, thus limiting the availability of this kinase for activation in response to stimuli.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Diacylglycerol, Phorbol Esters, Protein Kinase C (PKC), Protein Targeting, Signal Transduction, C1 Domain, Prostate Cancer, p23/Tmp21

Introduction

p23/Tmp21 (hereafter referred to as p23) is a type I transmembrane protein that belongs to the p24 endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi cargo family and plays critical roles in protein transport, organization of membrane structure, and the secretory pathway. Members of the p24 family have been widely implicated as COP (coat protein) vesicle cargo receptors, and they are involved in COP vesicle budding and the organization of the Golgi apparatus (1). In addition to the well established role of p23 in vesicle formation and cargo transport in the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi (2–5), this protein has been implicated in several other cellular functions, including the recruitment of the small GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor 1 to the Golgi apparatus (6, 7) and ADP-ribosylation factor 1-dependent assembly of actin in the Golgi (8). p23 also is a component of the presenilin complex at the plasma membrane and modulates γ-secretase cleavage (9).

In a previous yeast two-hybrid screening, we established that p23 physically associates with α- and β-chimaerins, Rac GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs)4 regulated by the lipid second messenger diacylglycerol (DAG) and DAG mimetic analogs such as the phorbol esters (10–13). Mutational and deletional studies revealed that this interaction is mediated by the C1 domain present in chimaerins (10). The 50–51-amino acid cysteine-rich C1 domains were identified originally in PKC isozymes as the sites for DAG and phorbol ester binding. C1 domains drive the recruitment of proteins to internal membranes and, in this manner, facilitate their access to docking proteins and effectors. More recently, we identified key residues within the C1 domain in β2-chimaerin responsible for binding p23 and perinuclear targeting of this Rac-GAP (14). Interestingly, isolated C1 domains from PKC isozymes bind to p23, suggesting a role for this p24 family member in perinuclear docking of C1 domain-containing proteins. Yeast two-hybrid, co-precipitation, and localization studies revealed a high degree of specificity for this interaction. Indeed, p23 binds tandem C1 domains from classical PKCs (cPKCα) and novel PKCs (nPKCδ and nPKCϵ) but not the C1 domain from atypical aPKCζ (14). The fact that chimaerins and PKCδ have been found in the cellular perinucleus raised the possibility that p23 is implicated in intracellular targeting of these signaling proteins. Such scenario seems to be true for β2-chimaerin, as disruption of its interaction with p23 impairs β2-chimaerin perinuclear association (14).

The PKC serine/threonine kinases have been implicated widely in multiple physiological and pathological processes, including differentiation, mitogenesis, tumor progression, cell survival, and apoptosis (15). PKCδ has been established as a prominent proapoptotic kinase in various cellular models, including prostate cancer, glioma, and thyroid cancer cells (16–18). Our laboratory established that activation of PKCδ by phorbol esters leads to apoptosis of androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells (18–24). PKCδ activity is also required for cell death induced by DNA-damaging agents such as etoposide or doxorubicin (25, 26). The proapoptotic effect of PKCδ in prostate cancer cells is mediated by the autocrine secretion of death factors and involves the activation of JNK and RhoA/ROCK pathways (21, 22).

In the present study, we examined the potential implication of p23 in PKCδ function. We found that PKCδ interacts with p23 via its C1 domain and that this association has significant functional implications for PKCδ-mediated apoptosis and signaling in prostate cancer cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). DAPI and doxorubicin were obtained from Sigma. GF 109203X was purchased from BIOMOL (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Cell Culture

LNCaP human prostate cancer cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin (100 units/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml). HeLa and COS-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin (100 units/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

RNAi

21-bp dsRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon Research, Inc. (Dallas, TX) or Ambion (Austin, TX) and transfected into LNCaP cells using the Amaxa Nucleofector (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD) following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Experiments were performed 48 h after transfection. The following targeting sequences were used: CCATGAGTTTATCGCCACCTT (PKCδ1), CCATGTATCCTGAGTGGAA (PKCδ2), and GCCAUAUUCUCUACUCCAAUU (p23) (9). As a control RNAi, we used the Silencer® negative control 7 (Ambion).

For the generation of p23-depleted LNCaP cell lines, we used shRNA lentiviruses. Briefly, LNCaP cells were infected with MISSION® Lentiviral Transduction particles encoding p23 shRNAs following the manufacturer's instructions. p23 shRNA target sequences were as follows: CCGGCCAACTCGTGATCCTAGACATCTCGAGATGTCTAGGATCACGAGTTGGTTTTT (p23#1) and CCGGCGCTTCTTCAAGGCCAAGAAACTCGAGTTTCTTGGCCTTGAAGAAGCGTTTTT (p23#2). Stable cell lines (pools) were generated by selection with puromycin (1 μg/ml).

Yeast Two-hybrid Assay

pLexA expression vectors, which contain a His marker, were co-transformed into the yeast strain EGY48 together with pB42AD-HA-tagged expression vectors, which have a Trp marker, and the p8OP-LacZ reporter vector (Ura marker). Transformants were plated on yeast dropout medium lacking Trp, Ura, and His, thereby selecting for the plasmids encoding proteins capable of a two-hybrid interaction, as evidenced by transactivation of the LacZ reporter gene. A detailed explanation of the methodology used for these experiments has been described previously (10).

Western Blot

Cells were harvested into lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Protein determinations were performed with a Bio-Rad protein assay. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg/lane) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked with either 5% milk or 5% BSA in 0.05% Tween 20/PBS and then incubated with the first antibody overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed three times with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS and then incubated with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:3000; Bio-Rad). Bands were visualized with the ECL Western blotting detection system. The following primary antibodies were used: anti- GST, anti-GFP, and anti-HA (Covance, Emeryville, CA); anti-V5 (Invitrogen); anti-PKCδ (BD Transduction Laboratories); anti-actin (Sigma); anti-phospho-JNK and anti-JNK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); anti-pLexA and anti-p23 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); or anti-phospho-myosin phosphatase target subunit 1-Thr850 (Millipore). All antibodies were used at a 1:1000 dilution except for the anti-actin antibody, which was used at a 1:20,000 dilution.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Cells were washed once with PBS and then lysed for 10 min at 4 °C in 800 μl of a lysis buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mm β-glycerophosphate, and protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g, and the supernatants were precleared with 15 μl of protein A-agarose beads (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4 °C. After a short centrifugation, supernatants were incubated with either PKCδ antibody (2 μg) or control IgG (at 4 °C for 2 h). Protein A-agarose beads (20 μl) were then added, and the mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 2 h. Beads were extensively washed in lysis buffer and boiled. Samples were resolved in 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes for Western blot analysis.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

For PCR-based mutagenesis, we utilized the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), using GFP-PKCδ (WT) as a template. In the first round of PCR, we used the following primers (mutated nucleotides are underlined) to generate D245G-PKCδ: forward primer, 5′-GAGCCCCACCTTCTGTGGCCACTGTGGCAG and reverse primer, 5′-CTGCCACAGTGGCCACAGAAGGTGGGGCTC. To generate the double mutant D245G/M266G PKCδ, we used D245G-PKCδ as a template, 5′-GTGTGAAGATTGTGGCGGGAATGTGCACCAC as a forward primer, and 5′-GTGGTGCACATTCCCGCCACAATCTTCACAC as a reverse primer.

Apoptosis Assays and Flow Cytometry

The incidence of apoptosis was determined as we described previously (18). Briefly, cells were trypsinized, mounted on glass slides, fixed in 70% ethanol, and then stained for 20 min with 1 mg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Apoptotic cells were characterized by chromatin condensation and fragmentation when examined by fluorescence microscopy. The incidence of apoptosis in each preparation was analyzed by counting ∼300 cells.

In other experiments, LNCaP cells were transfected with pEGFP vectors encoding WT-PKCδ or D245G/M266G-PKCδ. After 72 h, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol and stained with propidium iodide (1 mg/ml). The percentage of cells (GFP-transfected and nontransfected) in sub-G0/G1 was determined in an EPICS XL flow cytometer (Coulter Corp., Hialeah, FL). For each treatment, ∼7500 events were recorded.

Immunostaining and Confocal Microscopy

Cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, and then washed briefly with PBS. For immunostaining, cells were incubated with PBS containing 0.5% SDS/5% β-mercaptoethanol (37 °C, 30 min) and blocked in 5% BSA in PBS for 30 min. After washing twice with PBS, cells were incubated for 2 h with anti-PKCδ, anti-p23, or anti-V5 antibodies (1:200). Secondary goat FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit or donkey Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies (1:1000) were used. For studies on GFP-PKCδ localization, LNCaP cells were transfected with pEGFP-PKCδ using the Amaxa Nucleofector and treated 48 h later with PMA. In all cases, cover slides were mounted with Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL) and visualized with a laser-scanning fluorescence microscope (LSM 410 or 510; Carl Zeiss). For quantification of co-localization, images (RGB) from red and green channels were converted into 8-bit images in ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and Pearson's r (Rr) was calculated using this software as described previously (14).

Time-lapse Microscopy

LNCaP cells were transfected with pEGFP-PKCδ using the Amaxa Nucleofector and seeded into collagen-coated, glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) for 48 h. Cells were cultured for 20 h in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 5 mm HEPES, and monitored under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000U) at a 488-nm excitation wavelength with a 515-nm long pass barrier filter.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Student's t test. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

p23 Is a PKCδ-interacting Protein

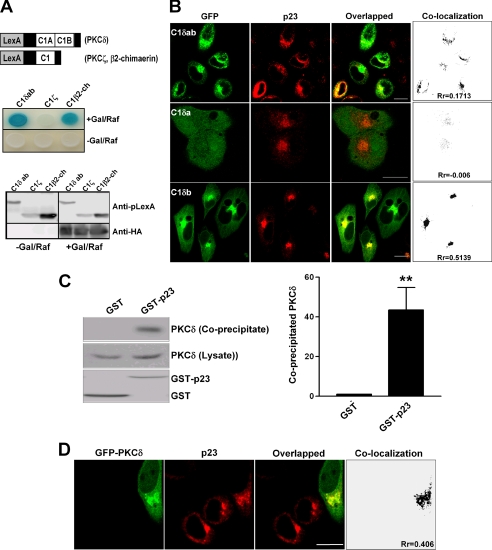

In previous studies, we showed that the perinuclear protein p23 associates with the Rac-GAP α- and β-chimaerin as well as with PKCϵ, an interaction that is mediated through their C1 domains (10, 14). The C1 domains in PKCδ, a kinase widely implicated in cell growth arrest and apoptosis, play essential roles in intracellular targeting. Due to the relevance of PKCδ in normal physiology and disease, it is highly important to understand the mechanisms that control its activity. We reasoned that PKCδ interacts with p23 through the C1 domain region. To test this hypothesis, we used a yeast two-hybrid system. A pLexA construct comprising both C1 domains (C1a and C1b) from PKCδ was generated (pLexA-C1δab, amino acids (aa) 123–297) (Fig. 1A, upper panel). This plasmid was co-transformed with pB42AD-p23 (HA-tagged, aa 108–208, a fragment that interacts with the C1 domain in chimaerins) into EGY48 yeast containing p8OP-LacZ vector (10). As a positive control, we used pLexA-C1β2-ch (aa 179–281), which encodes the C1 domain in β2-chimaerin. As a negative control, we used a similar construct encompassing the PKCζ C1 domain (pLexA-C1ζ, aa 95–197), which fails to interact with p23 (14). The triple vector co-transformants were selected by plating the yeast into SD/−Ura/−His/−Trp dropout plates. As expected, expression of pLexA-fused proteins was observed both in galactose/raffinose (+Gal/Raf) plates and in glucose plates (−Gal/Raf), whereas HA-tagged pB42AD-p23 (aa 108–208) was only expressed in +Gal/Raf induction plates (Fig. 1A, lower panel). Similar to C1β2-ch, C1δab strongly interacts with p23, as revealed by induction of the LacZ reporter (blue). On the other hand, C1ζ does not interact with p23 (Fig. 1A, middle panel). As expected, no interaction was observed in −Gal/Raf (glucose) plates. To determine which C1 domain in PKCδ associates with p23, we generated pLexA constructs for C1a or C1b (aa 159–208 and 231–280, respectively). We found that the C1b domain strongly interacts with p23 in a yeast two-hybrid assay. Unfortunately, the C1a construct transactivated the LacZ promoter gene in −Gal/Raf (glucose) plates, which precluded an analysis using this approach (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

The C1 domain region in PKCδ interacts with p23. A, upper panel, schematic representation of C1 domains of PKCδ (C1δab), PKCζ (C1ζ), and β2-chimaerin (C1β2-ch) fused to pLexA. Middle panel, EGY48 yeast (containing the p8OP-LacZ vector) was co-transformed with pLexA-C1δab, pLexA-C1ζ, or pLexA-C1β2-ch, together with pB42AD-HA-tagged p23 (aa 108–208). β-Galactosidase activity was determined after induction with galactosidase/raffinose (+Gal/Raf) or no induction (−Gal/Raf) 72 h after transformation. Lower panel, expression of pLexA-fused C1 domains, as determined by Western blot using an anti-pLexA antibody and pB42AD-HA-p23 (aa 108–208) using an anti-HA antibody. B, the C1b domain of PKCδ co-localizes with p23 at the perinuclear region. HeLa cells were co-transfected with pEGFP-fused C1δab, C1δa, or C1δb, and pcDNA3.1-V5-p23. After 48 h, cells were fixed and visualized by confocal microscopy. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments. Co-localization and Pearson's r (Rr) were generated by ImageJ software. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, full-length PKCδ complexes with p23. COS-1 cells were transfected with either pEBG (empty vector) or pEBG-p23. Twenty-four h later, cells were infected with a PKCδ adenovirus (multiplicity of infection, 3 pfu/cell). After 24 h, GST or GST-p23 were precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads, and PKCδ was detected by Western blot using an anti-PKCδ antibody. Left panel, representative experiment. Right panel, densitometric analysis of three independent experiments, expressed as fold-change relative to GST. **, p < 0.01 versus GST. D, full-length PKCδ co-localizes with p23. HeLa cells were co-transfected with pEGFP-PKCδ and pcDNA3.1-V5-p23. After 48 h, cells were fixed and visualized by confocal microscopy. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments. Co-localization and Pearson's r (Rr) were generated by ImageJ software. Scale bar, 10 μm.

To further establish a role of the PKCδ C1b domain in the interaction with p23, we generated GFP-fused constructs encoding C1δab or isolated C1 domains from PKCδ (C1δa or C1δb) using the vector pEGFP. These plasmids were co-transfected into HeLa cells together with pcDNA3-V5-p23, a plasmid encoding V5-tagged p23, and localization determined by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1B, GFP-C1δab and GFP-C1δb co-localized with p23 in the perinuclear region, as judged by the yellow color observed in the overlapped images. On the other hand, GFP-C1δa was diffusely expressed in the cytoplasm and failed to co-localize with p23. Quantification of co-localization and Pearson's r (Rr) by ImageJ software confirmed these results.

Next, we investigated whether p23 associates with full-length PKCδ. COS-1 cells were transfected with pEBG control vector (which encodes GST alone) or pEBG-p23 (10) and subsequently infected with an adenovirus for full-length PKCδ (multiplicity of infection, 3 pfu/cell). After 24 h cells were subject to GST pulldown using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads. As shown in Fig. 1C, PKCδ was detected in complex with GST-p23 but not with GST, suggesting that PKCδ associates with p23 in cells. As a second approach, HeLa cells were transfected with GFP-PKCδ full-length together with pcDNA3-V5-p23. Fig. 1D shows that GFP-PKCδ co-localized with p23 as judged by the yellow color observed in the overlapped image as well as by quantification of co-localization and Pearson's r (Rr = 0.406) using ImageJ software.

Asp245 and Met266 in PKCδ C1b Are Critical for Interaction with p23

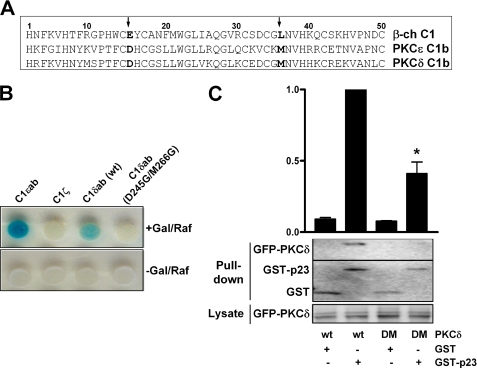

Schultz et al. (27) showed that Asp257 and Met278 in the PKCϵ C1b domain (amino acids 15 and 36 in the C1 motif, respectively) are implicated in the perinuclear localization of PKCϵ or its isolated C1b domain in neuroblastoma cells. Our previous study (14) showed that an acidic amino acid in position 15 and a hydrophobic amino acid in position 36 in the β2-chimaerin C1 domain were signatures for its association with p23. We speculated that similar positions in the PKCδ C1b domain (Asp245 and Met266, Fig. 2A) might be crucial for the interaction with p23. To test this hypothesis, we generated the double mutant C1δab (D245G/M266G) and inserted it into the pLexA vector for yeast two-hybrid analysis. pLexA-C1δab (WT) or pLexA-D245G/M266G-C1δab were co-transformed with pB42AD-p23 (HA-tagged, aa 108–208) into EGY48 yeast containing p8OP-LacZ vector, and the triple vectors co-transformants were selected by plating the yeast into SD/−Ura/−His/−Trp dropout plates. C1ϵab and C1ζ were used as positive and negative controls, respectively (14). As shown in Fig. 2B, only C1δab (WT) but not D245G/M266G-C1δab interacted with p23, as revealed by the induction of the LacZ reporter (blue).

FIGURE 2.

Asp245 and Met266 in the PKCδ C1b domain are required for the interaction with p23. A, alignment of C1 domains. B, EGY48 yeast (containing p8OP-LacZ vector) was co-transformed with pLexA-fused C1δab (WT), D245G/M266G-C1δab, C1ϵab (positive control), or C1ζ (negative control), together with pB42AD-HA-tagged p23 (aa 108–208). β-Galactosidase activity was determined after induction with galactosidase/raffinose (+Gal/Raf) (upper panel) or no induction (−Gal/Raf) (lower panel) 72 h after transformation. C, COS-1 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-PKCδ (WT) or GFP-D245G/M266G-PKCδ double mutant (DM) together with either pEBG-p23 or pEBG (empty vector). Twenty-four h later, GST or GST-p23 proteins were precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads, and associated GFP-PKCδ was detected by Western blot using an anti-GFP antibody. A densitometric analysis of three independent experiments is shown. *, p < 0.05 versus WT GFP-PKCδ.

Next, we examined whether mutations in positions 15 and 36 in the PKCδ C1b domain could alter the interaction with p23 in mammalian cells. COS-1 cells were co-transfected with pEBG or pEBG-p23 together with GFP-PKCδ (WT) or GFP-PKCδ (D245G/M266G) and subjected 24 h later to a GST pulldown assay using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads. As shown in Fig. 2C, the mutant D245G/M266G-GFP-PKCδ showed a reduced association with p23 compared with WT GFP-PKCδ. Altogether, these results established that Asp245 and Met266 in the PKCδ C1b domain are critical for the interaction with p23.

p23 Depletion Potentiates PKCδ-mediated Apoptosis in LNCaP Cells

To determine any potential functional implication of the PKCδ-p23 association, we turned to the LNCaP prostate cancer model. Previous studies from our laboratory established that phorbol esters such as PMA triggered an apoptotic response in LNCaP cells through PKCδ. Silencing PKCδ from LNCaP cells using RNAi essentially abolishes PMA-induced apoptosis in these cells (21–23).

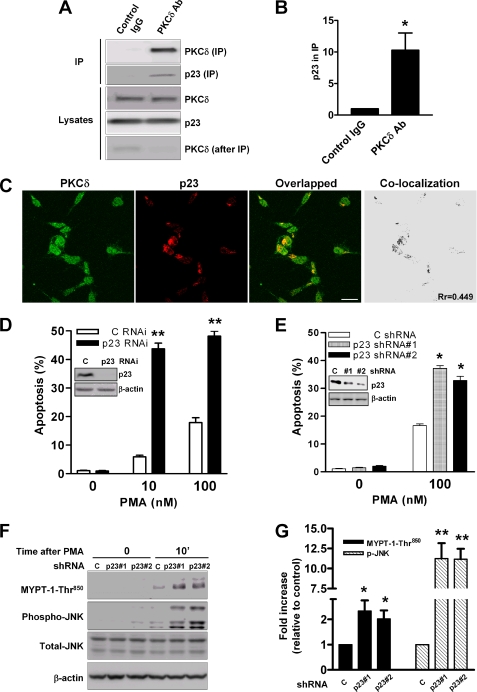

First, we wished to establish whether the interaction between PKCδ and p23 occurs in LNCaP cells. An anti-PKCδ antibody was used to immunoprecipitate “endogenous” PKCδ from LNCaP cells, and we examined whether endogenous p23 can be detected in the immunoprecipitate by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 3A and the corresponding densitometric analysis in Fig. 3B, p23 can be detected readily in immunoprecipitates using an anti-PKCδ antibody but not with control IgG. Furthermore, confocal microscopy revealed that endogenous p23 co-localizes with both endogenous PKCδ (Fig. 3C) or with pEGFP-PKCδ (supplemental Fig. S2) in the perinuclear region of LNCaP cells, as judged by the yellow color in the overlapped images as well as by quantification of co-localization and Pearson's r (Rr = 0.45) using ImageJ software (Fig. 3C). Thus, PKCδ interacts with p23 in LNCaP prostate cancer cells.

FIGURE 3.

p23 silencing from LNCaP cells potentiates PMA-induced apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. A, PKCδ and p23 form a complex in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. LNCaP cell extracts were incubated with either an anti-PKCδ antibody or control IgG (at 4 °C for 2 h). Immunoprecipitates (IP) were subject to Western blot analysis with an anti-p23 antibody. B, densitometric analysis of three individual experiments, expressed as fold-change relative to control IgG. *, p < 0.05 versus IgG. C, endogenous PKCδ co-localizes with p23 in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. LNCaP cells were fixed and stained with anti-PKCδ and anti-p23 primary antibodies, followed by a FITC-conjugated or a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody, respectively. Co-localization was examined by confocal microscopy. Experiments have been performed three times with similar results. Co-localization and Pearson's r (Rr) were generated by ImageJ software. Scale bar, 20 μm. D, LNCaP cells were transiently transfected with p23 or control (C) RNAi duplexes. After 48 h, cells were treated for 1 h with PMA or vehicle, and the incidence of apoptosis was determined 24 h later. Inset, expression of p23 as determined by Western blot. *, p < 0.01 versus control RNAi. E, LNCaP cells stably expressing different p23 shRNAs (1 or 2) or a control shRNA (C) were treated for 1 h with PMA or vehicle, and the incidence of apoptosis was determined 24 h later. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. Similar results were observed in two additional experiments. Inset, expression of p23 as determined by Western blot. *, p < 0.01 versus control shRNA. F, LNCaP cells with stable p23 depletion or control (C) cells were treated for 10 min with PMA (30 nm) or vehicle. Phospho-Thr850 MYPT1 and phospho-JNK were determined by Western blot. Two additional experiments yielded similar results. G, densitometric analysis of three separate experiments, expressed as fold-change relative to control shRNA. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control shRNA.

To determine a potential role of p23 in PKCδ-mediated apoptosis, we silenced p23 from LNCaP cells using RNAi. Transient delivery of a p23 dsRNA duplex into LNCaP cells reduced p23 expression by ∼90%. p23 RNAi depletion caused a remarkable potentiation of PMA-induced apoptosis in LNCaP cells. p23 depletion by itself did not cause any significant apoptosis (Fig. 3D). To further confirm this effect and also to minimize the chances of “off-target” effects of RNAi, we generated two LNCaP cell lines in which p23 was stably depleted using shRNA lentiviruses. Depletions of ∼58 and ∼80% were achieved using p23 shRNAs 1 and 2, respectively. In agreement with results observed using transient RNAi, a markedly higher PMA apoptotic response was observed in the p23 stable knockdown cell lines relative to control cells. In the absence of PMA treatment, no apoptosis could be observed (Fig. 3E). Thus, p23 negatively modulates PMA-induced apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells.

Our laboratory recently identified the RhoA/ROCK and JNK pathways as mediators of PMA-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. PMA activates ROCK and JNK in a PKCδ-dependent manner, and inhibition of either pathway impaired the apoptotic response of the phorbol ester (22). Notably, we found a significant potentiation of JNK activation by PMA in p23-depleted LNCaP cells compared with control cells, as determined using an anti-phospho-JNK antibody. Likewise, phosphorylation of the ROCK substrate myosin phosphatase target subunit 1 was markedly elevated in LNCaP subject to p23 depletion relative to control cells (Fig. 3F). Densitometric analyses of these Western blots are shown in Fig. 3G. Taken together, our data suggest that p23 depletion enhances PKCδ responses induced by PMA stimulation.

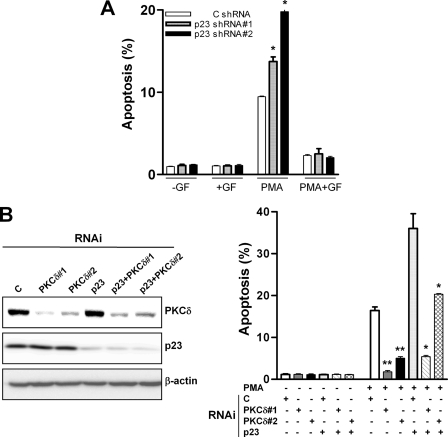

As PKCδ is the mediator of PMA-induced apoptosis in LNCaP cells (18, 20, 21), we speculated that the potentiating effect of p23 depletion on PMA-induced apoptosis should be mediated by PKCδ. To test this hypothesis, we first assessed the effect of the “pan” PKC inhibitor GF 109203X on PMA-induced apoptosis in p23 knockdown LNCaP prostate cancer cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, GF 109203X essentially abolished apoptosis induced by PMA in LNCaP cells subjected to either p23 or control RNAi. Moreover, silencing PKCδ in LNCaP cells subjected to either p23 or control RNAi impaired the death response of PMA. The inhibitory effect was proportional to the level of PKCδ depletion achieved because the PMA apoptotic effect was negligible in LNCaP cells transiently transfected with the PKCδ dsRNA1, which reduced PKCδ expression by ∼82%, but it was partial in LNCaP cells transfected with PKCδ dsRNA2, which only reduced PKCδ expression by ∼69% (Fig. 4B). Altogether, these results suggest that the potentiating effect of p23 depletion on PMA-induced apoptosis is mediated through PKCδ.

FIGURE 4.

The potentiation of PMA-induced apoptosis by p23 RNA depletion is mediated by PKCδ. A, LNCaP cells expressing p23 shRNA were treated with 30 nm PMA for 1 h either in the presence of absence of the PKC inhibitor GF 109203X (5 μm), which was added 1 h before and during PMA treatment. Apoptosis was assessed 24 h later. *, p < 0.05 versus control. B, LNCaP cells were transiently transfected with different RNAi duplexes, as indicated in the figure. Forty-eight h later, cells were treated for 1 h with 30 nm PMA (+PMA) or vehicle (−PMA), and apoptosis was assessed 24 h later (right panel). Expression of PKCδ and p23 was determined by Western blot (left panel). Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control (C) RNAi. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments.

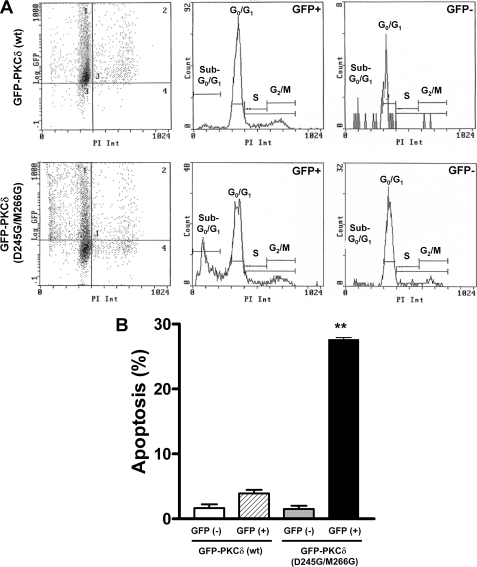

Asp245/Met266-PKCδ Mutant Induces Apoptosis in LNCaP Cells

One attractive possibility is that p23 serves as an anchoring protein for PKCδ in LNCaP cells. p23 may limit PKCδ effects by sequestering the kinase to the perinuclear region of the cell. A similar scenario was described in our previous studies for the Rac-GAP β2-chimaerin (10, 14). To begin addressing this possibility, we used the double mutant D245G/M266G-PKCδ, which is unable to bind to p23 (see Fig. 2B). LNCaP cells were transfected with plasmids encoding either GFP-fused WT-PKCδ or D245G/M266G-PKCδ. Seventy-two h after transfection, the “green” and the “non-green” cell populations were subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Interestingly, we observed a significant population of LNCaP cells expressing the double mutant GFP-D245G/M266G-PKCδ in sub-G0/G1 (28%), characteristic of apoptosis, which was very low in cells expressing WT GFP-PKCδ (∼3% apoptosis). The percentage of cells in sub-G0/G1 in the “non-transfected” population was negligible (∼1%) (Fig. 5). Thus, loss of binding to p23 enhances PKCδ-mediated apoptosis.

FIGURE 5.

A PKCδ mutant unable to bind to p23 (D245G/M266G-PKCδ) induces apoptosis in LNCaP cells. LNCaP cells were transfected with plasmids encoding either GFP-PKCδ (WT) or GFP-D245G/M266G-PKCδ. After 48 h, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol and stained with propidium iodide (1 mg/ml). The sub-G0/G1 population was analyzed in both green (transfected) and non-green (non-transfected) cells using flow cytometry. For each treatment, ∼7,500 events were recorded. A, representative flow cytometry chart. B, percentage of cells in sub-G0/G1 (apoptosis). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. **, p < 0.01 versus GFP (+) GFP-PKCδ (WT). Similar results were observed in three independent experiments.

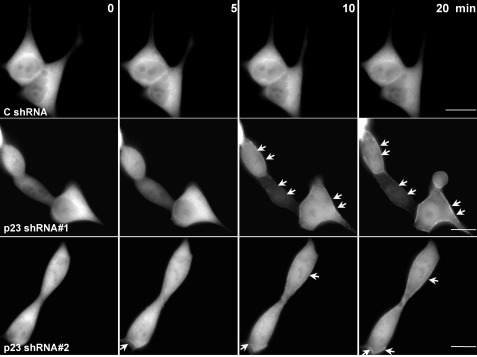

Silencing p23 Leads to Enhanced Translocation of PKCδ to Plasma Membrane

In a recent study, we determined that the plasma membrane pool of PKCδ was responsible for conferring the apoptotic effect of PMA (23). We decided to examine whether p23 influences PKCδ translocation to the plasma membrane. We speculated that PKCδ peripheral translocation is enhanced by depletion of p23. p23-depleted and control LNCaP cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP-PKCδ (WT) and treated with PMA. PKCδ localization was monitored by time-lapse video microscopy. Using high concentrations of PMA (100–300 nm), translocation of GFP-PKCδ could be observed readily in LNCaP cells, and therefore, under these experimental conditions, it was very hard to pursue a comparative study between control and p23-depleted cells, although translocation of PKCδ was detected at earlier time points in LNCaP cells subjected to p23 RNAi (data not shown). Therefore, to detect a potential enhancement of PKCδ translocation by p23 depletion, we used a lower PMA concentration. At 30 nm PMA, PKCδ translocation in control LNCaP cells was barely visible. On the other hand, plasma membrane translocation of GFP-PKCδ was detected readily in p23-depleted LNCaP cell lines 5–10 min after PMA treatment under the same experimental condition (Fig. 6). These results support the concept that the association of PKCδ to p23 is an important regulatory mechanism for controlling PKCδ activation.

FIGURE 6.

Depletion of p23 enhances PKCδ translocation to the cell periphery. LNCaP cells subjected to stable p23 RNAi depletion or control (C) and expressing GFP-PKCδ were treated with 30 nm PMA for different times. Time-lapse images of GFP-PKCδ translocation in living cells were captured at different times after PMA treatment. The peripheral translocation is marked with arrows. Similar results were observed in two additional experiments. Scale bar, 10 μm.

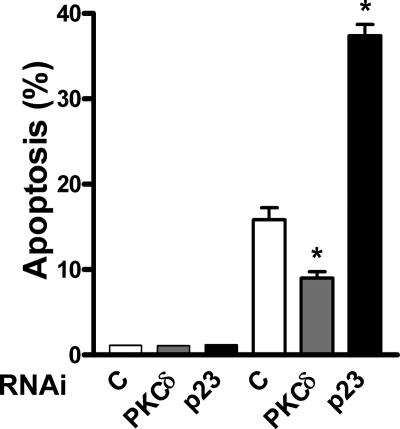

p23 Regulates Apoptosis Induced by Doxorubicin

PKCδ not only mediates the apoptotic effect of phorbol esters but also death triggered by a number of stimuli, including ceramide and DNA-damaging agents (25, 26, 28). To examine whether the effect of p23 depletion on LNCaP cell apoptosis is not only restricted to PMA, we analyzed the response of the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin. As shown in Fig. 7, depletion of PKCδ reduced by ∼50% doxorubicin-induced LNCaP cell apoptosis, arguing for the involvement of PKCδ in this effect. Notably, the number of apoptotic cells observed in response to doxorubicin treatment was essentially doubled in p23-depleted LNCaP cells. This result reinforces the concept that p23 is a negative modulator of PKCδ-mediated apoptosis.

FIGURE 7.

p23 negatively regulates doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in LNCaP cells. LNCaP cells were transiently transfected with p23, PKCδ, or control (C) RNAi duplexes. After 48 h, cells were treated with doxorubicin (1 μg/ml for 2 h), and the incidence of apoptosis determined 24 h later. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. *, p < 0.05 versus control. Similar results were observed in two additional experiments.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report that the perinuclear protein p23, also known as Tmp21, interacts with PKCδ, a member of the serine-threonine kinase PKC family. This interaction is mediated by the second C1 domain (C1b) of PKCδ. C1 domains originally have been characterized as lipid-binding motifs that drive the relocalization of PKC isozymes, chimaerins, and other signaling molecules to membranes via binding to the second messenger DAG and phospholipids (11, 12, 29–31). Association with membranes represents a key step in the allosteric activation of PKCs by lipids. At a structural level, the C1 domains are remarkably similar, although only a subset of C1 domains has the ability to bind DAG and DAG mimetics such as the phorbol esters (32–34). Regardless of their resemblance, a distinctive property of C1 domains is their ability to localize to different intracellular compartments when expressed in cells. Isolated C1a domains of PKC isozymes are generally located diffusely when expressed in mammalian cells, whereas isolated C1b domains preferentially localize at the perinuclear region (14, 35, 36). The single C1 domain present in chimaerins and Ras-GRPs also show a characteristic localization in the perinucleus (10, 13, 14, 37–39). Although the distinctive localization of individual C1 domains may relate to unique interactions with membrane lipids, there is growing evidence for a potential involvement of accessory proteins in C1 domain targeting. For example, the C1b domain of PKCα interacts with fascin to drive cell motility (40), the C1b domain in PKCϵ binds to peripherin and induces its aggregation in cells (41), and the C1b domain of PKCγ associates with 14-3-3ϵ (42). C1a domains from PKCs also interact with proteins, including pericentrin (43) and an E3 ubiquitin ligase (44). Thus, protein interactions through C1 domains may contribute to the differential compartmentalization of PKC isozymes.

Previous reports from our laboratory identified p23 as an interacting protein for C1 domains. In an early study (10), we found that the C1 domain in α- and β- chimaerins associates with p23 in the perinuclear region. Deletion of the C1 domain from β2-chimaerin abolished this interaction, and p23 RNAi depletion prevented β2-chimaerin relocalization in response to stimuli (10, 14). The present study clearly shows that the C1 domain region in PKCδ associates with p23. The C1 domain region of PKCϵ also interacts with p23, and this perinuclear association is lost upon activation of PKCϵ (14). Larsen and co-workers (27) originally postulated that an acidic amino acid in position 15 and a hydrophobic amino acid in position 36 in the C1 domain consensus were key determinants for perinuclear targeting. Our studies strongly support this notion. Indeed, mutations in positions Asp257 and Met278 in PKCϵ (14) or in positions Asp245 and Met266 in PKCδ (this study) greatly reduces association with p23. Mutation of equivalent residues in β2-chimaerin C1 domain (Glu227 and Leu248) also affects its perinuclear targeting via p23. From structural data, it can be inferred that residues in positions 15 and 36 in C1b domains are not inserted into the membrane bilayer, and therefore, they should be accessible for interacting with other partners (27). C1a domains in PKCδ and PKCϵ do not fulfill the requirements for binding to p23 (27). Altogether, our studies strongly support a role for p23 in targeting proteins with C1 domains to the perinucleus and argue for an exquisite selectivity for these interactions.

It is quite striking that silencing p23 expression has a significant impact on responses mediated by PKCδ. Evidence from several laboratories established that PKCδ inhibits cell proliferation or kills cells upon activation through an apoptotic mechanism. Previous studies from our laboratory established that PKCδ mediates apoptosis induced by phorbol esters or chemotherapeutic drugs in prostate cancer cells such as the LNCaP model (18, 24). The ability of PMA to confer an apoptotic response in LNCaP cells depends on the relocalization of PKCδ to the plasma membrane. This step seems to be essential to promote the release of factors required for the killing effect of the phorbol ester (18, 21, 23, 24). Bryostatin 1, a C1 domain ligand that is unable to translocate PKCδ to the plasma membrane but still translocates PKCα and PKCϵ to the cell periphery, fails to provoke an apoptotic response in LNCaP cells. In addition, preventing the access of PKCδ to the plasma membrane impairs the apoptotic effect of PMA. Moreover, expression of a myristoylated, targeted PKCδ, which specifically localizes at the plasma membrane, is sufficient to trigger apoptosis in LNCaP cells (23). We hypothesize that perinuclear anchoring of PKCδ through p23 serves as a mechanism that restricts the availability of this kinase, therefore limiting the pool available for accessing the plasma membrane. In support of this concept, an early study established that the magnitude of the PMA apoptotic response in LNCaP cells is proportional to the amount of PKCδ expressed in the cells, as PKCδ overexpression markedly potentiates apoptosis, and reduction in PKCδ cellular levels diminishes the apoptotic effect of the phorbol ester (18, 21, 23). One would expect that silencing p23, which does not change total levels of cellular PKCδ, would lead to elevated PKCδ available for plasma membrane translocation. A similar scenario may be possible for the apoptotic effect of chemotherapeutic drugs, with the difference that in this case, the effect depends on the nuclear translocation of PKCδ (25). Consistent with this notion, we found that translocation of PKCδ to the periphery of LNCaP cells is more pronounced when p23 has been silenced. A similar paradigm has been described previously for β2-chimaerin. In this later case, depletion of p23 leads to enhanced peripheral translocation of this Rac-GAP, elevated Rac-GAP activity, and reduced cellular Rac-GTP levels (14). What becomes obvious from all of these studies is that different intracellular pools exist for PKCδ and possibly for other DAG/phorbol ester receptors and that the “activatable” pool of the kinase may be limited by its association with anchoring proteins.

Our studies also highlight the diversity of functions regulated by p23. This member of the p24 family has been implicated in the retention and retrieval of cargo proteins in the secretory pathway. Additional roles have been assigned to p23, including recruiting the small GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor 1 to the Golgi, assembling actin in the Golgi, and regulating γ-secretase activity (7, 9). Our studies argue that p23 plays additional roles as a modulator of vital signaling pathways through its association with C1 domain-containing proteins. It remains to be determined whether perinuclear PKCδ plays any significant functional role. Conceivably, p23 may facilitate the access of PKCδ to perinuclear substrates and effectors. Indeed, PKCδ (but not PKCα) regulates endosome-to-Golgi transport (46). PKCδ translocates to the Golgi in a C1b-dependent manner (47–49), and Golgi proteins have been established as PKC substrates (46, 48). PKCδ also has been implicated in endoplasmic reticulum stress (50, 51). PKCδ becomes associated to a Golgi compartment in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, suggesting a role for perinuclear PKCδ in the phosphorylation of mitotic kinases and growth arrest (52–54). Interestingly, perinuclear targeting of PKCδ prevents apoptosis (23, 45), which is consistent with the proapoptotic role of this kinase only when it is disassociated from p23.

In summary, our results identified p23 as an anchoring protein for PKCδ. This association occurs via the C1b domain in PKCδ and influences the availability of the kinase to trigger cellular responses, strongly supporting the concept that this domain plays a key role in driving the perinuclear localization of signaling proteins. Our studies also highlight the concept that C1 domains do not act only as lipid-binding motifs, a role for which they have been known for many years, but also play important roles in protein-protein interactions.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1-CA89202 from (to M. G. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- GAP

- GTPase-activating protein

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- aa

- amino acids

- ROCK

- Rho-associated protein kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Strating J. R., Martens G. J. (2009) Biol. Cell 101, 495–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stamnes M. A., Craighead M. W., Hoe M. H., Lampen N., Geromanos S., Tempst P., Rothman J. E. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8011–8015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sohn K., Orci L., Ravazzola M., Amherdt M., Bremser M., Lottspeich F., Fiedler K., Helms J. B., Wieland F. T. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 135, 1239–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rojo M., Emery G., Marjomäki V., McDowall A. W., Parton R. G., Gruenberg J. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 1043–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rojo M., Pepperkok R., Emery G., Kellner R., Stang E., Parton R. G., Gruenberg J. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139, 1119–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao L., Helms J. B., Brunner J., Wieland F. T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14198–14203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Majoul I., Straub M., Hell S. W., Duden R., Söling H. D. (2001) Dev. Cell 1, 139–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fucini R. V., Chen J. L., Sharma C., Kessels M. M., Stamnes M. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 621–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen F., Hasegawa H., Schmitt-Ulms G., Kawarai T., Bohm C., Katayama T., Gu Y., Sanjo N., Glista M., Rogaeva E., Wakutani Y., Pardossi-Piquard R., Ruan X., Tandon A., Checler F., Marambaud P., Hansen K., Westaway D., St George-Hyslop P., Fraser P. (2006) Nature 440, 1208–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang H., Kazanietz M. G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4541–4550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colón-González F., Leskow F. C., Kazanietz M. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35247–35257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang H., Kazanietz M. G. (2006) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 855–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caloca M. J., Wang H., Delemos A., Wang S., Kazanietz M. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18303–18312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang H., Kazanietz M. G. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1398–1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Griner E. M., Kazanietz M. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 281–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blass M., Kronfeld I., Kazimirsky G., Blumberg P. M., Brodie C. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 182–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Santiago-Walker A. E., Fikaris A. J., Kao G. D., Brown E. J., Kazanietz M. G., Meinkoth J. L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32107–32114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fujii T., García-Bermejo M. L., Bernabó J. L., Caamaño J., Ohba M., Kuroki T., Li L., Yuspa S. H., Kazanietz M. G. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7574–7582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka Y., Gavrielides M. V., Mitsuuchi Y., Fujii T., Kazanietz M. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33753–33762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gavrielides M. V., Gonzalez-Guerrico A. M., Riobo N. A., Kazanietz M. G. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 11792–11801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gonzalez-Guerrico A. M., Kazanietz M. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38982–38991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xiao L., Eto M., Kazanietz M. G. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29365–29375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Burstin V. A., Xiao L., Kazanietz M. G. (2010) Mol. Pharmacol. 78, 325–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caino M. C., von Burstin V. A., Lopez-Haber C., Kazanietz M. G. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 386, 11254–11264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DeVries T. A., Neville M. C., Reyland M. E. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 6050–6060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Panaretakis T., Laane E., Pokrovskaja K., Björklund A. C., Moustakas A., Zhivotovsky B., Heyman M., Shoshan M. C., Grandér D. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3821–3831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schultz A., Ling M., Larsson C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 31750–31760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sumitomo M., Ohba M., Asakuma J., Asano T., Kuroki T., Asano T., Hayakawa M. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 109, 827–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Csukai M., Mochly-Rosen D. (1999) Pharmacol. Res. 39, 253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Newton A. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28495–28498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang H., Yang C., Leskow F. C., Sun J., Canagarajah B., Hurley J. H., Kazanietz M. G. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 2062–2074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blumberg P. M., Kedei N., Lewin N. E., Yang D., Czifra G., Pu Y., Peach M. L., Marquez V. E. (2008) Curr. Drug Targets 9, 641–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Colón-González F., Kazanietz M. G. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 827–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pu Y., Peach M. L., Garfield S. H., Wincovitch S., Marquez V. E., Blumberg P. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33773–33788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carrasco S., Merida I. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2932–2942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schultz A., Jönsson J. I., Larsson C. (2003) Cell Death Differ 10, 662–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Caloca M. J., Fernandez N., Lewin N. E., Ching D., Modali R., Blumberg P. M., Kazanietz M. G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26488–26496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Caloca M. J., Garcia-Bermejo M. L., Blumberg P. M., Lewin N. E., Kremmer E., Mischak H., Wang S., Nacro K., Bienfait B., Marquez V. E., Kazanietz M. G. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11854–11859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caloca M. J., Zugaza J. L., Bustelo X. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33465–33473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Anilkumar N., Parsons M., Monk R., Ng T., Adams J. C. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 5390–5402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sunesson L., Hellman U., Larsson C. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16653–16664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nguyen T. A., Takemoto L. J., Takemoto D. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52714–52725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen D., Purohit A., Halilovic E., Doxsey S. J., Newton A. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4829–4839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen D., Gould C., Garza R., Gao T., Hampton R. Y., Newton A. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33776–33787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gomel R., Xiang C., Finniss S., Lee H. K., Lu W., Okhrimenko H., Brodie C. (2007) Mol. Cancer Res. 5, 627–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Torgersen M. L., Wälchli S., Grimmer S., Skånland S. S., Sandvig K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16317–16328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bögi K., Lorenzo P. S., Szállási Z., Acs P., Wagner G. S., Blumberg P. M. (1998) Cancer Res. 58, 1423–1428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kajimoto T., Shirai Y., Sakai N., Yamamoto T., Matsuzaki H., Kikkawa U., Saito N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12668–12676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang Q. J., Bhattacharyya D., Garfield S., Nacro K., Marquez V. E., Blumberg P. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37233–37239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lim J. H., Park J. W., Choi K. S., Park Y. B., Kwon T. K. (2009) Carcinogenesis 30, 729–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Qi X., Mochly-Rosen D. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 804–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. LaGory E. L., Sitailo L. A., Denning M. F. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 1879–1887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perego C., Porro D., La Porta C. A. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294, 127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Watanabe T., Ono Y., Taniyama Y., Hazama K., Igarashi K., Ogita K., Kikkawa U., Nishizuka Y. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 10159–10163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Deleted in proof.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.