Abstract

Leukotriene (LT) C4 and its metabolites, LTD4 and LTE4, are involved in the pathobiology of bronchial asthma. LTC4 synthase is the nuclear membrane-embedded enzyme responsible for LTC4 biosynthesis, catalyzing the conjugation of two substrates that have considerably different water solubility; that amphipathic LTA4 as a derivative of arachidonic acid and a water-soluble glutathione (GSH). A previous crystal structure revealed important details of GSH binding and implied a GSH activating function for Arg-104. In addition, Arg-31 was also proposed to participate in the catalysis based on the putative LTA4 binding model. In this study enzymatic assay with mutant enzymes demonstrates that Arg-104 is required for the binding and activation of GSH and that Arg-31 is needed for catalysis probably by activating the epoxide group of LTA4.

Keywords: Crystal Structure, Eicosanoid-specific Enzymes, Enzyme Mechanisms, Enzyme Structure, Membrane Proteins, LTC4S, Leukotriene C4 Synthase

Introduction

Leukotriene C4 (LTC4)4 and its metabolites, LTD4 and LTE4, are collectively called the cysteinyl leukotrienes (cys-LTs). They are generated by certain bone marrow-derived proinflammatory cells, such as mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, and monocyte-derived tissue cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells (1–5). They have been implicated in the pathobiology of human bronchial asthma for their direct effect as bronchoconstrictors (6, 7) and permeability-enhancing mediators (8, 9), their presence in urine and bronchoalveolar fluid during exacerbations (10, 11), and the clinical efficacy of therapeutic agents interfering with the biosynthesis or receptor-mediated action of the cys-LTs (12, 13). Therapeutic intervention has also been shown to be effective in allergic rhinitis, acute and chronic urticaria, and angioedema (14–16), indicating a critical role for the cys-LTs in a broad range of allergic diseases.

The biosynthetic pathway of the cys-LTs begins with cytosolic phospholipase A2-dependent release of arachidonic acid from the outer nuclear membrane (17) and its subsequent metabolism to 5-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid and then LTA4 by 5-lipoxygenase in the presence of the 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (18–20). LTA4 is then conjugated with reduced glutathione (GSH) to form LTC4 by means of LTC4 synthase (LTC4S) (21). Both 5-lipoxygenase activating protein and LTC4S are integral membrane proteins of the nuclear membrane and belong to the membrane-associated proteins in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism superfamily (22, 23). Intracellular LTC4 is released by the multidrug resistance protein-mediated, energy-dependent pathway. It undergoes extracellular metabolism to LTD4 by the cleavage of glutamic acid via γ-glutamyl transpeptidase or γ-glutamyl leukotrienase and then to LTE4 by removal of glycine by dipeptidases (24, 25). The three sequentially generated cys-LTs differ in extracellular stability such that only LTE4 is readily detected in urine or at a site of inflammation (26, 27). They are also distinct in their affinity for the cloned receptors CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors (28, 29). Studies of mice with targeted disruption of LTC4S have extended the appreciation of the role of cys-LTs in models of inflammation beyond their smooth muscle activity. LTC4S−/− mice have a marked reduction in antigen-induced allergic pulmonary inflammation and in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (30, 31).

An adenosine diphosphate-reactive purinergic (P2Y12) receptor was recently reported to be required for LTE4-dependent pulmonary inflammation (32, 33). In addition, a functional receptor for LTE4-mediated vascular permeability was observed in mice lacking both the classical CysLT1 and CysLT2 receptors (34). An LTE4-reactive receptor has been considered likely because LTE4 has pathophysiological effects on airway inflammation in asthma, such as mucosal eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness, although LTE4 has a much lower affinity for the established cys-LT receptors.

The previous crystal structure study provided a detailed view of the GSH binding of LTC4S (35, 36). The GSH binding site is formed at the interface of two adjacent monomers in the LTC4S trimer. Nine amino acid residues interact directly with the bound GSH, and almost all of these amino acid residues are conserved in the amino acid sequence alignment in the membrane-associated proteins in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism family. Tyr-93 and Arg-51, which had been proposed to be responsible for this catalysis based on the previous site-directed mutagenesis analysis (37), were included in the nine amino acid residues for GSH binding. Arg-104 is the only amino acid residue interacting with the thiol group and has been proposed to activate the thiol group of GSH (Fig. 1).

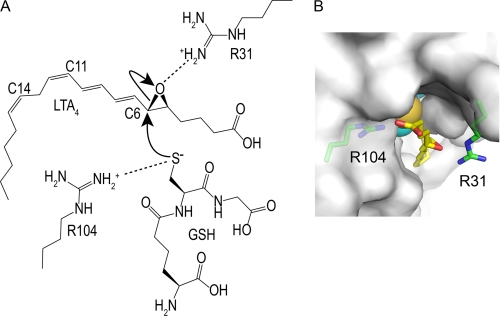

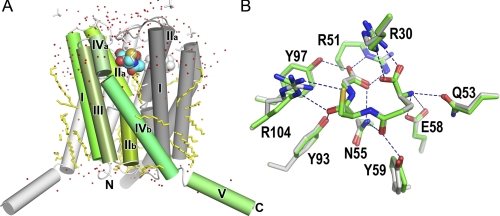

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the proposed catalytic mechanism. A, the catalytic mechanism for LTC4 biosynthesis catalyzed by Arg-31 and Arg-104 was proposed from the crystal structure of LTC4S and the putative LTA4 binding model (35). In panel B the surface of the LTC4S trimer is in white. The side chain of Arg-31 was flexible in the crystal structure of this work, so the side chain of Arg-31 with the most common conformation in the crystal structure is presented as a plausible model (55). The buried GSH molecule is shown by the CPK (Corey Pauling Koltun) model. The epoxide group comes to the space between the Arg-31 and Arg-104. The space is the only place where the epoxide group can interact with the thiol group, because the thiol group of GSH is buried inside of the trimer. The epoxide group can bind in a productive manner there in which the epoxy carbon comes to the proximity of the thiol group and the epoxy oxygen resides at the opposite side of the thiol group, although the binding mode of LTA4 remains to be confirmed experimentally. The positively charged Arg-31 increases the electrophilicity of the C6 of LTA4 by forming a hydrogen bond with the epoxide oxygen, and the positively charged Arg-31 stabilizes the negatively charged alkoxide group, which forms from the epoxide group concomitantly with the propagation of the catalysis. Through the direct interaction between the guanidino side chain of Arg-104 and the thiol group of GSH, the Arg-104 decreases the pKa of the thiol group to the level where the thiol group becomes the activated species as a thiolate anion at physiological pH. Then, the resultant thiolate anion attacks the electrophilic C6 of LTA4.

The details on the catalytic activity of LTC4 biosynthesis by LTC4S remain to be determined. Based on the previous x-ray crystal structure of the LTC4S-GSH complex, how GSH is bound and activated was proposed. However, the amino acid residue(s) that is directly involved in the catalysis of LTA4 was elusive without LTA4 complex structure. We hypothesized that there is a certain amino acid residue forming a hydrogen bond with the epoxide oxygen of LTA4, because protonation of the epoxide group of LTA4 has a powerful impact on the reactivity of LTA4. The epoxide group of LTA4 is hydrolyzed readily in acidic solution, whereas it is less reactive in basic solution (38). In fact, to prepare LTA4 from LTA4 methyl ester (LTA4-Me), the hydrolysis of the methyl group of LTA4-Me proceeds without ring opening of the epoxide group in a basic solution, such as 0.25 m NaOH/acetone, as shown in the product insert from the supplier (Cayman Chemical) and the previous literature (39).

We have proposed that the Arg-31 is the amino acid residue interacting with the epoxide oxygen based on the putative LTA4 binding model (Fig. 1) (35). LTA4 binding models based on the binding of the hydrocarbon tail of dodecyl maltoside in the hydrophobic part of the active site have been proposed (35, 36). The proposed position of the epoxide group is a plausible position for the catalysis, although the proposed binding mode of LTA4 is still controversial due to a lack of the structural complex for LTC4S and LTA4. Nevertheless, the proposed LTA4 binding mode is consistent with the 5S-hydroxyl-6R-glutathionyl product stereochemistry by the SN2 nucleophilic substitution, where the C6 carbon as the electrophile faces the thiol group of GSH at the narrow path and the leaving epoxy oxygen at the other side of C6. In such a case, Arg-31, the side chain reaches the epoxide group in the putative LTA4 model, suggesting a catalytic role for Arg-31 in the reactivity of LTA4. Arg-31 was proposed to make the epoxide group reactive by forming a hydrogen bond with the epoxide oxygen in the carrying out of the catalytic mechanism. An enzymatic assay is needed to confirm the putative functions of these arginine residues suggested by the crystal structure.

Based on the enzyme assay performed on the wild-type (WT) and mutant LTC4S, here we report that the two arginine residues Arg-31 and Arg-104 are the catalytic amino acid residues specific for LTA4 and GSH, respectively. The decreased kcat/Km of the mutant LTC4S missing Arg-31 or Arg-104 showed that the arginine residues closely participate in the catalysis. A comparison of the pH dependence of kcat and Km between WT LTC4S and these mutants showed that Arg-31 has the LTA4 activating, but not binding function of LTA4, and Arg-104 plays a role in both the activating and binding of GSH.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Plasmids for the mutants of human LTC4S in which alanine replaced Arg-31 (R31A) or Arg-104 (R104A), respectively, were prepared using a QuikChange mutagenesis XLII kit (Stratagene). A QuikChange lightning mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used for preparation of the expression plasmids in which alanine replaced Arg-90 (R90A), Arg-92 (R92A), Arg-99 (R99A), or Arg-113 (R113A) or glutamine replaced Arg-31 (R31Q), Arg-90 (R90Q), Arg-92 (R92Q), Arg-99 (R99Q), Arg-104 (R104Q), or Arg-113 (R113Q) or glutamic acid replaced Arg-31 (R31E) or leucine replaced Arg-31 (R31L). The template was the pESP-3 expression vector (Stratagene) carrying human LTC4S with a His6 tag at its C terminus (35, 40). The primers for the mutation works are shown in supplemental Table S1.

Protein Expression and Purification

The resultant plasmids of each mutant as well as the plasmid for WT LTC4S were introduced into Schizosaccharomyces pombe h− leu1-32 using the lithium acetate method (41), and stable clones were established. Expression of WT and mutant LTC4S were induced by the depletion of thiamine in the culture media, as the promoter of the plasmid is highly activated by the depletion of thiamine.

The proteins for the enzyme assay were purified as described (35) with an omission of the last PD-10 desalting step. Thus, LTC4S was eluted from a Superose-12 column equilibrated with a solution of 20 mm MES-NaOH (pH 6.5), 0.1 m NaCl, 0.04% (w/v) dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM), 1 mm DTT, 10%(v/v) glycerol, and 5 mm GSH and was concentrated to ∼5 mg/ml and then stored at −80 °C. Concentrations of the purified enzymes were determined based on UV absorption at 280 nm and the milligram extinction coefficients, 1.57 mg−1·cm−1. The purified samples were confirmed to be a single band using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

The recombinant enzymes for the crystallographic work were additionally applied to a PD-10 column equilibrated with a solution of 20 mm MES-NaOH (pH 6.5), 0.04%(w/v) DDM, and 5 mm GSH. The recombinant enzymes eluted from the PD-10 column were concentrated to 6.0 mg/ml for WT LTC4S, 5.4 mg/ml for the R31A mutant, and 2.9 mg/ml for the R104A mutant.

Crystallography

The crystals of WT LTC4S and the R31A mutant were grown at 20 °C from a mother solution composed of equal amounts of the enzyme solution and the reservoir solution containing 0.1 m MES-NaOH (pH 6.5), 1.6 m ammonium sulfate, and 0.8 m magnesium chloride. The crystals of WT LTC4S were transferred into the harvest solution of 0.1 m MES-NaOH (pH 6.5), 2.4 m ammonium sulfate, and 45 mm GSH. The crystals were dipped into the harvest solution supplemented with 15%(v/v) ethylene glycol before the x-ray diffraction experiment at a cryogenic temperature using BL26B2/SPring-8 (42). The statistical data for the diffraction data are shown in Table 1.

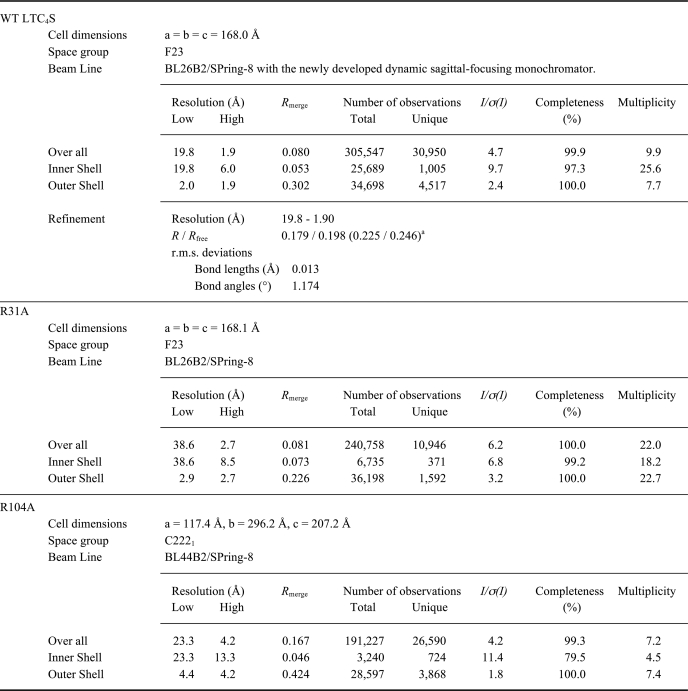

TABLE 1.

Statistics of diffraction data

a The numbers in the parentheses are R and Rfree at the high resolution shell (1.95-1.90Å).

The crystals of the R104A mutant were grown under conditions that were virtually the same as in the previous case (35). The R104A mutant was mixed with the reservoir solution (28% (v/v) PEG400, 0.1 m MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.0)) in equal amounts and incubated at 4 °C for 2 weeks. The crystals grown were frozen at a cryogenic temperature, and diffraction images were taken with a BL44B2/SPring-8 (43).

The structural comparison between the WT LTC4S and the mutants of R31A and R104A was performed by the difference Fourier method to assess whether the three-dimensional structure of LTC4S suffered damage from the point mutations. The Fourier coefficients and phases were FR31A(F23) − FWT(F23), φWT(F23) or FR104A(C2221) − FWT(C2221), φWT(C2221), and FR31A(F23) and FR104A(C2221) are structure factors of the R31A and R104A mutant crystals with the space group F23 and C2221, respectively. FWT(F23) is structure factor of the WT LTC4S crystal in this work, and φWT(F23) is the phase calculated from the refined structure of WT LTC4S. FWT(C2221) is structure factor of the WT LTC4S crystal used in the previous study (PDB ID 2PNO), and φWT(C2221) is the phase calculated from the coordinate of WT LTC4S (PDB ID 2PNO) (35). The computer programs employed were MOSFLM, SCALA, and TRUNCATE for the processing of diffraction images, AMORE and MOLREP for molecular replacement, REFMAC5 and COOT for the structural refinement (44), and PyMOL for the structural inspection and preparation of figures for structural representation.

Far Ultraviolet Circular Dichroic Analysis

Far ultraviolet circular dichroic (CD) spectra of WT LTC4S and the R31A and R104A mutants at 4.0 °C were measured with a J-715 spectropolarimeter (Jasco). The purified enzymes were applied to a PD-10 column equilibrated with a solution of 2.5 mm MES-NaOH (pH 6.5), 0.04% (w/v) DDM.

Relative Enzyme Activities of Arginine Mutants in Comparison to the WT LTC4S

The effects of point mutation on one of arginine residues around the entrance of GSH binding site were assessed by the determination of the relative activity of the Arg mutants in comparison with that of WT LTC4S. The conditions for this enzyme assay were 20 ng of enzyme in 200 μl of the solution (10 mm GSH, 21.2 μm LTA4-Me, or 20.0 μm LTA4, 50 mm BisTris propane (pH 7.0), 10 mm MgCl2, 0.015% DDM) at room temperature and an incubation time of 2 min. To terminate the enzyme reaction, 608 μl of a solvent of methanol:acetic acid (75:1 by volume) containing prostaglandin B2 (PGB2) as the internal standard for reverse phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) assay was added. One hundred μl of the final 808-μl solution was applied to the RP-HPLC analysis. The assays for each condition were repeated at least three times.

The LTA4-Me purchased from Cayman Chemical was dried under N2 stream and then solved by ethanol with 3%(v/v) triethylamine, and the ethanol solution was used for the assay. LTA4 was prepared from LTA4-Me by the method described in the product insert (Cayman Chemical). The concentrations of LTA4-Me or LTA4 were determined by UV absorbance at 280 nm (the molar extinction coefficients (ϵ) = 49,000, as shown in the product insert).

Determination of Kinetic Parameters

To determine the kinetic parameters of WT LTC4S and the R31A and R104A mutants, the enzyme activities were measured with varying concentrations of GSH at pH 7.0, 8.0, and 9.0 at room temperature. Enzyme catalysis was started by the addition of 2 μl of LTA4-Me (1.9–2.0 mm) to 198 μl of solution containing 50 mm BisTris propane (pH 7.0, 8.0, 9.0), 10 mm MgCl2, 9.85–0.05 mm GSH for WT LTC4S, 3.11–0.05 mm GSH for R31A, 49.1–0.05 mm GSH for R104A, 0.015% (w/v) DDM, and the enzyme. The enzyme amounts and reaction times were optimized to detect LTC4-Me by RP-HPLC; WT, 20 ng of enzyme and 1 min reaction; R31A, 600 ng and 10 min; R104A, 200 ng and 8 min. The enzyme assay was terminated as described above.

Assays with varying concentrations of LTA4-Me were also performed for WT LTC4S and the R31A and R104A mutants. The reactions were initiated by a 2-μl aliquot of LTA4-Me to 198 μl of solution of 50 mm BisTris propane (pH 7.0, 8.0, 9.0), 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm GSH, 0.015% (w/v) DDM, and an appropriate amount of enzyme (WT LTC4S, 20 ng; R31A and R104A mutants, 600 ng). The final concentrations of LTA4-Me were 21.2–0.5 μm for WT LTC4S and 10.6–1.1 μm for the R31A and R104A mutants. The reaction times for WT LTC4S and the R31A and R104A mutants were 2, 8, and 8 min, respectively. The enzyme assays was terminated as described above. The enzyme assay using LTA4 was performed to clarify whether the terminal carboxyl group of LTA4, which is esterified to be a methyl ester in LTA4-Me, exerted an affect on the specificity constant.

The specificity constants (kcat/Km) of the WT LTC4S at pH 7.0 for GSH with a fixed LTA4 concentration (20 μm) and for LTA4 with a fixed GSH concentration (10 mm) were measured following the method described above. The concentration of GSH was varied from 2 to 10 mm for the kcat/Km of GSH, and the concentration of LTA4 was changed from 1 to 20 μm for the kcat/Km of LTA4. The reaction time of this assay was 2 min.

Quantification of LTC4-Me or LTC4 in a 100-μl aliquot of the 808-μl terminated sample was carried out by RP-HPLC, as described below. The assays for each condition were repeated at least three times. GraphPad Prizm5.0a was used for the calculation of the kinetic parameters by non-linear regression analysis with the Michaelis-Menten equation.

Reverse Phase HPLC Analysis

The quantification of LTC4-Me was performed using RP-HPLC with a SYSTEM GOLD 126 solvent module, a 168 detector, a 508 autosampler (Beckman-Coulter) (37), and a YMC-Pack PolymerC18 (4.6- × 250-mm, S-6 μm). The column was equilibrated with solvent A at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. A mixture of 80 ml of methanol, 120 ml of acetonitrile, and 1.6 ml of acetic acid was diluted to 1 liter by water, and then the pH of the solution was adjusted to pH 6.0 by small aliquots of ethanolamine to prepare solvent A. Solvent B for the RP-HPLC analysis was 100% methanol. The mobile phase for the assay with LTA4-Me and that for the assay with LTA4 were 61 and 48% solvent B, respectively, and it was maintained for 13 min after injection of the sample. Then solvent B was increased to 100% without delay and maintained at this level for 7 min. Subsequently, solvent B was returned to that of the first mobile phase for each assay without delay and kept thus for 10 min. The quantification of LTC4-Me or LTC4 was performed based on the ratio between the integrated areas of PGB2 as the internal standard and LTC4-Me or LTC4. In this quantification the molar extinction coefficients at 280 nm for LTC4-Me or LTC4 and for PGB2 were 40,000 (45) and 28,000 (the product insert (Cayman Chemical)), respectively. The retention times of PGB2 and LTC4-Me in the mobile phase of 61% solvent B were 6.5 and 9.7 min, respectively. The retention times of PGB2 and LTC4 in the mobile phase of 48% solvent B were 12.4 and 9.1 min, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was by one-way analysis of variance and multiple comparison test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Relative Activities of the Arg Mutants of LTC4S in Comparison to WT LTC4S

The arginine residues around the entrance of the active site, i.e. Arg-31, Arg-90, Arg-92, Arg-99, Arg-104, and Arg-113, were each subjected to point mutations to evaluate the enzyme activity in comparison to WT LTC4S (Fig. 2). Both LTA4 and LTA4-Me were used as a substrate to evaluate whether the terminal carboxyl group of LTA4 affects the relative activity or not because the negatively charged carboxyl group of LTA4 would interact with certain mutated arginine residue(s). Contrarily, LTA4-Me is a neutral substrate analog with the esterified carboxyl group, resulting in more stable state in aqueous solution (46). LTA4-Me has been used broadly as an alternate substrate instead of LTA4 (37, 47).

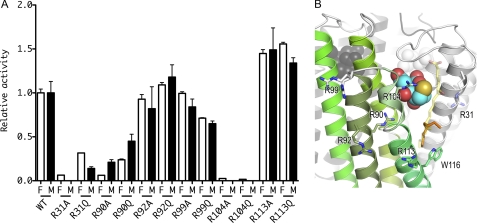

FIGURE 2.

Relative activities of the arginine mutants in comparison to WT LTC4S. A, relative activities of the arginine mutants in comparison to WT LTC4S are shown with S.D. The enzyme activities of the mutant enzymes with LTA4 and LTA4-Me were normalized to the enzyme activities of the WT LTC4S with LTA4 and LTA4-Me, respectively. The open and the closed bars depict the relative enzyme activities measured using LTA4 (F) and LTA4-Me (M), respectively. B, the arginine residues mutated in this work are shown by stick models. The ribbon model with green is a monomer in the LTC4S trimer, and the other two are shown in gray. The translucent stick model with yellow carbons represents the putative LTA4 binding model, and the alkyl chain of the dodecyl maltoside used for the modeling of the LTA4 is shown by the stick model with orange carbons. The conformation of the side chain of Arg-31 is the one most commonly observed (55). The side chain did not have a uniform conformation in the crystal structure. Therefore, the side chain of Arg-31 modeled was represented by the translucent stick model.

The enzyme activity of the mutants of R31A, R90A, R104A, and R104Q was significantly decreased as compared with that of WT LTC4S (p < 0.001). The relative enzyme activities of R31A, R90A, R104A, and R104Q for LTA4 were 0.06 ± 0.002, 0.06 ± 0.001, 0.02 ± 0.006, and 0.02 ± 0.001, respectively. The relative enzyme activity of R90A for LTA4-Me was 0.21 ± 0.03. The enzyme activities of R31A, R104A, and R104Q for LTA4-Me were lower than the detection limit of the RP-HPLC, therefore, the relative enzyme activities were shown by 0.0 in Fig. 2A. Arg-31 and Arg-104 are the amino acid residues proposed to be the catalytic amino acid residues in a previous report (35, 36). Arg-90 forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Asn-57, which is one of the nine amino acid residues that directly binds to GSH (35). Thus, Arg-90 mutations may affect the GSH binding indirectly. Further studies will be needed to elucidate the role of R90 in the catalysis.

We further assessed the enzyme activities of mutant enzymes in which Arg-31 was replaced by a glutamic acid residue (R31E) or a leucine residue (R31L), because R31Q exhibited substantial activity even though the enzyme activity of the R31Q mutant was reduced significantly compared with WT LTC4S (p < 0.001). The relative enzyme activities of R31Q, R31E, and R31L using LTA4 as the substrate were 0.32 ± 0.003, 0.03 ± 0.001, and 0.03 ± 0.001, respectively, and all of these results are statistically significant in comparison to WT LTC4S (p < 0.001).

The enzyme activities of all of the Arg-104 mutants were obviously decreased. The mutants of Arg-31, the side chain of which is hydrophobic or negatively charged, exhibited reduced enzyme activities, whereas R31Q, the side chain of which is a neutral hydrophilic one, maintained substantial enzyme activity. The suppression effect of R31 mutations was profound for both LTA4 and LTA4-Me, although the effect for LTA4 was slightly more modest. Thus, the modification of the terminal carboxyl group of LTA4 may have some effect; however, overall the enzyme activities were substantially reduced particularly for R31 mutants.

Enzyme Kinetics Analysis of WT LTC4S, R31A, and R104A Mutants

Because the R31A and R104A mutants displayed the most marked decrease in enzyme activity, we further assessed their enzymatic kinetic parameters. The kcat/Km of WT LTC4S determined under varying GSH or LTA4-Me concentrations were significantly higher than those of the R31A and R104A mutants (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3, A and B). All of the enzymes exhibited a higher kcat/Km at pH 8.0 than at pH 7.0 or 9.0. The kcat/Km for GSH of WT LTC4S at pH 8.0 was 11.90 ± 1.10 mm−1·s−1, and it was 26- and 770-fold greater than those of the R31A (0.46 ± 0.03 mm−1·s−1) and R104A (0.93 ± 0.06 mm−1·min−1) mutants, respectively. The kcat/Km for LTA4-Me of WT LTC4S at pH 8.0 was 577 ± 35 μm−1· s−1, and it was 160-fold and 60-fold that of the R31A (3.63 ± 0.09 μm−1·s−1) and R104A (9.70 ± 0.64 μm−1·s−1) mutants, respectively.

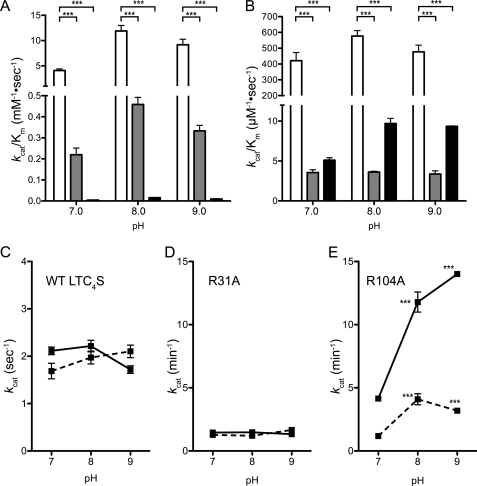

FIGURE 3.

Enzyme kinetic analysis. In panels A and B, the kcat/Km for GSH and LTA4-Me are, respectively, shown. The kcat/Km of WT LTC4S and the R31A and R104A mutants are shown by the white, gray, and black bars with the S.D., respectively (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001. The kcat with S.D. (n = 3) of WT LTC4S and the R31A and R104A mutants are shown in panels C, D, and E, respectively. The kcat values measured with the varying concentrations of GSH and LTA4-Me are shown by the solid and dashed lines, respectively.

The kcat/Km of WT LTC4S activity for LTA4 or LTA4-Me as well as GSH at pH 7.0 were measured to examine the kinetic effect of the carboxyl esterification of LTA4. The kcat/Km for LTA4 and LTA4-Me of WT LTC4S at pH 7.0 were 629 ± 6 and 421 ± 52 μm−1·s−1, respectively. The kcat/Km for GSH of WT LTC4S using a fixed concentration of LTA4 and LTA4-Me at pH 7.0 were 2.8 ± 0.1 and 4.1 ± 0.3 mm−1·s−1, respectively. The measured kcat/Km of WT LTC4S with LTA4 and LTA4-Me were comparable.

Only the R104A mutant exhibited a significant increase of the catalytic constant (kcat) between pH 7.0 and 8.0 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3E). The kcat of R104A increased from 4.15 ± 0.80 min−1 at pH 7.0 to 14.01 ± 0.18 min−1 at pH 9.0 and 11.79 ± 0.80 min−1 at pH 8.0 with the various GSH concentrations (the solid line in Fig. 3E) and from 1.18 ± 0.05 min−1 at pH 7.0 to 4.09 ± 0.44 min−1 at pH 8.0, then 3.19 ± 0.04 min−1 at pH 9.0 with the variable LTA4-Me concentration (the dashed line in Fig. 3E). WT LTC4S maintained a higher level of kcat over the pH range measured; 1.69 ± 0.16 s−1 at pH 7.0, 1.97 ± 0.14 s−1 at pH 8.0 and 2.10 ± 0.13 s−1 at pH 9.0 for the varied LTA4-Me (the dashed line in Fig. 3C), 2.11 ± 0.08 s−1 at pH 7.0, 2.22 ± 0.12 s−1 at pH 8.0, and 1.72 ± 0.08 s−1 at pH 9.0 for the varied GSH with a fixed LTA4-Me concentration (the solid line in Fig. 3C). The R31A mutant maintained a kcat from pH 7.0 to 9.0; the kcat from the various GSH concentrations with a fixed LTA4-Me concentration were 1.46 ± 0.02 min−1 at pH 7.0, 1.48 ± 0.04 min−1 at pH 8.0, and 1.33 ± 0.04 min−1 at pH 9.0 (the solid line in Fig. 3D); those from the various LTA4-Me concentrations were 1.28 ± 0.21 min−1 at pH 7.0, 1.21 ± 0.11 min−1 at pH 8.0, and 1.66 ± 0.14 min−1 at pH 9.0 (the dashed line in Fig. 3D).

The R104A mutant had a Michaelis constant (Km) for GSH higher than 10 mm over the pH range measured, in contrast to WT LTC4S and the R31A mutant, with the Km for GSH at the submillimolar level (Table 2). There is a difference in the pH dependence of Km for GSH between the enzymes with and without Arg-104. The Km for GSH of the WT LTC4S at pH 7.0 was significantly higher than at pH 8.0 or 9.0. The pH dependence of the Km for the GSH of WT LTC4S is comparable with that of the R31A mutant but not the R104A mutant. The R104A mutant had a higher Km for GSH at pH 9.0 than pH 7.0. All enzymes, including the R104A mutant, had a comparable Km for LTA4-Me, although only the R104A mutant exhibited a pH-dependence of Km for LTA4-Me.

TABLE 2.

Michaelis constants for GSH or LTA4-Me

Values are the mean ± S.D.

| Wild type |

R31A |

R104A |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7.0 | pH 8.0 | pH 9.0 | pH 7.0 | pH 8.0 | pH 9.0 | pH 7.0 | pH 8.0 | pH 9.0 | |

| KmGSH mm | 0.520 ± 0.032 | 0.188 ± 0.027a | 0.189 ± 0.017a | 0.104 ± 0.004 | 0.0541 ± 0.0053a | 0.0669 ± 0.0078a | 16.7 ± 0.3 | 12.8 ± 1.6c | 24.6 ± 1.2a |

| KmLTA4-Me μm | 4.08 ± 0.90 | 3.44 ± 0.43 | 4.45 ± 0.65 | 6.09 ± 1.62 | 5.55 ± 0.62 | 8.39 ± 1.84 | 3.85 ± 0.38 | 7.09 ± 1.18c | 5.69 ± 0.05b |

a p < 0.001 as compared to pH 7.0.

b p < 0.05 as compared to pH 7.0.

c p < 0.01 as compared to pH 7.0.

Structural Verification of the R31A and R104A Mutants

To elucidate the role of an individual amino acid residue, it is essential that the mutant enzyme does not suffer damage from the point mutation. Using the crystallographically isomorphous crystals of a mutant enzyme and the WT LTC4S, the difference Fourier method makes it possible to clarify whether there are any differences between the structures of a given mutant enzyme and the WT LTC4S.

We obtained crystallographically isomorphous crystals of the R31A mutant and the WT LTC4S with the space group F23 and a crystal of the R104A mutant isomorphous with the crystal of WT LTC4S with the space group C2221, as described previously (35). The crystallographic parameters and the statistics of the diffraction data from those crystals are shown in Table 1.

The crystal structure of WT LTC4S at 1.9 Å resolution with the space group F23 was refined successfully. The crystallographic R and Rfree values were 0.179 and 0.198 for the diffraction data and 0.225 and 0.246 for the highest resolution shell of 1.95 to 1.90 Å, respectively (Table 1). There was no amino acid residue with the disallowed main chain dihedral angle of φ or ψ on the Ramachandran plot.

The overall structure of LTC4S presented here is basically identical to those previously reported (Fig. 4) (35, 36). In a superimposition between the current and previous structures, the root mean square deviations of the corresponding Cα atoms, except for those from the fifth α-helix extruding into the bulk solvent, are less than 0.4 Å. The architecture for GSH binding is conserved (Fig. 4B). The GSH binding site is a V-shaped cleft at each intermonomer interface in the LTC4S trimer, and nine amino acid residues directly participate in the GSH binding. The minor differences between the current and previous structures are the side-chain conformations of Arg-30 and Arg-104. In the current structure, as shown by the model with the green carbons in Fig. 4B, Arg-30 multiply binds the carboxyl group of the γ-glutamyl moiety, and Arg-104 interacts with both the thiol group and the carbonyl group of the cysteinyl moiety of GSH. The current side chain conformations of Arg-30 and Arg-104 are similar to those observed in the crystal grown with ammonium sulfate rather than polyethylene glycol as the precipitant agent (35, 36). The side chain of Arg-31 was flexible in the crystal structure, and the electron density corresponding to the side chain before the Cβ of Arg-31 was not apparent in the electron density map contoured at 1.2σ. This refined crystal structure of WT LTC4S allowed us to visualize the structural differences between WT LTC4S and the mutants of R31A by the difference Fourier method.

FIGURE 4.

Crystal structure of WT LTC4S at 1.9 Å resolution. A, the crystal structure of LTC4S was determined to be a trimer with a three-fold axis at the center. Each monomer in the LTC4S trimer is colored green with gradations, light gray, and dark gray. The roman numeral shows the sequential order of the α-helix from the N-terminal. Stick models in yellow show the hydrocarbon tails of the dodecyl maltosides. The stick models in white are ethylene glycols or sulfate ions. The Corey-Pauling-Koltun model represents the bound GSHs. The characters N and C indicate the N and C termini of the current model. B, superimposition of the GSH binding sites is shown. The GSH binding sites of the current study (green carbons; this work) and previous studies (white carbons; PDB ID 2PNO) are superimposed. Dashed lines show the polar intermolecular interactions of less than 3.5 Å.

The R104A mutant was crystallized using the conditions as previously reported (35). Under the current crystallization conditions with ammonium sulfate and magnesium chloride as the precipitant agents, WT LTC4S, in which the guanidino side chain of Arg-104 binds a sulfate ion, crystallized in the space group F23, but the R104A mutant missing the side chain of Arg-104 did not crystallize. Thus, we used the previous crystallization conditions with polyethylene glycol 400 as the precipitant agent for crystallization of the R104A mutant. The R104A mutant crystallized in the space group C2221.

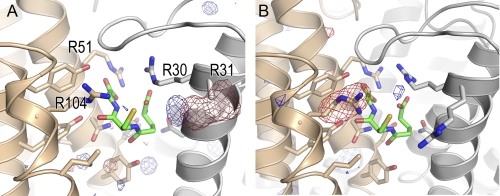

There were no significant residual electron densities, except for the residual electron density corresponding to the side chain of the mutated amino acid residue in both of the difference Fourier electron density maps for each pair of the isomorphous crystals (Fig. 5). The difference Fourier electron density maps supported the conclusion that the three-dimensional structures of the R31A and R104A mutants did not suffer any damage from the point mutations.

FIGURE 5.

Difference Fourier maps of the R31A and R104A mutants. The difference Fourier electron density maps for R31A (panel A) and R104A (panel B) were calculated from Fourier coefficients and the phases of FR31A(F23) − FWT(F23), φwt(F23) and FR104A(C2221) - FWT(C2221), φwt(C2221), respectively. The R-factors between the diffraction intensity data of the WT LTC4S and the R31A mutant and between the diffraction intensity data of the WT LTC4S and the R104A mutant were 0.082 and 0.192, respectively. The map for R31A was contoured at +4.5σ (blue) and −4.5σ (red), and that for R104A was contoured at +4σ (blue) and −4σ (red). The atomic models in panel A and B are the WT LTC4S in this work and the previous work (PDB ID 2PNO), respectively.

The far-ultraviolet CD analysis showed that the secondary structure composition of WT LTC4S and the R31A and R104A mutants in solution were not distinguishable from each other. The percentages of the secondary structure of WT LTC4S, R31A, and R104A estimated from each CD spectrum were similar to each other; the percentages of the α-helix, β-strand, and random loop of WT LTC4S were 69, 4, and 27%, respectively, whereas those of R31A were 64, 6, and 30%, and those of R104A were 62, 6, and 32%. The percentages were calculated by the K2d program (48). Thus, both the x-ray crystallographic analysis and the CD analysis of the WT LTC4S, R31A, and R104A mutants confirmed that there was no significant structural difference between their three-dimensional structures.

DISCUSSION

Based on the previous x-ray crystallographic studies, we proposed that Arg-31 and Arg-104 constitute the catalytic architecture for conjugating LTA4 and GSH in the active site of LTC4S (Fig. 1) (35). To investigate further, we prepared mutant enzymes and performed the assays for enzymatic analysis to obtain first order kinetics as well as verification of the three-dimensional structures of the mutants.

Role of Arg-31 and Arg-104 in the Catalysis

The kcat/Km of the WT LTC4S measured at pH 7.0, 8.0, and 9.0 were significantly higher than both of the R31A and R104A mutants (Fig. 3, A and B). The effects of each point mutation on the three-dimensional structures of the mutants were examined by the crystallographic and CD analyses. Using each corresponding isomorphous crystal, there were no indications of any significant structural changes in the difference Fourier maps between each mutant and the WT LTC4S other than the mutated residue, Arg-31 or Arg-104 (Fig. 5). In the CD analyses, the secondary structural elements of these mutants were similar to those of WT LTC4S. These results support the conclusion that the decreased kcat/Km of the mutants in comparison with WT LTC4S was caused by the lack of the side chain of Arg-31 or Arg-104, not by denaturing or partial unfolding imposed by the point mutation. It cannot be excluded that a certain minor structural perturbation may occur that is undetectable by the CD and the crystallographic analyses. As discussed below, Arg-31 and Arg-104 may play distinct roles in the enzymatic catalysis and cooperate to propagate conjugation between GSH and LTA4 at physiological pH levels.

The binding function of Arg-104 for GSH was established because the R104A mutant exhibited a higher Km for GSH than the WT LTC4S and R31A mutants, in which the Km values are at the submillimolar level (Table 2). Furthermore, the pH dependence of the Km for the GSH of the WT LTC4S, R31A, and R104A mutants supports the binding function of Arg-104, as discussed below. The Km for the GSH of the WT LTC4S and R31A mutant was significantly decreased at pH 8.0 and higher pH (p < 0.001 against pH 7.0). The Km for the GSH of the R104A mutant increases at pH9.0 (p < 0.001), with a decrease at pH 8.0 (p < 0.05), in comparison with that at pH 7.0. The decreased Km for GSH at alkaline pH indicates that the enzymes with Arg-104 retained a higher affinity for GSH at the alkaline pH measured, in contrast to that of the enzyme without Arg-104, having a lower affinity for GSH at pH 9.0. The positively charged guanidino side chain of Arg-104 interacts with the thiol group of GSH directly in the crystal structure. The thiol group of GSH becomes a negatively charged thiolate anion at alkaline pH. Thus, attractive interaction between the positively charged side chain of Arg-104 and the negatively charged thiolate anion of GSH at alkaline pH contributes to the maintenance of the high affinity for GSH at alkaline pH.

In addition to the binding function, the pH-dependent increase of the kcat of the R104A mutant to approximately the pKa of the thiol group shows the GSH activating function of Arg-104 at physiological pH (Fig. 3). The value of kcat is correlated to deprotonation of the thiol group, resulting in the formation of the thiolate anion as the active species in the catalysis. WT LTC4S has kcat values which are just as high at pH 7.0 as at a pH of 8.0 or higher. Therefore, the thiol group in the active site of WT LTC4S is considered to be deprotonated, even at pH 7.0. In contrast, the kcat of the R104A mutant increases in a pH-dependent manner. The kcat of the R104A mutant at pH 8.0 and pH 9.0 is ∼3-fold higher than at pH 7.0. Thus, the thiolate anion in the active site missing the Arg-104 increases at pH values higher than pH 7.0. The pH dependence profile of the deprotonation of GSH in the active site of the R104A mutant is concluded to be similar to that of free GSH with a normal pKa (49). Thus, the guanidino side chain interacting with the thiol group of GSH is responsible for the activation of the thiol group at pH 7.0 as well as the binding function of GSH, as discussed above.

We have proposed that the guanidino side chain of Arg-31 forms a hydrogen bond with the epoxide oxygen, resulting in the formation of an electron deficient epoxide carbon as the target of nucleophilic attack by the thiolate anion of GSH at the initiation of catalysis (Fig. 1) (35). This is because the protonation of the epoxide group of LTA4 has a significant impact on the reactivity of the epoxide group (38, 39). Although the guanidino side chain of arginine has an extremely high pKa, the guanidino side chain can form a hydrogen bond with various polar functional groups, such as hydroxyl groups so forth (50, 51). Furthermore, recent computational studies have proposed that the guanidino side chain of arginine residue can act as a general acid (52, 53). We have also proposed that Arg-31 neutralizes a negative charge growing on the epoxide oxygen in the propagation of the nucleophilic attack on the electro-deficient carbon by the thiol group of GSH (Fig. 1) (35).

The enzymatic assay results for the R31A mutant were consistent with the previous proposal for the roles of Arg-31 in the catalysis (35). The remarkably decreased kcat and kcat/Km value of the R31A mutant in comparison to that of the WT LTC4S suggested that the side chain of Arg-31 interacts with a catalytically essential functional group of LTA4-Me (Fig. 3). The pH dependence of kcat of the R31A mutant, which was similar with that of the WT-LTC4S, showed that the side chain of Arg-31 may interact with the functional group of LTA4-Me, having a pKa outside of the measured pH range. The epoxide group of LTA4 is the essential functional group and also has a pKa outside of the measured pH range. This supports Arg-31 being the amino acid residue that interacts with the epoxide group of LTA4.

Arg-31, but not bulk water, is supposed to form an effective hydrogen bond with the epoxide oxygen, accelerating the enzymatic catalysis. The R31A mutant with Ala-31, having a small apolar side chain, the R31L mutant with Leu-31, with a large apolar side chain, and the R31E mutant with Glu-31, having a negatively charged polar side chain, instead of Arg-31, with the longest and positively charged polar guanidino side chain, exhibited enzyme activity reduced to less than one tenth of the WT LTC4S (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the R31Q mutant, exhibiting 30% enzyme activity in comparison to WT LTC4S, shows that the neutral polar side chain of Gln-31 partly compensated for the role of the positively charged guanidino side chain of Arg-31 (Fig. 2A). Gln-31 cannot interact directly with an epoxide group such as Arg-31 due to the side chain being shorter than that of the arginine residue; thus, Gln-31 might affect the epoxide group through the hydrated water molecule(s) of the polar side chain of Gln-31. In addition, the drastically decreased enzymatic activity of the R31A and R31L mutants shows that the bulk water molecules are unable to compensate for the role of Arg-31 on the epoxy group. Furthermore, the R31E mutant with decreased enzyme activity shows that the negatively charged side chain of Glu-31 cannot compensate for the role of Arg-31 with the positively charged side chain, in contrast to Gln-31. The negatively charged side chain of Glu-31 makes the hydrated water molecules electrostatically negative. Therefore, the electrostatically negative water molecule hardly interacts with the negatively polarized epoxide oxygen or the negatively charged alkoxide group formed in the course of the catalysis. A polar functional group with fewer degrees of freedom of motion around the epoxide group of LTA4, such as the guanidino side chain of Arg-31 or the hydrated water molecule of Gln-31, makes an effective hydrogen bond with the epoxide group so as to accelerate the nucleophilic attack. Arg-31 probably fits as a catalytic amino acid residue for LTA4.

In comparison with WT LTC4S, the R31A mutant sustained a comparable Km for LTA4-Me despite a much lower kcat (Table 2 and Fig. 3D). This suggests that Arg-31 does not contribute to the LTA4-Me binding, in contrast to the binding activity of Arg-104 for GSH.

LTC4S has certain unique features as a nuclear membrane-embedded enzyme responsible for LTC4 biosynthesis. In our proposed catalytic mechanism, Arg-31 and Arg-104 function as the catalytic amino acid residues by forming a hydrogen bond with LTA4 and GSH, respectively. Arg-104 forming hydrogen bonds with the thiol group of GSH facilitates the formation of the thiolate anion as the nucleophile, and the thiolate anion attacks the epoxide carbon of LTA4. Furthermore, Arg-104 also substantially contributes to GSH binding. Arg-31, which increases the electrophilicity of the epoxide carbon of LTA4 through a hydrogen bond with the epoxide oxygen, makes the nucleophilic attack easy at the initial step. Concomitantly with the development of the nucleophilic attack, the protonated guanidino side chain of Arg-31 neutralizes the negative charge growing on the epoxide oxygen through the hydrogen bond. At the final step of the nucleophilic attack, Arg-31 may donate a proton at the generated alkoxide from the epoxide oxygen to transform the alkoxide group to the hydroxyl group of the product, LTC4, because alkoxide, the pKa of which is 16–18, is more basic than the guanidino side chain of the arginine residue (54).

The results of the enzyme assay on the mutants of Arg-31 are consistent with the current LTA4 binding model but not sufficient to conclude that the model is correct. The model is speculated based on the crystal structure of the LTC4S complex with the hydrocarbon tail of dodecyl maltoside at the putative LTA4 binding site. Determination of the complexed structure of LTC4S with LTA4 is required to understand the LTA4 binding mode and functional role of Arg-31; however, the crystal structure analysis of LTC4S complexed with LTA4 is a great challenge because LTA4 is not stable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shunji Goto at SPring-8/JASRI for providing the opportunity to collect the diffraction data set with the beamline optics of the newly developed dynamic sagittal-focusing monochromator.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI31599, HL36110, and HL82695 (to B. K. L.) and HL90630 (to Y. K.). This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research in the Global Center of Excellence program (A-12) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to H. A.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3PCV) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- LT

- leukotriene

- cys-LT

- cysteinyl leukotrienes

- LTC4S

- LTC4 synthase

- LTA4-Me

- LTA4 methyl ester

- DDM

- dodecyl-β-d-maltoside

- BisTris propane

- 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane

- PGB2

- prostaglandin B2

- RP

- reverse phase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rouzer C. A., Scott W. A., Cohn Z. A., Blackburn P., Manning J. M. (1980) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77, 4928–4932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacGlashan D. W., Jr., Peters S. P., Warner J., Lichtenstein L. M. (1986) J. Immunol. 136, 2231–2239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. MacGlashan D. W., Jr., Schleimer R. P., Peters S. P., Schulman E. S., Adams G. K., 3rd, Newball H. H., Lichtenstein L. M. (1982) J. Clin. Invest. 70, 747–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weller P. F., Lee C. W., Foster D. W., Corey E. J., Austen K. F., Lewis R. A. (1983) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 7626–7630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barrett N. A., Maekawa A., Rahman O. M., Austen K. F., Kanaoka Y. (2009) J. Immunol. 182, 1119–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dahlén S. E., Hedqvist P., Hammarström S., Samuelsson B. (1980) Nature 288, 484–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weiss J. W., Drazen J. M., Coles N., McFadden E. R., Jr., Weller P. F., Corey E. J., Lewis R. A., Austen K. F. (1982) Science 216, 196–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dahlén S. E., Björk J., Hedqvist P., Arfors K. E., Hammarström S., Lindgren J. Å., Samuelsson B. (1981) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 3887–3891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soter N. A., Lewis R. A., Corey E. J., Austen K. F. (1983) J. Invest. Dermatol. 80, 115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wardlaw A. J., Hay H., Cromwell O., Collins J. V., Kay A. B. (1989) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 84, 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith C. M., Christie P. E., Hawksworth R. J., Thien F., Lee T. H. (1991) Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 144, 1411–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Israel E., Dermarkarian R., Rosenberg M., Sperling R., Taylor G., Rubin P., Drazen J. M. (1990) N. Engl. J. Med. 323, 1740–1744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manning P. J., Watson R. M., Margolskee D. J., Williams V. C., Schwartz J. I., O'Byrne P. M. (1990) N. Engl. J. Med. 323, 1736–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knapp H. R. (1990) N. Engl. J. Med. 323, 1745–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donnelly A. L., Glass M., Minkwitz M. C., Casale T. B. (1995) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 151, 1734–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pacor M. L., Di Lorenzo G., Corrocher R. (2001) Clin. Exp. Allergy 31, 1607–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clark J. D., Milona N., Knopf J. L. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 7708–7712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rouzer C. A. F., Samuelsson B. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 6040–6044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dixon R. A., Diehl R. E., Opas E., Rands E., Vickers P. J., Evans J. F., Gillard J. W., Miller D. K. (1990) Nature 343, 282–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Woods J. W., Evans J. F., Ethier D., Scott S., Vickers P. J., Hearn L., Heibein J. A., Charleson S., Singer I. I. (1993) J. Exp. Med. 178, 1935–1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yoshimoto T., Soberman R. J., Spur B., Austen K. F. (1988) J. Clin. Invest. 81, 866–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jakobsson P. J., Morgenstern R., Mancini J., Ford-Hutchinson A., Persson B. (1999) Protein Sci. 8, 689–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bresell A., Weinander R., Lundqvist G., Raza H., Shimoji M., Sun T. H., Balk L., Wiklund R., Eriksson J., Jansson C., Persson B., Jakobsson P. J., Morgenstern R. (2005) FEBS J. 272, 1688–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shi Z. Z., Han B., Habib G. M., Matzuk M. M., Lieberman M. W. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5389–5395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Habib G. M., Shi Z. Z., Cuevas A. A., Lieberman M. W. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 1313–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krilis S., Lewis R. A., Corey E. J., Austen K. F. (1983) J. Clin. Invest. 71, 909–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sala A., Voelkel N., Maclouf J., Murphy R. C. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 21771–21778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lynch K. R., O'Neill G. P., Liu Q., Im D. S., Sawyer N., Metters K. M., Coulombe N., Abramovitz M., Figueroa D. J., Zeng Z., Connolly B. M., Bai C., Austin C. P., Chateauneuf A., Stocco R., Greig G. M., Kargman S., Hooks S. B., Hosfield E., Williams D. L., Jr., Ford-Hutchinson A. W., Caskey C. T., Evans J. F. (1999) Nature 399, 789–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heise C. E., O'Dowd B. F., Figueroa D. J., Sawyer N., Nguyen T., Im D. S., Stocco R., Bellefeuille J. N., Abramovitz M., Cheng R., Williams D. L., Jr., Zeng Z., Liu Q., Ma L., Clements M. K., Coulombe N., Liu Y., Austin C. P., George S. R., O'Neill G. P., Metters K. M., Lynch K. R., Evans J. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30531–30536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim D. C., Hsu F. I., Barrett N. A., Friend D. S., Grenningloh R., Ho I. C., Al-Garawi A., Lora J. M., Lam B. K., Austen K. F., Kanaoka Y. (2006) J. Immunol. 176, 4440–4448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beller T. C., Friend D. S., Maekawa A., Lam B. K., Austen K. F., Kanaoka Y. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 3047–3052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paruchuri S., Tashimo H., Feng C., Maekawa A., Xing W., Jiang Y., Kanaoka Y., Conley P., Boyce J. A. (2009) J. Exp. Med. 206, 2543–2555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paruchuri S., Jiang Y., Feng C., Francis S. A., Plutzky J., Boyce J. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16477–16487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maekawa A., Kanaoka Y., Xing W., Austen K. F. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16695–16700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ago H., Kanaoka Y., Irikura D., Lam B. K., Shimamura T., Austen K. F., Miyano M. (2007) Nature 448, 609–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Martinez Molina D., Wetterholm A., Kohl A., McCarthy A. A., Niegowski D., Ohlson E., Hammarberg T., Eshaghi S., Haeggström J. Z., Nordlund P. (2007) Nature 448, 613–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lam B. K., Penrose J. F., Xu K., Baldasaro M. H., Austen K. F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13923–13928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rådmark O., Malmsten C., Samuelsson B., Goto G., Marfat A., Corey E. J. (1980) J. Biol. Chem. 255, 11828–11831 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carrier D. J., Bogri T., Cosentino G. P., Guse I., Rakhit S., Singh K. (1988) Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 34, 27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schmidt-Krey I., Kanaoka Y., Mills D. J., Irikura D., Haase W., Lam B. K., Austen K. F., Kühlbrandt W. (2004) Structure 12, 2009–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Okazaki K., Okazaki N., Kume K., Jinno S., Tanaka K., Okayama H. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 6485–6489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ueno G., Kanda H., Hirose R., Ida K., Kumasaka T., Yamamoto M. (2006) J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 7, 15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Adachi S., Oguchi T., Tanida H., Park S. Y., Shimizu H., Miyatake H., Kamiya N., Shiro Y., Inoue Y., Ueki T., Iizuka T. (2001) Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 467, 711–714 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Collaborative Computational Project Number 4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–76315299374 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lewis R. A., Austen K. F., Drazen J. M., Clark D. A., Marfat A., Corey E. J. (1980) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77, 3710–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maycock A. L., Anderson M. S., DeSousa D. M., Kuehl F. A., Jr. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 13911–13914 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lam B. K., Penrose J. F., Freeman G. J., Austen K. F. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 7663–7667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Andrade M. A., Chacón P., Merelo J. J., Morán F. (1993) Protein Eng. 6, 383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen W. J., Graminski G. F., Armstrong R. N. (1988) Biochemistry 27, 647–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gu Y., Singh S. V., Ji X. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 12552–12557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hoff R. H., Hengge A. C., Wu L., Keng Y. F., Zhang Z. Y. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Silva P. J., Ramos M. J. (2005) J. Phys. Chem. B. 109, 18195–18200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Silva P. J., Schulz C., Jahn D., Jahn M., Ramos M. J. (2010) J. Phys. Chem. B. 114, 8994–9001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Steiner E. C., Gilbert J. M. (1963) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85, 3054–3055 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lovell S. C., Word J. M., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2000) Proteins 40, 389–408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.