Abstract

The protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi is the causative agent of human Chagas disease, for which there currently is no cure. The life cycle of T. cruzi is complex, including an extracellular phase in the triatomine insect vector and an obligatory intracellular stage inside the vertebrate host. These phases depend on a variety of surface glycosylphosphatidylinositol-(GPI-) anchored glycoconjugates that are synthesized by the parasite. Therefore, the surface expression of GPI-anchored components and the biosynthetic pathways of GPI anchors are attractive targets for new therapies for Chagas disease. We identified new drug targets for chemotherapy by taking the available genome sequence information and searching for differences in the sphingolipid biosynthetic pathways (SBPs) of mammals and T. cruzi. In this paper, we discuss the major steps of the SBP in mammals, yeast and T. cruzi, focusing on the IPC synthase and ceramide remodeling of T. cruzi as potential therapeutic targets for Chagas disease.

1. Introduction

Sphingolipids (SLs) belong to a diverse group of amphipathic lipids that have essential functions in eukaryotes. They are constituents of cellular membrane compartments and participate in a diverse array of signal transduction processes [1, 2]. The final products of the sphingolipid biosynthetic pathways (SBPs) are different in mammals, fungi, plants and protozoa. Thus, certain steps of this pathway are potential targets for chemotherapy against fungal [3] and protozoal infections [4–6]. Sphingomyelin (SM) is the primary phosphosphingolipid that is produced by mammalian cells, including in humans [7]. This molecule is formed by the transfer of the choline-phosphate head group from phosphatidylcholine (PC) to ceramide, a reaction catalyzed by SM synthase [8]. In contrast, plants, fungi, and some protozoa synthesize inositolphosphorylceramide (IPC) as their primary phosphosphingolipid [9]. In this pathway, the IPC synthase enzyme [10] catalyzes the transfer of inositol phosphate to ceramide. IPC makes up a relatively low proportion of fungal phospholipids. Nonetheless, it is essential, as IPC synthase-null mutants are not viable [11] and inhibitors of this enzyme kill fungal cells [12, 13].

Numerous proteins and glycolipids are attached to membranes by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. This posttranslational modification is conserved among yeast, protozoa, plants and animals [14]. All of these groups except animals have GPI anchors containing IPC as an attached lipid. GPI biosynthesis is essential for mammalian embryonic development and the growth of yeasts and trypanosomes [15–17]. The biosynthesis and maturation of GPI anchors occurs during the ER-to-Golgi transit, beginning with the sequential addition of sugars and ethanolamine phosphates to phosphatidylinositol (PI). Subsequent structural remodeling reactions can happen during biosynthesis or after attachment to proteins. Most of these steps have been studied at the biochemical and molecular levels [18, 19]. Recently, it has been shown that GPI lipid remodeling reactions are important for maintaining the correct fate of GPI-anchored glycoconjugates and their proper association with microdomains in certain cellular processes [20, 21].

Several neglected tropical diseases worldwide are caused by a group of trypanosomatid protozoan parasites (also known as Tritryps), including the following: (i) African trypanosomes (Trypanosoma brucei subspecies), which cause sleeping sickness, (ii) multiple Leishmania species, which cause cutaneous and visceral forms of leishmaniases, and (iii) Trypanosoma cruzi, which causes Chagas disease [22–26]. Recent studies have shown that all of these parasites are capable of synthesizing IPC and that the expression of IPC is regulated during development.

The genome sequences of these pathogenic microrganisms have recently been published, allowing us to search for differences between the SL and GPI structures of mammals and Tritryps to identify novel drug targets. Here, we will discuss the major steps of the SBP in mammals, yeast and Tritryps. We will focus on the IPC synthase and ceramide remodeling of T. cruzi as potential therapeutic targets for Chagas disease.

2. Initial Steps in the De Novo Synthesis of a Sphingoid Long-Chain Base

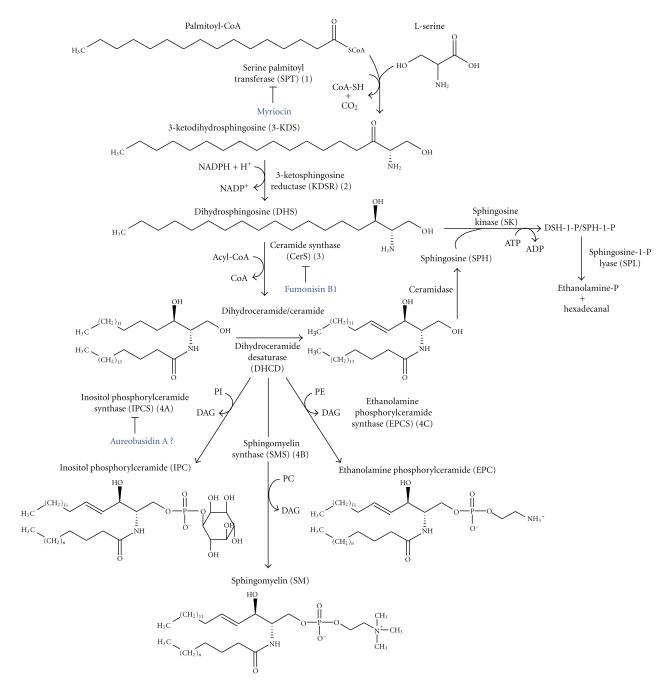

In all eukaryotes, de novo SL biosynthesis starts with the condensation of L-serine and palmitoyl-CoA into 3-ketodihydrosphingosine (3-KDS), as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. A pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent enzyme called serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) catalyzes this reaction. The SPT enzyme (Figure 1 and Table 1, Step 1) is a complex of two subunits, SPT1 and SPT2 [27]. In yeast, the small peptide TSC3 significantly enhances SPT activity [28]. Two open reading frames (ORFs) with homology to yeast LCB1 and LCB2 can be found in the Tritryp genome database. Although SPT1p and SPT2p function as a heterodimer, all experimental data indicate that the SPT2 subunit contains the catalytic site [28]. For this reason, most of the studies on Tritryps (mainly L. major and T. brucei) have focused on SPT2.

Figure 1.

General scheme of the SBP in Tritryps. Substrates, products, enzymes and effective/potential (?) inhibitors of the four (1–4) initial SBP steps are indicated as described in the text and in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genes required for sphingolipid biosynthesis and lipid remodeling steps in mammals, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Trypanosoma brucei, Leishmania major, and Trypanosoma cruzi.

| Step | Activity | Mammals | S. cerevisiae | T. brucei | L. major | T. cruzi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SPT |

LCB1 LCB2 |

LCB1/LCB2 TSC3 |

TbSPT1 TbSPT2 |

LmSPT1 LmSPT2 |

TcSPT1 TcSPT2 |

| 2 | KDSR | FVT-1 | TSC10 | Tb927.10.4040(a) | LmjF.35.0330 |

Tc00.1047053510997.10 Tc00.1047053506959.64(a) |

| 3 | CERS | CERS1-6 |

LAG1/LAC1 LIP1 |

Tb927.8.7730 Tb927.4.4740 |

LmjF.31.1780 | TcCERS1 |

| 4 | SLS |

SMS1 SMS2 |

AUR1 KEI1 |

TbSLS1-4 | LmIPCS |

TcIPCS1 TcIPCS2 |

| 5 | ID | PGAP1 | BST1 | GPIdeAc2 | —(b) | Tc00.1047053508153.1040(a) |

| 6 | GPIPLA2 | PGAP3 | PER1 | — | — | — |

| 7 | LGPIAT-I | PGAP2 | GUP1 | TbGUP1 |

LmjF.19.1000/LmjF.19.1320 LmjF.19.1340/LmjF.19.1345 LmjF.19.1347(a) |

TcGUP1(c) |

| 8 | CR | — | CWH43 | — | LmjF27.1770(a) | Tc00.1047053504153.120(a) |

(a)Corresponding homologues of each yeast gene were found by BLAST at NCBI and GeneDB (http://www.genedb.org/).

(b)Not found.

(c) TcGUP can be Tc00.1047053508943.4, Tc00.1047053511355.59, or Tc00.1047053503809.90.

The expression of the LmSPT2 gene (also called LmLCB2) is developmentally regulated. LmSPT2p is undetectable in the late stationary growth phase of promastigotes, as well as in metacyclic trypomastigotes and intramacrophage amastigotes [29, 30]. Deletion of the SPT2 gene in L. major results in a complete loss of IPC and ceramide, whereas other alkyl/acyl and acyl/acyl phospholipids remain unchanged [29]. Although spt2− mutant promastigotes are viable and grow during log phase, they fail to efficiently differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes and die rapidly at this stage. This phenotype can be rescued either by the addition of sphingoid bases (3-ketodihydrosphinsosine or 3-KDS, dihydrosphingosine, sphingosine, and phytosphingosine), ethanolamine (EtN) or EtN-phosphate to the medium, or by complementation with the original LmLCB2 gene [29–33]. However, neither ceramide nor SM can rescue the stationary phase defects or restore IPC synthesis [29]. Similar observations have previously been made in yeast and mammalian SPT-deficient mutants [34, 35]. Denny and Smith [30] showed that exocytic trafficking is compromised in spt2− mutants, but Zhang and colleagues [29, 32] observed little negative effect on vesicular trafficking. However, both groups found that spt2− parasites retain their ability to form membrane microdomains and lipid rafts [29, 32, 33]. It has been suggested that Leishmania can compensate for the loss of SLs by increasing its overall level of lipid synthesis, for example, by increasing ergosterol [31] or GIPL [33] production. These spt2− mutants are still able to establish infection in a mouse model, although with some delay [33], confirming that the first step in the de novo SBPs is unnecessary for either the survival of Leishmania within host macrophages or the resulting pathogenesis.

In contrast, the first step of the SBPs, which is catalyzed by SPT, is essential in T. brucei. This conclusion was based on pharmacological experiments with myriocin (Figure 1, Step 1), an inhibitor of SPT [36], and genetic experiments [37, 38]. These perturbations most profoundly affect viability, cellular proliferation and cytokinesis, with marginal effects on secretory trafficking and lipid raft formation. SL depletion can be rescued by the addition of 3-KDS, the immediate downstream intermediate in the SBPs, but not by the addition of ceramide or EtN [37, 38]. These results indicate that T. brucei absolutely requires de novo synthesis of SLs.

In the second step of SL biosynthesis (Figure 1 and Table 1, Step 2), the product 3-KDS is rapidly converted into dihydrosphingosine (DHS; sphinganine) in a NADPH-dependent manner by the 3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase (KDSR) encoded by TSC10 (temperaturesensitive suppressor of cgs2Δ) in S. cerevisiae [39] and by FVT-1 (follicular lymphoma variant translocation-1) in mammals [40]. Although KDSR activity has not been measured in parasites, TSC10 homologues can be found in the genomes of Tritryps (Table 1). A predicted TcKDRS can be found in the GeneDB database in two genomic fragments (Tc00.1047053510997.10 and Tc00.1047053506959.64) whose nucleotide and amino acid sequences are 98% identical. These probably correspond to the two haplotypes present in the hybrid CL-Brener strain [41].

3. Ceramide Synthase: The Central Axis of the SBPs

The next step in the SBPs, the synthesis of ceramide, is a key component of the pathway (Figure 1 and Table 1, Step 3). Ceramide is critical for cell growth and functions in several different cellular events, including apoptosis, growth arrest, endocytosis and stress responses [42–44]. Ceramide can be degraded by a ceramidase, or the sphingoid bases can be phosphorylated to produce DHS-1-P/SPH-1-P signaling molecules (Figure 1). Ceramide is synthesized mainly from the reaction of a fatty acyl-CoA with a sphingoid base catalyzed by an acyl-CoA:sphingosine N-acyltransferase or ceramide synthase (CerS) [45, 46]. An acyl-CoA-independent CerS activity has been described [47, 48] although it probably represents a reversal of ceramidase action. In yeasts, the long-chain base (LCB) DHS can be hydroxylated at C-4 by SUR2/SYR2 [49] to form the sphingoid base phytosphingosine, which is later N-acylated by either of the two CerSs, encoded by LAG1 (longevity assurance gene) or LAC1 [50, 51], to yield phytoceramide. In mammals, DHS can be directly N-acylated by a family of CerSs encoded by CERS1-6 genes [52]. In addition, another essential component of the yeast CerS, known as Lip1p, was described recently. It forms a heteromeric complex with Lac1p and Lag1p and is required for CerS activity in yeast [53]. No orthologue of Lip1 has yet been found in nonfungal species.

In Trypanosomatids, ceramide can be found as a lipid component of phospholipids like SM, in T. brucei, and IPC, which is expressed in all Tritryps [54–62]. CerS activity has been identified [54] and characterized at the biochemical and molecular levels only in T. cruzi ([63], submitted). The TcCerS was initially identified by the incorporation of [3H]palmitic acid into ceramides, which were chemically degraded to radiolabeled dihydrosphingosine and fatty acid [54]. More recently, TcCerS activity has been detected in a cell-free system using the microsomal fraction of epimastigote forms of T. cruzi. In this system, the enzyme was shown to employ both sphingoid long-chain bases (DHS and SPH) ([63], submitted). This activity requires acyl-CoAs, with palmitoyl-CoA being preferred. In addition, Fumonisin B1, a broadly active and well-known acyl-CoA-dependent CerS inhibitor (Figure 1, Step 3), blocks parasite CerS activity ([63], submitted). However, unlike what has been observed in fungi, the CerS inhibitors Australifungin [64] and Fumonisin B1 [65] do not affect the proliferation of epimastigotes in culture ([63], submitted). Orthologues of the conserved Lag1-domain from yeast CerS, LAG1, were identified in a search of the Tritryp genome sequences (Table 1). The T. cruzi candidate gene (TcCERS1), which was hypothesized to encode the parasite's CerS orthologue, can functionally complement the lethality of a lag1Δ lac1Δ double-deletion yeast mutant that has no detectable acyl-CoA-dependent CerS ([63], submitted).

Glycoinositolphospholipids (GIPLs) are abundant surface glycoconjugates of T. cruzi and are involved in the pathogenesis of Chagas disease [66, 67]. GIPLs contain an IPC-lipid anchor that is formed by dihydroceramide N-acylated with palmitic or lignoceric acids [68–72]. TcCerS uses only palmitoyl-CoA as a substrate donor ([63], submitted); it is not known how the parasite incorporates C24:0 into ceramides. Recently, a novel fatty acid synthesis system was identified in the Tritryps [73]. In this system, synthesis is mediated by elongases that prime a butyryl-CoA molecule with malonyl-CoA units as the donor substrate and promote fatty acid extension to a length of 18 carbons or longer. Therefore, it is possible that this system elongates shorter fatty acids to C24:0 so that they can then be incorporated into ceramides. Alternatively, the substrate could be another fatty acid, like arachidonate (C20:4 from extracellular sources), which could be elongated and desaturated further to generate very-long-chain fatty acids [73]. Finally, IPC acyl-hydrolase and IPC acyl-transferase activities have been detected in membranes of T. cruzi [74, 75] and could be involved in the remodeling of the endogenous ceramide C16:0 fatty acids by an extracellular fatty acid (see below).

4. IPC Synthase Activity

The synthesis of IPC (Figure 1 and Table 1, Step 4A) occurs by the transfer of inositol phosphate from PI to the C-1 hydroxyl group of ceramide or phytoceramide. This reaction is catalyzed by IPC synthase, which is localized to the Golgi of yeasts. IPC synthase is encoded by AUR1 (also called IPC1) [11]. As already mentioned, IPC represents a relatively low proportion of fungal phospholipids, but it is essential. IPC synthase-null mutants are not viable [11], and fungal cells are killed by the IPC synthase inhibitors Aureobasidin A (AbA) [12] and Rustmicin [13]. Recently, a critical protein interaction partner for yeast IPC synthase was identified and named Kei1p. It was shown that Kei1p is essential for both yeast IPC synthase activity and for its sensitivity to AbA [76]. As shown in Figure 1 (Step 4B), mammals cannot synthesize IPC; instead, they produce SM using two major SM synthases [8] encoded by SM1 and SM2 (Table 1, Step 4).

In yeasts, IPC is found as a lipid in complex SLs [9] or in mature GPI-anchored surface proteins. It is composed of a sphingoid-base with N-acylated C18:0–C26:0 fatty acids [18, 77, 78]. In T. cruzi, IPC is found in the majority of GIPLs (in epimastigotes) [67–70], the GPI anchors of Ssp4 antigen (in amastigotes) [54], trans-sialidase and Tc-85 glycoprotein (in trypomastigotes) [79, 80], mucins and 1G7-Ag (in metacyclic forms) [71, 81, 82]. In replacement of IPC, GPI-anchored proteins contain only 1-O-hexadecylglycerol-based PIs [71, 72, 81–84]. The lipid moiety of GIPLs also includes a small amount (2–8%) of 1-O-hexadecyl-2-acyl-PIs [72, 85]. Thus, there is a developmentally regulated expression [54] and distribution of ceramide in T. cruzi GPI-anchored components. In T. brucei bloodstream forms, GPI-protein anchors contain dimyristoylglycerol, whereas in Leishmania, these anchors are mainly composed of sn-1-alkyl-2-acyl-PI or sn-1-alkyl-2-lyso-PI [14]. In Leishmania, IPC is present together with other SLs and sterols in organized lipid rafts [86] but it is never found attached to any GPI-anchored protein or GIPL [14]. In T. brucei, IPC has been found in insect-stage procyclic forms (PCFs), but its role remains unclear [38, 60, 87].

Another SL that is produced by T. brucei is SM. This lipid has been detected using a combination of methods, including metabolic labeling, enzyme treatments and high-resolution mass spectrometry, in both insect and mammalian stages of the parasite [61, 88]. The relative amount of SM in PCF cells is significantly lower than that in blood-stream forms (BSFs) [87], probably because the ceramide in BSFs is used in conjunction with PC to form SM, whereas in PCFs ceramide is also used to form IPC from PI [38, 61]. In BSF parasites of T. brucei, the unusual phosphosphingolipid ethanolamine phosphorylceramide (EPC, Figure 1, Step 4C) was detected for the first time by Sutterwala and colleagues [61]. Its presence was later confirmed by a lipidomic analysis [87].

The IPC synthases of L. major (LmIPCS) and T. cruzi (TcIPC1 and TcIPC2) and the SL synthase (SLS) family of T. brucei (TbSLS1-4) were initially identified in the GeneDB database based on sequence similarity [4]. These are shown in Table 1 (Step 4). The TbSLS genes are organized in a unique linear tandem array. All Tritryp sequences are predicted to have six trans-membrane (TM) domains and two luminal motifs that likely constitute the catalytic domain. Each Tritryp sequence contains histidine and aspartate residues that mediate nucleophilic attack on the lipid phosphate ester bonds. This predicted topology more closely resembles that of mammalian SMSs, which also have the signature motifs (D1-4), than the fungal IPC synthase, which contains only the D3-4 motifs and is encoded by AUR1/KEI1 genes [4, 8, 11, 61, 62].

All the TbSLSs genes are constitutively expressed in both stages of the life-cycle (PCF and BSF). Simultaneous knockdown of the four TbSLS genes using a pan-specific RNAi showed that the TbSLS gene products are required for cell viability [61]. The activity of each of the TbSLS gene products has been validated with genetic and biochemical analyses, as well as with a recently developed cell-free system for the synthesis of active polytopic membrane proteins. TbSLS1p is an IPC synthase and is expressed in PCFs, whereas TbSLS2p is an EPC synthase, and TbSLS3p and TbSLS4p are bifunctional SM/EPC synthases [61, 62]. Sequence alignments and site-specific mutagenesis indicate that the specific phospholipid head group donor depends on subtle differences in active site residues [62]. Taken together, the existing data support the ability of T. brucei to synthesize IPC (Figure 1, Step 4A), SM (Figure 1, Step 4B) and EPC (Figure 1, Step 4C).

The Lederkremer's group was the first to identify IPC in T. cruzi epimastigotes [57], trypomastigotes [58] and amastigotes [54, 75]. IPC synthase activity was initially found in the microsomal membranes of all life-cycle stages of T. cruzi [59]. The TcIPC synthase activity is consistent with the proposed reaction scheme for IPC synthase in fungi and plants, though there are differences in the optimal pH conditions, metal requirements and detergent preferences [59]. The classical inhibitors of fungal IPC synthase, rustmicin and AbA, do not inhibit T. cruzi IPC synthase in vitro (over the range of 0.9–7 μM) and do not affect the proliferation of epimastigotes in culture (>40 μM). However, AbA inhibits both the proliferation of amastigotes inside macrophages and the release of trypomastigotes from these cells in a dose-dependent manner [59]. The reduction in intracellular proliferation can be partially attributed to the effect of this drug on macrophage function, diminishing phagocytic capacity and nitric oxide production [59].

Similar results have been obtained with AbA in T. brucei SL synthesis [62], suggesting that the IPC synthase enzyme is not the main target of AbA in parasites. Nonetheless, TbSLSs remain potential chemotherapeutic targets, as T. brucei is critically dependent on de novo synthesis of sphingolipids to survive. Mass spectrometry of lipids extracted from AbA-treated L. major promastigotes has shown that there is no effect on IPC synthesis, unless very high concentrations of AbA are administered (>5.0 μM) [29].

5. The Lipid Remodeling Reactions

More than 20 genes involved in GPI biosynthesis and protein attachment have been identified. In most cases, these genes are conserved from yeast to mammalian cells [18, 89]. As in mammals, yeasts, T. brucei and Leishmania, the first steps of GPI anchor biosynthesis in T. cruzi do not include a ceramide precursor [90, 91]. Thus, ceramide is probably added during a later remodeling step in T. cruzi [75, 90, 91], as in yeasts [78, 92, 93]. Although there are differences in the ceramide composition, remodeling in yeast happens after the attachment of the GPI anchor to the proteins, whereas in T. cruzi, remodeling may occur on the GPI protein anchors and/or GIPLs.

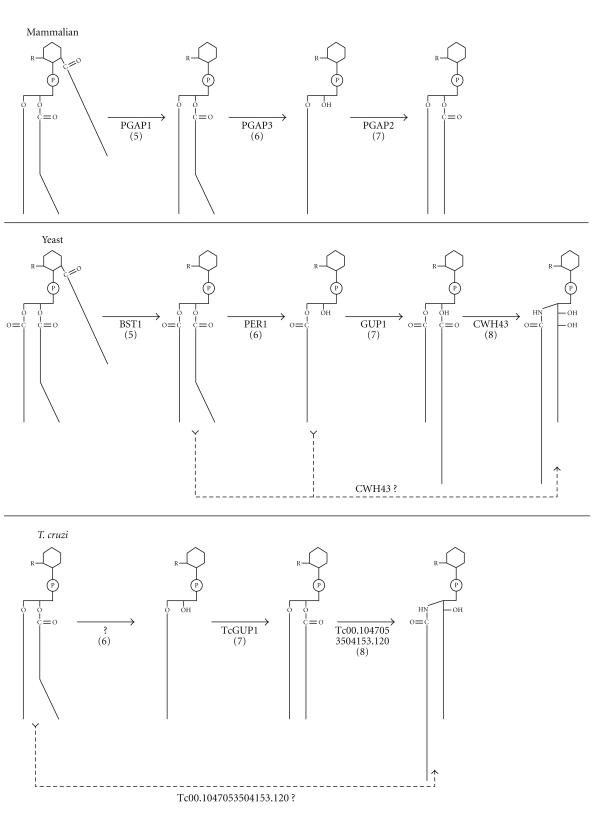

Lipid remodeling of GPI-anchored proteins has been studied in fungi, mammals and T. brucei [20, 21]. The four most important enzymes and the genes involved in this process are listed in Table 1 (Steps 5–8); the lipid remodeling reactions are depicted in a simplified scheme in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Lipid remodeling pathways in mammals, yeast and T. cruzi. “R” represents the entire glycan structure of each GPI anchor precursor linked to a protein. Although this assumption has been validated in mammals (top panel) and yeast (middle panel), no such experimental data are available for T. cruzi (bottom panel). Each step (in parentheses) has corresponding entries in Table 1.

In mammals, the first reaction is a deacylation to remove the fatty acid linked to position C-2 of the GPI anchor inositol ring (Table 1 and Figure 2, Step 5). This reaction is catalyzed by PGAP1p (postGPI attachment to protein 1) and occurs before the GPI-attached proteins leave the ER, as it is critical for efficient transit of GPI anchored proteins to the Golgi [94]. The second reaction is the removal of the unsaturated acyl chain from the sn-2 position of the alkyl-acyl-glycerolipid to form a lyso-GPI (Table 1 and Figure 2, Step 6). This reaction is catalyzed by PGAP3p [95]. The final reaction in mammals is the transfer of a saturated acyl chain (C18:0) to the sn-2 position of the lyso-GPI species (Table 1 and Figure 2, Step 7). PGAP2p is one protein involved in this process [96], but it is probably not an acyl-transferase because it has no homology to acyltransferases [21].

Mature GPI-anchored proteins in yeasts contain two different types of lipid moieties [77, 78, 92]. The first is a diacylglycerol with a C26:0 fatty acid at the sn-2 position. The second is a ceramide containing mainly C18:0 phytosphingosine and a C26:0 fatty acid [78]. In both cases, the C26:0 fatty acid may be 2-hydroxylated. As mentioned above for mammals, lipid remodeling of the yeast GPI-anchored proteins starts in the ER with the removal of the fatty acid linked to the C-2 position of the GPI anchor inositol ring (Table 1 and Figure 2, Step 5). This reaction is catalyzed by the PGAP1p orthologue BST1p [94]. Unlike mammals, which have a sn-1-alkyl-2-acyl-glycerolipid attached to the GPI, yeasts have a diacyl-glycerolipid (Figure 2). The next step is the removal of the C18:1 fatty acid at the sn-2 position of diacylglycerol to form a lyso-GPI (Figure 2, Step 6). This reaction is performed by GPI phospholipase A2 (GPI-PLA2), which requires PER1p (Table 1, Step 6) for its activity [94, 95]. Next, the free sn-2 position is filled with a C26:0 fatty acid (Figure 2, Step 7) by an acyl-transferase called GUP1p [97]. Finally, the diacylglycerol lipid moiety is replaced by a ceramide (Figure 2, Step 8) with C18:0 phytosphingosine and a hydroxy-C26:0 fatty acid [78]. It has been reported recently that CWH43p (Table 1, Step 8) is responsible for this replacement [98, 99]. Indeed, the exchange reaction requires the C-terminus of CWH43p, and the association of the CWH43p-N with the CWH43p-C enhances the lipid remodeling reaction [99]. The alignment of CWH43p to its homologues in fission yeast (Shizosaccharomyces pombe), filamentous fungi, mice and humans has identified conserved residues that are important for the lipid remodeling function, including H802, D862 and R882, and protein stability (G57) [97, 99]. The N-terminal region of yeast CWH43 has a FRAG1 domain (Figure 3), which is also present in PGAP2p and is thought to act as a protein interaction motif that enhances stability under conditions of replicative stress [21]. The C-terminal region of CWH43 also has a DNase I-like motif (Figure 3) that is found in Isc1p, Inp51p, Inp52p, Inp53p and Inp54p. Isc1p is an inositol phosphosphingolipid phospholipase C [20], and the Inp51/52/53/54 proteins are phosphoinositol phosphatases [21]. This motif may be involved in the recognition of inositol phosphate, in which case the DNase I-like region in the C-terminal domain of CWH43p could be important for the recognition of PI on the GPI anchor.

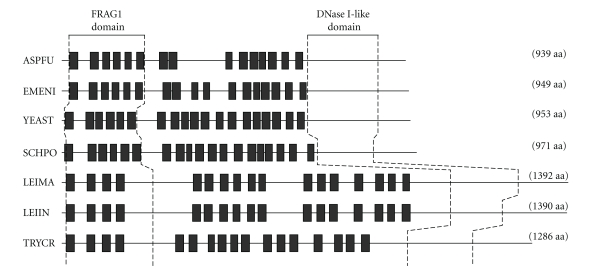

Figure 3.

Comparison of the CWH43 proteins from fungi and Tritryps. The amino acid sequences of CWH43 proteins from Aspergillus fumigatus (ASPFU), Emericella nidulans (EMENI), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (YEAST) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (SCHPO) were compared with the putative CWH43p candidates from Leishmania major (LEIMA), Leishmania infantum (LEIIN) and Trypanosoma cruzi (TRYCR). Thick horizontal bars indicate the relative positions of the membrane-spanning domains as predicted by the TMHMM Server. Dashed lines delineate the relative positions of the FRAG1 and DNase I-like domains, which are located at the N- and C-terminus, respectively.

The sequential remodeling reactions mentioned above comprise one of the three possible pathways for lipid remodeling in yeast (Figure 2, compare full with dashed lines). Another may be a divergent pathway, in which the lyso-GPI generated by PER1p is a direct substrate for the ceramide remodeling activity of CWH43p [99]. CWH43p could be involved in the direct exchange of glycerolipids containing an unsaturated fatty acid for the ceramide moiety. This third alternative is proposed to function as a backup if the first one, which is mediated by PER1p and GUP1p, is defective [94, 98, 99].

Acyl exchange also occurs in T. brucei, but in this organism, the remodeling happens before (during GPI anchor biosynthesis) and after the GPI anchor precursor is transferred onto the protein [100]. T. brucei contains two different GPI deacylation/reacylation pathways. One pathway (termed lipid remodeling) acts on lipid A' (a GPI anchor biosynthetic precursor containing a sn-2-heterogenous fatty acid) to generate lipid A (containing sn-1, 2-dimyristoylglycerol), creating the intermediates lipid θ (lyso-GPI) and lipid A” (sn-1-stearoyl-2-myristoylglycerol). The other pathway (termed lipid exchange) acts on both GPI proteins and lipid A and exchanges the original myristate for another myristate [100, 101]. The acyl transferase GUP1p has homologues encoded in the genomes of T. brucei and T. cruzi (Table 1, Step 7). In T. brucei, TbGUP1p is required for the acylation of lipid θ (lyso-PI) to generate lipid A” (sn-1-stearoyl-2-myristoylglycerol) in the remodeling of GPI lipids [100, 101]. Although the remodeling of GPI anchors is important in several species to firmly anchor GPI proteins onto lipid bilayers and direct them to the correct cellular compartments and membrane domains [95], GPI lipid remodeling is not important for the stability and surface expression of the essential variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) [101]. The lack of GPI remodeling could be compensated in vivo by the myristate exchange pathway [100].

Like TbGUP1p, the T. cruzi GUP1p (Table 1, Step 7) can reacylate lyso-GPI anchors (Figure 2, Step 7), indicating that a similar pathway mediated by GUP1p is present in both yeasts and protozoa [97, 101]. Although several putative GUP1 orthologues have been found in Leishmania (Table 1, Step 7), there is no experimental evidence for the existence of this kind of lipid remodeling in these parasites. Additionally, IPC has not been found to be linked to GPI anchors or GIPLs [14]. Therefore, targeted deletion studies in Leishmania could be used to determine the participation and function of these SBPs genes [29].

In T. cruzi, lipid remodeling occurs most likely as depicted in Figure 2. Unlike what has been described for mammals and yeasts, in this organism, the GPI anchor precursor molecule that is attached to the proteins is not acylated at position C-2 of the inositol ring [90]. Nonetheless, a putative TbGPIdeAc orthologue can be found in the T. cruzi genome database (Table 1, Step 5). In T. cruzi, intermediate GPI anchor precursors combine acylated and nonacylated inositol, as in T. brucei [90]. Thus, the putative orthologue (Tc00.1047053508153.1040) could be involved in deacylation during GPI biosynthesis. Although they are not acylated at the inositol ring, the GPI anchor precursors (either before or after attachment to proteins) contain a sn-1-alkyl-2-acyl-glycerolipid moiety [90] (Figure 2). However, Lederkremer's group has also detected a GPI-anchor precursor in T. cruzi that contains a mono-acyl-glycerol moiety [91]. There are no orthologues for the mammalian PGAP3p or yeast PER1p in the Tritryp genomes (Table 1, Step 6). It has been shown that T. cruzi lysates contain a PLA2 activity that uses PI as a substrate [74], but it is not known whether this activity can also act on GPI-containing substrates. As mentioned above, TcGUP1p (Figure 2 and Table 1, Step 7) can reacylate lyso-GPI substrates [99, 101], but it is not clear which of the putative homologues encoded in the genome was used in those studies (Table 1, Step 7).

A putative orthologue of yeast CWH43p has been identified in the genomes of T. cruzi (Tc00.1047053504153.120), L. major (LmjF27.1770) (Table 1, Step 8) and L. infantum (LinJ27_V3.1670). This protein could have the ceramide remodeling activity that is supposed to exchange the sn-1-alkyl-2-acyl-glycerolipid of the GPI for a ceramide moiety in T. cruzi (Figure 2, Step 8 continuous or dashed lines). As already mentioned, no information is available on the function of these putative orthologues in Leishmania since ceramide is not found in their GPI anchors.

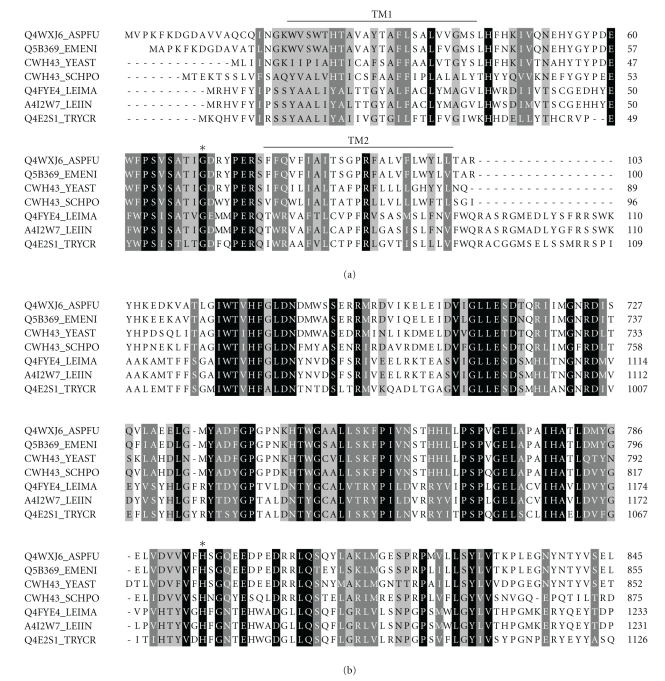

To learn more about the CWH43p orthologues in Tritryps, a multiple sequence alignment was prepared to compare these sequences with “bonafide” fungal CWH43p sequences. The results are presented in Figures 3 and 4. As shown in Figure 3, the Tritryp orthologues contain as many TM domains as the fungal CWH43p sequences. However, these domains have a greater distribution along the length of the sequences of T. cruzi and Leishmania. In addition, all the sequences have a highly conserved FRAG1 domain at the N-terminus and a DNase I-like domain at the C-terminus (Figure 3). A closer view of each of these conserved domains is shown in Figure 4. The FRAG1 domain has a high degree of identity across all sequences. The conserved residue G59 (G57 in yeast), which is essential for catalysis [99, 101], is located between the first and second TM domains (Figure 4(a), “∗”). A high degree of identity is also apparent in the DNase I-like domain at the C-terminus. The catalytically important residue H1076 (H802 in yeast) is conserved across all sequences (Figure 4(b), “∗”). Taken together, these data indicate that T. cruzi encodes a putative ceramide remodeling enzyme, which is essential in fungi and has no homologues in mammals.

Figure 4.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of CWH43p homologues. Amino acid sequences of Aspergillus fumigatus (Q4WXJ6_ASPFU), Emericella nidulans (Q5B369_EMENI), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (CWH43_YEAST) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (CWH43_SCHPO) proteins were aligned with the sequences of putative CWH43p candidates in Leishmania major (Q4FYE4_LEIMA), Leishmania infantum (A4I2W7_LEIIN) and Trypanosoma cruzi (Q4B2S1_TRYCR) using ClustalW. Identical amino acids are in reverse type, and conserved residues are shaded accordingly. The FRAG1 domain is shown in (a) the DNase I-like domain is shown in (b) Asterisks (∗) indicate the relative positions of amino acid residues that are essential for ceramide remodeling catalysis. TM, transmembrane stretches.

6. Concluding Remarks

In T. cruzi, GPI-anchored glycoconjugates such as mucins, trans-sialidases, gp82/90 glycoproteins and GIPLs may extensively coat the plasma membrane of the parasite. These glycoconjugates are involved in many aspects of the host-parasite interaction, such as adhesion and invasion of host cells, modulation and evasion from the host immune response, and pathogenesis [66, 67, 83]. In addition, the GPI anchors, or certain parts of them, seem to act as strong proinflammatory molecules during the immune response against this parasite [66]. Therefore, mechanisms that interfere with the surface expression of GPI-anchored proteins and GIPLs or with the biosynthesis of GPI anchors are very attractive targets for new therapies against Chagas disease. Here, we discussed two novel targets in the SBPs of T. cruzi: the IPC synthase and ceramide remodeling. Because fungicidal inhibitors of IPC synthase activity do not affect the trypanosomal enzyme, the identification of novel inhibitors of this enzyme should be a goal of future research. This research direction could require the development of novel HTPS methods, such as the plate-based assay for screening Leishmania IPC synthase inhibitors that was recently developed by Mina and colleagues [102]. Unfortunately, recombinant parasite IPC synthase is prepared by overexpression in a fungal heterologous system, which has completely different optimal enzyme conditions and extra cofactors that would affect inhibition by novel candidates. Biochemical enzymatic assays have not been developed for ceramide remodeling, but recent advances have been made in monitoring the in vitro incorporation of ceramides into GPI-anchored proteins in S. cerevisiae [103]. These methods could be developed for use in T. cruzi.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ) (research Grant no. 477124/2009-7 to N. Heise) and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) (research Grant E-26/110.917/2009 to N. Heise). C. M. Koeller is the recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship from CNPQ.

References

- 1.Futerman AH, Hannun YA. The complex life of simple sphingolipids. EMBO Reports. 2004;5(8):777–782. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2008;9(2):139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickson RC. Sphingolipid functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison to mammals. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1998;67:27–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denny PW, Shams-Eldin H, Price HP, Smith DF, Schwarz RT. The protozoan inositol phosphorylceramide synthase: a novel drug target that defines a new class of sphingolipid synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(38):28200–28209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600796200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pankova-Kholmyansky I, Flescher E. Potential new antimalarial chemotherapeutics based on sphingolipid metabolism. Chemotherapy. 2006;52(4):205–209. doi: 10.1159/000093037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki E, Tanaka AK, Toledo MS, Levery SB, Straus AH, Takahashi HK. Trypanosomatid and fungal glycolipids and sphingolipids as infectivity factors and potential targets for development of new therapeutic strategies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1780(3):362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2008;9(2):112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huitema K, Van Den Dikkenberg J, Brouwers JFHM, Holthuis JCM. Identification of a family of animal sphingomyelin synthases. EMBO Journal. 2004;23(1):33–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lester RL, Dickson RC. Sphingolipids with inositolphosphate-containing head groups. Advances in lipid research. 1993;26:253–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine TP, Wiggins CAR, Munro S. Inositol phosphorylceramide synthase is located in the Golgi apparatus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11(7):2267–2281. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagiec MM, Nagiec EE, Baltisberger JA, Wells GB, Lester RL, Dickson RC. Sphingolipid synthesis as a target for antifungal drugs. Complementation of the inositol phosphorylceramide synthase defect in a mutant strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by the AUR1 gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(15):9809–9817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takesaiko K, Kuroda H, Inoue T, et al. Biological properties of aureobasidin A, a cyclic depsipeptide antifungal antibiotic. Journal of Antibiotics. 1993;46(9):1414–1420. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandala SM, Thornton RA, Milligan J, et al. Rustmicin, a potent antifungal agent, inhibits sphingolipid synthesis at inositol phosphoceramide synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(24):14942–14949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConville MJ, Ferguson MAJ. The structure, biosynthesis and function of glycosylated phosphatidylinositols in the parasitic protozoa and higher eukaryotes. Biochemical Journal. 1993;294(2):305–324. doi: 10.1042/bj2940305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leidich SD, Drapp DA, Orlean P. A conditionally lethal yeast mutant blocked at the first step in glycosyl phosphatidylinositol anchor synthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(14):10193–10196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagamune K, Nozaki T, Maeda Y, et al. Critical roles of glycosylphosphatidylinositol for Trypanosoma brucei. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(19):10336–10341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180230697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nozaki M, Ohishi K, Yamada N, Kinoshita T, Nagy A, Takeda J. Developmental abnormalities of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor-deficient embryos revealed by Cre/IoxP system. Laboratory Investigation. 1999;79(3):293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pittet M, Conzelmann A. Biosynthesis and function of GPI proteins in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1771(3):405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinoshita T, Fujita M, Maeda Y. Biosynthesis, remodelling and functions of mammalian GPI-anchored proteins: recent progress. Journal of Biochemistry. 2008;144(3):287–294. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujita M, Jigami Y. Lipid remodeling of GPI-anchored proteins and its function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1780(3):410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujita M, Kinoshita T. Structural remodeling of GPI anchors during biosynthesis and after attachment to proteins. FEBS Letters. 2010;584(9):1670–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vickerman K. Developmental cycles and biology of pathogenic trypanosomes. British Medical Bulletin. 1985;41(2):105–114. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham AC. Parasitic adaptive mechanisms in infection by Leishmania. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2002;72(2):132–141. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2002.2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pepin J. Combination therapy for sleeping sickness: a wake-up call. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;195(3):311–313. doi: 10.1086/510540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dias JCP, Silveira AC, Schofield CJ. The impact of Chagas disease control in Latin America—a review. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97(5):603–612. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moncayo A, Ortiz Yanine MI. An update on Chagas disease (human American trypanosomiasis) Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 2006;100(8):663–677. doi: 10.1179/136485906X112248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obeid LM, Okamoto Y, Mao C. Yeast sphingolipids: metabolism and biology. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2002;1585(2-3):163–171. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanada K. Serine palmitoyltransferase, a key enzyme of sphingolipid metabolism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2003;1632(1–3):16–30. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang K, Showalter M, Revollo J, Hsu FF, Turk J, Beverley SM. Sphingolipids are essential for differentiation but not growth in Leishmania. EMBO Journal. 2003;22(22):6016–6026. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denny PW, Smith DF. Rafts and sphingolipid biosynthesis in the kinetoplastid parasitic protozoa. Molecular Microbiology. 2004;53(3):725–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang K, Hsu FF, Scott DA, Docampo R, Turk J, Beverley SM. Leishmania salvage and remodelling of host sphingolipids in amastigote survival and acidocalcisome biogenesis. Molecular Microbiology. 2005;55(5):1566–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang K, Pompey JM, Hsu FF, et al. Redirection of sphingolipid metabolism toward de novo synthesis of ethanolamine in Leishmania. EMBO Journal. 2007;26(4):1094–1104. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denny PW, Goulding D, Ferguson MAJ, Smith DF. Sphingolipid-free Leishmania are defective in membrane trafficking, differentiation and infectivity. Molecular Microbiology. 2004;52(2):313–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanada K, Nishijima M, Kiso M, et al. Sphingolipids are essential for the growth of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Restoration of the growth of a mutant defective in sphingoid base biosynthesis by exogenous sphingolipids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(33):23527–23533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pinto WJ, Wells GW, Lester RL. Characterization of enzymatic synthesis of sphingolipid long-chain bases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: mutant strains exhibiting long-chain-base auxotrophy are deficient in serine palmitoyltransferase activity. Journal of Bacteriology. 1992;174(8):2575–2581. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2575-2581.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyake Y, Kozutsumi Y, Nakamura S, Fujita T, Kawasaki T. Serine palmitoyltransferase is the primary target of a sphingosine-like immunosuppressant, ISP-1/myriocin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1995;211(2):396–403. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutterwala SS, Creswell CH, Sanyal S, Menon AK, Bangs JD. De novo sphingolipid synthesis is essential for viability, but not for transport of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, in African trypanosomes. Eukaryotic Cell. 2007;6(3):454–464. doi: 10.1128/EC.00283-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fridberg A, Olson CL, Nakayasu ES, Tyler KM, Almeida IC, Engman DM. Sphingolipid synthesis is necessary for kinetoplast segregation and cytokinesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;121(4):522–535. doi: 10.1242/jcs.016741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beeler T, Bacikova D, Gable K, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae TSC10/YBR265W gene encoding 3-ketosphinganine reductase is identified in a screen for temperature-sensitive suppressors of the Ca2+-sensitive csg2Δ mutant. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(46):30688–30694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kihara A, Igarashi Y. FVT-1 is a mammalian 3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase with an active site that faces the cytosolic side of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(47):49243–49250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Sayed NM, Myler PJ, Bartholomeu DC, et al. The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of chagas disease. Science. 2005;309(5733):409–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1112631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perry DK, Hannun YA. The role of ceramide in cell signaling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;1436(1-2):233–243. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hannun YA, Luberto C. Ceramide in the eukaryotic stress response. Trends in Cell Biology. 2000;10(2):73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. The ceramide-centric universe of lipid-mediated cell regulation: stress encounters of the lipid kind. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(29):25847–25850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morell P, Radin NS. Specificity in ceramide biosynthesis from long chain bases and various fatty acyl coenzyme A’s by brain microsomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1970;245(2):342–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akanuma H, Kishimoto Y. Synthesis of ceramides and cerebrosides containing both alpha-hydroxy and nonhydroxy fatty acids from lignoceroyl-CoA by rat brain microsomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1979;254(4):1050–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mao C, Xu R, Bielawska A, Obeid LM. Cloning of an alkaline ceramidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. An enzyme with reverse (CoA-independent) ceramide synthase activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(10):6876–6884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mao C, Xu R, Bielawska A, Szulc ZM, Obeid LM. Cloning and characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae alkaline ceramidase with specificity for dihydroceramide. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(40):31369–31378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grilley MM, Stock SD, Dickson RC, Lester RL, Takemoto JY. Syringomycin action gene SYR2 is essential for sphingolipid 4- hydroxylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(18):11062–11068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guillas I, Kirchman PA, Chuard R, et al. C26-CoA-dependent ceramide synthesis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is operated by Lag1p and Lac1p. EMBO Journal. 2001;20(11):2655–2665. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schorling S, Vallée B, Barz WP, Riezman H, Oesterhelt D. Lag1p and Lac1p are essential for the Acyl-CoA-dependent ceramide synthase reaction in Saccharomyces cerevisae. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2001;12(11):3417–3427. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mizutani Y, Kihara A, Igarashi Y. Mammalian Lass6 and its related family members regulate synthesis of specific ceramides. Biochemical Journal. 2005;390(1):263–271. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vallée B, Riezman H. Lip1p: a novel subunit of acyl-CoA ceramide synthase. EMBO Journal. 2005;24(4):730–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bertello LE, Andrews NW, De Lederkremer RM. Developmentally regulated expression of ceramide in Trypanosoma cruzi. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1996;79(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quiñones W, Urbina JA, Dubourdieu M, Concepción JL. The glycosome membrane of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes: protein and lipid composition. Experimental Parasitology. 2004;106(3-4):135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaneshiro ES, Jayasimhulu K, Lester RL. Characterization of inositol lipids from Leishmania donovani promastigotes: identification of an inositol sphingophospholipid. Journal of Lipid Research. 1986;27(12):1294–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertello LE, Goncalvez MF, Colli W, De Lederkremer RM. Structural analysis of inositol phospholipids from Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigote forms. Biochemical Journal. 1995;310(1):255–261. doi: 10.1042/bj3100255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uhrig ML, Couto AS, Colli W, De Lederkremer RM. Characterization of inositolphospholipids in Trypanosoma cruzi trypmastigote forms. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1996;1300(3):233–239. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(96)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Figueiredo JM, Dias WB, Mendonça-Previato L, Previato JO, Heise N. Characterization of the inositol phosphorylceramide synthase activity from Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochemical Journal. 2005;387(2):519–529. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Güther MLS, Lee S, Tetley L, Acosta-Serrano A, Ferguson MAJ. GPI-anchored proteins and free GPI glycolipids of procyclic form Trypanosoma brucei are nonessential for growth, are required for colonization of the tsetse fly, and are not the only components of the surface coat. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17(12):5265–5274. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sutterwala SS, Hsu FF, Sevova ES, et al. Developmentally regulated sphingolipid synthesis in African trypanosomes. Molecular Microbiology. 2008;70(2):281–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sevova ES, Goren MA, Schwartz KJ, et al. Cell-free synthesis and functional characterization of sphingolipid synthases from parasitic trypanosomatid protozoa. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(27):20580–20587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Figueiredo JM, Rodrigues DC, Silva RCMC, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of the ceramide synthase from Trypanosoma cruzi. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.12.006. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mandala SM, Thornton RA, Frommer BR, et al. The discovery of australifungin, a novel inhibitor of sphinganine N-acyltransferase from Sporormiella australis producing organism, fermentation, isolation, and biological activity. Journal of Antibiotics. 1995;48(5):349–356. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu WI, McDonough VM, Nickels JT, et al. Regulation of lipid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by fumonisin B1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(22):13171–13178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.DosReis GA, Peçanha LMT, Bellio M, Previato JO, Mendonça-Previato L. Glycoinositol phospholipids from Trypanosoma cruzi transmit signals to the cells of the host immune system through both ceramide and glycan chains. Microbes and Infection. 2002;4(9):1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01616-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Previato JO, Wait R, Jones C, et al. Glycoinositolphospholipids (GIPL) from Trypanosoma cruzi: structure, biosynthesis and immunology. Advances in Parasitology. 2004;56:1–41. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(03)56001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Lederkremer RM, Lima C, Ramirez MI, Casal OL. Structural features of the lipopeptidophosphoglycan from Trypanosoma cruzi common with the glycophosphatidylinositol anchors. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1990;192(2):337–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Lederkremer RM, Lima C, Ramirez MI, Ferguson MAJ, Homans SW, Thomas-Oates J. Complete structure of the glycan of lipopeptidophosphoglycan from Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(35):23670–23675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Previato JO, Gorin PAJ, Mazurek M, et al. Primary structure of the oligosaccharide chain of lipopeptidophosphoglycan of epimastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265(5):2518–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Serrano AA, Schenkman S, Yoshida N, Mehlert A, Richardson JM, Ferguson MAJ. The lipid structure of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored mucin- like sialic acid acceptors of Trypanosoma cruzi changes during parasite differentiation from epimastigotes to infective metacyclic trypomastigote forms. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(45):27244–27253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakayasu ES, Yashunsky DV, Nohara LL, Torrecilhas ACT, Nikolaev AV, Almeida IC. GPIomics: global analysis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored molecules of Trypanosoma cruzi. Molecular Systems Biology. 2010;5(261):1–135. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee SH, Stephens JL, Paul KS, Englund PT. Fatty acid synthesis by elongases in trypanosomes. Cell. 2006;126(4):691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bertello LE, Alves MJM, Colli W, De Lederkremer RM. Evidence for phospholipases from Trypanosoma cruzi active on phosphatidylinositol and inositolphosphoceramide. Biochemical Journal. 2000;345(1):77–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Salto ML, Bertello LE, Vieira M, Docampo R, Moreno SNJ, De Lederkremer RM. Formation and remodeling of inositolphosphoceramide during differentiation of Trypanosoma cruzi from trypomastigote to amastigote. Eukaryotic Cell. 2003;2(4):756–768. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.4.756-768.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sato K, Noda Y, Yoda K. Kei1: a novel subunit of inositolphosphorylceramide synthase, essential for its enzyme activity and golgi localization. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20(20):4444–4457. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fankhauser C, Homans SW, Thomas-Oates JE, et al. Structures of glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchors from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(35):26365–26374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sipos G, Reggiori F, Vionnet C, Conzelmann A. Alternative lipid remodelling pathways for glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO Journal. 1997;16(12):3494–3505. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Agusti R, Couto AS, Campetella OE, Frasch ACC, De Lederkremer RM. The trans-sialidase of Trypanosoma cruzi is anchored by two different lipids. Glycobiology. 1997;7(6):731–735. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.6.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Couto AS, De Lederkremer RM, Colli W, Alves MJM. The glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor of the trypomastigote-specific Tc-85 glycoprotein from Trypanosoma cruzi. Metabolic-labeling and structural studies. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1993;217(2):597–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guther MLS, De Almeida MLC, Yoshida N, Ferguson MAJ. Structural studies on the glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchor of Trypanosoma cruzi 1G7-antigen. The structure of the glycan core. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(10):6820–6828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heise N, Lucia Cardoso De Almeida M, Ferguson MAJ. Characterization of the lipid moiety of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor of Trypanosoma cruzi 1G7-antigen. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1995;70(1-2):71–84. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00009-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schenkman S, Ferguson MAJ, Heise N, Cardoso De Almeida ML, Mortara RA, Yoshida N. Mucin-like glycoproteins linked to the membrane by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor are the major acceptors of sialic acid in a reaction catalyzed by trans-sialidase in metacyclic forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1993;59(2):293–304. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90227-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Previato JO, Jones C, Xavier MT, et al. Structural characterization of the major glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane-anchored glycoprotein from epimastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi Y-strain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(13):7241–7250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.De Lederkremer RM, Lima CE, Ramirez MI, Goncalvez MF, Colli W. Hexadecylpalmitoylglycerol or ceramide is linked to similar glycophosphoinositol anchor-like structures in Trypanosoma cruzi. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1993;218(3):929–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Denny PW, Field MC, Smith DF. GPI-anchored proteins and glycoconjugates segregate into lipid rafts in Kinetoplastida. FEBS Letters. 2001;491(1-2):148–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Richmond GS, Gibellini F, Young SA, et al. Lipidomic analysis of bloodstream and procyclic form Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitology. 2010;137(9):1357–1392. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Signorell A, Gluenz E, Rettig J, et al. Perturbation of phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis affects mitochondrial morphology and cell-cycle progression in procyclic-form Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular Microbiology. 2009;72(4):1068–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Orlean P, Menon AK. GPI anchoring of protein in yeast and mammalian cells, or: how we learned to stop worrying and love glycophospholipids. Journal of Lipid Research. 2007;48(5):993–1011. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heise N, Raper J, Buxbaum LU, Peranovich TMS, De Almeida MLC. Identification of complete precursors for the glycosylphosphatidylinositol protein anchors of Trypanosoma cruzi. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(28):16877–16887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bertello LE, Alves MJM, Colli W, De Lederkremer RM. Inositolphosphoceramide is not a substrate for the first steps in the biosynthesis of glycoinositolphospholipids in Trypanosoma cruzi. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2004;133(1):71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Reggiori F, Canivenc-Gansel E, Conzelmann A. Lipid remodeling leads to the introduction and exchange of defined ceramides on GPI proteins in the ER and Golgi of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO Journal. 1997;16(12):3506–3518. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reggiori F, Conzelmann A. Biosynthesis of inositol phosphoceramides and remodeling of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are mediated by different enzymes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(46):30550–30559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fujita M, Umemura M, Yoko-O T, Jigami Y. PER1 is required for GPI-phospholipase A2 activity and involved in lipid remodeling of GPI-anchored proteins. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17(12):5253–5264. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maeda Y, Tashima Y, Houjou T, et al. Fatty acid remodeling of GPI-anchored proteins is required for their raft association. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18(4):1497–1506. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tashima Y, Taguchi R, Murata C, Ashida H, Kinoshita T, Maeda Y. PGAP2 is essential for correct processing and stable expression of GPI-anchored proteins. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17(3):1410–1420. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bosson R, Jaquenoud M, Conzelmann A. GUP1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes an O-acyltransferase involved in remodeling of the GPI anchor. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17(6):2636–2645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ghugtyal V, Vionnet C, Roubaty C, Conzelmann A. CWH43 is required for the introduction of ceramides into GPI anchors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;65(6):1493–1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Umemura M, Fujita M, Yoko-O T, Fukamizu A, Jigami Y. Saccharomyces cerevisiae CWH43 is involved in the remodeling of the lipid moiety of GPI anchors to ceramides. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18(11):4304–4316. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Paul KS, Jiang D, Morita YS, Englund PT. Fatty acid synthesis in African trypanosomes: a solution to the myristate mystery. Trends in Parasitology. 2001;17(8):381–387. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(01)01984-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jaquenoud M, Pagac M, Signorell A, et al. The Gup1 homologue of Trypanosoma brucei is a GPI glycosylphosphatidylinositol remodelase. Molecular Microbiology. 2008;67(1):202–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mina JG, Mosely JA, Ali HZ, et al. A plate-based assay system for analyses and screening of the Leishmania major inositol phosphorylceramide synthase. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2010;42(9):1553–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bosson R, Guillas I, Vionnet C, Roubaty C, Conzelmann A. Incorporation of ceramides into Saccharomyces cerevisiae glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins can be monitored in vitro. Eukaryotic Cell. 2009;8(3):306–314. doi: 10.1128/EC.00257-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]