Abstract

Investigations into the functional modulation of the cardiac Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) by acute β-adrenoceptor/PKA stimulation have produced conflicting results. Here, we investigated (i) whether or not β-adrenoceptor activation/PKA stimulation activates current in rabbit cardiac myocytes under NCX-‘selective’ conditions and (ii) if so, whether a PKA-activated Cl−-current may contribute to the apparent modulation of NCX current (INCX). Whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments were conducted at 37 °C on rabbit ventricular and atrial myocytes. The β-adrenoceptor-activated currents both in NCX-‘selective’ and Cl−-selective recording conditions were found to be sensitive to 10 mM Ni2+. In contrast, the PKA-activated Cl− current was not sensitive to Ni2+, when it was activated downstream to the β-adrenoceptors using 10 μM forskolin (an adenylyl cyclase activator). When 10 μM forskolin was applied under NCX-selective recording conditions, the Ni2+-sensitive current did not differ between control and forskolin. These findings suggest that in rabbit myocytes: (a) a PKA-activated Cl− current contributes to the Ni2+-sensitive current activated via β-adrenoceptor stimulation under recording conditions previously considered selective for INCX; (b) downstream activation of PKA does not augment Ni2+-sensitive INCX, when this is measured under conditions where the Ni2+-sensitive PKA-activated Cl− current is not present.

Keywords: Cardiac myocyte, CFTR, NCX, Rabbit atrial myocyte, Rabbit ventricular myocyte, Whole-cell patch-clamp recording

1. Introduction

Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) proteins are widely distributed in different tissue types and play important roles in Na+ and Ca2+ ion homeostasis [1–3]. The stoichiometry of cardiac NCX1 exchange is generally held to be 3 Na+ ions for 1 Ca2+ ion such that the exchanger can function in both the ‘forward’ (Na+-entry, Ca2+-efflux) and ‘reverse’ (Na+-entry, Ca2+-efflux) modes, with the direction of transport determined by the intracellular and extracellular concentrations of the transported ions and transmembrane voltage gradient [1,4,5]. During ventricular action potentials (APs), initial membrane depolarisation may drive reverse-mode NCX activity, providing Ca2+ entry which can supplement that occurring via L-type calcium channels to facilitate calcium-induced calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) [6–8]. Subsequent forward mode exchange acts to extrude Ca2+ across the sarcolemmal membrane; consequently, along with SR Ca2+ reuptake, NCX1 activity is a major mechanism for restoring low diastolic [Ca2+]i levels [1,7]. Due to its stoichiometry, NCX activity is electrogenic and can influence AP profiles as well as cellular calcium handling [1,9]. Given these important roles, it is perhaps unsurprising that altered NCX activity can contribute to impaired excitation–contraction coupling and arrhythmogenesis in disease states [10]. The properties and regulation of NCX have been studied extensively by the voltage-clamp recording of NCX currents (INCX) in isolated cardiac myocytes under selective conditions in which other major cation currents (e.g., Ca2+, K+, Na+, Na+/K+ ATPase) have been removed or inhibited [11–15]. Extracellular Ni2+ is used conventionally to measure INCX as it blocks both the inward and the outward INCX reliably and reversibly with no preference for either mode of transport [11–13].

Although it has been established that NCX1 can be phosphorylated by protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) at sites residing in the large intracellular loop of the NCX protein [16–18], functional regulation of mammalian NCX1 by the β-adrenoceptor/PKA pathway is controversial, with both reports of no alteration [19–24] or upregulation [2,14,15,25–27] of NCX activity in different studies. For example, previous work from this laboratory has provided evidence for an increase in guinea-pig ventricular NCX activity at 37 °C through the β-adrenoceptor/PKA pathway [14,15,25]: the currents recorded during voltage-ramps in NCX recording conditions were stimulated by the β-adrenoceptor agonist, isoprenaline (ISO), by the adenylyl cyclase activator, forskolin, or by raised [cAMP]i and the rate of decay of caffeine-induced [Ca2+]i transients were accelerated by high [cAMP]i [15]. There are also reports of stimulation of NCX1 activity measured as 45Ca2+ uptake for both recombinant NCX1 and native rat ventricular NCX [28,29] and of INCX for swine ventricular myocytes [30,31]. On the other hand, it has been suggested that β-adrenoceptor activated changes in ionic current under INCX-‘selective’ conditions could result instead from activation of the CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator)-mediated ICl,PKA, as this current in guinea-pig myocytes has been reported to be sensitive to extracellular Ni2+-application when it is activated by isoprenaline, though not when activated by forskolin [24]. Furthermore, in a study of rabbit ventricular myocytes, Ginsburg and Bers reported no alteration to NCX activity estimated from caffeine-induced Ca2+-transient decay or of caffeine induced [Ca2+]i and inward INCX under perforated-patch conditions used to assess rate of Ca2+ extrusion via NCX [23]. Also, in the same study [23] rabbit ventricular INCX elicited by a voltage-ramp protocol was not enhanced by a brief period of isoprenaline application, the authors concluded that under those conditions rabbit ventricular INCX was not modulated by isoprenaline [23]. Differences between experimental preparations/species, protocols and conditions may contribute to the differing conclusions regarding PKA-modulation of NCX in the literature [5]. Consequently, the present study was undertaken to determine whether or not INCX from rabbit ventricular myocytes can be augmented by the β-adrenoceptor/PKA pathway during sustained application of voltage-ramp protocols using conditions that have been extensively used in prior studies of INCX at mammalian body temperature [12–15]. To investigate the contribution of ICl,PKA to the activated currents, recordings were also made from rabbit ventricular myocytes under Cl−-selective conditions [32] and from rabbit atrial myocytes, which lack PKA-dependent Cl− current [33], under INCX recording conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell isolation

Right ventricular and left atrial myocytes were isolated from Langendorff-perfused rabbit hearts by enzymatic and mechanical dispersion, as described previously [34]. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Bristol and were performed according to the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. Male New Zealand White rabbits (2.0–3.0 kg) were killed by cervical dislocation and the heart removed promptly via median thoracotomy. The excised heart was placed in a cold (4 °C) heparinised Tyrode's isolation solution (Table 1) to which 750 μM Ca had been added and the aorta was then cannulated quickly into a Langendorff perfusion system. The heart was perfused retrogradely at 37 °C first with isolation solution containing 750 μM Ca2+ for 2 min, followed by 4 min perfusion with the isolation solution containing 100 μM EGTA. Perfusate was then switched to an isolation solution containing a low concentration of Ca2+ (240 μM) supplemented with collagenase (Worthington type 1, 1 mg/ml) and protease (Sigma type XIV, 0.1 mg/ml) for 6 min. The heart was then cut off from the cannula and the right ventricular and left atrial free wall were excised into two separate sterile Petri dishes. Using a pair of fine scissors, these excised tissues were chopped into smaller pieces. The chopped tissue was then shaken in a water-bath with re-circulation enzyme and 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37 °C for 5–10 min. It was then filtered through nylon gauze (200 μm diameter mesh) into a solution containing 3% BSA and 1.5 ml of Kraft-Brühe (KB) medium [35]. The filtrate was centrifuged for 40 s and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was re-suspended in fresh KB medium and stored at 4 °C. Cells were used within 8 h after isolation and only cells with clear rod shape and striations were used for recordings.

Table 1.

Compositions of solutions (mM).

| Constituents | Isolation solution | External solutions |

Internal solutions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT | INCX | ICl,PKA | Low Cl− | INCX | ICl,PKA | ||

| NaCl | 130 | 140 | 140 | 150 | 18 | 10 | – |

| KCl | 4.5 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| HEPES | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| MgCl2 | 3.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Glucose | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 5 | 5.5 |

| NaH2PO4 | 0.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| TEACl | – | – | – | – | – | 20 | 20 |

| EGTA | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | 10 |

| CaCl2 | – | 2.5 | 2.5 | – | – | 1 | – |

| CsCl | – | – | – | – | – | 110 | – |

| BaCl2 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| l-Aspartic acid | – | – | – | – | 132 | – | 85 |

| MgATP | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 |

| Na–creatine PO4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 |

| Na–GTP | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.1 |

| CdCl2 | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Nitrendipine | – | – | 0.01 | – | – | – | – |

| Strophanthidin | – | – | 0.01 | – | – | – | – |

pH of the external solutions 7.45 at room temperature with NaOH and for the internal solution 7.2 with CsOH. NT: normal Tyrode's solution.

2.2. Electrophysiological recording and data acquisition

Whole cell patch clamp experiments were performed at 37 °C. The compositions of all experimental solutions used in the patch-clamp recordings are shown in Table 1. An aliquot of cell suspension was placed onto a glass chamber (∼1 ml volume) on the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus CK40) and the cells were superfused with standard external Tyrode's solution. Experiments were carried out with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, USA). Protocols were generated and recorded with PulseFit software (HEKA Elektronik GmbH, Germany) via an analogue-to-digital converter (ITC-16 computer interface, Instrutech Corporations, USA). Patch-pipettes (Corning 7052 glass, AM Systems Inc., USA) were pulled on a horizontal micropipette puller (Model P-97, Sutter Instruments Company) to a resistance of 2.0–3.5 MΩ. Series resistance and membrane capacitance were compensated prior to acquiring any recordings. Data were recorded at 1 kHz. External solutions were applied using a temperature-controlled rapid solution application device [36].

For INCX recordings, once the whole-cell configuration was achieved, the external superfusate was changed to an NCX-recording solution as used in previous studies (e.g., [13,37]). This K+-free solution (to abolish inward rectifier K+-current), contained 10 μM each of nitrendipine (to inhibit the L-type Ca2+ currents) and strophanthidin to block the Na+–K+-pump (Table 1). INCX was measured as the current sensitive to rapid application of 10 mM Ni2+. This concentration of Ni2+ has previously been shown to be maximally effective in blocking INCX [13]. A voltage ramp protocol was applied from a holding potential of −80 mV once every 10 s; voltage was stepped to +80 mV for 100 ms before a downward ramp to −120 mV over 2 s [12]. For Ni2+-sensitive difference currents, current in the presence of Ni2+ was subtracted from current in control, ISO, noradrenaline (NA) or forskolin, as appropriate.

Recordings of ICl,PKA were made as described previously [32]. The K+- and Ca2+-free external and internal solutions used are shown in Table 1. For experiments using low external [Cl−] (21 mM), Cl− was replaced with aspartate. In order to avoid any change in the liquid junction potential with the low external Cl− solutions, an agar bridge with 3 M KCl was used. To record ICl,PKA, a sawtooth voltage ramp was applied from a holding potential of 0 mV incorporating a downward ramp from +100 mV to −100 mV over 1 s [32]. Recordings of ICa,L were made using the internal solution as used for ICl,PKA recording and a K+-free Tyrode's external solution in which K+ was replaced with equimolar Cs+.

2.3. Chemicals

Chemicals used in the cell-isolation were obtained from British Drug House (BDH, Aristar-grade) or Sigma–Aldrich. Strophanthidin and nitrendipine were dissolved in ethanol as 10 mM stock and appropriate dilutions were added to the external solutions used in the experiments to get a final concentration of 10 μM each. Each of 1 μM isoprenaline (ISO), 1 μM noradrenaline (NA) and 10 μM forskolin (Sigma–Aldrich) were used to activate β-adrenoceptor/PKA in separate experiments; previous studies have used similar concentrations of these compounds to activate maximally the exchanger and the Cl− channel currents [20,24,25]. Stock solutions were made fresh in de-ionised water (ISO and NA) or ethanol (forskolin) on the day of experiment and appropriate dilutions were added to the external solutions as needed.

2.4. Data analysis and presentation

Data were analyzed using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Inc., USA), Excel 2003 and GraphPad Prism software. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), ‘n’ values refer to the number of cells for particular observations (typically from at least two hearts). Membrane current and membrane potential are referred to as Im and Vm, respectively, in subsequent text and figures. Statistical comparisons were made using a paired Student's t test or one or two-way ANOVA as appropriate. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Isoprenaline activates a current under NCX-recording conditions that is Ni2+-sensitive

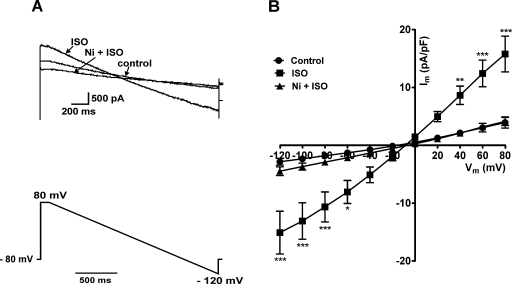

As shown in Fig. 1A, superfusion of the cells with solution containing 1 μM ISO increased the control current several fold (e.g., at +80 mV, ISO activated the control current 4.0 ± 1.2 fold; n = 7). As reported previously, using similar recording conditions in guinea pig ventricular myocytes [15], the ISO-activated current was completely inhibited by further application of 10 mM Ni2+ in the presence of 1 μM ISO. Fig. 1B shows the mean I–V relationships of the net whole-cell currents; the control currents were significantly increased by 1 μM ISO at extremes of voltages tested in the ramp protocol and 10 mM Ni2+ in the presence of same concentration of ISO abolished the ISO-activated current.

Fig. 1.

Effect of 1 μM ISO and 10 mM Ni2+ on whole-cell currents under NCX-recording conditions. (A) Representative traces of the net whole-cell currents in control solution, following superfusion with ISO-containing solution and in the presence of both ISO and Ni2+ (upper panel); voltage ramp protocol is shown in the lower panel. (B) Mean current density–voltage (I–V) relationships of the net whole-cell currents (n = 7). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Bonferroni's post hoc test).

3.2. ICl,PKA activated via β-adrenoceptor stimulation is Ni2+-sensitive

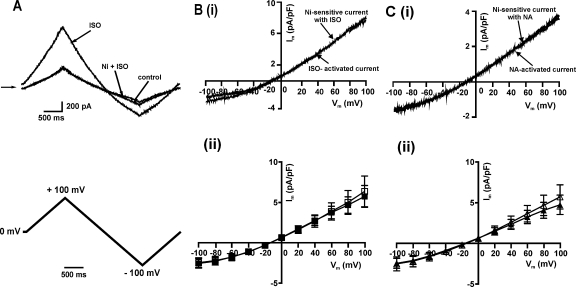

To determine the Ni2+ sensitivity of the β-adrenoceptor-activated ICl,PKA, we used Cl−-recording conditions and each of 1 μM ISO or 1 μM NA as the β-agonists. Fig. 2A (upper panel) shows the representative net whole-cell currents; as was found under NCX recording conditions, the 1 μM ISO-activated ICl,PKA was completely inhibited by 10 mM Ni2+. Fig. 2B (i) shows the I–V relationships of the ISO-activated difference current and the Ni2+-sensitive current in the presence of ISO, demonstrating that the two currents were equivalent to each other; the mean data from 4 cells are shown in Fig. 2B (ii). Similarly, the ICl,PKA activated by the physiological β-adrenoceptor agonist NA was also completely inhibited by Ni2+, as shown in Fig. 2C (i) and (ii).

Fig. 2.

Effect of β-adrenoceptor agonists and Ni2+ on ICl,PKA. (A) Representative traces of net whole-cell current in control and the current activated by 1 μM ISO and the current in the presence of same concentration of ISO + Ni2+ (10 mM). Lower panel shows the voltage ramp protocol. (B) I–V relationships of the current activated by ISO and the current blocked by Ni2+ in the presence of ISO: (i) representative traces (ii) mean (n = 4) of ISO-activated currents (open squares) and Ni2+-sensitive currents (filled squares). (C) I–V relationship of the current activated by NA and the current blocked by Ni2+ in the presence of NA: (i) representative traces (ii) mean (n = 5) of NA-activated currents (open triangles) and Ni2+-sensitive currents (filled triangles).

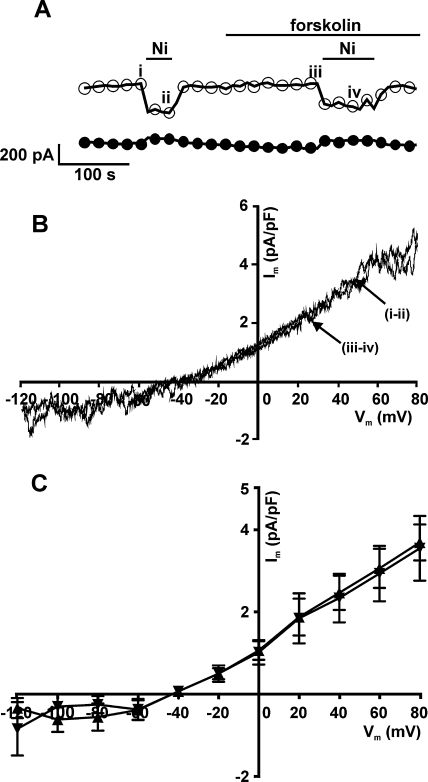

3.3. Forskolin-activated ICl,PKA is not Ni2+-sensitive

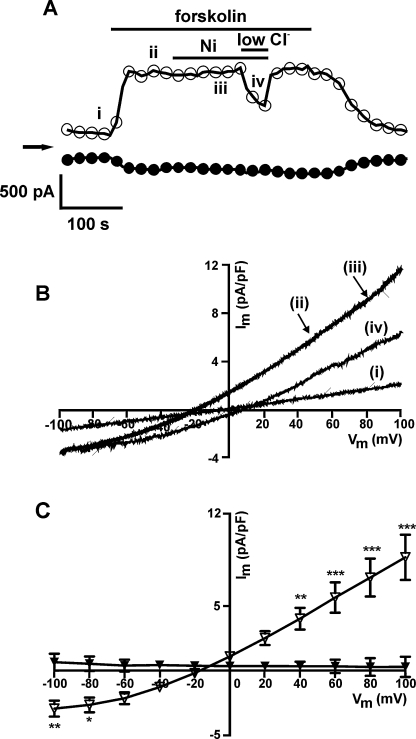

In contrast to the currents activated by the β-agonists, when activated downstream to the β-adrenoceptors using 10 μM forskolin, ICl,PKA was insensitive to 10 mM Ni2+. Fig. 3A shows the time-course of an experiment done under Cl− recording conditions, presenting the net whole-cell currents measured at −100 mV and +100 mV; the forskolin activated current was insensitive to Ni2+. On the other hand, lowering the external solution Cl− concentration (to 21 mM) attenuated the current and shifted the reversal potential to a more positive value (trace iv, Fig. 3B), confirming the forskolin-activated current to be Cl−-selective. Fig. 3C shows the mean I–V relationships of the Ni2+-sensitive difference currents in control and the Ni2+-sensitive difference currents in the presence of forskolin. In summary, there was no Ni2+-sensitive element to the forskolin-activated ICl,PKA.

Fig. 3.

Effect of 10 μM forskolin and 10 mM Ni2+ on ICl,PKA. (A) Representative time-course of changes in currents with superfusion of forskolin and Ni2+ sampled at +100 mV (open circles) and −100 mV (filled circles). (B) I–V relationships of the net whole-cell currents as shown in A. (C) Mean (n = 6) I–V relationships of the currents activated by forskolin (open triangles) and the currents blocked by Ni2+ in the presence of forskolin (filled triangles) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Bonferroni's post hoc test).

3.4. Forskolin does not upregulate Ni2+-sensitive INCX in either rabbit ventricular or atrial myocytes

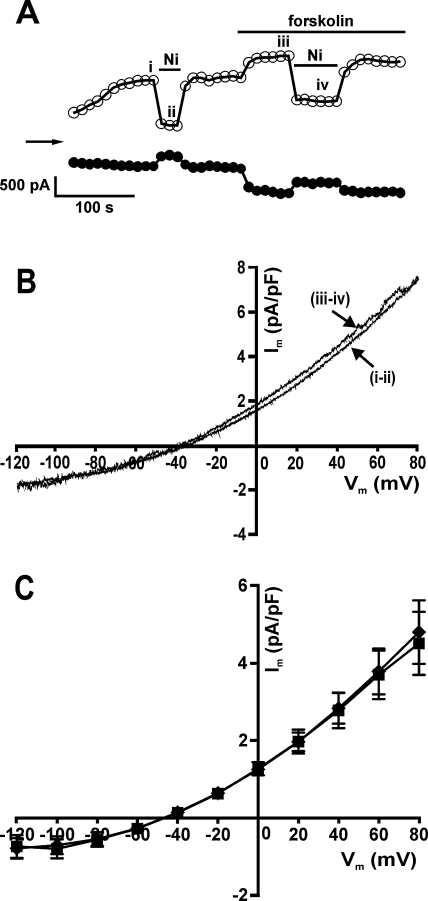

Having established that ICl,PKA activated by forskolin was insensitive to Ni2+, we investigated the effect of 10 mM Ni2+ on the current activated by the same concentration of forskolin (10 μM) under NCX recording conditions. Fig. 4A shows the time-course of a typical experiment on a rabbit ventricular myocyte with net whole-cell currents sampled at −120 mV and +80 mV. Following the initial run-up in the current, Ni2+ was applied to obtain a measure of INCX under control conditions. After washout of the Ni2+, application of forskolin resulted in a further increase in the current. There was indeed a Ni2+-sensitive component to the current in the presence of forskolin under the NCX recording conditions. However, the I–V relationships of the Ni2+-sensitive difference currents in control and the Ni2+-sensitive currents in the presence of forskolin as shown in Fig. 4B (traces ii and iii) were effectively identical. The I–V relationships of the mean data are shown in Fig. 4C. Thus, forskolin did not increase INCX under these recording conditions.

Fig. 4.

Effect of 10 μM forskolin and 10 mM Ni2+ on whole-cell currents under NCX-recording conditions in rabbit ventricular cells. (A) Representative time-course of changes in currents with superfusion of forskolin and Ni2+ sampled at +80 mV (open circles) and −120 mV (filled circles). (B) I–V relationships of the currents blocked by Ni2+ in control (i and ii) and in the presence of forskolin (iii and iv). (C) Mean (n = 5) I–V relationships of the Ni2+-sensitive current in control (filled diamonds) and Ni2+-sensitive current with forskolin (filled squares).

Since rabbit atrial myocytes have been shown to lack ICl,PKA [33], similar experiments were carried out using atrial cells as shown in Fig. 5. 10 μM forskolin did not activate the basal net whole-cell current and the Ni2+-sensitive difference currents in control solution were identical to the Ni2+-sensitive currents in the presence of forskolin (I–V relationships of the representative difference currents and mean data are shown in Fig. 5B and C). In order to verify whether the concentration of forskolin being used was effective in activating PKA-dependent pathways, we tested the effect of 10 μM forskolin on the L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L) in rabbit atrial cells isolated from the same hearts; forskolin increased ICa,L by 2.57 ± 0.71 fold (n = 8, data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Effect of forskolin and Ni2+ in whole-cell currents under NCX-recording conditions in rabbit atrial cells. (A) Representative time-course of changes in currents with superfusion of forskolin and Ni2+ sampled at +80 mV (open circles) and −120 mV (filled circles). (B) I–V relationships of the currents blocked by Ni2+ in control (i and ii) and in the presence of forskolin (ii and iii). (C) Mean (n = 4) I–V relationships of the Ni2+-sensitive difference current in control (filled upward triangles) and Ni2+-sensitive current with forskolin (filled downward triangles).

4. Discussion

We have investigated the effects of acute β-adrenoceptor/PKA-stimulation on currents in rabbit ventricular and atrial myocytes under conditions previously considered ‘selective’ for NCX; we also tested the sensitivity of the PKA-activated Cl− current, ICl,PKA, to Ni2+. Our results provide novel evidence that the apparent increase in INCX with β-adrenoceptor stimulation in rabbit cardiac myocytes is likely due to activation of a PKA-activated Cl− current, which is also sensitive to Ni2+ when activated proximal to the β-adrenoceptors. Importantly, data from rabbit atrial myocytes, which do not express PKA-dependent CFTR Cl− channels, demonstrate that INCX was not increased in the absence of ICl,PKA; to the best of our knowledge, this represents the first investigation of the effects of PKA-stimulation on INCX in rabbit atrial myocytes. In addition, Ni2+ acts to inhibit the response to β-adrenoceptor stimulation at the level of the receptor, but not downstream.

Consistent with previous studies [24], β-adrenoceptor stimulation, using either isoprenaline or noradrenaline, elicited an increase in current in the NCX-recording conditions. However this apparent increase in current is suggested to reflect activation of ICl,PKA as both the INCX and ICl,PKA were found to be sensitive to Ni2+ when activated by β-adrenoceptor stimulation: similar to the report by Lin et al. in guinea pig myocytes [24], ICl,PKA in rabbit ventricular myocytes was sensitive to extracellular Ni2+ when activated by β-adrenoceptor agonists, but not when activated downstream to the receptor by forskolin. This suggests that Ni2+ inhibits ICl,PKA upstream to adenylyl cyclase, most likely at the level of β-adrenoceptors. Thus, since the NCX recording conditions in this study did not preclude the contribution of Cl− currents [5,6], ICl,PKA is very likely to have contributed to the Ni2+-sensitive currents activated by β-adrenoceptor stimulation under NCX recording conditions. On the other hand, the effects on INCX of PKA stimulation via forskolin can be measured reliably as the change in Ni2+-sensitive current. Since ICl,PKA is absent from rabbit atrial myocytes [33], it was possible to examine the modulation of the Ni2+-sensitive INCX in these cells with minimal contamination by ICl,PKA. Consistent with this, the basal net whole-cell current was not increased by 10 μM forskolin in rabbit atrial cells (Fig. 5A). Importantly the Ni2+-sensitive INCX was not stimulated by forskolin (Fig. 5C). Thus, under NCX recording conditions, the Ni2+-sensitive difference current in control and the Ni2+-sensitive current in the presence of forskolin were superimposable, both in rabbit ventricular (Fig. 4B) and atrial myocytes (Fig. 5B). This demonstrates that activation of the PKA-pathway via forskolin does not increase INCX under these conditions.

Whilst our finding of an effect of extracellular Ni2+ at the level of β-adrenoceptors is consistent with that reported by Lin et al. in guinea pig ventricular myocytes [24], our results in part contrast with those of Ginsberg and Bers [23]: whilst both studies report a lack of activation of rabbit INCX via the PKA-pathway, Ginsburg and Bers reported the isoprenaline-activated ICl,PKA in rabbit ventricular myocytes to be insensitive to Ni2+ [23], whereas we found it to be Ni2+-sensitive. The reasons for this apparent discrepancy are unclear. Whilst the precise mechanism for the action of extracellular Ni2+ in our study and that of Lin et al. [24] remains unknown, taken together, the data are compatible with a previously established role for extracellular divalent cations in ligand binding to G-protein-coupled receptors [38].

Although it is clear from our data that, under the conditions of the present study, stimulation of the PKA-pathway downstream to the receptors does not activate rabbit INCX, we cannot exclude entirely the possibility that activation of β-adrenoceptors may modulate NCX function in this species. As there is evidence of compartmentalization of cAMP signalling in sub-cellular microdomains, activation of PKA via β-adrenoceptor stimulation may elicit distinct effects to activation of PKA via forskolin [39]. Evidence for a role of the subcellular environment in the NCX response to PKA-phosphorylation is provided by the observation that while NCX1 activity was shown to be upregulated by PKA in rat myocytes and Xenopus oocytes [27], there was no alteration in the NCX1 activity in response to PKA stimulation when NCX1 was heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells [28]. It has been suggested that NCX1 may be part of a ‘macromolecular complex’ along side PKA-subunits, protein kinase C, protein kinase-A anchoring proteins (mAKAP) and protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A [5,29]. It is also possible that the basal levels of phosphorylation of various PKA-targets including the NCX vary, which will influence the sensitivity to β-adrenoceptor-mediated changes in the INCX; this was indeed shown in failing pig myocytes where there was a higher basal level of phosphorylation of NCX by PKA, which lead to a greater basal INCX [30]. That study also demonstrated almost 500% increase in INCX in non-failing pig myocytes with β-adrenoceptor stimulation [30].

5. Conclusions

We conclude that, under experimental conditions in which major voltage and time-dependent conductances are inhibited: (i) there is contamination by ICl,PKA in the apparent activation of rabbit ventricular INCX seen with β-adrenoceptor stimulation and (ii) that the Ni2+-sensitive INCX is not upregulated by PKA-stimulation in conditions where ICl,PKA is absent. Our results in respect of effects of Ni2+ are consistent with those of Lin et al. [24]. The conclusions of our study are concordant with those of Ginsberg and Bers [23] in that we did not see any upregulation of Ni2+-sensitive INCX with PKA-stimulation in rabbit myocytes under the conditions used at 37 °C. This does not exclude the possibility of modulation of INCX via this pathway under other conditions or in other species. The findings of this study further warn us to be aware of contaminating membrane currents under conditions otherwise thought to be ‘selective’, especially in ventricular cells when INCX is measured as the Ni2+-sensitive current.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lesley Arberry for her technical assistance and Hongwei Cheng for his help with the cell isolations. AFJ and JCH acknowledge funding from the British Heart Foundation. PB is in receipt of a British Heart Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship (FS/07/062).

Contributor Information

Jules C. Hancox, Email: jules.hancox@bristol.ac.uk.

Andrew F. James, Email: A.James@bristol.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Janvier N.C., Boyett M.R. The role of Na–Ca exchange current in the cardiac action potential. Cardiovasc. Res. 1996;32:69–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linck B., Qiu Z., He Z., Tong Q., Hilgemann D.W., Philipson K.D. Functional comparison of the three isoforms of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1, NCX2, NCX3) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1998;274:C415–C423. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philipson K.D., Nicoll D.A., Ottolia M. The Na+/Ca+ exchange molecule. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002;976:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinata M., Kimura J. Forefront of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger studies: stoichiometry of cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; 3:1 or 4:1? J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;96:15–18. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fmj04002x3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y.H., Hancox J.C. Regulation of cardiac Na+–Ca2+ exchanger activity by protein kinase phosphorylation—still a paradox? Cell Calcium. 2009;45(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lines G.T., Sande J.B., Louch W.E., Mørk H.K., Grøttum P., Sejersted O.M. Contribution of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger to rapid Ca2+ release in cardiomyocytes. Biophys. J. 2006;91:779–792. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levi A.J., Brooksby P., Hancox J.C. One hump or two? The triggering of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the voltage dependence of contraction in mammalian cardiac muscle. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:1743–1757. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.10.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leblanc N., Hume J.R. Sodium current-induced release of calcium from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1990;248:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.2158146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benardeau A., Hatem S.N., Rucker-Martin C. Contribution of Na+/Ca2+ exchange to action potential of human atrial myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1996;271:H1151–H1161. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pogwizd S.M., Bers D.M. Na/Ca exchange in heart failure: contractile dysfunction and arrhythmogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002;976:454–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura J., Miyamae S., Noma A. Identification of sodium–calcium exchange current in single ventricular cells of guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 1987;384:199–222. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Convery M.K., Hancox J.C. Comparison of Na+–Ca2+ exchange current elicited from isolated rabbit ventricular myocytes by voltage ramp and step protocols. Pflugers Arch. 1999;437:944–954. doi: 10.1007/s004240050866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinde A.K., Perchenet L., Hobai I.A., Levi A.J., Hancox J.C. Inhibition of Na/Ca exchange by external Ni in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes at 37 degrees C, dialysed internally with cAMP-free and cAMP-containing solutions. Cell Calcium. 1999;25:321–331. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pabbathi V.K, Zhang Y.H., Mitcheson J.S. Comparison of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger current and of its response to isoproterenol between acutely isolated and short-term cultured adult ventricular myocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;297:302–308. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perchenet L., Hinde A.K., Patel K.C., Hancox J.C., Levi A.J. Stimulation of Na/Ca exchange by the beta-adrenergic/protein kinase A pathway in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes at 37 degrees C. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2000;439:822–828. doi: 10.1007/s004249900218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwamoto T., Pan Y., Nakamura T.Y., Wakabayashi S., Shigekawa M. Protein kinase C-dependent regulation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoforms NCX1 and NCX3 does not require their direct phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17230–17238. doi: 10.1021/bi981521q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwamoto T., Pan Y., Wakabayashi S., Imagawa T., Yamanaka H.I., Shigekawa M. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger via protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:13609–13615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwamoto T., Wakabayashi S., Shigekawa M. Growth factor-induced phosphorylation and activation of aortic smooth muscle Na+–Ca2+ exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:8996–9001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan J., Shuba Y.M., Morad M. Regulation of cardiac sodium–calcium exchanger by beta-adrenergic agonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:5527–5532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woo S.H., Morad M. Bimodal regulation of Na+Ca2+ exchanger by beta-adrenergic signaling pathway in shark ventricular myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:2023–2028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041327398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Main M.J., Grantham C.J., Cannell M.B. Changes in subsarcolemmal sodium concentration measured by Na–Ca exchanger activity during Na-pump inhibition and beta-adrenergic stimulation in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1997;435:112–118. doi: 10.1007/s004240050490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ballard C., Schaffer S. Stimulation of the Na/Ca exchanger by phenylephrine, angiotensin II and endothelin 1. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1996;28:11–17. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ginsburg K.S., Bers D.M. Isoproterenol does not enhance Ca-dependent Na/Ca exchange current in intact rabbit ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005;39:972–981. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin X., Jo H., Sakakibara Y. Beta-adrenergic stimulation does not activate Na+/Ca2+ exchange current in guinea pig, mouse, and rat ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C601–C608. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00452.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y.H, Hinde A.K., Hancox J.C. Anti-adrenergic effect of adenosine on Na+–Ca2+ exchange current recorded from guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Cell Calcium. 2001;29:347–358. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han X., Ferrier G.R. Contribution of Na+–Ca2+ exchange to stimulation of transient inward current by isoproterenol in rabbit cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circ. Res. 1995;76:664–674. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruknudin A.M., He S., Lederer W.J., Schulze D.H. Functional differences between cardiac and renal isoforms of the rat Na+–Ca2+ exchanger NCX1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 2000;529:599–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruknudin A.M., Wei S.K., Haigney M.C., Lederer W.J., Schulze D.H. Phosphorylation and other conundrums of Na/Ca exchanger, NCX1. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1099:103–118. doi: 10.1196/annals.1387.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulze D.H., Muqhal M., Lederer W.J., Ruknudin A.M. Sodium/calcium exchanger (NCX1) macromolecular complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:28849–28855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei S.K., Ruknudin A.M., Hanlon S.U., McCurley J.M., Schulze D.H., Haigney M.C.P. Protein kinase A hyperphosphorylation increases basal current but decreases beta-adrenergic responsiveness of the sarcolemmal Na+–Ca2+ exchanger in failing pig myocytes. Circ. Res. 2003;92:897–903. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069701.19660.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei S.K., Ruknudin A.M., Shou M. Muscarinic modulation of the sodium–calcium exchanger in heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115:1225–1233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.650416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James A.F., Tominaga T., Okada Y., Tominaga M. Distribution of cAMP-activated chloride current and CFTR mRNA in the guinea pig heart. Circ. Res. 1996;79:201–207. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takano M., Noma A. Distribution of the isoprenaline-induced chloride current in rabbit heart. Pflugers Arch. 1992;420:223–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00374995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hancox J.C., Levi A.J., Lee C.O., Heap P. A method for isolating rabbit atrioventricular node myocytes which retain normal morphology and function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1993;265:H755–H766. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.2.H755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isenberg G., Klockner U. Calcium tolerant ventricular myocytes prepared by preincubation in a “KB medium”. Pflugers Arch. 1982;395:6–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00584963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levi A., Hancox J., Howarth F., Croker J., Vinnicombe J. A method for making rapid changes of superfusate whilst maintaining temperature at 37 °C. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1996;432:930–937. doi: 10.1007/s004240050217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Convery M.K., Hancox J.C. Na+–Ca2+ exchange current from rabbit isolated atrioventricular nodal and ventricular myocytes compared using action potential and ramp waveforms. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2000;168:393–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hermans E., Challiss R.A. Structural, signalling and regulatory properties of the group I metabotropic glutamate receptors: prototypic family C G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem. J. 2001;359:465–484. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iancu R.V., Ramamurthy G., Warrier S. Cytoplasmic cAMP concentrations in intact cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C414–C422. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00038.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]