Abstract

Purpose: We describe the recruitment strategies and personnel and materials costs associated with two community-based research studies in a Mexican-origin population. We also highlight the role that academic–community partnerships played in the outreach and recruitment process for our studies. We reviewed study documents using case study methodology to categorize recruitment methods, examine community partnerships, and calculate study costs. Results: We employed several recruitment methods to identify and solicit 154 female caregivers for participation in qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys. Recruitment approaches included using flyers and word of mouth, attending health fairs, and partnering with nonprofit community-based organizations (CBOs) to sponsor targeted recruitment events. Face-to-face contact with community residents and partnerships with CBOs were most effective in enrolling caregivers into the studies. Almost 70% of participants attended a recruitment event sponsored or supported by CBOs. The least effective recruitment strategy was the use of flyers, which resulted in only 7 completed interviews or questionnaires. Time and costs related to carrying out the research varied by study, where personal interviews cost more on a per-participant basis ($1,081) than the questionnaires ($298). However, almost the same amount of time was spent in the community for both studies. Implications: Partnerships with CBOs were critical for reaching the target enrollment for our studies. The relationship between the University of California–Los Angeles (UCLA) Resource Center for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement for Minority Elderly and the Department of Aging provided the infrastructure for maintaining connections with academic–community partnerships. Nevertheless, building partnerships required time, effort, and resources for both researchers and local organizations.

Keywords: Mexican Americans, Informal caregiving, Recruitment methods, Academic–community partnerships, Costs

Women and ethnic minority populations have been underrepresented in health research studies (Ford et al., 2008; Heiat, Gross, & Krumholz, 2002; Murthy, Krumholz, & Gross, 2004; UyBico, Pavel, & Gross, 2007). However, results from recent studies suggest that ethnic minorities, including Latinos, do not have an aversion to participating in research studies and are in fact receptive to research. Some studies have shown that ethnic minorities enroll into studies at the same rates as nonminority populations, when given the opportunity for participation (Brown & Topcu, 2003; Wendler et al., 2006). Moreover, retention rates among ethnic minorities are as high as or higher than nonminority research participants, suggesting that once recruited, ethnic minority research participants will enroll and stay enrolled in research studies (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2004).

Research has shown that special efforts and strategies are needed to successfully recruit and retain minority populations into research studies (Evelyn et al., 2001; Heiat et al., 2002; Mason, Hussain-Gambles, Leese, Atkin, & Brown, 2003; Murthy et al., 2004). Studies involving historically underrepresented populations have used a variety of recruitment methods to reach their enrollment goals. Recruitment methods have included use of culturally appropriate and language-specific materials, culturally and linguistically matched research personnel, community health workers or promotores, lay workers such as church volunteers, and face-to-face contact (Escobar-Chaves, Tortolero, Masse, Watson, & Fulton, 2002; Gallagher-Thompson, Solano, Coon, & Arean, 2003; Mann, Hoke, & Williams, 2005; Yancey, Ortega, & Kumanyika, 2006). However, these techniques can be very personnel- and time intensive for the resources available to the average research team.

The primary aim of this article is to describe the successes and challenges associated with recruiting historically underrepresented research participants in a community-based setting: immigrant, Spanish speakers of Mexican origin from the greater East Los Angeles (East LA) area. We examine the financial and nonfinancial costs associated with conducting community-based research, and we highlight the roles that academic–community partnerships and organizational referrals played in the outreach and recruitment process for our studies.

Design and Methods

The approach we took for our studies reflected a community-based participatory research (CBPR) framework (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2005). CBPR is ideally a collaborative approach to research that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings (Norris et al., 2007). However, we did not fully employ a CBPR model. We used two of CBPR's guiding principles for developing and sustaining equitable partnerships between community and academia. We acknowledged that East LA represented a unit of identity as an established community with profound historical, social, and demographic characteristics. We also recognized the importance of leveraging the strengths and resources within the community by seeking collaborations with community-based organizations (CBOs) and developing partnerships with them that we aimed to sustain and strengthen over the long term. These two important principles guided our approach to involving the community in our recruitment efforts for the studies.

Community has diverse meanings, including geographic areas, specific institutions, and culture (Norris et al., 2007). For the purposes of our study, we defined our community, East LA, by its geographic area and the shared cultural and social characteristics of its residents. We defined CBOs as nonprofit agencies (e.g., schools, senior centers, and religious organizations) within East LA that offered social or health-related services to its residents.

The population of interest for our studies was female family caregivers of Mexican descent. The two projects are summarized in Table 1. The projects had an overlapping goal of examining caregiving constructs among women of Mexican origin. We developed broad eligibility criteria because we were interested in examining a range of caregiving experiences. We focused on identifying and enrolling caregivers of community-dwelling, noninstitutionalized elders. Previous studies have highlighted the challenges of recruiting caregivers into research (Buss et al., 2008; Dilworth-Anderson & Williams, 2004; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2003). We expected our study to be no different because Latino caregivers tend to use formal services less than other caregiver populations or have less awareness of available services (Crist, Kim, Pasvogel, & Velázquez, 2009; Mausbach et al., 2004), and caregivers in general may not readily identify themselves in this role (American Association of Retired Persons, 2001; O’Connor, 2007). We further expected our inclusion of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the research to further compound our recruitment challenges.

Table 1.

Description of Research Studies

| Study One: qualitative interviews | Study Two: questionnaires | |

| Time period of studies | July 2005 to July 2007 | August 2007 to June 2009 |

| Goals of study | To examine caregiving experiences of immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican women and the roles that cultural and external factors played in their experiences of giving care to elderly relatives. | To develop and field test a questionnaire for female Mexican-origin caregivers measuring caregiving constructs and activities identified from Study One. |

| Details of study | • One-time interview in person, one-on-one setting • 1-2 hr to complete • Conducted in Spanish and English • $35 incentive |

• One-time administration • Self-administered in a group setting • 30-40 min to complete • Conducted in Spanish and English • $25 incentive |

| Eligibility criteria | • Female caregiver aged 18 years or older of Mexican descent • Care receiver of Mexican descent, at least 60 years old, related by blood or marriage to caregiver and who needed help with one or more activity of daily living or instrumental activity of daily living • Resident of greater East LA area |

|

| Target enrollment | • 20 U.S.-born caregivers (Mexican American) • 20 foreign-born caregivers (Mexican immigrant) |

• 50 English-speaking caregivers • 50 Spanish-speaking caregivers |

| Staffing (FTE) | • PI (0.95) • Undergraduate research assistant (0.19) |

• PI (0.95) • Two undergraduate research assistants (0.325) • Three graduate student researchers (0.125) • Career employee (0.025) |

Note: East LA = East Los Angeles; FTE = full-time equivalent personnel; PI = principal investigator.

The site for our research studies was East LA, CA, an unincorporated area of Los Angeles County geographically located east of Downtown Los Angeles. We chose East LA because it has the highest percentage of Latinos (97%) among the top 10 places in the United States with 100,000 or more population (Guzmán, 2001). Eighty-seven percent of all Latino residents in East LA are of Mexican descent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Almost half of East LA's population is foreign born and 86% are Spanish speakers compared with 40% and 79%, respectively, of the total U.S. Latino population. The age 65-and-older population in East LA is slightly larger and more disabled relative to national estimates for Latinos. About 8% of East LA is at least 65 years old compared with 5% of Latinos nationwide, and 53% of East LA's 65+ population report having at least one disability (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000) compared with 49% of the U.S. Latino population (Waldrop & Stern, 2003). Overall, a higher proportion of East LA's population is low income compared with national estimates for Latinos, where almost 25% of families and 41% of unrelated individuals in East LA are living below the federal poverty level (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000) compared with 20% of all Latino families and 29% of all unrelated Latino individuals nationally (Dalaker, 2001). Among the 25-and-older population, only 34% completed at least high school (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000) compared with 52% of the total U.S. Latino population of the same age (Ramirez, 2004).

Studies have shown that using research personnel with cultural and linguistic similarities to research participants can minimize enrollment barriers, especially in ethnic minority populations (Amador, Travis, McAuley, Bernard, & McCutcheon, 2006). In our studies, we hired Latino research assistants (primarily of Mexican descent) that were fluent in written and oral Spanish to aid the principal investigator (PI) (C. A. Mendez-Luck) who is Mexican American. The study personnel for Study One were completely women, and all but two of the research personnel for Study Two were women. Male research personnel were used to recruit potential participants and assist with follow-up contacts, but data collection activities were conducted solely by female research assistants to increase the likelihood of trust between the participants and the researchers as well as increase participants’ comfort with the overall research process (Amador et al., 2006). Additionally, more than 95% of the time, the research personnel on Study Two were women.

The size of the research teams varied for each study (Table 1). The first study was comprised of the PI (C. A. Mendez-Luck) and one part-time female undergraduate student for a total of 1.14 full-time equivalent personnel (FTEs). The PI conducted some of the English language interviews and the undergraduate research assistant conducted English and Spanish language interviews. The second study was larger, consisting of the PI (C. A. Mendez-Luck) and six part-time research assistants who worked during different stages of the study, for a total of 1.43 FTEs. All but one research assistant were UCLA undergraduate students and masters-level public health students. We hired a career employee specializing in outreach and recruitment for the final two months of the recruitment period to help us reach our target enrollment goal.

We conducted a retrospective review of study files to document the recruitment strategies used to enroll our participants and the costs associated with our studies. We used principles of case study methodology, which is an empirical inquiry of a topic or phenomenon using multiple sources of evidence (Yin, 2009). For this study, our data were study documents generated from a variety of sources. The goal of analyzing these data was to triangulate our findings, or amass converging evidence on recruitment strategies and costs for our studies. To achieve this goal, we reviewed a total of 634 documents: 162 electronic files, 265 paper documents, and 207 e-mail strings. Our review included telephone messages received from potential research participants and representatives of community agencies; internal e-mail communications between research personnel and external e-mail communications with representatives of community agencies; word and excel documents of participant enrollment, potential community partnerships, recruitment events, mileage, field notes, and budgetary expenses; expense reimbursement forms; personnel timesheets; consent forms; incentive receipts; and handwritten notes taken by the research team.

Results

Recruitment Approaches

Our review indicated that we used six main recruitment approaches to enroll a total of 154 immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican female caregivers for the two studies (Table 2). Outreach and recruitment occurred over two time periods, November 2005 to September 2007 (qualitative interviews, Study One) and April 2008 to March 2009 (questionnaires, Study Two). Although Study Two followed closely after Study One, the samples for the two studies were unique in that no caregiver was enrolled into both studies.

Table 2.

Enrollment of Research Participants by Recruitment Approach and Type of Community Organization

| Type of community organization | Recruitment approach |

|||||||

| Public event in community | CBO-sponsored recruitment event or active referral | Flyer/phoned into study | In-person, on-street contact in community | Participant of another UCLA study | Personal referrals | Not documented | Total no. of enrolled participants | |

| Women's social services | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Youth | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| Union | 8 | 2 | 10 | |||||

| Senior services | 57 | 57 | ||||||

| Family multisocial services | 22 | 3 | 25a | |||||

| Alzheimer's association | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Medical clinic or hospital | 8 | 1 | 9 | |||||

| Faith based | 4 | 1 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| Coalition building | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| None—private individuals | 11 | 11 | ||||||

| Not documented | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Not applicable | 13 | 5 | 18 | |||||

| Total no. of enrolled participants | 7 | 104 | 7 | 13 | 5 | 16 | 2 | 154 |

Note: CBO = community-based organization; UCLA = University of Los Angeles–California.

In total, 12 of 22 enrolled participants came from one organization with preexisting partnership with UCLA (East Los Angeles Service Center).

Our recruitment strategies ranged from collaborating with CBOs on targeted recruitment events to independent investigator-initiated efforts such as face-to-face contact with community residents on street corners and bus stops in East LA; attending public events such as health fairs and handing out flyers and/or manning information tables; and posting flyers at local markets, bakeries, and laundromats. We also received permission to post announcements in the weekly bulletin at local Catholic parishes and to post flyers at churches as well as include flyers in the bulletin at one parish. Lastly, we used snowball sampling to recruit participants into the studies. Snowball sampling is a technique for finding study participants using referrals from other participants (Bernard, 1995). After a participant was successfully enrolled into the study, we asked if she knew of another caregiver who might be interested in participating in the research. Former participants and ineligible women aided in recruitment through word of mouth about the projects to their friends and family. Snowball sampling has been shown to be particularly effective for locating community-dwelling caregivers and elders who may not access social or medical services (Mendez-Luck, Kennedy, & Wallace, 2009; Rodriguez, Rodriguez, & Davis, 2006).

The most successful recruitment approaches overall were those due to the collaborative efforts between the researchers and the CBOs, where 104 of 154 (68%) participants were enrolled directly as a result of a CBO-sponsored recruitment event or a direct referral from a CBO (Table 2). For Study One, almost half (17 of 37) of all interviews came from direct referrals from service providers or from the weekly recruitment table at a local community center (described in Organizational Referrals). This collaborative approach was even more noticeable for Study Two where a total of 10 recruitment events were hosted by various local agencies, which yielded 90 completed questionnaires. For most of these events, agency staff was on hand to serve as liaisons between potential study participants and the research team, and to help participants fill out questionnaires, when needed.

Of the recruitment approaches not reliant on collaborations with CBOs, the most successful activities were face-to-face contact in public settings such as at bus stops and street corners (13) and word-of-mouth personal referrals from participants and noneligible community residents (16). Our least effective recruitment strategy was hosting tables at public events such as health fairs. Although we encountered many community residents, we did not come into direct contact with persons eligible for our studies, which led to only seven enrolled participants. The use of flyers was also minimally effective as only seven participants were enrolled as result of receiving or seeing a flyer, from the more than 3,000 distributed throughout the community.

To achieve the total enrollment of 154 participants, we screened or attempted to contact 293 potentially eligible individuals (Table 3). We called potential participants at different days of the week and times of the day. We screened 260 potential participants (89%) and determined that 78 were ineligible for participation. Ineligibility was primarily due to not currently being a caregiver to an elderly family member (i.e., was a nonrelated paid caregiver or relative was younger than 60 years old or had already passed away) and not being of Mexican descent. We were unable to successfully reach 50 potential participants, 17 of whom had initially screened eligible for participation. The most common problems with follow-up were disconnected or wrong phone numbers and no answering machines to leave voice messages. Of the 293 potential participants, we sought to enroll, 11 refused participation outright, all for Study Two.

Table 3.

Recruitment and Enrollment Figures

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Total | |

| Total no. of potential participants | 68 | 225 | 293 |

| Total no. of screened and not eligible | 15 | 63 | 78 |

| Total no. of screened eligible and lost to follow-up | 2 | 15 | 17 |

| Total no. of not screened and lost to follow-up | 14 | 19 | 33 |

| Total no. of refused | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Total no. of enrolled | 37 | 117 | 154 |

We primarily called potential participants during working hours because of student researchers’ work availability, but we made calls in the evenings when possible. We did not track the number of contacts per potential participant for Study One, but we tracked the number of contacts made with 97% of Study Two's potential participants. Of these 219 individuals, 143 were contacted once, during the actual recruitment events. Of the 76 potential participants requiring more than one contact, we placed an average of 1.8 phone calls to enroll a participant in the study (range of one to four contacts), and 3.1 phone calls (range of one to seven) to determine nonparticipation for the reasons previously noted.

Organizational Referrals

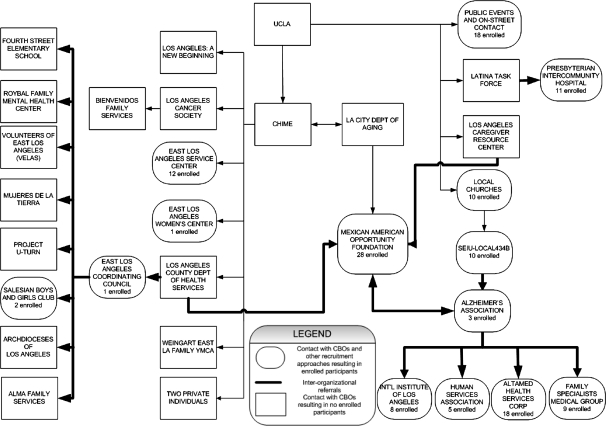

Upon further analysis of our recruitment approaches, we found that the most successful strategies were those which involved CBOs, where the result was snowball sampling at the organization level. Figure 1 shows our entry points into the East LA community. Each rectangular box represents either a recruitment approach (e.g., public events and personal referrals) or a contact with an organization located in East LA and/or that served East LA residents. Boxes with rounded corners represent collaborations with CBOs or independent recruitment approaches by the PI that culminated in successful enrollment of participants. Heavy black lines and arrows indicate where CBOs introduced us to other CBOs for recruitment purposes. Lines that are not heavy indicate where we entered the community and sought recruitment opportunities or collaborations with CBOs through our own independently initiated efforts or from referrals from colleagues at UCLA and at the UCLA and Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science, Resource Center for Minority Aging Research (RCMAR)/Center for Health Improvement for Minority Elderly (CHIME).

Figure 1.

Linkages to community-based organizations and resulting enrollment.

UCLA- and CHIME-affiliated referrals yielded seven potential leads. The greatest success from these leads came from recruitment efforts at the East Los Angeles Service Center (ELASC), a multiservice community facility that houses a range of health, educational, social, and recreational activities for area residents. Recruitment at the ELASC yielded twelve enrolled participants. For Study One only, we received permission from the ELASC to set up a recruitment table at the facility. One day a week for six weeks, we manned a recruitment table for 2 hr prior to the start of the facility's low-cost lunch program. For the remainder of the week, we left a sign-up sheet with the Center's reception desk and collected the sheet weekly.

Overall, referrals initiated by the PI without the support from CBOs resulted in few enrolled participants. Although one CHIME-affiliated source referred us to six different CBOs, we yielded only four enrolled participants. Our contact with a public health nurse at the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services led us to the East Los Angeles Coordinating Council, a community coalition organization that referred us to eight more potential community partners. We initiated contact and arranged meetings, when possible, with the organizations to present the studies and seek potential partnerships. However, not all contacts were successful: some organizations did not respond to our inquiries whereas others offered additional referrals and leads but had no further ability to participate in the studies themselves. In two cases, we were unable to follow up with the organizations due to lack of personnel resources on the study team.

The highest number of enrollments came from organizational referrals. As shown in Figure 1, the LA County public health nurse, the Los Angeles Caregiver Resource Center and the Alzheimer's Association referred us to a program director (E. Jimenez) at the Mexican American Opportunity Foundation (MAOF). The MAOF is a long-standing nonprofit community agency that serves disadvantaged individuals and families in the Los Angeles area. It is the largest Latino-oriented, family services organization in the United States. E. Jimenez oversees the Senior Hispanic Information and Assistance Services Program (SHIAS), which provides information and assistance services to seniors throughout Los Angeles on a variety of topics, including health, transportation, housing, employment, naturalization, and document preparation. The referrals from these organizations led C. A. Mendez-Luck to meet with E. Jimenez and gain support for the projects. SHIAS personnel worked with us to identify clients who might have been eligible for the studies based on our criteria. In some cases, SHIAS personnel contacted clients and asked them if they would like to hear about a federally funded study on family caregiving. Only clients who responded yes and gave permission for their name and phone number to be shared with the study team were then contacted by us for follow-up. In other cases, SHIAS sponsored a recruitment event, inviting potentially eligible residents to hear about our studies. SHIAS managed the invitation lists and the RSVPs. The research team did not have access to client information, only the total number of clients who had RSVP’d.

Our collaboration with the MAOF was supported by the Los Angeles Department of Aging. The Manager of the Department of Aging (L. Trejo) has a long-standing relationship with CHIME. At the time of this study, L. Trejo was the CHIME Community Advisory Board (CAB) chairwoman and the Department of Aging was one of CHIME's 10 community partners. The CAB is part of CHIME's Community Liaison Core whose primary function is to help define which research projects are important to the communities of Los Angeles. Our studies received approval by the CAB before being funded by CHIME. With our approval in hand, we then formally met with the Department of Aging to present the studies and reach an understanding about their benefits to the community. The main role of the Department of Aging was to identify community organizations that would support a partnered approach around community engagement for the sample. L. Trejo identified the SHIAS program, thus giving the researchers a credible basis for establishing and building a research partnership with SHIAS. Overall, the partnership with the SHIAS program yielded the highest number of enrolled participants between the two studies (28) compared with any other single CBO or recruitment approach.

Other organizational referrals were successful in enrolling participants into the studies. One participant's referral led us to the Service Employees International Union Local 434B (SEIU), yielding 10 enrolled participants. Both the SEIU and the SHIAS program director referred us to the East Los Angeles Regional Office of the Alzheimer's Association. This one referral led to a meeting between the researchers and the Alzheimer's Association Regional Director, which eventually gained us access to other local organizations. The Regional Director inquired among the organizations she frequently worked with if they would be interested in assisting with recruitment, and four organizations responded affirmatively by sponsoring a targeted recruitment event with their clients. The organizational snowballing resulting from the Alzheimer's Association's initial referral and brokering on our behalf gained us 43 enrolled participants.

Costs Associated with Conducting Studies in a Community Setting

Our relationship building with the community and recruitment and data collection activities involved many trips to East LA. We reviewed our study documents to examine the various nonfinancial and financial costs associated with conducting this community-based research (Table 4).

Table 4.

Costs Associated With Conducting Research in the Community Setting

| Study One: interviews 37 participants | Study Two: questionnaires 117 participants | |

| Recruitment period | November 2005 to September 2007 | April 2008 to March 2009 |

| Nonfinancial costs | ||

| Total no. of documented visits to community | 63a | 56a |

| No. of visits involving research staff | 41 | 34 |

| No. of visits involving PI | 45 | 39 |

| Approximate total number of trips from UCLA campus to communityb | 41 | 17 |

| Approximate total amount of research staff time spent commuting from UCLA campus to community sitesb | 82 hr (2 hr each trip × 41 trips) | 34 hr (2 hr each trip × 17 trips) |

| Approximate total amount of research staffb time spent in community setting (based on average length of visit, interview, or event) | 57 hr | 114 hr |

| Approximate total amount of research staffb time spent on recruitment-related activities at UCLA research office | 204 hr | 369 hr |

| Approximate total amount of PI time spent for traveling and working in community setting based on 45 trips | 180 hr | 156 hr |

| Approximate total amount of PI time spent on recruitment-related activities at UCLA research office | 667 hr | 400 hr |

| Total hours spent on recruitment activities in and out of community setting during recruitment period | 1,190 hr | 1,073 hr |

| FTE used for recruitment-related activities during recruitment period | 0.28 | 0.33 |

| Average time in community spent per enrolled participant | 8.6 hr | 2.6 hr |

| Financial costs | ||

| Total mileage costb | $875 (for 41 trips) | $377 (for 17 trips) |

| Approximate total of research staffb salary and benefits traveling to community sites | $820 (for 82 hr) | $399 (for 34 hr) |

| Approximate total of research staffb salary and benefits for time spent in community setting (based on average length of visit, interview, or event) | $572 (for 57 hr) | $2781 (for 114 hr) |

| Approximate total of research staffb salary and benefits for recruitment-related activities at UCLA research office | $2,147 (for 204 hr) | $4,818 (for 369 hr) |

| Approximate total of PI salary and benefits for time spent in community setting and commuting to sites | $7,570 (for 180 hr) | $6,560 (for 156 hr) |

| Approximate total of PI salary and benefits for recruitment-related activities at UCLA research office | $26,634 (for 667 hr) | $16,822 (for 400 hr) |

| Financial incentive for participation | $1,295 | $3,140 |

| Cost of flyers | $75 | $346 |

| Event costs | $0 | $556 |

| Total costs related to recruitment | $39,988 | $35,799 |

| Total overall recruitment cost per enrolled participant | $1,080.76 | $298.33 |

Note: PI = principal investigator; UCLA = University of California–Los Angeles; FTE = full-time equivalent personnel.

Includes outreach, recruitment, and data collection activities.

Not including PI.

Number of Visits and Amount of Time Spent in the Community.—

Our analysis of study records indicated that we made 119 documented visits to the community in a 21-month (November 2005 to September 2007) and 13-month period (April 2008 to March 2009) for Studies One and Two, respectively. The purposes of the visits included meeting with CBOs, conducting outreach about the studies, collecting data, and recruiting for the studies. Not all visits to the community involved the entire research team. The PI was present for 71% and 70% of community visits for Studies One and Two, respectively. Research assistants were present for 65% and 61% of visits for Studies One and Two, respectively.

We examined interview tapes, personnel timesheets, budgetary files, meeting notes, and other documents to determine the amount of time we spent in the community itself. We estimated that our research personnel and the PI spent approximately 623 hr in the community, including commuting to and from the university campus and conducting study-related activities. Fewer trips were necessary from the UCLA campus for Study Two as one of the research assistants lived in East LA. Thus, the research staff spent more time in the community (114 hr) compared with commuting to the community (34 hr); this contrasts with Study One where more staff time was spent commuting (82 hr) rather than conducting research activities in the community (57 hr). Although East LA is located relatively close to the UCLA campus (22 miles), we estimated that one one-way trip took an average of one hour of travel time, which was considered part of the research staff's working hours. Therefore, every roundtrip involved an average of 2 hr of personnel travel time. Aside from commuting to community sites, we estimated that the research staff spent 171 hr in the field collecting data and conducting outreach and recruitment in the community. The PI spent almost 50% more time (336 hours) for these same activities. Considerably more time was spent by the PI and research staff at the university campus offices conducting activities in support of the fieldwork, such as calling CBOs and following up with potential research participants. The PI spent almost twice as much time dedicated to these activities compared with the research personnel (1067 vs. 573 hours). Overall, 0.28 FTE and 0.33 FTE were used for Studies One and Two, respectively, for all recruitment-related activities. However, the average time spent in the community per enrolled participant was over three times longer for Study One (8.6 hr) compared with Study Two (2.6 hr).

Financial Costs.—

A review of our budgetary records indicated that project expenses totaled $75,787 solely for the purposes of recruiting and enrolling participants. Personnel salaries were the largest expenses for both studies ($69,123), the majority of which was dedicated in support of fieldwork activities on campus rather than in the field itself. The overall cost per enrolled participant was $1,080.76 and $298.33 for Studies One and Two, respectively. The qualitative interviews (Study One) were almost four times more expensive on a per-enrolled-participant basis compared with the questionnaires (Study Two). The interviews also involved more trips to the community yet less time spent in the community compared with the questionnaires.

Discussion

We used a number of approaches to identify, solicit, and enroll 154 participants into our research studies, and our results suggest that the key to successfully accessing our population depended on identifying the appropriate organizations in the local community that were involved with caregivers and seniors. We engaged these organizations and their professional networks in the research process, which resulted in reaching our enrollment goals.

We can attribute the success in enrollment due to organizational snowballing to a few key factors. First, we partnered with organizations that were recognized, respected, and trusted institutions in the community. These agencies had a long-standing presence in their neighborhoods, which brought us immediate credibility as researchers. The partnerships were essential to gaining access to individuals who historically have been underrepresented in research and perhaps not familiar or trusting of the research process or of academic personnel.

Second, establishing a research partnership between academia and community relied heavily on a champion within a community organization. All of the CBOs involved in our studies had at least one person who advocated for us, either as liaisons with other organizations or as direct partners in the research. The organizational champion believed in the importance of the research and the benefits of the research to the community. Our community partners did not receive financial compensation for their collaboration with us, and they absorbed incidental expenses. Although these expenses were likely modest compared with the major costs associated with the research, they underscored the importance of having an advocate within the organization to invest in research partnerships that did not directly benefit them.

Third, we successfully enrolled immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican female caregivers by working with CBOs that directly served or had access to this population. Working with these organizations allowed us to tailor our recruitment efforts and increased our chances of finding potentially eligible participants. This targeted approach eliminated the additional time and expense involved in screening large numbers of noneligible community residents. This may help to explain why less time was spent overall in Study Two for these activities compared with Study One because our targeted enrollment efforts primarily occurred for Study Two. Additionally, we solicited study participants and collected data at the premises of most organizations, thereby minimizing the barriers of participation (Wendler et al., 2006).

Conducting research in a community setting requires time and resources. Almost two person-days per week and more than two and one-half person-days per week were dedicated to recruitment-related activities, in the community and office, for Studies One and Two, respectively. We were still not able to capitalize on all the leads we were given by sources because of budgetary constraints in personnel.

We learned that future research projects need to allow for the time and personnel costs and material expenses associated with conducting field-based research. It is challenging to place our findings within the context of other research studies because of the limited literature on costs associated with community-based research, especially in immigrant Latino populations. One study examined three recruitment methods for a case-control study of lung cancer in San Francisco and the average number of hours spent on enrolling Latino controls. Cabral and colleagues (2003) found community-based recruitment strategies required 40 min per enrolled control, a fraction of the time it took in our studies. However, the case-control study may have limited comparability to our study because it was not clear if the 40 min included the researcher's time to reach the community or just the time spent on screening and consenting participants once in the community.

We found variability between our studies in the costs and time related to carrying out the research. Study One compared with Study Two cost more on a per-participant basis and took three times as much time on average to enroll a participant in the study. One explanation could have been the difference in study design. For Study One, we primarily used one-on-one recruitment strategies. For Study Two, we held targeted recruitment events in addition to the one-on-one recruitment strategies, which allowed us to screen and enroll multiple individuals at once. However, it is not possible to disaggregate the effects that different recruitment strategies had on enrollment results. We are therefore unable to determine which factors resulted in a lower screener response rate for Study 1 (79%) compared to Study 2 (92%) yet a higher percentage of eligible participants completing interviews (95%) compared to questionnaires (82%).

There are limitations to this study. First, although our findings were based on a systematic review of study documents, we acknowledge that not all aspects of either research study were completely documented. We could only report findings based on the completeness and accuracy of available study-related materials. We expect therefore that our results are conservative estimates of the actual time and expense associated with conducting research in a community-based setting. Second, reaching our target enrollment numbers could have reflected the inducement of a monetary incentive to participants (Erlen, Sauder, & Mellors, 1999), rather than successful research partnerships between UCLA and the community. It could be that our recruitment efforts with CBOs provided a level of coercion among potentially eligible residents who were not interested in participating but did so out of fear of not receiving future goods or services or of hurting their relationships with the agencies. To minimize the possibility of this problem, we kept participants’ names confidential and did not inform the CBOs which of their clients were eligible for the studies or actually participated in them. Third, the personnel costs associated with our study may only be generalizable to similar research settings in high cost-of-living areas in the United States. We attempted to address this issue in two ways. We provided the number of hours associated with the recruitment activities, at the university as well as in the community setting. We also showed the percentage of total project time during the studies’ recruitment periods dedicated solely for the purposes recruiting and enrolling participants. Lastly, we did not use a full CBPR framework for our studies. The community was not involved in developing the research questions or study designs for our projects. However, CHIME's CAB participated in the research process by determining that our projects on elder caregiving were priorities in the community. L. Trejo and E. Jimenez also contributed in the conceptualization of the current study.

However, sustaining partnerships can be equally challenging because many nonprofit agencies run on minimal resources, and the added expenses of collaborating on research projects can be cost prohibitive for some of them. The restrictions in allowable project expenses by funding sources further exacerbate this situation by not permitting academic institutions to direct some of the resources to community partners for infrastructure support. Infrastructure is critical for supporting relationships between academic institutions and community groups that otherwise would not be formed. Our studies capitalized on infrastructure already in place at the academic institution. The RCMAR/CHIME is an example of using federal funds to build capacity for establishing and stabilizing academic–community partnerships. The RCMAR/CHIME's cultivated relationship with the Los Angeles City Department of Aging strengthened our ability to establish and maintain relationships with our community partners. This bond is an example of creating a natural link of the academic institution (UCLA) to the local community. We need similar models that are more resource driven to develop and sustain academic–community partnerships on an ongoing basis.

Our study provides further evidence that conducting research in community settings is possible. Future research should not shy away from including underrepresented populations to answer important questions, especially as it relates to disease-specific health disparities. We recognize that every population is somewhat unique, but our study offers lessons on a partnered research approach that can be applied to community-based research with other populations. Researchers need to identify the community organizations that work directly with the desired population and engage them into the research process to effectively enroll participants into their studies. Champions within these organizations can be especially key to providing critical linkages to other organizations in the community. We partnered with the Alzheimer's Association for our studies. Researchers looking to recruit Alzheimer's caregivers or patients might consider their local chapter of the Alzheimer's Association whereas researchers looking to recruit diabetics might consider the American Diabetes Association or their local diabetes clinic.

Building academic–community relationships require time, patience, physical presence, respect, and commitment, elements frequently in short supply in a busy academic environment (Norris et al., 2007). Increased support for longer grant periods and capacity building would allow academics and community organizations to fully engage in a CBPR process to identify the priority research questions for their community and the methods for successfully carrying out the research.

Funding

University of California–Los Angeles Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly under National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (P30-AG021684) to C.A.M-L., J.M., and C.M.M.; Drew/University of California–Los Angeles Project EXPORT Center by National Institutes of Health/National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20 MD000182) to J.M. and C.M.M.; University of California–Los Angeles Older Americans Independence Center National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (5 P30 AG028748) to C.M.M.; career development grant from the National Institute on Aging (1K01AG033122-01A1) to C.A.M-L.

Acknowledgments

The content of the article does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA or the NIH.

References

- American Association of Retired Persons. AARP caregiver identification study. Washington, DC: AARP; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Amador TK, Travis SS, McAuley WJ, Bernard M, McCutcheon M. Recruitment and retention of ethnically diverse long-term family caregivers for research. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2006;47:139–152. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n03_09. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n03_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. 2nd ed. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Topcu M. Willingness to participate in clinical treatment research among older African Americans and Whites. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:62–72. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.62. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss MK, DuBenske LL, Dinauer S, Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Cleary JF. Patient/caregiver influences for declining participation in supportive oncology trials. Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2008;6:168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral DN, Napoles-Springer AM, Miike R, McMillan A, Sison JD, Wrensch MR, et al. Population- and community-based recruitment of African Americans and Latinos: The San Francisco Bay Area Lung Cancer Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;158:272–279. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg138. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, Kim S-S, Pasvogel A, Velázquez JH. Mexican American elders’ use of home care services. Applied Nursing Research. 2009;22:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.03.002. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalaker J. Poverty in the United States: 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams SW. Recruitment and retention strategies for longitudinal African American caregiving research: The Family Caregiving Project. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16(Suppl. 5):137S–156S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304269725. doi: 10.1177/0898264304269725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlen JA, Sauder RJ, Mellors MP. Incentives in Research: Ethical issues. Orthopaedic Nursing. 1999;18:84–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Chaves SL, Tortolero SR, Masse LC, Watson KB, Fulton JE. Recruiting and retaining minority women: Findings from the Women on the Move study. Ethnicity and Disease. 2002;12:242–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelyn B, Toigo T, Banks D, Pohl D, Gray K, Robins B, et al. Participation of racial/ethnic groups in clinical trials and race-related labeling: A review of new molecular entities approved 1995-1999. Journal of National Medical Association. 2001;93(Suppl. 12):18S–24S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112:228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Singer LS, Depp C, Mausbach BT, Cardenas V, Coon DW. Effective recruitment strategies for Latino and Caucasian dementia family caregivers in intervention research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;12:484–490. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Arean P. Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: Issues to face, lessons to learn. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:45–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.45. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán B. The Hispanic population: Census 2000 Brief. U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heiat A, Gross CP, Krumholz HM. Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical trials. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:1682–1688. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mann A, Hoke MM, Williams JC. Lessons learned: Research with rural Mexican-American women. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.007. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason S, Hussain-Gambles M, Leese B, Atkin K, Brown J. Representation of South Asian people in randomised clinical trials: Analysis of trials’ data. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:1244–1245. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7401.1244. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7401.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Coon DW, Depp C, Rabinowitz YG, Wilson-Arias E, Kraemer HC, et al. Ethnicity and time to institutionalization of dementia patients: A comparison of Latina and Caucasian female family caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2004;52:1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52306.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck CA, Kennedy DP, Wallace SP. Guardians of health: The dimensions of elder caregiving among women in a Mexico City neighborhood. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.026. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris KC, Brusuelas R, Jones L, Miranda J, Duru OK, Mangione CM. Partnering with community-based organizations: An academic institution's evolving perspective. Ethnicity and Disease. 2007;17(Suppl. 1):S27–S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DL. Self-identifying as a caregiver: Exploring the positioning process. Journal of Aging Studies. 2007;21:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2006.06.002. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez R. We the People: Hispanics in the United States, Census 2000 Special Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MD, Rodriguez J, Davis M. Recruitment of first-generation Latinos in a rural community: The essential nature of personal contact. Family Process. 2006;45:87–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00082.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000. Geographic Area: East Los Angeles CDP, California. 2000. Retrieved from http://censtats.census.gov/data/CA/1600620802.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- UyBico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: A systematic review of recruitment interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:852–863. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop J, Stern SM. Disability Status: 2000(No. C2KBR-17) Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, Van Wye G, Christ-Schmidt H, Pratt LA, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Medicine. 2006;3:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]