Abstract

EBV nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) and EBV nuclear antigen LP (EBNALP) are critical for B-lymphocyte transformation to lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). EBNA2 activates transcription through recombination signal-binding immunoglobulin κJ region (RBPJ), a transcription factor associated with NCoR repressive complexes, and EBNALP is implicated in repressor relocalization. EBNALP coactivation with EBNA2 was found to dominate over NCoR repression. EBNALP associated with NCoR and dismissed NCoR, NCoR and RBPJ, or NCoR, RBPJ, and EBNA2 from matrix-associated deacetylase (MAD) bodies. In non–EBV-infected BJAB B lymphoma cells that stably express EBNA2, EBNALP, or EBNA2 and EBNALP, EBNALP was associated with hairy and enhancer of split 1 (hes1), cd21, cd23, and arginine and glutamate-rich 1 (arglu1) enhancer or promoter DNA and was associated minimally with coding DNA. With the exception of RBPJ at the arglu1 enhancer, NCoR and RBPJ were significantly decreased at enhancer and promoter sites in EBNALP or EBNA2 and EBNALP BJAB cells. EBNA2 DNA association was unaffected by EBNALP, and EBNALP was unaffected by EBNA2. EBNA2 markedly increased RBPJ at enhancer sites without increasing NCoR. EBNALP further increased hes1 and arglu1 RNA levels with EBNA2 but did not further increase cd21 or cd23 RNA levels. EBNALP in which the 45 C-terminal residues critical for transformation and transcriptional activation were deleted associated with NCoR but was deficient in dismissing NCoR from MAD bodies and from enhancer and promoter sites. These data strongly support a model in which EBNA2 association with NCoR–deficient RBPJ enhances transcription and EBNALP dismisses NCoR and RBPJ repressive complexes from enhancers to coactivate hes1 and arglu1 but not cd21 or cd23.

Keywords: lymphoma, notch

EBV causes posttransplantation and AIDS-related lymphomas and is a cofactor in African Burkitt lymphoma (BL), and Hodgkin disease. In vitro, EBV latency III infection converts B lymphocytes to immortal lymphoblast cell lines (LCLs) (1).

EBV nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) and EBNALP are the first proteins expressed in latency III infection (2, 3). EBNA2 is essential for B-cell transformation (4, 5) and for up-regulation of EBV latency III and cell RNA expression through CSL/CBF1/ recombination signal-binding protein for immunoglobulin κJ region (RBPJ), a DNA sequence-specific cell transcription factor (6–8). EBNA2 up-regulated cell genes include hairy and enhancer of split 1 (hes1), myc, cd21, and cd23 (2, 9, 10). The EBNA2 acidic activation domain recruits basal and activated transcription factors (TF) including TFIIB, TFIIE, TFIIH, histone acetyl transferases p300, CBP, and PCAF, and RNA polymerase II (11–16).

RBPJ is in repressive complexes containing NCoR1 and -2, SKIP, and SHARP (17–23). NCoR recruits class I and II histone deacetylases (HDAC), including HDAC3, which repress transcription and associate with matrix-associated deacetylase (MAD) bodies, subnuclear sites of repressed transcription (24, 25). NCoR overexpression represses EBNA2 up-regulation of promoter constructs and sequesters RBPJ into MAD bodies (21, 26). The mechanisms through which EBNA2 escapes RBPJ- and NCoR–repressive effects have not been delineated and are the objective of the experiments described here.

EBNALP is critical for EBV transformation of B cells into LCLs (5, 27) and coactivates EBV latency III LMP1 and Cp promoters with EBNA2 (28–30). EBNALP is composed of 66 amino acid repeats and 45 unique C-terminal amino acids. The 45 C-terminal amino acids are important for coactivation and B-cell transformation (5, 27–29, 31, 32). EBNALP homodimerizes and heterodimerizes with HA95, a protein that also heterodimerizes with AKAP95 and is implicated in HP1α, HDAC3, and RNA helicase A (RHA) protein shuttling (33–38). EBNALP relocalizes Sp100 and HP1α within the nucleus (39) and moves HDAC4 to the cytoplasm, consistent with a role in affecting derepression (30, 40). Because NCoR can repress EBNA2 activation of transcription (22, 26), we considered whether EBNALP might antagonize NCoR effects by removing NCoR or NCoR–RBPJ repressive complexes from enhancers or promoters to increase EBNA2 effects.

We now have found that EBNALP decreases NCoR and RBPJ DNA occupancy at enhancer or promoter sites but does not alter EBNA2 association with DNA. Further, EBNA2 associated with NCoR–deficient RBPJ in the presence or absence of EBNALP. These findings support a model in which EBNA2 stabilizes NCoR–deficient RBPJ at enhancers and promoters to activate transcription, whereas EBNALP specifically dismisses repressive NCoR–RBPJ complexes from these sites to coactivate hes1 and arginine and glutamate-rich 1 (arglu1) but not cd21 or cd23 transcription.

Results

EBNALP Associates with NCoR, Strongly Coactivates with EBNA2 Despite NCoR Repression of EBNA2 Activation, Dismisses NCoR from MAD Bodies and Colocalizes with NCoR, and Reverses NCoR Localization of RBPJ or RBPJ and EBNA2 to MAD Bodies.

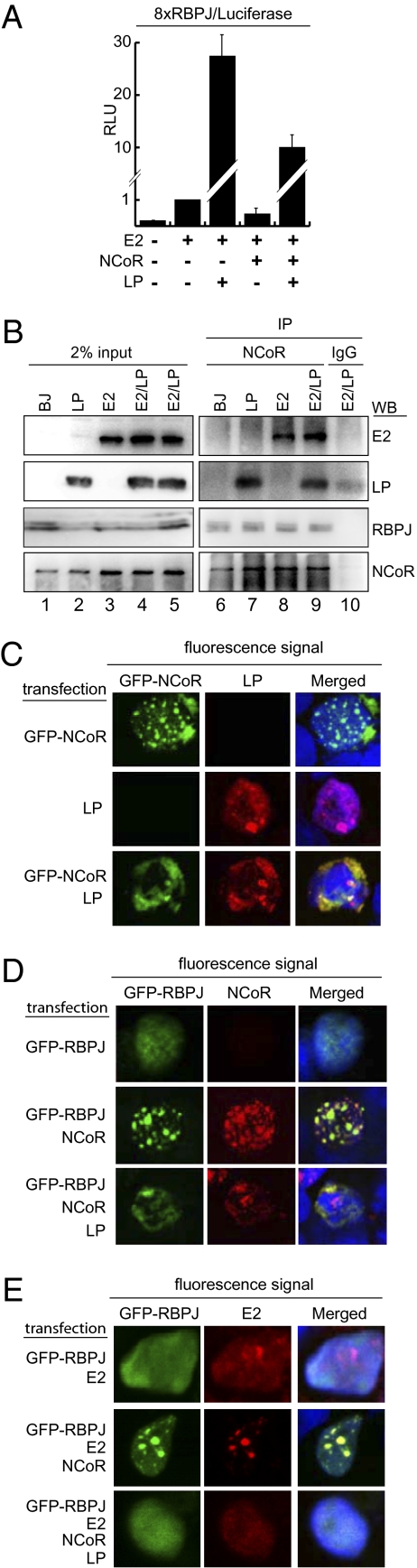

Similar to NCoR2 repression of EBNA2 activation of a RBPJ-responsive reporter (22), NCoR repressed EBNA2 activation of an 8XRBPJ-site reporter when cotransfected into non–EBV-infected BJAB Burkitt lymphoma (BJ) cells by ∼60%, (Fig. 1A, compare columns 2 and 4). As expected, EBNALP with EBNA2 coactivated the reporter ∼25 fold (Fig. 1A) (28–30). The coactivating effect of EBNALP with EBNA2 was the same (∼20–25 fold) in the presence or absence of cotransfected NCoR (Fig. 1A, compare columns 2 and 3 with columns 4 and 5). Thus, EBNALP strongly coactivated with EBNA2, in the presence or absence of sufficient NCoR to repress EBNA2 activation substantially. These data indicate that EBNALP can coactivate with EBNA2 irrespective of NCoR levels.

Fig. 1.

EBNALP reverses EBNA2 repression by NCoR and relocalizes NCoR, RBPJ, and EBNA2 from MAD bodies. (A) Reporter assays in BJAB cells showing Flag–NCoR (NCoR) effects on EBNA2 (E2) and EBNA2 plus EBNALP (LP). EBNA2, NCoR, and EBNALP protein levels were similar throughout the assay. Results are the average of at least five independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM. RLU, relative luciferase units arbitrarily normalized to 1 for EBNA2 effects. (B) Endogenous NCoR was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts prepared from each indicated cell line, using NCoR antibodies. (C–E) BJAB cells were transfected with the plasmids indicated on the left of each panel and stained with antibodies against the proteins indicated on top of each panel or direct fluorescence and analyzed under a confocal microscope (630×). Cells were costained with DRAQ5 DNA stain (blue).

Based on EBNALP effects in relocalizing other repressors (30, 39), we investigated whether EBNALP can relocalize NCoR away from EBNA2 and/or RBPJ. To test whether EBNALP effects are mediated by disruption of NCoR–RBPJ complexes, endogenous NCoR was immunoprecipitated from BJ cell lines that stably express EBNALP (LP), EBNA2 (E2), EBNA2 and EBNALP (E2/LP), or BJ selection resistance control. NCoR antibody immunoprecipitated ∼2% of NCoR, above background levels (Fig. 1B, lane 10) of EBNALP (Fig. 1B, lanes 2, 4, 7, and 9), RBPJ (Fig. 1B, lanes 3, 4, 8, and 9), and EBNA2 (Fig. 1B, lanes 3–5, 8, and 9). Surprisingly, EBNALP, EBNA2, or EBNALP and EBNA2 at LCL levels less than one- to twofold did not globally decrease NCoR association with RBPJ or EBNA2 (Fig. 1B, lanes 7–9). These results indicate that EBNALP and/or EBNA2 do not globally alter NCoR complexes with RBPJ, EBNA2, or EBNALP and that NCoR associates with EBNALP.

To determine whether EBNALP alters NCoR localization, GFP–NCoR, EBNALP, or GFP–NCoR and EBNALP were expressed in BJAB cells (Fig. 1C). GFP–NCoR localized primarily to MAD bodies in 95% of cells and secondarily to more diffuse nuclear or cytoplasm sites (Fig. 1C) (25). EBNALP coexpression redistributed GFP–NCoR from MAD bodies to more diffuse sites, mostly in the nucleoplasm, where GFP–NCoR colocalized with EBNALP (Fig. 1C). Despite these effects, morphology and growth of transfected BJAB cells were unaffected.

Interestingly, a mutant, EBNALPd45, in which the C-terminal domain critical for B-cell transformation and coactivation was deleted (Fig. S1A) (40), colocalized with NCoR to MAD bodies but did not dislocate NCoR (Fig. S1B). These data indicate that MAD body disruption requires the 45 EBNALP C-terminal amino acids, linking MAD body disruption to EBNALP effects in coactivation and transformation.

Because NCoR, NCoR–associated repressors, and RBPJ can colocalize in MAD bodies (17, 18, 41–43), we investigated the effects of EBNALP on NCoR and RBPJ and on potential NCoR and RBPJ complexes. GFP–RBPJ was more diffuse than NCoR in BJAB nuclei, with some small nuclear body localization in the background (Fig. 1D). NCoR coexpression localized GFP-RBPJ to MAD bodies (Fig. 1D) (26). Coexpression of EBNALP with GFP-RBPJ and NCoR blocked NCoR effects and caused large nuclear colocalizations of GFP-RBPJ and NCoR (Fig. 1D). The NCoR and GFP-RBPJ complexes may colocalize with EBNALP, as observed in Fig. 1C. Clearly, EBNALP can relocalize NCoR and RBPJ complexes without globally disrupting the NCoR association with RBPJ.

Because EBNA2 coimmunoprecipitated with NCoR, we proceeded to investigate whether NCoR, RBPJ, EBNA2, and EBNALP can be in the same complex (Fig. 1E). As expected, EBNA2 and RBPJ localized mostly throughout the nucleoplasm. Surprisingly, coexpression of NCoR with RBPJ and EBNA2 relocalized RBPJ and even EBNA2 to dots, similar to MAD bodies (Fig. 1E). Importantly, EBNALP coexpression with EBNA2, RBPJ, and NCoR released EBNA2, RBPJ, and NCoR to the nucleoplasm (Fig. 1E). Thus, EBNALP can release NCoR, RBPJ, and EBNA2 to the nucleoplasm, a site of active transcription.

EBNALP Decreases NCoR and RBPJ Enhancer and Promoter Occupancy.

EBNALP effects are consistent with EBNALP coactivation being, at least in part, a consequence of inhibition of NCoR repression. Because stable EBNALP and/or EBNA2 expression in BJ cells did not globally alter NCoR association with RBPJ or EBNA2, we considered the possibility that EBNALP might dismiss NCoR or NCoR and RBPJ from specific DNA sites, as described for nuclear hormone receptors and Notch effects although RBPJ (38, 44, 45).

To test this hypothesis, ChIP experiments were done using NCoR, RBPJ, EBNALP, or EBNA2 antibodies and LP, E2 or E2/LP stable cells lines. Protein-associated DNA was quantified by quantitative PCR (qPCR). Enhancer sites were chosen from ChIP-seq data for RBPJ and EBNA2 in LCLs and were verified by EBNA2 and RBPJ ChIP-qPCR of DNA from LP, E2, and E2/LP cells. Promoter DNA sites were <2 kbp 5′ to the transcription start site, and coding DNA sites were >2 kbp 3′ to the transcription start site. EBNA2 and RBPJ localization to enhancer sites in E2 and E2/LP cells were confirmed by qPCR. In Affymetrix RNA analyses we focused on hes1, cd21, and cd23 because they are EBNA2 up-regulated in LCLs (9, 10), and on arglu1, which is not activated by EBNA2 or EBNALP but is coactivated approximately twofold (P < 0.0001) by EBNA2 and EBNALP.

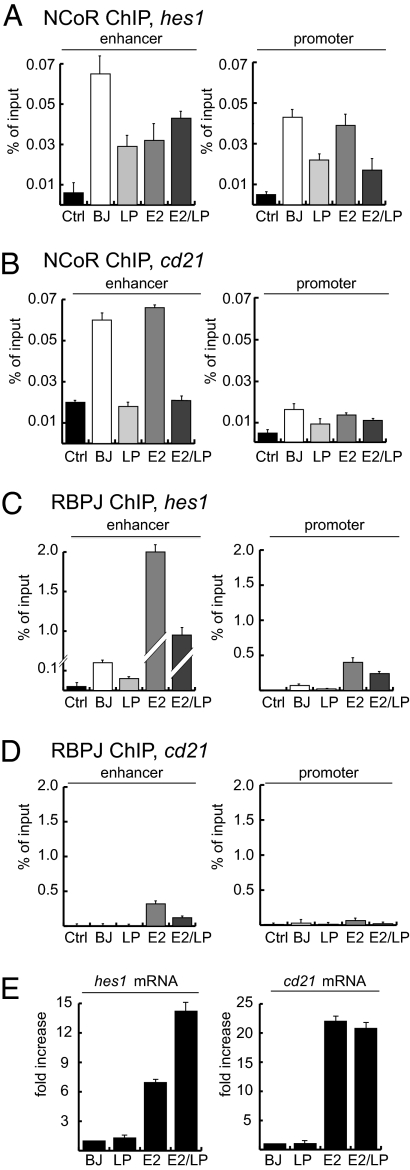

NCoR ChIPs from BJ cells had 0.07% of input hes1, 0.06% of input cd21, and 0.06% of input cd23 and arglu1 enhancer DNA (Fig. 2 A and B and Figs. S2–S4). In contrast, NCoR ChIPs from LP cells had <0.03% input hes1, cd21, and cd23 enhancer DNA and <0.045% of arglu1 enhancer (Fig. 2 A and B and Figs. S2–S4). Each difference was significant (P < 0.01; Fig. S3). Similar significant differences were found at the hes1 promoter site; in BJ cells NCoR was associated with 0.04% of hes1 input promoter DNA, whereas in LP cells, NCoR was associated with 0.02% of hes1 input DNA. These differences from BJ cells were smaller but also were significant (P < 0.01). Similar effects were observed on the arglu1 enhancer (Fig. S4A), which also was identified by EBNA2 occupancy in ChIP-seq experiments from LCLs (Fig. S4C). In contrast, NCoR levels at coding DNA sites were similar to nonimmune IgG background levels (Fig. S5A). At the cd21 promoter, NCoR was associated with only ∼0.01% of input DNA, which was considered background level (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that NCoR was significantly less associated with hes1, cd21, cd23, and arglu1 enhancer DNA sites in LP cells than in BJ cells, consistent with EBNALP dismissal of NCoR from those sites.

Fig. 2.

EBNA2 increases RBPJ on DNA, and EBNALP dismisses NCoR and RBPJ from the hes1 and cd21 enhancer and promoter. (A) qPCR of enhancer and promoter regions of the hes1 gene from ChIP experiments. ChIPs were performed using the antibodies indicated on the top of each panel. Cell extracts were prepared from stable cell lines expressing empty vector (BJ), EBNALP (LP), EBNA2 (E2), or EBNA2 and EBNALP (E2/LP) as indicated at the bottom of each column. Ctrl, negative control performed using isotypic IgG antibodies. Columns represent averages of duplicate reactions relative to input DNA of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM. (B) As in A, but qPCR was performed on enhancer and promoter regions of the cd21 gene. (C and D) As in A and B, but anti-RBPJ antibody was used. (E) qRT-PCR reactions to detect the amounts of hes1 and cd21 RNAs. Values are relative to expression levels detected in the BJ cell line, normalized to 1. Reactions were performed in triplicate; error bars indicate SEM.

NCoR ChIPs from E2 cells revealed NCoR to be associated with 0.03%, 0.07%, 0.05%, and 0.07% of input hes1, cd21, cd23, and arglu1 enhancer DNA and 0.04% and 0.015% of input hes1 and cd21 promoter DNA, respectively, whereas NCoR ChIPs from E2/LP cells had 0.04%, 0.02%, 0.01%, and 0.03% of hes1, cd21, cd23, or arglu1 input enhancer DNA, respectively, and <0.02% and 0.013% hes1 and cd21 promoter DNA, respectively, significantly lower than in BJ cells (P < 0.01). These and other effects were not BJAB clone-specific, because independent clones of BJ, LP, E2, or E2/LP cells had the same characteristics. Overall, relative to BJ cells, NCoR was significantly less associated with hes1, cd21, or cd23, enhancer and in most instances with promoter DNAs in LP or E2/LP cells, indicative of EBNALP dismissal of NCoR from enhancer and most promoter sites.

Interestingly, NCoR precipitated slightly more enhancer DNA in cells stably expressing EBNALPd45 (LPd45) than in control BJ cells. These data indicate that the 45 C-terminal amino acids are required for NCoR dismissal and link dismissal to EBNALP effects in coactivation and LCL outgrowth (Fig. S1C).

RBPJ Enhancer and Promoter Occupancy Is Decreased by EBNALP and Strongly Increased by EBNA2.

Because NCoR and RBPJ associate in repressive complexes and EBNALP relocalized NCoR from enhancers and promoters, we investigated whether EBNALP had similar effects on RBPJ enhancer and promoter occupancy. Indeed, at each site, EBNALP decreased RBPJ association with hes1, cd21, and cd23 enhancers or promoters, in the absence or presence of EBNA2 (Fig. 2 C and D and Figs. S2–S4). EBNALP decreased RBPJ at the hes1 enhancer in LP cells from 0.007 to 0.003% (P < 0.02) and in E2/LP from ∼2% to ∼1%, (P < 0.002) (Fig. 2C). At the hes1 promoter, EBNALP decreased RBPJ occupancy from ∼0.07% in BJ cells to ∼0.02% in LP cells (P < 0.01) and from ∼0.4% in E2 cells to ∼0.2% in E2/LP cells (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2D). Similar effects were observed at the cd21 and cd23 enhancers (Fig. 2D, and Figs. S2B and S3). These data further support a model in which EBNALP dismisses RBPJ and NCoR repressive complexes from enhancer and promoter DNA.

As observed for NCoR, EBNALPd45 was substantially deficient in RBPJ dismissal from the hes1 enhancer, consistent with the defect in NCoR dismissal and compatible with RBPJ dismissal being dependent on NCoR dismissal (Fig. S1D).

EBNA2 markedly increased RBPJ occupancy at the hes1 and cd23 enhancers by ∼20 fold, from ∼0.1% of input DNA to 2% (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2B). Two different RBPJ antibodies yielded similar results. Interestingly, a fourfold effect also was evident at the hes1 promoter (Fig. 2C), where EBNA2 increased RBPJ association with DNA from ∼0.07% to ∼0.4% of input (P < 0.01). At the cd21 enhancer site, RBPJ also associated with significantly more DNA, 0.3%, in E2 cells, compared with 0.005% in BJ control cells (Fig. 2D), whereas RBPJ was at background levels at the cd21 promoter and coding regions (Fig. 2D and Fig. S5B). EBNA2 and EBNALP similarly affected RBPJ association with the arglu1 enhancer element (Fig. S4B). These data indicate that EBNA2 substantially increases RBPJ association with enhancer sites. Furthermore, the EBNA2-mediated RBPJ increase was not associated with NCoR increases at these sites, because NCoR was decreased or unchanged in association with the hes1, cd21, cd23, and arglu1 enhancer or promoter in E2 cells versus BJ cells.

EBNALP Coactivates hes1 but Not cd21 or cd23 Expression.

qRT-PCRs were used to evaluate the extent to which EBNALP decreases in NCoR or RBPJ or EBNA2 increases in RBPJ at the hes1, cd21, or cd23 enhancers increased RNA levels. EBNA2 localization at the hes1, cd21, or cd23 enhancers consistently increased RNA levels (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2C). In contrast, EBNALP had no significant effect on increasing hes1, cd21, or cd23 RNA in the absence of EBNA2 and coactivated only the hes1 enhancer with EBNA2. At the hes1 enhancer, EBNA2 greatly increased RBPJ and decreased NCoR. Although EBNALP did not further reduce NCoR, RBPJ was decreased, and hes1 RNA levels increased from sixfold to almost 14-fold (Fig. 2 A, C, and E).

Consistent with EBNALP dismissal of NCoR complexes having a key role in EBNALP coactivation with EBNA2, EBNALPd45 did not decrease NCoR at the hes1 enhancer or coactivate hes1 mRNA in E2/LPd45 cells (Fig. S1 C–E).

EBNA2 also increased RBPJ at the cd23 and less at the cd21 enhancer in E2 cells, without substantially reducing NCoR but with 20-fold increased cd21 and cd23 RNA levels, more than the EBNA2 and EBNALP hes1 RNA effect. Although EBNALP reduced NCoR at the cd21 and cd23 enhancers in E2/LP cells, cd21 and cd23 RNAs were not further increased (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2). These data indicate that EBNA2 up-regulation of cell gene expression and EBNALP coactivation are more complex than EBNA2 recruitment of NCoR–deficient RBPJ and EBNALP dismissal of NCoR and RBPJ from enhancer sites.

EBNALP and EBNA2 Associate Independently with DNA Sites.

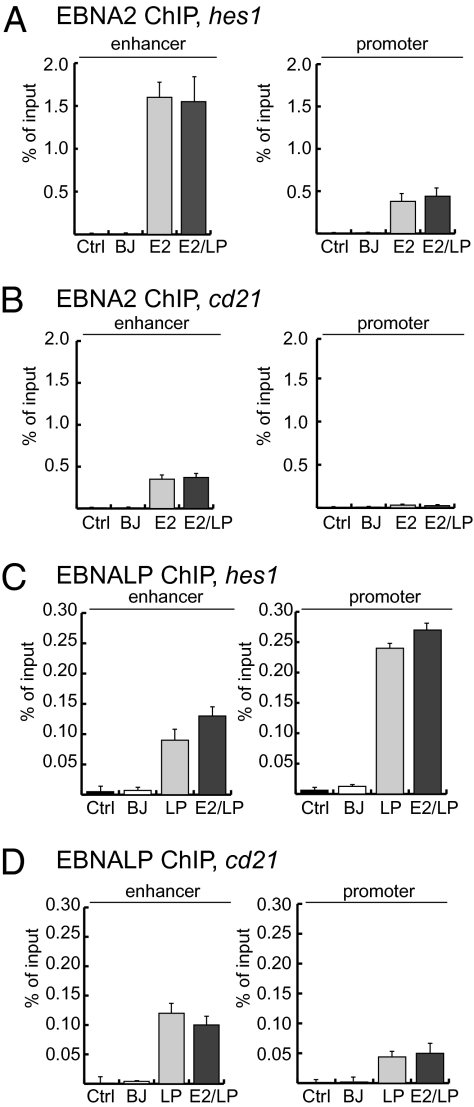

Because EBNALP-dependent dismissal of NCoR complexes could facilitate EBNA2 access to DNA, ChIP-qPCRs from BJ, LP, and E2/ELP cells were used to evaluate whether EBNA2 affected EBNALP or EBNALP affected EBNA2 association with hes1, cd21, cd23, or arglu1 enhancer or promoter DNAs. As shown in Fig. 3 A and B and Figs. S3, S4C, and S6A), EBNA2 associated at the same level with the hes1, cd21, cd23, and arglu1 enhancer or promoter DNA in the presence or absence of EBNALP. Similarly, EBNALP associated at the same level with the hes1, cd23 or cd21 enhancer or promoter, in the presence or absence of EBNA2 (Fig. 3 C and D and Figs. S3 and S6B). EBNALP levels on the arglu1 enhancer were extremely low, correlating with the lower effects observed on NCoR dismissal at that site (Fig. S4 A and D). Interestingly, EBNALP associated ∼2.5-fold more with hes1 promoter than with hes1 enhancer. The high level of EBNALP occupancy at the promoter could be important for the coactivation of hes1 in E2/LP cells. Thus, EBNALP dismisses NCoR–RBPJ from DNA sites but does not affect EBNA2 occupancy at the same sites, consistent with EBNALP affecting NCoR–RBPJ complexes and EBNA2 associating with NCoR–deficient RBPJ (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2).

Fig. 3.

EBNALP does not effect EBNA2 association with enhancer or promoter DNA, and EBNA2 does not effect EBNALP association with enhancer or promoter DNA. (A) ChIP analysis from stable cell lines expressing vehicle control (BJ), EBNALP (LP), EBNA2 (E2), or EBNA2 and EBNALP (E2/LP) of enhancer and promoter regions of the EBNA2-regulated gene hes1, as indicated on top of each panel, using monoclonal EBNA2 antibody. As negative controls, IgG ChIP (Ctrl) on the E2 cell line and E2 ChIP on BJ cell line were performed. Columns represent average percentage DNA relative to input detected in duplicate qPCR reactions. Error bars represent SEM of at least three independent experiments. (B) As in A, but qPCRs were performed on the cd21 enhancer and promoter. (C and D) As in A and B, but using EBNALP antibodies. Control reactions using anti EBNALP antibodies were performed on the LP cell line.

Discussion

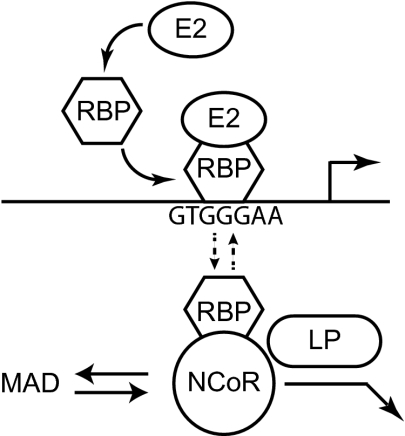

These results describe aspects of the molecular pathogenesis of EBNA2 and EBNALP regulation of cell gene expression and are summarized in a model shown in Fig. 4. Unlike previous models that posit constitutive RBPJ association with cognate DNA (22, 46), EBNA2 has been shown to increase RBPJ occupancy ∼10- to 20-fold at the hes1, cd21, cd23, and arglu1 enhancers. In comparison, Notch and Mastermind increase RBPJ association with enhancer sites by approximately two- to 2.5-fold in S2N cells and >10-fold in DmD8 cells (47), whereas Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV) Rta substantially increases RBPJ binding to cognate DNA in activation of KSHV replication (48).

Fig. 4.

Model of EBNALP and EBNA2 effects on enhancers and promoters. EBNA2 (E2) recruits and stabilizes NCoR–free RBPJ at enhancer and promoter sites, whereas EBNALP (LP) dismisses NCoR–RBPJ repressive complexes from promoters and enhancers.

At EBNA2-responsive enhancers, EBNA2 also localizes with NCoR–deficient RBPJ and up-regulates gene transcription through RBPJ. The EBNA2 acidic domain mediates up-regulatory effects in interacting with TFIIB, TAF40, RPA70, TFIIE, TF2H, p300, CBP, and PCAF (12–15). Acidic domain-recruited activators may contribute to the dissociation of RBPJ and NCoR or enable interaction with NCoR–deficient RBPJ. Alternatively, EBNA2 amino acids 292–310, which are important for RBPJ and SKIP interaction, and EBNA2 amino acids 318–322, which interact directly with the RBPJ β trefoil domain (BTD) (21, 22, 26, 49) may together exclude NCoR from RBPJ–EBNA2 complexes or inhibit NCoR antibody immunoprecipitation. Recently, arginine dimethylated EBNA2 has been reported to interact more strongly with DNA, perhaps selectively through NCoR–deficient RBPJ (50). Putative RBPJ inhibition of NCoR immunoprecipitation is unlikely, given the otherwise positive correlation of NCoR and RBP ChIP data. EBNA2-related increases in RBPJ occupancy did not result in increased NCoR at these sites, despite RBPJ association with NCoR in BJAB cells. Thus, EBNA2 can access NCoR–free RBPJ or EBNA2 interaction with RBPJ disrupts NCoR interaction with RBPJ at specific DNA sites. EBNA2 WWP321 binds directly to the RBPJ BTD and indirectly to RBPJ through the interaction of EBNA2 amino acids 280–290 with SKIP, a RBPJ-interacting protein that also binds NCoR2 (22, 26). Although the RBPJ BTD triple point mutants (EEF233AAA and KLV249AAA) are null for NCoR, NCoR2, and EBNA2 association, favoring a model that NCoR, NCoR2, and EBNA2 compete for the RBPJ BTD site, NCoR2 or EBNA2 still can bind RBPJ triple point mutants (26), perhaps through interactions that are mediated by other NCoR1/2 complexes such as SKIP, SHARP, mSin3A, CIR, or HDAC1–5. Furthermore, NCoR antibodies coimmune precipitate RBPJ, EBNA2, and EBNALP, indicating that EBNA2 can be in NCoR complexes and that NCoR expression relocalized RBPJ and EBNA2 into MAD bodies, indicating that NCoR, RBPJ, and EBNA2 can be in a single complex.

In contrast to EBNA2, which selectively increases NCoR–deficient RBPJ DNA association, EBNALP removal of NCoR from enhancer sites is almost certainly mediated by EBNALP chaperone functions. EBNALP repeat domains homodimerize and heterodimerize at high levels with HA95 (34, 35). HA95 also heterodimerizes with AKAP95 and the HA95/AKAP95 heterodimers associate at high levels with HDAC3, SMRT, and NCoR complexes (38) as well as with HP1α, which is relocalized by EBNALP (39). We have found that EBNALP relocates NCoR and RBPJ complexes away from MAD bodies to the nucleoplasm, where transcription can ensue (40). EBNALP decreases NCoR and RBPJ at enhancer sites without affecting EBNA2 at those sites. The EBNALP association with NCoR is consistent with important effects on NCoR and NCoR–associated repressors, including SKIP, SHARP, HDAC1–5, mSin3A, TBLR1, and RBPJ (44). EBNALP effects on NCoR probably are mediated through HA95 or AKAP95, proteins that could shuttle NCoR and HDAC3 away from specific DNA sites. NCoR–repressive complexes may interact continuously with transcriptionally active chromatin, and EBNALP/HA95/AKAP95 complexes may be critical for their dismissal (Fig. 4). EBNALP also associates with PKA and DNA PK, which may regulate the repressive activity of NCoR1/2 complexes with EBNALP (34).

EBNALP coactivation with EBNA2 at specific promoters probably is dependent on specific resident-repressive and activation-associated transcription factors. EBNALP dismissed NCoR and RBPJ repressive complexes from hes1, cd21, cd23, and arglu1 enhancers but only increased hes1 and arglu1 RNA with EBNA2. Different NCoR–associated repressors (e.g., HDAC3) may be present at different DNA sites, affecting the strength and the specificity of the repressive effects of the complexes at specific sites. EBNALP effects on NCoR and RBPJ complexes are likely to be modified by repressor and activator composition at particular sites. These effects can be strong. EBNA2 and EBNALP coactivation of hes1 in BJAB cells was greater than observed in transiently transfected BL cells (51).

EBNALP effects on decreasing NCoR and RBPJ enhancer occupancy, relocalization of NCoR and RBPJ from MAD bodies, coactivation with EBNA2, and efficient LCL outgrowth following EBV infection were dependent on the 45 EBNALP C-terminal amino acids (5, 27). This correlation suggests that LCL outgrowth requires efficient EBNALP-mediated relocalization of the NCoR1/2 complex from MAD bodies and DNA sites to coactivate transcription and affect LCL outgrowth.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Antibodies, and Immune Fluorescence.

EBV-negative BL cell line BJAB and BJAB EBNA2 cells (52) were used to derive BJAB EBNALP and BJAB EBNA2/EBNALP-expressing lines by stable transfection of pSG5EBNALP. JF186 and PE2 antibodies were used for EBNALP and EBNA2 detection or immune precipitation. Rabbit anti-RBPJ was described (6). NCoR antibody was from Abcam. For immunoflourescence, transfected BJAB were fixed and stained with corresponding antibodies and DRAQ (Alexis Biochemicals). Cells were visualized by confocal microscopy (Nikon).

ChIP.

ChIP assays were done following the Millipore ChIP assay kit protocol. DNA was purified using PCR purification column (Qiagen) and quantitated with a SYBR Green qPCR kit (Applied Biosystems). RNA preparation and qRT-PCR were done as described (9).

Further detailed methods for generation of cell lines, immunofluorescence, immunoprecipitation, and ChIP are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Privalsky (University of California), Dr. D. Hayward (The Johns Hopkins University), and Dr. F. Wang (Brigham and Women's Hospital) for plasmids and cell lines. These investigations were supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01CA47006, R01CA131354, P50 HG004233, and R01CA085180 (to E.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1104991108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rickinson A, Kieff E. Fields Virology. 7th Ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. Epstein-Barr virus; pp. 2655–2700. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfieri C, Allison AC, Kieff E. Effect of mycophenolic acid on Epstein-Barr virus infection of human B lymphocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:126–129. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikitin PA, et al. An ATM/Chk2-mediated DNA damage-responsive signaling pathway suppresses Epstein-Barr virus transformation of primary human B cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen JI, Wang F, Mannick J, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 is a key determinant of lymphocyte transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9558–9562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammerschmidt W, Sugden B. Genetic analysis of immortalizing functions of Epstein-Barr virus in human B lymphocytes. Nature. 1989;340:393–397. doi: 10.1038/340393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman SR, Johannsen E, Tong X, Yalamanchili R, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 transactivator is directed to response elements by the J kappa recombination signal binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7568–7572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henkel T, Ling PD, Hayward SD, Peterson MG. Mediation of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2 transactivation by recombination signal-binding protein J kappa. Science. 1994;265:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yalamanchili R, et al. Genetic and biochemical evidence that EBNA 2 interaction with a 63-kDa cellular GTG-binding protein is essential for B lymphocyte growth transformation by EBV. Virology. 1994;204:634–641. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao B, et al. RNAs induced by Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 in lymphoblastoid cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1900–1905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510612103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maier S, et al. Cellular target genes of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2. J Virol. 2006;80:9761–9771. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00665-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bark-Jones SJ, Webb HM, West MJ. EBV EBNA 2 stimulates CDK9-dependent transcription and RNA polymerase II phosphorylation on serine 5. Oncogene. 2006;25:1775–1785. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong X, Wang F, Thut CJ, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 acidic domain can interact with TFIIB, TAF40, and RPA70 but not with TATA-binding protein. J Virol. 1995;69:585–588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.585-588.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong X, Drapkin R, Yalamanchili R, Mosialos G, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 acidic domain forms a complex with a novel cellular coactivator that can interact with TFIIE. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4735–4744. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong X, Drapkin R, Reinberg D, Kieff E. The 62- and 80-kDa subunits of transcription factor IIH mediate the interaction with Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3259–3263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Grossman SR, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 interacts with p300, CBP, and PCAF histone acetyltransferases in activation of the LMP1 promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:430–435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen JI, Kieff E. An Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 domain essential for transformation is a direct transcriptional activator. J Virol. 1991;65:5880–5885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5880-5885.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downes M, Ordentlich P, Kao HY, Alvarez JG, Evans RM. Identification of a nuclear domain with deacetylase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10330–10335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kao HY, Downes M, Ordentlich P, Evans RM. Isolation of a novel histone deacetylase reveals that class I and class II deacetylases promote SMRT-mediated repression. Genes Dev. 2000;14:55–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oswald F, et al. SHARP is a novel component of the Notch/RBP-Jkappa signalling pathway. EMBO J. 2002;21:5417–5426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu J, Li Y, Ishizuka T, Guenther MG, Lazar MA. A SANT motif in the SMRT corepressor interprets the histone code and promotes histone deacetylation. EMBO J. 2003;22:3403–3410. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou S, et al. SKIP, a CBF1-associated protein, interacts with the ankyrin repeat domain of NotchIC To facilitate NotchIC function. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2400–2410. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2400-2410.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou S, Fujimuro M, Hsieh JJ, Chen L, Hayward SD. A role for SKIP in EBNA2 activation of CBF1-repressed promoters. J Virol. 2000;74:1939–1947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1939-1947.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodson ML, Jonas BA, Privalsky ML. Alternative mRNA splicing of SMRT creates functional diversity by generating corepressor isoforms with different affinities for different nuclear receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7493–7503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411514200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voss TC, Demarco IA, Booker CF, Day RN. Functional interactions with Pit-1 reorganize co-repressor complexes in the living cell nucleus. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3277–3288. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voss TC, Demarco IA, Booker CF, Day RN. Corepressor subnuclear organization is regulated by estrogen receptor via a mechanism that requires the DNA-binding domain. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;231:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou S, Hayward SD. Nuclear localization of CBF1 is regulated by interactions with the SMRT corepressor complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6222–6232. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6222-6232.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mannick JB, Cohen JI, Birkenbach M, Marchini A, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein encoded by the leader of the EBNA RNAs is important in B-lymphocyte transformation. J Virol. 1991;65:6826–6837. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6826-6837.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harada S, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein LP stimulates EBNA-2 acidic domain-mediated transcriptional activation. J Virol. 1997;71:6611–6618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6611-6618.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCann EM, Kelly GL, Rickinson AB, Bell AI. Genetic analysis of the Epstein-Barr virus-coded leader protein EBNA-LP as a co-activator of EBNA2 function. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:3067–3079. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Portal D, Rosendorff A, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen leader protein coactivates transcription through interaction with histone deacetylase 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19278–19283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609320103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng CW, Zhao B, Kieff E. Four EBNA2 domains are important for EBNALP coactivation. J Virol. 2004;78:11439–11442. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11439-11442.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng R, Tan J, Ling PD. Conserved regions in the Epstein-Barr virus leader protein define distinct domains required for nuclear localization and transcriptional cooperation with EBNA2. J Virol. 2000;74:9953–9963. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.9953-9963.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westberg C, Yang JP, Tang H, Reddy TR, Wong-Staal F. A novel shuttle protein binds to RNA helicase A and activates the retroviral constitutive transport element. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21396–21401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909887199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han I, et al. EBNA-LP associates with cellular proteins including DNA-PK and HA95. J Virol. 2001;75:2475–2481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2475-2481.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han I, et al. Protein kinase A associates with HA95 and affects transcriptional coactivation by Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2136–2146. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2136-2146.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martins SB, et al. HA95 is a protein of the chromatin and nuclear matrix regulating nuclear envelope dynamics. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3703–3713. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orstavik S, et al. Identification, cloning and characterization of a novel nuclear protein, HA95, homologous to A-kinase anchoring protein 95. Biol Cell. 2000;92:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(00)88761-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, et al. A novel histone deacetylase pathway regulates mitosis by modulating Aurora B kinase activity. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2566–2579. doi: 10.1101/gad.1455006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ling PD, et al. Mediation of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-LP transcriptional coactivation by Sp100. EMBO J. 2005;24:3565–3575. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng CW, et al. Hsp72 up-regulates Epstein-Barr virus EBNALP coactivation with EBNA2. Blood. 2007;109:5447–5454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-040634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodson M, Jonas BA, Privalsky MA. Corepressors: Custom tailoring and alterations while you wait. Nucl Recept Signal. 2005;3:e003. doi: 10.1621/nrs.03003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones PL, Sachs LM, Rouse N, Wade PA, Shi YB. Multiple N-CoR complexes contain distinct histone deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8807–8811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones PL, Shi YB. N-CoR-HDAC corepressor complexes: Roles in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2003;274:237–268. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55747-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perissi V, Jepsen K, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Deconstructing repression: Evolving models of co-repressor action. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:109–123. doi: 10.1038/nrg2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perissi V, et al. TBL1 and TBLR1 phosphorylation on regulated gene promoters overcomes dual CtBP and NCoR/SMRT transcriptional repression checkpoints. Mol Cell. 2008;29:755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young LS, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus: 40 years on. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:757–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krejcí A, Bray S. Notch activation stimulates transient and selective binding of Su(H)/CSL to target enhancers. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1322–1327. doi: 10.1101/gad.424607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carroll KD, et al. Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic switch protein stimulates DNA binding of RBP-Jk/CSL to activate the Notch pathway. J Virol. 2006;80:9697–9709. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00746-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harada S, Yalamanchili R, Kieff E. Residues 231 to 280 of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 are not essential for primary B-lymphocyte growth transformation. J Virol. 1998;72:9948–9954. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9948-9954.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gross H, et al. Asymmetric Arginine dimethylation of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 promotes DNA targeting. Virology. 2010;397:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peng R, Moses SC, Tan J, Kremmer E, Ling PD. The Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-LP protein preferentially coactivates EBNA2-mediated stimulation of latent membrane proteins expressed from the viral divergent promoter. J Virol. 2005;79:4492–4505. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4492-4505.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein (LMP1) and nuclear proteins 2 and 3C are effectors of phenotypic changes in B lymphocytes: EBNA-2 and LMP1 cooperatively induce CD23. J Virol. 1990;64:2309–2318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2309-2318.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.