Abstract

Antioxidant enzymatic pathways form a critical network that detoxifies ROS in response to myocardial stress or injury. Genetic alteration of the expression levels of individual enzymes has yielded mixed results with regard to attenuating in vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, an extreme oxidative stress. We hypothesized that overexpression of an antioxidant network (AON) composed of SOD1, SOD3, and glutathione peroxidase (GSHPx)-1 would reduce myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by limiting ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation and oxidative posttranslational modification (OPTM) of proteins. Both ex vivo and in vivo myocardial ischemia models were used to evaluate the effect of AON expression. After ischemia-reperfusion injury, infarct size was significantly reduced both ex vivo and in vivo, ROS formation, measured by dihydroethidium staining, was markedly decreased, ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation, measured by malondialdehyde production, was significantly limited, and OPTM of total myocardial proteins, including fatty acid-binding protein and sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)2a, was markedly reduced in AON mice, which overexpress SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1, compared with wild-type mice. These data demonstrate that concomitant SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPX-1 expression confers marked protection against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, reducing ROS, ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation, and OPTM of critical cardiac proteins, including cardiac fatty acid-binding protein and SERCA2a.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, superoxide dismutase, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a, reperfusion injury, myocardial ischemia

the mechanisms responsible for altered susceptibility to ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury are incompletely understood but involve the generation of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and are influenced by cellular protective mediators such as SOD, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GSHPx) as well as abnormal Ca2+ handling. The accumulation of Ca2+ and the generation of reactive species, including nitric oxide (NO), superoxide (O2·−), and peroxynitrite (ONOO−), are believed to play an important role in I/R injury. In cardiovascular disease states, including I/R injury, increased protein tyrosine nitration, an irreversible detrimental protein modification mediated by ONOO−, is observed. Tyrosine nitration leads to decreased activity of several myocardial proteins, including mitochondrial and Ca2+-regulating proteins (24, 32, 46).

Myocardial cells are protected from minor oxidant challenges by an antioxidant network (AON) that includes enzymes such as SOD, catalase, and GSHPx (12, 20, 34, 49). Superoxide anions are readily dismutated by SOD into H2O2, which can then be converted into hydroxyl radicals by a Fenton-type reaction or scavenged by either catalase or GSHPx. Three SOD isoenzymes have been identified in mammalian cells: copper- and zinc-containing SOD (Cu/Zn-SOD or SOD1), which is expressed as dimers in the cytoplasm; manganese-containing SOD (Mn-SOD or SOD2), which is expressed as tetramers in the mitochondria; and tetrameric extracellular SOD (EC SOD or SOD3). GSHPx-1, which is expressed in both the cytosol as well as the mitochondrial matrix, can use either lipid peroxides or H2O2 as substrates. Studies have suggested that hearts from SOD1 (56) and GSH-Px (57) knockout mice are more susceptible to I/R injury and that overexpression of either SOD1 (51), SOD3 (10), or GSHPx-1 (35, 42, 58) renders the heart more resistant to ex vivo myocardial I/R injury. However, in vivo, the efficacy of overexpression of individual antioxidant enzymes was not protective as either overexpression of GSHPx-1 or overexpression of SOD1 was found to be cardioprotective (23). One possibility is that neither enzyme alone is capable of full cardioprotective efficacy. Indeed, prior work has suggested that manipulation of the expression of one enzyme may lead to an imbalance in the antioxidant system (13, 38, 39). Therefore, the work reported here tested the hypothesis that concomitant overexpression of SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 attenuates myocardial I/R injury. We report that concomitant overexpression SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 conveys marked protection against myocardial I/R injury, reducing ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation and oxidative posttranslational modification (OPTM) of critical myocardial proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic mice.

The generation of AON-overexpressing triple-transgenic mice has been previously described (31, 36). Constructs were prepared by cloning tagged cDNAs for human antioxidant enzymes (SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1) into a vector containing the mouse H-2Kb promoter. AON mice were backcrossed for >10 generations onto the C57BL6 background. The investigation described conformed with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Ohio State University Medical Center.

Ex vivo myocardial I/R injury.

Hearts isolated from AON-overexpressing mice or wild-type (WT) littermate controls were perfused using a nonworking heart Langendorff system with a constant perfusion pressure of 80 mmHg. Hearts were subjected to global ischemia of 30 min and reperfusion of 60 min as previously described (19). At the end of reperfusion, the heart was processed for the subsequent analysis of myocardial infarct size, ROS generation, and protein modification as described below. Ex vivo hearts were trimmed of all atria and fat while still cannulated and then perfused with 2 ml of 1.5% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolim chloride (TTC) at 37°C. Hearts were frozen, sectioned into 1-mm sections, fixed in 10% formalin, and weighed. To calculate infarct size (IS)/weight, both sides of each section were digitally photographed and contoured with MetaVue software to delineate ischemic (red) and infarcted (white) tissue. Infarcts were reported as a percentage of the total left ventricular (LV) area multiplied by the total weight of that section.

In vivo myocardial I/R.

The in vivo myocardial I/R mouse model was performed using previously described techniques (59). Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (55 mg/kg) plus xylazine (15 mg/kg). Atropine (0.05 mg sc) was administered to reduce airway secretions. Animals were intubated and ventilated with room air (tidal volume: 250 μl, 120 breaths/min) with a mouse respirator (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Rectal temperatures were maintained at 37°C by a thermoregulated heating pad. After a thoracotomy, an 8-0 silk suture was placed around the left coronary artery for ligation. After either a 20- or 60-min duration of ischemia, the occlusion was released, and reperfusion was confirmed visually. At 60 min of reperfusion [malondialdehyde (MDA) and protein analysis] or 24 h of reperfusion (infarct analysis), mice were reanesthetized, intubated, and ventilated as described above. The chest was reopened along the previous incision line to expose the heart, and the left main coronary artery was religated in the same location as before. The heart was excised, and the aorta was cannulated. Three milliliters of 10% phthalo blue (Heubach) was slowly injected directly into the aorta to stain the heart for delineation of the ischemic zone from the nonischemic zone. The area of the myocardium that did not stain with phthalo blue was defined as the area at risk (AAR). Serial, short-axis, 1-mm-thick sections were cut and incubated in 1.0% TTC for 15 min at 37°C for demarcation of the viable and nonviable myocardium within the AAR (after TTC staining, the area of infarction was pale, whereas the viable myocardium was red). Each of the 1-mm-thick myocardial slices was placed in 10% formalin overnight and then weighed, and the areas of infarction, AAR, and nonischemic LV were assessed. To calculate IS/weight, both sides of each of the myocardial slices were photographed with a high-resolution digital camera and contoured with a planimeter (Adobe PhotoShop 5.0) to delineate the borders of the entire heart, the nonischemic area, and the infarcted area. The sizes of the nonischemic area, AAR, and IS area were calculated as percentages of the total LV area multiplied by the total weight of that slice.

Immunoblot analysis.

Hearts were homogenized in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mM sodium fluoride with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) for 10 s × 3 cycles. After 30 min of protein solubulization, samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and 50% glycerol was added to each supernatant to a final concentration of 10%. Supernatants were vortexed, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C. All protein processing was carried out at 4°C. Equal amounts of protein, verified with Coomassie staining, were loaded into Bio-Rad SDS-PAGE gels and electrophoresed. After transfer onto nitrocellulose, membranes were washed in 0.05% Tween in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5), blocked in 5% milk, and probed with primary antibody [anti-human GSHPx, rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; anti-human-SOD1, rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling; anti-human-SOD3, rabbit polyclonal, Abcam, Cambridge, MA; anti-sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), custom rabbit polyclonal, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; anti-phospholamban, custom rabbit polyclonal, Invitrogen; anti-ryanodine receptor, mouse monoclonal IgG1, Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO; anti-calsequestrin, rabbit polyclonal IgG, Affinity Bioreagents; anti-GAPDH, rabbit IgG, Cell Signaling; and anti-3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT), mouse monoclonal IgG2, Millipore, Temecula, CA]. Membranes were washed in 0.05% Tween in Tris-buffered saline and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (KPL), and Supersignal (Pierce) was used to visualize proteins. Blots were imaged and quantified in a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc using Quantity One software.

Antioxidant enzyme activity.

GSHPx activity was measured indirectly by a coupled reaction with glutathione reductase according to the manufacturer's protocol (Cayman Chemical) (40). Briefly, with the reduction of hydroperoxide by GSHPx, oxidized glutathione is produced. Oxidized glutathione is reduced by glutathione reductase and NADPH. The oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ results in a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm, and the rate of decrease in the absorbance at 340 nm is directly proportional to GSHPx-1 activity. Activity was expressed per milligram of protein.

For SOD activity, samples were processed as previously described (36), and SOD activity was assessed using a tetrazolium salt for the detection of superoxide radicals generated by xanthine oxidase and hypoxanthine according to the manufacturer's protocol (Cayman Chemical). Absorbance at 460 nm was monitored, and samples were compared with a SOD standard curve. Activity was expressed per milligram of protein.

Immunoprecipitation.

Hearts were rapidly excised, cannulated through the aorta, perfused with 3 ml of ice-cold saline, and weighed. Ventricles were homogenized in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mM sodium fluoride with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) for 10 s × 3 cycles. After 30 min of protein solubulization, samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and 50% glycerol was added to each supernatant to a final concentration of 10%. Supernatants were vortexed, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C. Total protein homogenate (500 μg) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) were added to 10 μg of 3-NT (Millipore) or SERCA2a (Invitrogen) antibody and agitated for 1 h at 4°C. Each sample/antibody complex was incubated with protein A and G bead slurry (Calbiochem) for 3 h and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 s. Supernatants were removed, and beads washed three times with lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 1% Nonidet P-40. Laemmli buffer was added to each bead pellet, vortexed, and boiled at 99°C for 10 min. The resulting samples were spun at 10,000 g for 5 min, and supernatants were loaded onto 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels, subjected to electrophoretic separation, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for the subsequent Western protocol as described above.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

Three replicates of control and transgenic heart homogenates, processed by the immunoblot protocol, were pooled in equal protein amounts. For two-dimensional gel electrophoretic comparison of total lysates, 100 μg of each pooled sample were combined with either Cy3 dye (WT, green) or Cy5 dye (AON, red) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Reactions were terminated with the addition of 10 mM lysine. Samples were used to rehydrate a 3–10 pH 24-cm isoelectric focusing (IEF) strip overnight (GE IPGphor), which was protected from light. The IEF strip was focused using the manufacturer's protocol and run on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was removed and imaged on a GE Typhoon Phosphorimager for analysis.

3-NT detection.

For 3-NT detection, 100 μg protein of each pooled sample were used to rehydrate a 3–10 pH 24-cm IEF strip overnight (GE IPGphor). The IEF strip was focused using the manufacturer's protocol and then electrophoresed on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was removed, transferred to nitrocellulose, and then subjected to immunoblot analysis as described in Immunoblot analysis using anti-3-NT antibody. Detection was performed using a Cy3-labeled secondary antibody, and Western blots were imaged using a Typhoon Phosphorimager.

Protein identification.

Gels were digested with sequencing grade trypsin from Promega (Madison, WI) or sequencing-grade chymotrypsin from Roche (Indianapolis, IN) using Multiscreen Solvinert Filter Plates from Millipore (Bedford, MA). Briefly, bands were trimmed as close as possible to minimize background polyacrylamide material. Gel pieces were then washed in nanopure water for 5 min. The wash step was repeated twice before gel pieces were washed and or destained with 1:1 (vol/vol) methanol-50 mM ammonium bicarbonate for 10 min twice. Gel pieces were dehydrated with 1:1 (vol/vol) acetonitrile-50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Gel bands were rehydrated and incubated with DTT solution (25 mM in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate) for 30 min before the addition of 55 mM iodoacetamide in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution. Iodoacetamide was incubated with the gel bands in the dark for 30 min. Gel bands were washed again with two cycles of water and dehydrated with 1:1 (vol/vol) acetonitrile-50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The protease was driven into the gel pieces by rehydrating them in 12 ng/ml trypsin in 0.01% ProteaseMAX Surfactant for 5 min. Gel pieces were then overlaid with 40 ml of 0.01% ProteaseMAX surfactant and 50 mM ABC and gently mixed on a shaker for 1 h. Digestion was stopped with the addition of 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid. The mass spectroscopy (MS) analysis was performed immediately to ensure high-quality tryptic peptides with minimal nonspecific cleavage or frozen at −80°C until samples were analyzed.

MS.

Capillary-liquid chromatography (LC)-nanospray tandem MS (Nano-LC/MS/MS) was performed on a Thermo Finnigan LTQ mass spectrometer equipped with a nanospray source operated in positive ion mode. The LC system was an UltiMate 3000 system from Dionex (Sunnyvale, CA). Solvent A was water containing 50 mM acetic acid, and solvent B was acetonitrile. Five microliters of each sample were first injected onto the μ-Precolumn Cartridge (Dionex) and then washed with 50 mM acetic acid. The injector port was switched to inject, and the peptides were eluted off of the trap onto the column. A 5-cm × 75-μm inner diameter ProteoPep II C18 column (New Objective, Woburn, MA) packed directly in the nanospray tip was used for chromatographic separations. Peptides were eluted directly off the column into the LTQ system using a gradient of 2–80% solvent B over 45 min, with a flow rate of 300 nl/min. The total run time was 65 min. The MS/MS was acquired according to standard conditions established in the laboratory. Briefly, a nanospray source operated with a spray voltage of 3 kV and a capillary temperature of 200°C was used. The scan sequence of the mass spectrometer was based on the TopTen method; the analysis was programmed for a full scan recorded between 350 and 2,000 Da and a MS/MS scan to generate product ion spectra to determine the amino acid sequence in consecutive instrument scans of the 10 most abundant peaks in the spectrum. The CID fragmentation energy was set to 35%. Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat count of 2 within 10 s, a mass list size of 200, an exclusion duration of 350 s, a low mass width of 0.5, and a high mass width of 1.5. The RAW data files collected on the mass spectrometer were converted to mzXML and MGF files using of MassMatrix data conversion tools (version 1.3, http://www.massmatrix.net/download). For low mass accuracy data, tandem MS spectra that were not derived from singly charged precursor ions were considered as both doubly and triply charged precursors. The resulting MGF files were searched using Mascot Daemon by Matrix Science (version 2.2.2, Boston, MA), and the database was searched against the mouse SwissProt database (version 2102_10, 16,326 sequences). The mass accuracy of the precursor ions was set to 2.0 Da given that the data were acquired on an ion trap mass analyzer and the fragment mass accuracy was set to 0.8 Da.

Dihydroethidium fluorescence.

Superoxide anion generation from I/R myocardium was determined using dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescence (27). Ex vivo hearts were rapidly embedded in OCT and solidified in liquid nitrogen. Hearts were then sectioned at 5 μm and placed on slides. Sections were covered with 10 μM DHE (Sigma) in PBS (pH 7.4) and incubated in the dark for 30 min at 37°C. After being rinsed with PBS (pH 7.4), sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for 10 min, and fluorescence was visualized at 570 nm.

MDA quantitation.

Hearts were homogenized in 20 mM PBS (pH 7.4) with 0.5 M butylated hydrotoluene (Sigma) at 4°C for 10 s for three cycles. Samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 13,000 rpm, and supernatants were stored at −80°C until the time of the MDA assay. Assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (MDA kit, OXIS International, Foster City, CA). MDA concentrations (in μM) were derived from the linear regression of known MDA standard concentrations and expressed per milligram of protein.

Statistical analysis.

The results of the experiments were analyzed by several statistical methods (e.g., paired or unpaired t-tests, ANOVA, χ2-analysis, curve fitting functions, etc.) using standard software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, version 4.0). Results are expressed as means ± SE. For comparisons between two groups, significance was determined by paired or unpaired Student t-tests. For comparison of multiple groups, multifactorial ANOVA with a post hoc comparison of the means with the Bonferroni correction was used to determine statistical significance. For all statistical evaluation, P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

SOD1-, SOD3-, and GSHPx-1-overexpressing mice.

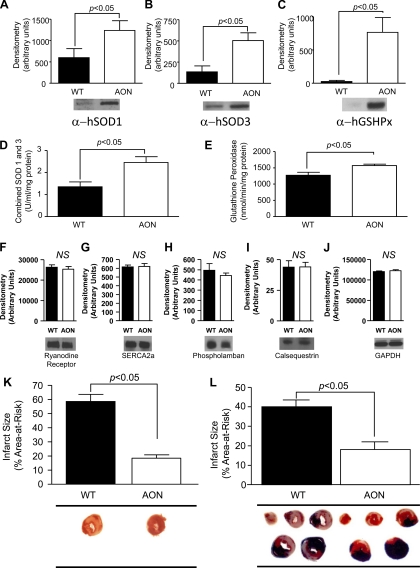

The generation and characterization of SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 (AON overexpressing) mice have been previously reported (31, 36). To examine the level of expression of these antioxidant enzymes, whole heart homogenates were analyzed by immunoblot analysis, which confirmed the expression of human SOD1 (Fig. 1A), human SOD3 (Fig. 1B), and human GSHPx-1 (Fig. 1C) in AON-overexpressing hearts. The relative level of expression appears quite exaggerated because of the minimal cross-reactivity of the anti-human enzyme antibodies with the native murine enzyme. However, comparable to what has been previously reported in pancreatic islet cells (36), the total activity of GSHPx-1 and SOD1/SOD3 was modestly but significantly increased (SOD1/SOD3: 1.8-fold and GSHPx-1: 1.2-fold; Fig. 1, D and E, respectively). To examine the effect of SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 overexpression on Ca2+-handling proteins, the levels of ryanodine receptor (Fig. 1F), SERCA2a (Fig. 1G), phospholamban (Fig. 1H), calsequestrin (Fig. 1I), and GAPDH (Fig. 1J) were also examined by immunoblot analysis. No differences in the level of any of these proteins were observed in AON-overexpressing hearts compared with WT hearts.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of antioxident network-overexpressing (AON) hearts and responses to ex vivo and in vivo myocardial injury. Baseline myocardial samples were examined for the protein levels of human (h)SOD1 (A), hSOD3 (B), glutathione peroxidase-1 (hGSHPx-1; C), ryanodine receptor (F), sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a; G), phospholamban (H), calsequestrin (I), and GAPDH (J), or the enzyme activity of combined SOD1/ hSOD3 (D) or GSHPx-1 (E) as described in materials and methods. Relative densitometry and representative images are shown for each. Enzyme activity is expressed per milligram of protein. K: hearts from either wild-type (WT) or AON animals were subjected to 30 min of global ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion as described in materials and methods. Infarct size is expressed as a percentage of the total left ventricle. Representative stained myocardial images are displayed. L: WT or AON animals were subjected to 60 min of in vivo left coronary artery ligation-induced ischemia and 24 h of reperfusion as described in materials and methods. Total infarct size is expressed as a percentage of the area at risk for infarction. Representative stained myocardial images are displayed. Values are means ± SE. NS, not statistically different.

AON expression protects against myocardial I/R injury.

Using an ex vivo myocardial I/R injury model, compared with hearts from WT animals, AON-overexpressing hearts demonstrated a 68% reduction (WT: 63.4 ± 4.8% vs. AON: 20.3 ± 3.7%, P < 0.05; Table 1) in myocardial IS after 30 min of global ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion (Fig. 1K).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for WT and AON mice subjected to ex vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury

| Genotype | Number of Mice/Group | Sex, % male/female | Age, days | Body Weight, g | Heart Weight, mg | Heart Weight/Body Weight, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 6 | 83/17 | 194.67 ± 26.42 | 28.67 ± 0.42 | 71.12 ± 4.47 | 2.48 ± 0.18 |

| AON | 4 | 75/25 | 186.25 ± 30.44 | 29.5 ± 0.50 | 73.93 ± 9.28 | 2.51 ± 0.32 |

Values are means ± SE. WT, wild-type control animals; AON, antioxidant network-expressing animals.

Given the possibility for increased sensitivity of the Langendorff perfusion model to oxidative stress, an in vivo model of regional left coronary artery I/R injury was examined. WT or AON-overexpressing mice were subjected to in vivo myocardial I/R injury of either 20 or 60 min followed by 24 h of reperfusion. Compared with WT mice, AON-overexpressing mice, concomitantly overexpressing human SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1, demonstrated a 92% reduction of IS after 20 min of ischemia (WT: 17.1 ± 1.8% vs. AON: 1.4 ± 0.6%, P < 0.05; data not shown) and a 55% reduction in IS after 60 min of ischemia and 24 h of reperfusion (WT: 40.0 ± 3.5% vs. AON: 18.1 ± 3.9%, P < 0.05; Fig. 1L and Table 2), indicating significant in vivo cardioprotective efficacy against prolonged ischemia with AON expression.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics for WT and AON mice subjected to in vivo myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury

| Genotype | Number of Mice/Group | Sex, % male/female | Age, days | Body Weight, g | Heart Weight, mg | Heart Weight/Body Weight, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 8 | 62.5/37.5 | 120 ± 6.78 | 26 ± 1.29 | 67.76 ± 5.20 | 2.60 ± 0.18 |

| AON | 12 | 68/32 | 130 ± 1.29 | 26 ± 1.26 | 78.44 ± 5.23 | 2.98 ± 0.15 |

Values are means ± SE.

AON expression attenuates the formation of ROS and lipid peroxidation after myocardial I/R injury.

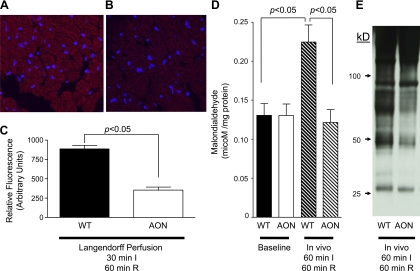

To elucidate the mechanism of the cardioprotection conferred by AON expression, ROS generation, measured by DHE staining, was examined in WT and AON-overexpressing hearts subjected to 30 min of ex vivo global ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion. AON-overexpressing hearts displayed significantly less DHE staining after I/R injury than WT hearts (relative fluorescence: 887.4 ± 45.47 in WT hearts vs. 353.3 ± 39.18 in AON-overexpressing hearts, P < 0.0001, n = 4 hearts/group; Fig. 2, A–C).

Fig. 2.

Effect of the AON on ROS formation, lipid peroxidation and reactive nitrogen species-mediated protein modification. A–C: WT (A) or AON (B) hearts were subjected to 30 min of global ex vivo ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion as described in materials and methods. Representative images of dihydroethidium (DHE) staining for ROS in WT (A) or AON (B) hearts are shown. C: quantitation of DHE staining after ischemia-reperfusion (I/R; n = 4 hearts/group). D: malondialdehyde (MDA) at baseline and after in vivo I/R injury in WT and AON hearts. WT or AON mice were subjected to 60 min of left coronary artery ligation-induced ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion as described in materials and methods. Total MDA is expressed per milligram of protein (n = 3 hearts/group). E: nitrotyrosine modification of myocardial proteins after in vivo myocardial I/R injury. WT or AON animals were subjected to 60 min of left coronary artery ligation-induced ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion, and immunoblot analysis of myocardial lysates for 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) modifications was conducted as described in materials and methods. Values are means ± SE.

To further assess ramifications of diminished ROS generation in AON-overexpressing hearts, the formation of MDA, an indicator of ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation, was measured in WT and AON-overexpressing hearts exposed to 60 min of in vivo ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion. For both the ex vivo and in vivo experiments, this 60-min reperfusion time was chosen so that we could observe the modifications that occur within the initial oxidative burst and the sustained oxidative production during the recovery phase of reperfusion. WT and AON-overexpressing hearts displayed comparable levels of MDA at baseline (WT: 0.131 ± 0.015 μM/mg protein vs. AON: 0.130 ± 0.015 μM/mg protein, P > 0.05, n = 3 hearts/group; Fig. 2D). In contrast, after I/R injury, WT hearts demonstrated a twofold increase in the formation of MDA, whereas AON-overexpressing hearts displayed no significant difference in MDA formation from baseline (postischemia: 0.225 ± 0.022 μM/mg protein in WT hearts vs. 0.1215 ± 0.017 μM/mg protein in AON-overexpressing hearts, P < 0.001, n = 3 hearts/group; Fig. 2D). Together, these data indicate that AON expression significantly scavenges ROS produced during myocardial I/R injury, reducing its detrimental effects.

AON expression reduces OPTM.

To further examine the ramifications of the observed reduction of ROS in AON-overexpressing mice after myocardial I/R injury, the “nitroproteome” of WT and AON-overexpressing hearts was examined for the specific peroxynitrite-mediated OPTM of tyrosine to 3-NT. Again, mice were subjected to 60 min of in vivo ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion so that we could observe the modifications that occurred within the initial oxidative burst and the sustained oxidative production during the myocardial recovery phase of reperfusion. WT hearts displayed a marked increase in OPTM formation after I/R compared with AON-expressing animals exposed to a similar experimental protocol (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, differences in the protein banding pattern suggested that concomitant SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 expression inhibits OPTM of multiple specific proteins.

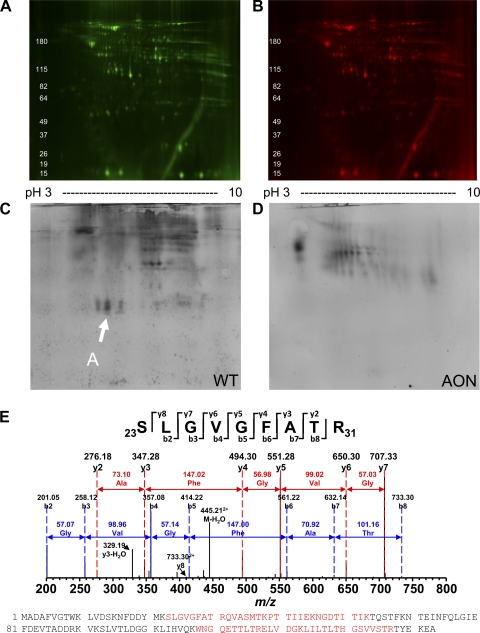

To assess the specific nitrotyrosine OPTM of myocardial proteins, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis followed by 3-NT immunoblot analysis was conducted. While there were no significant differences in the intensity and distribution between WT and AON-overexpressing heart lysates at baseline (Fig. 3, A and B), the number and intensity of 3-NT modified proteins were greater in WT hearts compared with AON-overexpressing hearts after myocardial I/R injury (Fig. 3, C and D), suggesting that AON expression protects specific proteins from detrimental tyrosine nitration. To determine the proteins modified, MS/MS analysis was conducted. This analysis revealed the novel finding that 3-NT modified protein A in WT hearts is cardiac fatty acid-binding protein (FABP)-3, a key metabolic protein (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

3-NT modifications of myocardial proteins after in vivo myocardial I/R injury. WT or AON animals were subjected to 60 min of left coronary artery ligation-induced ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion as described in materials and methods. Myocardial lysates were processed and subjected to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, and samples were examined for total protein (A and B) and 3-NT modifications via immunoblot analysis (C and D). E: arrows indicate initial protein identified by liquid chromotography tandem mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS) analysis. The designated protein shown in C was isolated as described in materials and methods. LC-MS/MS analysis revealed the identity of protein A to be fatty acid-binding protein (FABP)-3; peptide fragment spectra are shown with matched peptides shown in red in the FABP-3 protein sequence.

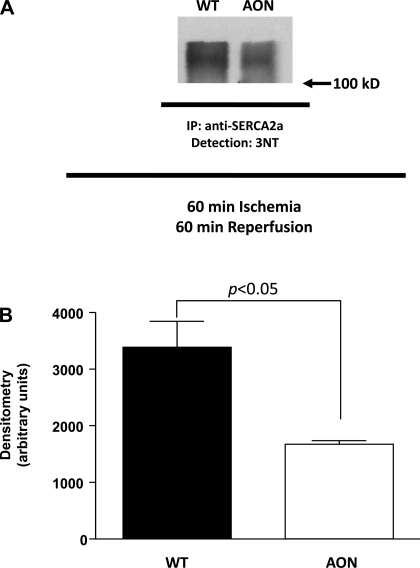

AON expression reduces the formation of peroxynitrite-mediated protein modification of SERCA2a.

Given our interest in the role of oxidative stress in regulating Ca2+ handling and recent reports (2, 29, 33, 50) of OPTM of SERCA2a in models of heart disease, the effect of AON expression on tyrosine nitration of SERCA2a after myocardial I/R injury was evaluated. Immunoprecipitation with antibody to SERCA2a and detection with antibody to 3-NT (Fig. 4A) revealed OPTM of SERCA2a in WT hearts subjected to 60 min of ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion but significantly less modification of SERCA2a from AON-overexpressing hearts (relative densitometry: 3,386 ± 454.7 in WT hearts vs. 1,672 ± 63.8 in AON-overexpressing hearts, P = 0.0324, n = 3 hearts/group; Fig. 4B). Again, at baseline, there was no difference in the total level of SERCA2a between WT and AON-overexpressing hearts (Fig. 1G). These data suggest that AON expression protects SERCA2a from the detrimental OPTM of tyrosine nitration.

Fig. 4.

3-NT modification of SERCA2a after in vivo myocardial I/R injury. WT or AON animals were subjected to 60 min of left coronary artery ligation-induced ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion as described in materials and methods. A: myocardial lysates were processed and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-SERCA2a polyclonal antibody. After electrophoresis and transfer of the samples, detection was achieved with anti-3-NT antibody. B: quantitation of the blot revealed significant differences in the level of 3-NT modified SERCA2a in WT versus AON hearts.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that transgenic concomitant overexpression of human SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 results in a marked reduction of ischemic injury, reducing ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation and RNS-mediated OPTM of a number of proteins, including cardiac FABP-3 and SERCA2a. The novelty of the present approach is that it uses the concomitant overexpression of several antioxidant enzymes en bloc to provide a network that can efficiently scavenge and neutralize ROS, thereby attenuating myocardial I/R injury. While only associative in nature, these novel data identifying OPTM of cardiac FABP and SERCA2a provide direction for future evaluation of the contribution of these specific protein modifications to myocardial I/R injury and may provide insights for the development of combined therapeutic approaches for the detection or treatment of acute ischemic heart disease, a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide (55).

It is widely accepted that myocardial I/R injury induces the production of ROS (17, 61, 62). With coronary artery occlusion, myocardial ischemia quickly leads to decreased intracellular ATP levels and the accumulation of intracellular Ca2+ and hydrogen, resulting in bioenergetic and functional abnormalities (28). During ischemia, the redox status of the myocardium shifts to a more reduced state (60). With reperfusion, reoxygenation of the myocardium results in exaggerated metabolic shifts and worsening myocardial damage (8). Generation of ROS at the onset of reperfusion shifts the redox status of the myocardium to a more oxidized state (60). There is a significant burst of oxygen-derived free radicals generated within the first minutes of reperfusion (62), peaking 4–7 min after the onset of reperfusion, followed by a persistent generation of oxygen-derived free radicals (22, 26).

Generation of both ROS and RNS induces mitochondrial injury, sarcoplasmic reticulum dysfunction, and further Ca2+ accumulation (52). Indeed, several studies (4, 7, 22) support the concept that ROS, such as superoxide anions, H2O2, and hydroxyl radicals, contribute to myocardial tissue injury secondary to ischemia and reperfusion (4, 7, 22). Myocardial cells are protected from minor oxidant challenges by an AON that includes enzymes such as SOD, catalase, and GSHPx (12, 20, 34, 49). A number of studies have used genetic modification of mice (knockout or transgenic overexpression of individual antioxidant enzymes) to explore the role of specific antioxidant enzymes in I/R injury. These results have yielded mixed interpretations regarding the role of individual antioxidant enzymes in myocardial I/R injury.

Experiments using knockout animals have demonstrated that after global ex vivo ischemia and reperfusion, hearts genetically devoid of GSH-Px displayed a reduced recovery of developed force, an increase in creatine kinase release, and larger myocardial IS compared with control hearts (57). Similarly, in SOD1 knockout hearts subjected to global ex vivo ischemia and reperfusion, a decreased recovery of LV developed pressure and larger myocardial higher IS were observed compared with control hearts (56). Complementing these reports, compared with control hearts, transgenic hearts overexpressing GSH-Px-1 displayed improved recovery of contractile force, reduced creatine kinase release, and reduced IS after ex vivo global ischemia and reperfusion (58). In a separate model, SOD1 overexpression resulted in an increase in the recovery of contractile function, a decrease in IS, and improved recovery of high-energy phosphates after global ex vivo ischemia (51). Similarly, in an ex vivo working heart model of ischemia, SOD3 overexpression resulted in improved contractile recovery, stroke work, and stroke volume compared with control hearts (10). Thus, in ex vivo models, significant myocardial protection has been reported with genetic modulation of the expression of individual antioxidant enzymes.

In contrast, in vivo experiments demonstrated that neither deficiency nor overexpression of SOD1 affected myocardial IS after left coronary artery ischemia and reperfusion (23). Furthermore, overexpression of GSHPx did not convey in vivo myocardial protection in the same model (23). The conclusion from this study was that neither SOD1 nor GSHPx-1 modulates the susceptibility to in vivo myocardial I/R injury (23). However, given the fact that each of these enzymes acts as a critical component within an AON, one possibility for the disparate ex vivo and in vivo results is that neither enzyme alone is capable of full cardioprotective efficacy in vivo. This concept is supported by a prior study (36) using AON-expressing mice that demonstrated that AON pancreatic islets were maximally resistant to injury induced by hypoxanthine-xanthine oxidase-generated production of superoxide radicals ex vivo compared with WT, single-, or double-transgenic islets. Similarly, concomitant expression of SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 significantly protected pancreatic islets from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury ex vivo after an incubation under hypoxic conditions in nutrient-poor medium for 18 h followed by an incubation under normoxic conditions for 48 h in complete medium compared with WT islets. Additionally, single- or double-transgenic islets demonstrated no protection in this model. Alternatively, modulation of individual antioxidant enzyme levels may result in detrimental changes to the overall antioxidant system (13, 38, 39). Indeed, in models of induced oxidative stress, proteomic analysis revealed concomitant increases in SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 levels, likely representing an adaptive upregulation of the AON to combat oxidative stress (41). The current model attempted to mimic such a response by expression of an AON rather than individual antioxidant enzymes. While the immunoblots using anti-human antibodies exaggerate the level of expression of human SOD1, human SOD3, and human GSHPx-1 because of limited cross-reactivity to the murine enzymes, measurement of the level of enzymatic activity demonstrated a modest increase in GSHPx-1 and combined SOD1 and SOD3 activity, comparable to what has previously been reported (36).

Additional differences between the ex vivo and in vivo models are due to the fact that inflammatory cells, which are absent in ex vivo perfusion models, contribute to a prolonged generation of oxygen-derived free radicals during reperfusion in vivo (14). Also critical to the differences observed between ex vivo and in vivo studies is the fact that ex vivo perfusion with crystalloid solutions, which lack iron-binding proteins, may facilitate the production of hydroxyl radical by Fenton/Haber-Weiss reactions. Therefore, any approach that reduces oxidative stress may have a more profound effect in ex vivo perfused hearts but not on in vivo myocardial I/R injury. Here, we demonstrate that AON expression not only attenuates ex vivo I/R injury but also significantly reduces in vivo myocardial I/R injury, reducing infarct size and ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation.

ROS damage cells via a variety of mechanisms including peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids within the membrane lipids (9). While studies (3, 11, 44) have suggested that ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation can occur with ischemia, upon restoration of blood flow, increased levels of ROS and RNS are generated, which contribute to lipid peroxidation. Peroxidation of membrane lipids results in the fragmentation of polyunsaturated fatty acids producing various aldehydes, alkenals, and hydroxyalkenals, including MDA and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, that are reactive with proteins (15). Thus, by quenching ROS and limiting lipid peroxidation, AON expression conveys cardioprotection from OPTM of proteins after myocardial I/R injury.

With reperfusion of the myocardium, increased NO and superoxide results in the formation of ONOO− and suppression of myocardial tissue O2 consumption, causing a hyperoxygenation state that potentiates ROS generation (59). The nitration of tyrosine to 3-NT represents an OPTM secondary to oxidative stress that has been reported in a number of pathological conditions, including aging, hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis (5, 18, 21). In animal models of sepsis, diabetes, or myocardial I/R injury, ONOO−-mediated tyrosine nitration appears restricted, as several studies (24, 25, 32, 46, 47, 53, 54) have demonstrated relatively small numbers of proteins that are modified.

Prior work has linked ROS production to oxidative modification of Ca2+-handling proteins such as SERCA2a (30, 43, 45); however, the identification of 3-NT modification of SERCA2a in response to I/R injury represents a novel finding. SERCA2a has been shown to be nitrated at two adjacent tyrosine residues (Tyr294 and Tyr295) in both skeletal and cardiac muscle from aged animals (29, 50). Tyrosine nitration of SERCA2a results in a decrease in activity (2, 33). Indeed, in myocardial samples from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, nitrotyrosine modification of SERCA2a positively correlated with the time to half-relaxation in myocytes isolated from control and dilated cardiomyopathic hearts (33). These data demonstrate that SERCA activity is sensitive to the oxidative state of the myocardium. In the present study, SERCA2a appears to be a key protein susceptible to detrimental OPTM after myocardial I/R injury. AON overexpression not only results in a decrease in OPTM by tyrosine nitration of a number of myocardial proteins but also specifically attenuates tyrosine nitration of the key Ca2+-handling protein SERCA2a.

Characterization of additional proteins that underwent tyrosine nitration using two-dimensional immunoblot analysis coupled with LC-MS/MS identified heart-type FABP (hFABP or FABP-3) as one of the major proteins that underwent 3-NT modification after myocardial I/R injury in WT hearts but not in AON-overexpressing hearts. FABP-3 is expressed at high levels in the myocardium, where it serves to translocate fatty acids and fatty acid derivatives in the cytoplasm (16). In response to insulin stimulation, increased FABP phosphorylation has been observed in cardiac myocytes, suggesting metabolic regulation of FABP activity (37). In mice deficient in FABP-3, inefficient uptake of plasma long-chain fatty acids results in a switch to glucose utilization as an energy source (6). Thus, the activity of FABP appears critical in regulating energetic homeostasis. Of further interest, with myocardial injury, FABP-3 is released into the circulation and has been used as a biomarker for the diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes (1, 48). Whether detection of 3-NT modified FABP may increase the sensitivity and specificity for the detection of acute coronary syndromes is the focus of ongoing work. While speculative, specific ROS- or RNS-mediated modifications of specific myocardial proteins may serve to provide increased sensitivity and specificity for the detection of myocardial injury.

There are several limitations to the study that require acknowledgement. The present study did not differentiate between or specifically determine whether the early burst of oxidant generation during the first minutes of reperfusion or the sustained elevated levels during reperfusion were attenuated by AON expression. In addition, the present study did not identify the specific species or the source of oxidants that were potentially attenuated by AON expression. Furthermore, the examination of individual or dual antioxidant enzyme expression was not evaluated; therefore, the contribution of single- or double-transgene expression in this specific model cannot be stated. However, the prior work cited demonstrates that concomitant expression of SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 was required for maximal protection of pancreatic islets from superoxide-mediated injury and hypoxia/reoxygenation-mediated injury ex vivo. Indeed, future studies examining the efficacy of single, dual, or triple antioxidant enzyme expression in this model and models of increased oxidative stress (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or hypercholesterolemia) will be critical to determining the applicability of the expression of an AON in conveying cardiovascular protection in vivo. Finally, these novel data identifying OPTM of cardiac FABP-3 and SERCA2a are associative in nature and do not prove that the reduction of these specific modification in AON-overexpressing hearts prevents I/R injury. Ongoing studies aimed at examining the contribution of the modification of these proteins to myocardial injury are underway.

In conclusion, a number of variables and pathways influence the susceptibility of the myocardium to ischemic damage. A key group of enzymes combine to form a network focused on the detoxification of ROS and RNS produced during I/R injury. The present study demonstrates that concomitant overexpression of SOD1, SOD3, and GSHPx-1 protects the murine myocardium from I/R-mediated oxidative injury, reducing lipid peroxidation and OPTM of tyrosine nitration of a number of myocardial proteins, including FABP and the critical Ca2+-handling protein SERCA2a.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant K08-HL-094703 and 10UFEL4180090 (to R. J. Gumina), an American Heart Association-Great Rivers Affiliate Student Undergraduate Research Fellowship (to Z. M. Huttinger and L. A. Goodman), an AΩA Carolyn L. Kuckein Student Research Fellowship (to R. Mital), and the Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute and Ross Academic Advisory Committee (to R. J. Gumina).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Liwen Zhang and Dr. Cindy James of The Ohio State University Shared Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility.

Present address of W. Zhang: Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan 410011, China.

Present address of M. Cai: Department of Endocrinology and Breast Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China

REFERENCES

- 1. Aartsen WM, Pelsers MMAL, Hermens WT, Glatz JFC, Daemen MJAP, Smits JFM. Heart fatty acid binding protein and cardiac troponin T plasma concentrations as markers for myocardial infarction after coronary artery ligation in mice. Pflügers Arch 439: 416–422, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adachi T, Matsui R, Xu S, Kirber M, Lazar HL, Sharov VS, Schoneich C, Cohen RA. Antioxidant improves smooth muscle sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase function and lowers tyrosine nitration in hypercholesterolemia and improves nitric oxide-induced relaxation. Circ Res 90: 1114–1121, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ambrosio G, Flaherty JT, Duilio C, Tritto I, Santoro G, Elia PP, Condorelli M, Chiariello M. Oxygen radicals generated at reflow induce peroxidation of membrane lipids in reperfused hearts. J Clin Invest 87: 2056–2066, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ambrosio G, Zweier JL, Flaherty JT. The relationship between oxygen radical generation and impairment of myocardial energy metabolism following post-ischemic reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol 23: 1359–1374, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beal MF. Oxidatively modified proteins in aging and disease. Free Radic Biol Med 32: 797–803, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Binas B, Danneberg H, McWhir J, Mullins L, Clark AJ. Requirement for the heart-type fatty acid binding protein in cardiac fatty acid utilization. FASEB J 13: 805–812, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bolli R. Oxygen-derived free radicals and myocardial reperfusion injury: an overview. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 5, Suppl 2: 249–268, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braunwald E, Kloner RA. Myocardial reperfusion: a double-edged sword? J Clin Invest 76: 1713–1719, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ceconi C, Cargnoni A, Pasini E, Condorelli E, Curello S, Ferrari R. Evaluation of phospholipid peroxidation as malondialdehyde during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 260: H1057–H1061, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen EP, Bittner HB, Davis RD, Folz RJ, Van Trigt P. Extracellular superoxide dismutase transgene overexpression preserves postischemic myocardial function in isolated murine hearts. Circulation 94: II412–II417, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cordis GA, Maulik N, Das DK. Detection of oxidative stress in heart by estimating the dinitrophenylhydrazine derivative of malonaldehyde. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2: 1645–1653, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dhalla NS, Elmoselhi AB, Hata T, Makino N. Status of myocardial antioxidants in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 47: 446–456, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ditelberg JS, Sheldon RA, Epstein CJ, Ferriero DM. Brain injury after perinatal hypoxia-ischemia is exacerbated in copper/zinc superoxide dismutase transgenic mice. Pediatr Res 39: 204–208, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duilio C, Ambrosio G, Kuppusamy P, DiPaula A, Becker LC, Zweier JL. Neutrophils are primary source of O2 radicals during reperfusion after prolonged myocardial ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2649–H2657, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med 11: 81–128, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fournier NC, Zuker M, Williams RE, Smith IC. Self-association of the cardiac fatty acid binding protein. Influence on membrane-bound, fatty acid dependent enzymes. Biochemistry 22: 1863–1872, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garlick PB, Davies MJ, Hearse DJ, Slater TF. Direct detection of free radicals in the reperfused rat heart using electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Circ Res 61: 757–760, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gow AJ, Farkouh CR, Munson DA, Posencheg MA, Ischiropoulos H. Biological significance of nitric oxide-mediated protein modifications. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L262–L268, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gumina RJ, O'Cochlain DF, Kurtz CE, Bast P, Pucar D, Mishra P, Miki T, Seino S, Macura S, Terzic A. KATP channel knockout worsens myocardial calcium stress load in vivo and impairs recovery in stunned heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1706–H1713, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Gargano M, Cao J. The nature of antioxidant defense mechanisms: a lesson from transgenic studies. Environ Health Perspect 106: 1219–1228, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ischiropoulos H. Biological selectivity and functional aspects of protein tyrosine nitration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 305: 776–783, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jeroudi MO, Hartley CJ, Bolli R. Myocardial reperfusion injury: role of oxygen radicals and potential therapy with antioxidants. Am J Cardiol 73: 2B–7B, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jones SP, Hoffmeyer MR, Sharp BR, Ho YS, Lefer DJ. Role of intracellular antioxidant enzymes after in vivo myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H277–H282, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanski J, Behring A, Pelling J, Schoneich C. Proteomic identification of 3-nitrotyrosine-containing rat cardiac proteins: effects of biological aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H371–H381, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kanski J, Schoneich C. Protein nitration in biological aging: proteomic and tandem mass spectrometric characterization of nitrated sites. Methods Enzymol 396: 160–171, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kevin LG, Camara AK, Riess ML, Novalija E, Stowe DF. Ischemic preconditioning alters real-time measure of O2 radicals in intact hearts with ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H566–H574, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kin H, Zhao ZQ, Sun HY, Wang NP, Corvera JS, Halkos ME, Kerendi F, Guyton RA, Vinten-Johansen J. Postconditioning attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting events in the early minutes of reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res 62: 74–85, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kloner RA, DeBoer LW, Darsee JR, Ingwall JS, Hale S, Tumas J, Braunwald E. Prolonged abnormalities of myocardium salvaged by reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 241: H591–H599, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Knyushko TV, Sharov VS, Williams TD, Schoneich C, Bigelow DJ. 3-Nitrotyrosine modification of SERCA2a in the aging heart: a distinct signature of the cellular redox environment. Biochemistry 44: 13071–13081, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kourie JI. Interaction of reactive oxygen species with ion transport mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 275: C1–C24, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lepore DA, Shinkel TA, Fisicaro N, Mysore TB, Johnson LE, d'Apice AJ, Cowan PJ. Enhanced expression of glutathione peroxidase protects islet beta cells from hypoxia-reoxygenation. Xenotransplantation 11: 53–59, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu B, Tewari AK, Zhang L, Green-Church KB, Zweier JL, Chen YR, He G. Proteomic analysis of protein tyrosine nitration after ischemia reperfusion injury: Mitochondria as the major target. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794: 476–485, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lokuta AJ, Maertz NA, Meethal SV, Potter KT, Kamp TJ, Valdivia HH, Haworth RA. Increased nitration of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in human heart failure. Circulation 111: 988–995, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marczin N, El-Habashi N, Hoare GS, Bundy RE, Yacoub M. Antioxidants in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: therapeutic potential and basic mechanisms. Arch Biochem Biophys 420: 222–236, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matsushima S, Kinugawa S, Ide T, Matsusaka H, Inoue N, Ohta Y, Yokota T, Sunagawa K, Tsutsui H. Overexpression of glutathione peroxidase attenuates myocardial remodeling and preserves diastolic function in diabetic heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2237–H2245, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mysore TB, Shinkel TA, Collins J, Salvaris EJ, Fisicaro N, Murray-Segal LJ, Johnson LE, Lepore DA, Walters SN, Stokes R, Chandra AP, O'Connell PJ, d'Apice AJ, Cowan PJ. Overexpression of glutathione peroxidase with two isoforms of superoxide dismutase protects mouse islets from oxidative injury and improves islet graft function. Diabetes 54: 2109–2116, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nielsen SU, Spener F. Fatty acid-binding protein from rat heart is phosphorylated on Tyr19 in response to insulin stimulation. J Lipid Res 34: 1355–1366, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Omar BA, Gad NM, Jordan MC, Striplin SP, Russell WJ, Downey JM, McCord JM. Cardioprotection by Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase is lost at high doses in the reoxygenated heart. Free Radic Biol Med 9: 465–471, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Omar BA, McCord JM. The cardioprotective effect of Mn-superoxide dismutase is lost at high doses in the postischemic isolated rabbit heart. Free Radic Biol Med 9: 473–478, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Paglia DE, Valentine WN. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase.. J Lab Clin Med 70: 158–169, 1967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sainz J, Wangensteen R, Rodriguez Gomez I, Moreno JM, Chamorro V, Osuna A, Bueno P, Vargas F. Antioxidant enzymes and effects of tempol on the development of hypertension induced by nitric oxide inhibition. Am J Hypertens 18: 871–877, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shiomi T, Tsutsui H, Matsusaka H, Murakami K, Hayashidani S, Ikeuchi M, Wen J, Kubota T, Utsumi H, Takeshita A. Overexpression of glutathione peroxidase prevents left ventricular remodeling and failure after myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation 109: 544–549, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Singh RB, Chohan PK, Dhalla NS, Netticadan T. The sarcoplasmic reticulum proteins are targets for calpain action in the ischemic-reperfused heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37: 101–110, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tavazzi B, Lazzarino G, Di Pierro D, Giardina B. Malondialdehyde production and ascorbate decrease are associated to the reperfusion of the isolated postischemic rat heart. Free Radic Biol Med 13: 75–78, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Temsah RM, Netticadan T, Chapman D, Takeda S, Mochizuki S, Dhalla NS. Alterations in sarcoplasmic reticulum function and gene expression in ischemic-reperfused rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H584–H594, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Turko IV, Li L, Aulak KS, Stuehr DJ, Chang JY, Murad F. Protein tyrosine nitration in the mitochondria from diabetic mouse heart. Implications to dysfunctional mitochondria in diabetes. J Biol Chem 278: 33972–33977, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Turko IV, Murad F. Quantitative protein profiling in heart mitochondria from diabetic rats. J Biol Chem 278: 35844–35849, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Van Nieuwenhoven FA, Kleine AH, Wodzig WH, Hermens WT, Kragten HA, Maessen JG, Punt CD, Van Dieijen MP, Van der Vusse GJ, Glatz JF. Discrimination between myocardial and skeletal muscle injury by assessment of the plasma ratio of myoglobin over fatty acid-binding protein. Circulation 92: 2848–2854, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Venardos KM, Kaye DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, antioxidant enzyme systems, and selenium: a review. Curr Med Chem 14: 1539–1549, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Viner RI, Williams TD, Schoneich C. Peroxynitrite modification of protein thiols: oxidation, nitrosylation, and S-glutathiolation of functionally important cysteine residue(s) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase. Biochemistry 38: 12408–12415, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang P, Chen H, Qin H, Sankarapandi S, Becher MW, Wong PC, Zweier JL. Overexpression of human copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) prevents postischemic injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4556–4560, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wei GZ, Zhou JJ, Wang B, Wu F, Bi H, Wang YM, Yi DH, Yu SQ, Pei JM. Diastolic Ca2+ overload caused by Na+/Ca2+ exchanger during the first minutes of reperfusion results in continued myocardial stunning. Eur J Pharmacol 572: 1–11, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. White MY, Cordwell SJ, McCarron HC, Prasan AM, Craft G, Hambly BD, Jeremy RW. Proteomics of ischemia/reperfusion injury in rabbit myocardium reveals alterations to proteins of essential functional systems. Proteomics 5: 1395–1410, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. White MY, Tchen AS, McCarron HC, Hambly BD, Jeremy RW, Cordwell SJ. Proteomics of ischemia and reperfusion injuries in rabbit myocardium with and without intervention by an oxygen-free radical scavenger. Proteomics 6: 6221–6233, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott M, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Nichol G, O'Donnell C, Roger V, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong N, Wylie-Rosett J, Hong Y; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 119: 480–486, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yoshida T, Maulik N, Engelman RM, Ho YS, Das DK. Targeted disruption of the mouse Sod I gene makes the hearts vulnerable to ischemic reperfusion injury. Circ Res 86: 264–269, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yoshida T, Maulik N, Engelman RM, Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Rousou JA, Flack JE, 3rd, Deaton D, Das DK. Glutathione peroxidase knockout mice are susceptible to myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Circulation 96: II-216–II-220, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yoshida T, Watanabe M, Engelman DT, Engelman RM, Schley JA, Maulik N, Ho YS, Oberley TD, Das DK. Transgenic mice overexpressing glutathione peroxidase are resistant to myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 28: 1759–1767, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhao X, He G, Chen YR, Pandian RP, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide regulates postischemic myocardial oxygenation and oxygen consumption by modulation of mitochondrial electron transport. Circulation 111: 2966–2972, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhu X, Zuo L, Cardounel AJ, Zweier JL, He G. Characterization of in vivo tissue redox status, oxygenation, and formation of reactive oxygen species in postischemic myocardium. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 447–455, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zweier JL. Measurement of superoxide-derived free radicals in the reperfused heart. Evidence for a free radical mechanism of reperfusion injury. J Biol Chem 263: 1353–1357, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zweier JL, Flaherty JT, Weisfeldt ML. Direct measurement of free radical generation following reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 1404–1407, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]